Abstract

Kim H Nguyen and colleagues examine how tobacco companies applied their knowledge of flavours, colours, and child focused marketing to develop leading children’s sugar sweetened drink brands. These techniques continue to be used by drinks companies despite industry agreement not to promote unhealthy products in this way

Sugar sweetened beverages are a risk factor for obesity and cardiometabolic disease.1 2 3 4 Young children are particularly susceptible to the persuasive influence of adverts for sugary drinks,5 6 7 and the World Health Organization has urged governments to tighten food and drink marketing restrictions to protect children.8

Marketing of sugary drinks to children by multinational corporations, and the need to regulate it, have been public concerns since the 1970s.9 10 11 12 13 In 1974 the Better Business Bureau created the Children’s Advertising Review Unit to promote “responsible” children’s advertising through industry self policing. In 2006, in response to calls for government regulation, industry created its Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI).14 CFBAI members pledge “to shift the mix of advertising primarily directed to children (‘child-directed advertising’) to encourage healthier dietary choices,” to “devote 100% of their child-directed advertising to better-for-you foods, or to not engage in such advertising,” and to “limit the use of third-party licensed characters, celebrities and movie tie-ins.”15

Comparisons have been made between the tobacco and soft drink industries, 16 17 including similarities in aggressive activities to oppose taxation and marketing restrictions, leading some to ask, “Is sugar the new tobacco?”18 19 Internal tobacco industry documents show that many of today’s leading children’s drink brands were once owned and developed by tobacco companies (table 1; see supplementary data on bmj.com for document sources and research methods).

Table 1.

Ownership of large brands of children’s sugary drinks

| Brand | Tobacco corporation ownership | Ownership in 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Hawaiian Punch | R J Reynolds, 1963-89 | Dr Pepper Snapple (USA) |

| Tang | Philip Morris, 1985-2007* | Mondelēz International |

| Kool-Aid | Philip Morris,1985-2007* | Kraft-Heinz |

| Capri Sun | Philip Morris,1991-2007* | Kraft-Heinz (North America), Coca-Cola Enterprises (Netherlands, UK, Belgium, Ireland, and France) and Mondelēz International (Mexico, Philippines, and Indonesia) |

In 2001, Philip Morris sold 280 million Kraft shares, retaining an 88.1% stake in the company. As of 2007, Philip Morris (now Altria) sold its stake in Kraft foods and the two companies were no longer affiliated.20

R J Reynolds and Philip Morris, the two largest US based tobacco conglomerates, began acquiring soft drink brands in the 1960s and were instrumental in developing leading children’s drink brands, including Hawaiian Punch, Kool-Aid, Capri Sun, and Tang. Tobacco executives transferred their knowledge of marketing to young people and expanded product lines using colours, flavours, and marketing strategies originally designed to market cigarettes. They eventually sold these brands to globalised food and drink corporations, which, despite the CFBAI pledge to which most had committed, were continuing in 2018 to implement some of the tobacco companies’ integrated marketing campaigns to reach very young children.

R J Reynolds and Hawaiian Punch

Until the 1960s, the sugary drink industry was dominated by Coca-Cola and Pepsi, which marketed brands without prioritising children over adults.21 During the 1960s, both firms began experimenting with new products: Coca-Cola launched Fanta, Tab, and Sprite while Pepsi launched Teem, Mountain Dew, and Diet Pepsi, but none was exclusively aimed at children.22 23 24 25 26

In May 1962, the vice president of R J Reynolds Industries authorised the company’s laboratories to develop powdered and fizz tablet forms of sugary drinks and to carry out market research with them on children (see table A on bmj.com).27 In a 1962 memorandum to the director of research, Reynolds’ manager of biochemical research wrote, “It is easy to characterise R J Reynolds merely as a tobacco company. In a broader and much less restricting sense, however, R J Reynolds is in the flavour business.”28 29 He noted that, “many flavourants for tobacco [would] be useful in food, beverage and other products” producing “large financial returns.” In 1963, Reynolds’ “idea of compressing effervescent powder on a stick” became the King Stir Stick, allowing children to create a sugary drink by stirring the stick in water.30 That year, Reynolds scaled up production to one million sticks a month.30

