Abstract

Background

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy (CBCT) is part of standard treatment of several cancers. In testicular cancer (TC) survivors, an increased risk of developing metabolic syndrome (MetS) is observed. In this epigenome-wide association study, we investigated if CBCT relates to epigenetic changes (DNA methylation) and if epigenetic changes render individuals susceptible for developing MetS later in life. We analyzed methylation profiles, using the MethylationEPIC BeadChip, in samples collected ~ 16 years after treatment from 279 Norwegian TC survivors with known MetS status. Among the CBCT treated (n = 176) and non-treated (n = 103), 61 and 34 developed MetS, respectively. We used two linear regression models to identify if (i) CBCT results in epigenetic changes and (ii) epigenetic changes play a role in development of MetS. Then we investigated if these changes in (i) and (ii) links to genes, functional networks, and pathways related to MetS symptoms.

Results

We identified 35 sites that were differentially methylated when comparing CBCT treated and untreated TC survivors. The PTK6–RAS–MAPk pathway was significantly enriched with these sites and infers a gene network of 13 genes with CACNA1D (involved in insulin release) as a network hub. We found nominal MetS-associations and a functional gene network with ABCG1 and NCF2 as network hubs.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that CBCT has long-term effects on the epigenome. We could not directly link the CBCT effects to the risk of developing MetS. Nevertheless, since we identified differential methylation occurring in genes associated with conditions pertaining to MetS, we hypothesize that epigenomic changes may also play a role in the development of MetS in TC survivors. Further studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

Keywords: Cisplatin-based chemotherapy, Platinum, DNA methylation, Metabolic syndrome, Testicular cancer survivors, Epigenome-wide association study, Long-term effects, Epigenetic

Background

After the introduction of cisplatin in the treatment of testicular cancer (TC) in the late 1970s [1], this malignancy has become a model for curative treatment even in case of metastatic disease. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy (CBCT) has been integrated into standard treatment of several cancers in addition to TC, including gynecological, lung, bladder, and head and neck cancer [2]. For men with metastatic TC, three to four cycles of cisplatin in combination with etoposide and bleomycin (BEP) comprise the cornerstone in the treatment of metastatic disease [3], yielding 5-year disease-specific survival rates > 90% [4].

Due to the excellent prognosis and young age at diagnosis, TC survivors can expect to live for 30–50 years after successful treatment [5]. However, the very long-term relative survival among TC survivors is lower than among the age-matched population [6], primarily related to increased risks of second cancers and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [5]. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a well described late effect after TC treatment and is a possible mediator of both the increased risk of second cancers as well as CVD [7–9]. The prevalence of MetS in the general population differs according to MetS definition and increases by age, affecting about 20–25% of most Western populations [10, 11]. MetS including hypertension, increased body mass index (BMI), pre-diabetic biochemical serum changes, and/or hyperlipidemia is a constellation of risk factors for CVD [12]. An increased age-adjusted odds ratio (OR) for developing MetS after CBCT has been found when compared with patients treated with only surgery [9, 13, 14], although these results are not quite consistent [15].

Cisplatin exposure has been shown to result in drug-induced DNA hypermethylation both in vitro and in vivo [16–19]. In recent years, evidence for epigenetic changes predisposing to MetS has also been documented [20–22]; it is therefore plausible that these changes caused by CBCT could be involved in the development of MetS. Identification of differential DNA methylation (DNAm) in TC survivors that develop MetS compared to those who do not could provide a better understanding for the underlying mechanisms behind this serious late effect.

We hypothesize that epigenetic changes caused by CBCT render TC survivors susceptible for developing MetS later in life. The aim of this study was to (i) evaluate the potential long-term effect of CBCT on the epigenome in a cohort of Norwegian TC survivors, and (ii) identify possible associations between epigenetic changes and development of MetS. We also investigated if these changes in (i) and (ii) links to genes, functional networks, and pathways related to MetS symptoms.

Results

The basic characteristics of the TC survivors are outlined in Table 1. Median age at diagnosis ranged between 27 and 30 years, while median age at SII ranged between 47 and 51 years. Mean β methylation was 0.62 in all four groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics at diagnosis and follow-up for patients (N = 279), split by treatment group. Median values and range are reported for the groups

| CBCT+a MetS+b | CBCT− MetS+ | CBCT+ MetS− | CBCT− MetS− | CBCT model p value | MetS model p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 61 | 34 (32c) | 115 | 69 | ||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 30 (18–52) | 30 (16–49) | 27 (16–47) | 28 (18–52) | 0.09 | < 0.001 |

| Age at sample collection (years) | 48 (29–64) | 45 (28–74) | 44 (23–61) | 43 (26–62) | 0.81 | < 0.001 |

| Age at survey II (years) | 51 (36–69) | 52 (36–68) | 47 (31–66) | 48 (33–68) | 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| Time between surgery and sample collection (years) | 17 (5–27) | 18 (6–35) | 17 (6–28) | 14 (5–28) | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Time between sample collection and MetS diagnosis (years) | 0 (0–9) | 8 (− 8–9) | 0 (0–9) | 8 (0–9) | <0.001 | 0.09 |

| Clinical characteristics at diagnosis | ||||||

| Initial disease stage | < 0.001 | 0.58 | ||||

| I | 18 | 32 | 35 | 66 | ||

| IMK positived/II | 36 | 0 | 58 | 3e | ||

| III | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| IV | 5 | 0 | 18 | 0 | ||

| Histology | 0.16 | 0.15 | ||||

| Seminoma | 8 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Non-seminoma | 53 | 31 | 109 | 67 | ||

| Cumulative cisplatin dose (mg) | 790 (570–920) | 760 (495–1400) | < 0.001 | |||

| Selected characteristics at follow-up | ||||||

| Testosterone (nmol/L)f | 11.1 (3–26) | 12 (3–24) | 15 (3–32) | 16 (6–38) | 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| Physical activity | 0.40 | 0.002 | ||||

| Very active | 26 | 12 | 72 | 36 | ||

| Moderate | 25 | 16 | 37 | 28 | ||

| Sedentary | 10 | 4 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Smoking status | 0.77 | 0.13 | ||||

| Never smoker (%) | 43 | 33 | 51 | 49 | ||

| Former smoker (%) | 34 | 42 | 24 | 28 | ||

| Current smoker (%) | 23 | 24 | 24 | 23 | ||

| Mean β methylation | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.71 |

aCBCT cisplatin-based chemotherapy

bMetS metabolic syndrome

cN passed array filter quality

dIMK marker positive

eRendered tumor free by surgery alone

fRegression analysis showed that testosterone level is (on average) 4.2 nmol/L lower in groups 1 and 2 (MetS+) compared with groups 3 and 4 (MetS−) when adjusted for age (p = 1.6 E-07)

Study confounders

Principal component analyses of the DNAm did not show differences between the four groups (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Global methylation was not associated with CBCT or MetS (p > 0.05) (Additional file 1: Figure S2). However, we identified associations between CBCT and relative proportions of CD4+ T cells (p = 0.0001), and CD8+ T cells (p = 0.04). Testosterone was also significantly associated with MetS (p = 1.6 E-07). We found 3109 Bonferroni significant CpGs (cytosine nucleotide followed by a guanine nucletide) (p value < 0.01) associated with age and 229 Bonferroni significant CpGs (p value < 0.01) associated with smoking habits, including two smoking related genes (Additional file 1: Figure S3) (Fig. 1).

