Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Suicide is a public health problem, and the number of paraphenylenediamine (PPD)-containing hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions is increasing in developing countries. In order to better understand this situation, we aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence and complications associated with hair dye poisoning in developing countries.

METHODS:

We conducted a systematic review of epidemiological studies using MeSh terms and text keywords to identify studies from the inception to March 2016 about hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions in developing countries. A meta-analysis was used to calculate the pooled prevalence proportion of hair dye poisoning and its major complications. Data extraction, data analysis, and risk of bias assessment were performed.

RESULTS:

Thirty-two studies were included in the systematic review and 29 of these studies containing 5,559 subjects covering six countries were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence proportion of hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions was 93.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 91.6–95.4) with a mortality rate of 14.5% (95% CI = 11.1–17.9). Of these, 73.8% were female, and 26.2% were male (sex ratio: 2.7:1). The occurrence of angioneurotic edema in hair poisoning patients was 67.1% (95% CI = 56.6–77.6), and tracheostomy intervention was considered in 47.9% (95% CI = 22.7–73.2) patients with respiratory distress. Acute renal failure was noticed in 54.7% (95% CI = 34.5–74.9) of the pooled samples and mortality rates were 14.5% (95% CI = 11.1–17.9). The pooled rate of the population studied from Asia and Africa showed 94.6% (95% CI = 92.5–96.7) and 82.9% (95% CI = 70.6–95.3), respectively, ingested hair dye with suicidal intentions. Further, studies carried out in Africa showed slightly higher mortality of 15.1% (95% CI = 6.56–23.7) than the Asians 14.3% (95% CI = 10.5–18.1).

CONCLUSION:

This meta-analysis provided clear evidence of the prevalence of hair dye poisoning among individuals with suicidal intentions and had given robust evidence for policy making to curtail emerging PPD-containing hair dye poisoning in developing countries.

Keywords: Developing countries, hair dye poisoning, hair dye toxicity, household poisoning, paraphenylenediamine poisoning, suicides

Introduction

Self-harm is largely preventable. Risk behavior to attempt suicides and self-inflicted injuries has been increasing worldwide. It is estimated that suicides likely contribute to >2% of the global burden disease by the year 2020.[1] In particular, there was growing morbidity (suicide attempts) and mortality (suicide deaths) in several developing countries and placing a large part of the global suicide burden. The knowledge and awareness of the harmful effects of some commonly used household products such as organophosphate pesticides, oleander seeds, and hair dyes have turned them into hazardous suicidal agents in developing countries.

The use of henna-containing hair dyes for darkening gray hair started since 4000 years. With an increasing intrinsic human desire to improve their appearance, millions of consumers use hair dyes every day. Paraphenylenediamine (PPD) is an essential ingredient in hair dyes as oxidizing agent coupling with modifiers (resorcinol, m-phenylenediamine, m-aminophenols, and others) results in the colored reaction product. In developed countries, standard hair dye formulations contain a maximum of 2% PPD in 100 ml dye solution, which makes it less toxic if accidental poisoning occurs.[2] Due to lack of standard regulations in developing countries, these concentrations range from 2% to 90%.[3] Several epidemiological and toxicological studies have indicated the safety of hair dye through the topical route.[4,5] Although these are topically applied substances, several cases of severe human poisoning with suicidal intentions have been widely reported in developing countries, recently observed particularly in India, Sudan, Pakistan, Morocco, Egypt, and Tunisia.[6,7,8,9,10] The primary hair dye ingredients such as PPD and resorcinol can cause severe multiorgan toxicities on oral ingestion. For instance, PPD can cause severe angioneurotic edema leading to acute respiratory distress at an early phase and rhabdomyolysis, acute tubular necrosis resulting in acute renal failure (ARF) leading to poor prognosis, and death. Some of the other complications such as muscle tenderness, seizures, severe metabolic acidosis, hypotension, hypoglycemia, myocarditis, electrocardiographic changes, cardiac rhabdomyolysis, shock, discoloration of urine, and hepatitis were also reported. Given this situation, several studies have reported a large number of hair dye poisoning cases in the above-specified countries. Since no antidote is present to counter the hair dye poisoning, early effective clinical interventions to improve the patient outcomes are vital. However, until date, no systematic review had been conducted in this area. A better understanding of these issues could help public health officials to develop risk-minimizing strategies to counter the misuse of PPD-containing hair dyes among the general population in developing countries.

Therefore, in this study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the current literature related to hair dye poisoning among adult individuals with suicidal intentions attending health facilities reported by various studies from developing countries. Furthermore, the study also examined the major clinical complications and mortality associated with PPD-containing hair dye poisoning.

Materials and Methods

We used established methods recommended by the Cochrane guidelines to conduct the meta-analysis following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis statement [Appendix 1].

Data source and search strategies

We searched for published studies related to hair dye poisoning in the following electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Embase) from their inception to March 2016. The search phrase was carried using the MeSH terms and text keywords: (poisoning*) OR (hair dye poisoning*) OR (self-harm) OR (PPD poisoning*) OR (PPD*) OR (suicides*). Citations were screened at the title and abstract level and retrieved as a full report if they were considered relevant.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Adult patients aged 18 years or above who had attended health facilities because of PPD-containing hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions

Studies conducted in developing countries

The study must be an original article or reporting >10 cases (for meta-analysis)

All the papers written in the English language were considered.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded the following studies: (1) nonpatient related studies (analytical, immunological, topical application, autopsy, and knowledge, attitude, and practice studies) and (2) studies conducted on children.

The review was limited to studies that reported the following:

Hair dye poisoning patients with suicidal intentions

Early-phase complications – angioneurotic edema or cervicofacial edema due to hair dye ingestion

Life-saving tracheostomy intervention in hair dye poisoning patients with respiratory distress

Late-phase complications – ARF in hair dye intoxication patients

Death due to hair dye poisoning.

