Abstract

Endothelial cell (EC) inflammation is regarded as an important pathogenic feature of many inflammatory diseases, including acute lung injury and sepsis. An increase in EC inflammation results in neutrophil infiltration from the blood to the site of inflammation, further promoting EC permeability. The ubiquitin E3 ligase TRIM21 has been implicated in human disorders; however, the roles of TRIM21 in endothelial dysfunction and acute lung injury have not been reported. Here, we reveal an antiinflammatory property of TRIM21 in a mouse model of acute lung injury and human lung microvascular ECs. Overexpression of TRIM21 by lentiviral vector infection effectively dampened LPS-induced neutrophil infiltration, cytokine release, and edema in mice. TRIM21 inhibited human lung microvascular endothelial cell inflammatory responses as evidenced by attenuation of the NF-κB pathway, release of IL-8, expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, and adhesion of monocytes to ECs. Furthermore, we demonstrated that TRIM21 was predominantly degraded by an increase in its monoubiquitination and lysosomal degradation after inflammatory stimuli. Thus, inhibition of vascular endothelial inflammation by TRIM21 provides a novel therapeutic target to lessen pulmonary inflammation.

Keywords: ubiquitin E3 ligase, endothelial dysfunction, antiinflammation, lung injury, neutrophil adhesion

Vascular endothelium lines the entire circulation system and maintains vessel integrity (1). Inflammation of endothelial cells (ECs) is the major molecular mechanism of vascular endothelial dysfunction, which is regarded as important pathogenic feature of diabetes (1, 2), rheumatoid arthritis (3), cancer (4), and acute lung injury (5, 6). In the inflammation state, EC activation increases the release of proinflammatory cytokines, expression of cell adhesion molecules, recruitment of circulating leukocytes, and adhesion to ECs, and promotes EC permeability. LPS is a primary pathogenic mediator of EC activation, which activates the classic NF-κB pathway to induce expression of cell adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), VCAM1, integrins, and E-selectin. These adhesion molecules are critical mediators for leukocyte adhesion to ECs (7–9).

The tripartite motif family member TRIM21 (also known as Ro52), an ∼52-kD protein, is broadly expressed in most tissues and cell types (10, 11). TRIM21 has been described as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that catalyzes the ubiquitination of various substrates, including USP4 (12), IRF3 (13), IRF5 (14), IRF7 (15), IRF-8 (16), TRIM5 (17), and TRIM21 itself (18). TRIM21 has been identified as an autoantigen that is recognized by anti-TRIM21 autoantibodies in the sera of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and autoimmune diseases, especially Sjögren’s syndrome (10, 19). Using TRIM21-deficient mice, Yoshimi and colleagues (20) and Espinosa and colleagues (21) found that TRIM21 is a negative regulator of NF-κB–dependent proinflammatory cytokine production. In our study, we investigated whether TRIM21 is involved in endothelial inflammation.

Our study revealed an antiinflammatory role of TRIM21 in a mouse model of acute lung injury and human lung microvascular ECs (HLMVECs). Furthermore, we showed that inflammatory stimuli promoted TRIM21 monoubiquitination and lysosomal degradation. This study suggests that TRIM21 plays a critical role in vascular inflammation and thus provides a potential therapeutic target to treat endothelial inflammatory disorders.

Methods

Animals and LPS Administration

C57BL/6J male mice were housed and cared for in the specific-pathogen-free animal-care facility at the University of Pittsburgh and Ohio State University in accordance with institutional guidelines and the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health. All of the animal experiments were approved by the animal care and use committees of the University of Pittsburgh and Ohio State University, and were performed in accordance with the guidelines outlined by the committees. Lung injury models were obtained by intratracheal administration of LPS (2 mg/kg body weight) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (strain PA103; 1 × 104 cfu per mouse) for 24 hours. For a lentiviral vector delivery system, human TRIM21 cDNA was inserted into the pLVX-IRES-tdTomato vector (Clontech). Lentiviruses expressing TRIM21 and its control were generated and concentrated with a lentivirus packaging system (Clontech). C57/BL6 mice were intravenously administered lentivirus vectors or lenti-TRIM21 (5 × 107 pfu per mouse) for 5 days before intratracheal injection of LPS. After the designated time points indicated in the figure legends, BAL fluid and lung tissues were collected for further analyses.

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining and Lung Injury Scoring

The left lungs from the animals were inflated with 0.5 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin after clearing of the blood for histological evaluation by hematoxylin and eosin staining. All lung fields were imaged at ×20 magnification for each sample. Assessment of histological lung injury was performed as described previously (22).