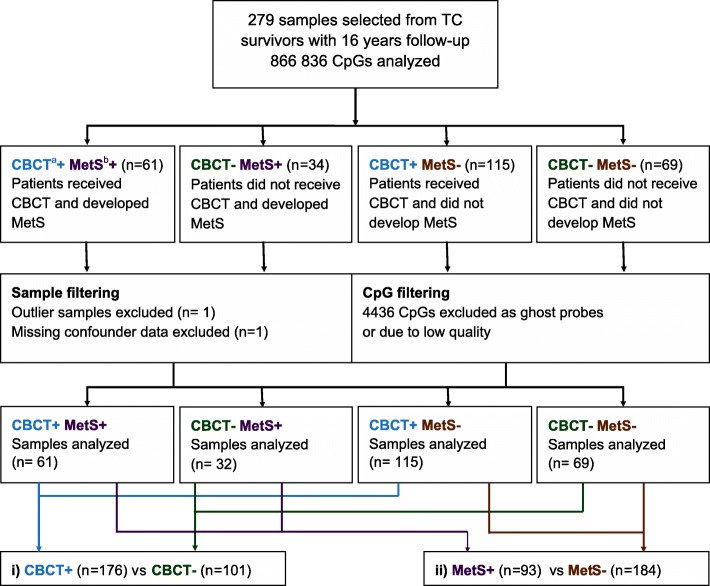

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of included samples that were analyzed with the MethylationEPIC BeadChip (n = 279). Samples were from testicular cancer survivors divided into four groups according to CBCT and MetS status. a CBCT cisplatin-based chemotherapy. b MetS metabolic syndrome

Long-term effects of cisplatin on DNA methylation

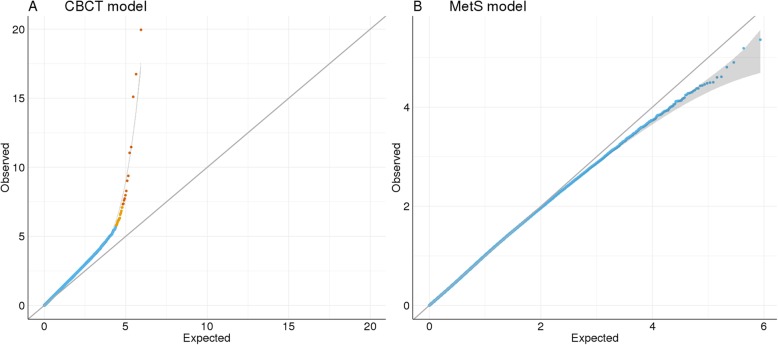

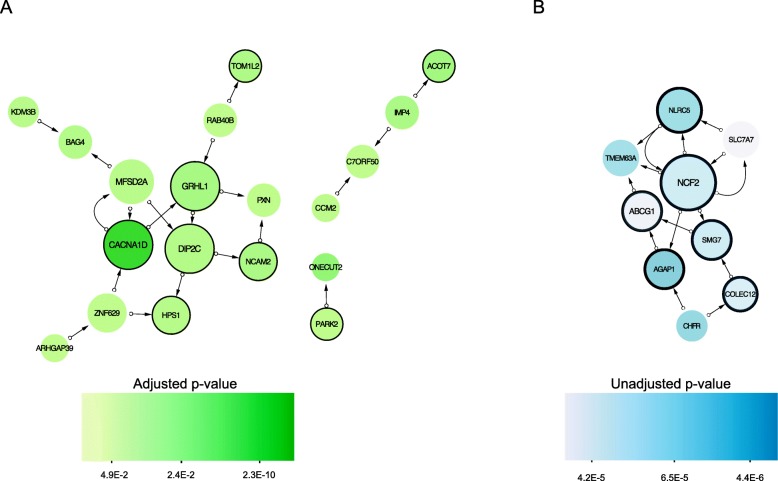

After adjusting for age, testosterone, smoking, and cell count, 35 CpG sites were associated with CBCT after False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (Table 2). Of these, 13 CpG sites were significantly associated with CBCT after Bonferroni correction (Fig. 2a). Of the FDR-associated CpGs, 21 were located in Open Sea, three in a CpG island, and 11 in either CpG island shelf or shore. The different multivariate models showed similar results (Additional file 1: Figure S4B and Figure S5B). Nineteen annotated CBCT genes were found in the GENIUS database. One network-structure was identified for 13 genes, of which six were related to MetS. Each node had an average of 2.0 neighbors. CACNA1D, DIP2C, and GRHL1 had the highest network degrees and were all associated with MetS (Fig. 3a).

Table 2.

Annotations for the 35 FDR significant CpGs (adjusted p values < 0.05) for cisplatin-based chemotherapy (CBCT) model

| CpG name | Gene namea | FDRb | Bonfc | Function of the gene product | Disease/Trait associationd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg07677157 | RP11-221N13.4 | 9.56E-15 | 9.56E-15 | ||

| cg08057120 | 7.78E-12 | 1.56E-11 | |||

| cg26408927 | CACNA1D | 2.26E-10 | 6.79E-10 | Mediate the entry of calcium ions into excitable cells. Involved in a variety of calcium-dependent processes. Regulates intracellular processes such as contraction, secretion, neurotransmission and other gene expression | Sinoatrial node dysfunction and deafness. Hypertension. Body mass index. Insulin resistance/response. Systolic blood pressure. Diastolic blood pressure. Visceral adipose tissue/subcutaneous adipose tissue ratio. Type 2 diabetes |

| cg27487222 | 7.37E-07 | 2.95E-06 | |||

| cg11031221 | LINC00511 | 1.56E-06 | 7.78E-06 | A long non-protein coding RNA, involved in the regulation of gene expression during tumor progression | |

| cg22688137 | 6.01E-05 | < 0.001 | |||

| cg24833462 | AC023672.2 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| cg20063141 |

ONECUT2/ |

< 0.001 | 0.004 | This gene encodes a member of the one cut family of transcription factors, which are characterized by a cut domain and an atypical homeodomain | |

| cg08889373 | ACOT7/RP1-202O8.3 | 0.001 | 0.009 | Protein hydrolyzes the CoA thioester of palmitoyl-CoA and other long-chain fatty acids | Type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis |

| cg14792781 | GRHL1 | 0.002 | 0.016 | Is a transcription factor necessary during development | Cancer. Type 1 diabetes |

| cg14634473 | 0.002 | 0.021 | |||

| cg21940081 | IMP4 | 0.003 | 0.037 | Part of the 60-80S U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein (U3 snoRNP) complex. Responsible for early cleavage steps of pre-18S ribosomal RNA processing | |

| cg03877706 | NCAM2 | 0.003 | 0.041 | Belongs to the immunoglobulin superfamily. May play important roles in selective fasciculation and zone-to-zone projection of the primary olfactory axons | Obesity. Visceral fat |

| cg00303773 | TOM1L2 | 0.005 | 0.070 | Participate in vesicular trafficking. Play a role in endosomal sorting | Body mass. Type 2 diabetes |

| cg10113471 | 0.005 | 0.069 | |||

| cg23304747 | PITPNM2 | 0.008 | 0.123 | Catalyzes the transfer of phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylcholine between membranes (in vitro). Binds calcium ions | |

| cg14972510 | BAG4 | 0.010 | 0.167 | Inhibits the chaperone activity of HSP70/HSC70. Prevents constitutive TNFRSF1A signaling. Negative regulator of PRKN translocation to damaged mitochondria | |

