Abstract

S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) are endogenous signaling molecules that have numerous beneficial effects on the airway via cyclic guanosine monophosphate–dependent and –independent processes. Healthy human airways contain SNOs, but SNO levels are lower in the airways of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). In this study, we examined the interaction between SNOs and the molecular cochaperone C-terminus Hsc70 interacting protein (CHIP), which is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets improperly folded CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) for subsequent degradation. Both CFBE41o− cells expressing either wild-type or F508del-CFTR and primary human bronchial epithelial cells express CHIP. Confocal microscopy and IP studies showed the cellular colocalization of CFTR and CHIP, and showed that S-nitrosoglutathione inhibits the CHIP–CFTR interaction. SNOs significantly reduced both the expression and activity of CHIP, leading to higher levels of both the mature and immature forms of F508del-CFTR. In fact, SNO inhibition of the function and expression of CHIP not only improved the maturation of CFTR but also increased CFTR’s stability at the cell membrane. S-nitrosoglutathione–treated cells also had more S-nitrosylated CHIP and less ubiquitinated CFTR than cells that were not treated, suggesting that the S-nitrosylation of CHIP prevents the ubiquitination of CFTR by inhibiting CHIP’s E3 ubiquitin ligase function. Furthermore, the exogenous SNOs S-nitrosoglutathione diethyl ester and S-nitro-N-acetylcysteine increased the expression of CFTR at the cell surface. After CHIP knockdown with siRNA duplexes specific for CHIP, F508del-CFTR expression increased at the cell surface. We conclude that SNOs effectively reduce CHIP-mediated degradation of CFTR, resulting in increased F508del-CFTR expression on airway epithelial cell surfaces. Together, these findings indicate that S-nitrosylation of CHIP is a novel mechanism of CFTR correction, and we anticipate that these insights will allow different SNOs to be optimized as agents for CF therapy.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, S-nitrosothiols, S-nitrosoglutathione, S-nitrosylation, C-terminus Hsc70 interacting protein

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal-recessive disease that can result in irreparable damage to the respiratory and digestive systems of the body (1). Airway damage involves an accumulation of thick mucus that increases the risk of infections and results in buildup of cysts and scar tissue in the lungs (1). These effects are attributable to several mutations in the genes that encode the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein (1). CFTR is a cAMP-regulated epithelial chloride channel and subtype of the ABC-transporter superfamily, and it is expressed in the apical membrane of epithelial cells in the airways, pancreas, intestines, and other organs (1). The most common genetic mutation associated with CF is F508del-CFTR, which is a result of phenylalanine being deleted from the CFTR amino acid sequence. Because of this deletion, CFTR is misfolded, cannot fully mature, and is selected by molecular chaperones for degradation before it reaches the cell surface (2). Organ damage, in turn, is caused by loss of epithelial Cl− conductance resulting from this loss of CFTR at the cell surface. However, F508del-CFTR exhibits partial function if it is present at the cell membrane; thus, there is interest in potential CF treatments that might allow partially misfolded yet functional F508del-CFTR to reach the cell surface (2, 3).

S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) are a class of naturally occurring signaling compounds that have myriad beneficial effects on airways in humans (4–8). SNOs can transmit nitric oxide (NO) bioactivity through donation of a nitrosonium ion and/or NO (8–15). In so doing, they regulate protein function through S-nitrosylation. S-nitrosylation signaling reactions represent specific post-translational modifications of a wide variety of proteins, are metabolically regulated (16–19), and are often disrupted in pulmonary diseases (13–16), including CF (16, 20–30). Recent evidence suggests that S-nitrosylation prevents the degradation of specific proteins, in part by modifying and inhibiting the active-site cysteine of E3 ubiquitin ligases (31). Because CFTR degradation is triggered by the action of a specific ubiquitin pathway, we have been interested in determining whether SNOs increase CFTR maturation by inhibiting its degradation.

Other research groups and we previously showed that different SNOs increase the maturation, expression, and function of both wild-type (WT) and mutant F508del-CFTR (19–30). These compounds are able to increase the maturation of CFTR proteins through S-nitrosylation of particular cysteine residues in the molecular cochaperones or chaperones that are involved in the biogenesis and trafficking of CFTR (23, 25). Molecular chaperones are proteins that help in the folding of other proteins but do not become part of the final product. Instead, they promote self-assembly of their client proteins and prevent nonproductive folding (32–46). Our previous data indicated that SNOs escalate CFTR maturation by S-nitrosylating cysteine residues on heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70), cysteine string protein (Csp), Hsp70/Hsp90 organizing protein (Hop), and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) (23, 25). An Hsp70-Hsp90 cochaperone known as carboxy terminus Hsc70 interacting protein (CHIP) is responsible for recognizing and initiating the degradation mechanism of misfolded F508del-CFTR protein in the endoplasmic reticulum (32, 39). CHIP has eight cysteine residues, and it interacts not only with Hsp70 and Hsp90 but also with the constitutive Hsp70 homolog (Hsc70), Hop, and CFTR (34, 39, 40). We now show that S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) S-nitrosylates CHIP, decreasing both CHIP expression and activity. This prevents the reciprocal action of maturing CFTR with CHIP. CHIP knockdown with siRNA mimics the effects of SNOs to increase the expression of F508del-CFTR at the cell surface. Therapies targeting this SNO–CHIP interaction have potential as innovative CF correctors.

Methods

Materials

For our experiments, we used the compounds leupeptin and aprotinin (Roche Diagnostics) and Pepstatin A (Boehringer Ingelheim). Electrophoresis reagents were obtained from Bio-Rad. Unless otherwise stated, we obtained all other chemicals from Sigma Chemical Co. We prepared GSNO as described previously (23–25, 27).

Cell Culture

Dr. John Clancy provided CFBE41o− cell lines expressing WT and mutant F508del-CFTR. We obtained primary human bronchial airway epithelial (PHBAE) cells that express WT (4-4-14 HBE1 and 6-18-14 HBE2) and mutant F508del-CFTR (CFHBE, ΔF/ΔF) from our Cell Culture Core. Non-CF primary culture cells were obtained via surgical resection from bronchial tissues, and CF cells were obtained from lung transplants for subjects with CF. We grew CFBE41o− cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium and PHBAE cells in bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM Bullet Kit; Lonza). As previously described, the cells were grown in a monolayer at 37°C and in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air (21–26, 28).

Western Blotting

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (20–25, 27). We grew PHBAE cells that expressed WT and mutant F508del-CFTR and CFBE41o cell lines to confluence in a monolayer. Briefly, we prepared whole-cell extracts in a 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 μM aprotinin, 2 μM leupeptin, and 1 μM pepstatin, 1 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM DTT, and 2 μM Na3VO4). We then recovered insoluble material, which we sheared by passing it through a 25-gauge needle. We used a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific) to quantitate protein by the Lowry assay.

