Abstract

Understanding how to design small molecules that target coding and non-coding RNA has the potential to exponentially increase the number of therapeutically-relevant druggable targets, which are currently mostly proteins. However, there is limited information on the principles at the basis of RNA recognition. In this chapter, we describe a pattern-based technique that can be used for the simultaneous elucidation of RNA motifs and small molecule features for RNA selective recognition, termed Pattern Recognition of RNA by Small Molecules (PRRSM). We provide protocols for the computational design and synthetic preparation of an RNA training set as well as how to perform the assay in plate reader format. Furthermore, we provide details on how to perform and interpret the statistical analysis and indicate possible future extensions of the technique. By combining insights into characteristics of the small molecules and of the RNA that leads to differentiation, PRRSM promises to accelerate the elucidation of the determinants at the basis of RNA recognition.

1. Introduction

1.1. RNA as a drug target

RNA molecules are key players in a myriad of biological processes ranging from transfer of genetic information to regulation of gene expression (Cech & Steitz, 2014; Morris & Mattick, 2014). More recently, non-protein coding (nc) RNA transcripts, which constitute ~70% of transcribed RNA in eukaryotic cells, have emerged as interesting targets for disease diagnosis and therapy as dis-regulation of these RNAs has been implicated in various types of cancers and neurodegenerative diseases (Cech & Steitz, 2014; Connelly, Moon, & Schneekloth, 2016; Jarroux, Morillon, & Pinskaya, 2017). The identification of RNA motifs correlated to these disease states has the potential to exponentially increase the number of druggable targets in cells (Warner, Hajdin, & Weeks, 2018). Small and large RNA transcripts alike exert their function in both normal and disease states when folded in active conformations that are stabilized by smaller structural motifs, which represent plausible therapeutic targets.

Targeting these structures with small molecules is particularly appealing for the tunability of the physicochemical properties and increased cellular uptake relative to oligonucleotides used in antisense strategies (Donlic & Hargrove, 2018; Sztuba-Solinska, Chavez-Calvillo, & Cline, 2019; Warner et al., 2018). However, the only FDA-approved small molecule drugs targeting RNA act on the bacterial ribosome. This is in part due to a dearth of information from both the small molecule design perspective as well as principles regarding RNA recognition; it is challenging to design small molecules that specifically target RNA when there is a lack of structural information for therapeutically plausible RNA targets.

1.2. Techniques for RNA structural determination and small molecule interactions

Current structure determination techniques include chemical and enzymatic probing (Ziehler & Engelke, 2000), which combines computational and experimental methods such as selective 2′-hydroxyl acetylation by primer extension (SHAPE) (Wilkinson, Merino, & Weeks, 2006), dimethylsulfate (DMS) (Tijerina, Mohr, & Russell, 2007), and light activated structural examination of RNA (LASER) (Ackermann & Famulok, 2013; Feng et al., 2018; Tius & Kawakami, 1995) for 2D structures; and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Salmon, Yang, & Al-Hashimi, 2014), X-ray diffraction (Cate & Doudna, 2000), small-angle X-ray scattering (Chen & Pollack, 2016) and cryo electron microscopy (Razi, Ortega, & Britton, 2016) for 3D structures. Indeed, the structural information derived from these techniques has provided evidence that the topologies and the dynamics of RNA motifs are associated with their molecular recognition properties including small molecule interactions.

Comprehensive analysis of the binding signatures (i.e., equilibrium dissociation constants, thermodynamic and kinetic parameters) of small molecules interacting with a series of RNA targets can be obtained combining a variety of biophysical methods, including NMR (Patwardhan et al., 2017), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Salim & Feig, 2009), surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (Hendrix, Priestley, Joyce, & Wong, 1997), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) (Xie, Dix, & Tor, 2009), ultraviolet (UV) melting spectroscopy (McPike, Sullivan, Goodisman, & Dabrowiak, 2002), and indicator displacement assays (IDA) (Patwardhan, Cai, Newson, & Hargrove, 2019; Zhang, Umemoto, & Nakatani, 2010). Despite being extremely insightful, the combination of RNA structural determination and small molecule binding techniques can be time- and material-consuming and often limited to singular RNA structures.

In order to overcome these limitations and accelerate both the discovery of RNA druggable motifs and RNA-targeting molecular scaffolds, high-throughput techniques capable of simultaneously screening the features of small molecules and RNA structures have started to emerge (Velagapudi & Disney, 2014).

In this method, we describe the experimental details of pattern recognition of RNA by small molecules (PRRSM), a succinct method that allows simultaneous elucidation of the structural features of a variety of RNA motifs and the governing principles for their recognition by a set of small molecules.

1.3. Pattern recognition background

Pattern recognition techniques are formidable methods for the analysis of a variety of interactions in complex chemical mixtures (Fig. 1) (Folmer-Andersen, Kitamura, & Anslyn, 2006; Kitamura, Shabbir, & Anslyn, 2009; Umali & Anslyn, 2010). Similar to the olfactory and gustatory systems, pattern-based sensing can differentiate among a large variety of similar “stimuli” such as nitrated explosives (Hughes, Glenn, Patrick, Ellington, & Anslyn, 2008), tannins in wine (Umali et al., 2011), ions in water (Palacios, Nishiyabu, Marquez, & Anzenbacher, 2007) and normal, cancerous and metastatic cells (Bajaj et al., 2009). One of the main advantages of this approach is that receptor-based sensing does not require strong and selective binding for a single analyte, but a moderate differential binding for a series of analytes, dramatically reducing the amount of structural information and synthetic effort required for studying receptor-analyte interactions. Sensor systems such as displacement of indicators, colorimetric indicators, or fluorescent labels are required to measure the interactions between analytes and receptors (Umali & Anslyn, 2010). Because of the multitude of data generated from the simultaneous analysis of a variety of analytes and receptors, pattern recognition techniques rely on multivariate statistical analysis such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) that allows for patterns to become observable by reducing the data dimensionality. Advantageously, the unbiased classification of PCA can also be used for understanding the principles of the analytes-receptor interaction by examining the loading factors of each principal component. On the other hand, LDA is a supervised statistical analysis that achieves maximum differentiation between pre-defined groups and provides the classification power of the assay.

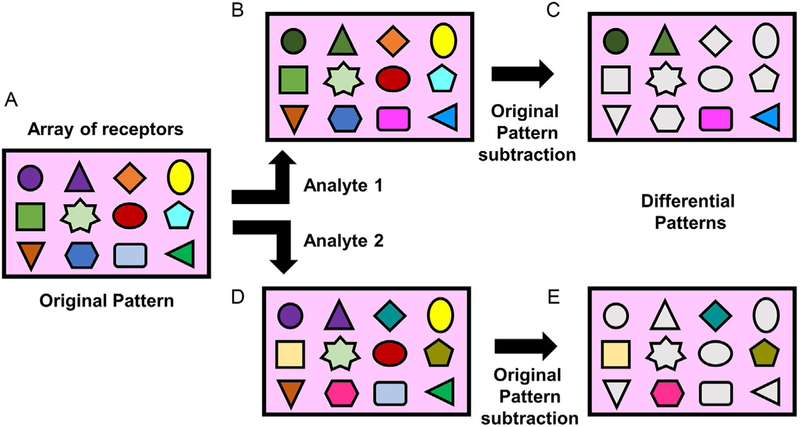

Fig. 1.

Example of pattern-based assay. Analytes of the original array of receptors (A) are examined for differential interactions (B and D) to produce a differential pattern (C and E) after subtraction of the background. These patterns can be used to classify unknown analytes.

1.4. PRRSM overview

PRRSM is a pattern-based method that differentiates RNA motifs (analytes) by exploiting a series of small molecule receptors (Eubanks, Forte, Kapral, & Hargrove, 2017; Eubanks & Hargrove, 2017, 2019) (Fig. 2). PRRSM differentiation is achieved by measuring the variation of fluorescence intensity induced by the interaction between fluorescently labeled RNA motifs and a small molecule library. The clustering of PRRSM can be used to derive features and properties of both small molecules and RNA motifs that underlie selective recognition. Furthermore, the differentiation of RNA structure by small molecules has the potential to identify targetable motifs in structurally unknown RNA constructs.

