Abstract

Intracontinental biotic divisions across the vast Palaearctic region are not well-characterized. Past research has revealed patterns ranging from a lack of population structure to deep divergences along varied lines of separation. Here we compared biogeographic patterns of two Palaearctic shorebirds with different habitat preferences, Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) and Eurasian curlew (N. arquata). Using genome-wide markers from populations across the Palaearctic, we applied a multitude of population genomic and phylogenomic approaches to elucidate population structure. Most importantly, we tested for isolation by distance and visualized barriers and corridors to gene flow. We found shallow Palaearctic population structure in subpolar bog and tundra-breeding whimbrels, consistent with other species breeding at a similarly high latitude, indicating connectivity across the tundra belt, both presently and during southward shifts in periods of global cooling. In contrast, the temperate grassland-breeding Eurasian curlew emerged in three distinct clades corresponding to glacial refugia. Barriers to gene flow coincided with areas of topographic relief in the central Palaearctic for whimbrels and further east for Eurasian curlews. Our findings highlight the interplay of historic and ecological factors in influencing present-day population structure of Palaearctic biota.

Subject terms: Molecular ecology, Ecological genetics, Biogeography

Introduction

Extreme climatic events in the Earth’s recent past have played an important role in shaping population genetic structure of animals1,2. It is surmised that the impact of Quaternary climate oscillations on biogeography differs according to a suite of variables, such as latitude and topography2. During cyclical periods of global cooling, the formation of barriers has facilitated intercontinental biotic differentiation as revealed by traditional DNA markers3–7. While intra-continental population structure is equally impacted by Quaternary climate oscillations, it has not been studied as intensely, with most research focusing on North America and Europe8–11. The Nearctic and Palaearctic, both large northern hemispheric landmasses, are characterized by a zoogeographical division into an eastern and a western sub-region. The boundary between North America’s sub-regions runs along a suture zone through the center of the Great Plains and has been well described12–20. In the Palaearctic, a vast zoogeographic region stretching across the world’s most sizeable landmass, Eurasia21,22, the large-scale division into western and eastern sub-regions has long been established based on the distinct faunal elements present on either side23,24. However, resolution of the boundary of these two sub-regions across biota has so far eluded biogeographers.

Novel population genomic approaches relying on massive panels of genome-wide loci afford an opportunity to identify intra-Palaearctic barriers and contrast them among different species. The last two decades have seen an increase in molecular studies on population genetic divisions of wide-ranging species complexes, revealing a variety of phylogeographic patterns traversing the Palaearctic25–28. Population genetic inquiries on many vertebrates29–31, especially songbirds3,25,28,32–35, and invertebrates36,37 have revealed a primary divide between Far-Eastern populations (east of Lake Baikal to Japan) and the much more expansive western and central Palaearctic populations. An alternative dividing line within wide-ranging Palaearctic species has been proposed further west in the Central Palaearctic27,28,38,39. In other studies, Palaearctic populations have also been characterized by divisions into multiple clusters corresponding to glacial refugia during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)40,41. Conversely, some wide-ranging species lack or show only shallow population structure despite the vast geographical area involved9,25,28,31,42–44. Explanations for these phylogeographic patterns often invoke geographical features and environmental conditions both presently and historically44, which interact with life-history traits such as dispersal capability9, natal homing45, prey availability42, non-breeding habitat preference46, mating system47–49 as well as the evolutionary history unique to each species28. This complicated interplay of factors accounts for substantial variability in the boundary between eastern and western Palaearctic population units across species.

There continues to be a dearth of comparative research on Palaearctic biota across different habitat types to help shed light on the historic mechanisms that have shaped their evolutionary histories2. In this study, we used thousands of genome-wide markers to elucidate fine-scale population structure across the Palaearctic in two migratory shorebirds – the whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus Linnaeus, 1758) and Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata Linnaeus, 1758). The Eurasian curlew breeds in temperate grassy mires and wet meadows, with a relatively short-distance migratory behavior. Contrarily, the whimbrel generally breeds in extensive bogs in woodlands and tundra of subpolar latitudes, predominantly wintering at (sub-)tropical latitudes (Fig. 1a). An exception is the steppe whimbrel, N. p. alboaxillaris, which breeds in wet grasslands in steppe valleys sympatrically with Eurasian curlew. Both species are polytypic, ranging from the western to eastern Palaearctic and exhibiting intraspecific plumage variation. In both species, populations breeding in the South Urals (steppe whimbrel and steppe curlew, N. a. suschkini) are phenotypically distinct as the palest taxa50–53. By comparing the phylogeography between two congeneric shorebird species with a similar biology but important differences in breeding habitat, we aim to shed light on habitat-specific effects of Quaternary climate oscillations on biotic differentiation across the Palaearctic.