We fractionated 100 μg of protein on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions. We then transferred the fractionated proteins to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked blots in Tris buffered saline (Tween 20), which contained 5% nonfat dried milk. We probed the blots with a dilution (1:1,000) of anti-CFTR monoclonal antibody (mAb) 596 (University of North Carolina); CHIP antibody (anti-CHIP, catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Scientific); anti-ubiquitin antibody (catalog no. SC: 8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The blots were washed and CFTR proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Super Signal West Pico, chemiluminescent substrate, lot no. RE 227122; Thermo Scientific). The blots were stripped and probed with anti-β-actin antibodies (rabbit monoclonal IgM, 1:5,000, catalog no. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology) as a control for protein loading. Relative quantitation was performed by a densitometric analysis of band intensity using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

IP

We performed IP as previously described (20, 21, 23). We grew CFBE41o− cells that expressed WT and mutant F508del-CFTR to confluence. Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described above for Western blot analysis. We added 10 μl of primary CHIP antibody (anti-CHIP, catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Scientific) or CFTR antibody (anti-CFTR mAb 596 antibody; University of North Carolina) to each fraction, and then incubated them overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. We treated supernatant antibody mixtures with 70 μl of Protein A (Boehringer Mannheim) and then incubated them for 4 more hours. Next, we subjected the samples to centrifugation (1 min) and then removed the proteins that were not bound to the beads by washing the beads twice with an RIPA buffer. We then eluted proteins from the beads by incubating them with 100 μl of sample buffer at room temperature, and continuously mixing them for 1 hour. Finally, we fractionated 50 μg of protein on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel under the reducing conditions described above.

Cell-Surface Biotinylation

We performed cell-surface biotinylation as previously described (20, 23). Briefly, we treated CFBE41o− and PHBAE cells that express WT and mutant F508del-CFTR for 4 hours in the presence or absence of the stipulated concentrations of SNOs. We washed the cells three times with ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4) that contained 1 mM MgCl2 (PBSCM) and 0.1 mM CaCl2. We then treated them in the dark with a PBSCM buffer that contained 10 mM sodium periodate for a duration of 30 minutes at 20°C. Next, we rewashed the cells three times with PBSCM and biotinylated them by treating them with a sodium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.5; 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 mM CaCl2) that contained 2 mM of biotin-LC hydrazide (Pierce) at 20°C for 30 minutes in the dark. Then, we washed the cells another three times with a sodium acetate buffer and solubilized them with a lysis buffer that contained protease inhibitors and Triton X-100. We immunoprecipitated CFTR as previously outlined (20, 23) and then subjected the cells to SDS-PAGE on 6% gels under reducing conditions. By using streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP), we determined that CFTR was present on the cell surface.

Analysis of S-Nitrosylated Proteins

We treated CFBE41o− cells with 5 μM and 10 μM GSNO or buffer (4 h), and extracted proteins without reducing agents. We used the biotin switch method to isolate S-nitrosylated proteins from 100 μg of each extract (23, 25, 41). Briefly, we precipitated whole-cell lysates using acetone and then resuspended them in 100 μl of HEN buffer (250 mM HEPES [pH 7.7], 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine). We mixed samples with 4 volume of blocking solution and then incubated them for 20 minutes at 50°C with shaking. We precipitated protein by acetone, resuspended it in a HEN buffer containing 1 mM N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide (Pierce) and 1 mM ascorbate, and then incubated it at room temperature for 1 hour. We removed N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide by precipitation with acetone and then resuspended the pellet in 100 μl of HEN buffer. Next, we neutralized the resuspended sample using a neutralization buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.7], 10 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA). We isolated biotinylated proteins by incubating them with streptavidin agarose at room temperature for 1 hour. Finally, we washed the resin five times with a neutralization buffer containing 600 mM NaCl and then eluted the biotinylated protein with an SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

siRNA Knockdown of CHIP

We arranged and determined siRNA sequences by using a matrix-assisted, laser desorption ionization/time-of-flight spectrometric analysis (Ambion). The CHIP-siRNA duplexes were determined to be >90% pure by a high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Scrambled CHIP siRNA was implemented as the control group. Forty-eight hours after transfection (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) with 50 nM of CHIP siRNA, F508del-CFTR CFBE41o− cells were washed three times with PBS and then lysed. We fractionated a 50 μg protein sample on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel. Blots were then probed at a dilution of 1:500 of monoclonal anti-CHIP antibody (catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody to confirm successful knockdown.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

We grew CFBE41o− cells that expressed WT and mutant F508del-CFTR to confluence on glass coverslips, washed them twice with 5 ml of complete Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS), fixed them with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (5 min), washed them twice with DPBS, and permeabilized them with 0.1% Triton X-100 in DPBS (vol/vol) for 10 minutes. We then washed them two more times with DPBS, incubated them with a blocking solution (0.01% Triton X-100 in 1× DPBS [PBS-T-normal goat serum (NGS)] and 5% NGS) at room temperature for 45 minutes, and incubated them with primary anti-CHIP antibody (1:100, anti-CHIP, catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Scientific) or with primary anti-CFTR antibody (1:150 dilution, mouse mAb 596; University of North Carolina) overnight at 4°C. Next, we washed the cells twice for 15 minutes with blocking solution and incubated them for 45 minutes at room temperature with a secondary antibody to CHIP (1:500 dilution, Alexa Fluor 488; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) or to CFTR (1:500 dilution, Alexa Fluor 568; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) made in blocking solution. We then washed the cells twice in blocking solution with 0.1% NGS for 15 minutes, stained them with DAPI for nuclear staining, and washed them in DPBS. We used an isotype control for mouse and rabbit (BD Pharmingen), respectively, at the same concentrations as the CHIP and CFTR primary antibodies for a negative control, and then labeled it with the respective secondary antibodies. We then mounted and visualized the cells using a 63× NA1.4 oil immersion lens on a Leica TCS SP5 to allow for laser scanning confocal microscopy. We used white-light lasers of 488 nm (20%) and 568 nm (65%) for excitation of CFTR-Alexa Fluor 568 (emission 580–640 nm) and CHIP-Alexa Fluor 488 (emission 500–550 nm), respectively. Finally, the imaging parameters we used for the isotype controls were identical to those described above.