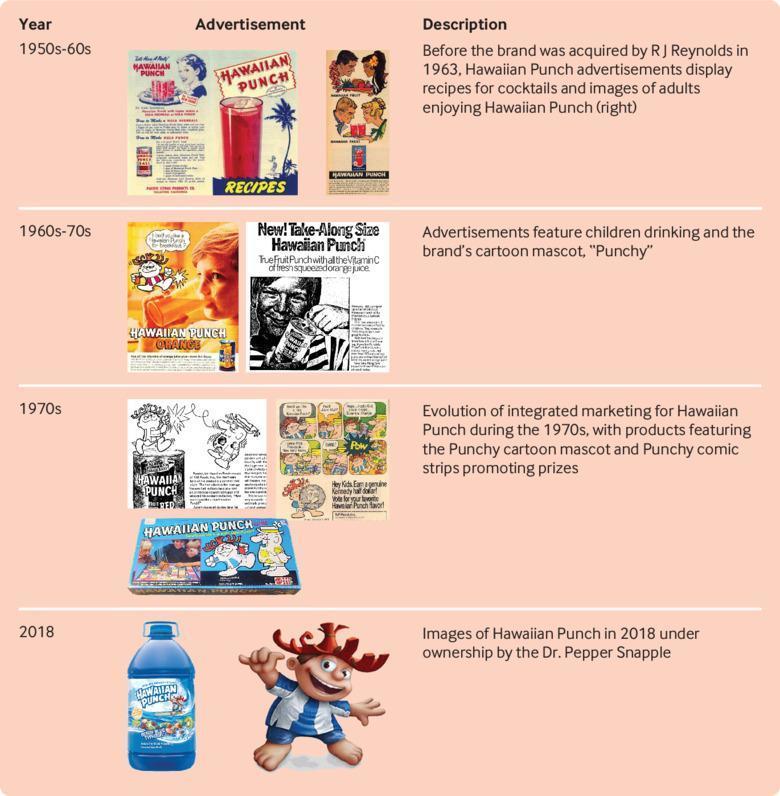

In 1963, as part of its effort to diversify beyond tobacco, Reynolds purchased Pacific Hawaiian Products, which made Hawaiian Punch.31 At the time Pacific Hawaiian sold Hawaiian Punch in two flavours as an at-home cocktail mixer for adults (fig 1). From 1966 to 1977, Reynolds conducted at least 34 market research studies with children and housewives, including taste tests evaluating the sweetness, flavours, and colours for Hawaiian Punch product line extensions (table B on bmj.com).

Fig 1.

Evolution of advertising for Hawaiian Punch

Children’s preferences were prioritised. A taste test for an apple flavour found that housewives preferred amber colour whereas children preferred red, resulting in the recommendation to “discontinue further development of the Amber Apple product and…to introduce Red Apple.”32 These tests led Reynolds to expand from two to at least 16 flavours and 24 products.32 33 34 35 36 37 38

Hawaiian Punch’s cartoon mascot, Punchy, first appeared in 1962, just before Reynolds bought the brand. Reynolds made Punchy the “focus of a total marketing approach.”39 During 1963-79, Punchy was featured in television commercials, magazines, and Sunday comics and on school book covers, toys, clothing, tumblers, and wrist watches.40 41 42 43 RJR World, the employee magazine, noted that “[h]is presence on point-of-purchase displays lends instant eye-appeal” and that Punchy was “The best salesman the beverage has ever had.”40

Hawaiian Punch was originally available in 46 oz (1.36 L) canisters. In 1973, Reynolds introduced snap open 8 oz (230 mL) cans as a “take-along size…perfect for children. They’re easy to hold, easy to open and great to drink.”40 In 1976, Reynolds introduced a powdered version in four flavours, generating $50m (£38m; €44m) in the first year.44 Reynolds’ press release stated that its strategy of introducing the same product in liquid and powdered form was “one of the most successful ever in the food industry.”45 By 1978, Reynolds made five forms: liquid, frozen, shelf concentrate, and presweetened and unsweetened powdered.35 In 1983, Reynolds introduced the first nationally distributed aseptic packaging (“juice box”), a single serving drink marketed as a “handy little carton that comes with its very own straw” with the slogan, “Go Hawaiian when you’re on the go.”46 The chief executive of Reynolds’ food subsidiary Del Monte observed, “Hawaiian Punch increased about 34 percent last year, and that was mostly a function of the aseptic packages’ convenience and affordability, largely among younger users.”47

