Abstract

Serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and D-dimer have been associated with multiple adverse outcomes in HIV-infected (HIV+) individuals, but their association with neuropsychiatric outcomes, including HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) and depression, headaches and peripheral neuropathy have not been investigated. 399 HIV+ antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve adults in Rakai, Uganda were enrolled in a longitudinal cohort study and completed a neurological evaluation, neurocognitive assessment, and venous blood draw. Half of participants had advanced immunosuppression (CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/μL), and half had moderate immunosuppression (CD4 count 350–500 cells/ μL). All-cause mortality was determined by verbal autopsy within two years. HAND was determined using Frascati criteria, and depression was defined by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression (CESD) scale. Neuropathy was defined as the presence of ≥1 neuropathy symptom and ≥1 neuropathy sign. Headaches were identified by self-report. Serum D-dimer levels were determined using ELISA and IL-6 levels using singleplex assays. Participants were 53% male, mean age 35 + 8 years, and mean education 5 + 3 years. Participants with advanced immunosuppression had significantly higher levels of IL-6 (p<0.001) and a trend toward higher D-dimer levels (p=0.06). IL-6 was higher among participants with HAND (p=0.01), with depression (p=0.03) and among those who died within two years (p=0.001) but not those with neuropathy or headaches. D-dimer did not vary significantly by any outcome. Systemic inflammation as measured by serum IL-6 is associated with an increased risk of advanced immunosuppression, all-cause mortality, HAND and depression but not neuropathy or headaches among ART-naïve HIV+ adults in rural Uganda.

Keywords: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, HIV, interleukin-6, Uganda, depression, all-cause mortality

The importance of chronic inflammation in the development of both AIDS-related and non-AIDS complications of HIV infection is increasingly recognized.(Grund, Baker et al. 2016, So-Armah, Tate et al. 2016) For example, interleukin-6 (IL-6) is an excellent general biomarker of inflammation and has been correlated with poor physical function in an HIV+ cohort(Erlandson, Allshouse et al. 2013) and risk of frailty and mortality in HIV+ injection drug users and men who have sex with men.(Margolick, Martinez-Maza et al. 2013, Piggott, Varadhan et al. 2015) D-dimer is an acute phase reactant and a general marker of activation of the coagulation cascade. Elevated IL-6 and D-dimer levels have been linked to all-cause mortality in HIV+ populations, including in Botswana and South Africa (Kuller, Tracy et al. 2008, Ledwaba, Tavel et al. 2012, McDonald, Moyo et al. 2013, Grund, Baker et al. 2016, So-Armah, Tate et al. 2016), as well as to non-AIDS events such as bacterial pneumonia, microvascular cardiovascular disease, and hepatitis flares (Andrade, Hullsiek et al. 2013, Bjerk, Baker et al. 2013, Sinha, Ma et al. 2016).

Given the broad range of adverse outcomes and health conditions previously associated with chronic inflammation, we hypothesized that elevated levels of IL-6 and D-dimer would be related to HIV-related outcomes (e.g. CD4 count), all-cause mortality, peripheral neuropathy, headaches, and neuropsychiatric conditions including HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) and depression, among a cohort of antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naïve HIV+ adults in rural Rakai, Uganda.

METHODS

Study Participants

Study participants were from Rakai HIV clinics and the Rakai Community Cohort Study, an open, community-based cohort of adults residing in 40 communities in Rakai District which are representative of rural Uganda. Participants were ART-naïve HIV+ adults ≥ 20 years old. Two hundred participants with advanced immunosuppression (CD4 ≤ 200 cells/μL) and 199 participants with moderate immunosuppression (CD4 350–500 cells/μL) were enrolled and offered HIV care and/or ART free of charge immediately after enrollment per Uganda Ministry of Health ART initiation criteria in place at the time of the study. Exclusion criteria included severe systemic illness, inability to provide informed consent, and physical disability precluding travel to the Rakai Health Sciences Program clinic.