Purification of CHIP and CHIP1–297

Purification of CHIP and CHIP1–297 was performed as previously described (42). Briefly, the full-length human CHIP sequence with N-terminal polyhistidine and V5 affinity tags was PCR amplified from a pETI51/D-TOPO-CHIP construct (Invitrogen) using the primers Nde1CHIP5′GATATACA TATGCATCACCATCAC3′ and BamHICHIP5′TCTATGGATCCTTAATTCTCAGAGATGAATGCGTC3′ (IDT). The resulting PCR product generated a truncated CHIP coding sequence lacking the final six amino acids (CHIP1–297). The DNA corresponding to the truncated CHIP mutant was digested with Ndel1 and BamH1 (Fermentas), gel purified, and ligated into pET21a (Novagen). Clones were isolated and sequenced to confirm the correct truncation and the resulting plasmid was introduced into BL21 (DE3) Escherichia coli (New England Biolabs) by standard transfection techniques. Full-length CHIP and CHIP1–297 were purified by the following procedure: BL21 (DE3) cells carrying the CHIP expression vector were grown from a single colony in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin at 30°C until an A260 of 0.6 was reached. Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the growth media at a final concentration of 1.0 mM and growth was continued for 2 hours at 30°C. Induced cells were collected by centrifugation and cell pellets were stored at −80°C. To purify CHIP, cell pellets were thawed on ice and suspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaPO4, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 3 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mg/ml leupeptin, 2 mg/ml Pepstatin A). A freshly made aliquot of chicken egg lysozyme (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml and the suspension was incubated on ice for 30 minutes to begin cell lysis. The cell suspension was then subjected to sonication for 3-minute bursts with cooling on ice. The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 12,000 RPM in a Sorvall SS34 rotor at 4°C. The lysate was loaded on a 5-ml Nickel NTA column (Qiagen) and allowed to drip through by gravity flow. The column was then washed with an additional 30 ml of lysis buffer (10 mM imidazole) and then 30 ml of lysis buffer containing 30 mM imidazole. CHIP was eluted from the column in lysis buffer containing 200 mM imidazole. CHIP-containing fractions were identified and pooled after SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Purified CHIP was subjected to overnight dialysis in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, and aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

An in vitro ubiquitination assay was performed as previously described (42). Briefly, ubiquitination reaction mixtures were prepared first by combining 0.125 μM E1 (Ube1) and 1 μM E2 (UbcH5b) (Boston Biochem), 200 μM ubiquitin (Sigma), and the appropriate volume of 10× reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM ATP, 40 mM MgCl2), followed by a 30-minute incubation at 37°C. In parallel, a total of 3 μM of purified CHIP was combined on ice with Hsc70 substrate recognition domain (GST-Hsc70395-646) in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and 50 mM NaCl. Control reactions were also set up in the absence of ATP. After addition of the two mixtures, the reactions were incubated for 1 hour at 20°C and then stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer supplemented with 50 mM EDTA. The quenched reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with either anti-GST HRP-conjugated antibody (Abcam) or anti-ubiquitin (catalog no. SC: 8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), which was detected with horse anti-mouse-HRP antibody (Cell Signaling). The concentrations provided for all purified proteins used in the reactions reflect their final reaction concentrations.

Statistical Analysis

For each experiment, we conducted a two-way ANOVA. We included the main effects of the treatment and the band as well as their interaction in each model. We performed the statistical analyses with SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc.). We adjusted multiple comparisons using Dunnett’s method. We considered a P < 0.05 value to be statistically significant.

Results

GSNO Decreases the Steady-State CHIP Levels in CFBE41o− and PHBAE Cells

CHIP is expressed in both mutant F508del-CFTR and WT CFBE41o−, as well as in mutant PHBAE (ΔF/ΔF) cells (Figure 1A). Note that expression levels were significantly higher in CFBE41o− cell lines (both F508del/F508del and WT) when compared with F508del/F508del PHBAE cells. To examine the effect of GSNO, we treated both CFBE41o− cells and primary cells that were homozygous for F508del with a 10 μM concentration, which was previously shown to be effective (20–27, 30). We found decreased CHIP expression in these cells after a 4-hour period (1.9-fold, 4.0-fold, and 3.6-fold, respectively; P < 0.002; n = 4; Figures 1A and 1B).

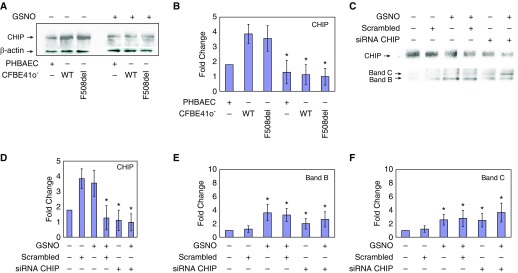

Figure 1.

Decreased levels of C-terminus Hsc70 interacting protein (CHIP) with S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and/or with siRNA increase cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) levels in CFBE41o− cells expressing F508del-CFTR. IB analysis of CHIP was performed on whole-cell extracts from CFBE41o− cells expressing F508del-CFTR and wild-type (WT) CFTR and primary human bronchial airway epithelial (PHBAE) cells expressing F508del-CFTR in the presence or absence of GSNO for 4 hours by using mouse anti-CHIP antibody (catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Fisher Scientific). (A and B) We showed that 10 μM GSNO decreased CHIP expression in all cell lines. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti–β-actin to verify that equal amounts of protein were loaded (catalog no. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology). *P < 0.002. (C–F) CFBE41o− cells were transfected with 50 nM of siRNA duplexes specific for CHIP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and a 100 μg sample of protein was fractionated on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions. Blots were probed with a monoclonal anti-CHIP antibody and anti-CFTR mouse monoclonal antibody (anti-CFTR mAb 596; University of North Carolina). Note that siRNA knockdown decreased CHIP expression and increased CFTR expression (immature B band and mature C band). GSNO also increased CFTR expression alone and in conjunction with CHIP siRNA knockdown. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti–β-actin (catalog no. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology) to verify that equal amounts of protein were loaded. CFBE41o− = CF bronchial epithelial cell line. *P < 0.002 in D and *P < 0.001 in E and F.

CHIP Knockdown Favors F508del-CFTR Biosynthesis

Previous studies indicated that silencing of the gene encoding CHIP increased the levels of F508del-CFTR, and that reduced expression of CHIP stabilized F508del-CFTR both in the endoplasmic reticulum and at the plasma membrane (32, 39, 40). To confirm these results and compare them with the effects of GSNO treatment, we knocked down endogenous CHIP by transfecting CFBE41o− cells with 50 nM of siRNA duplexes specific for CHIP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). We found that after 48 hours of transfection, the endogenous level of CHIP markedly decreased (3.5-fold; P < 0.002; Figures 1C and 1D), which subsequently produced increased levels of mature and immature forms of F508del-CFTR (1.5- and 1.8-fold, respectively; P < 0.001; Figures 1C, 1E, and 1F). Additionally, siRNA-transfected CFBE41o− cells incubated with GSNO (10 μM, 4 h) further increased F508del maturation (immature CFTR band B 1.8-fold; P < 0.005; mature band C 2.8-fold; P < 0.001; Figures 1C, 1E, and 1F) compared with nontreated cells. In contrast, there was no effect when a scrambled siRNA control was applied. These data suggested that GSNO and CHIP operate in the same pathway, consistent with their ability to modulate F508del-CFTR biogenesis.

