Abstract

Coxiella burnetii, the etiologic agent of Q fever, replicates in an intracellular phagolysosome with pH between 4 and 5. The impact of this low pH environment on antimicrobial treatment is not well understood. An in vitro system for testing antibiotic susceptibility of C. burnetii in axenic media was set up to evaluate the impact of pH on C. burnetii growth and survival in the presence and absence of antimicrobial agents. The data show that C. burnetii does not grow in axenic media at pH 6.0 or higher, but the organisms remain viable. At pH of 4.75, 5.25, and 5.75 moxifloxacin, doxycycline, and rifampin are effective at preventing growth of C. burnetii in axenic media, with moxifloxacin and doxycycline being bacteriostatic and rifampin having bactericidal activity. The efficacy of doxycycline and moxifloxacin improved at higher pH, whereas rifampin activity was pH independent. Hydroxychloroquine is thought to inhibit growth of C. burnetii in vivo by raising the pH of typically acidic intracellular compartments. It had no direct bactericidal or bacteriostatic activity on C. burnetii in axenic media, suggesting that raising pH of acidic intracellular compartments is its primary mechanism of action in vivo. The data suggest that doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine are primarily independent bacteriostatic agents.

Subject terms: Bacterial infection, Antibiotics

Introduction

Coxiella burnetii is a gram-negative bacterium that is the etiologic agent of the human disease Q fever. This bacterium has a reduced genome and therefore requires infection and establishment of an intracellular niche for replication. C. burnetii replicates in mammalian host cells within the low pH environment of the phagolysosome1. C. burnetii can infect a wide variety of vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and birds2. The most common reservoirs associated with human infection are domesticated farm animals and livestock, such as goats, sheep, and cows2. C. burnetii can be released into the environment in large numbers by shedding from infected animals in the placenta, feces, urine, or milk. C. burnetii has a very low infectious dose, with as few as 1–10 organisms capable of initiating an infection3. Q fever is most commonly spread via inhalation of aerosols that contain the bacteria. Q fever is present in most parts of the world.

C. burnetii has two distinct morphological forms, a small cell variant (SCV) and a large cell variant (LCV) which exist in a biphasic development cycle4. The SCVs are 0.2 to 0.5 μm in length, while the LCVs are more than 1 μm in length4. C. burnetii in the LCV stage are metabolically and reproductively active and found in the phagolysosome5. As SCVs, C. burnetii have reduced metabolic activity and exhibit spore-like characteristics, such as resistance to desiccation, ultraviolent light, and high temperatures. Much like bona fide bacterial spores, the SCV can remain viable in the environment for long periods of time, potentially over a year6. Upon infection, SCVs undergo morphological changes and convert into LCVs as they replicate exponentially before eventual transition back to SCVs5.

Q fever manifests in two forms, acute and chronic disease. Acute Q fever is characterized by a self-limiting febrile illness, often associated with flu-like symptoms including fever, headache, chills, and myalgia. More severe symptoms can include hepatitis and pneumonia, and may result in hospitalization. Chronic Q fever presents most commonly as either culture negative endocarditis or vascular infection. It is estimated that 2–5% of C. burnetii infections will develop into chronic Q fever7. It may take many months, if not years after the initial C. burnetii infection for chronic Q fever to become apparent. Patients with pre-existing valvulopathies or vascular disease are more at risk for development of chronic Q fever8. These chronic infections are difficult to treat, and are typically fatal if untreated9.

Antibiotic therapies are recommended for the treatment of Q fever. For acute Q fever, 100 mg doxycycline twice a day for two weeks is the advocated treatment10. Chronic Q fever, conversely, is much more difficult to treat. A 100 mg dose of doxycycline twice daily and 200 mg hydroxychloroquine three times a day is recommended. Therapy should continue for a minimum of 18 months, and may be required to continue for years10. Alternative treatments include fluoroquinolones, macrolides, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and rifampin11, but alternative treatments have been associated with greater risk of relapse and longer treatment times compared to the recommended treatment of doxycycline plus hydroxychloroquine12. It has been suggested that the ability of hydroxychloroquine to increase the pH of the phagolysosomal compartments where C. burnetii replicates increases the bactericidal activity of doxycycline and thereby makes the combination therapy more effective13,14, but a mechanism by which higher pH increases bactericidal activity has not been proposed.

There are several challenges in the treatment of chronic Q fever. Even with proper treatment, some cases can persist for more than 5 years15. Compliance is difficult for such a long therapeutic regimen, and incomplete clearance followed by a return of symptoms is not uncommon7. There are also many adverse side effects associated with long term use of doxycycline, including loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, retinopathy, and sensitivity to sun exposure16.

