Abstract

Methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2) plays fundamental roles in the nervous system, as both gain- and loss-of-function of MECP2 are associated with severe neurological conditions. Understanding the molecular function of MeCP2 will not only provide insights into the pathogenesis of MeCP2-related disorders, but will also shed light on the epigenetic regulation of neuronal function. In the past few years, a number of studies have provided mechanistic evidence that MeCP2 recruits co-repressor complexes to particular sequences of methylated DNA. Additionally, innovative design and high-throughput sequencing technologies have provided opportunities to study the effects of MeCP2 on the neuronal transcriptome at an unprecedented level of detail, demonstrating that MeCP2 modulates gene expression in a context-specific manner. These findings have raised new questions and challenged current models of MeCP2 function. In this review, we describe several recent developments, highlight future challenges, and articulate a model by which MeCP2 functions as an organizer of chromatin architecture to modulate global gene expression in the nervous system.

INTRODUCTION

DNA methylation at cytosine residues is a central epigenetic mark that plays crucial roles in multiple cellular processes, including cellular differentiation, X-chromosome inactivation, genomic imprinting, and regulation of gene expression [1–4]. Multiple proteins bind to methylated DNA with specificity and are thought to mediate a subset of the molecular functions of cytosine methylation [5]. One such “reader” of DNA methylation is methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), a protein that has received a significant amount of attention since its discovery in 1992 [6]. The importance of MeCP2 in the central nervous system (CNS) was appreciated after the discovery that loss-of-function mutations in MECP2 cause Rett syndrome (RTT), a progressive X-linked neurological disorder characterized by a unique natural history [7]. In RTT, seemingly normal development occurs for approximately the first year of life and is followed by developmental stagnation with subsequent regression, in which previously-learned motor and social skills are lost [8,9]. In addition to loss-of-function mutations, duplications of the MECP2 gene also impair CNS function and lead to MECP2 duplication syndrome (MDS) [10], a neurological disorder characterized by severe intellectual disability and motor impairment.

The drastic neurological consequences of gain- or loss-of-function of MECP2 underscore the need to understand the roles of MeCP2 in the CNS. MeCP2 was originally characterized as a nuclear protein that binds to methylated cytosine nucleotides followed by a guanine (mCG) [6], and has been thought to mediate repression of gene transcription [11–13]. However, loss of MeCP2 has been shown to alter the expression of many genes in different ways, with approximately equal numbers of up- and down-regulated genes [14–17]. Of note, the magnitudes of these MeCP2-associated gene expression changes are small, even in defined neuronal cell types [17]. This pattern is unlike what would be expected from a typical transcriptional activator or repressor. Interestingly, a large number of genes show reciprocal gene expression changes due to gain or loss of MeCP2 [14]. These findings have led to numerous proposed models by which MeCP2 functions to regulate gene expression [18], but there has not been a unifying mechanism that would explain and accommodate all current findings.

CONTEXT-SPECIFIC INSIGHTS INTO MECP2-DEPENDENT GENE EXPRESSION

Since MeCP2 is a chromatin-bound nuclear protein that binds methylated DNA with specificity, mis-regulation of gene expression has been thought to underlie the pathogenesis of both RTT and MDS [9,18]. As a result, much effort has gone into identifying MeCP2 target genes. When MeCP2 was first described, it was thought to be a global, genome-wide repressor of gene expression due to its ability to inhibit transcription of methylated DNA in vitro and in cellular reporter assays [11–13]. However, the initial search for in vivo gene expression changes due to loss of MeCP2 failed to find convincing evidence of global de-repression, as there were few statistically-significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between forebrain samples from wild-type (WT) and Mecp2-null mice [19]. Subsequently, specific genes, such as Bdnf (encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor), were identified as targets of MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression [20,21], supporting the idea that MeCP2 functions as a gene-specific, “non-global” repressor. In recent years, with the advent of next-generation sequencing technology to examine genome-wide transcriptional changes with high sensitivity, the field has since returned to the idea of MeCP2 acting globally, as hundreds of DEGs have been identified as a result of MeCP2 dysfunction in vivo. However, making sense of MeCP2-associated gene expression changes and determining bona fide MeCP2 targets has proven difficult, as hundreds of genes are subtly altered in MeCP2-mutant cells and the lists of DEGs vary significantly among different studies [14–17,22–24].

