Abstract

Objectives

It is well-known that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among firefighters contributes to their job-related stress. However, the relationship between burnout and PTSD in firefighters has rarely been studied. This study therefore explored the association between burnout and its related factors, such as trauma and violence, and PTSD symptoms among firefighters in Korea.

Methods

A total of 535 firefighters participated in the Firefighter Research on Enhancement of Safety & Health study at 3 university hospitals from 2016 to 2017. The 535 participants received a baseline health examination, including questionnaires assessing their mental health. A Web-based survey was also conducted to collect data on job-related stress, history of exposure to violence, burnout, and trauma experience. The associations among burnout, its related factors, and PTSD symptoms were investigated using structural equation modeling.

Results

Job demands (β=0.411, p<0.001) and effort-reward balance (β=-0.290, p<0.001) were significantly related to burnout. Burnout (β=0.237, p<0.001) and violence (β=0.123, p=0.014) were significantly related to PTSD risk. Trauma (β=0.131, p=0.001) was significantly related to burnout; however, trauma was not directly associated with PTSD scores (β=0.085, p=0.081).

Conclusions

Our results show that burnout and psychological, sexual, and physical violence at the hands of clients directly affected participants’ PTSD symptoms. Burnout mediated the relationship between trauma experience and PTSD.

Keywords: Firefighters, Psychological burnout, Post-traumatic stress disorders, Occupational stress

INTRODUCTION

It is well-known that firefighters are exposed to hazardous environments that can cause both physical harm and psychological trauma [1,2]. They also experience chronic stress due to sleep disturbances caused by shift work and sustained tension caused by atmospheric working conditions [3]. These physical factors and the associated job stress decrease firefighters’ quality of life and can lead to long-term mental and physical harm [4-6]. Among firefighters, work-related characteristics are considered to be risk factors for respiratory, cardiovascular, and psychiatric disorders [5-7].

Burnout is characterized by chronic emotional exhaustion, interpersonal cynicism, loss of personal identity, and personal and professional ineffectiveness [8-10]. Although burnout is not a medical diagnosis, it can cause adverse physical and psychological effects [11]. Recently, several studies have reported burnout to be prominent among emotional laborers [12], those engaging in dangerous or specialized work, those with high expectations to perform socially moral work, such as nurses and doctors [13,14], and those who have jobs that require a high level of responsibility [15]. A longitudinal study of ambulance workers showed that job-related acute stress was associated with fatigue, burnout, and post-traumatic distress [16].

Persistent and chronic occupational stress and burnout are considered predictors of post-traumatic stress [17,18]. Several studies conducted to identify the association between emotional exhaustion and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused by excessive work stress have showed a strong positive correlation between burnout and PTSD [19-21]. Based on the results of these studies, we hypothesized that chronic stress-related burnout could be a risk factor for PTSD, and we attempted to analyze the mutual interrelationships among burnout, PTSD, and other factors that may affect PTSD.

Until recently, relatively few studies have examined the association between burnout and firefighters’ mental health in Korea [22]. Therefore, we investigated the association between burnout due to work-related stress and the risk of PTSD in firefighters. We also explored both the direct and indirect effects of burnout, trauma, and violence on PTSD risk.

In order to confirm the relevant factors of PTSD identified in previous studies conducted among firefighters and to describe the association among the factors in an integrated way, we analyzed the data using structural equation modeling. Based on these findings, we discuss whether experiencing burnout due to work-related stress is a direct or indirect factor influencing PTSD.

METHODS

Study Population

Over 1000 firefighters participated in the Firefighter Research on Enhancement of Safety & Health (FRESH) study, which consisted of 2 parts. First, a dynamic cohort of 1022 firefighters completed questionnaires and underwent screening for cardiovascular and mental health issues either once or twice between 2016 and 2019. Second, these firefighters completed a Web survey to gather information concerning job-related factors and their health status, such as quality of life, presenteeism, social psychological health status, and health behavior. Data were collected from subjects for whom the interval between the 2 surveys was within 6 months (mean, 6.91 days; standard deviation [SD], 73.72).

