Abstract

Senescence of cardiomyocytes is considered a key factor for the occurrence of doxorubicin (Dox)-associated cardiomyopathy. The NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is reported to be involved in the process of cellular senescence. Furthermore, thioredoxin-interactive protein (TXNIP) is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and is considered to be a key component in the regulation of the pathogenesis of senescence. Studies have demonstrated that pretreatment with honokiol (Hnk) can alleviate Dox-induced cardiotoxicity. However, the impact of Hnk on cardiomyocyte senescence elicited by Dox and the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The present study demonstrated that Hnk was able to prevent Dox-induced senescence of H9c2 cardiomyocytes, indicated by decreased senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining, as well as decreased expression of p16INK4A and p21. Hnk also inhibited TXNIP expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in Dox-stimulated H9c2 cardiomyocytes. When TXNIP expression was enforced by adenovirus-mediated gene overexpression, the NLRP3 inflammasome was activated, which led to inhibition of the anti-inflammation and anti-senescence effects of Hnk on H9c2 cardiomyocytes under Dox treatment. Furthermore, adenovirus-mediated TXNIP-silencing inhibited the NLRP3 inflammasome. Consistently, TXNIP knockdown enhanced the anti-inflammation and anti-senescence effects of Hnk on H9c2 cardiomyocytes under Dox stimulation. In summary, Hnk was found to be effective in protecting cardio-myocytes against Dox-stimulated senescence. This protective effect was mediated via the inhibition of TXNIP expression and the subsequent suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome. These results demonstrated that Hnk may be of value as a cardioprotective drug by inhibiting cardiomyocyte senescence.

Keywords: honokiol, doxorubicin, cardiomyocyte, senescence, thioredoxin-interacting protein, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3

Introduction

Doxorubicin (Dox) is an anthracycline, which are effective anticancer drugs widely used in clinical practice (1). Despite the effectiveness of Dox against cancer, it is associated with severe dose-limiting cardiotoxicity, which typically manifests as subclinical cardiac dysfunction or clinical heart failure at the end of chemotherapy or after several years (2). This late-onset form of anthracycline cardiotoxicity is referred to as chronic and has a complex pathogenesis (3,4). Cardiomyocyte senescence has been previously suggested as a mechanism underlying Dox-induced cardiotoxicity (5), which can, at least partly, result in cardiac remodeling and dysfunction (6). Therefore, senescence is pivotal to the progression of delayed anthracy-cline cardiomyopathy in mice (7), as well as in humans (8). Accordingly, regulation of cardiomyocyte senescence may promote the development of cardioprotective strategies and reduce the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular disease in the early and late stages of cancer treatment (9). However, the clinical effectiveness of anti-senescence therapies remains poor. Therefore, investigating novel therapeutic strategies to alleviate Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence remains a major challenge.

Honokiol (Hnk) is an effective ingredient extracted from the bark of Magnolia officinalis and is widely used in Chinese medicine. In previous studies, Hnk was found to have a wide spectrum of pharmacological properties, such as antitumor (10), antibacterial (11) and antihypertensive (12). In addition, recent studies demonstrated that Hnk can protect against pressure overload-mediated cardiac hypertrophy (13), myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (14) and Dox-induced cardiomyopathy (15). Several mechanisms underlying the role of Hnk in cardioprotection have been reported, including the inhibition of oxidative stress and apoptosis (16), as well as improvement of autophagy (14) and mitochondrial function (13). In addition, a recent study revealed the association between Hnk and senescence in skin cells (17). However, to the best of our knowledge, it remains unknown whether inhibition of cardiomyocyte senescence is involved in the protective effect of Hnk on the heart. Investigating whether Hnk protects heart cells from senescence may further support the biological effects of Hnk on the heart and uncover its potential clinical applications.

Inflammasomes are multimeric complexes of innate immune receptors and their formation promotes caspase-1 activation, which subsequently results in the processing and secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 (18). A number of studies have demonstrated that the activation of the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome directly participates in the regulation of inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis in cultured cardiomyocytes (19). Recently, additional studies have demonstrated a pivotal role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in accelerating endothelial cell senescence (20,21). However, the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocyte senescence remains to be fully elucidated.

Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), also termed thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitaminD3 upregulated protein 1, belongs to the arrestin superfamily and inhibits the disulfide reductase activity of thioredoxin (22). Studies in mammals have demonstrated that TXNIP plays a key role in regulating cell growth (23), apoptosis (24), metabolism (25) and immune responses (26). Previous studies have reported that TXNIP acts as a link between redox regulation and the pathogenesis of senescence (27,28). Additionally, TXNIP may be upregulated during the process of senescence, and upregulation of TXNIP in young cells resulted in typical signs of senescence (29). Furthermore, a study demonstrated that the TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway contributes to the senescence of vascular endothelial cells (27), thus providing a novel mechanism for TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated cellular senescence. Despite increasing evidence supporting pivotal roles of TXNIP in the regulation of cardiomyocyte fatty acid oxidation (30) and apoptosis (31), further research is required to determine whether TXNIP and the NLRP3 inflammasome are involved in cardiomyocyte senescence.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the effects of Hnk on Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence, and to examine the roles of TXNIP and the NLRP3 inflammasome in Hnk-mediated inhibition of cardiomyocyte senescence.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The following materials were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.: Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), TRIzol reagent and chemiluminescence reagents. The following materials were purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology: Senescence Cells Histochemical Staining kit (cat. no. C0602), Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. C0038), RIPA lysis buffer, BCA protein assay kit and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. PrimeScript RT Master mix kit and SYBR Green Master Mixture were from Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Hnk (cat. no. HY-N0003) was obtained from MedChemExpress. Doxorubicin hydrochloride (cat. no. D1515) was from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Anti-p16INK4A (cat. no. ARG57377) was from Arigo Biolaboratories. Anti-p21 (cat. no. ab109199) was from Abcam. Anti-TXNIP (cat. no. sc-166234) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The β-tubulin antibody (cat. no. 66240-1-Ig) was from ProteinTech Group, Inc. Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were from AntGene Biotechnology Co., Ltd.

