Abstract

Background:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) microelimination efforts must target people in prison; however, although some inmates may qualify for treatment in provincial prisons, it may not be routinely provided. Our aim was to characterize the cascade of HCV care in Quebec’s largest provincial prison.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study of all HCV-related laboratory tests requested at the Établissement de détention de Montréal (men’s prison with on-demand screening), between July 1, 2017, and June 30, 2018. We defined 8 HCV care cascade steps: 1) total sentenced inmates, 2) screened for HCV (via HCV antibody [HCV Ab]), 3) HCV Ab positive, 4) tested for HCV RNA, 5) HCV RNA positive, 6) linked to care, 7) HCV treatment initiated and 8) achieved sustained virologic response. We measured proportions of inmates at each step using denominator–numerator linkage. We also calculated the proportion screened among inmates with a sentence duration of at least 1 month, during which time screening should be feasible.

Results:

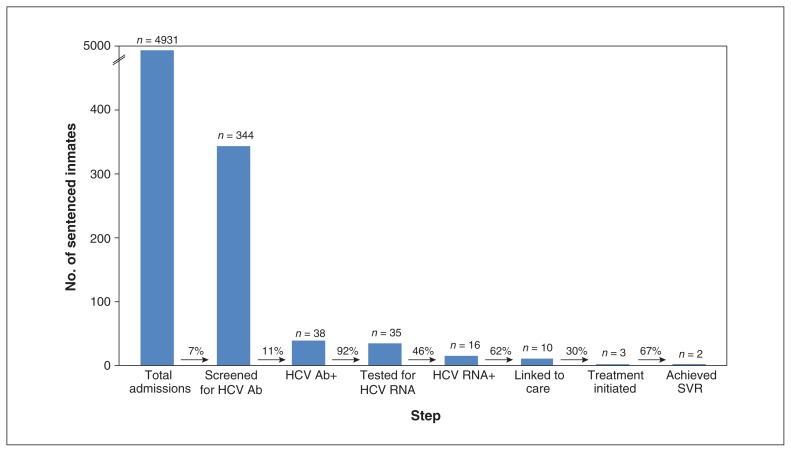

Of the 4931 sentenced inmates, 344 (7%) were screened for HCV, of whom 38 (11%) were HCV Ab positive. Thirty-five (92%) of the 38 received HCV RNA testing, which showed positivity in 16 (46%). Ten (62%) of the 16 inmates were linked to care; treatment was initiated in 3 (30%), 2 of whom (67%) achieved a sustained virologic response. Among inmates with a sentence duration of at least 1 month (n = 1972), the proportion screened increased to 17%.

Interpretation:

A small proportion (7%) of men at a Canadian provincial prison with on-demand HCV testing were screened, and rates of treatment initiation were low in the absence of formal HCV cure pathways. To eliminate HCV in this subpopulation, opt-out HCV testing should be considered.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the leading cause of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and transplantation worldwide.1,2 In Canada, HCV infection causes more years of life lost than any other infectious disease.3,4 Provided that highly effective direct-acting antiviral treatment can be expanded, HCV-related sequelae will likely become less frequent over time. Unfortunately, this may not be the case for people who are incarcerated, who are known to have lower rates of uptake of treatment for HCV infection in Canada despite a 40-fold greater prevalence of HCV (HCV Ab) (which indicates previous exposure) compared to the general population.5–7 Access to direct-acting antivirals for those currently or previously incarcerated not only would have individual-level benefits but also could potentially decrease onward transmission in these highly mobile populations, where harm-reduction interventions are not necessarily available. Decreased treatment uptake among inmates is multifactorial. At the system level, it is likely due to absent systematic screening programs in most provincial correctional facilities, resulting in fewer identified cases, as well as a lack of standardized procedures needed to facilitate treatment uptake during incarceration or linkage to HCV care following release for inmates whose sentences are too short to complete treatment during incarceration.8,9 Although Canada is committed to eliminating HCV infection by 2030, in failing to address the HCV epidemic among people in Canadian provincial prisons — where the majority of Canadian inmates are serving sentences — Canada will never reach this goal.10,11

