Abstract

Background

Second cancers are an adverse outcome experienced by childhood cancer survivors. We quantify the risk and correlates of a second cancer in Canadians diagnosed with a first cancer prior to age 20 years.

Methods

Using death-linked Canadian Cancer Registry data, a population-based cohort diagnosed with a first cancer between 1992 and 2014, prior to age 20 years, were followed for occurrence of a second cancer to the end of 2014. We estimate standardized incidence ratios (SIR), absolute excess risks (AER), cumulative probabilities, and hazard ratios (HR).

Findings

22,635 people contributed 204,309•1 person-years of follow-up. Overall risk of a second cancer was 6•5 (95% CI: 5•8–7•1) times greater than expected resulting in an AER of 16•5 (14•4–18•5) cancers per 10,000 person-years and a 4•8% (3•8%–6•0%) cumulative probability of a second cancer at 22•6 years of follow-up. SIRs decreased with increasing age at diagnosis and time since diagnosis; were larger in more recent calendar periods of diagnosis; and varied by type of first cancer. Large SIRs in the first year after diagnosis and in those diagnosed in 2010–2014 were partly associated with changing registry practices. For the whole cohort, factors associated with the hazard of a second cancer included: being female vs. male [HR = 1•439 (95%CI: 1•179–1•760)]; being diagnosed in 2005–2014 vs. 1992–2004 [2•084 (1•598–2•719)]; having synchronous first cancers [4•814 (2•042–9•509)]; and being diagnosed with certain types of cancer. Factors varied, however, by type of first cancer.

Interpretation

Risks of a second cancer are not equally distributed and can be impacted by changes in registry practice and the methods used to define second cancers.

Keywords: Second cancer, Child, Youth, Adolescent, SIR, Population-based, Canada, Proportional hazards regression

Research in context

Evidence before this study

We conducted a Pubmed search on Oct 3, 2018 to identify population-based national research examining the risk of a second cancer in Canadians diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence (0–19 years). Our primary search string was: “SIR” AND “cancer” AND “second primary” AND (“child” OR “youth” OR “young adult”) AND “Canada”. We also conducted the search excluding the term “Canada” to identify recent similar international research. Both searches were performed again on January 3, 2019 to identify more recently published research. We also reviewed the references of selected articles and monitored publication content notifications of prominent cancer journals. Only papers published in English were reviewed. We identified only two Canadian studies.

Added value of this study

Unlike past Canadian research, we included 12 of Canada's 13 jurisdictions, accounting for 77.0% of the Canadian population in 2014, and we examined the impact of synchronous first cancers on subsequent risk. The greater coverage increased cohort size and mitigated losses to follow-up due to migration across the country — an issue that disproportionately affects paediatric cancer cases. In addition to characterizing the risk in the cohort as a whole, we characterize risk by type of first cancer and draw attention to types of cancer accounting for the greatest absolute excess risk.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings provide more up-to-date, comprehensive estimates of the risk of a second cancer experienced by Canadians diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence. We demonstrate that the risk, type and correlates of a second cancer differ by type of first cancer and can be impacted by changes in registry practice and the methods used to define second cancers. Consequently, future research should use clinically relevant surveillance definitions for second cancers and focus on long-term follow-up of large cohorts composed of a specific type of cancer to comprehensively and accurately characterize their risk and its correlates while acknowledging differences in registry practices across jurisdictions and over time.

1. Introduction

In Canada, rising childhood cancer incidence [1] and high five-year observed survival [2] are contributing to a growing population of young cancer survivors who are at elevated risk of developing subsequent cancers. Studies of population-based cohorts of American and Canadian paediatric cancer survivors have estimated a six-fold or greater increase in the risk of subsequent cancers relative to the general population over a maximum of 27 years of follow-up [3,4]. Long-term monitoring of the risk of subsequent cancers is essential to understanding the full burden of cancer; disentangling the causes of cancer (e.g. genes, lifestyle, past cancer treatment); and, informing treatment protocols, patient management, and counselling. Such research has already resulted in less use of radiation therapy and reduced doses of radiation therapy, alkylating agents, anthracyclines, and epipodophyllotoxins [5].

Our study examines the risk of a second cancer in Canadians diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence (age 0–19 years). Unlike past Canadian research [3,6], we included 12 of Canada's 13 jurisdictions, accounting for 77•0% of the Canadian population in 2014 [7], and we examined the impact of synchronous first cancers on subsequent risk. The greater coverage increased cohort size and mitigated losses to follow-up due to migration across the country — an issue reported to affect paediatric cases (aged 0–19) three times more than all cancer cases combined (14% vs 5%) [8].

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

Our primary data source is the death-linked Canadian Cancer Registry (CCR) analytic file wherein tumours are classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) and compiled using the International Rules for Multiple Primary Cancers [9]. This file includes malignant primary tumours (excluding not otherwise specified, epithelial, basal and squamous skin cancer histologies) and in situ bladder tumours. Note that, by virtue of their behaviour (ICD-O behaviour 0 or 1), non-malignant central nervous system tumours are not included. According to the International Rules for Multiple Primary Cancers, a primary cancer is one that originates in a primary site or tissue and is not an extension, recurrence, or metastasis. These rules consider site of origin and histology, and generally result in fewer primaries per person relative to other rules that acknowledge additional factors such as behaviour, laterality and timing [10] — an important factor to consider when comparing findings across studies. For simplicity, hereafter, the term cancer refers to primary cancer. The CCR is a dynamic, person-oriented administrative database capturing demographic and clinical information on Canadian residents diagnosed with primary tumours since January 1, 1992 [11]. Vital status follow-up to December 31, 2014 was obtained through linkage with the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database [12] within Statistics Canada's Social Data Linkage Environment [13] allowing for a maximum of 23 years of follow-up. Cancers diagnosed in Quebec residents and deaths occurring in Quebec are excluded from the analytic file because of data sharing agreements. Consequently, estimates for Canada exclude Quebec but, for brevity, are hereafter referred to as estimates for Canada. Missing month and/or day of birth, cancer diagnosis, and death were imputed using all available information for a person such that the imputed date represents the average of all potential dates. In the data file used for analyses, the proportion of dates imputed were 51•0%, 1•1%, and 0•0%, respectively. More than 99% of the imputed dates of birth were the result of share restrictions prohibiting release of day of birth.

The urban/rural status and national neighbourhood income quintile of the child's or youth's residence at time of diagnosis of the first cancer was obtained by linking residential postal code, as registered in the CCR, with the appropriate vintage of the Postal Code Conversion File Plus [14]. Residences situated in census metropolitan/agglomeration areas were classified as urban while all others were classified as “small town/rural” [15]. National neighbourhood income quintile is based on neighbourhood household income, as measured in the Census, adjusted for household size. The top two quintiles formed the higher income group while the remaining quintiles comprised the lower income group. Population estimates were based on census data adjusted for census net undercoverage [7].

Since our study involved the analysis of secondary data and did not involve contacting cohort members, consideration and approval by an ethics review board was not required. Our data sharing agreement prohibits us from making the microdata publicly available.

2.2. Cohort and cancer definitions

The cohort consisted of children and youth with a first cancer diagnosed between 1992 and 2014, prior to age 20 years, and with person-time at risk during the available follow-up period (1992 to 2014, inclusive). Types of cancer were defined using the International Classification of Childhood Cancer updated for new hematopoietic codes introduced by the World Health Organization in 2008 [16]. In situ bladder cancers were classified with invasive cancers of the bladder, as is generally done with adults, while all other unclassified cancers were grouped as “not elsewhere classified”. Due to small numbers, all analyses are presented using the main diagnostic groups. Table 1 lists the official and abbreviated diagnostic group names. For brevity, the latter are used hereafter.

Table 1.

International classification of childhood cancer main diagnostic groups.

| Main diagnostic group | Abbreviation | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Leukaemias, myeloproliferative diseases, and myelodysplastic diseases | Leukaemia |

| II | Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial neoplasms | Lymphoma |

| III | CNS and miscellaneous intracranial and intraspinal neoplasms | CNS |

| IV | Neuroblastoma and other peripheral nervous cell tumours | Peripheral nervous cell |

| V | Retinoblastoma | Retinoblastoma |

| VI | Renal tumours | Renal |

| VII | Hepatic tumours | Hepatic |

| VIII | Malignant bone tumours | Bone |

| IX | Soft tissue and other extraosseous sarcomas | Soft tissue |

| X | Germ cell tumours, trophoblastic tumours, and neoplasms of gonads | Germ cell |

| XI | Other malignant epithelial neoplasms and malignant melanomas | Carcinomas |

| XII | Other and unspecified malignant neoplasms | Other |

Note. This classification includes new hematopoietic codes introduced by the World Health Organization in 2008 [16]. CNS = central nervous system.

Since comprehensive examinations at diagnosis of the first cancer can inflate the estimated risk of a second cancer in early follow-up, cancers diagnosed within 60 days of the first registered cancer for a person were considered part of the initial diagnostic work-up (i.e. synchronous cancers), irrespective of diagnostic group. Thus, a child or youth was not at risk for a second cancer during this 60 day period which was removed from his/her person-time at risk for a second cancer. The next cancer diagnosed after the synchronous period was considered a second cancer. Again, additional cancers diagnosed within 60 days of the second cancer were considered part of the diagnostic work-up for the second cancer. Although somewhat arbitrary, a two-month/60 day synchronous period has been used previously [17], [18], [19].

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Standardized incidence ratios (SIR) and absolute excess risk (AER)

The cohort was followed from the end of the synchronous period to the earliest of three events: date of diagnosis of a second cancer, date of death, or end of follow-up (December 31, 2014). Consequently, only those surviving the synchronous period and contributing person-time prior to the end of 2014 are included in this study. Person-time at risk for a second cancer was grouped by sex, attained 5-year age group (0–4, 5–9,…, 80–84, 85+) and attained calendar period (1992–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2014). Standard rates for first cancers were based on first cancers registered in the CCR, similarly grouped by sex, age at diagnosis and calendar period of diagnosis, and corresponding population estimates. Synchronous cancers associated with the first cancer registered for a person contributed to the standard rates. Previous research has not necessarily developed standard rates using first cancers only, perhaps because the cohorts were not necessarily limited to persons with first cancers. Since our cohort was selected based on the first cancer registered for a person, standard rates were also based on the first cancer(s) registered for a person. We acknowledge that there is uncertainty in a cancer's true sequence caused by such factors as cancer registry inception date and migration; however, including subsequent cancers would bias upward our standard rates for first cancers in the general population. Standard rates were applied to the cohort's person-time at risk to obtain the expected number of second cancers under the assumption that the risk of second cancers in the cohort is no different than the risk of first cancers in the general population. SIRs are estimated as the observed relative to expected number of second cancers and corresponding confidence intervals assume observed counts are Poisson random variables and expected counts are measured without error.

