Abstract

Differently from the adult multiple sclerosis (MS) population, the predictive value of cognitive impairment in early-onset MS is still unknown. We aim to evaluate whether cognitive performances at disease onset predict disease progression in young people with MS. This is a retrospective study on early onset (<25 years) MS patients, who had a baseline cognitive evaluation at disease onset. Demographic and longitudinal clinical data were collected up to 7 years follow up. Cognitive abilities were assessed at baseline through the Brief Repeatable Battery. Associations between cognitive abilities and clinical outcomes (occurrence of a relapse, and 1-point EDSS progression) were evaluated with stepwise logistic and Cox regression models. We included 51 patients (26 females), with a mean age at MS onset of 17.2 ± 3.9 years, and an EDSS of 2.5 (1.0–6.0). Over the follow-up, twenty-five patients had at least one relapse, and 7 patients had 1-point EDSS progression. Relapse occurrence was associated with lower 10/36 SPART scores (HR = 0.92; p = 0.002) and higher WLG scores (HR = 1.05; p = 0.01). EDSS progression was associated with lower SDMT score (OR: 0.70; p = 0.04). Worse visual memory and attention/information processing were associated with relapses and with increased motor disability after up to 7-years follow-up. Therefor, specific cognitive subdomains might better predict clinical outcomes than the overall cognitive impairment in early-onset MS.

Subject terms: Predictive markers, Cognitive neuroscience

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) usually commences between 18 and 50 years of age, but up to 5% of cases might experience the first symptoms even before being 18 years1. Early-onset MS patients have usually more pronounced inflammatory features (e.g., relapses) and take longer time to convert toward progressive MS phenotype, where disability accumulates independently from relapses2 but, overall, they reach the secondary-progressive MS (SP-MS) stage at a younger age (about 10 years younger than the adult counterpart)2.

MS-related disability arises not only from motor deficits but also from cognitive impairment, which affects approximately 30% of early-onset MS (age at onset <25 years)3–6, with a negative impact on everyday activities6,7. Processing speed and attention, visual-motor function and memory8 and semantic fluency4 are the most commonly affected cognitive domains in early-onset MS.

As cognitive impairment in MS reflects underlying inflammatory and neurodegenerative pathological features of the disorder9 it is highly presumptive its role in predicting the disease course over time. Cognitive impairment at disease onset is an already established biomarker of disease progression over medium and long-term follow-up in adult MS patients10–12. However, the predictive value of cognitive impairment for disease course in early-onset MS patients has never been evaluated. Therefore, the primary aim of this work was to evaluate whether cognitive impairment at disease onset in adolescents and young adults with MS can predict the disease burden, both in terms of relapse and disability accrual, up to seven years after disease onset.

Methods

Study design

This is a multi-centre retrospective study including newly diagnosed early onset relapsing-remitting (RR)-MS subjects (<=25 years), with cognitive assessment at diagnosis, that have been followed-up up to 7 years with al least 2 yearly clinical assessments in order to evaluate both the occurrence of a relapse or a sustained 1-point increase at follow-up.

Subject enrolment

We included consecutive young subjects receiving a new diagnosis of RR-MS from January 2008 to January 2012 within specialized MS Centres at ‘Federico II’ University (Naples, Italy), ‘Luigi Vanvitelli’ University (Naples, Italy), and ‘Aldo Moro’ University (Bari, Italy). Selected centres routinely assess cognition in newly diagnosed MS patient at baseline as part of standard care. Inclusion criteria were: (i) diagnosis of RR-MS according to 2010 McDonald’s criteria13, (ii) age between 12 and 25 years old, (iii) no previous disease modifying treatment (DMT), and (iv) disease duration ≤6 months, (v) assessment via Brief Repeatable Battery (BRB), version A14. Exclusion criteria were i) medical conditions (i.e. clinical depression or psychosis) or treatments that might impact on cognitive performances (i.e. chemotherapy, or corticosteroid treatment from less than 1 month), and ii) visual or motor impairment, compromising neuropsychological performances.

Socio-demographic (age, gender and education) and clinical data (age at onset, disease duration, and EDSS) were collected at disease onset. We classified patients into paediatric (<18 years) and young adulthood onset MS (between 18 and 25 years).

MS subjects were treated with different DMTs, possibly changed or discontinued during the study period as for clinical practice. Follow-up visits were scheduled as for clinical practice (mostly every three months or on the occasion of relapses).

