Abstract

Anorexia nervosa (AN), a psychiatric disorder characterized by altered body image, food restriction and low body weight, is associated with low bone mineral density and increased fracture risk. Despite broadening the definition of AN in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, the prevalence of low bone mass remains high, suggesting we continue to capture individuals at high risk for bone loss. Many of the endocrine disturbances adaptive to the state of chronic starvation are thought to be causal in impaired skeletal integrity in females and males with AN. Understanding mechanisms responsible for impaired bone quality is important given the disease’s severity and chronicity. Further research is needed to formulate optimal treatment strategies to reduce fracture risk.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Bone mineral density, Osteoporosis

1. Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by altered body image, food restriction and low body weight. In 2013, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) broadened the diagnostic criteria for AN by making the weight criteria less stringent and removing the requirement for amenorrhea [1]. This has increased the prevalence of AN among female adolescents by about 50%, ranging from 0.8 to 1.7%[2–4]. In addition, the diagnosis of ‘atypical AN’ was created within the Other Specific Feeding or Eating Disorders (OSFED) category for those individuals who are not low weight but meet AN psychological criteria[1]. AN is associated with increased fracture risk in females[5], including those with normal bone mineral density (BMD)[6]. Less is known about fracture risk in males with AN, although one study reported a higher fracture risk among males >40 years old compared with controls[7]**.

2. Bone mineral density

Multiple studies have shown reductions in spine and hip BMD in both adolescents and adults with AN. In the first report of BMD across the AN spectrum, the presence of a BMD Z-score <−1 at any site was comparable between women with AN and atypical AN (80% vs 69%)[8]**. In contrast, more severe bone loss, i.e. BMD Z-score <−2, was more common in women with AN compared to atypical AN (44% vs 25%, p=0.01). These prevalence rates are similar to women with AN using DSM-IV criteria[9],suggesting that the high prevalence of low bone mass persists despite new diagnostic criteria. In addition, women with atypical AN are also at high risk for bone loss.

In the first study to evaluate sex differences in BMD among adolescents with AN using DSM-5 criteria, similar percentages of males and females had a BMD Z-score <−1 at the spine (48 vs 45%) or hip (44 vs 45 %)[10]**. These data confirm a prior study of adolescent boys with AN using DSM-IV criteria[11], again suggesting that broadening the diagnostic criteria for AN has not changed the prevalence of low bone mass.

3. Bone microarchitecture and estimated bone strength

Two DXA-derived parameters, hip structural analysis (HSA) and trabecular bone score (TBS), provide information about bone structure and strength. HSA reports hip structural geometry and estimated strength; both correlate with 3-D quantitative CT[12] and fracture risk[13,14]. HSA parameters have been reported to be impaired in both women[15] and male adolescents[16] with AN. TBS also correlates with fracture risk[17] and in one study, TBS showed evidence of degraded microarchitecture in over 40% of female adolescents with AN[18]*.

Impaired cortical and trabecular microarchitecture and lower estimated bone strength, using high resolution peripheral quantitative CT (HR-pQCT), have been reported at the distal radius in adolescent girls with AN[19]. Whether weight-bearing would overcome the detrimental effects of AN at the distal tibia was investigated by Singhal et al. who reported that female adolescents and young adults with AN had greater cortical porosity and lower total and cortical volumetric BMD (vBMD), cortical thickness, trabecular number and strength estimates than controls[20]**. In contrast, DiVasta et al. reported lower trabecular, but higher cortical, vBMD as assessed by pQCT in adolescent girls with AN compared to controls[21]. These results could be due to differences in site assessed, techniques and disease severity. Singhal et al. also investigated individual trabeculae segmentation in their cohort, and reported a preferential preservation of rod-like (versus plate-like) trabecular bone in AN, which was associated with lower strength estimates, and consistent with reports that more rod-like trabeculae are detrimental to bone strength[22]. Lastly, this paper demonstrated that bone strength estimates are associated with cortical and trabecular microarchitecture independent of areal BMD (aBMD). Both the peripheral and axial skeleton are compromised in women with AN. Vertebral BMD and estimated strength measured by QCT are impaired in women with both AN and atypical AN compared to controls[23]*.

4. Skeletal integrity in recovery

Impaired skeletal integrity and increased fracture risk are often long-term comorbidities in AN. Studies have demonstrated that women continue to have reduced BMD 9[24] and 21 years[25] after the onset of recovery from AN. Mueller et al. reported that women in recovery from AN for a mean of 27 years have reduced trabecular vBMD at the distal tibia compared to controls[26]*. These data support the concept that impaired skeletal integrity persists despite recovery.

5. Determinants of skeletal integrity

5.1. Body composition

Body weight and body composition are important determinants of skeletal integrity. Muscle has an anabolic effect on bone through mechanical loading and muscle-bone hormonal crosstalk. Low lean body mass has been associated with impaired BMD, bone microarchitecture and estimated bone strength in females with AN[27,28] (Figure 1). More recently, the effect of muscle strength on skeletal health in women with AN has been investigated by calculating maximal voluntary ground reaction forces (Fm1LH), a measure of bone strength that includes skeletal muscle force production. Mueller et al. demonstrated that variability in tibial vBMC is largely explained by Fm1LH, and that women with a history of AN, but currently in recovery, have lower tibial vBMC and Fm1LH than controls[26]*.

