Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is one of the most common causes of intellectual and developmental disabilities in girls, and is caused by mutations in the gene encoding methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2). Here we will review our current understanding of RTT, the landscape of pathogenic mutations and function of MeCP2, and culminate with recent advances elucidating the distinct DNA methylation landscape in the brain that may explain why disease symptoms are delayed and selective to the nervous system.

Introduction

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a progressive neurological disorder mostly affecting young girls. In typical RTT, the girls appear normal for the first 6-18 months of life, then they fail to achieve new developmental milestones and show regression in any acquired language, social and motor skills. Purposeful hand movements are replaced with stereotypic hand wringing and affected individuals have difficulty learning and develop debilitating motor and autonomic symptoms as the disorder progresses [1–3]. The majority of classic RTT cases (95%), as well as the generally less severe “atypical” RTT (75%)[1], are caused by loss-of-function mutations in the X-linked methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene [4]. The onset and symptoms may vary as a function of X-inactivation patterns of the mutant allele in females[5] and the specific mutation in both sexes, yet the disorder invariably progresses[6]. Through the recognition of a related disorder in which MECP2 is duplicated[7], it is clear that gain-of-function of this gene also causes disease. In fact, triplication of the MECP2 gene causes more severe disease symptoms [8], highlighting how the brain is exceptionally sensitive MeCP2 dosage. Mutations in MECP2 also cause psychiatric symptoms of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder[2].

MeCP2 was identified as the founding member of a class of proteins that bind to methylated cytosine followed by guanine in the mammalian genome[9,10]. Mutations that disrupt MeCP2 function are causative for RTT[4] and lead to aberrant gene expression[11,12], concomitant with altered cell morphology[13–16], circuit dysfunction[17] and ultimately patient symptoms. The molecular mechanism by which MeCP2 causes these changes, and what underlies the delayed and complex nervous system dysfunction has remained unclear. Recent studies aimed at elucidating the function MeCP2 and its ability bind the newly defined DNA methylation landscape in the brain is providing insight into the molecular pathogenesis of the disease.

MeCP2 and pathogenicity of disease-causing mutations

MeCP2 is a highly conserved protein with homologs identified in all vertebrate species down to jawless fish [18]. It contains several conserved motifs and two major structurally discrete domains: the methyl binding domain (MBD) [19] and the transcriptional repressor domain (TRD) [20] which binds the transcriptional co-repressor complex (NCoR/SMRT) through a region known as the NCoR interaction domain (NID) (Figure 1A) [21]. The gene encoding MeCP2 spans 4 exons that are alternatively spliced to create two isoforms differing only by their N-terminal amino acids and molecular weight. The major and longer isoform in the brain is “MECP2_el” [22,23], though historically most studies have used the shorter, “MECP2_e2”, isoform sequence when referring to mutations. While there are various missense mutations in MECP2 that are found in the general population, pathogenic point mutations are concentrated in the MBD, TRD, and the C-terminal region (C-term). In addition, missense mutations have been identified in other evolutionarily conserved sequences as well, including the the AT-Hook regions[24–26] suggesting important function. In contrast to point mutations, the more frequently occurring pathogenic mutations that cause early truncations or frameshifts are distributed more broadly across the gene (Figure 1A) [27]. The majority of disease-causing mutations arise via de novo C to T transitions at CpG dinucleotides in the paternal germline[28](RettBASE[27]: http://mecp2.chw.edu.au and ClinVar: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/].

Figure 1. Pathogenic mutations in MECP2 and disruption of key functional interactions.

A) Mutations in MECP2 gene reported in RettBase and ClinVar that are known to cause disease. Also included are likely pathogenic point mutations from both databases. B) Crystal structure of the MBD of MeCP2 bound to methylated DNA[30] (PDB code: 3C2I). C) Crystal structure of NID sequence of MeCP2 in complex with C-terminal WD40 domain of TBLR1[31]. Highlighted in red and blue in panels B and C are known pathogenic and likely pathogenic mutations, respectively.

Although MeCP2 was identified in 1992[9,10], elucidating the tertiary structure of the protein has been challenging owing to most of the protein being unstructured in solution[29]. The crystal structure of the MBD binding to methylated DNA was solved allowing for visualization of the potential effect of disease causing mutations[30] (Figure 1B). Recently, the structure of the NID in complex with C-terminal WD40 domain of TBLR1, a member of the NCOR/SMRT complex, was solved[31] (Figure 1C). Structural modeling demonstrated how RTT-causing mutations in the NID of MeCP2 are incompatible with complex formation, and mutating interface residues on TBL1/TBLR1 abolishes the interaction with the NID of MeCP2 in vitro and in cells. While no patients diagnosed with classic RTT have mutations in TBL1/TBLR1, missense mutations in TBLR1 that disrupt the interaction with MeCP2 have been reported in patients with sporadic autism and developmental delay suggesting this interaction is important for normal brain function [31]. However, the extent to which TBL1/TBLR1 and MeCP2 functionally overlap remains to be determined.