Cellular heterogeneity has been thought to contribute to the variety and subtle nature of MeCP2-dependent gene expression changes [16], as MeCP2 is expressed in nearly all cell types in an X-linked manner. Previous gene expression studies analyzing brain tissues comprising many different cell types are likely affected by cellular heterogeneity, potentially masking authentic MeCP2-dependent gene expression changes. Additionally, the nuclear localization of MeCP2 adds another layer of complexity to studying its effects on gene expression: most studies have assessed the effects of MeCP2 on mRNA instead of nuclear RNA, which differ due to post-transcriptional processing [25]. A recently developed technique overcame these challenges, employing biotin-tagging of endogenous MeCP2 within genetically-determined cell types in the mouse brain to examine the effects of MeCP2 dysfunction in a cell type-specific manner [17]. Similar sequencing methods were also used to examine nuclear and whole-cell RNA species from the same animal, enabling comparisons of gene expression changes within different cellular compartments.

By comparing gene expression profiles from the same neuronal cell type between wild-type and Mecp2-mutant mice, this study demonstrated that MeCP2 dysfunction results in gene expression changes that are largely cell type-specific and MeCP2 mutation-specific [17]. A number of other characteristics of MeCP2-sensitive genes also became evident: lowly-expressed, cell type-enriched genes were more sensitive to MeCP2 dysfunction, and a more severe RTT-causing MeCP2 mutation was associated with a greater number of DEGs and larger amplitudes of gene expression changes. Additionally, genes encoding synaptic proteins were found to be preferentially down-regulated in excitatory neurons, while genes encoding transcription factors were preferentially up-regulated in inhibitory neurons.

This study was also able to identify cellular compartment-specific changes in Mecp2mutant mouse models. Profiling both nuclear RNA (predominantly composed of pre-mRNA) and whole-cell RNA (predominantly mRNA) from the brains of the same animals revealed subcellular differences in the expression of many genes due to MeCP2 dysfunction: genes longer in length tended to be down-regulated when profiling nuclear RNA, but were preferentially up-regulated with whole-cell RNA profiling [17]. These findings are consistent with the presence of post-transcriptional compensation for MeCP2-dependent transcriptional changes, likely due to the effects of RNA-binding proteins and altered mRNA stability. The presence of such changes confounds the use of whole-cell RNA species as a primary means to identify bona fide MeCP2 transcriptional targets, supporting the use of nuclear RNA to examine the primary effects of MeCP2 on gene transcription.

In addition to identifying cell type- and cellular compartment-specific gene expression changes, this study systematically analyzed allele-specific gene expression in a female RTT mouse model for the first time. Although RTT is an X-linked dominant disorder that primarily occurs in heterozygous females, RTT research has primarily used hemizygous male mice because of limits imposed by mosaic expression of MeCP2 in females due to random X-chromosome inactivation [18]. Overcoming X-linked cellular heterogeneity and distinguishing cell-autonomous from non-cell-autonomous effects of MeCP2 dysfunction are thus important challenges for RTT research. Using Mecp2 allele-specific gene expression profiling in female Mecp2-mutant mice, this study uncovered many non-cell-autonomous gene expression changes in MeCP2 WT-expressing neurons as a result of MeCP2 dysfunction in neighboring neurons [17]. The number and amplitude of non-cell-autonomous DEGs correlated with the molecular severity of MeCP2 mutation. Importantly, however, the majority of gene expression changes associated with MeCP2 dysfunction in female mice were cell-autonomous (i.e. occurring in mutant neurons). These findings were corroborated by a recent study employing a novel singlenucleus sequencing method, taking advantage of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in genes expressed in cis with Mecp2 (or MECP2) to resolve X-linked cellular mosaicism. Using this technique, this study also identified non-cell-autonomous gene expression changes in mosaic female mice, as well as in human post-mortem RTT brain tissues [26]. Non-cell-autonomous effects due to loss of MeCP2 have been described previously and have been thought to be mediated by MeCP2-dependent changes in signaling molecules [27], but more work is necessary to evaluate the functional significance of non-cell-autonomous gene expression changes and their potential to contribute to RTT pathogenesis.

