Abstract

Introduction:

Brain swelling due to edema formation is a major cause of neurological deterioration and death in patients with large hemispheric infarction (LHI) and severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), especially contusion-TBI. Preclinical studies have shown that SUR1-TRPM4 channels play a critical role in edema formation and brain swelling in LHI and TBI. Glibenclamide, a sulfonylurea drug and potent inhibitor of SUR1-TRPM4, was reformulated for intravenous injection, known as BIIB093.

Areas covered:

We discuss the findings from Phase 2 clinical trials of BIIB093 in patients with LHI (GAMES-Pilot and GAMES-RP) and from a small Phase 2 clinical trial in patients with TBI. For the GAMES trials, we review data on objective biological variables, adjudicated edema-related endpoints, functional outcomes, and mortality which, despite missing the primary endpoint, supported the initiation of a Phase 3 trial in LHI (CHARM). For the TBI trial, we review data on MRI measures of edema and the initiation of a Phase 2 trial in contusion-TBI (ASTRAL).

Expert opinion:

Emerging clinical data show that BIIB093 has the potential to transform our management of patients with LHI, contusion-TBI and other conditions in which swelling leads to neurological deterioration and death.

Keywords: Glibenclamide, BIIB093, SUR1-TRPM4, large hemispheric infarction, stroke, traumatic brain injury, contusion, cerebral edema

1. Introduction

Cerebral edema is a frequently devastating complication of large hemispheric infarction (LHI). LHI represents approximately 10% of ischemic stroke cases [1]. Patients with LHI are at significant risk for neurological deterioration, partly due to neurological complications stemming from cerebral edema. Mortality in this patient population is 40–80% [2,3]. Worldwide, stroke accounts for approximately 5.5 million deaths annually [4].

Cerebral edema also is a common complication in patients with severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), especially contusion-TBI. Approximately 5.5 million people suffer from severe TBI yearly [5], and in the US, TBI contributes to 30% of all injury-related deaths [6]. Brain swelling, in part due to cerebral edema, is the strongest predictor of patient outcome, accounting for up to 50% of mortality in patients with severe TBI [7].

Cerebral edema also complicates a myriad of other neurological conditions associated with high morbidity and mortality, including intracerebral hemorrhage [8], subarachnoid hemorrhage [9], brain tumors [10], hepatic encephalopathy [11] and cerebral malaria [12], which together account for several million deaths worldwide each year.

2. Overview of the market

Current treatments for cerebral edema in patients with LHI and severe TBI are primarily reactionary. Treatments range from osmotic agents, including hypertonic saline and mannitol, to surgical intervention with decompressive craniectomy [13]. Despite their widespread use, osmotherapies have never been shown in controlled clinical trials to affect neurological outcome. Decompressive craniectomy, a potentially morbid procedure with its own associated complications [14], is known to reduce mortality in both LHI and severe TBI, but evidence for improved clinical outcomes is limited to select LHI patients, and is nonexistent in TBI [15,16].

Brain swelling complicates not only LHI but smaller strokes as well. Recent evidence indicates that swelling is an independent predictor of poor outcome in nonmalignant strokes, with a swelling volume of only 11 mL being the threshold with the greatest sensitivity and specificity for predicting poor outcome [17].

An alternative approach to the reactionary treatments of osmotherapy and decompressive craniectomy would be to inhibit the physiologic and molecular mechanisms responsible for the formation of edema and brain swelling. Emerging preclinical and clinical data suggest that edema in LHI and in contusion-TBI may be ameliorated by glibenclamide (a.k.a. Glyburide) (see Box 1), a second-generation sulfonylurea drug that was originally introduced in the 1960s as a treatment for diabetes mellitus type 2 [18].

Box 1.

Drug summary box.

| Drug name | BIIB093 (glibenclamide; Glyburide; RP-1127; Cirara) |

| Phase | 3 (large hemispheric infarction); 2 (contusion-TBI) |

| Pharmacology Description/mechanism of action | SUR1-TRPM4 inhibitor |

| Route of administration | Intravenous |

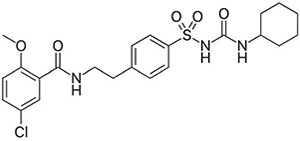

| Chemical structure | |

|

|

| Pivotal trials | GAMES-RP (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: ) |

| CHARM (ongoing; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: ) | |

| ASTRAL (ongoing; clinicaltrials.gov identifier: ) |

3. Glibenclamide

3.1. Inhibition of sur-regulated ion channels

Glibenclamide inhibits four molecularly distinct KATP channels, SUR1-KIR6.2, SUR2A-KIR6.2, SUR2B-KIR6.2, and SUR2B-KIR6.1, some of which are expressed constitutively by various cell types throughout the body [19-21]. Glibenclamide also is a potent inhibitor of SUR1-TRPM4 channels (previously called SUR1-regulated NCCa-ATP channels), which are not constitutively expressed, but are transcriptionally upregulated in all members of the neurovascular unit following cerebral ischemia or trauma [22,23]. In the case of these 5 ion channels, glibenclamide inhibits channel function by targeting the regulatory subunit, SUR, with the affinity of binding and the efficacy of channel inhibition being greatest for SUR1-regulated channels, compared to SUR2-regulated channels. In addition, glibenclamide inhibits the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, an effect that is independent of KATP or SUR [24].

Activation of the potassium selective channel, KATP, hyperpolarizes the cell membrane by allowing outward flow of potassium. In pancreatic β cells, binding of glibenclamide to KATP (SUR1-KIR6.2) results in cell depolarization, which leads to an influx of calcium that stimulates insulin release. Conversely, activation of the nonselective cation channel, SUR1-TRPM4, depolarizes the cell by allowing an inward flow of sodium and outward flow of potassium. In ischemic or traumatic brain cells, binding of glibenclamide to SUR1-TRPM4 reduces depolarization and, through a complex mechanism that is not yet fully understood, reduces blood-brain barrier (BBB) leakage and the formation of cerebral edema in both rodent models and humans.

A comprehensive review on glibenclamide in cerebral ischemia and stroke is available [25]. In addition to a detailed examination of preclinical work, that review also presents data from the ‘natural experiment’ wherein diabetic patients on a sulfonylurea drug present with stroke.