The cascade of HCV care describes successive health care steps specific to chronic HCV infection that result in optimal health outcomes.12 Screening, the first step of the cascade, lays the foundation for subsequent linkage to care, initiation of treatment and achievement of cure. Although the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver, the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C and the World Health Organization recommend HCV screening for all people who experience imprisonment, with the exception of British Columbia, all provincial correctional facilities provide testing primarily on request.13–16 Furthermore, the recently released Blueprint to Inform Hepatitis C Elimination Efforts in Canada stipulates that HCV infection treatment or linkage to care on release for those with shorter sentences be provided to all inmates.15 Federal inmates, who have been sentenced to time in custody of 2 years or more, can progress from screening to cure during incarceration.17 However, as a result of shorter sentences in provincial prisons (median 28 d), achieving all cascade steps before release can be challenging,18 and, although some inmates may qualify for treatment in this setting, it may not be routinely provided.9 We aimed to characterize the HCV care cascade among people in Quebec’s largest provincial prison, the Établissement de détention de Montréal.

Methods

Setting

The Établissement de détention de Montréal, also known as Bordeaux, is the largest of 16 provincial prisons in Quebec, with a maximum capacity of 1357 men (> 18 yr).19 In Quebec, the Ministry of Health is responsible for the majority of provincial prison-based nursing services. At the Établissement de détention de Montréal, Ministry of Health nurses are mandated to screen and treat sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections, including HCV infection. “On demand” HCV screening — that is, testing requested by inmates — is available at the majority of provincial prisons in the province, including the Établissement de détention de Montréal. Tests for HCV Ab and RNA are performed via venipuncture, with estimated turnaround times of 24 hours and 21 days, respectively, at the Établissement de détention de Montréal (Joëlle Bianco, Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Nord-de-l’Île-de-Montréal: personal communication, 2019). Confirmatory testing for chronic HCV infection via HCV RNA is attempted in all inmates who are HCV Ab positive. All inmates with chronic HCV infection are offered liver disease assessments by off-site HCV care providers before treatment initiation and are systematically informed of treatment options as part of routine posttest counselling; there are no on-site physicians with HCV expertise at the Établissement de détention de Montréal. Treatment with direct-acting antivirals may be initiated for inmates who serve sentences longer than 12 weeks to ensure that treatment is completed during incarceration. Treatment uptake is further dependent on inmate interest and clinical urgency (i.e., presence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis). Treatment is typically postponed until release for inmates serving sentences shorter than treatment duration. In such cases, outpatient follow-up appointments with HCV care providers are scheduled by Ministry of Health nurses before release.

Design

We conducted a retrospective study of all HCV-related laboratory tests requested by Établissement de détention de Montréal inmates between July 1, 2017, and June 30, 2018. We chose this period following a transitional period in early 2017; thereafter, 2 Ministry of Health nurses with time dedicated to screening for sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections were available.

We adapted the cascade of HCV care, which consists of 8 steps, to the correctional setting as follows: 1) total sentenced inmates, 2) screened for HCV, 3) HCV Ab positive (indicative of previous exposure), 4) tested for HCV RNA, 5) HCV RNA positive (indicative of chronic HCV infection), 6) linked to care, 7) HCV treatment initiated and 8) achieved sustained virologic response (indicative of cure) (Table 1). We defined “screened for HCV” as the number of inmates who requested on-demand HCV screening (via an HCV Ab test) during the study period, “HCV Ab positive” as the number of inmates with at least 1 confirmed positive HCV Ab test result, and “tested for HCV RNA” as the number of HCV-Ab–positive inmates who had at least 1 HCV RNA test to confirm chronic HCV infection. We assumed that any inmate who underwent HCV RNA testing as the first screening test was already known to have been exposed to HCV and thus also contributed data to steps 2 and 3. We defined “HCV RNA positive” as the number of inmates with at least 1 confirmed positive HCV RNA test result, “linked to care” as the number of inmates with chronic HCV infection who were assessed by an off-site HCV care provider, “HCV treatment initiated” as the number of inmates with chronic HCV infection who started HCV treatment with direct-acting antivirals during incarceration, and “achieved sustained virologic response” as the number of inmates who were HCV RNA negative 12 weeks after the end of treatment.

