SUMMARY

High-risk sharing practices among people who inject drugs (PWID) are associated with high rates of HIV transmission in several parts of the world. PWID in these regions face significant barriers to HIV testing and engagement in care, highlighting the need to develop and test interventions aimed at overcoming these barriers. Drug use and HIV are often highly stigmatized in these same settings, which raises safety concerns during the conduct of research. In preparing to address concerns about the safety and well-being of participants in an international research study, HPTN (HIV Prevention Trials Network) 074, we developed participant safety plans (PSPs) at each site to supplement local research ethics committee oversight, community engagement and usual clinical trial procedures. The PSPs were informed by systematic local legal and policy assessments as well as interviews with key stakeholders. Following PSP refinement and implementation, we assessed social impacts at each study visit to ensure continued safety. Throughout the study, five participants reported a negative social impact, with three resulting from study participation. Future research with stigmatized populations should consider using and assessing this approach to enhance participants’ safety and welfare.

Keywords: HIV prevention, people who inject drugs, clinical trials, research ethics

High-risk sharing practices among people who inject drugs (PWID) are associated with high rates of HIV transmission in several parts of the world1. PWID in these regions also face significant barriers to HIV testing and engagement in care, highlighting the need to develop and test interventions aimed at overcoming these barriers2. Drug use and HIV are often both highly stigmatized in these same settings, which raises safety concerns during the conduct of research. Accordingly, in designing and conducting a study among injection networks in Indonesia, Ukraine and Vietnam, we devised a formalized, multi-stage process to help ensure participant safety in the research by developing and implementing procedures to minimize risk and respond to social harms that might occur.

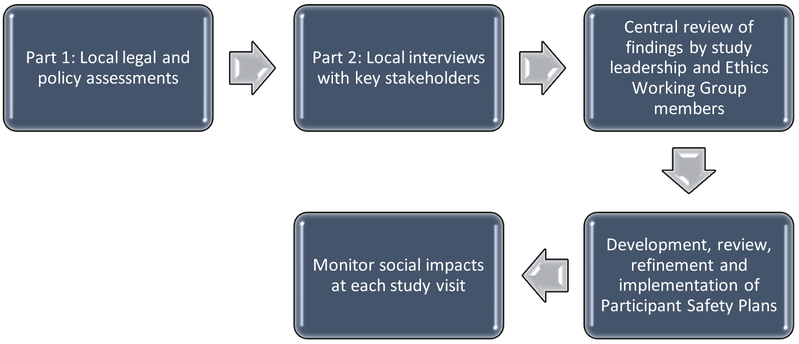

HPTN (HIV Prevention Trials Network) 074, “Integrated Treatment and Prevention for People Who Inject Drugs: A Vanguard Study for a Network-based Randomized HIV Prevention Trial Comparing an Integrated Intervention Including Supported Antiretroviral Therapy to the Standard of Care” [] involves random assignment of injection networks in Indonesia, Ukraine, and Vietnam to an integrated intervention compared to the standard of care. Details about the trial and initial results are reported elsewhere3. The study was conducted at single sites in Jakarta, Indonesia and Kyiv, Ukraine; in Vietnam, there were two study sites both within the Province of Thai Nguyen. Following initial site selection, we identified the legal and social risks at each in two phases. First, a local drug and HIV/AIDS legal/policy assessment was conducted by local experts. Second, site teams conducted a series of semi-structured qualitative interviews with key stakeholders including PWID, clinicians involved with treating drug use or HIV-infection, law enforcement officials, and those with expertise on national drug policies to help place this formal policy review into context and to identify potential risks that might be related to participation in the research. Interview topics included: 1) social attitudes towards PWID and access to care; 2) law enforcement practices that may increase PWID participant risk; and 3) and awareness of research with PWID. The Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Indonesia, the Ukrainian Institute on Public Health Policy IRB#1, and the Hanoi School of Public Health IRB approved these stakeholder interviews, which were conducted following oral consent. The local teams prepared summaries of the findings that did not include personal identifiers. The findings from all sites were reviewed by study leadership as well as members of the larger HPTN Ethics Working Group with particular expertise in ethics (JS) and laws regarding research with humans (MB). When needed, additional information was requested from the local experts and study teams. Based on the aggregate information obtained, PSPs were then developed at each site. If there was a difference of opinion regarding a particular risk, sites erred on the side of caution and incorporated such a concern into their PSPs. None of the sites experienced conflict in developing their PSPs. Draft PSPs from each site were subsequently reviewed by study leadership and the Ethics Working Group members, refined and then implemented. Finally, in order to help identify any problems associated with research participation, we assessed routinely social impacts at each study visit. Specifically, participants were asked: “Because of your participation in this study, did anything negative or bad happen to you that you have not reported to us already?” If they answered affirmatively, a series of questions was asked regarding the nature of the negative social impact.

