Abstract

Chronic wound treatment is becoming increasingly difficult and costly, further exacerbated when wounds become infected. Bacterial biofilms cause most chronic wound infections and are notoriously resistant to antibiotic treatments. The need for new approaches to combat polymicrobial biofilms in chronic wounds combined with the growing antimicrobial resistance crisis means that honey is being revisited as a treatment option due to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and low propensity for bacterial resistance. We assessed four well-characterised New Zealand honeys, quantified for their key antibacterial components, methylglyoxal, hydrogen peroxide and sugar, for their capacity to prevent and eradicate biofilms produced by the common wound pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We demonstrate that: (1) honey used at substantially lower concentrations compared to those found in honey-based wound dressings inhibited P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and significantly reduced established biofilms; (2) the anti-biofilm effect of honey was largely driven by its sugar component; (3) cells recovered from biofilms treated with sub-inhibitory honey concentrations had slightly increased tolerance to honey; and (4) honey used at clinically obtainable concentrations completely eradicated established P. aeruginosa biofilms. These results, together with their broad antimicrobial spectrum, demonstrate that manuka honey-based wound dressings are a promising treatment for infected chronic wounds, including those with P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Subject terms: Antimicrobial resistance, Antimicrobial resistance, Biofilms, Biofilms

Introduction

The management and treatment of chronic wounds is an increasingly difficult and costly problem, further exacerbated when the wounds become infected1. Bacterial biofilms, where cells are embedded within a matrix comprised of exopolysaccharides and other components including DNA, proteins, and membrane vesicles, are the major cause of chronic wound infections and are notoriously resistant to treatment with antibiotics2,3.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a particularly virulent wound pathogen and is commonly isolated from the polymicrobial biofilms found in chronic wounds4–7. Infections caused by P. aeruginosa are especially difficult to treat due to the inherent antibiotic resistance mechanisms possessed by the organism. This includes multi-drug efflux pumps that remove antibiotics from inside the cell before they can act on specific targets8–10. Additionally, the physical structure of the extracellular P. aeruginosa biofilm matrix inhibits penetration of the biofilm, and so P. aeruginosa associated chronic wound infections often do not respond to treatments with conventional antibiotics11,12. The need for new approaches to combat polymicrobial biofilms in chronic wounds (particularly those colonised by P. aeruginosa), combined with the current and growing crisis of antimicrobial resistance warrants investigation into the use of complex natural products with antimicrobial activity as potential treatment avenues.

Prior to the introduction of modern antibiotics, treating wounds with honey was a common and effective practice, almost certainly due to its potent antimicrobial properties13. Honey is usually made by bees, most commonly the European honey bee, Apis mellifera, from the nectar of flowering plants. The honey types derived from different plants vary substantially in their antimicrobial activity14–18, which stems from multiple factors including high sugar content, low pH and the production of hydrogen peroxide via the bee-derived enzyme, glucose oxidase19,20. Certain honeys derived from the Leptospermum species of plants native to Australia and New Zealand (e.g. manuka honey) have an additional antimicrobial component called methylglyoxal, or MGO, which forms from the nectar-derived precursor compound, dihydroxyacetone (DHA), during the ripening of honey21–23. The level of MGO in Leptospermum honey has been positively correlated to the ‘non-peroxide activity’, referring to the antibacterial activity remaining in honey following neutralisation of hydrogen peroxide via the addition of catalase, in previous studies21–23. These honeys are the most commonly used for medical-grade honey products as their MGO-derived non-peroxide activity is not affected by catalase present in the body and they are available in the form of various sterile products licensed for use in wound care24,25.

The antimicrobial action of New Zealand manuka-based honeys have been demonstrated in vitro against a wide range of problematic bacterial pathogens, including those that can colonise the skin and wounds such as Staphylococcus aureus and P. aeruginosa26. Of particular note is that manuka honey is equally effective at inhibiting multi-drug resistant clinical isolates as it is against sensitive strains, indicating a broad spectrum of activity unlike that of other known antibiotics27–29. In addition, bacteria are unable to develop resistance to honey, even under conditions that rapidly induce resistance to common antibiotics30,31.

As well as inhibiting planktonic cell growth, honey has previously been demonstrated to have anti-biofilm activity in vitro. Manuka honey prevents the formation of biofilms by many problematic wound pathogens, including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, Acinetobacter baumannii, Eschericia coli, Enterobacter cloacae and P. aeruginosa, and it eradicates established biofilms32–40. However, the levels of reported anti-biofilm activity are not consistent among all studies (ranging from 12–50%), which is likely to be due to differences in the levels of the major antibacterial components in the honey. Although MGO has been shown to have inhibitory action against established S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilms previously41, it is not solely responsible for the anti-biofilm activity of manuka-type honeys highlighting the importance of additional components in the honey that modulate activity38.

Here we have assessed the anti-biofilm activity of four New Zealand honeys, including three manuka-based samples, and their key antibacterial components (i.e. MGO, hydrogen peroxide and sugar) against two P. aeruginosa strains of different biofilm-forming ability. The honey samples were characterised in terms of their geographical and floral source and the levels of the two major antibacterial components, MGO and hydrogen peroxide. We demonstrate that the honeys are active in both the prevention and eradication of P. aeruginosa biofilms, and that MGO is not the major driver of anti-biofilm activity of the manuka-type honeys. While the sugar solution (control) was demonstrated to be similarly effective in biofilm prevention and eradication, this does not negate the use of honey over sugar solutions in clinical practice as sugar alone is not as effective at similar concentrations to honey against other common wound pathogens30,38,42–46. This study also emphasises the importance of using well-characterised honeys in order to understand the antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activity and to choose the most appropriate honey for treating infected wounds.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

The two laboratory reference strains of P. aeruginosa used in this study, PAO1 (ATCC 15692) and PA14 (UCBPP-PA14), were originally isolated from burn wounds47,48. Strains were grown in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB; Becton Dickinson Biosciences, USA) at 37 °C.

Honey samples and control solutions

The four honey samples used in this study were all of New Zealand (NZ) origin and included three manuka-type honeys: monofloral manuka honey, Medihoney (a manuka-based medical-grade honey), and a manuka-kanuka blend, as well as a clover honey. All honey samples were supplied by Comvita NZ Ltd (Te Puke, New Zealand). Floral source, harvesting and geographic information, as well as the levels of methylglyoxal (MGO) and the MGO pre-cursor compound, di-hydroxyacetone (DHA) were supplied by Comvita NZ Ltd and are shown in Table 1. All honey samples were stored in the dark at 4 °C and were freshly diluted in CAMHB immediately before use in assays. All honey concentrations are expressed as % weight per volume (w/v).

Table 1.