Table 1:

Steps of the hepatitis C virus care cascade

| Step | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1. Total sentenced inmates | Total number of sentenced inmates during the study period |

| 2. Screened for HCV | Number of inmates who requested on-demand HCV screening (via HCV Ab test) |

| 3. HCV Ab positive | Number of inmates with at least 1 confirmed positive HCV Ab test result |

| 4. Tested for HCV RNA | Number of HCV-Ab–positive inmates with at least 1 HCV RNA test |

| 5. HCV RNA positive | Number of inmates with at least 1 confirmed positive HCV RNA test result, indicating chronic HCV infection |

| 6. Linked to care | Number of inmates assessed by off-site HCV care provider |

| 7. HCV infection treatment initiated | Number of inmates who started HCV infection treatment during incarceration |

| 8. Achieved sustained virologic response | Number of inmates who were HCV RNA negative 12 weeks after the end of treatment, indicating cure |

Note: HCV = hepatitis C virus, HCV Ab = hepatitis C virus antibody.

Sources of data

We obtained deidentified individual-level laboratory data for steps 2–5 from Sacré-Coeur Hospital’s OPTILAB information system. We cleaned the data by removing duplicates and ensured that each individual had a unique identifier; in addition, data for reincarcerated inmates were considered to contribute to the cascade only once. Ministry of Health nurses were then provided with nonnominal identifiers to determine linkage, treatment initiation and cure rates (i.e., steps 6–8) using the Établissement de détention de Montréal health records. Owing to the highly confidential nature of inmate data, individual-level data were restricted to age and HCV care parameters.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the proportion of inmates at each step of the HCV care cascade using denominator–numerator linkage, whereby data are linked at the individual level within each step, and people eligible for being in the numerator in a given step are the same people in the denominator of the subsequent step.20 We then calculated the proportion screened among inmates sentenced for at least 1 month (estimated to be 40% of the total number of sentenced inmates), during which time screening and confirmatory testing should be feasible. 18 All analyses were performed in R 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre Research Ethics Board and the director of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux du Nord-de-l’Île-de-Montréal.

Results

Of the 493121 sentenced inmates (median age 35 yr) between July 2017 and June 2018, 344 (7%) were screened for HCV, of whom 38 (11%) were HCV Ab positive (Figure 1). Thirty-five (92%) of the 38 received HCV RNA testing, which showed positivity in 16 (46%). Ten (62%) of the 16 inmates were linked to care; treatment was initiated in 3 (30%), 2 of whom (67%) achieved a sustained virologic response. Of the 6 inmates who were not linked to care, 3 refused, and 3 were released before their HCV care appointment was scheduled. Of the 7 inmates in whom treatment was not initiated, 3 were serving sentences shorter than HCV treatment duration and were therefore denied therapy, 2 refused, 1 was transferred to another correctional facility, and 1 died from a cause unrelated to HCV. One inmate had not yet completed treatment and therefore had not met the time point for a sustained virologic response. Restricting the analysis to inmates with a sentence duration of at least 1 month (n = 1972) increased the proportion of inmates screened for HCV to 17%.

Figure 1:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) care cascade among all sentenced inmates. Note: HCV Ab = hepatitis C virus antibody, SVR = sustained virologic response.

Interpretation

Our study retrospectively identified that the major bottleneck for engagement in HCV care for men incarcerated in a large Canadian provincial prison was screening. The screening rate in the presence of on-demand screening was low. The prevalence of HCV Ab positivity, 11%, reflects that in a recent provincial biobehavioural study.22 Confirmatory HCV RNA tests were performed in most inmates with evidence of previous HCV exposure. Conversely, during the 1-year study period, only 10 inmates were linked to care, and HCV treatment was started in only 3. These low numbers likely reflect absent formalized HCV cure pathways, as well as deficient follow-up procedures for chronically infected inmates after release, shortcomings that are unlikely unique to the Établissement de détention de Montréal. The reasons identified for low rates of linkage and treatment uptake included refusals, short sentences and prison transfers — all in keeping with other studies and representing unique challenges for HCV care in prison settings.23,24

