Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a global disease with significant morbidity and mortality. Worldwide, an estimated 257 million people are chronically infected with HBV, defined as having a positive hepatitis B surface antigen, but millions more have prior HBV exposure indicated by positive hepatitis B core antibody. Reactivation of hepatitis B implies a sudden increase in viral replication in a patient with chronic HBV infection or prior HBV exposure. Hepatitis B reactivation (HBVr) can occur spontaneously, but it is more commonly triggered by immunosuppressive therapies for cancer, immunologic diseases, or transplantation. Elimination of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in HBV-HCV co-infected individuals treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has also been identified as an important cause of HBVr. Hepatitis B virus reactivation is an underappreciated but important complication of common medical therapies that can delay treatment or result in clinical episodes of hepatitis, hepatic failure, or death. In this review factors associated with HBVr, particularly medication-related risks, will be explored. We review data involving rituximab and ofatumumab, doxorubicin, corticosteroids, tumor necrosis factor antagonists, tyrosine kinases, bortezomib, hematologic stem cell transplantation, and DAAs for HCV treatment. In addition, we will discuss screening strategies, choice of antiviral prophylaxis, and the optimal duration of therapy for HBVr. With additional awareness, screening, and appropriate antiviral therapy, it is expected that most cases of HBVr can be prevented.

Keywords: chemotherapy, hepatitis, immunosuppression, reactivation hepatitis, rituximab, antivirals, immunotherapy

Introduction

Hepatitis B is an inflammatory disease of the liver caused by the human hepatitis B virus (HBV), an enveloped virus containing partially double stranded, circular DNA, and is a member of the Hepadnaviridae family of viruses.1 The virus is transmitted by blood or bodily fluids and can cause both acute and chronic infections of the liver. The risk of chronic infection is highest among children, with 80% to90% of infants infected during the first year of life and 30% to 50% of children less than 6 years of age developing chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection. By contrast, less than 5% of healthy adults with exposure to HBV will develop CHB infection.2 There are more than 257 million people chronically infected with HBV worldwide, and each year over 4 million acute HBV clinical cases are reported.2 Most of these infections occur in high prevalence areas including Asia, Africa, and the Amazon River basin. Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, and Central-South American have slightly lower prevalence, falling into the intermediate range. Low endemicity areas include Australia, North America, and the majority of Europe. In the United States, the availability of recombinant HBV vaccine and hepatitis B vaccination at birth, followed by completion of the vaccine series, has been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) since 1991 dramatically lowering the incidence of infection. The success of HBV vaccination in countries like the United States has prompted other countries to initiate HBV vaccination programs at birth.3 Recently, the ACIP recommendations were updated to recommend the initial vaccination within 24 hours of birth.4 There are several reasons for this new guidance, including: i) children are especially susceptible to developing CHB if acutely infected at birth or in childhood; ii) primary infection in young children is usually asymptomatic, so diagnosis can be delayed and other household members are at risk of exposure; and iii) vaccination is expected to offer long-term protection from HBV infection at any age. As a result, most new cases of HBV in the United States are primarily due to immigrants from areas of high endemicity.2, 5–7

Reactivation of HBV (HBVr) has been recognized as a complication of immunosuppressive treatments, particularly cytotoxic chemotherapy, in individuals with prior exposure to HBV, as well as those who are chronically infected with hepatitis B. Loss of HBV immune control is the key initial event in HBVr which leads to an increase in HBV DNA among patients previously exposed to HBV. Patients who experience HBVr can experience a hepatitis flare, demonstrated by elevations in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Clinical presentations of HBVr with hepatitis flare range from asymptomatic hepatitis to severe hepatitis accompanied by liver dysfunction, potentially resulting in death. Even if clinical manifestations of hepatitis are mild, the patient’s immunosuppressive treatment may be delayed until recovery from the hepatitis flare occurs, potentially resulting in worsened outcomes for the patient.

Prevention and treatment of HBVr is complex. A brief review of HBV serologies and their interpretation in the context of HBVr is provided in Table 1. The objective of this review is to describe the incidence, pathophysiology, risk factors and diagnosis of HBVr, as well as provide information concerning screening, monitoring, and management of HBVr.

Table 1:

Useful Hepatitis B Serology for Determining Reactivation

| Abbreviation | Lab Test | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | Hepatitis B surface antigen | Antigenic protein found on the surface of HBV. Detection of HBsAg indicates that the patient is infectious, and it can be present during either acute or chronic infection. |

| Anti-HBs | Hepatitis B surface antibody | Positive results indicate recovery and immunity from HBV infection or successful HBV vaccination. |

| Anti-HBc | Total hepatitis B core antibody | Detects both IgM (short-term immunity) and IgG (long-term immunity) antibodies. Positive results indicate prior or ongoing HBV infection. This test is the only way to differentiate vaccination from infection. An IgM antibody test is also available. However, IgM anti-HBc should only be used in cases where acute HBV infection is suspected, and it should not be used routinely for screening of prior infection. |

Abbreviations: HBV - hepatitis B virus; HBsAg - hepatitis B surface antigen; IgM - immunoglobulin M; IgG - immunoglobulin G; anti-HBc - hepatitis B core antibody

Pathogenesis

The natural history of HBV infection varies as a function of host immunity and patient age at primary infection. In addition, factors such as viral load, HBV genotype, and viral mutations can alter the course of HBV infection. Most primary infections spontaneously resolve in immunocompetent adults; however, a large percentage of individuals infected perinatally develop CHB later in life due to persistent viral replication. Unfortunately, even in patients with prior HBV infection, HBV DNA may persist as covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) within hepatocytes, placing these patients at risk of HBVr.6 Patients previously exposed to HBV show varying rates of viral replication due to partial control exerted by the immune system. Exposure to immunosuppressive therapy or elimination of hepatitis C virus (HCV) can disrupt virologic control inducing HBVr in these patients.8

The onset of HBVr may be delayed, occurring as late as 12 months after cessation of the inciting drug exposure.9–11 Clinical presentation of HBVr with hepatitis flare may vary from asymptomatic hepatitis to fulminant hepatic failure.11 Symptoms are similar to primary HBV infection and include severe fatigue, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, body aches, and jaundice.2, 7 Laboratory testing for reactivation can be done by measuring changes in HBV DNA and serum ALT.12

Diagnosis

Early studies diagnosed HBVr using hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) titers. With development of quantitative HBV DNA assays, HBVr can be identified by the relationship between the administration of immunosuppressive therapies, the development of hepatitis, and the rise in HBV DNA.13 Close monitoring of patients can lead to early diagnosis and allow for prompt management of HBVr.

