Abstract

Background:

Cancer patients undergo numerous invasive diagnostic procedures. However, there are only sparse data on the characteristics and determinants for procedure-related pain among adult cancer patients.

Methods:

In this prospective study, we evaluated the characteristics and determinants of procedure-related pain in 235 consecutive hematologic patients (M/F:126/109; median age 62 years, range 20–89 years) undergoing a bone marrow aspiration/biopsy (BMA) under local anesthesia. Questionnaires were used to assess patients before-, 10 min and 1–7 days post BMA. Using logistic regression models, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

165/235 (70%) patients reported pain during BMA; 92 (56%), 53 (32%) and 5 (3%) of these indicated moderate [visual analogue scale (VAS) ≥ 30 mm], severe (VAS>54mm) and worst possible pain (VAS = 100 mm), respectively. On multivariate analyses, pre-existing pain (OR = 2.60 95% CI 1.26–5.36), anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA (OR = 3.17 95% CI 1.54–6.52), anxiety about needle-insertion (OR = 2.49 95% CI 1.22–5.10) and low employment status (sick-leave/unemployed) (OR = 3.14 95% CI 1.31–7.55) were independently associated with an increased risk of pain during BMA. At follow-up 10 min after BMA, 40/235 (17%) patients reported pain. At 1, 3, 6 and 7 days post BMA, pain was present in 137 (64%), 90 (42%), 43 (20%) and 25 (12%) patients, respectively.

Conclusions:

We found that 3/4 of hematologic patients who underwent BMA reported procedural pain; one third of these patients indicated severe pain. Pre-existing pain, anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA or needle-insertion, and low employment status were independent risk factors.

The prevalence of pain in patients with cancer, regardless of the stage of the disease, has been found to be substantially higher than the general population.1-3 Indeed, pain is one of the major distressing symptoms in patients with a malignant disease.4,5 Anxiety is also common in people when diagnosed with cancer.6 In cancer patients, as well as in non-cancer patients, it is well known that pre-existing pain often amplifies the pain experience after surgery7 and that pain perception can be intensified if accompanied by anxiety.8,9 Further-more, surgery 10,11 and diagnostic procedures12 have also been reported to trigger long-lasting pain.

Cancer patients are frequently exposed to various invasive diagnostic procedures during the initial work-up and during the course of illness. Previous studies focusing on childhood cancer have shown that children fear medical procedures13 and that procedure-related pain is difficult to alleviate, even more difficult than cancer-related pain.14,15 Conversely, few studies have assessed procedure-related pain and particularly the factors associated with procedure-related pain in adult patients with cancer (Table 1).16-22

Table 1.

Pain during invasive diagnostic procedures in patients with cancer

| Authors (reference) |

No. of patients |

Type of procedure |

Anesthetic | Groups | Pain frequency | Pain on VAS (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brausi et al. (2007)16 | 40 | TUR of bladder tumor | Lidocaine | 60% VAS* 0–4 30% VAS* 4–6 10% VAS*>6 |

||

| Brennan et al. (2007)17 | 100 (50+50) |

FNAC of head and neck mass | Unknown | 21G 23G |

Mean VAS* 3.3 (1.94) Mean VAS* 1.8 (1.1) |

|

| Daltrey et al. (2000)18 | 98 | FNAC of breast mass | Lignocaine | Lignocaine 21G Lignocaine 23G without anaesthetic 21G without anaesthetic 23G |

Mean VAS* 3.0 Mean VAS* 2.1 Mean VAS* 5.1 Mean VAS* 2.9 |

|

| Gursoy et al. (2007)19 | 99 (50+49) |

FNAB of thyroid nodules | EMLA/placebo | EMLA Placebo |

82% pain 98% pain |

Mean VAS† 25.0 (22.3) Mean VAS† 40.0 (30.5) |

| Kilciler et al. (2007)20 | 340 (170+170) |

TRUS guided biopsy of prostate | No | Lithotomy position Left lateral decubitus position |

Mean VAS* 4.0 (1.93) Mean VAS* 2.7 (1.56) |

|

| Kuball et al. (2004)21 | 263 | BMA | Mepivacaine | 34% mild pain 39% moderate pain 15% severe pain 5% very severe pain 0.4% worst possible pain |

||

| Vanhelleputte et al. (2003)22 | 132 | BMA | Lidocaine | 84% pain | Mean VAS† 27.2 |

0–10 cm.

0–100 mm.

TUR, transurethral resection; TRUS, transrectal ultrasonography; FNAC, fine-needle aspiration cytology; FNAB, fine-needle aspiration biopsy; BMA, bone marrow aspiration/biopsy; G, gauge; VAS, visual analogue scale.

To increase our understanding on the characteristics and determinants of procedure-related pain among adult patients with cancer, we have conducted a large and comprehensive prospective study focusing on hematologic patients who underwent a bone marrow aspiration/biopsy (BMA) under local anesthesia.