3.2. SUR1-TRPM4 in CNS disease

SUR1-TRPM4 is a unique ion channel discovered nearly two decades ago in single-channel patch-clamp experiments [26]. Since then, studies in molecular biology have characterized the molecular identity of the two-channel subunits [23,27], the biophysical and molecular properties of the channel [23,28], and some of the transcriptional mechanisms responsible for its de novo pathological upregulation [22,29]. Preclinical work in rodent models, performed by our group and by other independent groups, has implicated this channel in a surprising number of acute and chronic conditions of the CNS, including focal cerebral ischemia [22,30-33], global cerebral ischemia due to cardiac arrest [34-37], traumatic brain and spinal cord injury (TBI [38-43]; SCI [44-47]), subarachnoid, intracerebral and intraventricular hemorrhage (SAH [48,49]; ICH [50]; IVH [51]), cerebral edema due to metastatic tumors [52] and hepatic failure [53], hemorrhagic encephalopathy of prematurity [54], neuropathic pain due to peripheral nerve injury, experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE) [55-57], and EAE-associated optic neuritis. Channel blockade by glibenclamide or genetic deletion of SUR1 or TRPM4 in preclinical models of these conditions has been shown to be beneficial. Studies on human tissues have corroborated de novo channel upregulation in ischemic stroke [58,59], SAH [49], ICH [8], TBI [60-62], SCI [45] and multiple sclerosis (MS) [57] and, in TBI, have shown that CSF levels of SUR1 may serve as a biomarker of outcome [63].

4. Clinical development

4.1. Preclinical models

The role of SUR1-TRPM4 in some CNS disease models has been reviewed [64]. In ischemia and TBI, SUR1-TRPM4 has been linked to microvascular dysfunction that manifests as edema formation and delayed secondary hemorrhage. Also, since SUR1-TRPM4 is implicated in oncotic cell swelling and oncotic (necrotic) cell death [26], it is a major molecular mechanism of ‘accidental necrotic cell death’ in the CNS [65].

4.1.1. Animal models of stroke

Glibenclamide was first shown to reduce cerebral edema (excess tissue water) in a rodent model of LHI [22]. Subsequent work with different models of LHI confirmed that glibenclamide reduces ischemic brain swelling and its associated high mortality [31,32,66]. In rodent models of both fatal (malignant) and non-fatal stroke, reducing edema by treatment with glibenclamide is accompanied by improved neurological scores [31,32,66,67].

The therapeutic time window for glibenclamide depends on the outcome measure of interest. In models with moderate ischemic injury, the therapeutic time window for realizing a reduction in lesion volume was found to be 5.75–6 h [30]. In a rat reperfusion model with 4.5 h of ischemia, an unsalvageable ischemic injury, the therapeutic time window to realize a reduction in swelling was found to be 10 h [32]. This relatively long window for edema is believed to reflect the longer time required for its development, compared to neuronal death, coupled with the time required for transcriptional upregulation of SUR1-TRPM4 [29].

Given that intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is the only pharmacological treatment that is FDA-approved for acute ischemic stroke, it is paramount to ensure that there are no adverse interactions between rtPA and glibenclamide. In a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion, administration of glibenclamide along with high-dose rtPA at 6 h reduced hemispheric swelling by half and decreased hemorrhagic conversion, compared to rtPA alone [66]. The best neurological outcomes were observed in rats treated with both rtPA and glibenclamide, suggesting synergy. Recent work has elucidated a possible mechanism for this benefit, showing that glibenclamide inhibits the phasic secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) from NF-κB-activated endothelial cells [68].

4.1.2. Animal models of contusion-TBI

When head trauma results in a cerebral contusion, the hemorrhagic lesion often progresses during the first several hours after impact, either expanding or developing new, non-contiguous hemorrhagic lesions, a phenomenon termed hemorrhagic progression of a contusion (HPC). In animal models of contusion-TBI, a major effect of glibenclamide is to suppress contusion expansion. Blockade of SUR1 by glibenclamide or by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides significantly reduces the progression of brain contusions in treated animals, compared to vehicle [38,62]. Additional work by us [39] and by independent laboratories [40-43] has shown that in contusion-TBI, glibenclamide reduces hemorrhagic progression and edema, and improves neurological outcomes.

4.2. Clinical trials

4.2.1. Glibenclamide administration and pharmacokinetics

For the treatment of diabetes, glibenclamide is formulated as a pill for oral administration. Periodic (1–3 times daily) oral dosing results in plasma drug levels that are characterized by sharp, supratherapeutic peaks and long, subtherapeutic troughs. Peaks in plasma drug levels are associated with elevations in plasma insulin, which are therapeutic in diabetic patients, but risk hypoglycemia in non-diabetic patients. In patients with stroke, hypoglycemia can induce cerebral damage [69]. Also, when taken as an oral agent, variations in stomach pH affect the plasma level [70].

By contrast, an intravenous (IV) formulation of glibenclamide facilitates rapid achievement and stable maintenance of the desired plasma level of drug, without potentially harmful peaks, thus reducing the risk of hypoglycemia. An IV formulation of glibenclamide, called RP-1127 or Cirara, was developed by Remedy Pharmaceuticals. When the RP-1127 program was taken over by Biogen, RP-1127 was renamed BIIB093. This formulation of injectable glibenclamide (injectable Glyburide) is the one that has been used in all clinical trials reported to date [71-73], as well as in ongoing trials. Various publications reporting on clinical trials have referred to the drug as glibenclamide, Glyburide, RP-1127 or Cirara, but for simplicity and uniformity, below we refer to this IV preparation by its newest name, BIIB093.

In the published Phase 2 trials on LHI and TBI [71-73], BIIB093 was administered as a 0.13 mg bolus IV injection for the first 2 min, followed by an infusion of 0.16 mg/h for the first 6 h, then 0.11 mg/h for the remaining 66 h of the 72-h infusion.

In the GAMES-Pilot study, plasma levels of glibenclamide were 10–40 ng/mL. When dichotomized at the median concentration of 23 ng/mL, the average plasma glibenclamide concentration was 16 ± 4 ng/mL in the low-level group, and 31 ± 6 ng/mL in the high-level group [74]. Of note, the EC50 for glibenclamide blockade of SUR1-TRPM4 is 24 ng/mL (48 nM) at pH 7.4, and 3 ng/mL (6 nM) at pH 6.8 [22], with the latter being relevant due to the acidic pH of the ischemic brain [75].

4.2.2. Phase 2 clinical trials in LHI

Because SUR1-TRPM4 is critically involved in edema formation/brain swelling, which are uniquely dominant as causes of morbidity and mortality in LHI, the initial clinical studies on BIIB093 focused on LHI, rather than the broader indication of all strokes.