MECP2-MEDIATED REPRESSION OF HIGHLY METHYLATED LONG GENES

Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which MeCP2 modulates gene expression has been a challenging endeavor, but recent analyses of MECP2 mutations in RTT have provided key insights into the molecular function of MeCP2. Largely owing to the relentless support and advocacy from patient organizations, a database was established to collect genetic information from RTT patients (RettBASE, http://mecp2.chw.edu.au) [28]. Upon exploration of this database, Lyst and colleagues found that most disease-causing missense mutations cluster within two distinct regions of the MECP2 gene, encoding for the methyl-CpG-binding domain (MBD) and the NCoR/SMRT (nuclear receptor co-repressor/silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor) interacting domain (NID) [29]. The selective high density of missense mutations within these two domains highlights the importance of their respective functions: binding to methylated DNA and binding to co-repressor complexes. Multiple layers of experimental evidence have confirmed that missense mutations within the MBD impair the binding of MeCP2 to methylated DNA [30–34], while mutations in the NID abolish the interaction between MeCP2 and the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, both in vitro and in vivo [29]. In addition, RTT-associated mutations in the C-terminal domain of MeCP2 were found to either destabilize the MeCP2 protein or interfere with NID function, further highlighting the critical roles of the MBD and NID in MeCP2 function [35]. A cocrystal structure of the MeCP2 NID and TBLR1 (a component of the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex) was recently solved, providing further support for this direct interaction [36]. Together, these findings provide compelling biochemical evidence that MeCP2 functions as a “molecular bridge” between methylated DNA and the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, suggesting a role for MeCP2 in the mediation of transcriptional repression.

Consistent with a repressive function of MeCP2, two studies have reported that genes up-regulated in the absence of MeCP2 tend to be longer in length than the genome-wide average, identifying a positive correlation between gene length and the degree of up-regulation [22,37]. To explain these findings, Gabel and colleagues investigated the relationship between gene body DNA methylation and gene length, paying particular attention to non-CG methylation, as MeCP2 has recently been shown to bind to mCA in vivo in addition to mCG [22,23,38,39] (one report has refined this specificity even further to mCG and the mCAC trinucleotide [39]). They found that long genes (>100 kb) contained higher levels of gene body mCA on average, and that MeCP2 binding was enriched within these genes [22]. They concluded that MeCP2 acts to repress gene expression by binding to mCA within long genes. Of note, the positive correlation between gene length and up-regulation due to loss of MeCP2 became evident when using a running average plot analysis, which likely bears statistical limitations [40]. Thus, a scatter plot illustrating individual genes, in addition to a running average plot, was presented to demonstrate individual gene expression changes in MeCP2 mutant-expressing cells [17].