Cell culture and treatments

Experiments were performed on the rat embryonic cardiac cell line H9c2, which was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (cat. no. CRL-1446). H9c2 cardiomyocytes were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin at 37°C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2, as reported previously (32), and treated after reaching a confluence of ~80%.

Generation of recombinant adenovirus

Replication-defective recombinant adenovirus containing the entire coding sequence of TXNIP (Ad-TXNIP) was constructed with the Adenovirus Expression Vector kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). An adenovirus-only-carrying green fluorescence protein was used as a negative control (Ad-NC). To generate adenovirus expressing shRNA against TXNIP (Ad-shTXNIP), three siRNAs for rat TXNIP were designed. The one with the optimal knockdown efficiency evaluated by western blotting was selected to create shRNA and then recombined into adenoviral vectors. The target sequence was as follows: 5′-GAA GAA AGT TTC CTG CAT GTT C-3′. The negative control adenovirus was designed to express non-targeting 'universal control' shRNA (Ad-shNC). Amplification and purification of recombinant adenovirus was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Takara Bio, Inc.).

Experimental design

To investigate the protective effects of Hnk on Dox-induced senescence, H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pretreated with Hnk at a dose of 2.5 or 5.0 µM for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with or without 0.1 µM Dox for 48 h (33,34) and analyzed for each experiment. To further investigate whether the anti-senescence effects of Hnk were associated with the inhibition of TXNIP, H9c2 cells were infected with either Ad-TXNIP or Ad-shTXNIP 48 h prior to Hnk treatment under the control of Ad-NC or Ad-shNC, and subsequently incubated with or without 0.1 µM Dox for 48 h prior to analysis. Since both Hnk and Dox were dissolved in 0.1% DMSO, an equivalent amount of vehicle was added to both the control and the virus-infected cells when the experiments were conducted with drug treatments.

Cell viability assay

The cell viability was determined by the CCK-8 assay. Briefly, H9c2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1×105/ml, and 100 µl DMEM with 10% FBS was added to each well followed by incubation overnight. Following drug treatment, CCK-8 (10 µl/well) was added, and the cells were cultured for a further 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Multiscan microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cell viability for the control group was set at 100%, while the viability for the other groups was expressed as a percentage of the control group.

Assessment of senescence

To detect senescence, two different features of senescence were investigated: i) Enhanced β-galactosidase activity (SA-β-gal) associated with increased lysosomal content; and ii) expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p16INK4A and p21 (35). Staining for SA-β-gal was performed with a Senescence Cells Histochemical Staining kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), according to the manufacturer's protocols. Briefly, cultured H9c2 cardiomyocytes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and then washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature. The slides were immersed in freshly prepared SA-β-gal staining solution and incubated at 37°C without CO2 overnight. Stained sections were washed twice with PBS. Senescence was quantitated by visual inspection of blue/green stained cells with an inverted microscope (magnification ×200). In total, >6 observations were included in each group.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was prepared with RIPA lysis buffer at 4°C for 30 min and quantified using a BCA kit. Equal amounts of protein (60 µg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked in 5% milk diluted with TBS/0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) buffer for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with the appropriate primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were as follows: Anti-β tubulin (1:1,000), anti-TXNIP (1:100); anti-p16INK4A (1:1,000) and anti-p21 (1:1,000). The PVDF membranes were washed three times with TBST buffer and then incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 2 h. After washing three times, the bands were evaluated with a chemiluminescence detection system.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total mRNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent. Equal amounts of mRNA (1 µg) were reversed-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). The reverse transcription conditions were as follows: 37°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 sec. Subsequently, cDNA was used for qPCR with SYBR Green Master Mixture (Takara Bio, Inc.) on the ABI StepOnePlus RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 15 sec. qPCR was performed with three replicates of each sample. The β-actin housekeeping gene was used as a control. The relative expression quantity was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (36). The primers were as follows: β-actin forward, 5′-GGA GAT TAC TGC CCT GGC TCC TA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GAC TCA TCG TAC TCC TGC TTG CTG-3′; TXNIP forward, 5′-TAG TGT CCC TGG CTC CAA GAA A-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGA TGT TTA GGT CTA TCC AGC TCA T-3′; NLRP3 forward, 5′-CCA GGA GTT CTT TGC GGC TA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCC TTT TTC GAA CTT GCC GT-3′; caspase 1 forward, 5′-AAA CTG AAC AAA GAA GGT GGC G-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCA AGA CGT GTA CGA GTG GGT G-3′; and IL-1β forward, 5′-GAC AGA ACA TAA GCC AAC AAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTC AAC TAT GTC CCG ACC ATT-3′.

