Abstract

The relationship of cognitive developmental trajectories during the dynamic first years with later life development outcomes remains unclear in low- and middle-income countries. 1388 Children born to women who participated in a randomized trial of antenatal micronutrient supplementation in rural China were prospectively followed. Cognitive development was assessed six times between 3 and 30 months of age using Bayley Scales of Infant Development, and then in mid-childhood (7–9 years) and early adolescence (10–12 years) using Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. We identified four distinct infant cognitive development trajectory subgroups using group-based trajectory modeling: (i) consistently above average, (ii) consistently average, (iii) started below average and then improved, and (iv) started below average and then declined. LBW infants (<2500 g) were 10.60 times (95% CI 3.57, 31.49) more likely to be in the trajectory group that started below average and then declined, while each grade increase in maternal education decreased the risk of being in this group by 73% (95% CI 54%, 84%). Infants who performed consistently above average had 8.02 (95% CI 1.46, 14.59) points higher IQ in adolescence versus the declining trajectory group. These findings suggest that interventions to improve early child development trajectories may produce long-term human capital benefits.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Paediatric research

Introduction

An estimated 250 million children under five years living in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) failed to reach their full developmental potential1. Adversities and risk factors during the first 1000 days of life lay the foundation for development and have long-term consequences across the lifecourse1–4. Studies have shown that suboptimal childhood cognitive development is associated with higher risk of coronary heart disease, reduced human capital, and increased risk of mortality and poor health outcomes later in life5–8.

A number of modifiable risk factors for suboptimal development have been identified including poverty-related factors, inadequate stimulation, environmental and nutritional factors9,10. Nevertheless, a limitation of studies that examined early life determinants of cognitive development typically only assess children at a single time-point, which does not capture the dynamic process of child development. In fact, only a few studies from high-income countries focused on preterm infants have assessed cognitive development trajectories in early childhood. One cohort study from UK and Ireland among 315 extremely preterm births found that impaired cognitive trajectory in infancy persisted into early adulthood and there was no evidence of catch-up11. In contrast, a study in the US reported catch-up language trajectory from 3 to 12 years among very preterm infants12. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship of early child development trajectories with later life development outcomes among the general population in LMICs.

In this study, we used data from a rural Chinese birth cohort, in which the cognitive development was assessed at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months during the first two years of life and then at 30 months, middle childhood (7–9 years) and in adolescence (10–12 years). The main aims of our analysis were to (1) identify distinct trajectories of cognitive development during the first two years of life, (2) examine predictors associated with these trajectories, and (3) assess whether these trajectories were associated with long-term cognitive outcomes in middle childhood and early adolescence.

Results

A total of 1388 children were included in group-based trajectory modelling (GBTM) analyses. Baseline characteristics of these participants are presented in Table 1. A total of 669 and 735 of these participants were followed at middle childhood (7–9 years) and early adolescence (10–12 years), respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1). The mean age at middle childhood and adolescence were 7.8 years (SD ± 0.6) and 11.3 (SD ± 0.6) years, respectively. Most background characteristics were similar between individuals who completed the middle childhood and early adolescence assessments and those who were lost to follow-up (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of infants included in group-based trajectory analysis in a Chinese birth cohort study (N = 1388)a.

| Factors | No. (%)/Mean (SD) | Factors | No. (%)/Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | 24.4(4.4) | Child characteristics | |

| Maternal education | Male | 845(60.9) | |

| <3 years | 61(4.4) | Birth weight (g) | 3185(410) |

| Primary | 341(24.6) | Weeks of gestation at birth | 39.9(1.6) |

| Secondary | 798(57.6) | Preterm (<37 weeks gestation) | 50(3.6) |

| High school+ | 185(13.4) | Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 50(3.7) |

| Maternal occupation | Small for gestational age(<10th percentile) | 165(12.3) | |