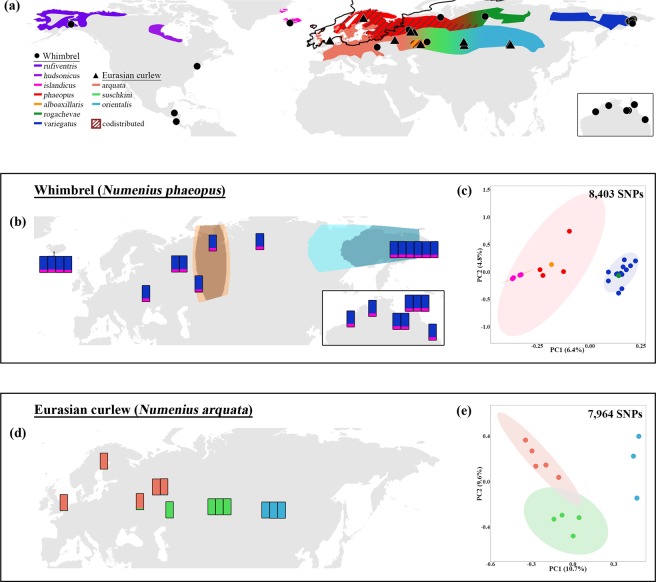

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of breeding areas and sampling localities of whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) and Eurasian curlew (N. arquata). Each circle or triangle symbol represents a sampled individual. The black lines across Europe represent the maximum extent of the European ice sheet at the last glacial maximum70. (b) Coloured bars represent Structure results at K = 2 for Palaearctic whimbrels. Each bar represents the results for an individual at its approximate sampling locality. Orange and blue polygons represent barriers and corridors to gene flow, respectively, as identified by EEMS. Dark and light shades represent posterior probabilities of >0.95 and >0.90, respectively. The inset shows the results for whimbrels sampled from Australia. (c) Principal component (PC) analysis of Palaearctic whimbrels, with percentage of variation of the two most important PCs. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals. Due to low sample size, no ellipses were calculated for N. p. alboaxillaris, and rogachevae. Colours correspond to the breeding populations in (a). (d) Coloured bars represent Structure results at K = 3 for Eurasian curlews. Each bar represents the results for an individual at its approximate sampling locality. No significant barriers or corridors were identified by EEMS. (e) PC analysis of Eurasian curlews, with percentage of variation of the two most important PCs. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals. Due to low sample size, no ellipses were calculated for N. a. orientalis. Colours correspond to the breeding populations in (a).

Results

Sequencing and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) harvest

A total of 54 double digest restriction-site associated DNA sequencing (ddRADseq) libraries spanning 38 whimbrels, 15 Eurasian curlews and one common redshank were successfully prepared (see Supplementary Table S1), amounting to a total of 162,836,371 paired-end 150 bp Illumina sequence reads. Thirteen samples (10 whimbrels and 3 Eurasian curlews) were excluded from downstream analysis due to low coverage or more than 25% missing data. We obtained between 400,000–17,000,000 reads per individual and harvested between 6,500–8,500 SNPs across population genomic datasets (see Supplementary Table S2). We obtained 438,477 bp of data for phylogenomic analysis of all whimbrels.

Whimbrel phylogeography

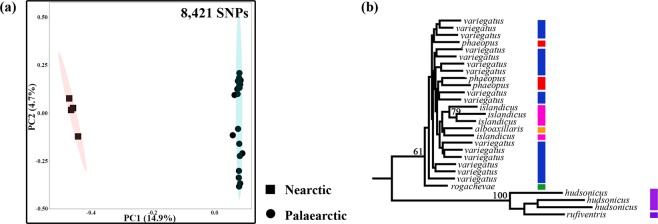

Palaearctic whimbrels formed a well separated cluster from Nearctic whimbrels (Fig. 2a). Phylogenetic analysis also showed that Nearctic whimbrels formed a deep monophyletic clade with high bootstrap support (100%) (Fig. 2b). In summary, analysis across all whimbrel individuals (n = 28) revealed two distinct monophyletic groups comprising Nearctic versus Palaearctic populations.

Figure 2.

(a) Principal component (PC) analysis of all whimbrels, with percentage of variation for the two most important PCs, including Nearctic (N. p. hudsonicus and rufiventris) and Palaearctic (N. p. phaeopus, islandicus, alboaxillaris, rogachevae and variegatus) populations. Ellipses represent 95% confidence intervals. (b) Maximum likelihood tree of all whimbrels using 438,477 bp of sequence data. Only bootstrap support >50 is displayed. Colours of the bars at the terminal ends of branches correspond to the breeding populations in Fig. 1a.

Within Palaearctic whimbrels, no noticeable geographic differentiation was apparent in Structure analysis at any values of K ranging from K = 1 to 8 (Fig. 1b; see Supplementary Fig. S1). This uniformity suggests that Palaearctic whimbrel populations are connected by substantial gene flow, belying the vast geographic distances among populations. When conducting Structure analysis at increasing K, there is indication of clinality between eastern (variegatus, rogachevae) and western (phaeopus, islandicus, alboaxillaris) populations (see non-blue parts of Structure plot in Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting possible isolation by distance (see Supplementary Fig. S1) as confirmed by a significant Mantel’s paired test (r = 0.414, p-value ≤ 0.001).

Estimated Effective Migration Surfaces (EEMS) analysis identified a barrier of low effective migration overlapping with and slightly east of the continental divide between Europe and Asia, indicating an area where the decay of genetic similarity with increasing geographic distance is significantly higher than expected under exact isolation-by-distance (Fig. 1b). The barrier divides eastern and western Palaearctic populations, which was also reflected as the main genomic division in principal component analysis (PCA) along principal component 1 (PC1) (Fig. 1c). However, this divergence only accounts for 6.4% of total genomic variation in PCA, alluding to generally low genomic differentiation among all Palaearctic whimbrels.

The most recently described whimbrel subspecies rogachevae from eastern Evenkia, central Siberia, was embedded with the Far-Eastern variegatus and both populations are potentially connected through a corridor of high effective migration (Fig. 1b,c). However, we only sampled one individual of rogachevae and additional sampling is required to validate, and furthermore resolve, the location of the effective migration corridor. Our sole sample of the pale steppe whimbrel was embedded within the western clade (Fig. 1c).