Effect of Different SNOs on Cell-Surface Targeting of CFTR

Next, we screened various SNOs to assess their activity on the maturation and cell-surface expression of F508del-CFTR using CFBE41o− and PHBAE cells homozygous for F508del-CFTR. We detected the levels of cell-surface protein by performing a cell-surface biotinylation assay. In cells incubated with permeable SNOs (10 μM; 4 h), such as S-nitrosoglutathione diethyl ester (GNODE) and S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine (SNOAC), cell-surface F508del-CFTR expression significantly increased in PHBAE cells expressing F508del-CFTR (from patients with CF), as well as in CFBE41o− cells (Figures 2A–2D). As noted above, a dose of 10 μM was chosen based on previous dose-response studies using GSNO (29, 32). Of note, in both cell types, GNODE and GSNO treatments were the greatest inducers of the expression of F508del-CFTR on the cell surface. It is notable that GSNO (3.1-fold; n = 3; P < 0.001) or GNODE (3.5-fold; n = 3; P < 0.005; Figures 2A and 2B, lanes 4 and 5) significantly increased F508del-CFTR in CF cells. In fact, the level of correction is consistent with results from the positive control (i.e., WT-CFTR) and temperature-rescued F508del-CFTR (Figure 2A, lanes 2 and 3; Figures 2C and 2D, lanes 3 and 7).

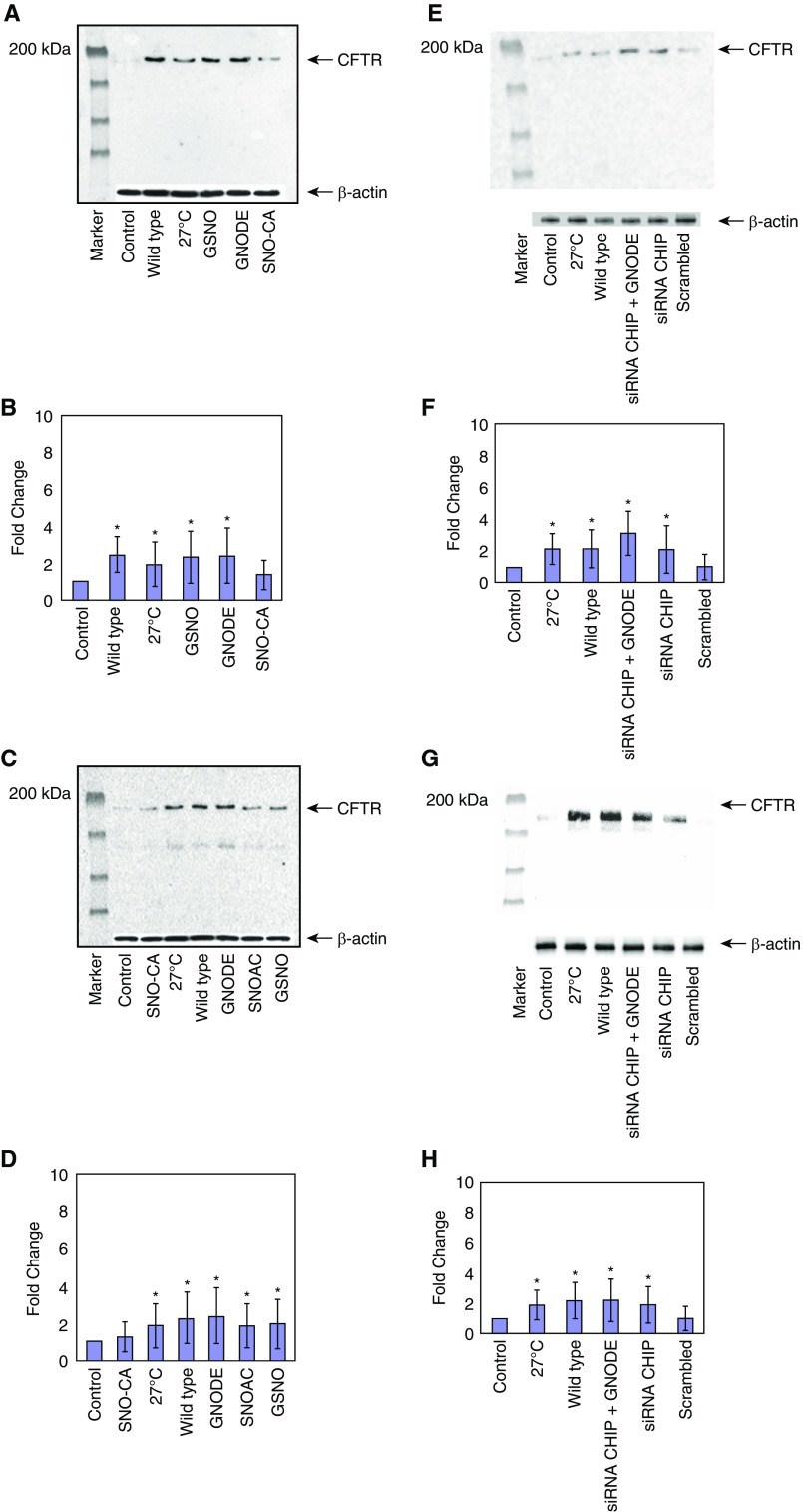

Figure 2.

Cell-surface expression of CFTR is affected by treatment with different S-nitrosothiols (SNOs). Cell-surface biotinylation was performed as described in the Methods section; 100 μg of protein was loaded to each lane and CFTR expression was quantified. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with β-actin (catalog no. 4970; Cell Signaling Technology) to verify that equal amounts of protein were added. (A and B) CFBE41o− F508del. Lane 1: control; lane 2: WT; lane 3: 27°C; lane 4: GSNO; lane 5: S-nitrosoglutathione diethyl ester (GNODE); lane 6: S-nitrosocysteamine (SNO-CA). *P < 0.005. (C and D) PHBAE cells were treated and examined as in A and B. Lane 1: control; lane 2: SNO-CA; lane 3: 27°C; lane 4: WT; lane 5: GNODE; lane 6: S-nitroso-N-acetylcysteine (SNOAC); lane 7: GSNO. Cell-surface expression of CFTR in CHIP knockdown. Knocked down endogenous CHIP in transfected mutant CFBE41o− and PHBAE cells with 50 nM of CHIP siRNA duplexes specific for CHIP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). *P < 0.002. (E and F) Cell-surface expression of CFTR after CHIP knockdown was examined in CFBE41o− F508del cells. Lane 1: control; lane 2: 27°C; lane 3: WT; lane 4: siRNA CHIP + GNODE; lane 5: siRNA CHIP; lane 6: scrambled siRNA. *P <0.005. (G and H) Cell-surface expression of CFTR alter CHIP knockdown was examined in PHBAE cells as in parts E and F. Lane 1: control; lane 2: 27°C; lane 3: WT; lane 4: siRNA CHIP + GNODE; lane 5: siRNA CHIP; lane 6: scrambled siRNA. *P < 0.02.