There have been two Phase 2 trials of BIIB093 in LHI, GAMES (Glyburide Advantage in Malignant Edema and Stroke)-Pilot, and GAMES-RP.

4.2.2.1. GAMES-Pilot.

GAMES-Pilot was an open-label, feasibility study of BIIB093 with no control subjects (). The study objective was to assess the feasibility of enrolling, evaluating, and treating with BIIB093 patients with severe anterior circulation ischemic stroke, regardless of whether they had been treated with standard-of-care IV rtPA.

Inclusion criteria were: subjects aged 18–80 years with acute anterior circulation ischemic stroke, with baseline diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) volume of 82–210 cm3, and with symptom onset within 10 h of the start of study drug infusion.

Results were reported in Sheth et al. [71]. The study enrolled 10 subjects, all of whom received BIIB093. The mean age was 50.5 years, and baseline DWI lesion volume was 102 ± 23 cm3. There were no serious adverse events related to drugs and no symptomatic hypoglycemia. The increase in ipsilateral hemisphere volume was 50 ± 33 cm3. The proportion of 90-day modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score ≤4 was 90% (40% mRS ≤3).

Subsequently, Sheth et al. [76] reported on an exploratory analysis that was carried out to compare clinical outcome data from GAMES-Pilot to historical-matched controls. Controls suffering LHI with the same DWI threshold used for enrollment into GAMES-Pilot were obtained from the EPITHET [77] and MMI-MRI [78] studies. To address imbalances, controls were selected using weighted Euclidean matching. After matching, GAMES-Pilot subjects showed similar baseline National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores, larger DWI volumes, and younger age. Outcome mRS scores of 0–4 were more frequent in the GAMES-Pilot patients (90% vs. 50%; P=0.049), with favorable trends in mRS 0–3 (40 vs. 25%; P=0.43) and in mortality (10 vs. 35%; P=0.21).

Kimberly et al. [74] reported on another exploratory analysis that was carried out to compare MRI measures of edema, and plasma levels of MMP-9, a marker of vasogenic edema [79], from GAMES-Pilot to a set of historical-matched controls. The neuroimaging control cohort consisted of placebo-treated subjects with large infarcts from the normobaric oxygen therapy in acute ischemic stroke trial. The control cohort for MMP-9 levels was derived from a prospectively collected biomarker repository. Cytotoxic and vasogenic edema were evaluated using fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) ratio and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) pseudonormalization on MRI. There were no differences between the control and BIIB093-treated subjects at 24 h, but the FLAIR ratio in the control group showed a rapid rise in values at 36 h, after which values plateaued. By contrast, the BIIB093-treated subjects showed a blunted rise in values that persisted 24 h after stroke onset. There was also a suggestion of a concentration-dependent effect on the FLAIR ratio in the BIIB093-treated subjects, i.e. greater blunting of the FLAIR ratio in subjects with the highest serum levels of drug. In addition, levels of plasma total MMP-9 at approximately 36 h after stroke onset were significantly less in BIIB093-treated subjects compared to controls.

4.2.2.2. GAMES-RP.

GAMES-RP was a randomized, multicentre, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of BIIB093 (). The primary objective was to demonstrate the efficacy of BIIB093 compared to placebo in subjects with a severe anterior circulation ischemic stroke who were likely to develop malignant edema.

Similar to GAMES-Pilot, inclusion criteria were: subjects aged 18–80 years with a clinical diagnosis of large anterior circulation hemispheric infarction confirmed by a baseline DWI lesion volume of 82–300 cm3, and with symptom onset within 10 h from the time last known to be neurologically healthy to the start of study drug infusion.

Eligible participants were randomly assigned to receive BIIB093 or placebo in a 1:1 ratio from a centralized, web-based randomization algorithm. Patients were screened by clinical teams at each site and enrolled by site study personnel. Minimization combined with biased coin was used to control for clinical site, age (≤60 years vs >60 years), and Alteplase treatment. The funder, principal investigators, site investigators, patients, imaging core, and outcomes personnel were masked to treatment. Drug vials, preparation bags, and tubing were identical in appearance for both treatment groups.

The primary efficacy outcome was the proportion of patients who achieved an mRS score of 0–4 at 90 days without undergoing decompressive craniectomy.

Results were reported in Sheth et al. [72]. The study enrolled 86 subjects who presented to 18 centers in the US. The per-protocol study population was 41 participants who received BIIB093 and 36 participants who received placebo. The mean DWI infarct volume was 160 ± 51 cm3, 50% larger than in the GAMES-Pilot study.

Of the 77 per-protocol participants, there was no difference between the BIIB093 and placebo groups in the proportion of participants with the primary clinical outcome, mRS 0–4 without decompressive craniectomy (41% vs. 39%; adjusted P = 0.77). In the shift analysis of mRS scores at 90 days, mRS scores were not significantly different between groups (P = 0.12). Compared with placebo, participants treated with BIIB093, with and without decompressive craniectomy, had similar mortality at 7 days, significantly reduced mortality at 30 days (P = 0.03), and non-significantly reduced mortality at 90 days (P = 0.06).

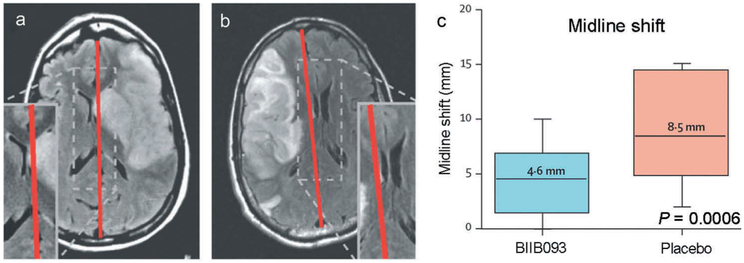

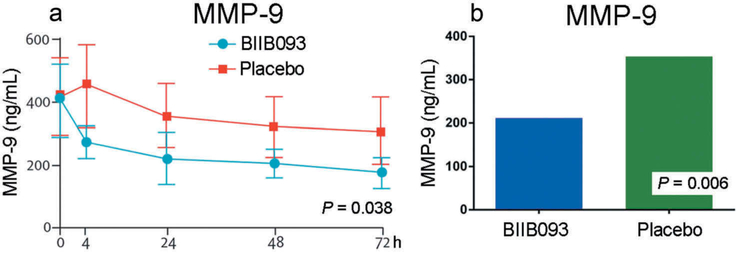

However, GAMES-RP did show promising results for measures of edema/swelling. The median midline shift at the level of the septum pellucidum at 72–96 h was 4.6 mm in the BIIB093 group vs. 8.5 mm in the placebo group (P = 0.0006) (Figure 1).The total plasma MMP-9 concentration measured at 24–72 h after initiation of the study drug infusion was lower in participants treated with BIIB093 compared with placebo (mean 211 ng/mL vs. 346 ng/mL; P = 0.006) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

BIIB093 reduces midline shift in LHI. (a and b): MRI of BIIB093-treated (a) and placebo-treated (b) subjects. (c) Midline shift in BIIB093-treated and placebo-treated subjects; adapted with permission from Sheth et al. [72].