| Farmer | 1172(84.8) | Age at middle childhood/years | |

| Others | 210(15.2) | Mean (SD) | 7.8(0.6) |

| Paternal age (years) | 27.7(4.2) | Range | 7–9 |

| Paternal education | Age at adolescence/years | ||

| <3 years | 12(0.9) | Mean (SD) | 11.3(0.6) |

| Primary | 139(10.1) | Range | 10–12 |

| Secondary | 914(66.1) | MDI at 30 months of age | 86.7(18.7) |

| High school+ | 317(22.9) | WISC-IV at school age(7–9 years) | |

| Paternal occupation | FSIQ | 89.5(12.6) | |

| Farmer | 1054(76.1) | VCI | 87.4(15.5) |

| Others | 332(24.0) | WMI | 91.2(12.0) |

| Household wealth at enrollment | PRI | 93.6(13.3) | |

| Low | 324(23.3) | PSI | 95.3(12.9) |

| Medium | 562(40.5) | WISC-IV at adolescence(10–12 years) | |

| High | 502(36.2) | FSIQ | 98.1(12.5) |

| Parity at enrollment | VCI | 102.9(15.6) | |

| 0 | 943(67.9) | WMI | 94.5(11.0) |

| ≥1 | 445(32.1) | PRI | 96.0(12.5) |

| Maternal MUAC (cm) | PSI | 100.0(13.7) | |

| <21.5 | 219(15.9) | ||

| ≥21.5 | 1159(84.1) | ||

| Trial treatment | |||

| Folic acid | 496(35.7) | ||

| Iron/folic acid | 467(33.7) | ||

| Multiple micronutrients | 425(30.6) |

aData are missing for maternal age (n = 2), maternal education (n = 3), maternal occupation(n = 6), paternal age(n = 2), paternal education(n = 6), paternal occupation(n = 2), maternal MUAC(n = 10), birth weight(n = 21), preterm(n = 21), and SGA(n = 51).

Abbreviation: VCI, verbal comprehension index; FSIQ, full-scale intelligence quotient derived from WISC-IV, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition; MDI, mental development index; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; PRI, perceptual reasoning index; PSI, processing speed index; SD, standard deviation; SGA, small for gestational age; WMI, working memory index.

Identification of child development trajectories during the first two years of life

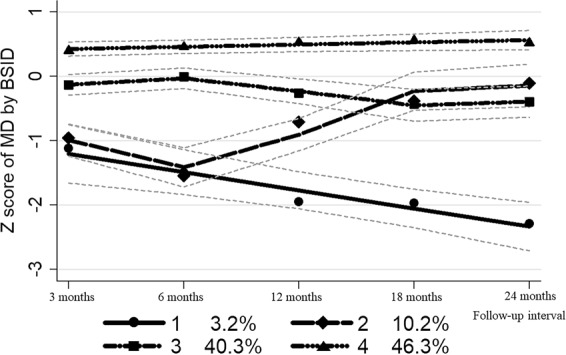

GBTM identified four trajectory subgroups: (1) “Subgroup 1: Start below average-then decrease” (3.2% of all participants), (2) “Subgroup 2: Start below average-then increase” (10.2%), (3) “Subgroup 3: Consistently average” (40.3%), (4) “Subgroup 4: Consistently above average” (46.3%). The fit indexes are presented in Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 1 graphically presents the final trajectories of cognitive test z scores during the first two years of life.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of cognitive development identified in infants from 3 to 24 months of age in a Chinese birth cohort study (n = 1388). Lines show for each trajectory the predicated means of z score and 95% confidence limits. Size (%) of each trajectory estimated by the model are presented below the x-axis, which was slightly different from the actual size used in subsequent analysis. The Subgroup 1, 2, 3 and 4 were labeled “Start below average-then decrease”, “Start below average-then increase”, “Consistently average”, and “Consistently above average”, respectively. Abbreviation: MD, mental development; BSID, Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development.

Predictors of child development trajectory group

We then compared the distribution of socioeconomic, pregnancy and birth outcome characteristics between the trajectory groups (Supplementary Table S3 and Table 2).We determined that children born to mothers with increasing educational level were less likely to be in the groups that started below average and then declined (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.16, 0.46), started below average and then improved (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.41, 0.85) and that performed consistently average (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.61, 0.94) than being in the group that performed consistently above average. Greater than 180 days of multiple micronutrients supplementation relative to folic acid or folic acid plus iron supplementation <180 days during pregnancy was associated with decreased risk of being in group of children who started below average and then improved (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.16, 0.90) and group of children who performed consistently average (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.44, 0.89) compared to the group of children performing consistently above average. Infants who were born low birth weight were 10.60 (95% CI 3.57, 31.49) times more likely to be in group of children who started below and then declined as compared to those who performed consistently above average.

Table 2.