Methods

Sample

The data collection periods were from May 1 to June 30, 2004, and September 1 to October 30, 2004. Two hundred thirty-five (median age 62 years, range 20–89 years, Table 2) of 263 consecutive adult patients who were scheduled for BMA at the outpatient clinic at Division of Hematology, Karolinska University Hospital, were included. Patients could only be enrolled once. Thirty-three patients were excluded due to: difficulties in understanding the Swedish language (n= 13), unwillingness to participate (n= 7), late arrival (n = 5), sedative medication (n = 2) or fainted (n = 1) before BMA. Pre-existing pain was present in 101 of included patients and 44 patients had taken pain medication the same day as the BMA (Table 2). The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm.

Table 2.

Characteristic of 235 patients undergoing BMA

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Number of subjects, n (%) | 235 (100) |

| Age, median years (range) | 62 (20–89) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Female | 109 (46) |

| Male | 126 (54) |

| Diagnosis according to BMA, n (%) | |

| Leukemia | 34 (14) |

| Multiple myeloma | 39 (17) |

| Lymphoma | 46 (19) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 18 (8) |

| Chronic myeloproliferative disorder | 31 (13) |

| Other hematologic disease | 42 (18) |

| Non-hematologic disease | 25 (11) |

| Site of BMA, n (%) | |

| Posterior iliac crest | 230 (98) |

| Sternum | 5 (2) |

| Type of BMA, n (%) | |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 67 (28) |

| Bone marrow biopsy | 88 (37) |

| Both aspiration and biopsy | 80 (35) |

| Previous BMA, n (%) | |

| No previous BMA | 100 (43) |

| 1–2 times | 76 (32) |

| 3–5 times | 27 (11) |

| >5 times | 32 (14) |

| Pre-existing pain, n (%) | 101 (43) |

| Pain medication taken the same day as BMA, n (%) | |

| Non-opioids | 19 (8) |

| Opioids | 8 (3) |

| Combination of non-opioids and opioids | 6 (2) |

| Adjuvant drugs | 3 (1) |

| Unknown type | 8 (3) |

BMA, bone marrow aspiration/biopsy.

Procedures

Patients were invited to participate in the study by one of the authors (Y. L.). Informed consent was obtained from all included patients before study enrollment. Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect data before and 10 min after the BMA. The participants were also requested to answer questions by telephone 1 week after BMA.

BMA.

Nine attending hematologists and seven hematology fellows performed 61 and 174 of the BMAs, respectively. Individuals, who were scheduled for BMA for the first time, received mail with written information about BMA procedures before their visit. At the visit, all patients were informed orally about the BMA procedure by the same physician who performed the BMA. According to the standard clinical praxis at Karolinska, no premedication were commonly used. As pain relief, a local anesthetic (Lidocaine 1% 10–20 ml) was given subcutaneously as well as through periostal infiltration. Five minutes after the local anesthetic was administered, BMA was carried out using an aspiration needle 15 G × 2.7 in. and/or a biopsy needle 11 G × 4 in. (Medical Device Technologies Inc. Gainesville, FL). A registered nurse was assisting the physician.

Data collection

Clinical information and measures of pain, discomfort and anxiety.

Using a standardized data entry form, the physician performing the BMA noted predefined clinical information regarding the patient. Using questionnaires, we obtained self-reported information from the patients about presence/absence of pain, discomfort and anxiety (the response options were: yes/no). The intensities of pain, discomfort and anxiety were measured with visual analogue scales (VAS) ranging from 0 to 100 mm with one statement in each range: 0 mm = no pain and 100 mm = worst possible pain, 0 mm = no discomfort and 100 mm = worst possible discomfort and 0 mm = no anxiety and 100 mm = worst possible anxiety. The participants were requested to mark the point at the line that best agreed with how the pain, discomfort and anxiety were experienced. The intensity of pain scored > 30 mm on VAS was considered to be equal to moderate pain and VAS > 54 mm to be equal to severe pain.23

Questionnaires before BMA.

A study-specific questionnaire was used including questions concerning height and weight, pain in daily life (pre-existing pain), pain before BMA, whether pain medication was taken the same day as BMA and anxiety about the BMA needle-insertion and anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA. Questions regarding pre-existing pain were adopted from the Karolinska Hospital Pain Questionnaire.12,24

Anxiety was measured with Stait Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)25, which is a well-validated and reliability-tested instrument.26 STAI is composed of two forms, STAI-S and STAI-T, with 20-item scales each. STAI-S measures the subject’s level or state of anxiety at a particular moment in time, whereas STAI-T refers to the trait or the general feelings of anxiety-proneness. The total score for each form has a range from 20 to 80 points; a higher score indicates a higher level of anxiety.

Demographic data were collected with a questionnaire27 with items concerning sex, age, marital status, foreign background, employment status, education level and perceived economical status.

Questionnaires 10 min after BMA.

Ten minutes after BMA, a study-specific questionnaire was administered including questions about: pain during BMA and BMA-related pain 10 min after BMA, discomfort during BMA, satisfaction with the pain management, whether information about BMA was received and whether the patient had undergone a BMA previously.

Telephone interview 1 week after BMA.