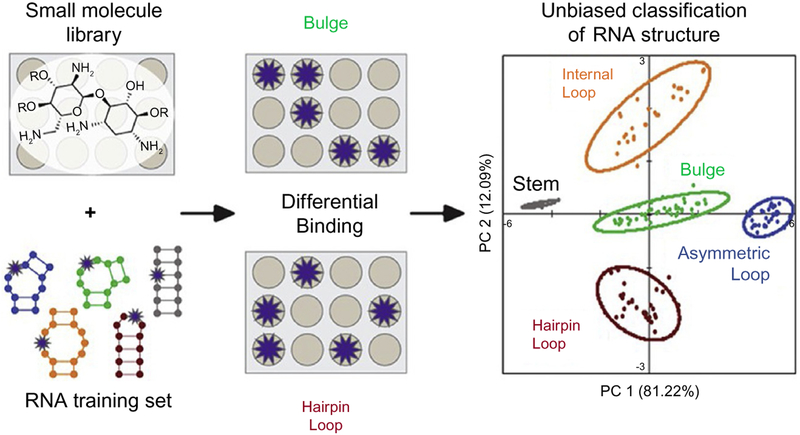

Fig. 2.

Overview of PRRSM. The differential binding of a small molecule library (receptors) is used to classify an RNA training set (16 fluorescence labeled motifs). Reprinted with permission from Eubanks, C. S., Forte, J. E., Kapral, G. J., & Hargrove, A. E. (2017). Small molecule-based pattern recognition to classify RNA structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139(1), 409–416. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society.

In this method, we describe the details of the design and experimental procedures of PRRSM. Section 2 describes how to design a training set of fluorescently labeled RNA motifs using a computational approach, the choice of the small molecule receptors and some considerations for achieving the optimal conditions for the assay. Sections 3 and 4 describe the synthetic procedures for the preparation of the fluorescent probe benzofuranyl uridine (BFU) as phosphoramidite monomer and its incorporation in RNA structures using an automated solid phase oligonucleotide synthesizer. Section 3 also describes how to synthetically modify the aminoglycoside receptors used here to increase their structural diversity. Section 5 describes how to conduct the assay in a plate reader format. Section 6 describes how to perform PCA and leave-one-out cross validation (LOOCV) and how to correctly use the data to achieve the optimal differentiation and interpretation. Section 7 briefly describes how PRRSM can complement other structural prediction techniques for determining targetable RNA motifs in unknown RNA constructs.

2. Assay design and experimental considerations

2.1. Computational sequence design of the training set

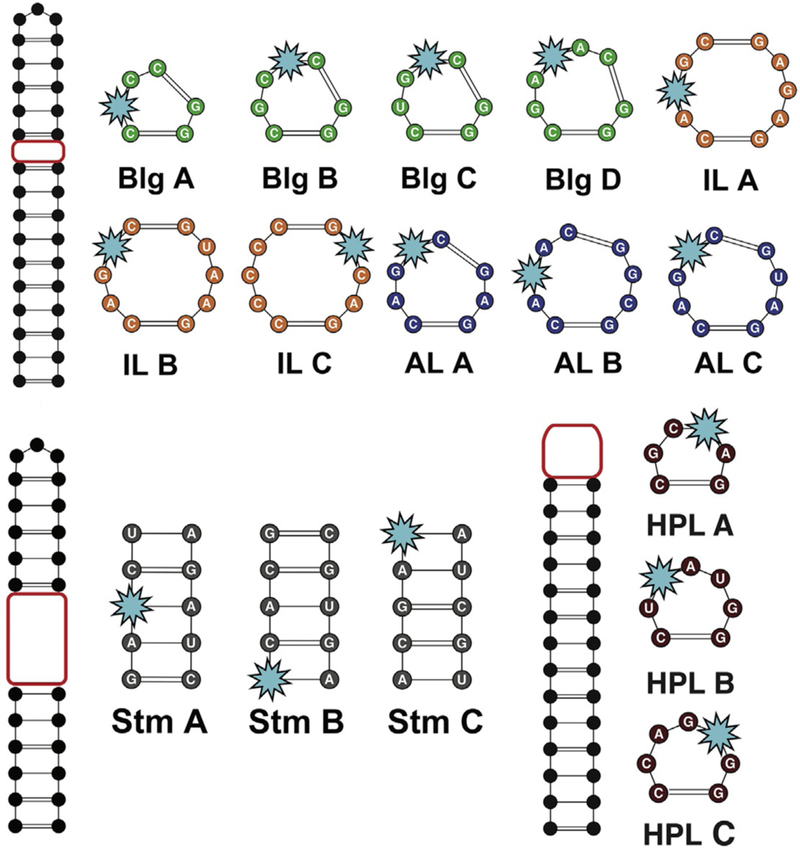

The first step of PRRSM is the design of a training set of sequences containing the RNA motifs of interest. The following considerations were obtained from our proof of concept study that focused on bulges (BLG), hairpin loops (HPL), internal loops (IL), asymmetric internal loops (AIL) and stems (STM) (Eubanks et al., 2017). Because of their intrinsically dynamic nature, RNA structures are normally characterized by multiple energetically stable conformations and, therefore, a rational design is required for minimizing the risk of multiple secondary structures present in solution that could lead to data misinterpretation. In PRRSM, the RNA cassettes flanking the variable motifs are kept constant in order to prevent a fluorescence variation due to changes in the RNA sequence or off-target small molecule binding (Fig. 3). The cassettes should contain sufficient GC content to ensure a melting temperature of at least 60°C and minimize the possibility of partial unfolding events under experimental conditions. Computationally-predicted melting temperatures obtained from web server softwares such as Mfold (Zuker, 2003) can be used for this purpose. Furthermore, at least one GC base pair should be introduced at the terminal positions of the structures of interest in order to minimize “slipped” folding. The size and sequences of the RNA motifs (variable portions) can be computationally designed to mimic naturally occurring RNA secondary structures. For example, the size of the motifs described here was chosen according to their natural abundance by using RNA Secondary Structure and Statistical Analysis database (RNA STRAND) (Andronescu, Bereg, Hoos, & Condon, 2008). The sequences can mimic naturally occurring motifs or be obtained by randomization. In all the cases, the expected folding should be computationally confirmed. Lastly, the synthetic accessibility of the structures should be considered. The current protocol for PRRSM is restricted to short oligonucleotides (~40 nts) that are near the upper limit for RNA solid phase synthesis, which is required for selective incorporation of the fluorescent label. Further restrictions might arise from the poor synthetic tractability of certain sequences on the synthesizer.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the RNA training set design. Adapted from Eubanks, C. S., & Hargrove, A. E. (2017). Sensing the impact of environment on small molecule differentiation of RNA sequences. Chemical Communications, 53(100), 13363–13366 with permission of the Royal Chemical Society.

2.2. Choice and localization of the fluorescence sensor

In PRRSM, the sensor that measures RNA-small molecule interactions is a fluorescent nucleotide inserted into selected positions of the RNA motifs. The ideal solvatochromic fluorophore for this purpose should have minimal impact on the overall RNA topologies and hydrogen bonding network, have good quantum yield, and be sensitive to environmental changes. Despite the higher steric hindrance, the uridine analog BFU was deemed superior to the more common 2-aminopurine (2-AP) because BFU does not mismatch with other nucleotides (2-AP can pair with U and C), and it has enhanced quantum yield and sensitivity to environmental changes such as solvation and base stacking (Tanpure & Srivatsan, 2011). The fluorescence sensor should be placed at the most flexible position of the RNA motif to allow the minimal perturbations induced by small molecules binding to cause the greatest fluorescence variation and minimize possible structural interference arising from the fluorophore moiety (Fig. 3). A computational approach can be used to identify this position. For example, structures can be subjected to MonteCarlo simulations using the FARFAR algorithm available in the Rosie web server to generate 1000 possible conformations (Moretti, Lyskov, Das, Meiler, & Gray, 2018). For each motif, 20 representative conformations can be clustered according to root-mean-squared deviation (RMSD) relative to the lowest energy structure to generate a structural ensemble (Cheng, Chou, & Das, 2015). The most flexible residues can be identified by visually comparing the frequency of nucleotides flipped out the stack of the helix in the structural ensembles. Alternatively, if a large number of conformations are analyzed, a pseudo-dihedral angle defined by the following four points can be calculated: (a) the center of mass of the 3′ base of the potentially flipped base in analysis; (b) center of mass of the sugar of the 3′ base; (c) the center of mass of the sugar of the base in analysis; (d) the center of mass of the base in analysis (Hart, Nyström, Öhman, & Nilsson, 2005). These values can be calculated for each base of the RNA motifs by using the cpptraj module included in the AMBER package (Roe & Cheatham, 2013). More flexible positions can be identified by plotting the frequency of distribution of this value of the nucleobases in analysis.