Harvesting, geographical and composition data for honey samples.

| Honey type | Harvest period | Area | Floral source | Major antimicrobial components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGOa | DHAb | H2O2c | ||||

| Manuka | Spring 2010 | Hokianga, Northland, NZ | Leptospermum scoparium var. incanum | 958 | 4277 | 0.34 |

| Medihoney | Spring 2010 | Northland, NZ | Leptospermum scoparium var. incanum + Kunzea ericoides | 776 | 883 | 0.31 |

| Manuka-kanuka | Summer 2010/11 | Hokianga, Northland, NZ | Leptospermum scoparium var. incanum + Kunzea ericoides | 161 | 652 | 0.68 |

| Clover | N/A | Balcutha, Otago, NZ | Trifolium spp. | <10 | <20 | 0.11 |

aMGO (methylglyoxal) levels expressed as mg per kg of honey.

bDHA (dihydroxyacetone) levels expressed as mg per kg of honey. DHA exhibits no antimicrobial activity itself, but converts to the antimicrobial compound, MGO. DHA levels provide an estimate of the potential antimicrobial activity of Leptospermum honey.

cH2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) rate of production expressed as mmol/h in 1 ml of 10% w/v honey; measured in ten minute intervals over the course of 40 min.

*N/A: not applicable.

The following control solutions were also included in this study: (i) a sugar solution composed of glucose, fructose and sucrose (45 g, 38 g and 1 g, respectively) prepared in water (16 ml) and designed to mimic the concentration and composition of the main sugars in honey; (ii) an MGO solution prepared in CAMHB at concentrations similar to those present in the manuka-type honeys (i.e. 100 mg/kg, 700 mg/kg, and 900 mg/kg) to assess the effects of MGO alone; and (iii) MGO diluted (to the same concentrations as (ii)) in sugar solution to assess the combined effects of MGO and the main sugars of honey. MGO was sourced as a ~40% (w/w) solution in water (Sigma-Aldrich Co., MO, USA). Control solutions were stored and freshly diluted as per the honey samples above.

Hydrogen peroxide assay

The levels of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; another major antimicrobial component in honey) produced by the honey samples was determined using an Amplex Red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase kit (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) as previously described49, and are included in Table 1.

Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to honeys

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the honeys and sugar solution for P. aeruginosa were determined using the CLSI broth microdilution method50, with some modifications described below.

Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa (2 ml, shaking at 250 rpm) were diluted to give a final cell density of 107 CFU/ml in fresh CAMHB containing the appropriate test solution (honey or sugar). Honey stock solutions (50% w/v) were freshly prepared, and further diluted 2-fold serially in CAMHB to the required test concentrations ranging from 1–32%.

Media (CAMHB) alone was included as a growth (untreated) control. The assay was set up in 96-well microtitre plates (BD Falcon, NJ, USA), covered with AeraSeal (Excel Scientific, CA, USA) and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Cell growth was measured by optical density at 595 nm (OD595) in a plate reader (VersaMax, Molecular Devices, California, USA) and the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which the OD was ≤5% relative to the untreated control, indicating at least 95% inhibition of cell growth.

Biofilm formation assays

The effect of the test solutions (honey and control solutions) on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation was determined using crystal violet static biofilm assays in microtitre plates as previously published51, with some modifications.

P. aeruginosa biofilms were prepared in CAMHB with several concentrations of honey, as described above. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, the microtitre plates were washed three times in an automated plate washer (Bio-Tek, ELX405, Winooski, VT, USA) with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove unattached cells. The plates were stained with 0.2% w/v crystal violet, incubated at room temperature for 1 h and excess crystal violet solution washed out using the same program above. The stain that was bound to the adherent biofilm biomass was resolubilised in acetic acid (33% w/v, 200 µl), transferred to a new microtitre plate and the OD595 measured. The minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) was determined as the lowest concentration at which the OD was ≤5% of that of the untreated control, indicating at least 95% inhibition of biofilm formation.

Biofilm elimination assays

P. aeruginosa biofilms were first allowed to form in the wells of mictrotitre plates for 24 h at 37 °C as described above, but in CAMHB only (i.e. no treatment). The plates were then washed three times with PBS, and various concentrations (0%, 1%, 2%, 4%, 16%, and 32%) of the four honeys and control solutions were added to the established biofilms. The wells containing 0% treatment concentration were made up to volume using CAMHB. The plates were further incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, and the biofilm biomass was quantified using crystal violet as above.

Bacterial cell viability in biofilms

The viability of cells within the P. aeruginosa biofilms following treatment with honey or control solutions (for 24 h, as above) was quantified by the BacTitre Glo Microbial Cell Viability Assay Kit (Promega, WI, USA), which measures ATP levels via a luminescence-based luciferase activity assay as an indicator of cell viability52,53. After treatment, bacterial biofilms were washed as described above, followed by incubation with the BacTitre Glo reagent in CAMHB for 10 min at 37 °C in the dark.

The assay was performed and validity checked against a standard curve as previously described for Staphylococcus aureus38, with the modification of using CAMHB for P. aeruginosa biofilms. Biofilms were produced and washed as above and cells within the biofilm dispersed using a small-probe sonicator (8 sec at 40% power; Sonics and materials VC-505) to enable quantification by direct enumeration. Bacterial colony forming units (CFUs) per well were calculated and plotted against the luminescent readings from the corresponding well to generate the standard curve (Supplementary Fig. S1). The lower detection limit of the BacTitre Glo assay was at the luminescence value of <1000, which is equivalent to 103 CFU/ml.

Visualising P. aeruginosa biofilms using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

P. aeruginosa biofilms treated with 1%, 2%, 16%, and 32% of each of the four honeys or the sugar solution control (all prepared in CAMHB) were visualised using live/dead staining with Syto9 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and propidium iodide (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) and imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy, as previously described38. As higher concentrations of honey are used in the commercially available honey-based wound dressings, higher concentrations (64% and 80%) of the monofloral manuka honey and Medihoney samples were also tested.

Susceptibility of P. aeruginosa cells recovered from treated biofilms to honeys

As it is known that bacteria are more likely to become resistant to antimicrobial compounds following exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations54,55, the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa following exposure to sub-inhibitory concentrations of honey was determined using the MIC and MBIC methods described above. P. aeruginosa cells recovered from biofilms treated with sub-inhibitory concentrations (8%) of the manuka-type honeys were tested to determine their ability to grow and form biofilms in the presence of higher (previously inhibitory) concentrations of these honeys (16% and 32%).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses to compare treatments (honeys and control solutions) were performed using GraphPad Prism (versions 5 and 6). Normal (Gaussian) distribution of data were checked using the D’Agostino-Pearson normality test (alpha = 0.05). Differences among honey samples and across control solutions were determined using One-Way ANOVA with Tukey Test, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Effect of honey on P. aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation and re-assessment of susceptibility following honey treatment

The effects of the four NZ honeys and control solutions on P. aeruginosa planktonic cell growth and biofilm formation were assessed. The two P. aeruginosa strains used in this study, PAO1 and PA14, had different biofilm forming abilities (Supplementary Fig. S2), and all honeys were effective at inhibiting the planktonic cell growth and biofilm formation of both strains. Planktonic growth of both P. aeruginosa strains was completely inhibited by 16% of the three manuka-type honeys and by 32% clover honey (Table 2). The sugar solution also inhibited PAO1 growth at 32%, but PA14 was not inhibited at any of the tested sugar concentrations (1–32%).

