Abstract

Background

Paneth cells are professional secretory cells found within the small intestinal crypt epithelium. Although their role as part of the innate immune complex providing antimicrobial secretory products is well-known, the mechanisms that control secretory capacity are not well-understood. MIST1 is a scaling factor that is thought to control secretory capacity of exocrine cells.

Methods

Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice were used to evaluate the function of MIST1 in small intestinal Paneth cells. We used histologic and immunofluorescence staining to evaluate small intestinal tissue for proliferation and lineage allocation. Total RNA was isolated to evaluate gene expression. Enteroid culture was used to evaluate the impact of the absence of MIST1 expression on intestinal stem cell function.

Results

Absence of MIST1 resulted in increased numbers of Paneth cells exhibiting an intermediate cell phenotype but otherwise did not alter overall epithelial cell lineage allocation. Muc2 and lysozyme staining confirmed the presence of intermediate cells at the crypt base of Mist1–/– mice. These changes were not associated with changes in mRNA expression of transcription factors associated with lineage allocation, and they were not abrogated by inhibition of Notch signaling. However, the absence of MIST1 expression was associated with alterations in Paneth cell morphology including decreased granule size and distended rough endoplasmic reticulum. Absence of MIST1 was associated with increased budding of enteroid cultures; however, there was no evidence of increased intestinal stem cell numbers in vivo.

Conclusions

MIST1 plays an important role in organization of the Paneth cell secretory apparatus and managing endoplasmic reticulum stress. This role occurs downstream of Paneth cell lineage allocation.

Keywords: MIST1, Paneth Cells, Intermediate Cells

Abbreviations used in this paper: CldU, 5-chloro-2′-deoxyuridine; DBZ, dibenzazepine; IdU, 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine; ISC, intestinal stem cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PTAB, phloxine/tartrizine-alcian blue; RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum; RT, room temperature; TEM, transmission electron microscopy

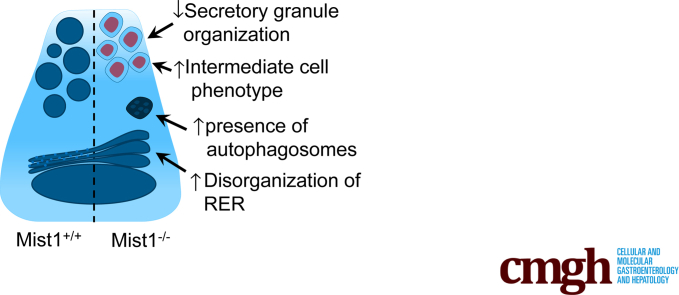

Graphical abstract

See editorial on page 643.

Summary.

Mist1 plays an important role in organization of the Paneth cell secretory apparatus and managing endoplasmic reticulum stress. This role occurs downstream of Paneth cell lineage allocation and is important for Paneth cell maturation.

Paneth cells, professional secretory cells found within the small intestinal crypt epithelium, are seen as part of the innate immune complex providing antimicrobial secretory products including cryptdins (α-defensins), lysozyme, secretory phospholipase A2, and matrilysin (MMP-7), which influence the enteric microbiome.1, 2 More recently, Paneth cells have been shown to contribute to the intestinal stem cell (ISC) niche.3 At the crypt base, Paneth cells are adjacent to and intercalated among ISCs and are therefore in an advantageous position to influence the stem cell microenvironment.4, 5 In addition to secreting numerous antimicrobial factors, Paneth cells synthesize and secrete factors including epidermal growth factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, R-spondin, Wnt3a, tumor growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, which are capable of influencing proliferation and migration of intestinal epithelial cells.3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Furthermore, we now know that Paneth cells can influence active ISC metabolism.

We recently demonstrated in mice treated with doxorubicin that Paneth cells expand in both granule number and size, and that this is coincident with ISC expansion and epithelial repair. Expansion of the Paneth cell population was also associated with an increase in intermediate cell number.11 Intermediate cells are Paneth-like cells that are rarely seen in normal adult intestinal epithelium but have been reported in cases of intestinal infection, inflammation, chemotherapy-induced damage, and inhibition of Notch signaling.12, 13, 14 Although the function of these particular cells is not well-understood, their presence during pathogenic insult suggests that they may play a role in modulating luminal microbiota to prevent further epithelial damage. Alternatively, these cells may reflect a secretory cell progenitor or “transitional cell” present at times of pathologic condition or acceleration of lineage allocation during epithelial repair. Although we know that pathologic insults stimulate the appearance of these cells, the cellular signaling events that encourage the genesis of intermediate cells are not well-understood.

Paneth cells are derived from ATOH1-positive secretory progenitors, and their allocation to this lineage depends on a cadre of transcription factors including SPEDEF, SOX9, and GFI1. Although we have some understanding of the factors necessary for Paneth cell allocation, the factors necessary for Paneth cell maturation (eg, extensive rough endoplasmic reticulum [RER], vesicle formation and trafficking) are not as well-understood. MIST1, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor found primarily in exocrine secretory cells such as pancreatic acinar cells, zymogenic cells of the stomach, and Paneth cells, regulates downstream genes that control secretory vesicle maintenance and trafficking.15 Recently, MIST1 has been described as a scaling factor that can be used by specialized secretory cells to regulate secretory capacity.16 Loss of MIST1 expression in murine gastric epithelium results in decreased granule size, abundance, and electron density and intermediate cell–like features.17 Together, these data point to potential roles for MIST1 in modulating Paneth cell secretory capacity.

In the current study we hypothesized that MIST1 would play a role in modulating the secretory apparatus in Paneth cells. We show that absence of MIST1 expression in Paneth cells does indeed disrupt components of the secretory pathway. In addition, we demonstrate that absence of MIST1 expression confers an intermediate cell phenotype on Paneth cells. We conclude that MIST1 is necessary for Paneth cell maturation, and that the intermediate cell is consistent with an immature Paneth cell phenotype.

Results

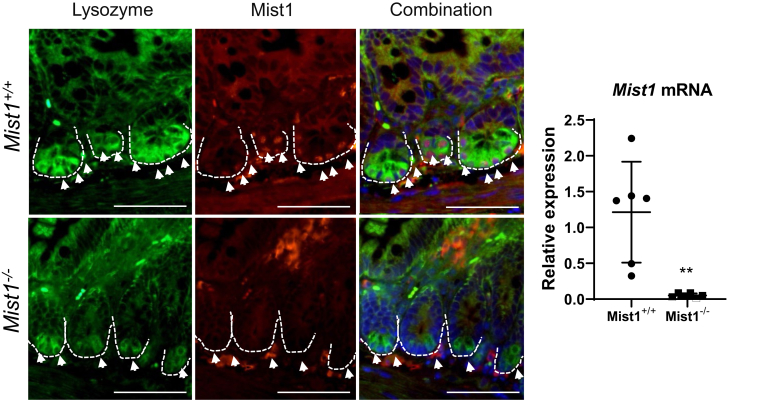

MIST1 protein expression is restricted to Paneth cells at the base of intestinal crypts, as demonstrated by co-localization of MIST1 and lysozyme protein expression, and is contained within the nucleus, which is consistent with it being a transcription factor (Figure 1A). Mist1–/– shows no MIST1 protein expression within Paneth cells, and gene expression analysis confirms minimal Mist1 mRNA expression in knockout mice compared with wild-type (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

MIST1 protein is expressed in Paneth cells within the intestinal epithelium. (Left) Immunofluorescence staining of lysozyme (green), MIST1 (red), and DNA (DAPI) in wild-type (Mist1+/+) and Mist1 knockout (Mist1–/–) mice. Scale bar equals 100 μm. (Right) Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction to show relative expression of Mist1 mRNA in wild-type and Mist1–/– mice. n = 6 mice per group. **P <.01.