Mice lacking Mecp2 were developed shortly after the genetic link to RTT was established[32,33]. Female mice heterozygous for aMecp2 null allele recapitulate many RTT-like symptoms, whereas male null mice display severe neurological symptoms and premature death mirroring the difference in disease severity between females and males[34]. These mice, together with mice lacking Mecp2 in specific cell types, have shaped much of our understanding for the disease to date, including the important concepts that RTT-like symptoms are mostly due to brain dysfunction[32,33,35] and arise in a cell-specific manner[11,36–38]. A mouse model mimicking a protein truncation found in children with RTT displayed an attenuated phenotype [39] demonstrating that individual mutations give rise to a spectrum of symptoms in mouse models as they do in humans, and highlighted the value of modeling diverse mutations to define their pathogenesis. Since then, the community has developed several more such models, prioritizing the most frequently occurring mutations in MEPC2 to encompass 7 of the top 10 disease causing mutations[26,40–44] (total of 41.15% of RTT cases. RettBase[27]: http://mecp2.chw.edu.au). These models showed that the severity of the effect of an individual mutation on MeCP2 function correlates with a more severe disease phenotype.

Recent modeling of the P255R patient mutation in the TRD, and several mutations identified in the C-terminal region of MECP2 (P322L, L386Hfs*5 and P389X), revealed that these mutations lower protein levels or alter binding to NCOR/SMRT[45]. Another study generated a knock-in allelic series of Mecp2 in which conserved regions were serially removed[46]. Compared to Mecp2 knockout mice, mice harboring these Mecp2 mutants show drastic improvement in health, though the most severely altered Mecp2 mutant mouse, lacking the N-, C- and ID, shows some RTT-like symptoms. Health of Mecp2 null mice could be improved if the most altered version of Mecp2 was re-expressed in adult mice, as well as if this same allele was delivered to Mecp2 null mice virally at birth. Though the most ‘radically truncated’ version of Mecp2 does not fully compensate, these data are in line with the MBD and the NID region of the TRD being most critical for MeCP2 function.

At the molecular level, loss of MeCP2 causes broad, though subtle, gene expression changes. Two recent studies investigated gene expression changes in the context of different cell-types, pathogenic mutations and in the female RTT brain in mice and humans[44,47]. Together with other studies these data reinforce that though the underlying mechanism of MeCP2 is likely conserved between neuronal types, individual patient mutations may disrupt specific aspects of MeCP2 function to cause unique molecular signatures that drive patient phenotypes in a handful of ways: altering methylated DNA binding specificity, disrupting post-translational modifications (PTMs)[48], changing protein levels by altering protein or mRNA stability, loss of key binding partners, or a combination of these processes.