Eurasian curlew phylogeography

In contrast to the whimbrels, three distinct Eurasian curlew populations emerged, each corresponding to established subspecies51 (Fig. 1d; K = 3, ideal number of clusters54). At other values of K, the three Eurasian curlew populations remained discrete (see Supplementary Fig. S2). The main division was between eastern orientalis versus the more westerly suschkini and arquata, accounting for 10.7% of variation along PC1 (Fig. 1e).

A Mantel’s paired test failed to reveal a significant correlation (r = 0.173, p-value = 0.137) between genetic and geographic distance in Eurasian curlews. Further investigation into isolation by distance using EEMS analysis, accordingly, found no evidence for significant corridors or barriers within the Eurasian curlew’s range (see Supplementary Fig. S3). The absence of isolation by distance is typical for analyses that include deeply differentiated populations.

As in whimbrels, the affinity of the steppe curlew from the South Urals was closer to European populations (Fig. 1e).

Discussion

Our genome-wide data corroborate previous mtDNA-based studies4,6,26,55 in that Nearctic whimbrel populations are deeply differentiated from Palaearctic populations. Populations on the two continents also have a fixed difference in rump colouration52,56. This lack of substantial gene flow is despite opportunities when land bridges have connected Asia and North America57,58. We found no evidence for genomic admixture between Nearctic and Palaearctic whimbrels via variegatus, the Far-Eastern Palaearctic subspecies (Fig. 1a) conjectured to be an intermediate form between continents59. Genome-wide, mitochondrial and plumage evidence points to a deep rift between Nearctic and Palaearctic populations, advocating the elevation of North American breeding populations to species level as the “Hudsonian whimbrel” N. hudsonicus6,52.

Within Palaearctic whimbrels, a general lack of differentiation (Fig. 1b; see Supplementary Fig. S1) suggests extensive continent-wide gene flow as in other shorebirds28,48,49,60–62 and terrestrial vertebrates9,25,31,42,44,63. Palaeoclimatic habitat reconstructions of the LGM attest to a broad and nearly unbroken belt of suitable habitat stretching along the entire southern margin of the North European Ice Sheet64,65, which would have facilitated genetic exchange. Species breeding at high latitudes face displacement by advancing ice sheets during climatic oscillations66,67 and the relatively dynamic environment impedes isolation and differentiation of populations68. Conversely, the largely unglaciated expanses of the Far-Eastern Palaearctic have been a refuge from which species later re-expanded9,36,69–71 resulting in the divergence of East Asian populations37,66.

In contrast, the Eurasian curlew emerged as three distinct populations (Fig. 1d; see Supplementary Fig. S2) corresponding to three recognized subspecies. Such deeper population division is consistent with a large body of work on temperate biota showing genomic signatures of population re-expansions from separate glacial refugia32,34,40,72. Identifying the locations of these refugia would require more extensive sampling from across the curlew’s range. In addition, the migration pattern of Eurasian curlews also favours a reduction of population mixing and facilitates their accumulation of genetic differences. Eurasian curlews are shorter-distance migrants and are known to exhibit high fidelity to breeding sites73. On the other hand, whimbrels move over larger distances during migration (e.g., from East Siberia to Australia) and may disperse more widely among different breeding populations74. Previous shorebird studies have found mating system and migratory strategy to have an effect on population differentiation46–48. These are, however, not pertinent to differences in genetic structure between whimbrels and Eurasian curlews as both species are monogamous and overlap in non-breeding habitats73,74.

In both species, we found no evidence for a deep genomic separation of the palest taxa breeding in the South Urals, steppe whimbrel alboaxillaris and steppe curlew suschkini, from their respective conspecifics. However, only a single steppe whimbrel sample with moderate sequence coverage was available and deeper sampling will be needed for more authoritative statements on its genomic distinctness. The steppes south of the Urals are arid and experience warm summers75. The pale plumages of these subspecies are consistent with Gloger’s Rule76, which predicts that more arid environments harbour less heavily pigmented populations. The discordance between morphological and genetic differentiation may indicate a rapid evolution of ecomorphological adaptations controlled by few genes77 or phenotypic plasticity in response to environmental conditions78–83. The steppe whimbrel is now known to be an exceedingly rare taxon50,53,84. Even if future research upholds a lack of deep genomic differentiation in steppe whimbrels, their distinct plumage still warrants conservation efforts to preserve unique ecomorphological adaptations50,85.

Investigations into patterns of gene flow using EEMS analysis identified a barrier between the subspecies rogachevae from central Siberia and phaeopus breeding in sub-Arctic Europe (Fig. 1b). These results refute previous plumage-based predictions that variegatus is the most deeply differentiated Palaearctic whimbrel taxon on account of its dense rump barring6,59, but point to the importance of differences in axillary coloration uniting rogachevae and variegatus into an eastern cluster distinct from western phaeopus86.

The location of the EEMS barrier approximately overlaps with the Urals, a mountain range separating Europe from Asia, whose topographic relief may have rendered its slopes unsuitable for Numenius. The Urals may act as a suture zone in which phylogeographic breaks cluster20,39,87,88. Alternatively, the Yenisey area of Siberia has been proposed as an important zoogeographical boundary89, although – in the context of whimbrels – it lies to the east of the population divide identified by EEMS. It involves a vast transitional area with natural zonation amongst different habitats and was initially identified as the area where populations with typical phaeopus plumage transition into a rogachevae plumage type86.