Study Procedures

Participants were enrolled in this longitudinal observational cohort study between July 2013 and July 2015. Each participant completed a sociodemographic and behavioral interview, depression screen (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)(Weissman, Sholomskas et al. 1977)), functional status assessments (Instrumental Activities of Daily Living(Lawton and Brody 1969), Bolton Functional Status Score(Bolton, Wilk et al. 2004), Patient Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory (PAOFI)(Chelune, Heaton et al. 1986) and Karnofsky Performance Status(Karnofsky and Burchenal 1949)), and a neurocognitive assessment (World Health Organization (WHO) University of California – Los Angeles (UCLA) Verbal Learning test, WHO UCLA verbal delayed recall, Timed gait, Finger tapping, Grooved pegboard, Symbol digit, Color trails parts 1 and 2, animal naming, and Digit span forward and backward) in order to establish HAND stage using Frascati criteria(Antinori, Arendt et al. 2007). A Ugandan medical officer trained by two neurologists (D.S, N.S.) performed a neuromedical evaluation. A pilot study of self-reported headaches in the past year was conducted in a subgroup of the cohort (n=130). Peripheral blood draw was performed to confirm HIV status and determine IL-6 and D-dimer levels. Participants and their family members were contacted every six months for two years to determine vital status. Those lost to follow-up (n=45) were excluded from the mortality analysis.

Laboratory Procedures

Serum D-dimer levels were determined using ELISA assays (Ray Biotech, Norcross, GA). Serum IL-6 was determined using magnetic bead human singleplex Luminex assays (Millipore, Temecula, CA). Standards and samples were run in duplicate according to manufacturers’ protocols to obtain a mean value and associated coefficient of variation (CV) for each assay. The serum samples were diluted 50,000-fold for the D-dimer assay and 4-fold for the IL-6 assay. Assay reagents and plates were obtained from well-validated commercial sources (Bio-Rad® and Raybiotech). Measurements and data analysis of the multiplex assays were performed with the Luminex-200® system in combination with Luminex manager software (Bioplex manager 5⋅0, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and the Bio-Rad plate reader for the ELISA. Samples that exhibited unexpected or unacceptable variance (i.e., evidence of bead clumping or unusual distributions of values) were re-tested. IL-6 and D-dimer samples with CV ≥ 25% were excluded from the analysis. As a result, IL-6 results were included from 322 (81%) participants and D-dimer results from 324 (81%) participants.

Standard protocol approvals and patient consents

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board, the Uganda Virus Research Institute Research and Ethics Committee, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Statistical Analysis

HAND stage was determined using normative neurocognitive data locally derived from 400 HIV-negative adults from Rakai District and applying the Frascati criteria(Antinori, Arendt et al. 2007) to classify participants as having either normal cognition, asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), minor neurocognitive disorder (MND), or HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Peripheral neuropathy was defined as ≥ 1 subjective neuropathy symptom (numbness, paresthesias or pain in the hands or feet) and ≥ 1 sign of neuropathy (distal weakness, reduced or absent ankle reflexes, abnormal distal vibratory sensation or abnormal distal pinprick sensation) on examination. Depression was defined as a score of ≥ 16 on the CES-D. Comparative analyses between groups were performed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. IL-6 and D-dimer levels were analyzed as log-transformed values and as quartiles. T-tests were used to compare mean log-transformed values, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare quartiles. Although the association of each biomarker was assessed for six different outcomes (advanced immunosuppression, HAND, depression, two-year mortality, neuropathy, and headaches), we reported results at a significance of p<0.05 given the exploratory nature of this work. However, we also applied a Bonferroni correction for each biomarker in which the significance level was adjusted to p<0.008 and reported these results as well. Analyses were performed using STATA version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We enrolled 399 ART-naïve HIV+ participants with mean age 35 (standard deviation (SD)=8) years of whom 53% were males (Table 1). Those with advanced immunosuppression were younger and more likely to be male than those with moderate immunosuppression. Average education was 5 (SD=3) years, and there were no educational differences between CD4 categories. Participants with advanced immunosuppression were more likely to be underweight, depressed, and to use tobacco and narcotics than those with moderate immunosuppression. Neuropathy was present in 19% (n=76), and HAND in 59% (n=236). Of 354 participants who were followed after two years, 17 died.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants. (CES-D=Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale)

