Abstract

With a policy shift towards personalisation of adult social care in England, much attention has focused on individualised support for older people with care needs. This article reports the findings of a scoping review of United Kingdom (UK) and non-UK literature, published in English from 2005-2017, about day centres for older people without dementia and highlights the gaps in evidence. This review, undertaken to inform new empirical research, covered the perceptions, benefits and purposes of day centres.

Searches, undertaken in October/November 2014 and updated in August 2017, of electronic databases, libraries, websites, research repositories and journals, identified seventy-seven relevant papers, mostly non-UK.

Day centres were found to play a variety of roles for individuals and in care systems. The largest body of evidence concerned social and preventive outcomes. Centre attendance and participation in interventions within them impacted positively on older people’s mental health, social contacts, physical function and quality of life. Evidence about outcomes is mainly non-UK.

Day centres for older people without dementia are under-researched generally, particularly in the UK. In addition to not being studied as whole services, there are considerable evidence gaps about how day centres are perceived, their outcomes, what they offer, to whom and their wider stakeholders, including family carers, volunteers, staff and professionals who are funding, recommending or referring older people to them.

Keywords: Day centre, day care, older people, social care, literature review, outcomes

Introduction

This article presents and discusses the findings of a systematically conducted scoping review of English-language literature, published between 2005 and 2017, about the perceptions, benefits and purposes of day centres for older people.

‘Day centre’ is a generic term. It describes building-based services that offer a wide variety of programmes and services. They may be owned by different types of provider, operate in different types of building and may differ in size, target clientele and the way they are funded. Accounts of the development of English social care and day centres (e.g. Thane 2009, Tester 1989, Tucker et al. 2005) report that day centres have been an integral part of social care in England since the National Assistance Act 1948 (HM Government 1948). This Act permitted local authorities to contribute financially to voluntary organisations that provided recreational facilities, such as day centres, for adults with disabilities. This was extended to include older people by an amendment to the Act in 1962 (HM Government 1962). For this study, day centres are defined as community building-based services that provide care and/or health-related services and/or activities specifically for older people who are disabled and/or in need, which people can attend for a whole day or part of a day. Generalist day centres are those that do not specialise in the care of people with dementia or palliative care, for example, and do not target their services solely at a particular demographic sub-group, such as certain ethnic groups or homeless people.

The last detailed study of day care in England and Wales was published almost three decades ago. A government funded study, it reported that day centres, day care and hospitals aimed to help older people remain independent in the community, provide social care and company, rehabilitation, assessment and treatment, and support for carers (Tester 1989). Later UK research confirmed that day centres met these aims (Andrew et al. 2000, Davies et al. 2000, Burch and Borland 2001, Powell and Roberts 2002) which were policy-relevant. While certain policy themes remain the same since this body of research was undertaken, the overall policy and funding environment in which day centres exist has since changed considerably.

The Care Act 2014 (HM Government 2014) requires local authorities in England to arrange services that promote well-being and help prevent or delay deterioration, and to support a market that delivers a wide range of care and support services. It continues the themes that have featured strongly across policy for several decades: promotion of good health and well-being, prevention of decline, and voluntary or community support to both older people and carers, and enabling people to choose to remain at home while growing older, to 'age in place' (HM Government 2012, 2010, Department of Health 1998, 2006).

Further to the increased emphasis on a market of social care, by the NHS and Community Care Act 1990 (HM Government 1990) which rendered local authorities enablers rather than providers, people eligible for publicly funded social care have been transformed into consumers of services by the adult social care policy of ‘personalisation’. Personalisation, a central part of the ‘transformation’ (modernisation) of adult social care (Department of Health 1998), was conceptualised as a route to improving outcomes through empowerment, by giving people eligible for publicly-funded services choice and control over their care and support so it would meet individual needs and preferences and support continued independence and societal participation (HM Government 2007, Department of Health 2010). Assessing and planning care and support in a person-centred way and individualising finances were key, and would enable ‘individually tailored support packages’ (HM Government 2007: 3), as was transparency of the resource allocation process. To enable flexible services, personalisation was expected to involve ‘reduction of inflexible block contracts’ and budget-pooling (Department of Health 1998: 15). People eligible for public funding may opt to receive cash (direct payments) with which to purchase care or it may be organised on their behalf (managed personal budgets).

These policies are set against a backdrop of reduced funding and reduced numbers of older people with higher needs receiving publicly funded care (Dunning 2010, Age UK 2015, Ismail, Thorlby and Holder 2014, Fernandez, Snell and Wistow 2013), a move from low-level support to more intensive support and a reduction in voluntary sector services funded by block grants (Fernandez, Snell and Wistow 2013).

Outcomes Frameworks for adult social care, health and public health were introduced in 2014-15 (Department of Health 2013). The social care framework focuses on enhancing the quality of life of people with care and support needs, delaying and reducing the need for care and support, ensuring that people have a positive experience of care and support and safeguarding vulnerable adults, and the health framework has similar themes. Annual reports against frameworks are informed by national surveys undertaken by local authorities.

The policy of personalisation, marketisation of social care, a shift to competitive tendering and budget cuts are impacting on day centres for older people. Tensions arise when implementing policy in a context of cuts with differing interpretations of a key driver, and when assumptions predominate over evidence. Both from an older people’s perspective and more broadly, some fundamental principles and the implementation of personalisation have been subject to considerable analysis, debate and criticism (e.g. Barnes 2011, Needham 2012, 2013, Scourfield 2007, Spicker 2013, Needham and Glasby 2014, 2015, Powell 2012, Roulstone and Morgan 2009, Lymbery and Postle 2015, Woolham et al. 2017). Topics covered include interpretations of the concept; overshadowing of its outcomes-improving ‘spirit’ by take-up of individualised funding mechanisms; inadequately transparent resource allocation systems; lack of financial resources required for successful implementation; its potential contribution to efficiencies, its (un)suitability and (in)effectiveness for different groups of people; failure to acknowledge the varying circumstances of different groups of people; assumptions concerning a universal desire for individual services, and the ethics of a statutory shirking of responsibilities. Furthermore, while the notion of choice underpins policy, the potential for financial savings is argued to be of similar importance (Lymbery and Postle 2015) despite the limited potential for reducing public funding being acknowledged (e.g. National Audit Office 2011).

Regarding service options, the framing of choice in social care as an individual matter is argued to ignore the fundamentally public nature of social care (Stevens et al. 2011) in which individual choice may impact on others. There are several aspects to its public nature, including funding and access to services. Lymbery and Postle (2015: 83) asserted that ‘there is little understanding that the choice that one person makes might tend to affect the range of options open for another’, something which relates to the quasi-market in which social care services operate. Although intended to offer greater choice, control and satisfaction to ‘consumers’ (Audit Commission 2006), market oversight is variable (National Audit Office 2011). Despite user and carer need and market analyses being central to strategic commissioning principles (Audit Commission 1997), consultations about day service provision that inform ‘strategic’ commissioning by local authorities vary in scope, length and responsiveness (Needham and Unison 2012, Orellana 2010). Commissioning decisions are not always based on evidence or service user feedback (Miller et al. 2014). Needham concluded, based on her analysis of the narratives of personalisation advocates and a survey, that a combination of personalised funding with funding cuts ‘has led to inadequate attention to the potential for an undersupply of collective and public goods (…) without sufficient responsiveness to how and what individuals want them to commission’ (2013: 1). Thus, local authorities may be contravening market principles of supply and demand. Additionally, dubitable intimations that core funding or subsiding services alongside providing personalised funding means double-funding services seemingly also influence commissioning practice (Orellana 2010).