When choosing the substitution, priority should be given to flexible uridine residues to minimize the influence of hydrogen bonding networks and mismatched conformations.

2.3. Small molecule library choice and preparation

Small molecule aminoglycosides were identified as ideal starting receptors to develop PRRSM. First, this class of compounds has relatively high affinity for a variety of RNA constructs. The lack of selectivity for specific RNA motifs due to electrostatic interactions is expected to minimally impact pattern recognition experiments, where the only requirement is differential binding affinity, normally in the range from nanomolar to micromolar equilibrium dissociation constants (Chittapragada, Roberts, & Ham, 2009). Furthermore, aminoglycosides are commercially available, cheap, and relatively easy to functionalize in the event increased chemical diversity is required for the assay.

The same considerations can potentially be extended to new classes of small molecules with moderate binding affinity for the RNA structures of interest.

2.4. Considerations on conditions, buffer and concentrations

Despite the low volume of sample required for PRRSM, optimization of RNA and small molecule concentrations should be performed to avoid wasting precious material. RNA concentration at around 200nM should ensure the optimal signal-to-noise ratio in the fluorescence measurement for most modern plate readers. The choice of the buffer also influences the intensity of the fluorescence signal. In our hands, a phosphate buffer (25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.1mM EDTA, pH 7.3, 25°C, Buffer A) resulted in enhanced fluorescence outputs compared to buffers such as cacodylic, HEPES and Tris. However, no major differences were observed between phosphate and Tris in PRRSM structural differentiation. Variations to these conditions might increase or decrease clustering in PRRSM (Eubanks & Hargrove, 2017). For example, the assay tolerates pH ranges between 6 and 8 as minimal differences in predictive power are observed. However, more acidic conditions (pH 5) ablate the differentiation, presumably due to conformational and electrostatic perturbations of the aminoglycoside ligands. Variations of ionic strength also affect PRRSM. As expected, high sodium concentration (140mM) reduces the predictive power presumably due to the weaker affinity of aminoglycosides for RNA under these conditions. Surprisingly, both high concentration and removal of Mg2+ (10mM) do not affect motif classification but reduce the differentiation of individual sequences. Increasing the temperature to physiological conditions (37°C) slightly reduces the predictive power relative to the standard conditions, presumably due to reduced binding affinity of aminoglycosides for RNA structures. However, physiological temperature in combination with a molecular crowder (PEG-12000) known to destabilize RNA structures to mimic in vivo conditions slightly reduces motif classification but enhances individual sequence separation. Altogether, these considerations indicate that buffer and experimental conditions can be adjusted for optimal motif classification or enhanced individual sequences differentiation to provide insight into the nature of the molecular recognition.

3. Synthetic preparation of BFU and guanidinylated aminoglycoside

3.1. Equipment for organic synthesis

Rotary evaporator

Vacuum manifold (Schlenk line or similar) connected to inert gas cylinder (N2)

Microwave reactor (Biotage® Initiator+ or similar)

Ventilated fume hood

Lyophilizer

NMR spectrometer (400 or 500MHz)

HPLC (fitted with C18 column such as Phenomenex Luna 5 μm C18 100A 150×4.6mm or similar)

Mass spectrometer (Electrospray Ionization by direct infusion or coupled with a liquid chromatography apparatus)

Standard organic chemistry glassware

Water purification system (ELGA PURELAB Flex Veolia Water Technologies or similar)

Dry solvents apparatus (Pure Solv Innovative Technology or similar)

Thin layer chromatography (TLC)

230–400 mesh silica gel (Silicycle or similar)

UV lamp (UVP-UVGL-25, 4W, 254/365nm or similar)

Standard PPE such as protective glasses, nitrile gloves and flame-retardant lab coat (Note: Any specific additional PPE and SOPs required are indicated in the procedure).

3.2. Reagents

All the reagents and solvents were used as purchased without further purification unless otherwise stated. Reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Glen Research, Chem Impex, Fisher, Acros and Oakwood Chemicals. Deuterated solvent for NMR characterization were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories.

3.3. Preparation of guanidinylated aminoglycosides

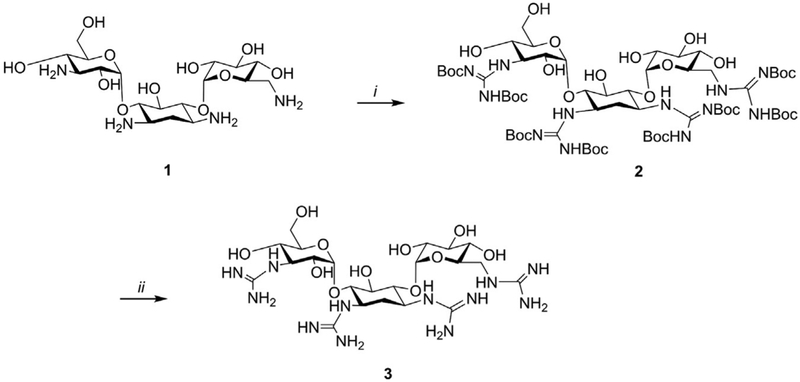

Increasing the chemical diversity of the receptors is often a good strategy to enhance the differential binding to RNA motifs. For example, the amino group of aminoglycosides can be further functionalized by introducing guanidine moieties, which were previously demonstrated to enhance RNA recognition (Luedtke, Baker, Goodman, & Tor, 2000; Luedtke, Carmichael, & Tor, 2003). A representative synthetic scheme and procedure for the aminoglycoside kanamycin (1) is shown below (Fig. 4). The same procedure might be applied to similar small molecules.

Fig. 4.

Synthesis of guanidinylated kanamycin (3) Reagents and conditions: (i) N,N′-di-Boc-N″-triflylguanidine (8 equiv.), TEA (10 equiv.), water/dioxane, 3 d, rt. (ii) 1M HCl aq., EtOAc, 4h, rt.

Preparation of 2

Dissolve kanamycin (0.041mmol, 1 equiv.) in deionized water (0.35mL) and 1,4-dioxane (1.71mL, 0.02M) into a 5mL round bottom flask.

While stirring, add N,N′-di-Boc-N″-triflylguanidine (8 equiv.).

After 5min of stirring, slowly add triethylamine (10 equiv.) and stir for 3 days at room temperature. Check the progress by TLC (DCM/MeOH 90:10; Rf starting material ~0.05; Rf product ~0.5).

Extract with CH2Cl2 (×3) and wash with brine (×3).

Dry the organic layer using anhydrous Na2SO4, filter, and evaporate under vacuum.

Purify the residue by silica column flash chromatography (90:10 DCM/MeOH) and dry in vacuo to yield the desired product as a white solid (yield 90%).

Confirm identity and purity by 1H and 13C NMR, and HRMS (Eubanks et al., 2017).

Preparation of 3

Dissolve 2 (0.034mmol, 1 equiv.) in ethyl acetate (0.86mL, 0.03M) and 1M aqueous HCl (0.074mL).

Stir the solution at room temperature for 4h and check by TLC (DCM/MeOH 95:5; Rf starting material ~0.85; Rf product ~0.05).

Dilute the solution with toluene (3.2mL) and concentrate in vacuo.

Resuspend 3 in water (4mL) and lyophilize (yield 95%).

Confirm identity and purity by 1H and 13C NMR and HRMS (Eubanks et al., 2017).

3.4. Preparation of BFU phosphoramidite

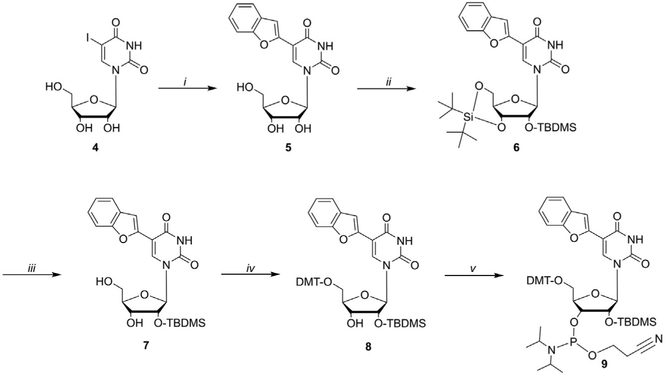

The monomeric phosphoramidite of the fluorescence label BFU to be used for solid phase synthesis is prepared starting from the commercially available 5-iodouridine (4) in five steps (Fig. 5). Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling is used to connect the benzofuran moiety at the C5 position of uridine. Two-step one-pot sequential protection of the 3′-5′ hydroxyl groups and 2′ hydroxyl group, followed by selective deprotection of the 3′ and 5′ positions afford intermediate 7. Protection of the 5′-position using DMT, followed by installation of the O-phosphoramidite group at the 3′ hydroxyl provide the final monomeric building block 9.