One of the most common ways of detecting HBVr is through monitoring serum ALT. It is typical to see a rise in ALT levels 2 to 3 weeks prior to a rise in HBV DNA.13 Historically, there has not been a uniform definition for HBVr, leading to heterogeneity among studies evaluating its diagnosis and management. However, recent guidelines from major American and Asian hepatology societies offer more formal definitions (Table 2), but European guidelines are less explicit.7, 12, 14 Commonly used criteria include an increase in ALT levels, detection of HBsAg, and the emergence or elevations of HBV DNA from baseline.15–17 In addition, HBVr has been defined as HBsAg reverse seroconversion with or without abnormal ALT levels.16, 17

Table 2:

Definitions for Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation and Hepatitis Flare

| AASLD7 | EASL12 | APASL14 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV reactivation | 1. Elevation in HBV DNA compared to baseline or absolute increase if baseline is unavailable. 2. Seroconversion to HBsAg positive for HBsAg-negative, HBcAb-positive patients. |

Not defined | 1. Greater than 2 log increase from baseline levels or a new appearance of HBV DNA to a level of 100 IU/ml or more in a person with previously stable or undetectable levels, 2. Detection of HBV DNA with a level ≥20,000 IU/ml in a person with no baseline HBV DNA |

| Hepatitis flare | ALT elevation greater than 3 times the baseline level and greater than 100 U/L | Not defined | Intermittent elevations of serum aminotransferase levels to more than 5 times the upper limit of normal and greater than twice the baseline value |

Abbreviations: AASLD - American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL - European Association for the Study of the Liver; APASL - The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; HBV - hepatitis B virus; HBsAg - hepatitis B surface antigen; HBcAb - hepatitis B core antibody; ALT - alanine aminotransferase.

Risk Factors

Key risk factors for HBVr can be categorized as virologic, host, and immunosuppressive factors.18 Virologic factors associated with the highest risk of reactivation include high baseline HBV DNA, hepatitis B envelop antigen (HBeAg) positivity, and CHB, defined as HBsAg positivity for 6 months or more.13 Other virologic factors such as HBV genotype and co-infection with other viruses, such as HCV or hepatitis D, may also increase the likelihood of HBVr.18 Host factors associated with HBVr include older age, male sex, cirrhosis, and underlying disease requiring immunosuppression (e.g. lymphoma, solid tumors, rheumatoid arthritis).19 A significant determinant of HBVr risk involves the type and degree of immunosuppressive therapies that a person receives. These drugs and/or drug regimens can be categorized broadly based upon their HBVr risk as high, moderate, and low risk.20

Host and Virologic Factors

Viral risk factors for HBVr include detectable HBV DNA levels and other HBV markers such as HBeAg, HBsAg, and total hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc).11 A study investigating these risk factors found detectable levels of HBV DNA to be a major risk when 37.8% of the participants with detectable levels had HBVr.21 Patients with detectable HBsAg have up to an 8-fold increased risk of HBVr compared to HBsAg-negative/anti-HBc-positive patients.22 Likewise, patients who are HBeAg-positive are more likely to experience HBVr compared to HBeAg-negative patients.21 Mutations of HBsAg may also impair humoral response, thereby increasing HBVr risk.11 Finally, HBV genotype may also be a risk factor, but further studies are needed to evaluate this association.11, 16

Medication-related risk factors

Immunosuppressive and chemotherapeutic medications pose the greatest risk of causing HBVr. The American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) categorizes drugs based on their potential to cause HBVr using available evidence.20 Drugs with potential to cause HBVr in greater than 10% of cases are classified as high risk and include B-cell-depleting agents such as rituximab and ofatumumab, anthracycline derivatives such as doxorubicin and epirubicin, and moderate-dose corticosteroid therapy (e.g., 10–20 mg prednisone daily) or high-dose corticosteroid therapy (e.g. >20 mg prednisone daily) lasting greater than or equal to 4 weeks.20 Classes of moderate HBVr risk drugs (1–10% anticipated HBVr rate), include tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors, cytokine and integrin inhibitors, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI)s.20 Anticipated HBVr rates less than 1% of cases (low HBVr risk drug classes) include traditional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and methotrexate, and any dose corticosteroid therapy lasting less than a week or low-dose corticosteroid therapy (e.g. <10 mg prednisone daily) lasting greater than or equal to 4 weeks (See Table 3).20 We review the HBVr-related information for high- and moderate-risk immunosuppressive drugs, and we also review data with HCV direct-acting antivirals (DAA), which have been implicated as a cause of HBVr in patients co-infected with both viruses.

Table 3:

Definitions, Causes, Screening, and Treatment Consideration Based on Risk of Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation

| High Risk | Moderate Risk | Low Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Anticipated incidence of HBVr >10% | Anticipated incidence of HBVr 1–10% | Anticipated incidence of HBVr <1% |

| Causative Drugs | -B-cell depleting agents -Anthracycline derivatives -High-dose corticosteroids (≥20 mg prednisone for ≥4 weeks) |

-TNF-α inhibitors -Cytokine or integrin inhibitors -Tyrosine kinase inhibitors -Moderate-dose corticosteroids (10–20 mg prednisone for ≥4 weeks) |

-Traditional immunosuppression -Intra-articular corticosteroids -Systemic corticosteroids for <1 week or low-dose corticosteroids (<10 mg prednisone) ≥ 4 weeks |

| Screening for Serological Markers | HBsAg and anti-HBc, followed by HBV DNA if positive | HBsAg and anti-HBc, followed by HBV DNA if positive | -Routine screening not recommended by AGA -All persons requiring immunosuppressive therapy should be screened for HBsAg according to the CDC |

| Prophylaxis Needed | Yes | Yes | No |

| Monitoring | Yes, for 6–12 months after cessation of prophylaxis then occasionally long term | Yes, for 6–12 months after cessation of prophylaxis then occasionally long term | Yes, every 1–3 months |

Abbreviations: HBV - hepatitis B virus; HBVr - hepatitis B virus reactivation; AGA - American Gastroenterology Association; CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HBsAg - hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBc - hepatitis B core antibody; TNF-α - tumor necrosis factor alpha; ALT - alanine aminotransferase.

Rituximab and Ofatumumab.