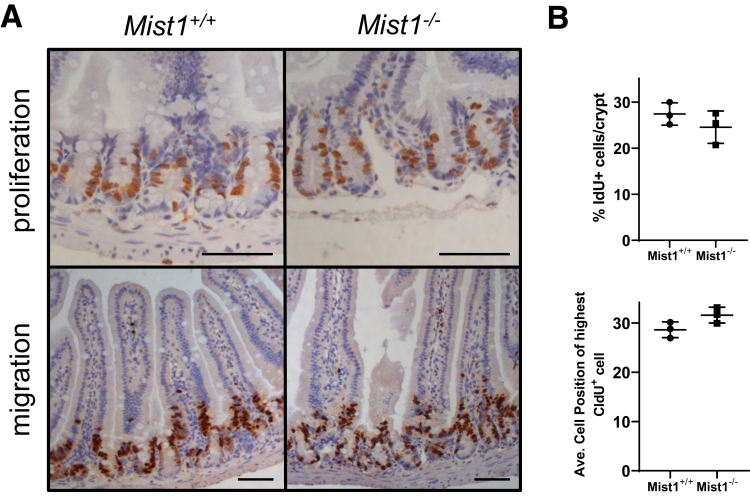

Studies in pancreas have demonstrated that loss of MIST1 from exocrine cells significantly increases the number of proliferative epithelial cells.18 To determine whether loss of MIST1 from Paneth cells had a similar impact in small intestinal epithelium, we marked proliferating cells with a 90-minute pulse of the thymidine analogue, 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IdU). The absence of MIST1 in Mist1–/– intestinal epithelial cells did not alter the percentage of IdU+ crypt epithelial cells compared with Mist1+/+ mice (Figure 2A and B). In addition, to measure cellular migration we performed a 24-hour pulse with the thymidine analogue, 5-chloro-2′-deoxyuridine (CldU). No difference in cellular migration of intestinal crypt epithelial cells between Mist1–/– and Mist1+/+ mice was observed (Figure 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Loss of MIST1 expression does not affect epithelial proliferation or migration. (A) Top panel: IdU was given 90 minutes before death to monitor proliferation by labeling cells in S phase. Scale bar equals 100 μm. Bottom panel: CldU was given 24 hours before death to evaluate migration of cells. Scale bar equals 100 μm. (B) Quantification of percentage of IdU+ cells per crypt. n = 3 mice per group. (C) Quantification of average cell position of highest CldU+ cells along the crypt/villus axis. n = 3 mice per group.