A 1985 report noted that scientists in Reynolds’ flavour laboratory “create a beverage formula starting from our knowledge of flavours we already produce or have in our flavour library. We look for new and different combinations. Some work, others don’t, but all add to our bank of knowledge… Beverages appeal to consumers through a complex system of taste, smell and appearance. The ideal…is to leave people wanting more.”48 A 1985 analysis by Reynolds’ rival, Philip Morris, concluded:

Reynolds’ presence in virtually all aisles of the grocery store permit[ted] cross merchandising of brands in different sections of the store and different packaging forms. For example, Hawaiian Punch, part of the original RJR Foods, with annual sales of more than $200 million, has grown with the addition of sales through vending machines and, most recently, with aseptically packaged paper cartons. Historically, the food industry has been a manufacturing and distribution-driven business—with companies sticking to their packaging/technology and distribution path, be it canned or frozen. In our view, the successful companies of the future will develop brands with line extensions and merchandise them in all aisles of the store.49

Reynolds sold Hawaiian Punch to Procter & Gamble in 1990. The brand is currently owned by Dr Pepper Snapple, which continues to market the drink using Punchy.

Philip Morris in the sugary drinks market

Kool-Aid

General Foods purchased the Kool-Aid brand in 1953 from Perkins Products, which had marketed it as an inexpensive alternative to soda for families.50 51 In 1985, as part of its effort to diversify into the food and drink industry,52 53 54 Philip Morris acquired General Foods, including its Kool-Aid drink. A year later Philip Morris executives reported that marketing “has been pretty well balanced between appeals to mom and to the kids. We’ve decided to focus our marketing on kids, where we know our strength is the greatest. This year, Kool-Aid will be the most heavily promoted kids trademark in America.”55 56 Philip Morris cut Kool-Aid’s 1986-87 media spending on mothers in half (from $20.1m to $10.7m) and doubled the budget for children’s marketing (from $2.8m to $6m).57

The following year Philip Morris launched the $45m “Wacky wild Kool-Aid style” campaign featuring a redesigned Kool-Aid mascot—a giant anthropomorphic glass pitcher.58 The campaign was developed by Grey Advertising and aimed at 6-12 year olds.59 A Grey executive noted: “We discovered that if we had adults doing these slapstick reactions, falling on banana peels, wigs falling off, if we made adults look silly because they saw Kool-Aid Man and were shocked and frightened—the kids loved it because they were in control.”25 In 1993, Grey’s executive creative director said: “Kids want something of their own” and Kool-Aid’s brand image was “wacky and wild and fun and just for kids. The drink that’s just for kids.”25

Collaboration with Mattel and Nintendo led to branded toys, including Barbie and Hot Wheels.60 61 The Wacky Warehouse loyalty programme allowed children to redeem Kool-Aid purchases for gifts and sweepstakes. The director of Philip Morris’s beverage division described it as “our version of the Marlboro Country Store,”62 a 1972 cigarette loyalty programme.63 A 1992 Philip Morris analysis called the Kool-Aid Wacky Warehouse the “most effective kid’s marketing vehicle known.”64

Between 1986 and 2004, Philip Morris developed at least 12 new products of liquid and frozen Kool-Aid and 11 new flavour lines (supplementary tables C and D). Philip Morris added around 36 child tested flavours to the Kool-Aid line, with names such as Cherry Cracker and Kickin’ Kiwi Lime. Some integrated colours with cartoon characters, such as the “Great Bluedini,” sold under an octopus magician mascot. A Philip Morris executive noted: “A lot of adults may go, ‘Oh my God’ but the kids are really excited about it;” in market research, “kids simply say blue is cool.”65

Magic Twists and Mad ScienTwists featured colours that changed when mixed into water, about which Philip Morris’s category director noted, “Kids love colors and ‘twisted up’ flavour blends.”66

Philip Morris held “synergy” meetings to coordinate direct marketing across cigarette and other subsidiaries.67 Demographics, including children’s ages and household purchasing patterns, were compiled into a comprehensive consumer database used by all subsidiaries.68 Children were sent an exclusive six issue Marvel comics series, Adventures of Kool-Aid Man,53 and Philip Morris’s quarterly magazine, What’s Hot,69 featuring Kool-Aid brand images and giveaways (eg, Kool-Aid samples, made-to-order music tapes).64 What’s Hot had a circulation of two million in 1988.70