Rituximab and ofatumumab are humanized antibodies that block humoral immunity by binding to CD20, a cell-surface marker on B lymphocytes;23, 24 both drugs are associated with high risk of HBVr. Rituximab affects cell signaling which induces death of malignant B cells, mediates complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CMC) of B cells, and induces antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) mediated by effector cells, such as macrophages, natural killer cells, and granulocytes.25 Ofatumumab has a similar mechanism of action. In CHB infection, HBV DNA persists within hepatocytes even among persons who have undetectable levels of circulating HBV DNA.24 Among persons who are seronegative for HBsAg but have detectable anti-HBc, HBV DNA is rarely found in the circulation but trace amounts are often found within the liver and can be reactivated when the immune response is suppressed, as is the case with rituximab or ofatumumab.24 Between the years of 1997 and 2009, 118 cases were reported to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) MedWatch Database in which rituximab was associated with HBVr.26 In 2013, the manufacturers of rituximab and ofatumumab added Boxed Warnings to the product labels identifying these agents as being associated with high HBVr risks.23

Several studies reported HBVr and serious HBV-related complications among persons in Asia with lymphoma who received rituximab. A study from Hong Kong examined the risk of HBVr among 104 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma undergoing treatment. Of these 104 patients, 46 were HBsAg negative and anti-HBc positive.24 Twenty-one of these patients were treated with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and 25 were treated with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) alone. Of patients treated with R-CHOP, five (25%) developed HBVr, including one who died of hepatic failure. None of the patients treated with CHOP therapy developed HBVr.24 There are two important take-home messages from this study. Firstly, the addition of rituximab significantly increased risk of HBVr even among patients with prior HBV exposure (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive). Secondly, it is interesting that in this study that there were no patients who developed HBVr after receiving CHOP, which contains doxorubicin and prednisone. Both are also implicated as moderate-to-high risk medications as discussed in the following sections, but it is possible that the sample size was too small to detect any cases.

A review of 115 CD20-positive non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma(NHL) patients in Taiwan examined the risk of HBVr among those receiving at least one dose of rituximab treatment. Patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) were excluded. Fifteen of these patients were HBsAg-positive, and 10 of these 15 patients did not receive antiviral prophylaxis during treatment.27 Seven of the 10 patients developed HBV-related hepatitis during lymphoma treatment and fatal hepatic failure occurred in one patient despite treatment. Four of the 10 patients developed HBV-related hepatitis after the first cycle of rituximab-containing therapy.27 Another patient developed delayed hepatitis 3 months after his last lymphoma treatment. Thus, 80% of patients in Taiwan who were HBsAg-positive and received rituximab therapy without lamivudine prophylaxis experienced HBV-related hepatitis, including one patient who died of hepatic failure.27 Of 95 patients with NHL who were HBsAg-negative, 15 experienced hepatitis flares including four with reappearance of HBsAg among patients who were previously HBsAg-negative in conjunction with icteric hepatitis. Of these four patients, two died despite lamivudine treatment.27

In a review of 278 patients in China with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab and chemotherapy between 2004 and 2008, six patients developed HBVr. All six had a history of prior HBV infection (anti-HBc-positive, HBsAg-negative). All 278 patients were negative for HBV DNA prior to receiving rituximab-containing therapy.28 There was a higher incidence of hepatitis in the anti-HBc-positive group compared with the anti-HBc-negative group (21.8% vs. 8.2%, respectively). Additionally, patients with elevated ALT or AST levels were more likely to develop hepatitis than those with normal serum transaminase values.28 The authors concluded that patients in China with prior HBV exposure (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive) were at greater risk for developing hepatitis due to HBV reactivation after rituximab-containing chemotherapy compared with HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-negative patients.28 Close monitoring of liver function and HBV DNA levels in patients in China with prior HBV exposure was urged.

To date, no large series of ofatumumab-treated patients from Asia has been reported. An observational study examined the incidence of HBVr among 65 cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) where ofatumumab was used as a second-line CLL treatment option. Of these patients, four were anti-HBs positive, and none of these four developed reactivation.29 However, as mentioned above, the FDA issued a black box warning alerting physicians and patients of the increased risk of HBVr while undergoing immune-suppressing ofatumumab therapy.23

Doxorubicin

Doxorubicin is used to treat a wide variety of hematologic and nonhematologic cancers, including leukemia, lymphoma, breast cancer, and multiple myeloma. It is difficult to disentangle the risk of HBVr that is directly attributed to doxorubicin, since it is often used in combination with other immunosuppressive agents including rituximab and systemic corticosteroids. However, up to half of patients with prior HBV exposure experience reactivation when undergoing therapy with this agent.30 The molecular mechanism of HBVr following administration of doxorubicin is via increased expression of the cell cycle regulator p21, which enhances HBV transcription and leads to an increase in viral replication.30

A large retrospective chart-review was conducted of 1149 patients receiving common doxorubicin-based (n=434), oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-based (n=196), carboplatin-gemcitabine (n=245), and capecitabine (n=274) chemotherapy regimens for solid tumors between January 2007 and December 2010.31 The primary purpose of the study was to evaluate HBV screening rates, but hepatitis flare and HBVr were also assessed. Of the 448 patients screened for HBV, 30 (7%) were HBsAg-positive and 28 received antiviral prophylaxis with none developing HBVr. In the unscreened group, 0.4% (3 out of 701) had confirmed HBVr and all three were breast cancer patients who had received doxorubicin (3 out of 214). One patient with HBVr developed fulminant hepatic failure and died. The two other patients recovered but had lengthy delays in their cancer regimen.31

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are prescribed at a range of doses and durations, depending on the indication, and have been associated with HBVr. Corticosteroids enhance hepatitis viral replication through two different mechanisms. One mechanism involves depressed cytotoxic T-cell function, and the other involves direct stimulation of an HBV genomic sequence by interacting with the HBV glucocorticoid responsive element.11 In an observational study comparing HBVr among HBsAg-positive patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who were exposed to inhaled corticosteroids alone (n=126) or in combination with systemic corticosteroids (n=72), 12 cases of HBVr were identified. Eight patients with HBVr received systemic and inhaled corticosteroids, and of these only one patient received steroids at a dose of less than prednisone 20 mg/day. The remaining four patients experiencing HBVr received inhaled corticosteroids alone at a dose equal to fluticasone 100 to 200 μg per day.32 The authors concluded that addition of systemic corticosteroids to inhaled corticosteroids causes an increased risk in HBVr, more so when systemic corticosteroids are administered chronically or at moderate-to-high doses.32