One week after BMA, an individual structured telephone interview was conducted by one of the authors (Y. L.). The patients were asked about the occurrence of BMA-related pain and pain intensity at 1, 3, 6 and 7 days following BMA. The patients were also asked about the use and type of medication for BMA-related pain.

Testing of the study-specific questionnaires.

Before the start of the study, the study specific questionnaires were revised by an expert group including attending physicians and registered nurses specialized in hematology or pain management. Also, a group of 24 patients with prior experience of invasive medical procedures were asked to comment on the clarity of questions, resulting in changes in a few questions.

Statistics

Before the start of the study, a power analysis was performed using a two-tailed χ2 test. A difference of 20% was considered as the smallest effect size of clinical relevance to detect between the two variable groups: anxiety and pain during BMA vs. no anxiety and pain during BMA. α was set to 0.05. With a sample size of 93 persons in each group, the study would have a power of 80% to yield a statistically significant result. An attrition rate of 20% was estimated and an accrual of 233 patients was planned.

Differences between groups were assessed with the Mann-Whitney U-test or the Kruskal-Wallis test. Proportions were compared with the χ2 test. Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficients were used to describe the relation between the STAI-S score and VAS scores for anxiety. A positive correlation coefficient between 0.10 and 0.29 was regarded as small, between 0.30 and 0.49 as medium and between 0.50 and 1.00 as large.28

A forward stepwise logistic regression was applied to estimate the probability of occurrence of pain during BMA. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to select variables to be tested for inclusion in the multivariate model. All factors with a P-value<0.05 were entered; see Table 3. The a priori selected term sex was also included. Estimated odds ratios (OR) with confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. The statistical calculations were performed using of the software Stat View 5.0.1 and SPSS 14.0.

Table 3.

Association between potential predictive factors and occurrence of pain during BMA

| Variable | Observation (n) | Pain during BMA rate, % | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | ||||

| <60 years | 108 | 76.8 | 1.82 (1.02–3.24) | 0.041 |

| ≥ 60 years | 127 | 64.5 | ||

| Sex* | ||||

| Female | 109 | 76.2 | 1.71 (0.97–3.04) | 0.064 |

| Male | 126 | 65.1 | ||

| Prior BMA* | ||||

| Yes | 100 | 75.6 | 1.82 (1.03–3.19) | 0.038 |

| No | 135 | 63 | ||

| Pre-existing pain* | ||||

| Yes | 101 | 78.2 | 2.05 (1.14–3.71) | 0.017 |

| No | 132 | 63.6 | ||

| Pain before BMA* | ||||

| Yes | 69 | 82.6 | 2.60 (1.29–5.23) | 0.007 |

| No | 164 | 64.6 | ||

| Anxiety about needle-insertion* | ||||

| Yes | 126 | 82.5 | 3.72 (2.05–6.75) | <0.001 |

| No | 109 | 56 | ||

| Anxiety about BMA result* | ||||

| Yes | 147 | 80.2 | 3.55 (1.98–6.36) | <0.001 |

| No | 88 | 53.4 | ||

| Received written information | ||||

| No | 143 | 70.6 | 1.03 (0.58–1.84) | 0.918 |

| Yes | 90 | 70 | ||

| Received oral information | ||||

| No | 24 | 70.8 | 1.02 (0.4–2.57) | 0.976 |

| Yes | 207 | 70.5 | ||

| Pain medication taken same day as BMA | ||||

| Yes | 44 | 75 | 1.34 (0.63–2.83) | 0.446 |

| No | 188 | 69.2 | ||

| Body mass index | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 91 | 71.4 | 1.08 (0.60–1.94) | 0.799 |

| <25 | 136 | 69.8 | ||

| BMA duration | ||||

| ≥ 15 min | 50 | 78 | 1.66 (0.79–3.48) | 0.179 |

| < 15 min | 182 | 68 | ||

| Experience of physician | ||||

| ≤ 100 BMA | 50 | 66 | 0.78 (0.40–1.52) | 0.464 |

| >100 BMA | 185 | 71.3 | ||

| Education of physician | ||||

| Hematology fellow | 174 | 68.3 | 0.71 (0.36–1.37) | 0.303 |

| Attending hematologist | 61 | 75.4 | ||

| Type of BMA | ||||

| Both aspiration and biopsy | 80 | 76.2 | 1.75 (0.89–3.43) | 0.106 |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 67 | 70.1 | 1.28 (0.65–2.53) | 0.481 |

| Bone marrow biopsy | 88 | 64.8 | ||

| Economical situation | ||||

| Bad | 20 | 75 | 1.36 (0.47–3.93) | 0.574 |

| Either bad or good | 44 | 72.7 | 1.21 (0.58–2.53) | 0.260 |

| Good | 167 | 68.9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 46 | 78.3 | 2.31 (0.78–6.90) | 0.132 |