Immunohistochemistry Staining

Immunohistochemistry was performed using the ImmunoCruze rabbit ABC Staining System (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. An antibody specific for TRIM21 was used for staining. Images were captured with an EVOS inverted microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cell Culture and Reagents

HLMVECs and THP-1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. HLMVECs were cultured in EC growth medium (ECM-2) supplemented with 5% FBS, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; 0.1%), hydrocortisone (0.04%), human fibroblast growth factor basic (0.4%), R3 insulin-like growth factor 1 (0.1%), ascorbic acid (0.1%), human epidermal growth factor (0.1%), and CA-1000 (0.1%) (Clonetics) in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. MG-132 was obtained from EMD Chemicals. LPS, leupeptin, and β-actin antibody were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Antibodies against ICAM1, VCAM1, and Lamin A/C, and immobilized protein A/G beads were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-TRIM21, anti-GAPDH, and anti-V5 were purchased from ProteinTech. Anti-phospho-IκB, p65NF-κB, and anti-ubiquitin were purchased from Cell Signaling. LipoJet reagent and GeneMute siRNA transfection reagent were purchased from SignaGen. Human TRIM21 siRNA and control siRNA were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories. All commercial materials used in the experiments were of the highest grade commercially available.

Construction of Plasmids and siRNA Transfection

Human TRIM21 cDNA was inserted into pcDNA3.1D/His-V5 TOPO vector. (Invitrogen). The sequences of specific primer pairs were as follows: TRIM21 forward, CACCATGGCTTCAGCAGCACGCT; TRIM21 reverse, ATAGTCAGTGGATCCTTGTGATCC. HLMVECs were subcultured on 6-well plates, 60-mm plates,or 100-mm dishes to 70–90% confluence. LipoJet reagent was used for transfection of plasmids into HLMVECs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. siRNAs targeting human TRIM21 were transfected into cells by using the GeneMute siRNA transfection reagent system.

Immunofluorescence Staining

HLMVECs were grown in glass-bottom dishes until they reached 70–80% confluence, and were transfected with plasmids for 48 hours. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 minutes, and blocked with 5% BSA in TBST (25 mM TRIS HCl [pH 7.4], 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 30 minutes. The cells were immunostained with primary antibodies for 1 hour, washed with PBS three times, and incubated with the fluorescent probe–conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were captured with an EVOS microscope.

Assay of THP-1 Adherence to HLMVECs

For adherence assays, HLMVECs were grown in 24-well culture plates and transfected with plasmids for 2 days or with siRNA for 3 days before LPS treatment for 16 hours. THP-1, a human monocytic leukemia cell line, was labeled with Calcein AM (7.5 μm) for 30 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. Calcein AM–labeled THP-1 cells (5 × 105) were added to each well and coincubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Before the assay, the cells were washed with prewarmed RPMI medium to remove nonadherent cells. Relative fluorescence was measured using a microplate reader (BMG Latech) with excitation at 485 nm and emission at 530 nm. Absolute cell numbers were detected by comparison with fluorescence values determined for a dilution series of Calcein AM–labeled cells in RPMI medium.

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assay

For the ubiquitin assay, we performed a modified protocol under denaturing conditions in which the associated protein complex was disrupted. Cells were pretreated with the lysosome inhibitor leupeptin for 1 hour, and then washed and harvested with cold PBS. The supernatant was removed after centrifuging at 2,000 rpm for 5 minutes, followed by addition of 50–80 μl of 2% SDS lysis buffer including 1 μl of ubiquitin aldehyde and 1 μl of N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to the cell pellet. After sonication, the cells were boiled at 100°C for 10 minutes. Samples were diluted with 500–800 μl of 1× TRIS-buffered saline. The following steps were the same as normal IP described in the previous study (23).

qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cultured HLMVECs using the NucleoSpin RNA extraction kit (Clontech Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). qRT-PCR analysis was performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix and the iCycler real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The sequences of specific primer pairs were as follows: hTRIM21 forward, CAGCGTTGAGTCCCCTGTAA; hTRIM21 reverse, ATCATTGTCAAGCGTGCTGC; hGAPDH forward, TCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCG; hGAPDH reverse, GCTCTCCAGAACATCATCCCTGCCT-3.

Western Blotting Analysis

The proteins in the cells or lung tissues were extracted using ice-cold cell lysis buffer containing 20 mM TRIS HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg/ml protease inhibitors, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 μg/ml pepstatin. Protein concentrations were measured with use of a Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Equal amounts of proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel and then electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 hour at room temperature and then incubated with a primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The membranes were then washed three times at 10-minute intervals with TBST before addition of a secondary antibody for 1 hour. Bands were visualized with an Enhanced Chemiluminescence Detection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Western signaling was detected with the Azure c600 imaging system (Azure Biosystems).