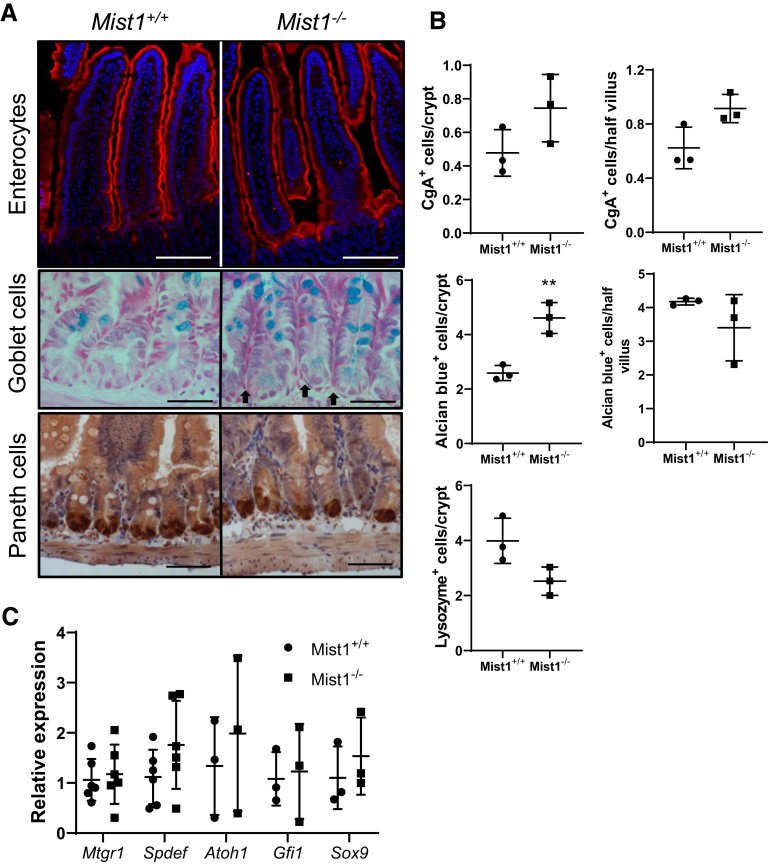

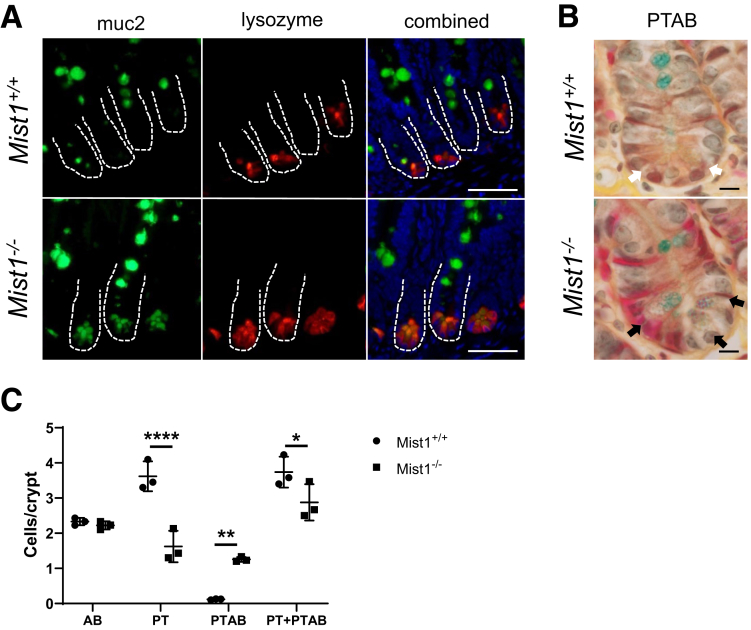

We were interested in determining whether lineage allocation in the small intestine is altered in Mist1KO mice at homeostasis. Markers for secretory lineages, including goblet, enteroendocrine, and Paneth cells, were examined and quantified by alcian blue histology and lysozyme immunohistochemistry. In addition, absorptive cells were stained by using sucrase-isomaltase. As seen in Figure 3A, sucrase-isomaltase staining of villus enterocytes from Mist1–/– mouse jejunum is similar to that found in wild-type mice. Similarly, we were unable to detect any differences in the number of chromogranin A+ cells per crypt or the number of chromogranin A+ cells per half villus (images not shown). Lysozyme staining of Mist1–/– jejunal tissue revealed positively staining cells located at the crypt base with no indication of ectopic cells along the crypt sides. Overall, there was no difference in the number of lysozyme+ cells per crypt between wild-type and Mist1–/– mice. Staining with alcian blue, which binds to mucopolysaccharides such as those found in goblet cells, did not demonstrate a difference in the number of positive cells per half villus. However, within the crypt epithelium, there was a significant increase in the total number of alcian blue+ cells per crypt in Mist1–/– mice (Figure 3A, black arrows). This expansion appears to be due to increased numbers of alcian blue+ Paneth cells at the crypt base. Evaluation of mRNA expression of transcription factors associated with lineage allocation, such as spdef, sox9, and gfi3, revealed no differences between wild-type and Mist1–/– mice (Figure 3C). These data suggest that the functions of MIST1 are more specific to optimizing the secretory performance of Paneth cells and not in the allocation of secretory progenitors to the Paneth cell lineage. We recently demonstrated in mice treated with doxorubicin that MIST1 protein was localized to Paneth cell nuclei in the crypt base but was absent in lysozyme-positive cells along the crypt sides. These cells tended to be muc2+/lysozyme+ intermediate cells.11 This led us to investigate whether absence of MIST1 expression was associated with the appearance of intermediate cells in crypt epithelium. As seen in Figure 4A, co-staining of jejunal sections for Muc2 and lysozyme demonstrated that lack of MIST1 expression resulted in co-expression of Muc2 and lysozyme in granulated cells at the crypt base. We next used phloxine/tartrizine-alcian blue (PTAB) staining to jejunal tissues to delineate between goblet [alcian blue+ only (PT–AB+)], Paneth [phloxine/tartrizine+ only (PT+AB–)], and intermediate cells [both phloxine/tartrizine+ and alcian blue+ (PT+AB+)] cells. Similar to Muc2/lysozyme immunofluorescence, PTAB staining revealed cells that appeared to have a PT+AB+ (intermediate cell) phenotype (Figure 4B). Quantification of PTAB staining (Figure 4C) revealed a significant decrease in PT+AB– (Paneth phenotype) cells and a significant increase in PT+AB+ (intermediate phenotype) cells in Mist1–/– mice compared with wild-type mice. In contrast, no differences were observed in the PT–AB+ (goblet phenotype) cells between Mist1–/– and wild-type mice. This demonstrates that the increased alcian blue staining in the crypt base of Mist1–/– mice observed in Figure 3B is directly due to increased numbers of intermediate cells. This finding was corroborated by our Muc2/lysozyme staining showing the presence of Muc2+/lysozyme– cells along the crypt sides in both Mist1 null and wild-type mice. These data suggest that a lack of MIST1 expression is necessary for the intermediate cell phenotype, whereas normal mature Paneth cells express MIST1. In addition, intermediate cells derive from cells that have been allocated to the Paneth cell lineage.

Figure 3.

Loss of Mist1–/–in small intestine does not alter secretory allocation. (A) Staining for sucrase-isomaltase (enterocytes), alcian blue (goblet cells), and lysozyme (Paneth cells). Scale bars equal 100 μm, 50 μm, and 50 μm, respectively. Black arrows point out alcian blue+ Paneth cells. (B) Quantification of chromogranin (Cg) A+ cells in crypt and villus compartments. n = 3 mice per group. Quantification of alcian blue+ cells in crypt and villus compartments. n = 3 mice per group. **P <.01. Quantification of lysozyme+ cells per crypt. n = 3 mice per group. (C) mRNA expression of transcription factors associated with secretory cell lineage allocation in isolated jejunal crypts from Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice. n = 3–6 mice per group.

Figure 4.

Mist1 expression prevents Paneth cells from becoming intermediate cells. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of jejunal tissue from Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice for muc2 (green) and lysozyme (red). Dual positive cells (yellow) are intermediate cells. Scale bar equals 50 μm. (B) Representative PTAB staining of jejunal tissue from Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice. Phloxine tartrizine stains protein-dense areas, Paneth cell–like granules brown, and alcian blue stains mucins blue. Paneth cell granules from Mist1+/+ Paneth cells stain brown (white arrows), and granules from Mist1–/– Paneth cells, which contain mucins, stain purple, suggesting an intermediate cell phenotype (black arrows). Scale bar equals 10 μm. (C) Quantification of PTAB staining of jejunal tissue from Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice from (B) showing alcian blue+ (AB), phloxine/tartrizine+ (PT), dual positive (PTAB), and total stained cells (PT + PTAB) per crypt. n = 3 mice per group. *P <.05. **P <.01. ****P <.0001.