Local authorities no longer view day centres as a core service (Needham 2014) and their decommissioning or closure is increasingly common (ADASS 2011, 2014), particularly those providing low-level support (ADASS 2011). Closures are justified by changing policy and funding structures which, some believe, render day centres an outdated service model (Tyson et al. 2010, Needham 2014, Leadbetter 2004). This is despite some older people expressing a wish to access them (Needham 2014, Bartlett 2009, Wood 2010, Miller et al. 2014), a preference reportedly different from that of younger people with physical or learning disabilities or mental health problems (Wood 2010). Furthermore, narratives have repeatedly referred to the (in)appropriateness of group services in a ‘modernised’ environment. Publicly-funded, collective and traditional building-based services, such as day centres (Cottam 2009, Duffy 2010) are purportedly ‘insufficiently attuned to individual needs and wishes‘ (Barnes 2011: 164). Yet individualising services, rather than personalising them, when group services may be preferred, imposes the values of those holding power on ‘what constitutes quality of life‘ for the most vulnerable, undermining ‘the actual and potential value of collective provision’ (Barnes 2011: 164) and leading to ‘enforced individualism’ (Roulstone and Morgan 2009: 334) which may, or may not, meet individual needs. Thus, concerns have been expressed that the policy of personalisation may ‘lead to under-emphasis on the social and collective, as opposed to individual, outcomes of social care’ (Rees, Mullins and Bovaird 2012: 8).

Within the context of change outlined above, it is important to better understand the purpose, benefits and perceptions of day centres, to discover what day centres’ potential may be and to identify gaps in the evidence. Yet national data are difficult to obtain in England as day centres are not required to register centrally or locally. The scant English data cover people aged over 65 years in receipt of local authority provided or commissioned services; from this it is reported that day centres are attended by around 10% (n=59,300) of this group (NHS Digital 2014), exluding private payers and centres not in receipt of local authority funding. Of these attenders, 54% are physically frail or disabled, 19% have dementia and 4% have hearing, vision or dual sensory loss. Furthermore, the difficulties of researching a service described by its location rather than its aims or what it offers were highlighted in Manthorpe and Moriarty’s (2013, 2014) review of the literature from an equalities perspective, as were the gaps in and overall lack of evidence about English day centres despite the importance of data about those funding such services or purchasing them on behalf of individuals.

This article reports the findings of a scoping review which was undertaken to inform new empirical research. After setting out the review methods, the findings open with an overview of the included literature and the types of non-UK day centres in the literature, their aims and what they offer. This is followed by a profile of attender participants in the studies, then findings about how day centres are perceived. Outcomes are presented under five themes, four of which are the aims of day centres as specified in the literature: providing social and preventive services, supporting independence, supporting attenders’ health and daily living needs and supporting family carers. Under each of these, outcomes resulting from centre attendance are presented separately from those resulting from interventions undertaken in centres. The fifth theme, defined later, is that of process outcomes. Finally, findings about the systemic purpose of day centres are presented. These are then discussed in the light of the evidence gaps, and a summary of the limitations of the literature and the strengths and limitations of this review given. The article concludes by summarising the gaps in knowledge identified.

Methods

Overall aim and review questions

The review aimed to establish the levels of existing knowledge in relation to three questions:

How are day centres perceived?

Who benefits from day centres and how?

What is the purpose of day centres?

It was undertaken to inform new empirical research investigating, from multiple perspectives, the role and purpose of four English generalist day centres for older people, how they are viewed and their use within a changing policy and practice context, including the potential for day centres’ development. As well as identifying gaps to inform the study, understanding what is already known about day centres in other contexts was valuable, and this review’s findings informed the discussion of the study’s empirical findings. The study was supported by The Dunhill Medical Trust (grant number: RTF59/0114) and received ethical approval from the Health Research Authority’s Social Care Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 15/IEC08/0033).

Outside the review’s scope was a comparison of the varying international operational models of day centres and the health, social care and funding systems within which these operate, although a summary of those appearing in the literature is provided.

Search strategies

A systematic approach was taken, with transparent and replicable processes set at the start (Gough, Oliver and Thomas 2012, Campbell Collaboration undated). Given the expected scant English literature on this topic, a three-stage, systematic, comprehensive and sensitive search strategy that aimed to identify as much diverse and potentially relevant material as possible was adopted (see Table 1). Database and library searches were undertaken in October 2014 and hand-searches of websites, research repositories and journals conducted in November 2014. Alerts to Google Scholar and key journals’ contents pages were then set up to capture any new literature in November 2014; in August 2017, these were reviewed and a search of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) evidence database undertaken.

Table 1. Literature review search strategy.

| Phase | Search details |

|---|---|

|

Phase 1 Database and library searches (16-27 Oct 2014) |

Bibliographic Databases (12): Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cochrane Library, IngentaConnect, JISC Journal Archives, NHS Evidence Search, OCLC FirstSearch - Article First, OvidSP - Social Policy and Practice (includes Centre for Policy on Ageing’s database AgeInfo), PubMed, Scopus, Social Services Abstracts, Web of Science Core Collection, Web of Science MedLine Websites/internet search engines: British Library e-theses online service (EThOS), Open Grey, Social Care Online, WorldCat Dissertations and Theses Libraries: King's College (including PURE research portal), British Library, Senate House |

|

Phase 2 Hand-searched (6-10 Nov 2014) |

Websites of relevance, research repositories and journals: Age UK, Brunel Institute for Ageing Studies, DEMOS, Independent Age, Institute for Public Policy Research, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, King’s Fund, Lancaster Centre for Ageing Research, National Development Team for Inclusion, National Centre for Social Research, Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, Personal Social Services Research Unit (Manchester), Personal Social Services Research Unit (LSE), ResearchGate, Research into Practice for Adults, Personal Social Services Research Unit (Kent), Sheffield Institute for Studies on Ageing, Social Care Workforce Research Unit (SCWRU), Social Science Research Network, Social Policy Research Unit (York),Southampton Centre for Research into Ageing, Swansea Centre for Innovative Ageing Peer-reviewed journals hand-searched: Ageing & Society, The Gerontologist, Health & Social Care in the Community, International Journal of Integrated Care, Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, Research Policy and Planning, Social Policy & Society, Working with Older People |

|

Phase 3 Alerts set up (Nov 2014) |

Weekly Google Scholar alert and alerts to tables of contents of above journals and Journal of Applied Gerontology, British Journal of Social Work, Critical Social Policy, Journal of Gerontological Social Work, Geriatrics and Gerontology International, Journal of Integrated Care, Journal of Public Administration, Research and Policy and Sociology of Health and Illness. |

| Search (Aug 2017) | Search of NICE’s evidence database undertaken. |

Following testing and refinement, combinations of keywords used in searches aimed to compensate for terminological variation and reflected the focus on the role, purpose or place of day centres, perceptions of day centres and outcomes for older attenders, their informal or family carers and those working and/or volunteering in or providing day centres (see Table 2). The broad focus of the ‘purpose’ of day centres and perceptions of them necessitated inclusion of those commissioning or funding and making referrals or signposting to them. Results were further narrowed by language, date (2000-2014), and database categories.

Table 2. Key words used in structured searches of bibliographic databases.

| Subject area | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Older people | Elder/elderly, old/older, aged, senior |

| AND | |

| Day care / service / centre | Day centre/er, senior centre/er, day care, day care + care home / nursing home |

| AND | |

| Commissioning, referring/signposting, staff/volunteers/managers, role, outcomes, which older people attend |

Commissioning: Fund(ing), Commission*, Purchas* Referrers/signposters: Referr*, Signpost* Staff/volunteers/managers: Staff, Volunteer, Manager Carers: Care, Carer, Caregiver, Relative, Family Role / purpose / outcomes: Purpose, Role, Outcome, Impact Which older people? User profile, Attendees, Clients, Clientele, Patients, Service user |

| NOT | |

| Exclusions | Child*, Paediatric, Day hospital*, Palliative, Hospice |

Where * denotes alternative word endings

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Literature was included if it concerned older people and day centres, was published in English from 2000 up to the date of the search and explored the role, purpose or place of day centres, outcomes for older attenders/carers/volunteers/staff or perceptions of day centres. Literature was excluded if it was about day centres operating within end-of-life/palliative/hospice services, homeless people or children, as these have discrete purposes and users, or if it could not be retrieved in full.