Fig. 5.

Synthesis of the BFU phosphoramidite (9). Reagents and conditions: (i) BFBA (1.3 equiv.), KOH (2 equiv.), Na2PdCl4 (10mol%), water, 1h, 90°C, MW. (ii) TBS-triflate (1.2 equiv.), dry DMF, 15min, 0°C; then imidazole (12 equiv.), 10min, rt.;then TBDMS-Cl (4 equiv.), 3h, 60°C. (iii) HF-pyridine (~70% HF, 5 equiv.), pyridine (10 equiv.), dry DCM, 2h, −5°C to rt. (iv) DMT-Cl (5 equiv.), dry pyridine, 6h, rt. (v) 2-cyanoethyl N,N, N′,N′-tetraisopropylphosphorodiamidite (3 equiv.), ETT (1.3 equiv.), dry DCM, 3h, 65°C, MW.

Preparation of 5

Dissolve 5-iodouridine (4, 0.70mmol, 1 equiv.), 2-benzofuranylboronic acid (1.3 equiv.), and potassium hydroxide (2.0 equiv.) in 4.0mL (0.175M) of deionized water in a microwave vial (Note: choose appropriate microwave vial according to vendor indication).

Purge the solution with a nitrogen flow for 20min.

Add an aqueous solution of Na2PdCl4 (10mol% relative to 4) and purge with a nitrogen flow for further 5min.

Seal and stir under microwave irradiation at 90°C, high absorption, for 1h.

Chill the vial on ice for 30min and collect the white precipitate by vacuum filtration.

Rinse the solid with water (×2), and hexanes (×3).

Resuspend the solid in ~5mL of deionized water and lyophilize to yield a white fluffy solid (yield 75%).

Confirm identity and purity by 1H and 13C NMR, HRMS and RP-HPLC (Eubanks et al., 2017).

A small impurity attributed to de-glycosilated product can be present. This can be removed by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc/MeOH 95:5) or carried onto the next step and removed in the following purification.

Preparation of 6 (Note: this reaction must be performed under anhydrous conditions)

Dissolve compound 5 (0.88mmol, 1 equiv.) in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (4.4mL, 0.2M) in a 15mL round bottom flask and stir at −5°C under argon atmosphere.

Slowly add di-tert-butylsilyl-bis(trifluoromethansulfonate) ((t-Bu)2Si (OTf)2) (1.2 equiv.) drop-wise (Note: a rate of addition of 1drp/5s or slower is necessary for the reaction to proceed) and allow to react at room temperature for 15min.

Check starting material consumption by TLC (EtOAc:MeOH 9:1; Rf starting material ~0.65). If the starting material is still present, slowly add ((t-Bu)2Si(OTf)2) in 0.25 equiv. increments until completion.

Quench the solution by adding imidazole in portions (12.0 equiv.) and stir for 10min at room temperature.

Add tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (4.0 equiv., check Safety Data Sheet (SDS) for safety recommendations) and attach a reflux condenser to the reaction flask.

Heat the solution to 60°C for 3h and confirm the progress of the reaction by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc 80:20; Rf starting material ~0.1; Rf product ~0.7).

Allow the reaction to cool to room temperature and chill the flask in an ice bath before adding water (10× dilution).

Collect the white precipitate by vacuum filtration.

Isolate the pure product 6 via silica column flash chromatography (gradient from 100% DCM to DCM/MeOH 98:2) as a white solid (yield 89%).

Confirm identity and purity by 1H and 13C NMR, HRMS and RP-HPLC (Eubanks et al., 2017).

Preparation of 7

Dissolve 6 (0.28mmol, 1 equiv.) in freshly distilled anhydrous CH2Cl2 (1.4mL, 0.2M) in a polypropylene test tube and stir at −5°C.

Prepare a separate solution by diluting HF-pyridine (~70% HF, 5.0 equiv.) with anhydrous pyridine (10 equiv.) at 0°C in a polypropylene test tube (IMPORTANT safety note: HF is strongly corrosive and should be used in a ventilated fume hood. SDS should be consulted before use. Avoid the use of glass throughout the procedure until the reaction is quenched. Additional PPE such as neoprene gloves, apron and face-mask should be used when performing the reaction).

Add slowly the HF-pyridine solution to the CH2Cl2 solution and stir for 2h. Check the progress by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc 85:15; Rf starting material ~0.6; Rf product = ~0.35; TLC sample can be obtained by adding 1μL of reaction mixture to 100μL of saturated aqueous Na2CO3 solution. Product was extracted with 50μL of EtOAc and spotted on the TLC plate).

Dilute the mixture with CH2Cl2 (5×) and quench by slowly adding a saturated, aqueous Na2CO3 solution (5×).

Separate the organic layer and wash with sat. NaHCO3 (×2), and brine solution (×2).

Dry the organic layer with anhydrous Na2SO4, filter, and dry in vacuo.

Purify the crude product via silica column flash chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield 7 as a white solid (yield 81%).

Confirm identity and purity by 1H and 13C NMR, HRMS and RP-HPLC (Eubanks et al., 2017).

Preparation of 8 (Note: this reaction must be performed under anhydrous conditions)

Dissolve dried 7 (0.25mmol, 1 equiv.) in anhydrous pyridine (2.5mL, 0.1M) while stirring at 0°C under a stream of nitrogen.

Add 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl chloride (5.0 equiv.), allow the solution to warm to room temperature and stir for 6h. Check reaction progress by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAC 65:35+3% TEA; Rf starting material ~0.4; Rf product ~0.6).

Pour the solution in water and extract with DCM (3×).

Wash the organic layer with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (×2) and then brine (×2).

Dry the organic layer using anhydrous Na2SO4, filter, and dry in vacuo.

Purify the crude product via silica column flash chromatography (gradient from Hexanes/EtOAc 97:3+3% TEA to 50:50+3% TEA) to yield 8 as a white solid (yield 80%) (Note: silica gel required pretreatment with Hexanes:EtOAc 97:3+3% TEA by vigorous stirring for at least 10min).

Confirm identity and purity by 1H and 13C NMR, HRMS and RP-HPLC (Eubanks et al., 2017).

Preparation of 9 (Note: this reaction must be performed under anhydrous conditions)

Add anhydrous 8 (0.193mmol, 1 equiv.) and 5-ethylthio-1H-tetrazole (1.3 equiv.) to an oven-dried microwave vial purged with argon and leave under high-vacuum for 12h.

Dissolve the solids using freshly distilled anhydrous CH2Cl2 (1.2mL, 0.16M) under argon atmosphere.

Add reagent 2-Cyanoethyl N,N,N′,N′-tetraisopropylphosphorodiamidite (3 equiv.) dropwise via syringe.

Stir the solution under microwave irradiation at 65°C, low absorption, for 3h.

Check reaction progress by TLC (Hexanes/EtOAc 75:25+3% MeOH; run the TLC plate twice to provide enough separation between diasteroisomers and starting material; Rf starting material ~0.65; Rf product 1–0.6; Rf product 2–0.7).

Load the crude directly to a silica column flash chromatography (gradient from 10% EtOAc (HPLC grade) in pentane (HPLC grade)+3% TEA to 80% EtOAc (HPLC grade) in pentane (HPLC grade)+3% TEA; Note: silica gel requires pretreatment with pentane:EtOAc 90:10+3% TEA by vigorous stirring for at least 10min).

Collect both diastereomers and dry in vacuo.

Confirm the identity and purity by 1H and 31P NMR. An H-phosphonate impurity of 2–10% of the total yield can be present (31P δ 8.01 and 7.57ppm) and is not expected to interfere with the solid phase synthesis. If a larger amount of impurities is present, the crude can be re-purified by re-crystallization from DCM using cold hexanes or a short silica gel column purification using DCM/ACN/TEA 98:1:1) (Eubanks et al., 2017).