Review process

All the records that were identified through systematic searches of the electronic databases were screened and independently abstracted data using prespecified forms. After the records were extracted, duplicate records were removed, and they were screened for the titles and abstracts to identify potentially eligible studies. Articles that were potentially eligible for inclusion were independently assessed for the review. Then, the investigators independently appraised the accuracy of the abstract and resolved any discrepancies by consensus.

Investigators independently extracted data about the number of hair dye poisoning individuals with suicidal intentions and clinical data that were previously mentioned.

Statistical analysis

Stata V.12.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all the statistical analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochran's Chi-square and quantified with the I2 statistic, which was considered to be low when it was 0.24%.[11] Considering heterogeneity across studies, a random effects model was used to calculate pooled data and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). DerSimonian and Laird method was used to calculate the pooled estimates of the random effects model. We performed subgroup analysis by gender type (male or female) to deal with heterogeneity. We combined the results of subgroups into a single group according to the formulae recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration.[12] In order to address the issue of heterogeneity among studies, a sensitivity analysis was performed between the studies carried out in different continents. Publication bias includes selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and another risk of bias which was assessed using the Begg's test and Egger's regression test. These tests were used to assay the possibility of publication bias, and significance was set at a P < 0.05.[13,14]

Results

Literature search and selection

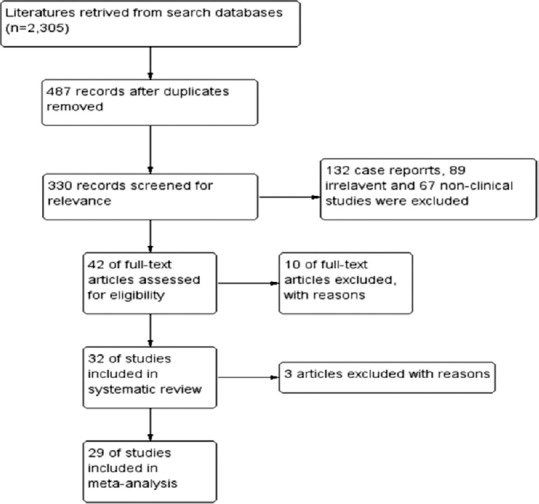

The search strategy identified 1430 records for potential inclusion of study [Figure 1]: PubMed (n = 85), Science Direct (n = 854), Embase (n = 36), and Google Scholar (n = 1330). After reviewing the abstracts, 42 full-text articles were assessed for further assessment of their eligibility [Appendix 2]. Finally, 32 studies were determined to be eligible for the systematic review[10,11,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] and 29 were included in the meta-analysis.[10,11,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,43,44] All the included studies contained 5,559 subjects covering 17 from India,[15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,45] Sudan,[6,31,32,33,34,35,36] Pakistan,[3,37,38,39] Egypt,[1,10] Morocco,[4,41,42,43,44] and Tunisia[1,11] Eighteen studies were conducted prospectively[10,15,16,17,19,20,23,24,25,27,30,31,32,37,38,42,43,45] and 14 retrospectively.[11,18,22,26,28,29,33,34,35,36,39,40,41,44] The study population was ranging from 9[30] to 1545.[25] Fourteen studies were carried out for ≤1-year duration[15,16,18,19,20,22,24,30,32,33,34,35,36,42] and 16 were for >1–10 years.[10,11,17,23,25,26,27,28,29,37,38,39,40,41,43,44] Two studies did not specify their study durations.[21,31]

Figure 1.

Flow of information

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 32 included studies are shown in Table 1. Among these, 4280 used PPD-containing hair dye with suicidal intentions,[10,11,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,33,34,35,38,41,43,44]192 were due to accidental poisoning,[10,11,24,25,28,33,34,35,37,38,41,43] and 9 studies (n = 1087) did not specify the reasons for hair dye poisoning.[15,16,17,18,23,31,32,36,39] Majority of the hair dye poisoning cases were female (n = 3904; 73.2%) when compared to male (n = 1431; 26.8%) with a sex ratio of 2.7:1 (odds ratio [OR] =0.13; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.12–0.15). However, in some studies, male patients were higher than females.[17,26,31,36]

Table 1.

Description of paraphenylenediamine-containing hair dye poisoning studies which are included in this systematic review and meta-analysis

| The study, author, year | Journal | Study location | Type of study | Period of study | Sample size | Study settings | Male: female | Mean or median age (years) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venkatasubbaiah et al., 2016[15] | Otolaryngol Online J | Kadapa, India | Prospective | 2014-2015 | 386 | Causality | 97:289 | - | Awareness in the rural areas regarding the complications caused by PPD poisoning |

| Tiwari et al., 2015[16] | Int J Med Sci Public Health | Gwalior, India | Prospective | 2008-2009 | 50 | Medical wards | 20:30 | - | Tracheostomy, endotracheal intubation with or without ventilation, and dialysis can decrease the mortality |

| Mohammed et al., 2015[32] | Eur J Pharm Med Res | Khartoum, Sudan | Prospective | 2013-2014 | 40 | ENT department | 2:38 | 27.2 | Identified cardiac rhabdomyolysis in PPD poisoning |

| Amarnath et al., 2015[17] | J Evolution Med Dent Sci | Tirupati, India | Prospective(2,931 of 4,342 patients) | 2009-2011 | 27 | Causality and ENT department | 18:9 | 50.5 | Emergency tracheostomy is a reliable method of restoring the airway in hair dye poisoning |

| Mahsud, 2015[38] | Gomal J Med Sci | Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan | Prospective | 2013-2015 | 38 | Emergency ward | 2:36 | 22.08±6.4 | PPD poisoning causing asphyxia and respiratory failure leading to death |

| Naqvi et al., 2015[39] | Open J Nephrol | Karachi, Pakistan | Prospective | 2010-2014 | 75 | Nephrology ward | - | 28.2±11.2 | PPD poisoning is a contributing factor for toxic rhabdomyolysis |

| Balasubramanian et al., 2014[18] | Ann Nigerian Med | Thoothukudi, India | Prospective | April-December 2010 | 125 | Intensive care unit | 39:86 | 24 | Time of hospital presentation is an important risk factor for oropharyngeal edema in hair dye poisoning |