Despite strong evidence for the capacity of MeCP2 to act as a bridge between methylated DNA sequences and the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, patients with mutations in the NID typically present with a clinically milder form of RTT [41,42], suggesting that this interaction is unlikely the only function of MeCP2 that is impaired in typical RTT and that MeCP2 may operate in other ways to regulate neuronal function. Additionally, the long gene model of repression explains only a subset of the gene expression changes associated with MeCP2 dysfunction, as loss of MeCP2 leads to approximately equal numbers of up-regulated and down-regulated genes, both long and short, with similar magnitudes of fold changes [17]. The extent to which some DEGs are bona fide targets of MeCP2 and some are an indirect consequence of MeCP2 dysfunction has been difficult to distinguish, largely due to the difficulties in profiling MeCP2 binding sites across the genome. Thus far, two starkly contrasting binding profiles of MeCP2 within the neuronal genome have been published. One shows broad binding patterns throughout the genome, tracking mCG and mCA density, but with no distinct binding peaks [22,23,39,43]. The other demonstrates selective enrichment of MeCP2 binding within GC-rich chromatin regions [44]. Although in vitro biochemical evidence corroborates the notion that MeCP2 binds both mCG and mCA [22,38,39], the extent to which MeCP2 occupancy in vivo tracks each mCG and mCA site remains to be determined, as current ChIP-seq studies of MeCP2 lack base resolution. Alternative approaches are needed to rule out potential crosslinking artifacts associated with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and may help disseminate the exact binding profile of MeCP2 in vivo. Ultimately, combining lists of cell typespecific DEGs with cell type-specific binding information at base resolution will likely uncover bona fide MeCP2 transcriptional targets and illustrate the authentic molecular mechanism by which MeCP2 modulates gene expression.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There has been significant progress in our understanding of the interactions between MeCP2 and both methylated DNA and the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, and new technologies have provided a wealth of information about the effects of MeCP2 on gene expression. Together, these new findings have generated a number of important questions and opened up new areas of study. For example, the in vivo functional significance of NCoR/SMRT recruitment warrants further investigation: the loci to which MeCP2 recruits NCoR/SMRT in vivo are unknown, so whether MeCP2 recruits NCoR/SMRT to MeCP2-sensitive genes remains unclear. Additionally, more work is necessary to characterize the specific proteins recruited by the MeCP2-bound NCoR/SMRT complex. Current mechanisms rely on the canonical model of NCoR/SMRT recruitment, which directly leads to repression of target gene transcription via the histone deacetylase HDAC3 [18]. Given recent developments in our understanding of the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex [45–48], the functional outcome of the MeCP2-NCoR/SMRT interaction may be more complex than originally thought.

New developments have also permitted the ability to ultimately identify bona fide MeCP2 target genes. With sensitive gene expression profiling techniques that overcome cell type and X-linked cellular heterogeneity, it is possible to identify a core set of gene expression changes that may underlie RTT pathogenesis. Through identification of consistent DEGs in different cell types and across different periods of disease progression, it may be possible to identify genes and pathways that underlie the core features of RTT and shed insight into the direct and indirect effects of MeCP2 dysfunction on gene expression.

Numerous other aspects of MeCP2 function remain to be elucidated. For example, it remains unclear why many genes are either up- or down-regulated due to MeCP2 dysfunction, and why the amplitudes of these gene expression changes are subtle, even in defined cell types [17]. Additionally, the unique clinical progression due to MeCP2 dysfunction in RTT patients, in which seemingly normal development is followed by regression, has not been explained by molecular studies of MeCP2, although it has been reported that the accumulation of mCA during development parallels the onset of RTT features [23]. Furthermore, the degree to which patterns of DNA methylation, including mCG, mCA, and oxidized mC (such as hmC) are altered in MeCP2-mutant neurons has yet to be determined, and it remains unclear whether such changes could contribute to RTT pathogenesis. Other findings, such as a global decrease in RNA expression in MeCP2-mutant cells [39,49,50] and a decreased nuclear size [49,51,52], also remain unexplained by current models of MeCP2 function.