Statistical analysis

The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences in the data were analyzed by an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test for two groups or one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman-Keuls test for multiple groups. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Hnk protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes against Dox-induced senescence

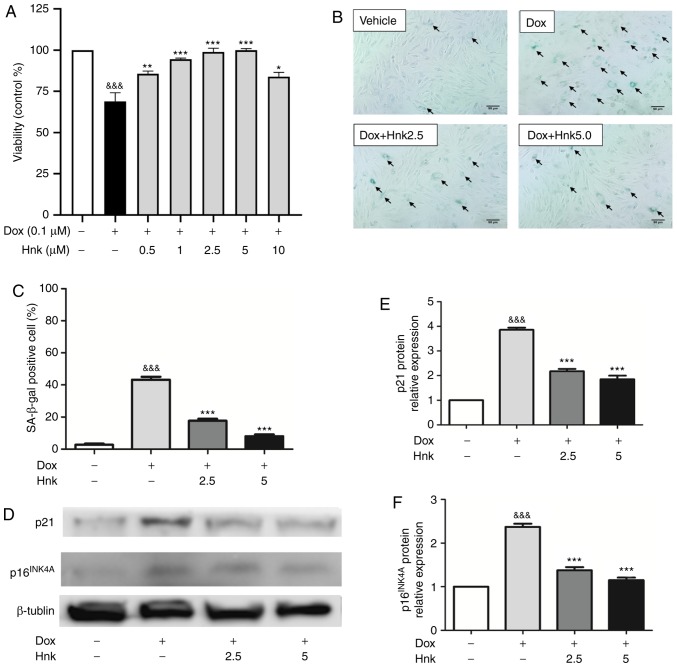

According to previous research (37), the present study selected 0.1 µM as the most suitable concentration to induce senescence of H9C2 cardiomyocytes. Dose-response experiments by CCK-8 assay were then performed to identify the optimal concentration of Hnk for the following experiments. It was observed that Hnk suppressed Dox (0.1 µM)-induced reductions in cell viability, with maximum inhibition observed when Hnk was used at 2.5 and 5 µM (Fig. 1A). Therefore, 2.5 and 5 µM were selected to study the effect of Hnk on aging. The 48-h treatment of H9c2 cells with Dox significantly increased the percentage of senescent cells, as assessed by SA-β-gal staining, while this effect was significantly reversed by Hnk treatment at both 2.5 and 5.0 µM (Fig. 1B and C). In addition, p16INK4A and p21 protein expression levels were increased in Dox-treated H9c2 cardiomyocytes compared with the vehicle group, whereas Hnk pretreatment antagonized this effect elicited by Dox (Fig. 1D-F). These results demonstrated for the first time that Hnk can protect H9c2 cardiomyocytes against Dox-induced senescence.

Figure 1.

Honokiol (Hnk) protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes against Dox-induced senescence. (A) H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pretreated with different concentrations of Hnk (0.5-10 µM) for 24 h prior to Dox (0.1 µM) exposure for 48 h, which was followed by a CCK-8 assay to evaluate cell viability. (B) Cultured H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pretreated with Hnk (0, 2.5 or 5 µM), followed by treatment with Dox (0.1 µM) for 48 h. Representative images of the co-staining for SA-β-gal-positive cells (blue; arrows). Magnification ×200. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Percentage of SA-β-gal-positive H9c2 cells. (D) Detection of p16INK4A and p21 protein levels. (E and F) Quantification of p16INK4A and p21 protein levels. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. &&&P<0.001 vs. vehicle group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. Dox group. SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; Dox, doxorubicin; Hnk2.5, honokiol 2.5 µM; Hnk5.0, honokiol 5 µM.

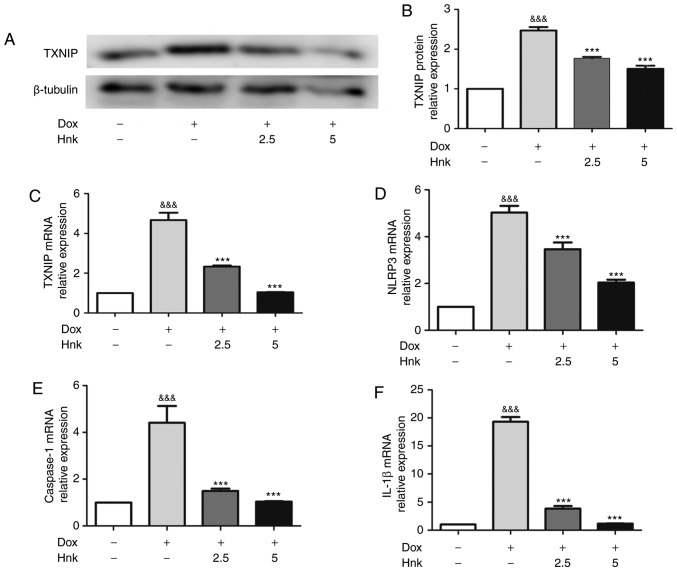

Hnk inhibits Dox-induced TXNIP expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in H9c2 cardiomyocytes

TXNIP is a recognized activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome (38). In the present study, the protein and mRNA levels of TXNIP were found to be increased significantly in Dox-treated H9c2 cardiomyocytes compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 2A-C). Furthermore, Hnk-pretreatment at both 2.5 and 5.0 µM in cultured H9c2 cells significantly downregulated the expression of TXNIP compared with the Dox group (Fig. 2A-C). As a key modulator of senescence, the NLRP3 inflammasome was analyzed at the mRNA level in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Dox-stimulated H9c2 cardiomyocytes exhibited higher mRNA levels of NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 2D-F). Consistently, cells pretreated with 2.5 and 5.0 µM exhibited markedly downregulated mRNA levels of NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 2D-F). These results indicated that Hnk was able to inhibit TXNIP expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in Dox-treated H9c2 cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2.