TNF-α Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists, including infliximab, etanercept, golimumab, and adalimumab, are widely utilized for treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis.33 Experimental studies have shown that TNF inhibits hepatitis viral replication and stimulates HBV-specific T-cell responses to clear the virus from infected hepatocytes, leading researchers to believe inhibiting TNF could cause increased expression of hepatitis B viral antigens.33

The incidence of HBVr was investigated in a study of 87 HBV patients with inflammatory arthritis who were using TNF-α antagonists (infliximab or etanercept).34 Patients were grouped according to HBV status: six patients were confirmed to have CHB infection (HBsAg persistently positive, HBV DNA > 105 copies/ml, elevated ALT); another 31 patients were determined to be HBV carriers (HBsAg-positive, HBV DNA < 104 copies/ml, persistently normal ALT); and the remaining 50 patients had prior HBV infection with no evidence of active disease (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive). Among the six patients with CHB, four received antiviral prophylaxis and none experienced HBVr during treatment (mean 4.7 months; range 2 to 9 months) or follow-up (mean 8.7 months; range 2 to 22 months). Both CHB patients with HBVr who did not receive antiviral prophylaxis received etanercept. The etanercept was interrupted and lamivudine instituted with normalization of ALT and HBV DNA in both patients. Of the 31 patients in the HBV-carrier group, nine patients received antiviral prophylaxis and none of these experienced HBVr. Of the remaining 22 HBV carriers without antiviral prophylaxis, 16 patients had no viral replication and the remaining six patients experienced increased HBV DNA. Four of these patients also experienced elevations in ALT in addition to HBV DNA increases, meeting criteria for HBVr. Three of the six patients with elevated HBV DNA stopped treatment, one stopped infliximab and initiated lamivudine, one switched from infliximab to etanercept, and one continued etanercept without antivirals. All six patients had decreases in HBV DNA and were eventually undetectable without causing hepatitis flare during follow-up (mean 17.3 months, range 5–37 months). The remaining 50 patients with prior exposure (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive) had no increases in HBV DNA or ALT attributed to infliximab or etanercept. No cases of HBVr were reported in these patients during follow-up (mean 12 months, range 4–18 months).34

Although HBVr has only been associated with infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab thus far, it is unknown at this point whether other agents in this drug class carry the same risk.33 However, it seems likely that all TNF antagonists have potential to cause HBVr, particularly among those who are HBsAg-positive. As with other medications, patients with prior exposure (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive) have demonstrated a lower risk of HBVr. The risk of HBVr is reflected in the addition of warning statements in the prescribing information for all FDA-approved anti-TNF medications. Patients for whom TNF antagonists are considered should undergo screening for HBV infection prior to initiation of any medication from this class.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are used to treat a variety of malignancies including lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Limited evidence, primarily case reports or case series, describes HBVr in HBsAg-positive patients receiving treatment with TKIs.17 Though the mechanism by which these agents work to induce reactivation remains unclear, some in vitro studies have shown that TKIs can inhibit T-cell activation and proliferation.17 Recent studies show imatinib mesylate has immunosuppressive action by inhibiting T-cell functions as well as tyrosine kinase Lck, which is a T-cell maturation and activation regulator. Frequently, patients undergoing imatinib therapy develop lymphocytopenia (24%−47% of cases) or neutropenia (35%−58% of cases).35

Imatinib mesylate was the first TKI approved by the FDA to treat CML in 2001.35 It has been linked to HBVr in several case reports. One report described a 54-year-old male with CML without prior liver dysfunction but with CHB (HBsAg-positive, anti-HBc-positive, HBeAg-positive) who was treated with imatinib mesylate beginning in November 2003. This patient developed fulminant hepatitis due to HBV reactivation 6 months after TKI initiation, and despite antiviral treatment, he died of HBV-related complications.35

Dasatinib is another small molecule TKI used to treat Philadelphia chromosome-positive CML and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cytopenia (anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia) is an adverse effect experienced with this drug, as well as grade 3 and 4 elevations in serum transaminase and bilirubin levels.36 The first case report of HBVr associated with dasatinib described a 74-year-old woman with accelerated phase CML. She was first treated with imatinib but was switched to low-dose dasatinib due to imatinib-related pleural effusion. Three years after initiation of dasatinib a positive diagnosis for HBVr was made. At the time of HBVr diagnosis the patient had converted from HBsAg-negative (prior to TKI treatment) to HBsAg-positive status, asymptomatic elevation of AST (80 IU/ml) and ALT (83 IU/ml), and elevated HBV DNA (6.9 log10 copies/ml), which was previously undetected. Lamivudine 100 mg/day was administered, and 2 months later her elevated AST and ALT levels returned to normal.36

Ruxolitinib is a potent Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 inhibitor used for patients with myelofibrosis (MF).37 A case study reported a 72-year-old male patient with confirmed MF who was a known to be HBsAg-positive with normal liver function tests (LFTs) for decades. He was treated with ruxolitinib at a 40-mg/day dose and had a complete resolution of his symptoms and a significant reduction in spleen size.37 However, 8 weeks after initiation of therapy he experienced a rise in serum ALT (179 IU/ml) and AST (136 IU/ml). Clinicians thought this was drug-related, and ruxolitinib dosing was dropped to 10 mg twice daily, the maintenance dose; however, serum ALT (291 IU/ml) and AST (185 IU/ml) levels continued to rise and remained elevated 1 month after cessation of the drug.37 A high titer of HBV DNA (1.23×107 copies/ml) and serological testing confirmed HBVr. Antiviral treatment with entecavir was initiated and serum ALT and AST levels declined.37

Bortezomib

Bortezomib is a selective proteasome inhibitor FDA approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). Patients undergoing stem cell transplantation for MM following immunosuppressive therapy including bortezomib had notable rates of HBVr. A study evaluated 139 hospitalized patients with MM receiving bortezomib-containing regimens.38 Of these patients, 27 were HBsAg positive with 9 having HBV DNA levels greater than 500 IU/ml, including 4 with levels above 1000 IU/ml. All HBsAg-positive patients were to receive antiviral prophylaxis with lamivudine 100 mg or entecavir 0.5 mg daily before chemotherapy until at least 6 months after chemotherapy or autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT); however, five patients did not take antivirals for the prescribed timeframe due to various reasons, including nonadherence.38 During the follow-up period, HBVr occurred in eight patients: six were HBsAg positive and two were HBsAg negative. Six of these eight patients received ASCT with the median time to HBVr from ASCT of 392 days (range, 100 to 1048 days). All eight cases of HBVr received antiviral treatment, but two patients died of fulminant hepatitis despite antiviral treatment.38

