Abstract

The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) has been effective in serving people living with HIV (PLWH). Our goal was to examine the impact of the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on the program's role in HIV care and its clients. We utilized critical review to synthesize the literature on the anticipated effects of the ACA, and assess the evidence regarding the early effects of the ACA on the program and on PLWH who receive RWHAP services. To date, research on the impact of ACA on RWHAP has been fragmented. Despite the expected benefits of the ACA to PLWH, access and linkage to care, reducing inequity in HIV risk and access to care, and coping with comorbidities remain pressing challenges. There are additional gaps following ACA implementation related to immigrant care. RWHAP's proven success in addressing these challenges, and the political threats to ACA, highlight the need for maintaining the program to meet HIV care needs. More evidence on the role and impact of RWHAP in this new era is needed to guide policy and practice of care for PLWH. Additional research is needed to explore RWHAP care and its clients' health outcomes following ACA implementation, with a focus on at-risk groups such as immigrants, transgender women, homeless individuals, and PLWH struggling with mental health problems.

Keywords: HIV, Ryan White, Affordable Care Act, ACA, health care

Introduction

In 2014, more than half of the people living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States received services provided by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP)1 This safety-net program provides medication, health care, and wraparound services for uninsured and underinsured PLWH,2 with demonstrated effectiveness in increasing continuity of care, engagement in care, and the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) by its clients.1,3–5 Linkage to care and use of ART are necessary for achieving viral suppression, which in turn leads to improved individual health outcomes and a substantial reduction in HIV transmission.6 The program was designed to provide a comprehensive array of medical and support services, yet as a payer of the last resort, it cannot fully address the non-HIV-related medical needs of PLWH.7 Consequently, the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) raised uncertainty regarding the future need for the program and the care provided to its clients. Whereas numerous reviews and editorials analyzed the anticipated impact of the ACA on HIV care prior to full ACA implementation in 2014, including in the context of RWHAP,2,8–14 we were able to identify only 1 review of the literature on the impact of the ACA after implementation.15 Although that review included some RWHAP-related data and outlined directions for future research, to our knowledge scholars did not focus on the post-ACA role of the program, the impact of ACA on RWHAP services, or health outcomes of its clients. Such an examination is crucial in view of the pivotal role of the program in HIV care provision, and its implications for policy and practice.

To begin addressing this knowledge gap, we examine the research on the role of the RWHAP before the adoption of the ACA, integrate the literature on the anticipated effects of the ACA on PLWH served by the RWHAP, and examine the evidence on the early effects of the ACA on PLWH served by the RWHAP. To better understand the importance of both the RWHAP and the ACA in care for PLWH, it is important to understand the challenges facing this care.

Challenges in HIV Care in the United States

The availability of ART transformed HIV infection from a terminal illness to a chronic, treatable condition. However, 3 overarching and interrelated challenges loom over HIV care in the United States: inadequate linkage to care, inequity in HIV risk and access to care, and the high prevalence of comorbidities. Early and continued use of ART results in virologic suppression, which reduces mortality and morbidity, prevents further transmission,16 and is highly cost-effective.17 However, many PLWH experience delays in linkage to care, fail to be retained in care, or are unable to adhere to treatment. Consequently, only about half of persons diagnosed with HIV and 30% of PLWH achieve viral suppression in 2016.18 PLWH who are unaware of their HIV status or who have not achieved viral suppression are at risk of infecting others. With about 38,500 people newly diagnosed with HIV in the United States annually, effective HIV treatment is important not only for the health of individual patients, but also as a crucial public health measure.16

A related issue involves disparities in care and health outcomes. At each point of the HIV care continuum, the burden of HIV morbidity and mortality disproportionately affects vulnerable ethnic and racial minorities, young adults, sexual minorities, and people with low-income.19 The third challenge relates to treatment of comorbidities, including serious mental health disorders, substance use disorders,20 and chronic hepatitis B or C.21 Moreover, the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities such as cardiovascular, chronic kidney, and bone diseases is growing, as a result of the aging of the PLWH population, as well as a combination of HIV- and ART-related factors.22 These challenges to HIV care are further complicated by barriers created by the complex US health policies and systems, including insufficient medical insurance coverage. Before the implementation of the ACA, PLWH were at increased risk of being uninsured. In 2010, fewer than 1 in 5 PLWH had private insurance, compared with two-thirds of all Americans. About half of PLWH were enrolled in Medicaid or Medicare, and about a third were un insured. In view of the positive correlation between survival rates for PLWH and insurance coverage, lack of insurance among PLWH is a serious concern. Uninsured PLWH are typically younger, have income levels at or below the federal poverty level (FPL), and are more likely to have been homeless in the last 12 months.23 The RWHAP has a pivotal role in addressing the major care needs of PLWH, including linking clients to care, reducing inequity in HIV risk and access to care, and addressing comorbidities.

