There is a shortage of child psychiatrists in the United States. We identify trends in the level and distribution of child psychiatrists over the past decade (2007–2016).

Abstract

Video Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Historically, there has been a shortage of child psychiatrists in the United States, undermining access to care. This study updated trends in the growth and distribution of child psychiatrists over the past decade.

METHODS:

Data from the Area Health Resource Files were used to compare the number of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children ages 0 to 19 between 2007 and 2016 by state and county. We also examined sociodemographic characteristics associated with the density of child psychiatrists at the county level over this period using negative binomial multivariable models.

RESULTS:

From 2007 to 2016, the number of child psychiatrists in the United States increased from 6590 to 7991, a 21.3% gain. The number of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children also grew from 8.01 to 9.75, connoting a 21.7% increase. County- and state-level growth varied widely, with 6 states observing a decline in the ratio of child psychiatrists (ID, IN, KS, ND, SC, and SD) and 6 states increasing by >50% (AK, AR, NH, NV, OK, and RI). Seventy percent of counties had no child psychiatrists in both 2007 and 2016. Child psychiatrists were significantly more likely to practice in high-income counties (P < .001), counties with higher levels of postsecondary education (P < .001), and metropolitan counties compared with those adjacent to metropolitan regions (P < .05).

CONCLUSIONS:

Despite the increased ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in the United States over the past decade, there remains a dearth of child psychiatrists, particularly in parts of the United States with lower levels of income and education.

What’s Known on This Subject:

More than half of the children in the United States with a treatable mental health disorder do not receive treatment from a mental health professional. One of the driving factors contributing to this unmet need is a shortage in child psychiatrists.

What This Study Adds:

We found that child psychiatrists (per 100 000 children) increased by 22% from 2007 to 2016. However, 70% of US counties had no child psychiatrists in 2007 or 2016, and child psychiatrists were much less prevalent in low-income and less-educated communities.

More than half of the children in the United States with a treatable mental health disorder do not receive treatment from a mental health professional.1–3 One of the driving factors contributing to this unmet need is a shortage in child psychiatrists, which is compounded by growing demand for treatment that places additional pressure on a limited supply of providers.4 Improved screening and diagnostic tools for childhood mental disorders,5 expanded child health insurance coverage,6,7 and greater caregiver awareness of pediatric mental health conditions all contribute to this increased demand. As a result, access to mental health care for children has been highly variable across states and counties.8

Historically, the shortage of child psychiatrists has been most acute among disadvantaged populations, such as racial and ethnic minority youth,9 as well as youth living in impoverished and rural areas.8,10 The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry estimates, for example, that Rhode Island has >6 times as many child psychiatrists per capita as Wyoming does.11 To attract physicians to rural and remote communities, mechanisms like the Health Resources and Services Administration’s National Health Service Corps (NHSC) Loan Repayment Program have offered financial incentives for child psychiatrists and other physicians to serve in designated health professional shortage areas.12 However, as little as 13% of physicians who participate in loan forgiveness programs select the NHSC over alternatives.13,14 As such, it remains unclear whether and to what extent recent policies and programs such as the NHSC’s have improved access to child psychiatrists in underserved communities throughout the United States. Moreover, although there has been an overall increase in the number of mental health providers in the United States, the current literature does not provide specifics on the growth in the number of child psychiatrists over the past decade and where the growth has occurred.

To provide an assessment of national trends in the growth and distribution of child psychiatrists in the United States, we examined the ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children throughout all US counties for the most recent 10-year period data were available: 2007–2016. This information extends an earlier study of child psychiatrist levels in the United States completed in 2006.15 Separately, we examined the relationship between county-level sociodemographic characteristics and child psychiatrist workforce supply to identify characteristics associated with greater access to services over this period.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective time-series analysis of all 50 US states employed repeated cross-sectional data from 2007 to 2016 based on the 5 data sources described below. Data were aggregated at the county level based on US county Federal Information Processing Standard codes.16 The research was deemed exempt from review by Dr McBain’s institutional review board.