Nuclear Protein Isolation

Cell nuclear proteins were extracted using the NE-PER Nuclear Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein concentration was measured using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Protein band intensities were determined using the software ImageJ (Image Processing and Analysis in Java; National Institutes of Health; http://imagej.nih.gov/). All results were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples from at least three independent experiments. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

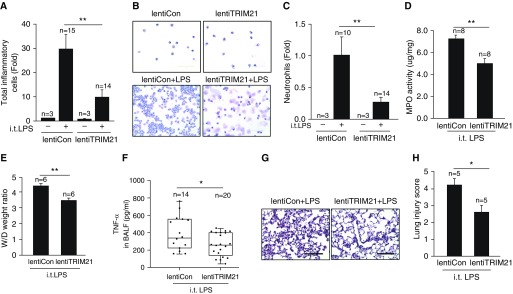

TRIM21 Mitigates LPS-induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice

TRIM21 is known to attenuate the NF-κB pathway (20); however, its role in lung diseases has not been studied. To investigate the role of TRIM21 in lung inflammatory responses, we constructed a lentiviral vector encoding a fusion of TRIM21 (lentiTRIM21), and then intravenously injected C57BL/6J male mice with this construct or a control empty lentiviral vector (lentiCon) for 5 days before intratracheal LPS challenge. Ectopic expression of TRIM21 in the epithelium and endothelium of the lungs was confirmed by immunochemistry staining (Figure E1 in the data supplement). The lentiTRIM21 transduction effectively dampened the LPS-induced lung inflammation phenotype, with reduced cellular infiltration (Figure 1A), neutrophil counts in BAL (Figures 1B and 1C), myeloperoxidase activity in the lungs (Figure 1D), wet/dry lung weight ratios (Figure 1E), TNF-α in BAL (Figure 1F), and lung injury severity (Figures 1G and 1H) in mice. These data indicate that TRIM21 plays an antiinflammatory role in LPS-induced lung injury.

Figure 1.

TRIM21 reduces lung injury induced by LPS challenge in mice. C57BL/6J male mice were subjected to intravenous injection of control lentivirus (lentiCon) or lentivirus encoding TRIM21 (lentiTRIM21) for 5 days and then intratracheal administration of LPS (2 mg/kg body weight) for 24 hours. (A) Total cell counts in BAL were measured with a hemocytometer (n = 14–15 per group); **P < 0.01. (B and C) Neutrophil influx into alveolar spaces was examined by cytospin (n = 10–14 per group); **P < 0.01. (D) Myeloperoxidase activity was detected by ELISA (n = 8 per group); **P < 0.01. (E) Wet/dry (W/D) weight ratios of lung tissues as a parameter for pulmonary edema in lentiCon and lentiTRIM21 mice in the presence of LPS-induced lung injury (n = 6 per group); **P < 0.01. (F) TNF-α in BAL was measured by ELISA (n = 14–20 per group); *P < 0.05. (G) Lung sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Representative images of the staining are shown (n = 10–15 per group). Scale bars: 100 μm. (H) Mean histopathological lung injury scores (n = 5 per group); *P < 0.05. BALF = BAL fluid; i.t. = intratracheal; MPO = myeloperoxidase; TRIM21 = tripartite motif containing 21.

Overexpression of TRIM21 Decreases LPS-induced Activation of NF-κB, IL-8 Release, and Barrier Disruption in HLMVECs

Activation of the NF-κB pathway triggers the lung inflammatory response (24). Previous studies have reported that TRIM21 exhibited an antiinflammatory property (20, 21). We tested whether TRIM21 negatively regulated an LPS-induced NF-κB pathway in HLMVECs. HLMVECs were transfected with empty vector or V5-tagged TRIM21 (TRIM21-V5) plasmid for 48 hours and then treated with LPS for 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 hours. As shown in Figure 2A, overexpression of TRIM21 attenuated phosphorylation of I-κB and NF-κB p65 induced by LPS treatment in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, we found that overexpression of TRIM21 reduced NF-κB p65 subunit nuclear translocation (Figures 2B and 2C). These data confirmed that TRIM21 negatively regulates the NF-κB pathway, and further suggested that TRIM21 may play an antiinflammatory role in HLMVECs. We next investigated the effect of TRIM21 on inflammatory chemokine production induced by LPS in HLMVECs. As shown in Figure 2D, overexpression of TRIM21 attenuated LPS-induced IL-8 release, whereas knockdown of TRIM21 with TRIM21 siRNA enhanced LPS-induced IL-8 release in HLMVECs (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of TRIM21 attenuates LPS-induced phosphorylation of I-κB (p-IκB) , NF-κB P65 (p-p65), and NF-κB P65 subunit nuclear translocation, and IL-8 release in human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HLMVECs). (A) HLMVECs were transfected with plasmids encoding control vector or TRIM21-V5 and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 0, 0.5, 1, and 2 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed by IB with p-IκB, p-p65, V5, and β-actin. Data shown are representative blots from three independent experiments. Intensities of p-IκB, p-p65, and β-actin were evaluated by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 compared with cont + LPS group. (B) HLMVECs were transfected with TRIM21-V5 and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 2 hours. The cells were immunostained with antibody to NF-κB P65 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Red stars indicate NF-κB P65 subunit translocation into the nucleus. The percentage of nuclear P65+ cells was quantified. **P < 0.01. Shown are representative images from three independent experiments. Scale bars: 100 μm. (C) HLMVECs were transfected with TRIM21-V5 and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 2 hours. The nuclear fraction was isolated and analyzed with antibodies to p65, Lamin A/C, and GAPDH. (D) Plasmids encoding control vector or TRIM21-V5 were transfected into HLMVECs for 48 hours and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 0, 2, 4, and 16 hours. Supernatants were harvested to measure IL-8 release by ELISA. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM; n = 3; *P < 0.05. Overexpression of TRIM21-V5 was detected by IB with V5 and β-actin antibodies. (E) HLMVECs were transfected with control siRNA (siCon) or TRIM21 siRNA for 3 days and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 0, 2, 4, and 16 hours. Supernatants were harvested to measure IL-8 release by ELISA. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05. Expression of TRIM21 after siRNA transfection was detected by IB with TRIM21 and β-actin antibodies. Con = control; V5 = A 14-amino-acid V5 epitope derived from simian parainfluenza virus type 5.