C. burnetii can be grown in media without the need for host cell infection. Acidified citrate cysteine media (ACCM-2) is an axenic media which replicates the conditions within the phagolysosome, supporting growth of C. burnetii without the variables associated with host cell lines17. Limited studies have been done with antibiotic treatments in ACCM-218. C. burnetii is metabolically active at a pH between 4 and 5, which is naturally found within the phagolysosome19. The impact of this low pH environment on antibiotic treatment of C. burnetii is not well understood. Use of ACCM-2 allows the pH of the C. burnetii environment to be manipulated, thus allowing direct testing of the effects of pH on the life cycle of C. burnetii. The aim of this study is to investigate the role that pH plays on the efficacy of antibiotics against C. burnetii.

Results

pH dependence of C. burnetii growth in axenic media

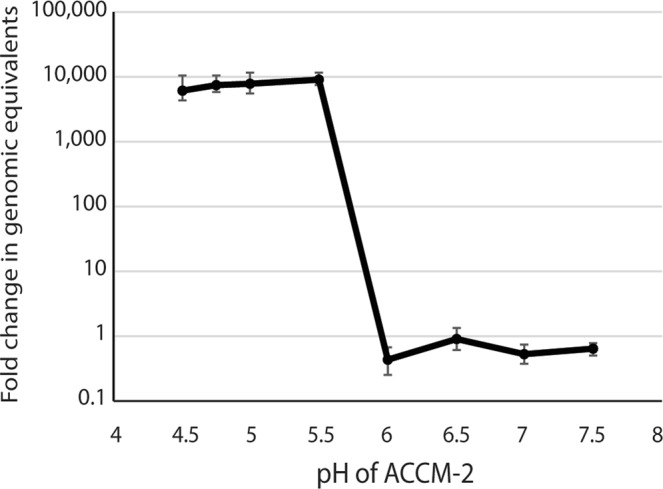

To establish the impact of pH on the ability of C. burnetii to replicate in ACCM-2 media, growth of C. burnetii Nine Mile Phase 2 (NMP2) was measured in ACCM-2 liquid culture at pH ranging from 4.5 to 7.5. The greatest expansion was observed at pH 5.5 with a 7-day fold change in NMP2 genomic equivalents of 9,040. The fold change in NMP2 genomic equivalents decreased with increasing acidity of the media with 7675, 7562, and 6127 fold expansion at pH 5, 4.75, and 4.5, respectively. No growth was detected at pH 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, and 7.5 (Fig. 1). The lack of growth at pH 6 and higher correlates well with a previous report of reduced C. burnetii metabolic activity at pH 6 and above19.

Figure 1.

Growth of Coxiella burnetii Nine Mile Phase 2 in ACCM-2 medium. Genomes in the culture were calculated at the start of the culture and again on day 8 using qPCR. Robust growth of C. burnetii was observed at pH 5.5 and lower, but not at pH 6 and higher. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Antibiotic susceptibility of C. burnetii in axenic media

To establish an assay for C. burnetii antibiotic susceptibility in ACCM-2 media, a panel of antibiotics were tested for the ability to prevent growth of C. burnetii. In this assay, cultures at day 4 of growth were treated with antibiotics. As previously demonstrated, use of C. burnetii at day 4 of growth in ACCM-2 ensured that the exposed organisms were almost all in the LCV form and metabolically active20. The use of already actively replicating organisms reduced the amount growth in untreated cultures compared to Fig. 1. With the exception of rifampin, antibiotics were tested at 10 μg/ml, which is above the peak serum concentration (Cmax) for all of these antibiotics used at standard dosing16. Rifampin was an exception because it has a higher Cmax and was therefore used at 20 μg/ml. In the absence of antibiotics, NMP2 expanded 63-fold in these cultures (Table 1). Doxycycline, rifampin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin were very effective at preventing C. burnetii growth in this system with fold expansion between 0.05 and 0.11 (Table 1). In contrast, the macrolides azithromycin and erythromycin had very little impact on C. burnetii growth in ACCM-2 with fold changes of 53.2 and 58.6, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Efficacy of antibiotics against C. burnetii in ACCM-2 culture.

