Abstract

Bitter taste receptors play crucial roles in detecting bitter compounds not only in the oral cavity, but also in extraoral tissues where they are involved in a variety of non‒tasting physiological processes. On the other hand, disorders or modifications in the sensitivity or expression of these extraoral receptors can affect physiological functions. Here we evaluated the role of the bitter receptor TAS2R38 in attainment of longevity, since it has been widely associated with individual differences in taste perception, food preferences, diet, nutrition, immune responses and pathophysiological mechanisms. Differences in genotype distribution and haplotype frequency at the TAS2R38 gene between a cohort of centenarian and near-centenarian subjects and two control cohorts were determined. Results show in the centenarian cohort an increased frequency of subjects carrying the homozygous genotype for the functional variant of TAS2R38 (PAV/PAV) and a decreased frequency of those having homozygous genotype for the non-functional form (AVI/AVI), as compared to those determined in the two control cohorts. In conclusion, our data providing evidence of an association between genetic variants of TAS2R38 gene and human longevity, suggest that TAS2R38 bitter receptor can be involved in the molecular physiological mechanisms implied in the biological process of aging.

Subject terms: Ageing, Taste receptors

Introduction

The sense of taste is defined as a sensory system in which taste receptor cells are capable of detecting chemical molecules and provide valuable information about the nature and quality of food, but also about health-related issues1,2. In humans, taste receptors were originally identified and named based on their role in the taste cells of the tongue where they can discriminate five basic qualities: sweet, sour, salt, umami and bitter3. However, recent studies have shown that taste receptors are also expressed in a numerous extra-oral tissues throughout the body, including the airway and gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, liver, kidneys, testes, bladder and brain where they participate in a variety of physiological processes4–10. Although the role of taste receptors in the extra-oral tissues has been partially elucidated, recent studies have shown that they sense chemical molecules by means of transduction mechanisms and chemosensory signalling pathways like those occurring in the taste cells of the tongue5,8. Disorders or modifications in the sensitivity or expression of these extra-oral receptors and signalling pathways can affect physiological functions5.

Specifically, bitter taste receptors (T2Rs) that belong to the G-protein coupled receptors superfamily, detect many bitter chemicals with different chemical structures and plant-based compounds11. Humans possess approximately 25 bitter receptors (TAS2R)12. Traditionally, it has been assumed that they initiate bitter taste perception in the oral cavity which serves as a central warning signal against the ingestion of potential toxins. However, growing evidence indicates that T2Rs are widely expressed throughout the body where they mediate diverse non-tasting functions and that their genetic variants are associated with different human disorders9.

Among T2Rs, TAS2R38 has been widely studied because it mediates the bitter taste of thiourea compounds, such as phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP), which has been reported as an oral marker for individual differences in taste perception, general food preferences and dietary behaviour, with consequent links to body mass composition and other non-tasting physiological mechanisms1,2,9,13–17. Several results show that perception of to the bitter taste PTC/PROP is associated with perception of other taste stimuli13,18–25, food preferences and choices13,26–29. Peculiarly, PROP super-taster individuals, compared to PROP non-tasters, seem to show a greater sensitivity and a lower liking and intake for high-fat/high-energy foods1,20,30, and a reduced intake of vegetables and fruits13,16,17,26,28,31,32. However, other studies did not confirm these associations33–40 suggesting that other factors may contribute to dietary predisposition and eating behaviour2. PROP perception has also been associated to health markers including: body mass index28,41, metabolic changes which impact on body mass composition42,43, antioxidant status44, colonic neoplasm risk45,46, smoking behaviors47, consumption of alcoholic beverages20, predisposition to respiratory infections48 and even neurodegenerative diseases49–53. In addition, TAS2R38 has been shown to detect bacterial quorum-sensing molecules and to regulate nitric oxide-dependent innate immune responses of the human respiratory tract48.

The gene codifying for TAS2R38 receptor is characterized by three non-synonymous coding single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) which result in two common variants of the TAS2R38 protein: the functional form containing proline, alanine and valine (henceforth the associated genotype is named as PAV) and the non-functional variant containing alanine, valine and isoleucine, (with the genotype named as AVI)20,54. TAS2R38 SNPs dictate individual differences in PTC/PROP tasting54–56, food linking patterns1,57 and also in TAS2R38‒mediated pathophysiology9, such as susceptibility, severity, and prognosis of upper respiratory infection, chronic rhinosinusitis and biofilm formation in chronic rhinosinusitis patients48,58–64, development of colorectal cancer45,65, taste disorders66 and neurodegenerative diseases49.

Given the implications of TAS2R38 bitter receptor in taste perception, food preferences, diet and nutrition2 (which can affect human development and subsequently longevity67–70), and those in an efficient immune response48 and disease aetiology9,45,49,66 (which modulate the physiological mechanisms involved in the biological process of aging71,72), it is likely that TAS2R38 and its variants can play an important role in the attainment of longevity.