Effect of SNOs on Cell-Surface Regulation and Stabilization of CFTR by Knockdown of CHIP

To gain an understanding of how CFTR interacts with CHIP on the cell surface, we transfected CFBE41o− and PHBAE cells expressing F508del-CFTR in parallel with 50 nM of siRNA CHIP duplexes specific for CHIP. Our cell-surface labeling results suggested that cell-surface levels of F508del-CFTR were increased in CFBE41o− (2.2-fold; n = 3; P < 0.002; Figures 2E and 2F) and PHBAE (1.6-fold; n = 3; P < 0.01; Figures 2G and 2H) cells after CHIP knockdown. However, the increase in cell-surface F508del-CFTR was even more pronounced in both CFBE41o− (2.8-fold; n = 3; P < 0.005, Figures 2E and 2F) and PHBAE (1.8-fold; n = 3; P < 0.02; Figures 2G and 2H) cells in the presence of GNODE (10 μM, 4 h).

CFTR-Associated CHIP Is S-Nitrosylated

Based on the combined effect of partial CHIP knockdown and GSNO, we next tested whether the population of F508del-CFTR–associated CHIP was S-nitrosylated. CFBE41o− cells were treated with 5 μM and 10 μM GSNO for 4 hours and isolated whole-cell extracts were incubated with antisera to coimmunoprecipitate CHIP and CFTR. SNO-modified CHIP proteins were measured by the copper-cysteine method with chemiluminescent NO analysis, as well as by using an established biotin switch assay as described previously (23, 25, 41). As shown in Figures 3A–3C, we found that CHIP was S-nitrosylated in a concentration-dependent manner.

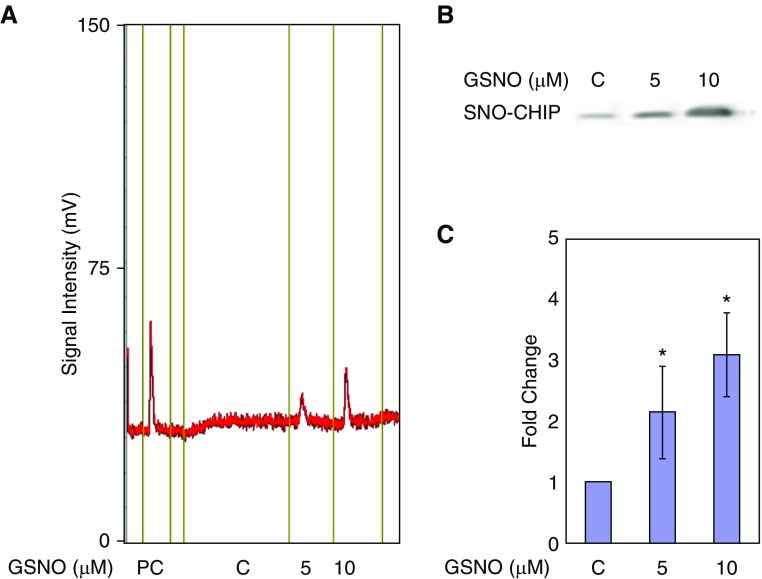

Figure 3.

GSNO S-nitrosylates CHIP. (A) GSNO (10 μM) was injected as a positive control (PC). Then, whole CFBE41o− cells were incubated in the absence (C) or presence of 5 μM and 10 μM GSNO for 4 hours and CHIP-CFTR complexes obtained by co-IP were injected. SNO was assayed with a nitric oxide analyzer using a copper/cysteine system. (B and C) CFBE41o− cells were exposed to 5 μM and 10 μM GSNO for 4 hours. SNO proteins in whole-cell lysates underwent a biotin switch assay followed by streptavidin purification, and then IB with an anti-CHIP antibody (catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Scientific) as described previously. co-IP = co-immunoprecipitation. *P < 0.01.

Cellular Colocalization of CHIP and CFTR in CFBE41o− Cells

As shown by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, CHIP partially colocalized with CFTR (Figure 4A). In contrast, no signal was present when isotype controls were examined (Figure 4B). In addition, by immunoprecipitating CFTR, we showed that exogenous GSNO reduced CFTR associated with CHIP (Figure 4C; n = 3). Taken together, our data demonstrate that CFTR and the cochaperone/E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP interact in CFBE41o− cells, and that this interaction declines after treatment with GSNO.

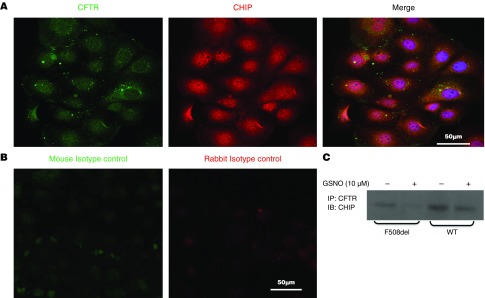

Figure 4.

Cellular residence of CFTR and CHIP. (A) Confocal microscopy. CFBE41o− cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes, permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100, and incubated with primary CFTR (anti-CFTR mAb 596; University of North Carolina) and anti-CHIP antibody (catalog no. PA1-015; Thermo Scientific) at 4°C overnight. Cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 45 minutes at room temperature, mounted on coverslips, and visualized with a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope (SP5X, 63× NA1.4 oil immersion lens). Representative images from triplicate experiments are shown. (B) Mouse and rabbit isotypes were used as a negative control. (C) IP assay. Cellular colocalization of CFTR and CHIP in CFBE41o− cells expressing WT and mutant F508del-CFTR were treated in the presence or absence of 10 μM GSNO for 4 hours, and whole-cell extract was immunoprecipitated with anti-CFTR antibody. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted using anti-CHIP antibody. Scale bars: 50 μm. IP = immunoprecipitated.

GSNO Directly Affects CHIP Activity both In Vitro and in Cells

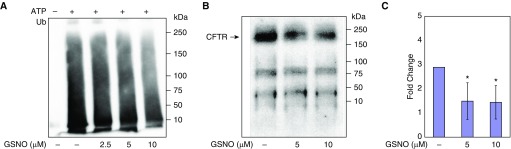

Proteins targeted for 26S proteasome–dependent degradation are polyubiquitinated by E3 ligases, such as CHIP. Therefore, we examined whether GSNO inhibits CHIP-dependent ubiquitination in vitro. In this assay, as shown in Figure 5A, we observed a concentration-dependent inhibition of CHIP autoubiquitination activity. To confirm these results, we incubated CFBE41o− cells with GSNO and immunoprecipitated CFTR. Western blotting was then performed to detect the modified protein. GSNO treatment resulted in less ubiquitinated CFTR (3.4-fold; P < 0.005; n = 3; Figures 5B and 5C) than observed in untreated cells (Figure 5B; third row, lanes 3 and 4, upper bands). Combined with the results presented above, these data are consistent with the ability of S-nitrosylation to modify CHIP, which then leads to an inhibition of CHIP-dependent CFTR ubiquitination.