As opposed to whimbrels, Eurasian curlews are temperate grassland and marsh breeders. The primary division in our Eurasian curlew dataset is likely deeper than that in whimbrels, and located further east, running between the subspecies suschkini and orientalis (Fig. 1d,e; see Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). This phylogeographic break falls within the Altai and Sayan Mountains separating open steppe habitats of Central Asia from the grasslands and river marshes of southern-central Siberia, northern Mongolia, Buryatia and the Amur region. Therefore, this barrier again coincides with areas of significant topographic relief that are unsuitable for curlew breeding, even during periods of global cooling. Ice-dammed lakes flooded parts of Russia during the LGM and may have posed a barrier to dispersal, especially those formed by the Ob River90. In summary, our analyses attest to the differential impact that Quaternary climate oscillations have had on biota with different habitat preferences.

Methods

Sampling regime

Our sampling regime aimed at a complete representation of all named taxa of the whimbrel and Eurasian curlew. A total of 53 tissue (muscle or liver) and blood samples were loaned (whimbrel: 38, Eurasian curlew: 15; see Supplementary Table S1). We assigned specimens lacking in subspecies identification based on sampling locality and known breeding distributions86,91,92. Distribution of the eastern N. a. orientalis may extend further west to intergrade with the western arquata51 (Fig. 1a) but ranges are not well resolved due to a lack of studies. Whimbrels from wintering localities in the Nearctic were not assigned while those in the Palaearctic were assigned to N. phaeopus variegatus based on their Australian provenance; there were no Eurasian curlew individuals from wintering localities. A common redshank Tringa totanus sample was included as an outgroup for phylogenetic rooting.

Library preparation, sequencing and raw data processing

DNA extractions were performed with the DNEasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) with an additional incubation step with heat-treated RNase. We prepared a reduced representation library using a modified ddRADSeq protocol93,94. Electrophoretic size selection for DNA fragments of 350 bp (±31 bp) was performed with Pippin Prep (Sage Science, Beverly, US). Pools were combined at equimolar volumes. The final library was spiked with 30% phiX and 150 bp paired-end reads were sequenced on a HiSeq. 4000 Illumina platform (Genome Institute of Singapore).

We checked the accuracy of sequencing of each base via phred scores with FastQC 0.11.5 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). As all bases had a mean phred score >30 (≥99.9% base call accuracy), no truncation was necessary. Raw sequences were demultiplexed and cleaned using process_radtags in Stacks 1.4495. We mostly discarded reads with uncalled bases (–c) but rescued reads if their barcodes contained two or fewer mismatches from the barcodes provided (–r). Only samples with more than 400,000 reads were retained for downstream analysis. We then aligned sequences to the Ruff Calidris pugnax genome96,97 using BWA-MEM 0.7.198,99 to identify homologous regions. Alignment quality was checked with samtools flagstat and sorted according to coordinate order with samtools sort in samtools 1.3.1100.

SNP calling

We created four SNP datasets for population genomic analysis: (1) all whimbrels, (2) all Palaearctic whimbrels, (3) Palaearctic whimbrels in breeding areas only, and (4) all Eurasian curlews. Loci were identified from sequences aligned to the reference genome using ref_map.pl in Stacks, followed by filtering using populations. We retained loci present in 90% of individuals (–r) and with a stack depth (minimum number of reads, –m) of 10 and 5 for Eurasian curlews and whimbrels, respectively (see Supplementary Table S2). To avoid obtaining linked SNPs, only the first SNP in each fragment was called and then filtered to remove linkage disequilibrium (r2 threshold of 0.9) using PLINK 1.9101. Using PLINK, we also quantified missing data per individual. Relatedness analysis was conducted to estimate identity by descent using maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation in ‘SNPRelate’ as implemented in R 3.5.1102,103 (see Supplementary Table S3). Individuals with >30% missing data were removed and SNPs were re-called from ref_map.pl. We checked SNP loci for neutrality in BayeScan 2.1104 using default settings. At a 5% false discovery rate, all SNPs showed no apparent signatures of selection and were retained.

We aimed to resolve the genomic affinity of the palest populations breeding in the South Urals. However, one of the taxa in question, the steppe whimbrel, was only represented by one individual with moderate sequence coverage. Hence, we partitioned this individual from other whimbrels (–p 2) during SNP calling in populations. This practice mitigated low coverage and missing data in this sample and ensured that all loci identified would be informative for this taxon of interest. No population partitioning was implemented for Eurasian curlews during SNP calling.

Population genomic structure analysis

To investigate population structure, we conducted PCA on three datasets: all whimbrels, only Palaearctic whimbrels, and Eurasian curlews, using ‘SNPRelate’. Population structure within Palaearctic populations of both species was further investigated in Structure 2.3105. An admixture model was applied and five iterations of each K from K = 1 to K = 10 at most were run with 50,000 burn-in cycles and 250,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations. Consensus structure results for each K value were obtained using CLUMPP 1.1.2106 and an optimal number of clusters was inferred where required54.

For analyses involving geographic information, only individuals from breeding localities in the Palaearctic were included. We tested for isolation by distance using a Mantel’s test with 999 replicates in ‘poppr’. We also implemented EEMS107 by performing three independent chains of 8 million MCMC iterations with a 1 million iteration burn-in using 200, 400 and 600 demes. Results were checked for consistency across the different regimes implemented and for convergence of MCMC runs. Finally, results across runs were combined and visualized using ‘rEEMSplots’107.