Multivariate multinomial logistic regression analyses identifying predictors for being in the consistently above average group versus the other development trajectory groupsa.

| Factors | Subgroup 1: Start below average-then decrease | Subgroup 2: Start below average-then increase | Subgroup 3: Consistently average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | P values | RR (95% CI) | P values | RR (95% CI) | P values | |

| Maternal education per grade increaseb | 0.27(0.16, 0.46) | <0.001 | 0.59(0.41, 0.85) | 0.01 | 0.76(0.61, 0.94) | 0.01 |

| Maternal occupation-non-farmer | 0.16(0.02, 1.39) | 0.10 | 0.78(0.28, 2.12) | 0.62 | 0.74(0.46, 1.19) | 0.27 |

| Paternal education per grade increaseb | 1.33(0.69, 2.56) | 0.40 | 1.20(0.76, 1.89) | 0.43 | 0.84(0.66, 1.08) | 0.17 |

| Paternal occupation-non-farmer | 2.45(0.88, 6.86) | 0.09 | 0.77(0.34, 1.72) | 0.52 | 0.93(0.63, 1.37) | 0.70 |

| Household wealth per tertile increaseb | 1.17(0.69, 1.96) | 0.56 | 0.83(0.61, 1.14) | 0.24 | 0.95(0.80, 1.12) | 0.54 |

| Randomized prenatal regimen by supplementing duration | ||||||

| Folic acid or folic acid plus iron <180 days | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | |||

| Folic acid plus iron ≥180 days | 0.55(0.18, 1.66) | 0.29 | 1.20(0.66, 2.18) | 0.56 | 1.02(0.73, 1.41) | 0.94 |

| Multiple micronutrients <180 days | 0.71(0.25, 1.96) | 0.50 | 1.30(0.74, 2.31) | 0.36 | 0.94(0.68, 1.31) | 0.73 |

| Multiple micronutrients ≥180 days | 0.14(0.02, 1.07) | 0.06 | 0.37(0.16, 0.90) | 0.03 | 0.63(0.44, 0.89) | 0.01 |

| Child sex-Female | 0.49(0.21, 1.13) | 0.09 | 0.81(0.51, 1.29) | 0.37 | 0.81(0.63, 1.03) | 0.08 |

| Preterm (<37 gestation weeks) | 2.62(0.69, 9.99) | 0.16 | 2.15(0.87, 5.27) | 0.11 | 0.73(0.37, 1.44) | 0.37 |

| Small for gestational age (<10th percentile) | 4.94(2.16, 11.33) | <0.001 | 1.85(0.98, 3.50) | 0.06 | 1.63(1.13, 2.33) | 0.01 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g)c | 10.60(3.57, 31.49) | <0.001 | 2.50(0.87, 7.17) | 0.09 | 2.18(1.11, 4.29) | 0.02 |

a“Subgroup 4: Consistently above average” was the comparison group. Variables were included in the multinomial logistic regression analyses for their p values in the one-way analysis of variance or Chi-Square tests (Supplementary Table S3) less than 0.10.

bMaternal and paternal education were categorized as <3 years, Primary, Secondary and High school+, respectively. Household wealth was categorized as low, medium and high, respectively. All the variables were then treated as continuous variables in the multinomial logistic regression analyses.

cThe results for low birth weight were adjusted for the variables in the main model but excluding preterm and small for gestational age. Abbreviations: RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

We also examined these associations between Subgroup 1 and 2, and between Subgroup 3 and 4, respectively, and similar predictors were observed (Supplementary Table S4).

Relationships of development trajectory group with middle childhood and adolescent development outcomes

As shown in Table 3, the children who performed consistently above average during the first 2 years of life had persistently higher test scores in middle childhood and early adolescence. Infants that were consistently above average during the first two years had 8.02 (95% CI 1.46, 14.59) and 2.52 (95% CI 0.62, 4.41) points higher cognitive test scores in adolescence as compared to those who started below average and then declined or those who were consistently average, respectively.

Table 3.

Associations of identified cognitive development trajectories in the first two years of life with cognitive outcomes at 30 months of age, middle childhood and early adolescence.

| MDI at 30 months N = 1099 | FSIQ at middle childhood N = 669 | FSIQ at early adolescence N = 735 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup 1: Start below average-then decrease | N | 27 | 21 | 15 |

| Mean (SD) | 55.1 (27.2) | 76.8 (12.8) | 88.0 (15.0) | |

| Subgroup 2: Start below average-then increase | N | 83 | 36 | 43 |

| Mean (SD) | 81.5 (16.2) | 91.3 (12.9) | 97.0 (12.0) | |

| Subgroup 3: Consistently average | N | 454 | 256 | 294 |

| Mean (SD) | 80.0 (17.5) | 87.0 (11.4) | 96.0 (12.0) | |

| Subgroup 4: Consistently above average | N | 535 | 356 | 383 |

| Mean (SD) | 94.7 (15.0) | 91.9 (12.7) | 100.0 (12.0) | |

| Unadjusted mean differences (95% CI) | ||||

| Subgroup 1 vs Subgroup 4 as reference | −39.59 (−50.15, −29.04) | −15.11 (−20.32, −9.91) | −12.01 (−18.08, −5.94) | |