Neuropsychological assessments

Cognitive function was assessed within 6 months from disease onset using BRB, version A14. BRB was administered to all subjects in a standardized manner, in a fixed order, and in a quiet room. The whole battery took about 30 minutes and included the following tests: the Selective Reminding Test-Long Term Storage (SRT-LTS), Selective Reminding Test-Consistent Long Term Retrieval (SRT-CLTR), and Selective Reminding Test-Delayed (SRT-D) to assess verbal memory; the 10/36 Spatial Recall Test (10/36 SPART) and 10/36 Spatial Recall Test-Delayed (10/36 SPART-D) to assess visual memory; the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) to assess information processing speed and executive functions; the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test 2 and 3 (PASAT 2–3) to assess attention, information processing speed, and working memory; the Word List Generation (WLG) to assess semantic fluency.

For MS patients older than 18 years, we adjusted the raw scores obtained at each test for age, gender, and/or education according to the Italian validation study in adults14. For patients younger than 18 years, we adjusted the raw scores obtained at each single test for age, gender, and/or education according to the Italian validation study in paediatric population14. We considered a test as failed when the score was at least 2 standard deviation below the mean normative values15. Cognitive impairment was defined as failure in at least three tests of the BRB at baseline evaluation, as from previous studies15.

Clinical outcomes

During follow-up visits the following outcomes were reported:

Occurrence of clinical relapse: we recorded the number of relapses over the follow-up period, and calculated the Annualized Relapse Rate (ARR) (number of relapses over the follow-up period); the time to first relapse from the baseline assessment was recorded (time to relapse);

6 months confirmed 1-point EDSS progression: we recorded both the occurrence and the time to the 1-point EDSS progression after disease onset (time to 1-point EDSS progression);

Clinical assessments were performed by the same neurologists for the whole follow up in the 3 sites (RL, ES, DP).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (version 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Demographic, clinical and cognitive features of MS patients were presented as means, median or proportions as appropriate. In order to select covariates for statistical analyses, differences for clinical characteristics (baseline EDSS, MS centre, age at onset, disease duration, and DMT - categorized into platform or highly active DMTs) were evaluated in cognitively preserved and impaired patients with unpaired two-tailed Student t-test. We did not test differences for age and gender because normative scores were already corrected for these variables. Covariates included in statistical models were MS centre, follow-up time and first prescribed DMTs.

Backward stepwise logistic regression model (p = 0.20 as the critical value for removing the variables from the model) was used to test associations between corrected scores for each BRB test at disease onset (independent variable) and each of the two clinical variables (e.g., occurrence of relapse and 1-point EDSS progression) (dependent variables). Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated.

Backward stepwise Cox regression models (p = 0.20 as the critical value for removing the variables from the model) were also performed to calculate the Hazard ratios (HR) for both relapse occurrence and 1-point EDSS progression., Relapse occurrence and 1-point EDSS progression were used separately, as dependent variables while corrected scores for each BRB test were included as independent variable. HR and CI were calculated. A sensitivity analysis with 100-repetition bootstrap method was performed and both standard errors and CIs were calculated for both logistic and Cox regression.

Normal distribution of variables and/or residuals was evaluated through statistical and graphical approaches. Results were considered statistically significant for p < 0.05.

Ethical standards

Since clinical and cognitive assessments were part of the clinical practice and results from the present studies did not interfere with medical decision, specific ethics approval was not required as per Italian law (G.U. No. 72 - 26th March 2012). The study was performed in accordance with good clinical practices and the Declaration of Helsinki. DP, LG, VBM and RL had access to patients’ demographic features but had access only to aggregated results after statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline features

We included 51 MS patients (26 females and 25 males). Thirty-three patients (65%) had pediatric onset (<18 years), while 18 patients (35%) had a disease onset between 18 and 25 years old. Demographic and clinical feature of MS patients enrolled in the study are reported in Table 1. Overall follow-up was 5.52 ± 1.75 years, ranging between 2.6 and 8.3 years.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of MS patients.