| Divorced/separated | 12 | 75 | 1.93 (0.41–9.10) | 0.407 |

| Married/cohabiting | 147 | 70.1 | 1.50 (0.61–3.73) | 0.378 |

| Widow/widower | 23 | 60.9 | ||

| Foreign background | ||||

| Yes | 59 | 74.6 | 1.34 (0.69–2.62) | 0.388 |

| No | 172 | 68.6 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Sick-leave or unemployed | 79 | 83.5 | 2.96 (1.45–6.03) | 0.003 |

| Working or studying | 50 | 64.0 | 1.04 (0.51–2.08) | 0.924 |

| Retired | 106 | 63.2 | ||

| Education level* | ||||

| High† | 85 | 78.8 | 2.36 (1.09–5.12) | 0.030 |

| Intermediate‡ | 95 | 68.4 | 1.37 (0.67–2.82) | 0.389 |

| Low§ | 49 | 61.2 | ||

| Underlying diagnosis | ||||

| Multiple myeloma | 39 | 76.9 | 1.59 (0.57–4.49) | 0.377 |

| Lymphoma | 46 | 69.6 | 1.09 (0.42–2.84) | 0.855 |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 18 | 66.7 | 0.96 (0.28–3.22) | 0.943 |

| Chronic myeloproliferative disorder | 31 | 71.0 | 1.17 (0.41–3.36) | 0.772 |

| Other hematologic disease | 42 | 69.0 | 1.07 (0.40–2.82) | 0.897 |

| Non-hematologic disease | 25 | 68.0 | 1.02 (0.34–3.07) | 0.977 |

| Leukemia | 34 | 67.6 | ||

| Platelet count (109/l) | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.795 | ||

| Hemoglobin level (g/l) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.671 | ||

| Total STAI S 10*,¶, ∥ | 1.59 (1.22–2.05) | <0.001 | ||

| Total STAI T 10*,¶,** | 1.97 (1.29–3.01) | 0.002 |

The last category of each nominal variable was used as the reference category.

Variables selected for multivariate model.

University/similar.

Upper secondary school/similar.

Primary school/similar or lower.

Ten units increments.

Internal attrition; n = 13.

Internal attrition; n = 19.

BMA, bone marrow aspiration/biopsy.

Results

Procedure-related pain

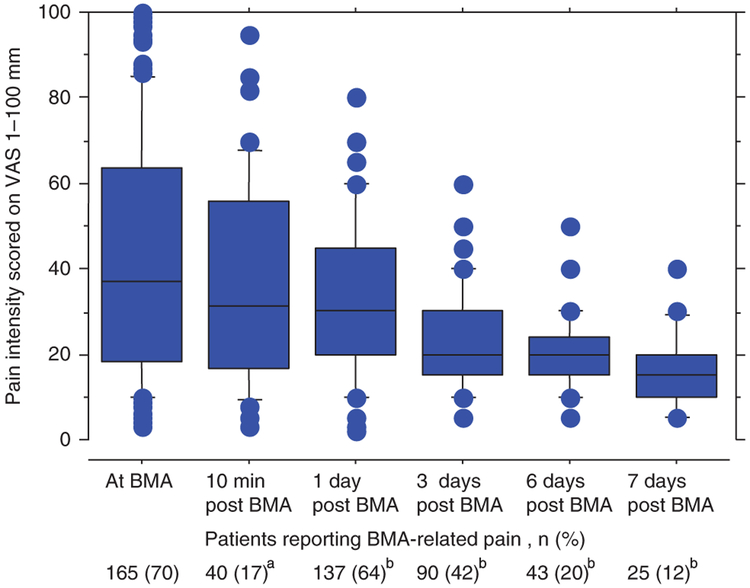

Among study participants, 165 patients (70%) reported pain during BMA, with a median VAS of 37 mm. In patients who reported BMA-related pain, 92 patients (56%) indicated moderate pain (VAS ≥ 30 mm), 53 patients (32%) reported severe pain (VAS > 54 mm) and five patients (3%) experienced the worst possible pain (VAS = 100 mm). At follow-up 10 min after BMA, 40/235 (17%) patients reported BMA-related pain with a median VAS of 31.5 mm (Fig. 1). At the subsequent follow-up 1, 3, 6 and 7 days post BMA, pain was present in 137 (64%), 90 (42%), 43 (20%) and 25 (12%) patients, respectively, with a median VAS ranging between 15 and 30 mm (Fig. 1). Twenty of 64 patients (31%) who did not report pain during BMA and 10 min after BMA reported pain at least on one occasion 17 days post BMA. There were no statistical differences in the clinical characteristics (including platelet counts) between patients who experienced an immediate BMA-related pain and patients who developed pain at day 1–7 (data not shown). Sixty-two patients took pain medication due to BMA-related pain on one or several occasions after BMA (non-opioids n = 49, opioids n = 6, combination of non-opioids and opioids n = 5, adjuvant drugs and non-opioids n = 2).

Fig. 1.

Intensity of bone marrow aspiration (BMA)-related pain during and after BMA in patients reporting occurrence of pain. Data are presented as median visual analogue scale (VAS) with 25th and 75th percentile ranges in boxes. The whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles and dots are outliers. Internal attrition: (a) n = 7, (b) n = 22.