In 1993, Philip Morris sponsored cross-promotions and product tie-ins with toy manufacturers Mattel, Nintendo, and others to achieve the “ultimate kids’ promotion,” according to a senior brand manager.71 By 1998-2000, a multimillion dollar integrated promotion with Nickelodeon targeting 2-11 year olds 72 73 74 promoted “noggle goggles” (3-D glasses) and “smell-o-vision” (smell release cards), allowing children to engage with Kool-Aid man cartoon scenes on the television and internet.72 75 76 77 An integrated marketing campaign included simultaneous in-store displays, mailings, package inserts, and sponsorships (eg, Macy’s Thanksgiving parade) in a “fully integrated event across all the touch-points in a kid’s world,” according to Philip Morris’s marketing services director.74 76 78 She viewed smell-o-vision “as a benchmark to ‘raise the bar’ for future kids’ events” when it reached 95% of targeted 6-12 year olds.74

Capri Sun

In 1991, Philip Morris’s Kraft Foods subsidiary licensed the North American rights to Capri Sun79—a European fruit drink in a foil pouch with a straw insert that had been marketed in the US since 1981.80 81 82 83 84 Philip Morris rebranded it as an “all natural drink for kids in a cool pouch,” targeting 6-14 year olds.62 Philip Morris added bright colours and beach scenes on packaging to evoke “California cool.”80 85 In 1994, Philip Morris repositioned Capri Sun as a lunchbox drink, adding it to a Lunchables “fun pack” of prepackaged foods.86 Lunchables sales increased by 34% in 1994 and by 1998, exceeded $500m.62 87 88 89

Philip Morris’s 1995 campaign promoting Capri Sun featured surfers and skateboarders, along with in-pack premiums such as soccer magazines, mountain bike stickers, and in-store sweepstakes through collaborations with Trek (bicycles) and RollerBlade (in-line skates).80 90 New pouches carried sports themed holographic images.90 A 1995 article in Philip Morris’s Globe magazine credited “the brand’s growing success to a combination of unique packaging and imagery” because it “has a unique, leading edge image—very cool, sporty and outdoor active.”90 An 11 oz (325 mL) pouch, 67% larger, “aimed at teenagers” was launched in 2000.91

Tang

General Foods developed Tang in 1957. The orange flavoured drink powder, containing sugar, artificial colour, and vitamin C, was marketed to families for breakfast. Tang was popularised through its association with the US space programme.92 In 1992, under Philip Morris ownership, Tang products were repackaged from canister powder to foil pouches to “broaden their appeal by moving away from their image as ‘only’ a breakfast drink.”93 94 Tang’s media strategy had focused on mothers through daytime television, but after sales dropped 14% in 1995.95 Philip Morris executives refocused the brand on children aged 9-14 (tweens).”62

Tang was positioned as “a kick in the glass” for tweens deemed to be “too old for Kool-Aid, but too young for orange juice.”62 Promotions recast Tang as an “Extreme orange breakfast drink for today’s extreme tweens” in an innovative campaign starring live orangutans.62 Tang was relaunched in 1997 through media collaborations with DC Comics’ MAD Magazine, Sports Illustrated Jr, and in-store supermarket sweepstakes.96 Sports sponsorship by Major League Soccer 96 97 and Schwinn bicycles helped “build credibility with teens and pre-teens.”98 A 2000 “dream room” loyalty campaign included sweepstakes for Sony giveaways, which Philip Morris’s category business director said aimed to “reach out to tweens in a cool relevant way.”99

Philip Morris developed its sugary drink brands until 2007, when it spun off Kool-Aid, Capri Sun, and Tang under Kraft. Kool-Aid and Capri Sun remain with Kraft-Heinz in the US, but Tang is now licensed by Mondelēz worldwide and Kool-Aid by Coca-Cola in Europe. Kool-Aid and Capri Sun are still using the products and marketing campaigns (Kool-Aid Jammers, Capri Sun’s foil pouch with sports imagery) that Philip Morris developed.100 101

In 2017, Mondelez was still developing and selling new “fun filled” flavours in individual packets.102 The Mondelez International website advertises a Mumbai launch of a new Tang flavour sold with a convenient sipper bottle so that “Every child can quench his thirst this summer.”103