The distinct methylation landscape in the brain and MeCP2’s role as a reader

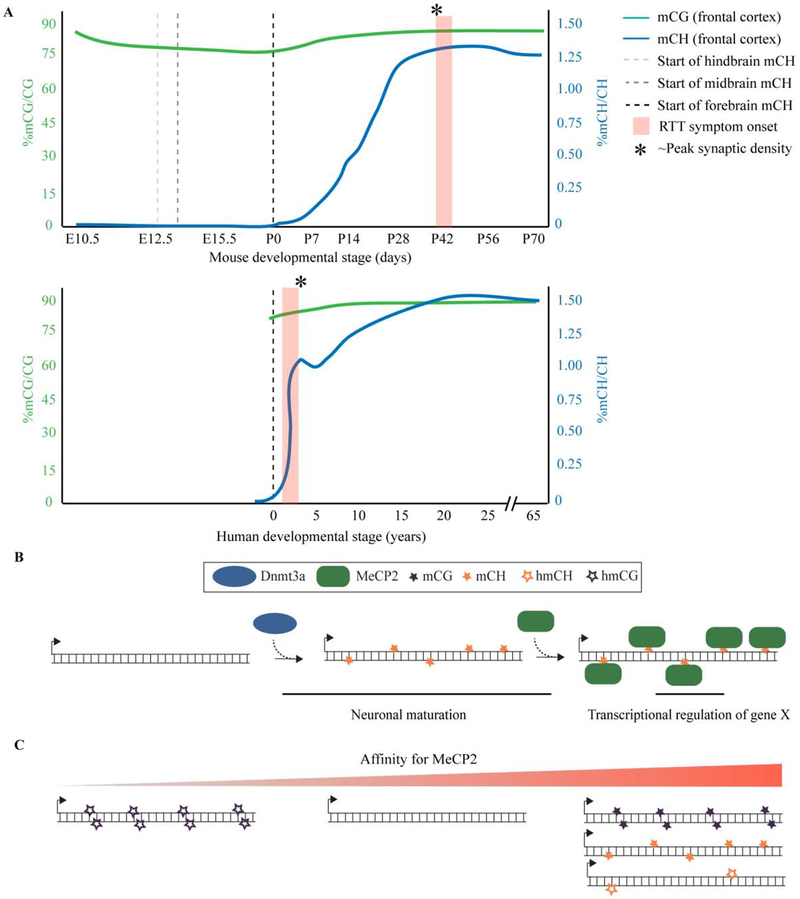

Much of the evolution in our understanding of MeCP2 function over the past few years is rooted in primary discoveries made by reexamining DNA methylation in the mammalian brain at base pair resolution. Traditionally, DNA methylation was thought to occur exclusively on the C5 position of cytosine nucleotides followed by guanine (methylated CpG, or “mCG”); however, in 2013 it was discovered that non-CpG methylation (or “mCH”, where H is A, T or C), along with hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC), accumulates after birth in neurons of the maturing mammalian brain[49,50]. Since then studies have shown that mCH patterns are highly cell-type specific[51]. In fact, new methods profiling methylation at a single-cell level are able to define cell-types in the brain of mice and humans with high sensitivity[52]. Looking longitudinally across different brain regions it was demonstrated that the onset of mCH accumulation is not exclusively postnatal, but rather brain region specific and is in step with the developmental timing for each regions maturation [53]. The dynamic accumulation of mCH in the brain are summarized in Figure 2A. In all, these data argue that the epigenetic program that drives accumulation of mCH and hmC is an integral part of dynamic gene regulation to influence neuron subtype specific function.

Figure 2. Accumulation of brain specific methylation and MeCP2 recruitment in the developing mouse brain.

A) Summarized are changes in mCG and mCH methylation from two studies[49,53] in different regions of the mouse and human brain during development. Also indicated are the timing of Rett symptom onset in mice (~6weeks for hemizygous males [shown], ~16 weeks for heterozygous females [not shown]) and humans (6-18 months), as well as when synapse numbers are at their highest. B) Model showing recruitment of MeCP2 to mCH sites as they are written over development. A gene with only mCH is used here as an illustration, however in the brain, genes are typically marked with complex methylation patterns. C) Illustrated are genes with no methylation and methyl marks in different contexts in relation the binding affinity of MeCP2.

Soon after the initial discovery of mCH in the brain, three studies demonstrated that MeCP2 binds to mCH in in vivo[54–56], where the majority of mCH sites are in the CAC context [56]. This binding coincides with many genes misregulated in Mecp2 null mice suggesting that binding to mCH during neuronal maturation is a critical part of MeCP2’s molecular mechanism. This raised the intriguing possibility that the reason for the delayed CNS specific symptoms in RTT patients is due to the functional binding of MeCP2 at postnatal methylation sites that are unique to neurons in the brain[55].

In mammals, DNA methylation is written by de novo methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, and maintained by Dnmt1 in the mCG context[57]. In the developing mouse brain Dnmt3b is active early but turns off at ~ E15.5, whereas Dnmt3a is active early [58] and shows peak expression at postnatal week 2 in the cortex[49]. Studies have shown that Dnmt3a is solely responsible for writing mCH in the brain[56]. Extending our knowledge of this pathway, a recent study[59] finds that Dnmt3a binds to lowly expressed genes at postnatal week 2 in the mouse cortex. This early binding correlates well with the adult pattern of mCH methylation, suggesting that the binding of Dnmt3a to sites is deterministic for catalysis and that once written mCH is likely stable. The authors find that altering chromatin state by activity changes or genetic manipulation of a key histone modifying complex subunit can alter binding and methylation by Dnmt3a. These data are consistent with previous literature showing that Dnmt3a function is modulated by histone modifications[60–65], and suggest that changes to chromatin state in the developmental time window when mCH is set can have lasting consequences on the methylation landscape in a mature brain and the proteins that bind methylation by proxy. Analyzing gene expression from single-nuclei RNA-sequencing, revealed that genes with higher levels of mCH in wild-type neurons tend to be upregulated in Dnmt3a knockout neurons, in line with mCH correlating most highly with gene repression in the brain[49]. Genes with higher mCH levels tend to have more MeCP2 binding, and preforming cell-type specific ChIP and methylation sequencing from immunopurified inhibitory neurons of interest demonstrates that MeCP2 targets follow the cell-specific methylation pattern. These data could explain recent findings that gene expression changes are cell-type specific[44,47], and the authors put forth a model that Dnmt3a and MeCP2 work in-step to regulate mCH marked genes in the postnatal brain. Still, another recent study argues that total mC read by MeCP2 best explains the gene expression changes observed in Mecp2 null neurons[66]. These authors show that MeCP2 could bind to symmetric mCG methylation with similar affinity to asymmetric mCAC methylation. They propose this is due to the thymine on the opposite strand that pairs with the adenosine of the mCAC which can also be viewed as a pseudo methylation site, or 5-methyluracil. Though, recent biochemical and biophysical analysis suggests that MeCP2 may bind to mCAC in a strand specific manner[67].