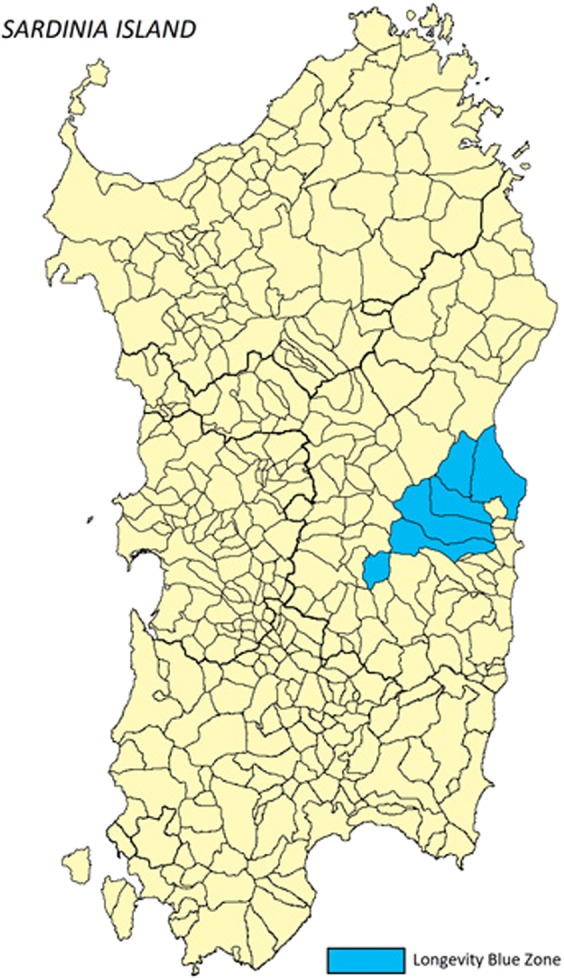

In this study we analysed the genotype distribution and allele frequency of the TAS2R38 gene in a cohort of centenarian subjects recruited in a genetically isolated area of the central-eastern Sardinia island (called the Longevity Blue Zone, LBZ). This area, which includes six mountainous villages of Ogliastra and Barbagia, has a total population of nearly 12,000 inhabitants on a land area of 888 km2 (Fig. 1)73. This population has remained isolated for many centuries, which made its genetic make‒up one of the most homogeneous in Europe74, and its sociocultural and anthropological characteristics well preserved throughout history73,75. LBZ represents an interesting case study because it shows a value of the Extreme Longevity Index (ELI)76 computed for generations born between 1880 and 1900 that is more than twice as high as that of the whole Sardinia. For this reason, data from this population were compared with data from ancestrally‒diverse cohorts recruited in another area of Sardinia (area of Cagliari, in the south of Sardinia).

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the Longevity Blue Zone villages.

The association between longevity and taste genetics has been already investigated77,78. Campa and co-authors77 analysed, in a population from Calabria (Italy), the association with longevity of the common genetic variants of three bitter taste receptor genes that are involved in food preferences, food absorption processing and metabolism. They compared the results from centenarian subjects with those from non-elderly controls with a wide age range (20–84 years). Results showed that the frequency of subjects who carried the genotype homozygote AA for the polymorphism, rs978739, in TAS1R16 gene increases gradually from 35% in subjects aged 20 up to 55% in centenarians. However, another study did not confirm this association, by comparing results from centenarian with those from young controls (age range 18–45 years), in a population from another area of South Italy (Cilento) which could be subjected to different demographic pressures78. Here, we decided to compare results from centenarian subjects of the LBZ with those of two control cohorts south of Sardinia differentiated based on their age, one of young adult subjects (age ranging from 18 to 35 years) and a second of middle-aged adults and older adults (age ranging from 36 to 85 years).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Three hundred seventy-three subjects were included in the study. They were divided in three groups based on their age and area of Sardinia island (Italy) where they were recruited: the Longevity Blue Zone cohort (LBZ) (n = 94) (age ranging from 90 to 105 years) included subjects recruited in the central‒eastern area (Ogliastra/Barbagia) of Sardinia; the Cagliari young cohort (CY) (n = 181) (age ranging from 18 to 35 years) included subjects recruited in the area of the city of Cagliari (Sardinia); the Cagliari cohort including middle-aged adults and elder adults (CMAE) (n = 98) (age ranging from 36 to 85 years) with subjects recruited in the same area of CY cohort. The demographic features of the three cohorts are summarized in Table 1. All subjects were recruited through public advertisements. Specifically, in the case of LBZ cohort, subjects aged 90 years or older were considered eligible participants for this study and were recruited through the Longevity Blue Zone Observatory ‒ a research center which is systematically collecting demographic and individual data of people ≥65 years old from this area75. After excluding residents born outside the LBZ, a blood sample of each eligible subjects was obtained during a home interview. All subjects were informed concerning the procedure and the purpose of the study. All participants provided a signed informed consent form. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 (revised in 1983), and the procedures involving human participants were approved by the ethical committee of the University of Sassari.

Table 1.