Data Sources

Child Psychiatrists

The Area Health Resource Files (AHRF) of the Department of Health and Human Services maintains a county-level inventory of health professionals, including the number of child psychiatrists, on an annual basis. These data draw from the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile,17 for which physicians (including child psychiatrists) report their primary location of practice, including outpatient facilities and hospitals. More specifically, our analyses comprised licensed physicians who have met educational and credentialing requirements to practice as child psychiatrists, including doctors of medicine and doctors of osteopathy. Resident physicians are included. Historically, the AMA Physician Masterfile has been considered to maintain high completeness, with only a small proportion of licensed physicians being labeled “missing,” largely because of how the AMA and state licensing agencies update their files.18

Children

Counts of youth ages 0 to 19 were obtained from the Census of Population and Housing, which is prepared by the US Census Bureau.19 Additionally, the US Census Bureau reports on population density, which is measured as the total population relative to land area in square miles.

County Characteristics

The AHRF contains a repository of county characteristics, elements of which were selected on the basis of Penchansky and Thomas’s20 canonical framework for considering determinants of access. First, we included rural-urban continuum codes, which classify counties according to population size and degree of isolation.21 We consolidated this measure into 5 commonly used levels22–24 that reflect population size and proximity to metropolitan areas: counties in metropolitan areas (levels 1, 2, and 3), urban counties adjacent to metropolitan areas (levels 4 and 6), urban counties not adjacent to metropolitan areas (levels 5 and 7), rural counties adjacent to metropolitan areas (level 8), and rural counties not adjacent to metropolitan areas (level 9).

A second set of AHRF county characteristics comprises socioeconomic measures. Here, we extracted measures of income, education, and employment. The first, median income per capita at the county level unadjusted for inflation, was derived from the US Department of Commerce.25 The second, percentage of adults by county with 4 or more years of college education, was obtained from the US Census Bureau, drawing from the American Community Survey.19 Lastly, percentage unemployment among adults ages 16 and older was extracted from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey.26

A third set of measures from the US Census Bureau quantified the racial and/or ethnic composition of counties. This was represented according to 3 categories: percentage non-Hispanic African American, other non-Hispanic, and Hispanic.19 Lastly, we used Small Area Health Insurance Estimates files from the US Census Bureau to measure the percentage of individuals <65 years of age in each county without public or private health insurance coverage27 as well as the county-level average malpractice insurance premium for internal medicine physicians based on data from the Medical Liability Monitor.28

Data Analysis

After inspecting measures of central tendency and dispersion,29 we made 3 adjustments to account for nonlinearity in measures. First, to address the right skew of county-level median income per capita, we segmented income into quartiles. Second, to account for nonlinearity in the growth of child psychiatrists over time, we constructed year variables (1 for each year) and included all of them in the analysis except 2007, which was used as the reference. Third, based on the right skew of population characteristics, we performed log transformations of child population and population density and introduced a square-of-log term for child population.

We next estimated a multivariable negative binomial regression model with state-level fixed effects. The negative binomial distribution was selected over 0-inflated Poisson because the former more accurately accounted for overdispersion in the data based on the Pearson χ2 dispersion statistic.30 Fixed effects were entered for each state to address the potential of omitted variable bias, such as state-level policies that might influence workforce supply, by removing state-specific variance components.31 SEs were clustered at the state level to account for within-cluster correlation.

We included the following covariates in the negative binomial model: time (year), child population at the county level, urbanicity as connoted by rural-urban continuum code categories, county-level socioeconomic variables (income, education, and employment characteristics), and county-level racial and/or ethnic composition. To aid the interpretation of results, we computed predicted counts using Stata’s margins command (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).32 Predicted counts quantified the number of child psychiatrists in a county on the basis of fitted models calculated with covariates specified at median values for the subgroup of interest. All tests were 2 sided, used an α level of .05, and were conducted in Stata version 15.0.

Results

Child Psychiatrists per 100 000 Population

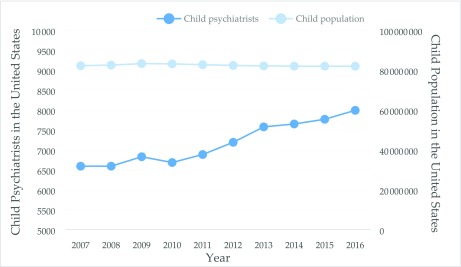

Between 2007 and 2016, the number of practicing child psychiatrists in the United States increased from 6590 to 7991: a 21.3% gain. Over this same time period, the number of children in the United States ages 0 to 19 modestly declined, from 82.22 million to 81.95 million. As such, the ratio of child psychiatrists grew from 8.01 child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in 2007 to 9.75 child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in 2016. These trends are reflected in Fig 1.

FIGURE 1.