The reversal of cytosine methylation is achieved by serial oxidation by dioxygenases of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) protein family, where the product of the first round of oxidation is hmC [68]. Though hmC was discovered in the brain several years ago[50], more recently it was shown to accumulate in the same time window of brain development as mCH[49] to suggest a critical contribution to this epigenetic pathway. MeCP2 was reported to bind to hmC[69], though new studies propelled a deeper understanding[66,70]. Here again the sequence context for this modification plays a major role in determining MeCP2 affinity, where MeCP2 binds to hydroxymethylated sites in the hmCAC context, but not hmCG that is found more frequently in the brain. Investigating granule neurons in the cerebellum, Mellen et al[70] show that hydroxymethylation accumulates in euchromatin and that higher ratios of hmCG/mCG within gene bodies is positively correlated with gene expression and inversely correlated with MeCP2 occupancy. In contrast, the ratio of hmCA/mCA was not predictive as hmCA and mCA are both high affinity binding sites for MeCP2, thus altering the ratio has no measurable effect on binding. The authors propose a model in which hmCG acts in opposition of mCG to “functionally demethylate” genes to inhibit MeCP2 binding and facilitate transcription.

In total, these data argue that MeCP2 binds to context specific methylated sites in neurons as they mature with different of affinities to influence gene expression (Figure 2B–C). This recruitment of MeCP2 to cell-type specific sites in neurons is a central part of its molecular mechanism and allows for proper neuronal function. These insights support the idea that patient symptoms could manifest later in life if the molecular consequences for MeCP2 dysfunction take effect only after the full methylation pattern is set several weeks or years after birth in mice and humans, respectively.

Conclusions and future directions

Decades of research have been devoted to understanding the function and mode of pathogenies for MECP2 mutations in RTT syndrome, yet key features of this disease are not fully understood. Much progress in elucidating the molecular pathogenies of different RTT causing mutations in mouse models have enlightened themes for MeCP2 dysfunction in disease. Thanks to technological advances we now know that methylation landscape in the brain is distinct in mammals and that MeCP2 is integral in recognition of these marks as they become fully written in the first few years of life in humans[49]. This critical step ensures that the protein is localized to the right places in the genome to enact its function(s) [11,12]. Importantly, these data help explain why mutations in MECP2 cause CNS specific symptoms that are classically delayed in RTT patients.

Given that mutations appear to drive pathogenesis in RTT in different ways, it seems likely that any future therapy may need to be specific to the pathogenic mutation, akin to the idea of personalized medicine. For example, patients with certain hypomorphic mutations may benefit from strategies aimed at boosting MeCP2 levels[41,71], while others that cause full loss of function for the protein may be better candidates for gene therapy approaches[72,73]. To inform such therapeutics it will be important to explore the full mutational landscape of MECP2 to see if molecular pathogenesis in RTT is in fact generalizable as outlined above. Key in this will be parallel efforts to fully define the molecular mechanism of MeCP2, including fully defining protein binding partners (over 40 are known[11]), post-translational modifications, and in what genomic context these interactions exist.

The discovery that Dnmt3a creates a unique methylation landscape in the brain has been enlightening for the function of MeCP2, the pathogenesis of RTT and the field of neuroepigenetics in general. Many important directions remain to be explored. First, the relative contribution of MeCP2 binding to methyl marks in different contexts and oxidation states to misregulated genes is unclear. Part of the problem lies in the fact that it is not clear what misregulated genes observed in Mecp2 knockout neurons are primary targets of MeCP2. Assuming MeCP2 primarily functions as repressor[11], some analysis consider genes that are upregulated to be primary targets. This view is supported by functional interactions with key co-repressor complexes[74–76] and data showing that Mecp2 null neurons have smaller nuclear size[33], which may cause general down-regulation of some genes[66]. However, MeCP2 may have other functions that might promote increased gene expression[77,78] and explain why genes are down-regulated in Mecp2 null neurons and reciprocally up-regulated in mice with double the levels of MeCP2[77], where there is not a general defect on transcription[66]. Further, long genes (>100kb) have been reported to be preferentially up-regulated upon loss of MeCP2, and it has been proposed that misregulation of these genes drive RTT phenotypes [56]. But it is noteworthy that there are many genes that are robustly misregulated that are not particularly long, and it remains unclear how much of the long-gene effect is uniquely due to MeCP2 loss and how much may be confounded by RNA-seq platforms [79]. Viewing this issue through the lens of new studies, perhaps the discrepancy stems from how the data are filtered prior to plotting (i.e. FDR cutoff for DEGs, methylation status etc.). For example, a recent paper lays out that the long gene effect is selectively observed when plotting the top 25% most mCA methylated genes[47]. Given this, perhaps the rules for MeCP2 function are predictable for a subset of genes in the genome that are long and highly methylated. If so, the challenge is to determine what the mechanism for up-regulation of short genes and down regulation of some genes upon MeCP2 loss. Alternatively, perhaps the long-gene effect is highlighting a true function for MeCP2 that is applicable to a broader set of misregulated genes where the signal is hidden in the noise of genome wide measures of MeCP2 mutants, in which the transcriptional defects are quite subtle. More work is needed to determine if the long gene effect is the primary feature for MeCP2 function and what gene expression changes upon MeCP2 loss are direct and causative for RTT symptoms.