| cg26561082 | DIP2C | 0.011 | 0.197 | The protein shares strong similarity with a Drosophila protein which interacts with the transcription factor disco and is expressed in the nervous system | Blood metabolite levels |

| cg24869056 | HPS1 | 0.012 | 0.235 | Play a role in organelle biogenesis associated with melanosomes, platelet dense granules and lysosomes | Obesity-related traits |

| cg14629524 | KDM3B | 0.020 | 0.401 | Histone demethylase that specifically demethylates Lys-9 of histone H3, thereby playing a central role in histone code | |

| cg04156896 | MFSD2A | 0.021 | 0.459 | Transmembrane protein and sodium-dependent lysophosphatidylcholine transporter involved in the establishment of the blood-brain barrier | |

| cg27367992 | ST6GAL1 | 0.021 | 0.451 | Catalyzes the transfer of sialic acid from CMP-sialic acid to galactose-containing substrates | Type 2 diabetes |

| cg08343240 | AC008703.1 | 0.024 | 0.573 | RNA gene | |

| cg27545041 | 0.024 | 0.567 | An important paralog of this gene is INTS6 / RNA Gene and is affiliated with the non-coding RNA class | ||

| cg04046944 | CACNA1S | 0.025 | 0.614 | This gene encodes one of the five subunits of the slowly inactivating L-type voltage-dependent calcium channel in skeletal muscle cells | |

| cg06225648 | 0.025 | 0.651 | |||

| cg12381697 | CCM2 | 0.028 | 0.751 | ||

| cg13207339 | PARK2 | 0.030 | 0.849 | A component of a multiprotein E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that mediates the targeting of substrate proteins for proteasomal degradation | Metabolite levels. Body mass index. Aging |

| cg22345432 |

PXN/ PXN-AS1 |

0.033 | 0.972 | Involved in actin-membrane attachment at sites of cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix (focal adhesion)/RNA Gene and is affiliated with the non-coding RNA class | |

| cg17158941 | C7orf50/AC073957.15 | 0.040 | 1 | Chromosome 7 Open Reading Frame 50 | C-reactive protein levels or total cholesterol levels |

| cg03289031 | ZNF629 | 0.040 | 1 | ||

| cg26540402 | PRF1 | 0.040 | 1 | Plays a key role in secretory granule-dependent cell death and in defense against virus infected or neoplastic cells | |

| cg16657582 | 0.043 | 1 | |||

| cg21902759 | RAB40B | 0.043 | 1 | Substrate-recognition component of a SCF-like ECS (Elongin-Cullin-SOCS-box protein) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex which mediates the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of target proteins | |

| cg19377056 | ARHGAP39 | 0.049 | 1 |

aUCSC gene name

bFDR - CBCT False Discovery Rate significance (p < 0.05)

cBonf - CBCT Bonferroni significance (p < 0.05)

dSelected from GeneToFunction database (human only) and Gene Cards disease associations

Fig. 2.

Q-Q plots for a cisplatin-based chemotherapy (CBCT) model, methylation β value as the dependent and CBCT as the independent variable, adjusted for smoking, age, testosterone, and cell count. b Metabolic syndrome (MetS) model, MetS as the dependent and methylation β value as the independent variable, adjusted for CBCT, smoking and age

Fig. 3.

Functional gene networks of cisplatin-based chemotherapy (a) and metabolic syndrome (b) related genes reconstructed using the GENIUS tool. Nodes represent genes and edges (arrows) show the directions of the interactions found. Size of nodes is proportional to a gene network degree (number of neighbors of a given gene in the network). A node color intensity represents significance from the differential methylation analysis (high intensity colors represent highly significant genes, adjusted p value for panel (a) and unadjusted p value for panel (b) shown). Nodes marked with black circles represent genes associated with any of the metabolic syndrome trait

DNA methylation and risk of developing MetS

We could not identify MetS differentially methylated CpG sites after adjusting for age, smoking, CBCT, and multiple testing (FDR or Bonferroni) (Fig. 2b). We present the top 15 differentially methylated CpG sites (unadjusted p values) (Table 3) of which 11 CpGs were located on an open sea and four on the CpG island shores. None of the multivariate models showed epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) significant results, and their top hits differed (Additional file 1: Figure S5B). In addition, models for the individual MetS components (hypertension, cholesterol, waist circumference, fasting glucose, and triglycerides) did not give EWAS significant associations. There was no overlap between the top 2000 nominally significant CpGs for these five MetS component models and the MetS model (Additional file 1: Figure S6).

Table 3.

The 15 CpG sites with lowest unadjusted p values for associations between DNA methylation (DNAm) and metabolic syndrome (MetS)

| CpG name | Genea | Pb | Gene function | Disease/Trait associationc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg01562302 | SLC7A7 | 4.37E-06 | Involved in the sodium-independent uptake of dibasic amino acids and sodium-dependent uptake of some neutral amino acids | |

| cg06500161 | ABCG1 | 6.50E-06 | Involved in macrophage cholesterol and phospholipids transport, and may regulate cellular lipid homeostasis in other cell types | Type 1 diabetes |

| cg05489343 | COLEC12 | 1.26E-05 | Scavenger receptor associated with host defense, C-lectin family, proteins that possess collagen-like sequences and carbohydrate recognition domains | Obesity-related traits |

| cg07203167 | NCF2/SMG7 | 1.57E-05 | Required for activation of the latent NADPH oxidase | Insulin resistance |

| cg23064281 | 2.44E-05 | |||

| cg22084453 | 2.51E-05 | |||

| cg09209794 | TMEM63A | 3.15E-05 | Acts as an osmosensitive calcium-permeable cation channel | |

| cg23167087 | TTC18/CFAP70 | 3.20E-05 | ||

| cg16007266 | NLRC5 | 3.31E-05 | Plays a role in cytokine response and antiviral immunity through its inhibition of NF-kappa-B activation and negative regulation of type I interferon signaling pathways | HDL cholesterol |

| cg14810357 | AC064875.2 | 3.49E-05 | ||

| cg09120938 | CHFR | 3.67E-05 | Regulates cell cycle entry into mitosis and, therefore, may play a key role in cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis, belongs to DNA damage pathway | |

| cg02255098 | BCAM | 3.71E-05 | A receptor for the extracellular matrix protein, laminin. | Waist-to-hip circumference ratio |

| cg22926824 | AGAP1 | 4.18E-05 | Direct regulator of the adaptor-related protein complex 3 on endosomes | Cardiovascular disease in hypertension (calcium channel blocker interaction) |

| cg22003124 | 4.21E-05 | |||

| cg16307144 | DPF1 | 4.55E-05 | Gene Ontology (GO) annotations related to this gene include nucleic acid binding |

aGene UCSC gene name

bP value unadjusted p value

cSelected from GeneToFunction database (human only) and Gene Cards disease associations

We identified one network-structure for the nine MetS-associated genes found in the GENUS database (Fig. 3b).

Overlap between CBCT and MetS associations

There were no FDR or Bonferroni significantly differentially methylated CpG sites associated with both CBCT and MetS. However, the comparison of the top 2000 CpG sites associated with CBCT and MetS with unadjusted p values < 0.05 for both analyses identified ten common CpG sites (Table 4).

Table 4.