Child psychiatrists and children ages 0 to 19 in the United States (2007–2016). Y-axis 1 (right-hand side) signifies the number of child psychiatrists in the United States for each year from 2007 to 2016, whereas y-axis 2 (left-hand side) signifies the number of children ages 0 to 19 in the United States over this period.

The state-level growth of child psychiatrists varied widely. In 2007, 10 states had <5 child psychiatrists per 100 000 children compared with only 5 states in 2016 (Table 1). Meanwhile, the number of states with 10 or more child psychiatrists per 100 000 children increased from 11 to 14. Child psychiatrists per 100 000 children increased by >50% in 6 states (AK, AR, NV, NH, OK, and RI). Conversely, the ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children declined in 6 other states: Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, North Dakota, South Dakota, and South Carolina. In several cases, this was due to faster growth in child population than in child psychiatrists (eg, KS), whereas in others, this reflected an absolute decline in child psychiatrists (eg, ND).

TABLE 1.

Child Psychiatrists in the United States (2007 vs 2016)

| State | 2007 | 2016 | Percent Change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child Population | Child Psychiatrists | Child Population | Child Psychiatrists | Child Population | Child Psychiatrists | ||||

| Total | Rate | Total | Rate | Total | Rate | ||||

| Alabama | 1 251 776 | 69 | 5.5 | 1 223 109 | 81 | 6.6 | −2.3 | 17.4 | 20.1 |

| Alaska | 197 703 | 10 | 5.1 | 201 614 | 20 | 9.9 | 2.0 | 100.0 | 96.1a |

| Arizona | 1 833 847 | 99 | 5.4 | 1 819 004 | 115 | 6.3 | −0.8 | 16.2 | 17.1 |

| Arkansas | 777 002 | 36 | 4.6 | 783 451 | 57 | 7.3 | 0.8 | 58.3 | 57.0a |

| California | 10 487 746 | 809 | 7.7 | 10 129 459 | 1002 | 9.9 | −3.4 | 23.9 | 28.2 |

| Colorado | 1 314 762 | 136 | 10.3 | 1 404 877 | 164 | 11.7 | 6.9 | 20.6 | 12.9 |

| Connecticut | 919 657 | 158 | 17.2 | 857 498 | 217 | 25.3 | −6.8 | 37.3 | 47.3 |

| Delaware | 231 302 | 17 | 7.3 | 229 392 | 21 | 9.2 | −0.8 | 23.5 | 24.6 |

| Florida | 4 489 589 | 267 | 5.9 | 4 612 753 | 359 | 7.8 | 2.7 | 34.5 | 30.9 |

| Georgia | 2 788 367 | 129 | 4.6 | 2 791 134 | 163 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 26.4 | 26.2 |

| Hawaii | 317 588 | 55 | 17.3 | 339 037 | 63 | 18.6 | 6.8 | 14.5 | 7.3 |

| Idaho | 450 317 | 15 | 3.3 | 481 885 | 16 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 6.7 | −0.3b |

| Illinois | 3 574 275 | 223 | 6.2 | 3 256 545 | 272 | 8.4 | −8.9 | 22.0 | 33.9 |

| Indiana | 1 762 882 | 87 | 4.9 | 1 757 412 | 70 | 4.0 | −0.3 | −19.5 | −19.3b |

| Iowa | 800 818 | 40 | 5.0 | 822 142 | 43 | 5.2 | 2.7 | 7.5 | 4.7 |

| Kansas | 777 148 | 56 | 7.2 | 795 569 | 57 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 1.8 | −0.6b |

| Kentucky | 1 110 344 | 79 | 7.1 | 1 124 893 | 89 | 7.9 | 1.3 | 12.7 | 11.2 |

| Louisiana | 1 211 660 | 59 | 4.9 | 1 229 535 | 74 | 6.0 | 1.5 | 25.4 | 23.6 |

| Maine | 313 521 | 46 | 14.7 | 287 787 | 47 | 16.3 | −8.2 | 2.2 | 11.3 |

| Maryland | 1 520 036 | 246 | 16.2 | 1 503 031 | 283 | 18.8 | −1.1 | 15.0 | 16.3 |

| Massachusetts | 1 621 137 | 333 | 20.5 | 1 584 016 | 420 | 26.5 | −2.3 | 26.1 | 29.1 |

| Michigan | 2 734 750 | 177 | 6.5 | 2 459 552 | 194 | 7.9 | −10.1 | 9.6 | 21.9 |