It has been known that LPS increases lung endothelial barrier dysfunction (25, 26). To better understand the role of TRIM21 in lung endothelial integrity, we also examined the effect of TRIM21 overexpression on LPS-increased HLMVEC barrier disruption using an electric cell-substrate impedance sensing system. As shown in Figure E2, LPS treatment obviously reduced transendothelial electrical resistance, whereas overexpression of TRIM21 markedly attenuated the effect. These data indicate that overexpression of TRIM21 attenuates LPS-increased barrier disruption in HLMVECs, and that TRIM21 limits LPS’s adverse effects on HLMVECs.

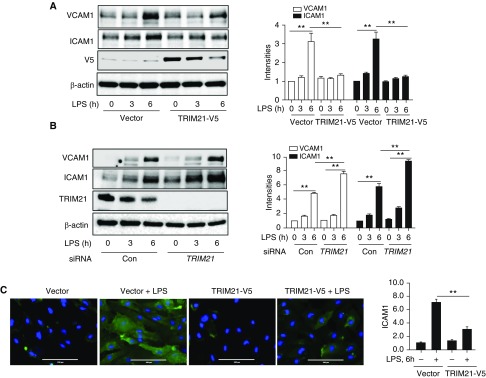

TRIM21 Attenuates LPS-induced ICAM1 and VCAM1 Expression, and Reduces Monocyte Adhesion on ECs

Cell adhesion molecules, such as ICAM1 and VCAM-1, are critical cell-surface glycoproteins to adhesive for neutrophils, which is increased by activated endothelium induced by endotoxin through NF-κB activation (27). To investigate whether TRIM21 affects LPS-induced ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression, HLMVECs were transfected with empty vector or TRIM21-V5 plasmid and then treated with LPS for 0, 3, and 6 hours. Figure 3A shows that overexpression of TRIM21 in HLMVECs decreased LPS-induced ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression. In contrast, knockdown of TRIM21 with TRIM21 siRNA significantly increased LPS-induced ICAM1 and VCAM1 levels in HLMVECs (Figure 3B). Furthermore, immunostaining data show that overexpression of TRIM21 significantly reduced LPS-induced ICAM1 expression in HLMVECs (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that TRIM21 dampens LPS-induced expression of adhesion molecules in HLMVECs.

Figure 3.

TRIM21 attenuates LPS-induced ICAM1 and VCAM1 expression in HLMVECs. (A) HLMVECs were transfected with plasmids encoding control vector or TRIM21-V5 and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 0, 3, and 6 hours. Cell lysates were analyzed by IB with VCAM1, ICAM1, and β-actin. Data shown are representative blots from three independent experiments. Intensities of VCAM1, ICAM1, and β-actin were evaluated by densitometric analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 compared with the control + LPS group. (B) HLMVECs were transfected with control siRNA (siCon) or TRIM21 siRNA for 3 days and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 0, 3, and 6 hours. The intensities of VCAM1, ICAM1, and β-actin were evaluated by densitometric analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 compared with the siCon+LPS group. (C) HLMVECs were transfected with TRIM21-V5 and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 6 hours. The cells were immunostained with antibody to ICAM1 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The intensity of ICAM1 was quantified. **P < 0.01. Shown are representative images from three independent experiments. Scale bars: 100 μm. ICAM1 = intercellular adhesion molecule 1.

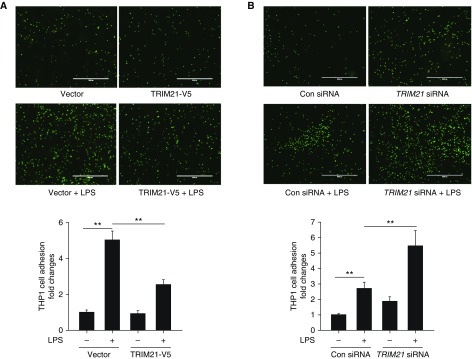

Both IL-8 and adhesion molecules are important for neutrophil recruitment to inflamed ECs (28, 29). To further test whether TRIM21 affects recruitment of inflammatory cells to ECs, HLMVECs were transfected with empty vector or TRIM21-V5 plasmid and the cells were treated with LPS for 16 hours. Human monocytic cell line THP-1 cells were labeled with Calcein AM and then administered to these HLMVECs. Adhesion of THP-1 to HLMVECs was measured. As shown in Figure 4A, overexpression of TRIM21 reduced LPS-induced THP-1 cell adhesion to HLMVECs. Conversely, knockdown of TRIM21 with TRIM21 siRNA enhanced LPS-induced THP-1 cell adhesion to HLMVECs (Figure 4B). The effect of TRIM21 on THP-1 adhesion to HLMVECs may be achieved via a reduction of the NF-κB pathway, IL-8 release, and expression of ICAM1 and VCAM1.