Phylogenomic analysis

We employed PyRAD 3.0.64108 to identify sequence data for phylogenomic analysis of all whimbrels109. The ddRADseq loci were assembled de novo using only the first read in each pair of paired-end sequences (ddrad) and an overall clustering threshold of 0.88 was applied. Loci had to be present in 90% of individuals (MinCov 26) with a minimum coverage of five per cluster (MinDepth 5) and a maximum of four undetermined (“N”) sites. A maximum of three shared polymorphic sites per locus was allowed (maxSH 3) to avoid inclusion of paralogs with fixed differences.

A ML tree was constructed for whimbrels in RAxML version 8.2.9110 using concatenated sequence reads identified by PyRAD. We applied two general time reversible models, with an optimisation of the substitution rate under a gamma distribution and a site-specific optimization of the substitution rate. A total of 1000 alternative trees were constructed in a rapid bootstrap analysis. The model with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion was selected and the best-scoring ML tree was visualised using Mesquite 3.2111.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the generous contribution of samples and assistance in sample transfer by Paul Sweet and Thomas Trombone at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH; New York, USA), Sharon Birks at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture (BMUW; Washington, USA), Robert Palmer and Leo Joseph at the Australian National Wildlife Collection (ANWC; Canberra, Australia), José Alves at the University of Iceland (UOI; Selfoss, Iceland), and Foo Maosheng at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum (LKCNHM; Singapore) (see Supplementary Table S1). We extend our appreciation to K. Sadanandan for providing lab work training, Dmitry Shitikov and Vladimir Sotnikov for providing photos of Russian museum specimens of which tissue samples were used for analysis, and the National Parks Board (Singapore) for their support in this project. F.E.R. acknowledges funding by a Ministry of Education (Singapore) Tier 1 research grant (WBS R-154-000-658-112). P.S.T. was supported by research project funding by the Zoological Museum of Moscow State University (ZMMU) (AAAA-A16-116021660077-3).

Author contributions

G.A.A., J.J.F.J.J. and F.E.R. conceived the project; G.A.A., J.J.F.J.J., H.Z.T. and P.S.T. acquired samples from museums; F.E.R. and H.Z.T. developed the approach; H.Z.T. performed the labwork and analysis with assistance from Q.T., F.E.R. and E.Y.X.N.; H.Z.T. and F.E.R. led the writing and all authors contributed to and reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data generated in this study will be available in the Sequence Read Archive repository (BioProject Number: PRJNA562783).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54715-9.

References

- 1.Avise JC, Walker D. Pleistocene phylogeographic effects on avian populations and the speciation process. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 1998;265:457–463. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt GM. The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature. 2000;405:907–913. doi: 10.1038/35016000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drovetski SV, et al. Complex biogeographic history of a Holarctic passerine. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004;271:545–551. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnsen A, et al. DNA barcoding of Scandinavian birds reveals divergent lineages in trans-Atlantic species. J. Ornithol. 2010;151:565–578. doi: 10.1007/s10336-009-0490-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Küpper C, et al. Kentish versus snowy plover: phenotypic and genetic analyses of Charadrius alexandrinus reveal divergence of Eurasian and American subspecies. Auk. 2009;126:839–852. doi: 10.1525/auk.2009.08174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zink RM, Rohwer S, Andreev AV, Dittmann DL. Trans-Beringia comparisons of mitochondrial DNA differentiation in birds. Condor. 1995;97:639–649. doi: 10.2307/1369173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zink RM, Rohwer S, Drovetski S, Blackwell-Rago RC, Farrell SL. Holarctic phylogeography and species limits of three-toed woodpeckers. Condor. 2002;104:167–170. doi: 10.1093/condor/104.1.167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badgley C, Fox DL. Ecological biogeography of North American mammals: species density and ecological structure in relation to environmental gradients. J. Biogeogr. 2000;27:1437–1467. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00498.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvist L, Martens J, Ahola A, Orell M. Phylogeography of a Palaearctic sedentary passerine, the willow tit (Parus montanus) J. Evol. Biol. 2001;14:930–941. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt T. Molecular biogeography of Europe: Pleistocene cycles and postglacial trends. Front. Zool. 2007;4:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sillero N, et al. Updated distribution and biogeography of amphibians and reptiles of Europe. Amphib. Reptil. 2014;35:1–31. doi: 10.1163/15685381-00002935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguillon SM, Campagna L, Harrison RG, Lovette IJ. A flicker of hope: genomic data distinguish Northern Flicker taxa despite low levels of divergence. Auk. 2018;135:748–766. doi: 10.1642/AUK-18-7.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson BW, Daugherty RJ. Characteristics and reproductive biology of Grosbeaks (Pheucticus) in the hybrid zone in South Dakota. Wilson Bull. 1974;86:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mettler RD, Spellman GM. A hybrid zone revisited: molecular and morphological analysis of the maintenance, movement, and evolution of a Great Plains avian (Cardinalidae: Pheucticus) hybrid zone. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:3256–3267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rising J. D. Current Ornithology. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1983. The Great Plains Hybrid Zones; pp. 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibley CG, Short LLJ. Hybridization in the buntings (Passerina) of the Great Plains. Auk. 1959;76:443–463. doi: 10.2307/4082312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sibley CG, Short LLJ. Hybridization in the orioles of the Great Plains. Condor. 1964;66:130–150. doi: 10.2307/1365391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sibley CG, West DA. Hybridization in the rufous-sided towhees of the Great Plains. Auk. 1959;76:326–338. doi: 10.2307/4081810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swenson NG. Gis-based niche models reveal unifying climatic mechanisms that maintain the location of avian hybrid zones in a North American suture zone. J. Evol. Biol. 2006;19:717–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swenson NG, Howard DJ. Clustering of contact zones, hybrid zones, and phylogeographic breaks in North America. Am. Nat. 2005;166:581–591. doi: 10.1086/491688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sclater PL. On the general geographical distribution of the members of the class Aves. (Continued.) J. Proc. Linn. Soc. London. Zool. 1858;2:137–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1858.tb02549a.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace, A. R. The geographical distribution of animals: with a study of the relations of living and extinct faunas as elucidating the past changes of the earth’s surface, 10.5962/bhl.title.46581 (Harper and Brothers, 1876).