| Minnesota | 1 406 836 | 93 | 6.6 | 1 428 901 | 114 | 8.0 | 1.6 | 22.6 | 20.7 |

| Mississippi | 856 700 | 28 | 3.3 | 804 073 | 36 | 4.5 | −6.1 | 28.6 | 37.0 |

| Missouri | 1 583 410 | 101 | 6.4 | 1 543 666 | 123 | 8.0 | −2.5 | 21.8 | 24.9 |

| Montana | 245 161 | 13 | 5.3 | 253 503 | 18 | 7.1 | 3.4 | 38.5 | 33.9 |

| Nebraska | 498 642 | 33 | 6.6 | 526 284 | 42 | 8.0 | 5.5 | 27.3 | 20.6 |

| Nevada | 715 156 | 25 | 3.5 | 741 723 | 39 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 56.0 | 50.4a |

| New Hampshire | 334 516 | 32 | 9.6 | 297 413 | 49 | 16.5 | −11.1 | 53.1 | 72.2a |

| New Jersey | 2 288 504 | 222 | 9.7 | 2 201 976 | 276 | 12.5 | −3.8 | 24.3 | 29.2 |

| New Mexico | 558 558 | 45 | 8.1 | 545 258 | 55 | 10.1 | −2.4 | 22.2 | 25.2 |

| New York | 4 994 163 | 834 | 16.7 | 4 693 711 | 941 | 20.0 | −6.0 | 12.8 | 20.1 |

| North Carolina | 2 462 736 | 194 | 7.9 | 2 568 891 | 250 | 9.7 | 4.3 | 28.9 | 23.5 |

| North Dakota | 165 743 | 17 | 10.3 | 198 855 | 16 | 8.0 | 20.0 | −5.9 | −21.6b |

| Ohio | 3 064 656 | 217 | 7.1 | 2 916 458 | 245 | 8.4 | −4.8 | 12.9 | 18.6 |

| Oklahoma | 998 488 | 31 | 3.1 | 1 065 347 | 51 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 64.5 | 54.2a |

| Oregon | 956 460 | 80 | 8.4 | 966 539 | 110 | 11.4 | 1.1 | 37.5 | 36.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 155 295 | 324 | 10.3 | 3 020 981 | 368 | 12.2 | −4.3 | 13.6 | 18.6 |

| Rhode Island | 269 314 | 40 | 14.9 | 243 505 | 64 | 26.3 | −9.6 | 60.0 | 77.0a |

| South Carolina | 1 188 713 | 112 | 9.4 | 1 228 625 | 114 | 9.3 | 3.4 | 1.8 | −1.5b |

| South Dakota | 219 891 | 17 | 7.7 | 236 526 | 18 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 5.9 | −1.6b |

| Tennessee | 1 627 003 | 82 | 5.0 | 1 664 765 | 94 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 14.6 | 12.0 |

| Texas | 7 300 611 | 410 | 5.6 | 8 057 140 | 564 | 7.0 | 10.4 | 37.6 | 24.6 |

| Utah | 901 353 | 41 | 4.5 | 1 012 075 | 51 | 5.0 | 12.3 | 24.4 | 10.8 |

| Vermont | 150 407 | 25 | 16.6 | 139 166 | 30 | 21.6 | −7.5 | 20.0 | 29.7 |

| Virginia | 2 041 450 | 178 | 8.7 | 2 092 529 | 204 | 9.7 | 2.5 | 14.6 | 11.8 |

| Washington | 1 701 487 | 109 | 6.4 | 1 802 456 | 137 | 7.6 | 5.9 | 25.7 | 18.6 |

| West Virginia | 434 287 | 22 | 5.1 | 419 018 | 28 | 6.7 | −3.5 | 27.3 | 31.9 |

| Wisconsin | 1 478 223 | 124 | 8.4 | 1 442 699 | 134 | 9.3 | −2.4 | 8.1 | 10.7 |

| Wyoming | 139 909 | 6 | 4.3 | 153 726 | 7 | 4.6 | 9.9 | 16.7 | 6.2 |

Increase >50%.

Declining rate.