AER is calculated as the difference between the observed and expected count expressed relative to the corresponding person-years at risk. The standard error of the difference in counts is estimated as the square root of the sum of the counts while the 95% confidence limits assume a normal distribution. These limits, expressed relative to the corresponding person-years at risk, form the 95% confidence interval for the AER [20].

The SIR and AER provide different perspectives. The SIR measures the strength of association between first and second cancers whereas the AER measures the absolute increase in risk of a second cancer. Since a large SIR can translate to a low AER if the background risk in the general population is low, setting priorities using the AER would be more useful if the goal is to reduce the number of excess second cancers. SIRs and AERs (per 10,000 person-years) for all second cancers combined are estimated by sex, age at initial diagnosis (0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years), diagnostic group of first cancer, calendar period of diagnosis (1992–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014), and time since diagnosis (61 days–1 year, >1–5, >5–10, >10). For the cohort as a whole and the larger subgroups diagnosed with certain types of first cancers, SIRs and AERs for specific types of second cancers are also estimated. People with synchronous first or second cancers contributed to estimates for all relevant diagnostic groups. SIRs and AERs were not estimated by rural/urban status or income level because of the lack of readily available corresponding population estimates.

2.3.2. Cumulative probabilities

The cumulative probability of being diagnosed with a second cancer is estimated using the cumulative incidence function [21] and 95% confidence intervals are estimated according to Hosmer, Lemeshow, and May [22]. In the presence of competing risks — in our case death — the cumulative incidence function provides more accurate estimates than the complement of the Kaplan-Meier function which overestimates cumulative probability [23], [24], [25]. Cumulative probabilities of a second cancer are estimated by sex, age at initial diagnosis, diagnostic group of first cancer, synchronous first cancers status (yes/no), calendar period of diagnosis, rural/urban residence at diagnosis, and neighbourhood income at diagnosis.

2.3.3. Proportional hazards regression

To identify factors associated with the hazard of a second cancer, Cox proportional hazards regression was performed for the cohort as a whole and for each of the diagnostic groups with adequate second cancer events. Considering the relatively small number of second cancers, we used a forward selection procedure (alpha=0•05 to enter) to identify the most important explanatory variables: sex, age at diagnosis, calendar period of diagnosis, rural/urban residence at diagnosis, neighbourhood income at diagnosis, presence of synchronous first cancers, and, for the cohort as a whole, diagnostic group of first registered cancer. Considered variables were based on past research, data availability, and the desire to assess associations with proximity to healthcare (urban/rural residence), financial resources (neighbourhood income), and severity of initial condition (synchronous first cancers). The algorithm could select from three options for defining age at diagnosis (0–9 and 10–19 years; 0–4, 5–9, 10–14 and 15–19 years; continuous) and two options for defining calendar period of diagnosis (1992–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009 and 2010–2014; 1992–2004 and 2005–2014). To maximize the number of records used in the regression, missing rural/urban status of residence at time of diagnosis (369 people) was classified as rural if the postal code indicated a rural route (i.e. second character is zero); otherwise, the more prevalent urban category was assumed. Missing income information at diagnosis (509 people) was classified in the more prevalent lower income category. Once the explanatory variables were selected, violations of the proportional hazards assumption were evaluated by examining the magnitude and significance of Pearson correlation coefficients between time to second cancer and unweighted/weighted/rescaled Schoenfeld residuals; and examining plots of smoothed rescaled Schoenfeld residuals versus time to identify changes in the effect of a variable over time. Variables violating the proportional hazards assumption were addressed by adding interaction terms with time. Firth's bias correction was used for monotone likelihoods [24,26]. Only models with at least one selected explanatory variable and at least five second cancers per explanatory variable are presented [27].

To identify factors associated with the cumulative incidence of a second cancer in the presence of the competing event of death, proportional subdistribution hazards regression was used [23,24]. Whereas Cox proportional hazards regression examines the instantaneous rate of a second cancer among those still at risk, proportional subdistribution hazards regression is useful for predicting cumulative incidence and thus may be more clinically relevant [23]. It is possible for a variable to have different effects on the cumulative incidence and hazard of an event [23]. For example, a factor that has no causal effect on second cancers may be associated with the cumulative incidence of a second cancer because the factor reduces the risk of the competing event of death and thus increases the opportunity for a second cancer. The modelling approach was the same as that described for Cox proportional hazards regression.

2.3.4. Confidentiality measures

Small counts of second cancers limited analyses to a Canadian level. For confidentiality reasons, all reported observed counts are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. Estimates based on actual counts less than five are suppressed. Unless specifically stated, all other reported estimates are based on actual data.

2.3.5. Software

Analyses were performed using SAS 9•3 [28]. Cumulative probabilities were estimated using the SAS macro %CIF [25] while proportional and nonproportional subdistribution hazards regression were performed using the SAS macro %PSHREG [24].

3. Results

A total of 22,635 children and youth contributed 204,309•1 person-years of follow-up between January 1, 1992 and December 31, 2014 (Table 2). The cohort included slightly more males than females (53•7% vs 46•3%) and higher proportions diagnosed at the extremes of the age-range of interest — over 30% in each of the 0–4 and 15–19 years age groups. For about 60% of the children and youth, the first registered cancer was leukaemia, lymphoma or originated in the central nervous system. Less than 1•0% had more than one cancer diagnosed during the synchronous period. At the time of diagnosis, 80•9% lived in an urban area and 46•6% lived in neighbourhoods classified in the upper two income quintiles. As of Dec 31, 2014, those that had developed a second cancer were more likely to be female, initially diagnosed with certain types of cancer (lymphoma, peripheral nervous cell, bone, and soft tissue), and diagnosed in the more distant past (Table 2). Of the 22,635 persons in the cohort, 395 (1•7%) were diagnosed with a second cancer and 3915 died (17•3%) with median time to event of 6•7 years (IQR: 1•5–13•0) and 1•3 years (IQR: 0•6–2•8), respectively (Table 3). With respect to migration, 3•5% of those diagnosed with a second cancer were residing in a different province/territory and 3•3% of decedents died outside their original province/territory of residence or had an unknown place of death.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence by second cancer status, 1992–2014.

| Total cohort | Second cancer status | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||||

| N | % Na | PY | % PY | N | % N | N | % N | p-valueb | |

| Total cohort | 22,635 | 100•0 | 204,309•1 | 100•0 | 22,240 | 100•0 | 395 | 100•0 | |

| Sex | 0•0002 | ||||||||

| males | 12,150 | 53•7 | 108,287•4 | 53•0 | 11,975 | 53•8 | 175 | 44•3 | |

| females | 10,480 | 46•3 | 96,021•7 | 47•0 | 10,265 | 46•2 | 220 | 55•7 | |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | 0•6914 | ||||||||

| 0–4 | 6915 | 30•6 | 63,623•3 | 31•1 | 6795 | 30•6 | 115 | 29•1 | |

| 5–9 | 3960 | 17•5 | 36,049•4 | 17•6 | 3895 | 17•5 | 60 | 15•2 | |

| 10–14 | 4305 | 19•0 | 38,482•1 | 18•8 | 4225 | 19•0 | 80 | 20•3 | |

| 15–19 | 7460 | 33•0 | 66,154•3 | 32•4 | 7325 | 32•9 | 135 | 34•2 | |

| Diagnostic group of first cancerc | <0•0001 | ||||||||

| leukaemia | 5965 | 26•4 | 53,713•3 | 26•3 | 5900 | 26•5 | 65 | 16•5 | |

| lymphoma | 3800 | 16•8 | 36,545•5 | 17•9 | 3715 | 16•7 | 90 | 22•8 | |

| CNS | 3660 | 16•2 | 30,163•8 | 14•8 | 3610 | 16•2 | 55 | 13•9 | |

| peripheral nervous cell | 1060 | 4•7 | 8519•9 | 4•2 | 1030 | 4•6 | 30 | 7•6 | |

| retinoblastoma | 370 | 1•6 | 4234•5 | 2•1 | 360 | 1•6 | 5 | 1•3 | |

| renal | 885 | 3•9 | 9304•8 | 4•6 | 875 | 3•9 | 10 | 2•5 | |

| hepatic | 265 | 1•2 | 2171•1 | 1•1 | 265 | 1•2 | —d | — | |

| bone | 1205 | 5•3 | 9338•4 | 4•6 | 1170 | 5•3 | 35 | 8•9 | |

| soft tissue | 1420 | 6•3 | 11,616•2 | 5•7 | 1370 | 6•2 | 45 | 11•4 | |

| germ cell | 1475 | 6•5 | 14,669•3 | 7•2 | 1455 | 6•5 | 20 | 5•1 | |

| carcinomas | 2195 | 9•7 | 20,951•7 | 10•3 | 2160 | 9•7 | 30 | 7•6 | |

| other/NEC | 330 | 1•5 | 3080•5 | 1•5 | 325 | 1•5 | 5 | 1•3 | |

| Synchronous first cancerse | 0•0002 | ||||||||

| no | 22,525 | 99.5 | 203,854.5 | 99.8 | 22,135 | 99.5 | 390 | 98.7 | |

| yes | 115 | 0.5 | 454.6 | 0.2 | 105 | 0.5 | 10 | 2.5 | |

| Neighbourhood income at diagnosisf | 0•1162 | ||||||||

| lower | 12,090 | 53•4 | 109,713•5 | 53•7 | 11,865 | 53•3 | 230 | 58•2 | |

| higher | 10,540 | 46•6 | 94,595•7 | 46•3 | 10,375 | 46•7 | 170 | 43•0 | |

| Rural/urban residence at diagnosis | 0•8638 | ||||||||

| rural | 4325 | 19•1 | 41,036•8 | 20•1 | 4245 | 19•1 | 80 | 20•3 | |

| urban | 18,310 | 80•9 | 163,272•3 | 79•9 | 17,990 | 80•9 | 320 | 81•0 | |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | <0•0001 | ||||||||