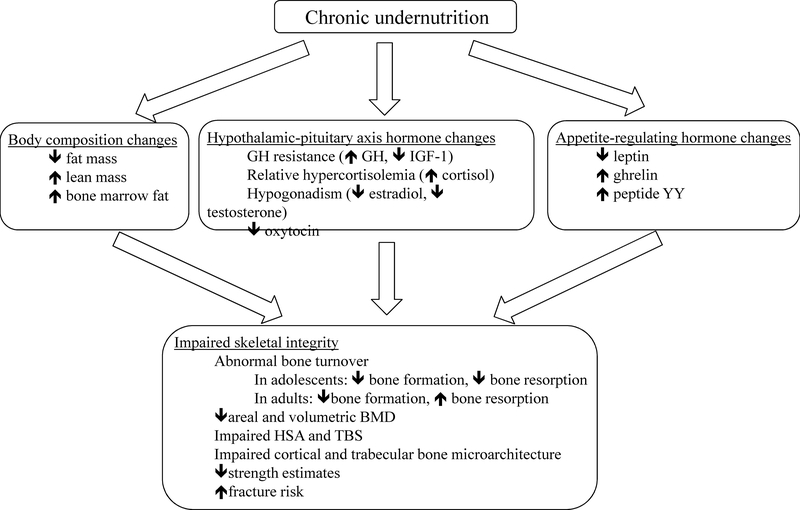

Figure 1. Summary of endocrine dysregulation in individuals with anorexia nervosa and its effects on skeletal integrity.

Endocrine dysregulation in anorexia nervosa is mostly adaptive to the state of chronic undernutrition. Body composition changes, hypothalamic-pituitary axis hormone changes and appetite-regulating hormone changes all contribute to impaired skeletal integrity. GH: growth hormone. IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor 1. HSA: hip structural analysis. TBS: trabecular bone score.

A relatively new area of investigation is bone marrow fat, which is paradoxically elevated in women with AN despite reduced total body fat[29,30] (Figure 1). Higher preadipocyte factor 1 (Pref-1) levels, which is a negative regulator of osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation, is associated with higher marrow fat content and lower bone mass in women with AN[31]. Bredella et al. demonstrated an inverse relationship between marrow fat content and BMD at multiple skeletal sites[30,32], as well as between marrow fatty acid saturation and BMD[33]. The relationship between marrow fat and BMD in adolescents is more complex, as both marrow fat and BMD normally increase rapidly during adolescence[34]. Ecklund et al. reported a positive relationship between marrow fat and BMD in younger female adolescents with AN [35]. Faje et al. reported that although Pref-1 levels are comparable in adolescent girls with AN and controls, Pref-1 levels decrease after treatment with transdermal estradiol, and correlate inversely with changes in BMD, suggesting that Pref-1 may mediate the effects of transdermal estradiol on BMD[36].

5.2. Nutrition

The prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in AN largely depends on the use of supplements. Vitamin D deficiency was reported to be much less common among adolescents with AN than healthy youths[37], in part due to the high prevalence of supplementation. A more recent study in found that approximately 60% of females with AN had 25OHvitD levels <30 ng/mL and 36% were <20 ng/mL[38]. Hip BMD was significantly lower in subjects with 25OHvitD levels <12 vs ≥20 ng/mL. A 20-week observational study demonstrated that weight gain was associated with an increase in spinal BMD only in females with AN who had 25OHvitD levels ≥30 ng/mL[39]*. Maintaining adequate 25OHvitD levels during treatment may be important to maximize gains in BMD.

In healthy adolescents and adults, mechanical loading (i.e. exercise) has beneficial effects on bone. In contrast, in individuals with AN who are in a state of energy deficit, exercise has deleterious effects on bone because caloric expenditure further worsens the energy deficit. Resting energy expenditure (REEm), or basal metabolic rate, decreases as an adaptive response to energy deficit. Maimoun et al. reported that REEm in women with AN was positively correlated with bone formation markers and negatively correlated with bone resorption markers[40]. However, in individuals in recovery from AN, high bone loading activities may help increase bone accrual[41].

It is also important to consider the effect of prescription and non-prescription drugs on skeletal integrity. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRI) have been associated with lower BMD[42] and increased fracture risk in females with AN[7,43]**. A recent meta-analysis reported high levels of smoking in individuals with AN[44], which has been associated with lower bone mass. Alcohol abuse has been independently associated with an increased fracture risk in females and males with AN[7]**.

5.3. Onset and duration of disease

Adolescence is a period of high bone turnover, with bone formation exceeding bone resorption as peak bone mass accrues[45]. In contrast, adolescents with AN have both decreased bone formation and resorption[46], causing compromise of peak bone mass accrual. In contrast, adult women with AN have decreased bone formation and increased bone resorption, resulting in loss of established bone mass. For both groups, changes in bone mass may occur relatively rapidly, often within the first year of disease[47]. Moreover, duration of illness is associated with lower BMD in both male[48] and female adolescents[49] and women[5], and more impaired bone microarchitecture in females[19], suggesting that bone loss continues throughout the course of the illness[49].

5.4. Hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis

The energy deficit associated with nutritional deprivation in females with AN often results in hypothalamic amenorrhea, which contributes to impaired skeletal integrity (Figure 1). Leptin, which is positively associated with fat mass, is a proposed regulator of kisspeptin neurons in the hypothalamus, which signal to GnRH neurons[50]. Although abnormal leptin and kisspeptin signaling are major regulators of hypothalamic amenorrhea, there is no a clear cut-off in serum leptin levels between women with AN who are amenorrheic and those who are eumenorrheic of comparable low weight and psychopathology [51], suggesting other mechanisms may contribute, such as underlying genetic susceptibility of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to nutritional deprivation.