Procedure-related discomfort

Discomfort during BMA was reported by 137 patients (59%, VAS median 40 mm, range 2–100 mm). Seventy four percent of patients who reported BMA-related pain mentioned discomfort during BMA compared with 21% of patients who did not report BMA-related pain (P< 0.0001). Patients reporting both pain and discomfort during BMA reported a higher pain intensity compared with patients who experienced pain but no discomfort (VAS median 42 mm vs. 25 mm, P = 0.027).

Factors associated with procedure-related pain

The association between occurrence of pain during BMA and potential predictive factors is outlined in Table 3. The variables that were significantly related to occurrence of BMA pain were younger age, prior BMA, pre-existing pain, pain before BMA, anxiety about the needle-insertion and the diagnostic outcome of BMA, high education level, low employment status (sick-leave or unemployed), and high STAI-S and STAI-T levels. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the contribution of the significant variables and the variable sex. We found that pre-existing pain, anxiety about the needle-insertion, anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA and low employment status (sick-leave or unemployed) were significantly related to the likelihood of pain during BMA (Table 4).

Table4.

Predictors of pain during BMA

| Variables | β | SE | Wald | df | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-existing pain | 0.95 | 0.37 | 6.66 | 1 | 2.60 (1.26–5.36) | 0.010 |

| Anxiety about needle-insertion | 0.91 | 0.36 | 6.22 | 1 | 2.49 (1.22–5.10) | 0.013 |

| Anxiety about BMA result | 1.15 | 0.37 | 9.83 | 1 | 3.17 (1.54–6.52) | 0.002 |

| Employment status | 11.37 | 2 | 0.003 | |||

| Retired vs. working or studying | −0.57 | 0.42 | 1.84 | 1 | 0.57 (0.25–1.29) | 0.176 |

| Retired vs. sick-leave or unemployed | 1.14 | 0.45 | 6.57 | 1 | 3.14 (1.31–7.55) | 0.010 |

Competing non-significant variables see Table 3.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMA, bone marrow aspiration/biopsy.

Pre-existing pain, anxiety about the needle-insertion, not received of written information about BMA, longer BMA duration and foreign background were factors associated with a higher pain intensity during BMA (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between variables and intensity of pain among patients experiencing BMA-related pain

| Variable | Pain during BMA (n) |

VAS |

P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | |||

| Age | ||||

| <60 years | 83 | 37 | 3–100 | 0.582 |

| ≥ 60 years | 82 | 38 | 3–100 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 83 | 39 | 4–100 | 0.398 |

| Male | 82 | 34.5 | 3–100 | |

| Prior BMA | ||||

| Yes | 102 | 42 | 3–100 | 0.080 |

| No | 63 | 30 | 3–100 | |

| Pre-existing pain | ||||

| Yes | 79 | 45 | 3–100 | 0.022 |

| No | 84 | 26 | 3–100 | |

| Pain before BMA | ||||

| Yes | 57 | 42 | 3–100 | 0.163 |

| No | 106 | 29.5 | 3–100 | |

| Anxiety about needle-insertion | ||||

| Yes | 104 | 45 | 3–100 | 0.0006 |

| No | 61 | 25 | 3–100 | |

| Anxiety about the result | ||||

| Yes | 118 | 41 | 3–100 | 0.121 |

| No | 47 | 30 | 3–100 | |

| Received written information | ||||

| Yes | 63 | 27 | 3–100 | 0.028 |

| No | 101 | 44 | 3–100 | |

| Received oral information | ||||

| Yes | 146 | 34 | 3–100 | 0.678 |

| No | 17 | 42 | 3–100 | |

| Pain medication taken same day as BMA | ||||

| Yes | 33 | 36 | 4–100 | 0.973 |

| No | 130 | 37 | 3–100 | |

| Body mass index | ||||

| ≥ 25 | 65 | 36 | 3–100 | 0.961 |

| <25 | 95 | 38 | 3–100 | |

| BMA duration | ||||

| ≥ 15min | 39 | 45 | 8–99 | 0.017 |

| < 15 min | 124 | 31 | 3–100 | |

| Experience of physician | ||||

| ≤ 100 BMA | 33 | 45 | 10–100 | 0.121 |

| >100 BMA | 132 | 33.5 | 3–100 | |

| Education of physician | ||||

| Hematology fellow | 119 | 40 | 3–100 | 0.069 |

| Attending hematologist | 46 | 25 | 3–100 | |

| Type of BMA | ||||

| Both aspiration and biopsy | 61 | 36 | 4–100 | 0.151 |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 47 | 45 | 4–100 | |

| Bone marrow biopsy | 57 | 27 | 3–100 | |

| Economical situation | ||||

| Bad | 15 | 72 | 13–100 | 0.057 |

| Either good or bad | 32 | 41 | 4–100 | |

| Good | 115 | 32 | 3–100 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 36 | 39 | 3–100 | 0.554 |