Demographic features of the centenarian cohort and two control cohorts.

| Subjects | Age range (y) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | Males (n) | Females (n) | ||

| LBZ | 94 | 42 | 52 | 90–105 |

| CY | 181 | 57 | 124 | 18–35 |

| CMAE | 98 | 43 | 55 | 36–85 |

LBZ, Longevity Blue Zone cohort; CY, Cagliari young subjects’ cohort; CMAE, Cagliari cohort including middle-aged adults and elder adults.

Molecular analyses

DNA was extracted from blood samples by using the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Its concentration was assessed by measurements at an optical density of 260 nm with an Agilent Cary 60 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). All subjects were genotyped for 3 SNPs at base pairs (bp) 145 (C/G), 785 (C/T), and 886 (G/A) of TAS2R38 and for SNP, rs1761667 (G/A), by using TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (C_8876467_10 assay for the rs713598; C_9506827_10 assay for the rs1726866 and C_9506826_10 assay for the rs10246939) according to the manufacturer’s specifications (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies Milano Italia, Europe BV). Replicates and positive and negative controls were included in all reactions.

Statistical analyses

Genotype distribution and haplotype frequencies at the TAS2R38 gene of the three cohorts were compared using Fisher’s method (Genepop software version 4.2; http://genepop.curtin.edu.au/genepop_op3.html)79. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Molecular analysis of the TAS2R38 polymorphisms identified in the LBZ cohort (n = 94) 32 subjects who were PAV homozygous, 38 heterozygous, 17 AVI homozygous and 7 carried rare haplotypes (3 had AAV/AVI genotype, 2 PAV/AAV, 1 AAV/AAV and 1 AAI/AVI), in the CY cohort (n = 181) 41 subjects were PAV homozygous, 85 heterozygous, 48 AVI homozygous and 7 carried rare haplotypes (1 had AAV/AVI genotype, 2 PAV/AAV, 2 PVI/AVI, 1 PAV/AAI and 1 AAI/AVI) and in the CMAE cohort (n = 98) 18 subjects were PAV homozygous, 43 heterozygous, 35 AVI homozygous and 2 carried rare haplotypes (1 had PAV/AAV genotype and 1 AAI/AVI) (Supplementary information).

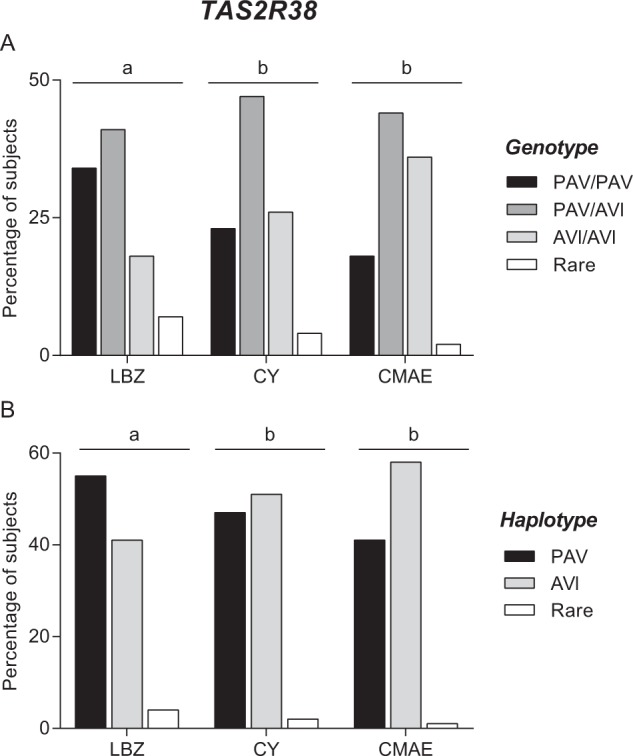

The three cohorts differed statistically based on their genotype distribution (Χ2 = 8.855; P = 0.0119; Fisher’s test) and haplotype frequencies (Χ2 = 11.31; P = 0.0035; Fisher’s test) (Fig. 2). Pairwise comparisons showed that the LBZ cohort differed from the other two cohorts (genotype: Χ2 > 6.381; P ≤ 0.041; Fisher’s test and haplotype: Χ2 > 6.96; P ≤ 0.030; Fisher’s test), which did not differ from each other (genotype: Χ2 = 2.667; P = 0.26; haplotype: Χ2 = 2.862; P = 0.239; Fisher’s test). The LBZ cohort was characterized by a high frequency of the diplotype PAV/PAV (34.04%) and haplotype PAV (55.32%) and a low frequency of diplotype AVI/AVI (18.08%) and haplotype AVI (40.42%), whereas the CY and CMAE cohorts were characterized by a lower frequency of diplotype PAV/PAV (CY: 22.65%; CMAE: 18.36%) and haplotype PAV (CY: 46.96%; CMAE: 40.81%) and a higher frequency of diplotype AVI/AVI (CY: 26.52%; CMAE: 35.71%) and haplotype AVI (CY: 51.10%; CMAE: 58.16%).

Figure 2.