Policy implications

Both Reynolds and Philip Morris used cartoon mascots, child sized packaging technologies, and advertising messages found to appeal to children’s desire for autonomy, play, and novelty. Product lines included toy-like swizzle sticks, fizz tablets, fun bottles, and drinks that changed colour. New flavours with names like Purplesaurus Rex and Blastin’ Berry Cherry were formulated through numerous product tests on children. Marketing campaigns used cartoon characters that appealed to children’s aspirations, an approach also used to create brand loyalty to cigarettes104—for example, Reynolds’ use of Joe Camel to recruit young people to smoking.105 Tobacco companies also promoted their drinks using integrated marketing strategies that had been originally designed to sell cigarettes, surrounding children with consistent product messages in the home, store, school, sports stadium, and theme park.74

Litigation in the US resulted in the end of Joe Camel106 and legislation in 2009 prohibited use of cartoon characters to promote cigarettes.107 The 2003 World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control commits parties to prohibit or severely restrict marketing and to implement strong health warnings on tobacco products.108 In 2016, Chile became a global leader with its federal law introducing similar warning labels and strict marketing restrictions on child focused unhealthy foods and drinks.109 110 The law stipulates that food and drinks cannot be promoted to children with commercial “hooks” such as cartoon mascots.109 111 The re-negotiated North American Free Trade Agreement, signed in November 2018 by Canada, Mexico, and the US but not yet ratified,112 includes provisions that could be used to pre-empt (or at least delay and weaken) national and subnational measures to follow Chile’s model for front-of-package labelling within Canada, Mexico, and the US.113 114

With the exception of Dr Pepper Snapple, all current owners of the children’s beverage brands studied here have pledged participation in industry led voluntary agreements to limit the selective marketing of unhealthy drinks to children under 12. The industry argues that some of the marketing strategies developed by tobacco companies—including brand character toys, brand licensing on toys, and cartoon characters on packaging—are not actually targeting children and are therefore excluded from the agreement. The evidence cited here shows that these marketing techniques, which remain prevalent, were specifically designed to attract children by blurring advertisement with entertainment content in a way that is now at odds with the terms of industry led agreements. Voluntary industry codes are therefore unlikely to provide an adequate solution to the problem and we need well enforced government regulations.

Key messages.

Tobacco companies acquired soft drink brands to diversify

Industry documents show they applied marketing strategies aimed at children to develop the brands

Child friendly colours, flavours, and packaging and cartoon characters were used to promote products

Although the brands have been sold to food companies, the marketing techniques remain in use despite voluntary agreements not to advertise unhealthy products to children

Acknowledgments

We thank Claire Brindis, Cristin Kearns, Eric Crosbie, and Mark Pertschuk for advice, Steven Dominguez for help with copy editing, and the editors and reviewers of The BMJ for helpful suggestions.

Contributors and sources: All authors contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation. KHN and LS drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to revision for important intellectual content: KHN is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare that the work was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, CrossFit Foundation, and the US National Cancer Institute (CA 087472). The funders had no role in design, conduct, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet 2001;357:505-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04041-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1084-102. 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK, Chomitz VR, Ellenbogen SJ, Ludwig DS. Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatrics 2006;117:673-80. 10.1542/peds.2005-0983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DeBoer MD, Scharf RJ, Demmer RT. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in 2- to 5-year-old children. Pediatrics 2013;132:413-20. 10.1542/peds.2013-0570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Institute of Medicine In: Gootman JA, Kraak VI, eds. Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? National Academies Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Strategies to limit sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in young children: proceedings of a workshop—in brief. 2017. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2017/strategies-to-limit-sugar-sweetened-beverage-consumption-in-young-children-proceedings-in-brief.aspx. [PubMed]

- 7. Graff S, Kunkel D, Mermin SE. Government can regulate food advertising to children because cognitive research shows that it is inherently misleading. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:392-8. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization, UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health (TRS 916). 2003 http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/trs916/en/.

- 9. Foote SB, Mnookin RH. The “kid vid” crusade. Public Interest 1980;61:90-105. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pomeranz JL. Food law for public health. Oxford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30:211-25. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alderman J, Smith JA, Fried EJ, Daynard RA. Application of law to the childhood obesity epidemic. J Law Med Ethics 2007;35:90-112. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nestle M, Pollan M. Food politics : How the food industry influences nutrition and health. University of California Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beverage Industry. New nutrition criteria for children’s beverages. 2011. https://www.bevindustry.com/articles/84840-new-nutrition-criteria-for-childrens-beverages.