RWHAP Prior to the ACA

RWHAP was created by the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act of 199024 Its primary goals are to (a) reduce the use of costly inpatient care, (b) increase access to care for underserved populations, and (c) improve quality of life.24 One of few disease-specific programs, RWHAP is a safety network rather than a health insurance program. It is funded through a series of grant programs that are federally administered by the Health Services and Resources Administration (HRSA) HIV/AIDS Bureau to cities, states, territories, and public health districts. The funds are then distributed to regions and provider organizations to fund treatment and wrap-around services.24,25

Among the strengths of the program is its provision of funds to HIV care facilities, which are typically more effective in treating PLWH than general clinics.3,26 In addition, the program funds a wide variety of services, including primary care, training programs for health care practitioners,2 assistance in identifying sources of care, access to medications, transportation to care sites, and provision of the necessary documentation to insurers and health care practitioners.27 AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs) are a substantial component of the RWHAP, providing prescription medications to lower income, uninsured, and underinsured PLWH. In 2010, approximately one fourth of PLWH in the United States were enrolled in an ADAP, and ADAP funds accounted for 41% of the $1.93 billion in RWHAP spending in 2006.8

Receiving RWHAP services has been consistently shown to be associated with better health outcomes.1,28,29 For uninsured and underinsured PLWH, assistance from the RWHAP has resulted in significantly higher use of ART (94% for those receiving RWHAP assistance versus 52% for those without) and virologic suppression (77% for those with assistance versus 39% without without).3 Likewise, for insured PLWH, RWHAP assistance is associated with greater use of ART (96% for those with RWHAP assistance versus 90% for those without assistance) and higher rates of virologic suppression (81% for those with assistance verses 76% for those without), likely due to the provision of wraparound and support services, including case management, which helps retain persons in medical care.3,29

The ACA and Its Expected Implications for PLWH

The ACA was signed into law in March 2010 (Public Law 111–148) with the goals of expanding medical insurance coverage, reforming the individual medical insurance market, reducing the rate of increases in health care spending, and improving the quality of clinical care.30 It was expected to have substantial implications for PLWH. An important goal of the ACA was to reduce the number of uninsured Americans, which was expected to benefit the many uninsured PLWH.2 In the private health insurance market, the ACA prohibits insurance companies from denying insurance due to preexisting conditions, including HIV infection.2 Allowing young adults to stay on their parents' private insurance plans until they are 26 years old was expected to benefit some of the younger PLWH.31 Moreover, individuals with income between 100% and 400% of the FPL qualify for tax credits and subsidies for private insurance plans operated through the health insurance marketplace.2

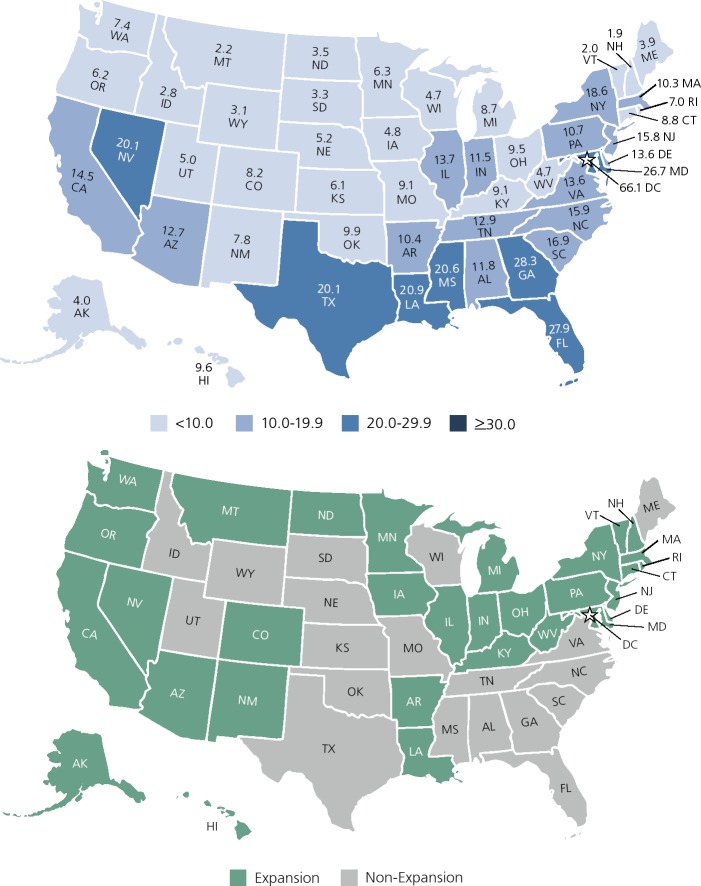

The ACA provides incentives to states to expand eligibility for Medicaid for their residents. Before the expansion, in many states individuals had to both fall below a threshold income and fit into a specific eligibility category, such as disability, having children, or being pregnant.2 Under the ACA's Medicaid expansion, categorical eligibility requirements are eliminated and all Americans with incomes below 138% of the FPL are eligible for Medicaid. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, however, the Supreme Court ruled that the methods the Act used to influence states to adopt the Medicaid expansion were too coercive and that states must have the option of deciding whether or not to expand Medicaid without facing the penalty of losing all Medicaid funding.2 Given this choice, 19 states chose not to expand Medicaid eligibility.32 With high levels of health disparities, including among PLWH in many of these states, the uneven adoption of the Medicaid expansion was expected to increase health inequities among PLWH after ACA implementation11 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Top—Rates of HIV diagnoses per 100,000 people among adults and adolescents in the United States in 2015, by state. Adapted from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.54 Bottom—Medicaid expansion by state.