MECP2 AS AN ORGANIZER OF CHROMATIN ARCHITECTURE

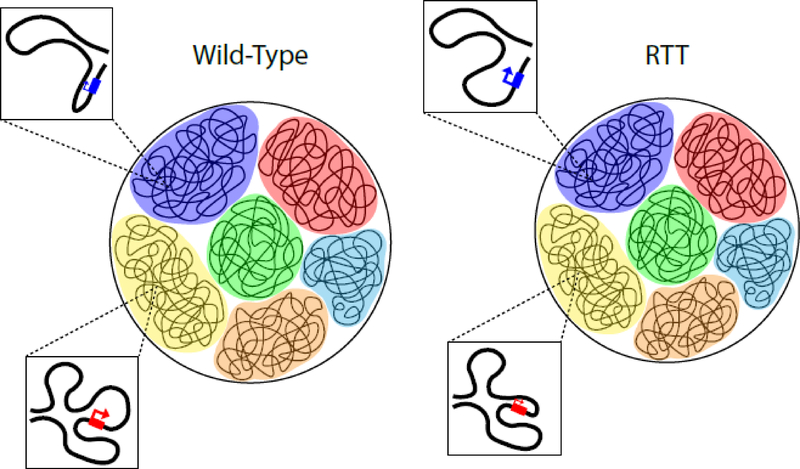

The large number of critical findings that have been difficult to explain with current mechanisms prompts us to articulate a model by which MeCP2 acts to modulate gene expression: We propose that MeCP2 functions primarily as a global organizer of chromatin architecture. In this model, MeCP2 binds to particular methylated DNA sequences across the genome and, through interactions with other proteins such as NCoR, facilitates a three-dimensional chromatin state that allows for precise and coordinated gene expression at a genome-wide level. Loss of MeCP2 and subsequent perturbation of the global chromatin architectural state would lead to subtle changes in the expression of many different genes, increasing transcription of some genes but sterically hindering the transcription of others, directly or indirectly (Figure 1). A particular gene’s direct sensitivity to MeCP2 dysfunction would therefore be governed by physical factors in three-dimensional space, such as its genomic location and physical proximity to heterochromatin. Perturbations in chromatin architecture due to loss of MeCP2 would lead to a decrease in nuclear size, which in turn could theoretically explain the global decrease in RNA expression. This model is partially supported by previous findings that MeCP2 may act to compact chromatin [53,54], alter heterochromatin size [52,55], and maintain chromatin loops [56,57], as discussed in two previous reviews [18,58]. Careful interrogation of the physical organization of the three-dimensional genome in neurons lacking MeCP2 will test this hypothesis. Ultimately, it is our hope that a greater understanding of the molecular function of MeCP2 will reveal new opportunities to develop effective therapeutics for not only RTT but also MDS.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the effects of MeCP2 as a global organizer of chromatin architecture within the nucleus. In this model, loss of MeCP2 in RTT nuclei (right) results in a subtle perturbation of the global chromatin architectural state and a decrease in nuclear size compared to wild-type nuclei (left). This leads to subtle changes in the expression of many different genes, directly increasing transcription of some genes (blue color, top insets) but sterically hindering the transcription of other genes (red color, bottom insets) based on their genomic positions and physical locations in three-dimensional space.

HIGHLIGHTS.

MeCP2 modulates cell type-, cellular compartment-, and developmental stage-specific gene expression programs

Long genes with high levels of gene body DNA methylation tend to be upregulated in MeCP2-mutant cells

Both cell- and non-cell-autonomous changes in gene expression are present in Rett syndrome

MeCP2 likely functions as an architectural protein, organizing nuclear chromatin in 3-dimensional space and globally facilitating gene transcription