Inclusion criteria were revised after screening on title and abstract as a large volume of literature remained. During full text screening, a sizeable international body of literature, including literature reviews, emerged about day centre attenders with dementia and their carers (e.g. Quayhagen et al. 2000, Zank and Frank 2002, Gaugler et al. 2003a, Gaugler et al. 2003b, Woods et al. 2006, Gustafsdottir 2011, Zarit et al. 2011, Fields, Anderson and Dabelko-Schoeny 2012, Zarit et al. 2014). For this reason, and because a study of the value, meaning and purpose of day centre for people with dementia in England was being undertaken from 2014-16 at the University of Manchester, remaining studies in which more than approximately one third of samples had dementia were excluded (e.g. 39% in Katz et al. 2011) unless findings were relevant and separated from findings about people without dementia (e.g. Kuzuya et al. 2012, 2006). This proportion was due to the authors’ experience that English generalist day centres for older people were unlikely to have more than around one third of service users with dementia. Literature published from 2000-2004 was also excluded since inherent publishing delays meant that findings were likely to be less relevant to the current policy and service situation. Papers concerning a very specific context or population that may not be relevant to generalist day centres in England were also excluded (e.g. service preferences of Japanese American baby boomers compared with older Japanese migrants). Master’s degree dissertations retrieved were excluded unless findings had been published and were retrieved.

Paper selection process

In total, 77 papers (of 71 studies) were included in this review.

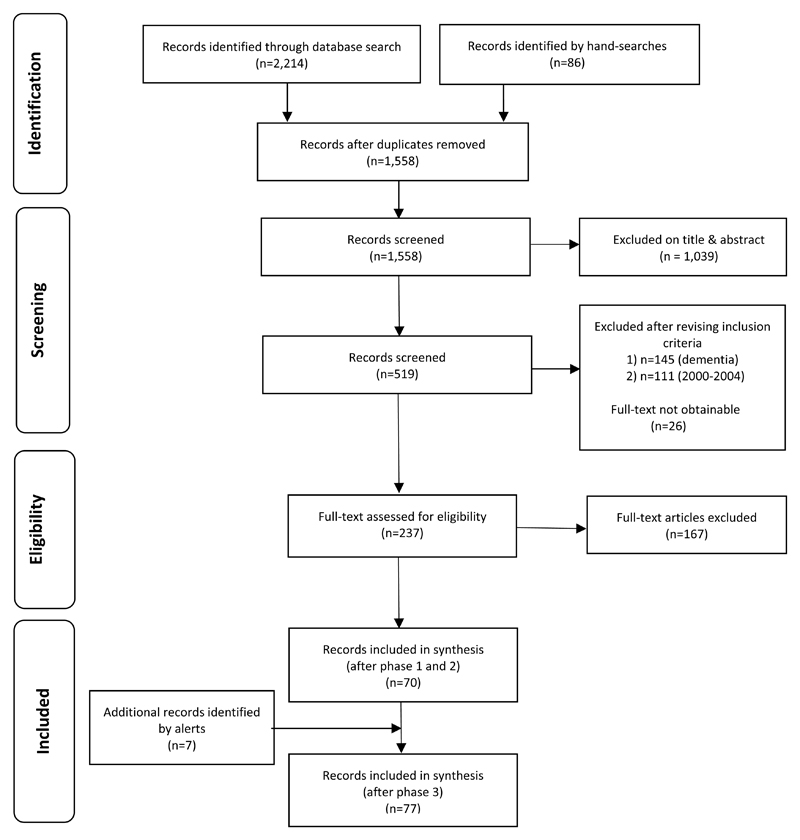

Literature was saved in EndNote bibliographic software, duplicates removed, and inclusion and exclusion criteria applied on title and abstract, or full text if relevance was unclear. Full text of remaining literature was then retrieved and screened. The evidence was not rated; even within the medical field, it has been acknowledged that ‘the use of any quality score can be fraught with difficulty’ (Torgerson, 2003: 54). A modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme’s (CASP) three stage approach to appraising evidence which uses a staged ‘yes’, ‘can’t tell’, ‘no’ approach (CASP 2013b, 2013a) was employed. First, the validity of results is evaluated based on whether a clearly focused issue was considered with an appropriate methodology. If ‘yes’ then methodological details are considered. Papers considered valid and minimally biased continue to the second and third stages, in which findings are reviewed for importance and usefulness. A different set of questions is used for different methodologies. This approach does not assign numerical scores based on quality. This was considered appropriate given the review’s location in social care and the breadth of type of material. To compensate for inclusion not being score-based, limitations were identified. Thus, all papers included in the review addressed a clearly focused issue, used an appropriate methodology and were judged relevant and with useful findings. To inform this stage, data from all papers were extracted into evidence tables detailing aims and location of studies, day centre type, publication type, theoretical frameworks used and sample, design, methods, findings and limitations identified. Figure 1 summarises the literature, the searching and screening process. Details of all the literature included in this review are in Tables S1, S2 and S3 of the supporting material in the online version of this article.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram (Moher et al. 2009).

Synthesis of papers’ findings

Following Gough, Oliver and Thomas (2012) and integrative review methodology (Whittemore and Knafl 2005), findings of both qualitative and quantitative research are presented together in a configurative synthesis, in which data are organised to answer the review question by identifying themes ‘to build up a picture of the phenomenon of interest’ (Gough, Oliver and Thomas 2012: 188). In other words, this synthesis reports qualitative and quantitative research findings together thematically, with findings of interventions at day centres presented separately from those concerning attendance only.

Terms used in this paper

The terms ‘day centre’ and ‘attendance’ are used throughout, regardless of day centre type or how older people ‘use’ day centres which, in many studies, was not stated. ‘Significant’ refers to findings that are statistically significant using criteria defined in papers. As a systematic review reporting both positive and negative findings, the term ‘outcome’ is used to refer to any impact, effect or consequence (Glendinning et al. 2008) whether beneficial or not.

Findings

General overview of included studies’ characteristics

In total, 77 papers met the criteria for this review. Evidence tables S1-S3 detail the location of studies, type of day centre referred to, publication type, theoretical frameworks used and sample, design, methods, findings and limitations. Three categories of literature were apparent: i) Day centres or their attenders (46 papers), ii) Not focused on day centres but addressed review questions (10) and iii) Interventions carried out in day centres (21).

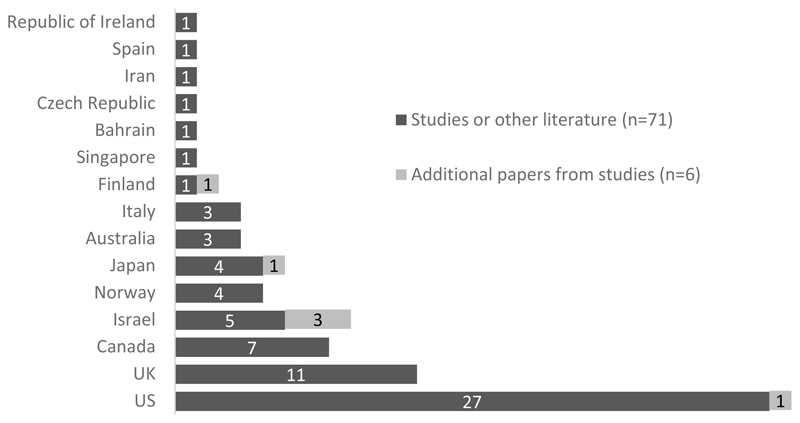

Most of the literature was non-UK (see Figure 2), with the largest proportion from the United States (US) and was published in peer-reviewed journals, most commonly gerontological, with about half as many in geriatric or health journals. Some appeared in social work, social care or public health journals, a few in other specialist topics (e.g. activities) and only one in a social policy journal.

Figure 2. Countries of papers.

Excepting studies relating to interventions in day centres, just over half the literature was quantitative. A number used validated scales (n=16) which mostly measured depression, loneliness, physical function, health-related quality of life or social support. Many studies interviewed participants (n=22) or were based on surveys (n=9). Secondary analysis of data (n=7), observation (n=4), focus groups (n=6) and questionnaires (n=3) were less common methods. Eight papers were literature reviews (n=2), with smaller numbers being think pieces or expert opinion articles (n=4), evaluations (n=3) or case studies (n=2).