Table 2.

Concentrations of honey required to inhibit P. aeruginosa cell growth and biofilm formation before and after exposure to honey.

| Honey | Initial susceptibilitya | Susceptibility after exposure to honeyb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | PA14 | PAO1 | PA14 | |||||

| MIC | MBIC | MIC | MBIC | MIC | MBIC | MIC | MBIC | |

| Manuka | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Medihoney | 16 | 32 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Manuka-kanuka | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Clover | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sugar solution | 32 | 32 | >32 | 32 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

All concentrations are expressed as percentage weight per volume (% w/v).

aInitial susceptibility of PAO1 and PA14 to honeys.

bSusceptibility of PAO1 and PA14 cells recovered from biofilms that had been treated with a sub-inhibitory concentration (8%) of honey.

N/A: not applicable as these honeys were not tested in resistance assays.

Biofilm formation was inhibited by the four tested honeys, and the sugar solution for both PAO1 and PA14. Generally, the MBICs were the same as the MICs, however the MBIC for PAO1 was 2-fold higher (32%) with Medihoney and for PA14 this was 2-fold lower (8%) with manuka honey (Table 2). The MBIC for clover honey and the sugar solution was 32%, with the following exceptions: the MBIC for PA14 with clover honey was 16% i.e. 2-fold less than the MIC; and the MBIC of the sugar solution was 32% while the MIC was >32%.

Table 2 also shows susceptibility testing of P. aeruginosa cells derived from the honey-treated biofilms. Generally the MICs and MBICs increased at least 2-fold.