| Shigidi et al., 2014[33] | Pan Afr Med J | Khartoum, Sudan | Prospective | 2012-2013 | 30 | Emergency | 2:28 | 25.6±4.2 | Hair dye poisoning patients with Acute 9kidney injury re10quired dialysis |

| Sugunakar et al., 2013[19] | J Evolution Med Dent Sci | Amalapuram, India | Retrospective | 2005-2006 | 18 | Hospital admission | 4:14 | - | PPD intoxication needed aggressive treatment support |

| Gella et al., 2013[20] | Int J Pharm PharmSci | Kadapa, India | Prospective | March-September 2011 | 419 | Intensive care unit and medical wards | 126:293 | - | Cardiorespiratory failure, myocarditis, and acute renal failure leading to death |

| Rebgui et al., 2013[41] | IOSR J Environment SciToxicol Food Tech | Rabat, Morocco | Retrospective | 1996-2007 | 102 | Poison control and drug monitoring center | 18:84 | 17.3±15.6 | PPD import and sales should be banned in Morocco |

| Gupta and Singh, 2013[21] | J Indian SocToxicol | Gwalior, India | Prospective | - | 36 | Hospital admissions | - | - | Emergency tracheostomy tends to decrease the mortality in PPD poisoning |

| Elgamel and Ahmed, 2013[34] | Sudan Med Monit | Khartoum, Sudan | Retrospective | June-December 2008 | 200 | ENT department | 39:161 | - | Emergency tracheostomy tends to decrease the mortality in PPD poisoning |

| Khuhro et al., 2012[40] | Anaesth Pain Intensive Care | Nawabshah, Pakistan | Prospective | 2009-2012 | 16 | Intensive care unit | 2:14 | 25.8±5.6 | PPD poisoning associated with high mortality |

| Nirmala and Ganesh, 2012[22] | Otolaryngol Online J | Thoothukudi, India | Retrospective | 2009-2010 | 108 | ENT department | 38:70 | 24.7±6.5 | Needed public awareness of hair dye |

| Osman et al., 2012[35] | Gazira J Health Sci | Gezira, Sudan | Retrospective | 2006-2007 | 55 | Renal diseases and surgery | 2:53 | - | Hair dye poisoning containing PPD is the main causative factor of ARF |

| Kindle et al., 2012[23] | ISRN Emergency Med | Nellore, India | Retrospective | 2008-2011 | 50 | Emergency ward | 9:41 | 23±7.8 | Supervasmol-33 is an emerging alternative to organophosphorus poisoning. |

| Radhika et al., 2012[24] | J Biosci Tech | Kadapa, India | Prospective | January-April 2010 | 264 | Causality ward | 93:171 | - | Banning hair dyes in some parts of India |

| Jain et al., 2012[25] | J Toxicol Environ Health Sci | Jhansi, India | Prospective | 2000-2011 | 1595 | Medicine department | 381:1214 | - | Myocarditis is a fatal complication due to ingestion of PPD-20-containing hair dye with >10 grams of dose |

| Sandeep Reddy et al., 2012[26] | Renal Fail | Tirupati, India | Prospective | 2007-2011 | 81 | Hospital admissions | 43:38 | - | Acute kidney injury testifies the severity of intoxication and poor prognosis |

| Prasad et al., 2011[27]* | J ClinDiagnos Res | Tirupati, India | Retrospective | 2008-2010 | 81 | Emergency | - | - | Biochemical changes are the cornerstone for early diagnosis of hair dye poisoning complications |

| Jain et al., 2011[28] | J Assoc Physicians India | Jhansi, India | Prospective | 2004-2009 | 1020 | Medicine department | 286:734 | - | Early therapeutic intervention is essential for PPD hair dye poisoning |

| Charra et al., 2011[42]* | Int J Clin Med | Casablanca, Morocco | Prospective | 2010 | 21 | Intensive care unit | 4:17 | 20 | Inflammatory stress, pro-inflammatory power, and immunomodulative actions were causing cytotoxicity in hair dye poisoning patients |

| Chrispal et al., 2010[29] | Trop Doctor | Vellore, India | Retrospective | 2006-2009 | 13 | Hospital admissions | 2:11 | 27.2±8.7 | Early referral and aggressive management could reduce the mortality |

| Shalaby et al., 2010[10] | Toxicol Ind Health | Cairo, Egypt | Retrospective | 2001-2008 | 25 | Poison control center | 7:18 | 35±10.5 | Early recognition of complications and prompt treatment are necessary for successful outcome |

| Murugan and Bairagi, 2010[30]* | J Indian SocToxicol | Karaikal, India | Retrospective | 2008-2009 | 9 | Hospital deaths | 0:9 | Female gender aged between 20 and 30 years was risk for suicidal exposure | |

| Sahay et al., 2009[31] | J Assoc Physician India | Hyderabad, India | Prospective | - | 30 | Nephrology | 24:6 | 26.9±4.9 | Hair dye poisoning is an important cause of acute renal failure and required respiratory and hemodynamic support for recovery |

| Kaballo et al., 2007[36] | Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant | Khartoum, Sudan | Retrospective | 2003-2004 | 89 | Nephrology | 57:32 | 39±19.4 | Acute tubular necrosis was associated with PPD poisoning |

| Filali et al., 2006[43] | Afr J Trad CAM | Rabat, Morocco | Retrospective | 1992-2002 | 374 | Poison control center | 86:288 | - | PPD poisoning has serious consequences which may eventually lead to death. |

| Kallel et al., 2005[11] | J Nephrol | Sfax, Tunisia | Retrospective | 1994-2000 | 19 | Intensive care unit | - | 27.9±16.8 | PPD intoxication was associated with respiratory, muscular, renal moreover, hemodynamic syndromes |

| Fatihi el et al., 1997[44] | Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant | Casablanca, Morocco | Prospective | 1984-1994 | 13 | Nephrology | - | - | PPD can cause rhabdomyolysis |

| Suliman et al., 1995[37] | Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant | Khartoum, Sudan | Retrospective | 1983-1993 | 150 | Hospital admissions | 30:120 | 40 | PPD poisoning causes severe side effect on oral ingestion |