More broadly, it will be important to formally define the relationship between Dnmt3a, MeCP2 and RTT phenotypes. Specifically, a careful comparison of behavioral phenotypes in Dnmt3a and Mecp2 knockout mice is lacking. Further it is not clear what fraction of the mCH pattern in the brain is read by MeCP2 or whether there are other functional readers for this novel epigenetic pathway. In all future studies it will be important to take a cell-specific approach as we now know the methylation patters [51] and MeCP2 binding in neurons are distinct[59]. In the end, the hope is that our understanding of the basic mechanism of MeCP2 function will help us achieve effective therapies for patients with MeCP2 related disorders.

Highlights.

Rett syndrome (RTT) is caused by mutations in the gene encoding methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MECP2)

Diverse pathogenic mutations reveal modes for MeCP2 dysfunction in children with RTT and inform molecular mechanism

MeCP2 binds to methyl marks that are set during neuronal maturation

MeCP2 has different affinities for methyl marks depending on sequence context and oxidative status

Loss of function for MeCP2 at methyl marks during neuronal maturation may underlie delayed, brain specific symptoms in RTT patients

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Rahul Krishnaraj and Dr. John Christodoulou at RettBASE for help curating an up to date list of pathogenic patient mutations in MECP2. We also are grateful to Dr. Sameer Bajikar, Dr. Jian Zhou and other members of the Zoghbi lab for insightful discussions. This work was supported by NIH/NINDS 5R01NS057819-13. HYZ is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

HYZ has a research collaboration agreement with Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and receives no funds. HYZ is a holder of US Patent 6709817: “Method of Screening Rett Syndrome by Detecting a Mutation in MECP2”.

References

- 1.Gold WA, Krishnarajy R, Ellaway C, Christodoulou J: Rett Syndrome: A Genetic Update and Clinical Review Focusing on Comorbidities. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9:167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zoghbi HY: Rett Syndrome and the Ongoing Legacy of Close Clinical Observation. Cell 2016, 167:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonard H, Cobb S, Downs J: Clinical and biological progress over 50 years in Rett syndrome. Nat Rev Neurol 2017, 13:37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY: Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet 1999, 23:185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young JI, Zoghbi HY: X-chromosome inactivation patterns are unbalanced and affect the phenotypic outcome in a mouse model of rett syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2004, 74:511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuddapah VA, Pillai RB, Shekar KV, Lane JB, Motil KJ, Skinner SA, Tarquinio DC, Glaze DG, McGwin G, Kaufmann WE, et al. : Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) mutation type is associated with disease severity in Rett syndrome. J. Med. Genet 2014, 51:152–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Esch H: MECP2 Duplication Syndrome. Mol Syndromol 2012, 2:128–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Gaudio D, Fang P, Scaglia F, Ward PA, Craigen WJ, Glaze DG, Neul JL, Patel A, Lee JA, Irons M, et al. : Increased MECP2 gene copy number as the result of genomic duplication in neurodevelopmentally delayed males. Genet. Med 2006, 8:784–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JD, Meehan RR, Henzel WJ, Maurer-Fogy I, Jeppesen P, Klein F, Bird A: Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to methylated DNA. Cell 1992, 69:905–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meehan RR, Lewis JD, Bird AP: Characterization of MeCP2, a vertebrate DNA binding protein with affinity for methylated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20:5085–5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyst MJ, Bird A: Rett syndrome: a complex disorder with simple roots. Nat. Rev. Genet 2015, 16:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip JPK, Mellios N, Sur M: Rett syndrome: insights into genetic, molecular and circuit mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 2018, 19:368–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishi N, Macklis JD: MECP2 is progressively expressed in post-migratory neurons and is involved in neuronal maturation rather than cell fate decisions. Molecidar and Cellular Neuroscience 2004, 27:306–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao H-T, Zoghbi HY, Rosenmund C: MeCP2 controls excitatory synaptic strength by regulating glutamatergic synapse number. Neuron 2007, 56:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The short-time structural plasticity of dendritic spines is altered in a model of Rett syndrome. 2011, 1:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuss DP, Boyd JD, Levin DB, Delaney KR: MeCP2 mutation results in compartment-specific reductions in dendritic branching and spine density in layer 5 motor cortical neurons of YFP-H mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7:e31896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu H, Ash RT, He L, Kee SE, Wang W, Yu D, Hao S, Meng X, Ure K, Ito-Ishida A, et al. : Loss and Gain of MeCP2 Cause Similar Hippocampal Circuit Dysfunction that Is Rescued by Deep Brain Stimulation in a Rett Syndrome Mouse Model. Neuron 2016, 91:739–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guy J, Cheval H, Selfridge J, Bird A: The role of MeCP2 in the brain. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 2011, 27:631–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nan X, Meehan RR, Bird A: Dissection of the methyl-CpG binding domain from the chromosomal protein MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21:4886–4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nan X, Campoy FJ, Bird A: MeCP2 is a transcriptional repressor with abundant binding sites in genomic chromatin. Cell 1997, 88:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyst MJ, Ekiert R, Ebert DH, Merusi C, Nowak J, Selfridge J, Guy J, Kastan NR, Robinson ND, de Lima Alves F, et al. : Rett syndrome mutations abolish the interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor. Nat. Neurosci 2013, 16:898–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kriaucionis S, Bird A: The major form of MeCP2 has a novel N-terminus generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32:1818–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mnatzakanian GN, Lohi H, Munteanu I, Alfred SE, Yamada T, MacLeod PJM, Jones JR, Scherer SW, Schanen NC, Friez MJ, et al. : A previously unidentified MECP2 open reading frame defines a new protein isoform relevant to Rett syndrome. Nat. Genet 2004, 36:339–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Liao Y, Xu M, Ji Z, Xu Y, Zhou L, Wei X, Hu P, Han P, Yang F, et al. : A novel mutation R190H in the AT-hook 1 domain of MeCP2 identified in an atypical Rett syndrome. Oncotarget 2017, 8:82156–82164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheikh TI, Harripaul R, Ayub M, Vincent JB: MeCP2 AT-Hookl mutations in patients with intellectual disability and/or schizophrenia disrupt DNA binding and chromatin compaction in vitro. Hum. Mutat 2018, 39:717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker SA, Chen Wilkins AD, Yu P, Lichtarge O, Zoghbi HY: An AT-hook domain in MeCP2 determines the clinical course of Rett syndrome and related disorders. Cell 2013, 152:984–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnaraj R, Ho G, Christodoulou J: RettBASE: Rett syndrome database update. Hum. Mutat 2017, 38:922–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trappe R, Laccone F, Cobilanschi J, Meins M, Huppke P, Hanefeld F, Engel W: MECP2 mutations in sporadic cases of Rett syndrome are almost exclusively of paternal origin. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2001, 68:1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams VH, McBryant SJ, Wade PA, Woodcock CL, Hansen JC: Intrinsic disorder and autonomous domain function in the multifunctional nuclear protein, MeCP2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282:15057–15064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho KL, McNae IW, Schmiedeberg L, Klose RJ, Bird AP, Walkinshaw MD: MeCP2 binding to DNA depends upon hydration at methyl-CpG. Mol. Cell 2008, 29:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruusvee V, Lyst MJ, Taylor C, Tamauskaite Ž, Bird AP, Cook AG: Structure of the MeCP2-TBLRl complex reveals a molecular basis for Rett syndrome and related disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114:E3243–E3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Paper revealing the protein interface between MeCP2 and TBLR1, a member of the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor complex, in molecular detail. These data along with cellular assays provide an understanding for disease pathogenies for RTT mutations within this interface.