Figure 2.

BIIB093 reduces plasma MMP-9 levels in LHI. (a and b) Plasma MMP-9 levels as a function of time (a) and overall levels (b) in BIIB093-treated and placebo-treated subjects; adapted with permission from Sheth et al. [72].

Subsequently, Kimberly et al. [80] reported on an analysis of prespecified outcomes from GAMES-RP that examined adjudicated, edema-related endpoints. Blinded adjudicators assigned designations for hemorrhagic transformation, neurologic deterioration, malignant edema, and edema-related deaths. In participants with malignant edema, the effects of treatment on additional markers of edema and clinical deterioration were examined. Treatment with BIIB093 was associated with a reduced proportion of deaths attributed to cerebral edema (n = 1 [2.4%] with BIIB093 vs. n = 8 [22.2%] with placebo; P = 0.01). In the subset of patients with malignant edema, those treated with BIIB093 had less midline shift (P < 0.01) and reduced MMP-9 levels (P < 0.01). The BIIB093 group had a lower rate of NIHSS increase of ≥4 during the infusion period (n = 7 [37%] in BIIB093 vs. n = 12 [71%] in placebo; P = 0.043), and of change in the level of alertness (NIHSS subscore 1a; n = 11 [58%] vs. n = 15 [94%]; P = 0.016).

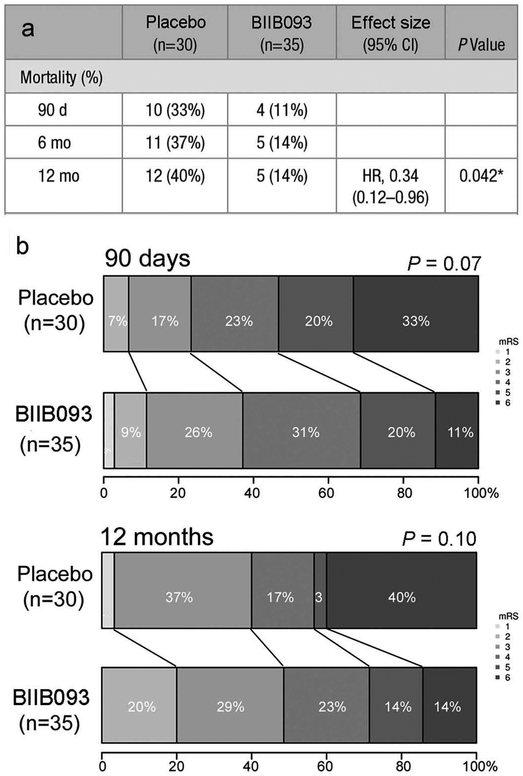

Sheth et al. [81] reported on a post-hoc exploratory analysis of GAMES-RP data for subjects ≤70 years of age. Midline shift, mortality, functional outcomes, disability, and quality of life were compared in participants aged ≤70 years treated with BIIB093 (n = 35) vs. placebo (n = 30) who met per-protocol criteria. Participants ≤70 years of age treated with BIIB093 had lower mortality at all time points (log-rank for survival hazards ratio, 0.34; P = 0.04) (Figure 3). After adjustment for age, the difference in functional outcome (mRS) demonstrated a trend toward benefit for BIIB093-treated subjects at 90 days (odds ratio, 2.31; P = 0.07) (Figure 3). Repeated measures analysis at 90 days, 6 months and 12 months showed a significant treatment effect of BIIB093 on the Barthel Index (P = 0.03) and EuroQol group 5-dimension (P = 0.05). Participants treated with BIIB093 had lower plasma levels of MMP-9 (189 vs. 376 ng/mL; P < 0.001) and decreased midline shift (4.7 vs. 9 mm; P < 0.001) compared with participants who received placebo.

Figure 3.

BIIB093 significantly improves mortality and trends toward improving functional outcome (mRS) in subjects <70 years of age with LHI. (a) Mortality at 3, 6 and 12 months in BIIB093-treated and placebo-treated subjects. (b) mRS shift at 3 and 12 months in BIIB093-treated and placebo-treated subjects; adapted from Sheth et al. [81].

Vorasayan et al. [82] reported on another post-hoc exploratory analysis of GAMES-RP data that was carried out to examine lesional water uptake. Non-contrast CT scans performed between admission and day 7 (n = 264) were analyzed in the GAMES-RP modified intention-to-treat sample. Quantitative change in CT radiodensity, which reflect net water uptake [NWU], and midline shift were measured. In a repeated-measures regression model, greater NWU was associated with increased midline shift (β = 0.23, 95% CI 0.20–0.26; P < 0.001). Treatment with BIIB093 was associated with reduced NWU (β = −2.80, 95% CI −5.07 to −0.53; P = 0.016) and reduced midline shift (β = −1.50, 95% CI −2.71 to −0.28; P = 0.016). Treatment with BIIB093 reduced both grey and white matter water uptake. In mediation analysis, grey matter NWU (β = 0.15, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.20: P< 0.001) contributed to a greater proportion of midline shift mass effect, as compared to white matter NWU (β = 0.08, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.13; P = 0.001).

4.2.3. Phase 3 clinical trial in LHI

4.2.3.1. CHARM.

The GAMES-RP trial did not meet its primary efficacy outcome. Nevertheless, as reviewed above, favorable data emerged not only from the primary study and from the prespecified analysis of edema-related endpoints, but also from two post-hoc analyses, one on subjects <70 years and the other on CT-based net water uptake. Caution is required with post-hoc analyses, but the number of subjects excluded for not being <70 years was small, and group balance remained favorable. Overall, the series of studies based on GAMES-RP showed significant benefit regarding midline shift, plasma MMP-9 levels, CT evidence of decrease net water uptake, and adjudicated outcomes related to brain swelling. In addition, favorable trends were evident on functional outcomes and survival, especially in subjects ≤70 years of age. Together, these data served as the impetus for further study of BIIB093 in LHI.