| Antibiotic | Concentration (μg/ml) | Fold change (95% CI) | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| untreated | — | 62.9 (46.7–83.1) | − |

| Doxycycline | 10.0 | 0.09 (0.07–0.11) | + |

| Rifampin | 20.0 | 0.11 (0.09–0.13) | + |

| Azithromycin | 10.0 | 53.2 (37.1–70.6) | − |

| Erythromycin | 10.0 | 58.6 (47.6–70.7) | − |

| Moxifloxacin | 10.0 | 0.06 (0.05–0.13) | + |

| Levofloxacin | 10.0 | 0.09 (0.05–0.13) | + |

| Ciprofloxacin | 10.0 | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) | + |

Antibiotic efficacy with increasing pH

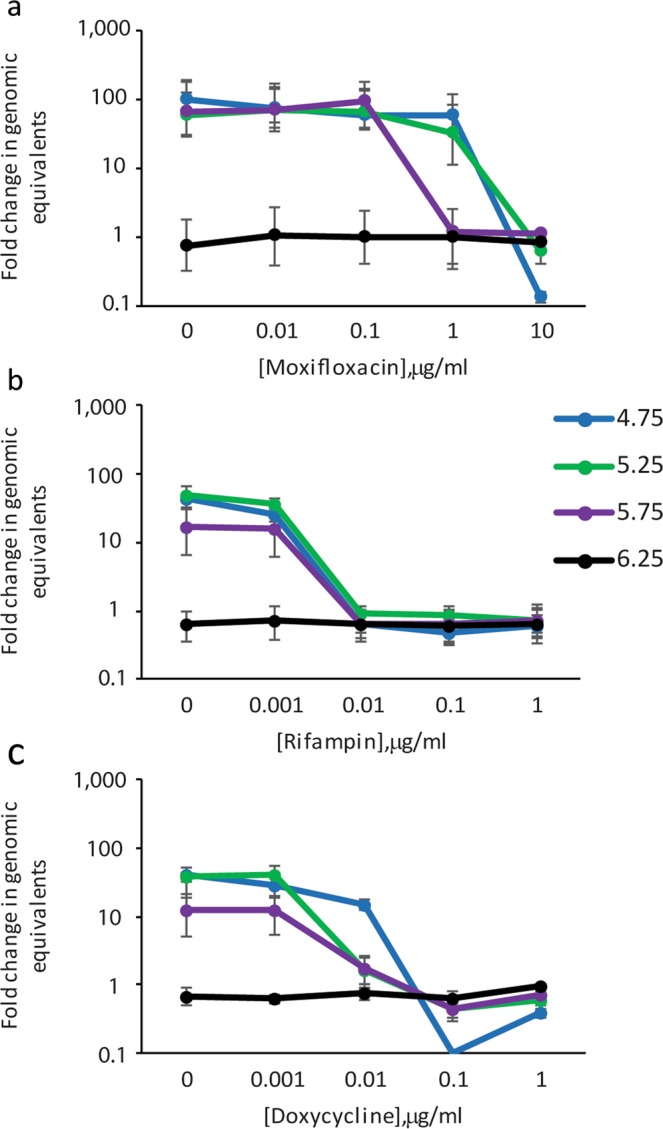

To compare efficacy of three different classes of antibiotics against C. burnetii in ACCM-2 and to evaluate the role of pH in antibiotic efficacy, NMP2 was exposed to doses of doxycycline, rifampin, and moxifloxacin at a variety of pH using actively growing cultures of NMP2. Without antibiotics added, the NMP2 expanded 40–100 fold at optimum pH of 4.75, and had no growth at all at pH 6.25 (Fig. 2). All three antibiotics were effective at preventing growth at pH 4.75, 5.25, and 5.75 (Fig. 2). Rifampin and doxycycline had similar potency in this system, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.01 μg/ml at pH 4.75, 5.25, and 5.75. Moxifloxacin was less potent and had an MIC of 10 μg/ml at pH 4.75 and 5.25, and an MIC of 1 μg/ml at pH 5.75.

Figure 2.

C. burnetii growth in ACCM-2 in the presence of moxifloxacin (a), rifampin (b), and doxycycline (c) at varying pH. Genomes in the culture were calculated at the start of the culture and again on day 7 using qPCR. The ratios of the means of genomes at day 7 to the means of genomes at the beginning of the culture were calculated to determine fold change in genomic equivalents. The standard errors of the means of genome equivalents were calculated and used to determine the upper and lower bounds of the ratios (fold change). The error bars depict the upper and lower bounds of fold change for each condition.