In this study, we included data from 606 firefighters who completed both the baseline health examination and the Web-based survey. Participants (n=65) with the lowest scores across all mental health examination items (17 for PTSD, 20 for depression, and 21 for anxiety disorders) in the cohort examination were excluded from the analysis to increase the accuracy of the latent variable measurement through factor analysis. After excluding 6 participants with missing information regarding job-related stress (n=1) or PTSD (n=5), the data from 535 firefighters were analyzed.

Survey Instrument

The Web-based survey included questionnaires on basic demographic information (e.g., sex, age, marital status, educational level, and smoking and drinking habits), occupational history (e.g., service experience, rank, main job, and work area), history of exposure to physical and psychological violence, chronic stress factors, shifts, and emotional labor. The Job Content Questionnaire [23], the 12-item General Health Questionnaire [24], and questionnaires addressing organizational climate, emotional demands, trauma experience, and burnout were also included. The analysis was conducted using data related to job-related chronic stress, burnout, exposure to violence, and trauma experience.

Specialized cohorts were primarily subjected to clinical tests to check for cardiovascular disease, cognitive dysfunction, and mental health diseases. The clinical tests included physical measurements, laboratory testing, a cardiovascular examination, a cognitive function test, and a mental health examination. Among these tests of mental health, PTSD was measured using the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder for DSM-5 Checklist (PCL-C) [25], sleep disorders were measured using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, alcohol dependency was measured using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Korea, depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and anxiety disorder was measured using the Beck Anxiety Inventory. The PCL-C score was used in this study.

Job stress was measured with a tool that modified and supplemented the Korean Occupational Stress Scale, which was developed by Chang et al. [26] for Korean employees. In this study, 6 questions across 2 categories—3 for “job demands” and 3 for “effort-reward imbalance (ERI)”—were used (Table 1). Cron bach’s α was 0.754 and 0.791 for the 2 categories, respectively.

Table 1.

Factors used in the final analysis model and Web survey items for each factor

| Factors | Variable | Survey item |

|---|---|---|

| Job demand | S1 | Due to having many things to do, I always feel time pressure |

| S2 | My job has become increasingly overloading | |

| S3 | I have to do various jobs simultaneously | |

| ERI | S4 | I acquire respect and confidence from my company |

| S5 | I believe that I will be given more rewards from my company if I work hard | |

| S6 | I am provided with opportunities to develop my capacity | |

| Burnout | B1 | I feel exhausted by my work |

| B2 | By the end of business hours, I feel out of shape | |

| B3 | I feel tired when I think about getting up in the morning and going to work | |

| B4 | Working all day is stressful for me | |

| B5 | I feel burned out by my work | |

| Trauma | T1 | I have experienced terrible accidents and deaths of the victims involved in tragic incidents |

| T2 | I have told survivors the news of a tragic incident | |

| T3 | I have experienced situations in which I could not save lives | |

| T4 | I have experienced terrible trauma or child death | |

| T5 | I have experienced a major disaster or a major life-death event | |

| Violence | V1 | I have heard insulting comments or curses that are offensive to clients in the process of performing my duties |

| V2 | I have experienced unwanted sexual contact or sexual harassment with my clients in the process of doing my job | |

| V3 | I have been bullied by a client in the process of performing my duties | |

| V4 | I have been discriminated against by customers on the basis of position, sex, or age in the process of performing my duties | |

| V5 | I have been physically assaulted by a client (for instance, a beating) in the process of performing my duties |

ERI, effort-reward imbalance.

Burnout and trauma experience were measured using 5 and 6 questions, with a 7-point Likert scale and 5-point Likert scale, respectively (Table 1). Cronbach’s α was 0.941 and 0.876 for the 2 categories, respectively. Higher scores indicate higher levels for both burnout and trauma.