CHARM (Cirara in large Hemispheric infarction Analyzing modified Rankin and Mortality) is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter, Phase 3 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BIIB093 for severe cerebral edema following LHI (). CHARM, which will enroll 680 subjects world-wide, currently is ongoing, and is sponsored by Biogen.

Compared to GAMES-RP, in CHARM, LHI has a somewhat broader definition. LHI is defined as DWI or computed tomography perfusion (CTP) lesion volume of 80–300 cm3, or an Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) of 1–5 with involvement of at least 2 defined cortical regions. Participants will be enrolled who receive mechanical thrombectomy, provided that the post-thrombectomy DWI lesion volume fits with the stated inclusion criteria. As with GAMES-RP, infusion of study treatment must begin within 10 h of the time of symptom onset, if known, or the time last known normal.

The primary objective of CHARM is to determine if BIIB093 increases the proportion at Day 90 of participants with LHI with improvement in functional outcome as measured by the mRS, when compared with placebo. The secondary objectives are to evaluate the safety and tolerability of BIIB093 in participants with LHI, to determine if BIIB093 improves overall survival at Day 90, improves functional outcome at Day 90 on the mRS dichotomized 0–4 vs. 5–6, and reduces midline shift at 72 h.

4.2.4. Phase 2 clinical trials in TBI

4.2.4.1. Completed phase 2 clinical trial in TBI.

A small Phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial was carried out to assess the safety and efficacy of BIIB093 in subjects with TBI (). The primary efficacy objective was to assess whether patients with severe, moderate, or complicated-mild TBI administered BIIB093 would show a decrease in MRI-defined edema and/or hemorrhage, compared to patients administered placebo.

Results were reported in Eisenberg et al. [73]. Of 28 subjects randomized, 25 had Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores of 6–10, and 14 had contusions. The MRI percent change at 72–168 h from screening/baseline was compared between the BIIB093 and placebo groups. Analysis of contusions (7 per group) showed that lesion volumes (hemorrhage plus edema) increased 1036% with placebo vs. 136% with BIIB093 (P = 0.15), and that hemorrhage volumes increased 11.6% with placebo but decreased 29.6% with BIIB093 (P = 0.62). The lack of statistical significance in these measures, despite the large group differences, reflects not only the very small group sizes, but also the heterogeneity of the contusions in these subjects.

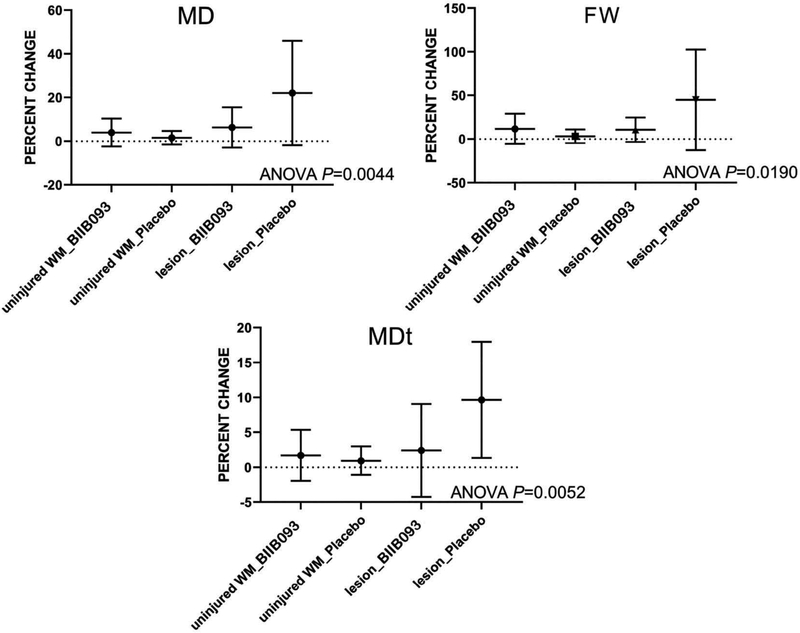

Three diffusion MRI measures of edema were quantified: mean diffusivity (MD), free water (FW), and tissue MD (MDt), corresponding to overall, extracellular and intracellular water, respectively. The percent change with time for each measure was compared in contusions (n = 14) vs. uninjured white matter (n = 24) in subjects receiving placebo (n = 20) or BIIB093 (n = 18). For placebo, the percent change for all 3 measures in contusions was significantly different compared to uninjured white matter (ANOVA, P < 0.02), consistent with worsening of edema in untreated contusions (Figure 4). By contrast, for BIIB093, the percent change for all 3 measures in contusions was not significantly different compared to uninjured white matter.

Figure 4.

BIIB093 reduces MRI measures of edema in contusion-TBI. Percent changes in mean diffusivity (MD), free water (FW), and tissue MD (MDt), corresponding to overall, extracellular and intracellular water, respectively, were compared in uninjured white matter (WM) and in lesions for the two treatment arms. For each measure of edema, comparing the two placebo arms, there was a significant difference between uninjured white matter and lesions, whereas comparing the two BIIB093 arms, there was no significant difference between uninjured white matter and lesions; adapted from Eisenberg et al. [73].

4.2.4.2. ASTRAL.

Whereas the aforementioned MRI study in TBI enrolled both non-contused and contused patients, ASTRAL (Antagonizing SUR1-TRPM4 to Reduce the progression of intracerebral hematoma And edema surrounding Lesions) is enrolling only patients with contusion-TBI. The rationale for this rests in part on the preclinical data, as reviewed above, in which glibenclamide was studied almost exclusively in models of contusion-TBI, and in the aforementioned MRI study in TBI, in which effects of BIIB093 were most evident in contusions. In addition, in contusion-TBI models, a major effect of glibenclamide is to suppress contusion expansion, i.e. ‘hemorrhagic progression of contusion’.

ASTRAL is a multicenter, double-blind, multidose, placebo-controlled, randomized, parallel-group, Phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BIIB093 for patients with brain contusion (). ASTRAL, which will enroll 160 subjects in North America, Europe, and Japan, currently is ongoing, and is sponsored by Biogen.

ASTRAL is enrolling patients with a clinical diagnosis of contusion-TBI, with lesions within the supratentorial brain parenchyma totaling >3 mL in volume on baseline non-contrast CT scan, who have a baseline GCS score of 5–14. Unlike other clinical trials with BIIB093, ASTRAL will utilize a treatment window of 6.5 h, instead of 10 h, which reflects the goal of targeting not only edema but hemorrhagic progression of contusion, which occurs more rapidly [38]. Also unlike other clinical trials with BIIB093, ASTRAL will study two doses of BIIB093, 3 and 5 mg/day, each with its own placebo control; thus 4 groups of 40 subjects will be studied.