The systematic review includes 32 studies, n=5559; meta-analysis - 29 studies, n=5448; *Studies excluded from the meta-analysis. PPD=Paraphenylenediamine, ENT=Ear, nose, and throat, ARF=Acute renal failure

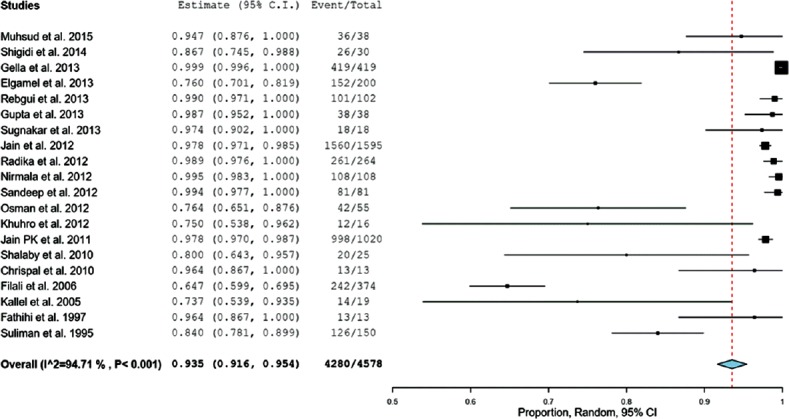

Ingestion of paraphenylenediamine-containing hair dye with suicidal intentions

We identified a total of 20 studies that described the proportion of the population which ingested PPD-containing hair dye as a suicidal solution (OR = 93.5%; 95% CI = 91.65–95.42) [Figure 2]. The pooled prevalence of suicidal intentions proportion was 4.9% (95% CI = 4.54–5.33) with an overall mortality rate of 14.5% (95% CI = 11.1–17.9).

Figure 2.

Ingestion of paraphenylenediamine-containing hair dye with suicidal intentions

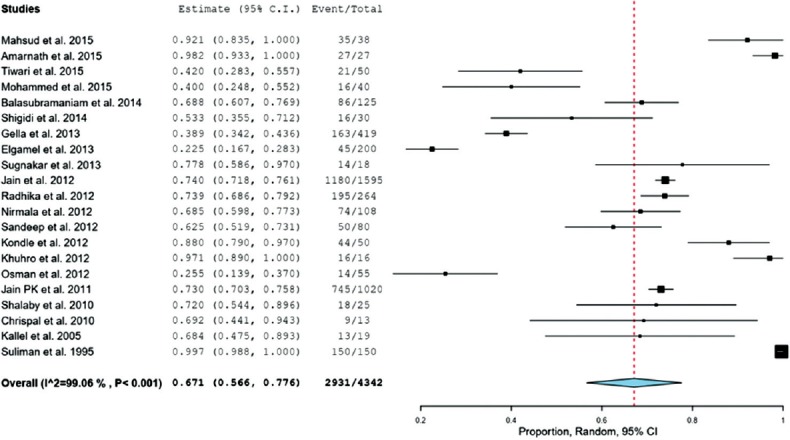

Angioneurotic edema in hair dye ingested patients

Twenty-one studies reported the individuals who developed angioneurotic edema or cervicofacial edema. Overall, angioneurotic edema was observed in 67.1% (95% CI=56.6-77.6%, P < 0.001) of the patients ingested PPD-containing hair dye (2,931 of 4,342 patients), respectively [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Cervicofacial edema–angioneurotic edema in hair dye ingested patients

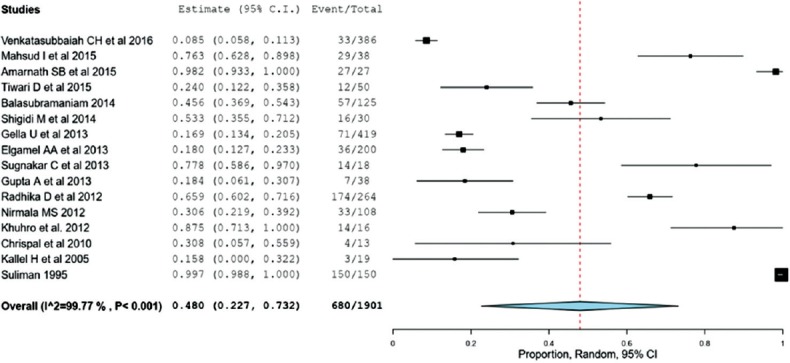

The effectiveness of tracheostomy intervention

Sixteen studies comprising 1,901 patients were included in the analysis of tracheostomy intervention in PPD-containing hair dye poisoning [Figure 4]. The tracheostomy intervention was considered in 47.9% (680 of 1901 patients; 95% CI = 22.7–73.2; P < 0.001) with heterogeneity I2= 99.7%.

Figure 4.

Analysis of tracheotomy intervention in paraphenylenediamine-containing hair dye poisoning

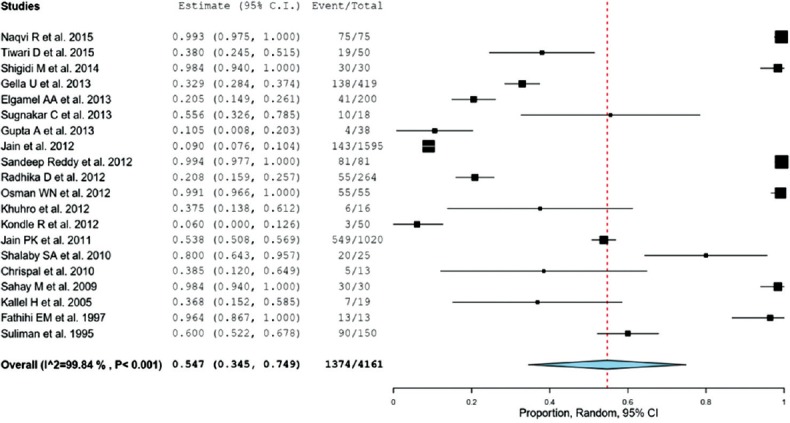

The occurrence of acute renal failure

Twenty studies comprising 4,161 patients provided data on ARF [Figure 5]. PPD-containing hair dye poisoning resulted significantly increased the risk of ARF found in 54.7% (n = 1374) patients (95% CI = 34.5–74.9; P < 0.001) with heterogeneity I2= 99.8%.