| Features | ||

|---|---|---|

| Subjects | Total | 51 |

| ‘Federico II’ University, N (%) | 36 (70.6%) | |

| ‘A. Moro’ University, N (%) | 9 (17.6%) | |

| ‘L. Vanvitelli’ University, N (%) | 6 (11.8%) | |

| Sex | Male, N (%) | 25 (49%) |

| Female, N (%) | 26 (51%) | |

| Age at onset, mean ± SD (Range) (years) | 17.2 ± 3.9 (9–25) | |

| Disease duration, mean ± SD (Range) (months) | 3.0 ± 2.9 (0–6) | |

| EDSS, median (Range) | 2.5 (1.0–6.0) | |

| First disease modifying therapy | No DMT, N (%) | 2 (3.9%) |

| IFNβ, N (%) | 31 (60.8%) | |

| Glatiramer acetate, N (%) | 1 (2.0%) | |

| Fingolimod, N (%) | 4 (7.8%) | |

| Natalizumab, N (%) | 8 (15.7%) | |

| Teriflunomide, N (%) | 1 (2.0%) | |

| Dimethyl fumarate, N (%) | 2 (3.9%) | |

| Alemtuzumab, N (%) | 2 (3.9%) | |

| Age at onset, subgroup | Paediatric MS (<18 years), N (%) | 33 (65.0%) |

| Young adult MS (>18 years), N (%) | 18 (35.0%) |

N = Number; SD = standard deviation.

Fourteen patients (27.5%) showed cognitive impairment, according to methods definition. Adjusted scores for each BRB test and the number of MS patients failing the tests are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery adjusted scores in MS patients.

| Test | Scores* | % of Patients failing the test |

|---|---|---|

| SRT-LTS, mean ± SD | 45.62 ± 13.02 | 16% |

| SRT-CLTR, mean ± SD | 35.32 ± 14.31 | 18% |

| SRT-D, mean ± SD | 8.63 ± 2.47 | 14% |

| 10/36 SPART, mean ± SD | 15.78 ± 8.42 | 46% |

| 10/36 SPART-D, mean ± SD | 52.98 ± 3.43 | 30% |

| SDMT, mean ± SD | 52.41 ± 14.65 | 16% |

| PASAT3, mean ± SD | 40.86 ± 12.53 | 16% |

| PASAT2, mean ± SD | 33.39 ± 11.87 | 9% |

| WLG, mean ± SD | 22.58 ± 9.12 | 26% |

*Adjusted for age, gender and education as appropriate.

SD = standard deviation; SRT-LTS = Selective Reminding Test-Long Term Storage; SRT-CLTR = Selective Reminding Test-Consistent Long Term Retrieval; SRT-D = Selective Reminding Test-Delayed; 10/36 SPART = 10/36 Spatial Recall Test; 10/36 SPART-D = 10/36 Spatial Recall Test-Delayed; SDMT = Symbol Digit Modalities Test; PASAT 2–3 = Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test 2 and 3; WLG = Word List Generation.

After MS diagnosis, thirty-three MS patients (64.7%) received a DMT and switched to different DMT after a mean of 39 ± 20 months. Twenty MS patients (61%) switched for clinical or radiological activity, 8 MS patients (21%) switched for adverse events, and 5 patients (15%) switched for personal choice.