The primary objective is to determine if BIIB093 reduces brain contusion expansion by Hour 96 when compared to placebo. The secondary objectives are to evaluate the effects of BIIB093 on acute neurologic status, functional outcomes, and treatment requirements, to further differentiate the mechanism of action of BIIB093 on contusion expansion by examining differential effects on hematoma and edema expansion, and to determine if BIIB093 improves survival at Day 90 when compared to placebo.

4.2.5. Safety and tolerability

In the published Phase 2 trials on LHI and TBI [71-73], BIIB093, at a dose of ~3 mg/day infused IV over 72 h, was well tolerated. There were no differences in severe adverse events between BIIB093 and placebo groups.

The principal adverse event reported was hypoglycemia (<55 mg/dL), which occurred infrequently, and typically was easily managed with IV dextrose. In GAMES-RP, no episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia were reported, and all low glucose levels resolved after implementation of the prespecified hypoglycemia protocol. A similar finding was made in the TBI trial, with no symptomatic hypoglycemia, and no case requiring cessation of drug infusion.

In GAMES-RP, the proportion of patients with cardiac adverse events and cardiac serious adverse events was similar in the BIIB093 and placebo groups. No clinically meaningful differences in vital signs or other laboratory variables were recorded between the active treatment and the control groups.

The low incidence of hypoglycemia observed in these trials may be due, in part, to the relatively low doses of BIIB093 that are required for a beneficial effect in the injured CNS. Glibenclamide does not normally accumulate in the healthy brain [83]. However, blood-brain barrier (BBB) compromise, combined with the low pH of injured brain, promotes uptake of glibenclamide, a weak acid, into the injured brain [25].

5. Conclusion

Unforeseen shortcomings are evident in some aspects of the design of the Phase 2 trials on BIIB093. In GAMES-RP, the primary outcome included avoidance of decompressive craniectomy, which in retrospect was problematic. Evidence indicates that decompressive craniectomy was not uniformly applied across sites and that decompressive craniectomy was implemented in the absence of neurological deterioration more frequently in the BIIB093 group compared to the placebo group [72], thereby potentially confounding the prespecified primary outcome. In the MRI study in TBI, enrollment required a baseline MRI, which often was not feasible in patients with complex traumatic injuries, thus critically limiting enrollment. In addition, both GAMES-RP and the MRI study in TBI were terminated early, due to funding limitations. In both cases, fewer subjects were enrolled than initially anticipated, resulting in a reduction in statistical power.

Despite these shortcomings, important treatment effects of BIIB093 were observed in patients with LHI and TBI. In TBI, favorable observations currently are limited to MRI measures of edema in a very small cohort of seven patients. However, in LHI, robust effects of drug were observed on objective biological variables including midline shift, plasma MMP-9 levels, and net water uptake. Positive effects on objective biological variables translated directly into benefits in adjudicated edema-related endpoints, including the improved level of alertness, better NIHSS, and fewer deaths attributable to edema. In the overall GAMES-RP cohort, and more so in subjects <70 years of age, statistically significant or strong trends in various functional outcomes (mRS, Barthel Index, EuroQol) and in mortality were observed, providing evidence that BIIB093 may be an effective treatment in LHI.

6. Expert opinion

6.1. Improvement over other therapies

Brain swelling is an ominous consequence of LHI, contusion-TBI and several other CNS pathologies, and often leads to neurological worsening and death. Available pharmacological therapies for brain swelling are limited to osmotherapies and corticosteroids, which are inadequate and largely unproven. Developing new therapies for patients with LHI is especially important, given the rising stroke rates in young adults [84], who are at higher risk for malignant MCA infarcts. BIIB093 holds the promise of substantially improving the management of patients with a variety of CNS pathologies in which swelling leads to neurological decline and death.

6.2. Impact on current treatment strategies

At present, the only proven treatment for severe brain swelling is decompressive craniectomy, which has significant drawbacks. BIIB093 holds the promise of reducing the need for decompressive craniectomy in multiple patient populations at risk for severe brain swelling.

6.3. Likelihood of physicians prescribing the drug

Given the morbidity and mortality associated with severe brain swelling, the near-total absence of alternatives, and its relatively benign adverse effect profile, it is likely that physicians will embrace BIIB093 for managing patients at risk for brain swelling. Currently available per os preparations of glibenclamide predispose non-diabetic patients to hypoglycemia, an adverse event that is less likely with the IV formulation, BIIB093.

6.4. Data still needed

Ongoing studies, especially CHARM, must be completed prior to FDA approval of BIIB093 in LHI.

6.5. Where the drug is likely to be in 5 years

Within a few years, ongoing and anticipated clinical trials hopefully will have demonstrated the benefit of administering BIIB093 to patients with LHI, contusion-TBI and other CNS conditions associated with brain swelling.

Article highlights.

Edema-associated brain swelling is a major cause of neurological deterioration and death in patients with large hemispheric infarction (LHI), severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) and other CNS conditions.

The only proven treatment for severe brain swelling is decompressive craniectomy but this procedure has significant drawbacks.

SUR1-TRPM4 channels play a critical role in edema formation and brain swelling in LHI and TBI.

Emerging clinical data show that SUR1-TRPM4 inhibitor BIIB093 may transform the management of patients with LHI and contusion-TBI.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This paper was not funded. N Badjatia is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (R01NS105503). WT Kimberly is supported by grants from NINDS (R01NS099209) and AHA (AHA 17CSA 33550004). KN Sheth is supported by grants from NINDS (U01NS106513; U24NS107136; U24NS107215; R03NS112859; R01NR018335). JM Simard is supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (I01BX002889), the Department of Defense (SCI170199), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL082517) and the NINDS (R01NS060801; R01NS102589; R01NS105633).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

WT Kimberly and KN Sheth received grants from Remedy Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of GAMES-Pilot and GAMES-RP, and also receive research grants from Biogen. JM Simard holds a US patent (7,285,574), ‘A novel non-selective cation channel in neural cells and methods for treating brain swelling.’ JM Simard is a member of the Board of Directors and holds shares in Remedy Pharmaceuticals and is a paid consultant for Biogen. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers.