Hypothalamic amenorrhea results in low estradiol and androgen levels in females with AN[52]. Estradiol inhibits bone resorption by inhibiting receptor activator of nuclear factor k B ligand (RANKL) secretion, which increases osteoclastogenesis and osteoclastic activity, and increasing osteoprotegerin (OPG) secretion[53], a factor that inhibits osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast activity. Estrogen stimulates bone formation by inhibiting sclerostin secretion, a factor that inhibits osteoblast differentiation[54]. Consistent with these data, decreased ratios of OPG/RANKL[55] and increased sclerostin levels[56] have been reported in women but not adolescents with AN [57]. Numerous studies have reported that a longer duration of amenorrhea is associated with worse skeletal integrity[5,15,23]*, as is a history of amenorrhea in those who are currently eumenorrheic[8,58]**. However, bone resorption is higher in adult amenorrheic women with AN than postmenopausal women, suggesting other factors contribute to increased bone resorption in AN[59]. The contribution of hypogonadism to impaired skeletal integrity in males with AN is less well understood.

5.5. GH- IGF-1 axis

Chronic nutritional deprivation in AN is a state of acquired growth hormone (GH) resistance, characterized by increased GH and decreased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) secretion[60,61] (Figure 1). GH and IGF-1 stimulate osteoblast differentiation while inhibiting osteoclast differentiation, and GH independently stimulates osteoblast proliferation[62]. Accordingly, low serum levels of IGF-1 in women with AN are associated with low levels of bone formation markers [46,63], low BMD[46] and impaired bone microarchitecture[64].

5.6. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

In at least one-third of women with AN, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is in a chronically stimulated state due to the stress of chronic nutritional deprivation[65,66] (Figure 1). Cortisol decreases bone formation and increases bone resorption, in part by inhibiting osteoprotegerin and increasing RANKL secretion[67]. Hypercortisolemia is inversely associated with BMD in females with AN[65,66].

5.7. Alterations in appetite-regulating hormones

Appetite-regulating hormones are altered in AN and may contribute to impaired skeletal integrity (Figure 1). Low nocturnal serum oxytocin levels are associated with decreased spine BMD, as well as some measures of impaired hip structure and strength in women with AN, independent of BMI[68]. In women with AN, hypoleptinaemia is associated with lower femoral neck and spine BMD, as well as abnormalities in bone microarchitecture, independent of BMI[64]. Serum peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) levels, an anorexigenic hormone, are inappropriately elevated in females with AN[73]. PYY is thought to inhibit osteoblastic activity while increasing osteoclastic activity[74]. Consistent with these data, mean overnight PYY levels are negatively associated with BMD in women with AN, independent of BMI[73].

6. Management of low bone mass

The most effective therapy to improve skeletal integrity in AN is successful treatment of the underlying eating disorder to reverse many of the adaptive hormone changes associated with active disease. In one study, women with AN who gained weight and resumed menses had a mean annual increase in hip BMD of 1.8% and spine BMD of 3.1%[75] (Table 1). In contrast, those who remained low weight and amenorrheic had a mean annual decline in hip BMD of – 2.4% and spine BMD of –2.6%. Even weight gain, on the order of 5–10% of body weight, may improve bone turnover markers[40]. Importantly, weight gain and resumption of menses may not normalize BMD in all women[76], especially for those who develop active disease during adolescence.

Table 1.

Summary of therapies for low bone mass in adolescent girls and women with anorexia nervosa

| Therapy | Study Design | Subject Characteristics | Control Group(s) | Duration of Treatment | Outcome(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight gain and restoration of menses | Prospective observational | 75 females ages 18–40yo | none | mean 13.5 mo (6–69 mo) | Weight gain and menstrual recovery resulted in annual mean increase of 3.1% in spine BMD and 1.8% in hip BMD compared to an annual decrease of 2.6% in spine BMD and 2.4% in hip BMD in those who did not gain weight or recover menses | Miller 2006 |

| Oral estrogen/progestin | RCT | 48 females ages 16–42yo | no medication | 18 mo | Estrogen/progestin did not increase BMD vs no treatment | Klibanski 1995 |

| Prospective observational | 50 females ages 12–21yo | no medication | mean 23.1 mo | Estrogen/progestin did not increase BMD vs no treatment | Golden 2002 | |

| RCT | 112 females ages 11–17yo | placebo | 13 mo | Estrogen/progestin did not increase BMD vs placebo | Strokosch 2006 | |

| Physiologic transdermal estrogen replacement | RCT | 110 females ages 12–18yo | placebo + 40 normal-weight controls | 18 mo | Physiologic estradiol replacement increased spine and hip BMD vs placebo to approximate bone accrual rates in controls, but catch-up BMD did not occur | Misra 2011 |

| Testosterone | RCT | 77 females ages 19–49yo | placebo | 12 mo | Testosterone did not increase BMD vs placebo | Miller 2011 |

| DHEA | RCT | 61 females ages 14–28yo | oral estrogen/progestin | 12 mo | After controlling for weight gain, no treatment effect was observed with either DHEA or oral estrogen/progestin | Gordon 2002 |

| Recombinant hIGF-1 + oral estrogen/progestin | RCT | 60 females ages 18–38yo | no treatment | 9 mo | rhIGF-1 + oral estrogen/progestin increased spine BMD vs placebo | Grinspoon 2002 |

| Prospective | 20 females ages 12–18yo | no treatment | 7–9 days | rhIGF-1 caused an increase in bone formation markers vs no treatment | Misra 2009 | |

| Risedronate | RCT | 77 females ages 19–49yo | placebo | 12 mo | Risedronate increased spine and hip BMD vs placebo | Miller 2011 |

| Alendronate | RCT | 32 females ages 12–21yo | placebo | 12 mo | Spine and hip BMD increased similarly in the alendronate and placebo groups. Within groups, spine and hip BMD increased significantly within the alendronate group, but not the control group. | Golden 2005 |

| Teriparatide | RCT | 32 females ages 32–58yo | placebo | 6 mo | Teriparatide increased hip BMD vs placebo | Fazeli 2014 |