Violence was measured using the Korean Workplace Violence Scale [27]. Of the items, 5 questions about experiences of psychological, sexual, and physical violence at the hands of clients were analyzed. Responses were rated on a 4-point Lik ert scale, with higher scores indicating higher exposure to vio lence (Table 1). Cronbach’s α was determined to be 0.842.

PTSD was measured using the PCL-C, which consists of 17 questions. Items 1-5 concern re-experience, 6-12 are related to avoidance, and 13-17 are related to arousal. Cronbach’s α was determined to be 0.892.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, the following statistical procedures were conducted. First, to evaluate the validity and reliability of the latent constructs and to determine the factors in the final analysis model, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using participants’ responses regarding job stress, burnout, exposure to violence, and experience with trauma. In order to assess the validity of the potential factors to be measured, the standardized factor loadings of the measured variables and the average variance extracted (AVE) values of each factor were checked. Measured variables with standardized factor loadings less than 0.5 were excluded from the analysis for the final model. Next, any factor with an AVE of less than 0.5 was determined to have low convergent validity and was excluded from the analysis. Reliability was verified using Cronbach’s α to assess the internal consistency (0.7 or more) and the construct reliability (CR; 0.7 or more). Finally, we compared the AVE of each latent factor to determine whether it was greater than the square of the correlation coefficient between the latent factors, and we confirmed whether the discriminant validity of the factor was high.

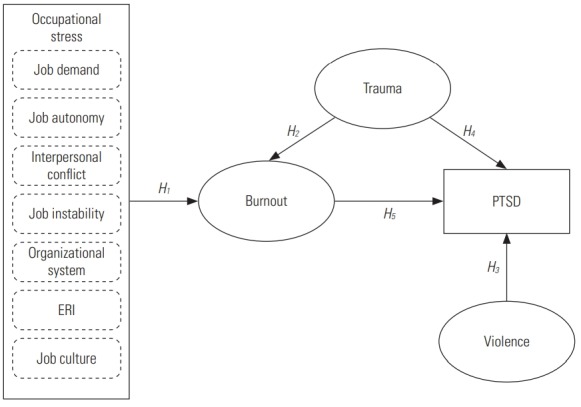

After conducting confirmatory factor analysis to confirm the reliability and validity of the model structure, the final analysis consisted of 6 questions related to job stress, 5 questions related to burnout, 5 questions related to violence exposure, and 5 questions related to trauma experience. A conceptual model was established, which was assessed using structural equation modeling (SEM) (Figure 1). Maximum likelihood estimation was used for analysis, and several fit indices were used to evaluate model fit: the chi-square test, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI; 0.9 or more), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; 0.05 or less), the standard root mean-square residual (SRMR; 0.05 or less), and the expected cross-validation index. Additionally, the comparative fit index (CFI; 0.9 or more), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; 0.9 or more), and the normed fit index (NFI; 0.9 or more) were used for the incremental fit index, and the normed chi-square (χ2/degrees of freedom [df], 3 or less) and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI; 0.9 or more) were used for the parsimonious fit index. After verifying the model fit by using the criteria for evaluation, the path coefficient and statistical significance of each path were determined through pathway analysis.

Figure. 1.

Conceptual framework of the study based on the Effect of Burnout on PTSD Symptoms in Firefighters model. Rectangles indicate observed variables, and ellipses represent latent variables/constructs. Single-headed arrows indicate a directional effe. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ERI, effort-reward imbalance.

Finally, after performing the bootstrapping hypothesis test (1000 times) to assess whether there was an indirect effect of trauma on PTSD through burnout, a mediation effect analysis was performed using the Sobel, Aroian, and Goodman tests.

The factor analysis, descriptive analysis, internal reliability of the scales, correlations between variables, SEM analysis, and bootstrap estimates were performed with R version 3.5.2 (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.5.2/) using the lavaan package. Mediation effect analyses were calculated using the Sobel test calculator (https://www.quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm).