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is sponsored by NIH grants R01NS081054, R01NS102731 and R01MH111719 to Z.Z.. Z.Z. is a Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Nothing Declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaenisch R, Bird A: Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet 2003, 33 Suppl:245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith ZD, Meissner A: DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet 2013, 14:204–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schübeler D: Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature 2015, 517:321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fasolino M, Zhou Z: The Crucial Role of DNA Methylation and MeCP2 in Neuronal Function. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klose RJ, Bird AP: Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci 2006, 31:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis JD, Meehan RR, Henzel WJ, Maurer-Fogy I, Jeppesen P, Klein F, Bird A: Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA. Cell 1992, 69:905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY: Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet 1999, 23:185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Christodoulou J, Clarke AJ, Bahi-Buisson N, Leonard H,Bailey MES, Schanen NC, Zappella M, et al. : Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol 2010, 68:944–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chahrour M, Zoghbi HY: The story of Rett syndrome: from clinic to neurobiology. Neuron 2007, 56:422–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lombardi LM, Baker SA, Zoghbi HY: MECP2 disorders: from the clinic to mice and back. J Clin Invest 2015, 125:2914–2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nan X, Campoy FJ, Bird A: MeCP2 is a transcriptional repressor with abundant binding sites in genomic chromatin. Cell 1997, 88:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A: Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 1998, 393:386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe AP: Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet 1998, 19:187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STC, Qin J, Zoghbi HY: MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science 2008, 320:1224–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Shachar S, Chahrour M, Thaller C, Shaw CA, Zoghbi HY: Mouse models of MeCP2 disorders share gene expression changes in the cerebellum and hypothalamus. Hum Mol Genet 2009, 18:2431–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y-T, Goffin D, Johnson BS, Zhou Z: Loss of MeCP2 function is associated with distinct gene expression changes in the striatum. Neurobiol Dis 2013, 59:257–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson BS, Zhao Y-T, Fasolino M, Lamonica JM, Kim YJ, Georgakilas G, Wood KH, Bu D, Cui Y, Goffin D, et al. : Biotin tagging of MeCP2 in mice reveals contextual insights into the Rett syndrome transcriptome. Nat Med 2017, 23:1203–1214.** This study developed a Cre-dependent biotin tagging approach to identify cell type-specific gene expression changes in hemizygous male and heterozygous female mouse models of RTT. The authors found that MeCP2 dysfunction leads to cell type- and mutation-specific gene expression changes that vary between cellular compartments, and also uncovered non-cell-autonomous effects on gene expression.

- 18.Lyst MJ, Bird A: Rett syndrome: a complex disorder with simple roots. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tudor M, Akbarian S, Chen RZ, Jaenisch R: Transcriptional profiling of a mouse model for Rett syndrome reveals subtle transcriptional changes in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99:15536–15541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen WG, Chang Q, Lin Y, Meissner A, West AE, Griffith EC, Jaenisch R, Greenberg ME: Derepression of BDNF transcription involves calcium-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2. Science 2003, 302:885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinowich K, Hattori D, Wu H, Fouse S, He F, Hu Y, Fan G, Sun YE: DNA methylation-related chromatin remodeling in activity-dependent BDNF gene regulation. Science 2003, 302:890–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabel HW, Kinde B, Stroud H, Gilbert CS, Harmin DA, Kastan NR, Hemberg M, Ebert DH, Greenberg ME: Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature 2015, 522:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Chen K, Lavery LA, Baker SA, Shaw CA, Li W, Zoghbi HY: MeCP2 binds to nonCG methylated DNA as neurons mature, influencing transcription and the timing of onset for Rett syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112:5509–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stroud H, Su SC, Hrvatin S, Greben AW, Renthal W, Boxer LD, Nagy MA, Hochbaum DR,Kinde B, Gabel HW, et al. : Early-Life Gene Expression in Neurons Modulates Lasting Epigenetic States. Cell 2017, 171:1151–1164.e16. 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniatis T, Reed R: An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature 2002, 416:499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Renthal W, Boxer LD, Hrvatin S, Li E, Silberfeld A, Nagy MA, Griffith EC, Vierbuchen T, Greenberg ME: Characterization of human mosaic Rett syndrome brain tissue by single-nucleus RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0270-6.* This study developed a single-nucleus sequencing technique that was used to profile individual nuclei from both female RTT mouse models and human post-mortem brains. The authors identified cell type-specific upregulation of genes with high gene body methylation in both mouse and human brains, and also identified the presence of non-cell-autonomous gene expression changes due to loss of MeCP2.