Genotype distribution (A) and haplotype frequencies (B) of polymorphisms of TAS2R38 gene in the Longevity Blue Zone cohort (LBZ) (n = 94), Cagliari young subjects’ cohort (CY) (n = 181) and the Cagliari cohort including middle-aged adults and elder adults (CMAE) (n = 98). Different letters indicated significant difference (Χ2 > 6.38; P ≤ 0.041; Fisher’s test).

Fisher’s test showed no differences of the genotype distribution and haplotype frequencies between males and females in the three cohorts (LBZ: genotype: Χ2 = 1.0798; P = 0.583; haplotype: Χ2 = 1.435; P = 0.488; CY: genotype: Χ2 = 0.822; P = 0.640 haplotype: Χ2 = 0.538; P = 0.764; CMAE: genotype: Χ2 = 1.095; P = 0.578; haplotype: Χ2 = 2.733; P = 0.255) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotype distribution and haplotype frequencies of polymorphisms of TAS2R38 gene in males and females of the centenarian cohort and two control cohorts.

| Males | Females | p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | % | (n) | % | ||

| LBZ | |||||

| Genotype | |||||

| PAV/PAV | 16 | 38.10 | 16 | 30.77 | 0.583 |

| PAV/AVI | 17 | 40.48 | 21 | 40.38 | |

| AVI/AVI | 6 | 14.28 | 11 | 21.16 | |

| rare | 3 | 7.14 | 4 | 7.69 | |

| Haplotype | |||||

| PAV | 50 | 59.52 | 54 | 51.92 | 0.488 |

| AVI | 30 | 35.72 | 46 | 44.23 | |

| rare | 4 | 4.76 | 4 | 3.85 | |

| CY | |||||

| Genotype | |||||

| PAV/PAV | 14 | 24.56 | 27 | 21.77 | 0.640 |

| PAV/AVI | 25 | 43.87 | 60 | 48.39 | |

| AVI/AVI | 17 | 29.82 | 31 | 25 | |

| rare | 1 | 1.75 | 6 | 4.84 | |

| Haplotype | |||||

| PAV | 54 | 47.37 | 116 | 46.77 | 0.764 |

| AVI | 59 | 51.75 | 126 | 50.81 | |

| rare | 1 | 0.878 | 6 | 2.42 | |

| CMAE | |||||

| Genotype | |||||

| PAV/PAV | 5 | 11.63 | 13 | 23.63 | 0.578 |

| PAV/AVI | 19 | 44.19 | 24 | 43.64 | |

| AVI/AVI | 18 | 41.86 | 17 | 30.91 | |

| rare | 1 | 2.32 | 1 | 1.82 | |

| Haplotype | |||||

| PAV | 30 | 34.89 | 50 | 45.46 | 0.255 |

| AVI | 55 | 63.95 | 59 | 53.63 | |

| rare | 1 | 1.16 | 1 | 0.91 | |

ap-value derived from Fisher’s method. LBZ, Longevity Blue Zone cohort, n = 94 (males: n = 42, females: n = 52); CY, Cagliari young subjects’ cohort, n = 181 (males: n = 57, females: n = 124); CMAE, Cagliari cohort including middle-aged adults and elder adults, n = 98 (males: n = 43, females: n = 55).

Discussion

In the present work we studied the role of the bitter receptor, TAS2R38 and its genetic variants on longevity. Our results show that the genetically homogeneous cohort of subjects ranging in age from 90 to 105 years of the an area, which was recognised as one of the world’s longevity hot spots (Longevity Blue Zone)80, differed based on the genotype distribution and haplotype frequencies of TAS2R38 gene from the two genetically heterogeneous cohorts from the South of Sardinia where the longevity level is distinctly lower. Conversely, no differences were found between these two latter cohorts. Specifically, the centenarian cohort showed an increased frequency of subjects carrying the homozygous genotype for the dominant haplotype (PAV/PAV) (34.04%) and haplotype PAV (55.32%) and a reduced frequency of subjects who had the homozygous genotype for the recessive haplotype (AVI/AVI) (18.08%) and haplotype AVI (40.42%). Otherwise, the frequencies determined in the two cohorts from the South of the island, which had a prevalence of subjects carrying the homozygous genotype AVI/AVI (26.52% and 35.71%) and haplotype AVI (51.10% and 58.16%), were similar to those already reported for the Caucasian population in this area25,81–85.

In most populations, females have been reported to live longer than males, with geographical differences in the female/male ratio86. However, the population living in the Sardinian LBZ is an exception among the other long‒lived populations since the female/male ratio in the oldest old is close to 1:180. In addition, several studies have shown that PROP phenotype and genotype variations are associated with gender, with females being more responsive than males14,87. We did not find an effect of gender on the genotype distribution and haplotype frequencies of TAS2R38 locus in the three cohorts studied in this work. By considering specifically the centenarian cohort (which includes a balanced number of males and females), this result allowed us to exclude that the increased frequency of subjects carrying the genotype PAV/PAV and haplotype PAV and the reduced frequency of subjects with the genotype AVI/AVI and haplotype AVI, that we found in this cohort, can to be due to gender bias.