Figure 4.

TRIM21 reduces monocytoid cell adhesion to ECs. (A) HLMVECs were transfected with control vector or TRIM21-V5 plasmids for 48 hours and then the cells were treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 16 hours. Calcein AM–labeled THP-1 cells (5 × 105) were added to each well and coincubated for 1 hour. Adhering Calcein AM–labeled THP-1 cells were counted to evaluate the leukocyte endothelial adherence capacity. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01. Scale bars: 1,000 μm. (B) HLMVECs were transfected with control siRNA or TRIM21 siRNA for 3 days and then the cells were treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 16 hours. Calcein AM–labeled THP-1 cells (5 × 105) were added to each well and coincubated for 1 hour. Adhering Calcein AM–labeled THP-1 cells were counted to evaluate the leukocyte endothelial adherence capacity. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01. Scale bars: 1,000 μm.

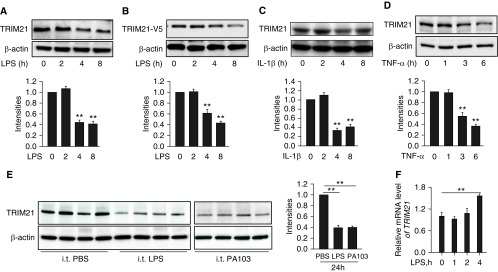

TRIM21 Is Decreased in LPS-, TNF-α–, or IL-1β–stimulated HLMVECs, and Lungs from Murine Models of Acute Lung Injury

We have examined the antiinflammatory effect of TRIM21 in HLMVECs; however, the molecular regulation of TRIM21 has not been well studied. We found that LPS reduced endogenous TRIM21 or overexpressed TRIM21 in HLMVECs (Figures 5A and 5B). In addition to LPS treatment, other proinflammatory stimuli, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, also significantly diminished TRIM21 protein levels in a time-dependent manner (Figures 5C and 5D). The effect of LPS treatment on TRIM21 was also examined in MLE12 epithelial cells. We found that LPS slightly reduced TRIM21 levels, but the differences were not significant (Figure E3). Analysis of TRIM21 levels in murine lungs from LPS- or P. aeruginosa (strain PA103)–induced acute lung injury models revealed that TRIM21 levels were decreased in the inflamed lungs (Figure 5E). The reduction in protein levels was mostly due to inhibition of gene expression or an increase in protein degradation. In addition, we attempted to investigate the molecular mechanisms of LPS-stimulated TRIM21 reduction. As shown in Figure 5F, LPS treatment did not alter the expression of TRIM21 at the transcriptional level. Collectively, these data suggest that the TRIM21 protein is downregulated in acute inflammatory conditions, and that TRIM21 levels may be reduced via a protein degradation mechanism.

Figure 5.

TRIM21 is decreased in response to proinflammatory exposures. (A–D) HLMVECs or TRIM21-V5–overexpressed cells were treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml), IL-1β (10 ng/ml), or TNF-α (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by IB with TRIM21 and β-actin antibodies. Shown are representative blots from three independent experiments. The intensity of TRIM21 was evaluated by densitometric analysis. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01 compared with 0 hour. (E) C57BL/6J mice were challenged with intratracheal injection of LPS (2 mg/kg body weight) or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (strain PA-103, 1 × 104 cfu per mouse) for 24 hours. Lung tissue lysates were analyzed by IB with antibodies against TRIM21 and β-actin. The intensities of the TRIM21 bands were analyzed with the use of ImageJ software. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01. (F) HLMVECs were treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 0, 1, 2, and 4 hours. qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the relative TRIM21 mRNA expression. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; **P < 0.01. cfu = colony forming unit.

LPS Treatment Induces TRIM21 Degradation in the Lysosome

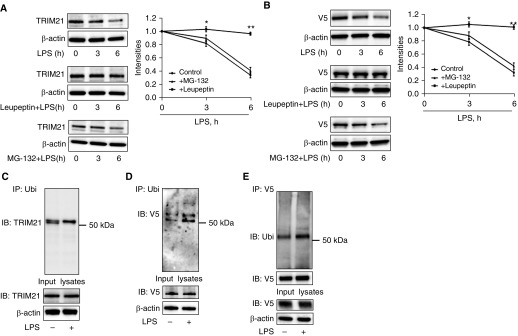

To investigate the possible involvement of the proteasome or lysosome pathways in the degradation of TRIM21, HLMVECs were pretreated with an inhibitor of lysosome (leupeptin) or proteasome (MG-132) activity before LPS treatment. Leupeptin prevented TRIM21 degradation, whereas MG-132 pretreatment had no effect on LPS-induced TRIM21 degradation (Figure 6A). Consistent with our findings from examining endogenous TRIM21 degradation, leupeptin significantly attenuated LPS-induced degradation of overexpressed TRIM21-V5 (Figure 6B). To determine whether TRIM21 degradation is regulated by ubiquitination, we performed cellular ubiquitination assays. The results showed that both endogenous TRIM21 and overexpressed TRIM21 were monoubiquitinated after LPS exposure (Figures 6C–6E). Taken together, these data suggest that TRIM21 degradation is mediated by monoubiquitination in the lysosome.