Figure 5.

Occurrence of acute renal failure in hair dye poisoning patients

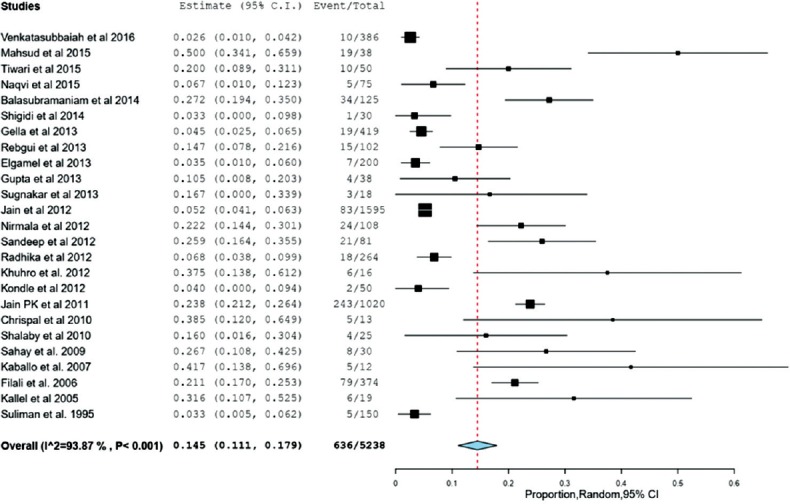

Hair dye intoxication mortality

We identified a total of 25 studies comprising 5,238 patients were included in the analysis of hair dye intoxication mortality. There was a statistically significant mortality rates noticed with hair dye intoxication; the respective intoxication mortality rates were 14.5% (636 of 5,238 patients); 95% CI = 11.1–17.8; P < 0.001; heterogeneity I2= 93.8%, [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Analysis of hair dye intoxication mortality

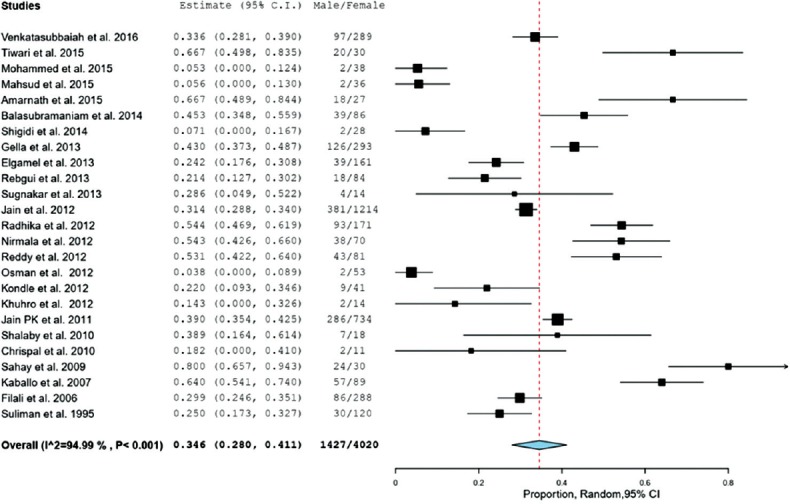

Sub-group analysis

To investigate the potential discrepancy, we divided subgroups by gender using a random model. The results of 25 studies were stratified by their gender (male versus female) about hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions. Overall, the percentage of hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions was 3.46 times (95% CI = 28–41.1%) higher in females than males [Figure 7]. Indeed, in the subgroup analysis, the percentage of ingested hair dye females with suicidal intentions was 73.8% (95% CI = 67.7–77.4), more than double to that of males 26.2% (95% CI = 22.6–32.3), with heterogeneity I2= 93.4%.

Figure 7.

Gender differences in hair dye poisoning patients

Sensitivity analysis stratified for different continents

Sensitivity analysis was carried out where the studies were conducted from different continents concerning “suicidal intentions” and “mortality” in hair dye poisoning samples. Studies carried out in Asia and Africa highlighted 94.6% (95% CI = 92.5–96.7) and 82.9% (95% CI = 70.6–95.3) of the samples, respectively, who ingested hair dye with suicidal intentions. Further, studies carried out in Africa (seven studies) showed higher mortality of 15.1% (95% CI = 6.56–23.7) than the Asians (18 studies) 14.3% (95% CI = 10.5–18.1).

Publication bias

Nine studies do not report the type of poisoning (suicidal or accidental) and early-stage symptoms (cervicofacial edema or angioneurotic edema), and eleven studies do not report the type of interventions used for clinical management and also do not report the late-phase complications (ARF). Three studies included another type of poisoning patients. Begg's test and Egger's test showed the existence of publication bias (P = 0.026) [Appendix 3].

Discussion

In recent years, there are an increasing number of epidemiological studies about hair dye poisoning (PPD) in developing countries. It is now possible to obtain direct evidence of hair dye poisoning situation in adults with suicidal intentions. Through a systematic review, we gathered different studies published from the inception to January 2016 to estimate the prevalence, complications, interventions, and mortality associated with hair dye poisoning in developing countries. Previous reviews focused on clinical manifestations and treatment modalities for hair dye poisoning,[6] in vivo toxicokinetic profile and safety of hair dyes in industrialized countries,[2] and PPD poisoning in children.[46]

Our investigation included 29 articles with a total of 5,559 subjects, covering different locations among six developing countries which guaranteed the reliability of this meta-analysis. The analysis conducted on eight different outcomes showed exciting results. Overall, the pooled prevalence proportion of PPD-containing hair dye poisoning was 4.9% (95% CI = 4.54–5.33) among individuals with suicidal intentions with a sex ratio of 1:2.7. However, >90% of the samples ingested hair dye with suicidal intentions. Several studies have reported the reasons for using hair dye agents for deliberate self-poisoning due to their low prices, high availability, and easy availability to obtain without raising suspicions.[7,10,23] Indeed, the PPD concentration in hair dyes also ranges from 2% to 90% that can increase the multisystem toxicity on oral ingestion.[3,47,48] These findings pointed out the lack of regulations of cosmetic ingredients and misuse of hair dyes among the general public in developing countries.