| 1992–1994 | 2735 | 12•1 | 44,845•4 | 21•9 | 2655 | 11•9 | 85 | 21•5 | |

| 1995–1999 | 4760 | 21•0 | 65,550•9 | 32•1 | 4645 | 20•9 | 115 | 29•1 | |

| 2000–2004 | 4770 | 21•1 | 49,705•8 | 24•3 | 4700 | 21•1 | 75 | 19•0 | |

| 2005–2009 | 5005 | 22•1 | 31,942•4 | 15•6 | 4935 | 22•2 | 75 | 19•0 | |

| 2010–2014 | 5365 | 23•7 | 12,264•6 | 6•0 | 5310 | 23•9 | 55 | 13•9 | |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | —g | ||||||||

| 61days-1 | 22,635 | 100•0 | 18,007•0 | 8•8 | 22,235 | 100•0 | 395 | 100•0 | |

| >1–5 | 20,380 | 90•0 | 67,452•8 | 33•0 | 20,050 | 90•2 | 330 | 83•5 | |

| >5–10 | 14,175 | 62•6 | 59,040•3 | 28•9 | 13,940 | 62•7 | 230 | 58•2 | |

| >10 | 9610 | 42•5 | 59,809•1 | 29•3 | 9465 | 42•6 | 145 | 36•7 | |

Note. For confidentiality, the number of people are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. Counts may not sum to total due to random rounding. CNS = central nervous system; N=number of people at risk at the start of follow-up; NEC = not elsewhere classified; PY=person-years.

Based on rounded N and first row totals.

Based on Pearson's chi-square test.

Diagnostic groups are defined according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (see Table 1). Children and youth diagnosed with synchronous first cancers are classified based on the first registered cancer.

Fewer than five second cancers.

Synchronous first cancers are defined as more than one cancer diagnosed during the 60 day synchronous period.

Lower income includes the lowest three neighbourhood income quintiles while higher income includes the upper two neighbourhood income quintiles.

Not applicable as cohort members can contribute to multiple follow-up categories.

Table 3.

Follow-up status of Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence, 1992–2014.

| Status | N | %a | Percentiles of time to event (years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 50th | 75th | |||

| Censored | 18,325 | 81•0 | 4•6 | 10•0 | 16•1 |

| Second cancer | 395 | 1•7 | 1•5 | 6•7 | 13•0 |

| Died | 3915 | 17•3 | 0•6 | 1•3 | 2•8 |

| Total | 22,635 | 100•0 | 2•6 | 7•8 | 14•8 |

Note. For confidentiality, the numbers of people are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. N=number of people experiencing the outcome.

Based on rounded N.

During the follow-up period, about 400 second cancers were diagnosed producing a SIR of 6•5 (95% CI: 5•8–7•1) and an AER of 16•5 (95% CI: 14•4–18•5) cancers per 10,000 person-years of follow-up (Table 4). Less than five cohort members had more than one cancer diagnosed in the second synchronous period. The SIR was highest for those aged 0–4 years at diagnosis (SIR = 010•6, 95% CI: 8•8–12•7) and lowest in those aged 15–19 years at diagnosis (SIR = 4•3, 95% CI: 3•6–5•1). For the cohort as a whole, sites at greatest risk of second cancers included: peripheral nervous cell (SIR = 22•8, 95% CI: 12•4–38•2); soft tissue (SIR = 15•5, 95% CI: 11•3–20•7); and bone (SIR = 14•2, 95% CI: 9•4–20•7). However, the diagnostic group accounting for the greatest AER (6•0, 95% CI: 4•8–7•3) and greatest proportion (37•5%) of second cancers was carcinomas — the most common sites being thyroid (50•7% of cases), breast (13•7%), oral cavity and pharynx (8•2%), colon and rectum (6•2%), and skin (6•2%) (data not shown). Children and youth first diagnosed with cancers of the peripheral nervous cell (SIR = 20•1, 95% CI: 13•7–28•6), soft tissue (SIR = 13•2, 95% CI: 9•8–17•6), bone (SIR = 12•2, 95% CI: 8•6–16•7), and retinoblastoma (SIR = 10•8, 95% CI: 4•7–21•2) experienced rates of second cancers that were more than 10 times greater than expected. The SIR is substantially higher for cohort members diagnosed in more recent calendar periods (2005–2009 and 2010–2014). At least part of this is attributed to differences in the distribution of follow-up time across calendar periods of diagnosis. Specifically, persons diagnosed more recently will have a greater proportion of their follow-up time occurring within the first year of diagnosis when the SIR is 20•4 (95% CI: 15•8 to 25•8).

Table 4.

SIRs and AERs for second cancers in Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence by demographic, diagnostic, and temporal characteristics, 1992–2014.

| N | PYs | Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 400 | 6•5 (5•8–7•1) | 16•5 (14•4 to 18•5) |

| Sex | |||||

| males | 12,150 | 108,287•4 | 175 | 6•0 (5•2–7•0) | 13•6 (11•0 to 16•2) |

| females | 10,480 | 96,021•7 | 220 | 6•9 (6•0–7•8) | 19•7 (16•4 to 22•9) |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | |||||

| 0–4 | 6915 | 63,623•3 | 115 | 10•6 (8•8–12•7) | 16•5 (13•0 to 20•0) |

| 5–9 | 3960 | 36,049•4 | 65 | 9•0 (6•9–11•5) | 15•8 (11•2 to 20•4) |

| 10–14 | 4305 | 38,482•1 | 85 | 6•8 (5•4–8•5) | 18•0 (13•0 to 22•9) |

| 15–19 | 7460 | 66,154•3 | 135 | 4•3 (3•6–5•1) | 15•9 (12•1 to 19•8) |

| Diagnostic group of second cancera | |||||

| leukaemia | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 60 | 8•5 (6•5–11•0) | 2•5 (1•8 to 3•3) |

| lymphoma | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 35 | 3•2 (2•2–4•5) | 1•1 (0•5 to1•7) |

| CNS | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 35 | 7•3 (5•2–10•1) | 1•6 (1•0 to 2•2) |

| peripheral nervous cell | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 15 | 22•8 (12•4–38•2) | 0•7 (0•3 to 1•0) |

| retinoblastoma | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | —b | — | — |

| renal | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 10 | 7•9 (3•6–14•9) | 0•4 (0•1 to 0•7) |

| hepatic | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | — | — | — |

| bone | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 25 | 14•2 (9•4–20•7) | 1•2 (0•7 to 1•7) |

| soft tissue | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 45 | 15•5 (11•3–20•7) | 2•1 (1•4 to 2•7) |

| germ cell | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 15 | 1•7 (0•9–2•8) | 0•3 (−0•2 to 0•7) |

| carcinomas | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 150 | 6•3 (5•3–7•4) | 6•0 (4•8 to 7•3) |

| other | 22,635 | 204,309•1 | 10 | 9•1 (4•4–16•8) | 0•4 (0•1 to 0•8) |

| Diagnostic group of first cancera | |||||

| leukaemia | 5965 | 53,721•6 | 60 | 5•1 (3•9–6•5) | 9•3 (6•1 to 12•4) |

| lymphoma | 3805 | 36,570•4 | 85 | 6•3 (5•1–7•8) | 20•3 (14•9 to 25•7) |

| CNS | 3670 | 30,185•9 | 50 | 6•6 (4•9–8•6) | 14•6 (9•6 to 19•6) |

| peripheral nervous cell | 1060 | 8526•7 | 30 | 20•1 (13•7–28•6) | 34•6 (21•4 to 47•7) |

| retinoblastoma | 370 | 4238•4 | 5 | 10•8 (4•7–21•2) | 17•1 (3•4 to 30•8) |

| renal | 885 | 9304•8 | 10 | 7•1 (3•8–12•2) | 12•0 (3•9 to 20•1) |

| hepatic | 265 | 2171•1 | — | — | — |

| bone | 1210 | 9349•2 | 35 | 12•2 (8•6–16•7) | 37•3 (23•9 to 50•7) |

| soft tissue | 1445 | 11,711•2 | 50 | 13•2 (9•8–17•6) | 37•9 (25•9 to 49•9) |

| germ cell | 1480 | 14,674•4 | 20 | 3•7 (2•3–5•6) | 10•4 (3•5 to 17•3) |

| carcinomas | 2195 | 20,958•1 | 30 | 3•2 (2•2–4•6) | 10•2 (4•2 to 16•2) |

| other | 295 | 2922•0 | — | — | — |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | |||||

| 1992–1994 | 2735 | 44,845•4 | 85 | 5•0 (4•0–6•1) | 15•3 (10•9 to 19•8) |

| 1995–1999 | 4760 | 65,550•9 | 115 | 5•4 (4•5–6•5) | 14•2 (10•7 to 17•7) |

| 2000–2004 | 4770 | 49,705•8 | 75 | 5•6 (4•4–7•0) | 12•4 (8•7 to 16•1) |

| 2005–2009 | 5005 | 31,942•4 | 70 | 9•9 (7•8–12•5) | 20•3 (14•8 to 25•7) |

| 2010–2014 | 5365 | 12,264•6 | 50 | 19•5 (14•5–25•6) | 39•4 (27•7 to 51•2) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | |||||

| 61 days −1 year | 22,635 | 18,007•0 | 65 | 20•4 (15•8–25•8) | 35•9 (26•7 to 45•1) |

| >1–5 | 20,380 | 67,452•8 | 95 | 7•3 (5•9–8•9) | 12•5 (9•5 to 15•6) |

| >5–10 | 14,175 | 59,040•3 | 80 | 5•3 (4•2–6•6) | 11•3 (8•0 to 14•6) |

| >10 | 9610 | 59,809•1 | 150 | 5•1 (4•3–6•0) | 20•2 (15•8 to 24•6) |

Note. For confidentiality, the number of people and observed second cancers are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. Counts may not sum to total due to random rounding. AER=absolute excess risk; CI=confidence interval; CNS=central nervous system; N=number of people at risk at the start of follow-up; Obs=observed number of second cancers; PY=person-years; SIR=standardized incidence ratio.