| By CD4 Count | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ (n=399) | < 200 (n=200) | 350–500 (n=199) | p | |

| Male [n (%)] | 212 (53%) | 121 (60%) | 91 (46%) | 0.003 |

| Age (years) [mean (SD)] | 35 (8) | 34 (7) | 37 (9) | 0.001 |

| CD4 count [mean (SD)] | ---- | 95 (61) | 420 (43) | ---- |

| Education (years) [mean (SD)] | 5 (3) | 5 (4) | 5 (3) | 0.39 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) [mean (SD)] | 21.8 (3.5) | 20.6 (2.8) | 23.0 (3.7) | < 0.001 |

| Underweight [n (%)] | 51 (13%) | 44 (22%) | 7 (4%) | < 0.001 |

| Overweight/obese [n (&)] | 53 (13%) | 7 (4%) | 46 (23%) | < 0.001 |

| CES-D Score [mean (SD)] | 10 (9) | 12 (10) | 8 (9) | 0.001 |

| Depression (CES-D >= 16) [n (%)] | 96 (24%) | 61 (30%) | 35 (18%) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes [n (%)] | 0 (0%) | ---- | ---- | ----- |

| Hypertension [n (%)] | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (2%) | 0.04 |

| Tobacco use [n (%)] | 63 (16%) | 39 (20%) | 24 (12%) | 0.04 |

| Narcotics use [n (%)] | 12 (3%) | 10 (5%) | 2 (1%) | 0.02 |

| Alcohol use in past month [n (%)] | 195 (49%) | 90 (45%) | 105 (52%) | 0.13 |

| HAND [n (%)] | 236 (59%) | 131 (66%) | 105 (53%) | 0.01 |

| Peripheral neuropathy [n (%)] | 76 (19%) | 36 (18%) | 40 (20%) | 0.59 |

| Headaches [n (%)]* | 55 (42%) | 4 (40%) | 51 (42%) | 1.0 |

| Mortality [n (%)]+ | 17 (5%) | 14 (8%) | 3 (2%) | 0.005 |

Headaches were surveyed in a subgroup of 130 participants (n=10 with CD4<200 cells/μL and n=120 with CD4 350–500 cells/μL). Remaining participants were excluded from this analysis.

Vital status was ascertained in 354 participants (n=166 with CD4<200 cells/μL and n=188 with CD4 350–500 cells/μL). Participants lost to follow-up (n=45) were excluded from this analysis.