LOCAL SITE ASSESSMENTS

A variety of laws relate to drug use at all sites, and some measures, such as mandatory medical examinations, represent both dignitary and social harms to clients at each site. Although trial enrollment was not expected to pose incremental higher risks to research participants, there were concerns related to the need to have stringent measures to protect confidentiality. Furthermore, PWID living with HIV can face layered stigma stemming from their drug behaviors and HIV status, which necessitated explicit consideration during study implementation. Finally, enforcement discretion can predictably lead to selective policing, which in turn magnifies opportunities for possible corruption and unfairness in law enforcement that have been documented in other settings.4 A brief summary of the findings at each site is presented here.

Indonesia.

Through a variety of policies, the Government of Indonesia endorses harm reduction programs such as scaling up needle and syringe exchange programs and methadone maintenence treatment in provinces with a high prevalence of PWID.5 The governmental policies demonstrate a commitment to treating PWIDs as patients more than as criminals.6,7 As long as PWIDs are not involved in criminal activity including drug dealing, trafficking or smuggling, they are referred to drug treatment rather than incarceration. The government is also increasing HIV treatment coverage among key populations, including PWIDs.6 Since HPTN 074 was aligned with these policies, the study was not anticipated to increase risks or harms to participants. Nonetheless, stigma and discrimination toward PWID in Indonesia still exist. Basic health care and HIV treatment are accessible to PWID; and the attitudes of health workers and counselors who work in drug and HIV treatment towards PWID are relatively positive. Communities not pay particular attention to PWIDs as long as they are not committing crimes in their neighborhoods. PWIDs expressed concern about keeping their HIV status confidential if they become involved in HIV-related research. All of the PWID interviewees said that involvement in previous research activities did not result in any harmful events. Thus, the social risks for potential participants in HIV-related studies were expected to be relatively minimal.

Ukraine.

To address challenges in combating illicit drug use, the Government of Ukraine: 1) identifies people who illegally use drugs;8 2) conducts compulsory medical examinations and drug testing of people who abuse drugs or psychotropic substances;9 and 3) provides voluntary treatment for people with drug addiction.10,11 The government may forcefully bring individuals who evade medical examination or testing to a drug rehabilitation facility with an authorized police representative.9 In addition, a person is exempted from criminal liability if he/she voluntarily contacted the health care facility and started drug use treatment. Yet there are concerns about how PWID are treated in the legal system, including, of course, compelled medical examinations. However, the HPTN 074 study itself was not anticipated to increase the risk of police interception at the study site since the study field site is located at the community center of a local nongovernmental organization, which has well established relationships with local stakeholders including the police. Similarly, as suggested by previous research studies in Ukraine, study participation by itself would not increase participants’ risk of stigma and discrimination. Nevertheless, a breach of confidentiality may still substantially affect study participants and result in multiple issues in different social domains (e.g., employment, interpersonal relations, medical care and the law). Finally, the underfunding of the national HIV/AIDS program may increase motivation to participate in HIV-related studies, as study participation may represent an opportunity to receive additional services.

Vietnam.

Based on a review of laws and policies regarding PWID in Vietnam, PWID, including those in prisons or mandatory detoxification centers, have equal rights to access health care services.12 Many PWID receive ART and/or methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) services, and according to Vietnamese law, these services must be provided without interference from law enforcement officials.13 Law enforcement officials cannot look for or arrest PWID at methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) clinics unless PWID directly violates a law at the clinic, such as selling drugs on clinic property.13 Similarly, personal and identifying patient information is confidential by law, thus no one may disclose patient’s information to law enforcement unless a patient violates a law or is incarcerated.12 PWID are subject to arrest if caught selling drugs and police may create a drug record for individuals who test positive for drugs.14 Any person who has a drug record and is not currently in MMT may be subject to mandatory drug treatment for up to two years through a court decision.14 Though some social stigma exists in the community, community and law enforcement officials strongly support MMT and research projects that facilitate access to it. In addition, PWID reported very positive experiences with past research participation.