| Divorced/separated | 103 | 36 | 3–100 | |

| Married/cohabiting | 9 | 20 | 4–97 | |

| Widow/widower | 14 | 49.5 | 4–100 | |

| Foreign background | ||||

| Yes | 44 | 45 | 4–100 | 0.008 |

| No | 118 | 28 | 3–100 | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Sick-leave or unemployed | 66 | 30 | 3–100 | 0.072 |

| Working or studying | 32 | 46 | 10–95 | |

| Retired | 67 | 40 | 3–100 | |

| Education level | ||||

| High† | 67 | 27 | 3–99 | 0.328 |

| Intermediat‡ | 65 | 40 | 3–100 | |

| Low§ | 30 | 47 | 4–100 | |

| Underlying diagnosis | ||||

| Multiple myeloma | 30 | 39 | 3–100 | 0.739 |

| Lymphoma | 32 | 40.5 | 3–100 | |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 12 | 19.5 | 8–100 | |

| Chronic myeloproliferative disorder | 22 | 42.5 | 4–98 | |

| Other hematologic disease | 29 | 27 | 5–100 | |

| Non-hematologic disease | 17 | 42 | 4–99 | |

| Leukemia | 23 | 42 | 4–78 | |

Statistical tests used; Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test.

University/similar.

Upper secondary school/similar.

Primary school/similar or lower.

BMA, bone marrow aspiration/biopsy; VAS, visual analogue scale.

The mean STAI-S score for the total group of patients was 43.3 (SD 12.9) and 42.0 for STAI-T (SD 8.06). Patients with pain during BMA scored higher on STAI-S (45.3 vs. 38.5, P = 0.0005) and STAI-T (43.1 vs. 39.2, P = 0.004). Anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA was reported by 147 patients (63%, VAS median 52 mm), and anxiety about the BMA needle-insertion by 126 patients (54%, VAS median 50 mm). There was no significant difference between patients who had undergone BMA previously or not regarding anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA or needle-insertion or anxiety level measured with STAI-S. In a sub-analysis, we found large correlation coefficients between the STAI-S score and the VAS value for anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA (rs = 0.587, P < 0.0001) and the BMA needle-insertion (rs = 0.562, P < 0.0001).

Patient satisfaction

In total, 216 patients (93%) reported that they were satisfied with the pain management (local anesthesia) during the procedure. Those patients who were not satisfied with the local anesthesia and reported pain during BMA (7%) scored a higher intensity of pain compared with those patients who reported pain and were satisfied with the local anesthesia during BMA (VAS median; 80 vs. 30 mm, P = 0.0001).

Discussion

In this prospective study, designed to assess pain experience among adult patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing BMA under local anesthesia, we found that three out of four patients experienced pain with a median VAS of 37 mm. Among those patients who reported pain, one out of three scored severe or worst possible pain. We found pre-existing pain, anxiety about needle-insertion or BMA diagnostic outcome and low employment status (being on sick leave/unemployed) to be independent risk factors associated with procedure-related pain. This investigation provides new important clinical insights, of value for health care professionals involved in conducting invasive diagnostic procedures or developing protocols for minimizing procedure-related pain in cancer patients.

Consistent with results of prior studies investigating pain in adult cancer patients undergoing procedures under local anesthesia (Table 1), a large majority of our patients (70%) experienced pain during BMA. Among patients reporting pain, 32% scored severe pain and 3% worst possible pain, which is in agreement with previous studies on BMA-related pain where 16–33% of patients are reported to suffer from severe pain. 21,22,29 Procedural pain is often described as a temporary and transient experience. This is one of the first studies following procedural pain over time and, in our patients, pain was present in 64% 1 day after BMA and in 12% 1 week after BMA. The prolonged pain duration may be due to local edema/bleeding. However, the platelet count did not differ between those who experienced pain after BMA and those who did not. We have speculated on other potential explanations of our findings. Physiological phenomena such as peripheral and central sensitization of the nervous system following the initial nociceptive barrage could alternatively account for a part of this observation.11,30

To improve our understanding on the potential predictive factors for procedural pain, we assessed the influence of several variables. On multivariate analyses, we found pre-existing pain, anxiety about the needle-insertion or BMA diagnostic outcome and low employment status (being on sick-leave/unemployed) to be associated with occurrence of procedure-related pain. Pre-existing pain (44% of patients) that is chronic pain was also related to the experience of a higher intensity of pain. That is in conformity with the increasing evidence that chronic pain before surgery predicts increased intensity of postoperative pain.7 The relationship between past and present pain is suggested to be influenced by emotional status, expectations of pain and peak intensity of previous pain.31 A lower pain threshold in patients with chronic pain has furthermore been attributed to the fact that those taking opioid medications for pain may develop a tolerance, thereby requiring higher doses of analgesics.32,33 Because half of our patients had taken pain medications the same day as the BMA, and only a minority of those reported the use of opioids, this explanation seems to have limited impact in this context. Patients on sick-leave as well as unemployed persons were more likely to experience procedural pain. The finding concerning low employment status may reflect a more aggressive underlying disease and more active cancer therapy that potentially could manifest in a more pronounced vulnerability to pain. However, we were unable to explore this further in the present study. It is well known that anxiety before onset of pain predicts elevated pain intensity during acute pain perception.8,9 We found that both occurrence of anxiety about BMA needle-insertion and BMA diagnostic outcome predicted the occurrence of procedural pain. Many patients with malignancy fear a relapse of their disease34 and might therefore be anxious about the procedure outcome, as was stated by 63% of our patients.