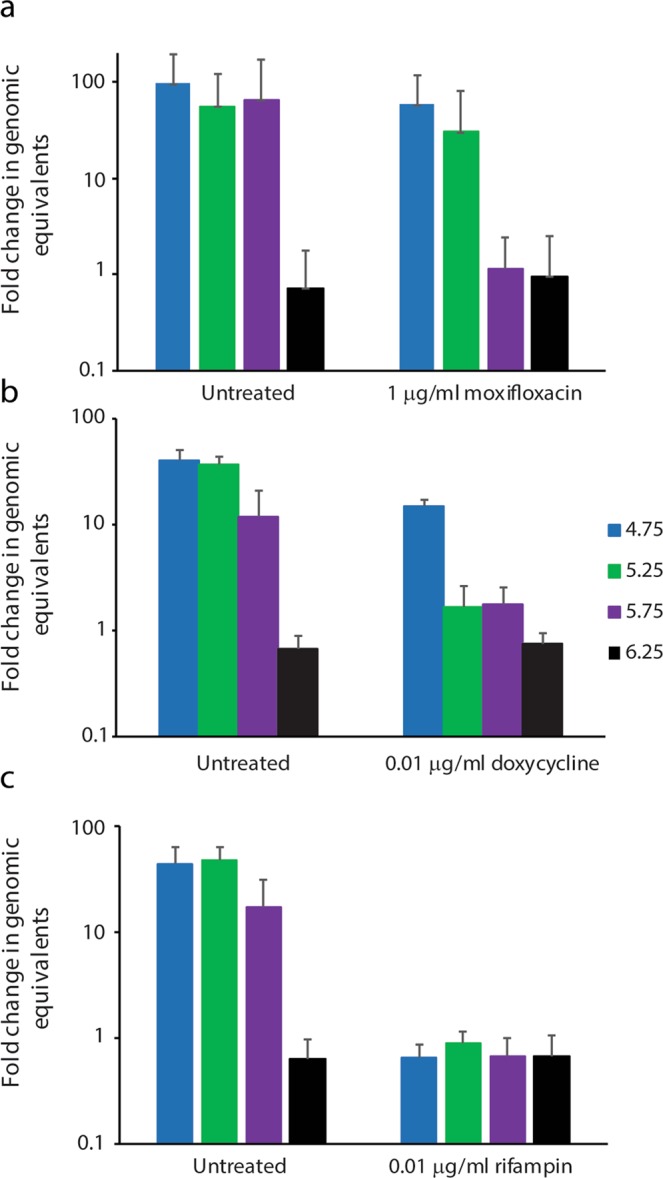

The higher MICs for moxifloxacin at pH 4.75 and 5.25 suggests that pH may play a role in efficacy of antibiotics. This is better visualized in Fig. 3 where the same fold change data for NMP2 is displayed in untreated versus antibiotic treatment at a concentration near the MIC for the three antibiotics. Susceptibility of NMP2 to rifampin is unaffected by pH changes, whereas doxycycline is slightly less effective at pH 4.75 and moxifloxacin has reduced efficacy at pH 4.75 and 5.25 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Moxifloxacin and doxycycline are less effective at reducing growth of C. burnetii at more acidic pH. Genomes in the culture were calculated at the start of the culture and again on day 7 using qPCR. The ratios of the means of genomes at day 7 to the means of genomes at the beginning of the culture were calculated to determine fold change in genomic equivalents. The standard errors of the means of genome equivalents were calculated and used to determine the upper and lower bounds of the ratios (fold change). The error bars depict the upper and lower bounds of fold change for each condition.

Viability after antibiotic treatment

To determine if there was any bactericidal effect of these antibiotics in ACCM-2, at the end of the 7 day culture NMP2 was plated on ACCM-2 agar plates without antibiotics. Growth was evaluated after 14 days incubation on the agar plates. For moxifloxacin and doxycycline, growth on the agar plate was observed no matter what concentration of antibiotic was used in the 7 day culture (Table 2), indicating that these drugs have only bacteriostatic activity in this system. In a separate experiment, doxycycline concentrations of 5 and 10 μg/ml were also bacteriostatic for NMP2 (data not shown). For rifampin, no growth on agar plates was detected at pH 4.75 and 5.25 after culture with dosages of 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μg/ml, as well as pH 5.75 after culture with dosages of 0.01 and 1.0 μg/ml (Table 2). This demonstrates bactericidal activity against C. burnetii for rifampin in this system. The data also show that the lack of C. burnetii growth at pH 6.25 and above is a bacteriostatic effect and not due to killing of C. burnetii.

Table 2.