| Subgroup 2 vs Subgroup 4 as reference | −13.24 (−16.97, −9.51) | −0.62 (−4.55, 3.31) | −3.94 (−6.13, −1.75) | |

| Subgroup 3 vs Subgroup 4 as reference | −14.67 (−16.71, −12.64) | −4.97 (−6.77, −3.18) | −4.72 (−6.69, −2.75) | |

| Subgroup 2 vs Subgroup 3 as reference | 1.43 (−2.58, 5.44) | 4.36 (0.20, 8.51) | 0.78 (−2.30, 3.87) | |

| Subgroup 1 vs Subgroup 2 as reference | −26.35 (−37.47, −15.23) | −14.50 (−20.38, −8.61) | −8.07 (−14.56, −1.58) | |

| Adjusted mean differences (95% CI)a | ||||

| Subgroup 1 vs Subgroup 4 as reference | −35.52 (−45.38, −25.66) | −10.20 (−14.41, −5.99) | −8.02 (−14.59, −1.46) | |

| Subgroup 2 vs Subgroup 4 as reference | −10.93 (−14.80, −7.06) | 1.75 (−2.97, 6.48) | −2.58 (−4.88, −0.28) | |

| Subgroup 3 vs Subgroup 4 as reference | −12.76 (−14.86, −10.65) | −2.92 (−4.31, −1.52) | −2.52 (−4.41, −0.62) | |

| Subgroup 2 vs Subgroup 3 as reference | 2.34 (−1.52, 6.20) | 3.59 (−1.20, 8.38) | 0.61 (−2.67, 3.90) | |

| Subgroup 1 vs Subgroup 2 as reference | −25.16 (−35.13, −15.19) | −11.43 (−19.69, −3.18) | −6.98 (−13.47, −0.49) | |

aAdjusted for assessors and potential confounding factors including parental age, job and education at pregnancy enrollment, household wealth at pregnancy enrollment, maternal MUAC at pregnancy enrollment, maternal parity, randomized regimen, birth outcome (SGA), and sex in general estimating equation linear models.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FSIQ, full-scale intelligence quotient derived from WISC-IV, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition; SD, standard deviation; SGA, small for gestational age; MUAC, mid upper arm circumference.

In the adjusted analyses (Table 3), infants in the trajectory group that started below average and then improved and the group that were consistently average did not differ in cognitive outcomes in middle childhood or adolescence. However, the cognitive deficits of trajectory group that started below average and then declined relative to group that started below average and then improved persisted into adolescence with an adjusted mean FISQ differences of −6.98 (95% CI −13.47, −0.49).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using IPW to account for potential bias due to outcome censoring (loss to follow-up) and found there were no qualitative differences in our findings (Supplemental Table 5).

We also examined components of the FSIQ score and found similar associations within the VCI, WMI, PRI and PSI scores (Supplementary Tables S6 and Table S7).

Relationships of single-time point BSID-II scores at 12 and 24 months with middle childhood and adolescent development outcomes

We observed statistically significant, but weaker correlations magnitude of association, between BSID-II tertiles and development outcomes in middle childhood and early adolescence (Supplementary Table S8). Young children in the highest tertile of development scores at 12 and 24 months had 2.57 (95% CI: 0.31, 4.82) and 4.67 (95% CI: 2.01, 7.33) points higher scores in early adolescence as compared to those in the lowest tertile, respectively.

Discussion

We identified four distinct trajectories of infant cognitive development during the first two years of life in rural China: (1) children who started below average and then declined, (2) children who started below average and then improved, (3) children who were consistently average and (4) children who performed consistently above average. Higher maternal education and supplementing antenatal multiple micronutrients beyond 180 days were associated with reduced risk of being in suboptimal development trajectories; while, SGA and low birth weight birth increased the risk of being in the suboptimal groups. The developmental advantages of Subgroup 4 (consistently above average) over the other three trajectory groups persisted through middle childhood into early adolescence. In addition, the infants from subgroup 1 (started below average-then decreased) had the lowest test scores in middle childhood and early adolescence. These findings suggest that infant cognitive development trajectories are robust predictors of children long-term development outcomes.

We used a data-driven approach with five repeated measures in generally healthy children to identify development trajectories. One longitudinal study from Australia reported similar trajectories in aspect of language development between 8 and 48 months of age, which used the latent class analysis to address the categorized measures13. However, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the relationship of early life development with later life outcomes with these methods. This method advancement shows that trajectory modeling can identify subgroups of children who share similar important longitudinal changes in development during the first two years of life. We also found the trajectory approach provided greater contrast between infants as compared to single time-point assessment of BSID-II scores. These subgroups are also not distinct in studies that report development trajectory as age-specific averages11,12. As a result, trajectory modeling may better capture the dynamic process of child development and thus provide stronger associations with long-term outcomes.