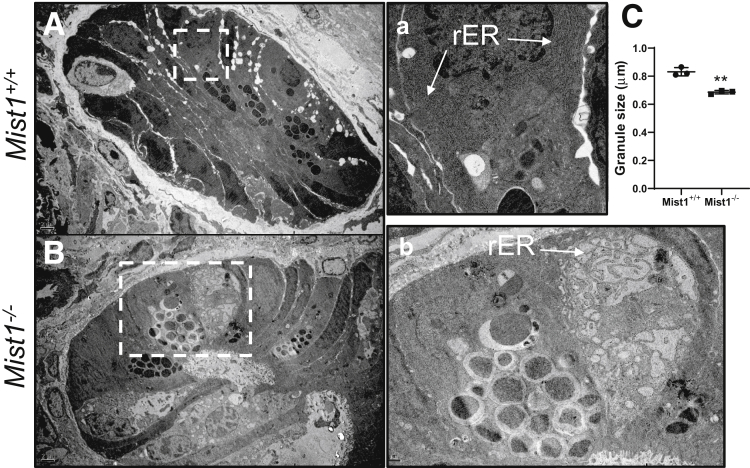

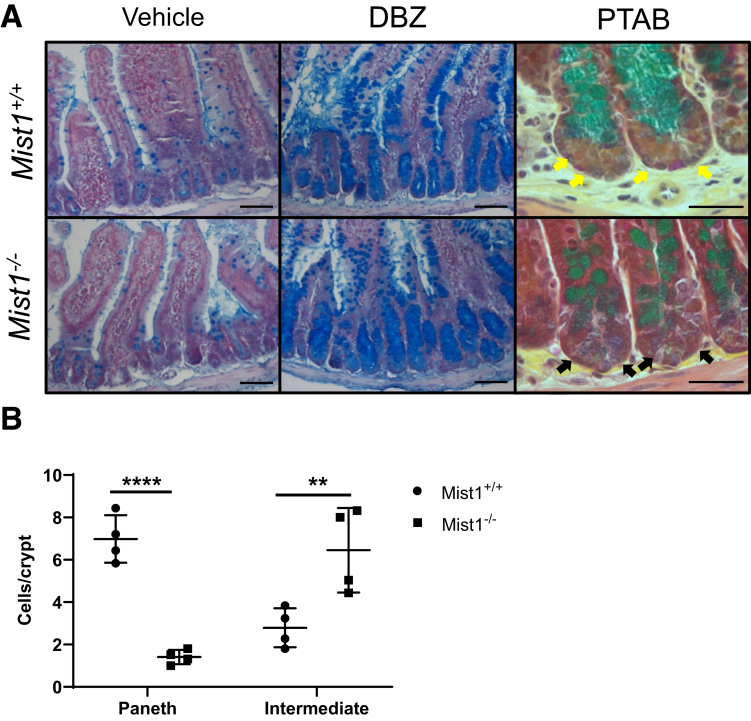

Because Mist1 appears to be associated with the professional secretory identity of Paneth cells, we evaluated the ultrastructure of cellular components crucial for normal secretory capacity via transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Paneth cells from wild-type jejunum contained a well-organized secretory axis consisting of extensive perinuclear RER, supranuclear Golgi apparatus, and electron-dense secretory vesicles (Figure 5A, inset a). Examination of Paneth cells from Mist1–/– jejunum by TEM revealed several histologic differences, including disorganized, distended RER, misplaced Golgi apparatus, and altered secretory granule morphology (Figure 5B and b). This altered morphology was associated with a significant decrease in secretory granule diameter (Figure 5C) in Paneth cells from Mist1–/– mice. Others demonstrated that increased intermediate cell numbers can result from inactivation of Notch signaling by epithelium-specific knockout of ADAM10, an enzyme necessary for Notch activation.19 We wondered whether Notch inactivation was acting through Mist1-regulated pathways. If so, we hypothesized that Mist1–/– and Mist1+/+ mice would exhibit no differences in the numbers of intermediate cells after Notch inactivation, and that the number of intermediate cells would be similar in untreated Mist1–/– mice. To evaluate this we treated Mist1–/– and wild-type mice with the gamma secretase inhibitor dibenzazepine (DBZ), which broadly disrupts Notch signaling. As can be seen in Figure 6A, treatment with DBZ resulted in the characteristic expansion of secretory lineages, particularly alcian blue+ cells, which populate the crypt and villus epithelium. This was observed in both Mist1–/– and wild-type mice and was different from Mist1–/– mice that were not treated with DBZ. Staining of jejunal tissue from DBZ-treated mice with PTAB (Figure 6A and B) confirmed crypts filled with alcian blue–positive goblet cells and revealed that even with inhibition of Notch signaling, a significant decrease in brown staining PT+AB– (Paneth cell phenotype) cells and a significant increase in purple staining PT+AB+ cells (intermediate cell phenotype) in Mist1–/– mice compared with wild-type mice are observed. This suggests that Notch signaling is intact in Mist1–/–, and that MIST1 acts downstream of Notch signaling in Paneth cell–dedicated secretory progenitors.

Figure 5.

MIST1 expression plays a role in Paneth cell granule size and maturation. Transmission electron micrographs of crypts from jejunal tissue of (A) and (a) Mist1+/+ and (B) and (b) Mist1–/– mice showing ultrastructural characteristics of Paneth cells. (C) Quantification of Paneth cell granule size. n = 3 mice per group. **P <.01.

Figure 6.

Intermediate cell phenotype of Mist1–/–mice is not due to impaired Notch signaling. (A) Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice were treated with DBZ to inhibit Notch signaling, and jejunal tissues were stained with alcian blue. Scale bar equals 125 μm. (B) Jejunal tissues from (A) were stained with PTAB to evaluate Paneth cells (yellow arrows) and intermediate cells (black arrows). Paneth cell granules from Mist1+/+ Paneth cells stain brown, and granules from Mist1–/– Paneth cells that contain mucins stain purple, suggesting an intermediate cell phenotype. Scale bar equals 50 μm. (C) Quantification of Paneth cell and intermediate cell numbers. n = 4 mice per group. ****P <.0001. **P <.01.

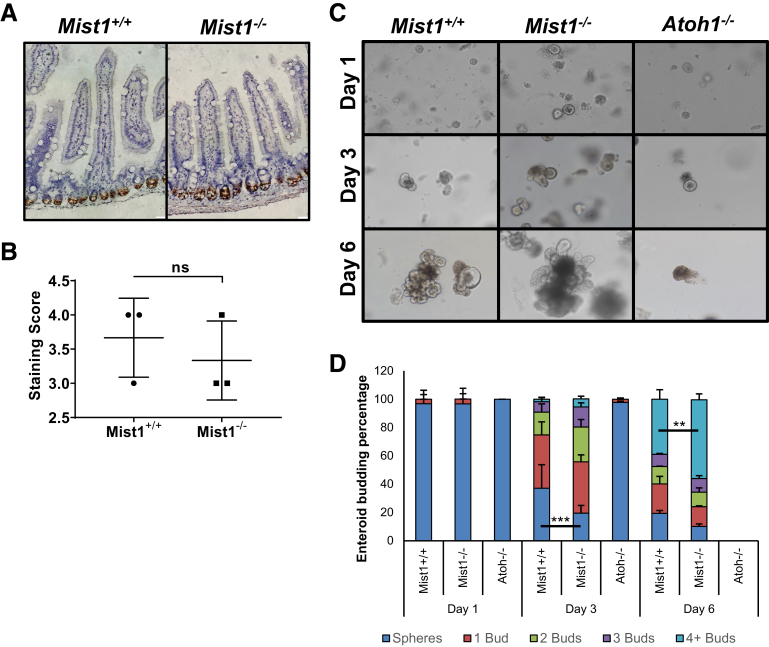

Because Paneth cells make up a significant component of the ISC niche, we next evaluated whether the presence of immature Paneth cells in small intestinal crypts of Mist1–/– mice affected the number and function of ISCs. First, we evaluated active ISC number by quantification of Olfm4+ staining after in situ hybridization of jejunal tissue in Mist1–/– and Mist1+/+ mice. As can be seen in in Figure 7A, Olfm4 in situ hybridization staining appeared visually similar in Mist1–/– and Mist1+/+ mice. Scoring of the staining by using a standardized scoring system (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA) confirmed no difference in active ISC number between Mist1–/– and Mist1+/+ mice (Figure 7B). Others have demonstrated that enteroids can grow in culture in the absence of exogenous Wnt as long as Paneth cells are present.20 Therefore, we used enteroid culture without added Wnt3 to determine whether the immature Paneth cells from Mist1–/– mice were able to sustain enteroid formation and budding. As seen in Figure 7C, crypts from Mist1–/– and Mist1+/+ mice were able to grow and bud in culture. In contrast, crypts from Ato–/– mice, which are devoid of Paneth cells, did not bud in the absence of Wnt3a and did not survive out to day 6 of culture. Quantification of budding revealed that enteroids from Mist1–/– mice accumulated buds at a faster rate than those from wild-type mice (Figure 7D). As early as day 3 of culture we counted significantly fewer spheroids in Mist1–/– cultures compared with Mist1+/+, that is, more enteroids from Mist1–/– cultures were budding. This difference continued to day 6 in culture where the number of enteroids from Mist1–/– crypts with 4 or more buds was significantly greater than enteroids from Mist1+/+ mice.