It is well known that an improving diet aimed at increasing intake of fruits and vegetables instead of fat-rich foods may control obesity and reduce the risk of several diseases88,89. A number of studies on human nutrition have suggested that the TAS2R38 variants and the related PROP phenotype may influence dietary behaviour and nutritional status1. The possible association between PROP responsiveness and perception and intake of fats has been extensively studied, but with controversial results1,13,16,17,20,26,28,30,33,34,38–40,90. The widely accepted hypothesis is that PROP non-tasters, compared to PROP super-tasters, show a reduced ability to perceive dietary fat which could lead them to increase the consumption of high-fat foods to compensate the reduced perception57. In agreement with this assumption, the high frequency of the tasting homozygous genotype (PAV/PAV) and the low frequency of the non-tasting one (AVI/AVI), that we found in centenarian subjects, suggest that these individuals may have reached an exceptional longevity because of their genetic predisposition to a low-fat diet. On the other hand, the extreme bitterness intensity of PROP super-tasters has been shown to be the primary reason for avoiding bitter-tasting fruits and vegetables57,91. Since many bitter-tasting compounds in foods (e.g., flavonoids, phenols, glucosinolates) have benefit effects for health92,93, our results in the centenarian cohort seem to be in contrast with the possibility that TAS2R38 genotype is a genetic factor that favour an adequate intake of fruits and vegetables or other bitter foods recommended for a healthy life. However, only a few studies have investigated the relationship between TAS2R38 variants and vegetable intake obtaining controversial results35,38,91,94. Although, the notion that TAS2R38 might serve to govern food intake is interesting, eating behaviour is a complex phenomenon influenced by a broad range of environmental factors, including social cues, socioeconomic status, culture and education, as well as by individual features, such as gender, body weight, ethnicity and health status57. All these factors will be considered in future studies aimed at analysing the role of TAS2R38 variants in the diet of centenarians.

In addition, it is known that TAS2R38 receptor serves other genotype-dependent roles which are relevant for health, with the PAV form associated with an efficient immune response9,48,58,60,64,95–97, a favourable body composition1,32,42,98, as well as with physiological processes59,61–63. On the contrary, the AVI group is associated with a higher risk to develop many dysfunctions and diseases45,48,49,58–66. Therefore, it is not surprising that we find in the centenarian cohort an increased frequency of homozygous subjects for the functional variant of TAS2R38 (PAV) and above all a decreased frequency of those having homozygous genotype for the non-functional form (AVI).

In conclusion, our findings providing evidence of an association between genetic variants of TAS2R38 gene and human longevity, highlight the role of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), TAS2R38 in the molecular physiological mechanisms of the bitter perception associated with important factors involved in the biological process of aging, and suggest that individuals who have a pair of functional alleles (PAV/PAV) at TAS2R38 gene may have a favourable genetic condition for the attainment of exceptional longevity.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the volunteers, without whose contribution this study would not have been possible. In addition, they express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Claudia Porcu and Dr. Pierre Stephanopoulos, from the Sardinia Longevity Blue Zone Observatory, for their precious help in collecting field data. This work was supported by a grant from the University of Cagliari (Fondo Integrativo per la Ricerca, FIR 2017–2018) and by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the University of Cagliari, with the funding of the Regione Autonoma della Sardegna - L.R. n. 7/2007. This work has been realized within the research project supported by P.O.R. SARDEGNA F.S.E. 2014–2020 - Asse III “Istruzione e Formazione, Obiettivo Tematico: 10, Obiettivo Specifico: 10.5, Azione dell’accordo fi Partenariato:10.5.12 “Avviso di chiamata per il finanziamento di Progetti di ricerca – Anno 2017”.

Author contributions

M.M., A.E., R.C., G.M.P. and I.T.B. conceived and designed the study. M.M. and A.E. performed the experiments. M.M. and I.T.B. performed statistical analyses. A.E., R.C. and G.M.P. contributed to the interpretation of the data. M.M. and I.T.B. wrote the first draft of manuscript. A.E., R.C. and G.M.P. revised the paper. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54604-1.

References

- 1.Tepper BJ. Nutritional implications of genetic taste variation: the role of PROP sensitivity and other taste phenotypes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008;28:367–388. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tepper BJ, Banni S, Melis M, Crnjar R, Tomassini Barbarossa I. Genetic sensitivity to the bitter taste of 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) and its association with physiological mechanisms controlling body mass index (BMI) Nutrients. 2014;6:3363–3381. doi: 10.3390/nu6093363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhari N, Roper SD. The cell biology of taste. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:285–296. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behrens, M. & Meyerhof, W. In Sensory and Metabolic Control of Energy Balance. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation Vol. 52 (eds. Beisiegel, U., Meyerhof, W. & Joost, H. G.) 87–99 (Springer, 2011).

