Abstract

The Periprosthetic fracture of the proximal femur is usually treated by internal fixation of the fracture or revision of the femoral stem depending on the characteristics of the fracture and stability of the implant. This case report shows an early periprosthetic fracture around an uncemented straight stem which is treated conservatively with an excellent clinical radiographic result and explains the biomechanics related to this non-operative choice. A conservative treatment of periprosthetic fracture is possible but only after a careful analysis of the fracture pattern, the characteristics of the prosthetic stem and the time elapsed from implanting the prosthesis to the fracture.

Keywords: Periprosthetic hip fracture, Conservative treatment, Biomechanical considerations

1. Introduction

Periprosthetic fracture of the proximal femur is one of the most dangerous complications after hip replacement. This complication is particularly serious because the treatment has a high mortality rate, is expensive and is associated with low results due to an often-incomplete functional recovery [1]. The most common periprosthetic femoral fractures (PFFs) occur around the stem or slightly below (Vancouver Type B). To date, PFFs Vancouver Type B has been treated by internal fixation of the fracture and/or revision of the femoral stem depending on the stability of fracture site and stem itself [[2], [3], [4]]. However, it has been recently reported that certain patients with periprosthetic fractures around a stable implant could be treated conservatively [[4], [5], [6]]. In this case report we present an early periprosthetic fracture around an uncemented straight stem which was treated conservatively and explains the biomechanics related to this non-operative choice.

1.1. Case report

A 64-year-old male underwent a total hip arthroplasty, requiring implantation of a Corail stem and Pinnacle cup (Raynham, MA, USA) through lateral approach (Bauer's approach) for right coxarthrosis. The Intraoperative radiographic control was adequate (Fig. 1) and the immediate postoperative period proceeded with no complications. We gave indication for immediate weightbearing and an active and passive physio-kinesitherapy protocol that the patient performed at a dedicated rehabilitation center. After thirty post-operative days, X-ray and CT showed subsidence of the stem in varus and somewhat distally leading to a stable-like fracture of lateral cortex (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2ba and b; Fig. 3a, Fig. 3b, Fig. 3c, Fig. 3da–d). The patient did not remember any efficient trauma to the hip and was clinically asymptomatic with articular mobilization and free full weightbearing. After discussing the possible treatment options with the patient, we decided to treat it conservatively. Weightbearing was not allowed and the patient started a passive physio-kinesitherapy protocol for 8 weeks followed by progressive weightbearing with an active physio-kinesitherapy protocol. We followed-up the patient with radiographic and clinical encounters at 60, 90 and 180 days from the fracture and then yearly. At 74 months the fracture was consolidated, and the stem was stable (Fig. 4a, Fig. 4ba and b). The patient remained completely asymptomatic and his Harris Hip Score was 100 (Fig. 5a, Fig. 5ba and b).

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative x-ray control of total hip arthroplasty.

Fig. 2a.

At one month anteroposterior hip x-ray with periprosthetic fracture of the proximal femur.

Fig. 2b.

At one month lateral hip x-ray with periprosthetic fracture of the proximal femur.

Fig. 3a.

CT scan with three-dimensional reconstruction of periprosthetic proximal femur fracture.

Fig. 3b.

CT scan with three-dimensional reconstruction of periprosthetic proximal femur fracture.