Scholars and policy makers expected that the combined effect of the expansion of Medicaid and the reformation of the private health insurance market would result in fewer PLWH having to wait until they were disabled to qualify for medical coverage, including ART.2 In addition to improving health outcomes, early access to ART prevents new infections.33 Earlier care is also associated with longer life expectancy and increased job productivity.33 Table 2 summarizes the main predictions by scholars and practitioners.

Table 2.

Summary of Main Pre-Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) Prediction and Post-ACA Impact Regrading the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP)

| Article | Type of article or analysis and primary subject or variables | Main Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Pre-ACA Implementation Articles Predicting ACA Impact on RWHAP | ||

| Martin, 201235 | Nonempirical ACA impact on HIV clinical care |

|

| Abara, 20142 | Nonempirical ACA and low income people living with HIV (PLWH) |

|

| Cahill, 201511 | Nonempirical RWHAP and ACA |

|

| Kates, 201310 | Nonempirical ACA, PLWH, and RWHAP |

|

| Empirical Peer-Reviewed Articles Published Pre-ACA Full Implementation | ||

| Hazelton, 201441 | Qualitative analysis In-depth interviews with policymakers and clinicians concerning challenges and strategies to address changes accompanying health care expansion |

|

| Leibowitz, 201342 | Cross-sectional analysis of early evidence from California on transition to a reformed health insurance system for PLWH |

|

| Martin, 201317 | Qualitative analysis In-depth interviews of ADAP service providers regarding changes anticipated with the ACA |

|

| Sood, 201443 | Mixed methods Interviews with RWHAP practitioners to identify crucial components of RWHAP Descriptive statistics regarding practitioner perceptions of quality and importance of RHWAP, value of components of RWHAP, and concerns |

|

| Reports Published Post-ACA Full Implementation | ||

| Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), 201755 | RWHAP annual client-level data |

|

| Kaiser Family Foundation, 201756 | Analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data of national estimates of changes in insurance coverage among PLWH since the ACA implementation |

|

| National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD)37 | Compilation “of ideas and mechanisms currently employed by states” – no specific methods listed |

|

| Empirical Peer-Reviewed Articles Published Post-ACA Full Implementation | ||

| Berry, 201647 | Quantitative analysis of Medicaid expansion and type of insurance coverage for practitioner visits before and after implementation of the ACA |

|

| Diepstra, 201729 | Quantitative analysis of data on receipt of RWHAP core medical, support, and insurance or direct medication assistance through ADAP in Virginia |

|

| Kay, 201849 | Quantitative analysis of RWHAP supplementary services provision in Alabama |

|

Expectations Regarding the ACA Impact on RWHAP Services

The ACA was predicted to decrease the number of underinsured people by 70% by eliminating annual limits and lifetime limits on health care coverage,13 which in turn was expected to reduce the number of uninsured and underinsured PLWH relying on RWHAP.2 Furthermore, increased access to ART was expected to result in cost savings to RWHAP ADAPs. For those PLWH who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, from 2012 through 2020 the ACA is incrementally reducing the gap between the ceiling at which Medicare stopped paying for 75% of drug costs and “catastrophic coverage.” These coverage gaps require certain PLWH to pay the full costs of prescription drugs until the onset of catastrophic coverage. Referred to as a “doughnut hole” in Medicare prescription drug plans, these gaps are expensive for PLWH,34 who can reach the ceiling quickly because of the high costs of ART. Specifically, ART alone of-ten costs more than $2500 per month, and the ceiling in 2010 for most Medicare Part D plans was $3610.35

Before this provision of the ACA went into effect in 2012, ADAPs would take over paying the costs of medication once patients hit their ceiling, and because patients were not paying out-of-pocket, they would not reach the catastrophic spending level at which Medicare would again cover the costs for medication.13 Under the ACA, however, ADAP expenditures count toward out-of-pocket medication costs, thus individuals receiving ADAP benefits may reach the catastrophic spending level and Medicare funds may resume paying for medication.17 In addition, payments by ADAPs can now count toward true out-of-pocket costs. These 2 changes will shift some of the costs for covering medication from the RWHAP to Medicare.35

Moreover, following ACA implementation, many states moved their ADAPs from a program that purchased medications to a program that purchased health insurance coverage.36 The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation concluded its report on ADAP by contrasting the recent past of challenges that faced ADAP that led to the creation of waiting list, to the current state in which “emergency funding, increased rebates from manufacturers, and the implementation of the ACA have relieved much of this pressure.” However, the impact of this “pressure relief” on PLWH was not examined. Moreover, this cost saving change was expected to result in reduced average cost per PLWH. In July 2017, National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) related to these changes, stating that the increased financial resources can be used to provide services that increase virologic suppression by addressing structural and systemic barriers and staffing quality management programs. NASTAD has compiled a list of “best practices,” ideas and mechanisms used by states “to expand the range, quality, and effectiveness of services being offered through RWHAP Part B programs and/or ADAPs.”37 However, it is unknown to what degree these strategies are implemented by different states, and researchers did not examine how states are using the new funding sources and their impact on care and on patient-centered health outcomes.