- 32.Guy J, Hendrich B, Holmes M, Martin JE, Bird A: A mouse Mecp2-null mutation causes neurological symptoms that mimic Rett syndrome. Nat. Genet 2001, 27:322–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen RZ, Akbarian S, Tudor M, Jaenisch R: Deficiency of methyl-CpG binding protein-2 in CNS neurons results in a Rett-like phenotype in mice. Nat. Genet 2001, 27:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lombardi LM, Baker SA, Zoghbi HY: MECP2 disorders: from the clinic to mice and back. J. Clin. Invest 2015, 125:2914–2923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross PD, Guy J, Selfridge J, Kamal B, Bahey N, Tanner KE, Gillingwater TH, Jones RA, Loughrey CM, McCarroll CS, et al. : Exclusive expression of MeCP2 in the nervous system distinguishes between brain and peripheral Rett syndrome-like phenotypes. Hum. Mol. Genet 2016, 25:4389–4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito-Ishida A, Ure K, Chen H, Swann JW, Zoghbi HY: Loss of MeCP2 in Parvalbumin- and Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons in Mice Leads to Distinct Rett Syndrome-like Phenotypes. Neuron 2015, 88:651–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng X, Wang W, Lu H, He L-J, Chen W, Chao ES, Fiorotto ML, Tang B, Herrera JA, Seymour ML, et al. : Manipulations of MeCP2 in glutamatergic neurons highlight their contributions to Rett and other neurological disorders. Elife 2016, 5:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ure K, Lu H, Wang W, Ito-Ishida A, Wu Z, He L-J, Sztainberg Y, Chen W, Tang J, Zoghbi HY: Restoration of Mecp2 expression in GABAergic neurons is sufficient to rescue multiple disease features in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Elife 2016, 5:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shahbazian M, Young J, Yuva-Paylor L, Spencer C, Antalffy B, Noebels J, Armstrong D, Paylor R, Zoghbi H: Mice with truncated MeCP2 recapitulate many Rett syndrome features and display hyperacetylation of histone H3. Neuron 2002, 35:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown K, Selfridge J, Lagger S, Connelly J, De Sousa D, Kerr A, Webb S, Guy J, Merusi C, Koemer MV, et al. : The molecular basis of variable phenotypic severity among common missense mutations causing Rett syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet 2016, 25:558–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lamonica JM, Kwon DY, Goffin D, Fenik P, Johnson BS, Cui Y, Guo H, Veasey S, Zhou Z: Elevating expression of MeCP2 T158M rescues DNA binding and Rett syndrome-like phenotypes. J. Clin. Invest 2017, 127:1889–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawson-Yuen A, Liu D, Han L, Jiang ZI, Tsai GE, Basu AC, Picker J, Feng J, Coyle JT: Ube3a mRNA and protein expression are not decreased in Mecp2R168X mutant mice. Brain Res. 2007, 1180:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heckman LD, Chahrour MH, Zoghbi HY: Rett-causing mutations reveal two domains critical for MeCP2 function and for toxicity in MECP2 duplication syndrome mice. Elife 2014, 3:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson BS, Zhao Y-T, Fasolino M, Lamonica JM, Kim YJ, Georgakilas G, Wood KH, Bu D, Cui Y, Goffin D, et al. : Biotin tagging of MeCP2 in mice reveals contextual insights into the Rett syndrome transcriptome. Nature Medicine 2017, 23:1203–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *These authors create a tagged version of WT MeCP2, as well as the same tagged allele harboring two patient mutations, which can be selectively biotinylated upon Cre-induction in a cell population of interest. Using these mice the authors preform total RNA-seq on sorted nuclei from excitatory or inhibitory neurons in the forebrain. The authors also used their engineered mice to measure gene expression changes in MeCP2 mutant and WT neurons in the female RTT brain for the first time.