Due to instability, the compounds should be stored at −20°C, in the dark, under inert atmosphere and readily used for solid phase synthesis.

4. Preparation of the RNA training set

4.1. Equipment

Oligonucleotide synthesizer (MerMade 6 &12 or similar)

Control Pore Glass columns (1000Å from Glen Research or similar)

Vacuum manifold

Speed-vacuum evaporator or constant airflow streamer

Polydivinylbenzene 4,4′ dimethoxytrityl affinity columns (GlenPack cartridges or similar)

Centrifuge (Eppendorf 5810R or similar)

Nanodrop spectrometer

Gel electrophoresis apparatus

Gel Imager (Biorad or similar)

4.2. Reagents

All the reagents are used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Glen Research. Ac-A-CE, Ac-C-CE, Ac-G-CE, U-CE (purchased from ChemGenes) and BFU phosphoramidite solutions should be used within a week from their preparation.

4.3. Automated solid-phase synthesis of the training set

The BFU-labeled RNA strands were synthesized using a MerMade 6 & 12 synthesizer. A detailed description of the use of this machine is beyond the scope of this chapter and can be found in the manual provided by the supplier. For this reason, only an overview of the process will be provided.

Dissolve the commercially purchased orthogonally protected Ac-A-CE, Ac-G-CE, Ac-C-CE, U-CE, and the synthesized BFU phosphoramidite in anhydrous acetonitrile at a final concentration of 67mM.

Choose the appropriate columns containing the desired first 3′ nucleotide attached.

A script is prepared containing the following information: desired sequences; conditions for deprotection of the 4,4′ dimethoxytrityl group with 3% trichloroacetic acid in dichloromethane (typically two cycles, 20s wait time, 12s drain time, 2s equalize time); conditions for coupling of the next nucleotide using a tetrazole catalyst 0.25M ETT in acetonitrile (typically two cycles, 180s wait time, 12s drain time, 2s equalize time); conditions of capping of the unreacted 5′ hydroxyl groups with a mixture of acetic anhydride (Cap A) and N-methylimidazole (Cap B) dissolved in tetrahydrofuran/pyridine (typically two cycles, 14s wait time, 12s drain time, 2s equalize time); conditions for the oxidation of the phosphodiester bond with 0.1M iodine in pyridine/water mixture (typically one cycle, 40s wait time, 14s drain time, 2s equalize time); the DMT-on option.

Trityl log can be used to check coupling efficiency (normally between 85% and 100%), if available.

4.4. Cleavage, deprotection and purification of RNA

After completion of the synthesis, insert the RNA columns on the vacuum manifold, and elute the RNA by adding 333μL of a 1:1 solution of 30% aq. ammonium hydroxide and 30% aq. methylamine and let the solution to drain under gravity for 7.5min.

Drain the remaining solution under vacuo and repeat step (a) twice.

Incubate the collected solution at room temperature for 2h to remove the acetyl protecting group from the nucleobases.

Remove the solvent using a speed-vac or by flushing the solution with a gentle stream of air (Note: exhaustive drying should be achieved to obtain optimal yield).

To deprotect the 2′ hydroxyl group, dissolve the obtained crystals in 115μL dimethylsulfoxide, 60μL triethylamine, and 75μL of triethylamine:hydrogen fluoride (30%) and heat for 2.5h at 65°C (IMPORTANT safety note: HF is strongly corrosive and should be used in a ventilated fume hood. Avoid the use of glass throughout the procedure until the reaction is quenched. Additional PPE such as neoprene gloves, apron and face-mask should be used when performing the reaction).

After cooling to room temperature, add 1.75mL of quenching buffer (Glen Research) to the solutions.

Insert a 3–5μm polydivinylbenzene 4,4′ dimethoxytrityl affinity column into the appropriate inserts of the vacuum manifold.

Precondition the column by sequentially adding 0.5mL acetonitrile and 1mL of a 2M solution of triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) in water. Drain the liquid using the vacuum after each addition.

Add the RNA solutions to the column and wash with 1mL of a 1:9 acetonitrile:2M triethylammonium acetate solution, 1mL of RNase free water, 1mL of 2% TFA solution in water (×2), 1mL RNase free water (×2) and discard the eluted solutions.

In a clean and sterile vial, elute the RNA from the column by adding 1mL of 1M ammonium bicarbonate:30% acetonitrile.

Perform ethanol precipitation by adding 10% volume of sodium acetate (3M pH 5.2) and 3 volume of ice-cold absolute ethanol.

Leave at −20°C for 16h and centrifuge for 2h at 4°C at 4000rpm.

Remove the supernatant after centrifugation.

Repeat the ethanol addition and centrifugation steps (k–m) (×2).

Lyophilize the residue to remove any remaining ethanol.

Dissolve the RNA sequences in phosphate buffer (10mM NaH2PO4, 25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, pH 7.3), and analyze the concentration using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer.

Determine the purity of the RNA with a pre-cast 15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) run with 1× Tris, borate, and EDTA (TBE) buffer at 180V for ~2h.

Stain the gel using diamond dye nucleic acid for 20min and image the gel using a UV gel imager.

5. Assay protocol

5.1. Equipment

Calibrated Analytical balance

Nanodrop spectrophotometer

96-well plates (Corning 96 well cell culture plate—V bottom or similar)

384-well plates (Corning 384 well, low volume, round black bottom or similar)

Pipette set (Eppendorf research plus or similar)

Multichannel pipette (Eppendorf 10–100 or similar)

Electronic dispenser (Eppendorf Repeater E3 or similar)

Sterilized pipette tips

Plate-reader (Molecular Devices SpectraMax or BMG CLARIOstar or similar)

Shaker (Corning PC-101; New Brunswick Scientific Excella E2 Platform or similar)

Centrifuge compatible with well plates (Eppendorf 5810R or similar)

5.2. Buffers and reagents

Buffer A: 25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.1mM EDTA, pH 7.3; or variants of this buffer

Molecular biology grade DMSO

RNase free water (nuclease-free)

Small molecules aminoglycosides stock solution (2mM in 10% DMSO in water)

RNA training set stock solution in Buffer A.

5.3. Procedure

Weigh the commercially purchased and synthesized small molecules (amikacin, apramycin, 2-deoxystreptamine, dihydrostreptomycin, kanamycin, neamine, neomycin, streptomycin, sisomicin, guanidino-paromomycin, and guanidino-kanamycin) and dissolve them in 10% DMSO in RNase-free water for a final concentration of 2mM. Vortex, spin-down and visually inspect the mixture to ensure complete solubilization.

Perform two serial dilutions for each small molecule in two separated 96-well plates (plate A and plate B). Table 1 indicates the amount of buffer and stock solutions required in each well. Each solution should be mixed thoroughly to ensure homogeneity.

In a 384-well plate, add small molecule (10μL) with a 10μL multichannel pipette by filling the 16 wells in a single column by alternating solutions from the 96-well plate B and A.

Dilute the stock solutions of each RNA to 400nM concentration using Buffer A.

Add 10μL of the RNA solutions to each well for a final concentration of 200nM. A repeater pipette should be used for accelerating this procedure and to reduce possible photobleaching of the fluorophore.

Cover the plate and shake at 100rpm for 5min to ensure homogeneous solutions.

Centrifuge the plate at 3000rpm for 1min to remove any air bubble.

Incubate the plate in the dark for 15min to reach the binding equilibrium.

Insert the plate into the plate reader and measure the fluorescence intensity of each well by exciting the samples at 322nm and reading emission at 455nm. 50 flashes/read (Note: for measurement at 37°C, an optically clear seal should be used to minimize evaporation and reduce error. Excitation and emission wavelengths are specific for BFU and should be adjusted for different fluorophores).

Export the raw fluorescence data in an excel format.

Repeat the experiment in triplicate.

Table 1.