Figure 6.

TRIM21 degradation is mediated by the ubiquitin–lysosome system. (A and B) HLMVECs (A) or TRIM21-V5–overexpressed HLMVECs (B) were pretreated with MG-132 (20 μM) or leupeptin (100 μM) for 1 hour and then treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for the indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by IB with antibodies to TRIM21, V5, and β-actin. Shown are representative blots from three independent experiments. The intensities of TRIM21 and TRIM21-V5 were analyzed with the use of ImageJ software. All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n = 3; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with control. (C–E) HLMVECs (C) and TRIM21-V5–overexpressed HLMVECs (D and E) were treated with LPS (0.2 μg/ml) for 4 hours. An in vivo ubiquitination assay was performed with a modified IP. Denatured cell lysates were subjected to IP with Ubi beads (C and D) or to IP with V5 antibody conjugated with protein A/G agarose beads (E), followed by IB with antibodies against TRIM21 (C), V5 (D), or Ubi (E). Input lysates were analyzed by IB with TRIM21, V5, Ubi, and β-actin antibodies. Shown are representative blots from three independent experiments. Ubi = ubiquitin.

Discussion

TRIM21, a ubiquitin E3 ligase, has been reported to regulate the NF-κB pathway; however, its role in lung inflammatory diseases has not been revealed. In this study, we show that overexpression of TRIM21 diminishes LPS-induced inflammatory responses in a murine model of acute lung injury. We reveal that TRIM21 negatively regulates the inflammatory responses of LPS-stimulated HLMVECs through attenuation of the NF-κB pathway, release of inflammatory cytokines, expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, and adhesion of monocytes to ECs. Furthermore, we observed molecular regulation of TRIM21 degradation in inflammatory conditions. The reduction of TRIM21 induced by LPS was mediated by monoubiquitination and lysosomal degradation.

Several members of the TRIM family have been shown to play critical roles in inflammatory conditions. For example, TRIM38 was found to negatively regulate TLR-mediated inflammatory responses (30–32). Depletion of the TRIM9 gene had an important effect on NF-κB–mediated cytokine production in the brain (33). TRIM30 inhibited TRAF6 and inactivated NF-κB (34). TRIM28 was shown to control endothelial inflammatory responses and angiogenic activities, retaining expression of TNFR-1 and -2 and VEGF receptor 2 in ECs (35). A recent study suggested that inhaled TRIM72 ameliorates alveolar epithelial cell injury and protects against ventilation-induced lung injury (36). Our study reveals that TRIM21 has an antiinflammatory effect against acute lung injury. This effect of TRIM21 may be achieved through attenuation of the NF-κB pathway, IL-8 production, and expression of adhesion molecules in HLMVECs. In this study, we focused on lung endothelial dysfunction, as our in vivo study suggested that TRIM21 reduces neutrophil infiltration. The effects of TRIM21 on macrophage, alveolar epithelial cell, and neutrophil migration have not been studied. Given the antiinflammatory property and broad expression of TRIM21, it is possible that TRIM21 targets multiple lung cell types to mitigate lung injury. In addition to its antiinflammatory property, in future studies we will investigate the role of TRIM21 in maintaining lung epithelial and endothelial barrier integrity, repair, and remodeling.

Another novel finding in our study is that TRIM21 was degraded in inflammatory conditions. As discussed above, we focused on TRIM21 degradation in ECs in this study. The reduction of TRIM21 by proinflammatory stimuli may occur in other lung cell types. However, the data from this study indicate that the reduction of TRIM21 occurs in lung endothelial, but not epithelial, cells in the setting of inflammatory stimulation. Eames and colleagues showed that LPS treatment did not affect the mRNA level of TRIM28 in human M1 macrophages (37). Choi and colleagues showed that LPS treatment increased the mRNA level of TRIM30 in bone marrow–derived macrophage cells (38). However, the effect of LPS on TRIM28 and TRIM30 expression in lung ECs has not been investigated. Along with the antiinflammatory effect of TRIM21, this finding further supports the conclusion that a reduction in TRIM21 may contribute to the pathogenesis of lung injury.