We identified a pronounced catch-up pattern in Subgroup 2 (started below average-then increased) that would have been missed with a single time point assessment. In this study, the catch-up development appeared to start early in infancy and provides additional evidence that the first two years of life are critical for development. Of note, the catch-up pattern of cognitive development was similar to that of physical growth which also generally starts early in the first months of life14,15. In addition, our risk factor analyses suggest that a combination of prenatal nutrition, socioeconomic, and environmental factors may affect catch-up development. Although this finding requires replication in other studies, some studies reported that improvements in exclusive breastfeeding and longer partial breastfeeding were associated with better cognitive development outcomes later in life16,17. In addition, the identification of Subgroup 1 (started below and then declined) indicates that the trajectory modeling can be used to identify children with high risk of occurring delayed development. As a result, assessment of cognitive development trends may provide valuable information on children’s development and long-term outcomes.

Our study was also able to explore the early determinants that underlie the heterogeneity in these trajectories, which may help develop intervention strategies to reduce the risk of high-risk children being in suboptimal trajectories. We found that infants from high-income household wealth were more likely to be in the above average group, which is similar to a study conducted in the UK among subjects aged 2–1618. In addition, our finding that maternal education could independently act as a beneficial factor for child optimal development was in agreement with previous studies19–21. It has been proposed that higher maternal education level was associated with less maternal depression, better child nutrition status, child-rearing environment and ability to access and benefit from interventions. As described by the early nutrition programming22, antenatal micronutrient supplementation may improve child development, but the evidence has been inconsistent in the studies that assessed outcome at a single point23–25. In the present study, infants born by women who consumed multiple micronutrients for 180 days or beyond during pregnancy were less likely to be in the suboptimal trajectories. This finding extends the current knowledge on mechanisms underlying the antenatal micronutrient supplementation and long-term outcomes, which may have been linked during early life but would not be captured using the single-time assessment.

We also identified SGA or LBW as another predictor of development trajectories. These findings are consistent with prior studies26,27. Although some studies with short periods of follow-up reported that the influence of intrauterine growth restriction on cognitive development appeared to diminish overt time28, our finding and another study from UK and Ireland supported that impaired cognitive trajectories set in early life might persist into adolescence and early adulthood11. One recent systematic review from South Asia also reported that LBW children (<10 ys) relative to normal children had 5 points lower cognitive scores with a dose-response relationship29. Further, the differences among them became bigger along with the increasing age29, which was similar to the tendency observed in Subgroup 1 trajectory, i.e., linearly declining after birth. In the present study, this Subgroup 1 trajectory (started below average and then declined) was characterized by high risk of occurring preterm, LBW, and/or SGA (Supplementary Table S3). Hence, these findings highlight the programs that aim to reduce the risk of adverse birth outcomes before and during pregnancy.

There remains debate as to the long-term functional outcomes of cognitive tests in infancy in LMIC settings30. After using structural equation model to account for measurement error with 3 repeated measures among 130 infants, one longitudinal investigation from US reported that infant cognitive function moderately correlated with adolescent development outcomes with a correlation coefficient of 0.5731, which was higher than that observed in our study (0.18 for 12 months and 0.30 for 24 months, respectively; Supplementary Table S8). Taken together, these findings suggest that using single-time assessment of infant cognitive development has limitations to predict long-term outcomes and identify high-risk children for delayed development. In the present study, adolescents from Subgroup 4 (consistently above average) had the highest cognitive test scores, suggesting that the developmental advantages established in early life could persist through middle childhood into early adolescence. In addition, the infants from subgroup 1 (started below average-then decreased) had the lowest test scores in middle childhood and early adolescence. These findings suggest that infant cognitive development trajectories are strong predictors of children long-term development outcomes, and highlight the importance of providing appropriate interventions as early as possible, which could ameliorate restricted development and have important implications for human capital and well-being across the life course.