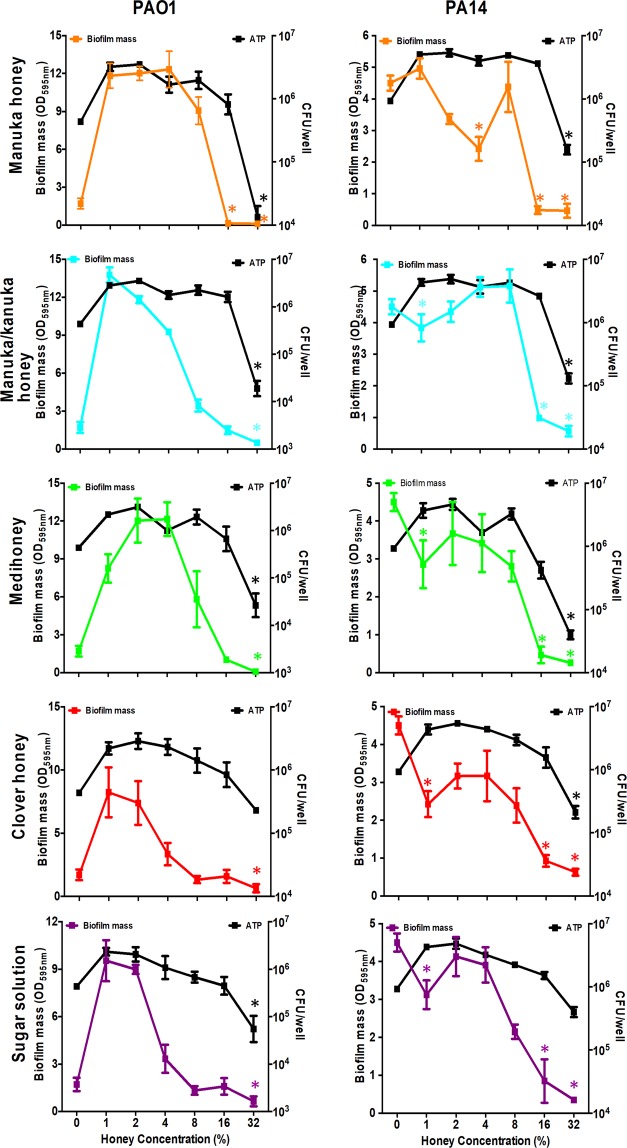

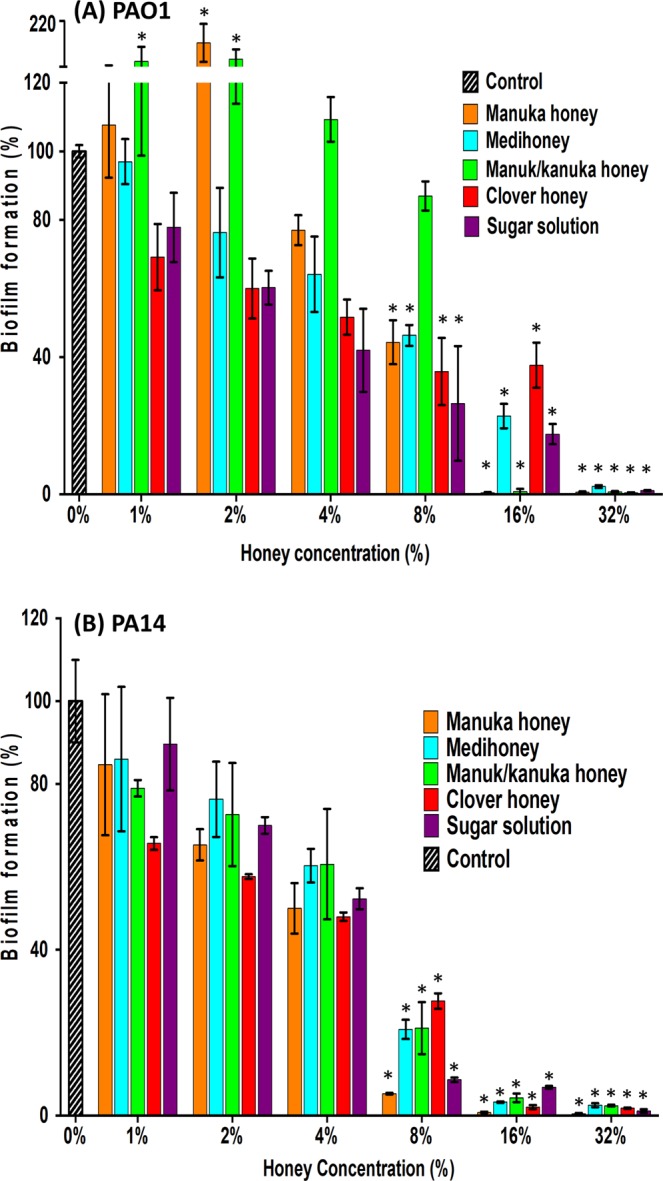

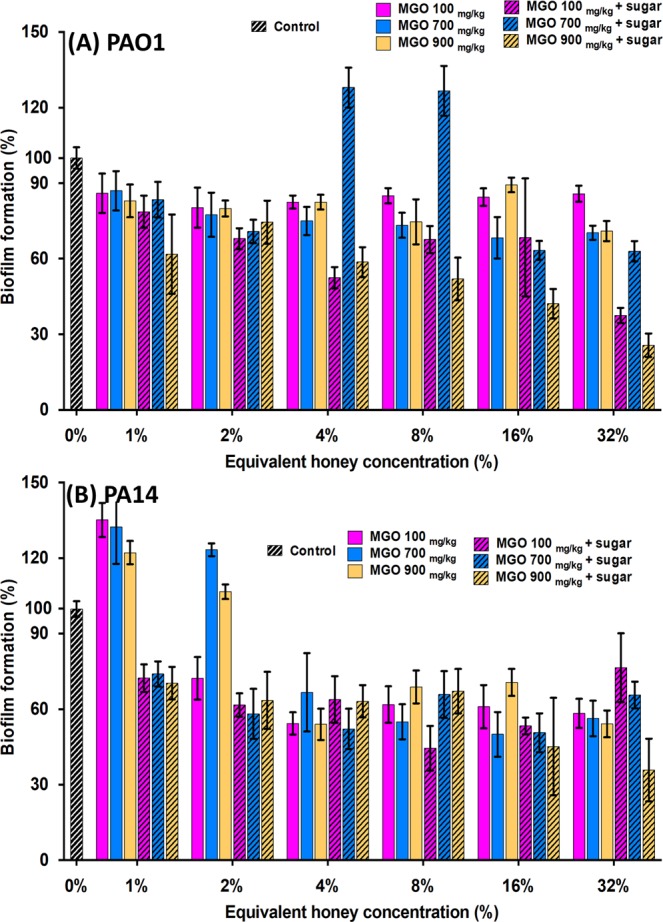

In some cases, low concentrations of manuka and manuka-kanuka honey enhanced biofilm formation (Fig. 1). Biofilm biomass of PAO1 was significantly enhanced (p < 0.05) by sub-inhibitory concentrations of manuka (2%) and manuka-kanuka (1% and 2%) honey. This effect, which has previously been seen with certain antibiotics, was not observed in strain PA14.

Figure 1.

Effect of honey and sugar solution on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation. P. aeruginosa PAO1 (A) and PA14 (B) biofilms were allowed to form in the presence of four NZ honeys (manuka, Medihoney, manuka-kanuka, or clover) or a sugar solution. Biofilm formation was assessed using a static biofilm formation assay with crystal violet staining to quantify biomass. Biofilm formation is expressed as % relative to that produced by the untreated control (Control), which is set at 100%. Error bars represent ± SD of three biological samples, all performed in triplicate. *Indicates statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) relative to the untreated control (Control; 0%).

Effect of honey on established P. aeruginosa biofilms

As bacterial biofilms are already established in chronic wounds, the ability of honey to eradicate pre-formed P. aeruginosa biofilms was investigated. In general, treatment with 16% or 32% honey resulted in a significant (p < 0.05) reduction in biofilm biomass (Fig. 2). The two strains of P. aeruginosa differed in their responses to the lower concentrations of honey and this may be attributed to their different biofilm forming abilities shown in Supplementary Fig. S2 and also indicated by the markedly different biomass values at the 0% honey concentration in Fig. 2. For PAO1, the biofilm biomass was significantly enhanced when sub-inhibitory concentrations (1–4%) of any of the honeys or the sugar solution was used (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the PA14 results showed that at very low levels (1%) of the manuka-kanuka honey, Medihoney, clover honey and the sugar control, biofilm biomass was generally inhibited, then augmented with higher levels of the treatments until it became inhibitory at the highest levels (Fig. 2). For PAO1 there was <40% reduction in biofilm mass following treatment with all honeys except manuka, while all four honeys and the sugar solution reduced the biofilms established by strain PA14 by ≥75% relative to the untreated control (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 2.

Effect of honey or sugar solution on established P. aeruginosa biofilms and on cell viability within the biofilms. Established P. aeruginosa PAO1 (left panels) and PA14 (right panels) biofilms were treated with four NZ honeys (manuka, Medihoney, manuka-kanuka, and clover), or a sugar solution. Biofilm biomass remaining post-treatment (coloured lines) was quantified using crystal violet staining and expressed as OD595 (left y-axis). The corresponding cell viability (black line) within remaining biofilms was assessed via ATP production using the BacTitre Glo Viability Kit and CFU/well values were determined from a previously established standard curve (right y-axis). Data represents mean values from three biological replicates, all performed in triplicate ± SD. Coloured (*) indicate statistically significant decrease (p < 0.05) in biofilm biomass and black (*) indicates statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) in ATP production, both relative to the control (at 0% honey concentration).

An ATP-based viability assay was used to approximate the number of viable cells remaining within the biofilm after treatment with the honeys or sugar solution. In general, cell viability decreased significantly for all treatments at 32% (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1). While 16% reduced the established biofilm biomass of both PAO1 and PA14, cell viability significantly increased (p < 0.05) or there was no change compared to the untreated control. Additionally, sub-inhibitory concentrations (1% and 2%) of the different honey or sugar solution treatments enhanced PA14 cell viability within the established biofilms (p < 0.05) but not the biofilm biomass (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2).

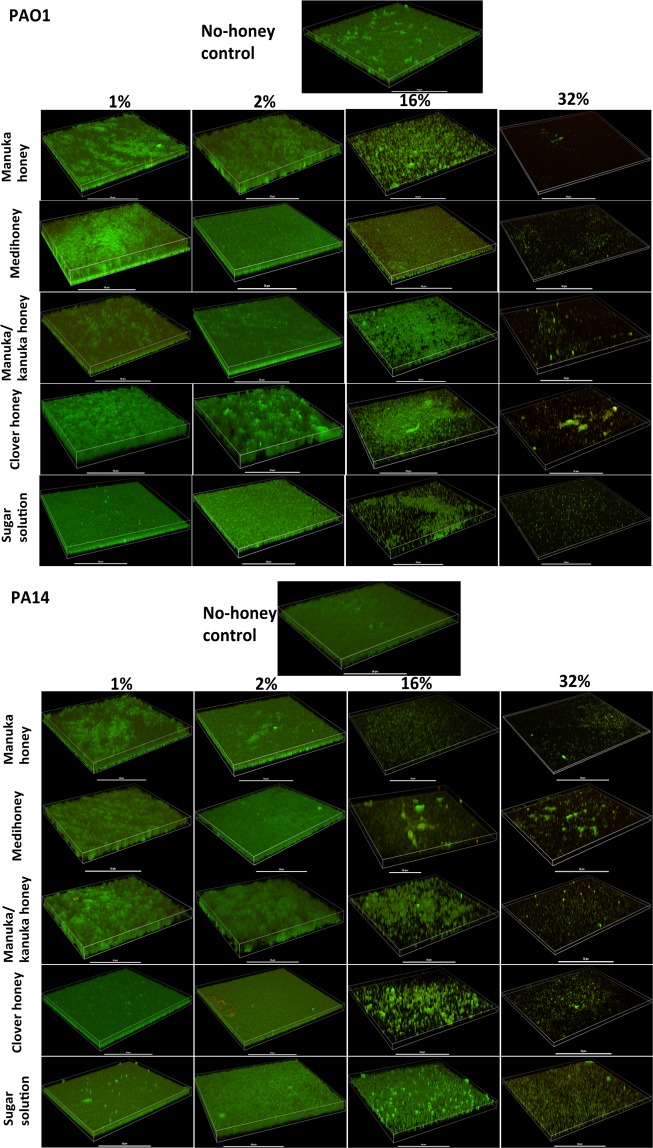

The effect of the NZ honeys and the control sugar solution at sub-inhibitory (1% and 2%) and inhibitory (16% and 32%) concentrations on established biofilms was further examined using confocal laser scanning microscropy (CLSM) to visualise the biofilms and assess viability within the biofilm (Fig. 3). At concentrations of 16%, the total amount of cells was visibly decreased and more dead cells (red; stained with propidium iodide) were observed (Fig. 3). At 32%, all treatments caused a substantial visual reduction in the amount of live cell lawn (green; stained with Syto9), with fewer live or attached cells at the imaged surface area. These results are consistent with the observations in the biofilm eradication assay, where the tested honeys and sugar solution significantly decreased the established P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3.