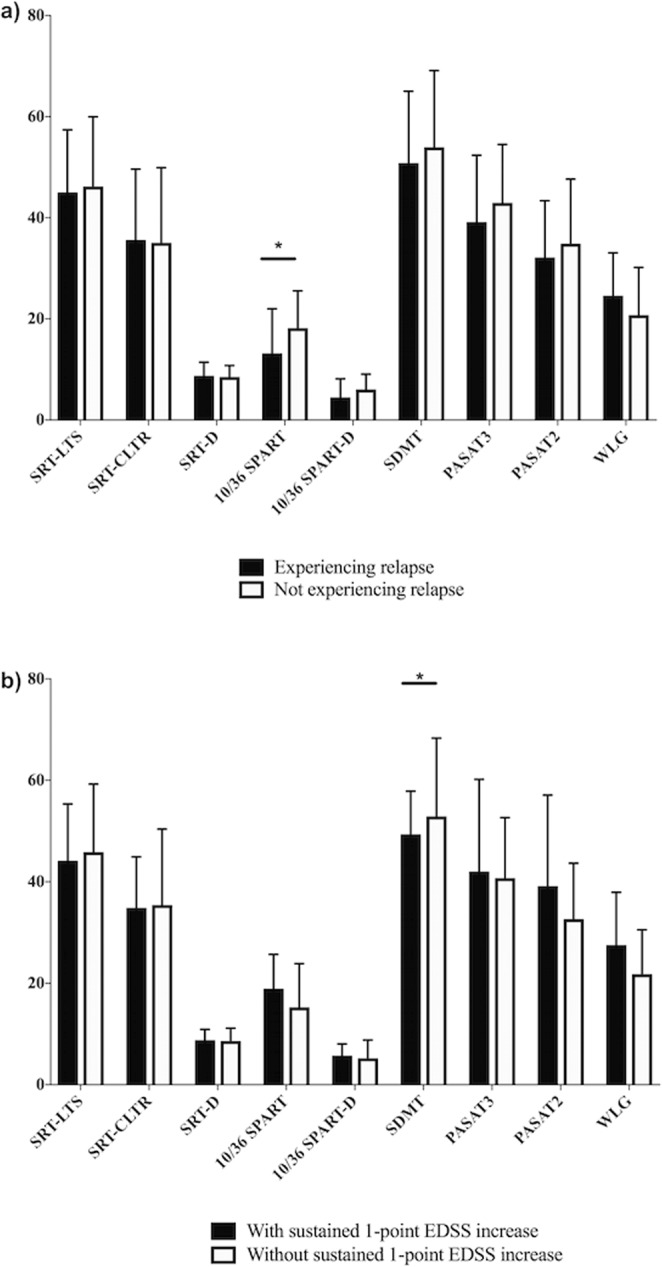

Occurrence of relapse

Twenty-five patients (49%) had at least one relapse (mean time to first relapse was 17 ± 12 months). The annualized relapse rate during follow-up was 0.35 ± 0.34. The occurrence of relapses during follow-up was associated with a lower score at 10/36 SPART (OR: 0.85; 95%CI = 0.75, 0.97, p = 0.01; see Fig. 1a). This finding was confirmed after bootstrap analysis (Bootstrap standard error: 0.05, 95%CI = 0.75, 0.95, p = 0.005).

Figure 1.

Scores on Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery tests and clinical course over the follow-up period. (a) Bar graphs show mean scores for each BRB test (and standard deviation) for MS patients experiencing or not experiencing a relapse over the follow-up. The occurrence of relapse during the follow-up was associated with lower score to the 10/36 SPART (OR: 0.85, *p = 0.01). (b) Bar graphs show mean scores for each BRB test (and standard deviation) for MS patients experiencing or not experiencing 1-point EDSS progression, sustained over 6 months. 1-point EDSS progression was associated with lower score to the SDMT (OR: 0.70, *p = 0.04).

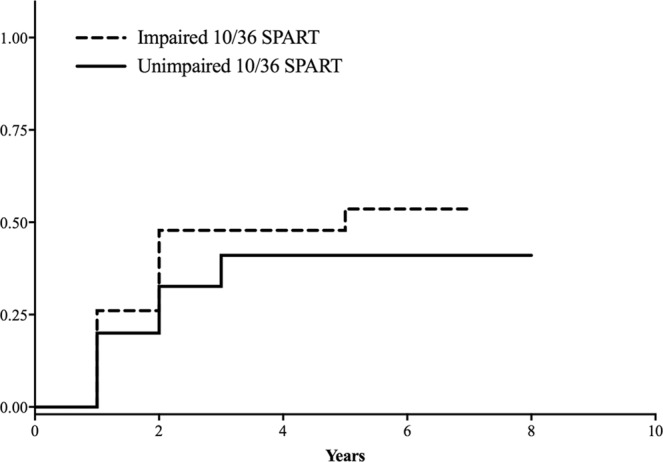

Higher scores at WLG and worse performances on 10/36 SPART (HR = 1.05; 95%CI = 1.01, 1.09, p = 0.01 and HR = 0.92; 95%CI = 0.88, 0.97, p < 0.01, respectively) predicted the relapse risk. However, only the predictive role of 10/36 SPART for relapse occurrence was confirmed by bootstrap analysis (Bootstrap standard error: 0.03, 95%CI = 0.86, 0.99, p = 0.03; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for relapse occurrence and the presence/absence of cognitive deficits in selected Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery tests. Kaplan–Meier curves for the probability of clinical relapse in relation to the presence or absence of cognitive deficit in 10/36 SPART (HR = 0.92; 95%CI = 0.88–0.97, *p = 0.002).