A case referenced in a letter described bortezomib-associated HBVr in a 58-year-old male diagnosed with MM. This patient had presence of HBsAg and HBeAg, with a serum HBV DNA level of 350,000 copies/ml and normal aminotransferase levels, and was treated with eight 3-weekly courses of bortezomib at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2/day on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, on lamivudine prophylaxis after being refractory to a VAD (vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) regimen.39 With the lamivudine prophylaxis, HBV DNA levels were undetectable during treatment. The patient was lost to follow-up and discontinued lamivudine sometime following the last bortezomib dose. The patient returned to care 9 months after treatment and HBV DNA remained undetectable; however, 18 months post-bortezomib therapy HBV DNA levels increased to 20,000 copies/ml (liver enzymes were not reported). Although inappropriate lamivudine prophylaxis could be a contributing factor, this case illustrates the potential for very late HBV DNA emergence and HBVr among HBsAg-positive patients receiving bortezomib therapy.39

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Individuals who receive HSCT are also at risk of developing HBVr. Agents used to suppress the immune system after HSCT, such as cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and rituximab, have improved outcomes for transplant recipients. However, potent immune suppression increases the risk of HBVr in patients receiving HSCT who have had prior hepatitis B infection.

A retrospective study examined the incidence of HBVr among 413 patients with hematologic malignancies who were recipients of HSCT. All five patients receiving HSCT who were HBsAg-positive experienced HBVr, and all HBVr events were controlled with the administration of either lamivudine or entecavir.40 Of 408 patients receiving HSCT who were HBsAg-negative, 11 experienced HBVr. These individuals had varying serological markers (anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs). Reactivation events that occurred in the HBsAg-negative group were also controlled with lamivudine or entecavir. This study demonstrated the importance of identifying the status of anti-HBc and anti-HBs, as well as HBsAg, before performing HSCT.40

Direct-Acting Antivirals for Hepatitis C

Treatment of HCV with DAAs in patients coinfected with HBV-HCV may cause reactivation of HBV. From November 2013 to July 2016, 29 unique reports of HBVr were identified in patients coinfected with HBV-HCV who were treated with DAAs for HCV. One case resulted in liver transplantation, and two other cases resulted in death.41 Based on these reports, the FDA issued a warning about the potential risk of HBVr in patients treated with DAAs for HCV. One of the largest studies to evaluate HBVr was among 62,920 veterans treated with DAAs for HCV infection.42 Prior to DAA initiation, 85.5% (n=53,784) of patients were tested for HBsAg and 0.70% (n=377) were positive. Overall, only nine patients had evidence of HBVr, defined as greater than 1 log increase in HBV DNA or HBsAg detection in someone who was previously negative. Eight of these patients were known to be HBsAg-positive, and the other patient was known to be isolated anti-HBc-positive.42 Similarly, in a prospective, open-label study of 111 patients with HBV-HCV co-infection treated with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir, there were only five patients with increased HBV DNA and ALT greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal.43 All but one patient was HBsAg-positive, and only three patients required treatment with HBV antivirals. Importantly, 100% of patients completed HCV DAA therapy and achieved a sustained virologic response.43 In one recent study of 103 patients with prior HBV exposure (isolated anti-HBc-positive) receiving DAA therapy for HCV infection, no patients experienced HBVr.44

Although the overall risk of HBVr with DAAs would be considered low by most experts, the risk is highest among patients who are HBsAg-positive, and the risk in HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive patients is much lower. Hepatitis associated with HBVr tends to occur earlier and is clinically more significant among patients receiving oral DAAs for HCV infection who are HBsAg-positive.45

Prevention and Management

Screening

Patients with prior hepatitis B exposure are at an increased risk of reactivation when undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, but controversy exists on the best HBV screening strategy. In 2008, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that patients undergoing cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy of any kind be screened for HBV serologic markers (positive HBsAg and positive anti-HBc, HBV DNA if serology positive).20, 46 Studies evaluating HBV screening based only on risk factors have found that screening is mostly ineffective. One study of Veterans with cancer undergoing chemotherapy or immunotherapy compared the rate of screening prior to and after dissemination of the CDC guidelines; no significant increase in screening was found.47

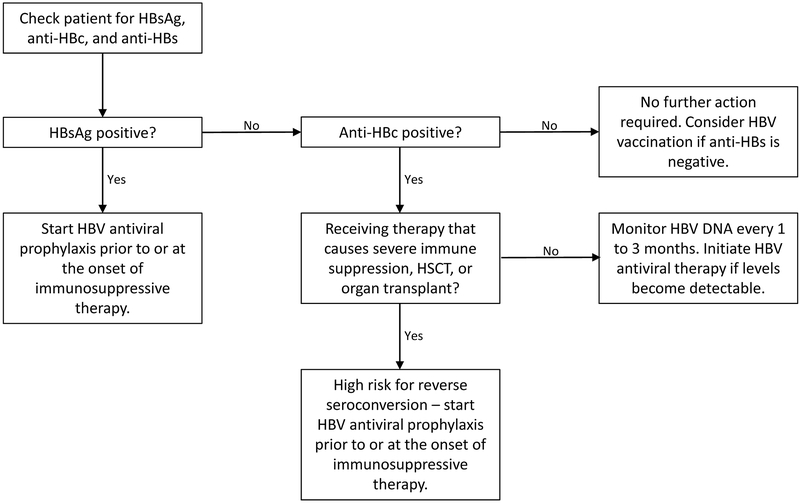

Until effective means of systematically screening and identifying patients at high risk of HBVr are developed, all patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy should be tested prior to treatment. Similarly, due to overlapping risk factors for infection and complications related to HBVr, it is recommended that all patients undergoing treatment with HCV DAAs be screened for HBV.45 If positive HBV serologies are identified, these patients can be risk stratified. Patients at highest risk can undergo prophylactic treatment with anti-HBV nucleoside analogues and have a much greater chance of avoiding HBVr (See Figure 1).13

Figure 1: System for Screening Individuals Prior to Undergoing Immunosuppressive Therapy.