Serial dilutions of aminoglycosides performed in two 96-well plates (plate A and B).

| Equiv. (plate A) |

Vol (μL) | Buffer vol (μL) |

SM conc. (μM) |

Equiv. (plate B) |

Vol (μL) | Buffer vol (μL) |

SM conc. (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0.96 | 299.04 | 6.4 | 20 | 1.2 | 298.8 | 8 |

| 10 | 187.50 | 112.50 | 4 | 14 | 210.00 | 90.00 | 5.6 |

| 7 | 210.00 | 90.00 | 2.8 | 8 | 171.43 | 128.57 | 3.2 |

| 5 | 214.29 | 85.71 | 2 | 6 | 225.00 | 75.00 | 2.4 |

| 3 | 180.00 | 120.00 | 1.2 | 4 | 200.00 | 100.00 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 200.00 | 100.00 | 0.8 | 2.5 | 187.50 | 112.50 | 1 |

| 1 | 150.00 | 150.00 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 180.00 | 120.00 | 0.6 |

| 0 | 0.00 | 300.00 | 0 | 0.5 | 100.00 | 200.00 | 0.2 |

The volumes listed in the first row indicate the amount of the 2mM stock solution to be diluted with buffer. The volumes in the following rows indicate the amount of the solution from the well above to be diluted with buffer to obtain the desired small molecule (SM) concentration.

6. Statistical methods for data analysis

6.1. Overview of principal component analysis and leave-one-out cross validation

Large amounts of data often require a differential statistical method to ease the interpretation. PCA is a non-biased statistical method that reduces the dimensionality of the dataset by utilizing its inherent variance (Jolliffe & Cadima, 2016; Wenderski, Stratton, Bauer, Kopp, & Tan, 2015). In PCA, a covariance matrix is created from a multivariate dataset, from which eigenvalues and eigenvectors (non-zero vectors that change by the factor eigenvalue) are determined. The dataset is transposed into new principal component space, which is dependent on the variance of the dataset and therefore might produce clustering. The principal components are ranked according to the percentage of variance explained, and normally 95% of the variance is required for a complete analysis of the dataset.

PCA does not inherently provide the predictive power of the analysis. For this reason, another statistical approach is required to assess the significance of the clustering generated from PCA and possible overtraining, and therefore to determine if the model can be used in predictive assays. Leave-one-out-cross validation (LOOCV) is a validation method that partitions the entire dataset between a training set and a smaller validation subset (Kim, 2009). A predicting model is generated from the training set and the validation set is analyzed and compared to its determination in the original entire dataset by using the RNA motifs as the basis of the prediction. The process is normally iterated by using different partitions and the averaged prediction is used to validate the predictive power of the experimental dataset. A predictive power of 100% indicates that LOOCV recapitulates the PCA clusters as if the data were not removed, while lower percentages showing deviations from the PCA plot and the validation method. A low predictive power might indicate potential underfitting (i.e., not enough training data to generate a good predictive model) or overfitting (i.e., the predictive model cannot successfully generalize new observations because the training set is too large) and adjustment of the dimension of the training data might be required (Stewart, Ivy, & Anslyn, 2014).

6.2. Equipment

PC work station (Dell Work station equipped with Intel (R) Xeon (R) CPU E5-2680 v2 @ 2.80GHz 2 processors or similar)

Excel Microsoft office

XLSTAT package

RStudio package

6.3. Principal component analysis (PCA) in PRRSM

PRRSM requires the entirety of the raw fluorescence data from the aminoglycoside titrations experiments to achieve structural classification. This dataset can be organized in an excel sheet in which the fluorescence of each aminoglycoside (column) is associated with the relative RNA structure (row). PCA can be performed using XLSTAT software as reported below.

In excel, open the XLSTAT menu bar and select “Analyzing data—Principal Component Analysis”

In the windows, insert the “observations/variable table” by selecting the cells containing the raw fluorescence.

Select “Variable labels” and insert the cell containing the labels (the labels should indicate motifs or individual sequences identifiers).

Select the PCA type and in the “outputs” panel the desired values necessary for the analysis.

Press “Ok” to perform PCA.

Use Scree plot to assess the percentage of variance explained by each principal component and choose which type of graphs (2D or 3D) will be a better representation of the variance.

Use the biplots to assess the clustering.

Insert confidence ellipses by replotting the “factor scores” of the selected principal components table using a scatter plot (Visualize data-Scatter Plot) selecting the options “confidence ellipses.”

6.4. Leave-one-out-cross validation (LOOCV)

This analysis can be performed in RStudio using the following procedure:

Import the PCA dataset as .csv file.

-

Load the caret and klaR libraries using the commands.

“library(caret)”

“library(klaR)”

-

Partition the dataset with a partition fraction of 0.875 using the command (Note: this is an eightfold cross validation, but any value between 0 and 1 can be used).

trainIndex <- createDataPartition(‘Nameof the dataset here_1’$ Name, p=0.875, list=FALSE)

-

Name the partitions of the “trainindex”. The training set and validation set are renamed to “data_train” and “data_test”, respectively, using the following command:

data_train <- ‘name of the imported file’[ trainIndex,]

data_test <- ‘ name of the imported file’[-trainIndex,]

-

Run a Naïve Bayes algorithm of the training set to create a predictive model (named “model”) using the following command:

model <- NaiveBayes(Name~., data=data_train)

-

Make predictions using the validation set (data_test) using the following command:

predictions <- predict(model, data_test)

-

Summarize the results by exporting a confusion matrix and a predictive percentage table (Tables 2-4) for each motif using the following command:

confusionMatrix(predictions$class, data_test$Name).

Table 2.

Example of confusion matrix and statistics reference obtained from PRRSM using 10mM NaH2PO4, 25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 8mM PEG 12000, pH 7.4 at 37°C.

| Prediction | AIL | Bulge | HPL | IL | Stem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIL | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bulge | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HPL | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| IL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Stem | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

Table 4.

Example of statistics by class obtained from PRRSM using 10mM NaH2PO4, 25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 8mM PEG 12000, pH 7.4 at 37°C.

| Class: AIL | Class: Bulge | Class: HPL | Class: IL | Class: Stem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Specificity | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Pos Pred Value | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Neg Pred Value | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Prevalence | 0.1875 | 0.2500 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 |

| Detection Rate | 0.1875 | 0.2500 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 |

| Detection Prevalence | 0.1875 | 0.2500 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 | 0.1875 |

| Balanced Accuracy | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

6.5. Data processing

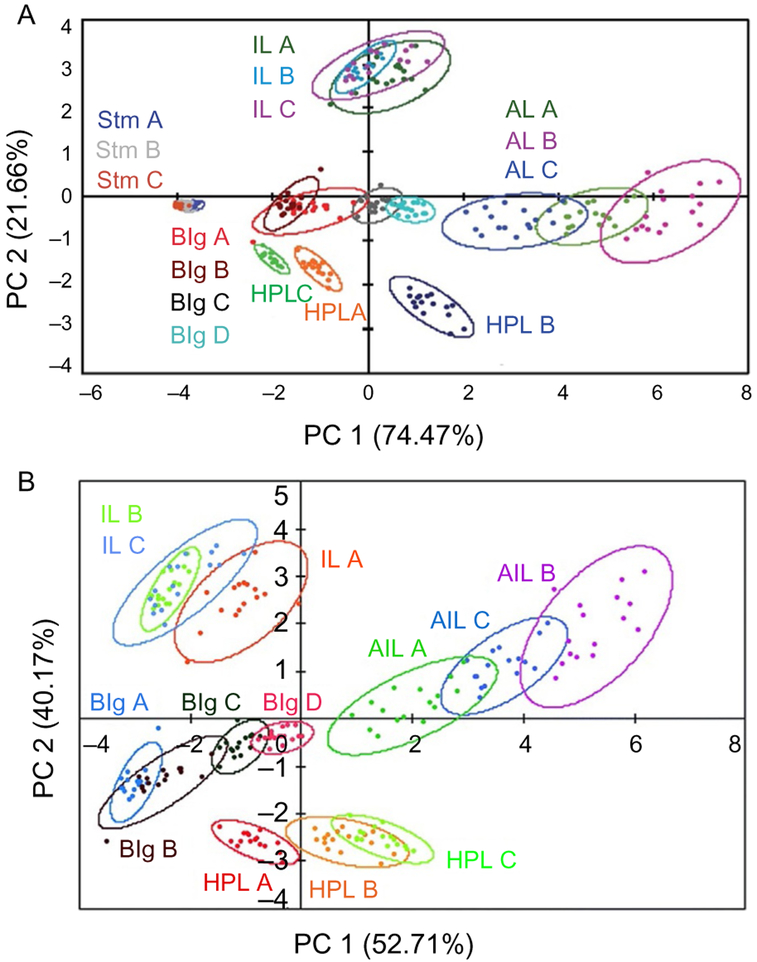

As discussed in Section 2.4, the predictive power of PRRSM is strongly dependent on the assay conditions such as temperature, ionic strength, pH and buffers. Furthermore, data processing might also affect the predictive power and hide subtle differences within RNA motifs/sequences. After performing PCA with the entirety of the dataset, the loading plots relative to each small molecule should be analyzed and compared for each motif. In case some aminoglycosides do not show differential binding (i.e., loading factor close to 0), their fluorescence data can be removed to increase the clustering of the PCA. Removal of entire motifs might also increase the overall classification of PRRSM. For example, RNA stem sequences are normally poorly differentiated in PRRSM due to lower fluorescence intensities of BFU and reduced binding affinity of aminoglycosides, and their removal from the dataset enhances the predictive power of the remaining sequences (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the amount of data points should be adjusted in each case for achieving optimal differentiation as a limited number of observations (i.e., number of receptors and/or limited data points from the serial dilutions) might not generate a clear classification.