- 15.Better Business Bureau. About the initiative. 2017. https://www.bbb.org/council/the-national-partner-program/national-advertising-review-services/childrens-food-and-beverage-advertising-initiative/about-the-initiative/.

- 16. Nestle M. Soda politics: taking on big soda and winning. Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Friedman LC, Wadud A, Gottlieb M. Soda and tobacco industry corporate social responsibility campaigns: how do they compare? PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001241. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: Big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food? Milbank Q 2009;87:259-94. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surowiecki J. A big tobacco moment for the sugar industry. New Yorker 2016. Sep 15.https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/a-big-tobacco-moment-for-the-sugar-industry.

- 20.Altria Group. Distribution of Kraft Foods Class A common stock Altria Group,. shareholder tax basis information. 2007. http://www.altria.com/Documents/Kraft%20Spin-off%20Stockholder_Tax_Basis_Information%20-.pdf.pdf.

- 21. Elmore BJ. Citizen Coke: the making of Coca-Cola capitalism. W W Norton, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klara R. Perspective : Generation appreciation. Adweek 2011 Oct 13. http://www.adweek.com/brand-marketing/perspective-generation-appreciation-135561/.

- 23. Yoffie DB, Wang Y. Cola wars continue : Coke and Pepsi in 2006. Harvard Business School, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hafiz R. Rethinking brand identity to become an iconic brand—a study on Pepsi. Asian Business Review 2015;5:97-102 10.18034/abr.v5i3.60 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stabiner K. Get 'em while they’re young: With kid flavors, bright colors and commercials that make children masters of their universe, advertisers build brand loyalty that will last a lifetime. L A Times 1993 Aug 15. http://articles.latimes.com/1993-08-15/magazine/tm-35500_1_brand-loyalty.

- 26.Dreyfus C. The “Pepsi Generation” oral history and documentation collection. Smithsonian Institution, 1986. https://sova.si.edu/record/NMAH.AC.0111#summary.

- 27.Milton CH. R J Reynolds monthly research report. Technical development division. No 5. 29 May, 1962. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=tzgb0099.

- 28.Nielson ED. R J Reynolds. A proposed field of diversification—the production of flavoring agents. 4 Oct 1962. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hmxn0096.

- 29.R J Reynolds. Research and development letter from E D Nielson. 3 Oct 1969. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=pllj0075.

- 30.Milton CH. R J Reynolds monthly research report. Technical development division No 12. 3 Jan 1963. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jzfb0099.

- 31.Lynch M. R J Reynolds Industries: a Merrill Lynch Company report. 1983. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/srcv0101.

- 32.R J Reynolds. Catalog of marketing materials. 1996. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ymlv0103.

- 33.Gray B, Galloway AHRJ. Reynolds Tobacco Company annual report 1966. 1967. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mfhh0099.

- 34.Gray B, Galloway AHRJ. Reynolds Tobacco Company annual report 1968. February 6. 1969. Lorillard Records. Available at: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pghy0065.

- 35.Stokes C, Sticht JPRJ. Reynolds Industries, Inc. 1977 annual report. 1978. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/ghxh0099.

- 36.Galloway AH, Peoples DS. R J Reynolds. Annual report 1971. 1972. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hhxh0099.

- 37.Galloway AH, Peoples DS. R J Reynolds Industries 1970 annual report. 1970. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zmyk0056.

- 38.Galloway AH, Gray BRJ. Reynolds Tobacco Company 1967 1968. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nfhh0099.

- 39.R J Reynolds. Annual report 1969. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=pfhh0099.

- 40.R J Reynolds. Punchy is a different kind of sales force. 1973. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/txjl0005.

- 41.R J Reynolds. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company specialty advertising products. Joe Camel Collection.1977. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qgbh0097.

- 42.R J Reynolds. Caravan 1979;13. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nkpp0081.

- 43.R J Reynolds. Discoveries. April. 1977. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/njgf0083.

- 44.Peterson JR. R J Reynolds Industries presentation to security analysts. 8 Jun 1977. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/lrbl0096.

- 45.Winebrenner JT. Industries management twx. 15 Jul 1976. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xfdk0021.

- 46.R J Reynolds. RJR report. 1983;2(2). https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/lzkd0030.