The implementation of Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs) is another aspect of the ACA that was expected to improve health outcomes for PLWH. PCMHs increase retention in care and medication adherence, 2 factors that are crucial to improving health outcomes for PLWH.2 The National HIV/AIDS Strategy and the ACA positioned the PCMH as important strategy in improving quality of care and cost containment, and scholars therefore expected the ACA to increase use of PCMH.38 However, only 1 study examined PCMH for PLWH following ACA. The pilot study utilized interviews with key informants who shared positive experiences, and the authors called for studies employing stronger evidence.39

Limitations of the ACA for PLWH

The ACA may also have limitations. First, it categorically excludes legal immigrants from Medicaid eligibility for a 5-year waiting period, and it excludes undocumented immigrants entirely.2 Second, scholars expressed a concern that the increase in health care benefits may result in an overwhelming increase in demand on the health care workforce, particularly safety net providers.40 In addition, although access to insurance will increase for individuals in states that have expanded Medicaid, HIV disparities will grow due to the continued lack of insurance among PLWH in non-expansion states.11 Finally, as much of the funding for RWHAP relies on uncertain funding levels, scholars and advocates called for acknowledging the importance of the unique services the program provides, such as wrap-around services and medical case-management. RWHAP health care and social services practitioners surveyed and interviewed prior to ACA implementation highlighted the importance and effectiveness of the wraparound services provided by RWHAP and expressed concern about lower reimbursement rates under the low-income health plans and Medicaid expansion, which could affect the solvency and availability of HIV practitioners.41 A related concern they shared was the quality of care PLWH might receive from primary care providers without HIV expertise.41

Experiences from Previous State-Based Health Policy Reforms

In addition to predictions regarding the impact of ACA on RHWAP and its clients, indirect evidence about the effects of systemic changes in insurance provision is available from states that attempted near universal coverage prior to implementation of the ACA. Nearly a decade before the ACA began, Massachusetts began moving toward near universal health care coverage, which both improved outcomes (including rates of retention in care and viral load suppression) and access to insurance for PLWH.10 Even with near universal coverage, however, RWHAP funds remained an essential source of funding and were increasingly used to pay for insurance premiums and copayments in order to ensure retention in care. Similarly, in California, although 53% of individuals who were receiving services through a RWHAP transitioned to a low-income health program from January 2011 to June 2012, the number of individuals receiving care through the RWHAP increased slightly.42 Sixteen out of 18 agencies that provided services under the RWHAP, including case management, continued to do so to clients who transitioned into the low-income health programs.42 In addition, substance abuse treatment was not available through the low-income health plans, and thus PLWH continued to rely on RWHAP practitioners for those essential services. Before the 2014 ACA implementation, RWHAP practitioners strongly supported the need for the program in the post-ACA environment.43 Services for undocumented immigrants with HIV infection, PLWH who reside in states that did not expand Medicaid, and the need for wraparound services, especially case management, were noted as major reasons for the need for RWHAP post-ACA.

In sum, these early observations clearly demonstrated the important role that the RWHAP was expected to play in the new healthcare landscape. However, concerns were raised about its funding level and political support, especially as Congressional decision is needed for appropriation of RWHAP funding.44 In light of the concerns and hopes that preceded the ACA implementation as described here, it is important to explore the evidence on the impact of the ACA on the program and its clients, as well as on the role of RWHAP following the 2014 full roll out of the reform. The following section describes this evidence.

Empirical Evidence: Early Observations of the Effect of the ACA on RWHAP and its Clients

Early reports on the impact of the ACA on the general population revealed that it has largely increased the number of insured Americans by approximately 16.4 million, consisting of those who were previously uninsured and gained coverage due to the longer eligibility for youth to remain on their parents' plans, the Medicaid expansion, and marketplace options.45 RWHAP-related information after the ACA is available through the grey literature, ie, government and non-for profit organizations (Table 1). Some data are now available on the effects of the ACA on HIV care.46 In a study that compared compensated and RWHAP or uncompensated care in Medicaid expansion versus non-expansion state sites,47 half of PLWH relying on RWHAP or uncompensated care shifted to Medicaid in the first months of 2014 in expansion state sites. In contrast, reliance on the program and uncompensated care remained constant in non-expansion state sites. The researchers concluded that “[i]n the first half of 2014, the ACA did not eliminate the need for RWHAP safety net provider visit.” In an editorial commentary, the authors noted that the study included data for the first 6 months of 2014, at a time when many PLWH were still struggling to enroll in the ACA.48

Table 1.