Figure 5.

S-nitrosylation inhibits CHIP ubiquitination activity and CFTR ubiquitination. (A) A CHIP-dependent autoubiquitination assay was performed in the absence of ATP (lane 1) or presence of ATP and in the absence of GSNO treatment (lane 2) or in the presence of GSNO (lane 3: 2.5 μM; lane 4: 5 μM; lane 5: 10 μM). (B and C) S-nitrosylation of CHIP inhibits CFTR ubiquitination. Whole-cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with monoclonal anti-CFTR antibody (anti-CFTR mAb 596; University of North Carolina) at a dilution of 1:500 and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Supernatant antibody mixtures were treated with 70 μl of Protein A (Boehringer Mannheim) and incubated for another 4 hours. Then, the samples underwent centrifugation, and proteins that were not bound to the beads were removed by washing the beads twice with RIPA buffer. A 100-μg sample of protein was then fractionated on a 6% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions. Blots were probed with a 1:500 dilution of monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibody (catalog no. SC: 8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and 100 μg of protein was loaded to each lane. *P < 0.005.

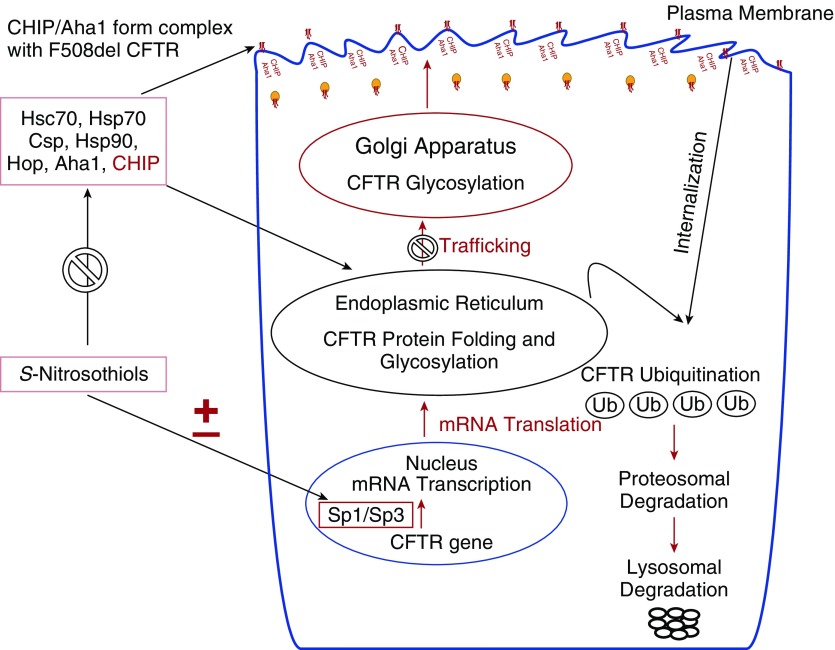

Proposed Model of the Interaction between Different S-Nitrosylating Agents and Molecular Chaperone/Cochaperone Proteins in CFTR Maturation and Trafficking

The effect of GSNO and other endogenous and exogenous S-nitrosylating agents on CFTR expression and maturation is partially transcriptional, through specificity protein Sp1/Sp3 transcription factors. Thus, CFTR expression and maturation is also increased through S-nitrosylating cysteine residues on specific chaperones/cochaperones involved in the regulation of CFTR biogenesis and cell-surface trafficking. These include Hsc70, Hsp70, Hop, the Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1, and CHIP. During maturation and plasma membrane recycling, misfolded F508del-CFTR is ubiquitinated and degraded. S-nitrosylation of these chaperones and cochaperones targeting CFTR for degradation may permit increased F508del-CFTR maturation and cell-surface stabilization.

Discussion

A defective CFTR gene product causes CF, which is the most common lethal inherited disease among white individuals in North America. F508del-CFTR, the most frequent disease-causing CFTR mutation, results in premature protein degradation, so the ion channel is absent from the plasma membrane. If, however, F508del-CFTR is pharmacologically driven to the plasma membrane, it can operate as a cAMP-activated chloride channel, albeit with lower activity (2, 3). Therefore, it is important to identify corrector therapies that can facilitate the trafficking of F508del-CFTR to the plasma membrane. Recent success in achieving this goal has been realized, but further improvements in available corrector therapies are imperative (43–45).

Previous studies indicated that low-micromolar concentrations of SNOs increase the maturation of F508del-CFTR and its cell-surface expression (20). The effect of GSNO and other endogenous and exogenous S-nitrosylating agents on CFTR expression is partially transcriptional, through activation of the specificity protein Sp1/Sp3 transcription factors (24). SNOs also have important post-transcription effects. Complex interactions between many cochaperones impact the folding and trafficking of F508del-CFTR (46). The expression of CFTR is increased by the S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues on the specific chaperone proteins that are involved in the regulation of CFTR biogenesis and cell-surface trafficking. These chaperones/cochaperones include Hsc70, Hsp70, Hop, and Csp (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Illustration of the interaction of SNOs and chaperones/cochaperones in CFTR protein trafficking in airway epithelial cells.

During maturation and plasma membrane recycling, misfolded F508del-CFTR is also ubiquitinated and degraded by the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP (1, 39). We now show that S-nitrosylation–directed inhibition of CHIP also contributes to the increase in maturation and in the cell-surface levels of F508del-CFTR in epithelial cells of the human airway (Figure 6). SNOs are being investigated for their potential as a therapy for CF itself due to multiple qualities. First, they are endogenous compounds in human airways (4, 5). Second, CF (6) and asthma (5, 16) reduce airway levels. Third, GSNO has been used safely in human trials (16). Fourth, they have advantageous effects that are independent of CFTR, such as relaxing airway smooth muscle (7, 9), augmenting the matching of ventilation/perfusion (8), promoting inflammatory cell apoptosis (17), inhibiting the transport of amiloride-sensitive Na+ (10), increasing ciliary beat frequency (10), and antimicrobial effects, among others (4, 5, 7–19). Fifth, they increase WT-CFTR function (20–29). Finally, they can increase F508del expression and maturation. We have previously reported that the corrected protein is functional both within the monolayer and in primary nasal cells (23). However, decreased production results in very low SNO levels in the CF airway. Therefore, inhibiting degradation of GSNO itself is not an effective treatment for CF airway disease. Although inhibition of the GSNO catabolic enzyme GSNO reductase increased weight gain and decreased sweat chloride levels, it did not improve lung function in subjects with CF. This is likely because GSNO synthesis is quite decreased in CF; direct replacement of GSNO or an equivalent will likely be more effective than inhibition of catabolism.