PARTICIPANT SAFETY PLANS

The PSPs across all sites shared common features: protecting confidentiality; stigma and discrimination reduction tactics; emergency plan and/or contacts; staff training/standard operating procedures; and social harm monitoring (Table). However, each site developed unique approaches based on the local policy and social context and the issues identified in the local site assessments. Although some of the measures implemented as part of the PSPs at the sites are commonplace in well-conducted clinical trials (e.g., measures to maintain data security and staff training regarding good clinical practices), others are not (e.g., training on stigma, having emergency plans for social harms, and routine monitoring of social harms at study visits).

Table.

Common Features of Participant Safety Plans and Selected Implementation Measures

|

Indonesia.

The Indonesia PSP consisted of six key components: 1) specific procedures to minimize risks; 2) routine social harm assessment and reporting; 3) a safety committee to review all harms to participants; 4) providing training for staff on participant security and safety; 5) designating emergency contacts; and 6) monitoring staff interactions with participants. The procedures to minimize risk included referring to the study as an HIV prevention activity rather than one involving PWID or PLWH, making referrals for treatment without mention of the study, keeping study information separate from personally identifying information, designating all study records as health records to add legal confidentiality protections, and having all staff sign confidentiality agreements. In addition, participants could directly contact trial site leadership with concerns and were provided with their private phone numbers.

Ukraine.

The Ukraine PSP had five key components: 1) monitoring harms (at each study visit as well as providing a hotline for reporting); 2) privacy protections; 3) police interference prevention; 4) stigma and discrimination reduction, primarily by employing staff with vast experience in working with PWID; and 5) communication with stakeholders by having them attend community advisory board (CAB) meetings or arranging other opportunities for discourse. In addition to using standard procedures for ensuring data security, study procedures to minimize concerns about privacy and confidentiality were developed in collaboration with the CAB. For example, information obtained and recorded at study visits was limited only to that necessary for study conduct. Since actual names were not collected at these visits, study information was not legally required to be reported to authorities. In addition, issues related to confidentiality were included in the informed consent process for the study. To protect participants from police interference, the site was located at a community-based nongovernmental organization with long-established relationships with local police; no cases of police interference, seizure of clients for medical examination, or abuse of program clients have been reported in or near the community center. Additional engagement of the CAB with local police was used to facilitate the implementation of the PSP. Furthermore, participants were referred to human rights protection seminars that have been useful in minimizing problems with inappropriate police interventions.

Vietnam.

The Vietnam PSP had six main components: 1) minimizing risks related to confidentiality and stigma; 2) routine social harm assessment and reporting; 3) establishing an emergency plan that included frontline staff training to immediately address concerns that can be escalated as needed; 4) taking practical measures to mitigate risk; 5) providing training for staff on participant security and safety; and 6) designating emergency contacts. To help minimize stigma, the study was conducted at a location where multiple medical services are delivered, thereby not distinguishing study participants. In addition, routine CAB engagement provided a way for staff to be aware of stigma in the community. Practical measures to mitigate risk included not referring to the study as involving PWID or PLWH, using targeted recruitment in lieu of doing so in the general population, using participant identification numbers and not names, using standard data security measures supplemented with staff signing confidentiality statements, monitoring staff interactions with participants, and providing a private means for participants to report inappropriate staff behavior to study site leadership.

SOCIAL IMPACTS

During the HPTN 074 trial, five participants reported a negative social impact. Two of these occurred in Indonesia and were a result of law-enforcement actions that were deemed unrelated to study participation; and three resulted from participants sharing HIV information that may not have been known or revealed had these individuals not joined the study. Specifically, one participant in Vietnam reported that his girlfriend left him because of his presumed HIV status and participation in the study; another participant in Vietnam was isolated from his family and lost housing after revealing his HIV status; and a participant in Ukraine was divorced after learning his viral load. Study teams did not intervene in cases of law-enforcement actions that were unrelated to the study. However, they provided counseling and support for study-related negative social impacts at study visits. While specific provisions for long-term support of negative social impacts were not articulated in the PSPs, none of the participants required additional help. Of note, none of the sites needed to use the emergency procedures described in their PSPs during the course of the trial and none of the sites amended their PSP plan following implementation.

A systematic approach to identifying potential social harms and developing and implementing PSPs based on those potential harms prior to the implementation of research with a stigmatized population (i.e., PWID) was associated with minimal reports of social harms and successful enrollment and completion of the trial. The multi-stage process involved both local reviews of relevant laws and policies as well as in-depth interviews with key stakeholders at sites. The in-depth interviews facilitated interpretation of the actual risks that potential research participants might face during the trial. This information was then used to develop site-specific PSPs that became part of trial operations. Monitoring for social impacts was routinely performed at all sites to provide additional protection. However, the negative social impacts that were related to study participation in HPTN 074, all involved personal disclosures about HIV status to others rather than having some relationship to governmental policies or other forms of stigma from local communities and staff that were emphasized in the PSPs. Accordingly, future work in developing PSPs should consider incorporating measures to minimize the social risks associated with personal disclosures of health information.