Selected Information Sources Related to Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP)

| Source | Content of Information | Link |

|---|---|---|

| AIDSVu | Interactive online mapping tools with national and local HIV care and prevention information and resources | https://aidsvu.org/ |

| Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | Policy, planning, and strategic communication | https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/index.html |

| Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) | RWHAP information | https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/ |

| Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) | RWHAP information Links to reports on HIV-related policy, legislations, reports, and projections | |

| National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) |

|

Emerging evidence suggests a positive impact of the ACA on clients' health outcomes. Analysis of RWHAP supplementary service provision after the ACA revealed that almost half of the clients in the Southeast sample received RWHAP supplementary services. Receipt of these services was associated with increased odds of viral suppression and of 2 measures of retention in care.49 Other researchers focus on specific aspects of HIV care and health outcomes that are relevant to RWHAP. Hellinger27 reported that the availability of insurance in 4 states dramatically reduced hospitalizations among PLWH. The analysis of hospital discharge data from 2012 through the June 2014 in 4 states that expanded Medicaid and 2 that did not revealed that hospitalizations of uninsured PLWH fell from 13.7% to 5.5% in the 4 Medicaid expansion states.27 In contrast, this percentage rose from 14.5% to 15.7% in the 2 nonexpansion states. Moreover, uninsured PLWH were 40% more likely to die in the hospital than those with insurance coverage.27

In a study conducted in Virginia,29 authors examined receipt of RWHAP core medical, support, and insurance or direct medication assistance through ADAP. Of PLWH who engaged in any HIV care in 2014, 58% received any RWHAP service and 17% received all 3 types of services (comprehensive assistance). Receiving more classes of RWHA services was associated with improved HIV outcomes as evidenced by retention in care and viral suppression. The authors concluded that the program's services were still required for optimal health outcomes of many PLWH.29

Even after implementation of the ACA, however, out-of-pocket costs for ART remained high for PLWH insured by marketplace plans.50 The monthly out-of-pocket costs for HIV medications offered by the top 12 insurance companies extending Qualified Health Plans on Michigan's Health Insurance Marketplace Exchange ranged from $12 to $667 per medication.50 Three Marketplace insurance plans placed all 31 assessed medications on the highest cost-sharing tier and charged 50% copayments for the medication. The researcher concluded that the high cost of coinsurance may discourage low-income PLWH from taking advantage of the ACA and may act as a barrier to medicine adherence.50

Government reports provide some promising results as well. For instance, one fifth (20.6%) of RWHAP clients had no health care coverage in 2016, a decrease from 27.6% in 2012. These national reports, although demonstrating encouraging results, should be interpreted cautiously given limitations of data and measurements.51 Most notably, in the absence of national data, reports based on RWHAP client data are based only on clients who were enrolled in care. For others, it is unknown whether they dropped out of care or are seeing non-RWHAP providers.

Moreover, geographical differences remain largely underexplored. For example, whereas few changes were observed in retention in care nationally, New Mexico saw a drop from 81% (n=1279) in 2015 to 60% (n=766) of RWHAP clients retained in care.51 Such local changes highlight the importance of understanding and addressing national trends, as well as geographic-based processes. See Table 2 for a summary of major findings regarding the impact of ACA on RWHAP and its clients.

Continuing Need for RWHAP After the ACA

Despite the ACA's expansive provisions, including those aimed at insuring millions more Americans, PLWH may still not be able to afford all of the costs of medication and treatment, or even to become or remain uninsured. Approximately 43% of PLWH live in states that did not expand Medicaid to all individuals making less than 138% of the FPL,10 thus many remain uninsured. Non-expansion states are typically in the South. These states also account for a substantial proportion of all HIV cases and for a growing proportion of new infections. HIV care infrastructure and access in Southern states were already the weakest prior to ACA implementation.10 Consequently, these states experience the biggest burden, but have the fewest resources given the lack of Medicaid expansion. Furthermore, many immigrants remain ineligible for Medicaid coverage.17 For these uninsured populations, the RWHAP may be the only source of HIV care, thus the need remains for the RWHAP safety-net function.

In addition, some individuals have fluctuating income near the FPL, which may result in a phenomenon called “churning.” Churning refers to involuntary changes in individuals' insurance.2 Churning occurs when an individual is sometimes eligible for Medicaid (ie, making less than 138% of the FPL) and at other times ineligible (making more than 138% of the FPL) and thus required to purchase insurance through a state exchange.35 These changes in insurance coverage may result in interruption of care, but the RWHAP could ensure continuity of coverage by covering the costs of medical visits and medications during transition phases.35 Furthermore, it may be prudent to use the RWHAP funds to help pay premiums for those PLWH who are unable to do so entirely on their own.10

The RWHAP is also essential for covering medication copayments and services not covered by Medicaid or private insurance plans. Given the high cost of HIV medication, without contributions toward copayments from the RWHAP, PLWH may still be unable to afford medications.9,52 Furthermore, the health outcome benefits of wraparound services, including housing assistance and transportation to health care, have been well documented. The ACA does not cover wrap-around services. The RWHAP can cover the deductibles and copayments for PLWH on marketplace private insurance plans, which may otherwise be unaffordable.17 The RWHAP can also assist with case management and assistance in obtaining other benefits.27 Considering administrative services, RWHAP care coordinators are likely to play a continuing and major role in enrolling low-income PLWH in insurance programs or Medicaid.17