The results in the present study should be interpreted with a few limitations. First, the follow-up rate for children in middle childhood and adolescence in the present study was approximately 50% of the original cohort and therefore bias due to dependent censoring is possible. Nevertheless, we found minimal to no differences in background characteristics for children who had development assessed as compared to those who did not. Besides, a sensitivity analysis using IPW to account for outcome censoring also suggested the main study findings were robust and the risk of bias due to censoring was likely minimal. Second, the use of data-driven approach allowed us to identify distinct cognitive trajectories over age and was appropriate for several repeated measurements of the same individuals. However, the trajectory modelling approach shares inherent limitations including that extracting the optimal number of subgroups, which is a process guided by statistical fit indices and some degree of investigators’ decision, and that the size of each trajectory was produced by the model that may result in small sizes and consequently limited power to further analysis. Third, the cognitive development trajectories that we identified in our study population in rural China may not be directly applicable to other settings. Finally, the underlying biological mechanisms between these predictors and cognitive trajectories cannot be examined in the present study.

In summary, we identified groups of distinct trajectories of cognitive development during the first two years of life in rural China. Prospectively, we found that these trajectory groups robustly predicted development scores through middle childhood into adolescence. In addition, our risk factor analyses indicated that integrated of nutritional, environmental, and educational interventions during the first 1,000 days of life may affect early life cognitive development trajectories and produce long-term effects on development and human capital across the life course.

Methods

Participants

We used data from a prospective birth cohort of children born to women who participated in a randomized, double-blind trial of antenatal micronutrient supplementation in rural western China. Children were followed in early childhood (age 3 to 30 months), middle childhood (age 7–9 years) and early adolescence (age 10–12 years). Details and procedures of the trial and follow-up studies have been described elsewhere23–25,32.

Briefly, all pregnant women across villages from two counties were randomized to take a daily capsule of either folic acid, folic acid plus iron, or multiple micronutrients between August 2002 and February 2006. In the trial 4604 singleton births occurred, and 1400 births born in 2004–2006 were enrolled in long-term follow-up cohort. A total of 1388 was enrolled after excluding deaths (n = 3), birth defects (n = 7) and disabled parents (n = 2). Among them, 660 were followed at 7–9 years of age between October 2012 and September 2013, and 735 at 10–12 years of age between June 2016 and December 2016 for cognitive assessment.

Assessments of cognitive development

At the 3, 6, 12, 18, 24- and 30-month visit, mental development (MD) was assessed using a culturally appropriate, and locally validated Chinese version of Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II)33. MD raw scores were transformed into age-standardized scores based on the data for infants in US34.

In middle childhood and adolescence, we used the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) to assess cognitive development35. According to Chinese norms of WISC-IV with satisfied reliability and validity, age-standardized full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ), representing the general cognitive development, and aspects of verbal comprehension (VCI), perceptual reasoning (PRI), working memory (WMI), and processing speed index (PSI) were derived36.

Cognitive tests were standardly administered by public health graduates at subjects’ own home, local school or hospital meeting room that were free of distractions. Field staff administering these cognitive tests were unaware of the socioeconomic background, randomized treatment allocation, birth outcomes or other health status of participants.

Covariates

Information on socioeconomic status (parental age, occupation, education and household wealth), maternal nutrition status before pregnancy (mid-upper arm circumference), randomized regimen (folic acid, folic acid plus iron, and multiple micronutrients), maternal parity and birth outcomes (preterm birth, low birth weight [LBW], small for gestational age [SGA] birth and infant sex) was collected as part of the original trial using standard questionnaire, methods and/or procedures. These details are documented elsewhere23. A wealth index was established from an inventory of 16 household assets or facilities by principal component analysis, which was then classified into thirds as an indicator of low-, middle- and high-income households37. Preterm birth was defined as babies born alive before 37 weeks’ gestational age, and low birth weight was defined as a birth weight of less than 2500 g, as per the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines38,39. According to Intergrowth standards, SGA birth was defined as birth weight below the 10th percentile of weight-for-age and sex40.

Given our prior findings that multiple micronutrient supplementation could significantly improve cognitive development with the largest benefits observed with supplementation of at least 180 days25, we combined the randomized treatment regimens and duration into a categorical variable, i.e., folic acid or iron/folic acid lasting for <180 days (as reference), iron/folic acid lasting for ≥180 days, multiple micronutrients lasting for <180 days, and multiple micronutrients lasting for ≥180 days.

Statistical analysis

To increase comparability across ages, we transformed the age-standardized cognitive test scores into z-scores based on age-specific medians and SD within the sample. We then used a group‐based trajectory modelling, specifically the “traj” macro in Stata, to identify infant cognitive z-score developmental trajectories across 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of age41–43. GBTM can identify subgroups of individuals who share similar patterns of development42,43, and has been used to identify distinct trajectories of body composition and body mass index (BMI) that are associated with risks for obesity, asthma, morbidity and mortality later in life44–51. Models with two or more subgroups were compared to identify the optimal number of subgroups and shapes that best characterized the data, with maximum likelihood estimation accounting for missing z scores at any time point. The final model was selected based on general recommendations including: (i) tests for parameter estimates for linear, quadratic and cubic terms, (ii) Bayesian and Akaike information criterion value, (ii) average of the posterior probabilities of group membership for individuals assigned to each group, (iv) odds of correct classification based on the posterior probabilities of group membership, and (v) minimizing overlap in confidence intervals (CIs) while summarizing the distinctive features of the data as parsimonious as possible43.