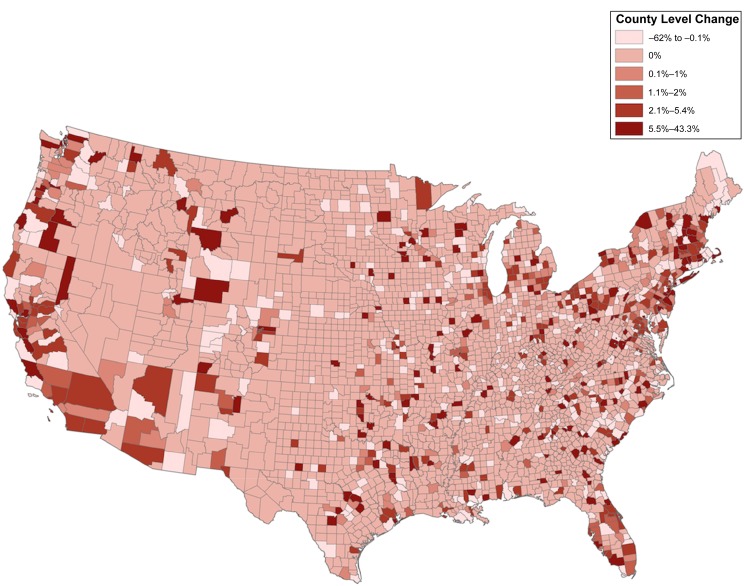

A preponderance of all US counties (76%) experienced no change in the level of child psychiatrists between 2007 and 2016, as illustrated by Fig 2, which is largely a function of the 70% of counties that contained 0 child psychiatrists in both 2007 and 2016. Among the remaining counties, the degree of change in the density of child psychiatrists from 2007 to 2016 was substantial. Within states such as California, Florida, and Massachusetts, an increase in child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in specific counties corresponded with declining levels in neighboring counties.

FIGURE 2.

County-level change in child psychiatrists per 100 000 children (2007–2016).

Distribution by Urbanicity

Compared with the ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in metropolitan areas from 2007 to 2016, there were fewer child psychiatrists in urban counties adjacent to metropolitan areas (P = .02) as well as rural counties adjacent to metropolitan counties (P = .01). There was not a statistically significant difference in the ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children between metropolitan areas and urban areas nonadjacent to metropolitan areas and, separately, between metropolitan areas and rural counties nonadjacent to metropolitan areas (P > .05).

Distribution by Sociodemographic Characteristics

Child psychiatrists were significantly more likely to practice in higher–income-quartile counties (fourth versus first income quartile; P < .001), with 74% of child psychiatrists residing in top-income-quartile counties and 92% in the top-2–income-quartile counties, between 2007 and 2016. As of 2016, the expected number of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in lowest–income-quartile counties was 1.40 compared with 5.04 in the highest-quartile counties: more than a threefold difference (Table 2). An even more stark contrast was observed for education level of the county. Counties in the fifth percentile for completion of postsecondary education would be expected to have 1.10 child psychiatrists compared with 9.79 in the 95th percentile (P < .001). We observed no statistically significant relationship between county-level unemployment and the number of child psychiatrists (P > .05), although counties with lower levels of employment did on average have fewer child psychiatrists (Table 2). We further found no significant relationship between the density of child psychiatrists and percentage of individuals without public or private health insurance (P > .05) or between the density of child psychiatrists and average insurance premium for physicians in the county (P > .05).

TABLE 2.

Expected Number of Child Psychiatrists per 100 000 Children by Characteristic

| Characteristic | Expected Child Psychiatrists | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income quartile | |||

| First (lowest) | 1.40 | 1.01 | 1.79 |

| Second | 2.29 | 1.79 | 2.78 |

| Third | 3.53a | 2.88 | 4.17 |

| Fourth (highest) | 5.06a | 4.19 | 5.92 |

| Education level, percentile | |||

| Fifth | 1.10 | 0.78 | 1.41 |

| 95th | 10.77a | 9.71 | 11.84 |

| Unemployment level, percentile | |||

| Fifth | 3.56 | 2.26 | 4.50 |

| 95th | 1.19a | 0.81 | 1.58 |

Difference is significant at P < .05 compared with the reference group: first quartile or fifth percentile. Expected number of child psychiatrists based on fitted values from negative binomial models with year set to 2016, child population set to 100 000, and covariate characteristics set to median values within the county type of interest. Upper and lower bounds represent the fifth and 95th percentile estimates, respectively.

There was a slightly larger ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in counties with larger non-Hispanic African American populations when adjusting for child population and all other sociodemographic characteristics (P < .001). There was no such evidence that child psychiatrists were more abundant in counties with larger Hispanic populations (P > .05) or in counties with larger percentages of individuals who self-identified as non-Hispanic other (P > .05). Supplemental Table 3 provides an overview of all results from the regression analysis.

