Abstract

Lymphatic metastasis is a high-impact prognostic factor for mortality of breast cancer (BC) patients, and it directly depends on tumor-associated lymphatic vessels. We previously reported that lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory lymphangiogenesis is strongly promoted by myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors (M-LECPs) derived from the bone marrow (BM). As BC recruits massive numbers of provascular myeloid cells, we hypothesized that M-LECPs, within this recruited population, are specifically programmed to promote tumor lymphatics that increase lymph node metastasis. In support of this hypothesis, high levels of M-LECPs were found in peripheral blood and tumor tissues of BC patients. Moreover, the density of M-LECPs and lymphatic vessels positive for myeloid marker proteins strongly correlated with patient node status. It was also established that tumor M-LECPs coexpress lymphatic-specific, stem/progenitor and M2-type macrophage markers that indicate their BM hematopoietic-myeloid origin and distinguish them from mature lymphatic endothelial cells, tumor-infiltrating lymphoid cells, and tissue-resident macrophages. Using four orthotopic BC models, we show that mouse M-LECPs are similarly recruited to tumors and integrate into preexisting lymphatics. Finally, we demonstrate that adoptive transfer of in vitro differentiated M-LECPs, but not naïve or nondifferentiated BM cells, significantly increased metastatic burden in ipsilateral lymph nodes. These data support a causative role of BC-induced lymphatic progenitors in tumor lymphangiogenesis and suggest molecular targets for their inhibition.

Metastasis to regional lymph nodes (LNs) is a highly significant prognostic marker for survival of breast cancer (BC) patients.1, 2 LN metastasis is strongly promoted by tumor lymphangiogenesis, a process that increases the density of lymphatic vessels (LVs) responsible for transporting tumor cells to sentinel, intramammary, and axillary LNs.2 Tumor cells from LN lesions spread to distant organs, which is the main cause of mortality from cancer.2 Consistent with this notion, tumor lymphatic vessel density (LVD) and lymphovascular invasion are highly correlated with poor patient survival.2 It is, therefore, of great interest to understand the mechanisms of tumor lymphangiogenesis and resultant lymphatic metastasis in human clinical BC.

Despite clinical significance, the underlying mechanisms of tumor lymphangiogenesis are still incompletely understood and debated. It is presently thought that formation of new tumor lymphatics results exclusively from sprouting of preexisting vessels on stimulation by lymphangiogenic factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) C or VEGF-D.3, 4, 5 These factors activate their cognate receptor VEGF receptor (VEGFR)-3, expressed predominantly on lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), leading to proliferation, migration, and tube formation to generate new vessels.6 On the basis of this concept, sprouting from existing lymphatic vessels requires no LEC progenitors,7, 8 but rather relies on soluble lymphangiogenic factors produced by malignant cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs),9, 10, 11 and stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment. TAMs, in particular, have been implicated in promoting lymphatic formation and metastasis through overexpression of VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGF-A12, 13 as well as the production of proteases that promote tumor cell migration and vascular invasion.14

Although this concept recognizes the prolymphangiogenic role of activated macrophages, it does not effectively explain two unique properties of TAMs well documented in experimental models: de novo expression of markers restricted to the LEC lineage, which results in generation of hybrid myeloid-lymphatic cells; and integration of these hybrid cells into existing LV, an event that precedes sprouting and is manifested by sustained expression of hematopoietic- and myeloid-specific markers in tumor lymphatic vasculature. A shift of myeloid cells toward the LEC phenotype was shown by expression of classic lymphatic markers, such as lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (Lyve-1), podoplanin (Pdpn), and Vegfr-3 on CD11b+ macrophages in breast,15 gastric,16 colorectal,17 and other experimental tumors.18, 19, 20 Integration of such cells into tumor LV is evidenced by expression of myeloid markers in Lyve-1+ vascular structures, which is correlated with increased LVD18, 19, 20 and LN metastasis.15 Arguably, paracrine support of lymphangiogenesis by soluble factors requires neither expression of lymphatic endothelial proteins by TAMs nor intimate interactions with lymphatic vessels before sprouting. In contrast, these observations suggest that a subset of TAMs is, in fact, myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors (M-LECPs) that play a self-autonomous role in lymphatic formation. This is consistent with well-known plasticity of TAMs, most of which are bone marrow (BM)–derived immature myeloid cells,17, 21, 22 that harbor vascular progenitors.23 The progenitor status of M-LECPs is also supported by expression of stem cell markers, such as stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1) in mouse Pdpn+ BM cells20 and CD133 in human VEGFR-3+ blood-circulating cells.24 This idea is also supported by production of functional LECPs in vitro from immature hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells treated with inflammatory stimuli,15 endothelial factors,25 or plasma from BC patients.25 The impact of experimental LECPs on lymphatic function is evidenced by their ability to increase LVD20, 25 and enhance metastasis in vivo.15 Collectively, these findings show that M-LECPs, a subset of cells that coexpress myeloid-, LEC-, and stem-specific markers, use both paracrine and self-autonomous mechanisms to expand tumor lymphatics.

Although the validation of this concept is clinically important for understanding of tumor lymphangiogenesis and identifying antimetastatic targets, only a handful of studies have analyzed M-LECPs in clinical human cancers. Two reports showed that blood-circulating LECPs were present in patients with small-cell lung26 and ovarian27 cancers but not in the blood of healthy individuals. These studies determined that the levels of circulating CD133+/VEGFR-3+ cells significantly correlated with disease stage, LN metastasis, and poor patient survival.26, 27 Another study showed differentiation of LECPs in vitro using human cord blood CD34+ cells activated by plasma from BC patients.25 Resultant LECPs with coexpressed myeloid and LEC markers acquired significant lymphangiogenic potential, as evidenced by de novo induction of corneal lymphovasculogenesis.25 Supporting existence of human lymphatic progenitors comes from recent studies, in which it was shown that activation of proinflammatory toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) in CD14+ monocytes induced the M-LECP phenotype.15 Collectively, these data show that M-LECPs exist in mice and humans, and they play a role in adult lymphangiogenesis induced by tumor or inflammation. However, none of these studies characterized M-LECPs in human clinical cancers or assessed the impact of tumor-mobilized M-LECPs on metastatic progression in patients.

Herein, we sought to close this knowledge gap by determining the levels of blood-circulating and tumor-mobilized M-LECPs in BC patients and characterizing the origin of these cells, their phenotype, and clinical significance with regard to lymph node status. The properties of human and mouse M-LECPs in clinical tumors and experimental cancer models were also compared. Potential mechanisms of macrophage-dependent lymphangiogenesis were addressed by evaluating TAM-produced soluble factors versus the self-autonomous role of M-LECPs. Finally, it was determined in orthotopic BC models whether inhibition of myeloid cell recruitment suppresses tumor M-LECPs and whether in vitro differentiated M-LECPs functionally affect the metastatic process.

A substantial number of BC patients were found to have a high level of M-LECPs in both blood and tumors. More important, we present herein original evidence that tumor M-LECP density strongly correlates with LN status of BC patients. Our findings also show that M-LECPs in clinical BC and experimental tumors in mice share similar structural and functional properties, including the ability to promote lymphatic metastasis. By quantifying absolute transcript numbers, it was determined that TAM-derived VEGF-C constitutes a minor fraction of total tumor mRNA, which is inconsistent with a predominant role in lymphatic formation. In contrast, the new in vitro system, which consisted of co-culturing macrophages and LECs under inflammatory conditions, supported the self-autonomous mechanism mediated by fusion of these two types of cells. This collective evidence establishes a new mechanistic concept of tumor lymphangiogenesis, demonstrates the significance of M-LECPs in clinical practice, and suggests experimental approaches to interrogate unique mechanisms of these cells in promoting lymphatic formation and LN metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Human Blood and Tissues

Human blood and tissue specimens from healthy donors (HDs) or patients diagnosed with BC were purchased from the Simmons Cancer Institute Tissue Bank (Springfield, IL). All samples were deidentified and collected in accordance with a protocol approved by the Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects. Blood from HDs was also purchased from Research Blood Components (Boston, MA), whereas HD mammary tissues and BC specimens were purchased from ILSBio Company (Baltimore, MD) or the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (Nashville, TN). All commercial blood and tissue were also deidentified.

Antibodies

Primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence and flow cytometry are listed in Table 1. Secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for Flow Cytometry and Immunofluorescence

| Antigen | Vendor | Catalog no. | Species specificity | Clone name | Concentration, μg/mL |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF | Flow cytometry | |||||

| CD3 | Abcam (Cambridge, UK) | ab5690 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 2 | N/A |

| CD4 | Abcam | ab133616 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 1.4 | N/A |

| CD8 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) | sc-7188 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 2 | N/A |

| CD11b | R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) | MAB16992 | Mouse anti-human (M) | 238439 | 5 | N/A |

| CD11b | BioXCell (West Lebanon, NH) | BE0007 | Rat anti-mouse (M) | M1/70 | 10 | N/A |

| CD14 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-1182 | Mouse anti-human (M) | UCH-M1 | 2 | N/A |

| CD18 | Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) | MA1810 | Mouse anti-human (M) | TS1/18.1.2.11.4 | 10 | N/A |

| CD38 | R&D Systems | MAB24041 | Mouse anti-human (M) | 240726 | 5 | N/A |

| CD56 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-106 | Mouse anti-human (M) | ERIC1 | 2 | N/A |

| CD68 | Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA) | MA5-13324 | Mouse anti-human (M) | KP1 | 2 | N/A |

| CD163 | Spring Biosciences (Cambridge, MA) | E18682 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | UN | N/A |

| CD204 | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) | HPA000272 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 2 | N/A |

| CD209 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-65740 | Mouse anti-human (M) | DC28 | 2 | N/A |

| HCLS1 | Sigma-Aldrich | HPA-019143 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | N/A |

| Ly6C | BioXCell | BE0203 | Rat anti-mouse (M) | Monts 1 | N/A | 5 |

| Ly6G | BioXCell | BE0075 | Rat anti-mouse (M) | RB6-8C5 | N/A | 5 |

| LYVE-1 | R&D Systems | AF2089 | Goat anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | 5 |

| Lyve-1 | AngioBio (San Diego, CA) | 11-034 | Rabbit anti-mouse (P) | N/A | 5 | 5 |

| MD2 | Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository (Manassas, VA) | NR-3887 | Mouse anti-human MD2 | U54.M.hMD2.9.1 | 10 | N/A |

| Pan-cytokeratin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-15367 | Rabbit anti-mouse/human (P) | N/A | 2 | N/A |

| Podoplanin | R&D Systems | AF3670 | Sheep anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | N/A |

| Podoplanin | BioXCell | BE0236 | Syrian hamster anti-mouse (M) | 8.1.1 | 10 | 5 |

| PROX1 | R&D Systems | AF2727 | Goat anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | N/A |

| PU.1 | Sigma-Aldrich | HPA044653 | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | N/A |

| TLR4 | Imgenex (San Diego, CA) | IMG-6307A | Rabbit anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | N/A |

| VE-cadherin | Thermo Fisher | PA6-19612 | Rabbit anti-mouse/human (P) | N/A | 10 | N/A |

| VEGFR-3 | R&D Systems | AF349 | Goat anti-human (P) | N/A | 5 | 5 |

| Vegfr-3 | R&D Systems | AF743 | Goat anti-mouse (P) | N/A | N/A | 5 |

HCLS, hematopoietic cell–specific Lyn substrate-1; IF, immunofluorescence; LYVE-1, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1; M, monoclonal IgG; MD2, myeloid differentiation 2; N/A, not applicable; P, polyclonal IgG; PROX1, prospero homeobox protein 1; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; UN, unknown; VE, vascular endothelial; VEGFR-3, VE growth factor receptor 3.

Isolation of CD14+ Monocytes from HDs and BC Patients

Human CD14+ monocytes were isolated from the whole blood of HDs and BC patients using standard methods. Blood was diluted 1:2 with 2% fetal bovine serum in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS), layered on top of Lymphoprep in SepMate tubes (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and centrifuged at 225 × g for 1 hour. Monocytes were isolated from the buffy coat using anti-CD14 IgG-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Gaithersburg, MD). The purity of the monocyte population was validated by staining with another antibody, and stained cells were confirmed to be >90% viable. Isolated cell populations with expected purity and viability were analyzed by flow cytometry and real-time quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR).