Regarding the pain intensity and association with underlying factors, anxiety about the BMA outcome was not associated with a higher intensity of pain, whereas anxiety about needle-insertion was. Anxiety about needle-insertion could be associated with needle phobia, which is a common phenomenon affecting approximately 10% of a normal population with varying severity35, and the prevalence is probably higher in cancer patients.36 A longer duration of BMA was also related to a higher pain intensity, which is in agreement with the findings of other researchers.21,22 The perceived lack of written information was another factor associated with more intense procedural pain. Preoperative information has been found to reduce patients’ pain experience of postoperative pain.37 When most diagnostic invasive procedures are performed electively, there should be good opportunities to inform the patient for a better understanding. Adequate information might also decrease the intensity of procedure-related anxiety.

Even though 70% of our patients reported procedure-related pain, it must be highlighted that 93% were satisfied with the pain treatment. This is of interest, given that only local anesthesia was administered. High satisfaction despite pain is a known paradox, and may include a combination of expectations, relationship issues, previous experiences of pain relief and care goals.38 The discrepancy could be related to the fact that our patients believed that the physician had done his or her best to alleviate the pain,39 that the pain was unavoidable or that patients were satisfied with care given provided by the nurses. Ward and Gordon40 found that whether in-patients with severe pain were satisfied or not depended on average pain, but not current or worst pain.

Our study has several strengths including its prospective design, large sample size, high response rate and a broad range of variables assessed. But, there are some limitations as well. Among patients who reported no pain during BMA, 60% did not provide a VAS score and 40% indicated VAS 1–30 mm. These facts limited our ability to conduct a multivariate analysis of factors associated with BMA-pain intensity. An inherent limitation when using anxiety questionnaires is the risk of triggering patients’ degree of anxiety, which subsequently may have a negative influence on the pain experience. However, in our study, we believe that this impact was small because our data on frequency of pain are comparable to results from studies on BMA pain where anxiety was not explored.21,22 Furthermore, several statistical tests were conducted, increasing the risk of type I error.

The results of our study demonstrate that the majority of adult patients experience pain on undergoing BMA. Importantly, one-third of the patients who suffered from pain reported severe pain. In a few patients, the BMA-related pain lasted for 1 week. Pre-existing pain, anxiety about the diagnostic outcome of BMA and needle-insertion and low employment status (sick-leave/unemployed) were factors predicting occurrence of pain. These risk factors can be used to identify patients in need of complementary interventions to alleviate procedure-related pain.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Blood Cancer Society, the Centre for Health Care Science at Karolinska Institutet Stockholm County Council and the Intramural program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, US The authors wish to thank Bo Nilsson for valuable help with the statistical analysis and physicians and nurses performing the BMAs.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no relevant relationships and no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclosure of previous presentations: The results have previously been presented in part as an abstract at two conferences: the IASP 11thWorld Congress on Pain, Sydney, Australia, and the 5th World Congress of the European Federation of IASP Chapters, Istanbul, Turkey.