- 5.Depoortere I. Taste receptors of the gut: emerging roles in health and disease. Gut. 2014;63:179–190. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark AA, Liggett SB, Munger SD. Extraoral bitter taste receptors as mediators of off-target drug effects. FASEB J. 2012;26:4827–4831. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-215087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laffitte A, Neiers F, Briand L. Functional roles of the sweet taste receptor in oral and extraoral tissues. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2014;17:379–385. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto K, Ishimaru Y. Oral and extra-oral taste perception. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;24:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu P, Zhang CH, Lifshitz LM, ZhuGe R. Extraoral bitter taste receptors in health and disease. J. Gen. Physiol. 2017;149:181–197. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh N, Vrontakis M, Parkinson F, Chelikani P. Functional bitter taste receptors are expressed in brain cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;406:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiener A, Shudler M, Levit A, Niv MY. BitterDB: a database of bitter compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D413–419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi P, Zhang J, Yang H, Zhang YP. Adaptive diversification of bitter taste receptor genes in Mammalian evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:805–814. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Revisiting sugar-fat mixtures: sweetness and creaminess vary with phenotypic markers of oral sensation. Chem. Senses. 2007;32:225–236. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tepper BJ, et al. Factors Influencing the Phenotypic Characterization of the Oral Marker, PROP. Nutrients. 2017;9:1275. doi: 10.3390/nu9121275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tepper BJ, et al. Genetic variation in taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil and its relationship to taste perception and food selection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1170:126–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffy VB, Bartoshuk LM. Food acceptance and genetic variation in taste. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000;100:647–655. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tepper BJ, Nurse RJ. PROP taster status is related to fat perception and preference. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;855:802–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeomans MR, Tepper BJ, Rietzschel J, Prescott J. Human hedonic responses to sweetness: role of taste genetics and anatomy. Physiol. Behav. 2007;91:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescott J, Soo J, Campbell H, Roberts C. Responses of PROP taster groups to variations in sensory qualities within foods and beverages. Physiol. Behav. 2004;82:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duffy VB, et al. Bitter Receptor Gene (TAS2R38), 6-n-Propylthiouracil (PROP) Bitterness and Alcohol Intake. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004;28:1629–1637. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145789.55183.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartoshuk LM. The biological basis of food perception and acceptance. Food Qual. Prefer. 1993;4:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0950-3293(93)90310-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Lucchina LA, Prutkin J, Fast K. PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil) supertasters and the saltiness of NaCl. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;855:793–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melis M, Sollai G, Muroni P, Crnjar R, Barbarossa IT. Associations between orosensory perception of oleic acid, the common single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs1761667 and rs1527483) in the CD36 gene, and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) tasting. Nutrients. 2015;7:2068–2084. doi: 10.3390/nu7032068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melis M, et al. Sensory perception of and salivary protein response to astringency as a function of the 6-n-propylthioural (PROP) bitter-taste phenotype. Physiol. Behav. 2017;173:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melis M, Tomassini Barbarossa I. Taste Perception of Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter, and Umami and Changes Due to l-Arginine Supplementation, as a Function of Genetic Ability to Taste 6-n-Propylthiouracil. Nutrients. 2017;9:541–558. doi: 10.3390/nu9060541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller KL, Steinmann L, Nurse RJ, Tepper BJ. Genetic taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil influences food preference and reported intake in preschool children. Appetite. 2002;38:3–12. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinehart ME, Hayes JE, Bartoshuk LM, Lanier SL, Duffy VB. Bitter taste markers explain variability in vegetable sweetness, bitterness, and intake. Physiol. Behav. 2006;87:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tepper BJ, Neilland M, Ullrich NV, Koelliker Y, Belzer LM. Greater energy intake from a buffet meal in lean, young women is associated with the 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) non-taster phenotype. Appetite. 2011;56:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robino A, et al. A Population-Based Approach to Study the Impact of PROP Perception on Food Liking in Populations along the Silk Road. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Oral sensory phenotype identifies level of sugar and fat required for maximal liking. Physiol. Behav. 2008;95:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drewnowski A, Henderson SA, Hann CS, Berg WA, Ruffin MT. Genetic taste markers and preferences for vegetables and fruit of female breast care patients. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2000;100:191–197. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell KI, Tepper BJ. Short-term vegetable intake by young children classified by 6-n-propylthoiuracil bitter-taste phenotype. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006;84:245–251. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorovic N, et al. Genetic variation in the hTAS2R38 taste receptor and brassica vegetable intake. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 2011;71:274–279. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2011.559553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yackinous CA, Guinard JX. Relation between PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil) taster status, taste anatomy and dietary intake measures for young men and women. Appetite. 2002;38:201–209. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Y, Kennedy OB, Methven L. Exploring the effects of genotypical and phenotypical variations in bitter taste sensitivity on perception, liking and intake of brassica vegetables in the UK. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016;50:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baranowski T, et al. 6-n-propylthiouracil taster status not related to reported cruciferous vegetable intake among ethnically diverse children. Nutr. Res. 2011;31:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keller KL, Tepper BJ. Inherited taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil in diet and body weight in children. Obes. Res. 2004;12:904–912. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timpson NJ, et al. TAS2R38 (phenylthiocarbamide) haplotypes, coronary heart disease traits, and eating behavior in the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;81:1005–1011. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drewnowski A, Henderson SA, Cockroft JE. Genetic Sensitivity to 6-n-Propylthiouracil Has No Influence on Dietary Patterns, Body Mass Indexes, or Plasma Lipid Profiles of Women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007;107:1340–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien SA, Feeney EL, Scannell AG, Markey A, Gibney ER. Bitter taste perception and dietary intake patterns in irish children. J. Nutrigenet. Nutrigenomics. 