RT-qPCR Analysis

RNA was extracted using TRI-reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and reverse transcribed with the Revert Aid cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). Primers were designed based on coding sequence of human or mouse targets found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). All primer sequences are listed in Table 2. RT-qPCR was performed using GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) and the MasterCycle Realplex PCR machine (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Data were normalized as percentage of β-actin. Heat maps of the average fold change of target expression in BC monocytes compared with those in HDs were generated using Morpheus software from a public website (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA; https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus, last accessed December 5, 2018).

Table 2.

List of qPCR Primers for Human and Mouse Genes

| Primer∗ | Product size, bp | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human primers | |||

| ACTB† | 131 | 5′-TCCTCTCCCAAGTCCACACAGG-3′ | 5′-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATTC-3′ |

| COUPTFII | 129 | 5′-CGGGTGGTCGCCTTTATGG-3′ | 5′-ACAGGCATCTGAGGTGAACAG-3′ |

| ITGA9 | 89 | 5′-GACGCTGATCCCTTGCTATGA-3′ | 5′-CGGTGAAGAAGCCCGCTATC-3′ |

| LYVE1 | 150 | 5′-TGGGGATCACCCTTGTGAG-3′ | 5′-AGCCATAGCTGCAAGTTTCAAA-3′ |

| PDPN | 128 | 5′-AGAGCAACAACTCAACGGGA-3′ | 5′-TGTAGTCTCAGTGTCATCTTC-3′ |

| PROX1 | 130 | 5′-GGATGTTGAGTATTCAGTGGTGC-3′ | 5′-CTGGGAAATTATGGTTGCTCCT-3′ |

| TIE2 | 105 | 5′-TTAGCCAGCTTAGTTCTCTGTGG-3′ | 5′-AGCATCAGATACAAGAGGTAGGG-3′ |

| VEGFC† | 791 | 5′-ACTCTTCCCCAGCCAATGTG-3′ | 5′-ATCCTGGCTCACAAGCCTTC-3′ |

| VEGFR3 | 259 | 5′-GCACTGCCACAAGAAGTACCT-3′ | 5′-GCTGCACAGATAGCGTCCC-3′ |

| Mouse primers | |||

| Actb† | 153 | 5′-GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG-3′ | 5′-CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT-3′ |

| Cd34 | 157 | 5′-AAGGCTGGGTGAAGACCCTTA-3′ | 5′-TGAATGGCCGTTTCTGGAAGT-3′ |

| CoupTFII | 108 | 5′-TTCACCCATGTCAGCCGAC-3′ | 5′-GGCCTTGAGGCAGCTATACTC-3′ |

| Itga9 | 208 | 5′-AAGTGTCGTGTCCATACCAAC-3′ | 5′-GGTCTGCTTCGTAGTAGATGTTC-3′ |

| Lyve1 | 112 | 5′-CAGCACACTAGCCTGGTGTTA-3′ | 5′-CGCCCATGATTCTGCATGTAGA-3′ |

| Nrp2 | 67 | 5′-GCTGGCTACATCACTTCCCC-3′ | 5′-CAATCCACTCACAGTTCTGGTG-3′ |

| Pdpn | 159 | 5′-ACCGTGCCAGTGTTGTTCTG-3′ | 5′-AGCACCTGTGGTTGTTATTTTGT-3′ |

| Prox1 | 138 | 5′-GTGGTGCAACACGCAGATG-3′ | 5′-TGCCACCGTTTTTGTTCATGT-3′ |

| Tlr4 | 129 | 5′-ATGGCATGGCTTACACCACC-3′ | 5′-GAGGCCAATTTTGTCTCCACA-3′ |

| Tlr9 | 118 | 5′-ATGGTTCTCCGTCGAAGGACT-3′ | 5′-GAGGCTTCAGCTCACAGGG-3′ |

| Vegfc† | 160 | 5′-GAGGTCAAGGCTTTTGAAGGC-3′ | 5′-CTGTCCTGGTATTGAGGGTGG-3′ |

| Vegfr2 | 133 | 5′-TTTGGCAAATACAACCCTTCAGA-3′ | 5′-GCAGAAGATACTGTCACCACC-3′ |

| Vegfr3 | 182 | 5′-CGGGCTACCTGTCCATCATC-3′ | 5′-TGTCACAGCTGCTGCCTTTA-3′ |

COUPTFII, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor 2; ITGA9, integrin subunit alpha 9; LYVE1, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1; Nrp, neuropilin; PDPN, podoplanin; qPCR, real-time quantitative PCR; Tie2, angiopoietin-1 receptor; Tlr, toll-like receptor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Primers were designed based on human or mouse coding sequence of targets found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. All primers were validated using human or mouse universal cDNA. Primers were confirmed to exclusively detect species-specific cDNA.

Primers that were used to design TaqMan probes for absolute transcript copy number assay.

Multicolor Flow Cytometry of Human Blood

Blood from HDs and BC patients was prepared as described above. After isolating cells from the buffy coat and blocking Fc receptor, cells were costained with primary antibodies for CD14 and VEGFR-3, LYVE-1, and PDPN (1 hour incubation on ice, followed by 30 minutes of incubation with 488-, phosphatidylethanolamine-, and 647-conjugated anti-mouse, anti-goat, and anti-sheep secondary antibodies). Stained cells were fixed for 10 minutes with 1% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and analyzed using an AccuriC6 flow cytometer (BD Accuri Cytometers, San Jose, CA) and FlowJo software version 10 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). CD14+ cells were gated from the total buffy coat population, and the percentage of CD14+ cells coexpressing lymphatic markers was determined for duplicates of each sample.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Frozen tumors were divided into section (8 or 20 μm thick), fixed with acetone, and rehydrated in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 before incubation with Image-iT FX signal enhancer (Thermo Fisher) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Primary antibodies, diluted 1:100 in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (immunohistochemistry buffer), were incubated with tissues overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed for 10 minutes in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. Secondary antibodies, diluted 1:100 in immunohistochemistry buffer, were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Slides were washed and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature with 2 μg/mL Hoechst stain (Thermo Fisher) and then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 for 10 minutes, and mounted in Prolong Gold medium (Thermo Fisher). Images were acquired on an Olympus BX41 microscope equipped with a DP70 digital camera and DP Controller software version 1.15 (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope equipped with Airyscan and analyzed with Zen Blue software version 2.6 (Carl Zeiss GbmH, Jena, Germany).

Quantification of M-LECPs in BC and Healthy Breast Tissues

Tissues were sorted into healthy samples, LN-negative tumor samples, and LN-positive tumor samples. Healthy and malignant human breast tissues were costained with antibodies to human CD68 and LYVE-1. Four images per section were captured at ×200 magnification. All CD68+ and CD68+/LYVE-1+ monocytes were counted per field. The number of double-positive cells was divided by the total number of CD68+ monocytes to calculate the percentage of M-LECPs from total.

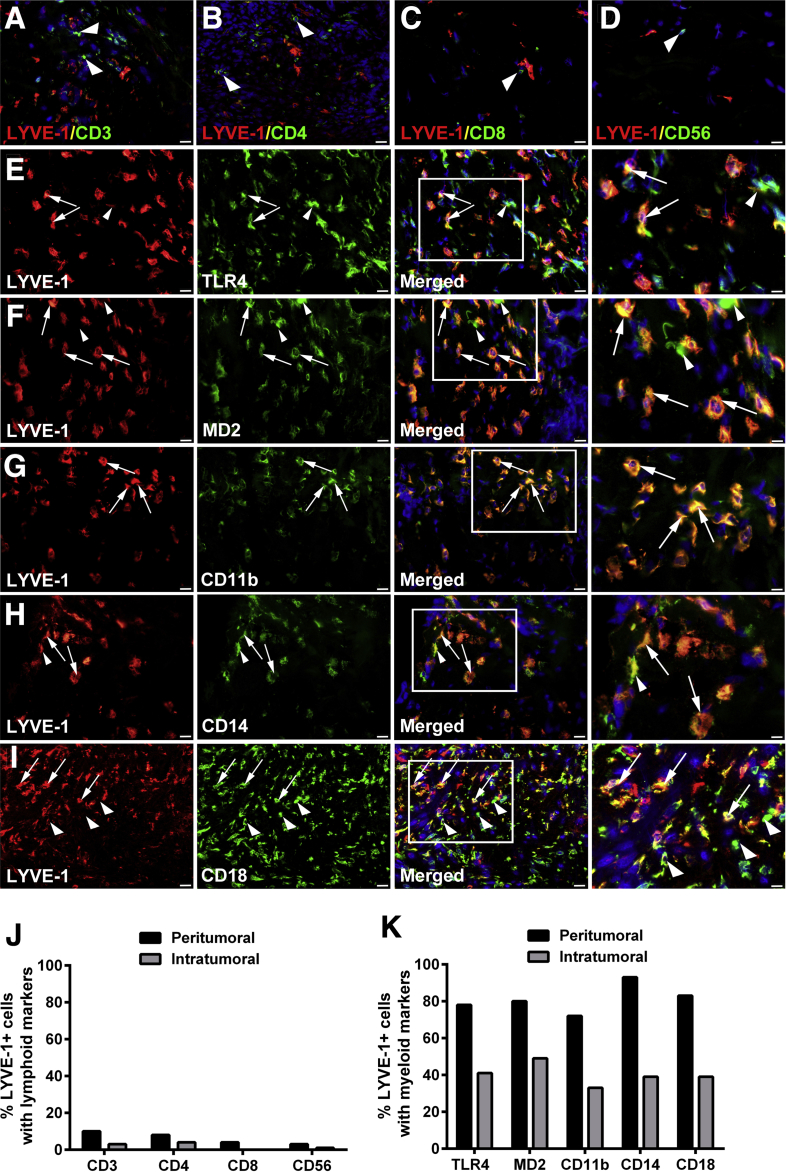

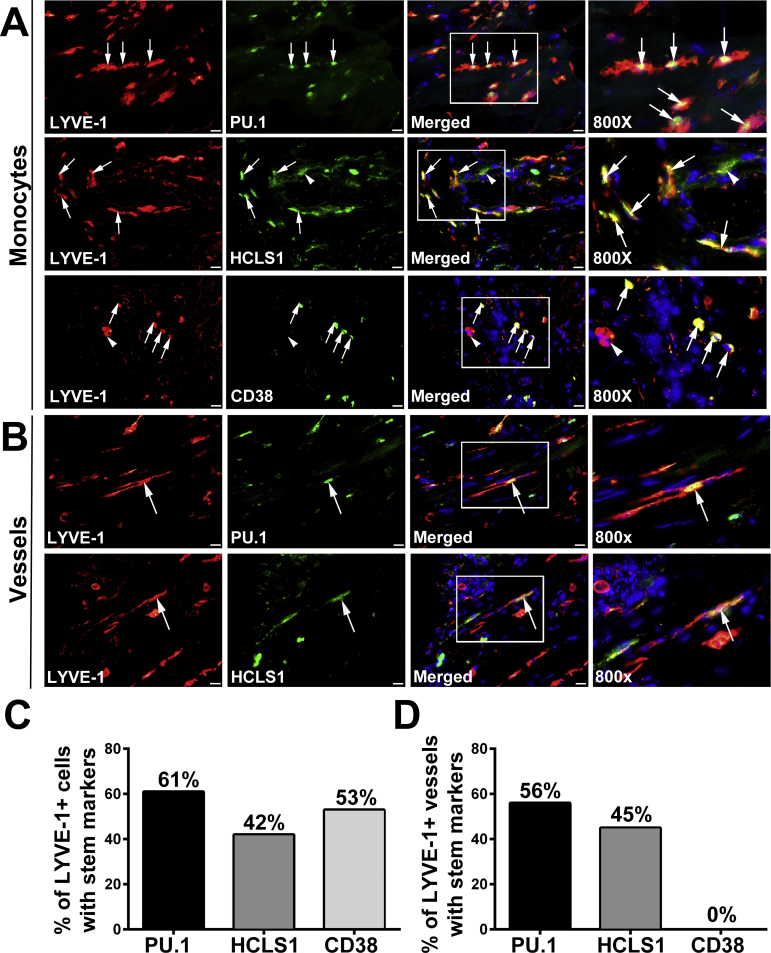

Quantification of Lymphoid, Myeloid, and Stem/Progenitor Markers Expressed in LYVE-1+ Cells of Clinical BC Tissues

Human BC specimens with infiltrated M-LECPs were costained for LYVE-1 and lymphoid markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD56), myeloid markers [TLR4, myeloid differentiation protein 2 (MD2), CD11b, CD14, and CD18], and stem/progenitor markers [PU.1, hematopoietic cell–specific Lyn substrate-1 (HCLS1), and CD38]. Colocalization of each marker with LYVE-1 was determined for 100 cells expressing LYVE-1 identified in at least five specimens. Results are presented as the percentage of LYVE-1+ cells expressing each analyzed marker.