Viability of C. burnetii after one week culture in ACCM-2 with the indicated antibiotics. A “+” indicates growth on ACCM-2 plates after dilution from the treated culture. A “-” indicates no growth.

| pH | [moxifloxacin], μg/ml | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | |

| 4.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| [doxycycline], μg/ml | |||||

| pH | 0 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 |

| 4.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| [rifampin], μg/ml | |||||

| pH | 0 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 |

| 4.75 | + | + | − | − | − |

| 5.25 | + | + | − | − | − |

| 5.75 | + | + | − | + | − |

| 6.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

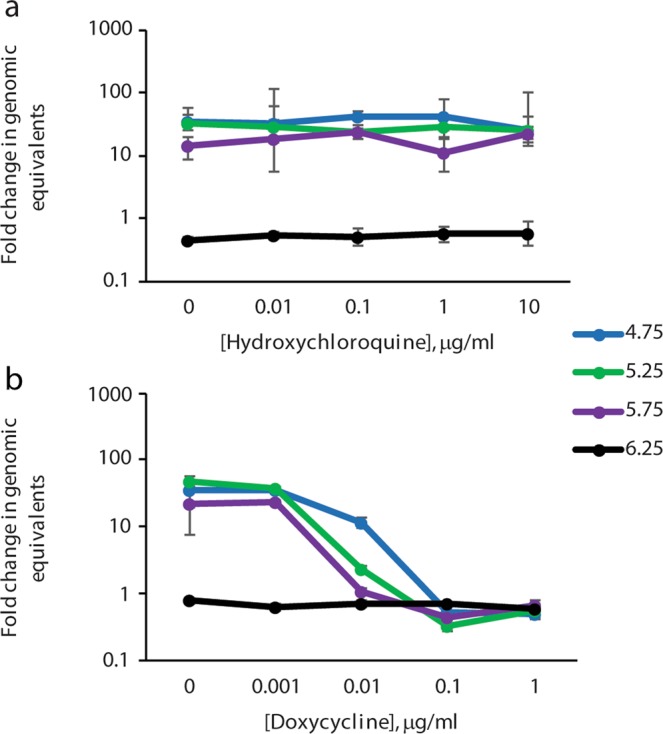

Effect of hydroxychloroquine in axenic media

Combination therapy with doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine is recommended for patients with chronic Q fever10. Hydroxychloroquine is known to raise the pH of vacuoles that support C. burnetii replication by facilitating proton leakage out of these vacuoles21. We tested the effect of hydroxychloroquine on C. burnetii growth and survival in the ACCM-2 system at various buffered pHs. Hydroxychloroquine had no effect on growth of C. burnetii in this system regardless of the pH of the media (Fig. 4), suggesting that without the ability to impact intravacuolar pH, hydroxychloroquine is ineffective. As expected, no changes were observed in the pH of ACCM-2 media after the addition of hydroxychloroquine. This was evaluated by preparing aliquots of ACCM-2 media at a pH of 4.75, 5.25, 5.75, and 6.25 followed by addition of hydroxychloroquine to each aliquot at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. The pH of the media did not change after addition of the hydroxychloroquine. Treatment of cultures with varying doses of doxycycline with a fixed dose of 10 μg/ml hydroxychloroquine resulted in growth inhibition very similar to use of doxycycline alone (Fig. 4). Evaluation of the viability of NMP2 after treatment with hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with doxycycline demonstrated that hydroxychloroquine had no impact on C. burnetii viability nor did it change the bacteriostatic activity of doxycycline in ACCM-2 (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Impact of hydroxychloroquine on C. burnetii growth at different pH. In (a), C. burnetii were exposed to the indicated concentrations of hydroxychloroquine and no effect on growth was observed. In (b), hydroxychloroquine was added at 10 μg/ml to all of the cultures and doxycycline was titrated. The ratios of the means of genomes at day 7 to the means of genomes at the beginning of the culture were calculated to determine fold change in genomic equivalents. The standard errors of the means of genome equivalents were calculated and used to determine the upper and lower bounds of the ratios (fold change). The error bars depict the upper and lower bounds of fold change for each condition.

Table 3.

Viability of C. burnetii after one week culture in ACCM-2 with a titration of hydroxychloroquine or a fixed amount of hydroxychloroquine plus a titration of doxycycline.

| pH | [hydroxychloroquine], μg/ml | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | |

| 4.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| [doxycycline], μg/ml (with 10 μg/ml hydroxychloroquine) | |||||

| pH | 0 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 |

| 4.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5.75 | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6.25 | + | + | + | + | + |

A “+” indicates growth on ACCM-2 plates after dilution from the treated culture. A “−“ indicates no growth.