2013;6:43–58. doi: 10.1159/000348442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tepper BJ, et al. Variation in the bitter-taste receptor gene TAS2R38, and adiposity in a genetically isolated population in Southern Italy. Obesity. 2008;16:2289–2295. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carta G, et al. Participants with Normal Weight or with Obesity Show Different Relationships of 6-n-Propylthiouracil (PROP) Taster Status with BMI and Plasma Endocannabinoids. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1361. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01562-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomassini Barbarossa I, et al. Taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil is associated with endocannabinoid plasma levels in normal-weight individuals. Nutrition. 2013;29:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tepper BJ, Williams TZ, Burgess JR, Antalis CJ, Mattes RD. Genetic variation in bitter taste and plasma markers of anti-oxidant status in college women. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009;60(Suppl 2):35–45. doi: 10.1080/09637480802304499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carrai M, et al. Association between TAS2R38 gene polymorphisms and colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study in two independent populations of Caucasian origin. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basson MD, et al. Association between 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) bitterness and colonic neoplasms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2005;50:483–489. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Risso DS, et al. Genetic Variation in the TAS2R38 Bitter Taste Receptor and Smoking Behaviors. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0164157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee RJ, et al. T2R38 taste receptor polymorphisms underlie susceptibility to upper respiratory infection. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:4145–4159. doi: 10.1172/jci64240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cossu G, et al. 6-n-propylthiouracil taste disruption and TAS2R38 nontasting form in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2018;33:1331–1339. doi: 10.1002/mds.27391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moberg PJ, et al. Phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) perception in Parkinson disease. Cogn. Behav. Neurol. 2007;20:145–148. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e31812570c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moberg PJ, et al. Phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) perception in patients with schizophrenia and first-degree family members: relationship to clinical symptomatology and psychophysical olfactory performance. Schizophr. Res. 2007;90:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moberg PJ, et al. Phenylthiocarbamide perception in patients with schizophrenia and first-degree family members. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:788–790. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brewer WJ, et al. Phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) perception in ultra-high risk for psychosis participants who develop schizophrenia: testing the evidence for an endophenotypic marker. Psychiatry Res. 2012;199:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bufe B, et al. The molecular basis of individual differences in phenylthiocarbamide and propylthiouracil bitterness perception. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim UK, et al. Positional cloning of the human quantitative trait locus underlying taste sensitivity to phenylthiocarbamide. Science. 2003;299:1221–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1080190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Calò C, et al. Polymorphisms in TAS2R38 and the taste bud trophic factor, gustin gene co-operate in modulating PROP taste phenotype. Physiol. Behav. 2011;104:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keller KL, Adise S. Variation in the Ability to Taste Bitter Thiourea Compounds: Implications for Food Acceptance, Dietary Intake, and Obesity Risk in Children. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2016;36:157–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-050916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee RJ, Cohen NA. Role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;15:14–20. doi: 10.1097/aci.0000000000000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adappa ND, et al. The bitter taste receptor T2R38 is an independent risk factor for chronic rhinosinusitis requiring sinus surgery. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:3–7. doi: 10.1002/alr.21253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee RJ, Cohen NA. The emerging role of the bitter taste receptor T2R38 in upper respiratory infection and chronic rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy. 2013;27:283–286. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adappa ND, et al. TAS2R38 genotype predicts surgical outcome in nonpolypoid chronic rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:25–33. doi: 10.1002/alr.21666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adappa ND, et al. Correlation of T2R38 taste phenotype and in vitro biofilm formation from nonpolypoid chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:783–791. doi: 10.1002/alr.21803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adappa ND, et al. T2R38 genotype is correlated with sinonasal quality of life in homozygous DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis patients. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016;6:356–361. doi: 10.1002/alr.21675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Workman AD, Cohen NA. Bitter taste receptors in innate immunity: T2R38 and chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Rhinol.-Otol. 2017;5:12–18. doi: 10.12970/2308-7978.2017.05.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi JH, et al. Genetic Variation in the TAS2R38 Bitter Taste Receptor and Gastric Cancer Risk in Koreans. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26904. doi: 10.1038/srep26904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Melis Melania, Grzeschuchna Lisa, Sollai Giorgia, Hummel Thomas, Tomassini Barbarossa Iole. Taste disorders are partly genetically determined: Role of the TAS2R38 gene, a pilot study. The Laryngoscope. 2019;129(9):E307–E312. doi: 10.1002/lary.27828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fontana L. The scientific basis of caloric restriction leading to longer life. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2009;25:144–150. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32831ef1ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barker DJP, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in england and wales. The Lancet. 1986;327:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Féart C, Samieri C, Barberger-Gateau P. Mediterranean diet and cognitive function in older adults. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2010;13:14–18. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283331fe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hausman DB, Fischer JG, Johnson MA. Nutrition in centenarians. Maturitas. 2011;68:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Accardi G, Caruso C. Immune-inflammatory responses in the elderly: an update. Immun. Ageing. 2018;15:11. doi: 10.1186/s12979-018-0117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Caruso C, Pandey JP, Puca AA. Genetics of exceptional longevity: possible role of GM allotypes. Immun. Ageing. 2018;15:25. doi: 10.1186/s12979-018-0133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pes GM, Errigo A, Tedde P, Dore MP. Sociodemographic, clinical and functional profile of nonagenarians from two areas of Sardinia characterised by distinct longevity levels. Rejuvenation Res. 2019;0:null. doi: 10.1089/rej.2018.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P. & Piazza, A. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Abridged paperback edn, (Princeton University Press, 1996).