Post-translational modifications of proteins by acetylation (39), phosphorylation (40), and ubiquitination (41) alter their activity, localization, or stability. Ubiquitin is a 76-amino-acid polypeptide that can be conjugated to substrate protein to mediate stability. Ubiquitin E3 ligases catalyze protein ubiquitination and play an important role in controlling multiple cellular functions (42). Polyubiquitinated proteins are mostly recognized by the 26S proteasome complex and are rapidly degraded into short peptides (43). Monoubiquitination regulates protein intracellular localization and activity, and protein degradation in the lysosome (44–46). TRIM21 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that catalyzes the ubiquitination of various substrates (12–14, 16, 17). Several reports have shown that TRIM21 itself can be monoubiquitinated (18, 47). Consistent with that observation, we also found that TRIM21 was monoubiquitinated in response to LPS. Further studies are needed to investigate whether TRIM21 ubiquitination is dependent on its phosphorylation, and to identify the TRIM21 ubiquitination site.

In summary, our results demonstrate that monoubiquitination and lysosomal degradation of TRIM21 in inflammatory conditions may contribute to the pathogenesis of acute lung injury. We reveal that TRIM21 exhibits an antiinflammatory property against LPS-induced lung endothelial dysfunction and neutrophil adhesion to ECs. Our findings indicate that maintenance of TRIM21 levels may represent a new therapeutic strategy to treat lung injury. Because endothelial dysfunction triggers multiple organ dysfunction, TRIM21 may be a new therapeutic target for systemic inflammatory diseases such as sepsis.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01GM115389 (J.Z.) and HL136294 and HL131665 (Y.Z.).