Annotations for the nine overlapping CpGs for the cisplatin-based chemotherapy (CBCT) model and metabolic syndrome (MetS) model for the 2000 CpGs with the lowest unadjusted p values < 0.05

| Cpg name | Genea | Pb CBCT model | Pb MetS model | Gene function | Disease/Trait associationd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg25165017 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| cg27087650 | BCL3 | < 0.001 | 0.012 | Contributes to the regulation of cell proliferation | |

| cg10785263 | < 0.001 | 0.020 | |||

| cg17986793 | MX1 | < 0.001 | 0.022 | Gene product, Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MX1 gene | |

| cg10587886 | LMCD1-AS1 | < 0.001 | 0.044 | LMCD1 antisense RNA 1 | |

| cg18871648 | ELMSAN1 | < 0.001 | 0.050 | ELM2 and Myb/SANT domain containing 1 | |

| cg07688244 | < 0.001 | 0.098 | |||

| cg14792781 | GRHL1 | < 0.001 | 0.127 | This gene encodes a member of the grainyhead family of transcription factors. The encoded protein can exist as a homodimer or can form heterodimers with sister-of-mammalian grainyhead or brother-of-mammalian grainyhead. This protein functions as a transcription factor during development | |

| cg25273039 | NXPH1 | < 0.001 | 0.165 | The product protein forms a very tight complex with alpha neurexins, a group of proteins that promote adhesion between dendrites and axons | Waist-to-hip ratio adjusted for body mass index, Obesity-related traits |

| cg19509829 | ATP2A2 | < 0.001 | 0.215 | Product Belongs to a family of ATPase enzymes that helps control the level of positively charged calcium atoms (calcium ions) inside cells | Glucose homeostasis traits |

aGene UCSC gene name

bP unadjusted p value

cSelected from GeneToFunction database (human only) and Gene Cards disease associations

Pathway enrichment for CBCT-associated CpGs

Genes in approximation to 78 differentially methylated CpG sites (FDR < 0.1) associated with CBCT were analyzed for gene enrichment to provide a functional interpretation of our results. We identified the “PTK6 Regulates RHO GTPases, RAS GTPase, and MAP kinase” Reactome pathway as significantly enriched (adjusted p value = 0.03). For GO biological process, we found the “cellular response to growth hormone stimulus” pathway significantly enriched (p value = 0.005). For GO cellular component, the “L-type voltage-gated calcium channel complex” pathway was significantly enriched (p value = 0.02). We did not find significant pathways for KEGG and GO molecular function.

Differentially methylated regions associated with CBCT and MetS

Using bumphunting, 419 regions (bumps) were identified; however, none were significantly associated with CBCT based on adjusted p values (data not presented). Neither did we identify significant hits when using DMRcate for the two model (data not presented).

We checked if genomic coordinates of the CpGs of interest were present as SNPs in GWAS Central database. We did not find any of the CBCT, MetS, and overlapping CpG sites from Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively. In the EWAS Atlas database, we found one association with post-obese (cg07677157), and one association with high-saturated fatty acids diet (cg07677157) for CBCT-associated CpGs. From our CpG sites related to MetS, there was one hit cg06500161 (ABCG1), associated with MetS, BMI, and type 2 diabetes in this database. In the overlapping CpGs, we found cg27087650 associated with BMI.

Discussion

In this EWAS, we identified lasting CBCT-related effects in 35 differentially methylated CpG sites across the genome, on average 16 years after treatment. These effects may be attributed to the initial CBCT, and/or to the small amount of platinum persistent in serum post-treatment [5]. We found insulin- and body mass-related genes in proximity to the CBCT-associated hits, supporting our hypothesis that the CBCT-MetS relationship is linked to epigenetics. Interestingly, we found CpG sites in proximity to the gene ABCG1, which has been associated to body mass, triglycerides, HDL-C, atherosclerosis, and type 2 diabetes in EWAS [23–25], among our nominally significant MetS CpGs.

The gene closest to the CBCT− top hit, cg07677157, is RPSAP52, a gene linked to type 2 diabetes in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [26]. The top annotated CBCT gene, CACNA1D, encodes voltage-dependent calcium channels, which regulate insulin release. Polymorphisms in CACNA1D are also associated with type 2 diabetes [27], linked to diastolic and systolic blood pressure [28], and ototoxicity [29]. Other CBCT-associated genes were ACOT7, implicated in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes [30] and atherosclerosis [31]; GRHL1, encoding a transcription factor involved in epithelial development and linked to several types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and type 1 diabetes; and TOM1L2, linked to body mass and type 2 diabetes in GWAS [32] (Table 2).

We found “PTK6 Regulates RHO GTPases, RAS GTPase, and MAP kinases” which is part of the RAS signal transduction pathway enriched with CBCT-associated methylation. The pathway regulates cell differentiation and plays a role in cell proliferation [33–35], which might be a relevant mechanism in relation to the increased risk of second cancer after CBCT in TC survivors [36]. The pathway “cellular response to growth hormone stimulus” is also enriched for CpGs associated to CBCT. The involvement of these oncogenic pathways is consistent with the cytotoxicity of CBCT, which is interesting considering the rather long time window between treatment and DNAm measurements.

Examples of MetS-associated genes include COLEC12, encoding a scavenger receptor involved in several functions associated with host defense; NCF2, for which increased expression has been observed in patients with insulin resistance [37]; and SMG7, playing a role in p53 function in response to DNA damage [38].

The possible relationship between CBCT-induced DNAm and susceptibility for developing MetS was analyzed by exploring the sequence of events separately, as there are no well-established tools for doing high-dimension mediation analysis that fit with our design. The overlap between the two models, including the top 2000 hits, was ten sites (Table 4). These might be spurious findings since associations were nominal. The small overlap might suggest two unrelated mechanisms leading to MetS which was supported by publicly available distinct EWAS (EWAS Atlas). Nonetheless, for both models, the majority of top CpGs was linked to factors pertaining to MetS. Additionally, among the genes that clustered in the network analysis, those with the highest network degree (CACNA1D, DIP2C, and GRHL1 for CBCT, and ABCG1 and NCF2 for MetS) were all associated with MetS. The network analyses suggest that CBCT and MetS-related effects may be mediated synergistically. We speculate that changes in methylation in these clustered genes might affect gene expression, thus increasing the likelihood of developing MetS. These findings support the notion that DNAm may mediate the effect of CBCT on MetS risk later in life. Validation and replication of the top results are needed in an independent cohort. Inclusion of a non-oncological control group, with and without MetS, will further elucidate if the findings are independent of tumor intrinsic factors, and if the MetS hits are related to CBCT.

The survivors in our study who developed MetS have somewhat lower testosterone levels than those without MetS, regardless of CBCT, thus low testosterone may have confounded the results. Previous studies have shown that lower total testosterone level is associated with higher risk of developing MetS [39]. Independently of the model used, testosterone did not markedly alter the significant associations. This indicates that the MetS DNAm association is not attributable to low testosterone levels.

Strengths of the study include a reliable and broadly characterized study population which has been followed for many years. In addition, we have considered the most important confounding factors by matching the groups. Furthermore, the epigenetic analyses have been performed on EPIC BeadChip arrays, which provides state-of-the art tool for epigenome-wide association analyses, covering over 850,000 CpG sites. The EPIC array represents a significant improvement compared to its predecessor, the HM450 array, with increased genome coverage of regulatory regions [40]. Finally, we used curated annotation resources and updated GRCh38/hg38 genome [41].