- 23.Cramp, S. & Perrins, C. M. Handbook of the birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa: the birds of the Western Palearctic - volume III: waders to gulls. (Oxford University Press, 1983).

- 24.Holt BG, et al. An Update of Wallace’s zoogeographic regions of the world. Science. 2013;339:74–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1228282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haring E, Gamauf A, Kryukov A. Phylogeographic patterns in widespread corvid birds. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007;45:840–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr KCR, et al. Filling the gap - COI barcode resolution in eastern Palearctic birds. Front. Zool. 2009;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-6-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruskop SV, Borisenko AV, Ivanova NV, Lim BK, Eger JL. Genetic diversity of northeastern Palaearctic bats as revealed by DNA barcodes. Acta Chiropterologica. 2012;14:1–14. doi: 10.3161/150811012X654222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zink RM, Pavlova A, Drovetski S, Rohwer S. Mitochondrial phylogeographies of five widespread Eurasian bird species. J. Ornithol. 2008;149:399–413. doi: 10.1007/s10336-008-0276-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunhoff C, Galbreath KE, Fedorov VB, Cook JA, Jaarola M. Holarctic phylogeography of the root vole (Microtus oeconomus): implications for late Quaternary biogeography of high latitudes. Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:957–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fedorov VB, Goropashnaya AV, Boeskorov GG, Cook JA. Comparative phylogeography and demographic history of the wood lemming (Myopus schisticolor): implications for late Quaternary history of the taiga species in Eurasia. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:598–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zink RM, Drovetski SV, Rohwer S. Phylogeographic patterns in the great spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major across Eurasia. J. Avian Biol. 2002;33:175–178. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-048X.2002.330208.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hung CM, Drovetski SV, Zink RM. Recent allopatric divergence and niche evolution in a widespread Palearctic bird, the common rosefinch (Carpodacus erythrinus) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;66:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kryukov A, et al. Synchronic east-west divergence in azure-winged magpies (Cyanopica cyanus) and magpies (Pica pica) J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2004;42:342–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2004.00287.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saitoh Takema, Alström Per, Nishiumi Isao, Shigeta Yoshimitsu, Williams Dawn, Olsson Urban, Ueda Keisuke. Old divergences in a boreal bird supports long-term survival through the Ice Ages. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2010;10(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Someya S, et al. DNA barcoding reveals 24 distinct lineages as cryptic bird species candidates in and around the Japanese Archipelago. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2014;15:177–186. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krehenwinkel H, et al. A phylogeographical survey of a highly dispersive spider reveals eastern Asia as a major glacial refugium for Palaearctic fauna. J. Biogeogr. 2016;43:1583–1594. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer F, et al. Comparative multilocus phylogeography of two Palaearctic spruce bark beetles: influence of contrasting ecological strategies on genetic variation. Mol. Ecol. 2015;24:1292–1310. doi: 10.1111/mec.13104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harris RB, Alström P, Ödeen A, Leaché AD. Discordance between genomic divergence and phenotypic variation in a rapidly evolving avian genus (Motacilla) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018;120:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raković M, et al. Geographic patterns of mtDNA and Z-linked sequence variation in the common chiffchaff and the ‘chiffchaff complex’. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossiter SJ, Benda P, Dietz C, Zhang S, Jones G. Rangewide phylogeography in the greater horseshoe bat inferred from microsatellites: implications for population history, taxonomy and conservation. Mol. Ecol. 2007;16:4699–4714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zink RM, Drovetski SV, Rohwer S. Selective neutrality of mitochondrial ND2 sequences, phylogeography and species limits in Sitta europaea. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006;40:679–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalén L, et al. Population history and genetic structure of a circumpolar species: the Arctic fox. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2005;84:79–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00415.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goropashnaya AV, Fedorov VB, Seifert B, Pamilo P. Limited phylogeographical structure across Eurasia in two red wood ant species Formica pratensis and F. lugubris (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:1849–1858. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paulauskas A, Tubelyte V, Baublys V, Sruoga A. Genetic differentiation of dabbling ducks (Anseriformes: Anas) populations from Palaearctic in time and space. Proc. Latv. Acad. Sci. 2009;63:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wenink PW, Baker AJ, Rosner H-U, Tilanus MGJ. Global mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of Holarctic breeding dunlins (Calidris alpina) Evolution. 1996;50:318–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraaijeveld K. Non-breeding habitat preference affects ecological speciation in migratory waders. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:347–354. doi: 10.1007/s00114-007-0326-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D’Urban Jackson J, et al. Polygamy slows down population divergence in shorebirds. Evolution. 2017;71:1313–1326. doi: 10.1111/evo.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Küpper C, et al. High gene flow on a continental scale in the polyandrous Kentish plover Charadrius alexandrinus. Mol. Ecol. 2012;21:5864–5879. doi: 10.1111/mec.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rönkä N, et al. Phylogeography of the Temminck’s stint (Calidris temminckii): historical vicariance but little present genetic structure in a regionally endangered Palearctic wader. Divers. Distrib. 2012;18:704–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4642.2011.00865.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allport G. Steppe Whimbrels Numenius phaeopus alboaxillaris at Maputo, Mozambique, in February–March 2016, with a review of the status of the taxon. Bull. African Bird Club. 2017;24:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Engelmoer Meinte, Roselaar Cees S. Geographical Variation in Waders. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Engelmoer Meinte, Roselaar Cees S. Geographical Variation in Waders. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morozov VV. Current status of the southern subspecies of the whimbrel Numenius phaeopus alboaxillaris (Lowe 1921) in Russia and Kazakstan. Wader Study Gr. Bull. 2000;92:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sangster G, et al. Taxonomic recommendations for British birds: second report. Ibis (Lond. 1859). 2011;153:883–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.2011.01155.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paulson, D. Shorebirds of the Pacific Northwest. (University of Washington Press, 1993).