Types of day centre in the literature, their aims and what they offer

An array of operational models appeared in the literature illustrating the breadth and complexity of day centres, both within and between countries (see Table 3). Also meriting acknowledgement are further differences including, for example, funding mechanisms and provider organisations. Detailed outline or comparison of the varying international operational models of day centres and the health, social care and funding systems within which these operate were outside the scope of the review. In descriptions, most centres were said to provide socialisation and activities while some offered health services and rehabilitation. Target users included functionally impaired/frail, socially isolated or retired people and, less often, family carers. Four possible aims of day centres were stated:

To provide social and preventive services (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005, Lund and Englesrud 2008, Boen et al. 2010, Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010, Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, MaloneBeach and Langeland 2011, Kuzuya et al. 2012, Iecovich and Biderman 2013b, Fawcett 2014, Marhankova 2014, Liu et al. 2015, Shahbazi et al. 2016, Kelly 2017).

To support continued independence of attenders (Ron 2007, Schmitt et al. 2010, Kuzuya et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2015, Kelly et al. 2016).

To supportattenders’ health and daily living needs (Lund and Englesrud 2008, Boen et al. 2010, Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, Schmitt et al. 2010, Kuzuya et al. 2012, Al-Dosseri et al. 2014, Fawcett 2014, Liu et al. 2015, Shahbazi et al. 2016).

To enable family carers to have a break and/or continue with employment (Schmitt et al. 2010, Al-Dosseri et al. 2014, Fawcett 2014).

Table 3. Models of day centre appearing in the literature.

| Country | Name | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Day club | Newer model incorporates concepts of well-being and active ageing into traditional model that provides respite and supports older people with increasing impairments. Many renamed as Day Clubs to reflect new focus (Fawcett 2014). |

| Bahrain | Day care center | Provide health (including rehabilitation) & physical activities, meals, ‘a chance to socialize and have fun in a community based group’ and aim to reduce burden on family carers (Al-Dosseri et al. 2014:2). |

| Canada | Senior centre | ‘places for older adults to socialize or share specific interests with their peers… main goal is to meet the needs of retired people’ (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005:18). |

| Adult day service | ‘a setting where older people can engage in supervised, social, recreational, and therapeutic activities during the day’ (Kelly 2017:552) which offer ‘health monitoring, personal care, medication management, meals and social/recreational activities’ (p554). They are ‘situated amid the continuum of home support services, which are designed to support older adults with functional and/or cognitive impairment so that they can continue to live at home’ (Kelly et al. 2016:814). Kelly at al. 2016 describes these as a ‘social and emotional model’. | |

| Czech Republic | Senior centre | Place to engage in active ageing activities and meet people (Marhankova 2014). |

| England | Day care centre | ‘…low level services … involves a variety of activities and caters for a range of people with differing levels of needs and dependency (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010:2) |

| Iran | Adult day care | ‘… mostly established during the last decade….work under the direction and supervision of the State Welfare Organization (SWO) of Iran, and their costs are covered by the SWO. …. the SWO has prepared a service package for empowerment of older adults, including medico-rehabilitative and psycho-social services, based on bio-psychosocial model… All day care centres … required to deliver their services according to this package’ (Shahbazi et al. 2016:719) |

| Israel | Day centre | Aim to enhance wellbeing of frail people lacking social contact and support (Iecovich and Biderman 2013b). Part of package of community services offered through Long-Term Care Insurance Law 1988 which encourages continued residence in community with increasing disability or dependence (Ron 2007). |

| Japan | Day care | A 'program of nursing care, rehabilitation therapies, supervision and socialization that enables frail, older people, who are in poor health and have multiple comorbidities and varying physical and mental impairments, to remain active in the community.’ Japanese long-term care system has a low eligibility threshold. (Kuzuya et al. 2012:323). |

| Norway | Senior centre | Support maintenance of physical and psychological activity, functional health, promote self-sufficiency and prevent loneliness and isolation (Boen et al. 2010, Lund and Englesrud 2008). Open to all aged ≥60 years (Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011). Although these are characterised as welfare services, they do not provide statutory care and are paid for privately; often run by small staff body and volunteers (Boen et al. 2010). |

| Singapore | Day care center | Umbrella term encompassing ‘senior care centers’, ‘day care centers (social)’, ‘senior activity centers’, day rehabilitation centres, dementia day care, psychiatric day care, hospice day care and multidisciplinary medical day care. ‘A key enabler of aging-in-place is day care centers, which are non residential facilities that support the functional and social needs of seniors during the day’ (Liu et al. 2015:e7). |

| US | Adult Day Service (ADS) centres | Umbrella term. ADSs provide support for people with functional limitations to remain in the community and reduce carer burden (Schmitt et al. 2010) using three models: - social (meals, recreational activities and some health services) - medical/health (social activities, health and therapeutic services) - specialised (care for specific groups e.g. dementia, learning disability) (National Adult Day Services Association (NADSA) 2015). |

| Adult Day Health Centre | Medical model. ‘…offer a multidisciplinary team approach that includes skilled nursing and rehabilitation therapy in addition to the social model services. In some states, ADHC services are Medicaid reimbursable because they are considered to be an alternative to institutional-based long-term care’ (Schmitt et al. 2010). | |

| Multipurpose Centre | Provide a range of social support services e.g. health, nutritional, educational and recreational activities, and promote opportunities for social interaction and involvement (Salari, Brown and Eaton 2006). | |

| Senior centre | Focus on socialisation and leisure; often volunteer run (MaloneBeach and Langeland 2011); often with a cross-generational reach; tend to be non-profit and publicly funded (Hostetler 2011). |

These four aims fall within the first two types of social care outcomes identified by research with older people and carers, namely outcomes resulting in change and outcomes for the purpose of maintenance or prevention, but do not reflect the third type, process outcomes (the way services are accessed and delivered) (Qureshi et al. 1998).

Although what a day centre offers is likely to be influenced by its aims, only a small number of studies (Kuzuya et al. 2006, Lund and Englesrud 2008, Hostetler 2011, Boen et al. 2012, Iecovich and Biderman 2013c, Wittich, Murphy and Mulrooney 2014) proffered lists or categories of activities, but not their frequency, nor details of other services available (e.g. manicures, hairdressing, laundry) and without stating whether these were led by staff or visitors, or levels of participation. One paper did not list activities but outlined building layouts (Salari, Brown and Eaton 2006).

Day centre attenders

Fewer than half of the included research papers reported their attender participant characteristics in detail. Age, gender, marital status and living arrangements were the most commonly reported characteristics followed by physical and/or mental health, education, income and ethnicity. Nothing was reported about religious affiliations, sexual orientation or gender reassignment. Although proportions varied between studies, attenders emerged as primarily women who lived alone or were widowed, divorced or single and older, without further education, with low income, comorbidities and who took multiple medications. Demand for generalist day centre places by people with learning disabilities, who highly value their specialist day centres but are expected to ‘retire’ from these on reaching 65 years (Judge et al. 2010), was predicted to increase in the future.

Varying levels of social support outside day centres were reported in five studies (Del Aguila, Cox and Lee 2006, Fulbright 2010, Iecovich and Carmel 2011, Chaichanawirote and Higgins 2013, Wittich, Murphy and Mulrooney 2014). Having an inadequate informal network was one of two factors found to contribute to the decision to apply for a day centre place (Del Aguila, Cox and Lee 2006). Caiels, Forder and Malley’s (2010) English study reported some volunteering activity (with no details) and only one attender in a Norwegian study also attended a course (unspecified) elsewhere (Lund and Engelsrud 2008). Two studies covered other formal services received (Kuzuya et al. 2006, Schmitt et al. 2010) and a third found that, for people with functional impairments, receiving Activity of Daily Living (ADL) support on attendance days was one factor that significantly improved regularity of attendance (Savard et al. 2009).