To improve HCV screening at the Établissement de détention de Montréal and other Canadian provincial prisons, systematic opt-out screening should be considered.5 Admission to any correctional facility provides an important public health opportunity to identify cases of chronic HCV infection through screening, and, as all subsequent cascade steps are dependent on this initial step, implementing systematic screening at admission and during incarceration is imperative. 25 Rates of screening for HCV in other Canadian provincial prisons are unknown. However, with the exception of British Columbia (where an opt-out screening approach is used), the majority of provincial correctional facilities provide testing only on request, which suggests that similarly low screening rates would be expected in the remainder of Canadian provincial prisons. Despite the low screening rates, with on-site nursing, we found that a high proportion of HCV-Ab–positive inmates underwent appropriate HCV RNA testing to confirm chronic infection. This is in keeping with a recent systematic literature review that showed that on-site HCV testing with nurse-led education and counselling had the greatest impact on HCV screening rates.26 Conversely, over one-third of inmates with chronic HCV infection in the current study were not linked to care, with half being released before their HCV care appointment was scheduled. Shortening the time to HCV RNA testing could help rectify this situation. The Xpert HCV viral load finger-stick point-of-care assay (Cepheid) can diagnose active HCV infection in a single visit, with a turnaround time of 1 hour;27 however, it is not yet approved in Canada. This is particularly relevant for correctional facilities whose inmates serve short sentences, as is the case in Canadian provincial/territorial prisons and US jails. Given that provincial prisons’ budgets are limited, our findings suggest that continuing to use on-demand screening approaches will fail to identify an important subpopulation who drive the current Canadian HCV epidemic and who are key to HCV microelimination.9

To improve engagement along the HCV care cascade, the Établissement de détention de Montréal and other Canadian provincial prisons should explore strategies to increase access to HCV infection treatment. Prioritizing the treatment of all provincial inmates who remain in custody long enough to allow for completion of direct-acting antiviral therapy is a reasonable first step.15 Although this may involve a minority of inmates, it is a practical approach given the lower rates of sustained virologic response among inmates in whom treatment is started but who are subsequently transferred or released.28 We found that, among those who served sentences long enough to complete therapy, there remained a substantial proportion who refused to be assessed for or to start treatment. Although refusal is not uncommon in prison settings, a recent qualitative study showed that adopting a patient-centred treatment approach, whereby privacy is assured and social support is provided, may enhance uptake of treatment for HCV infection among people in prisons.29 In addition, correctional facilities could facilitate linkage with on-site (rather than off-site) physicians or other qualified health care personnel in order to reduce delays between diagnosis and treatment initiation. For the majority who will not serve sufficiently long sentences, both ensuring receipt of any HCV care during incarceration and facilitating referral to an HCV care specialist through appointment scheduling have been shown to improve linkage to care following release.26,30,31 However, both measures would be possible only in the presence of dedicated, trained personnel, which, again, may not always be the case in many correctional facilities. Furthermore, establishing corridors of service with primary or tertiary care centres would help ensure the availability of dedicated physicians and timely follow-up appointments. Canadian provincial prisons have generally provided very little support during the period of transition from prison to community,8,9 and, although primary care may be better suited to address some of these challenges, postincarceration transition clinics have also emerged as models of care to address these issues in a culturally appropriate manner.32,33

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the cascade of HCV care was adapted to the correctional setting, as evidenced by the first step (total sentenced inmates). Second, the results are limited to a single year at a single provincial prison for men in Quebec. As such, the results may be generalizable only to other Canadian provincial prisons with both on-demand HCV screening and nursing personnel dedicated to HCV care. Our results may also not be generalizable to women’s or mixed-gender provincial prisons. Third, as sentence durations were unknown, we may have underestimated the proportion of inmates who progressed along the HCV care cascade owing to short sentences. Although we attempted to address this limitation with our secondary analysis, whereby we ensured sufficient sentence duration to allow for screening, this was impossible to do for the steps after detection of HCV RNA positivity (linkage to care, treatment initiation and sustained virologic response). Therefore, right censoring of the data is expected without this consideration. Future cascade work could investigate the role of sentence duration on cascade reporting, which would allow for more accurate documentation of improved engagement in HCV care among inmates over time. Finally, although we used individual-level data, we were unable to better understand progression (or lack thereof) along the HCV care cascade based on sociodemographic information or liver disease status owing to restrictions on inmate data. This limitation underscores the unique challenges that exist when conducting scientifically rigorous research in correctional settings and advocates for improved transparency with health research and research ethics in prisons.