Abbreviations: HSCT - hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; anti-HBs – Hepatitis B surface antibody; HBV – hepatitis B virus; HBsAg – hepatitis B surface antigen; anti-HBc – hepatitis B core antibody;

Prophylaxis

After screening, the next facet in prevention and management of HBVr is to take further protective action for individuals receiving immunosuppressive medications by administering prophylactic antiviral therapy. The AGA recommends prophylaxis for patients undergoing high-risk and moderate-risk immunosuppressive therapy and states that prophylaxis should be continued for 6 months post discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy (12 months if B-cell-depleting agents were used).20 For patients receiving low-risk immunosuppressive therapy, routine use of antiviral prophylaxis is not recommended. Apart from the high-risk immunosuppressive medications, these are weak recommendations based on moderate-quality evidence (See Figure 1).20

As seen in a retrospective study of patients with gastrointestinal cancer, antiviral prophylaxis greatly decreases the risk of HBVr in individuals receiving high-risk therapies.48 In a group of 156 patients with gastrointestinal cancer who were HBsAg-positive, 76 patients had unknown HBV DNA levels (none of whom received antivirals), and 80 had HBV DNA levels assessed at baseline (median, 4230 copies/ml). Thirty-nine patients with known HBV DNA levels received prophylactic antiviral therapy throughout chemotherapy and were recommended to continue antiviral nucleoside analogs for 6 months following chemotherapy; the remaining patients in the study (117 individuals; 41 of which had baseline levels of HBV DNA) did not receive antiviral prophylaxis.48 Patients were monitored for HBV DNA copies every 2 to 3 months during chemotherapy. None of the patients who received antiviral prophylaxis experienced HBVr, whereas 14.6% (6 of 41) of patients with baseline HBV DNA levels available who did not receive antiviral prophylaxis experienced HBVr (P = 0.039). An additional five of the 76 patients with unknown HBV DNA levels developed HBVr during the study.48

Currently, there are several nucleoside analogues available for prophylaxis of HBVr, including lamivudine, adefovir, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), tenofovir alafenamide (TAF), and entecavir.13 No currently approved antiviral is specifically indicated for prevention of HBVr. Lamivudine was the first nucleoside analogue used as antiviral prophylaxis to reduce HBVr complications. However, the development of resistance in patients requiring prolonged duration of therapy may lead to re-emergence of HBV DNA and risk of HBVr. Newer nucleoside agents, such as entecavir, TDF, and adefovir, have an increased barrier to resistance providing additional options for antiviral prophylaxis.49 In a study conducted to evaluate tenofovir for HBVr prophylaxis., 38 patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy received TDF. Of these 38 patients, 25 were receiving TDF for prophylaxis and had no documented HBVr. The remaining 13 patients were receiving TDF as treatment of HBVr and all had normal LFTs and undetectable HBV DNA within 9 months of TDF initiation, including one patient with decompensated cirrhosis from HBVr who returned to a compensated state with TDF treatment. None of the patients receiving TDF for prophylaxis or as treatment experienced exacerbation of liver disease or adverse reactions to the therapy.50

Like TDF, TAF is a nucleotide analog that inhibits HBV DNA replication initially approved by the FDA in 2015 for treatment of CHB. The primary advantage of TAF is that it is more stable in plasma resulting in equivalent active metabolite concentrations within hepatocytes despite using a lower dose. Although a lower dose is used, similar antiviral activity is observed with less systemic exposure, and lower rates of bone and renal toxicity.51 Although not specifically studied for prevention of HBVr, it is likely that TAF would have similar efficacy in preventing HBVr compared to TDF.

The optimal time of initiation of antivirals to prevent HBVr is still a topic of debate. A study to answer this important question was conducted to determine whether prophylactic antiviral therapy should be initiated prior to initiation of chemotherapy, at the initiation of chemotherapy, or deferred until virologic reactivation of HBV was evident.52 Thirty HBsAG-positive patients with lymphoma were randomized to two groups. Group 1 received preemptive lamivudine therapy 1 week prior to starting chemotherapy; group 2 only received lamivudine therapy when there was evidence of HBVr. Serological monitoring was performed, and HBV DNA levels were measured in these patients every 2 weeks. Both groups continued to receive lamivudine therapy for 6 weeks after it was initiated. Eight (53%) patients in group 2 and none in group 1 experienced HBVr (P=0.002).52 Of the eight patients in group 2 who were treated with lamivudine, seven developed clinical hepatitis. Thus, the authors from this study concluded that preemptive prophylaxis with antiviral therapy is preferred.52

One concern when using preemptive lamivudine prophylaxis is development of resistance caused by point mutations in the HBV DNA polymerase chain. The risk of developing these mutations increases as the duration of therapy is prolonged.52 Adefovir, TDF, and entecavir are effective when lamivudine resistance is a concern.53

Though all these options have been useful, entecavir has been identified as the most effective when used as HBVr prophylaxis. One meta-analysis compared six different prophylactic options for the recurrence of HBV in patients undergoing liver transplantation and found entecavir to be superior to lamivudine, TDF, adefovir, lamivudine plus adefovir, and lamivudine plus TDF.53 Another clinical trial focused more narrowly on comparing entecavir to lamivudine for prophylaxis in patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP chemotherapy. The 121 patients in this study who were seropositive for HBsAg and had normal liver function, serum HBV DNA levels, and no prior antiviral use were randomized to receive prophylactic entecavir or lamivudine.54 This study also showed that entecavir, when compared with lamivudine, resulted in a lower incidence of HBVr, with patients receiving entecavir showing only a 6.6% reactivation rate, whereas those receiving lamivudine had a 30% reactivation rate (P = 0.001).54

Monitoring & Managing

Hepatitis B serology and HBV DNA monitoring of patients receiving antiviral prophylaxis is essential following cessation of prophylactic therapy. However, there is debate as to how long monitoring is necessary. Some suggest monitoring for up to 6 months after therapy, whereas others propose monitoring for at least 12 months, if not long term.11

Monitoring is also an important consideration for patients who do not undergo antiviral prophylaxis. This population includes patients who are prescribed lower potency or limited duration immunosuppressive drug regimens; for this lower-risk population, prophylaxis is generally considered an overprotective, unnecessary measure. The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommends specific monitoring of HBV DNA and ALT levels should occur every 1 to 3 months.11 However, due to inconsistent clinical studies and poor evidence, the AGA guidelines do not provide a specific strategy for monitoring HBV DNA in lower-risk patients.20 One prospective study monitored serial HBV DNA in 223 patients with B-cell NHL at intervals of 30 days over the course of 1.5 years to evaluate HBVr risk among lower-risk patients. After 1.5 years, the incidence of HBV reactivation was 8.3%.55 Hepatitis due to reactivation was prevented by administering antiviral treatment when HBV DNA exceeded 11 IU/ml. If baseline HBV DNA levels below 11 IU/ml were confirmed, serial monitoring of HBV DNA (without prophylaxis of antiviral drugs) was performed.55 Monitoring HBV serology and HBV DNA is an alternative approach to prophylaxis therapy and avoids the issues of resistance development.