Ethics Statement

All data were collected after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Yonsei University College of Medicine (4-2016-0187); the Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine (CR316014-002); and the Gyeongsang National University College of Medicine (2016-04-015-004).

RESULTS

The general characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2. Of the 535 participants, 513 (95.9%) were males and 22 (4.10%) were females. By service duty, 46.3% worked in fire-suppression groups, and 32.5% in rescue groups. Participants whose work hours exceeded 40 hr/wk (78.1%) constituted a larger group than those who worked fewer than 40 hr/wk (21.8%). The normality test results for each question showed that the absolute values of skewness and kurtosis were less than 3.0 and 10.0, respectively (Supplemental Material 1), thus satisfying SEM validity [28].

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants (n=535)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 513 (95.9) |

| Female | 22 (4.1) |

| Age (y) | |

| Under 30 | 62 (11.6) |

| 31-40 | 178 (33.2) |

| 41-50 | 140 (26.1) |

| More than 50 | 155 (29.1) |

| Years of continuous service (y) | |

| Under 10 | 258 (48.1) |

| 11-20 | 98 (18.3) |

| 21-30 | 148 (27.8) |

| More than 30 | 31 (5.8) |

| Working area | |

| Seoul | 46 (8.6) |

| Gyeonggi-do and Incheon | 32 (6.0) |

| Gangwon-do | 147 (27.5) |

| Chungcheong-do, Daejeon, and Sejong | 124 (23.2) |

| Gyeongsang-do, Daegu, Ulsan, and Busan | 151 (28.2) |

| Jeolla-do and Gwangju | 35 (6.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 151 (28.2) |

| Married | 384 (71.8) |

| Main job | |

| Fire suppression | 247 (46.2) |

| Rescue and emergency medical services | 174 (32.5) |

| Office work, telephone reception, etc. | 114 (21.3) |

| No. of working hours (hr/wk) | |

| ≤40 | 117 (21.8) |

| >40 | 418 (78.2) |

Because their standardized factor loadings were smaller than 0.5, we excluded 4 factors (autonomy, interpersonal conflict, job instability, and job culture) that related to job stress. The standardized factor loadings of the measurement variables for job demand, organizational system, ERI, burnout, trauma, and violence were all above 0.6, and they explained each factor well. All 6 factors were compliant with the criteria for AVE, CR, and Cronbach’s α.

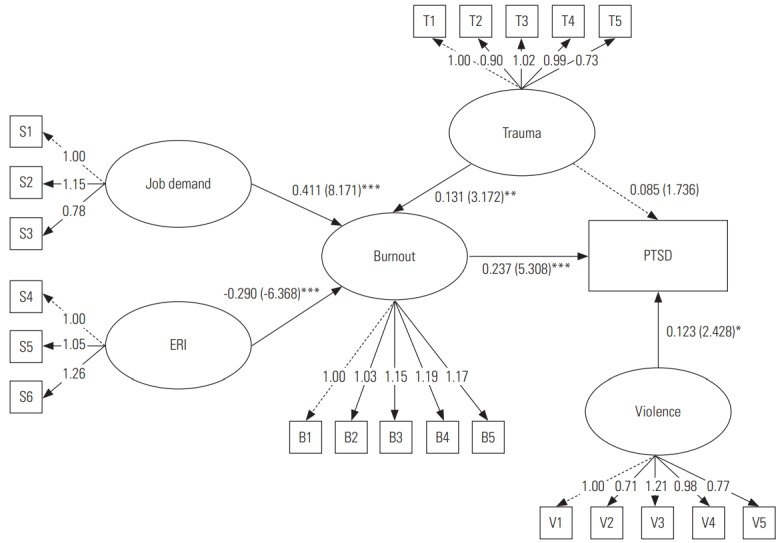

For the 6 factors remaining after the above process, the discriminant validity was evaluated. As a result, a correlation was found between the organizational system and ERI; therefore, we excluded the organizational system factor with the lower Cronbach’s α from the analysis model (Supplemental Material 2). Using the above process, the final model was derived (Figure 2).