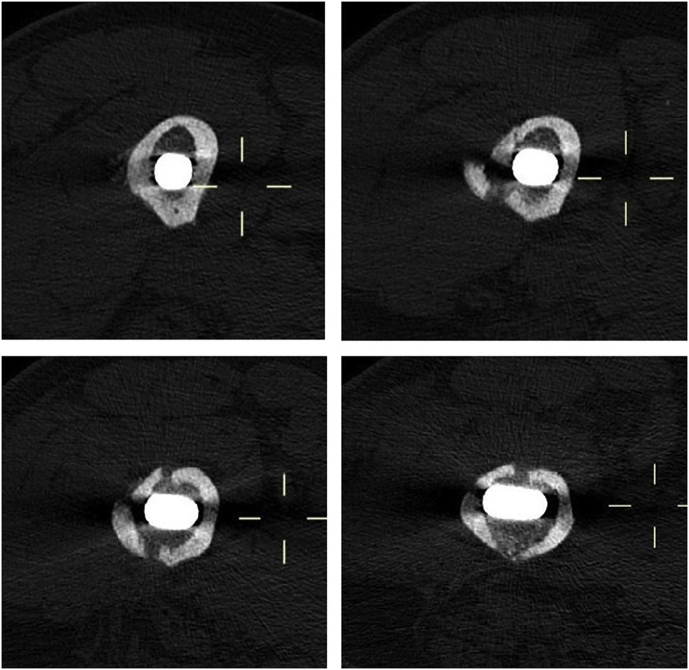

Fig. 3c.

CT scan axial levels with two-dimensional reconstruction of periprosthetic proximal femur fracture.

Fig. 3d.

CT scan coronal with two-dimensional reconstruction of periprosthetic proximal femur fracture.

Fig. 4a.

At 74 months anteroposterior hip x-ray with consolidation of the fracture and stability of the prosthetic stem.

Fig. 4b.

At 74 months lateral hip x-ray with consolidation of the fracture and stability of the prosthetic stem.

Fig. 5a.

Clinical control at 74 months from the fracture.

Fig. 5b.

Clinical control at 74 months from the fracture.

2. Discussion

Since 1995, the Vancouver system has been widely used for the classification of periprosthetic femoral fractures [2]. The Vancouver system is widely accepted because it determines fracture classification and indication for treatment (Table 1). A limit of this classification system is the lack of instrumentation for evaluating the stability of the stem in Vancouver B fractures with good bone stock. The stability of the stem is the key factor for choosing the appropriate treatment. In our case report the treatment was decided upon only after a careful analysis of the fracture's morphology, type of stem and time between the total hip arthroplasty was performed and the fracture. The fracture's morphology is appropriately described with the Johansson classification [7], where fracture and apex of the stem are correlated (Fig. 6). The type of prosthetic stem depends on how it is anchored to the femoral bone canal: cemented or uncemented, uncemented with high fit and fill at the metaphysis of the femur (anatomic stem) or high fit and fill at the diaphysis of the femur (straight stem). The time elapsed from the prosthetic implant to the trauma allows us to discriminate the stem stability type: primary (with immediate mechanical stability due to insertion of the prosthetic stem into femoral bone canal) or secondary stability (biological stability given by ingrowing bone tissue around the femoral stem). In this case report the prosthetic stem is straight uncemented with diaphyseal anchorage.

Table 1.

The Vancouver classification system.

| Type | Subtype | Fracture description | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | Fracture in trochanteric region | ||

| AG | Fractures of the greater trochanter | Conservative or cable wires | |

| AL | Fractures of the lesser trochanter | Conservative or cable wires | |

| Type B | Fracture around stem or just below it | ||

| B1 | Well-fixed stem | ORIF | |

| B2 | Loose stem with good proximal bone stock | Revision THR | |

| B3 | Loose stem with poor-quality bone stock | Revision THR | |

| Type C | Fracture occurring well below the tip of the stem | ORIF | |

ORIF: open reduction and internal fixation; THR: total hip replacement.

Fig. 6.

Johansson Classification of periprosthetic fractures of the femur.

The CORAIL prosthetic stem guarantees excellent primary mechanical stability, thanks to the geometric design of the implant, and an excellent secondary biological integration, thanks to the complete porous coating in hydroxyapatite. The surgical technique allows to save bone and to achieve the optimal filling of the femoral canal, avoiding excessive contact between the implant and the cortical bone. The fracture was a meta-diaphyseal spiroid type of fracture that did not exceed the apex of the stem (Johansson Type 1).