Discussion

Hepatitis B reactivation is an increasingly recognized complication following immunosuppression for both cancer and non-cancer diagnoses. There are several gaps in our understanding of this disease process, namely: i) what is the optimal screening strategy for identifying patients at risk of HBVr? ii) which patients should receive antiviral prophylaxis? and iii) which antiviral agent should be used and what is the optimal duration?

Recommendations regarding screening for prior HBV infection have been published by several groups, but inconsistencies have led to confusion resulting in varying rates of compliance with screening. There are several screening strategies that have been proposed including risk factor-based, risk-adaptive, and universal screening. The limitations of risk factor-based screening are that many patients are unaware of prior HBV exposure or are unwilling to admit to high-risk behaviors associated with HBV infection. Risk-adaptive strategy involves screening based upon both risk factors and receipt of agents deemed to be high risk for HBVr. It is worth noting that asking about prior HBV vaccination or testing for anti-HBs alone is not a sufficient screening strategy. Patients who have responded to HBV vaccination will have a positive anti-HBs, but persons previously exposed to HBV may also test positive for anti-HBs. The only way to differentiate between immunity due to natural infection versus vaccination is to test for total anti-HBc. Hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) will only be positive in patients with prior exposure to HBV. Finally, universal screening involves screening everyone undergoing immunosuppressive drug therapy, such as chemotherapy. The benefits of universal screening extend beyond identification of patients at risk for HBVr, including identification of CHB-infected patients who were previously unaware of their infection status. As stated previously, patients chronically infected with HBV require ongoing surveillance for hepatoma and to evaluate the need for antiviral therapy. However, these benefits need to be weighed against the overall increase in cost to the health care system.

Identifying patients who should receive HBV antivirals is another area of considerable debate. Two strategies exist and deserve consideration. Prophylaxis with antivirals started prior to or at the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy is suggested as a management option. The second option is referred to as “deferred therapy” and involves observing for increases in aminotransferase or HBV DNA elevations prior to initiating antivirals. These strategies must be compared in relation to the severity of immunosuppression, risk classification attributed to the specific medication, and virologic characteristics. Among patients receiving rituximab for lymphoma, HBsAg-positive patients untreated with antivirals had a much higher baseline risk of HBVr (mean, 54%; range 53%−55%) compared to HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive patients where the mean proportion of HBVr occurrence was lower (mean, 12.2%; range, 3.2%−23.8%).17 Major guidelines are in agreement that patients at highest risk of HBVr, such as HBsAg-positive patients receiving rituximab, should be considered for prophylactic antivirals.7,12,14 It is less clear, and probably should depend on the immunosuppressive regimen, whether to administer prophylactic antivirals or employ a “deferred therapy” approach among individuals treated with medications associated with moderate or low risk of HBVr.

There is no consensus on the specific agent to be used for HBVr prophylaxis. Lamivudine has demonstrated in clinical trials and observational studies to prevent HBVr. However, the most recent American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines recommend against using lamivudine for HBVr prophylaxis owing to development of resistance.7 Therefore, lamivudine should be limited to scenarios where the duration of treatment is expected to be short due to potential for resistance with prolonged therapy. Generally, there is less evidence for tenofovir and entecavir in HBVr prophylaxis, but their use is based upon strong evidence in CHB treatment. Tenofovir and entecavir have an increased barrier to resistance, so they can be used without consideration of the expected duration of therapy, and these agents are generally preferred for HBVr prophylaxis in most settings. Data supporting TAF is lacking in HBVr, although it is likely comparable to TDF based upon studies in CHB. Guidelines differ on the duration of antiviral prophylaxis,7,12,14 but generally range between 6 to 12 months of treatment after cessation of immunosuppression. The optimal duration of HBVr prophylaxis is unknown.

Much of our understanding of HBVr is derived from uncontrolled observational studies and limited studies related to prevention. Most of the data comes from studies of persons who reside in areas of high prevalence or in patients of Asian descent. Additional well-designed clinical trials examining these knowledge gaps are needed. With additional awareness, screening, and appropriate antiviral therapy, it is expected that most cases of HBVr can be prevented.

Conclusion

Reactivation of HBV can occur following immunosuppressive therapy in patients previously exposed to hepatitis B, but the extent of reactivation varies considerably depending on patient, viral, and drug exposure. Outcomes from HBVr range from a mild hepatitis to severe episodes, which can lead to acute liver failure and death. Additionally, patients may experience delays in therapy due to HBVr; however, the full effects of this require further study. Of note, HBVr can be prevented with antivirals if identified prior to initiation of moderate-risk or high-risk immunosuppressive therapy. Many unanswered questions remain about the appropriate care and management of patients at risk for HBVr, making this a therapeutic area with opportunities for education and research to inform future recommendations.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the American Cancer Society (IRG-17-179-04) and the NIH National Cancer Institute (R01CA165609–01).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Drs. Love, Norris, and Bennett report receiving research grants from American Cancer Society during the development of the manuscript; Dr. Bennett reports receiving research grant from the National Cancer Institute during the development of the manuscript; Dr. Norris reports other relevant financial activities outside of the submitted work; and Drs. Kiger and Smalls report no conflicts.