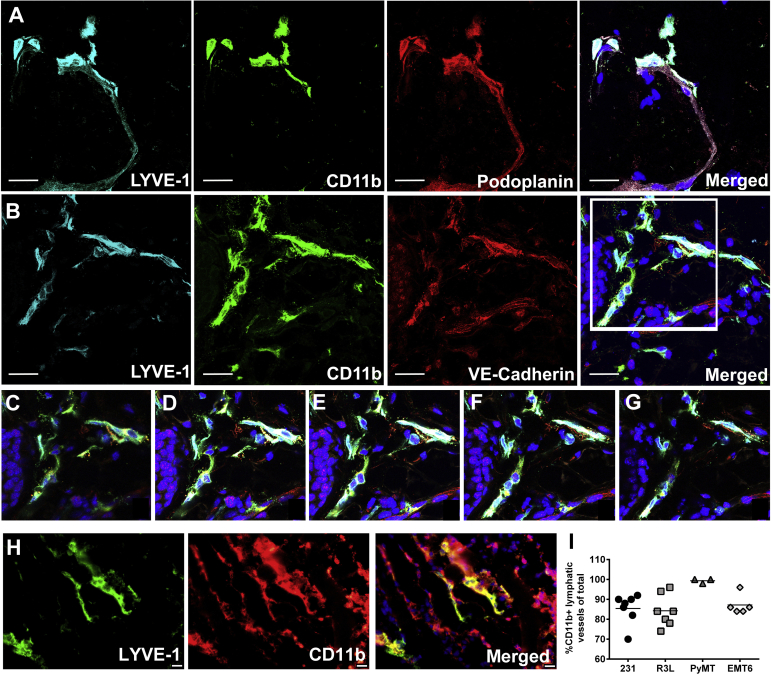

Quantification of LVs Positive for Stem/Progenitor and Myeloid Markers in Human Tissues and Mouse Tumors

Human tissues were costained with antibodies to LYVE-1 and PU.1, HCLS1, CD38, CD68, CD11b, or CD14. Expression of stem/progenitor or myeloid markers was assessed for 100 vessels expressing LYVE-1 identified in five randomly selected specimens containing M-LECPs. The percentage of double-positive vessels was determined by dividing the number of LYVE-1+ vessels coexpressing each marker by total number of lymphatic vessels. Expression of macrophage markers in lymphatic vessels in mouse-grown MD Anderson–metastasis breast–231 (MDA-MB-231), 824R3L (R3L), experimental mammary tumor 6 (EMT6), and mouse mammary tumor virus–polyoma middle T (MMTV-PyMT) tumors was similarly assessed.

Culture of Human and Mouse Breast Carcinoma Cell Lines

Human breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and EMT6, were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and engineered for expression of luciferase, as described previously.21, 28 Mouse BC cell lines, R3L and MMTV-PyMT BC, were generous gifts from Susan Rittling (Forsyth Institute, Cambridge, MA) and David DeNardo (Washington University, St. Louis, MO), respectively. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/L of glutamine, 1 mmol/L of sodium pyruvate, and 1 mmol/L of nonessential amino acids at 37°C in 10% CO2. Cells were passaged biweekly by incubating for 5 minutes at 37°C in 0.5 mmol/L of EDTA in Dulbecco’s PBS, followed by 0.25% of trypsin. Cells were routinely tested for Mycoplasma by e-Myco Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Bulldog Bio, Portsmouth, NH). The MDA-MB-231-Luc line was authenticated by ATCC. EMT6-Luc, R3L, and MMTV-PyMT were screened by Impact III testing through RADIL (Columbia, MO) for mouse pathogens and determined to be negative.

Tumor Induction in Xenograft and Syngeneic Orthotopic BC Mouse Models

Tumor growth of orthotopically implanted BC lines was described previously.21, 29 Briefly, 4 × 106 MDA-MB-231-Luc cells, 1 × 106 EMT6-Luc or R3L cells, or 0.5 × 106 MMTV-PyMT cells were suspended in a solution of 50% Matrigel and implanted into the mammary fat pad of 5- to 6-week–old female severe combined immunodeficiency (Taconic, Rensselaer, NY), BALB/c (Envigo, Indianapolis, IN), B6129PF2/J (Jackson, Bar Harbor, ME), or C57BL/6 (Envigo) mice, respectively. Every 2 to 3 days, perpendicular tumor diameters were measured by digital calipers and used to calculate tumor volume, according to the following formula: volume = Dd2π/6, where D and d equal to larger and smaller diameters, respectively. Animal care was in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of CD11b+ Cells Isolated from Xenograft Tumors

Orthotopic MDA-MB-231-Luc tumors harvested at a volume of 500 mm3 were digested by collagenase type III (225 U/mL) and hyaluronidase (100 U/mL), both from Sigma-Aldrich. Tumor-associated CD11b+ cells were isolated using anti-CD11b IgG-conjugated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). After blocking Fc, cells were incubated with 5 μg/mL of anti-Ly6C, anti-Ly6G, anti–Vegfr-3, anti–Lyve-1, and anti-podoplanin antibodies for 1 hour on ice, followed by incubation with secondary 488- and 647-conjugated antibodies. Marker expression was analyzed using AccuriC6 flow cytometer and FlowJo software. Data are expressed as the mean percentages of marker expression per group ± SEM (N = 5). Peritoneal CD11b+ macrophages were collected from normal mice, as previously described,30 and used as control cells representing mature macrophages. Gates were set using negative controls. Positive staining was identified by subtracting background resulting from non-specific binding of secondary antibodies alone.

Isolation of Tumor Podoplanin-Positive and Podoplanin-Negative CD11b+ Myeloid Populations

CD11b+ cells, isolated from MDA-MB-231-Luc tumors, were stained with anti-Pdpn antibody and sorted for Pdpn-positive and Pdpn-negative subpopulations using the Becton-Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ) FACSAria II high-speed cell sorter. Sorted cell populations were analyzed for expression of the lymphatic signature genes by RT-qPCR, as described above.

Determination of Absolute Copy Number of Human and Mouse Tumor-Derived VEGFC Using qPCR TaqMan Method

Total RNA was isolated from orthotopic MDA-MB-231 tumors and converted to cDNA using Superscript ViLo kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Species specificity of primers for VEGFC and β-actin (Table 2) was tested using human and mouse universal cDNA templates, followed by agarose gel analysis of products. Custom TaqMan primer/probe sets were designed for each species-specific primer set and synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific. Standards for human or mouse VEGF-C and β-actin (Origene, Rockville, MD) were produced by serial dilution of plasmids containing full-length cDNA of each target. Total plasmid in each standard ranged from 30 up to 300,000 copies of each target. The standard curve was constructed by plotting cycle threshold (CT) values against log values for transcript copy number at each point. The copy number of mouse and human VEGFC transcripts in the same tumor samples was calculated using a regression equation, where an R2 value ≥0.95 was considered acceptable. Data are presented as an absolute number of mouse and human transcript copies in each tumor sample (N = 10) normalized per 1000 copies of human β-actin. Assays were performed in triplicate, and tests for plasmid dilutions were used to prepare standards, repeated twice.

In Vitro Model for Myeloid-Lymphatic Endothelial Cell Fusion

Rat lymphatic endothelial cells (RLECs)31 and macrophage cell line, RAW264.7, were transduced with lentivirus to constitutively express red fluorescent protein (RFP) or green fluorescent protein (GFP), respectively, referred to as RLEC-RFP and RAW-GFP. RLEC-RFP cells (35,000) were seeded onto 0.2% gelatin-coated slides in standard growth medium and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C. Slides were washed three times with Dulbecco’s PBS and 10,000 RAW-GFP cells seeded on top of RLEC-RFP cells in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing vehicle or 3 nmol/L of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and co-cultured for 4 to 6 days. Slides were washed with Dulbecco’s PBS, followed by a 5-minute incubation with 2 μg/mL of Hoechst stain to visualize nuclear DNA. Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and mounted in Prolong Gold mounting medium. Images were captured as described above.

The Effect of Inhibiting CSF1 on M-LECP Recruitment and Lymphatic Vessel Density in Vivo

Treatment of mice harboring MMTV-PyMT tumors with a colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibitor PLX3397 was performed as previously described.32 Briefly, 80-day–old mice were sorted into two groups (N = 4 each) and fed chow containing PLX3397 (40 mg/kg per day) or vehicle control for 15 days. Tumors were harvested and evaluated for macrophage recruitment, presence of M-LECPs, and lymphatic vessel density, as described above.

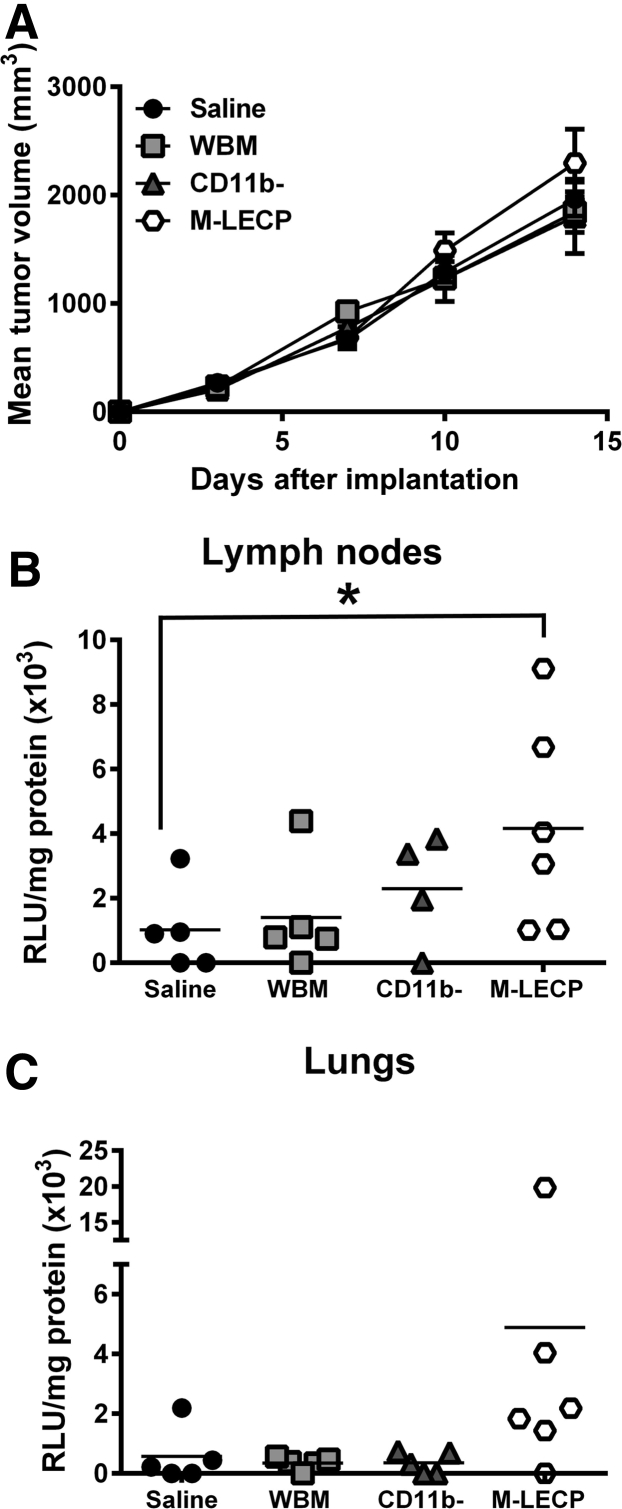

Analysis of Prometastatic Activity of Differentiated M-LECPs Generated from BM in Vitro