Why attend day centres?

In reporting reasons for attendance at day centres, the literature suggests prior social isolation and poor wellbeing are key. Reasons reported mainly fall under the first aim of day centres, namely providing social contact (Fulbright 2010, Pardasani 2010, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011, Iecovich and Biderman 2013a, Marhankova 2014, McHugh et al. 2015) and preventive services (Iecovich and Biderman 2013a) or activities (Lund and Engelsrud 2008, Fulbright 2010, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011). Two papers reported reasons addressing other aims: improving or maintaining health (Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011, Iecovich and Biderman 2013a) and perceived support for family carers (Iecovich and Biderman 2013a). People also attended with an aim of introducing structure to their lives after retirement or losing a spouse (Lund and Englesrud 2008) or because they felt that day centres met needs, without specifying the nature of these (Iecovich and Biderman 2013a, Marhankova 2014).

Who benefits most?

A small amount of literature concluded that certain attenders may experience better outcomes than others. These were people living alone (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010, Fawcett 2014), the functionally (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010) or mobility impaired (Fawcett 2014), people with a low income (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010) or who were younger (≤70) (Fawcett 2014). Caiels, Forder and Malley noted ‘a diminishing effect size with greater need, meaning that a needs-based rule which only prioritised high needs potential recipients would generally not produce the greatest wellbeing improvement in the population for a given budget’ (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010: 67). Frequent (Kuzuya et al. 2006, Bilotta et al. 2010, Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010) or longer (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, Fawcett 2014) attendance and starting a new activity (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005) and participating in and enjoying activities (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010) also contributed to better outcomes.

Perceptions of day centres

Professionals working in health and social care

While day centres occupy a recognised place in the care continuum in some countries (e.g. Boen et al. 2010, Pardasani 2010, Kuzuya et al. 2012, Liu et al. 2015), the literature indicates this may not be the case in England. Recognition, however, did not mean that different professionals universally recommended them (Kane, Bershadsky and Bershadsky 2006). In England, they were absent from lists of preventive services commissioned by some local authorities (Miller et al. 2014) and were not among services prioritised most highly by a small group of nurses (Clough et al. 2007). Some local authority staff believed that demand had declined for two possible reasons: lack of a personalised service in a day centre or older people preferring other services or options (Brookes et al. 2013).

Day centre managers

According to day centre managers and senior staff in the US, day centres suffer from an image problem (Hostetler 2011) and are influenced by terminology (Sanders, Saunders and Kintzle 2009). They felt that the term ‘day services’ was preferred by older people over ‘day care’ which was likely to be associated with images of disabled and very old attenders and, consequently, stigmatised. Managers also thought that other professionals lacked understanding of the value of day centres (Sanders, Saunders and Kintzle 2009).

Older people: attenders and non-attenders

Day centres are perceived by some attenders as undesirable welfare services for people who are old, isolated, ill or miserable (Lund and Englesrud 2008, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011, Iecovich and Biderman 2013a). Among some, attitudes became more positive once attending (Sale 2005, Lund and Englesrud 2008).

It is possible that negative perceptions may be reflected in reasons given for not attending day centres. These included preferring to be at home, lack of interest or need, difficulty seeing other users with dementia or disability, a view that activities were not of interest or culturally inappropriate, and that centres offered insufficient opportunities to contribute by volunteering (Pardasani 2010, Iecovich and Biderman 2013a, Ipsos MORI 2014).

Considering future attenders, US ‘baby boomers’ (younger older people) appeared to feel positive about day centres, viewing them as social and activity centres and as offering carer support (MaloneBeach and Langeland 2011). Potential challenges in attracting future cohorts in Canada were acknowledged, but a literature review concluded that day centres ‘are already a traditional part of our culture and are widely recognized and respected’ (Fitzpatrick and McCabe 2008: 211).

Mapping outcomes of attendance and interventions against day centre aims

Four aims of day centres were identified in the literature: providing social and preventive services, supporting continued independence of attenders, supporting attenders’ health and daily living needs and enabling family carers to have a break and/or continue with employment. Bearing in mind the breadth of what is covered by the term ‘prevention’ (Wistow, Waddington and Godfrey 2003), the first three aims overlap, and findings have been divided in this section as follows. The prevention of decline and possible avoidance of more expensive services (except care homes) are covered under ‘providing social and preventive services’. ‘Supporting independence’ encompasses literature concerning the direct supporting of independence, including remaining at home and delaying a move to long-term residential care. Literature linked with existing health conditions appears next and then carer support. Judgements were necessary on occasion. For example, meals may be preventive (e.g. of loneliness or malnutrition) or may be classified as supporting people’s daily living needs. Outcomes of interventions undertaken in day centres are presented separately from outcomes of attendance alone. Finally, process outcomes for attenders are summarised.

Providing social and preventive services

Attendance

Positive psychosocial outcomes of day centre attendance were the most documented, mainly by non-UK literature and one large English study, testing a validated measure, which found that day centre attendance increased overall quality of life (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010).

Social participation was an important benefit (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006, Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010, Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, Fulbright 2010, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011, Fawcett 2014). It helped people gain a better perspective of their own abilities (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010), feel more stimulated, confident and content (Fawcett 2014). It appeared to encourage increased activity outside day centres with new day centre friends (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006) or existing networks (Fawcett 2014). Having supportive networks increased the likelihood of activity participation (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006) which also contributed to improved perceived wellbeing (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010). Intergenerational contact improved wellbeing and activity (Weintraub and Killian 2007, 2009). Day centres were also likened to second homes (Lund and Englesrud 2008, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011) and new social connections substituted for family (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006, Weintraub and Killian 2007).

Attendance improved mental health and quality of life or prevented its decline, as evidenced by reductions in depression and/or anxiety (Bilotta et al. 2010, Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, Fulbright 2010, Santangelo et al. 2012, Fawcett 2014), improved resilience scores (Fawcett 2014), significantly improved life satisfaction (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006), and, compared with non-attenders, higher emotional, physical and overall quality of life (Iecovich and Biderman 2013b), self-esteem and sense of control (Ron 2007). Reflecting a finding that subjective variables (e.g. self-rated health) were more likely to explain higher quality of life than objective ones (e.g. morbidity, attendance frequency), higher wellbeing was significantly associated with social participation and feeling that attendance supported carer wellbeing (Iecovich and Biderman 2013b). Also impacting on wellbeing was the ability to access other services (e.g. occupational therapy) (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010). Prevention of decline was evidenced by maintenance of general wellbeing (Wittich, Murphy and Mulrooney 2014) and similar levels of loneliness in frail attenders and non-attenders were interpreted as indicating the probable positive impact of attendance given group differences (Iecovich and Biderman 2012).

Positive outcomes are said to be partly attributable to the group nature of the service (Ron 2007, Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, Fitzpatrick 2010) which provides structure (Ron 2007), enables involvement (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006, Ron 2007, Lund and Englesrud 2008, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011, Iecovich and Biderman 2013a, Fawcett 2014) and ‘volunteering’ (undefined) (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005, Lund and Englesrud 2008). It is possible that the congregate environment may be one reason behind enjoying attending despite this not changing some people’s lives (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010). A small English study reported attenders felt useful by helping clearing tables after meals and energised by being around people, and they enjoyed telling family about their day’s activities (Ipsos MORI 2014). Staff members were felt to play a role in meeting attenders’ emotional needs (Weintraub and Killian 2007) and raising their self-esteem (Ron 2007). Informal staff monitoring of health may have contributed to lower mortality in attenders than non-attenders (Kuzuya et al. 2006).

Attendance at two day centres that integrated health and social care prevented decline, with a bio-psychosocial model of support resulting in attenders faring significantly better than a control group in disability and functioning domains of getting around, getting along with people, life activities and participation (Shahbazi et al. 2016). Individually-tailored therapeutic packages, however, had less impact, resulting in small improvements in physical wellbeing in attenders compared with non-attenders; impact on functional ability was very limited and psychological wellbeing did not change (Murphy et al. 2017).