RCT: randomized controlled trial. DHEA: Dehydroepiandrosterone. hIGFl: human insulin-like growth factor 1.

Oral estrogen is not effective in increasing BMD in adults[77–79], likely in part because oral estrogen decreases IGF-1 production by the liver[80] (Table 1). In contrast, physiological transdermal estrogen replacement with cyclic progesterone has been shown to increase spine and hip BMD in adolescent girls with AN[82] although BMD is not normalized[82] (Table 1). In addition, androgen or androgen precursor replacement, in the form of testosterone or DHEA, does not improve BMD[83,84] (Table 1). Although oral estrogen is not effective in increasing BMD in women with AN, recombinant human IGF-1 (rhIGF-1) administered in combination with oral contraceptives increased mean spine BMD by 2.8% vs placebo untreated women, in whom BMD decreased, in a randomized controlled trial[85] (Table 1).

Both antiresorptive and anabolic therapies have been evaluated in females with AN. In a randomized controlled trial, oral bisphosphonates increased mean spine BMD by 3.2% and total hip BMD by 1.9% after 12 months compared with placebo in women with AN[83] although no effect was seen in adolescent girls with AN[86] (Table 1). Although there is more recent safety data suggesting that bisphosphonates may be safe in women of childbearing age[87], data suggest that these drugs do cross the placenta[88].

Because bone formation is decreased in AN, anabolic strategies have been investigated. Fazeli et al. showed that 6 months of teriparatide, in a small randomized controlled trial of women with AN, increased spine BMD by 6–10%[89] (Table 1). However, an FDA warning advises that this medication should not be prescribed to patients who are at increased risk for osteosarcoma, including adolescents with open epiphyses.

7. Conclusion

Impaired skeletal integrity, defined as low BMD, impaired bone microarchitecture and increased fracture risk, is highly prevalent in both AN and atypical AN. A history of low weight and amenorrhea are important determinants of impaired skeletal integrity, even for those who are currently normal weight and eumenorrheic. Other hormone factors that may contribute to impaired skeletal integrity include GH resistance, hypercortisolemia, and changes in appetite-regulating hormones. Understanding the mechanisms responsible for bone loss in individuals with AN may provide insight into new therapies, which is a critical unmet need as there are currently no FDA-approved medications to treat bone loss in AN. Further research regarding the pathophysiology and treatment of bone loss in adolescent boys and men with AN is also needed.

Highlights.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is associated with low bone density (BMD) and increased fracture risk

Endocrine dysregulation in AN is mostly adaptive to chronic undernutrition and contributes to low BMD

Although weight and gonadal recovery may improve bone health, BMD and fracture risk may not normalize

There are no FDA-approved therapies to treat low BMD in AN, which is a critical unmet need

Abbreviations

- AN

anorexia nervosa

- BMD

bone mineral density

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition

- OSFED

Other Specific Feeding or Eating Disorders

- HSA

hip structural analysis

- TBS

trabecular bone score

- HR-pQCT

high resolution peripheral quantitative CT

- vBMD

volumetric BMD

- aBMD

areal BMD

- Fm1LH

maximal voluntary ground reaction forces

- Pref-1

preadipocyte factor 1

- REEm

resting energy expenditure

- SSRI

selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors

- RANKL

receptor activator of nuclear factor k B ligand

- OPG

osteoprotegerin

- GH

growth hormone

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- PYY

peptide tyrosine tyrosine

- rhIGF-1

recombinant human IGF-1

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Association AP: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing, (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mustelin L, Silen Y, Raevuori A, Hoek HW, Kaprio J, Keski-Rahkonen A: The dsm-5 diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa may change its population prevalence and prognostic value. Journal of psychiatric research (2016) 77:85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nagl M, Jacobi C, Paul M, Beesdo-Baum K, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU: Prevalence, incidence, and natural course of anorexia and bulimia nervosa among adolescents and young adults. European child & adolescent psychiatry (2016) 25(8):903–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Oldehinkel AJ, Hoek HW: Prevalence and severity of dsm-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. The International journal of eating disorders (2014) 47(6):610–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Solmi M, Veronese N, Correll CU, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Caregaro L, Vancampfort D, Luchini C, De Hert M, Stubbs B: Bone mineral density, osteoporosis, and fractures among people with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica (2016) 133(5):341–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, Katzman DK, Ebrahimi S, Lee H, Mendes N, Snelgrove D, Meenaghan E, Misra M, Klibanski A: Fracture risk and areal bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. The International journal of eating disorders (2014) 47(5):458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].JM, Golden NH, Leonard MB, Copelovitch L, Denburg MR: Assessment of sex differences in fracture risk among patients with anorexia nervosa: A population-based cohort study using the health improvement network. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2017) 32(5):1082–1089.** [This is the first study to evaluate sex differences in fracture risk in individuals with anorexia nervosa via a population-based retrospective cohort study of adults <60 years old in the United Kingdom, demonstrating that females, as well as males >40yo, have increased fracture risk compared to healthy controls.]