- 47.R J Reynolds. Management presentations. 1 Nov 1984. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/sxll0081.

- 48.R J Reynolds. Report: first quarter 1985. 1985. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nxwv0087.

- 49.Miller TE. R J Reynolds marketing intelligence report. 22 Mar 1985. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nzgf0098.

- 50.Philip Morris. The Philip Morris history highlights. 1988. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=mqxb0145.

- 51.Kool-Aid Days. History of Kool-Aid. 2013. http://kool-aiddays.com/history/#sthash.6TzzOsco.dpbs.

- 52.Philip Morris. The Philip Morris history. 1988. Available at: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fsmh0128.

- 53. Moss M. Salt, sugar, fat : How the food giants hooked us. Random House, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.R J Reynolds. RJR 1984-1988 plan. November. 1983. Available at: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/rtpk0094.

- 55.Storr HG, Millington H. Philip Morris. First Boston beverage tobacco conference. April 1. 1987. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zzgb0112.

- 56.General Foods. General Foods '86. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/tyjf0021.

- 57.General Foods. USA advertising review 28 Sep 1987. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mxfw0117.

- 58.Philip Morris. Special edition advertising age. 27 Sep 1989. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=msfb0016.

- 59. Schor JB. Born to buy: the commercialized child and the new consumer cult. Simon and Schuster, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kool-Aid points 1980s & 90s. 2009 http://projectabsurd.com/koolaidpoints/koolaidpoints.htm.

- 61.Cavalcade of Awesome. A look back at the awesome swag from the Kool-Aid Wacky Warehouse. 2010. https://blog.paxholley.net/2010/02/02/a-look-at-the-awesome-swag-from-the-kool-aid-wacky-warehouse/.

- 62. Kraft Beverage Division Presentation, 19 Jun 1996. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zpmx0041.

- 63.Philip Morris. The Marlboro country store. 1972. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=kkkx0020.

- 64.Philip Morris. Phase 1 loyalty marketing exploration for Philip Morris. 19 Aug 1992. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fhfy0002.

- 65. Philip Morris FYI. 1993. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=spdn0039.

- 66.Philip Morris. Soft drink blends are red, right and blue. Philip Morris Globe 1998 Feb. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=qxpm0027.

- 67.Philip Morris. Synergy report. 5 Feb 1988. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=xpwj0106.

- 68.Shaw W, Kuendig J, Grund V. General Foods direct marketing review. 1987.: https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=lhll0025.

- 69.Philip Morris. FYI. 19 Jul 1989. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/nxhw0035.

- 70.Philip Morris. Quarterly directors report. June. 1988. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mkhk0045.

- 71.Philip Morris. Joint promotions make winners out of Kool-Aid tie-in partners. Philip Morris Globe 1993;8(5). https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/xnnh0041.

- 72.Pollack J. Kraft, BK link with Nickelodeon for $20 mil kid-oriented promo. 1998 http://adage.com/article/news/kraft-bk-link-nickelodeon-20-mil-kid-oriented-promo/65628/.

- 73.Mindykowski S. Marketing the rugrats 10th anniversary. 2000. http://www.animeexpressway.com/rugrats/rrat10a.htm.

- 74.Hood D. Kraft to untwist toons on ABC Disney block. 1999. http://kidscreen.com/1999/01/01/24097-19990101/.

- 75.Cheng K. Nickelodeon's nogglevision. 1997. http://ew.com/article/1997/10/03/nickelodeons-nogglevision/.

- 76.Smells like a winner. Chief Marketer 2000 May 1. http://www.chiefmarketer.com/smells-like-a-winner/.

- 77.Mind noggling. Chief Marketer 1999 Jul 1. http://www.chiefmarketer.com/mind-noggling/.

- 78. Hendershot H. Nickelodeon nation: the history, politics, and economics of America’s only TV channel for kids. New York University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Philip Morris. Board of directors of Philip Morris meeting minutes. 27 Nov 1991. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=qfkp0126.

- 80.Philip Morris. Minutes corporate products committee meeting. 24 Jun 1996. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/gpvb0077.

- 81.CapriSun. Who we are. 2017. http://www.capri-sun.com/en-de/who-we-are/.

- 82.A C Nielsen. Nielsen update ‘84. 1984. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=qpnw0053.

- 83.Lazarus G. Capri Sun bright offering for Kraft. Chicago Tribune 1991 Dec 20. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1991-12-20/business/9104240166_1_capri-sun-general-foods-usa-drink.