Diagnostic groups are defined according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (see Table 1). People can appear in more than one diagnostic category if they are diagnosed with synchronous cancers.

Fewer than five second cancers.

Although sparse data prevents definitive statements, the relationship between SIRs and demographic, temporal and diagnostic characteristics varied by type of first cancer (Table 5). As examples, for children and youth with leukaemia as their first cancer, SIRs did not vary substantially by age at diagnosis and were greatest for the diagnostic groups central nervous system and carcinomas; first cancers in peripheral nervous tissue markedly increased the risk of another peripheral nervous cell cancer (SIR = 169•0, 95% CI: 90•0–288•9); first cancers in bone considerably increased the risk of leukaemia (SIR = 59•5, 95% CI: 34•0–96•6) and soft tissue cancers (SIR = 69•1, 95% CI: 33•1–127•1); and, first cancers in soft tissue noticeably increased the risk of bone (SIR = 107•3, 95% CI: 55•5–187•5) and soft tissue (SIR = 58•7, 95% CI: 28•1–107•9) cancers. A drill down analysis of the group with first and second cancers classified as “peripheral nervous cell” (N = 15) indicated all first and second cancers were classified as neuroblastomas and ganglioneuroblastomas (ICD-O histology codes 9500 or 9490) and follow-up time to second cancer was relatively short (median = 1.3 years, IQR: 0.5–2.3). Nonetheless, the second cancers are classified as new primaries because site of origin adequately differed according to the International Rules for Multiple Primary Cancers. Children and youth diagnosed with first cancers affecting peripheral nervous tissue, bone or soft tissue experienced an excess absolute risk of 35+ cancers per 10,000 person-years.

Table 5.

SIRs and AERs for second cancers in Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence by selected types of first cancer, 1992–2014.

| Diagnostic group of first cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukaemia (N = 5965; PYs=53,721•6) |

Lymphoma (N = 3805; PYs = 36,570•4) |

|||||

| Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

|

| Total cohort | 60 | 5•1 (3•9–6•5) | 9•3 (6•1 to 12•4) | 85 | 6•3 (5•1–7•8) | 20•3 (14•9 to 25•7) |

| Sex | ||||||

| males | 30 | 4•6 (3•1–6•6) | 8•0 (4•0 to 12•1) | 45 | 6•7 (4•9–9•0) | 18•3 (11•6 to 24•9) |

| females | 30 | 5•5 (3•8–7•8) | 10•7 (5•8 to 15•7) | 40 | 6•0 (4•3–8•1) | 23•1 (14•0 to 32•2) |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 20 | 4•3 (2•6–6•6) | 5•6 (1•9 to 9•2) | 10 | 19•5 (9•4–35•9) | 32•4 (10•7 to 54•0) |

| 5–9 | 20 | 6•7 (3•9–10•8) | 11•1 (4•5 to 17•8) | 10 | 9•1 (4•2–17•3) | 16•3 (3•7 to 28•9) |

| 10–14 | 15 | 5•6 (3•0–9•5) | 13•5 (3•8 to 23•2) | 25 | 9•5 (6•2–13•9) | 26•2 (14•4 to 38•1) |

| 15–19 | 10 | 4•5 (2•4–7•6) | 15•1 (3•4 to 26•9) | 40 | 4•5 (3•2–6•0) | 16•8 (9•7 to 24•0) |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1992–1994 | 20 | 7•2 (4•6–10•9) | 17•5 (8•6 to 26•3) | 20 | 5•7 (3•6–8•6) | 23•7 (11•0 to 36•5) |

| 1995–1999 | 15 | 2•9 (1•5–5•0) | 4•5 (−0•0 to 9•0) | 30 | 6•8 (4•6–9•6) | 24•1 (13•6 to 34•6) |

| 2000–2004 | 15 | 4•5 (2•3–7•9) | 7•2 (1•4 to 13•0) | 15 | 4•5 (2•4–7•5) | 11•5 (2•9 to 20•1) |

| 2005–2009 | 5 | 5•1 (2•2–10•1) | 7•6 (0•5 to 14•8) | 10 | 6•1 (2•8–11•6) | 13•6 (2•1 to 25•1) |

| 2010–2014 | 5 | 10•4 (4•2–21•4) | 18•4 (2•6 to 34•1) | 10 | 19•7 (9•5–36•3) | 41•9 (13•9 to 69•9) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 61 days −1 year | 5 | 8•1 (3•3–16•8) | 12•9 (1•4 to 24•5) | 10 | 22•7 (12•1–38•8) | 40•6 (17•0 to 64•3) |

| >1–5 | 5 | 3•0 (1•4–5•8) | 3•4 (−0•4 to 7•2) | 10 | 3•3 (1•5–6•3) | 5•2 (−0•3 to 10•8) |

| >5–10 | 15 | 6•1 (3•6–9•7) | 9•7 (3•9 to 15•5) | 15 | 4•1 (2•3–6•8) | 10•5 (2•7 to 18•4) |

| >10 | 25 | 5•1 (3•4–7•4) | 14•5 (7•2 to 21•8) | 50 | 7•3 (5•5–9•7) | 41•1 (27•1 to 55•0) |

| Diagnostic group of second cancera | ||||||

| leukaemia | 5 | 3•1 (1•1–6•7) | 0•8 (−0•3 to 1•8) | 10 | 8•2 (3•8–15•6) | 2•2 (0•5 to 3•9) |

| lymphoma | 5 | 2•8 (1•0–6•0) | 0•7 (−0•3 to 1•8) | 10 | 4•4 (2•1–8•1) | 2•1 (0•2 to 4•0) |

| CNS | 10 | 9•4 (5•0–16•0) | 2•2 (0•8 to 3•5) | –b | – | – |

| peripheral nervous cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| retinoblastoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| renal | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| hepatic | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| bone | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| soft tissue | – | – | – | 5 | 8•3 (2•7–19•4) | 1•2 (−0•1 to 2•5) |

| germ cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| carcinomas | 30 | 8•5 (5•6–12•2) | 4•6 (2•6 to 6•6) | 55 | 9•0 (6•8–11•7) | 13•1 (9•0 to 17•3) |

| other | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Diagnostic group of first cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS (N = 3670; PYs = 30,185•9) |

Peripheral nervous cell (N = 1060; PYs = 8526•7) |

|||||

| Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

|

| Total cohort | 50 | 6•6 (4•9–8•6) | 14•6 (9•6 to 19•6) | 30 | 20•1 (13•7–28•6) | 34•6 (21•4 to 47•7) |

| Sex | ||||||

| males | 20 | 5•5 (3•5–8•4) | 11•2 (5•0 to 17•3) | 15 | 17•6 (9•6–29•5) | 30•6 (13•1 to 48•1) |

| females | 30 | 7•6 (5•1–10•9) | 18•6 (10•4 to 26•7) | 15 | 22•9 (13•3–36•6) | 38•6 (19•0 to 58•1) |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 20 | 15•5 (9•7–23•5) | 24•9 (13•4 to 36•4) | 25 | 19•8 (12•8–29•3) | 32•6 (18•8 to 46•3) |

| 5–9 | 15 | 7•5 (4•0–12•8) | 12•8 (4•3 to 21•4) | – | – | – |

| 10–14 | 5 | 3•4 (1•5–6•6) | 7•3 (−0•9 to 15•4) | – | – | – |

| 15–19 | 10 | 3•8 (1•7–7•1) | 12•2 (−0•0 to 24•5) | – | – | – |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1992–1994 | 10 | 3•4 (1•5–6•8) | 8•2 (−0•9 to 17•3) | – | – | – |

| 1995–1999 | 20 | 7•1 (4•3–11•1) | 16•8 (7•4 to 26•2) | 10 | 16•1 (7•0–31•8) | 27•5 (6•6 to 48•4) |

| 2000–2004 | 5 | 3•6 (1•3–7•8) | 6•1 (−1•5 to 13•7) | – | – | – |

| 2005–2009 | 15 | 15•1 (8•2–25•3) | 27•9 (11•7 to 44•0) | 10 | 32•9 (15•1–62•5) | 56•2 (17•8 to 94•6) |

| 2010–2014 | 5 | 15•4 (5•0–35•8) | 27•2 (0•9 to 53•4) | 10 | 69•0 (29•8–136•0) | 148•3 (43•3 to 253•3) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–1 | 10 | 19•0 (8•7–36•1) | 30•0 (8•8 to 51•2) | 5 | 46•7 (20•2–92•0) | 92•8 (26•4 to 159•1) |

| >1–5 | 10 | 7•0 (3•6–12•2) | 10•3 (3•0 to 17•6) | 10 | 22•2 (11•4–38•7) | 38•2 (15•1 to 61•4) |

| >5–10 | 15 | 6•8 (3•6–11•6) | 12•9 (4•1 to 21•7) | 5 | 15•7 (5•1–36•6) | 19•7 (0•7 to 38•7) |

| >10 | 20 | 4•7 (2•8–7•5) | 16•1 (5•7 to 26•5) | 5 | 11•8 (4•3–25•7) | 23•8 (2•1 to 45•4) |

| Diagnostic group of second cancer | ||||||

| leukaemia | 10 | 6•0 (2•2–13•0) | 1•7 (−0•1 to 3•4) | 10 | 17•0 (6•8–35•0) | 7•7 (1•5 to 14•0) |

| lymphoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CNS | 10 | 11•9 (5•5–22•6) | 2•7 (0•7 to 4•8) | – | – | – |

| peripheral nervous cell | – | – | – | 15 | 169•0 (90•0–288•9) | 15•2 (6•8 to 23•5) |

| retinoblastoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| renal | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| hepatic | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| bone | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| soft tissue | 10 | 27•2 (13•6–48•7) | 3•5 (1•3 to 5•7) | – | – | – |

| germ cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| carcinomas | 15 | 4•6 (2•4–8•1) | 3•1 (0•6 to 5•6) | – | – | – |

| other | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Diagnostic group of first cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone (N = 1210; PYs = 9349•2) |