Figure. 2.

Results from a structural equation model for the Effect of Burnout on PTSD Symptoms in Firefighters with parameter estimates and path diagram for the modified model. The model was fitted to the self-reported data of firefighters collected in the FRESH study (2016-2017). Rectangles indicate observed variables, and ellipses represent latent variables/constructs. Continuous arrows indicate significant effect while dashed arrows signify non-significant effects. PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; FRESH, Firefighter Research on Enhancement of Safety & Health; ERI, effort-reward imbalance. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Concerning model fitness, although the chi-square value was unsuitable, the value of χ2/df was 2.357, which met the conformity criteria. The other absolute fit indices—GFI (0.927), RMSEA (0.049), and SRMR (0.04)—were suitable. The incident fit indices—CFI (0.960), TLI (0.953), and NFI (0.931)—were also suitable. The value of AGFI using df was 0.906, which was appropriate for the model (Supplemental Material 3).

To verify the significance of the model path, parameter estimates for the free parameters, critical ratio, and 2-tailed p-values were evaluated (Table 3). A total of 6 paths were analyzed in this model (Figure 2). Participants who reported higher job demands and lower ERI were more likely to experience higher job burnout than those with lower job demands and a higher ERI. Both occupational stress and trauma experience were significantly associated with burnout. Job burnout and violence from clients were positively related with PTSD; however, trauma experience was not significantly related with PTSD scores (Supplemental Material 4).

Table 3.

Path coefficients estimated using linear regression in a structural equation model

| Factors | Variable | Standardized regression weight1 | SE | CR | Convergent validity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z-value | AVE | |||||

| Job demand | S1 | 0.751 | 0.435 | 0.758 | 24.196 | 0.513 |

| S2 | 0.773 | 0.402 | 25.742 | |||

| S3 | 0.614 | 0.623 | 15.343 | |||

| ERI | S4 | 0.703 | 0.506 | 0.800 | 18.068 | 0.575 |

| S5 | 0.674 | 0.546 | 14.238 | |||

| S6 | 0.882 | 0.222 | 29.979 | |||

| Burnout | B1 | 0.858 | 0.264 | 0.942 | 49.731 | 0.766 |

| B2 | 0.840 | 0.295 | 44.672 | |||

| B3 | 0.844 | 0.287 | 48.125 | |||

| B4 | 0.898 | 0.193 | 63.647 | |||

| B5 | 0.933 | 0.129 | 73.606 | |||

| Trauma | T1 | 0.806 | 0.35 | 0.880 | 41.263 | 0.597 |

| T2 | 0.738 | 0.455 | 26.820 | |||

| T3 | 0.831 | 0.309 | 35.539 | |||

| T4 | 0.851 | 0.276 | 45.920 | |||

| T5 | 0.612 | 0.625 | 16.466 | |||

| Violence | V1 | 0.722 | 0.478 | 0.842 | 25.137 | 0.520 |

| V2 | 0.622 | 0.613 | 15.786 | |||

| V3 | 0.865 | 0.252 | 35.258 | |||

| V4 | 0.745 | 0.445 | 20.143 | |||

| V5 | 0.626 | 0.609 | 17.904 | |||

SE, standard error; CR, construct reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; ERI, effort-reward imbalance.

Standardized regression weight=indicator reliability.

The Sobel test was performed to estimate the significance of the indirect effects of trauma on PTSD through burnout (Supplemental Materials 5 and 6). The effect of trauma on PTSD through burnout was significant (t=2.715, p=0.012). Trauma experience was not directly related to PTSD; however, the higher the degree of trauma, the more PTSD risk indirectly increased with burnout as a mediator. The Aroian (t=2.475, p= 0.013) and Goodman (t=2.551, p=0.011) tests were used to compare with the results of the Sobel test, and a similar association was observed.