In addition, it was challenging to ensure that we obtained accurate and current information about the laws and policies in each country as well as if and how they were enforced. We attempted to resolve this by selecting carefully the legal and policy experts to facilitate the initial legal and policy review as well as stakeholders we interviewed.

In designing this approach, we incorporated elements that have been described previously to help identify and manage the social risks associated with research with stigmatized populations. An approach used for this purpose with good results in similar settings is a “rapid policy assessment” (RPA).15 Yet the version of the RPA that was previously commissioned for an international HIV prevention trial involving PWID involved substantial time and resources and was somewhat distinct from other important community engagement activities related to the trial.16

Other approaches to making similar assessments have been described. For example, the American Bar Association’s Rule of Law Initiative published an HIV/AIDS Legal Assessment Tool.17 The approach is designed “to conduct assessments of the legal rights of PLHIV and key populations, providing a roadmap for addressing HIV-related discrimination and ensuring States’ compliance with the applicable international legal standards.”17, p 3. As in a RPA, and the related approach we employed, the tool specifically assesses both de jure and de facto policies. The latter necessitates engagement with key stakeholders in order to understand actual enforcement practices. However, the assessment is a much broader and resource intensive undertaking that primarily relates to the law. Of note, the endeavor is not necessarily focused on the particular incremental social risks that might be faced in the context of proposed research.

Also of relevance are best practices designed particularly for research involving men who have sex with men in stigmatized settings, Respect, Protect, Fulfill, that was developed as a joint effort of amfAR, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights, and the United Nations Development Program.18 The practices underscore the critical importance of community engagement and provide checklists for key stakeholders and issues (researchers, community organizations, volunteers, and staff and security) that should mitigate social harms in this context. Nevertheless, in relevant settings there is arguably a need to supplement this approach with a more formalized legal assessment such as the one we describe here. In addition, there may be additional issues of particular relevance to PWID that are not captured in these best practices.

In conclusion, while we cannot necessarily attribute the occurrence of only minimal negative social impacts to the PSPs, future research with stigmatized populations should consider using, assessing, and revising this approach to enhance participants’ safety and welfare, which in turn should work to promote participants’ willingness to join a study and continue in it. In order to establish best practices in the field, reports of doing so would be most welcome.

Figure.

Participant Safety Plan Development, Implementation and Assessment

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors appreciate the contributions of the experts at each site who prepared reports and conducted interviews regarding the local legal and policy issues relevant to the research as well as the stakeholders who participated in in-depth interviews. Specifically, in Indonesia Diah Setia Utami provided information related to current policy; in Ukraine Iryna Pykalo, Olena Makarenko and Tetiana Kiriazova conducted interviews; and in Vietnam, Nguyen Thi Minh Tam helped to develop the legal analysis and Nguyen Duc Vuong facilitated interviews. Katie Mollan, Ilana Trumble, and Brett S. Hanscom, provided assistance with identifying the number of reported negative social impacts and offered feedback on earlier versions of the manuscript. Erica Hamilton helped coordinate manuscript reviews. Finally, we would like to thank the participants in HPTN 074 for their invaluable contributions to this research.

Support: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH); award numbers UM1AI068619 [HPTN Leadership and Operations Center], and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Unrelated to the work described in this paper, Dr. Sugarman serves on the Merck KGaA Bioethics Advisory Panel and Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee; and the IQVIA Ethics Advisory Panel. He receives consulting income for this work and support for travel to meetings of these committees. Mr. Barnes is a partner in an international law firm that represents universities, academic medical centers and industry entities in matters related to clinical trials.

Presentation: Some of the information described in this paper was presented as a poster at the Global Forum for Bioethics in Research, Bangkok, Thailand, November 28–29, 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Csete J, Kamarulzaman A, Kazatchkine M, et al. Public health and international drug policy. Lancet 2016; 387(10026): 1427–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jürgens R, Csete J, Amon JJ, Baral S, Beyrer C. People who use drugs, HIV, and human rights. Lancet 2010;376 (9739): 475–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller WC, Hoffman I, Hanscom B, et al. Impact of systems navigation and counseling on ART, SUT and death in PWID: HPTN 074, Abstract 1097 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, Massachusetts, 4–7 March 2018. Available at: http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/impact-systems-navigation-and-counseling-art-sut-and-death-pwid-hptn-074 (accessed 4/4/2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decker MR, Crago AL, Chu SK, et al. Human rights violations against sex workers: burden and effect on HIV. Lancet 2015; 385(9963):186–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia Regulation No. 55 Year of 2015 on “Harm Reduction Of People Who Inject Drugs”. July 29, 2015. http://ditjenpp.kemenkumham.go.id/arsip/bn/2015/bn1238-2015.pdf (accessed 29/3/2018).