Discussion

The data presented here demonstrate the establishment of an axenic system for evaluating the impact of antimicrobial agents on C. burnetii. In this system, only actively replicating C. burnetii (LCV) are challenged with antibiotics. This system does not address the impact of these drugs on the SCV form of C. burnetii. However, it is expected that most antibiotics would have little efficacy on quiescent SCV due to the targeting of pathways involved in replication and/or protein synthesis. In the axenic system that was used in this study, erythromycin and azithromycin had very little effect on C. burnetii growth. It is unclear why the two macrolides tested did not have any efficacy in this system. There is limited data suggesting that some macrolides may have benefit for Q fever patients11, but in this in vitro system there was no effect on growth. It is possible that the macrolides have some benefit but do not inhibit C. burnetii directly, but also possible that the two tested here are not effective against C. burnetii.

It has been suggested that the benefit of hydroxychloroquine/doxycycline combination therapy is a result of the ability of hydroxychloroquine to raise the pH of vacuoles supporting replication of C. burnetii and that the raised pH of the vacuoles creates an environment where doxycycline and other antibiotics take on bactericidal activity13,14. The results here do demonstrate that there is some improvement of efficacy of doxycycline and moxifloxacin in ACCM-2 when pH is raised above 4.75, but this effect seems to only be a dose effect on bacteriostatic activity. In the ACCM-2 system, no bactericidal activity was observed for doxycycline or moxifloxacin. Rifampin did display bactericidal activity but this did not appear to be pH dependent. The pH of the media did not impact rifampin efficacy. Most antimicrobial agents will have some bactericidal activity if the concentration is high enough, but if the minimum bactericidal concentration is more than 4-fold greater than the MIC, then the drug is considered bacteriostatic22. In this study, bactericidal activity was not observed for doxycycline or moxifloxacin at concentrations 10–100 fold above the MIC regardless of pH, suggesting that these drugs should be considered bacteriostatic for C. burnetii. The bacteriostatic activity of doxycycline and bactericidal activity of rifampin are consistent with activities of these drugs on other bacteria23,24. Some bactericidal effects from fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin could be possible but were not observed against C. burnetii using the methods in this study.

The observation in previous studies that doxycycline efficacy is improved when infected cells are treated with hydroxychloroquine could be related to the transport of doxycycline across membranes. Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are thought to rely on pH gradients to move across cell membranes25. This means that doxycycline will more readily move from a lower pH to a higher pH. Because the intracellular pH of C. burnetii has been estimated to be 6–6.5 when the extracellular pH is around 4.7526, doxycycline should easily move from the low pH of the vacuole or ACCM-2 media to the cytoplasm of C. burnetii. However, in infected host cells, doxycycline will also need to pass from the host cell cytoplasm into the vacuole, and this transport could be inhibited by the lower pH of the vacuole compared to the cytoplasm. Addition of hydroxychloroquine could improve transport of the doxycycline into the vacuole in vivo and make more doxycycline available for movement into the C. burnetii cytoplasm. The pH of the C. burnetii cytoplasm should rise as the pH of the vacuole is increased, but the gradient will be reduced at higher extracellular pH, and this could reduce transport of doxycycline into the C. burnetii cytoplasm. Presumably there is a net gain in availability of doxycycline within C. burnetii when the pH of the vacuole is raised by hydroxychloroquine. Thus, addition of hydroxychloroquine in vivo could shift the dose curve of doxycycline by a mechanism that would not be observable in ACCM-2.

These data raise the possibility that the primary effect of hydroxychloroquine is to prevent C. burnetii replication by raising the pH on intracellular vacuoles to a level that does not support C. burnetii replication. In this scenario, doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine both act as bacteriostatic agents by different mechanisms- doxycycline by inhibition of protein synthesis23 and hydroxychloroquine by raising pH. The benefits of combination therapy have been clearly demonstrated12, but may not be the result of imparting bactericidal activity on doxycycline. Bactericidal activity by protein synthesis inhibitors generally requires that the bacteria be actively replicating, and the presence of a bacteriostatic agent can antagonize bactericidal activity of another agent27. The effectiveness of combination therapy suggests that this is not the result of bactericidal and bacteriostatic functions working at the same time.

The bactericidal activity against C. burnetii by rifampin in this study suggests that further study of this drug as an alternative therapy for Q fever is warranted. It is not clear how well results generated in this axenic system will translate to an intracellular in vivo reality, but the utility of rifampin against Q fever in clinical cases has been noted28. For patients that cannot tolerate long-term doxycycline therapy for chronic Q fever, effective alternatives are needed. These results suggest that rifampin is an alternative that should be explored.