Soft tissue (N = 1445; PYs = 11,711•2) |

|||||

| Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

|

| Total cohort | 35 | 12•2 (8•6–16•7) | 37•3 (23•9 to 50•7) | 50 | 13•2 (9•8–17•6) | 37•9 (25•9 to 49•9) |

| Sex | ||||||

| males | 15 | 10•8 (6•3–17•3) | 30•0 (13•6 to 46•4) | 25 | 13•0 (8•2–19•4) | 33•2 (17•9 to 48•4) |

| females | 20 | 13•6 (8•4–20•7) | 46•3 (24•1 to 68•4) | 25 | 13•5 (8•7–20•0) | 43•5 (24•4 to 62•6) |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | – | – | – | 15 | 34•7 (19•8–56•4) | 58•7 (28•7 to 88•8) |

| 5–9 | – | – | – | 10 | 15•9 (6•8–31•2) | 29•5 (7•0 to 52•1) |

| 10–14 | 15 | 13•1 (7•2–22•0) | 37•7 (15•5 to 59•9) | 15 | 15•0 (8•0–25•7) | 44•6 (17•8 to 71•5) |

| 15–19 | 20 | 12•0 (7•2–18•8) | 48•7 (23•9 to 73•6) | 15 | 6•1 (3•1–11•0) | 24•2 (5•8 to 42•6) |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1992–1994 | 5 | 6•1 (2•2–13•3) | 22•4 (−0•7 to 45•5) | 15 | 9•9 (4•9–17•7) | 33•9 (10•5 to 57•3) |

| 1995–1999 | 5 | 7•3 (3•1–14•4) | 22•8 (3•3 to 42•4) | 10 | 7•9 (3•8–14•5) | 23•2 (5•7 to 40•8) |

| 2000–2004 | 10 | 18•7 (9•3–33•4) | 49•7 (17•9 to 81•6) | 10 | 16•3 (8•4–28•5) | 41•8 (15•8 to 67•7) |

| 2005–2009 | 10 | 31•8 (15•9–56•9) | 73•0 (27•8 to 118•3) | 10 | 22•2 (9•6–43•7) | 47•0 (12•1 to 81•8) |

| 2010–2014 | – | – | – | 5 | 47•5 (19•1–98•0) | 95•3 (22•4 to 168•2) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–1 | – | – | – | 15 | 64•2 (34•2–109•8) | 113•4 (50•3 to 176•4) |

| >1–5 | 20 | 29•9 (18•0–46•8) | 58•6 (30•9 to 86•3) | 15 | 18•8 (10•3–31•5) | 34•8 (15•0 to 54•6) |

| >5–10 | 10 | 8•0 (2•9–17•4) | 20•7 (0•6 to 40•7) | 10 | 11•4 (5•5–21•0) | 28•0 (8•1 to 47•8) |

| >10 | 10 | 6•4 (3•0–11•7) | 31•1 (6•5 to 55•7) | 10 | 6•1 (3•1–10•9) | 26•2 (6•2 to 46•2) |

| Diagnostic group of second cancer | ||||||

| leukaemia | 15 | 59•5 (34•0–96•6) | 16•8 (8•4 to 25•3) | 5 | 13•0 (4•2–30•2) | 3•9 (0•1 to 7•8) |

| lymphoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CNS | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| peripheral nervous cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| retinoblastoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| renal | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| hepatic | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| bone | – | – | – | 15 | 107•3 (55•5–187•5) | 10•2 (4•3 to 16•0) |

| soft tissue | 10 | 69•1 (33•1–127•1) | 10•5 (3•9 to 17•2) | 10 | 58•7 (28•1–107•9) | 8•4 (3•1 to 13•7) |

| germ cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| carcinomas | 10 | 6•4 (2•8–12•7) | 7•2 (0•9 to 13•6) | 10 | 8•7 (4•5–15•2) | 9•1 (2•9 to 15•2) |

| other | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Diagnostic group of first cancer | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germ cell (N = 1480; PYs = 14,674•4) |

Carcinomas (N = 2195; PYs = 20,958•1) |

|||||

| Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

Obs | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) per 10,000 PYs |

|

| Total cohort | 20 | 3•7 (2•3–5•6) | 10•4 (3•5 to 17•3) | 30 | 3•2 (2•2–4•6) | 10•2 (4•2 to 16•2) |

| Sex | ||||||

| males | 10 | 3•4 (1•8–6•0) | 8•9 (0•8 to 17•0) | 5 | 1•9 (0•6–4•5) | 3•4 (−4•3 to 11•1) |

| females | 10 | 4•1 (1•9–7•8) | 13•3 (0•5 to 26•1) | 25 | 3•7 (2•4–5•4) | 13•6 (5•5 to 21•7) |

| Age group at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–4 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5–9 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10–14 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15–19 | 15 | 3•7 (2•1–5•9) | 12•2 (2•9 to 21•5) | 20 | 2•7 (1•7–4•1) | 8•9 (2•0 to 15•8) |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1992–1994 | – | – | – | 5 | 1•9 (0•6–4•4) | 5•4 (−7•2 to 18•0) |

| 1995–1999 | 10 | 4•1 (1•8–8•1) | 12•8 (−0•3 to 25•9) | 10 | 2•8 (1•3–5•3) | 9•3 (−1•7 to 20•4) |

| 2000–2004 | 5 | 4•2 (1•4–9•8) | 11•0 (−3•1 to 25•1) | 5 | 3•1 (1•2–6•3) | 8•6 (−2•3 to 19•4) |

| 2005–2009 | – | – | – | 5 | 4•5 (1•5–10•6) | 10•9 (−2•7 to 24•4) |

| 2010–2014 | – | – | – | 5 | 14•3 (4•7–33•4) | 33•5 (0•8 to 66•1) |

| Time since diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| 0–1 | – | – | – | 10 | 19•4 (7•8–39•9) | 37•6 (7•5 to 67•7) |

| >1–5 | 10 | 6•7 (2•9–13•1) | 14•1 (1•8 to 26•5) | 5 | 3•3 (1•2–7•1) | 5•9 (−1•9 to 13•7) |

| >5–10 | – | – | – | 5 | 3•5 (1•6–6•7) | 10•4 (−0•4 to 21•2) |

| >10 | 5 | 2•9 (1•2–5•7) | 11•9 (−2•8 to 26•6) | 10 | 1•8 (0•8–3•5) | 6•9 (−5•3 to 19•2) |

| Diagnostic group of second cancer | ||||||

| leukaemia | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| lymphoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| CNS | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| peripheral nervous cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| retinoblastoma | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| renal | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| hepatic | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| bone | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| soft tissue | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| germ cell | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| carcinomas | 10 | 3•6 (1•5–7•0) | 3•9 (−0•4 to 8•2) | 15 | 3•5 (2•0–5•5) | 6•1 (1•6 to 10•6) |

| other | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Note. For confidentiality, the number of people and observed second cancers are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. Counts may not sum to total due to random rounding. AER = absolute excess risk; CI = confidence interval; CNS = central nervous system; N = number of people at risk at the start of follow-up; Obs=observed number of second cancers; PY = person-years; SIR = standardized incidence ratio.

Diagnostic groups are defined according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (see Table 1). People can appear in more than one diagnostic category if they are diagnosed with synchronous cancers.

Fewer than five second cancers.