Figure 7.

Loss of MIST1 expression improves active ISC function in culture. (A) Representative in situ hybridization of Olfm4 in jejunal tissue from Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice. Scale bar equals 20 μm. (B) Quantification of Olfm4 in situ hybridization staining using ACD scoring system. NS, not significant. (C) Micrographs of enteroid cultures derived from jejunal crypts from Mist1+/+, Mist1–/– and Atoh1–/– mice 1, 3, and 6 days after culture. (D) Quantification of budding percentage of Mist1+/+, Mist1–/– and Atoh1–/– enteroids over time. n = 5 Mist1+/+ and Mist1–/– mice were used for 4 independent culture experiments. n = 2 Atoh1–/– mice for 2 independent culture experiments to verify the inability of Atoh–/– crypts to grow in minimal culture medium. For each experiment n = 6 separate wells from each mouse were used for quantifying budding. **P <.01. ***P <.001.

Discussion

MIST1 has been shown to serve as a maturation and scaling factor in exocrine cells from other organs such as pancreas and stomach; however, its function in small intestinal Paneth cells is still unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that lack of MIST1 expression in Paneth cells resulted in an intermediate cell phenotype characterized by smaller, immature secretory granules, disorganized secretory apparatus, and co-expression of both goblet and Paneth cell markers. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the absence of MIST1 did not impact overall secretory lineage allocation and was independent of Notch signaling. Finally, we showed that although loss of MIST1 expression did not alter overall proliferative numbers or active ISC numbers in the small intestinal crypt in vivo, it did increase the budding capacity of enteroids in vitro. MIST1 plays a significant role in maturation of exocrine cells in various organ systems, including the small intestine in this study, and alteration of its expression is associated with changes in cellular proliferation, morphology, and localization.17, 21 For example, ectopic expression of Mist1 in pancreatic cell lines inhibits proliferation by induction of p21CIP1/WAF1.18 Conversely, knockdown of MIST1 in this cell line decreased p21CIP1/WAF1 and increased proliferation.18 Furthermore, absence of MIST1 in pancreatic acini results in mislocalization of secretory granules, and in the cells of the gastric glands, its absence results in decreased granule size and nuclear positioning within the cell.21, 22 Our current studies suggest that unlike what has been shown in the pancreas, the absence of Mist1 in small intestinal Paneth cells does not alter overall proliferation or cellular migration in crypt epithelium. In addition, nuclear location was not altered in Paneth cells of Mist1–/– mice, but we did observe decreased secretory granule size and alterations in RER ultrastructure. Our data suggest that although Paneth cells are similar to other exocrine cells in many ways, MIST1 in the Paneth cell may play less of a role in cellular polarity but is still important for secretory machinery.

Notch signaling plays a significant role in controlling the cell fate decisions of intestinal epithelial progenitor cells into absorptive and secretory lineages. Inhibition of this pathway, by either chemical inhibition of γ-secretase (eg, DBZ) or knockout of associated genes such as Adam10, Dll1, Dll4, or Rbp-j, relegates cells to the secretory phenotype, particularly alcian blue–positive cells.19, 23, 24, 25 Tsai et al19 demonstrated that the loss of ADAM10 in intestinal epithelium also increased the number of intermediate cells. Our observation that loss of MIST1 expression directed Paneth cells to an intermediate cell phenotype led us to question whether Notch signaling was disrupted in those cells. Treatment of wild-type and Mist1–/– mice with DBZ led us to 2 conclusions: (1) that loss of MIST1 does not disrupt Notch signaling and (2) that MIST1 functions downstream of Paneth cell lineage allocation.

Our current understanding of allocation of cells to the Paneth cell lineage in the small intestine includes accumulation of ATOH1 in progenitors that are negative for Notch signaling, along with expression of the transcription factors GFI1, SOX9, and SPDEF.26, 27, 28, 29 Loss of any one of these transcription factors alters or ablates Paneth cell numbers. Although rare in homeostasis, intermediate cells have been described in the small intestinal crypt in response to a number of damaging and pathogenic stimuli, including doxorubicin and helminth infections, with very little clarity of their source.11, 30 Our data suggest that MIST1, working downstream of the above mentioned transcription factors, plays a role in preventing the intermediate cell phenotype, which is an immature Paneth cell phenotype on the basis of our observations. We presume that expression of MIST1 is dependent on one or more of those same transcription factors and subsequently drives the Paneth cell to its fully mature, secretory form. However, associations between MIST1 and Paneth cell–related transcription factors have not been demonstrated in the literature with the exception of overexpression of MIST1 in hepatoblasts leading to decreased expression of SOX9.31 Further studies of the association of MIST1 with other Paneth cell–related transcription factors are warranted to determine whether MIST1 is truly part of the Paneth cell lineage allocation process.

Alternatively, the intermediate cell phenotype we observe in Mist1–/– Paneth cells could be due to an inability of these cells to appropriately handle ER stress. Others have demonstrated that MIST1 expression is downstream of expression of the ER stress–associated transcription factor XBP1 and that MIST1 can inhibit XPB1 expression.32, 33 Targeted deletion of XBP1 in intestinal epithelium results in apoptosis and loss of Paneth cells.34, 35 Presumably this is due to an inappropriate response to ER stress; however, a similar result is observed when ATOH1 (a transcription factor necessary for Paneth cell lineage allocation) is deleted from intestinal epithelium.26 Our TEM data showing disorganized RER and secretory granules suggest a disruption in normal ER response. However, our studies used a transgenic knock-in of LacZ or Cre recombinase (Cre) into the MIST1 allele to create whole animal loss of Mist1 expression. Therefore, it is difficult for us to delineate whether the alterations we see in Paneth cell phenotype are due to a role of MIST1 in lineage allocation or in promoting normal ER stress response. Additional studies using Mist1 floxed mice with an epithelial-specific or Paneth cell–specific, inducible Cre driver would allow the deletion of MIST1 in otherwise mature Paneth cells and provide greater insight into the role of MIST1 in Paneth cell lineage allocation and/or ER stress response. When cultured in minimal culture medium containing no exogenous Wnt, we observed increased budding of crypts from Mist1–/– mice compared with crypts from Mist1+/+ mice, suggesting increased activity of active ISCs in culture and/or increased secretion of trophic factors from Paneth cells. Our in situ hybridization for Olfm4 mRNA expression suggests that the increased budding is not due to an increase in the number of active ISCs in isolated crypts. Because Paneth cells play a substantial role in influencing the ISC niche by secreting trophic factors such as Wnt3a or sPLA2, one possibility is that Mist1–/– Paneth cells have an altered secretome that becomes evident once put into culture.3, 36 Alternatively, as has been demonstrated in the pancreas, loss of MIST1 expression in Paneth cells could impact expression of gap junctional proteins such as connexins 26 and 32, which can serve as tumor suppressors.37, 38 Loss of these junctional proteins is permissive to tumor formation in a variety of organs including breast, colon, lung, and liver. Thus, once placed in a pro-proliferative environment such as culture medium, the Mist1–/– crypts lack normal factors that would suppress excessive proliferation and budding.