Discussion

This analysis provides a timely update on the level and distribution of child psychiatrists in the United States over the past decade. Although the density of child psychiatrists has increased from 2007 to 2016, there remain ∼70% of counties in the United States with no child psychiatrists. The distribution of child psychiatrists also remains inequitable, with a state like Massachusetts having as many child psychiatrists as Oklahoma, Indiana, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee combined, despite these latter states having 5 times as many children ages 0 to 19.

The shortage of child psychiatrists is consonant with previous findings,10,15,33 although we did find that the 1 child psychiatrist for every 12 477 children in 2007 increased to 1 child psychiatrist for every 10 256 children in 2016: a 21.7% improvement. This trend reflects an uptick in the number of child psychiatrists in the United States over this period, from 6590 to 7991, as well as a modest decline in the child population,34 indicating overall improvement in potential access to care.

Despite the trend of more child psychiatrists over time, we also find that this growth is largely restricted to specific geographic areas of the United States and varies significantly at the state and county levels. At the state level, we observed a declining ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children in 6 states (ID, IN, KS, ND, SD, and SC) and an annualized growth <2% in half of all US states. By contrast, 6 states observed a 50% or greater increase in the ratio of child psychiatrists per 100 000 children over this period (AK, AR, NV, NH, OK, and RI). These findings parallel trends in the distribution of mental health professionals in the United States generally8 as well as psychiatry as a discipline specifically.35 Future research in this area should explore whether variable growth in the number of child psychiatrists is tied to specific legislative efforts at the national, state, and local levels.36 Examinations at a local level would be particularly warranted in settings like California or Florida, where we found that growth in the number of child psychiatrists in many counties corresponded with declining numbers in adjacent counties.

One conspicuous factor shaping the distribution of child psychiatrists was, unsurprisingly, child population: although three-quarters of counties (74.7%) had no child psychiatrists in 2016, 80% of children in the United States reside in a county with at least 1 child psychiatrist. In other words, child psychiatrists are disproportionately located in counties with larger child populations, suggesting that the general allocation facilitates access to care. This observation is true more generally for the distribution of human resources for health in the United States. For example, Cummings et al8 found that mental health treatment resources in the United States are more heavily concentrated in urban areas, serving larger, more densely populated counties. However, 1 in 5 children still live in a county without a child psychiatrist, highlighting the ongoing challenge of providing children with local access to psychiatric services.

Similar to findings reported regarding primary care physicians,37 counties with higher levels of education and higher incomes commonly had greater access to child psychiatrists. For example, a county in the 95th percentile of college graduates would be expected to have 9.8 times as many child psychiatrists as a county in the fifth percentile. A similar gradient was observed for income, with 3.6 times as many child psychiatrists expected in counties in the highest income quartile compared with counties in the bottom income quartile. A number of factors may contribute to these trends. For example, wealthier and more highly educated families may be more likely to seek mental health care and be able to pay cash or afford insurance copayments, deductibles, and out-of-pocket expenditures.38 Affordability of child psychiatric services, as a conceptual feature of access to care,20 is particularly problematic because many child psychiatrists do not accept Medicaid, a form of public health insurance that is the single largest payer for mental health services in the United States.39

Additionally, we identified 2 sets of somewhat surprising results. First, urban and rural counties adjacent to metropolitan counties have proportionally fewer child psychiatrists. It is possible that access to care is more limited in metropolitan-adjacent counties because child psychiatrists relocate to affluent metropolitan communities with greater social amenities. Second, we observed a slightly greater density of child psychiatrists in counties with larger African American populations after adjusting for all other factors. One possibility is that habitation in communities with a larger African American representation is merely a proxy for living in specific metropolitan neighborhoods, an observation that has been reported elsewhere.40 If this were the case, examination of the distribution of child psychiatrists at the census-tract level could provide greater resolution on where child psychiatrists congregate within metropolitan regions. Unfortunately, these data are not available. This finding merits further investigation because the broader literature indicates wide-ranging patterns of access to and use of mental health services among African American children and adolescents.41–43

Several limitations should be noted. First, to identify year-on-year trends, population data were drawn from the US Census Bureau, which classifies children ages 0 to 19. This contrasts with previous studies that examined the age range of 0 to 17, preventing direct comparisons. Relatedly, the variable used for uninsured status examined individuals through age 65, not just children ages 0 to 19. Second, the large number of counties with 0 psychiatrists precluded our ability to examine interactions between time and county characteristics. It may be the case that, over a longer time horizon or by pooling child psychiatrists with other mental health professionals, these interactions could be studied at a broader level. Third, although our models included state-level fixed effects, other omitted variables may have been present at the county level. We attempted to account for this by a broad inclusion of covariates.