Methods

Bacterial and antibiotic stocks

The Coxiella burnetii strain used in this study was Nine Mile Phase 2, clone 4 (NMP2), a low virulence strain that has a large genomic deletion that removes genes responsible for the complexity of LPS side chains29. Stocks of NMP2 were prepared by growth in ACCM-2 media at pH 4.75, and freezing in sodium phosphate glutamate (SPG) buffer. Antibiotics were purchased as follows: doxycycline hyclate, ciprofloxacin, rifampin, hydroxychloroquine, erythromycin, and levofloxacin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), azithromycin dihydrate, and moxifloxacin hydrochloride (United States Pharmocopeia, Rockville, MD). Doxycycline hyclate, moxifloxacin hydrochloride, ciprofloxacin, and hydroxychloroquine stocks were prepared by dissolving in deionized water at a concentration of 1280 μg/ml. Levofloxacin was dissolved in an aqueous solution of 0.05 M NaOH at 1280 μg/ml. Erythromycin and azithromycin were dissolved in 95% ethanol at 1280 μg/ml.

pH dependence of C. burnetii growth

To evaluate the pH dependence of C. burnetii grown in ACCM-2, media was prepared as described17 and pH adjusted using 1 N NaOH. T-25 flasks containing 7 mls of ACCM-2 at pH 4.5, 4.75, 5.0. 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, and 7.5 were individually inoculated with 100 NMP2 organisms taken from frozen stocks and incubated for 8 days at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 2.5% O2. Genome equivalents were determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) from 200 μl aliquots taken on days 0 and 8.

Quantitative PCR

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μl samples using the QIAamp DNA mini kit tissue protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genomic equivalents of C. burnetii in the sample were determined by performing qPCR targeting the com1 gene as previously described30.

Antibiotic susceptibility screening

Cultures of NMP2 were inoculated with approximately 1 × 107 NMP2 per ml taken from frozen stock and grown for 8 days in ACCM-2 at pH 4.75, 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 2.5% O2. Antibiotics were added at days 0 and day 4 in sufficient quantity on both days to achieve a concentration of 10 μg/ml. This concentration was higher than the peak serum concentration (Cmax) observed in patients taking standard doses for all antibiotics except rifampin. Because of its higher Cmax, rifampin was added at 20 μg/ml. A 200 μl aliquot was taken from each culture immediately and again after 8 days incubation. Samples were analysed by qPCR and the fold change between days 0 and 8 calculated. Data presented are from two independent replicates.

Antibiotic efficacy at variable pH

Four days prior to initiation of antibiotic treatment, 20 ml of ACCM-2 at pH 4.75 was mixed in a T75 flask with 1 × 108 genome equivalents of NMP2 taken from frozen stock. The flask was incubated at 37 °C, 2.5% O2, and 5% CO2 for four days, allowing the C. burnetii to transition from the small cell variant to the large cell variant and enter the log phase of replication. After four days of growth, 200 μl of culture was transferred into T25 flasks containing 7 ml of fresh ACCM-2 at 4.75, 5.25, 5.75, or 6.25 pH in duplicate. Antibiotics were added on days 1 and day 4 in sufficient quantity on both days to achieve concentrations of 0.001. 0.01. 0.1, 1, and 10 μg/ml. A 200 μl aliquot was taken from each sample on days 0 and 7 for quantification of C. burnetii by qPCR. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration tested that resulted in less than half of the quantity of C. burnetii compared to untreated controls. On day 7, an additional aliquot of 10 μl from each culture was then transferred to an ACCM-2 agar plate at pH 4.75. The plates were incubated for two weeks at 37 °C, 2.5% O2, and 5% CO2, and colony growth was noted to determine if the cultures were viable. Although any detectable colonies on the plate would be reported as viable (+), all viable cultures had colonies too numerous to count. Separately, pH of ACCM-2 prepared at pH 4.5, 5.25, 5.75, and 6.25 was measured before and after the addition of doxycycline, moxifloxacin, rifampin, and hydroxychloroquine at 10 μg/ml to confirm that the antibiotics did not affect the pH of the cultures.

Statistical analysis

The means and standard errors of the mean (SEM) of the quantity of C. burnetii were determined for the samples taken at day 1 and day 7. The ratios of day 7 to day 1 samples were then calculated to determine fold change. Using the means plus/minus SEM, the upper and lower bounds for fold change were calculated and plotted on the graphs. The 95% confidence intervals for Fig. 1 and Table 1 were calculated using GraphPad QuickCalcs.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the C.D.C.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Karla Marrero-Santos for preparation of antibiotic stock solutions and Halie Miller for review of the manuscript.