Female BALB/c mice were implanted with EMT6-Luc tumors, as previously described.15 One day after tumor implantation, mice were sorted into groups and injected intravenously with the following: i) saline; ii) 1 × 106 of unfractionated naïve BM cells; iii) 1 × 106 of naïve CD11b− cells; or iv) 1 × 106 of CD11b− cells culture differentiated with 10 ng/mL of mouse CSF1 for 3 days, followed by a 3-day treatment with 3 nmol/L of LPS.15 Female BALB/c mice were donors for all BM cell populations. BM cell isolation of myeloid precursors using magnetic beads was performed as previously described,15 with the following modifications: culture-differentiation medium was low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium without phenol red that contained 10% fetal bovine serum and standard supplements; and CD11b-negative cells were used as a source of M-LECPs because this fraction was determined to have a higher percentage of early precursors with increased differentiation potential. Differentiated cells were tested by flow cytometry and determined to be 90% to 100% positive for CD11b, TLR4, Lyve-1, podoplanin, and integrin subunit alpha 9 (Itga-9) on the day of injection to tumor-bearing mice. Tumor growth was monitored two to three times per week, and mice were euthanized when their tumor burden was 1800 mm3. Ipsilateral LNs and lungs were collected and homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (Promega) containing protease inhibitors. Luciferase substrate (50 μL) was mixed with lysates (20 μL) followed by luminescence detection using a luminometer (Berthold, Oak Ridge, TN). Extracts with luciferase activity of 800 relative light units (RLU)/second above background were considered positive for metastases. Data are expressed as the mean RLU/second ± SEM from duplicate readings normalized per mg of total protein determined by Bradford assay.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of differences among groups was determined by a t-test or U-test using Prism software version 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Statistical significance between LN− and LN+ groups was determined by a Fisher's exact test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Circulating M-LECPs Are Largely Absent in HDs But Found at High Levels in the Blood of BC Patients

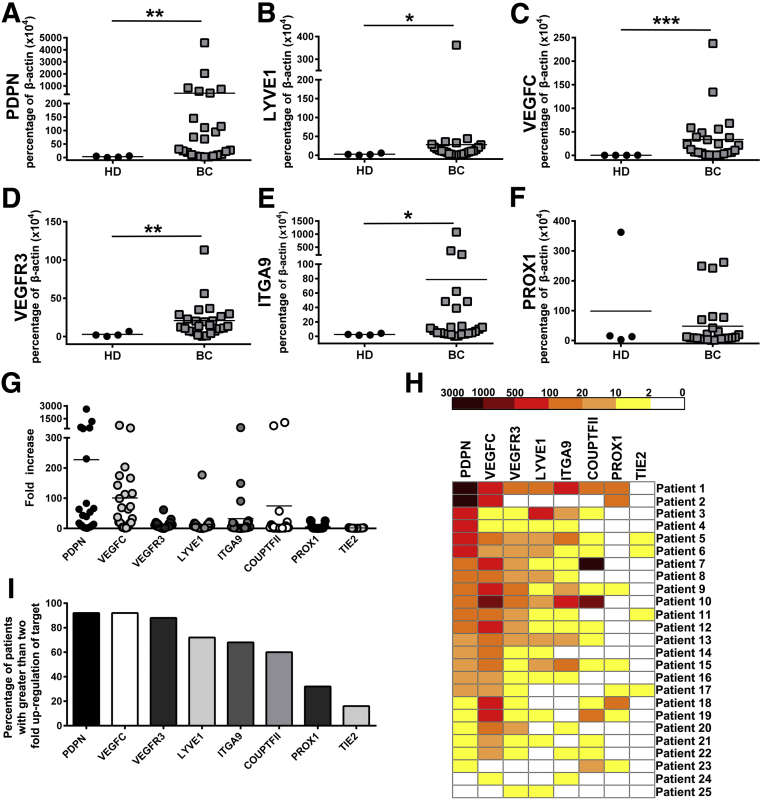

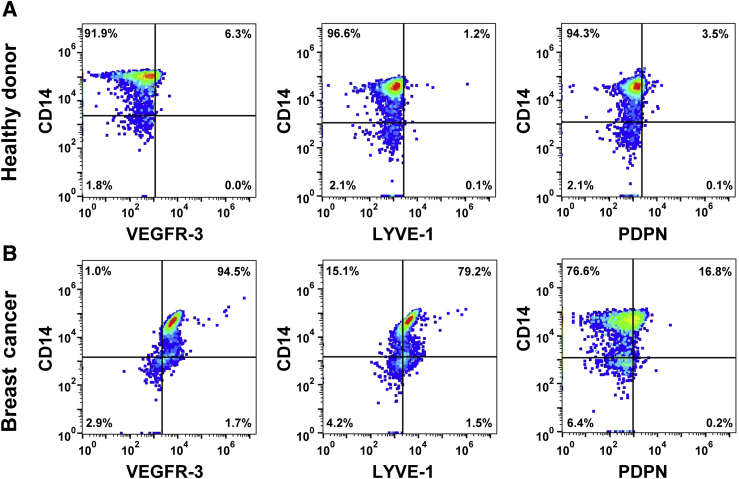

We previously described M-LECP recruitment to LPS-inflamed diaphragms and their significant contribution to inflammatory lymphangiogenesis.30 Several recent studies demonstrated that lymphatic progenitors circulating in the blood of cancer patients correlate with LN metastasis and poor survival.26, 27 These findings suggested that lymphatic metastasis-prone BC2 produces soluble factors that induce generation of M-LECPs in the BM and promote their mobilization to the tumor. We, therefore, hypothesized that M-LECPs should be detected at higher frequency in the blood of BC patients than HDs. RT-qPCR and flow cytometry were used to compare expression of LEC markers in circulating CD14+ monocytes isolated from blood samples of HDs (N = 4) or patients with BC of grade 2 to 4 (N = 25). Using an in-house RT-qPCR gene array, baseline expression of LEC-specific genes was first determined in monocytes from HDs. This analysis showed low or no expression of lymphatic markers in HD monocytes (Supplemental Table S1), indicating that M-LECPs are largely absent in the blood under cancer-free conditions. In contrast, monocytes from BC patients expressed high levels of PDPN, LYVE-1, VEGF-C, VEGFR-3, ITGA-9, and prospero homeobox protein 1 (PROX-1) (Figure 1, A–F, Figure 2, and Supplemental Table S2) with all differences, except PROX1, significant (P ≤ 0.03). Monocytes expressing LEC proteins, VEGFR-3, LYVE-1, and PDPN ranged from 1% to 6% in HDs, a level that increased from 16% and up to 94% in BC patients (Figure 2). In addition to these three major markers, monocytes from multiple patients demonstrated highly elevated levels of other LEC markers, such as ITGA-9 and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor 2 (COUPTF2) (Figure 1, H and I). In contrast, blood vascular marker angiopoietin-1 receptor (TIE2) was elevated only twofold for a small fraction of samples (Figure 1, G–I). Significant increase in circulating monocytes with LEC markers in BC patients suggests that tumors prompt release of myeloid-lymphatic progenitors to the blood to support tumor demands for vascular formation.

Figure 1.

Myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) progenitors are present at high levels in the blood of breast cancer (BC) patients but absent in healthy donors (HDs). CD14+ monocytes were positively isolated from blood samples obtained from BC patients or HDs. A–F: RNA was extracted from isolated cells and analyzed by real-time quantitative RT-PCR for expression of the LEC markers podoplanin (PDPN; A), lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE1; B), vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGFC; C), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR3; D), integrin subunit alpha 9 (ITGA9; E), and prospero homeobox protein 1 (PROX1; F). Expression of each gene was determined in triplicate and reported as a percentage of β-actin. Significant differences in gene expression for monocytes from HDs and cancer patients were determined by U-test. G: Fold increase of individual LEC markers for BC patient monocytes compared with HDs. H: Heat map demonstrating up-regulated LEC markers in circulating monocytes from all 25 BC patients. I: Percentage of patients with LEC transcripts in monocytes increased by at least twofold. N = 25 (A–F, BC patients); N = 4 (A–F, HDs). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Circulating monocytes express lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC)–specific markers. Buffy coat was fractionated from whole blood of healthy donors (HDs; A) and breast cancer (BC) patients (B) and costained with antibodies to identify CD14+ monocytes that also stain with lymphatic markers vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3), lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1), and podoplanin (PDPN; identified in the upper right quadrant of each dot plot). Samples were analyzed in duplicate, with SEM differences of <5% between replicates. Representative dot plots for each antibody combination are shown. N = 3 (A, HDs); N = 5 (B, BC patients).

The Density of Tumor-Recruited M-LECPs Significantly Correlates with Lymphatic Metastasis

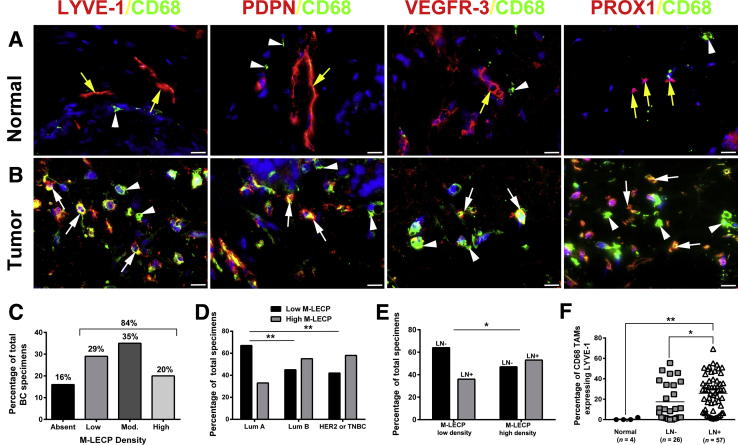

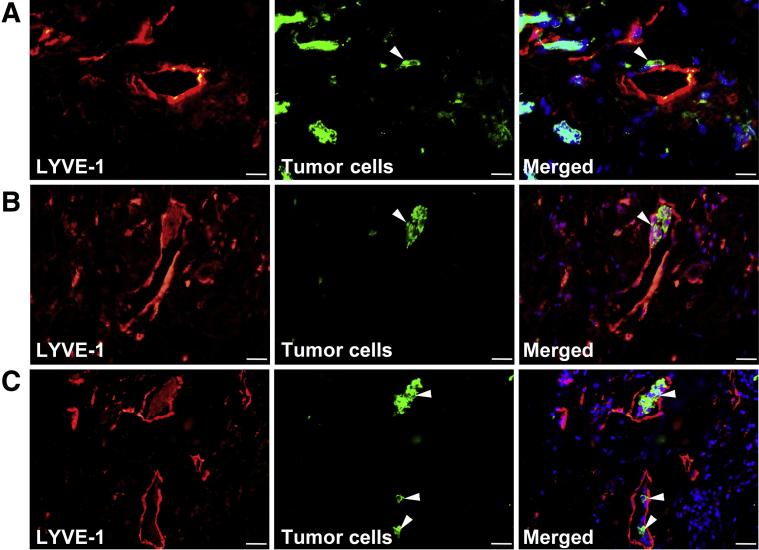

M-LECPs have been implicated in both inflammatory30 and tumor lymphatic formation,33 but their direct contribution to lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis in clinical BC has not been examined. Clinical BC specimens (N = 95) and healthy breast tissues (N = 4) were analyzed for the presence of M-LECPs, defined as individual cells coexpressing CD68 and at least one LEC marker (LYVE-1, PDPN, VEGFR-3, or PROX-1). Healthy breast tissues contained LYVE-1+ lymphatic vessels and CD68+ resident macrophages, but few double-positive cells and no double-stained vessels (Figure 3A). In contrast, 84% of tumor specimens contained double-positive M-LECPs (Figure 3, B and C), including approximately 20% with high density (≥20 cells/field). Consistent with the close association between M-LECPs and metastasis, aggressive BC subtypes (ie, negative epidermal growth factor receptor 2 and triple-negative BC) were more likely to have a high density of lymphatic progenitors than a less metastatic luminal A group (58% versus 33%; P = 0.006) (Figure 3D). M-LECPs were more prevalent in LN+ patients compared with the LN-negative group (25% versus 17.4%; P = 0.05) (Figure 3E). However, the density of M-LECPs in both tumor groups was substantially higher than in healthy breast tissues, where only 0.5% of CD68+ macrophages expressed LEC markers (Figure 3F). More important, the density of tumor-recruited M-LECPs significantly correlated with LN status (P = 0.02) (Figure 3F). Increased LVD in M-LECP–enriched tumors often corresponded with tumor cell attachment to lymphatic vessels (Figure 4A), penetration of the lymphatic barrier (Figure 4B), and lymphovascular invasion by tumor clusters (Figure 4C). These collective data show, for the first time, that M-LECPs are present in clinical breast cancers and density of tumor M-LECPs correlates with aggressive, prometastatic BC subtypes as well as patient node status.

Figure 3.

Myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitor (M-LECP) density in clinical breast cancer (BC) strongly correlates with lymphatic metastasis. A and B: Normal (A) and malignant (B) human breast tissues were costained for the macrophage marker CD68 (green) and lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) proteins lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1), podoplanin (PDPN), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (VEGFR-3), or prospero homeobox protein 1 (PROX1; all red). Labels above images indicate the color for each marker. Yellow arrows point to lymphatic vessels. White arrows and arrowheads point to CD68+ cells that express or lack lymphatic markers, respectively. Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. The percentage of M-LECPs (ie, CD68+/LYVE-1+ cells) from total macrophages was determined for lymph node (LN)− and LN+ BC specimens as well as healthy breast tissues. Low, moderate (Mod.), and high M-LECP density was defined as 0 to 5, 6 to 19, and ≥20 double-positive cells per field, respectively. C–E: Distributions of M-LECP densities among all analyzed BC tumors (C), specimens sorted by tumor subtype classification (D), and comparison between LN− and LN+ groups (E) are shown. F: The mean M-LECP density quantified per section is presented by black circles (normal breast), gray squares (LN− tumor), or white triangles (LN+ tumor), with black bars indicating the mean density per group. N = 26 (E, LN− group); N = 57 (E, LN+ group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (determined by Fisher's exact test, D and E, or t-test, F). Scale bar = 20 μm (A and B). Original magnification, ×600 (A and B). Lum A, luminal A subtype of BC; Lum B, luminal B subtype of BC; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Figure 4.

Myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitor (M-LECP)–enriched breast cancer (BC) displays lymphovascular invasion. Human BC specimens were costained for lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1; red) and markers of tumor cells (green). In M-LECP–enriched tumors, various stages of lymphovascular invasion were observed. Examples of selected striking images include the following: attachment of tumor cells to the basal side of the LYVE-1+ vascular wall and local degradation of the vascular structure (A), penetration of the tumor cluster identified by anticytokeratin antibody through the LYVE-1–positive monolayer toward the lumen of the vessel (B), and a growing colony of cytokeratin-positive tumor cells inside the lumen of a LYVE-1+ vessel (C). Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. White arrowheads indicate tumor cells that have invaded into lymphatic vessels. Scale bar = 20 μm. Original magnification: ×600 (A); ×400 (B and C).

Lymphatic Progenitors Recruited to Clinical BC Originate from the Myeloid Lineage

Lymphatic cell progenitors are generally derived from BM myeloid precursors,34 but the origin of M-LECPs in clinical human cancers is unknown. Alternative sources of human LECPs included BM mesenchymal stem cells35 and multipotent progenitors lacking myeloid determination.36 Breast tumor tissue sections were costained with antibodies to LYVE-1 and specific markers for lymphoid or myeloid cells (Figure 5). Markers of T lymphocytes (CD3, CD4, and CD8) and natural killer cells (CD56) were detected for ≤10% of LYVE-1+ cells (Figure 5, A–D and J), whereas the B-cell marker, CD19, was completely absent (data not shown). In contrast, the vast majority (93%) of LYVE-1+ cells expressed all examined monocyte/macrophage markers (TLR4, MD2, CD11b, CD14, and CD18) (Figure 5, E–I and K). Noteworthy, MD2, CD11b, CD14, and CD18 are essential coreceptors for TLR4, and coexpression of these proteins by M-LECPs suggests their functional requirement for generation of lymphatic progenitors from BM myeloid precursors.15, 30, 34 The macrophage nature of tumor LECPs was also confirmed by strong expression of M2-type macrophage markers, CD204, CD209, and CD163, on LYVE-1+ cells (Figure 6). Taken together, these data support findings from multiple experimental models34 identifying hematopoietic-myeloid precursors as the primary source of M-LECPs.

Figure 5.

Tumor myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors are derived from the myeloid lineage. A–D: Human breast cancer specimens were costained with antibodies against lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1) and markers for lymphoid cell lineage CD3 (A), CD4 (B), CD8 (C), and CD56 (D). E–I: Specimens were also costained for LYVE-1 and markers of myeloid-macrophage lineage toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4; E), MD2 (F), CD11b (G), CD14 (H), and CD18 (I). White boxed areas in images in the third panels are shown in higher magnification in the fourth panels. The white arrows point to macrophages positive for LYVE-1. The white arrowheads highlight macrophages and lymphocytes negative for LYVE-1. Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. The frequency of LYVE-1 expression in cells costained with lymphoid (J) and myeloid (K) markers was quantified in 100 randomly selected LYVE-1+ cells identified in five tumor specimens. The percentages of peritumoral and intratumoral LYVE-1+ cells positive for markers of each of the examined lineages and located in the tumor-adjacent fat and inside the tumor mass, respectively, are presented. Original magnification: ×400 (A–D and E–I, first, second, and third panels); ×800 (E–I, fourth panels).

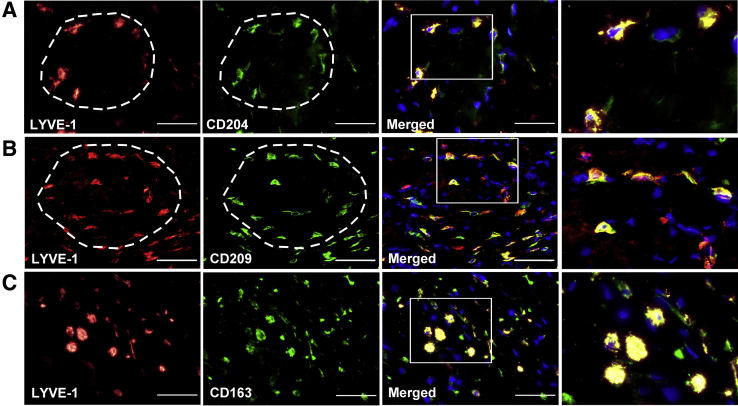

Figure 6.

Tumor myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors (M-LECP) are a subset of M2-type macrophages. Tumor sections were costained with antibodies against lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1) and CD204 (A), CD209 (B), or CD163 (C), typically used to identify M2-type tumor-associated macrophages. Circular arrangement of M-LECP cells [LYVE-1 and CD204/CD209 dual-positive clusters, indicated by white dashed line (A and B)] is reminiscent of nascent formation of a lymphatic vessel. Spatial organization of M-LECPs costained with other macrophage markers was observed in multiple tumor samples. White boxed areas in images in the third panels are shown in higher magnification in the fourth panels. Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. Scale bar = 100 μm. Original magnification: ×400 (A–C, first, second, and third panels); ×800 (A–C, fourth panels).

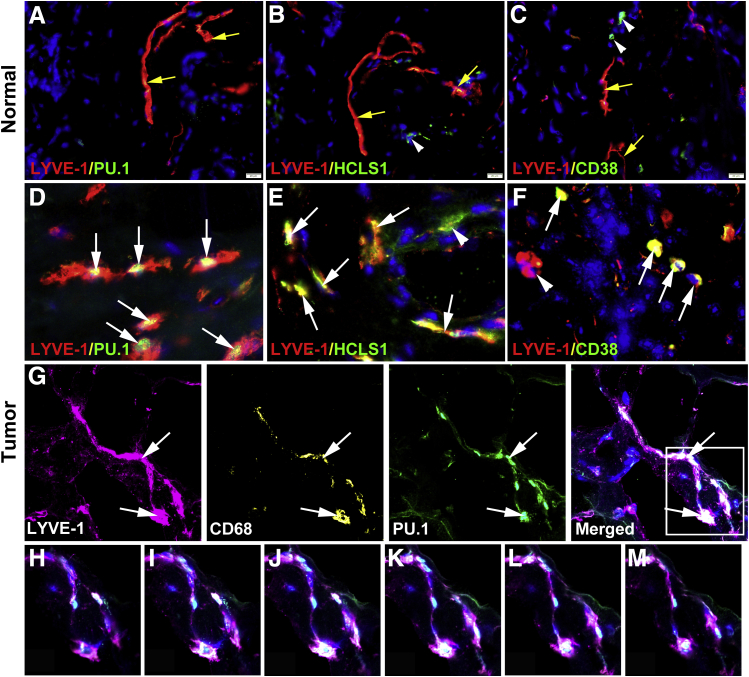

M-LECPs Are Immature Myeloid Cells Derived from Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells

Presence of myeloid-lymphatic cells in the blood of cancer patients but not healthy individuals (Figures 1 and 2) strongly suggests that these cells are recent progeny of the stem/progenitors reprogrammed to increase tumor lymphangiogenesis. This implies that tumor-infiltrating LYVE-1+ cells with macrophage characteristics are derived from immature BM myeloid progenitors rather than resident macrophages. The expression of specific stem/progenitor markers was determined in LYVE-1+ cells in normal mammary and BC tissues. The following markers were selected: i) PU.1, a master regulator determining the fate of all myeloid lineages in the BM;37, 38, 39 ii) HCLS1, an actin-binding protein that regulates migration and chemotaxis of early BM progenitors;40, 41 and iii) CD38, a specific marker of early common progenitors for hematopoietic and vascular lineages.42 In healthy breast tissues, PU.1 was absent from both macrophages and lymphatic vessels (Figure 7), and HCLS1 and CD38 were occasionally expressed but did not colocalize with LYVE-1+ vessels (Figure 7). In contrast, BC tissues had substantially higher density of PU.1+, HCLS1+, and CD38+ cells, and nearly half of these cells coexpressed LYVE-1 (Figure 7 and Supplemental Figure S1). Moreover, 40% to 60% of LVs were positive for these stem cell markers (Supplemental Figure S1), suggesting integration of lymphatic progenitors into existing vessels, as previously described for mouse inflammatory models.30, 34 Taken together, abundant expression of PU.1, HCLS1, and CD38 in both tumor lymphatic vessels and infiltrating M-LECPs strongly suggests that this cell population is derived from early myeloid precursors that differentiated from hematopoietic stem cells.

Figure 7.

Tumor myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors are bone marrow–derived myeloid progenitors. A–F: Healthy (A–C) and malignant (D–F) breast tissues were costained for lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1; red) and stem cell markers PU.1 (A and D), hematopoietic cell–specific Lyn substrate-1 (HCLS1; B and E), and CD38 (C and F), all shown in green to determine the maturation status of LYVE-1+ cells. Yellow arrows point to normal LYVE-1+ vessels that do not express stem/progenitor markers. White arrowheads highlight rare LYVE-1–negative CD38+ cells detected in normal breast. White arrows indicate both cells and vessels double positive for LYVE-1 and stem cell markers in tumor tissues. Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. G–M: For confocal analysis, human breast cancer specimens (20 μm thick) were costained with antibodies to LYVE-1, CD68, and PU.1 and analyzed by Z-stack (G); the white boxed area and arrows in the merged image in G indicate the individual two-dimensional images separated by 2 μm that are shown in Z-stack panels below (H–M). Note high intensity of PU.1 expression in the nucleus of the lymphatic endothelial cell coexpressing LYVE-1 and CD68 (I–L). Supplemental Video S1 shows three-dimensional reconstruction of this lymphatic vessel with integrated CD68 and PU.1. Scale bar = 20 μm (A–F). Original magnification: ×400 (A–C); ×800 (D–F); ×300 (G); ×600 (H–M).

Colocalization of lymphatic, myeloid, and stem markers in tumor lymphatic vessels was confirmed by confocal microscopy. Tumors were cut into sections (20 μm thick) and analyzed by Z-stack images taken 1 μm apart. Specimens were stained with antibodies to LYVE-1, CD68, and PU.1, markers of different lineages and maturation status. Figure 7 shows an example of a lymphatic vessel with colocalized markers identified in the merged panel. Analysis of Z-stack images (Figure 7) shows coexpression of all three markers in endothelial cells lining the vessel as well as correct cellular localization (ie, cytosol and nucleus for CD68 and PU.1, respectively). PU.1 staining intensity was particularly strong (Figure 7), which is expected for a single nucleus visualized in Z-stack images. A video demonstrating rotation of this vessel displays all three markers throughout the 20-μm tissue section (Supplemental Video S1). This reconstruction shows that mixed myeloid-lymphatic-stem/progenitor protein expression in tumor lymphatic vessels is not an insertion of isolated macrophages into the wall of the vessel but a true mixture of cellular contents of TAMs and LECs. This finding is consistent with our previous reports in mouse models30, 34 demonstrating donation of multiple proteins specific to M-LECPs to endothelial cells in tumor lymphatics.