- 27.Samaco RC, Neul JL: Complexities of Rett syndrome and MeCP2. J Neurosci 2011, 31:7951–7959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christodoulou J, Grimm A, Maher T, Bennetts B: RettBASE: The IRSA MECP2 variation database-a new mutation database in evolution. Hum Mutat 2003, 21:466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyst MJ, Ekiert R, Ebert DH, Merusi C, Nowak J, Selfridge J, Guy J, Kastan NR, Robinson ND, de Lima Alves F, et al. : Rett syndrome mutations abolish the interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor. Nat Neurosci 2013, 16:898–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh RP, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Nikitina T, Gierasch LM, Woodcock CL: Rett syndrome causing mutations in human MeCP2 result in diverse structural changes that impact folding and DNA interactions. J Biol Chem 2008, 283:20523–20534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho KL, McNae IW, Schmiedeberg L, Klose RJ, Bird AP, Walkinshaw MD: MeCP2 binding to DNA depends upon hydration at methyl-CpG. Mol Cell 2008, 29:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballestar E, Yusufzai TM, Wolffe AP: Effects of Rett syndrome mutations of the methyl-CpG binding domain of the transcriptional repressor MeCP2 on selectivity for association with methylated DNA. Biochemistry 2000, 39:7100–7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goffin D, Allen M, Zhang L, Amorim M, Wang I-TJ, Reyes A-RS, Mercado-Berton A, Ong C, Cohen S, Hu L, et al. : Rett syndrome mutation MeCP2 T158A disrupts DNA binding, protein stability and ERP responses. Nat Neurosci 2011, 15:274–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamonica JM, Kwon DY, Goffin D, Fenik P, Johnson BS, Cui Y, Guo H, Veasey S, Zhou Z: Elevating expression of MeCP2 T158M rescues DNA binding and Rett syndrome-like phenotypes. J Clin Invest 2017, 127:1889–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guy J, Alexander-Howden B, FitzPatrick L, DeSousa D, Koerner MV, Selfridge J, Bird A: A mutation-led search for novel functional domains in MeCP2. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27:2531–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruusvee V, Lyst MJ, Taylor C, Tarnauskaitė Ž, Bird AP, Cook AG: Structure of the MeCP2-TBLR1 complex reveals a molecular basis for Rett syndrome and related disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114:E3243–E3250.* This study solved a cocrystal structure of the MeCP2 NID and a component of the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, providing biochemical and structural evidence for the interaction between these two proteins.

- 37.Sugino K, Hempel CM, Okaty BW, Arnson HA, Kato S, Dani VS, Nelson SB: Cell-typespecific repression by methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 is biased toward long genes. J Neurosci 2014, 34:12877–12883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo JU, Su Y, Shin JH, Shin J, Li H, Xie B, Zhong C, Hu S, Le T, Fan G, et al. : Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat Neurosci 2014, 17:215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagger S, Connelly JC, Schweikert G, Webb S, Selfridge J, Ramsahoye BH, Yu M, He C, Sanguinetti G, Sowers LC, et al. : MeCP2 recognizes cytosine methylated tri-nucleotide and di-nucleotide sequences to tune transcription in the mammalian brain. PLoS Genet 2017, 13:e1006793.** Using a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches, this study found that MeCP2 binds to both mCG and mCAC with specificity. The authors also provide evidence that the in vivo binding profile of MeCP2 tracks mCG and mCAC density within genes that are upregulated due to MeCP2 dysfunction.

- 40.Raman AT, Pohodich AE, Wan Y-W, Yalamanchili HK, Lowry WE, Zoghbi HY, Liu Z: Apparent bias toward long gene misregulation in MeCP2 syndromes disappears after controlling for baseline variations. Nat Commun 2018, 9:3225.* This study developed a statistical approach to analyze gene length-dependent transcriptional changes presented by running average plots and applied it to previously published datasets, finding no statistically significant effects of gene length on MeCP2dependent gene expression.