Fig. 6.

(A) PCA plot of the entire training set obtained in 10mM NaH2PO4, 25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 8mM PEG 12000, pH 7.4 at 37°C. (B) PCA plot after removal of the stems under the same experimental conditions. Adapted from Eubanks, C. S., & Hargrove, A. E. (2017). Sensing the impact of environment on small molecule differentiation of RNA sequences. Chemical Communications, 53(100), 13363–13366 with permission of the Royal Chemical Society.

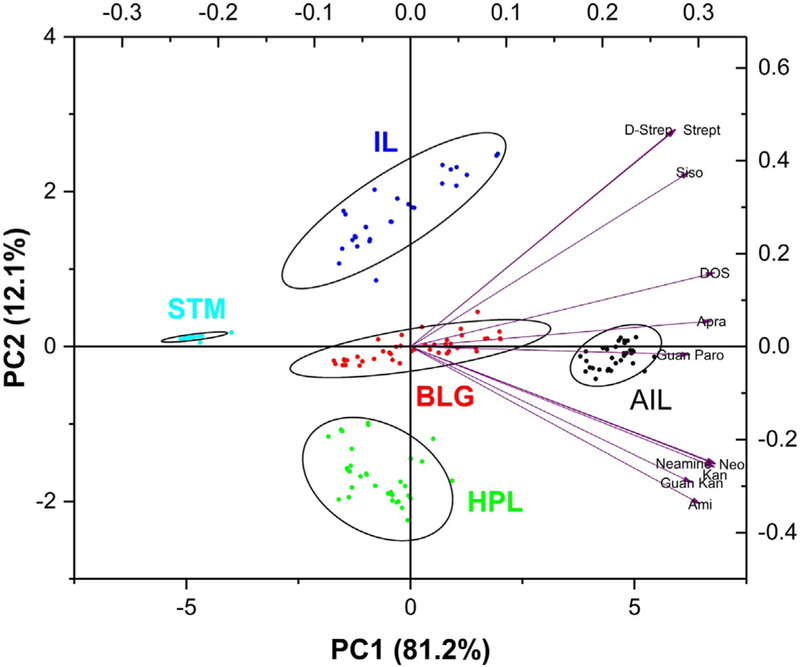

6.6. Interpretation of PRRSM

Information on selective RNA recognition can be derived by complementing PRRSM with the computational analysis of small molecules and RNA structures. For example, correlation between small molecules chemoinformatic properties and their PCA loading factor might be used to discern trend in molecular properties (such as hydrogen bond donor/acceptor, aromaticity, number of rotatable bonds and other physicochemical parameters) responsible for selective recognition of RNA sequences and motifs (Fig. 7). RNA motifs features exploited by small molecules for their differentiation (such as size, shape, and flexibility) can be identified via structural analysis of RNA motifs using computational tools, including structure prediction programs and molecular dynamics simulations. Furthermore, differences in the PCA plot obtained by varying experimental conditions (i.e., ionic strength, buffer, pH, temperature and presence of a molecular crowder) can be used to gain important information on the determinants at the basis of the interaction. For example, in our case study involving aminoglycoside-RNA interactions (Eubanks & Hargrove, 2017), PRRSM demonstrated how electrostatic interactions are responsible for the binding affinity (i.e., decreased predictive power at high ionic concentration) but might compromise binding selectivity when their contribution to the binding is increased (i.e., decreased predictive power at lower pH), though other contributions from RNA structural rearrangement cannot be ruled out. Additionally, PRRSM suggested that the dynamic nature of the RNA motifs might be exploited for distinguishing sequences containing the same motif. In particular, the reduced separation in PCA observed for experimental conditions that affect conformational flexibility of the RNA (i.e., high magnesium concentration) and the enhanced predictive power achieved using conditions that mimic a cellular environment (i.e., 37°C, PEG 1200) in which higher conformational freedom is expected, suggest that increased conformational dynamics might favor RNA selective recognition.

Fig. 7.

PCA plot of the training set including the loading factors (purple arrows). From this plot is deduced that while all the aminoglycosides contribute PC1, 2-DOS, apramycin and guanidinylated paranomycin have none or limited contribution to differentiation along PC2.

Altogether, PRRSM can be used to gain information on both RNA and small molecule properties that confer selective RNA recognition.

7. PRRSM as potential structure and function prediction tool

Along with providing important information on selective RNA recognition by small molecules, the differential binding of PRRSM has the potential to be complementary to other prediction tools for identifying motifs of structurally unknown RNA analytes. In proof of concept studies involving structurally known RNA constructs, PRRSM correctly classified both the apical loop and the bulge regions of the HIV1-TAR construct despite the presence of both motifs (Eubanks et al., 2017). Furthermore, PRRSM was sensitive to structural rearrangement of RNA constructs such as the PreQ1 and fluoride riboswitch and correctly identified motifs and essential residues for RNA folding (Eubanks et al., 2019). We envisage that these classification features have the potential to be extended to unknown RNA constructs. In an ideal experiment, the fluorescent label BFU is placed at selected positions of the RNA sequence that are predicted to be part of structural motifs or considered important for structural rearrangement in case a folding event is hypothesized. The PCA or preferably LDA plots defined by an RNA training set containing known structural motifs is then input with the fluorescence variation induced by small molecules binding at each position of the unknown structure. The localization of each input will be used to determine if the modified position fall into specific secondary structures and/or is involved in structural rearrangements. A further potential extension would be using PRRSM to classify unknown structural rearrangement induced by base modifications and/or protein binding and tertiary motifs. Ultimately, we envision that by exploiting the relationship between structure and function of RNA, PRRSM could be utilized for investigating and classifying the function of unknown RNA structures after generation of a dedicated “functional” training set.

8. Summary and conclusion

Targeting RNA (both coding and non-coding) is an attractive strategy for increasing the number of druggable targets in vivo. Small molecules are particularly attractive for their tunable physicochemical properties and increased cellular uptake relative to oligonucleotides. However, there is currently a gap in knowledge of the principles governing RNA recognition by small molecules, and in particular the descriptors of small molecules that enable selective binding, as well as which RNA structures may be most targetable. Our strategy (PRRSM) is a high-throughput method to determine the binding properties of both small molecules and RNA constructs with the advantage that strong and selective small molecule binders are not required. Furthermore, differential small molecule recognition can be exploited to interrogate the conformational properties, including conformational switching, of biologically relevant RNA constructs. This critical insight into discernible structural patterns of common RNA topologies will provide the basis for the rational design of selective RNA ligands to target therapeutically important ncRNA fragments.

Table 3.

Example of overall statistics obtained from PRRSM using 10mM NaH2PO4, 25mM NaCl, 4mM MgCl2, 0.5mM EDTA, 8mM PEG 12000, pH 7.4 at 37°C.

| Accuracy | 1 |

|---|---|

| 95% CI | (0.8911, 1) |

| No Information Rate | 0.25 |

| P-Value [Acc > NIR] | <2.2e-16 |

| Kappa | 1 |

| Mcnemar’s Test P-Value | NA |

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Hargrove lab for providing valuable feedback on the chapter. The authors acknowledge financial support for this work from Duke University and the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Maximizing Investigator’s Research Award (MIRA) Grant/Award Number: R35GM124785.