Interventions

Seven interventions reportedly prevented decline of or improved mental, physical and cognitive health and aspects of wellbeing, and increased social networks (Mathieu 2008, Pitkala et al. 2009, Dabelko-Schoeny, Anderson and Spinks 2010, Fitzpatrick 2010, Pitkala et al. 2011, Boen et al. 2012, Ganz and Jacobs 2014, Gallagher 2016). However, outcomes of interventions were not positive without exception (see Table 4). One, a discussion group, resulted in the unexpected outcome of improved relationships between attenders, and between attenders and staff.

Table 4. Interventions in day centres and their outcomes.

| Author | Outcomes relevant to aim | |

|---|---|---|

| Providing social and preventive services | ||

| Humour-based programme (Mathieu 2008) | Significantly improved life satisfaction New social networks that extended beyond day centres. |

|

| Humour-based programme (Ganz and Jacobs 2014) | Significantly lowered anxiety and depression Significantly improved psychological wellbeing. BUT Did not impact on general health, health-related quality of life and psychological distress. |

|

| Transport, exercise and self-help programme (Boen et al. 2012) | Small improvements in levels of depression - although higher with mild depression. Concluded that model tested was not the most appropriate. New social networks that extended beyond day centres. BUT Men did not report new friendships whereas 40% of women did. |

|

| Organised volunteering (Dabelko-Schoeny, Anderson and Spinks 2010) | Improved self-perceived health Improved feelings of purpose and self-esteem. BUT After intervention finished, participants’ self-esteem and self-perceived health significantly lowered, although this remained above baseline measurements. |

|

| Psychosocial group work (Pitkala et al. 2009, 2011) | Lowered mortality and reduced use of health services over a two year follow-up period (Pitkala et al. 2009). Cognition improvements were experienced by lonely older people; these remained significantly improved after one year (Pitkala et al. 2011). |

|

| Brain fitness activities of the type that may ordinarily take place in day centres (Fitzpatrick 2010) | Improved self-perceived health. Improved general wellbeing, perceptions of happiness and living an interesting life. |

|

| Discussion groups to promote social engagement and learning (Gallagher 2016) | Improved social engagement, mutual understanding and tolerance and intellectual stimulation. Improved relationships with staff and better staff understanding of attenders. |

|

| Health outreach programme (Vogel et al. 2007) | Addressed individual need and targets for both partners (housing provider and public health). | |

| Hearing screening for people with sight loss (Wittich, Murphy and Mulrooney 2014) | Improved links with a co-located support programme for hearing impaired people. | |

| Supporting independence | ||

| Evidence-based, moderate-intensity weight-bearing exercise programme (Henwood, Wooding and de Souza 2013) | Significantly improved lower body strength, agility, balance, walking speed and right hand grip in older people needing help with one or more Activities of Daily Living (ADLs). | |

| Core stability and flexibility exercise programme (Battaglia et al. 2014) | Improved spinal ranges of motion. BUT sacral/hip and thoracic flexibility, improvements in the lumbar area were not significant. |

|

| Walking with poles at day centres (Ota et al. 2014) | Significant improvements to health-related quality of life associated with activity and function and to some aspects of posture. Maintained mobility. BUT fitness and physical function (except mobility (measured by Timed Up And Go test) did not change |

|

| Programme of education-focused falls prevention (Yamada and Demura 2014) | Improved mobility. | |

| Supporting health and daily living needs | ||

| Author | Outcomes relevant to aim | Outcomes relevant to other aims |

| Blood pressure monitoring by trained volunteers (Truncali et al. 2010) | Reduced blood pressure | |

| Blood pressure monitoring by nurses via telehealth kiosks (Resnick et al. 2012) | Reduced blood pressure | |

| Self-management education (Dickson et al. 2014) | Significantly improved knowledge of heart failure, management and maintenance among people diagnosed with heart failure. | |

| Self-management education (Frosch et al. 2010) | Significantly improved self-rated ability to take preventive actions, manage symptoms, find and use appropriate medical care and make care decisions with health professionals. Improved physical activity and performance. |

Improved mental health-related quality of life |

| Behavioural intervention to increase walking and reduce urinary incontinence (UI) (Morrisroe et al. 2014) | Decreased incidence of UI in sedentary older people who improved their balance, gait strength and endurance by walking more. | Improved physical activity and performance |

| Pelvic floor muscle training (Kegel exercises) to reduce UI with supportive coaching (Santacreu and Fernandez-Ballesteros 2011) | Significantly decreased UI in women. | |

| Medication reviews by pharmacy students (McGivney et al. 2011) | Resolution of many medication-related problems. Better medication use. |

|

| Lifestyle modification programme delivered by trained lay people (West et al. 2011) | Clinically significant weight loss in an obese people. | |

| Programme of low-impact exercise, nutrition education and weight management for people with multiple chronic conditions (Kogan et al. 2013) | Significant improvements to fitness, daily walking distance and hours of weekly exercise, and body measurements. | Significant reductions in depression |

Two further papers exemplified joint working between services and sectors. A programme of health outreach offering flexible service choices for people in public housing addressed individual need and targets for both organisational partners, a housing provider and public health services (Vogel et al. 2007). A newly introduced hearing screening service improved links with a co-located support programme for hearing impaired people (Wittich, Murphy and Mulrooney 2014).

Finally, day centres were argued to be suitable venues for health promotion interventions (Boen et al. 2012) and well-placed to identify hearing and vision impairments, screen for depression, and perhaps offer falls prevention programmes and depression treatment in collaboration with primary care or community health centres (Cabin and Fahs 2011).

Supporting independence

Attendance

Apart from two studies linking day centre attendance with remaining at home for longer, little was found about the contribution of day centre attendance to supporting independence. The first of these linked consistent day centre attendance with delaying a care home move in functionally and/or cognitively impaired people over a four-year period, with instututionalisation (move to long-term care) risk significantly decreasing among those attending more frequently or for longer (Kelly et al. 2016). The second identified that a combination of day centre attendance and personal care at home supported functionally limited people to remain at home (Chen and Berkowitz 2012). Other studies have reported that attendance supported people with sight loss to remain at home following participation in rehabilitative services (Wittich, Murphy and Mulrooney 2014) and contributed to the reduction of socio-health-related hospital admissions and delaying moves to long-term care facilities (Fawcett 2014) and, potentially, makes practical support available.

With respect to attenders’ own perceptions, some felt that attendance helped them remain at home (Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011). Socially integrated women living alone attributed this partly to participation in health promotion activities (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006). Practical support (e.g. transport, shopping) was perceived to be available at times of need from ‘close friendships’ (undefined) newly developed at day centres (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006). Home maintenance was linked with attendance in England; home cleanliness and comfort were the second highest domain of benefit of attendance, possibly ‘due to reducing the tasks associated with food preparation and personal cleanliness that would otherwise take place at home’ (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010: 37).

Interventions

Four interventions indicate that day centres may play a role in supporting people to age in place (see Table 4). They maintained or improved physical function and quality of life, impacting on their attenders’ potential ability to remain independent (Henwood, Wooding and de Souza 2013, Battaglia et al. 2014, Ota et al. 2014, Yamada and Demura 2014). These findings are particularly pertinent since people may initially access day centres when their functional capacity and support network have reduced (Del Aguila, Cox and Lee 2006). Thus, day centres may replace rather than supplement informal support.

Supporting attenders’ health and daily living needs

Attendance

Findings of seven studies addressing impact of attendance on physical health and functional needs were mixed. Increased exercise, improved eating habits (Aday, Kehoe and Farney 2006), significantly less restricted physical and emotional health, compared with non-attenders, despite no significant change in physical, social and mental health-related quality of life (Schmitt et al. 2010) and physical health improvements (Fawcett 2014) were reported. Attenders felt that attendance improved and maintained their health (Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011). Surprisingly, social support from friendship did not significantly impact on health (Fitzpatrick et al. 2005). Two studies found that it was other factors, not day centre attendance, which impacted on outcomes; these were morbidity (Iecovich and Biderman 2013c) and older age (Ishibashi and Ikegami 2010).