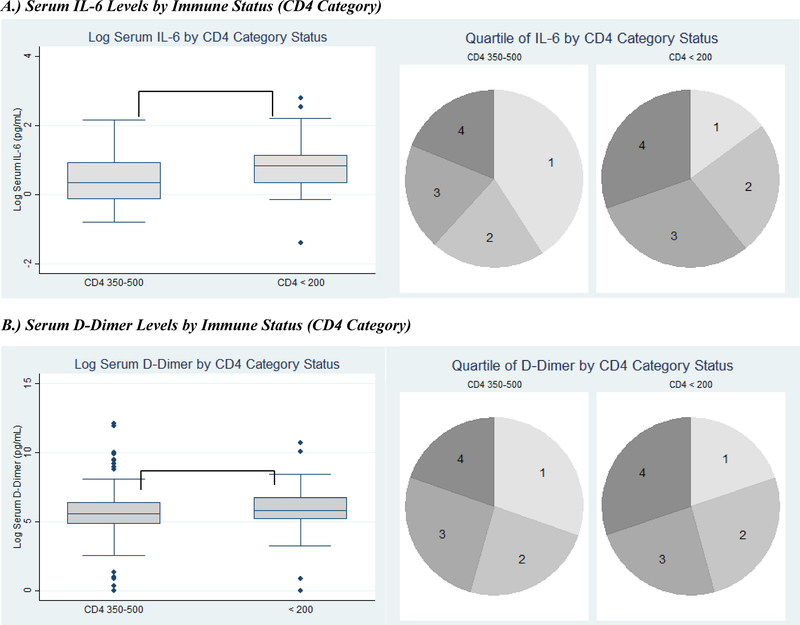

On average, participants with advanced immunosuppression were more likely to have higher quartiles of IL-6 [median (interquartile range (IQR)): 3 (2–4) vs. 2 (1–3), p<0.001] (Figure A) and D-dimer [3 (2–4) vs. 2 (1–3), p=0.02] (Figure B) than those with moderate immunosuppression. In other words, the median IL-6 quartile among participants with advanced immunosuppression was three, and 75% of participants in this group had IL-6 quartiles between two and four. In comparison, the median IL-6 quartile among participants in the moderate immunosuppression group was two with 75% of participants in this group having IL-6 levels that fell in the first to third quartile of the overall values for all participants. Mean log IL-6 was also significantly higher among those with advanced immunosuppression [mean (SD): 0.77 (0.62) log pg/mL vs. 0.42 (0.63) log pg/mL, p<0.001] (Figure A), and there was a trend toward higher mean log D-dimer [5.7 (1.8) log pg/mL vs. 5.3 (2.4) log pg/mL, p=0.06] (Figure B).

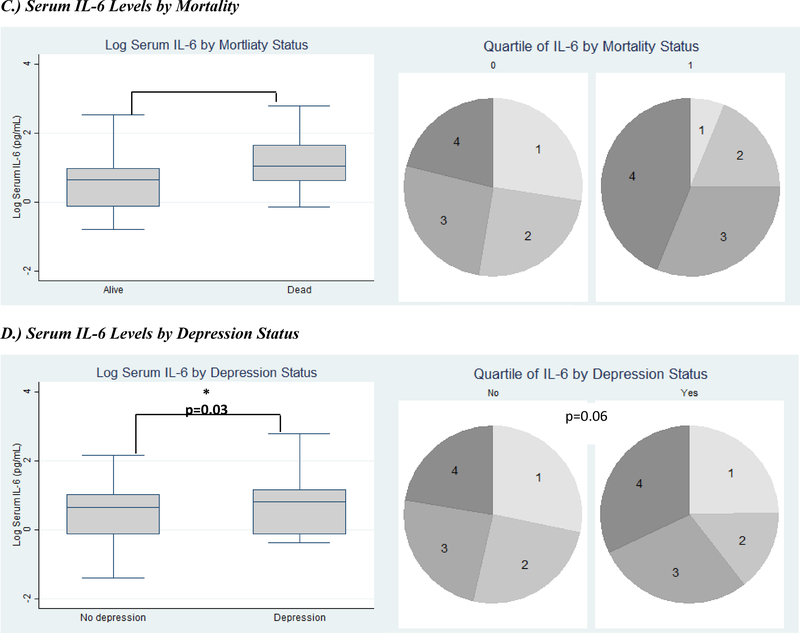

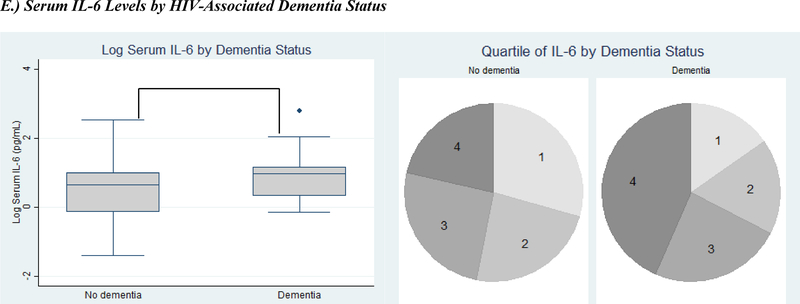

FIGURE.