EDSS progression

Seven MS patients (13.7%) had 1-point EDSS progression (after 31 ± 10 months). 1-point EDSS progression was associated with a lower SDMT score (OR: 0.70; 95%CI = 0.49, 0.99, p = 0.04, Fig. 1b), and a trend towards higher 10/36 SPART score (OR: 1.67; 95%CI = 1.01, 2.75, p = 0.05). After bootstrap analysis only lower SDMT scores were associated with a higher risk of disability accrual (Bootstrap standard error: 0.11, 95%CI = 0.51, 0.95, p = 0.02).

Scores on each BRB did not predict the risk of sustained 1-point EDSS progression at Cox analysis.

Discussion

In this retrospective multi-center study including RR-MS subjects with an early onset of disease, we investigated the presence of cognitive predictors of MS disability accrual in the medium term (up to 7 years). We found that worse cognitive function in specific domains at disease onset was associated with the risk of relapses and of sustained disability progression up to 7 years in early-onset MS. Specifically, we reported that worse visual memory and attention/information processing were associated with the occurrence of a new relapses and with increased physical disability, respectively.

The main novelty of the present study was the analysis of the predictive clinical value of cognitive impairment at disease onset in young MS patients. Clinical features suggestive of more aggressive disease course are important in driving appropriate therapeutic strategies. In adult MS patients, processing speed, verbal and spatial memory predicted motor disability over a medium-to-long-term follow-up (about 10 years)10,11. We partly reproduced similar results for early-onset MS. On the one hand, we observed that the performance on attention and processing speed, assessed with the SDMT, predicted the accumulation of motor disability over a medium-term follow-up, confirming previous cross sectional studies16,17. Moreover, information processing speed is associated with deep gray matter atrophy, especially in the thalamus, and with disconnection between subcortical and cortical networks involved in complex cognitive tasks16. Consistently, progressive MS patients, who show more pronounced neurodegenerative processes (e.g., brain atrophy)18, performed worse than RR-MS on SDMT. Noteworthy, this difference was no longer observed after controlling for the disability level19, suggesting that chronic neurodegenerative changes are the main driver of impaired information processing speed. Therefore, considering that early-onset MS patients have reduced grey matter volume over two years from onset20, which is in turn related both to SDMT and EDSS, it is not surprising that performance on SDMT at disease onset might predict the burden of motor disability over time in early-onset MS.

On the other hand, we observed that the occurrence of a new relapse over the follow-up was predicted by a lower performance in the visual memory task. This finding was not completely unexpected since visual memory deficit was already associated to the higher risk of relapsing over the follow-up in adult MS patients10. 10/36 SPART test requires patients to retain the pattern of randomly placed checkers on a checkerboard and further elaborate on this memory by coordinating multiple tasks, adopting advantageous retrieval strategies (e.g., focusing on one single stimulus, avoiding the intrusion of disrupting outer stimuli and manipulating information from long-term memory). Lower 10/36 SPART scores were previously observed in secondary progressive MS patients compared with primary progressive MS with similar disability levels, suggesting that visual memory performance is associated with inflammation more than neurodegeneration21. Supporting this hypothesis, a previous study reported an association between higher blood level of pro-inflammatory cytokines and lower scores on verbal and visual memory functions19. We might speculate that patients with a higher inflammatory pathology and, hence, higher probability of experiencing relapse over the follow-up, perform worse on visual memory tests at baseline.

We reported a prevalence of 27.5% of cognitive impairment in early-onset MS adopting the normative value for pediatric MS15 in MS patients aged less than 18 years old and adult normative value for patients aged between 18 and 25 years old. Prevalence for cognitive impairment in early-onset MS patients is generally consistent ranging from 29 to 37%, although there are variations in the definition of impairment, comparison groups (i.e., published normative values or matched groups of healthy controls) and neuropsychological battery used4,5,22–24. The lower prevalence we found in our sample might be due to a very short disease duration at cognitive assessment (<6 months). Previous studies usually assessed patients with a mean disease duration ranging from 1.5 to 4 years. Therefore, considering that cognitive abilities decline with disease duration25, our results might be in line with previous finding. However, it is also worthy to mention that previous papers usually referred to a healthy control population to define cognitive impairment, which limits the clinical applicability of cognitive evaluation. To overcome this limitation, Lanzillo and colleagues recently validated normative values of the Italian BRB in a pediatric population15 and, based on this, suggested that cognitive impairment definition would require the coexisting evidence of deficit in at least two tests of the BRB14. With this definition, prevalence of cognitive impairment in early-onset MS was 61%, whereas, with a more strict approach (setting the number of tests that must be failed for a diagnosis of cognitive impairment to three), they reported a 17% prevalence of cognitive impairment. Consequently, we applied for our sample the normative data for the BRB in patients younger than 18 years-old to define the impairment in each of the BRB test considering cognitively impaired patients failing at least three tests. Therefore, our methodology might also have impacted the overall prevalence for cognitive impairment.