Honokiol (Hnk) inhibits Dox-induced TXNIP expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. (A and B) Detection of TXNIP protein levels after no treatment or exposure to Dox with or without prior incubation with Hnk, and quantitative analysis. (C-F) Detection of relative TXNIP, NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β mRNA levels after no treatment or exposure to Dox with or without prior incubation with Hnk. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. &&&P<0.001 vs. vehicle group; ***P<0.001 vs. Dox group. SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; Dox, doxorubicin; Hnk2.5, honokiol 2.5 µM; Hnk5.0, honokiol 5 µM; TXNIP, thioredoxin-interacting protein; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; IL, interleukin.

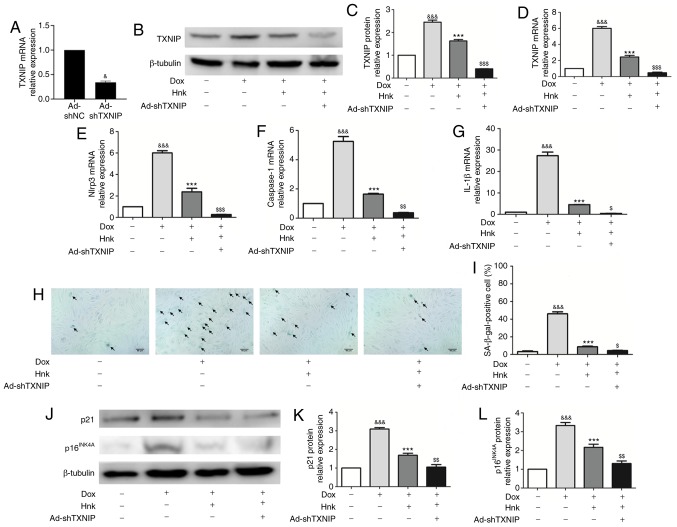

TXNIP gene silencing enhances the effect of Hnk treatment on Dox-induced senescence in H9c2 cardiomyocytes

To determine whether TXNIP is involved in the protective effect of Hnk on H9c2 cardiomyocytes against Dox-induced senescence, TXNIP expression was knocked down by adenovirus-mediated gene silencing (Fig. 3A). The Hnk + Dox + Ad-shTXNIP group displayed further reduced expression of TXNIP compared with the Hnk + Dox group (Fig. 3B-D). The inhibitory effect of Hnk on Dox-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation was enhanced when H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pre-infected with Ad-shTXNIP under the control of Ad-shNC (Fig. 3E-G). Furthermore, SA-β-gal staining was performed to detect the senescence of H9c2 cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3H). Pre-infecting H9c2 cells with Ad-shTXNIP led to a further reduction in Dox-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte senescence compared with Hnk treatment alone (Fig. 3I). In addition, western blotting was performed to detect the protein expression levels of p16INK4A and p21. Accordingly, Hnk decreased the expression levels of p16INK4A and p21, which were augmented by pre-infecting H9c2 cells with Ad-shTXNIP (Fig. 3J-L). In summary, these results demonstrated that TXNIP silencing significantly enhanced the effect of Hnk treatment on Dox-induced senescence of H9c2 cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3.

TXNIP gene silencing enhances the effect of honokiol (Hnk) treatment on Dox-induced senescence in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Cultured H9c2 cardio-myocytes were infected with Ad-shNC or Ad-shTXNIP for 48 h, followed by treatment with Hnk (5 µM) for 24 h, and then exposure to Dox (0.1 µM) for 48 h. (A) mRNA levels of TXNIP in H9c2 cells infected with TXNIP knockdown adenovirus. (B and C) Detection of TXNIP protein levels and quantitative analysis. (D-G) Detection of relative TXNIP, NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β mRNA levels. (H) Representative images of the co-staining for SA-β-gal-positive cells (blue; black arrows). Magnification ×200. Scale bar, 50 µm. (I) Percentage of SA-β-gal-positive H9c2 cells. (J) Detection of p16INK4A and p21 protein levels. (K and L) Quantification of p21 and p16INK4A protein levels. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. &P<0.05, &&&P<0.001 vs. vehicle group. ***P<0.001 vs. Dox group. $P<0.05, $$P<0.01, $$$P<0.001 vs. Dox + Hnk group. Ad, adenovirus; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; Dox, doxorubicin; Hnk, honokiol 5 µM; TXNIP, thioredoxin-interacting protein; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; IL, interleukin.