- 6.Joint Regulation among Supreme Court Republic of Indonesia No. 01/PB/MA/III/2014 – Minister of Justice and Human Rights Republic of Indonesia No. 03/2014 – Minister of Health, Republic of Indonesia No. 11/2014 – Minister of Social Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, No. 03/2014 – High Attorney, Republic of Indonesia, No. PER-005/A/JA/03/2014 – Chief of Indonesia National Police No. 1/2014 – Chief of Indonesia National Narcotics Board, No. 01/III/2014/BNN, on “Rehabilitation Management for Drug Addicts and Victims of Narcotics Abuse”. March 11, 2014. http://bali.bnn.go.id/cms/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/PERATURAN-BERSAMA-KETUA-MAHKAMAH-AGUNG-DKK.pdf (accessed 29/3/2018).

- 7.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia Regulation No. 2415 Year of 2011 on “Medical Rehabilitation of Narcotics Addict, Narcotics Abuse and Victim of Narcotic Abuse”. December 1, 2011. https://www.kebijakanaidsindonesia.net/id/dokumen-kebijakan/send/17-peraturan-pusat-national-regulation/351-permenkes-ri-no-2415-tahun-2011-tentang-rehabilitasi-medis-pecandu-penyalahguna-dan-korban-penyalahgunaan-narkotika (accessed on 29/3/2018).

- 8.Cabinet of Ministries of Ukraine. Order № 735 “On approval of the strategy for drug policy for the period to 2020”, 28 August 2013. http://zakon5.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/735-2013-%D1%80 (accessed 29.03.2018).

- 9.Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Order № 417 “On approval of the medical examination of persons who abuse drugs or psychotropic substances”, 16 June1998. http://zakon0.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/ru/z0482-98 (accessed 29.03.2018).

- 10.The Law of Ukraine “On measures to combat illicit trafficking of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and precursors and their abuse”. http://zakon3.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/62/95-%D0%B2%D1%80 (accessed 29.03.2018).

- 11.The Law of Ukraine “Fundamentals of Ukrainian Health Care”. http://zakon0.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2801-12 (accessed 29.03.2018).

- 12.Government of Vietnam. Law on the immunodeficiency syndrome acquired (HIV/AIDS) Prevention and Control in 2006. http://www.moj.gov.vn/vbpq/lists/vn%20bn%20php%20lut/view_detail.aspx?itemid=15096 (accessed: 26/03/2018).

- 13.Government of Vietnam. The constitution in 2016, the Law on Drug abuse treatment using drug replacement therapy, the Decree No.90. https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/The-thao-Y-te/Nghi-dinh-90-2016-N%C3%90-CP-dieu-tri-nghien-cac-chat-dang-thuoc-phien-bang-thuoc-thay-the-315448.aspx (accessed: 26/03/2018).

- 14.Government of Vietnam. Policy on Drugs and HIV/AIDS in 2000 and amended on 2008. http://vanban.chinhphu.vn/portal/page/portal/chinhphu/hethongvanban?class_id=1&mode=detail&document_id=80180 (accessed: 26/3/2018).

- 15.Family Health International. HPTN 058: Rapid policy assessment for China and Thailand Family Health International, Research Triangle Park, NC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugarman J, Rose SM, Metzger D. Ethical issues in HIV prevention research with people who inject drugs. Clin Trials 2014; 11: 239–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative HIV/AIDS legal assessment tool: assessment methodology manual. Washington, DC: American Bar Association, 2012; Available at: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/roli/misc/aba_roli_hiv_aids_legal_assessment_tool_11_12.authcheckdam.pdf (accessed 29/3/2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18.amfAR, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, the Johns Hopkins Center for Public Health and Human Rights, and the United Nations Development Program. Respect, protect, fulfill: best practices guidance in conducting HIV research with gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in rights-constrained environments. Available at: http://www.amfar.org/uploadedFiles/_amfarorg/Articles/Around_The_World/GMT/2015/RespectProtectFulfill-MSM-ResearchGuidance-Rev2015-English.pdf (accessed 29/03/2018).