- [8].Schorr M, Thomas JJ, Eddy KT, Dichtel LE, Lawson EA, Meenaghan E, Lederfine Paskal M, Fazeli PK, Faje AT, Misra M, Klibanski A et al. : Bone density, body composition, and psychopathology of anorexia nervosa spectrum disorders in dsm-iv vs dsm-5. The International journal of eating disorders (2017) 50(4):343–351.** [This is the first study to report direct statistical comparisons of BMD across the DSM-5 anorexia nervosa spectrum in women, demonstrating that the prevalence of a BMD Z-score <−1 at any site was comparable between those who are currently low weight and those are not currently low weight, although the prevalence of a BMD Z-score <−2 was higher in the former group.]

- [9].Miller KK, Grinspoon SK, Ciampa J, Hier J, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Medical findings in outpatients with anorexia nervosa. Archives of internal medicine (2005) 165(5):561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nagata JM, Golden NH, Peebles R, Long J, Leonard MB, Chang AO, Carlson JL: Assessment of sex differences in bone deficits among adolescents with anorexia nervosa. The International journal of eating disorders (2017) 50(4):352–358.** [This is the first study to evaluate sex differences in skeletal health among adolescents with anorexia nervosa using DSM-5 criteria, demonstrating that mean BMD Z-scores were similar between male and female adolescents, and that similar percentages of males and females had BMD Z-scores <−1 at the PA spine and total hip.]

- [11].Misra M, Katzman DK, Cord J, Manning SJ, Mendes N, Herzog DB, Miller KK, Klibanski A: Bone metabolism in adolescent boys with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2008) 93(8):3029–3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ramamurthi K, Ahmad O, Engelke K, Taylor RH, Zhu K, Gustafsson S, Prince RL, Wilson KE: An in vivo comparison of hip structure analysis (hsa) with measurements obtained by qct. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA (2012) 23(2):543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Melton LJ 3rd, Beck TJ, Amin S, Khosla S, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, Riggs BL: Contributions of bone density and structure to fracture risk assessment in men and women. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA (2005) 16(5):460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kaptoge S, Beck TJ, Reeve J, Stone KL, Hillier TA, Cauley JA, Cummings SR: Prediction of incident hip fracture risk by femur geometry variables measured by hip structural analysis in the study of osteoporotic fractures. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2008) 23(12):1892–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bachmann KN, Fazeli PK, Lawson EA, Russell BM, Riccio AD, Meenaghan E, Gerweck AV, Eddy K, Holmes T, Goldstein M, Weigel T et al. : Comparison of hip geometry, strength, and estimated fracture risk in women with anorexia nervosa and overweight/obese women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2014) 99(12):4664–4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Misra M, Katzman DK, Clarke H, Snelgrove D, Brigham K, Miller KK, Klibanski A: Hip structural analysis in adolescent boys with anorexia nervosa and controls. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2013) 98(7):2952–2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Silva BC, Leslie WD, Resch H, Lamy O, Lesnyak O, Binkley N, McCloskey EV, Kanis JA, Bilezikian JP: Trabecular bone score: A noninvasive analytical method based upon the dxa image. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2014) 29(3):518–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Donaldson AA, Feldman HA, O’Donnell JM, Gopalakrishnan G, Gordon CM: Spinal bone texture assessed by trabecular bone score in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2015) 100(9):3436–3442.* [This is the first study to evaluate TBS in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa, reporting that TBS showed evidence of degraded bone microarchitecture in over 40% of females, and was correlated with DXA, peripheral QCT, and body composition measures.]

- [19].Faje AT, Karim L, Taylor A, Lee H, Miller KK, Mendes N, Meenaghan E, Goldstein MA, Bouxsein ML, Misra M, Klibanski A: Adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa have impaired cortical and trabecular microarchitecture and lower estimated bone strength at the distal radius. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2013) 98(5):1923–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Singhal V, Tulsiani S, Campoverde KJ, Mitchell DM, Slattery M, Schorr M, Miller KK, Bredella MA, Misra M, Klibanski A: Impaired bone strength estimates at the distal tibia and its determinants in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Bone (2018) 106:61–68.** [This is the first study to evaluate bone structure and strength at the distal tibia using HR-pQCT in female adolescents and young adults with anorexia nervosa, demonstrating that females with anorexia nervosa have lower vBMD, greater cortical porosity, lower trabecular number, and more rod (versus plate)-like trabecular bone, which result in lower strength estimates independent of aBMD.]

- [21].DiVasta AD, Feldman HA, O’Donnell JM, Long J, Leonard MB, Gordon CM: Skeletal outcomes by peripheral quantitative computed tomography and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA (2016) 27(12):3549–3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang J, Stein EM, Zhou B, Nishiyama KK, Yu YE, Shane E, Guo XE: Deterioration of trabecular plate-rod and cortical microarchitecture and reduced bone stiffness at distal radius and tibia in postmenopausal women with vertebral fractures. Bone (2016) 88:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Bachmann KN, Schorr M, Bruno AG, Bredella MA, Lawson EA, Gill CM, Singhal V, Meenaghan E, Gerweck AV, Slattery M, Eddy KT et al. : Vertebral volumetric bone density and strength are impaired in women with low-weight and atypical anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2017) 102(1):57–68.* [This study reported that using DSM-5 criteria, vertebral BMD and estimated strength measured by QCT are impaired in women with both anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa compared to controls, and are associated with low BMI and endocrine dysfunction, both current and previous.]