- 57.Elias SA, Crocker B. The Bering land bridge: a moisture barrier to the dispersal of steppe-tundra biota? Quat. Sci. Rev. 2008;27:2473–2483. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galbreath KE, Cook JA. Genetic consequences of Pleistocene glaciations for the tundra vole (Microtus oeconomus) in Beringia. Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:135–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2004.02026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Livezey BC. Phylogenetics of modern shorebirds (Charadriiformes) based on phenotypic evidence: analysis and discussion. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2010;160:567–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00635.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conklin JR, et al. Low genetic differentiation between Greenlandic and Siberian sanderling populations implies a different phylogeographic history than found in red knots. J. Ornithol. 2016;157:325–332. doi: 10.1007/s10336-015-1284-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rheindt Frank E., Székely Tamás, Edwards Scott V., Lee Patricia L. M., Burke Terry, Kennerley Peter R., Bakewell David N., Alrashidi Monif, Kosztolányi András, Weston Michael A., Liu Wei-Ting, Lei Wei-Pan, Shigeta Yoshimitsu, Javed Sálim, Zefania Sama, Küpper Clemens. Conflict between Genetic and Phenotypic Differentiation: The Evolutionary History of a ‘Lost and Rediscovered’ Shorebird. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e26995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verkuil YI, et al. The interplay between habitat availability and population differentiation: a case study on genetic and morphological structure in an inland wader (Charadriiformes) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2012;106:641–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2012.01878.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yannic G, et al. Genetic diversity in caribou linked to past and future climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013;4:132–137. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Binney H, et al. Vegetation of Eurasia from the last glacial maximum to present: key biogeographic patterns. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017;157:80–97. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tarasov PE, et al. Last glacial maximum biomes reconstructed from pollen and plant macrofossil data from northern Eurasia. J. Biogeogr. 2000;27:609–620. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00429.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hewitt GM. Genetic consequences of climatic oscillations in the Quaternary. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:183–195. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thies L, et al. Population and subspecies differentiation in a high latitude breeding wader, the common ringed plover Charadrius hiaticula. Ardea. 2018;106:163. doi: 10.5253/arde.v106i2.a8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dynesius M, Jansson R. Evolutionary consequences of changes in species’ geographical distributions driven by Milankovitch climate oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:9115–9120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P. L. & Hughes, P. D. Quaternary glaciations-extent and chronology: a closer look. (Elsevier, 2011).

- 70.Höglund J, Johansson T, Beintema A, Schekkerman H. Phylogeography of the black-tailed godwit Limosa limosa: substructuring revealed by mtDNA control region sequences. J. Ornithol. 2009;150:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s10336-008-0316-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trimbos Krijn B., Doorenweerd Camiel, Kraaijeveld Ken, Musters C. J. M., Groen Niko M., de Knijff Peter, Piersma Theunis, de Snoo Geert R. Patterns in Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Reveal Historical and Recent Isolation in the Black-Tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa) PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e83949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weksler M, Lanier HC, Olson LE. Eastern Beringian biogeography: historical and spatial genetic structure of singing voles in Alaska. J. Biogeogr. 2010;37:1414–1431. [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Gils, J., Wiersma, P., Kirwan, G. M. & Sharpe, C. J. Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata). in Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (eds del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E.) (Lynx Edicions, 2019).

- 74.van Gils, J., Wiersma, P. & Kirwan, G. M. Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus). In Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive (eds del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E.) (Lynx Edicions, 2019).

- 75.Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C, Rudolf B, Rubel F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Zeitschrift. 2006;15:259–263. doi: 10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gloger, C. L. Das Abändern der Vögel durch Einfluss des Klimas. (August Schulz, 1833).