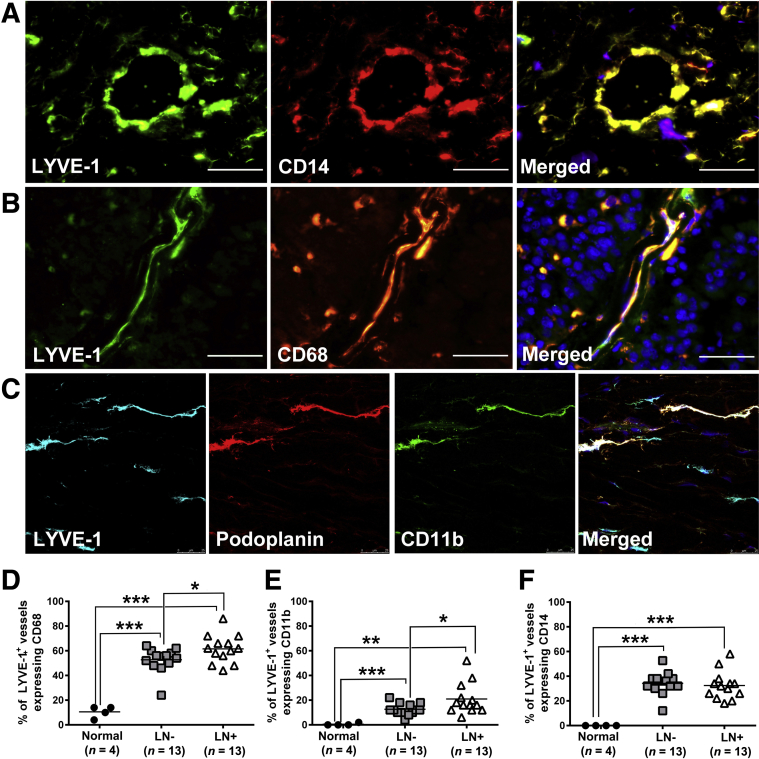

LV-Integrated M-LECPs Correlate with LVD and Lymph Node Status

Although M-LECP integration into LVs has been reported in several mouse models,30, 34 this phenomenon has not been examined in clinical cancers. Herein, we report, for the first time, that a significant portion of BC lymphatic vessels express distinct myeloid markers CD14, CD11b, and CD68 (Figure 8), indicating integration of M-LECPs. Confocal microscopy of triple-stained BC tissues revealed clear conformity between LEC-specific marker LYVE-1 or PDPN and the myeloid marker, CD11b (Figure 8). This finding contrasts results for LVs of healthy breast tissue, which are devoid of myeloid markers (Figure 3A). More important, the density of LVs with integrated M-LECPs was statistically higher for tumors in LN+ versus the LN-negative group (P = 0.04 to 0.001) (Figure 8). These findings are consistent with our proposed concept that integration of M-LECPs into existing LVs precedes sprouting and is critical for generation of new lymphatic vessels.

Figure 8.

Integration of myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors into tumor lymphatic vessels correlates with lymphatic metastasis. A and B: Tumor lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE-1)–positive vessels express myeloid-specific markers CD14 (A) and CD68 (B). C: Coexpression of LYVE-1, podoplanin, and CD11b in lymphatic vessels was also observed in Z-stack images using confocal microscopy. Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. D–F: The percentages of LYVE-1+ vessels coexpressing CD68 (D), CD11b (E), and CD14 (F) were quantified in healthy human breast tissues as well as lymph node (LN)–negative and LN-positive breast cancer specimens. The black bars indicate the mean of double-positive vessels in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (determined by t-test). Scale bar = 100 μm (A–C). Original magnification, ×400 (A–C).

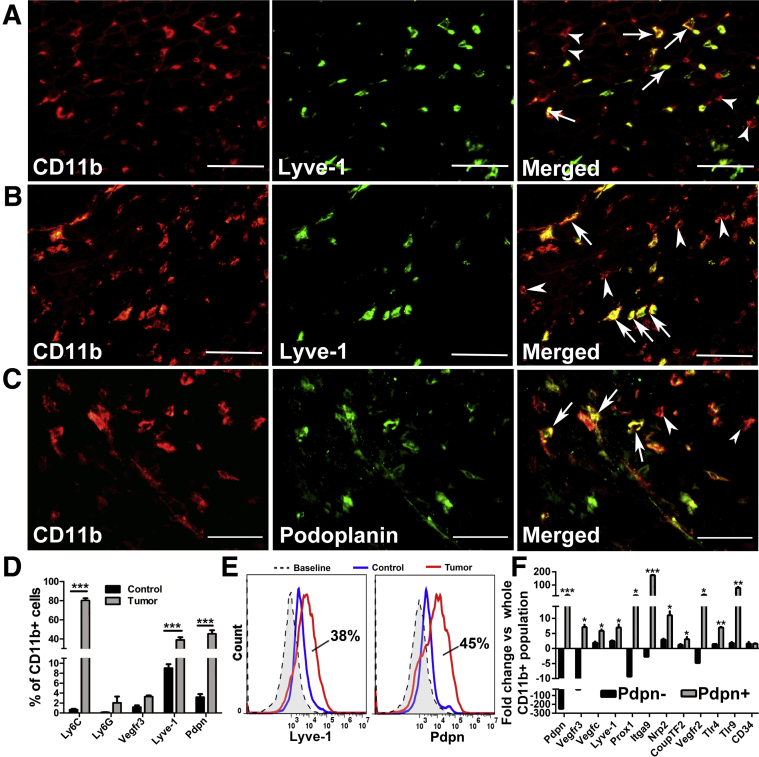

Orthotopic Mouse BC Models Faithfully Reproduce the M-LECP Behavior in Clinical BC

To this point, data demonstrate that BC patients have high levels of circulating M-LECPs. These myeloid-lymphatic progenitors are derived from BM and recruited to tumors, where they promote the development of new LVs and metastasis. To confirm the extent to which M-LECPs are involved in LV development, orthotopic BC models were used to recapitulate the observations for clinical BC. TAMs and LVs in metastatic human MDA-MB-231 tumors,29 mouse syngeneic R3L,43 and EMT644 models as well as transgenic MMTV-PyMT tumors considered a close representative of clinical BC45 were examined for expression of LEC markers. In all models, >50% of TAMs expressed at least one LEC marker, with the greatest number of double-positive TAMs (76%) found in MDA-MB-231 tumors (Supplemental Table S3), which is consistent with high lymphangiogenic potential and predominant lymphatic metastasis in this model.29, 46 Immunohistochemical identification of M-LECPs in EMT6 and MDA-MB-231 tumor models (Figure 9, A–C) was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis of tumor-isolated CD11b+ myeloid cells (Figure 9, D and E). This analysis showed that approximately 80% of M-LECPs are immature monocytes, indicated by coexpression of Ly6C (a monocytic progenitor marker), CD11b, and LEC markers (Figure 9D). Of CD11b+ cells, 38% and 45% were positive for Lyve-1 and Pdpn, respectively, demonstrating that a large portion of TAMs in mouse models are, in fact, M-LECPs (Figure 9E). Compared with both unfractionated CD11b+ and Pdpn-negative TAMs, Pdpn+ macrophages expressed much higher levels of numerous LEC-specific transcripts, including Lyve-1, Vegfr-3, Prox-1, and Itga-9 (Figure 9F and Table 3). Similar to clinical tumors, all examined mouse models had significant numbers of lymphatic vessels coexpressing myeloid proteins. Confocal analysis of triple-stained MMTV-PyMT, as well as other tumors using antibodies to Lyve-1 combined with CD11b, VE-cadherin, or Pdpn, showed coexpression of myeloid markers in 60% and up to 99% of tumor LVs (Supplemental Figure S2). Collectively, these findings support the hypothesis that Lyve-1+ and Pdpn+ tumor macrophages, human and mouse, represent myeloid-lymphatic progenitors that promote lymphangiogenesis by coalescing with existing vasculature.

Figure 9.

Most macrophages in orthotopic mouse breast cancer models are myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors. A–C: EMT6 (A) and MDA-MB-231 (B and C) tumors were double stained for CD11b and lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (Lyve-1; A and B) or podoplanin (Pdpn; C). White arrows indicate myeloid-lymphatic hybrid cells expressing CD11b and lymphatic endothelial cell (LEC) markers, whereas white arrowheads indicate cells positive only for CD11b. D: CD11b+ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting from MDA-MB-231 tumors, were analyzed by flow cytometry for myeloid progenitor markers Ly6C and Ly6G as well as LEC markers vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (Vegfr-3), Lyve-1, and Pdpn. E: Representative histograms of CD11b+/Lyve-1+ and CD11b+/Pdpn+ cells demonstrating shifts in tumor-derived versus peritoneal macrophages from non–tumor-bearing mice. F: TAMs were sorted for CD11b+/Pdpn+ and Pdpn− cells. F: Pdpn+, Pdpn−, and whole CD11b+ populations were analyzed by real-time PCR for lymphatic marker expression. Results are the mean values from two independent experiments. All analyzed targets, except CD34, were significantly up-regulated in the Pdpn+ group compared with other groups. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (determined by t-test). Scale bar = 100 μm (A–C). Original magnification, ×400 (A–C). CoupTF2, chicken ovalbumin upstreampromoter transcription factor 2; Itga9, integrin subunit alpha 9; Nrp2, neuropilin; Prox1, prospero homeobox protein 1; Tlr, toll-like receptor; Vegfc, vascular endothelial growth factor C.

Table 3.

Normalized CT Values of Lymphatic-Specific Genes in Pdpn-Positive and Pdpn-Negative TAMs

| Gene | All CD11b+ | PDPN+ | PDPN− | Fold change |

P value∗ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDPN+ versus all CD11b+ | PDPN− versus all CD11b+ | |||||

| Pdpn | 13.45 ± 0.01 | 8.74 ± 0.42 | 21.41 ± 0.10 | 21.27 ± 5.55 | −250 ± 0.002 | 0.062 |

| Vegfr3 | 16.12 ± 0.24 | 13.30 ± 0.22 | 21.31 ± 0.25 | 7.10 ± 0.76 | −33.3 ± 0.003 | 0.011 |

| Vegfc | 15.96 ± 0.19 | 13.41 ± 0.14 | 15.04 ± 0.35 | 5.87 ± 0.41 | 1.93 ± 0.32 | 0.017 |

| Lyve1 | 17.69 ± 0.23 | 14.90 ± 0.27 | 16.37 ± 0.13 | 6.98 ± 0.91 | 2.50 ± 0.16 | 0.04 |

| Prox1 | 18.26 ± 0.01 | 13.92 ± 0.23 | 21.53 ± 0.07 | 20.38 ± 2.25 | −9.09 ± 0.004 | 0.012 |

| Nrp2 | 12.08 ± 0.22 | 8.63 ± 0.23 | 10.52 ± 0.23 | 11.04 ± 1.26 | 2.97 ± 0.26 | 0.024 |

| Itga9 | 15.43 ± 0.11 | 7.99 ± 0.02 | 16.91 ± 0.39 | 173.65 ± 1.81 | −2.74 ± 0.07 | 0.0001 |

| Vegfr2 | 14.58 ± 0.05 | 9.96 ± 0.26 | 16.85 ± 0.01 | 24.87 ± 3.17 | −4.76 ± 0.001 | 0.02 |

| Couptf2 | 14.20 ± 0.16 | 12.59 ± 0.05 | 13.93 ± 0.42 | 3.06 ± 0.74 | 1.23 ± 0.25 | 0.016 |

Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

PDPN, podoplanin; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage.

P values represent differences in gene expression between Pdpn-positive and Pdpn-negative CD11b+ macrophages.