Serum inflammatory markers by clinical outcomes. Inflammatory markers expressed as both log-transformed levels and quartiles. Clinical outcomes include serum IL-6 levels (A) and D-dimer levels (B) by immune status (CD4 category), (C) serum IL-6 levels by two-year mortality, (D) serum IL-6 levels by depression, and (E) serum IL-6 levels by HIV-associated dementia. (IL-6=Interleukin-6; * signifies p<0.05; ** signifies p<0.001; in each pie graph, quartile 1 is the smallest quartile, and quartile 4 is the largest quartile.)

Participants who died within a two-year follow-up period also had significantly higher levels of IL-6 at their baseline visit and were more likely to have higher quartiles of IL-6 [mean log IL-6: 1.13 (0.76) log pg/mL vs. 0.57 (0.61) log pg/mL, p<0.001; IL-6 quartiles: 3 (2–4) vs. 2 (1–3), p=0.01] than those who survived to their two-year follow-up visit (Figure C). Participants with depression had higher mean log IL-6 levels [0.74 (0.70) log pg/mL vs. 0.55 (0.62) log pg/mL, p=0.03] and were more likely to have higher quartiles of IL-6 [3 (2–4) vs. 2 (1–3), p=0.06], though the latter was not statistically significant (Figure D). There was no significant difference in D-dimer levels by all-cause mortality or depression.

Participants with HAND were significantly more likely to have higher quartiles of IL-6 and mean IL-6 levels compared to those with normal cognition. The results were most pronounced for participants with HAD compared to those without HAD [IL-6 quartile: 3 (2–4) vs. 2 (1–3), p=0.04; mean log IL-6: 1.83 (1.50) log pg/mL vs. 1.32 (1.53) log pg/mL, p=0.03] (Figure E). D-dimer levels did not vary by HAND stage. In a multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for age, sex, education, D-dimer, and advanced immunosuppression (i.e. CD4 < 200 cells/μL), odds of HAD increased by 74% [Odds Ratio (OR)=1.74, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) (1.18, 2.54), p=0.005] for every one quartile increase in IL-6 level. When depression was added to the model, odds of HAD for every one quartile increase in IL-6 level decreased [OR=1.66, 95% CI (1.12, 2.45), p=0.01] but remained statistically significant.

There was no difference in IL-6 or D-dimer levels by peripheral neuropathy or headaches (data not shown).

Of note, these results have been reported using a standard significance level of p<0.05 due to the exploratory nature of this work. However, after applying a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons and using a significance level of p<0.008, the associations between IL-6 mean and quartiles with advanced immunosuppression, mean IL-6 and mortality, and the increased odds of HAD with increasing IL-6 quartile all remained significant. However, the associations between IL-6 and depression and HAND were no longer significant and neither were any of the D-dimer analyses.

DISCUSSION

In this study of HIV+ adults in rural Uganda, higher IL-6 and D-dimer levels prior to ART initiation were associated with more advanced immunosuppression. Furthermore, higher pre-ART IL-6 levels were associated with increased two-year all-cause mortality despite nearly all participants initiating ART soon after study enrollment. Other studies have also shown that higher levels of IL-6 are associated with increased AIDS-related and non-AIDS mortality in both ART-naïve and ART-experienced virologically suppressed HIV+ cohorts.(Kuller, Tracy et al. 2008, Ledwaba, Tavel et al. 2012, McDonald, Moyo et al. 2013, Grund, Baker et al. 2016, So-Armah, Tate et al. 2016, Lee, Byakwaga et al. 2017, Masia, Padilla et al. 2017) Contrary to prior studies in which D-dimer levels were strongly associated with mortality - including a study of ART-naïve HIV+ Ugandans initiating ART (Lee, Byakwaga et al. 2017) - it was not associated with increased mortality in this cohort. However, the previously reported Ugandan study evaluated the association between D-dimer levels obtained six months after ART initiation with mortality occurring after that time point whereas this study evaluated only the association of pre-ART D-dimer levels with mortality. Thus, D-dimer levels that are persistently elevated after ART initiation may be more strongly associated with ongoing systemic inflammation and mortality than levels only elevated prior to ART initiation.