The ACA provides preventive free care with no copay, including free HIV testing. This provision was expected to uncover over 2,500 new HIV cases by 2017.2 Combined with the effect of new recommendations to begin ART as soon as possible after diagnosis, there will be additional demand for ART and wrap-around services. This will place additional demand on the RWHAP, which is the only source of assistance for wrap-around services and which will be particularly important for providing ART to low income PLWH in states that have not expanded Medicaid.17

In summary, although the ACA is likely to substantially increase health care coverage and improve health outcomes for PLWH, numerous provisions of the RWHAP remain crucial for this population. As the number of PLWH in the Unites States is projected to increase by at least 24% over the next decade, increased funding for the RWHAP may be necessary to meet the demand for services.11 The adaptability of the RWHAP, which has been pivotal in its success in ensuring care for PLWH, is expected again to be vital in meeting the changing care needs of PLWH under the ACA. “The welcome expansion of insurance under the ACA is complementary to, not a substitute for, the care completion services historically delivered by the RWHAP.”42 The RWHAP will play an indispensable role in allowing PLWH “to take full advantage of the increased access made newly available by the ACA,” and thereby increase their lifespans, increase their quality of life, increase their productivity, and reduce transmission and incidence of HIV.42

Conclusions

Research and Practice Implications

The importance of RWHAP to health outcomes of PLWH was well documented before the ACA implementation.1 In the time since the 2014 full ACA implementation, studies examined the degree to which care was compensated or not,47 and more recently the outcomes of RWHAP clients post-ACA.49 Most studies that examined the impact of the ACA on PLWH did not focus on RWHAP specifically or collect data before the 2014 full ACA implementation.53 Therefore, the claims regarding impact of the ACA on health outcomes of RWHAP clients or former clients need further substantiation. Research should explore, using national data, the impact of ACA on RWHAP and non-RWHAP clients, with a focus on those who experienced changes to their medical insurance coverage following the establishment of the ACA. Moreover, research should focus on specific groups of PLWH that are at increased risk of being underserved, such as undocumented immigrants, transgender women, homeless individuals, and those with mental health issues. In addition, research should explore the impact of the ACA of RWHAP staff, examining implementation strategies,41 professional strategies and personal adjusting to ACA, as well as possible burnout that may lead to a reduction in HIV work force.

Following lingering gaps in HIV care, the 3 central dimensions to examine in future research on RWHAP post-ACA relate to linkage to care, inequity in access to care, and comorbidities. Studies are needed to explore the role of RWHAP post-ACA in linking PLWH to care at diagnosis, retention in care, and adherence to treatment. These future studies should include health outcomes, including virologic suppression among PLWH who experienced changes following ACA, mortality and morbidity, and prevention of further transmission.

Moreover, future research should focus on specific populations and known inequities in HIV care and risk of HIV infection. As previously discussed, it is important to explore the effect of post-ACA changes to care on vulnerable, at-risk populations including ethnic and racial minorities, young adults, sexual minorities, and low-income PLWH. Similarly, future studies should explore the impact of ACA on current or former RWHAP clients with comorbidities. For example, what is the current level of access to mental health services among PLWH in general, and particularly among the third of PLWH with serious mental health or substance use disorders? What are the utilization, quality of care, and health outcomes among PLWH with cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, or other age-associated comorbidities?

Future studies should also focus on PLWH's ability to navigate the current system, as well as the ability of RWHAP staff, such as case managers, to facilitate this navigation. Studies conducted before ACA implementation documented that PLWH who were medically insured had higher survival rates than those who were uninsured.19 Therefore, future research should explore whether the increased coverage under the ACA led to an increase in longevity among the newly insured, and whether this led to decrease in inequities in health outcomes among specific demographic groups such as younger PLWH.23 Similarly, whereas in this review we considered the implications of the ACA to PLWH who receive RWHAP care, examination of the effects on new infections and HIV prevention efforts should also be carried out.

Policy Implications

In view of the evidence regarding the importance of the RWHAP as a safety net for PLWH, despite ACA implementation, which include specific association with viral suppression, retention in care, and prevention of transmission, policy makers should maintain support for RWHAP programs. Whereas some also expect cost savings, it is important to use this opportunity for providing additional needed services for vulnerable populations. While RWHAP is maintained, policy makers should also commission a comprehensive cost analysis of the combined benefits of ACA and RWHAP to examine the long-term economic implications. If there are cost savings, it will be important for practioners to leverage savings to enhance health services and outcomes with policy makers ensuring such gains are realized.