- 75.Pes GM, et al. Male longevity in Sardinia, a review of historical sources supporting a causal link with dietary factors. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;69:411–418. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Poulain M, et al. Identification of a geographic area characterized by extreme longevity in the Sardinia island: the AKEA study. Exp. Gerontol. 2004;39:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Campa D, et al. Bitter taste receptor polymorphisms and human aging. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Malovini A, et al. Taste receptors, innate immunity and longevity: the case of TAS2R16 gene. Immun. Ageing. 2019;16:5. doi: 10.1186/s12979-019-0146-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rousset F. GENEPOP’007: A complete re-implementation of the GENEPOP software for Windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008;8:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Poulain M, Pes G, Salaris L. A Population Where Men Live As Long As Women: Villagrande Strisaili, Sardinia. J. Aging Res. 2011;2011:10. doi: 10.4061/2011/153756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tomassini Barbarossa I, et al. Variant in a common odorant-binding protein gene is associated with bitter sensitivity in people. Behav. Brain Res. 2017;329:200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sollai G, et al. First objective evaluation of taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP), a paradigm gustatory stimulus in humans. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40353. doi: 10.1038/srep40353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pani D, et al. An automated system for the objective evaluation of human gustatory sensitivity using tongue biopotential recordings. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Melis M, et al. Dose-Dependent Effects of L-Arginine on PROP Bitterness Intensity and Latency and Characteristics of the Chemical Interaction between PROP and L-Arginine. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Melis M, Mastinu M, Arca M, Crnjar R, Tomassini Barbarossa I. Effect of chemical interaction between oleic acid and L-Arginine on oral perception, as a function of polymorphisms of CD36 and OBPIIa and genetic ability to taste 6-n-propylthiouracil. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Franceschi C, et al. Do men and women follow different trajectories to reach extreme longevity? Italian Multicenter Study on Centenarians (IMUSCE) Aging (Milano) 2000;12:77–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03339894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bartoshuk LM, Duffy VB, Miller IJ. PTC/PROP tasting: anatomy, psychophysics, and sex effects. Physiol. Behav. 1994;56:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90361-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rolls ET. Understanding the mechanisms of food intake and obesity. Obes. Rev. 2007;8(Suppl 1):67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nasser J. Taste, food intake and obesity. Obes. Rev. 2001;2:213–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2001.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tepper BJ, Nurse RJ. Fat perception is related to PROP taster status. Physiol. Behav. 1997;61:949–954. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(96)00608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duffy VB, et al. Vegetable intake in college-aged adults is explained by oral sensory phenotypes and TAS2R38 genotype. Chemosens. Percept. 2010;3:137–148. doi: 10.1007/s12078-010-9079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jahangir M, Kim HK, Choi YH, Verpoorte R. Health-Affecting Compounds in Brassicaceae. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. F. 2009;8:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2008.00065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Verkerk R, et al. Glucosinolates in Brassica vegetables: the influence of the food supply chain on intake, bioavailability and human health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009;53(Suppl 2):S219. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200800065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sacerdote C, et al. Lactase persistence and bitter taste response: instrumental variables and mendelian randomization in epidemiologic studies of dietary factors and cancer risk. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007;166:576–581. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wendell S, et al. Taste genes associated with dental caries. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89:1198–1202. doi: 10.1177/0022034510381502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gil S, et al. Genotype-specific regulation of oral innate immunity by T2R38 taste receptor. Mol. Immunol. 2015;68:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Latorre R, et al. Expression of the Bitter Taste Receptor, T2R38, in Enteroendocrine Cells of the Colonic Mucosa of Overweight/Obese vs. Lean Subjects. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Garcia-Bailo B, Toguri C, Eny KM, El-Sohemy A. Genetic variation in taste and its influence on food selection. Omics. 2009;13:69–80. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.