- [24].Brooks ER, Ogden BW, Cavalier DS: Compromised bone density 11.4 years after diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. Journal of women’s health (1998) 7(5):567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hartman D, Crisp A, Rooney B, Rackow C, Atkinson R, Patel S: Bone density of women who have recovered from anorexia nervosa. The International journal of eating disorders (2000) 28(1):107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mueller SM, Immoos M, Anliker E, Drobnjak S, Boutellier U, Toigo M: Reduced bone strength and muscle force in women 27 years after anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2015) 100(8):2927–2933.* [In this study, the authors reports that alterations in bone mass and geometry using peripheral QCT at the distal tibia may persist in women with anorexia nervosa for years (mean 27 years) after recovery of active eating disorder symptoms.]

- [27].Misra M, Aggarwal A, Miller KK, Almazan C, Worley M, Soyka LA, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Effects of anorexia nervosa on clinical, hematologic, biochemical, and bone density parameters in community-dwelling adolescent girls. Pediatrics (2004) 114(6):1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Miller KK, Lee EE, Lawson EA, Misra M, Minihan J, Grinspoon SK, Gleysteen S, Mickley D, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Determinants of skeletal loss and recovery in anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2006) 91(8):2931–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Abella E, Feliu E, Granada I, Milla F, Oriol A, Ribera JM, Sanchez-Planell L, Berga LI, Reverter JC, Rozman C: Bone marrow changes in anorexia nervosa are correlated with the amount of weight loss and not with other clinical findings. American journal of clinical pathology (2002) 118(4):582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, Misra M, Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Ghomi RH, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A: Increased bone marrow fat in anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2009) 94(6):2129–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR, Breggia A, Miller KK, Klibanski A: Preadipocyte factor-1 is associated with marrow adiposity and bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2010) 95(1):407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Schellinger D, Lin CS, Lim J, Hatipoglu HG, Pezzullo JC, Singer AJ: Bone marrow fat and bone mineral density on proton mr spectroscopy and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry: Their ratio as a new indicator of bone weakening. AJR American journal of roentgenology (2004) 183(6):1761–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Daley SM, Miller KK, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A, Torriani M: Marrow fat composition in anorexia nervosa. Bone (2014) 66:199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Newton AL, Hanks LJ, Ashraf AP, Williams E, Davis M, Casazza K: Macronutrient intake influences the effect of 25-hydroxy-vitamin d status on metabolic syndrome outcomes in african american girls. Cholesterol (2012) 2012:581432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ecklund K, Vajapeyam S, Mulkern RV, Feldman HA, O’Donnell JM, DiVasta AD, Gordon CM: Bone marrow fat content in 70 adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa: Magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment. Pediatric radiology (2017) 47(8):952–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman D, Miller KK, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, Mendes N, Misra M, Klibanski A: Inhibition of pref-1 (preadipocyte factor 1) by oestradiol in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa is associated with improvement in lumbar bone mineral density. Clinical endocrinology (2013) 79(3):326–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Haagensen AL, Feldman HA, Ringelheim J, Gordon CM: Low prevalence of vitamin d deficiency among adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA (2008) 19(3):289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Gatti D, El Ghoch M, Viapiana O, Ruocco A, Chignola E, Rossini M, Giollo A, Idolazzi L, Adami S, Dalle Grave R: Strong relationship between vitamin d status and bone mineral density in anorexia nervosa. Bone (2015) 78:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Giollo A, Idolazzi L, Caimmi C, Fassio A, Bertoldo F, Dalle Grave R, El Ghoch M, Calugi S, Bazzani PV, Viapiana O, Rossini M et al. : Vitamin d levels strongly influence bone mineral density and bone turnover markers during weight gain in female patients with anorexia nervosa. The International journal of eating disorders (2017) 50(9):1041–1049.* [In this 20-week observational longitudinal study of 91 adolescent girls and women with anorexia nervosa, weight gain was associated with an increase in spinal BMD, but only in the groups of subjects with 25OHvitD levels ≥30 ng/mL, suggesting that maintaining adequate vitamin D levels during treatment may be important to maximize gains in BMD associated with weight recovery.]