- 77.Humphries EM, Winker K. Discord reigns among nuclear, mitochondrial and phenotypic estimates of divergence in nine lineages of trans-Beringian birds. Mol. Ecol. 2011;20:573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mason NA, Taylor SA. Differentially expressed genes match bill morphology and plumage despite largely undifferentiated genomes in a Holarctic songbird. Mol. Ecol. 2015;24:3009–3025. doi: 10.1111/mec.13140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burtt EH, Ichida JM. Gloger’s rule, feather-degrading bacteria, and color variation among song sparrows. Condor. 2004;106:681–690. doi: 10.1093/condor/106.3.681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hogstad O, Thingstad PG, Daverdin M. Gloger’s ecogeographical rule and colour variation among willow tits Parus montanus. Ornis Nor. 2009;32:49–55. doi: 10.15845/on.v32i0.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Remsen JV. High incidence of ‘leapfrog’ pattern of geographic variation in Andean birds: implications for the speciation process. Science. 1984;224:171–173. doi: 10.1126/science.224.4645.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snow DW. The habitats of Eurasian tits (Parus spp.) Ibis (Lond. 1859). 1954;96:565–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-919X.1954.tb05478.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental plasticity and the origin of species differences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(Suppl):6543–6549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501844102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Belik, V. Where on earth does the Slender-billed Curlew breed? Wader Study Gr. Bull 37–38 (1994).

- 85.PEARCE-HIGGINS JAMES W., BROWN DANIEL J., DOUGLAS DAVID J. T., ALVES JOSÉ A., BELLIO MARIAGRAZIA, BOCHER PIERRICK, BUCHANAN GRAEME M., CLAY ROB P., CONKLIN JESSE, CROCKFORD NICOLA, DANN PETER, ELTS JAANUS, FRIIS CHRISTIAN, FULLER RICHARD A., GILL JENNIFER A., GOSBELL KEN, JOHNSON JAMES A., MARQUEZ-FERRANDO ROCIO, MASERO JOSE A., MELVILLE DAVID S., MILLINGTON SPIKE, MINTON CLIVE, MUNDKUR TAEJ, NOL ERICA, PEHLAK HANNES, PIERSMA THEUNIS, ROBIN FRÉDÉRIC, ROGERS DANNY I., RUTHRAUFF DANIEL R., SENNER NATHAN R., SHAH JUNID N., SHELDON ROB D., SOLOVIEV SERGEJ A., TOMKOVICH PAVEL S., VERKUIL YVONNE I. A global threats overview for Numeniini populations: synthesising expert knowledge for a group of declining migratory birds. Bird Conservation International. 2017;27(1):6–34. doi: 10.1017/S0959270916000678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tomkovich PS. A new subspecies of the Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) from Central Siberia. Zool. žurnal. 2008;87:1092–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hewitt GM. Some genetic consequences of ice ages, and their role in divergence and speciation. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1996;58:247–276. doi: 10.1006/bijl.1996.0035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marova IM, Fedorov VV, Shipilina DA, Alekseev VN. Genetic and vocal differentiation in hybrid zones of passerine birds: Siberian and European chiffchaffs (Phylloscopus [collybita] tristis and Ph. [c.] abietinus) in the southern Urals. Dokl. Biol. Sci. 2009;427:384–386. doi: 10.1134/S0012496609040231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rogacheva, H. The birds of Central Siberia. (Husum Druck-und Verlagsgesellschaft, 1992).

- 90.Mangerud J, Astakhov V, Jakobsson M, Svendsen JI. Huge Ice-age lakes in Russia. J. Quat. Sci. 2001;16:773–777. doi: 10.1002/jqs.661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.BirdLife International and Handbook of the Birds of the World. Bird species distribution maps of the world. Version 2017.2, http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/requestdis (2017).

- 92.Lappo, E. G., Tomkovich, P. S. & Syroeckovskiy, E. E. Atlas of breeding waders in the Russian Arctic. (Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Sciences, 2012).

- 93.Chattopadhyay B, Garg KM, Kumar AKV, Doss DPS, Rheindt FE. Genome-wide data reveal cryptic diversity and genetic introgression in an Oriental cynopterine fruit bat radiation. BMC Evol. Biol. 2016;16:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0599-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peterson, B. K., Weber, J. N., Kay, E. H., Fisher, H. S. & Hoekstra, H. E. Double digest RADseq: an inexpensive method for de novo SNP discovery and genotyping in model and non-model species. PLoS One7 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Catchen J, Hohenlohe PA, Bassham S, Amores A, Cresko WA. Stacks: an analysis tool set for population genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:3124–3140. doi: 10.1111/mec.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gibson R, Baker A. Multiple gene sequences resolve phylogenetic relationships in the shorebird suborder Scolopaci (Aves: Charadriiformes) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2012;64:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Küpper C, et al. A supergene determines highly divergent male reproductive morphs in the ruff. Nat. Genet. 2015;48:79–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Prepr. (2013).

- 99.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. 81, 559–575 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.r-project.org/ (2018).

- 103.Zheng X, et al. A high-performance computing toolset for relatedness and principal component analysis of SNP data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3326–3328. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Foll M, Gaggiotti O. A genome-scan method to identify selected loci appropriate for both dominant and codominant markers: a Bayesian perspective. Genetics. 2008;180:977–993. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.092221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 106.Jakobsson M, Rosenberg NA. CLUMPP: A cluster matching and permutation program for dealing with label switching and multimodality in analysis of population structure. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1801–1806. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Petkova D, Novembre J, Stephens M. Visualizing spatial population structure with estimated effective migration surfaces. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:94–100. doi: 10.1038/ng.3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eaton DAR. PyRAD: Assembly of de novo RADseq loci for phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1844–1849. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Garg KM, Chattopadhyay B, Wilton PR, Malia Prawiradilaga D, Rheindt FE. Pleistocene land bridges act as semipermeable agents of avian gene flow in Wallacea. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018;125:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maddison, W. P. & Maddison, D. R. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 3.2, http://www.mesquiteproject.org (2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study will be available in the Sequence Read Archive repository (BioProject Number: PRJNA562783).