Author contributions

C.B.S., C.E. and G.K. designed the study. C.B.S. and C.E. performed the experiments. C.B.S. and G.K. analyzed the data and drafted the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Voth DE, Heinzen RA. Lounging in a lysosome: the intracellular lifestyle of Coxiella burnetii. Cellular microbiology. 2007;9:829–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuiston JH, Childs JE. Q fever in humans and animals in the United States. Vector Borne & Zoonotic Diseases. 2002;2:179–191. doi: 10.1089/15303660260613747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tigertt WD, Benenson AS, Gochenour WS. Airborne Q fever. Bacteriological Reviews. 1961;25:285–293. doi: 10.1128/br.25.3.285-293.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCaul TF, Williams JC. Developmental cycle of Coxiella burnetii: structure and morphogenesis of vegetative and sporogenic differentiations. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:1063–1076. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.3.1063-1076.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman SA, Fischer ER, Howe D, Mead DJ, Heinzen RA. Temporal analysis of Coxiella burnetii morphological differentiation. Journal of Bacteriology. 2004;186:7344–7352. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7344-7352.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kersh GJ, et al. Presence and Persistence of Coxiella burnetii in the Environments of Goat Farms Associated with a Q Fever Outbreak. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1697–1703. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03472-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1999;12:518–553. doi: 10.1128/CMR.12.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampschreur LM, et al. Identification of risk factors for chronic Q fever, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:563–570. doi: 10.3201/eid1804.111478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Roeden SE, et al. Chronic Q fever-related complications and mortality: data from a nationwide cohort. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson A, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Q Fever — United States, 2013: Recommendations from CDC and the Q Fever Working Group. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2013;62:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kersh GJ. Antimicrobial therapies for Q fever. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:1207–1214. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.840534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raoult D, et al. Treatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:167–173. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurin M, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P, Raoult D. Phagolysosomal alkalinization and the bactericidal effect of antibiotics: the Coxiella burnetii paradigm. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1992;166:1097–1102. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raoult D, Drancourt M, Vestris G. Bactericidal effect of doxycycline associated with lysosomotropic agents on Coxiella burnetii in P388D1 cells. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1990;34:1512–1514. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.8.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Million M, Thuny F, Richet H, Raoult D. Long-term outcome of Q fever endocarditis: a 26-year personal survey. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2010;10:527–535. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IBM Micromedex, https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/ (2019).

- 17.Omsland A, et al. Isolation from animal tissue and genetic transformation of Coxiella burnetii are facilitated by an improved axenic growth medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3720–3725. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02826-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clay KA, Hartley MG, Russell P, Norville IH. Use of axenic media to determine antibiotic efficacy against coxiella burnetii. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2018;51:806–808. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Omsland A, et al. Host cell-free growth of the Q fever bacterium Coxiella burnetii. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:4430–4434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandoz KM, Sturdevant DE, Hansen B, Heinzen RA. Developmental transitions of Coxiella burnetii grown in axenic media. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;96:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohkuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levison ME, Levison JH. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibacterial agents. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23:791–815, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chopra I., Roberts M. Tetracycline Antibiotics: Mode of Action, Applications, Molecular Biology, and Epidemiology of Bacterial Resistance. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2001;65(2):232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forrest GN, Tamura K. Rifampin combination therapy for nonmycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:14–34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00034-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikaido H, Thanassi DG. Penetration of lipophilic agents with multiple protonation sites into bacterial cells: tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones as examples. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1993;37:1393–1399. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.7.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hackstadt T. Estimation of the cytoplasmic pH of Coxiella burnetii and effect of substrate oxidation on proton motive force. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:591–597. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.2.591-597.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ocampo PS, et al. Antagonism between bacteriostatic and bactericidal antibiotics is prevalent. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2014;58:4573–4582. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02463-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sessa C, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm and Coxiella burnetii infection: report of three cases and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoover TA, Culp DW, Vodkin MH, Williams JC, Thompson HA. Chromosomal DNA deletions explain phenotypic characteristics of two antigenic variants, phase II and RSA 514 (crazy), of the Coxiella burnetii nine mile strain. Infection and immunity. 2002;70:6726–6733. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6726-2733.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kersh GJ, et al. Coxiella burnetii infection of a Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus) found in Washington State. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3428–3431. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00758-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.