Community advocates, activists, and practitioners need to remain active in arguing for the merits of RWHAP-provided wrap around services for vulnerable subgroups. It is important to engage in advocacy and education to prevent the elimination of these services in short-sighted efforts to reduce costs. Cost-saving calculations often fail to take public health benefits into consideration, incorrectly viewing RWHAP as a form of health insurance rather than the public health program that it is. In the era of “treatment as prevention” and “U=U” (“undetectable = untransmittable”), where national HIV incidence is finally decreasing, it is crucial that we present evidence of the individual health improvements and the reduction in HIV transmission as ongoing benefits of RWHAP in the post-ACA era.

Footnotes

Financial affiliations in the past 12 months: Dr Ginossar has no relevant financial affiliations to disclose. Dr Oetzel has no relevant financial affiliations to disclose. Ms Van Meter has no relevant financial affiliations to disclose. Mr Gans has no relevant financial affiliations to disclose. Dr Gallant is employed by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Contributor Information

Tamar Ginossar, Associate Professor in the Department of Communication and Journalism at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico..

John Oetzel, Professor of health communication in the Waikato Management School in Hamilton, New Zealand..

Lindsay Van Meter, Managing Assistant City Attorney in Albuquerque, New Mexico..

Andrew A. Gans, HIV, STD and Hepatitis Section Manager in the New Mexico Department of Health in Santa Fe, New Mexico..

Joel E. Gallant, Former Medical Director of Specialty Services at Southwest Care Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and currently an employee of Gilead Sciences, Inc, in Foster City, California..

References

- 1. Doshi RK, Milberg J, Isenberg D, et al. High rates of retention and viral suppression in the US HIV safety net system: HIV care continuum in the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(1):117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abara W, Heiman HJ. The Affordable Care Act and low-income people living with HIV: looking forward in 2014 and beyond. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(6): 476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bradley H, Viall AH, Wortley PM, Dempsey A, Hauck H, Skarbinski J. Ryan White HIV/AIDS program assistance and HIV treatment outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2016; 62(1):90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weiser J, Beer L, Frazier EL, et al. Service delivery and patient outcomes in Ryan White HIV/AIDS program-funded and -nonfunded health care facilities in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(10):1650–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lopez JD, Shacham E, Brown T. The impact of the Ryan White HIV/AIDS medical case management program on HIV clinical outcomes: a longitudinal study. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3091–3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hess KL, Hall HI. HIV viral suppression, 37 states and the District of Columbia, 2014. J Community Health. 2018;43(2):338–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beer L, Valverde EE, Raiford JL, Weiser J, White BL, Skarbinski J. Clinician perspectives on delaying initiation of antiretroviral therapy for clinically eligible HIV-infected patients. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(3):245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McManus KA, Engelhard CL, Dillingham R. Current challenges to the United states' AIDS drug assistance program and possible implications of the affordable care act. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:350169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crowley J. S. and Kates J.. Updating the Ryan White HIV/AIDS program for a new era: key issue & questions for the future. https://www.mdjustice.org/files/Ryan%20White%20kff.pdf. Accessed on May 6, 2019.

- 10. Kates J. Implications of the Affordable Care Act for people with HIV infection and the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: what does the future hold? Top Antivir Med. 2013;21(4): 138–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cahill SR, Mayer KH, Boswell SL. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program in the age of health care reform. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1078–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hernandez JP, Potocky M. Ryan White CARE Act Part D: matches and gaps in political commitment and local implement ation. Soc Work Public Health. 2014;29(3): 267–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin EG, Strach P, Schackman BR. The state(s) of health: federalism and the implementation of health reform in the context of HIV care. Public Admin Rev. 2013; 73(s11):s94–s103. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snider JT, Juday T, Romley JA, et al. Nearly 60,000 uninsured and low-income people with HIV/AIDS live in states that are not expanding Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(3):386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipira L, Williams EC, Hutcheson R, Katz AB. Evaluating the impact of the affordable care act on HIV care, outcomes, prevention, and disparities: a critical research agenda. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(4):1254–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Colasanti J, Kelly J, Pennisi E, et al. Continuous retention and viral suppression provide further insights into the HIV care continuum compared to the cross-sectional HIV care cascade. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(5):648–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin EG, Meehan T, Schackman BR. AIDS Drug Assistance Programs: managers confront uncertainty and need to adapt as the Affordable Care Act kicks in. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beer L, Mattson CL, Bradley H, Skarbinski J. Understanding cross-sectional racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in antiretroviral Use and Viral Suppression Among HIV Patients in the United States. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(13):e3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738): 367–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richardson KK, Bokhour B, McInnes DK, et al. Racial disparities in HIV care extend to common comorbidities: implications for implementation of interventions to reduce disparities in HIV care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2016;108(4):201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1787–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV - United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1113–1117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huff A, Chumbler N, Cherry CO, Hill M, Veguilla V. An in-depth mixed-methods approach to Ryan White HIV/AIDS care program comprehensive needs assessment from the Northeast Georgia Public Health District: the significance of patient privacy, psychological health, and social stigma to care. Eval Program Plann. 2015; 49:137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kff.org. Accessed on May 6, 2019.