Sustained levels of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of HAND, which remains prevalent in both ART-naïve and ART-experienced HIV+ cohorts.(Saylor, Dickens et al. 2016) IL-6 has been implicated as a driver of ongoing CNS inflammation in virologically suppressed ART-treated patients regardless of cognitive status and has been shown to activate inflammatory cytokine expression in astrocytes.(Kamat, Lyons et al. 2012, Nitkiewicz, Borjabad et al. 2017) Most studies of the impact of IL-6 on HAND have focused on IL-6 levels in cerebrospinal fluid. However, our study found that serum IL-6 levels were strongly correlated with risk of all stages of HAND and especially HAD. These findings were similar to those from ART-treated HIV+ men from the United States.(Lake, Vo et al. 2015) Similar to our results, a recent study in ART-treated HIV+ participants in the California HIV/AIDS Research Program found no association between D-dimer and neurocognitive status.(Montoya, Iudicello et al. 2017)

IL-6 was also associated with depression symptomatology in this cohort. Only a few small studies investigating the link between IL-6 and depression have been previously reported, but all found a positive association.(Warriner, Rourke et al. 2010, Fumaz, Gonzalez-Garcia et al. 2012, Norcini Pala, Steca et al. 2016) However, to our knowledge, this is the largest prospective study to date and the only study from sub-Saharan Africa to investigate this relationship. Of note, given the well-established association between HAND and depression, multivariate models including both conditions were completed. While the magnitude of the association was reduced somewhat, the relationship between IL-6 and HAD persisted even after controlling for depression suggesting that IL-6 may have independent effects on the development of both conditions.

We also hypothesized that chronic systemic inflammation would drive other neurologic syndromes in this cohort, but neither IL-6 nor D-dimer levels correlated with either peripheral neuropathy or headaches. To our knowledge, the association between IL-6 and D-dimer levels and headaches has not been previously investigated in an HIV+ cohort. One prior study of HIV+ adults initiating ART found an increase in inflammatory cytokine levels among those who developed neuropathic pain symptoms compared to those who did not, but this study did not include assessment of either IL-6 or D-dimer.(Van der Watt, Wilkinson et al. 2014)

The major limitations of this study is that it does not evaluate changes in IL-6 or D-dimer after ART initiation. In addition, we investigated only two biomarkers of inflammation and were not able to investigate the correlation between serum and CSF inflammatory markers. However, especially in this clinical setting, there is utility in being able to identify biomarkers on more easily obtained samples (i.e. serum). Strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size and investigating these markers in a rural Sub-Saharan African cohort.

In summary, our study found serum IL-6 is strongly associated with advanced immunosuppression, two-year all-cause mortality, depression and HAND in this cohort of HIV+ adults in rural Uganda. This suggests that obtaining IL-6 levels - where feasible - upon presentation to HIV care may help identify patients at highest risk of early mortality and poor neuropsychiatric outcomes. These patients could then be targeted for increased neuropsychiatric screening and intensive interventions to improve ART enrollment and adherence such as providing additional medical follow-up visits or increased social support and medication monitoring. It also highlights the ongoing need to identify HIV treatments which control chronic systemic inflammation and not just viral replication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants and staff at the Rakai Health Sciences Program for the time and effort they dedicated to this study.

Sources of Support: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (MH099733, MH075673, MH080661–08, L30NS088658, NS065729–05S2, P30AI094189–01A1) with additional funding from the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Deanna Saylor reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Anupama Kumar reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Gertrude Nakigozi reports no conflicts of interest.

Mr. Aggrey Anok reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. James Batte reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Alice Kisakye reports not conflicts of interest.

Mr. Richard Mayanja reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Noeline Nakasujja reports no conflicts of interst.