In the absence of an efficient traumatic event, the achievement of excessive/extreme contact between implant and femoral cortical bone (Fig. 1) may have contributed to the occurrence of fracture in the immediate postoperative period. The fracture was diagnosed shortly after the arthroplasty and the absence of weightbearing pain in the post-operative period suggested a primary stability of the stem.

Analyzing the presented case, it might be that the proximal stability of the stem was inadequate due to the operative technique. Distal osseous-integration of the stem was also inadequate at the time (only 30 days post-op). The stem subsided distally and into Varus. This seemed to be a Vancouver type B2 which combines an unstable stem and a stable lateral cortex fracture. As the stem subsided, distally and into varus of 2.38° (Fig. 7), it engaged the distal diaphysis for 3 cm (Fig. 3d) near to the fracture area, so that the HA coating facilitated fracture healing over time.

Fig. 7.

At 74 months panoramic lower limb x-ray with cementless hip stem implanted in 2.38° of varus. Varus alignment measurement technique, in line with Kahlily and others [8]. Arrow indicates angle in degrees.

A tight press fit stem, that has been implanted with less than 5 cm of contact with the femoral canal, increases the risk of gradual breaching of the medial cortex with a complete Vancouver type B2 or a type C in the future. Moreover, loose stem femoral remodeling often results in varus and retroversion as well as hip instability overtime. In our case the clinical visit and radiographic control at 6 years (Fig. 4a, Fig. 4b, Fig. 5a, Fig. 5ba, b) has avoided these catastrophic events, but however it will be necessary to continue to follow-up the patient over time. In the current literature, the conservative treatment is considered for periprosthetic fractures with stable stem (Vancouver A and B1) [5,6]. In our opinion, it is understandable to be skeptical to conservative treatment of early periprosthetic meta-diaphyseal spiroid fractures with a cementless anatomical stem (Fig. 8). On the other hand the conservative treatment could be a viable option in the presence of a straight uncemented stem (Fig. 9) and a fracture that does not exceed the apex.

Fig. 8.

Anatomic prosthetic stem with metaphyseal fit and fill.

Fig. 9.

Straight prosthetic stem with diaphyseal fit and fill.

Therefore, the conservative treatment of periprosthetic fracture is possible but only in selected cases after a careful analysis of the fracture pattern (Fig. 6), the characteristics of the prosthetic stem (Fig. 8, Fig. 9) and the time elapsed from implanting the prosthesis to the fracture. Patient compliance is mandatory for successful outcome.

Contributor Information

Mauro Spina, Email: spina.mauro@gmail.com.

Andrea Scalvi, Email: andrea.scalvi@gmail.com.

Andrea Vacchiano, Email: andrea.vacchiano@hotmail.it.

Andrea Sandri, Email: a.sandri67@gmail.com.

Massimo Balsano, Email: massimo.balsano@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Sidler-Maier C.C., Waddell J.P. Incidence and predisposing factors of periprosthetic proximal femoral fractures: a literature review. Int. Orthop. 2015;39(9):1673–1682. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2721-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan C.P., Masri B.A. Fractures of the femur after hip replacement. Instr. Course Lect. 1995;44:293–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasen A.T., Haddad F.S. Periprosthetic fractures: bespoke solutions. Bone Joint Lett. J. 2014;96-B(11 Suppl A):48–55. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.34300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masri B.A., Meek R.M., Duncan C.P. Periprosthetic fractures evaluation and treatment. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2004;420:80–95. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200403000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Wal B.C., Vischjager M., Grimm B. Periprosthetic fractures around cementless hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stems. Int. Orthop. 2005;29(4):235–240. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0657-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Learmonth I.D. The management of periprosthetic fractures around the femoral stem. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 2004;86(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson J.E., McBroom R., Barrington T.W. Fracture of the ipsilateral femur in patients wih total hip replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1981;63(9):1435–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khalily C., Lester D.K. Results of a tapered cementless femoral stem implanted in varus. J. Arthroplast. 2002;17:463–466. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.32171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]