Visualisation of established P. aeruginosa biofilms treated with different honeys. 3-D images produced by confocal laser scanning microscopy of established P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 biofilms, following treatment with sub-inhibitory (1 and 2%) and inhibitory (16 and 32%) concentrations of NZ honeys (manuka, Medihoney, manuka-kanuka, or clover) or control sugar solution. Biofilms were stained with Syto9 (green = viable cells) and propidium iodine (red = dead cells). Scale bar represents 50 µm.

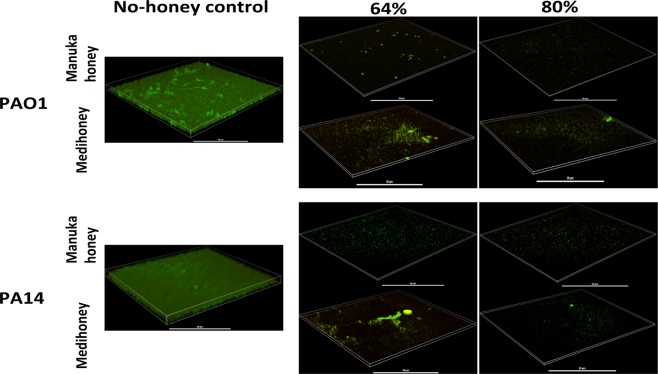

Higher concentrations (64% and 80%) of the two medical-grade honeys (manuka honey and Medihoney) were also tested on established P. aeruginosa biofilms (Fig. 4) to better reflect the clinical situation, where these honeys are used at high concentrations as an antibacterial wound treatment. CLSM imaging showed that these medical-grade honeys were effective at reducing established P. aeruginosa biofilms, with very few cells remaining on the imaged surface relative to the untreated control (Fig. 4). Visually, there were also fewer fluorescently stained cells remaining attached on the imaged surfaces, compared to 32% of the same honey treatment (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of high concentrations of manuka and Medihoney on established P. aeruginosa biofilms. 3-D images produced by confocal laser scanning microscopy of established P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 biofilms, following treatment with high concentrations (64 and 80%) of manuka honey and Medihoney. Biofilms were stained with Syto9 (green = viable cells) and propidium iodine (red = dead cells). Scale bar represents 50 µm.

Effect of MGO on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and eradication

Methylglyoxal (MGO) makes a substantial contribution to the activity of manuka and related honeys, and has previously been demonstrated to be effective at both inhibiting biofilm formation and eradicating established P. aeruginosa biofilms41. To determine the contribution of MGO to the biofilm prevention and eradication activity of the manuka-type honeys in this study, MGO was tested both with and without the addition of the sugar solution at concentrations representative of those in each of the manuka-type honeys (Table 1).

Some reduction in biofilm formation was observed using MGO alone or in combination with sugar (Fig. 5), however, the MGO solutions did not reproduce the inhibitory effects observed with the manuka-type honeys (Fig. 1). The biggest reduction in biofilm formation was observed when MGO solution, with or without sugar, was used at the concentration equivalent to manuka honey, i.e. 900 mg/kg (Fig. 5). Biofilm formation was reduced by up to 50% when MGO alone was used at a concentration of 16% honey equivalence (Fig. 5). MGO with sugar used at a concentration of 32% honey equivalence resulted in a 75% reduction in biofilm formation (Fig. 5). In contrast, >95% inhibition was seen with the corresponding honey at the equivalent MGO concentrations (Fig. 1). The addition of MGO to the sugar solution also appeared to counteract the inhibitory effect observed for the sugar solution alone for biofilm formation (Figs. 1 and 5), and some sub-inhibitory concentrations of MGO (alone or in combination with sugar solution) enhanced biofilm formation.

Figure 5.

Effect of MGO on biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa. Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa PAO1 (A) and PA14 (B) in the presence of MGO and MGO plus sugar solution. MGO concentrations correspond to those present in the manuka-type honeys: 100 mg/kg as in manuka-kanuka honey, 700 mg/kg as in Medihoney, and 900 mg/kg as in manuka honey. Biofilm formation is expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control, which is set at 100%. Results presented are mean values from three biological replicates, all performed in triplicate ± SD.

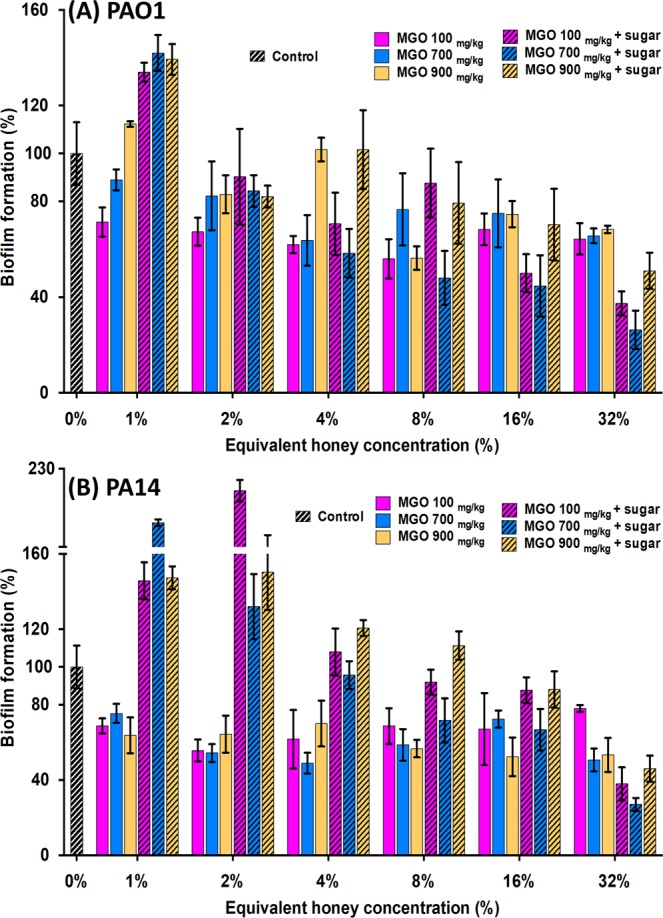

As with the biofilm inhibition assays, treatment with MGO at concentrations similar to those present in the manuka-type honeys did not reduce the biofilm biomass to the same degree as the corresponding honey (Figs. 6 and 2). While there was some reduction in biofilm mass by 32% MGO alone or in combination with sugar (Fig. 6), this was markedly less than that of the manuka-type honeys at this concentration (Fig. 2).