- 1.Heinsius T, Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G. Large infarcts in the middle cerebral artery territory. Etiology and outcome patterns. Neurology. 1998;50(2):341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacke W, Schwab S, Horn M, et al. ‘Malignant’ middle cerebral artery territory infarction: clinical course and prognostic signs. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(4):309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasner SE, Demchuk AM, Berrouschot J, et al. Predictors of fatal brain edema in massive hemispheric ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(9):2117–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee D, Patil CG. Epidemiology and the global burden of stroke. World Neurosurg. 2011;76(6 Suppl):S85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iaccarino C, Carretta A, Nicolosi F, et al. Epidemiology of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg Sci. 2018;62(5):535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths – United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(9):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donkin JJ, Vink R. Mechanisms of cerebral edema in traumatic brain injury: therapeutic developments. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23 (3):293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urday S, Kimberly WT, Beslow LA, et al. Targeting secondary injury in intracerebral haemorrhage–perihaematomal oedema. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(2):111–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayman EG, Wessell A, Gerzanich V, et al. Mechanisms of global cerebral edema formation in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2017;26(2):301–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth P, Wick W, Weller M. Steroids in neurooncology: actions, indications, side-effects. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(6):597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bemeur C, Cudalbu C, Dam G, et al. Brain edema: a valid endpoint for measuring hepatic encephalopathy?. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31 (6):1249–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kampondeni SD, Birbeck GL, Seydel KB, et al. Noninvasive measures of brain edema predict outcome in pediatric cerebral malaria. Surg Neurol Int. 2018;9(53). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wijdicks EF, Sheth KN, Carter BS, et al. Recommendations for the management of cerebral and cerebellar infarction with swelling: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2014;45(4):1222–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurland DB, Khaladj-Ghom A, Stokum JA, et al. Complications associated with decompressive craniectomy: a systematic review. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23(2):292–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das S, Mitchell P, Ross N, et al. Decompressive hemicraniectomy in the treatment of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction: a meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsaousi GG, Marocchi L, Sergi PG, et al. Early and late clinical outcomes after decompressive craniectomy for traumatic refractory intracranial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidence. J Neurosurg Sci 2018. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battey TW, Karki M, Singhal AB, et al. Brain edema predicts outcome after nonlacunar ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45 (12):3643–3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marble A. Glibenclamide, a new sulphonylurea: whither oral hypoglycaemic agents? Drugs. 1971;1(2):109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seino S Physiology and pathophysiology of K(ATP) channels in the pancreas and cardiovascular system: a review. J Diabetes Complications. 2003;17(2 Suppl):2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tinker A, Aziz Q, Li Y, et al. Atp-sensitive potassium channels and their physiological and pathophysiological roles. Compr Physiol. 2018;8(4):1463–1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szeto V, Chen NH, Sun HS, et al. The role of K ATP channels in cerebral ischemic stroke and diabetes. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39 (5):683–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simard JM, Chen M, Tarasov KV, et al. Newly expressed SUR1-regulated NC(Ca-ATP) channel mediates cerebral edema after ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12(4):433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woo SK, Kwon MS, Ivanov A, et al. The sulfonylurea receptor 1 (sur1)-transient receptor potential melastatin 4 (trpm4) channel. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(5):3655–3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang G, Lin X, Zhang S, et al. A protective role of glibenclamide in inflammation-associated injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2017;2017:3578702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simard JM, Sheth KN, Kimberly WT, et al. Glibenclamide in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Neurocrit Care. 2014;20(2):319–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen M, Simard JM. Cell swelling and a nonselective cation channel regulated by internal Ca2+ and ATP in native reactive astrocytes from adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 2001;21(17):6512–6521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen M, Dong Y, Simard JM. Functional coupling between sulfonylurea receptor type 1 and a nonselective cation channel in reactive astrocytes from adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 2003;23 (24):8568–8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo SK, Kwon MS, Ivanov A, et al. Complex n-glycosylation stabilizes surface expression of transient receptor potential melastatin 4b protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(51):36409–36417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo SK, Kwon MS, Geng Z, et al. Sequential activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and specificity protein 1 is required for hypoxia-induced transcriptional stimulation of abcc8. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(3):525–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simard JM, Yurovsky V, Tsymbalyuk N, et al. Protective effect of delayed treatment with low-dose glibenclamide in three models of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(2):604–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simard JM, Tsymbalyuk N, Tsymbalyuk O, et al. Glibenclamide is superior to decompressive craniectomy in a rat model of malignant stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(3):531–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simard JM, Woo SK, Tsymbalyuk N, et al. Glibenclamide-10-h treatment window in a clinically relevant model of stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2012;3(2):286–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wali B, Ishrat T, Atif F, et al. Glibenclamide administration attenuates infarct volume, hemispheric swelling, and functional impairments following permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke Res Treat. 2012;2012:460909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang K, Gu Y, Hu Y, et al. Glibenclamide improves survival and neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest in rats. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):e341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang K, Wang Z, Gu Y, et al. Glibenclamide is comparable to target temperature management in improving survival and neurological outcome after asphyxial cardiac arrest in rats. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(7):e003465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang K, Wang Z, Gu Y, et al. Glibenclamide prevents water diffusion abnormality in the brain after cardiac arrest in rats. Neurocrit Care. 2018;29(1):128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakayama S, Taguchi N, Isaka Y, et al. Glibenclamide and therapeutic hypothermia have comparable effect on attenuating global cerebral edema following experimental cardiac arrest. Neurocrit Care. 2018;29(1):119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simard JM, Kilbourne M, Tsymbalyuk O, et al. Key role of sulfonylurea receptor 1 in progressive secondary hemorrhage after brain contusion. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(12):2257–2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel AD, Gerzanich V, Geng Z, et al. Glibenclamide reduces hippocampal injury and preserves rapid spatial learning in a model of traumatic brain injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69(12):1177–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zweckberger K, Hackenberg K, Jung CS, et al. Glibenclamide reduces secondary brain damage after experimental traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2014;272:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu ZM, Yuan F, Liu YL, et al. Glibenclamide attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in adult mice after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(4):925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jha RM, Molyneaux BJ, Jackson TC, et al. Glibenclamide produces region-dependent effects on cerebral edema in a combined injury model of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(17):2125–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kochanek PM, Bramlett HM, Dixon CE, et al. Operation brain trauma therapy: 2016 update. Mil Med. 2018;183(suppl_1):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simard JM, Tsymbalyuk O, Ivanov A, et al. Endothelial sulfonylurea receptor 1-regulated NC Ca-ATP channels mediate progressive hemorrhagic necrosis following spinal cord injury. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2105–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simard JM, Woo SK, Norenberg MD, et al. Brief suppression of abcc8 prevents autodestruction of spinal cord after trauma. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(28):28ra29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simard JM, Popovich PG, Tsymbalyuk O, et al. Spinal cord injury with unilateral versus bilateral primary hemorrhage–effects of glibenclamide. Exp Neurol. 2012;233(2):829–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hosier H, Peterson D, Tsymbalyuk O, et al. A direct comparison of three clinically relevant treatments in a rat model of cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(21):1633–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simard JM, Geng Z, Woo SK, et al. Glibenclamide reduces inflammation, vasogenic edema, and caspase-3 activation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(2):317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tosun C, Kurland DB, Mehta R, et al. Inhibition of the sur1-trpm4 channel reduces neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44(12):3522–3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang B, Li L, Chen Q, et al. Role of glibenclamide in brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2017;8(2):183–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simard PF, Tosun C, Melnichenko L, et al. Inflammation of the choroid plexus and ependymal layer of the ventricle following intraventricular hemorrhage. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2(2):227–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson EM, Pishko GL, Muldoon LL, et al. Inhibition of sur1 decreases the vascular permeability of cerebral metastases. Neoplasia. 2013;15(5):535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jayakumar AR, Valdes V, Tong XY, et al. Sulfonylurea receptor 1 contributes to the astrocyte swelling and brain edema in acute liver failure. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5(1):28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tosun C, Koltz MT, Kurland DB, et al. The protective effect of glibenclamide in a model of hemorrhagic encephalopathy of prematurity. Brain Sci. 2013;3(1):215–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schattling B, Steinbach K, Thies E, et al. Trpm4 cation channel mediates axonal and neuronal degeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2012;18(12):1805–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makar TK, Gerzanich V, Nimmagadda VK, et al. Silencing of abcc8 or inhibition of newly upregulated sur1-trpm4 reduce inflammation and disease progression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gerzanich V, Makar TK, Guda PR, et al. Salutary effects of glibenclamide during the chronic phase of murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mehta RI, Ivanova S, Tosun C, et al. Sulfonylurea receptor 1 expression in human cerebral infarcts. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72 (9):871–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mehta RI, Tosun C, Ivanova S, et al. Sur1-trpm4 cation channel expression in human cerebral infarcts. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74(8):835–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martinez-Valverde T, Vidal-Jorge M, Martinez-Saez E, et al. Sulfonylurea receptor 1 in humans with post-traumatic brain contusions. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32(19):1478–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castro L, Noelia M, Vidal-Jorge M, et al. Kir6.2, the pore-forming subunit of ATP-sensitive k(+) channels, is overexpressed in human posttraumatic brain contusions. J Neurotrauma. 2018;36:165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gerzanich V, Stokum JA, Ivanova S, et al. Sulfonylurea receptor 1, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily m member 4, and kir6.2: role in hemorrhagic progression of contusion. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(7):1060–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jha RM, Puccio AM, Chou SH, et al. Sulfonylurea receptor-1: a novel biomarker for cerebral edema in severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):e255–e264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simard JM, Woo SK, Schwartzbauer GT, et al. Sulfonylurea receptor 1 in central nervous system injury: a focused review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(9):1699–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simard JM, Woo SK, Gerzanich V. Transient receptor potential melastatin 4 and cell death. Pflugers Arch. 2012;464(6):573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simard JM, Geng Z, Silver FL, et al. Does inhibiting sur1 complement rt-pa in cerebral ischemia? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1268:95–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wali B, Ishrat T, Atif F, et al. Glibenclamide administration attenuates infarct volume, hemispheric swelling, and functional impairments following permanent focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke Res Treat. 2012;2012:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gerzanich V, Kwon MS, Woo SK, et al. Sur1-trpm4 channel activation and phasic secretion of mmp-9 induced by tpa in brain endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radermecker RP, Scheen AJ. Management of blood glucose in patients with stroke. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36:S94–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.King ZA, Sheth KN, Kimberly WT, et al. Profile of intravenous glyburide for the prevention of cerebral edema following large hemispheric infarction: evidence to date. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:2539–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheth KN, Kimberly WT, Elm JJ, et al. Pilot study of intravenous glyburide in patients with a large ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(1):281–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheth KN, Elm JJ, Molyneaux BJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenous glyburide on brain swelling after large hemispheric infarction (games-RP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(11):1160–1169.••Key study