The findings of this study demonstrate that Mist1 plays a significant role in maturation of Paneth cells in the small intestine, particularly within the context of their secretory mechanics. Our data also implicate MIST1 in maturation of Paneth cells and preventing an intermediate cell phenotype, warranting further study of the role MIST1 plays in Paneth cell–specific gene expression.

Methods

Animals

Female mice aged 10–16 weeks were used for this study. Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of NC State University. A select cohort of mice were given intraperitoneal injection (1 mg each) of CldU 24 hours and intraperitoneal injection of IdU 90 minutes before killing. In all cases after death, the small intestine was flushed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), and a piece of middle jejunum was fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin as previously reported.11 Mist1nLacZ mice, which are null for Mist1, were used as Mist1–/– and were acquired from the laboratory of Dr Jason Mills (Washington University) with permission from Dr Stephen Konieczny (Purdue University). Atohfl/fl mice were acquired from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and crossed with VilCreERT2 mice obtained from Dr Larry Chen with permission of Dr Sylvie Robine.

Dibenzazepine Treatment

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 30 μmol/kg DBZ once per day for 5 days before death and tissue collection on day 6 as previously described.39 Briefly, 25 mg DBZ was dissolved in 180 μL dimethyl sulfoxide to make a 0.3 mol/L stock solution. For injection, DBZ stock solution was diluted as follows (for 2 mL of injection solution); 400 μL 0.5% Tween-80 was added to 600 μL and gently vortexed. Next, 20 μL of 0.3 mol/L DBZ stock and 1 mL of 1% methylcellulose were added, and the suspension was vigorously passed through an 18-gauge needle to break up precipitated DBZ. Jejunal tissue was rinsed, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with alcian blue or with PTAB.

Histology

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded specimens were oriented to provide cross sections perpendicular to the long axis of the bowel, and 5-μm sections were used for evaluating general morphology. Longitudinal sections of crypts or villi were selected for scoring on the basis that a single, continuous layer of epithelium followed from crypt base to villus base and from the crypt-villus junction to the villus tip, respectively. For all quantitative analyses, 30 crypts or villi per animal (n = 3–6 animals) were randomly selected and scored. Crypts or villi were only scored if they had a single layer of continuous epithelium and were well-oriented. Tissue was stained with H&E, the goblet cell marker alcian blue, or PTAB. PTAB staining allows the differentiation of Paneth cells from intermediate cells by staining protein-dense Paneth cells brown and mucin-rich intermediate cells purple. H&E stained sections from n = 3 mice per time point were used to calculate granule diameter in Paneth cells. Proliferative index was calculated by dividing the number of IdU-positive cells per crypt by the total number of cells per crypt. Migration was calculated by determining the highest cell position starting at the crypt base that exhibited immunohistochemical staining for CldU. A minimum of 60 granules were measured, with an average of 88 granules measured per section. Granules were measured under oil emersion at ×160 magnification by using AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany), which allowed the measurement of granule diameter. PTAB-stained sections were used for scoring of PT+AB– (Paneth cells), PT–AB+ (goblet cells), and PT+AB+ (intermediate cells) cell numbers. Scoring of all parameters was done in a blinded fashion by using Axio Imager software on images captured using an Axio Imager A1 microscope and an AxioCam MRC 5 high resolution camera (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc, Thornwood, NY).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

For immunohistochemistry, slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 minutes at room temperature (RT) to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were treated to heat-induced epitope retrieval by using Thermo Scientific Lab Vision heat-induced epitope retrieval buffer L according to manufacturer’s instructions (cat. #TA-135-HBL; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Next, slides were blocked in 10% normal goat serum in Tris buffer for 1 hour at RT. For slides stained with anti-IdU antibody, blocking was instead performed with the Thermo Fisher Scientific Rodent Block (cat. #TA-060-QRB) for 30 minutes at RT according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primary antibodies were diluted in Thermo Diluent (cat. #TA-125-ADQ; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and applied to each section: CldU (cat. #NB500-169; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO) at 1:200 dilution; lysozyme (cat. #NCL-MURAM; Leica Novocastra, Wetzlar, Germany) at 1:250 dilution; chromogranin A (cat. #ab15160; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) at 1:400 dilution incubated overnight at 4°C; and IdU (cat. #347580; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 1:200 dilution for 2 hours at RT. Sections were then washed and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies for 60 minutes at RT, with the exception of slides stained with anti-IdU antibody, which were incubated with the mouse on mouse horseradish-peroxidase polymer for 15 minutes at RT (cat. #TL-060-QPHM; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After washing, slides were incubated in Vectastain ABC reagent (cat. #PK-7200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes and then developed in a DAB substrate solution. For immunofluorescence, slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and then subjected to antigen retrieval in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) with 0.05% Tween 20 for 30 minutes at 100°C. After blocking in 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 hour at RT, primary antibodies were diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS and applied as follows: Mist1 (1:200, cat. #sc-80984; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) sucrase-isomaltase (1:100, cat. #sc-27603; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); muc2 (1:100, cat. #sc-15334; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); and lysozyme (1:100, cat. #sc-27958; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour at RT. Slides were washed and then incubated with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. After washing, Vectashield with DAPI antifade mounting media was applied, and slides were coverslipped and sealed with clear nail polish.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

TEM was used to verify Paneth cell phenotype. For TEM, jejunal tissue pieces were fixed overnight in fixative (2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.15 mol/L sodium phosphate, pH 7.4), washed in sodium phosphate buffer, post-fixed for 1 hour in potassium ferrocyanide–reduced osmium, and embedded in PolyBed 812 epoxy resin (cat. #08791-500; Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Cross sections (1 μm) were cut, stained with 1% toluidine blue, and examined by light microscopy to isolate the area of interest. Ultrathin sections were cut (70- to 80-nm thickness), mounted on 200 mesh copper grids, and stained with 4% aqueous uranyl acetate for 15 minutes, followed by Reynolds’ lead citrate for 8 minutes. The sections were observed by using a LEO EM-910 transmission electron microscope (LEO Electron Microscopy, Inc, Thornwood, NY), accelerating voltage of 80 kV, and digital images were taken with Gatan Orius SC 1000 CCD Camera (Gatan, Inc, Pleasanton, CA).