- [40].Maimoun L, Guillaume S, Lefebvre P, Philibert P, Bertet H, Picot MC, Gaspari L, Paris F, Seneque M, Dupuys AM, Courtet P et al. : Evidence of a link between resting energy expenditure and bone remodelling, glucose homeostasis and adipokine variations in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA (2016) 27(1):135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Waugh EJ, Woodside DB, Beaton DE, Cote P, Hawker GA: Effects of exercise on bone mass in young women with anorexia nervosa. Medicine and science in sports and exercise (2011) 43(5):755–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Misra M, Le Clair M, Mendes N, Miller KK, Lawson E, Meenaghan E, Weigel T, Ebrahimi S, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Use of ssris may impact bone density in adolescent and young women with anorexia nervosa. CNS spectrums (2010) 15(9):579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Moura C, Bernatsky S, Abrahamowicz M, Papaioannou A, Bessette L, Adachi J, Goltzman D, Prior J, Kreiger N, Towheed T, Leslie WD et al. : Antidepressant use and 10-year incident fracture risk: The population-based canadian multicentre osteoporosis study (camos). Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA (2014) 25(5):1473–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Solmi M, Veronese N, Sergi G, Luchini C, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Ussher M, Thapa-Chhetri N, Fornaro M et al. : The association between smoking prevalence and eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (2016) 111(11):1914–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].van Coeverden SC, Netelenbos JC, de Ridder CM, Roos JC, Popp-Snijders C, Delemarre-van de Waal HA: Bone metabolism markers and bone mass in healthy pubertal boys and girls. Clinical endocrinology (2002) 57(1):107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Soyka LA, Misra M, Frenchman A, Miller KK, Grinspoon S, Schoenfeld DA, Klibanski A: Abnormal bone mineral accrual in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2002) 87(9):4177–4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Westmoreland P, Krantz MJ, Mehler PS: Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia. The American journal of medicine (2016) 129(1):30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Castro J, Toro J, Lazaro L, Pons F, Halperin I: Bone mineral density in male adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2002) 41(5):613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schneider M, Fisher M, Weinerman S, Lesser M: Correlates of low bone density in females with anorexia nervosa. International journal of adolescent medicine and health (2002) 14(4):297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Gottsch ML, Cunningham MJ, Smith JT, Popa SM, Acohido BV, Crowley WF, Seminara S, Clifton DK, Steiner RA: A role for kisspeptins in the regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the mouse. Endocrinology (2004) 145(9):4073–4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Miller KK, Grinspoon S, Gleysteen S, Grieco KA, Ciampa J, Breu J, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Preservation of neuroendocrine control of reproductive function despite severe undernutrition. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2004) 89(9):4434–4438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Miller KK, Lawson EA, Mathur V, Wexler TL, Meenaghan E, Misra M, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Androgens in women with anorexia nervosa and normal-weight women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2007) 92(4):1334–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Riggs BL: The mechanisms of estrogen regulation of bone resorption. The Journal of clinical investigation (2000) 106(10):1203–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Modder UI, Clowes JA, Hoey K, Peterson JM, McCready L, Oursler MJ, Riggs BL, Khosla S: Regulation of circulating sclerostin levels by sex steroids in women and in men. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2011) 26(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ostrowska Z, Ziora K, Oswiecimska J, Swietochowska E, Szapska B, Wolkowska-Pokrywa K, Dyduch A: Rankl/rank/opg system and bone status in females with anorexia nervosa. Bone (2012) 50(1):156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Maimoun L, Guillaume S, Lefebvre P, Philibert P, Bertet H, Picot MC, Gaspari L, Paris F, Courtet P, Thomas E, Mariano-Goulart D et al. : Role of sclerostin and dickkopf-1 in the dramatic alteration in bone mass acquisition in adolescents and young women with recent anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2014) 99(4):E582–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman DK, Miller KK, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, Mendes N, Klibanski A, Misra M: Sclerostin levels and bone turnover markers in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescent girls. Bone (2012) 51(3):474–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kandemir N, Becker K, Slattery M, Tulsiani S, Singhal V, Thomas JJ, Coniglio K, Lee H, Miller KK, Eddy KT, Klibanski A et al. : Impact of low-weight severity and menstrual status on bone in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. The International journal of eating disorders (2017) 50(4):359–369.** [This is the first study to report direct statistical comparisons of BMD across the DSM-5 anorexia nervosa spectrum in female adolescents, demonstrating that the prevalence of a spine or hip BMD Z-score <−1 is comparable between those who are currently low weight and those who are not currently low weight.]