Author Contributions: Y.Z. and J.Z. designed the study. L.L. and J.W. performed experiments and analyzed the data. L.L. and J.Z. prepared the manuscript. R.K.M. and Y.Z. performed experiments, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0366OC on June 11, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dandona P. Endothelium, inflammation, and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2002;2:311–315. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onat D, Brillon D, Colombo PC, Schmidt AM. Human vascular endothelial cells: a model system for studying vascular inflammation in diabetes and atherosclerosis. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0182-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mäki-Petäjä KM, Booth AD, Hall FC, Wallace SM, Brown J, McEniery CM, et al. Ezetimibe and simvastatin reduce inflammation, disease activity, and aortic stiffness and improve endothelial function in rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:852–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aird WC. The role of the endothelium in severe sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Blood. 2003;101:3765–3777. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xing J, Birukova AA. ANP attenuates inflammatory signaling and Rho pathway of lung endothelial permeability induced by LPS and TNFalpha. Microvasc Res. 2010;79:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim I, Moon SO, Park SK, Chae SW, Koh GY. Angiopoietin-1 reduces VEGF-stimulated leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells by reducing ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin expression. Circ Res. 2001;89:477–479. doi: 10.1161/hh1801.097034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim I, Moon SO, Kim SH, Kim HJ, Koh YS, Koh GY. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin through nuclear factor-kappa B activation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7614–7620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nri2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibilia J. Ro(SS-A) and anti-Ro(SS-A): an update. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1998;65:45–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhodes DA, Ihrke G, Reinicke AT, Malcherek G, Towey M, Isenberg DA, et al. The 52 000 MW Ro/SS-A autoantigen in Sjögren’s syndrome/systemic lupus erythematosus (Ro52) is an interferon-gamma inducible tripartite motif protein associated with membrane proximal structures. Immunology. 2002;106:246–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wada K, Kamitani T. UnpEL/Usp4 is ubiquitinated by Ro52 and deubiquitinated by itself. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgs R, Ní Gabhann J, Ben Larbi N, Breen EP, Fitzgerald KA, Jefferies CA. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Ro52 negatively regulates IFN-beta production post-pathogen recognition by polyubiquitin-mediated degradation of IRF3. J Immunol. 2008;181:1780–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazzari E, Korczeniewska J, Ní Gabhann J, Smith S, Barnes BJ, Jefferies CA. TRIpartite motif 21 (TRIM21) differentially regulates the stability of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) isoforms. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgs R, Lazzari E, Wynne C, Ní Gabhann J, Espinosa A, Wahren-Herlenius M, et al. Self protection from anti-viral responses–Ro52 promotes degradation of the transcription factor IRF7 downstream of the viral Toll-like receptors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong HJ, Anderson DE, Lee CH, Jang MK, Tamura T, Tailor P, et al. Cutting edge: autoantigen Ro52 is an interferon inducible E3 ligase that ubiquitinates IRF-8 and enhances cytokine expression in macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:26–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamauchi K, Wada K, Tanji K, Tanaka M, Kamitani T. Ubiquitination of E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM5 alpha and its potential role. FEBS J. 2008;275:1540–1555. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada K, Kamitani T. Autoantigen Ro52 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshimi R, Ishigatsubo Y, Ozato K. Autoantigen trim21/ro52 as a possible target for treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Rheumatol. 2012;2012:718237. doi: 10.1155/2012/718237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimi R, Chang TH, Wang H, Atsumi T, Morse HC, III, Ozato K. Gene disruption study reveals a nonredundant role for TRIM21/Ro52 in NF-kappaB-dependent cytokine expression in fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2009;182:7527–7538. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinosa A, Dardalhon V, Brauner S, Ambrosi A, Higgs R, Quintana FJ, et al. Loss of the lupus autoantigen Ro52/Trim21 induces tissue inflammation and systemic autoimmunity by disregulating the IL-23-Th17 pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1661–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Alessio FR, Tsushima K, Aggarwal NR, West EE, Willett MH, Britos MF, et al. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs resolve experimental lung injury in mice and are present in humans with acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2898–2913. doi: 10.1172/JCI36498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, Wei J, Mialki RK, Mallampalli DF, Chen BB, Coon T, et al. F-box protein FBXL19-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of the receptor for IL-33 limits pulmonary inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:651–658. doi: 10.1038/ni.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao H, Yang SR, Kode A, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Adenuga D, et al. Redox regulation of lung inflammation: role of NADPH oxidase and NF-kappaB signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1151–1155. doi: 10.1042/BST0351151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xing J, Wang Q, Coughlan K, Viollet B, Moriasi C, Zou MH. Inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase accentuates lipopolysaccharide-induced lung endothelial barrier dysfunction and lung injury in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirano S, Rees RS, Yancy SL, Welsh MJ, Remick DG, Yamada T, et al. Endothelial barrier dysfunction caused by LPS correlates with phosphorylation of HSP27 in vivo. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2004;20:1–14. doi: 10.1023/b:cbto.0000021019.50889.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SR, Bae YH, Bae SK, Choi KS, Yoon KH, Koo TH, et al. Visfatin enhances ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression through ROS-dependent NF-kappaB activation in endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:886–895. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galkina E, Ley K. Vascular adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2292–2301. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerszten RE, Garcia-Zepeda EA, Lim YC, Yoshida M, Ding HA, Gimbrone MA, Jr, et al. MCP-1 and IL-8 trigger firm adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelium under flow conditions. Nature. 1999;398:718–723. doi: 10.1038/19546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao W, Wang L, Zhang M, Yuan C, Gao C. E3 ubiquitin ligase tripartite motif 38 negatively regulates TLR-mediated immune responses by proteasomal degradation of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 in macrophages. J Immunol. 2012;188:2567–2574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu MM, Xie XQ, Yang Q, Liao CY, Ye W, Lin H, et al. Trim38 negatively regulates tlr3/4-mediated innate immune and inflammatory responses by two sequential and distinct mechanisms. J Immunol. 2015;195:4415–4425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao W, Wang L, Zhang M, Wang P, Yuan C, Qi J, et al. Tripartite motif-containing protein 38 negatively regulates TLR3/4- and RIG-I-mediated IFN-β production and antiviral response by targeting NAP1. J Immunol. 2012;188:5311–5318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi M, Cho H, Inn KS, Yang A, Zhao Z, Liang Q, et al. Negative regulation of NF-κB activity by brain-specific TRIpartite motif protein 9. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4820. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi M, Deng W, Bi E, Mao K, Ji Y, Lin G, et al. TRIM30 alpha negatively regulates TLR-mediated NF-kappa B activation by targeting TAB2 and TAB3 for degradation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:369–377. doi: 10.1038/ni1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Li J, Huang Y, Dai X, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Tripartite motif-containing 28 bridges endothelial inflammation and angiogenic activity by retaining expression of TNFR-1 and -2 and VEGFR2 in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2017;31:2026–2036. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600988RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagre N, Cong X, Ji HL, Schreiber JM, Fu H, Pepper I, et al. Inhaled TRIM72 protein protects ventilation injury to the lung through injury-guided cell repair. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;59:635–647. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0364OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eames HL, Saliba DG, Krausgruber T, Lanfrancotti A, Ryzhakov G, Udalova IA. KAP1/TRIM28: an inhibitor of IRF5 function in inflammatory macrophages. Immunobiology. 2012;217:1315–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi UY, Hur JY, Lee MS, Zhang Q, Choi WY, Kim LK, et al. Tripartite motif-containing protein 30 modulates TCR-activated proliferation and effector functions in CD4+ T cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nusinzon I, Horvath CM. Histone deacetylases as transcriptional activators? Role reversal in inducible gene regulation. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re11. doi: 10.1126/stke.2962005re11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cozzone AJ. Post-translational modification of proteins by reversible phosphorylation in prokaryotes. Biochimie. 1998;80:43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(98)80055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinyamu HK, Chen J, Archer TK. Linking the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to chromatin remodeling/modification by nuclear receptors. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;34:281–297. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berndsen CE, Wolberger C. New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:301–307. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pickart CM, Fushman D. Polyubiquitin chains: polymeric protein signals. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hicke L. Protein regulation by monoubiquitin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:195–201. doi: 10.1038/35056583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka Y, Tanaka N, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, Murakami M, Hirano T, et al. c-Cbl-dependent monoubiquitination and lysosomal degradation of gp130. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4805–4818. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01784-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clague MJ, Urbé S. Ubiquitin: same molecule, different degradation pathways. Cell. 2010;143:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niida M, Tanaka M, Kamitani T. Downregulation of active IKK beta by Ro52-mediated autophagy. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:2378–2387. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]