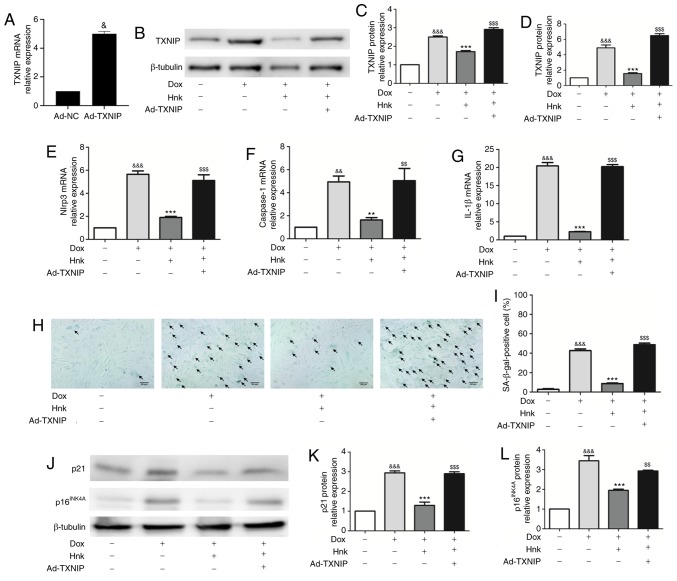

TXNIP overexpression abrogates the effect of Hnk treatment on Dox-induced senescence of H9c2 cardiomyocytes

To determine whether TXNIP mediates the protective effect of Hnk against Dox-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte senescence, TXNIP expression was upregulated by adenovirus-mediated gene overexpression (Fig. 4A). Ad-TXNIP partially reversed the inhibitory effect of Hnk on TXNIP expression (Fig. 4B-D). Indeed, the inhibitory effect of Hnk on Dox-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation was lost when H9c2 cardiomyocytes were pre-infected with Ad-TXNIP (Fig. 4E-G). Furthermore, SA-β-gal staining was performed to detect the cardiomyocyte senescence (Fig. 4H). Pre-infecting H9c2 cells with Ad-TXNIP abrogated the reduction in Dox-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte senescence attained by Hnk (Fig. 4I). In addition, Hnk almost normalized the expression levels of p16INK4A and p21, and this effect was abolished by pre-infecting H9c2 cells with Ad-TXNIP (Fig. 4J-L). Collectively, these data suggest that Hnk reverses Dox-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte senescence in a TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome dependent-manner.

Figure 4.

TXNIP overexpression abrogates the effect of honokiol (Hnk) treatment on Dox-induced senescence in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Cultured H9c2 cardiomyocytes were transfected with Ad-NC or Ad-TXNIP for 48 h, followed by treatment with Hnk (5 µM) for 24 h and subsequent exposure to Dox (0.1 µM) for 48 h. (A) mRNA levels of TXNIP in H9c2 cells infected with TXNIP overexpression adenovirus. (B and C) Detection of TXNIP protein levels and quantitative analysis. (D-G) Detection of relative TXNIP, NLRP3, caspase-1 and IL-1β mRNA levels. (H) Representative images of co-staining for SA-β-gal-positive cells (blue; arrows). Magnification ×200. Scale bars, 50 µm. (I) Percentage of SA-β-gal-positive H9c2 cells. (J) Detection of p16INK4A and p21 protein levels. (K and L) Quantification of p21 and p16INK4A protein levels. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. &P<0.05, &&P<0.01, &&&P<0.001 vs. vehicle group; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. Dox group; $$P<0.01, $$$P<0.001 vs. Dox + Hnk group. Ad, adenovirus; SA-β-gal, senescence-associated β-galactosidase; Dox, doxorubicin; Hnk, honokiol 5 µM; TXNIP, thioredoxin-interacting protein; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; IL, interleukin.

Discussion

Dox is an anthracycline that is effective against a wide range of tumors (1). Despite its beneficial effects against cancer, the clinical application of Dox is associated with severe cardiotoxicity (2). Dox induces a senescent-like phenotype in cardiomyocytes, with an abnormal pattern of troponin phosphorylation that may result in inefficient cardiac contraction (5). Senescence of cardiac cells has been identified to be crucial for the development of anthracycline-related cardiomyopathy (39). Consistent with these previous findings, the data in the present study suggest that Dox-induced cytotoxicity is mediated by the development of cellular senescence, which is accompanied by increased expression of senescence-related genes and SA-β-gal activity. Therefore, it is of great interest to identify effective therapies that inhibit cardiomyocyte senescence in order to prevent Dox-induced cardiotoxicity.

Hnk is a bioactive natural compound obtained from the genus Magnolia. Hnk has been reported to possess diverse biological properties, including antiarrhythmic, antihy-pertensive and anticancer properties, without appreciable toxicity (12,40,41). It has been demonstrated that Hnk acts as an anti-inflammatory agent by blocking the classical nuclear factor-κB pathway (42). Due to its prominent anti-inflammatory properties, there has been increasing attention on its favorable effects on cardiac performance. Tan et al (14) demonstrated that Hnk post-treatment alleviated myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing autophagic flux and reducing intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Furthermore, Pillai et al (13) suggested that Hnk blocked and reversed cardiac hypertrophy in mice by activating mitochondrial sirtuin 3. Although Huang et al (15) demonstrated that Hnk pretreatment could reduce cardiac damage by improving mitochondrial function in Dox-treated mouse hearts, the effects and the underlying mechanisms of Hnk in Dox cardiomyopathy remain to be fully elucidated. The present study confirmed that Hnk was able to attenuate Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence, as indicated by the significantly decreased number of SA-β-gal-positive cells, as well as decreased expression levels of p16INK4A and p21. This new evidence supports the previous research demonstrating that Hnk protected Dox-treated mice against cardiotoxicity. Based on these results, Hnk may be of value for suppressing the pathogenesis of Dox-induced cardiomyopathy via modulating cardiac senescence. However, detailed information regarding the precise mechanism underlying the protective effect of Hnk against Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence remains to be clearly determined.