References

- 1.Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain: Ejp 2006; 10 (4): 287–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niscola P, Arcuri E, Giovannini M, Scaramucci L, Romani C, Palombi F, Trapé G, Morabito F. Pain syndromes in haematological malignancies: an overview. Hematol J 2004; 5 (4): 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 2007; 18 (9): 1437–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, Lepore JM, Fried-lander-Klar H, Coyle N, Smart-Curley T, Kemeny N, Norton L, Hoskins W, Scher H. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Qual Life Res 1994; 3 (3): 183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strang P Cancer pain - a provoker of emotional, social and existential distress. Acta Oncol 1998; 37 (7–8): 641–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aass N, Fossa SD, Dahl AA, Moe TJ. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer patients seen at the Norwegian Radium Hospital. Eur J Cancer 1997; 33 (10): 1597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalkman CJ, Visser K, Moen J, Bonsel GJ, Grobbee DE, Moons KG. Preoperative prediction of severe postoperative pain. Pain 2003; 105 (3): 415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Alexander GM, Pincus S, Mayes LC. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing hysterectomy. A repeated-measures design. J Psychosom Res 2000; 49 (6): 417–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozalp G, Sarioglu R, Tuncel G, Aslan K, Kadiogullari N. Preoperative emotional states in patients with breast cancer and postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003; 47 (1): 26–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman CR, Gavrin J. Suffering: the contributions of persistent pain. Lancet 1999; 353 (9171): 2233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain as an outcome of surgery. A review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology 2000; 93 (4): 1123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wincent A, Liden Y, Arner S. Pain questionnaires in the analysis of long lasting (chronic) pain conditions. Eur J Pain: Ejp 2003; 7 (4): 311–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enskar K, Carlsson M, Golsater M, Hamrin E, Kreuger A. Life situation and problems as reported by children with cancer and their parents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 1997; 14 (1): 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ljungman G, Gordh T, Sorensen S, Kreuger A. Pain in paediatric oncology: interviews with children, adolescents and their parents. Acta Paediatr 1999; 88 (6): 623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zernikow B, Meyerhoff U, Michel E, Wiesel T, Hasan C, Janssen G, Kuhn N, Kontny U, Fengler R, Görtitz I, Andler W. Pain in pediatric oncology - children’s and parents’ perspectives. Eur J Pain: Ejp 2005; 9 (4): 395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brausi MA, Verrini G, De Luca G, Viola M, Simonini GL, Peracchia G, Gavioli M. The use of local anesthesia with NDO injector (Physion) for transurethral resection (TUR) of bladder tumors and bladder mapping: preliminary results and cost-effectiveness analysis.[see comment]. Eur Urol 2007; 52 (5): 1407–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan PA, Mackenzie N, Oeppen RS, Kulamarva G, Thomas GJ, Spedding AV. Prospective randomized clinical trial of the effect of needle size on pain, sample adequacy and accuracy in head and neck fine-needle aspiration cytology. Head Neck 2007; 29 (10): 919–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daltrey IR, Kissin MW. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of needle gauge and local anaesthetic on the pain of breast fine-needle aspiration cytology. Brit J Surg 2000; 87 (6): 777–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gursoy A, Ertugrul DT, Sahin M, Tutuncu NB, Demirer AN, Demirag NG. The analgesic efficacy of lidocaine/prilocaine (EMLA) cream during fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules. Clin Endocrinol 2007; 66 (5): 691–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilciler M, Demir E, Bedir S, Erten K, Kilic C, Peker AF. Pain scores and early complications of transrectal ultrasonography guided prostate biopsy: effect of patient position. Urol Int 2007; 79 (4): 361–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuball J, Schuz J, Gamm H, Weber M. Bone marrow punctures and pain. Acute Pain 2004; 6: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanhelleputte P, Nijs K, Delforge M, Evers G, Vanderschueren S. Pain during bone marrow aspiration: prevalence and prevention. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003; 26 (3): 860–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain 1997; 72 (1–2): 95–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. II. Problems in the selection of relevant questionnaire items for classification of pain and evaluation and prediction of therapeutic effects. Pain 1984; 19 (2): 173–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spielberger CD, Vagg PR. Psychometric properties of the STAI: a reply to Ramanaiah, Franzen, and Schill. J Pers Assess 1984; 48 (1): 95–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forsberg C, Bjorvell H. Swedish population norms for the GHRI, HI and STAI-state. Qual Life Res 1993; 2 (5): 349–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wettergren L, Bjorkholm M, Axdorph U, Bowling A, Langius-Eklof A. Individual quality of life in long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma - a comparative study. Qual Life Res 2003; 12 (5): 545–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steedman B, Watson J, Ali S, Shields ML, Patmore RD, Allsup DJ. Inhaled nitrous oxide (Entonox) as a short acting sedative during bone marrow examination. Clin Lab Haematol 2006; 28 (5): 321–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolf CJ. Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature 1983; 306 (5944): 686–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalso E Memory for pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 1997; 110: 129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olorunto WA, Galandiuk S. Managing the spectrum of surgical pain: acute management of the chronic pain patient. J Am Coll Surg 2006; 202 (1): 169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapp SE, Ready LB, Nessly ML. Acute pain management in patients with prior opioid consumption: a case-controlled retrospective review. Pain 1995; 61 (2): 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee-Jones C, Humphris G, Dixon R, Hatcher MB. Fear of cancer recurrence - a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrence fears. Psycho-Oncol 1997; 6 (2): 95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamilton JG. Needle phobia: a neglected diagnosis. [see comment]. J Fam Pract 1995; 41 (2): 169–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kettwich SC, Sibbitt WL Jr., Brandt JR, Johnson CR, Wong CS, Bankhurst AD. Needle phobia and stress-reducing medical devices in pediatric and adult chemotherapy patients. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2007; 24 (1): 20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmons ME, Bower FL. The effect of structured preoperative teaching on patients’ use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and their management of pain. Orthop Nurs 1993; 12 (1): 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawson R, Spross JA, Jablonski ES, Hoyer DR, Sellers DE, Solomon MZ. Probing the paradox of patients’ satisfaction with inadequate pain management.[see comment]. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002; 23 (3): 211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mueller PR, Biswal S, Halpern EF, Kaufman JA, Lee MJ. Interventional radiologic procedures: patient anxiety, perception of pain, understanding of procedure, and satisfaction with medication - a prospective study. Radiology 2000; 215 (3): 684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward SE, Gordon DB. Patient satisfaction and pain severity as outcomes in pain management: a longitudinal view of one setting’s experience. J Pain Symptom Manage 1996; 11 (4): 242–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]