Figure 6.

Effect of MGO on established P. aeruginosa biofilms. P. aeruginosa PAO1 (A) and PA14 (B) biofilms treated with MGO, with and without sugar solution. MGO concentrations used correspond to those in the manuka-type honeys: 100 mg/kg as in manuka-kanuka honey, 700 mg/kg as in MedihoneyM, and 900 mg/kg as in manuka honey. Biofilm formation is expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control, which is set at 100%. Results presented are mean values from three biological replicates, all performed in triplicate ± SD.

Discussion

Chronic wounds harbour bacterial populations that commonly exist as biofilms41, which are known to be far more tolerant to antibiotics than planktonic bacteria56,57. Ideally, effective treatments of chronic wounds should have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity effective against multi-drug resistant wound pathogens, as well as the ability to reduce or eradicate existing biofilms in the wound, while simultaneously preventing the formation of new biofilms. The need for new chronic wound treatments coupled with the rise in antibiotic resistance has prompted renewed interest in complex, natural products with antimicrobial activity–like honey, and the use of manuka-type honeys for the treatment of chronic wounds is especially promising. Here we show that manuka-type honeys have the ability to prevent and eradicate biofilms formed by the common wound pathogen, P. aeruginosa, notorious for being recalcitrant to conventional treatments.

The manuka-type honeys tested inhibited P. aeruginosa planktonic cell growth and the formation of biofilms, and also eliminated established biofilms at concentrations that could be maintained in wound dressing (8–32%; Table 2 and Figs. 1–4). This is in general agreement with the literature as several studies have reported on the effectiveness of manuka-type honeys against P. aeruginosa33,34. However, the amount of honey required to inhibit P. aeruginosa growth and biofilm formation varies between these studies, which report concentrations of honey between 12–50% as being inhibitory. In comparison, the growth and biofilm inhibitory concentration against P. aeruginosa in our study was generally at 16% honey. These differences are likely to be due to the different strains of P. aeruginosa tested in the studies and their relative biofilm-forming abilities as this is known to vary among strains. Differences between specific manuka-type honeys used e.g. the age, floral source, or processing and storage conditions of the honey samples can also affect the inhibitory action observed16,58,59. Most studies examining the antimicrobial effects of honey do not thoroughly characterise the honeys tested, despite the fact that the chemical composition and specifically the concentrations of the major antibacterial components (hydrogen peroxide, antimicrobial peptides, phenolics, or MGO) vary from one honey type to another and significantly affect the antimicrobial activity20–22,60. This highlights the importance of characterising the honey types tested, for example, by determining the levels of their key antibacterial components for ease of comparison between studies and for determining the most appropriate honeys for use in the clinic. However, fully characterising honey can be very difficult due to its complex nature, and even when done individual components, or combinations of these, may not necessarily align to inhibition very well.

MGO is believed to be one of the major antibacterial and anti-biofilm components of manuka honey, with demonstrated inhibitory effects against a range of bacteria41. In previous studies, the anti-biofilm activity of manuka-type honey against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa has been largely attributed to MGO22,41,61. Under the conditions used here however, MGO treatment at concentrations broadly corresponding to those in the manuka-type honeys, tested alone or in the presence of sugar, did not induce similar biofilm inhibitory or eliminatory effects (Figs. 5 and 6). This suggests that MGO is not the main driver of the anti-biofilm effects of manuka-type honey. Indeed our results indicate that MGO contributes very little to the anti-P. aeruginosa biofilm activity (Figs. 5 and 6). Although our results do not agree with previous studies, this is likely to be because of the different P. aeruginosa strains used and more directly related to the differences in the MGO concentrations tested. Previous studies showing successful P. aeruginosa biofilm inhibition by MGO alone have generally used much higher concentrations of MGO (between 1800–7300 mg/kg)41 than used here (288 mg/kg, equivalent to 32% manuka honey). The high concentrations of MGO used in other studies are well above the highest reported levels of MGO in manuka-type honeys (~1100 mg/kg)23,62 and may have toxic effects on host cells63. Our findings suggest that P. aeruginosa is markedly more tolerant to MGO than other common wound pathogens, such as S. aureus49, consistent with previous reports41. This is likely to be due to the ability of P. aeruginosa to detoxify MGO in several ways via the glyoxylase system (composed of glyoxalase I and II) and P. aeruginosa is known to have three fully functional glyoxylase I homologues, whereas most bacteria contain one glyoxylase I gene64.

Under the conditions tested here, sugar alone was generally almost as effective as the honey treatments (Figs. 1 and 2). However, since wound infections are polymicrobial, and we and others have previously shown that sugar is not as effective as manuka-type honeys against other common wound pathogens such as S. aureus38, sugar is not likely to be an equal or better option for chronic wound treatment, especially when the added wound healing and anti-inflammatory properties of honey13 are taken into account. The contribution of the sugar component of honey to the anti-biofilm effects observed here may be due to high osmolarity or to a nutrient effect, such as through changes to central carbon metabolism. Sugar in honey has been linked to disrupted quorum sensing in P. aeruginosa65, and high concentrations of fructose in honey or sugar solutions have been found to prevent P. aeruginosa biofilm formation66. It is also possible that P. aeruginosa is sensitive to the sugar solution due to its deficit in sugar transporters67. Adding osmotic pressure (e.g. via extra salt or sugar) is known to affect the swarming ability of bacteria and defects in swarming coincide with deficiencies in biofilm formation68. So, we tested the effect of the honeys and sugar solution on the swarming ability of P. aeruginosa to determine whether the anti-biofilm effect could be explained via this mechanism, however our results did not indicate this to be the case (Supplementary Table S2). While all the tested honeys and the sugar solution did affect the swarm colony size in both PA14 and PAO1, the manuka-type honeys showed marked reduction of the swarm size when used at a concentration of 8%, and colony inhibition at 16%, indicating that there are additional components in these honeys contributing to the overall anti-biofilm activity reported here. Future studies investigating how manuka-type honeys affect other mechanisms involved in P. aeruginosa biofilm formation (e.g. swimming motility or quorum sensing), may help to identify key components in honey responsible for its anti-biofilm action. These components could be integrated into wound dressings to test their direct biofilm inhibitory action, as has been done previously using the amino acid tryptophan69, which may provide better mechanistic insights.

While low concentrations (up to 32%) of any of the four honeys or the sugar solution were able to significantly reduce established P. aeruginosa biofilm biomass, these could not completely remove established biofilm (Fig. 3). In clinical practice, the honey concentration in honey-based wound dressings and gels is close to 100%, although there can be some dilution of the honey by wound exudate70. When the two medical-grade manuka-type honeys were tested at concentrations that better represent the concentrations used in clinical practice (64% and 80%), complete removal of established P. aeruginosa biofilms was observed (Fig. 4). Although in vitro studies can only provide insight to the in vivo situation, these results warrant further exploration of honey wound dressings for the treatment of infected chronic wounds.