The present study found that the pooled proportion of early-stage clinical manifestations such as oropharyngeal edema, cervicofacial edema, and angioneurotic edema was noticed in 67.1% of the hair dye poisoning patients. Our findings were considerably less than those of previous studies. In Jain et al. study, the proportion of severe face and neck edema was 73%[28] and it was 79% in Kallel et al. study,[11] and in Suliman et al. study, all the patients studied had developed angioneurotic edema.[37] Several studies cited the reason for the occurrence of angioneurotic edema and its association with PPD in the hair dyes.[11,37,38,43] PPD is a standard chemical allergen and has corrosive properties.[49] Performing gastric lavage to detoxification may increase the risk of airway obstruction leading to cause severe angioneurotic edema and respiratory distress. However, early administration of nasogastric tube or endotracheal tube compared to gastric lavage needed further investigation.

The current study also revealed the effect of emergency tracheostomy in hair dye ingested patients with severe respiratory distress. Nearly half (48%) of the pooled samples studied underwent emergency tracheostomy surgical procedure as a supportive intervention. In a Pakistan study, a significant number of deaths in the tracheostomy group (10/29) was comparably lower than those without tracheostomy (5/9).[38] This indicated emergency tracheostomy deemed to have a significant role in improving the hair dye ingested patient outcomes. However, none of the studies has tried cricothyroidotomy procedures or other surgical interventional procedures, which need to be explored further.

Late-stage complications such as ARF (oliguria, anuria, rhabdomyolysis, and renal tubular necrosis) in PPD-containing hair dye poisoning patients were characterized by chocolate brown-colored urine and were associated with tubular obstruction by myoglobin casts causing renal failure. The proportion of ARF was 55% in the pooled samples, and this proportion is consistent with Jain et al. study conducted on 1595 hair dye poisoning (PPD) patients[25] but lower than Naqvi et al. study conducted on acute kidney injury (AKI) patients caused by PPD toxins attending tertiary renal care center in Pakistan for a period of 25 years.[9] However, these results, which may play a role in effective management of ARF, needed hemodialysis to improve the survival and close monitoring of methemoglobin and myoglobin concentrations in urine which can serve as potential biomarkers of ARF in hair dye poisoning patients.

Whereas mortality was frequently reported across studies, fewer studies reported data within the first 5 h of admission and soon after gastric lavage. Filali et al. retrospectively studied a large number of PPD systemic poisoning patients for over ten years and demonstrated a mortality rate of 21%.[43] Further, data were obtained from a cross-sectional study in which the mortality rate (27%) provided a more definitive answer regarding the effect of systemic toxicity of PPD on hair dye poisoning patients.[18] No single study evaluating the effect of interventions has yet been powered to reduce mortality and adverse events, but our meta-analysis of 5,238 patients with suicidal intentions found in 14.4% of hair dye poisoning death. It should be noted. However, the patient population differ.

Besides, the subgroup analysis demonstrated that a large part of the female population ingested hair dye with suicidal intentions. This practice makes it challenging to address the control of using household products as a suicidal agent. This phenomenon of using hair dye as a suicidal agent is particularly alarming in developing countries such as India, Sudan, Pakistan, and Morocco. Therefore, it is essential to implement awareness about interventions to curtail the misuse of hair dyes and restrict the sale of hair dyes with high PPD concentrations. Further, the mortality associated with hair dye poisoning has not shown much difference between the continents. The study highlights the need for strict evaluation of PPD concentrations in hair dyes and revises the cosmetic regulations in developing countries. Further, responsible cosmetic industries should focus on identifying alternative for PPD use in hair dye. Because of no known antidote for hair dye poisoning, it is necessary to conduct further research on this topic to identify potential antidote and effective interventions to formulate treatment guidelines.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, there was high heterogeneity noticed among the studies analyzed, with a consequent lack of homogeneity of the outcomes, so we used a random effect model to tackle this problem. The heterogeneity was still high within subgroups, which might be influenced by factors such as geographical, racial, cultural, social diversity, and economic differences among the nations in which the studies were conducted. Second, the presence of publication bias such as incomplete data, reporting biases, and performance biases was noticed in the included studies used retrospective designs. This publication bias might lead to overestimate the pooled effect size of the included studies. Furthermore, there are geographic differences in outcomes that need further investigations with more intensive randomized controlled trials and cohort studies.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of PPD-containing hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions in developing countries was 4.9% with a pooled percentage of 93.5%. The results indicate that hair dye poisoning with suicidal intentions has a higher proportion of clinical morbidity and mortality. The rate of using hair dye with suicidal intentions was comparatively higher in females than males (2.7:1). This meta-analysis revealed an alarming hair poisoning situation in developing countries in recent decades and provided robust evidence for policy making to curtail emerging hair dye poisoning in developing countries.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix 1

PRISMA 2009 checklist

| Section/topic | # | Checklist item | Reported on page# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number | 2 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | 4 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) | 5 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number | 5 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale | 6 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched | 6 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated | 6 |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis) | 6 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators | 6 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made | 7 |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | 7 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means) | 7 |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., I2) for each meta-analysis | 7 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | 7 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | 7 |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | 8 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations | 8 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12) | 8 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) Simple summary data for each intervention group (b) Effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot | 9 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency | 9 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15) | 10 |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see item 16]) | 10 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy makers) | 11 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review-level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias) | 14 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research | 14 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review | 14 |

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097. For more information, visit: www.prisma-statement.org

Appendix 2

Excluded articles with reason

Hooff GP, van Huizen NA, Meesters RJ, Zijlstra EE, Abdelraheem M, Abdelraheem W, et al. Analytical investigations of toxic p-phenylenediamine (PPD) levels in clinical urine samples with special focus on MALDI-MS/MS. PLoS One 2011;6:e22191.