Some limitations of the present study should also be considered. Even though the total number of TC survivors was large, the sample size of those treated with surgery only and developed MetS was 34. Due to the limited sample size, we chose the minimally adjusted model for MetS. A power issue may thus contribute as to why there were no differentially DNA methylated CpG sites associated with MetS after adjusting for multiple testing. We were not able to distinguish between the effect of the initial CBCT and the effect of platinum residuals [5] as this would have needed a time-series analysis. It is not possible to rule out that some of the differential DNA methylation associated to CBCT could be related to tumor-specific intrinsic factors. However, TC stage markers of DNA methylation including HOXA9, RASSF1A, and SCGB3A1 [42] were not observed, indicating that potential confounding by such factors was unlikely. The possible impact of second primary cancer is negligible due to long time span between sampling and diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that CBCT has long-term effects on the epigenome. Although we could not directly link the CBCT effects to the risk of developing MetS, it may still play a role in the development of MetS in TC survivors. This is supported by the observation that the differential DNAm occurs in genes related to MetS. Furthermore, our results contribute to a better understanding of the cellular mechanisms behind the development of MetS in TC survivors treated with CBCT. Although the influence of CBCT on the epigenome is plausible, validation of the observed differential methylation of specific CpGs is necessary. Our findings also indicate that other adverse effects of CBCT, such as ototoxicity, may be mediated by epigenetic changes. These topics could be subject to future studies, also encompassing other cancer forms using CBCT, and risk of second cancer. In terms of clinical perspective, our results may provide early identification of individuals with increased risk for development of MetS.

Methods

Study population and patient assessments

Participants were long-term survivors of unilateral TC diagnosed from 18 to 75 years of age, treated between 1980 and 1994. The original national cohort consisted of 1463 men (Caucasians) who participated in follow-up survey I (SI) at five Norwegian university hospitals during the period 1998–2002. In total, 990 males, younger than 60 years old at SI, were subsequently evaluated with regard to CVD and MetS in a second survey (SII) performed 2007–2008 [15]. A third survey (SIII) was performed in 2015–2016. Overall, 279 participants with MetS data obtained in SII, and frozen whole blood samples from either SI (n = 137), SII (n = 132), or SIII (n = 8) available for DNA analyses, were included in the present study. We included the samples that best fitted the matching criteria (see below). For those who had samples from more than one survey, we chose the DNA obtained at the earliest time point after diagnosis to capture as much of the CBCT related effects as possible.

Data from questionnaires, clinical examinations (including blood pressure and waist circumference measurements), and laboratory tests (including fasting blood glucose and blood lipid measurements) were retrieved from SII. Smoking status was classified from questionnaire data into three groups: never, former, and current smoker. Age was used as a continuous variable in all statistical analyses. All routine blood samples were analyzed at the Oslo University Hospital. Plasma levels of lipids and glucose were measured enzymatically. Serum levels of testosterone were determined using immunoassays. MetS was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program expert panel, as the presence of minimum three of the following five criteria: blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg, HDL-cholesterol < 1.0 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, waist circumference > 102 cm, and fasting glucose ≥ 6.5 mmol/L [43, 44]. Epigenomic changes related to MetS were assumed to be present at the sampling time point. Data regarding initial tumor stage, histology, and treatment details were retrieved from medical records. Treatment details according to stage and histology [45], CVD risk, and morbidity data from SI and SII have been published previously [9, 15, 46, 47]. Cancer Registry follow-up showed that 51 survivors acquired a second primary cancer within the cohort follow-up time (SIII). These cancers were diagnosed on average 6 (SD = 3) years after sample donation.

From the 279 TC survivors included, 103 had surgery only (orchiectomy with or without retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for selected cases) due to stage I disease, whereas 176 had undergone both surgery and CBCT (all with metastatic disease) (Fig. 1). From the surgery only (CBCT−) and the treatment (CBCT+) groups, we selected similar fractions of patients with MetS. These four groups were frequency-matched on smoking habits and age at blood sampling, allowing no more than two years difference in mean age. However, complete matching was not possible due to limited number of patients categorized as CBCT+ and MetS−. From this 2 × 2 design, we analyzed the data using a CBCT model and a MetS model, where all cases were included in both models (Fig. 1). Comparing the top hits from the two models enables the identification of CpG sites associated with both CBCT and MetS. This study was approved by Regional Ethical Committee (REC) south east D, reference 2015/1332.

DNA methylation profiling

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood using standard chloroform–phenol extraction method. DNA concentration and purity of the DNA samples were analyzed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA from ten samples was isolated using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) and the Qiacube (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Of the 279 samples, four samples had only 300 ng (500 ng recommended); however, they showed good array quality in all control steps. Bisulfite conversion of the genomic DNA was done using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo) and whole-genome DNAm were analyzed with the Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit (Illumina) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. This array covers 850,000 individual CpGs at CpG islands, RefSeq genes, ENCODE open chromatin, ENCODE transcription factor binding sites, and FANTOM5 enhancers sites. The 279 samples were randomized on three 96-well plates according to the four groups described.

The resulting raw data were analyzed using minfi v.1.20.2 in the R statistical environment v3.3.3 [48]. For details, see Supplementary method information. Two samples were excluded, one due to missing smoking information, and one being an outlier in the principal component analyses (Additional file 1: Figure S1). This resulted in a quality-controlled dataset of 277 samples and 862,400 CpG sites. CpG sites were mapped to the human genome (GRCh37/hg19) using the annotation file provided by the manufacturer (Illumina) [49] and further curated and translated to GRCh38/hg38 [41]. Additional information were retrieved from the UCSC genome browser [50, 51] and GeneCards (www.genecards.org) [52] and Gene2Function (http://www.gene2function.org) [53]. Relative proportion of cell types (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, granulocytes, and monocytes) from the methylation profiles were estimated using the reference-based Houseman method [54, 55].

We deployed GENIUS (GEne Networks Inference Using Signatures) tool to predict local gene networks and key genes for biological functions [56]. The network was constructed using supervised machine learning method to find expression signatures. Input for the gene network was the FDR significant genes from the CBCT and MetS model. The network was visualized with Cytoscope 3.7.1 according to the nodes connectivity and degree [57].

Statistics

The methylation values were transformed to β values (between 0 and 1), representing the intensity of methylation [58]. We used a linear regression model to investigate if cell type composition was associated with CBCT, adjusting for age at blood sampling and smoking habits. We also tested if MetS was associated with testosterone levels, adjusting for age. The results indicated that testosterone and cell type (five out of six cell types, B cells was dropped) composition might be confounders. The robust linear CBCT model with DNA methylation status as the dependent variable was therefore adjusted for age, smoking, cell type, and testosterone. To investigate the associations between DNAm and MetS with the latter as the dependent variable, we used a generalized logistic regression model. The MetS model was adjusted for age, smoking, and CBCT. Models with the best fit were included, and additional regression models tested are available in the Supplementary information (Additional file 1: Figure S4 and Figure S5). Additionally, separate generalized logistic regression models with the five variables underlying the MetS diagnosis (hypertension, cholesterol, waist circumference, fasting glucose, and triglycerides) as dependent variable and with the same covariates were tested. To adjust for multiple testing, Benjamini and Hochberg’s FDR [59] and Bonferroni correction [60] were applied to all models. Differentially methylated CpG sites, identified in the CBCT model and the MetS model, were defined as the intersection of the top 2000 hits with the lowest unadjusted p values.