Subsequently, the present study focused on elucidating how Hnk exerts its protective effects on cardiomyocytes subjected to Dox stimulation. A recent study reported that Hnk was able to inhibit the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in nucleus pulposus cells (43). However, to the best of our knowledge, it is not clear whether Hnk affects the NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway in cardiomyocyte senescence. The presence of low-grade inflammation is considered a definitive characteristic of senescence progression (44). In addition, this chronic pro-inflammatory state can aggravate cell senescence (45). During the process of endothelial cell senescence, the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated, which leads to the production of cytokines, such as IL-1β, thereby activating the senescent signaling pathway and leading to cellular senescence (20,46). Consistent with these findings, the present study observed activated NLRP3 inflammasome and increased expression of IL-1β. Therefore, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome may be involved in promoting Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence. Notably, Hnk successfully inhibited NLRP3 inflammasome activation and decreased the expression of IL-1β in Dox-treated cardiomyocytes. Taken together, these results indicate that Hnk is a novel antagonist of the NLRP3 inflammasome in Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence.

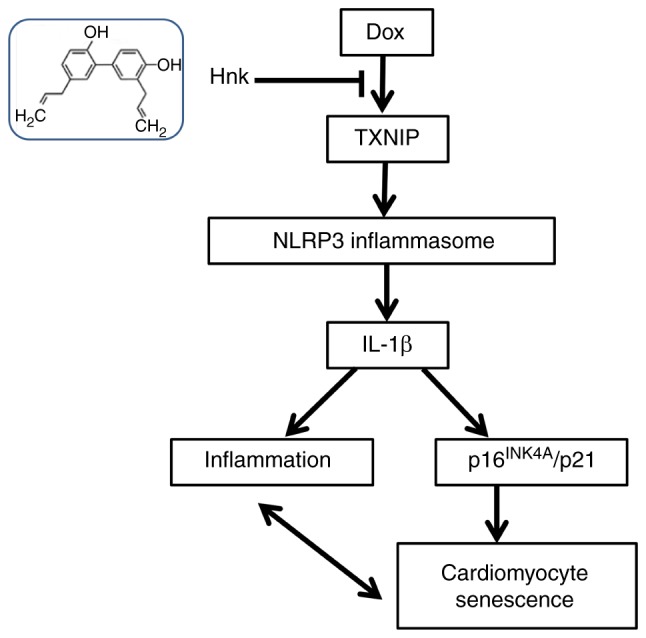

TXNIP, an endogenous inhibitor of thioredoxin, suppresses the ROS scavenging function of thioredoxin, which leads to cellular oxidative stress (22). A previous study demonstrated that TXNIP overexpression switches the function of TXNIP from a thioredoxin repressor to a NLRP3 inflammasome activator under hyperglycemic conditions (47). Furthermore, TXNIP was confirmed to directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote the release of IL-1β upon oxidative stress (48). However, the effects of TXINP on Hnk-mediated inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome in Dox-induced cardio-myocyte senescence are not well understood. In the present study, the expression of TXNIP was significantly upregulated by Dox stimulation, whereas Hnk pretreatment successfully inhibited the upregulation of TXNIP induced by Dox in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, silencing of TXNIP resulted in enhanced inhibitory effects of Hnk on Dox-induced cardio-myocyte senescence, while TXNIP overexpression abrogated the inhibitory effect of Hnk on Dox-induced senescence of cardiomyocytes, indicating that TXNIP functions as a checkpoint in the protective effects of Hnk against Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence. Based on these results, it may be concluded that Hnk prevents cardiomyocyte senescence depending on reduced TXNIP expression and the subsequent attenuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The proposed regulatory pathway of Hnk is presented in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

Proposed action pathway through which Hnk protects cardio-myocytes against Dox-induced senescence. In response to Dox stimulation, TXNIP induces NLRP3 activation, which promotes IL-1β expression by cleavage of caspase-1. The increased IL-1β expression is necessary for inflammation and senescence in the cardiomyocytes. Hnk suppresses cardiomyocyte senescence via regulation of TXNIP and effectively inhibits IL-1β induction by blocking NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. The resultant inhibition of inflammation and protection of cells from senescence leads to the amelioration of cardiac dysfunction. Dox, doxorubicin; Hnk, honokiol; TXNIP, thioredoxin-interacting protein; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3; IL, interleukin.

In summary, the present study revealed that Hnk, a major active molecule in the traditional Chinese medicine Hou Po, effectively prevented Dox-induced cardiomyocyte senescence. This cytoprotective effect was demonstrated to occur via the inhibition of TXNIP and the subsequent suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome. The understanding of the mechanism underlying this effect may support the further development of Hnk as a potential cardioprotective drug through inhibition of cardiomyocyte senescence.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant no. 8157051059), the National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81601217) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (grant no. 2017CFB627).