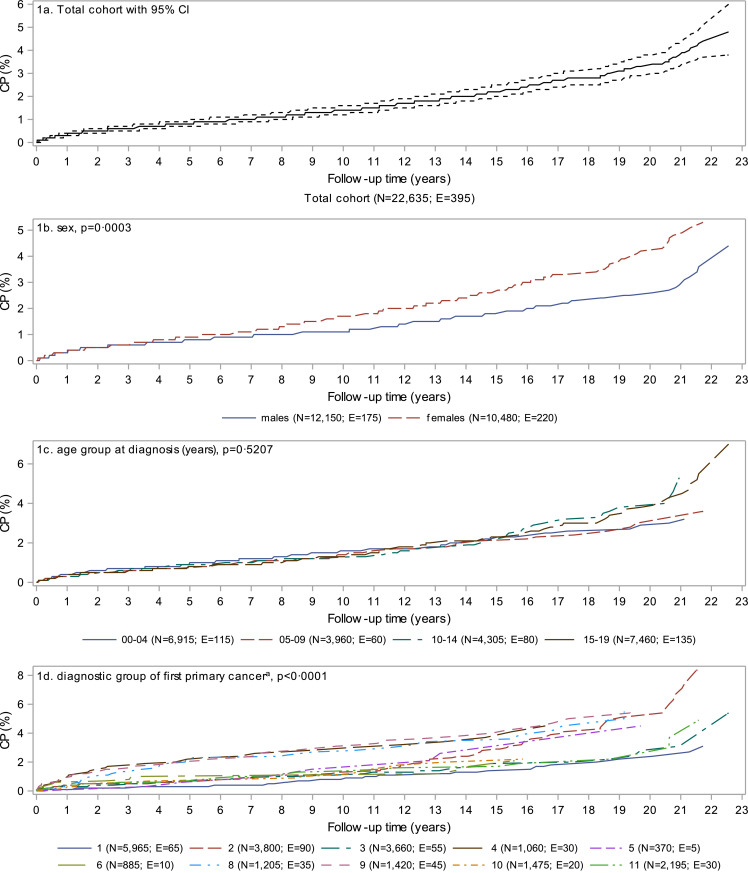

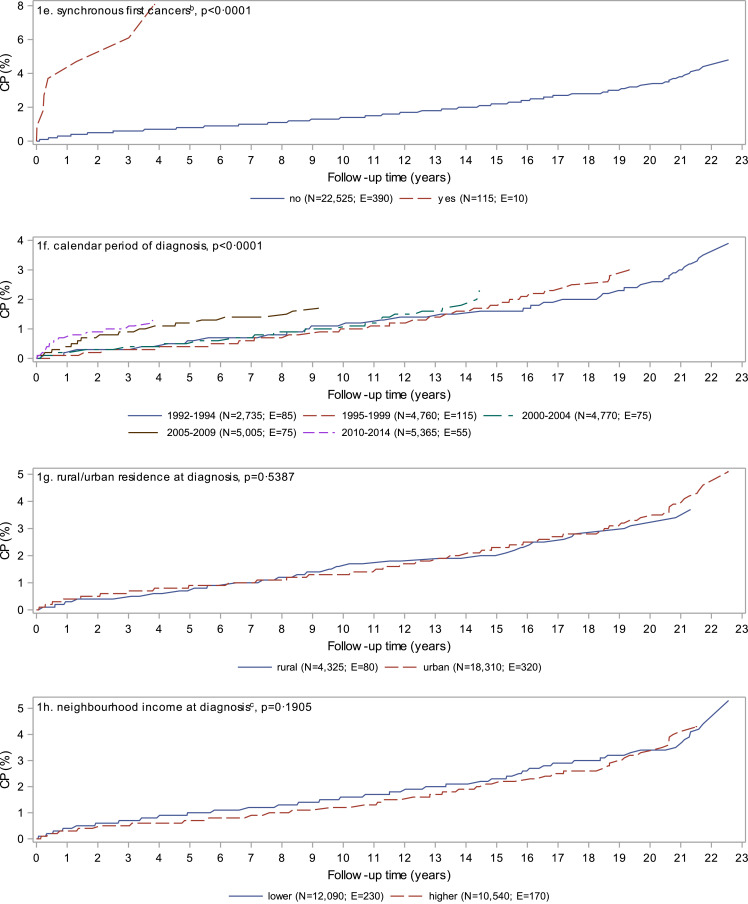

At 22•6 years of follow-up, the cumulative probability of a second cancer was 4•8% (95% CI: 3•8–6•0) (Fig. 1a). Females, those diagnosed with more than one cancer during the initial synchronous period, and those diagnosed in more recent calendar periods had significantly (p < 0•05) higher cumulative probability of a second cancer (Fig. 1b, e, and f). Diagnostic groups with consistently higher cumulative probability over time included soft tissue, peripheral nervous cell, and bone while retinoblastoma and lymphoma started trending higher after 13 years of follow-up (Fig. 1d). Cumulative probability reached 8•1% (95% CI: 3•3–15•6) at about 4 years of follow-up for those diagnosed with synchronous first cancers and 8•4% (95% CI: 6•1–11•1) at about 22 years of follow-up for those first diagnosed with lymphoma.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative probability of a second cancer in Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence, 1992 to 2014. P-values are based on Gray's test for equality of cumulative incidence functions. CI = confidence interval; CP = cumulative probability; E = number of people experiencing a second cancer; N = number of people at risk at the start of follow-up.

aDefined according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (see Table 1): 1–leukeamia; 2–lymphoma; 3–central nervous system; 4–peripheral nervous cell; 5–retinoblastoma; 6-renal; 7–hepatic; 8–bone; 9–soft tissue; 10–germ cell; 11–carcinomas; 12–other. Children and youth diagnosed with multiple cancers during the synchronous period were classified based on the first registered cancer. Diagnostic groups with fewer than five second cancers are suppressed.

bSynchronous first cancers are defined as more than one cancer diagnosed during the 60 day synchronous period.

cLower income includes the lowest three neighbourhood income quintiles while higher income includes the upper two neighbourhood income quintiles.

Whether examining the hazard or cumulative incidence of a second cancer, regression analyses produced similar results (Tables 6 and 7, respectively). For the cohort as a whole, being female, being diagnosed in more recent calendar periods, having synchronous first cancers, and being diagnosed with certain types of cancer significantly increased the hazard (Table 6) and cumulative incidence of a second cancer (Table 7). The difference in magnitude of the hazard ratios and subdistribution hazard ratios are attributable to the competing risk of death. Specifically, relative to their counterparts, females, those diagnosed more recently, those without synchronous first cancers, and several diagnostic groups (lymphomas, retinoblastoma, renal tumours, germ cell tumours, and carcinomas) have a decreased hazard of death and thus an increased opportunity to develop a second cancer (data not shown). Evaluation of the proportional hazards assumption suggested that the hazard of several types of cancer, relative to leukaemia, decreased over time; consequently, the reported regression coefficients represent the average hazard of a second cancer over time relative to those diagnosed with leukemia [26].

Table 6.

Factors associated with the hazard of a second cancer in Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence by selected types of first cancer, 1992–2014.

| Events | Crude HR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 22,635; E = 395) | |||||

| Sex | 0•0007 | 0•0003 | |||

| male | 175 | —a | — | ||

| female | 220 | 1•408 (1•155–1•718) | 1•439 (1•179–1•760) | ||

| Diagnostic group of first cancerb | <0•0001 | <0•0001 | |||

| leukaemia | 60 | — | — | — | — |

| lymphoma | 85 | 2•093 (1•516–2•907) | <0•0001 | 2•125 (1•539–2•953) | <0•0001 |

| CNS | 50 | 1•476 (1•018–2•132) | 0•0380 | 1•478 (1•019–2•134) | 0•0374 |

| peripheral nervous cell | 30 | 3•128 (2•008–4•773) | <0•0001 | 3•020 (1•938–4•609) | <0•0001 |

| retinoblastoma | 5 | 1•427 (0•594–2•907) | 0•3717 | 1•448 (0•603–2•949) | 0•3531 |

| renal | 10 | 1•104 (0•566–1•972) | 0•7555 | 1•102 (0•565–1•970) | 0•7598 |

| hepatic | *c | ||||

| bone | 35 | 3•336 (2•201–4•984) | <0•0001 | 3•322 (2•191–4•965) | <0•0001 |

| soft tissue | 50 | 3•427 (2•335–4•996) | <0•0001 | 3•331 (2•265–4•866) | <0•0001 |

| germ cell | 20 | 1•182 (0•696–1•920) | 0•5171 | 1•223 (0•721–1•988) | 0•4344 |

| carcinomas | 30 | 1•299 (0•834–1•982) | 0•2344 | 1•193 (0•765–1•824) | 0•4216 |

| other/NEC | 5 | 1•489 (0•521–3•352) | 0•3943 | 1•353 (0•473–3•047) | 0•5147 |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | <0•0001 | <0•0001 | |||

| 1992–2004 | 275 | — | — | ||

| 2005–2014 | 120 | 2•100 (1•613–2•738) | 2•084 (1•598–2•719) | ||

| Synchronous first cancersd | <0•0001 | 0•0001 | |||

| no | 390 | — | — | ||

| yes | 5 | 7•567 (3•222–14•770) | 4•814 (2•042–9•509) | ||

| Leukaemia (N = 5965; E = 60) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0016 | 0•0015 | |||

| 1992–1994 | 25 | — | — | ||

| 1995–1999 | 10 | 0•385 (0•181–0•787) | 0•0098 | 0•383 (0•180–0•783) | 0•0095 |

| 2000–2004 | 10 | 0•621 (0•279–1•355) | 0•2671 | 0•595 (0•267–1•298) | 0•2235 |

| 2005–2009 | 10 | 1•077 (0•399–2•775) | 0•8817 | 1•048 (0•388–2•698) | 0•9248 |

| 2010–2014 | 5 | 2•960 (0•903–9•835) | 0•0501 | 2•899 (0•886–9•620) | 0•0527 |

| Age at diagnosis | 60 | 1•073 (1•027–1•119) | 0•0010 | 0•9739 | |

| Age at diagnosis*Time | 0•0421 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis over time (HR per 1 year increase in age) | 0•0421 | ||||

| At 0 years of follow-up | 1•001 (0•922–1•082) | ||||

| 1 year | 1•009 (0•934–1•084) | ||||

| 5 years | 1•039 (0•983–1•094) | ||||

| 10 years | 1•078 (1•032–1•125) | ||||

| 15 years | 1•119 (1•055–1•187) | ||||

| 20 years | 1•161 (1•064–1•268) | ||||

| Lymphoma (N = 3805; E = 85) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0.0039 | 0•0039 | |||

| 1992–1994 | 25 | — | — | ||

| 1995–1999 | 30 | 1•791 (0•957–3•531) | 0•0652 | 1•791 (0•957–3•531) | 0•0652 |

| 2000–2004 | 15 | 1•681 (0•733–3•913) | 0•1766 | 1•681 (0•733–3•913) | 0•1766 |

| 2005–2009 | 10 | 2•826 (1•020–7•775) | 0•0246 | 2•826 (1•020–7•775) | 0•0246 |

| 2010–2014 | 10 | 7•160 (2•398–22•187) | <0•0001 | 7•160 (2•398–22•187) | <0•0001 |

| CNS (N = 3670; E = 50) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0036 | 0•0036 | |||

| 1992–2004 | 30 | — | — | ||

| 2005–2014 | 20 | 2•983 (1•459–6•282) | 2•983 (1•459–6•282) | ||

| Peripheral nervous cell (N = 1060; E = 30) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0021 | 0•0024 | |||

| 1992–2004 | 15 | — | — | ||

| 2005–2014 | 15 | 3•400 (1•480–8•529) | 3•341 (1•451–8•403) | ||

| Synchronous first cancers | <0•0001 | 0•0001 | |||

| no | 30 | — | — | ||

| yes | * | ||||

| Carcinomas (N = 2195; E = 30) | |||||

| Sex | 0•0478 | 0•0362 | |||

| male | 5 | — | — | ||

| female | 25 | 2•627 (1•098–7•769) | 2•811 (1•170–8•330) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 0•0154 | 0•0081 | |||

| 0–9 | 5 | — | — | ||

| 10–19 | 25 | 0•336 (0•147–0•904) | 0•305 (0•133–0•822) | ||

Note. Models are presented when an adequate number of second cancers (i.e. events) occurred and at least one explanatory variable was identified by the forward selection modelling procedure (alpha to enter = 0.05). For confidentiality, counts are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. Counts may not sum to total due to random rounding. CI=confidence interval; CNS=central nervous system; E=number of people diagnosed with a second cancer; HR=hazard ratio; N=number of people included in the model; NEC=not elsewhere classified.

Reference group.

Defined according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (see Table 1). Unclassified cases were combined with the other category.

Fewer than five second cancers.

Synchronous first cancers are defined as more than one cancer diagnosed during the 60 day synchronous period.

Table 7.