- 41.Schanen C, Houwink EJF, Dorrani N, Lane J, Everett R, Feng A, Cantor RM, Percy A: Phenotypic manifestations of MECP2 mutations in classical and atypical Rett syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2004, 126A:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neul JL, Lane JB, Lee H-S, Geerts S, Barrish JO, Annese F, Baggett LM, Barnes K, Skinner SA, Motil KJ, et al. : Developmental delay in Rett syndrome: data from the natural history study. J Neurodev Disord 2014, 6:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skene PJ, Illingworth RS, Webb S, Kerr ARW, James KD, Turner DJ, Andrews R, Bird AP: Neuronal MeCP2 is expressed at near histone-octamer levels and globally alters the chromatin state. Mol Cell 2010, 37:457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rube HT, Lee W, Hejna M, Chen H, Yasui DH, Hess JF, LaSalle JM, Song JS, Gong Q: Sequence features accurately predict genome-wide MeCP2 binding in vivo. Nat Commun 2016, 7:11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perissi V, Jepsen K, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG: Deconstructing repression: evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet 2010, 11:109–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson PJ, Fairall L, Schwabe JWR: Nuclear hormone receptor co-repressors: structure and function. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012, 348:440–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nott A, Cheng J, Gao F, Lin Y-T, Gjoneska E, Ko T, Minhas P, Zamudio AV, Meng J, Zhang F, et al. : Histone deacetylase 3 associates with MeCP2 to regulate FOXO and social behavior. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19:1497–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lazar MA: Maturing of the nuclear receptor family. J Clin Invest 2017, 127:1123–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yazdani M, Deogracias R, Guy J, Poot RA, Bird A, Barde Y-A: Disease modeling using embryonic stem cells: MeCP2 regulates nuclear size and RNA synthesis in neurons. Stem Cells 2012, 30:2128–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Wang H, Muffat J, Cheng AW, Orlando DA, Lovén J, Kwok S-M, Feldman DA, Bateup HS, Gao Q, et al. : Global transcriptional and translational repression in human-embryonic-stem-cell-derived Rett syndrome neurons. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13:446–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R: Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nat Genet 2001, 27:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linhoff MW, Garg SK, Mandel G: A high-resolution imaging approach to investigate chromatin architecture in complex tissues. Cell 2015, 163:246–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Georgel PT, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Adkins N, Woodcock CL, Wade PA, Hansen JC: Chromatin compaction by human MeCP2. Assembly of novel secondary chromatin structures in the absence of DNA methylation. J Biol Chem 2003, 278:32181–32188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nikitina T, Shi X, Ghosh RP, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Hansen JC, Woodcock CL: Multiple modes of interaction between the methylated DNA binding protein MeCP2 and chromatin. Mol Cell Biol 2007, 27:864–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singleton MK, Gonzales ML, Leung KN, Yasui DH, Schroeder DI, Dunaway K, LaSalle JM: MeCP2 is required for global heterochromatic and nucleolar changes during activity-dependent neuronal maturation. Neurobiol Dis 2011, 43:190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horike S, Cai S, Miyano M, Cheng J-F, Kohwi-Shigematsu T: Loss of silent-chromatin looping and impaired imprinting of DLX5 in Rett syndrome. Nat Genet 2005, 37:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kernohan KD, Vernimmen D, Gloor GB, Bérubé NG: Analysis of neonatal brain lacking ATRX or MeCP2 reveals changes in nucleosome density, CTCF binding and chromatin looping. Nucleic Acids Res 2014, 42:8356–8368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Della Ragione F, Vacca M, Fioriniello S, Pepe G, D’Esposito M: MECP2, a multi-talented modulator of chromatin architecture. Brief Funct Genomics 2016, 15:420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]