Crypt Isolation

Jejuna were flushed with ice-cold PBS, cut open along the long axis of the tissue, and cut into 1- to 2-cm pieces. Pieces were washed in 5 mL ice-cold PBS, placed in 5 mL ice-cold 5 mmol/L EDTA/1XPBS pH 7.4, and shaken at 4°C for 30 minutes. Next, pieces were gently shaken for 15 seconds. Pieces were moved to a fresh tube containing 5 mL ice-cold PBS and shaken for 1–2 minutes until crypts detach from tissue. We added 5 mL 2% sorbitol in 1× PBS, inverted to mix the samples, and filtered the crypts through a 70-μm filter. Filtered crypts were spun down at 200g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Supernatant was aspirated off, and pellet was used for RNA isolation or enteroid culture.

Crypt Culture

For enteroid culture, approximately 40 freshly isolated jejunal crypts were suspended in 10 μL of growth factor reduced Matrigel (cat. #356231; Corning, Corning, NY) per well of a 24- well plate by using methods similar to those previously published by Sato et al.3 After 30 minutes at 37°C to solidify the Matrigel, 200 μL of Wnt3a-free culture medium [DMEM/F12 Advanced media (cat. #12634-010; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× penicillin/streptomycin (cat. #15140-122; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× HEPES (cat. #15630-106; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× Glutamax (cat. # 35050-079; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× N2 (cat. # 17502-048; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1× B27 (cat. #17504-044; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 50 ng/mL EGF (cat. #2028-EG; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 100 ng/mL Noggin (cat. #250-38; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), and 500 ng/mL R-spondin (cat. #4645-RS/CF; R&D Systems)] was added to each well. Media were changed every other day. For quantification of budding, enteroids were evaluated on days 1, 3, and 6 after plating for number of buds. Enteroids with no buds were defined as spheres. The remaining enteroids were grouped into categories of 1, 2, 3, or 4+ buds. Data are presented as percentage.

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from jejunal crypts by using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Lack of contamination with genomic DNA was verified by running 1 μg of total RNA on a 0.9% agarose gel. Using the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix (cat. #4309169; Applied Biosystems, Inc, Foster City, CA) and Taqman Gene Expression assays for Mtgr1 (Mm01251302_m1), Spdef (Mm00600221_m1), Atoh1 (Mm00476035_s1), Gfi1 (Mm00515853_m1), Sox9 (Mm00448840_m1), and β-actin (Mm00607939_s1), 100 ng of total RNA was subjected to real time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Relative changes in expression levels were calculated by the ΔΔCt method using the Mist1WT total RNA as the baseline.

In Situ Hybridization

Using the RNAscope 2.5 Chromogenic Assay protocol outlined by the manufacturer (cat. #322300; Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA), in situ hybridization of Olfm4 was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded jejunal tissue with some modifications. Briefly, paraffin sections were baked at 60°C overnight and then deparaffinized. Sections were incubated in hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes at RT and subjected to antigen retrieval for 15 minutes in boiling target retrieval solution. Sections were then incubated in protease solution for 30 minutes at 40°C and then subjected to hybridization using the antisense probe for Olfm4. Slides were then blindly scored using the ACD scoring system on the basis of the amount of hybridization/cell.

Statistics

All quantitative results are presented as means ± standard deviation. All paired data were subjected to two-tailed t tests. Budding data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance using genotype and bud number as the independent variables and using Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Counts of PTAB cells were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance using genotype and cell type as the independent variables and using Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. For all comparisons, P value <.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was facilitated by services from the Cell Services and Histology Core of the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease (National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease grant P30 DK34987) and the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine Diagnostic Testing Services Histology Core. Immunohistochemical services were provided by the Histology Research Core Facility in the Department of Cell Biology and Physiology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC.

Footnotes

Author contributions CMD: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding; SK: acquisition of data; BS: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; JC: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data.

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01DK100508 and startup funds from the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences and the College of Veterinary Medicine at NC State University.