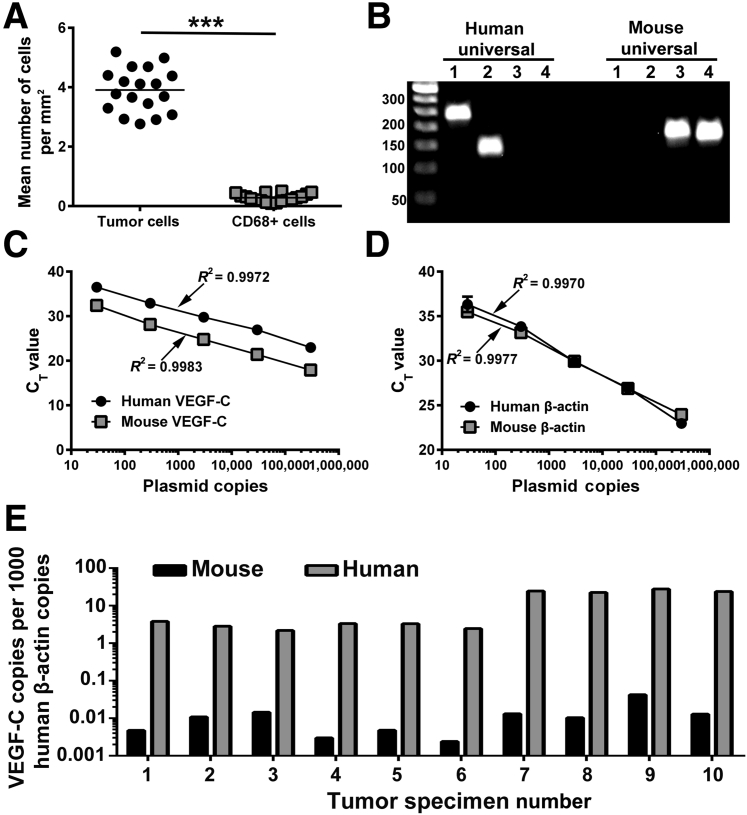

The Level of TAM-Produced Lymphangiogenic Factors Does Not Explain Their Major Role in Tumor Lymphangiogenesis

The current paradigm states that TAMs promote lymphangiogenesis by excessive production of lymphangiogenic factors,12 primarily VEGF-C.10 However, abundant evidence was found for M-LECP integration into LECs of lymphatic vessels, which suggested cell-autonomous function. To clarify the importance of TAM-produced VEGF-C, a new quantitative PCR assay was established to measure the absolute transcript number of tumor (human) and host (mouse) VEGF-C for the MDA-MB-231 BC xenograft model, which is known for efficient recruitment of BM myeloid cells, induction of lymphangiogenesis,47, 48 and prominent LN metastasis.29, 48 Validation of specific primers and TaqMan probes for human and mouse VEGF-C showed species specificity (Figure 10B) and linear detection of VEGF-C and β-actin internal control (Figure 10, C and D). Measurements of actin-normalized copies of human and mouse transcripts in tumor samples (N = 10) showed substantial bias toward tumor-produced VEGF-C (Figure 10E), with differences ranging from 150- up to 2000-fold (mean, 985-fold ± 438-fold). Mouse VEGF-C, which constitutes <1% of the total intratumoral pool, represents the entire array of stromal contributing cells, including TAMs, fibroblasts, and endothelium. Bias toward tumor-produced VEGF-C is also suggested by prevalence of malignant cells over macrophages, which was detected in both mouse models and clinical breast cancers (ratio, 13.7 for tumor cells) (Figure 10A). This prevalence of tumor cells compared with macrophages and determination of absolute VEGF-C copies collectively suggest that, in cancer, the role of TAMs in lymphangiogenesis is unlikely to be mediated by soluble factors as those are excessively produced by malignant cells.

Figure 10.

The level of tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)–produced lymphangiogenic factors does not explain their major role in tumor lymphangiogenesis. A: The numbers of tumor cells and CD68+ macrophages were quantified in clinical breast cancer specimens in four fields and normalized per area. The difference between the mean number of tumor cells and CD68+ TAMs was determined by a t-test. B: Species specificity of in-house designed primer sets for human and mouse β-actin (lanes 1 and 3) and vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C; lanes 2 and 4) was determined using human and mouse universal cDNA. C and D: Human- and mouse-specific probes for VEGF-C (C), β-actin (D), and plasmids containing a single insert of each gene were used to establish standard curves. A linear regression was assessed for each probe, and corresponding R2 values are listed. RNA from MDA-MB-231 xenograft tumors was used to determine the absolute number of copies of mouse and human VEGF-C transcripts for each sample. The values were normalized per 1000 copies of human β-actin. Normalization per mouse β-actin is not shown because it yielded an identical ratio between human and mouse VEGF-C transcript copies. E: Each bar set represents the normalized amount of mouse and human VEGFC present in an individual tumor. All analyses were performed in triplicate, with <5% difference between replicates. N = 18 (A); N = 10 (E). ***P < 0.001.

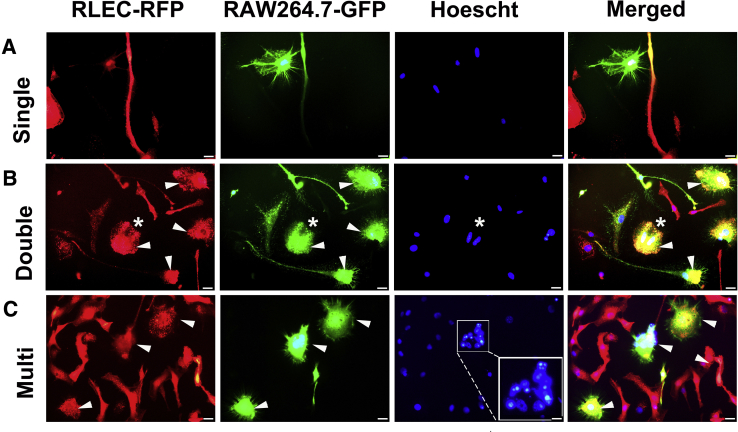

An in Vitro Model of M-LECP and LEC Interactions Suggests that Myeloid Expression in Tumor Lymphatic Vessels Might Result from Fusion

An alternative mechanism by which M-LECPs might promote lymphatic formation is by delivering their transcriptome and regulatory factors directly to inflamed LECs via fusion. BM stem and progenitor cells often fuse with injured49 or inflamed50 cells to drive proliferation51 or impose reprogramming52 necessary for repair or expansion of existing structures. This suggests that myeloid marker expression in tumor LV (Figure 5) and inflamed vasculature34, 53 might be the result of fusion.

To test this hypothesis, a novel cell assay was established using RAW264.7 cells that differentiate into M-LECPs after exposure to LPS30 and RLECs that reproduce main attributes of LECs in vivo.31 Macrophages and LECs tagged with green and red fluorescent proteins, respectively, dubbed RAW-GFP and RLEC-RFP, were co-cultured in the presence of LPS or with vehicle control for 4 to 6 days. LPS stimulation caused cells to fuse with high frequency, as indicated by the appearance of yellow cells (Figure 11). Fusion was preceded by interaction between the two cell types (Figure 11A) and followed by a substantial increase in binucleated and multinucleated cells (Figure 11, B and C). Hoechst staining of DNA identified GFP+/RFP+ double-positive cells that contained up to nine nuclei (Figure 11C). Thus, this model replicates the key observations from tumor studies: absence of myeloid markers in LECs under noninflamed conditions, prominent expression of such markers in tumor LECs, and induction of cell division after integration. The model also demonstrates the feasibility of fusion between M-LECPs and LECs under inflammatory conditions. Future studies with this model should aid in elucidating specific mechanisms underlying progenitor-LEC interactions.

Figure 11.

In vitro model suggests that expression of myeloid markers in tumor lymphatic vessels might result from fusion. Red fluorescent protein (RFP)–tagged rat lymphatic endothelial cells (RLECs) were cocultured for 4 to 6 days with the green fluorescent protein (GFP)–tagged macrophage cell line RAW264.7 in the presence of 3 nmol/L lipopolysaccharide or vehicle. Cells were monitored daily using a fluorescent microscope. A: Contact between the two cell types was observed on days 2 to 3 when most cells contained a single nucleus. B: Fusion between the two cell types was observed on days 4 to 5, as indicated by colocalization of RFP and GFP and the presence of two nuclei in the cell with overlapping colors (white asterisk). C: On days 4 to 6, multinucleated RFP+/GFP+ cells containing up to nine nuclei in a single cell were observed, as highlighted by the white boxed area. The latter image was acquired at a higher magnification (inset) to highlight the numerous nuclei present in the single cell. White arrowheads point to double-positive cells for GFP and RFP indicating fusion. Scale bar = 20 μm (A–C). Original magnification: ×600 (A–C); ×1200 (C, inset).

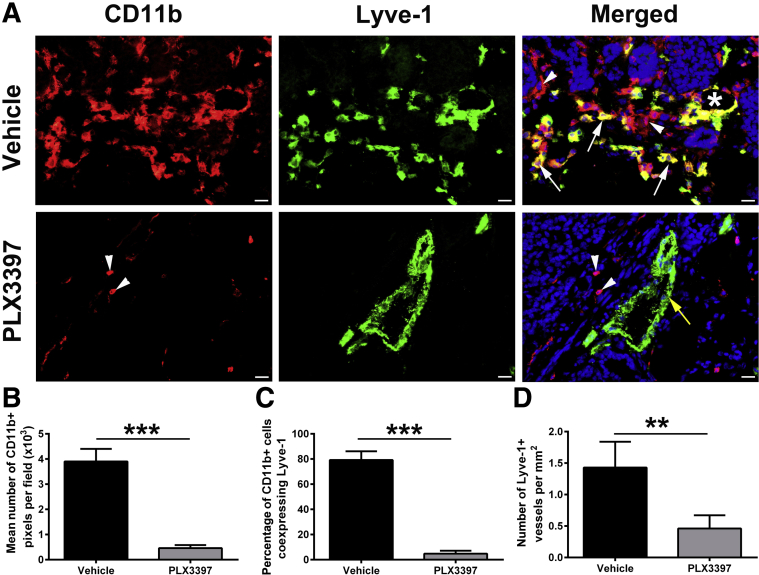

Inhibition of BM Myeloid Cell Recruitment Greatly Suppresses Tumor M-LECPs and Lymphatic Vessel Density

The cause-and-effect relationships between recruitment of TAMs, including M-LECPs and lymphatic vessels expressing myeloid markers, as well as lymphatic metastasis under controlled conditions in experimental BC models were examined. Treatment with MMTV-PyMT tumor-bearing mice with the CSF1R inhibitor PLX3397 suppresses myeloid lineage development, recruitment of myeloid cells to tumors, and lung metastasis.32 Herein, it was examined how PLX3397 treatment impacted M-LECP recruitment and integration into LVs (Figure 12). PLX3397 drastically reduced the density of CD11b+ cells and virtually eliminated M-LECPs (Figure 12, A–C). Moreover, the number of lymphatic vessels was also significantly reduced (Figure 12, A and D). Residual TAMs did not express lymphatic markers, suggesting that treatment suppressed recruitment and CSF1-dependent differentiation.34 Coupled with correlative data demonstrating positive relationships between clinical tumor M-LECPs and LVD (Figure 3), these findings suggest that recruitment and/or differentiation of M-LECP is required for lymphatic sprouting.

Figure 12.

Myeloid cell recruitment and density of tumor myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors are drastically reduced by the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor PLX3397. A: Transgenic MMTV-PyMT tumors were treated with vehicle or PLX3397. Tumors were harvested and costained for lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (Lyve-1) and CD11b proteins. White arrows and arrowheads indicate CD11b+ cells that coexpress and lack Lyve-1, respectively. The white asterisk indicates a luminal lymphatic vessel that coexpresses both markers. The yellow arrow indicates a lymphatic vessel that does not coexpress CD11b. Nuclei in merged images are identified by Hoechst stain. B: Total number of recruited CD11b+ cells was calculated by determining the total number of pixels per field. C: The percentage of Lyve-1 colocalization with tumor-associated macrophages was determined in CD11b+ cells per tumor section. D: The total number of lymphatic vessels was quantified on the entire cross-section and normalized per mm2. N = 4 per group (A); n = 50 (C). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (determined by t-test). Scale bar = 20 μm (A). Original magnification, ×400 (A).

Adoptive Transfer of M-LECPs Significantly Increases Lymphatic Metastasis

A complementary approach to show cause and effect is to exogenously add suspected cell candidates to tumors in vivo and analyze functional impact on metastasis. M-LECPs differentiated in vitro increase lymphangiogenesis in vivo.34 However, the impact of added M-LECPs on BC lymph node metastasis has not been thoroughly examined. Herein, in vitro differentiated M-LECPs injected into immunocompetent mice with orthotopic EMT6 breast tumors did not affect the tumor growth rate (Figure 13A) but significantly increased metastatic burden in proximate LNs (P = 0.03) (Figure 13B). The burden in lungs was also increased, but the difference with saline-control group did not reach significance (Figure 13C). As a control, an identical number (1 × 106) of freshly isolated unfractionated or fractionated BM cells were injected. Compared with saline injection, neither control population group had an effect on tumor growth rate or metastatic burden in LNs or lungs (Figure 13). These data strongly suggest that the lymphangiogenic potential of BM-derived myeloid cells directly depends on TLR4 or other inflammation-induced differentiation of BM hematopoietic stem/progenitors. These data also show that EMT6 and other tumor models15 can be reliably used for defining the mechanisms of M-LECP differentiation in the BM, recruitment to breast tumors, and impact on lymphatic metastasis. Collectively, these analyses show that experimental manipulation of tumor M-LECPs is directly associated with myeloid integration into lymphatic vessels, increased vessel sprouting, and tumor cell transport to regional lymph nodes.