Dose-response studies performed in monolayer cell cultures indicate that GSNO concentrations of 5–10 μM are optimal for CFTR correction in CF cell monolayers (23), but are less effective in pseudostratified epithelial cell cultures. Active transport and peptidases, including γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, are needed for GSNO bioactivation. These systems are present in cells in an array of different depths in pseudostratified epithelia, inhibiting the complete-thickness effect on Cl− transport. Cell-permeable GSNO analogs such as GNODE were able to increase functional F508del-CFTR expression in full-thickness cells. Application of the cell membrane–permeable ester may allow for F508del-CFTR maturation in complex epithelial systems due to S-nitrosylation effects.

With regard to the potential development of an inhalational SNO-like agent as an F508del-CFTR corrector, several lines of biochemical data indicate that it is NO+ transfer (transnitrosation) that is essential to increase maturation of CFTR: 1) numerous S-nitrosylating agents have this ability, and the activities of these compounds are independent of their rates of NO formation or their capacity to act as thiol donors; 2) the common functional characteristic of these compounds is their ability to S-nitrosylate cysteines (15); and 3) the effect is independent of cyclic guanosine monophosphate—in the case of GSNO, the effect is prevented by acivicin and reversed by thiol reduction with DTT. Transnitrosation is necessary in each of the signaling pathways involving health and diseases of different cell and organ systems. Thus, we have studied whether agents such as GNODE and SNOAC, which can bypass the bioactivation required for GSNO and can serve as intracellular NO+ donors, could affect CHIP-dependent CFTR degradation.

Here, we have shown that the increase of CFTR trafficking to the cell surface in monolayer cultures by GSNO involves CHIP (also known as STIP1 homology and U-Box-containing protein 1 [STUB1]). CHIP is fundamental during the regulation of CFTR trafficking (32, 39, 40). We also showed that the 35 kD homodimer associated with CFTR and that CHIP expression was inhibited by several SNOs in different cell lines and in PHBAE cell culture. Additionally, F508del-CFTR was increased by knockdown of CHIP with siRNA, and the effect of this partial knockdown was magnified when SNOs were applied. Therefore, the influence of SNOs on CFTR maturation is associated with the suppression of CHIP expression and/or function. We found that GSNO diminished the CFTR-CHIP interaction by at least two mechanisms. First, it inactivates CHIP by S-nitrosylation, inhibiting the CHIP-target-E3 ubiquitin ligase interaction, as has been reported for the E3 ligase pVHL (31). Second, S-nitrosylation of CHIP appears to target the ligase for proteasomal degradation, and proteasomal inhibition recovers ubiquitinated CHIP despite GSNO treatments.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that F508del-CFTR maturation increased by SNOs involves the cochaperone E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP. The ability of SNOs to inhibit CHIP expression and function may have significance beyond their role in CFTR trafficking. CHIP regulates and associates with the function and expression of CFTR cochaperones, which themselves are S-nitrosylated. These include Hsc70, Hsp90, and Hop (23, 25). Moreover, CHIP activity is associated with the degradation of other misfolded, disease-linked proteins.

New corrector therapies are needed to increase the levels of F508del-CFTR at the cell surface. To date, the effects of GSNO reductase inhibition in the clinic have been disappointing because the CF airway lacks substrate GSNO. However, replacing SNOs with inhaled, cell-permeable GSNO analogs could prove efficacious. There are several potentially relevant therapies that could be considered, including inhaled GNODE, SNOAC, and ethyl nitrite. In the highly oxidative environment of the CF airway, inhaled NO gas will also produce GSNO, which could augment CFTR maturation. However, inhaled NO has several risks, including cancer, hemoptysis, promotion of anaerobic bacterial growth, and epithelial injury.

In conclusion, our study is the first to demonstrate that novel SNOs interact with cochaperone CHIP to prevent F508del-CFTR degradation and improve its stabilization at the cell membrane in CF bronchial airway epithelial and primary human airway pseudostratified columnar epithelial cells. Taken together, our data suggest that SNO replacement may be a valuable approach to an F508del-CFTR corrector therapy. In recent years, the successful use of ivacaftor (VX-770) for the treatment of patients with G551D mutations highlights the importance of finding approaches to target other CFTR mutations, particularly F508del-CFTR in airway epithelial cells. New corrector drugs that are being developed for F508del-CFTR represent major advances but are not completely effective. We anticipate that the current work will help to augment the armamentarium of corrector therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. John Clancy (Gregory Fleming James Cystic Fibrosis Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham) for providing the CFBE41o− cell lines that express WT and mutant F508del CFTR, and Dr. John Riordan (University of North Carolina) for providing the monoclonal anti-CFTR antibody. They also thank the Keck Center for Cellular Imaging at the University of Virginia for the usage of the Leica SP5X microscopy system (RR025616; AP).

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health (1P0HL101871-0 and 1P01HL128192), the National Institutes of Health (GM75061), and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (BRODSK13XX0 and BRODSK18G0).