In order to identify differentially methylated regions (DMR), we used two approaches, bumphunter [61] and dmrcate [62–64]. Bumphunter (v.1.20.0) was run with 1000 permutations and the cutoff was set to 0.05, corresponding to 5% difference on the β values on the CBCT model. We ran the DMRcate function (v.1.14.0) with default settings (max gap 1000 nucleotides between two significant probes and DNAm as outcome) on the CBCT model and by flipping the function around with the dichotomous variable as outcome on the CBCT and MetS models.

Gene enrichment analysis and CpG characterization

CpG sites passing an FDR adjustment (p value < 0.1) were used to assess pathways enriched for differential DNAm. We employed Enrichr (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr) [65, 66] a platform for KEGG [67], Reactome 2016 (v.62), and Gene Ontology (GO) 2018 (biological process, molecular function, and cellular component) pathways analysis [68, 69]. We performed an unweighted analysis, and reported p values are based on Fisher’s exact test.

We employed GWAS Central database (www.gwascentral.org) to evaluate if any of CpG sites of interest were previously reported as known SNPs [70]. We further scanned for associations between CpG sites of interest and known epigenome-wide associations from literature studies. We used the EWAS Atlas resource (https://bigd.big.ac.cn/ewas/index) [71]. This database features a large number of high-quality, manually curated, EWAS associations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. PCA plot of β-methylation for the four sample groups, showing one outlier. The plot is coloured by different groups. Blue group did not develop MetS, but received CBCT, green did not develop MetS and did not receive CBCT, red developed MetS and received CBCT, and black developed MetS and did not receive CBCT. Figure S2. Barplot of the global average methylation per sample. Blue and green indicate whether patients had received cisplatin or not, respectively. Samples were sorted descending using their average methylation value. Figure S3. Boxplot of smoking associated CpGs for the genes AHRR and F2RL3. Never, Former and Current, refer to the smoking status as presented in Table 1. Figure S4. Q-Q plots for A) CBCT model, methylation β-value as the dependent and CBCT as the independent variable, adjusted for smoking, age, and cell count. B) MetS model, MetS as the dependent and methylation β-value as the independent variable, adjusted for CBCT, smoking, age and cell count. Figure S5. Q-Q plots for A) CBCT model, methylation β-value as the dependent and CBCT as the independent variable, adjusted for smoking, and age. B) MetS model, MetS as the dependent and methylation β-value as the independent variable, adjusted for CBCT, smoking, age, testosterone and cell count. Figure S6. Venn-diagram illustrating the overlapping number of top 2000 nominally significant CpGs between the original model, and the models with the 5 individual criteria of the MetS-diagnosis as dependent variable. Criteria is according to the National Cholesterol Education Program expert panel: Hypertension = blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, HDL = HDL-cholesterol <1.0 mmol/L, Triglycerides = triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L, Waist Circ. = waist circumference >102 cm, and Glucose = fasting glucose ≥6.5 mmol/L.

Acknowledgments

The Infinium MethylationEPIC Kit was processed at the Human Genetics Foundation, Torino Laboratory of Molecular Epidemiology, Italy. We thank the staff at Human Genetics Foundation in Torino, especially Silvia Polidoro, for this service. We thank Marianne Lauritzen at the Cancer Registry of Norway for laboratory assistance, Rolf I. Skotheim and Anne Cathrine Bakken for assistance retrieving and preparing samples, Elina Vinberg and Kari Furu for project coordination, and Sinan U. Umu for excellent help with data analysis.

Abbreviations

- BEP

Bleomycin, etoposide, and platinum

- BMI

Body mass index

- CBCT

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy

- CpG

Cytosine nucleotide followed by a guanine nucleotide

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DMR

Differentially methylated regions

- DNAm

DNA methylation

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- TC

Testicular cancer

Authors’ contributions

Concept and design: TBH, SDF, TG, HSH, TBR. Funding support: TBH, SDF, TG, HSH, TBR. Provision of study materials or patients: SDF, HSH. Collection and assembly of data: CB-J, CMP, MWW, SDF, TG, HSH, TBR. Data analyses and interpretation: All authors. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Funding

The study was funded by the Norwegian Cancer Society (grant number 190157-2017). SDF had a grant from The Radium Hospital Foundation.no 335007.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since individual privacy could be compromised, but are available from the corresponding author on request and with appropriate approvals.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants have given an informed consent. This study was approved by Regional Ethical Committee (REC) south east D, reference 2015/1332.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hege S. Haugnes and Trine B. Rounge contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13148-019-0764-4.