- 73.Eisenberg HM, Shenton ME, Pasternak O, et al. An MRI pilot study of intravenous glyburide in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019. Epub ahead of print.••Key study

- 74.Kimberly WT, Battey TW, Pham L, et al. Glyburide is associated with attenuated vasogenic edema in stroke patients. Neurocrit Care. 2014;20(2):193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nedergaard M, Kraig RP, Tanabe J, et al. Dynamics of interstitial and intracellular pH in evolving brain infarct. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(3 Pt 2):R581–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sheth KN, Kimberly WT, Elm JJ, et al. Exploratory analysis of glyburide as a novel therapy for preventing brain swelling. Neurocrit Care. 2014;21(1):43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davis SM, Donnan GA, Parsons MW, et al. Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the echoplanar imaging thrombolytic evaluation trial (epithet): a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomalla G, Hartmann F, Juettler E, et al. Prediction of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction by magnetic resonance imaging within 6 hours of symptom onset: a prospective multicenter observational study. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Montaner J, Alvarez-Sabin J, Molina C, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase expression after human cardioembolic stroke: temporal profile and relation to neurological impairment. Stroke. 2001;32(8):1759–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kimberly WT, Bevers MB, von Kummer R, et al. Effect of iv glyburide on adjudicated edema endpoints in the games-RP trial. Neurology. 2018;91(23):e2163–e2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sheth KN, Petersen NH, Cheung K, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients aged</=70 years with intravenous glyburide from the phase ii games-RP study of large hemispheric infarction: an exploratory analysis. Stroke. 2018;49(6):1457–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vorasayan P, Bevers MB, Beslow LA, et al. Intravenous glibenclamide reduces lesional water uptake in large hemispheric infarction. Stroke. 2019. in press.••Key study

- 83.Lahmann C, Kramer HB, Ashcroft FM. Systemic administration of glibenclamide fails to achieve therapeutic levels in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of rodents. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ekker MS, Verhoeven JI, Vaartjes I, et al. Stroke incidence in young adults according to age, subtype, sex, and time trends. Neurology. 2019;92(21):e2444–e2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]