References:

- 1.Suhail M, Abdel-Hafiz H, Ali A, et al. Potential mechanisms of hepatitis B virus induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol 2014;35:12462–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hepatitis B, 18 July 2018 Available from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed June 20, 2019,

- 3.Chen DS, Hsu HM, Bennett CL, et al. A program for eradication of hepatitis B from Taiwan by a 10-year, four-dose vaccination program. Cancer Causes Control 1996;3:305–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep 2018;1:1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology 2009;3:661–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2016;1:261–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 Hepatitis B Guidance. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2018;1:33–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusumoto S, Tobinai K. Screening for and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients treated with anti-B-cell therapy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2014;1:576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dai MS, Chao TY, Kao WY, Shyu RY, Liu TM. Delayed hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of preemptive lamivudine in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus CHOP. Ann Hematol 2004;12:769–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu C, Hsiung CA, Su IJ, et al. A revisit of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a randomized trial. Hepatology 2008;3:844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pattullo V. Prevention of Hepatitis B reactivation in the setting of immunosuppression. Clin Mol Hepatol 2016;2:219–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2017;2:370–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology 2006;2:209–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int 2016;1:1–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, Viveiros K, Balk EM, Wong JB. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation and Prophylaxis During Solid Tumor Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine 2016;1:30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mozessohn L, Chan KK, Feld JJ, Hicks LK. Hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients receiving rituximab for lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat 2015;10:842–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology 2015;1:221–44 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B Reactivation Associated With Immune Suppressive and Biological Modifier Therapies: Current Concepts, Management Strategies, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology 2017;6:1297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, et al. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol 2000;3:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter YT, American Gastroenterological Association I. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology 2015;1:215–9; quiz e16–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2004;7:1306–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shouval D, Shibolet O. Immunosuppression and HBV reactivation. Semin Liver Dis 2013;2:167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitka M. FDA: Increased HBV reactivation risk with ofatumumab or rituximab. JAMA 2013;16:1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol 2009;4:605–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner GJ. Rituximab: mechanism of action. Semin Hematol 2010;2:115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evens AM, Jovanovic BD, Su YC, et al. Rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in lymphoproliferative diseases: meta-analysis and examination of FDA safety reports. Ann Oncol 2011;5:1170–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei SN, Chen CH, Lee CM, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following rituximab-based regimens: a serious complication in both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients. Ann Hematol 2010;3:255–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen KL, Chen J, Rao HL, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and hepatitis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients with resolved hepatitis B receiving rituximab-containing chemotherapy: risk factors and survival. Chin J Cancer 2015;5:225–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno C, Montillo M, Panayiotidis P, et al. Ofatumumab in poor-prognosis chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a phase IV, non-interventional, observational study from the European Research Initiative on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Haematologica 2015;4:511–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen YF, Chong CL, Wu YC, et al. Doxorubicin Activates Hepatitis B Virus Replication by Elevation of p21 (Waf1/Cip1) and C/EBPalpha Expression. PloS one 2015;6:e0131743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling WH, Soe PP, Pang AS, Lee SC. Hepatitis B virus reactivation risk varies with different chemotherapy regimens commonly used in solid tumours. Br J Cancer 2013;10:1931–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim TW, Kim MN, Kwon JW, et al. Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with corticosteroids. Respirology 2010;7:1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathan DM, Angus PW, Gibson PR. Hepatitis B and C virus infections and anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy: guidelines for clinical approach. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;9:1366–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye H, Zhang XW, Mu R, et al. Anti-TNF therapy in patients with HBV infection--analysis of 87 patients with inflammatory arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2014;1:119–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikeda K, Shiga Y, Takahashi A, et al. Fatal hepatitis B virus reactivation in a chronic myeloid leukemia patient during imatinib mesylate treatment. Leuk Lymphoma 2006;1:155–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ando T, Kojima K, Isoda H, et al. Reactivation of resolved infection with the hepatitis B virus immune escape mutant G145R during dasatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol 2015;3:379–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen CH, Hwang CE, Chen YY, Chen CC. Hepatitis B virus reactivation associated with ruxolitinib. Ann Hematol 2014;6:1075–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Huang B, Li Y, Zheng D, Zhou Z, Liu J. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with multiple myeloma receiving bortezomib-containing regimens followed by autologous stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma 2015;6:1710–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beysel S, Yegin ZA, Yagci M. Bortezomib-associated late hepatitis B reactivation in a case of multiple myeloma. Turk J Gastroenterol 2010;2:197–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamoto S, Kanda T, Nakaseko C, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients in Japan: efficacy of nucleos(t)ide analogues for prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2014;11:21455–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bersoff-Matcha SJ, Cao K, Jason M, et al. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation Associated With Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus: A Review of Cases Reported to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Annals of internal medicine 2017;11:792–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Mole LA, Backus LI. Evaluation of hepatitis B reactivation among 62,920 veterans treated with oral hepatitis C antivirals. Hepatology 2017;1:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu CJ, Chuang WL, Sheen IS, et al. Efficacy of Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir Treatment of HCV Infection in Patients Coinfected With HBV. Gastroenterology 2018;4:989–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sulkowski MS, Chuang WL, Kao JH, et al. No Evidence of Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus Among Patients Treated With Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016;9:1202–04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen G, Wang C, Chen J, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in hepatitis B and C coinfected patients treated with antiviral agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017;1:13–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep 2008;RR-8:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leonard AN, Love BL, Norris LB, Siddiqui SK, Wallam MN, Bennett CL. Screening for viral hepatitis prior to rituximab chemotherapy. Ann Hematol 2016;1:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Du Y, Luo WX, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and hepatitis in gastrointestinal cancer patients after chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2015;4:783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tseng CM, Chen TB, Hsu YC, Chang CY, Lin JT, Mo LR. Comparative effectiveness of nucleos(t)ide analogues in chronic hepatitis B patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2016;4:421–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koskinas JS, Deutsch M, Adamidi S, et al. The role of tenofovir in preventing and treating hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in immunosuppressed patients. A real life experience from a tertiary center. Eur J Intern Med 2014;8:768–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott LJ, Chan HLY. Tenofovir Alafenamide: A Review in Chronic Hepatitis B. Drugs 2017;9:1017–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lau GK, Yiu HH, Fong DY, et al. Early is superior to deferred preemptive lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B patients undergoing chemotherapy. Gastroenterology 2003;6:1742–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng JN, Zou TT, Zou H, et al. Comparative efficacy of oral nucleotide analogues for the prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a network meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2016;10:979–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang H, Li X, Zhu J, et al. Entecavir vs lamivudine for prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation among patients with untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma receiving R-CHOP chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;23:2521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kusumoto S, Tanaka Y, Suzuki R, et al. Monitoring of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) DNA and Risk of HBV Reactivation in B-Cell Lymphoma: A Prospective Observational Study. Clin Infect Dis 2015;5:719–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]