- [59].Idolazzi L, El Ghoch M, Dalle Grave R, Bazzani PV, Calugi S, Fassio S, Caimmi C, Viapiana O, Bertoldo F, Braga V, Rossini M et al. : Bone metabolism in patients with anorexia nervosa and amenorrhoea. Eating and weight disorders : EWD (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Misra M, Miller KK, Bjornson J, Hackman A, Aggarwal A, Chung J, Ott M, Herzog DB, Johnson ML, Klibanski A: Alterations in growth hormone secretory dynamics in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and effects on bone metabolism. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2003) 88(12):5615–5623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Stoving RK, Veldhuis JD, Flyvbjerg A, Vinten J, Hangaard J, Koldkjaer OG, Kristiansen J, Hagen C: Jointly amplified basal and pulsatile growth hormone (gh) secretion and increased process irregularity in women with anorexia nervosa: Indirect evidence for disruption of feedback regulation within the gh-insulin-like growth factor i axis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (1999) 84(6):2056–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ohlsson C, Bengtsson BA, Isaksson OG, Andreassen TT, Slootweg MC: Growth hormone and bone. Endocrine reviews (1998) 19(1):55–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hotta M, Fukuda I, Sato K, Hizuka N, Shibasaki T, Takano K: The relationship between bone turnover and body weight, serum insulin-like growth factor (igf) i, and serum igf-binding protein levels in patients with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2000) 85(1):200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Lawson EA, Miller KK, Bredella MA, Phan C, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosenblum L, Donoho D, Gupta R, Klibanski A: Hormone predictors of abnormal bone microarchitecture in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone (2010) 46(2):458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Misra M, Miller KK, Almazan C, Ramaswamy K, Lapcharoensap W, Worley M, Neubauer G, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Alterations in cortisol secretory dynamics in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and effects on bone metabolism. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2004) 89(10):4972–4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lawson EA, Donoho D, Miller KK, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Lydecker J, Wexler T, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Hypercortisolemia is associated with severity of bone loss and depression in hypothalamic amenorrhea and anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2009) 94(12):4710–4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Jia D, O’Brien CA, Stewart SA, Manolagas SC, Weinstein RS: Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoclasts to increase their life span and reduce bone density. Endocrinology (2006) 147(12):5592–5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lawson EA, Donoho DA, Blum JI, Meenaghan EM, Misra M, Herzog DB, Sluss PM, Miller KK, Klibanski A: Decreased nocturnal oxytocin levels in anorexia nervosa are associated with low bone mineral density and fat mass. The Journal of clinical psychiatry (2011) 72(11):1546–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Hamrick MW, Pennington C, Newton D, Xie D, Isales C: Leptin deficiency produces contrasting phenotypes in bones of the limb and spine. Bone (2004) 34(3):376–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cornish J, Callon KE, Bava U, Lin C, Naot D, Hill BL, Grey AB, Broom N, Myers DE, Nicholson GC, Reid IR: Leptin directly regulates bone cell function in vitro and reduces bone fragility in vivo. The Journal of endocrinology (2002) 175(2):405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, Liu X, Zhao L, Parker KL, Armstrong D, Ducy P, Karsenty G: Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell (2002) 111(3):305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Misra M, Miller KK, Kuo K, Griffin K, Stewart V, Hunter E, Herzog DB, Klibanski A: Secretory dynamics of ghrelin in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescents. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism (2005) 289(2):E347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Utz AL, Lawson EA, Misra M, Mickley D, Gleysteen S, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, Miller KK: Peptide yy (pyy) levels and bone mineral density (bmd) in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone (2008) 43(1):135–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wong IP, Driessler F, Khor EC, Shi YC, Hormer B, Nguyen AD, Enriquez RF, Eisman JA, Sainsbury A, Herzog H, Baldock PA: Peptide yy regulates bone remodeling in mice: A link between gut and skeletal biology. PloS one (2012) 7(7):e40038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Grinspoon S, Thomas E, Pitts S, Gross E, Mickley D, Miller K, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Prevalence and predictive factors for regional osteopenia in women with anorexia nervosa. Annals of internal medicine (2000) 133(10):790–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Herzog W, Minne H, Deter C, Leidig G, Schellberg D, Wuster C, Gronwald R, Sarembe E, Kroger F, Bergmann G, et al. : Outcome of bone mineral density in anorexia nervosa patients 11.7 years after first admission. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (1993) 8(5):597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Klibanski A, Biller BM, Schoenfeld DA, Herzog DB, Saxe VC: The effects of estrogen administration on trabecular bone loss in young women with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (1995) 80(3):898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Strokosch GR, Friedman AJ, Wu SC, Kamin M: Effects of an oral contraceptive (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) on bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine (2006) 39(6):819–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Golden NH, Lanzkowsky L, Schebendach J, Palestro CJ, Jacobson MS, Shenker IR: The effect of estrogen-progestin treatment on bone mineral density in anorexia nervosa. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology (2002) 15(3):135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Weissberger AJ, Ho KK, Lazarus L: Contrasting effects of oral and transdermal routes of estrogen replacement therapy on 24-hour growth hormone (gh) secretion, insulin-like growth factor i, and gh-binding protein in postmenopausal women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (1991) 72(2):374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Sim LA, McGovern L, Elamin MB, Swiglo BA, Erwin PJ, Montori VM: Effect on bone health of estrogen preparations in premenopausal women with anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analyses. The International journal of eating disorders (2010) 43(3):218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Misra M, Katzman D, Miller KK, Mendes N, Snelgrove D, Russell M, Goldstein MA, Ebrahimi S, Clauss L, Weigel T, Mickley D et al. : Physiologic estrogen replacement increases bone density in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (2011) 26(10):2430–2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Miller KK, Meenaghan E, Lawson EA, Misra M, Gleysteen S, Schoenfeld D, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Effects of risedronate and low-dose transdermal testosterone on bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2011) 96(7):2081–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Gordon CM, Grace E, Emans SJ, Feldman HA, Goodman E, Becker KA, Rosen CJ, Gundberg CM, LeBoff MS: Effects of oral dehydroepiandrosterone on bone density in young women with anorexia nervosa: A randomized trial. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2002) 87(11):4935–4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Grinspoon S, Thomas L, Miller K, Herzog D, Klibanski A: Effects of recombinant human igf-i and oral contraceptive administration on bone density in anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2002) 87(6):2883–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Golden NH, Iglesias EA, Jacobson MS, Carey D, Meyer W, Schebendach J, Hertz S, Shenker IR: Alendronate for the treatment of osteopenia in anorexia nervosa: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2005) 90(6):3179–3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Levy S, Fayez I, Taguchi N, Han JY, Aiello J, Matsui D, Moretti M, Koren G, Ito S: Pregnancy outcome following in utero exposure to bisphosphonates. Bone (2009) 44(3):428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Stathopoulos IP, Liakou CG, Katsalira A, Trovas G, Lyritis GG, Papaioannou NA, Tournis S: The use of bisphosphonates in women prior to or during pregnancy and lactation. Hormones (Athens, Greece) (2011) 10(4):280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Fazeli PK, Wang IS, Miller KK, Herzog DB, Misra M, Lee H, Finkelstein JS, Bouxsein ML, Klibanski A: Teriparatide increases bone formation and bone mineral density in adult women with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism (2014) 99(4):1322–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]