Figure 13.

Experimentally differentiated myeloid-derived lymphatic endothelial cell progenitors (M-LECPs) significantly increase lymphatic metastasis in orthotopic breast cancer models. BALB/c female mice were orthotopically implanted with syngeneic EMT6-Luc tumor cells. One day after implantation, mice were intravenously injected with the following: i) saline; ii) 1 × 106 of unfractionated naïve bone marrow cells; iii) 1 × 106 of naïve CD11b− cells; or iv) 1 × 106 of CD11b− cells differentiated with 10 ng/mL of mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 for 3 days, followed by a 3-day treatment with 3 nmol/L of lipopolysaccharide. A: Tumor growth rate was monitored twice a week until tumors reach 1.8 cm3 in volume. B and C: Ipsilateral lymph nodes (B) and lungs (C) were analyzed for the metastatic burden based on protein-normalized luciferase activity in tissue homogenates. Results are presented as individual values of relative light units (RLU)/mg of protein obtained in tissue homogenate from each mouse. The black bars indicate the mean values per group. n = 5 per group. *P < 0.05 (determined by U-test). WBM, whole bone marrow.

Discussion

The salient findings of this study are as follows: i) blood-circulating and tumor-recruited M-LECPs are abundant in BC patients but absent in healthy, cancer-free individuals; ii) the densities of single and LV-integrated M-LECPs strongly correlate with lymphatic metastasis in clinical BC; iii) tumor M-LECPs originate from BM-derived immature myeloid precursors; and iv) decrease and increase in tumor M-LECPs directly corresponds to LVs with myeloid markers and LN metastasis in mouse BC models, demonstrating their contribution to both processes. Novel assays that identify tumor cells, not TAMs, as a primary source of VEGF-C, and fusion as a potentially critical TAM-LEC interaction for induction of new lymphatics, were also established.

CD14+ monocytes from cancer-free individuals have low or no expression of LEC markers.15 In contrast, monocytes from BC patients express high levels of multiple LEC-specific transcripts, including PDPN,54 LYVE-1,55 VEGFR-3,56 COUP-TF2,57 PROX-1,58 and ITGA-959 (Figure 1). Identification of multiple LEC markers in cancer-induced monocytes strongly suggests that these cells underwent prolymphatic reprogramming rather than random transcriptional deregulation. Myeloid-lymphatic transition in mouse inflammatory models in vivo30 and inflammation-induced differentiation of normal human monocytes in vitro have been reported.15 Myeloid-lymphatic transition is triggered by an autocrine VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 loop,30, 34 which ultimately leads to acquisition of the lymphatic phenotype. Consistently, 90% of BC patient monocytes coexpress VEGF-C and VEGFR-3 as well as other LEC markers (Figure 1I). Previously, TIE-2+ monocytes were identified as a major myeloid subset driving tumor lymphatic formation.60 However, enrichment of TIE-2 expression in cancer monocytes was not seen when compared with healthy cells (Figure 1, G and I). Although the reason for this discrepancy is unclear, these findings are consistent with others that failed to detect double-positive Lyve-1+/Tie-2+ cells during inflammatory lymphangiogenesis,61 suggesting that expression of Tie-2 in LECPs might be context and condition dependent. According to this analysis, the most reliable markers for detection of prolymphangiogenic reprogramming of human monocytes are PDPN and LYVE-1.

A substantial increase in numbers of circulating monocytes expressing LEC markers was previously reported for patients with small-cell lung carcinoma26 and ovarian cancers,27 where they correlated with LN status. Our analyses show that although LECPs were elevated in BC patients, the levels in the blood did not correlate with LN status. This might be due to higher sensitivity of the RT-qPCR assay used herein to detect LEC transcripts compared with flow cytometry–based detection of LEC proteins in circulating monocytes, as performed elsewhere.26, 27 Alternatively, blood-circulating M-LECPs may not possess the full functional competence to generate new vessels and, therefore, their levels do not directly correlate with LN metastasis.

Because the tumor microenvironment may be a key determinant of M-LECP functional competence, it was determined whether the density of these cells in tumors rather than in the blood correlates with LN metastasis. We present herein, for the first time, unambiguous evidence that M-LECPs are present in 84% of analyzed tumors (N = 95), indicating that the vast majority of BC patients have high levels of recruited M-LECPs at the tumor site. In contrast, only 0.5% of CD68+ macrophages in healthy human mammary tissues coexpressed LEC markers, indicating specificity of this cell population to inflammatory or cancerous sites. Moreover, high density of M-LECPs (>20 cells/field) strongly correlated with aggressive BC subtypes (Figure 3D) known to metastasize to LNs.2, 62 Furthermore, analysis of all specimens sorted by node status showed significant correlation between mobilized M-LECPs and lymphatic metastasis (P = 0.02) (Figure 3E and F). These data indicate that M-LECPs in clinical human BC functionally contribute to metastasis, suggesting that their density can serve as a prognostic marker of tumor progression.

Although several reports have shown the presence of LECPs, their origin remains a matter of debate. LECPs have been reported to originate from human monocytes isolated from peripheral or cord blood,24, 25 human pluripotent stem cell lines,63 mouse embryonic cells,64 mouse BM-derived CD11b+ and mononuclear cells,17, 20, 61 mouse and human mesenchymal stem cells,35 and adipose-derived stem cells.65 Although most studies point to the myeloid lineage as the LECP origin,18, 30, 53, 61 some studies did not detect hematopoietic markers in these cells.35, 65 Also, the lymphoid origin of LECPs has not been previously examined. Tumor LECPs were found to overwhelmingly express myeloid markers and largely lacked lymphoid proteins (Figure 5), supporting our findings in experimental models showing clear bias toward the hematopoietic-myeloid origin of LECPs. Also, five selected myeloid markers (TLR4, MD2, CD11b, CD14, and CD18) represent a complex that mediates TLR4 signaling. TLR4 relies on MD2 to recognize LPS,66 whose conformational presentation is enabled by CD14.67 The complex of CD11b/CD18 integrins is also essential for optimal signaling as it facilitates dimerization of TLR4.68 Myeloid-lymphatic transition induction of mouse BM cells and human monocytes requires stimulation of the TLR4 pathway.15 Coexpression of TLR4 and its four essential coreceptors in tumor M-LECPs (Figure 5) is highly supportive of a central role previously proposed for this inflammatory pathway in differentiation of M-LECPs from TLR4+ myeloid precursors.15

The macrophage nature of tumor M-LECPs has also been confirmed by staining for M2-type TAM markers, such as CD204, CD209, and CD163 (Figure 6). Multiple reports documented expression of lymphatic markers in M2-type TAMs19, 69, 70 as well as strong association of CD163+/CD204+ macrophages with clinical tumor lymphangiogenesis.71 However, the reasons for LEC protein expression in TAMs and their direct role in tumor lymphangiogenesis have not been proposed and examined. These collective findings suggest that cancer M-LECPs are BM-derived provascular macrophages programmed to repair damaged tissue. This is consistent with the nature of M2-type macrophages that appear at the late stages of wound healing and are physiologically programmed to restore homeostasis. A prerequisite for this event is generation of new vessels necessary to transport growth factors, nutrients, and, more important, cell progenitors to the site of injury to replenish the damaged tissue.72 It, therefore, stands to reason that wound healing macrophages would include blood and lymphatic endothelial progenitors necessary to induce vascular sprouting.

Another question clarified by this study was the differentiation status of tumor M-LECPs. It was presumed that the hybrid myeloid-LEC phenotype must reflect the early stages of differentiation, but this has not been examined directly in experimental or clinical studies. Herein, we report, for the first time, the widespread expression of HCLS1, PU.1, and CD38 stem cell markers by M-LECPs found in clinical breast tumors (Figure 7 and Supplemental Figure S1). These three markers are mainly associated with hematopoietic stem cells differentiation and are largely absent from normal tissues. These data suggest that human tumor M-LECPs are directly derived from hematopoietic stem cells in the BM rather than local mesenchymal or adipose stem cells, as suggested for noncancerous conditions in mice or in vitro studies.35, 65 It was also found that two of the stem/progenitor markers (PU.1 and HCLS1) are expressed in a significant number of tumor LVs, suggesting that M-LECPs do not reach maturity at the time of vascular integration. Incomplete differentiation of M-LECPs might be driven by local tumor imbalance of regulating factors.73 This observation is in line with well-known prevalence of immature myeloid cells in tumors as opposed to terminally differentiated macrophages in normal tissues.74, 75

M-LECP plasticity might also be instrumental for their unique ability to coalesce with activated LVs. Coalescence or integration of CD11b+ myeloid-lymphatic progenitors with preexisting LVs has been reported in an inflammatory cornea model61 and other mouse models of wound healing and inflammation.30, 76 Intimate associations of LECPs with activated LVs were detected in tumor models17, 19, 20 as well as inflamed human tissues.77, 78, 79 Coexpression of myeloid and lymphatic markers throughout the vascular structures has been shown in mouse models of melanoma,18 peritonitis,30 and wound healing.69 Similar to the latter studies, in clinical BC, LV-expressing myeloid markers spanned the entire vascular structures and coincided with Hoechst-stained nuclei of LECs. Supplemental Video S1, showing rotation of a lymphatic vessel, clearly demonstrates coexpression of myeloid, lymphatic, and stem cell markers (CD68, LYVE-1, and PU.1) throughout the vessel and correct subcellular localization. On the basis of confocal analysis of multiple specific markers for both lineages (Figure 7), it can be concluded that detection of myeloid markers in tumor LV reflects fusion of M-LECPs with inflamed LECs. This tentative conclusion is supported by a preliminary study using our novel in vitro model of RLEC-RFP and RAW-GFP (Figure 11). Co-culture of these two labeled cell types in the presence of LPS resulted in high frequency of fused cells that contained two or more nuclei (Figure 11).

A possible fusion of M-LECPs with LECs provides either additional or alternative explanation for the well-established dependency of tumor lymphangiogenesis on TAMs. This is mainly attributed to TAM overexpression of lymphangiogenic factors,12, 13 although the actual amounts of tumor cells and TAM-produced factors have not been quantitatively assessed. Using a TaqMan-based method of measuring absolute transcript copies, it was shown that tumor production of VEGF-C exceeds that of the entire stroma by nearly 1000-fold (Figure 10). This analysis does not support the notion that TAM-produced VEGF-C can significantly contribute to the overall tumor pool. These data are consistent with previously reported ratio of tumor-to-TAM–produced VEGF-C in a mouse syngeneic model Rip1Tag2;vascular endothelial growth factor C.19 Despite some differences in the tumor type and species origin, mouse strains, and method of analysis, the conclusion of this prior report was identical to ours (namely, TAMs are not a primary source of VEGF-C in cancer).19 This raises the question: if soluble lymphangiogenic factors are mainly supplied by malignant cells, what is the role of M-LECPs in tumor lymphatic formation?

Given the data presented herein, it is tempting to speculate that self-autonomous contribution of M-LECPs donating their cellular contents to inflamed LECs might be of higher significance than production of soluble factors. Fusion can enforce direct delivery of transcription factors and other potential regulators necessary for inducing LEC sprouting. This hypothesis is consistent with the well-known ability of stem cells and progenitors to use exosomes, nanotubes, and fusion for transferring biological material to induce lineage reprogramming at sites of tumors,80 injury,81 and chronic inflammation.50 This might explain how a relatively small number of LECPs18, 20, 24, 77 can overcome natural vessel resistance to undergo sprouting, which is typically suppressed in adults. Assuming that myeloid marker expression in lymphatic vessels reflects combined cellular contents of TAMs and LEC, the density of such vessels significantly correlates with LN metastasis (Figure 8, D–F). This finding suggests a direct link between insertion of M-LECP proteins or other substances into inflamed LECs and ensuing sprouting that leads to increased tumor spread.