Hamdouk M, Abdelraheem M, Taha A, Cristina D, Checherita IA, Alexandru C, et al. The association between prolonged occupational exposure to paraphenylenediamine (hair-dye) and renal impairment. Arab J Nephrol Transplant 2011;4:21-5.

Jain PK, Agarwal N, Sharma AK, Akhtar A. A prospective study of ingestional hair dye poisoning in Northern India (Prohina). J Clin Med Res 2011;3:9-19.

Derkaoui A, Labib S, Elbouazzaoui A, Achour S, Sbai H, Harrandou M, et al. Paraphenylenediamine poisoning in Morocco: Report of 24 cases. Pan Afr Med J 2011;8:19.

AlGhamdi KM, Moussa NA. Knowledge and practices of, and attitudes towards, the use of hair dyes among females visiting a teaching hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2011;31:613-9.

Ababou A, Ababou K, Mosadik A, Lazreq C, Sbihi A. Myocardial rhabdomyolysis following paraphenylene diamine poisoning. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2000;19:105-7.

Mathur AK, Gupta BN, Narang S, Singh S, Mathur N, Singh A, et al. Biochemical and histopathological changes following dermal exposure to paraphenylene diamine in guinea pigs. J Appl Toxicol 1990;10:383-6.

Mustafa OM. Acute poisoning with hair dye containing paraphenylene diamine: The Gazira experience. J Arab Board Specialization 2001;3.

Sir Hashim M, Hamza YO, Yahia B, Khogali FM, Sulieman GI. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr 1992;12:3-6.

Abdelraheem MB, El-Tigani MA, Hassan EG, Ali MA, Mohamed IA, Nazik AE, et al. Acute renal failure owing to paraphenylene diamine hair dye poisoning in Sudanese children. Ann Trop Paediatr 2009;29:191-6.

Reasons for excluding in Meta-analysis

Prasad NR, Bitla ARR, Manohar SM, Devi HN, Rao PVLN. A retrospective study on the biochemical profile of self poisoning with a popular Indian hair dye. J Clin Diagn Res 2011;5 Suppl 2:1343-6.

Charra B, Hachimi A, Benslama A, Habti N, Farouqu B, Motaouakkil S. Immunological manifestations in paraphenylene diamine poisoning. Int J Clin Med 2011;2:435-8.

Murugan M, Bairagi KK. Incidence of suicides by poisoning with a popular Indian brand of hair dye. J Indian Soc Toxicol 2010;6:40-1.

Appendix 3: Funnel plot showing risk of bias

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Suicide. [Last accessed on 2016 Mar 28]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs398/en.html .