References

- 1.Einhorn LH, Donohue J. Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum, vinblastine, and bleomycin combination chemotherapy in disseminated testicular cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:293–298. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-3-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honecker F, Aparicio J, Berney D, Beyer J, Bokemeyer C, Cathomas R, Clarke N, Cohn-Cedermark G, Daugaard G, Dieckmann KP, et al. ESMO Consensus Conference on testicular germ cell cancer: diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:1658–1686. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kier MG, Lauritsen J, Mortensen MS, Bandak M, Andersen KK, Hansen MK, Agerbaek M, Holm NV, Dalton SO, Johansen C, Daugaard G. Prognostic factors and treatment results after bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin in germ cell cancer: a population-based study. Eur Urol. 2017;71:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haugnes HS, Bosl GJ, Boer H, Gietema JA, Brydoy M, Oldenburg J, Dahl AA, Bremnes RM, Fossa SD. Long-term and late effects of germ cell testicular cancer treatment and implications for follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3752–3763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kvammen O, Myklebust TA, Solberg A, Moller B, Klepp OH, Fossa SD, Tandstad T. Long-term relative survival after diagnosis of testicular germ cell tumor. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:773–779. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaid MA, Gathirua-Mwangi WG, Fung C, Monahan PO, El-Charif O, Williams AM, Feldman DR, Hamilton RJ, Vaughn DJ, Beard CJ, et al. Clinical and genetic risk factors for adverse metabolic outcomes in North American testicular cancer survivors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:257–265. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willemse P M, Burggraaf J, Hamdy N A T, Weijl N I, Vossen C Y, van Wulften L, van Steijn-van Tol A Q M J, Rosendaal F R, Osanto S. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk in chemotherapy-treated testicular germ cell tumour survivors. British Journal of Cancer. 2013;109(1):60–67. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haugnes HS, Aass N, Fossa SD, Dahl O, Klepp O, Wist EA, Svartberg J, Wilsgaard T, Bremnes RM. Components of the metabolic syndrome in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:241–248. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Neill S, O'Driscoll L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes Rev. 2015;16:1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults—findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Haas EC, Altena R, Boezen HM, Zwart N, Smit AJ, Bakker SJ, van Roon AM, Postma A, Wolffenbuttel BH, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Early development of the metabolic syndrome after chemotherapy for testicular cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:749–755. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willemse PM, van der Meer RW, Burggraaf J, van Elderen SG, de Kam ML, de Roos A, Lamb HJ, Osanto S. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous fat increase, insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia in testicular cancer patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:351–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Haugnes HS, Wethal T, Aass N, Dahl O, Klepp O, Langberg CW, Wilsgaard T, Bremnes RM, Fossa SD. Cardiovascular risk factors and morbidity in long-term survivors of testicular cancer: a 20-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4649–4657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beyrouthy MJ, Garner KM, Hever MP, Freemantle SJ, Eastman A, Dmitrovsky E, Spinella MJ. High DNA methyltransferase 3B expression mediates 5-aza-deoxycytidine hypersensitivity in testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9360–9366. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duale N, Lindeman B, Komada M, Olsen AK, Andreassen A, Soderlund EJ, Brunborg G. Molecular portrait of cisplatin induced response in human testis cancer cell lines based on gene expression profiles. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeller C, Dai W, Steele NL, Siddiq A, Walley AJ, Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Rizzo S, van der Zee A, Plumb JA, Brown R. Candidate DNA methylation drivers of acquired cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer identified by methylome and expression profiling. Oncogene. 2012;31:4567–4576. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koul S, McKiernan JM, Narayan G, Houldsworth J, Bacik J, Dobrzynski DL, Assaad AM, Mansukhani M, Reuter VE, Bosl GJ, et al. Role of promoter hypermethylation in Cisplatin treatment response of male germ cell tumors. Mol Cancer. 2004;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barres R, Zierath JR. DNA methylation in metabolic disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:897S–8900. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Symonds ME, Sebert SP, Hyatt MA, Budge H. Nutritional programming of the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:604–610. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Buklijas T, Low FM, Beedle AS. Epigenetic mechanisms that underpin metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:401–408. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun KVE, Dhana K, de Vries PS, Voortman T, van Meurs JBJ, Uitterlinden AG, consortium B, Hofman A, Hu FB, Franco OH, Dehghan A. Epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) on lipids: the Rotterdam Study. Clin Epigenetics 2017, 9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Fernandez-Sanles A, Sayols-Baixeras S, Subirana I, Degano IR, Elosua R. Association between DNA methylation and coronary heart disease or other atherosclerotic events: a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campanella G, Gunter MJ, Polidoro S, Krogh V, Palli D, Panico S, Sacerdote C, Tumino R, Fiorito G, Guarrera S, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of adiposity and future risk of obesity-related diseases. Int J Obes (2005) 2018;42:2022–2035. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Wei, Rasheed Asif, Tikkanen Emmi, Lee Jung-Jin, Butterworth Adam S, Howson Joanna M M, Assimes Themistocles L, Chowdhury Rajiv, Orho-Melander Marju, Damrauer Scott, Small Aeron, Asma Senay, Imamura Minako, Yamauch Toshimasa, Chambers John C, Chen Peng, Sapkota Bishwa R, Shah Nabi, Jabeen Sehrish, Surendran Praveen, Lu Yingchang, Zhang Weihua, Imran Atif, Abbas Shahid, Majeed Faisal, Trindade Kevin, Qamar Nadeem, Mallick Nadeem Hayyat, Yaqoob Zia, Saghir Tahir, Rizvi Syed Nadeem Hasan, Memon Anis, Rasheed Syed Zahed, Memon Fazal-ur-Rehman, Mehmood Khalid, Ahmed Naveeduddin, Qureshi Irshad Hussain, Tanveer-us-Salam, Iqbal Wasim, Malik Uzma, Mehra Narinder, Kuo Jane Z, Sheu Wayne H-H, Guo Xiuqing, Hsiung Chao A, Juang Jyh-Ming J, Taylor Kent D, Hung Yi-Jen, Lee Wen-Jane, Quertermous Thomas, Lee I-Te, Hsu Chih-Cheng, Bottinger Erwin P, Ralhan Sarju, Teo Yik Ying, Wang Tzung-Dau, Alam Dewan S, Di Angelantonio Emanuele, Epstein Steve, Nielsen Sune F, Nordestgaard Børge G, Tybjaerg-Hansen Anne, Young Robin, Benn Marianne, Frikke-Schmidt Ruth, Kamstrup Pia R, Jukema J Wouter, Sattar Naveed, Smit Roelof, Chung Ren-Hua, Liang Kae-Woei, Anand Sonia, Sanghera Dharambir K, Ripatti Samuli, Loos Ruth J F, Kooner Jaspal S, Tai E Shyong, Rotter Jerome I, Chen Yii-Der Ida, Frossard Philippe, Maeda Shiro, Kadowaki Takashi, Reilly Muredach, Pare Guillaume, Melander Olle, Salomaa Veikko, Rader Daniel J, Danesh John, Voight Benjamin F, Saleheen Danish. Identification of new susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes and shared etiological pathways with coronary heart disease. Nature Genetics. 2017;49(10):1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/ng.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinbothe TM, Alkayyali S, Ahlqvist E, Tuomi T, Isomaa B, Lyssenko V, Renstrom E. The human L-type calcium channel Cav1.3 regulates insulin release and polymorphisms in CACNA1D associate with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:340–349. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2758-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu X, Wang L, Lin X, Huang J, Charles Gu C, He M, Shen H, He J, Zhu J, Li H, et al. Genome-wide association study in Chinese identifies novel loci for blood pressure and hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:865–874. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liaqat K, Schrauwen I, Raza SI, Lee K, Hussain S, Chakchouk I, Nasir A, Acharya A, Abbe I, Umair M, et al. Identification of CACNA1D variants associated with sinoatrial node dysfunction and deafness in additional Pakistani families reveals a clinical significance. J Hum Genet. 2019;64:153–160. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0542-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Sanchez A, Pullen TJ, Chabosseau P, Zhang Q, Haythorne E, Cane MC, Nguyen-Tu MS, Sayers SR, Rutter GA. Disallowance of Acot7 in beta-cells Is required for normal glucose tolerance and insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2016;65:1268–1282. doi: 10.2337/db15-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wall VZ, Barnhart S, Kramer F, Kanter JE, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Pennathur S, Bolego C, Ellis JM, Gijon MA, Wolfgang MJ, Bornfeldt KE. Inflammatory stimuli induce acyl-CoA thioesterase 7 and remodeling of phospholipids containing unsaturated long (>/=C20)-acyl chains in macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2017;58:1174–1185. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M076489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Zuydam NR, Ahlqvist E, Sandholm N, Deshmukh H, Rayner NW, Abdalla M, Ladenvall C, Ziemek D, Fauman E, Robertson NR, et al. A Genome-wide association study of diabetic kidney disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2018;67:1414–1427. doi: 10.2337/db17-0914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gavine PR, Wang M, Yu D, Hu E, Huang C, Xia J, Su X, Fan J, Zhang T, Ye Q, et al. Identification and validation of dysregulated MAPK7 (ERK5) as a novel oncogenic target in squamous cell lung and esophageal carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:454. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1455-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCain J. The MAPK (ERK) Pathway: investigational combinations for the treatment of BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. P T. 2013;38:96–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta PB, Jenkins BL, McCarthy L, Thilak L, Robson CN, Neal DE, Leung HY. MEK5 overexpression is associated with metastatic prostate cancer, and stimulates proliferation, MMP-9 expression and invasion. Oncogene. 2003;22:1381–1389. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wanderås E.Hoff, Fosså S.D., Tretli S. Risk of subsequent non-germ cell cancer after treatment of germ cell cancer in 2006 Norwegian male patients. European Journal of Cancer. 1997;33(2):253–262. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(96)00458-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur S, Archer KJ, Devi MG, Kriplani A, Strauss JF, 3rd, Singh R. Differential gene expression in granulosa cells from polycystic ovary syndrome patients with and without insulin resistance: identification of susceptibility gene sets through network analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2016–2021. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo H, Cowen L, Yu G, Jiang W, Tang Y. SMG7 is a critical regulator of p53 stability and function in DNA damage stress response. Cell Discov. 2016;2:15042. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2015.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haring R, Volzke H, Felix SB, Schipf S, Dorr M, Rosskopf D, Nauck M, Schofl C, Wallaschofski H. Prediction of metabolic syndrome by low serum testosterone levels in men: results from the study of health in Pomerania. Diabetes. 2009;58:2027–2031. doi: 10.2337/db09-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pidsley R, Zotenko E, Peters TJ, Lawrence MG, Risbridger GP, Molloy P, Van Djik S, Muhlhausler B, Stirzaker C, Clark SJ. Critical evaluation of the Illumina methylationepic BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome Biol. 2016;17:208. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1066-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou W, Laird PW, Shen H. Comprehensive characterization, annotation and innovative use of Infinium DNA methylation BeadChip probes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e22. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa AL, Moreira-Barbosa C, Lobo J, Vilela-Salgueiro B, Cantante M, Guimarães R, Lopes P, Braga I, Oliveira J, Antunes L. DNA methylation profiling as a tool for testicular germ cell tumors subtyping. Epigenomics. 2018;10:1511–1523. doi: 10.2217/epi-2018-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC, Jr, Lenfant C, American Heart A, National Heart L, Blood I. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109:433–438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000111245.75752.C6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Mod Mechanisms. 2009;2:231–237. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brydoy M., Oldenburg J., Klepp O., Bremnes R. M., Wist E. A., Wentzel-Larsen T., Hauge E. R., Dahl O., Fossa S. D. Observational Study of Prevalence of Long-term Raynaud-Like Phenomena and Neurological Side Effects in Testicular Cancer Survivors. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101(24):1682–1695. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haugnes H. S., Aass N., Fosså S. D., Dahl O., Klepp O., Wist E. A., Wilsgaard T., Bremnes R. M. Predicted cardiovascular mortality and reported cardiovascular morbidity in testicular cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2(3):128–137. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wethal T, Kjekshus J, Roislien J, Ueland T, Andreassen AK, Wergeland R, Aukrust P, Fossa SD. Treatment-related differences in cardiovascular risk factors in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:8–16. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fortin JP, Triche TJ, Jr, Hansen KD. Preprocessing, normalization and integration of the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC array with minfi. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:558–560. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen K. IlluminaHumanMethylationEPICanno.ilm10b2.hg19: Annotation for Illumina’s EPIC methylation arrays. R package version 060 2016, https://bitbucket.com/kasperdanielhansen/Illumina_EPIC.