Author Contributions: K.Z., F.S., T.R., S.J.L., and B.G. contributed to the design and conception of the research. K.Z., J.K., F.H., R.C., S.K.E., G.A., K.H., A.J., V.S., Y.L., P.G., C.C., and A.P. performed experiments. K.Z., J.K., R.C., K.H., and A.J. analyzed data. K.Z., S.K.E., F.S., T.R., C.C., and B.G. helped with the experiments. K.Z., J.K., F.H., B.G., and T.R. interpreted the results of the experiments. K.Z., J.K., F.H., and K.H. prepared figures. K.Z., J.K., F.H., T.R., J.L.B., and B.G. drafted the manuscript. K.Z., J.K., F.H., K.H., J.L.B., and B.G. edited and revised the manuscript. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0314OC on October 9, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Boucher RC. An overview of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:1359–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins FS. Cystic fibrosis: molecular biology and therapeutic implications. Science. 1992;256:774–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1375392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riordan JR. CFTR function and prospects for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:701–726. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaston B, Singel D, Doctor A, Stamler JS. S-nitrosothiol signaling in respiratory biology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1186–1193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1584PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaston B, Reilly J, Drazen JM, Fackler J, Ramdev P, Arnelle D, et al. Endogenous nitrogen oxides and bronchodilator S-nitrosothiols in human airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grasemann H, Gaston B, Fang K, Paul K, Ratjen F. Decreased levels of nitrosothiols in the lower airways of patients with cystic fibrosis and normal pulmonary function. J Pediatr. 1999;135:770–772. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janssen LJ, Premji M, Lu-Chao H, Cox G, Keshavjee S. NO+ but not NO radical relaxes airway smooth muscle via cGMP-independent release of internal Ca2+ Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L899–L905. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.5.L899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bannenberg G, Xue J, Engman L, Cotgreave I, Moldéus P, Ryrfeldt A. Characterization of bronchodilator effects and fate of S-nitrosothiols in the isolated perfused and ventilated guinea pig lung. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:1238–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins WJ, Pabelick C, Warner DO, Jones KA. cGMP-independent mechanism of airway smooth muscle relaxation induced by S-nitrosoglutathione. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C468–C474. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain B, Rubinstein I, Robbins RA, Leise KL, Sisson JH. Modulation of airway epithelial cell ciliary beat frequency by nitric oxide. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;191:83–88. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausladen A, Privalle CT, Keng T, DeAngelo J, Stamler JS. Nitrosative stress: activation of the transcription factor OxyR. Cell. 1996;86:719–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saura M, Zaragoza C, McMillan A, Quick RA, Hohenadl C, Lowenstein JM, et al. An antiviral mechanism of nitric oxide: inhibition of a viral protease. Immunity. 1999;10:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Groote MA, Testerman T, Xu Y, Stauffer G, Fang FC. Homocysteine antagonism of nitric oxide-related cytostasis in Salmonella typhimurium. Science. 1996;272:414–417. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris SL, Walsh RC, Hansen JN. Identification and characterization of some bacterial membrane sulfhydryl groups which are targets of bacteriostatic and antibiotic action. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13590–13594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortenberry JD, Owens ML, Brown LA. S-nitrosoglutathione enhances neutrophil DNA fragmentation and cell death. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L435–L442. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.3.L435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder AH, McPherson ME, Hunt JF, Johnson M, Stamler JS, Gaston B. Acute effects of aerosolized S-nitrosoglutathione in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:922–926. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2105032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall H, Que L, Stamler JS, Gaston B.S-nitrosothiols in lung inflammation: therapeutic targets of airway inflammation Eissa A.editor. Lung biology in health and disease 177New York: Marcel Dekker; 2003123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannick JB, Schonhoff C, Papeta N, Ghafourifar P, Szibor M, Fang K, et al. S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial caspases. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1111–1116. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipton AJ, Johnson MA, Macdonald T, Lieberman MW, Gozal D, Gaston B. S-nitrosothiols signal the ventilatory response to hypoxia. Nature. 2001;413:171–174. doi: 10.1038/35093117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaman K, Bennett D, Butler M, Greenberg Z, Getsy P, Satar A, et al. S-nitrosoglutathione diethyl ester increases cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator expression and maturation in the cell surface. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaman K, Sawczak V, Zaidi A, Butler M, Bennett D, Getsy P, et al. Augmentation of CFTR maturation by S-nitrosoglutathione reductase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310:L263–L270. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00269.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sawczak V, Getsy P, Zaidi A, Sun F, Zaman K, Gaston B. Novel approaches for potential therapy of cystic fibrosis. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16:923–936. doi: 10.2174/1389450116666150102113314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marozkina NV, Yemen S, Borowitz M, Liu L, Plapp M, Sun F, et al. Hsp 70/Hsp 90 organizing protein as a nitrosylation target in cystic fibrosis therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11393–11398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909128107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaman K, Palmer LA, Doctor A, Hunt JF, Gaston B. Concentration-dependent effects of endogenous S-nitrosoglutathione on gene regulation by specificity proteins Sp3 and Sp1. Biochem J. 2004;380:67–74. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaman K, Carraro S, Doherty J, Henderson E, Lendermon E, Liu L, et al. A novel class of compounds that increase CFTR expression and maturation in epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1435–1442. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Patel RP, Teng X, Bosworth CA, Lancaster JR, Jr, Matalon S. Mechanisms of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activation by S-nitrosoglutathione. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9190–9199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaman K, McPherson M, Vaughan J, Hunt J, Mendes F, Gaston B, et al. S-nitrosoglutathione increases cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator maturation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:65–70. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howard M, Fischer H, Roux J, Santos B, Gullans S, Yancey P, et al. Mammalian osmolytes and S-nitrosoglutathione promote delta F508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein maturation and function. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35159–35167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson C, Gaston B, Roomans GM. S-nitrosoglutathione induces functional DeltaF508-CFTR in airway epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:552–557. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Servetnyk Z, Krjukova J, Gaston B, Zaman K, Hjelte L, Roomans GM, et al. Activation of chloride transport in CF airway epithelial cell lines and primary CF nasal epithelial cells by S-nitrosoglutathione. Respir Res. 2006;7:124–133. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer LA, Doctor A, Chhabra P, Sheram ML, Laubach VE, Karlinsey MZ, et al. S-nitrosothiols signal hypoxia-mimetic vascular pathology. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2592–2601. doi: 10.1172/JCI29444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meacham GC, Patterson C, Zhang W, Younger JM, Cyr DM. The Hsc70 co-chaperone CHIP targets immature CFTR for proteasomal degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:100–105. doi: 10.1038/35050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballinger CA, Connell P, Wu Y, Hu Z, Thompson LJ, Yin LY, et al. Identification of CHIP, a novel tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein that interacts with heat shock proteins and negatively regulates chaperone functions. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4535–4545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostrowski LE, Yin W, Diggs PS, Rogers TD, O’Neal WK, Grubb BR. Expression of CFTR from a ciliated cell-specific promoter is ineffective at correcting nasal potential difference in CF mice. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1492–1501. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alberti S, Böhse K, Arndt V, Schmitz A, Höhfeld J. The cochaperone HspBP1 inhibits the CHIP ubiquitin ligase and stimulates the maturation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4003–4010. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chamberlain LH, Burgoyne RD. Activation of the ATPase activity of heat-shock proteins Hsc70/Hsp70 by cysteine-string protein. Biochem J. 1997;322:853–858. doi: 10.1042/bj3220853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Schmidt BZ, Sun F, Condliffe SB, Butterworth MB, Youker RT, et al. Cysteine string protein monitors late steps in cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11312–11321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, et al. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2006;127:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younger JM, Ren HY, Chen L, Fan CY, Fields A, Patterson C, et al. A foldable CFTRΔF508 biogenic intermediate accumulates upon inhibition of the Hsc70-CHIP E3 ubiquitin ligase. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:1075–1085. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okiyoneda T, Barrière H, Bagdány M, Rabeh WM, Du K, Höhfeld J, et al. Peripheral protein quality control removes unfolded CFTR from the plasma membrane. Science. 2010;329:805–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1191542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye Z, Needham PG, Estabrooks SK, Whitaker SK, Garcia BL, Misra S, et al. Symmetry breaking during homodimeric assembly activates an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1789–1798. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01880-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, et al. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18843–18848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105787108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brodsky JL, Frizzell RA. A combination therapy for cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2015;163:17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lukacs GL, Verkman AS. CFTR: folding, misfolding and correcting the ΔF508 conformational defect. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubenstein RC, Zeitlin PL. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate downregulates Hsc70: implications for intracellular trafficking of DeltaF508-CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C259–C267. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.2.C259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.