Interventions

Nine interventions successfully addressed the management of existing conditions (Frosch et al. 2010, Truncali et al. 2010, McGivney et al. 2011, Santacreu and Fernandez-Ballesteros 2011, Resnick et al. 2012, Dickson et al. 2014, Morrisroe et al. 2014) or health promotion and improvement (West et al. 2011, Kogan et al. 2013), pointing to the suitability of day centres as venues for such interventions (see Table 4). Reportedly, but without evidence of outcomes, activities to support health and mobility have been undertaken by pharmacists at day centres for some time as their expertise puts them in a good position to support older people’s health (Wick 2012).

Additionally, a small study found that the provision of meals enhanced nutrition particularly, health professionals thought, for people lacking company or who have experienced bereavement (McHugh et al. 2015). Reflecting evidence about the value placed on eating in company (Pardasani 2010, Ingvaldsen and Balandin 2011), McHugh et al (2015) highlighted how nutritional and social support can be delivered together.

Formal relationships with health services were the subject of only two papers, one from England, suggesting that relationships may be underdeveloped. English day centres were reported to be a common venue for outreach by Community Mental Health Teams (Tucker et al. 2014) and some US day centres had developed their services strategically to remain financially stable, resulting in more cross-referrals from home health services and lower public costs (Dabelko, Koenig and Danso 2008).

Supporting family carers

Attendance

Two studies investigated outcomes for carers of attenders. One found day centre use significant in explaining the better psychological quality of life experienced by family carers of attenders compared with carers of people receiving home care (Iecovich 2008). However, overall quality of life and carer ‘burden’ were similar in the two groups. In the other, a slightly lower percentage of carers of people attending day centres and using home care reported burden, regardless of frequency and length of attendance, compared with carers of people using home care only (Kelly et al. 2016).

Day centre attenders in another study perceived that attendance improved relationships with their carers and decreased carer burden. This was because they thought their carers did not need to worry about them while they were at the day centre (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010).

Interventions

No interventions were identified that specifically supported carers of attenders, although there is potential for some of the above interventions to reduce carer burden. For example, one exercise programme in a day centre providing respite for carers resulted in functional improvements and reduced risk of falls for attenders (Henwood, Wooding and de Souza 2013), thereby potentially delaying need for support that would impact on carers.

Process outcomes for day centre attenders

Very little was identified about process outcomes. Appreciation for being offered choice, being respected and for empowerment enabled by relationships with staff was conveyed by a small number of studies (Weintraub and Killian 2007, Glendinning et al. 2008, Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010, Fawcett 2014). Better emotional support may have been more available from day centre than home care staff (Ron 2007). English studies reported attenders’ high satisfaction with their relationships with day centre workers, their behaviour and work (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010) and one concluded that ‘day centres could provide excellent quality services, with a high emphasis on process outcomes’ (Glendinning et al. 2008: 61).

The systemic purpose of day centres

Earlier sections of this article have covered purposes of day centres for older people attending them. The literature also reported outcomes for health and social care systems in two areas and joint working in the provision of interventions at day centres.

Firstly, English day centres were reported to be cost-effective by a large study which measured outcomes using a cost-utility tool (ASCOT) and then applied criteria used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to judge cost-effectiveness of health services relative to outcomes (Caiels, Forder and Malley 2010).

Secondly, interventions with significant and positive benefits for participants may have consequences for the other parts of the health and social care system, namely the potential for financial savings and by complementing the work of health professionals. Substantial annual cost savings were estimated as a result of lower use of health services following psychosocial group work (Pitkala et al. 2009) while monitoring of blood pressure at day centres was thought to have the potential to reduce cardiovascular disease and associated costs (Resnick et al. 2012). Whereas one study found that attendance alone made no impact on use of hospital and specialist health services (Iecovich and Biderman 2013c), another found that attenders spent significantly fewer days in hospital than non-attenders and had significantly shorter hospital stays, possibly due to regular contact with centres’ healthcare professionals (Kelly 2017). One may infer from the above studies that interventions in day centres may be best placed to impact on primary care services. However, costs may also be incurred by interventions involving outside professionals not usually employed by English day centres. For example, nurses, occupational therapists and physiotherapists ran Pitkala et al.’s (2009, 2011) psychosocial groups and Henwood, Wooding and de Souza’s (2013) exercise programme required staff to be trained. As for impacts on health professionals, nurses may have been able to use their time more efficiently as a result of automatic and remote monitoring of blood pressure data generated in telehealth kiosks in day centres (Resnick et al. 2012), pharmacy students undertaking medication reviews improved their professional skills and learnt about older people when encountering them in day centres (McGivney et al. 2011) and, a programme of Kegel exercises showed that information provided by GPs (family physicians) can be consolidated by expert supervision at a day centre (Santacreu and Fernandez-Ballesteros 2011).

Although interventions may be delivered by trained lay people or volunteers (West et al. 2011, Dickson et al. 2014), cooperative working with health or public health professionals in delivering interventions was also evidenced (Vogel et al. 2007, Pitkala et al. 2011, Resnick et al. 2012) which also addressed provider’s service targets (Vogel et al. 2007). The challenge of collaboration between differing organisational cultures was said to reduce with time (Vogel et al. 2007) although there may remain a risk that longer-term maintenance outcomes become over-shadowed by the change outcomes favoured by health services (Glendinning et al. 2008). For example, it may be considered more important to improve cognition or reduce blood pressure than to prevent psychological wellbeing from declining further.

Discussion

This paper adds to the existing knowledge by considering the findings of a review aiming to discover the extent of the evidence about how day centres for older people are perceived, their benefits – and whom these are for – and purpose. As a scoping review aiming to inform new empirical research, this discussion focuses on the gaps in knowledge rather than what can be learnt from the literature. It located considerable gaps in the literature. It also identified a great diversity of research, day centre types and countries of origin with distinct systems all presenting obstacles to drawing conclusions. This diversity was earlier observed by Gaugler and Zarit who stated that the ‘the literature on adult day care is diverse in terms of focus, design and client population. Therefore, deriving conclusions is difficult’ (Gaugler and Zarit 2001: 44).

Concerning the first question, this review has identified that little is known about how day centres are perceived by those who attend them, their carers and other professionals, particularly those who are commonly in contact with older people in need of care and support (e.g. general practitioners (GPs) or family physicians, nurses, social workers and occupational therapists). This is relevant to both in the English health and social care systems and beyond. The future of day centres in England may be affected by these perceptions given that local authorities have a new role in shaping the care market (HM Government 2014), and that part of commissioners’ roles is to gather evidence about user views and service options (Local Government Association and University of Birmingham 2015). This point is particularly salient given that day centre managers in the US, where - as reported in the literature - day centres are integrated within the health and care system and operational models are clear-cut, expressed concern about professionals’ understanding of day centres’ value and older people’s negative perceptions based on terminology.

In relation to the benefits of day centres, the literature has yielded evidence that day centre attendance and participation in interventions taking place within them may have a positive impact on older attenders’ mental health, social life, physical function and quality of life. Quality of life is ‘… a broad ranging concept, incorporating in a complex way a person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and relationship to salient features in the environment’ (World Health Organization 1998: 17). Day centres make available social contact, activities and interventions that improve quality of life, support the management of existing conditions and may prevent declining health and function in a congregate environment that, itself, seems to contribute to outcomes. Process outcomes for attenders have been neglected, though, and may be an important part of day centre experiences. In England, as noted above, quality of life and satisfaction of people receiving publicly-funded services and carers are monitored annually and reported in Outcomes Frameworks, but findings concerning day centres are not presented separately. Furthermore, as day centres are not regulated, the inspectorate does not include them in its ratings of care quality.