Conclusion

We found substantial missed opportunities for engagement in HCV care for inmates in Quebec’s largest provincial prison in the presence of an on-demand screening strategy and despite dedicated nursing services. Correctional Service Canada has taken monumental steps toward microelimination of HCV in federal facilities through systematic screening and universal access to HCV treatment; however, similar provincial commitments have lagged, likely driven by short sentences and high turnover rates. Prison settings represent unique environments for the initiation of HCV care. Failing to adopt systematic opt-out screening as a first step, as was done in federal facilities, may have not only important individual-level health outcomes but also consequences for public health in Canada. Moving forward, we must engage with all relevant stakeholders, from policy-makers to the community, in order to prioritize people in provincial prisons in the national HCV elimination agenda.

Appendix

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge and thank Martin Boily, Nathalie Perreault, Joëlle Bianco and Hélène Rodrigue for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Nadine Kronfli reports grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network, a grant for an investigator-initiated study from Gilead Sciences and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Gilead Sciences and Merck, outside the submitted work. Marina Klein reports grants from the CIHR, the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network, the Réseau Sida et maladies infectieuses du Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé and the National Institutes of Health, grants for investigator-initiated studies from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Merck and Janssen, and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences and Merck, outside the submitted work. Bertrand Lebouché reports grants from Merck, Gilead Sciences and AbbVie, and personal fees from Merck, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. Giada Sebastiani reports grants from Merck, Gilead Sciences and AbbVie, and personal fees from Merck, Gilead Sciences, AbbVie and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. Joseph Cox reports grants and personal fees from ViiV Global, Gilead Sciences and Merck Canada, outside the submitted work. He was a site principal investigator for a randomized controlled trial of bictegravir (Biktarvy, Gilead Sciences). No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Nadine Kronfli, Camille Dussault and Joseph Cox were involved in study conceptualization and design. Nadine Kronfli and Camille Dussault analyzed and interpreted the data. Nadine Kronfli drafted the manuscript. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: Bertrand Lebouché received salary support from the Fonds de la Recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS) and the Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec. Giada Sebastiani received salary support from the FRQS. Nadine Kronfli is also supported by a salary award from the FRQS (Junior-1).