Our early-onset MS population mostly failed 10/36 SPART, 10/36 SPART-D (assessing spatial memory), and WLG (assessing semantic fluency). On the contrary, adult MS patients mostly suffer from deficits in attention, information processing, verbal and spatial memory6. As such, early-onset MS patients displayed more severe involvement of semantic fluency, as for previous reports26,27. Semantic fluency relies on vocabulary funds, speed of processing and frontal functions. In healthy controls, performance in semantic fluency tests is known to steeply increase up to 23 years old, when the plateau is reached due to the progressive expansion of vocabulary funds and the improvement in controlled search through these funds7. The high prevalence of WLG deficits in early-onset MS might be associated with a disruption in the normal developmental process of the brain structures underpinning semantic fluency, as a consequence of demyelination/axonal loss. Moreover, early-onset MS patients could have reduced social interactions, which, in turn, results in poorer vocabulary funds.

Our study suffers from several limitations, the main one being small sample size, due to the rarity of pediatric onset MS and the lack of homogeneity of cognitive evolution in different centers, necessary to be included in the study. Moreover we analyzed the data retrospectively, although they were collected in a prospective way, leading to possible selection bias. Moreover, the retrospective nature of the study does not allow to completely rule out that different clinical features at baseline evaluation between groups with or without disease activity over the follow-up, both in terms of clinical relapse or disability worsening, might have affected our analysis. However, the long-term follow-up and appropriate statistical methods were applied to reduce these possible confounding factors. Eventually, we applied the BRB, while a more extensive neuropsychological evaluation, i.e. including phonemic fluency, emotion recognition and theory of mind, could have more clearly defined subdomains of cognitive dysfunction and their clinical correlates.

In conclusion, whilst the role of cognitive impairment in adult MS patients in predicting clinical outcomes is already well-established, we suggest that the impairment in selected cognitive domains might predict relapse risk and disability progression in early-onset MS. Although our results are preliminary and deserve further confirmations, the detection of such impairment might lead clinicians towards more active treatments since the very early stages of the disease, also in early-onset MS, avoiding relapses and irreversible disability accrual.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the cogniped study group including Fabrizia Falco, Anna Maria Barbarulo and Rosa Gemma Viterbo.

Author contributions

C.A., L.R., M.M., B.M.V. and C.T.: Conception and design of the study. Data acquisition: C.A., M.M., C.T., S.E., P.D., S.M., L.G. and R.L. Data analysis: C.A., M.M. and L.R. Manuscript drafting: C.A. and L.R.

Competing interests

Roberta Lanzillo and Vincenzo Brescia Morra received personal compensations for speaking or consultancy from Biogen, Teva, Genzyme, Merck, Novartis, Almirall. Marcello Moccia has received salary from Federico II University of Naples, research grants from the ECTRIMS-MAGMNISM, United Kingdom and Northern Ireland MS Society and Merck, and honoraria form Biogen, Genzyme, and Merck. D. Paolicelli has received honoraria for consultancy and/or speaking from Biogen Idec, Merck-Serono, Sanofi-Genzyme, TEVA, Bayer-Schering, Almirall, Novartis and Roche. Dr. Lus has received personal compensation for activities with Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Teva neuroscience as a consultant and speaker; has received research support from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, and Novartis. Dr. Elisabetta Signoriello has received personal compensation for activities with Biogen Idec, Roche, Merck Serono, Novartis as a consultant; has received support for travelling from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Novartis, Teva, Roche, Genzyme. Carotenuto Antonio, Teresa costabile, Anna Maria Barbarulo, Marta Simone and Rosa Gemma Viterbo have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

A comprehensive list of consortium members appears at the end of the paper

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Roberta Lanzillo, Email: roberta.lanzillo@unina.it.