Dr. Kevin R. Robertson reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Ronald H. Gray reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Maria J. Wawer reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Carlos A. Pardo reports no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Ned Sacktor reports no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Andrade BB, Hullsiek KH, Boulware DR, Rupert A, French MA, Ruxrungtham K, Montes ML, Price H, Barreiro P, Audsley J, Sher A, Lewin SR and Sereti I (2013). “Biomarkers of inflammation and coagulation are associated with mortality and hepatitis flares in persons coinfected with HIV and hepatitis viruses.” J Infect Dis 207(9): 1379–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V and Wojna VE (2007). “Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.” Neurology 69(18): 1789–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerk SM, Baker JV, Emery S, Neuhaus J, Angus B, Gordin FM, Pett SL, Stephan C and Kunisaki KM (2013). “Biomarkers and bacterial pneumonia risk in patients with treated HIV infection: a case-control study.” PLoS One 8(2): e56249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Wilk CM and Ndogoni L (2004). “Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria.” Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39(6): 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelune GJ, Heaton RK and Lehman RAW (1986). Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients’ complaints of disability Advances in clinical neuropsychology. Tarter RE and Goldstein G. New York, Plenum Press; 3: 95–126. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, Lee EJ, Rufner KM, Palmer BE, Wilson CC, MaWhinney S, Kohrt WM and Campbell TB (2013). “Association of functional impairment with inflammation and immune activation in HIV type 1-infected adults receiving effective antiretroviral therapy.” J Infect Dis 208(2): 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumaz CR, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Borras X, Munoz-Moreno JA, Perez-Alvarez N, Mothe B, Brander C, Ferrer MJ, Puig J, Llano A, Fernandez-Castro J and Clotet B (2012). “Psychological stress is associated with high levels of IL-6 in HIV-1 infected individuals on effective combined antiretroviral treatment.” Brain Behav Immun 26(4): 568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grund B, Baker JV, Deeks SG, Wolfson J, Wentworth D, Cozzi-Lepri A, Cohen CJ, Phillips A, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD and I. S. E. S. S. Group (2016). “Relevance of Interleukin-6 and D-Dimer for Serious Non-AIDS Morbidity and Death among HIV-Positive Adults on Suppressive Antiretroviral Therapy.” PLoS One 11(5): e0155100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat A, Lyons JL, Misra V, Uno H, Morgello S, Singer EJ and Gabuzda D (2012). “Monocyte activation markers in cerebrospinal fluid associated with impaired neurocognitive testing in advanced HIV infection.” Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 60(3): 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky DA and Burchenal JH (1949). The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer Evaluatoin of Chemotherapeutic Agents. Macelod CM. New York, Columbia University Press: 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kuller LH, Tracy R, Belloso W, De Wit S, Drummond F, Lane HC, Ledergerber B, Lundgren J, Neuhaus J, Nixon D, Paton NI and Neaton JD (2008). “Inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers and mortality in patients with HIV infection.” PLoS Med 5(10): e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JE, Vo QT, Jacobson LP, Sacktor N, Miller EN, Post WS, Becker JT, Palella FJ Jr., Ragin A, Martin E, Munro CA and Brown TT (2015). “Adiponectin and interleukin-6, but not adipose tissue, are associated with worse neurocognitive function in HIV-infected men.” Antivir Ther 20(2): 235–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP and Brody EM (1969). “Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living.” Gerontologist 9: 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledwaba L, Tavel JA, Khabo P, Maja P, Qin J, Sangweni P, Liu X, Follmann D, Metcalf JA, Orsega S, Baseler B, Neaton JD and Lane HC (2012). “Pre-ART levels of inflammation and coagulation markers are strong predictors of death in a South African cohort with advanced HIV disease.” PLoS One 