Once the most appropriate trajectories were derived, the subgroup categories variable was used in all subsequent analyses. Baseline characteristics by the trajectory groups were compared using Chi-squared tests or analysis of variance, and multivariate multinomial logistic regression models. We then used generalized estimating equations with an independent correlation structure to assess the relationship of the trajectory groups with cognitive development outcomes at 30 months, middle childhood and early adolescence. To hand the missing data of cognitive outcome in middle childhood and early adolescence and examine its potential to influence the results, we applied the inverse probability weighting (IPW)52. We also conducted analyses using single-time point Bayley scores at 12 and 24 months to compare the magnitude of association for the GBTM approach.

Age-standardized FSIQ and VCI, WMI, PRI, and PSI scores were taken as the primary and secondary outcomes, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethical approval

The protocols of the original trial and all follow-up studies conformed to the ethical principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and were approved by UNICEF and the ethics committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center. Informed written content from pregnant women, and parents/caregivers, and oral consent from children were obtained.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The field work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 81872633, Lingxia Zeng) and National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Number 2017YFC0907200 and 2017YFC0907201, Hong Yan). This study was also supported by the China Scholarship Council (Grant Number 201806280188, Zhonghai Zhu). We also thank Nandita Perumal, PhD MPH, from the Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Z.Z., S.C., Y.C., H.Y., M.J.D. and L.Z.: planned and designed the study; Z.Z., Q.Q., S.L. and M.E.: conducted the study; Z.Z., S.C., C.R.S. and W.W.F.: analyzed data and interpreted results; Z.Z.: wrote the paper; L.Z.: had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: reviewed, revised and approved the final paper.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Competing interests

Dr. Suying Chang is a nutrition specialist of UNICEF China Office. The other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhonghai Zhu and Suying Chang.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54755-1.