- 45.Guy J, Alexander-Howden B, FitzPatrick L, DeSousa D, Koerner MV, Selfridge J, Bird A: A mutation-led search for novel functional domains in MeCP2. Hum. Mol. Genet 2018, 27:2531–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study explores the pathogenesis of mutations in the TRD and C-terminal region of MECP2. The authors expand our understanding of the ways loss-of-function mutations in the gene can drive disease phenotypes.

- 46.Tillotson R, Selfridge J, Koerner MV, Gadalla KKE, Guy J, De Sousa D, Hector RD, Cobb SR, Bird A: Radically truncated MeCP2 rescues Rett syndrome-like neurological defects. Nature 2017, 550:398–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *Authors use evolutionary conservation to minimize the MeCP2 protein in vivo to show that the MBD and TRD are most critical for MeCP2 function.

- 47.Renthal W, Boxer LD, Hrvatin S, Li E, Silberfeld A, Nagy MA, Griffith EC, Vierbuchen T, Greenberg ME : Characterization of human mosaic Rett syndrome brain tissue by single-nucleus RNA sequencing. Nat. Neurosci 2018, 21:1670–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * These authors develop a method that relies on single nucleotide polymorphisms to identify wild type verses MECP2 mutant cells in the human RTT brain. They use this to analyze gene expression changes and its relationship to methylation at the single nuclei level.

- 48.Bellini E, Pavesi G, Barbiero I, Bergo A, Chandola C, Nawaz MS, Rusconi L, Stefanelli G, Strollo M, Valente MM, et al. : MeCP2 post-translational modifications: a mechanism to control its involvement in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis? Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lister R, Mukamel EA, Nery JR, Urich M, Puddifoot CA, Johnson ND, Lucero J, Huang Y, Dwork AJ, Schultz MD, et al. : Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science 2013, 341:1237905–1237905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kriaucionis S, Heintz N: The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science 2009, 324:929–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mo A, Mukamel EA, Davis FP, Luo C, Henry GL, Picard S, Urich MA, Nery JR, Sejnowski TJ, Lister R, et al. : Epigenomic Signatures of Neuronal Diversity in the Mammalian Brain. Neuron 2015, 86:1369–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo C, Keown CL, Kurihara L, Zhou J, He Y, Li J, Castanon R, Lucero J, Nery JR, Sandoval JP, et al. : Single-cell methylomes identify neuronal subtypes and regulatory elements in mammalian cortex. Science 2017, 357:600–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Y, Hariharan M, Gorkin DU, Dickel DE, bioRxiv CL, 2017: Spatiotemporal DNA methylome dynamics of the developing mammalian fetus, biorxiv.org 2017, [no volume]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo JU, Su Y, Shin JH, Shin J, Li H, Xie B, Zhong C, Hu S, Le T, Fan G, et al. : Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat. Neurosci 2014, 17:215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen, Chen K, Lavery LA, Baker SA, Shaw CA, Li W, Zoghbi HY: MeCP2 binds to non-CG methylated DNA as neurons mature, influencing transcription and the timing of onset for Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2015, 112:5509–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gabel HW, Kinde B, Stroud H, Gilbert CS, Harmin DA, Kastan NR, Hemberg M, Ebert DH, Greenberg ME: Disruption of DNA-methylation-dependent long gene repression in Rett syndrome. Nature 2015, 522:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jurkowska RZ, Jeltsch A: Enzymology of Mammalian DNA Methyltransferases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 2016, 945:87–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng J, Chang H, Li E, Fan G: Dynamic expression of de novo DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in the central nervous system. J. Neurosci. Res 2005, 79:734–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stroud H, Su SC, Hrvatin S, Greben AW, Renthal W, Boxer LD, Nagy MA, Hochbaum DR, Kinde B, Gabel HW, et al. : Early-Life Gene Expression in Neurons Modulates Lasting Epigenetic States. Cell 2017, 171:1151–1164.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * These authors expand our knowledge of the mechanism of Dnmt3a dependent methylation in maturing neurons and consequences of perturbation of this program on gene regulation in the mature brain.