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed datasets generated during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

PPH designed and performed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. JF was involved in conducting the experiments, analyzing the data and writing the manuscript. LHL contributed to the writing of the manuscript and data analysis. KFW and HXL were involved in conducting the study. BMQ contributed to data analysis and interpretation. BLQ and YL conceived the study, participated in its design and helped draft the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments were approved by the Ethics committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Octavia Y, Tocchetti CG, Gabrielson KL, Janssens S, Crijns HJ, Moens AL. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1213–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeh ET, Bickford CL. Cardiovascular complications of cancer therapy: Incidence, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2231–2247. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn VS, Lenihan DJ, Ky B. Cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity: Basic mechanisms and potential cardioprotective therapies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000665. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tocchetti CG, Carpi A, Coppola C, Quintavalle C, Rea D, Campesan M, Arcari A, Piscopo G, Cipresso C, Monti MG, et al. Ranolazine protects from doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:358–366. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maejima Y, Adachi S, Ito H, Hirao K, Isobe M. Induction of premature senescence in cardiomyocytes by doxorubicin as a novel mechanism of myocardial damage. Aging Cell. 2008;7:125–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun R, Zhu B, Xiong K, Sun Y, Shi D, Chen L, Zhang Y, Li Z, Xue L. Senescence as a novel mechanism involved in β-adrenergic receptor mediated cardiac hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Zhang X, Ramil JM, Rikka S, Kim L, Lee Y, Gude NA, Thistlethwaite PA, Sussman MA, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Juvenile exposure to anthracyclines impairs cardiac progenitor cell function and vascularization resulting in greater susceptibility to stress-induced myocardial injury in adult mice. Circulation. 2010;121:675–683. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.902221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piegari E, De Angelis A, Cappetta D, Russo R, Esposito G, Costantino S, Graiani G, Frati C, Prezioso L, Berrino L, et al. Doxorubicin induces senescence and impairs function of human cardiac progenitor cells. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:334. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baar MP, Brandt RMC, Putavet DA, Klein JDD, Derks KWJ, Bourgeois BRM, Stryeck S, Rijksen Y, van Willigenburg H, Feijtel DA, et al. Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells restores tissue homeostasis in response to chemotoxicity and aging. Cell. 2017;169:132–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan J, Lee Y, Zhang Q, Xiong D, Wan TC, Wang Y, You M. Honokiol decreases lung cancer metastasis through inhibition of the STAT3 signaling pathway. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2017;10:133–141. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-16-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg M, Urnezis P, Tian M. Compressed mints and chewing gum containing magnolia bark extract are effective against bacteria responsible for oral malodor. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9465–9469. doi: 10.1021/jf072122h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang GS, Wang RJ, Zhang HN, Zhang GP, Luo MS, Luo JD. Effects of chronic treatment with honokiol in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:427–431. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillai VB, Samant S, Sundaresan NR, Raghuraman H, Kim G, Bonner MY, Arbiser JL, Walker DI, Jones DP, Gius D, Gupta MP. Honokiol blocks and reverses cardiac hypertrophy in mice by activating mitochondrial Sirt3. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6656. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan Z, Liu H, Song X, Ling Y, He S, Yan Y, Yan J, Wang S, Wang X, Chen A. Honokiol post-treatment ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing autoph-agic flux and reducing intracellular ROS production. Chem Biol Interact. 2019;1:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang L, Zhang K, Guo Y, Huang F, Yang K, Chen L, Huang K, Zhang F, Long Q, Yang Q. Honokiol protects against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity via improving mitochondrial function in mouse hearts. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11989. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12095-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang B, Zhai M, Li B, Liu Z, Li K, Jiang L, Zhang M, Yi W, Yang J, Yi D, et al. Honokiol ameliorates myocardial isch-emia/reperfusion injury in type 1 diabetic rats by reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis through activating the SIRT1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:3159801. doi: 10.1155/2018/3159801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa A, Facchini G, Pinheiro A, da Silva MS, Bonner MY, Arbiser J, Eberlin S. Honokiol protects skin cells against inflammation, collagenolysis, apoptosis, and senescence caused by cigarette smoke damage. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:754–761. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;157:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangali S, Bhat A, Udumula MP, Dhar I, Sriram D, Dhar A. Inhibition of protein kinase R protects against palmitic acid-induced inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis through the JNK/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway in cultured H9C2 cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:3651–3663. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun C, Diao Q, Lu J, Zhang Z, Wu D, Wang X, Xie J, Zheng G, Shan Q, Fan S, et al. Purple sweet potato color attenuated NLRP3 inflammasome by inducing autophagy to delay endothelial senescence. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5926–5939. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun C, Fan S, Wang X, Lu J, Zhang Z, Wu D, Shan Q, Zheng Y. Purple sweet potato color inhibits endothelial premature senescence by blocking the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshihara E, Masaki S, Matsuo Y, Chen Z, Tian H, Yodoi J. Thioredoxin/Txnip: Redoxisome, as a redox switch for the pathogenesis of diseases. Front Immunol. 2014;4:514. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zark JW, Lee SH, Woo GH, Kwon HJ, Kim DY. Downregulation of TXNIP leads to high proliferative activity and estrogen-dependent cell growth in breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498:566–572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji L, Wang Q, Huang F, An T, Guo F, Zhao Y, Liu Y, He Y, Song Y, Qin G. FOXO1 overexpression attenuates tubulointerstitial fibrosis and apoptosis in diabetic kidneys by ameliorating oxidative injury via TXNIP-TRX. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:3286928. doi: 10.1155/2019/3286928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alhawiti NM, Al Mahri S, Aziz MA, Malik SS, Mohammad S. TXNIP in metabolic regulation: Physiological role and therapeutic outlook. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18:1095–1103. doi: 10.2174/1389450118666170130145514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du SQ, Wang XR, Zhu W, Ye Y, Yang JW, Ma SM, Ji CS, Liu CZ. Acupuncture inhibits TXNIP-associated oxidative stress and inflammation to attenuate cognitive impairment in vascular dementia rats. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:39–46. doi: 10.1111/cns.12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin Y, Zhou Z, Liu W, Chang Q, Sun G, Dai Y. Vascular endothelial cells senescence is associated with NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation via reactive oxygen species (ROS)/thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;84:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huy H, Song HY, Kim MJ, Kim WS, Kim DO, Byun JE, Lee J, Park YJ, Kim TD, Yoon SR, et al. TXNIP regulates AKT-mediated cellular senescence by direct interaction under glucose-mediated metabolic stress. Aging Cell. 2018;17:e12836. doi: 10.1111/acel.12836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhuo de X, Niu XH, Chen YC, Xin DQ, Guo YL, Mao ZB. Vitamin D3 up-regulated protein 1(VDUP1) is regulated by FOXO3A and miR-17-5p at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, respectively, in senescent fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31491–31501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Young ME, Chatham JC, Crossman DK, Dell'Italia LJ, Shalev A. TXNIP regulates myocardial fatty acid oxidation via miR-33a signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;311:H64–H75. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00151.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otaki Y, Takahashi H, Watanabe T, Funayama A, Netsu S, Honda Y, Narumi T, Kadowaki S, Hasegawa H, Honda S, et al. HECT-Type ubiquitin E3 ligase ITCH interacts with thioredoxin-interacting protein and ameliorates reactive oxygen species-induced cardio-toxicity. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002485. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spallarossa P, Altieri P, Garibaldi S, Ghigliotti G, Barisione C, Manca V, Fabbi P, Ballestrero A, Brunelli C, Barsotti A. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 are induced differently by doxorubicin in H9c2 cells: The role of MAP kinases and NAD(P H oxidase. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:736–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altieri P, Barisione C, Lazzarini E, Garuti A, Bezante GP, Canepa M, Spallarossa P, Tocchetti CG, Bollini S, Brunelli C, Ameri P. Testosterone antagonizes doxorubicin-induced senescence of cardiomyocytes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002383. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spallarossa P, Altieri P, Aloi C, Garibaldi S, Barisione C, Ghigliotti G, Fugazza G, Barsotti A, Brunelli C. Doxorubicin induces senescence or apoptosis in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes by regulating the expression levels of the telomere binding factors 1-2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H2169–H2181. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00068.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernardes de Jesus B, Blasco MA. Assessing cell and organ senescence biomarkers. Circ Res. 2012;111:97–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang XL, Ji XT, Sun B, Qian LL, Hu XL, Lou HX, Yuan HQ. Anti-cancer effect of marchantin C via inducing lung cancer cellular senescence associated with less secretory phenotype. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2019;1863:1443–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Y, Guo Q, Zhu Q, Tan R, Bai D, Bu X, Lin B, Zhao K, Pan C, Chen H, Lu N. Flavonoid VI-16 protects against DSS-induced colitis by inhibiting Txnip-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages via reducing oxidative stress. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12:1150–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angelis De A, Piegari E, Cappetta D, Marino L, Filippelli A, Berrino L, Ferreira-Martins J, Zheng H, Hosoda T, Rota M, et al. Anthracycline cardiomyopathy is mediated by depletion of the cardiac stem cell pool and is rescued by restoration of progenitor cell function. Circulation. 2010;121:276–292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.895771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sengupta S, Nagalingam A, Muniraj N, Bonner MY, Mistriotis P, Afthinos A, Kuppusamy P, Lanoue D, Cho S, Korangath P, et al. Activation of tumor suppressor LKB1 by honokiol abrogates cancer stem-like phenotype in breast cancer via inhibition of oncogenic Stat3. Oncogene. 2017;36:5709–5721. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sungnoon R, Chattipakorn N. Anti-arrhythmic effects of herbal medicine. Indian Heart J. 2005;57:109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu H, Yin Z, Wang L, Li F, Qiu Y. Honokiol improved chondrogenesis and suppressed inflammation in human umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells via blocking nuclear factor-κB pathway. BMC Cell Biol. 2017;18:29. doi: 10.1186/s12860-017-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang P, Gu JM, Xie ZA, Gu Y, Jie ZW, Huang KM, Wang JY, Fan SW, Jiang XS, Hu ZJ. Honokiol alleviates the degeneration of intervertebral disc via suppressing the activation of TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome signal pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;120:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minguzzi M, Cetrullo S, D'Adamo S, Silvestri Y, Flamigni F, Borzi RM. Emerging players at the intersection of chon-drocyte loss of maturational arrest, oxidative stress, senescence and low-grade inflammation in osteoarthritis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:3075293. doi: 10.1155/2018/3075293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Del Pinto R, Ferri C. Inflammation-Accelerated senescence and the cardiovascular system: Mechanisms and perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E3701. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cordero MD, Williams MR, Ryffel B. AMP-activated protein kinase regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during aging. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: A sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327:296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis BK, Ting JP. NLRP3 has a sweet tooth. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:105–106. doi: 10.1038/ni0210-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed datasets generated during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.