References

- 1.Black MM, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S, Swanson JM. Developmental origins of health and disease: Brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:358–368. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman Peter D., Buklijas Tatjana, Hanson Mark A. The Epigenome and Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. 2016. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) Concept; pp. 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moody L, Chen H, Pan Y. Early-life nutritional programming of cognition—the fundamental role of epigenetic mechanisms in mediating the relation between early-life environment and learning and memory process. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:337–350. doi: 10.3945/an.116.014209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deary IJ, Whiteman MC, Starr JM, Whalley LJ, Fox HC. The Impact of childhood intelligence on later life: Following up the Scottish mental surveys of 1932 and 1947. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86:130–147. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGurn B, Deary IJ, Starr JM. Childhood cognitive ability and risk of late-onset Alzheimer and vascular dementia. Neurology. 2008;71:1051–1056. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319692.20283.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gale CR, Deary IJ, Schoon I, Batty GD. IQ in childhood and vegetarianism in adulthood: 1970 British cohort study. BMJ. 2007;334:245. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39030.675069.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvin CM, et al. Intelligence in youth and all-cause-mortality: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:626–644. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker SP, et al. Child development: Risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369:145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker SP, et al. Inequality in early childhood: Risk and protective factors for early child development. Lancet. 2011;378:1325–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linsell L, et al. Cognitive trajectories from infancy to early adulthood following birth before 26 weeks of gestation: A prospective, population-based cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:363–370. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luu TM, et al. Trajectories of receptive language development from 3 to 12 years of age for very preterm children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:333–341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ukoumunne OC, et al. Profiles of language development in pre-school children: A longitudinal latent class analysis of data from the Early Language in Victoria Study. Child: Care, Health Dev. 2012;38:341–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wit CC, Sas TC, Wit JM, Cutfield WS. Patterns of catch-up growth. J Pediatr. 2013;162:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzhardinge PM, Steven EM. The small-for-date infant I. Later growth patterns. Pediatrics. 1972;49:671–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Victora CG, et al. Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: A prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e199–e205. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rochat TJ, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and cognition, executive function, and behavioural disorders in primary school-aged children in rural South Africa: A cohort analysis. PloS Med. 2016;13:e1002044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Stumm S, Plomin R. Socioeconomic status and the growth of intelligence from infancy through adolescence. Intelligence. 2015;48:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong HS, Edwards P. Nature or nurture: A systematic review of the effect of socio-economic status on the developmental and cognitive outcomes of children born preterm. Matern Child Hlth J. 2013;17:1689–1700. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patra K, Greene MM, Patel AL, Meier P. Maternal education level predicts cognitive, language, and motor outcome in preterm infants in the second year of life. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:738–744. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1572532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harding JF. Increases in maternal education and low-income children’s cognitive and behavioral outcomes. Dev Psychol. 2015;51:583–599. doi: 10.1037/a0038920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koletzko B, et al. Long-term health impact of early nutrition: The power of programming. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70:161–169. doi: 10.1159/000477781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng L, et al. Impact of micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy on birth weight, duration of gestation, and perinatal mortality in rural western China: Double blind cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, et al. Prenatal micronutrient supplementation is not associated with intellectual development of young school-aged children. J Nutr. 2015;145:1844–1849. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.207795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Z, et al. Association of antenatal micronutrient supplementation with adolescent intellectual development in rural western China: 14-Year follow-up from a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:832–841. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farajdokht F, et al. Very low birth weight is associated with brain structure abnormalities and cognitive function impairments: A systematic review. Brain Cogn. 2017;118:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKean C, et al. Subgroups in language trajectories from 4 to 11 years: The nature and predictors of stable, improving and decreasing language trajectory groups. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2017;58:1081–1091. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linsell L, Malouf R, Morris J, Kurinczuk JJ, Marlow N. Prognostic factors for poor cognitive development in children born very preterm or with very low birth weight: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1162–1172. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Upadhyay RP, et al. Cognitive and motor outcomes in children born low birth weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies from South Asia. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:35. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mrozek-Budzyn D, Kieltyka MA, Majewska R. Validity and clinical utility of children development assessment using milestones reported by mothers. Przegl Epidemiol. 2014;68(71–75):153–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu H, McCoach DB, Gottfried AW, Gottfried AE. Stability of intelligence from infancy through adolescence: An autoregressive latent variable model. Intelligence. 2018;69:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2018.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q, et al. Effects of maternal multimicronutrient supplementation on the mental development of infants in rural western China: Follow-up evaluation of a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e685–e692. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang HT, Zhang SD. Standardization of bayley scales of infant development in Shanghai. Chin J Child Health. 1993;1:158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayley, N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Second ed.) (San Antonio,TX: Psychological Corp, 1993).

- 35.Wechsler D. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (Fourth ed.) (London: Pearson, 2004).

- 36.Chen H, Keith TZ, Weiss L, Zhu J, Li Y. Testing for multigroup invariance of second-order WISC-IV structure across China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Pers Indiv Differ. 2010;49:677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO Recommended definitions, terminology and format for statistical tables related to the perinatal period and use of a new certificate for cause of perinatal deaths. Modifications recommended by FIGO as amended October 14, 1976. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;56:247–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, eleventh revision (ICD-11), https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Villar J, et al. International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: The Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet. 2014;384:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones BL, Nagin DS. A note on a stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Sociol Method Res. 2013;42:608–613. doi: 10.1177/0049124113503141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagin DS, Jones BL, Passos VL, Tremblay RE. Group-based multi-trajectory modeling. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;27:2015–2023. doi: 10.1177/0962280216673085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ziyab AH, Karmaus W, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Zhang H, Arshad SH. Developmental trajectories of Body Mass Index from infancy to 18 years of age: Prenatal determinants and health consequences. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:934–941. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-203808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pryor LE, et al. Developmental trajectories of body mass index in early childhood and their risk factors: An 8-year longitudinal study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:906–912. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garden FL, Marks GB, Simpson JM, Webb KL. Body Mass Index (BMI) trajectories from birth to 11.5 years: Relation to Early Life Food Intake. Nutrients. 2012;4:1382–1398. doi: 10.3390/nu4101382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersen GS, et al. Body composition growth patterns in early infancy: A latent class trajectory analysis of the ethiopian iABC birth cohort. Obesity. 2018;26:1225–1233. doi: 10.1002/oby.22197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, et al. Body mass index trajectories during the first year of life and their determining factors. Am J Hum Biol. 2019;31:e23188. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.23188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu JX, et al. Body mass index trajectories during infancy and pediatric obesity at 6 years. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27:708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eny KM, et al. Breastfeeding duration, maternal body mass index, and birth weight are associated with differences in body mass index growth trajectories in early childhood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107:584–592. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqx081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aris IM, et al. Pre-, perinatal, and parental predictors of body mass index trajectory milestones. J Pediatr. 2018;201:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22:278–95. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).