- 84.Philip Morris. The 1998-2002 five year plan. 1998. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/jlfg0175.

- 85.World B. A radical drink. [Business Article] 1991 [1 Dec 2017]; Available from: https://business.highbeam.com/138368/article-1G1-10916549/radical-drink.

- 86.Kraft Foods International. Kraft Foods International 1999-2003 strategic plan summary. 1999. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/klcd0218.

- 87.Philip Morris. 1998 annual report. 1999. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/njhj0223.

- 88.Philip Morris. Remarks by Jim Kilts Executive Vice President Worldwide Food Philip Morris Companies Inc. 1995. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/pfmk0177.

- 89.Philip Morris. Five year plan 1993-1997. 1993. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=kjjp0126.

- 90.Philip Morris. Capri Sun rises nationally as “cool” image boosts sales. Philip Morris Globe 1995 Jun. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hmmc0083.

- 91.Philip Morris. 2000 January board presentation. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=zjvp0177.

- 92. Smith AF. Food and drink in American history: a “full course” encyclopedia. United States ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Philip Morris. Annual meeting & first quarter report 1992. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=gghv0145.

- 94.General Foods. USA strategic plan. 1993. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=krkh0107.

- 95.Mehegan S. From space-age to teenage. 21 Oct 1997. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/qfwl0151.

- 96. Thompson S, Benezra K. Kraft continues Tang overhaul with Mad tie. Brandweek 1997;38:5. [Google Scholar]

- 97.MLS puts ad agencies in account shoot-out. Sports Business Daily 1996 Dec 10. http://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/Daily/Issues/1996/12/10/Sponsorships-Advertising-Marketing/MLS-PUTS-AD-AGENCIES-IN-ACCOUNT-SHOOT-OUT.aspx.

- 98.Adage. Kraft’s Tang gets sponsor deal. 1997. http://adage.com/article/news/kraft-s-tang-sponsor-deal/21979/.

- 99. Morris P. FYI. 2000. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=sxnb0057.

- 100.Kool-Aid. Kool-Aid. 2013 http://www.koolaid.com/.

- 101.CapriSun. Caprisun. 2016 http://parents.caprisun.com/.

- 102.Mondelēz International. 2017 fact sheet Tang. http://www.mondelezinternational.com/~/media/MondelezCorporate/Uploads/downloads/tang_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

- 103.Mondelēz International. Get refreshed with the delicious all new Apple Tang this summer. 2015 https://in.mondelezinternational.com/newsroom/getrefreshedwiththedeliciousnewappletang.

- 104. United States Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults. A report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Coughlin P, Janecek F Jr, Milberg W, et al. A review of R.J. Reynolds' internal documents produced in Mangini vs. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, civil number 939359— The case that rid California and the American landscape of "Joe Camel." 1998. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Mangini_report.pdf.

- 106.Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corporation, Eller Media Corporation, Lorillards, Outdoor Systems, Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co, Janet C. Mangini. Settlement agreement and release 1998. https://www.industrydocumentslibrary.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/zkjd0069

- 107.US Department of Health & Human Services. Family smoking prevention and tobacco control and federal retirement reform. 2009. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ31/pdf/PLAW-111publ31.pdf.

- 108.World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2003. http://www.who.int/fctc/cop/about/en/.

- 109.Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile/ BCN. Sobre composición nutricional de los alimentos y su publicidad. 2015. https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1041570&idVersion=2015-11-13.

- 110.International Trade Administration, US Department of Commerce. Chile labeling and marketing requirements. 2017. https://www.export.gov/article?id=Chile-Labeling-Marking-Requirements

- 111.Hunter College New York City Food Policy Center. Chile banishes cartoon mascots from supermarket shelves. 2018. http://www.nycfoodpolicy.org/chile-banishes-cartoon-mascots-supermarket-shelves/.

- 112.Office of the United States Trade Representative. Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada 2018. https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/agreement-between

- 113.Ahmed A, Richtel M, Jacobs A. In Nafta talks, US tries to limit junk food warning labels. New York Times 2018 Mar 20. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/20/world/americas/nafta-food-labels-obesity.html.

- 114. Crosbie E, Gonzalez M, Glantz SA. Health preemption behind closed doors: trade agreements and fast-track authority. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e7-13. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]