Day centres appear to be gendered services, largely used by older old women with declining health and from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Since more women than men live to older ages, when health tends to decline, and further education was uncommon in current very old cohorts, this profile is unsurprising. With the UK’s Equality Act 2010 (HM Government 2010) in mind, this review found no studies reporting attenders’ protected characteristics of religious affiliation, sexual orientation or gender reassignment, confirming Manthorpe and Moriarty’s (2014) review of UK literature from 2000-2013 which found a dearth of such data about day centre attenders, and argued that such data was needed to enable examination of barriers to service use or differing experiences, for example. These groups tend to remain invisible except in focused studies.

Important data for the contextualisation of outcomes are also missing. There was little about attenders’ lives beyond day centres, whether additional recreational activity, social support or other formal services received, or their frailty and wellbeing. Neither is it known what motivates people to start attending a day centre. Furthermore, even Caiels, Forder and Malley’s (2010) validated tool that aims to isolate the impact of a service is not able to explain what elements of day centres attenders particularly like and why, about which there is very limited literature.

With respect to their contribution to health and social care systems, day centres’ four aims, as ascribed by the literature, fall within the English government’s current policy of preventing deterioration, promoting wellbeing, enabling people to remain at home while growing older and supporting carers (HM Government 2014). Mainly in non-UK settings, day centres have demonstrated themselves to be convenient pre-existing community venues for a range of daily, short- and long-term, preventive and health-related interventions run by trained staff or volunteers, or by health or social care professionals which are accessible to relevant target groups. Interventions that were focused on change or maintenance/prevention mainly showed positive outcomes, including cost-effectiveness and potential for cost savings. Despite this evidence suggesting that day centres may make a positive contribution to health and social care systems and may play a more prominent role in the prevention of ill-being, the lack of literature focusing on day centres’ role as preventive services and any current relationships with health services suggests this may not be recognised. This includes their role as services that support older people to remain at home. Furthermore, the lack of literature about perceptions of professionals working in health or social care about day centres perhaps reflects an underlying perception that day centres do not align with current local or national priorities.

Conspicuously absent is evidence concerning family carers and volunteers with reference to all three review questions. Many English day centres are run within the voluntary or not-for-profit sector and are ‘staffed’ by volunteers (Hussein and Manthorpe 2014). Furthermore, few studies have included paid day centre staff, thus neglecting the views and experiences of those providing care and support to older attenders.

Policy-related theory was also notably lacking, with studies concerning ageing in place, for example, mainly focused on preventing dependence or moves to long-term care facilities, rather than on impact on quality of life for those remaining at home.

Although the qualitative and quantitative findings in the literature complemented each other and findings were commonly in accord with earlier research findings, six points are worth highlighting with respect to the limitations of this body of literature. First, the generalisability of several studies’ findings is affected by small sample sizes, characteristics of participants who may have been recruited against specific criteria, study design or day centre model. Also, much literature originated in the US where funding systems and day centre models are often different to those operating elsewhere. Second, attrition due to health problems or caring responsibilities was, on occasion, relatively high. Although conceivable that the apparent typical profile of attenders – very old women with declining health, frailty and multiple morbidities - may be the underlying cause, this may also indicate that the studies’ requirements were too demanding or that day centres do not support wellbeing or meet expectations. Third, bias may be present as respondents may have given socially desirable answers (Dabelko-Schoeny and King 2010) especially during interviews at day centres (Iecovich and Biderman 2013b), potentially due to fear of service withdrawal. Fourth, sample sizes were wide-ranging, usually larger in secondary data analysis and quantitative studies than qualitative studies. Fifth, most outcomes measures used and data collected required expert administration, equipment, analysis and interpretation. Measures that can be administered and interpreted by staff and volunteers and are pertinent to the service being offered may be of more practical use to day centre management, operation and statutory bodies, particularly if measures correspond with centres’ overall aims. Finally, there is an imbalance in the types of day centres involved in research. Less is known about day centres whose attenders have substantial functional limitations or which may be supported by external funding (Sanders, Saunders and Kintzle 2009) than about US ‘senior centers’ targeting a more active population. Given the declining numbers of English day centres and the tightening of social care eligibility criteria for publicly funded services, it is likely that English day centre attenders may be of the former type.

Limitations of the Review

The limitations of this scoping review lie in its inclusion of only English language material. Additionally, due to the differing terminology used about day centres, some literature may not have been not identified. While literature was not ‘scored’, its limitations are acknowledged. However, a systematic approach was taken and this, together with its broad search strategy, helped to identify more literature than expected.

Conclusion

This review presents a strong argument for conducting an England-based empirical study. It confirms that day centres are under-researched as whole services, both in England and elsewhere. No interventions appear to have been tested in English day centres and English literature tends not to be directly focused on day centres similar to much of the non-UK literature. Although the lack of research about English day centres may indicate a less defined role compared with some other countries, it may also arise from the limited funding for social care research (Rainey, Woolham and Stevens 2015) or reflect the low priority given to this service model by policy-makers and researchers (Clark 2001). Notwithstanding the difficulty of making international comparisons and drawing conclusions from the the diversity of operational models, the non-UK evidence in this paper suggests that the role of day centres in England is under-developed and that there is potential for development given the mainly positive outcomes reported in the 2005-17 literature which align with current English policy themes. Day centres’ potential contribution to health and social care outcomes would benefit from further research. In the absence of national surveys or data, it will be important to establish what day centres offer, who uses them and why, and how they are perceived by their various stakeholders and potential users to contextualise their current and potential role.

Supplementary Material

Source of funding

This work was supported by The Dunhill Medical Trust (grant number: RTF59/0114). The views expressed are those of the authors only.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- ADASS. Models for Funding Allocation in Social Care. “The £ 100 Million Project”. Association of Directors of Adult Social Services; 2011. [Accessed 20 Sep 2017]. Available online at www.adass.org.uk/uploadedFiles/adass_content/publications/policy_documents/key_documents/FundingAllocationModelsNov11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- ADASS Research Group. Guidelines for People Who Want Approval for a Multi Site Social Services Research Project. Association of Directors of Adult Social Services; 2014. [Accessed 20 Sep 2017]. Available online at www.adass.org.uk/AdassMedia/stories/Guidelines%20for%20applicants%2011.1.10.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Aday RH, Kehoe GC, Farney LA. Impact of senior center friendships on aging women who live alone. Journal of Women & Aging. 2006;18(1):57–73. doi: 10.1300/J074v18n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age UK. Social care spending falls by £1.1billion. [Accessed 20 Sep 2017];2015 Available www.ageuk.org.uk/latest-news/social-care-spending-falls-by-billion/

- Al-Dosseri H, Khalil A, Matooq S, Al-Junaidi N, Aldoy G, Othman R. The Prevalence of Depression among Elderly Attending Daycare Centers. Bahrain Medical Bulletin. 2014;36(3):159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew T, Moriarty J, Levin E, Webb S. Outcome of referral to social services departments for people with cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2000;15(5):406–414. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(200005)15:5<406::aid-gps122>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audit Commission. Take Your Choice: A Commissioning Framework for Community Care. Abingdon: Audit Commission; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Audit Commission. Choosing Well: Analysing the Costs and Benefits of Choice in Local Public Services. London: Audit Commission; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M. Abandoning Care? A critical perspective on personalisation from an ethic of care. Ethics and Social Welfare. 2011;5(2):153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J. At Your Service: Navigating the Future Market in Health and Social Care. London: Demos; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Bellafiore M, Caramazza G, Paoli A, Bianco A, Palma A. Changes in spinal range of motion after a flexibility training program in elderly women. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014;9:653–660. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S59548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilotta C, Bergamaschini L, Spreafico S, Vergani C. Day care centre attendance and quality of life in depressed older adults living in the community. European Journal of Ageing. 2010;7(1):29–35. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0138-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boen H, Dalgard OS, Johansen R, Nord E. Socio-demographic, psychosocial and health characteristics of Norwegian senior centre users: A cross-sectional study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2010;38(5):508–517. doi: 10.1177/1403494810370230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boen H, Dalgard OS, Johansen R, Nord E. A randomized controlled trial of a senior centre group programme for increasing social support and preventing depression in elderly people living at home in Norway. BMC Geriatrics. 2012;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]