7(3): e24243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Byakwaga H, Boum Y, Burdo TH, Williams KC, Lederman MM, Huang Y, Tracy RP, Cao H, Haberer JE, Kembabazi A, Bangsberg DR, Martin JN and Hunt PW (2017). “Immunologic Pathways that Predict Mortality in HIV-Infected Ugandans Initiating ART.” J Infect Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolick JB, Martinez-Maza O, Jacobson LP, Lopez J, Li X and Phair JP (2013). Frailty and circulating markers of inflammation in HIV-infected and -uninfected men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Masia M, Padilla S, Fernandez M, Barber X, Moreno S, Iribarren JA, Portilla J, Pena A, Vidal F, Gutierrez F and CoRis (2017). “Contribution of Oxidative Stress to Non-AIDS Events in HIV-Infected Patients.” J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 75(2): e36–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B, Moyo S, Gabaitiri L, Gaseitsiwe S, Bussmann H, Koethe JR, Musonda R, Makhema J, Novitsky V, Marlink RG, Wester CW and Essex M (2013). “Persistently elevated serum interleukin-6 predicts mortality among adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in Botswana: results from a clinical trial.” AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 29(7): 993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JL, Iudicello J, Oppenheim HA, Fazeli PL, Potter M, Ma Q, Mills PJ, Ellis RJ, Grant I, Letendre SL, Moore DJ and H. I. V. N. R. P. Group (2017). “Coagulation imbalance and neurocognitive functioning in older HIV-positive adults on suppressive antiretroviral therapy.” AIDS 31(6): 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitkiewicz J, Borjabad A, Morgello S, Murray J, Chao W, Emdad L, Fisher PB, Potash MJ and Volsky DJ (2017). “HIV induces expression of complement component C3 in astrocytes by NF-kappaB-dependent activation of interleukin-6 synthesis.” J Neuroinflammation 14(1): 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcini Pala A, Steca P, Bagrodia R, Helpman L, Colangeli V, Viale P and Wainberg ML (2016). “Subtypes of depressive symptoms and inflammatory biomarkers: An exploratory study on a sample of HIV-positive patients.” Brain Behav Immun 56: 105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggott DA, Varadhan R, Mehta SH, Brown TT, Li H, Walston JD, Leng SX and Kirk GD (2015). “Frailty, Inflammation, and Mortality Among Persons Aging With HIV Infection and Injection Drug Use.” J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70(12): 1542–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor D, Dickens AM, Sacktor N, Haughey N, Slusher B, Pletnikov M, Mankowski JL, Brown A, Volsky DJ and McArthur JC (2016). “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder--pathogenesis and prospects for treatment.” Nat Rev Neurol 12(4): 234–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Ma Y, Scherzer R, Hur S, Li D, Ganz P, Deeks SG and Hsue PY (2016). “Role of T-Cell Dysfunction, Inflammation, and Coagulation in Microvascular Disease in HIV.” J Am Heart Assoc 5(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So-Armah KA, Tate JP, Chang CH, Butt AA, Gerschenson M, Gibert CL, Leaf D, Rimland D, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Budoff MJ, Samet JH, Kuller LH, Deeks SG, Crothers K, Tracy RP, Crane HM, Sajadi MM, Tindle HA, Justice AC, Freiberg MS and V. P. Team (2016). “Do Biomarkers of Inflammation, Monocyte Activation, and Altered Coagulation Explain Excess Mortality Between HIV Infected and Uninfected People?” J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 72(2): 206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Watt JJ, Wilkinson KA, Wilkinson RJ and Heckmann JM (2014). “Plasma cytokine profiles in HIV-1 infected patients developing neuropathic symptoms shortly after commencing antiretroviral therapy: a case-control study.” BMC Infect Dis 14: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warriner EM, Rourke SB, Rourke BP, Rubenstein S, Millikin C, Buchanan L, Connelly P, Hyrcza M, Ostrowski M, Der S and Gough K (2010). “Immune activation and neuropsychiatric symptoms in HIV infection.” J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 22(3): 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Sholomskas D, Pottenger M, Prusoff BA and Locke BZ (1977). “Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: a validation study.” Am J Epidemiol 106(3): 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]