Cogniped study group:

Laura Rosa, Anna Maria Barbarulo, Fabrizia Falco, Rosa Gemma Viterbo, and Francesca Lauro

References

- 1.Banwell B, Ghezzi A, Bar-Or A, Mikaeloff Y, Tardieu M. Multiple sclerosis in children: clinical diagnosis, therapeutic strategies, and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:887–902. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scalfari A, et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study 10: relapses and long-term disability. Brain. 2010;133:1914–1929. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh EA, et al. Pediatric multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:621–631. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amato MP, et al. Cognitive and psychosocial features of childhood and juvenile MS. Neurology. 2008;70:1891–1897. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312276.23177.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacAllister WS, et al. Cognitive functioning in children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64:1422–1425. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158474.24191.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanzillo R, et al. Quality of life and cognitive functions in early onset multiple sclerosis. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amato MP, et al. Cognitive and psychosocial features in childhood and juvenile MS: two-year follow-up. Neurology. 2010;75:1134–1140. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekmekci O. Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis and Cognition: A Review of Clinical, Neuropsychologic, and Neuroradiologic Features. Behav Neurol. 2017;2017:1463570. doi: 10.1155/2017/1463570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocca MA, et al. Clinical and imaging assessment of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:302–317. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moccia M, et al. Cognitive impairment at diagnosis predicts 10-year multiple sclerosis progression. Mult Scler. 2016;22:659–667. doi: 10.1177/1352458515599075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deloire M, Ruet A, Hamel D, Bonnet M, Brochet B. Early cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis predicts disability outcome several years later. Mult Scler. 2010;16:581–587. doi: 10.1177/1352458510362819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitteri M, Romualdi C, Magliozzi R, Monaco S, Calabrese M. Cognitive impairment predicts disability progression and cortical thinning in MS: An 8-year study. Mult Scler. 2017;23:848–854. doi: 10.1177/1352458516665496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polman CH, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amato MP, et al. The Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery and Stroop Test: normative values with age, education and gender corrections in an Italian population. Mult Scler. 2006;12:787–793. doi: 10.1177/1352458506070933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falco Fabrizia, Moccia Marcello, Chiodi Alessandro, Carotenuto Antonio, D’Amelio Angelo, Rosa Laura, Piscopo Kyrie, Falco Andrea, Costabile Teresa, Lauro Francesca, Brescia Morra Vincenzo, Lanzillo Roberta. Normative values of the Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery in an Italian young adolescent population: the influence of age, gender, and education. Neurological Sciences. 2019;40(4):713–717. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-3712-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preziosa P, et al. Structural MRI correlates of cognitive impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis: A Multicenter Study. Human brain mapping. 2016;37:1627–1644. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nocentini U, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12:77–87. doi: 10.1191/135248506ms1227oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Stefano N, et al. Assessing brain atrophy rates in a large population of untreated multiple sclerosis subtypes. Neurology. 2010;74:1868–1876. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e24136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huijbregts SC, Kalkers NF, de Sonneville LM, de Groot V, Polman CH. Cognitive impairment and decline in different MS subtypes. J Neurol Sci. 2006;245:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartels Frederik, Nobis Katharina, Cooper Graham, Wendel Eva, Cleaveland Robert, Bajer-Kornek Barbara, Blaschek Astrid, Schimmel Mareike, Blankenburg Markus, Baumann Matthias, Karenfort Michael, Finke Carsten, Rostásy Kevin. Childhood multiple sclerosis is associated with reduced brain volumes at first clinical presentation and brain growth failure. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2019;25(7):927–936. doi: 10.1177/1352458519829698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reichenberg A, et al. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:445–452. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Till C, et al. MRI correlates of cognitive impairment in childhood-onset multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:319–332. doi: 10.1037/a0022051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julian L, et al. Cognitive impairment occurs in children and adolescents with multiple sclerosis: results from a United States network. J Child Neurol. 2013;28:102–107. doi: 10.1177/0883073812464816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charvet LE, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of cognitive functioning in pediatric multiple sclerosis: report from the US Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Network. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1502–1510. doi: 10.1177/1352458514527862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacAllister WS, Christodoulou C, Milazzo M, Krupp LB. Longitudinal neuropsychological assessment in pediatric multiple sclerosis. Dev Neuropsychol. 2007;32:625–644. doi: 10.1080/87565640701375872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deloire MS, et al. Cognitive impairment as marker of diffuse brain abnormalities in early relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:519–526. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.045872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amato MP, Zipoli V, Portaccio E. Cognitive changes in multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:1585–1596. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.10.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]