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E674/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Myers RP, Liu M, Shaheen AA. The burden of hepatitis C virus infection is growing: a Canadian population-based study of hospitalizations from 1994 to 2004. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:381–7. doi: 10.1155/2008/173153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers RP, Krajden M, Bilodeau M, et al. Burden of disease and cost of chronic hepatitis C infection in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28:243–50. doi: 10.1155/2014/317623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schanzer DL, Paquette D, Lix LM. Historical trends and projected hospital admissions for chronic hepatitis C infection in Canada: a birth cohort analysis. CMAJ Open. 2014;2:E139–44. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20130087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwong JC, Ratnasingham S, Campitelli MA, et al. The impact of infection on population health: results of the Ontario Burden of Infectious Diseases Study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronfli N, Nitulescu R, Cox J, et al. Decreased hepatitis C treatment uptake among HIV–HCV co-infected patients with a history of incarceration. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21:e25197. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trubnikov M, Yan P, Archibald C. Estimated prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Canada, 2011. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2014;40:429–46. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v40i19a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challacombe L. The epidemiology of hepatitis C in Canada. Toronto: Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange (CATIE); 2019. [accessed 2019 Apr 14]. Available: www.catie.ca/en/fact-sheets/epidemiology/epidemiology-hepatitis-c-canada. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kronfli N, Cox J. Care for people with hepatitis C in provincial and territorial prisons. CMAJ. 2018;190:E93–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.171142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronfli N, Buxton J, Jennings L, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) care in Canadian correctional facilities: Where are we and where do we need to be? Can Liver J. 2019 June 12; doi: 10.3138/canlivj.2019-0007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030: advocacy brief. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [accessed 2019 Apr 14]. Available: www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hep-elimination-by-2030-brief/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill AM, Nath S, Simmons B. The road to elimination of hepatitis C: analysis of cures versus new infections in 91 countries. J Virus Erad. 2017;3:117–23. doi: 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30329-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linas BP, Barter DM, Leff JA, et al. The hepatitis C cascade of care: identifying priorities to improve clinical outcomes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grad R, Thombs BD, Tonelli M, et al. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on hepatitis C screening for adults. CMAJ. 2017;189:E594–604. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah H, Bilodeau M, Burak KW, et al. Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. The management of chronic hepatitis C: 2018 guideline update from the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver. CMAJ. 2018;190:E677–87. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blueprint to inform hepatitis C elimination efforts in Canada. Montréal: Canadian Network on Hepatitis C Blueprint Writing Committee and Working Groups; 2019. [accessed 2019 Aug 6]. Available: www.canhepc.ca/sites/default/files/media/documents/blueprint_hcv_2019_05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis C infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [accessed 2019 Apr 14]. Available: www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-c-guidelines-2016/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster P. Dramatic budget increase for hepatitis treatment in federal prisons. CMAJ. 2017;189:E1052. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1095468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reitano J. Adult correctional statistics in Canada, 2015/2016 [juristat] Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. [accessed 2019 Apr 14]. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14700-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Direction générale des services correctionnels – 01.02. Québec: Ministère de la Sécurité publique; 2016. [accessed 2019 Apr 14]. Question 50: La capacité d’accueil, le taux d’occupation, les coûts per diem, les dépenses et les crédits alloués pour chaque établissement de détention pour la période 2015–2016. Available: www.securitepublique.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/Documents/ministere/diffusion/documents_transmis_acces/2016/119707.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haber N, Pillay D, Porter K, et al. Constructing the cascade of HIV care: methods for measurement. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11:102–8. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Direction générale des services correctionnels – 0102. Québec: Ministère de la Sécurité publique; 2018. [accessed 2019 Oct 16]. Étude des crédits 2018–2019 demande de renseignements particuliers Tome 1. Available: https://www.securitepublique.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/Documents/ministere/diffusion/etude_credit_2018-2019_Reponses_particuliers_tome1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courtemanche Y, Poulin C, Serhir B, et al. Étude de prévalence du VIH et du VHC chez les personnes incarcérées dans les établissements de détention provinciaux au Québec. Québec: Institut national de santé publique du Québec; 2016. [accessed 2019 Apr 14]. Available: www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/itss/rapport_vih_vhc_milieu_carceral.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap L, Carruthers S, Thompson S, et al. A descriptive model of patient readiness, motivators, and hepatitis C treatment uptake among Australian prisoners. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vroling H, Oordt-Speets AM, Madeddu G, et al. A systematic review on models of care effectiveness and barriers to hepatitis C treatment in prison settings in the EU/EEA. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:1406–22. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He T, Li K, Roberts MS, et al. Prevention of hepatitis C by screening and treatment in U.S. prisons. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:84–92. doi: 10.7326/M15-0617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kronfli N, Linthwaite B, Kouyoumdjian F, et al. Interventions to increase testing, linkage to care and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among people in prisons: a systematic review. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;57:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lamoury FMJ, Bajis S, Hajarizadeh B, et al. LiveRLife Study Group. Evaluation of the Xpert HCV viral load finger-stick point-of-care assay. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:1889–96. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aspinall EJ, Mitchell W, Schofield J, et al. A matched comparison study of hepatitis C treatment outcomes in the prison and community setting, and an analysis of the impact of prison release or transfer during therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:1009–16. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lafferty L, Rance J, Grebely J, et al. Understanding facilitators and barriers of direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection in prison. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:1526–32. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochstatter KR, Stockman LJ, Holzmacher R, et al. The continuum of hepatitis C care for criminal justice involved adults in the DAA era: a retrospective cohort study demonstrating limited treatment uptake and inconsistent linkage to community-based care. Health Justice. 2017;5:10. doi: 10.1186/s40352-017-0055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tait JM, McIntyre PG, McLeod S, et al. The impact of a managed care network on attendance, follow-up and treatment at a hepatitis C specialist centre. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:698–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang EA, Hong CS, Samuels L, et al. Transitions clinic: creating a community-based model of health care for recently released California prisoners. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:171–7. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawks L, Norton BL, Cunningham CO, et al. The hepatitis C virus treatment cascade at an urban postincarceration transitions clinic. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:473–8. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.