Lastly, we have no information about the offices that a child psychiatrist is practicing at nor individuals’ level of engagement in the practice. Although the AMA Physician Masterfile is considered robust,44 recent research has raised concern about the accuracy of address-level information.45 As such, we used the file to study child psychiatrist numbers at the county and state levels rather than at a more local level.44 Level of active provider engagement could also shape unmet need. For example, a community with high levels of need for services might be undersupported if child psychiatrists practice infrequently. In this case, the AMA data would overestimate the availability of services. That said, it is also likely that such measures would be endogenous with the outcome of interest: namely, counties with more child psychiatrists could have a greater prevalence of child mental illness because diagnoses in these counties are more frequent due to the presence of child psychiatrists.

Conclusions

We find evidence that the supply of child psychiatrists in the United States has improved over the past 10 years but that a shortage is still profound in large segments of the country. Local and state policies have made efforts to address this through several mechanisms, such as student loan forgiveness programs and higher reimbursement rates, to promote equity in access to services.46 However, our findings suggest that more structural community features, such as average wealth and education, are closely tied to the level of child psychiatrists; as such, broader policies that influence educational and economic opportunity may be required. Absent these, counties with few or no child psychiatrists may need to look to alternative or complementary frameworks to address child mental health needs, including integration of behavioral health in pediatric primary care settings,47 school-based mental health services,48 child psychiatry telephone consultation access programs,49 and new models of telepsychiatry.50

Glossary

- AMA

American Medical Association

- AHRF

Area Health Resource Files

- NHSC

National Health Service Corps

Footnotes

Dr McBain helped conceptualize and design the study and identify, evaluate, and interpret the data and led the drafting and revision of the manuscript; Mr Kofner generated figures and helped evaluate and interpret the data and write and review the manuscript; Drs Stein and Cantor helped conceptualized the study, interpreted the data, and assisted in the writing and review of the manuscript; Dr Vogt helped analyze and interpret the data and assisted in the review and writing of the manuscript; Dr Yu obtained funding support for the study, led the conceptualization of the study, helped interpret the data, and shared in writing and reviewing the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH112760). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10/1542/peds.2019-2646.

References

- 1.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(1):81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitney DG, Peterson MD. US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):389–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ, Schieve LA, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1395–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for autism spectrum disorder in young children: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(7):691–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grace AM, Noonan KG, Cheng TL, et al. The ACA’s pediatric essential health benefit has resulted in a state-by-state patchwork of coverage with exclusions. Health Aff. 2014;33(12):2136–2143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CMS. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/cciio/programs-and-initiatives/other-insurance-protections/mhpaea_factsheet.html. Accessed April 9, 2019

- 8.Cummings JR, Allen L, Clennon J, Ji X, Druss BG. Geographic access to specialty mental health care across high- and low-income US communities. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):476–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Workforce maps by state: practicing child and adolescent psychiatrists. 2018. Available at: https://www.aacap.org/aacap/Advocacy/Federal_and_State_Initiatives/Workforce_Maps/Home.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019

- 12.HRSA. National Health Service Corps. 2018. Available at: https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/. Accessed October 29, 2018

- 13.Kamerow DB. Is the National Health Service Corps the answer? (for placing family doctors in underserved areas). J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(4):499–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagaraj M, Coffman M, Bazemore A. 30% of recent family medicine graduates report participation in loan repayment programs. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(4):501–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas CR, Holzer CE. The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1023–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Census Bureau. 2016 FIPS codes. 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/2016/demo/popest/2016-fips.html. Accessed February 21, 2019

- 17.American Medical Association. AMA Physician Masterfile. 2019. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/masterfile/ama-physician-masterfile. Accessed February 21, 2019

- 18.Cherkin D, Lawrence D. An evaluation of the American Medical Association’s Physician masterfile as a data source–one state’s experience. Med Care. 1977;15(9):767–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed February 21, 2019