Honey is an attractive substitute for topical antibiotics not only due to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, but also because previous studies show that a range of bacteria capable of colonising the skin and wounds, including P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli and A. calcoaceticus do not develop resistance to honey, including medical-grade manuka honey30,31. This low propensity for resistance is likely to be due to the complexity of honey, which acts in a multifactorial way to target cells via several antibacterial compounds30. However, honey resistance has only been explored in planktonic cells and not within biofilm cells. Treatment of biofilm-associated chronic wounds often requires continued disruption of biofilms, where multiple doses of antibacterial agents over time are needed that may eventually induce resistance71. Here we tested biofilm cells recovered from sub-inhibitory manuka-type honey treatments for the development of resistance. These biofilm-recovered cells showed a 2-fold increase in MIC and MBIC (Table 1), suggesting that P. aeruginosa may acquire tolerance to honey treatment or that persister P. aeruginosa cells may develop during continued exposure to honey72. Further work is required to determine whether this decreased susceptibility is due to reversible, temporary tolerance or is an acquired state of honey resistance.

This study is the first to test a suite of well-characterised New Zealand honeys, and their key antibacterial components (sugar and MGO) against two P. aeruginosa strains with different biofilm forming abilities using a range of in vitro assays and fluorescent microscopy. We demonstrate that: (1) honey present at relatively low concentrations (up to 32%) compared to those used in honey-based wound dressings (~80–100%) inhibited the ability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilms and significantly reduced established biofilms; (2) the anti-biofilm effect of the manuka-type honeys was largely (but not wholly) driven by the sugar component and not MGO as previously suggested; (3) cells recovered from biofilms treated with sub-inhibitory concentrations of honey had slightly reduced susceptibility to honey; and (4) manuka-type honeys used at clinically obtainable concentrations (64% and 80%) completely eradicated established P. aeruginosa biofilms. Taken together, our results show that when used at appropriate concentrations, wound dressings saturated with manuka-based honey are promising effective treatments for infected chronic wounds, including those containing P. aeruginosa biofilms.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Comvita New Zealand for the supply of the honey samples. This research was funded through an Australian Research Council Linkage Project grant (LP0990949). CLSM was performed at the UTS Microbial Imaging Facility.

Author contributions

E.H., D.C. and C.W. contributed to the conception and design of the work and acquisition for funding; J.L., N.C., M.L., C.B., L.T. contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work. The paper was written by N.C. and J.L., and critically revised by E.H., D.C., C.B., C.W. and L.T.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Competing interests

Comvita New Zealand provided partial funding and materials (honey samples) for the work described in the manuscript. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any financial and non-financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jing Lu and Nural N. Cokcetin.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54576-2.

References

- 1.Sen CK, et al. Human skin wounds: A major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2009;17:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2004;2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James GA, et al. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodey GP, Bolivar R, Fainstein V, Jadeja L. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1983;5:279–313. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heggers JP, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A: its role in retardation of wound healing: the 1992 Lindberg Award. The Journal of burn care & rehabilitation. 1992;13:512–518. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolcott RD, Rhoads DD, Dowd SE. Biofilms and chronic wound inflammation. J Wound Care. 2008;17:333–341. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2008.17.8.30796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gjødsbøl K, et al. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. International Wound Journal. 2006;3:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2006.00159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole K. Multidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organisms. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology. 2001;3:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webber MA, Piddock LJ. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2003;51:9–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Resistance to the Max. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2011;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howell-Jones RS, et al. A review of the microbiology, antibiotic usage and resistance in chronic skin wounds. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2005;55:143–149. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez R. The use of systemic antibiotics in the treatment of chronic wounds. Dermatologic therapy. 2006;19:326–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper R. Honey for wound care in the 21st century. J Wound Care. 2016;25:544–552. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.9.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen KL, Molan PC, Reid GM. The variability of the antibacterial activity of honey. Apiacta. 1991;26:114–121. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molan PC. Why honey is effective as a medicine. 1. Its use in modern medicine. Bee World. 1999;80:80–92. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.1999.11099430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irish, J., Blair, S. & Carter, D. The Antibacterial Activity of Honey Derived from Australian Flora. PLoS ONE6, e18229. 18210.11371/journal.pone.0018229 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Sherlock O, et al. Comparison of the antimicrobial activity of Ulmo honey from Chile and Manuka honey against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;10:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Waili N, Salom K, Al-Ghamdi AA. Honey for wound healing, ulcers, and burns; data supporting its use in clinical practice. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:766–787. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molan PC. The antibacterial activity of honey. 1. The nature of the antibacterial activity. Bee World. 1992;73:5–28. doi: 10.1080/0005772X.1992.11099109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens JM, et al. Phenolic compounds and methylglyoxal in some New Zealand manuka and kanuka honeys. Food Chemistry. 2010;120:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams CJ, et al. Isolation by HPLC and characterisation of the bioactive fraction of New Zealand manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honey. Carbohydrate Research. 2008;343:651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mavric E, Wittmann S, Barth G, Henle T. Identification and quantification of methylglyoxal as the dominant antibacterial constituent of Manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) honeys from New Zealand. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2008;52:483–489. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cokcetin NN, et al. The Antibacterial Activity of Australian Leptospermum Honey Correlates with Methylglyoxal Levels. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0167780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon A, et al. Medical Honey for Wound Care—Still the ‘Latest Resort’? Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: eCAM. 2009;6:165–173. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson, I., Grothier, L. & Amaya, R. A next generation honey dressing: MEDIHONEY® HCS. Wounds UK9 (4), Supplement. Available to download from: www.wounds-uk.com (2013).