References

- 1.Porter E.M., Bevins C.L., Ghosh D., Ganz T. The multifaceted Paneth cell. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:156–170. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8412-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayabe T., Satchell D.P., Wilson C.L., Parks W.C., Selsted M.E., Ouellette A.J. Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/77783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato T., van Es J.H., Snippert H.J., Stange D.E., Vries R.G., van den Born M., Barker N., Shroyer N.F., van de Wetering M., Clevers H. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjerknes M., Cheng H. The stem-cell zone of the small intestinal epithelium: I—evidence from Paneth cells in the adult mouse. American Journal of Anatomy. 1981;160:51–63. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjerknes M., Cheng H. The stem-cell zone of the small intestinal epithelium: II—evidence from Paneth cells in the newborn mouse. American Journal of Anatomy. 1981;160:65–75. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001600106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corredor J., Yan F., Shen C.C., Tong W., John S.K., Wilson G., Whitehead R., Polk D.B. Tumor necrosis factor regulates intestinal epithelial cell migration by receptor-dependent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C953–C961. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00309.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poulsen S.S., Nexo E., Olsen P.S., Hess J., Kirkegaard P. Immunohistochemical localization of epidermal growth factor in rat and man. Histochemistry. 1986;85:389–394. doi: 10.1007/BF00982668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuzawa H., Sawada M., Kayahara T., Morita-Fujisawa Y., Suzuki K., Seno H., Takaishi S., Chiba T. Identification of GM-CSF in Paneth cells using single-cell RT-PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:897–902. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seno H., Sawada M., Fukuzawa H., Morita Y., Takaishi S., Hiai H., Chiba T. Enhanced expression of transforming growth factor (TGF) -alpha precursor and TGF-beta1 during Paneth cell regeneration. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1004–1010. doi: 10.1023/a:1010797609041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao J., de Vera J., Narushima S., Beck E.X., Palencia S., Shinkawa P., Kim K.A., Liu Y., Levy M.D., Berg D.J., Abo A., Funk W.D. R-spondin1, a novel intestinotrophic mitogen, ameliorates experimental colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1331–1343. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King S.L., Mohiuddin J.J., Dekaney C.M. Paneth cells expand from newly created and preexisting cells during repair after doxorubicin-induced damage. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G151–G162. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00441.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.VanDussen K.L., Carulli A.J., Keeley T.M., Patel S.R., Puthoff B.J., Magness S.T., Tran I.T., Maillard I., Siebel C., Kolterud A., Grosse A.S., Gumucio D.L., Ernst S.A., Tsai Y.H., Dempsey P.J., Samuelson L.C. Notch signaling modulates proliferation and differentiation of intestinal crypt base columnar stem cells. Development. 2012;139:488–497. doi: 10.1242/dev.070763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh R., Seth R., Behnke J., Potten C.S., Mahida Y.R. Epithelial stem cell-related alterations in Trichinella spiralis-infected small intestine. Cell Proliferation. 2009;42:394–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vidrich A., Buzan J.M., Barnes S., Reuter B.K., Skaar K., Ilo C., Cominelli F., Pizarro T., Cohn S.M. Altered epithelial cell lineage allocation and global expansion of the crypt epithelial stem cell population are associated with ileitis in SAMP1/YitFc mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pin C.L., Bonvissuto A.C., Konieczny S.F. Mist1 expression is a common link among serous exocrine cells exhibiting regulated exocytosis. Anat Rec. 2000;259:157–167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000601)259:2<157::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills J.C., Taghert P.H. Scaling factors: transcription factors regulating subcellular domains. Bioessays. 2012;34:10–16. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramsey V.G., Doherty J.M., Chen C.C., Stappenbeck T.S., Konieczny S.F., Mills J.C. The maturation of mucus-secreting gastric epithelial progenitors into digestive-enzyme secreting zymogenic cells requires Mist1. Development. 2007;134:211–222. doi: 10.1242/dev.02700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia D., Sun Y., Konieczny S.F. Mist1 regulates pancreatic acinar cell proliferation through p21 CIP1/WAF1. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1687–1697. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai Y.H., VanDussen K.L., Sawey E.T., Wade A.W., Kasper C., Rakshit S., Bhatt R.G., Stoeck A., Maillard I., Crawford H.C., Samuelson L.C., Dempsey P.J. ADAM10 regulates Notch function in intestinal stem cells of mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:822–834.e13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durand A., Donahue B., Peignon G., Letourneur F., Cagnard N., Slomianny C., Perret C., Shroyer N.F., Romagnolo B. Functional intestinal stem cells after Paneth cell ablation induced by the loss of transcription factor Math1 (Atoh1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8965–8970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201652109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson C.L., Kowalik A.S., Rajakumar N., Pin C.L. Mist1 is necessary for the establishment of granule organization in serous exocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract. Mech Dev. 2004;121:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo H.G., Jin R.U., Sibbel G., Liu D., Karki A., Joens M.S., Madison B.B., Zhang B., Blanc V., Fitzpatrick J.A., Davidson N.O., Konieczny S.F., Mills J.C. A single transcription factor is sufficient to induce and maintain secretory cell architecture. Genes Dev. 2017;31:154–171. doi: 10.1101/gad.285684.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Es J.H., van Gijn M.E., Riccio O., van den Born M., Vooijs M., Begthel H., Cozijnsen M., Robine S., Winton D.J., Radtke F., Clevers H. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pellegrinet L., Rodilla V., Liu Z., Chen S., Koch U., Espinosa L., Kaestner K.H., Kopan R., Lewis J., Radtke F. Dll1- and dll4-mediated notch signaling are required for homeostasis of intestinal stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1230–1240. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.005. e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riccio O., van Gijn M.E., Bezdek A.C., Pellegrinet L., van Es J.H., Zimber-Strobl U., Strobl L.J., Honjo T., Clevers H., Radtke F. Loss of intestinal crypt progenitor cells owing to inactivation of both Notch1 and Notch2 is accompanied by derepression of CDK inhibitors p27Kip1 and p57Kip2. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:377–383. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Q., Bermingham N.A., Finegold M.J., Zoghbi H.Y. Requirement of Math1 for secretory cell lineage commitment in the mouse intestine. Science. 2001;294:2155–2158. doi: 10.1126/science.1065718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregorieff A., Stange D.E., Kujala P., Begthel H., van den Born M., Korving J., Peters P.J., Clevers H. The ets-domain transcription factor Spdef promotes maturation of goblet and paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1333–1345. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.044. e1–e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shroyer N.F., Wallis D., Venken K.J., Bellen H.J., Zoghbi H.Y. Gfi1 functions downstream of Math1 to control intestinal secretory cell subtype allocation and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2412–2417. doi: 10.1101/gad.1353905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori-Akiyama Y., van den Born M., van Es J.H., Hamilton S.R., Adams H.P., Zhang J., Clevers H., de Crombrugghe B. SOX9 is required for the differentiation of paneth cells in the intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:539–546. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamal M., Dehlawi M.S., Brunet L.R., Wakelin D. Paneth and intermediate cell hyperplasia induced in mice by helminth infections. Parasitology. 2002;125:275–281. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002002068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chikada H., Ito K., Yanagida A., Nakauchi H., Kamiya A. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, Mist1, induces maturation of mouse fetal hepatoblasts. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14989. doi: 10.1038/srep14989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huh W.J., Esen E., Geahlen J.H., Bredemeyer A.J., Lee A.H., Shi G., Konieczny S.F., Glimcher L.H., Mills J.C. XBP1 controls maturation of gastric zymogenic cells by induction of MIST1 and expansion of the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2038–2049. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hess D.A., Strelau K.M., Karki A., Jiang M., Azevedo-Pouly A.C., Lee A.H., Deering T.G., Hoang C.Q., MacDonald R.J., Konieczny S.F. MIST1 links secretion and stress as both target and regulator of the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36:2931–2944. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00366-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaser A., Lee A.H., Franke A., Glickman J.N., Zeissig S., Tilg H., Nieuwenhuis E.E., Higgins D.E., Schreiber S., Glimcher L.H., Blumberg R.S. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adolph T.E., Tomczak M.F., Niederreiter L., Ko H.J., Bock J., Martinez-Naves E., Glickman J.N., Tschurtschenthaler M., Hartwig J., Hosomi S., Flak M.B., Cusick J.L., Kohno K., Iwawaki T., Billmann-Born S., Raine T., Bharti R., Lucius R., Kweon M.N., Marciniak S.J., Choi A., Hagen S.J., Schreiber S., Rosenstiel P., Kaser A., Blumberg R.S. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2013;503:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature12599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schewe M., Franken P.F., Sacchetti A., Schmitt M., Joosten R., Bottcher R., van Royen M.E., Jeammet L., Payre C., Scott P.M., Webb N.R., Gelb M., Cormier R.T., Lambeau G., Fodde R. Secreted phospholipases A2 are intestinal stem cell niche factors with distinct roles in homeostasis, inflammation, and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;19:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rukstalis J.M., Kowalik A., Zhu L., Lidington D., Pin C.L., Konieczny S.F. Exocrine specific expression of Connexin32 is dependent on the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Mist1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3315–3325. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y., Johansson C., Tran T., Bettencourt R., Itahana Y., Desprez P.Y., Konieczny S.F. Identification of a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor expressed in mammary gland alveolar cells and required for maintenance of the differentiated state. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2187–2198. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gifford G.B., Demitrack E.S., Keeley T.M., Tam A., La Cunza N., Dedhia P.H., Spence J.R., Simeone D.M., Saotome I., Louvi A., Siebel C.W., Samuelson L.C. Notch1 and Notch2 receptors regulate mouse and human gastric antral epithelial cell homoeostasis. Gut. 2017;66:1001–1011. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]