Factors associated with the cumulative incidence of a second cancer in Canadians (excluding Quebec) diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence by selected types of first cancer, 1992–2014.

| Events | Crude SHR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted SHR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 22,635; E = 395) | |||||

| Sex | 0•0003 | 0•0001 | |||

| male | 175 | —a | — | ||

| female | 220 | 1•445 (1•186–1•763) | 1•481 (1•213–1•811) | ||

| Diagnostic group of first cancerb | <0•0001 | <0•0001 | |||

| leukaemia | 60 | — | — | ||

| lymphoma | 85 | 2•261 (1•637–3•141) | <0•0001 | 2•294 (1•661–3•188) | <0•0001 |

| CNS | 50 | 1•314 (0•906–1•898) | 0•1464 | 1•309 (0•902–1•890) | 0•1521 |

| peripheral nervous cell | 30 | 2•829 (1•816–4•316) | <0•0001 | 2•730 (1•752–4•168) | <0•0001 |

| retinoblastoma | 5 | 1•715 (0•714–3•493) | 0•1748 | 1•722 (0•717–3•507) | 0•1721 |

| renal | 10 | 1•198 (0•615–2•141) | 0•5673 | 1•188 (0•610–2•124) | 0•5855 |

| hepatic | *c | ||||

| bone | 35 | 2•879 (1•900–4•301) | <0•0001 | 2•840 (1•873–4•245) | <0•0001 |

| soft tissue | 50 | 3•153 (2•149–4•597) | <0•0001 | 3•051 (2•076–4•454) | <0•0001 |

| germ cell | 20 | 1•313 (0•774–2•133) | 0•2895 | 1•349 (0•794–2•192) | 0•2457 |

| carcinomas | 30 | 1•440 (0•924–2•197) | 0•0974 | 1•309 (0•839–2•000) | 0•2208 |

| other/NEC | 5 | 1•502 (0•525–3•381) | 0•3836 | 1•374 (0•480–3•094) | 0•4932 |

| Calendar period of diagnosis | <0•0001 | <0•0001 | |||

| 1992–2004 | 275 | — | — | ||

| 2005–2014 | 120 | 2•178 (1•672–2•841) | 2•148 (1•648–2•804) | ||

| Synchronous first cancersd | <0•0001 | 0•0003 | |||

| no | 390 | — | |||

| yes | 5 | 6•472 (2•764–12•64) | 4•286 (1•818–8•429) | ||

| Leukaemia (N = 5965; E = 60) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0014 | 0•0015 | |||

| 1992–1994 | 25 | — | — | ||

| 1995–1999 | 10 | 0•409 (0•193–0•836) | 0•0156 | 0•410 (0•193–0•837) | 0•0157 |

| 2000–2004 | 10 | 0•707 (0•318–1•544) | 0•4213 | 0•696 (0•312–1•519) | 0•3984 |

| 2005–2009 | 10 | 1•248 (0•461–3•230) | 0•6559 | 1•243 (0•459–3•217) | 0•6617 |

| 2010–2014 | 5 | 3•391 (1•027–11•363) | 0•0291 | 3•375 (1•022–11•308) | 0•0298 |

| Age at diagnosis | 60 | 1•054 (1•010–1•098) | 0•0094 | 0•9436 | |

| Age at diagnosis*Time | 0•0971 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis over time (SHR per 1 year increase in age) | |||||

| At 0 years of follow-up | 0•997 (0•918–1•077) | ||||

| 1 year | 1•003 (0•929–1•077) | ||||

| 5 years | 1•027 (0•972–1•081) | ||||

| 10 years | 1•057 (1•013–1•103) | ||||

| 15 years | 1•089 (1•028–1•154) | ||||

| 20 years | 1•122 (1•030–1•223) | ||||

| Lymphoma (N = 3805; E = 85) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0025 | 0•0025 | |||

| 1992–1994 | 25 | — | — | ||

| 1995–1999 | 30 | 1•854 (0•991–3•656) | 0•0506 | 1•854 (0•991–3•656) | 0•0506 |

| 2000–2004 | 15 | 1•774 (0•774–4•134) | 0•1357 | 1•774 (0•774–4•134) | 0•1357 |

| 2005–2009 | 10 | 3•032 (1•093–8•353) | 0•0165 | 3•032 (1•093–8•353) | 0•0165 |

| 2010–2014 | 10 | 7•666 (2•559–23•839) | <0•0001 | 7•666 (2•559–23•839) | <0•0001 |

| CNS (N = 3670; E = 50) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0027 | 0•0027 | |||

| 1992–2004 | 30 | — | — | ||

| 2005–2014 | 20 | 3•112 (1•518–6•564) | 3•112 (1•518–6•564) | ||

| Peripheral nervous cell (N = 1060; E = 30) | |||||

| Calendar period of diagnosis | 0•0009 | 0•0012 | |||

| 1992–2004 | 15 | — | — | ||

| 2005–2014 | 15 | 3•736 (1•620–9•412) | 3•640 (1•575–9•188) | ||

| Synchronous first cancers | 0•0002 | 0•0004 | |||

| no | 30 | — | — | ||

| yes | * | ||||

| Carcinomas (N = 2195; E = 30) | |||||

| Sex | 0•0387 | 0•0301 | |||

| male | 5 | — | — | ||

| female | 25 | 2•746 (1•147–8•119) | 2•911 (1•213–8•622) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 0•0171 | 0•0094 | |||

| 0–9 | 5 | — | — | ||

| 10–19 | 25 | 0•341 (0•149–0•918) | 0•312 (0•136–0•841) | ||

Note. Models are presented when an adequate number of second cancers (i.e. events) occurred and at least one explanatory variable was identified by the forward selection modelling procedure (alpha to enter = 0.05). For confidentiality, counts are randomly rounded using an unbiased random rounding scheme with a base of five. Counts may not sum to total due to random rounding. CI=confidence interval; CNS=central nervous system; E=number of people diagnosed with a second cancer; N=number of people included in the model; NEC=not elsewhere classified; SHR=subdistribution hazard ratio.

Reference group.

Defined according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (see Table 1). Unclassified cases were combined with the other category.

Fewer than five second cancers.

Synchronous first cancers are defined as more than one cancer diagnosed during the 60 day synchronous period.

Factors associated with a second cancer, which were selected by the modelling process, differed by type of first cancer (Table 6 and 7). The nature of the relationships, however, were consistent except for age. For children and youth diagnosed with leukaemia, being older at time of diagnosis did not significantly impact the hazard of a second cancer in the first five years of follow-up but a one-year increase in age at diagnosis was associated with a 7•8%, 11•9% and 16•1% increase in the hazard of a second cancer at 10, 15, and 20 years after diagnosis (Table 6). Conversely, for children and youth diagnosed with carcinomas, being diagnosed at an older age reduced the hazard of a second cancer by almost 70% (Table 6). The most commonly selected variable across types of first cancer was calendar period of diagnosis and it consistently indicated a higher risk of second cancers for those diagnosed in more recent calendar periods. Rural/urban residence and neighbourhood income level at time of diagnosis were never selected into the models.

3.1. Sensitivity analysis

We were surprised by the large SIRs in the first year of follow-up and most recent calendar period and wondered if changing registry practices of a large Canadian registry were driving the estimates. The Ontario Cancer Registry, which accounted for 52•3% of our cohort, experienced an increase in multiple primaries as a consequence of improved case ascertainment and adoption of the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program multiple primary rules for cases diagnosed 2010 onward in order to be in line with the rest of North America [10,11]. Post hoc drill-down analyses indicated that Ontario accounted for a disproportionate number of second cancers diagnosed during the first year of follow up (80•9%) — the majority of which (56•4%) belonged to children and youth first diagnosed in 2010–2014. Further, Ontario accounted for 74•5% of second cancers among those first diagnosed in 2010–2014. After removing Ontario data from the estimation of SIRs (i.e. person-time at risk, standard rates, observed and expected second cancers), the overall SIR changed from 6•5 (95% CI: 5•8–7•1) to 5•7 (95% CI: 4•9–6•7) but larger changes were seen for the first year of follow up [20•4 (95% CI: 15•8–25•8) to 8•6 (95% CI: 4•6–14•8)] and calendar period 2010–2014 [19•5 (95% CI: 14•5–25•6) to 12•2 (95% CI: 6•5–20•9).

4. Discussion

We found that Canadians diagnosed with a first cancer as children and youth experienced a risk of second cancers that was 6•5 (95% CI: 5•8–7•1) times greater than expected, suffered an AER of 16•5 cancers per 10,000 person-years (95% CI: 14•4–18•5), and demonstrated a 4•8% (95% CI: 3•8–6•0) cumulative probability of a second cancer at 22•6 years of follow-up. The risk of second cancers, the types of second cancers experienced, and the factors associated with being diagnosed with a second cancer differed by type of first cancer. We also found that being diagnosed with synchronous first cancers increased the hazard and cumulative incidence of a second cancer.

Comparing our findings with others is complicated by methodological differences. Others have limited their cohorts to those surviving from 6 months to 5 years after their initial cancer diagnosis [5,6,[29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]]; required cohort consent [5]; used more dated cohorts diagnosed prior to 2000 [5,6,32]; included all subsequent cancers [3,5,17,34,35]; included in situ tumours and/or non-melanoma skin cancers and/or all tumours arising in the brain and central nervous system [29,31,33]; relied on self-report to ascertain subsequent cancers [5,33]; and, have rarely acknowledged or discussed the impact of multiple primary reporting rules [6,17,19,35].

Despite our study occurring in a more recent time period, using more conservative multiple primary rules, including older youth, and being less impacted by migration, many of our findings are generally in line with Inskip et al. [17]. Using a US Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program-based cohort, they found that the risk of subsequent cancers among those first diagnosed at age 0 to 17 years and followed from 1973 to 2000 was 6•07 times greater than expected; that the cohort experienced an AER of 14•96 per 10,000 person-years; and that the cumulative probability of a second cancer was 3•5% (95% CI: 3•0–4•1%) at 25 years. Our study, however, indicated a much higher SIR in the first year after diagnosis compared to Inskip et al. (20•4 vs. 5•39). Considering the earlier time period of diagnosis and follow-up (1973–2000) in the US study, it may be that changes in registry practices over time, advances in diagnostics, and changing treatment patterns are contributing to this difference. Our overall SIR is lower than that of previous research based on an Ontario cohort of paediatric cancer survivors diagnosed between 1985 and 2008 (SIR = 9•9, 95% CI: 8•6–11•4) [3] but methodological differences may explain the disparity. First, Pole et al's [3] research was limited to those diagnosed before the age of 15 and our findings indicate that this younger cohort would be expected to have a higher SIR (Table 4). Second, Pole et al. [3] included all subsequent cancers irrespective of their proximity to the first cancer. Our study found that about 115 children and youth had more than one cancer diagnosed during the initial synchronous period (Table 2) — had we included these as second cancers, the SIR would have increased to at least 8•2. Despite excluding synchronous tumours from our second cancer count, consistent with Pole et al. [3] and others [34,36], we found that a substantial proportion of second cancers occurred within the first 5 years of diagnosis (about 40%, see Table 4); and, similar to Pole et al. [3], that being diagnosed in a more recent calendar period was associated with an increased hazard of a second cancer (Table 6 and 7). Although our SIRs for follow-up periods greater than five years since diagnosis were similar to other studies that limited cohorts to five-year survivors [6,32], such inclusion criteria exclude a substantial proportion of the second cancers experienced during early follow-up — information important to both clinicians and patients.