- 2.Nohynek GJ, Antignac E, Re T, Toutain H. Safety assessment of personal care products/cosmetics and their ingredients. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;243:239–59. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain PK, Agarwal N, Sharma AK, Akhtar A. Prospective study of ingestional hair dye poisoning in Northern India (Prohina) J Clin Med Res. 2011;3:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goebel C, Diepgen TL, Krasteva M, Schlatter H, Nicolas JF, Blömeke B, et al. Quantitative risk assessment for skin sensitisation: Consideration of a simplified approach for hair dye ingredients. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;64:459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yazar K, Boman A, Lidén C. P-phenylenediamine and other hair dye sensitizers in Spain. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.01979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sampathkumar K, Yesudas S. Hair dye poisoning and the developing world. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2009;2:129–31. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.50749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelraheem MB, El-Tigani MA, Hassan EG, Ali MA, Mohamed IA, Nazik AE. Acute renal failure owing to paraphenylene diamine hair dye poisoning in Sudanese children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2009;29:191–6. doi: 10.1179/027249309X12467994693815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naqvi R, Akhtar F, Farooq U, Ashraf S, Rizvi SA. From diamonds to black stone; myth to reality: Acute kidney injury with paraphenylene diamine poisoning. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015;20:887–91. doi: 10.1111/nep.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derkaoui A, Labib S, Elbouazzaoui A, Achour S, Sbai H, Harrandou M, et al. Paraphenylenediamine poisoning in Morocco: Report of 24 cases. Pan Afr Med J. 2011;8:19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shalaby SA, Elmasry MK, Abd-Elrahman AE, Abd-Elkarim MA, Abd-Elhaleem ZA. Clinical profile of acute paraphenylenediamine intoxication in Egypt. Toxicol Ind Health. 2010;26:81–7. doi: 10.1177/0748233709360200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kallel H, Chelly H, Dammak H, Bahloul M, Ksibi H, Hamida CB, et al. Clinical manifestations of systemic paraphenylene diamine intoxication. J Nephrol. 2005;18:308–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Deeks JJ. Selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 510th ed. Chichester: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2017. [Last accessed on 2017 May 21]. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beynon R, Leeflang MM, McDonald S, Eisinga A, Mitchell RL, Whiting P, et al. Search strategies to identify diagnostic accuracy studies in MEDLINE and EMBASE. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:MR000022. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000022.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatasubbaiah CH, Sreenivasulu G, Sukumar S, Sudhindra G. Supervasmol poisoning-study in RIMS, Kadapa. Otolaryngol Online J. 2016;6:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiwari D, Jatav OP, Dudani M. Prospective study of clinical profile in hair dye poisoning (PPD) with special reference to electrocardiographic manifestation. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2016;5:1313–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amarnath SB, Chandrasekhar V, Sreenivas G, Deviprasad S, Tagore VR, Priyanka G. Emergency tracheostomy: Our experience. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2015;4:7652–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balasubramanian D, Subramanian S, Shanmugam K. Clinical profile and mortality determinants in hair dye poisoning. Ann Niger Med. 2014;8:82–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6966.3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sugunakar C, Appaji SK, Malakondaiah M. An analysis of the trend of rising in poisoning due to hair dye brand (Supervasmol 33 Kesh Kala) J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2013;2:9833–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gella U, Shilpa N, Chandrababu S, Shyam MR, Subbiah VM. A prospective study on the prevalence of poisoning cases- focus on vasmol poisoning. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5(Suppl 4):405–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta A, Singh N. A prospective study of 36 cases of systemic poisoning due to hair dye ingestion treated in a tertiary care hospital. J Indian Soc Toxicol. 2013;9:41–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nirmala MS, Ganesh R. Hair dye- an emerging suicidal agent: Our experience. Otolaryngol Online J. 2012;2:3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kindle R, Pathapati RM, Saginela SK, Malliboina S, Makineedi VP. Clinical profile and outcome of hair dye poisoning in a teaching hospital in Nellore. ISRN Emerg Med. 2012:624253. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radhika D, Mohan KV, Sreenivasulu M, Reddy YS, Karthik TS. Hair dye poisoning – A clinicopathological approach and review. J Biosci Technol. 2012;3:492–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain PK, Kumar SA, Navnit A, Sengar NS, Zaki SM, Kumar SA, et al. A prospective clinical study of myocardiitis in cases of paraphenylenediamine (hair dye) poisoning in Northern India. J Toxicol Environ Health Sci. 2012;4:106–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandeep Reddy Y, Abbdul Nabi S, Apparao C, Srilatha C, Manjusha Y, Sri Ram Naveen P, et al. Hair dye related acute kidney injury – A clinical and experimental study. Ren Fail. 2012;34:880–4. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2012.687346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad NR, Bitls AR, Manohar SM, Devi NH, Rao PV. A retrospective study on the biochemical profile of self-poisoning with popular Indian hair dye. J Clin Diagnos Res. 2011;5:1343–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain PK, Agarwal N, Kumar P, Sengar NS, Agarwal N, Akhtar A. Hair dye poisoning in Bundelkhand region (prospective analysis of hair dye poisoning cases presented in department of medicine, MLB medical college, Jhansi) J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:415–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chrispal A, Begum A, Ramya I, Zachariah A. Hair dye poisoning – An emerging problem in the tropics: An experience from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Trop Doct. 2010;40:100–3. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.090367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murugan M, Bairagi KK. Incidence of suicides by poisoning with a popular Indian brand of hair dye. J Indian Soc Toxicol. 2010;6:40–1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahay M, Vani R, Vali S. Hair dye ingestion- an uncommon cause of acute renal injury. J Assoc Phys India. 2009;57:743–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammed AA, Elkablawy MA, Abdelgodoos H, Albasri A, Adam I. Cardiac and hepatic toxicity in paraphenylenediamine (hair dye) poisoning among Sudanese. Eur J Pharm Med Res. 2015;2:100–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shigidi M, Mohammed O, Ibrahim M, Taha E. Clinical presentation, treatment and outcomes of paraphenylene-diamine induced acute kidney injury following hair dye poisoning: A cohort study. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:163. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.163.3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elgamel AA, Ahmed NO. Complications and management of hair dye poisoning in Khartoum. Sudan Med Monit. 2013;8:146–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osman WN, Elhaj AS, Elmustafa OM, Taha MS, Ahmad MI. Hair dye poisoning: An important aetiological factor in acute renal failure in Gezira, Sudan. Gazira J Health Sci. 2012;8:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaballo BG, Khogali MS, Khalifa EH, Khaiii EA, Ei-Hassan AM, Abu-Aisha H. Patterns of “severe acute renal failure” in a referral center in Sudan: Excluding intensive care and major surgery patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2007;18:220–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suliman SM, Fadlalla M, Nasr Mel M, Beliela MH, Fesseha S, Babiker M, et al. Poisoning with hair-dye containing paraphenylene diamine: Ten years experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 1995;6:286–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahsud I. Role of tracheostomy in reducing mortality from Kala Pathar (Paraphenylenediamine) poisoning. Gomal J Med Sci. 2015;13:170–2. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naqvi R, Akhtar F, Ahmed E, Naqvi A, Rizvi A. Acute kidney injury with rhabdomyolysis: 25 years experience from a tertiary care center. Open J Nephrol. 2015;5:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khuhro BA, Khashheli MS, Shaikh AA. Paraphenylenediamine poisoning: Our experience at PMC hospital Nawabshah. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2012;16:243–6. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rebgui H, Hami H, Ouammi L, Soulaymani A, Soulaymani-Bencheikh R, Mokhtari A. Epidemiological profile of acute intoxication with para-phenylenediamine (occidental TAKAWT) in the oriental region in Morocco: 1996-2007. IOSR J Environ Sci Toxicol Food Tech. 2013;4:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charra B, Hachimi A, Benslama A, Habti N, Farouqu B, Motaouakkil S. Immunological manifestation of paraphenylenediamine poisoning. Int J Clin Med. 2011;2:435–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Filali A, Semlali I, Ottaviano V, Furnari C, Corradini D, Soulaymani R. A retrospective study of acute systemic poisoning of paraphenylene (occidental TAKAWT) in Morocco. Afr J Trad CAM. 2006;3:142–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fatihi el M, Ramdani B, Benghanem MG, Hachim K, Zaid D. Rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure secondary to toxic material abuse in Morocco. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 1997;8:131–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viechtbauer W. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments. Psychometrika. 2007;72:269–71. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdelraheem M, Hamdouk M, Zijlstra EE. Review: Paraphenylenediamine (hair dye) poisoning in children. Arab J Nephrol Transplant. 2010;3:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Praveen Kumar AS, Talari K, Dutta TK. Super vasomolhair dye poisoning. Toxicol Int. 2012;19:77–8. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.94503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sir Hashim M, Hamza YO, Yahia B, Khogali FM, Sulieman GI. Poisoning from henna dye and para-phenylenediamine mixtures in children in Khartoum. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1992;12:3–6. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1992.11747539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.p-Phenylenediamine. [Last accessed on 2019 Apr 07]. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.gov/compound/p-Phenylenediamine.html .