- 50.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. UCSC Gen Brow. 2002;6:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Casper J, Zweig AS, Villarreal C, Tyner C, Speir ML, Rosenbloom KR, Raney BJ, Lee CM, Lee BT, Karolchik D, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2018 update. Nucl Acids Res. 2018;46:762–769. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Safran M., Dalah I., Alexander J., Rosen N., Iny Stein T., Shmoish M., Nativ N., Bahir I., Doniger T., Krug H., Sirota-Madi A., Olender T., Golan Y., Stelzer G., Harel A., Lancet D. GeneCards Version 3: the human gene integrator. Database. 2010;2010(0):baq020–baq020. doi: 10.1093/database/baq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu Y, Comjean A, Mohr SE, FlyBase C, Perrimon N. Gene2Function: an integrated online resource for gene function discovery. G3 (Bethesda) 2017;7:2855–2858. doi: 10.1534/g3.117.043885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houseman EA, Molitor J, Marsit CJ. Reference-free cell mixture adjustments in analysis of DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1431–1439. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puelma T, Araus V, Canales J, Vidal EA, Cabello JM, Soto A, Gutierrez RA. GENIUS: web server to predict local gene networks and key genes for biological functions. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:760–761. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Du P, Zhang X, Huang CC, Jafari N, Kibbe WA, Hou L, Lin SM. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:587. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate—a Practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonferroni CE. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilita. Pubblicazioni del R Istituto Superiore di Scienze Economiche e Commerciali di Firenze. 1936;8:3–62. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jaffe AE, Murakami P, Lee H, Leek JT, Fallin MD, Feinberg AP, Irizarry RA. Bump hunting to identify differentially methylated regions in epigenetic epidemiology studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:200–209. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wand MP, Jones MC. Kernel smoothing: Crc Press; 1994.

- 63.Peters TJ, Buckley MJ, Statham AL, Pidsley R, Samaras K, V Lord R, Clark SJ, Molloy PL. De novo identification of differentially methylated regions in the human genome. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015, 8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Duong T. Local significant differences from nonparametric two-sample tests. J Nonparametric Stat. 2013;25:635–645. doi: 10.1080/10485252.2013.810217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen EY, Tan CM, Kou Y, Wang Z, Meirelles GV, Clar NR, Ma’yan A. Enrichr: interactive and colloborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, Koplev S, Jenkins SL, Jagodnik KM, Lachmann A, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:90–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:353–361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Croft D, Mundo AF, Haw R, Milacic M, Weiser J, Wu G, Caudy M, Garapati P, Gillespie M, Kamdar MR, et al. The Reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:472–477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, Sidiropoulos K, Gillespie M, Garapati P, Haw R, Jassal B, Korninger F, May B, et al. The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:649–655. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beck T, Hastings RK, Gollapudi S, Free RC, Brookes AJ. GWAS Central: a comprehensive resource for the comparison and interrogation of genome-wide association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:949–952. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li M, Zou D, Li Z, Gao R, Sang J, Zhang Y, Li R, Xia L, Zhang T, Niu G, et al. EWAS Atlas: a curated knowledgebase of epigenome-wide association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D983–d988. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Figure S1. PCA plot of β-methylation for the four sample groups, showing one outlier. The plot is coloured by different groups. Blue group did not develop MetS, but received CBCT, green did not develop MetS and did not receive CBCT, red developed MetS and received CBCT, and black developed MetS and did not receive CBCT. Figure S2. Barplot of the global average methylation per sample. Blue and green indicate whether patients had received cisplatin or not, respectively. Samples were sorted descending using their average methylation value. Figure S3. Boxplot of smoking associated CpGs for the genes AHRR and F2RL3. Never, Former and Current, refer to the smoking status as presented in Table 1. Figure S4. Q-Q plots for A) CBCT model, methylation β-value as the dependent and CBCT as the independent variable, adjusted for smoking, age, and cell count. B) MetS model, MetS as the dependent and methylation β-value as the independent variable, adjusted for CBCT, smoking, age and cell count. Figure S5. Q-Q plots for A) CBCT model, methylation β-value as the dependent and CBCT as the independent variable, adjusted for smoking, and age. B) MetS model, MetS as the dependent and methylation β-value as the independent variable, adjusted for CBCT, smoking, age, testosterone and cell count. Figure S6. Venn-diagram illustrating the overlapping number of top 2000 nominally significant CpGs between the original model, and the models with the 5 individual criteria of the MetS-diagnosis as dependent variable. Criteria is according to the National Cholesterol Education Program expert panel: Hypertension = blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg, HDL = HDL-cholesterol <1.0 mmol/L, Triglycerides = triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L, Waist Circ. = waist circumference >102 cm, and Glucose = fasting glucose ≥6.5 mmol/L.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available since individual privacy could be compromised, but are available from the corresponding author on request and with appropriate approvals.