Consistent with our findings, others have found that females are at greater risk of subsequent cancers than males [5,31,33]; that breast and/or thyroid cancers are among the most common subsequent cancers [33,34]; and that SIRs for subsequent cancers decrease with increasing age at diagnosis and time since diagnosis [6,30,32,33], and increase with more recent diagnosis periods [32].

Unlike past Canadian research, we used a larger, more nationally representative cohort that was less impacted by migration and we examined the impact of synchronous first cancers on subsequent risk. We found that 3–4% of those diagnosed with a second cancer or dying had migrated to another province/territory or had an unknown place of death. For less integrated cancer surveillance jurisdictions, out-migration of paediatric cancer survivors results in missed subsequent cancers and deaths while in-migration of paediatric cancer survivors results in subsequent cancers being diagnosed as first cancers. Both scenarios will bias SIRs downward. Notwithstanding these strengths in our research, several limitations relevant to this field of study should be noted. First, is the impact of medical surveillance in biasing SIRs upward. The increasing risk of second cancers among those with more recent diagnoses combined with breast and thyroid cancers being among the most commonly diagnosed second cancers suggests that surveillance bias and overdiagnosis may be contributing to our findings. Second, is changing cancer registry practices over time. Our sensitivity analysis demonstrated how the adoption of more liberal multiple primary reporting rules (i.e. the National Cancer Institute's Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program multiple primary rules by Ontario) and improved case ascertainment can substantially impact SIRs. Third, is the method used to define a second cancer. We relied on the International Rules for Multiple Primary Cancers combined with a 60 day synchronous period to identify second cancers — an approach that may differ from clinical practice. As an example, a clinician might consider the 15 second peripheral nervous cell cancers among those first diagnosed with peripheral nervous cell cancers (Table 5) as recurrences rather than second cancers. Clinically relevant, standardized surveillance definitions for second cancers, that can be implemented using cancer registry data, would improve the usefulness and comparability of future research. Fourth, artefactually reduced risks of second cancers can be created when treatment of the initial cancer removes one or more organs from risk. Fifth, we could not examine the impact of lifestyle, treatment, and underlying cancer predisposition syndromes on the risk of second cancers because the CCR does not capture such data or it is incomplete. Considering the moderate to strong associations between treatment and the risk of subsequent cancers [3,17,32], and the evolving nature of cancer treatment, capturing treatment details is essential to appropriately interpreting the risk of second cancers. More information on the relationship between lifestyle, type and intensity of treatment, cancer predisposition syndromes, and the risk of second cancers would assist clinicians in lifestyle counselling, reducing the iatrogenicity of treatment, personalizing risk estimates, and optimizing surveillance approaches. Sixth, since the maximum attained age at the end of follow-up was 42 years (median = 19, IQR: 12–25), it is unclear if the risk of second cancers among this cohort will continue to be greater than that caused by aging in the general population. Similar research involving North American and Nordic cohorts has found that the elevated risk of subsequent cancers continues into the fifth, sixth and seventh decades of life [35,37]. Last, the migration of cohort members to Quebec or out of the country may have resulted in missed second cancers and deaths; however, available data suggests the losses would be relatively low. Over the time period of interest, the annual migration rate into Quebec from the rest of the country ranged from 0•09% to 0•16% and the annual emigration rate for Canada, excluding Quebec, ranged from 0•21% to 0•31% among 0 to 42 year olds [7,38,39].

In conclusion, Canadians diagnosed with a first cancer in childhood or adolescence experience increased risk of a second cancer that varies with the initial type of cancer diagnosed, sex, age at diagnosis, calendar period of diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and the presence of synchronous first cancers. Comprehensive data on lifestyle, treatment, underlying cancer predisposition syndromes, and changing registry practices combined with clinically relevant surveillance definitions for second cancers are needed to disentangle the importance of various factors on the risk of a second cancer.

Funding

None. DZ had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualizing the study, interpreting results, drafting the manuscript, and approving the final version. DZ performed the literature searches and analyses.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Xie L., Onysko J., Morrison H. Childhood cancer incidence in Canada: demographic and geographic variation of temporal trends (1992–2010) Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(3):79–115. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.38.3.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canadian Cancer Society's Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics . Canadian Cancer Society; Toronto ON: 2017. Canadian cancer statistics 2017. [cited 2018 Nov 21]. Available from: http://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2017-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pole J.D., Gu L.Y., Kirsh V., Greenberg M.L., Nathan P.C. Subsequent malignant neoplasms in a population-based cohort of pediatric cancer patients: a focus on the first 5 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1585–1592. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraumeni J.F., Curtis R.E., Edwards B.K., Tucker M.A. Introduction. In: Curtis R.E., Freedman D.M., Ron E., editors. New malignancies among cancer survivors: seer cancer registries, 1973-2000. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2006. pp. 1–7. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turcotte L.M., Liu Q., Yasui Y. Temporal trends in treatment and subsequent neoplasm risk among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer, 1970-2015. JAMA. 2017;317(8):814–824. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacArthur A.C., Spinelli J.J., Rogers P.C., Goddard K.J., Phillips N., McBride M.L. Risk of a second malignant neoplasm among 5-Year survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence in British Columbia, Canada. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:453–459. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Statistics Canada [Internet]. Table 17-10-0005-01 population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501.

- 8.Ries L.G., Smith M.A., Gurney J.G., editors. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: united states seer program 1975-1995. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 1999. NIH Pub. No. 99-4649. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritz A., Percy C., Jack A., editors. International classification of diseases for oncology. 3rd ed., 1st revision. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zakaria D., Shaw A. The impact of multiple primary rules on cancer statistics in Canada, 1992 to 2012. J Registry Manag. 2018;45(1):8–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada [Internet]. Canadian cancer registry (CCR) [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3207&Item_Id=1633&lang=en

- 12.Statistics Canada [Internet]. Canadian vital statistics - Death Database (CVSD) [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2&SDDS=3233

- 13.Statistics Canada [Internet]. Social data linkage environment (SDLE) [cited 2018 Oct 4]. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/sdle/index

- 14.Postal code conversion file plus [internet] [cited 2018 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/82F0086X

- 15.du Plessis V., Beshiri R., Bollman R.D., Clemenson H. Definitions of rural. Rural Small Town Canada Anal Bull. 2001;3(3) (Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE) [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute, Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program [internet]. International classification of childhood cancer (ICCC) — ICCC based on ICD-O-3/WHO 2008 [cited 2018 Oct 30]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/iccc/

- 17.Inskip P.D., Ries L.A.G., Cohen R.J., Curtis R.E. New malignancies following childhood cancer. In: Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, editors. New malignancies among cancer survivors: seer cancer registries, 1973-2000. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2006. pp. 465–482. editors. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. [Google Scholar]

- 18.AIRTUM Working Group Italian cancer figures, report 2013: multiple tumours. Epidemiol Prev. 2013;37(4–5 Suppl 1):1–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zong X., Pole J.D., Grundy P.E., Mahmud S.M., Parker L., Hung R.J. Second malignant neoplasms after childhood non-central nervous system embryonal tumours in North America: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;84:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daly LE, Bourke GJ, Interpretation and uses of medical statistics, 5th ed. Online ISBN:9780470696750. DOI:10.1002/9780470696750. Copyright © 2000 Blackwell Science Ltd.

- 21.Marubini E., Valsecchi M. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. Analysing survival data from clinical trials and observational studies. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosmer D., Lemeshow S., May S. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2008. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time-to-event data. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin P.C., Lee D.S., Fine J.P. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohl M., Plischke M., Leffondré K., Heinze G. PSHREG: a sas macro for proportional and nonproportional subdistribution hazards regression. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2015;118:218–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin G., So Y., Johnston G. Proceedings of the SAS Global Forum, 2012. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2012. Analyzing survival data with competing risks using SAS software. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allison P. 2nd ed. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2010. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vittinghoff E., McCulloch C.E. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–718. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute Inc . SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2012. SAS/STAT® 12.1 user's guide. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidler M.M., Reulen R.C., Winter D.L. Risk of subsequent bone cancers among 69,460 five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer in Europe. JNCI. 2018;110(2):183–194. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teepen J.C., van Leeuwen F.E., Tissing W.J. Long-term risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms after treatment of childhood cancer in the DCOG LATER study cohort: role of chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2288–2298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayek S., Dichtiar R., Shohat T., Silverman B., Ifrah A., Boker L.K. Risk of second primary neoplasm and mortality in childhood cancer survivors based on a national registry database. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;57:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jenkinson H.C., Hawkins M.M., Stiller C.A., Winter D.L., Marsden H.B., Stevens M.C.G. Long-term population-based risks of second malignant neoplasms after childhood cancer in Britain. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1905–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scholz-Kreisel P., Kaatsch P., Spix C. Second malignancies following childhood cancer treatment in Germany from 1980 to 2014. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115:385–392. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ju H.Y., Moon E.K., Lim J. Second malignant neoplasms after childhood cancer: a nationwide population-based study in Korea. PLoS One. 2018;13(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen J.H., Möller T., Anderson H. Lifelong cancer incidence in 47 697 patients treated for childhood cancer in the Nordic countries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:806–813. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J.S., DuBois S.G., Coccia P.F., Archie Bleyer A., Olin R.L., Goldsby R.E. Increased risk of second malignant neoplasms in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:116–123. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]