References

- Ackermann D, & Famulok M (2013). Pseudo-complementary PNA actuators as reversible switches in dynamic DNA nanotechnology. Nucleic Acids Research, 41, 4729–4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andronescu M, Bereg V, Hoos HH, & Condon A (2008). RNA STRAND: The RNA secondary structure and statistical analysis database. BMC Bioinformatics, 9(1), 340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj A, Miranda OR, Kim I-B, Phillips RL, Jerry DJ, Bunz UHF, et al. (2009). Detection and differentiation of normal, cancerous, and metastatic cells using nanoparticle-polymer sensor arrays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(27), 10912–10916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate JH, & Doudna JA (2000). [12] Solving large RNA structures by X-ray crystallography. In Methods in Enzymology: Vol. 317 RNA–ligand interactions, part A. (pp. 169–180). Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR, & Steitz JA (2014). The noncoding RNA revolution—Trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell, 157(1), 77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Pollack L (2016). SAXS studies of RNA: Structures, dynamics, and interactions with partners. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA, 7(4), 512–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CY, Chou F-C, & Das R (2015). Chapter two—Modeling complex RNA tertiary folds with Rosetta In Chen S-J & Burke-Aguero DH (Eds.), Computational methods for understanding riboswitches (pp. 35–64). Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittapragada M, Roberts S, & Ham YW (2009). Aminoglycosides: Molecular insights on the recognition of RNA and aminoglycoside mimics. Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry, 3, 21–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly CM, Moon MH, & Schneekloth JS Jr. (2016). The emerging role of RNA as a therapeutic target for small molecules. Cell Chemical Biology, 23(9), 1077–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlic A, & Hargrove AE (2018). Targeting RNA in mammalian systems with small molecules. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA, 9(4), e1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks CS, Forte JE, Kapral GJ, & Hargrove AE (2017). Small molecule-based pattern recognition to classify RNA structure. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 139(1), 409–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks CS, & Hargrove AE (2017). Sensing the impact of environment on small molecule differentiation of RNA sequences. Chemical Communications, 53(100), 13363–13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks CS, & Hargrove AE (2019). RNA structural differentiation: Opportunities with pattern recognition. Biochemistry, 58(4), 199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eubanks CS, Zhao B, Patwardhan NN, Thompson RD, Zhang Q, & Hargrove AE (2019). Visualizing RNA conformational changes via pattern recognition of RNA by small molecules. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 141(14), 5692–5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Chan D, Joseph J, Muuronen M, Coldren WH, Dai N, et al. (2018). Light-activated chemical probing of nucleobase solvent accessibility inside cells. Nature Chemical Biology, 14, 276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmer-Andersen JF, Kitamura M, & Anslyn EV (2006). Pattern-based discrimination of enantiomeric and structurally similar amino acids: An optical mimic of the mammalian taste response. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 128(17), 5652–5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart K, Nyström B, Öhman M, & Nilsson L (2005). Molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations of base flipping in dsRNA. RNA, 11(5), 609–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix M, Priestley ES, Joyce GF, & Wong C-H (1997). Direct observation of aminoglycoside – RNA interactions by surface plasmon resonance. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 119(16), 3641–3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AD, Glenn IC, Patrick AD, Ellington A, & Anslyn EV (2008). A pattern recognition based fluorescence quenching assay for the detection and identification of nitrated explosive analytes. Chemistry—A European Journal, 14(6), 1822–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarroux J, Morillon A, & Pinskaya M (2017). History, discovery, and classification of lncRNAs In Rao M (Ed.), Long non coding RNA biology. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, Vol. 1008, Singapore: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe IT, & Cadima J (2016). Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 374(2065), 20150202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-H (2009). Estimating classification error rate: Repeated cross-validation, repeated hold-out and bootstrap. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 53(11), 3735–3745. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura M, Shabbir SH, & Anslyn EV (2009). Guidelines for pattern recognition using differential receptors and indicator displacement assays. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 74(12), 4479–4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke NW, Baker TJ, Goodman M, & Tor Y (2000). Guanidinoglycosides: A novel family of RNA ligands. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 122(48), 12035–12036. [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke NW, Carmichael P, & Tor Y (2003). Cellular uptake of aminoglycosides, guanidinoglycosides, and poly-arginine. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 125(41), 12374–12375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPike MP, Sullivan JM, Goodisman J, & Dabrowiak JC (2002). Footprinting, circular dichroism and UV melting studies on neomycin B binding to the packaging region of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 RNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 30(13), 2825–2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti R, Lyskov S, Das R, Meiler J, & Gray JJ (2018). Web-accessible molecular modeling with Rosetta: The Rosetta online server that includes everyone (ROSIE). Protein Science, 27(1), 259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris KV, & Mattick JS (2014). The rise of regulatory RNA. Nature Reviews Genetics, 15, 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios MA, Nishiyabu R, Marquez M, & Anzenbacher P (2007). Supramolecular chemistry approach to the design of a high-resolution sensor array for multianion detection in water. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 129(24), 7538–7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan NN, Cai Z, Newson CN, & Hargrove AE (2019). Fluorescent peptide displacement as a general assay for screening small molecule libraries against RNA. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 17(7), 1778–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan NN, Ganser LR, Kapral GJ, Eubanks CS, Lee J, Sathyamoorthy B, et al. (2017). Amiloride as a new RNA-binding scaffold with activity against HIV-1 TAR. Medicinal Chemistry Communications, 8(5), 1022–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razi A, Ortega J, & Britton RA (2016). The impact of recent improvements in cryo-electron microscopy technology on the understanding of bacterial ribosome assembly. Nucleic Acids Research, 45(3), 1027–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DR, & Cheatham TE (2013). PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 9(7), 3084–3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim NN, & Feig AL (2009). Isothermal titration calorimetry of RNA. Methods, 47(3), 198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon L, Yang S, & Al-Hashimi HM (2014). Advances in the determination of nucleic acid conformational ensembles. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 65(1), 293–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S, Ivy MA, & Anslyn EV (2014). The use of principal component analysis and discriminant analysis in differential sensing routines. Chemical Society Reviews, 43(1), 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sztuba-Solinska J, Chavez-Calvillo G, & Cline SE (2019). Unveiling the druggable RNA targets and small molecule therapeutics. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 27(10), 2149–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanpure AA, & Srivatsan SG (2011). A microenvironment-sensitive fluorescent pyrimidine ribonucleoside analogue: Synthesis, enzymatic incorporation, and fluorescence detection of a DNA abasic site. Chemistry—A European Journal, 17(45), 12820–12827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijerina P, Mohr S, & Russell R (2007). DMS footprinting of structured RNAs and RNA-protein complexes. Nature Protocols, 2, 2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tius MA, & Kawakami JK (1995). The reaction of XeF2 with trialkylvinylstannanes: Scope and some mechanistic observations. Tetrahedron, 51(14), 3997–4010. [Google Scholar]

- Umali AP, & Anslyn EV (2010). A general approach to differential sensing using synthetic molecular receptors. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology, 14(6), 685–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umali AP, LeBoeuf SE, Newberry RW, Kim S, Tran L, Rome WA, et al. (2011). Discrimination of flavonoids and red wine varietals by arrays of differential peptidic sensors. Chemical Science, 2(3), 439–445. [Google Scholar]

- Velagapudi SP, & Disney MD (2014). Two-dimensional combinatorial screening enables the bottom-up design of a microRNA-10b inhibitor. Chemical Communications, 50(23), 3027–3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KD, Hajdin CE, & Weeks KM (2018). Principles for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17, 547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenderski TA, Stratton CF, Bauer RA, Kopp F, & Tan DS (2015). Principal component analysis as a tool for library design: A case study investigating natural products, brand-name drugs, natural product-like libraries, and drug-like libraries In Hempel J, Williams C, & Hong C (Eds.), Chemical Biology. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 1263, New York, NY: Humana Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KA, Merino EJ, & Weeks KM (2006). Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): Quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nature Protocols, 1, 1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Dix AV, & Tor Y (2009). FRET enabled real time detection of RNA-small molecule binding. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 131(48), 17605–17614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Umemoto S, & Nakatani K (2010). Fluorescent indicator displacement assay for ligand – RNA interactions. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 132(11), 3660–3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziehler WA, & Engelke DR (2000). Probing RNA structure with chemical reagents and enzymes. Current Protocols in Nucleic Acid Chemistry. 6.1.1–6.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Research, 31(13), 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]