- 60.Otani J, Nankumo T, Arita K, Inamoto S, Ariyoshi M, Shirakawa M: Structural basis for recognition of H3K4 methylation status by the DNA methyltransferase 3A ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L domain. EMBO Rep. 2009, 10:1235–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y, Jurkowska R, Soeroes S, Rajavelu A, Dhayalan A, Bock I, Rathert P, Brandt O, Reinhardt R, Fischle W, et al. : Chromatin methylation activity of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3a/3L is guided by interaction of the ADD domain with the histone H3 tail. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38:4246–4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dhayalan A, Rajavelu A, Rathert P, Tamas R, Jurkowska RZ, Ragozin S, Jeltsch A: The Dnmt3a PWWP domain reads histone 3 lysine 36 trimethylation and guides DNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285:26114–26120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li B-Z, Huang Z, Cui Q-Y, Song X-H, Du L, Jeltsch A, Chen P, Li G, Li E, Xu G-L: Histone tails regulate DNA methylation by allosterically activating de novo methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2011, 21:1172–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guo X, Wang L, Li J, Ding Z, Xiao J, Yin X, He S, Shi P, Dong L, Li G, et al. : Structural insight into autoinhibition and histone H3-induced activation of DNMT3A. Nature 2015, 517:640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Noh K-M, Wang H, Kim HR, Wenderski W, Fang F, Li CH, Dewell S, Hughes SH, Melnick AM, Patel DJ, et al. : Engineering of a Histone-Recognition Domain in Dnmt3a Alters the Epigenetic Landscape and Phenotypic Features of Mouse ESCs. Mol. Cell 2015, 59:89–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lagger S, Connelly JC, Schweikert G, Webb S, Selfridge J, Ramsahoye BH, Yu M, He C, Sanguinetti G, Sowers LC, et al. : MeCP2 recognizes cytosine methylated tri-nucleotide and di-nucleotide sequences to tune transcription in the mammalian brain. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13:e1006793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * Study examining methylation context and how this affects MeCP2 binding affinity and how is may alter gene expression in vivo.

- 67.Sperlazza MJ, Bilinovich SM, Sinanan LM, Javier FR, Williams DC: Structural Basis of MeCP2 Distribution on Non-CpG Methylated and Hydroxymethylated DNA. J. Mol. Biol 2017, 429:1581–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *These authors use biophysical methods to determine the mode of binding of the MBD of MeCP2 to methylation in different contexts.

- 68.Shen L, Song C-X, He C, Zhang Y: Mechanism and function of oxidative reversal of DNA and RNA methylation. Anna. Rev. Biochem 2014, 83:585–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mellén M, Ayata P, Dewell S, Kriaucionis S, Heintz N: MeCP2 binds to 5hmC enriched within active genes and accessible chromatin in the nervous system. Cell 2012, 151:1417–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mellén M, Ayata P, Heintz N: 5-hydroxymethylcytosine accumulation in postmitotic neurons results in functional demethylation of expressed genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114:E7812–E7821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study shows that hmCG is a low affinity site for MeCP2 and suggests a mechanim in which MeCP2 would be displaced from mCG sites upon oxidation.

- 71.Lombardi LM, Zaghlula M, Sztainberg Y, Baker SA, Klisch TJ, Tang AA, Huang EJ, Zoghbi HY: An RNA interference screen identifies druggable regulators of MeCP2 stability. Sci Transl Med 2017, 9:eaaf7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sinnett SE, Gray SJ: Recent endeavors in MECP2 gene transfer for gene therapy of Rett syndrome. Discov Med 2017, 24:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garg SK, Lioy DT, Cheval H, McGann JC, Bissonnette JM, Murtha MJ, Foust KD, Kaspar BK, Bird A, Mandel G: Systemic delivery of MeCP2 rescues behavioral and cellular deficits in female mouse models of Rett syndrome. J. Neurosci 2013, 33:13612–13620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A: Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 1998, 393:386–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jones PL, Veenstra GJ, Wade PA, Vermaak D, Kass SU, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe AP: Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat. Genet 1998, 19:187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kokura K, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R, Nomura T, Khan MM, Shinagawa T, Yasukawa T, Colmenares C, Ishii S: The Ski protein family is required for MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276:34115–34121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chahrour M, Jung SY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STC, Qin J, Zoghbi HY: MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science 2008, 320:1224–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nott A, Cheng J, Gao F, Lin Y-T, Gjoneska E, Ko T, Minhas P, Zamudio AV, Meng J, Zhang F, et al. : Histone deacetylase 3 associates with MeCP2 to regulate FOXO and social behavior. Nat. Neurosci 2016, 19:1497–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Raman AT, Pohodich AE, Wan Y-W, Yalamanchili HK, Lowry WE, Zoghbi HY, Liu Z: Apparent bias toward long gene misregulation in MeCP2 syndromes disappears after controlling for baseline variations. Nat Commun 2018, 9:3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]