- 26.Carter, D. A. et al. Therapeutic manuka honey: no longer so alternative. Frontiers in Microbiology7, 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00569 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Willix DJ, Molan PC, Harfoot CJ. A comparison of the sensitivity of wound-infecting species of bacteria to the antibacterial activity of manuka honey and other honey. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 1992;73:388–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb04993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blair SE, Carter DA. The potential for honey in the management of wounds and infection. Australian Infection Control. 2005;10:24–31. doi: 10.1071/HI05024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.George NM, Cutting KF. Antibacterial honey (Medihoney): in-vitro activity against clinical isolates of MRSA, VRE, and other multiresistant Gram-negative organisms including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Wounds- A Compendium of Clinical Research and Practice. 2007;19:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blair S, Cokcetin N, Harry E, Carter D. The unusual antibacterial activity of medical-grade Leptospermum honey: antibacterial spectrum, resistance and transcriptome analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:1199–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0763-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper R, Jenkins L, Henriques A, Duggan R, Burton N. Absence of bacterial resistance to medical-grade manuka honey. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2010;29:1237–1241. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0992-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cooper R, Jenkins L, Hooper S. Inhibition of biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Medihoney in vitro. Journal of Wound Care. 2014;23:93–104. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2014.23.3.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alandejani T, Marsan J, Ferris W, Slinger R, Chan F. Effectiveness of honey on Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merckoll P, Jonassen TO, Vad ME, Jeansson SL, Melby KK. Bacteria, biofilm and honey: a study of the effects of honey on ‘planktonic’ and biofilm-embedded chronic wound bacteria. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2009;41:341–347. doi: 10.1080/00365540902849383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maddocks SE, Lopez MS, Rowlands RS, Cooper RA. Manuka honey inhibits the development of Streptococcus pyogenes biofilms and causes reduced expression of two fibronectin binding proteins. Microbiology. 2012;158:781–790. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.053959-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maddocks SE, Jenkins RE, Rowlands RS, Purdy KJ, Cooper RA. Manuka honey inhibits adhesion and invasion of medically important wound bacteria in vitro. Future Microbiology. 2013;8:1523–1536. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majtan, J., Bohova, J., Horniackova, M., Klaudiny, J. & Majtan, V. Anti-biofilm Effects of Honey Against Wound Pathogens Proteus mirabilis and Enterobacter cloacae. Phytother Res, 10.1002/ptr.4957 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Lu J, et al. Manuka-type honeys can eradicate biofilms produced by Staphylococcus aureus strains with different biofilm-forming abilities. PeerJ. 2014;2:e326. doi: 10.7717/peerj.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halstead FD, et al. In vitro activity of an engineered honey, medical-grade honeys, and antimicrobial wound dressings against biofilm-producing clinical bacterial isolates. Journal of Wound Care. 2016;25:93–102. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2016.25.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, M. Y. et al. Rifampicin-Manuka Honey Combinations Are Superior to Other Antibiotic-Manuka Honey Combinations in Eradicating Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms. Frontiers in Microbiology8, 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02653 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Kilty SJ, Duval M, Chan FT, Ferris W, Slinger R. Methylglyoxal: (active agent of manuka honey) in vitro activity against bacterial biofilms. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology. 2011;1:348–350. doi: 10.1002/alr.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen KL, Molan PC. The sensitivity of mastitis-causing bacteria to the antibacterial activity of honey. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research. 1997;40:537–540. doi: 10.1080/00288233.1997.9513276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin SM, Molan PC, Cursons RT. The controlled in vitro susceptibility of gastrointestinal pathogens to the antibacterial effect of manuka honey. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2011;30:569–574. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anthimidou E, Mossialos D. Antibacterial Activity of Greek and Cypriot Honeys Against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Comparison to Manuka Honey. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2012;16:42–47. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carnwath R, Graham EM, Reynolds K, Pollock PJ. The antimicrobial activity of honey against common equine wound bacterial isolates. Veterinary journal (London, England: 1997) 2014;199:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu, M. et al. Antibiotic-specific differences in the response of Staphylococcus aureus to treatment with antimicrobials combined with manuka honey. Frontiers in Microbiology5, 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00779 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Holloway BW. Genetic recombination in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of general microbiology. 1955;13:572–581. doi: 10.1099/00221287-13-3-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahme LG, et al. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science. 1995;268:1899–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.7604262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu J, et al. The Effect of New Zealand Kanuka, Manuka and Clover Honeys on Bacterial Growth Dynamics and Cellular Morphology Varies According to the Species. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.CLSI. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard - Tenth Edition. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 19–29 (2015).

- 51.Merritt, J. H., Kadouri, D. E. & O’Toole, G. A. Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Current protocols in microbiology Chapter 1, Unit 1B.1, 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01b01s00 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Junker LM, Clardy J. High-Throughput Screens for Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Development. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2007;51:3582–3590. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00506-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haddix PL, et al. Kinetic analysis of growth rate, ATP, and pigmentation suggests an energy-spilling function for the pigment prodigiosin of Serratia marcescens. Journal of bacteriology. 2008;190:7453–7463. doi: 10.1128/jb.00909-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cars O, Odenholt-Tornqvist I. The post-antibiotic sub-MIC effect in vitro and in vivo. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 1993;31(Suppl D):159–166. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_D.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang JC, Hsueh PR, Young C. In vitro postantibiotic effect of roxithromycin and erythromycin against gram-positive cocci. Zhonghua Minguo wei sheng wu ji mian yi xue za zhi = Chinese journal of microbiology and immunology. 1992;25:276–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Percival SL, et al. A review of the scientific evidence for biofilms in wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:647–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao G, et al. Biofilms and Inflammation in Chronic Wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2013;2:389–399. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elbanna K, et al. Impact of floral sources and processing on the antimicrobial activities of different unifloral honeys. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2014;4:194–200. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60504-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen C, Campbell LT, Blair SE, Carter DA. The effect of standard heat and filtration processing procedures on antimicrobial activity and hydrogen peroxide levels in honey. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:265. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kwakman PHS, et al. Medical-grade honey enriched with antimicrobial peptides has enhanced activity against antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:251–257. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1077-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jervis-Bardy J, Foreman A, Bray S, Tan L, Wormald PJ. Methylglyoxal-infused honey mimics the anti-Staphylococcus aureus biofilm activity of manuka honey: potential implication in chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1104–1107. doi: 10.1002/lary.21717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Windsor, S., Pappalardo, M., Brooks, P., Williams, S. & Manley-Harris, M. A convenient new analysis of dihydroxyacetone and methylglyoxal applied to Australian Leptospermum honeys. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy4 (2012).

- 63.Allaman I, Bélanger M, Magistretti PJ. Methylglyoxal, the dark side of glycolysis. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2015;9:23–23. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sukdeo N, Honek JF. Pseudomonas aeruginosa contains multiple glyoxalase I-encoding genes from both metal activation classes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 2007;1774:756–763. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang R, Starkey M, Hazan R, Rahme LG. Honey’s Ability to Counter Bacterial Infections Arises from Both Bactericidal Compounds and QS Inhibition. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2012;3:144. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lerrer B, Zinger-Yosovich KD, Avrahami B, Gilboa-Garber N. Honey and royal jelly, like human milk, abrogate lectin-dependent infection-preceding Pseudomonas aeruginosa adhesion. ISME Journal: Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology. 2007;1:149–155. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stover CK, et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yeung AT, et al. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is controlled by a broad spectrum of transcriptional regulators, including MetR. Journal of bacteriology. 2009;191:5592–5602. doi: 10.1128/jb.00157-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brandenburg KS, et al. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation on wound dressings. Wound Repair Regen. 2015;23:842–854. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schepartz AI. The glucose oxidase of honey. III. Kinetics and stoichiometry of the reaction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1965;99:161–164. doi: 10.1016/S0926-6593(65)80015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bradley BH, Cunningham M. Biofilms in chronic wounds and the potential role of negative pressure wound therapy: an integrative review. Journal of wound, ostomy, and continence nursing: official publication of The Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society. 2013;40:143–149. doi: 10.1097/WON.0b013e31827e8481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Camplin AL, Maddocks SE. Manuka honey treatment of biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa results in the emergence of isolates with increased honey resistance. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2014;13:19–19. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).