- 20.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.USDA. Rural-urban continuum codes. 2017. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx#.VCBR7vldXAs. Accessed February 21, 2019

- 22.Fogleman AJ, Mueller GS, Jenkins WD. Does where you live play an important role in cancer incidence in the U.S.? Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(7):2314–2319 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luu H, Slavova S, Freeman PR, et al. Trends and patterns of opioid analgesic prescribing: regional and rural-urban variations in Kentucky from 2012 to 2015. J Rural Health. 2019;35(1):97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrick SW, Faherty LJ, Dick AW, et al. Association among county-level economic factors, clinician supply, metropolitan or rural location, and neonatal abstinence syndrome. JAMA. 2019;321(4):385–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Commerce Commerce Data Hub. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce; 2019. Available at: https://data.commerce.gov/. Accessed February 21, 2019

- 26.Bureau of Labor Statistics. Local area unemployment statistics. 2017. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/lau/. Accessed February 21, 2019

- 27.US Census Bureau. Small Area Health Insurance Estimates (SAHIE) Program. 2017. Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/sahie.html. Accessed May 6, 2019

- 28.Black B, Chung J, Traczynski J, Udalova V, Vats S. Medical liability insurance premia: 1990–2016 dataset, with literature review and summary information. J Empir Leg Stud. 2017;14:238–254 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Judd CM, McClelland GH, Culhane SE. Data analysis: continuing issues in the everyday analysis of psychological data. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46:433–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer J; The Analysis Factor. Poisson or negative binomial? Using count model diagnostics to select a model. 2018. Available at: https://www.theanalysisfactor.com/poisson-or-negative-binomial-using-count-model-diagnostics-to-select-a-model/. Accessed June 29, 2019

- 31.Wooldridge JM. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 5th ed Mason, OH: Cengage Learning; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stata Corps. Margins. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: Stata Corps; 2014. Available at: https://www.stata.com/manuals13/rmargins.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas CR, Holzer CE. National distribution of child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(1):9–15–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frey W. US Population Growth Hits 80-Year Low. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2018. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2018/12/21/us-population-growth-hits-80-year-low-capping-off-a-year-of-demographic-stagnation/. Accessed May 6, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butryn T, Bryant L, Marchionni C, Sholevar F. The shortage of psychiatrists and other mental health providers: causes, current state, and potential solutions. Int J Acad Med. 2017;3(1):5–9 [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Academy of Pediatrics. Promoting children’s mental health. 2019. Available at: www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/federal-advocacy/Pages/mentalhealth.aspx. Accessed May 6, 2019

- 37.McGrail MR, Wingrove PM, Petterson SM, et al. Measuring the attractiveness of rural communities in accounting for differences of rural primary care workforce supply. Rural Remote Health. 2017;17(2):3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickman SL, Woolhandler S, Bor J, et al. Health spending for low-, middle-, and high-income Americans, 1963–2012. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1189–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Behavioral health services. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/bhs/index.html. Accessed July 22, 2019

- 40.Yang D, Howard G, Coffey CS, Roseman J. The confounding of race and geography: how much of the excess stroke mortality among African Americans is explained by geography? NED. 2004;23(3):118–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elster A, Jarosik J, VanGeest J, Fleming M. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care for adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(9):867–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broder-Fingert S, Shui A, Pulcini CD, Kurowski D, Perrin JM. Racial and ethnic differences in subspecialty service use by children with autism. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):94–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehta NK, Lee H, Ylitalo KR. Child health in the United States: recent trends in racial/ethnic disparities. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:6–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konrad TR, Slifkin RT, Stevens C, Miller J. Using the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile to measure physician supply in small towns. J Rural Health. 2000;16(2):162–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DesRoches CM, Barrett KA, Harvey BE, et al. The results are only as good as the sample: assessing three national physician sampling frames. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(suppl 3):S595–S601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mareck DG. Federal and state initiatives to recruit physicians to rural areas. AMA J Ethics. 2011;13(5):304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richardson LP, McCarty CA, Radovic A, Suleiman AB. Research in the integration of behavioral health for adolescents and young adults in primary care settings: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(3):261–269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Ment Health. 2010;2(3):105–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.NNCPAP National network of child psychiatry access programs. 2019. Available at: https://nncpap.org/thenetwork.html. Accessed May 9, 2019

- 50.Alicata DA, Cheng K. Project echo: child and adolescent mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(10):S74–S75 [Google Scholar]