- 26. Hirschhorn LR, Landers S, McInnes DK, et al. Reported care quality in federal Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program supported networks of HIV/AIDS care. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hellinger FJ. In four ACA expansion States, the percentage of uninsured hospitalizations for people with HIV declined, 2012–14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(12): 2061–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Doshi RK, Milberg J, Jumento T, Matthews T, Dempsey A, Cheever LW. For many served by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, disparities in viral suppression decreased, 2010–14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Diepstra KL, Rhodes AG, Bono RS, Patel S, Yerkes LE, Kimmel AD. Comprehensive Ryan White assistance and human immunodeficiency virus clinical outcomes: retention in care and viral suppression in a medicaid nonexpansion state. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(4):619–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Durenberger D. Health Care Reform and the American Congress. Milbank Q. 2015; 93(4):663–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lanier Y, Sutton MY. Reframing the context of preventive health care services and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections for young men: new opportunities to reduce racial/ethnic sexual health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Price CC, Eibner C. For states that opt out of Medicaid expansion: 3.6 million fewer insured and $8.4 billion less in federal payments. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6): 1030–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldman DP, Juday T, Seekins D, Linthicum MT, Romley JA. Early HIV treatment in the United States prevented nearly 13,500 infections per year during 1996–2009. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(3): 362–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flaer PJ, Benjamin PL, Malow RM, Morisky DE, Parkash J. The growing cohort of seniors with HIV/AIDS: changing the scope of Medicare Part D. AIDS Care. 2010;22(7):903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martin EG, Schackman BR. What does U.S. health reform mean for HIV clinical care? JAIDS. 2012;60(1):72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAPs). https://www.kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/aids-drug-assistance-programs/. Accessed on May 6, 2019.

- 37. NASTAD. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program part B and ADAP uses of rebate funds. http://www.nastad.org/sites/default/files/resources/docs/nastad-rwhap-part-b-and-adap-uses-of-rebate-funds-as-of-july-2017.pdf. Accessed on May 6, 2019.

- 38. Pappas G, Yujiang J, Seiler N, et al. Perspectives on the role of patient-centered medical homes in HIV Care. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e49–e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beane SN, Culyba RJ, DeMayo M, Armstrong W. Exploring the medical home in Ryan White HIV care settings: a pilot study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014; 25(3):191–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abraham JM. How might the Affordable Care Act's coverage expansion provisions influence demand for medical care? Milbank Q. 2014;92(1):63–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hazelton PT, Steward WT, Collins SP, Gaffney S, Morin SF, Arnold EA. California's “Bridge to Reform”: identifying challenges and defining strategies for providers and policymakers implementing the Affordable Care Act in low-income HIV/AIDS care and treatment settings. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leibowitz AA, Lester R, Curtis PG, et al. Early evidence from California on transitions to a reformed health insurance system for persons living with HIV/AIDS. JAIDS. 2013;64 Suppl 1:S62–S67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sood N, Juday T, Vanderpuye-Org, et al. HIV care providers emphasize the importance of the Ryan White Program for access to and quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(3):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hatcher W, Pund B, Khatiashvili G. From compassionate conservatism to Obamacare: funding for the Ryan White Program during the Obama administration. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):1955–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The Affordable Care Act's Impacts on Access to Insurance and Health Care for Low-Income Populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:489–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McManus KA, McGonigle KM, Engelhard CL, Dillingham R. PPACA and low-income people living with HIV: 2014 qualified health plan enrollment in a medicaid nonexpansion state. South Med J. 2016;109(6):371–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Berry SA, Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, et al. Healthcare coverage for HIV provider visits before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Eaton EF, Mugavero MJ. Editorial commentary: Affordable Care Act, Medicaid expansion … or not: Ryan White Care Act remains essential for access and equity. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):404–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: supplementary service provision post-Affordable Care Act. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(7): 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zamani-Hank Y. The Affordable Care Act and the burden of high cost sharing and utilization management restrictions on access to HIV medications for people living with HIV/AIDS. Popul Health Manag. 2016;19(4):272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Health Resources and Services Administration. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Annual Client-Level Data Report. https://hab.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hab/data/datareports/RWHAP-annual-client-level-data-report-2016.pdf. Accessed on August 1, 2018.

- 52. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. The Affordable Care Act, and the Supreme Court and HIV: what are the implications. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/report/the-affordable-care-act-the-supreme-court-and-hiv-what-are-the-implications/. Accessed on May 6, 2019.

- 53. Ginossar T, Van ML, Ali Shah SF, Bentley JM, Weiss D, Oetzel JG. Early Impact of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on People Living With HIV: A Systematic Review. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(3):259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the united states and dependent areas, 2015. HIV Surveillance Report. 2016;27:1–114. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Health Resources and Services Administration. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Annual Client-Level Data Report. https://hab.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hab/data/datareports/RWHAP-annual-client-level-data-report-2016.pdf. Accessed on August 1, 2018.

- 56. Kates J., Lindsey D., and Kaiser Family Foundation. Insurance Coverage Changes for People with HIV Under the ACA. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/insurance-coverage-changes-for-people-with-hiv-under-the-aca/. Accessed on May 20, 2019.