DISCUSSION

Until now, most studies on PTSD among firefighters have focused only on job-related traumatic stress [29-31]. However, in this study, we explored the relationship between burnout due to work-related stress and PTSD symptoms in firefighters, and we investigated whether burnout affected PTSD symptoms in the context of a job characterized by violence and trauma. According to our results, firefighters were at high-risk of experiencing burnout and ERI. Interestingly, both burnout and violence affected PTSD symptoms; however, trauma experience was not directly associated with PTSD symptoms.

Among firefighters, in addition to physical trauma, mental stress may impact health. According to the National Fire Service Personnel Psychological Assessment Report, conducted in 2004, in Korea, firefighters are exposed to an average of 7.8 extreme trauma events per year, and PTSD prevalence in this group is 10.5 times that of the general population [32]. Due to the nature of firefighters’ work, they tend to be more vulnerable to secondary PTSD caused by repeated exposure to job-induced stress [18,33], rather than the primary post-traumatic stress that mostly occurs in victims who have directly experienced a traumatic event. However, it is not possible to reduce or avoid the exposure of firefighters to these events in their job environment. Therefore, it is necessary to identify and control the job-related risk factors of PTSD to promote firefighters’ mental health.

We also found that increased burnout caused by work-related stress was significantly associated with an increase in PTSD symptoms. According to a study of 208 firefighters in the southeastern USA, job stress and work-family conflict were associated with increased exhaustion among firefighters [34]. Research in France also showed that job control was negatively related to emotional exhaustion, while job demands were positively related to both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization [35]. Thus, it is suggested that programs aimed to prevent or mitigate burnout among firefighters may help prevent PTSD.

If relief from burnout has a primary effect on post-traumatic stress, PTSD may be prevented by controlling the factors that act as effect modifiers that weaken or enhance the development of burnout under the same stress levels. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the relevant factors through further research. In a recent study, self-efficacy was found to be a significant moderator in the relationship between work stress and burnout, regardless of the level of stress experienced; it was also found that firefighters with low self-efficacy tended to experience exhaustion [36]. In addition, it has been suggested that musculoskeletal symptoms [37] and auditory fatigue [38] may exacerbate factors related to occupational burnout.

Identifying the factors or variables that mediate burnout and PTSD in firefighters can help prevent post-traumatic symptoms resulting from trauma exposure by facilitating interventions to reduce it. According to a study conducted on 109 firefighters in Korea, burnout symptoms in those with a high sense of calling was significantly associated with an increased risk of PTSD [21]. Another study showed that among the subcategories of burnout symptoms, such as depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplishment [39], PTSD risk was significantly associated with depersonalization and job-related musculoskeletal injuries [40].

The most notable finding of our study is that trauma experience had an indirect effect on PTSD in firefighters as mediated by burnout. As mentioned above, given the job that firefighters have, it is not easy to avoid extreme scenes of trauma that leave a psychological aftereffect. However, considering our results, it may be possible to prevent the development of PTSD if occupational exhaustion is controlled for. Thus, it is necessary to improve firefighters’ working conditions to reduce job-related stress, which can cause burnout. Simultaneously, firefighters’ self-efficacy [36] and self-resilience [31] should be fostered to decrease their vulnerability to stress.

Our study has several advantages over earlier studies. First, unlike previous domestic studies that analyzed the relationship between burnout and PTSD in firefighters [21,31], participants in our study were recruited from all over the country, not just from a specific region or a few regions. However, the number of subjects in our study is small and cannot represent the over 40 000 firefighters nationwide; additionally, the regional distribution of our target sample is somewhat different from the actual distribution, so further research is needed to compensate for these limitations. Second, we used standardized study protocols and various clinical and psychological measurements (e.g., face-to-face interviews and Web-questionnaire surveys) that were not commonly used in previous studies.

Our study also has several limitations that must be considered. First, the nature of the cross-sectional design means that we cannot infer causality. In this study, we did not define PTSD-related exposure as the occurrence of specific events at a specific time, but rather as chronic and persistent occurrences within one’s work environment. For this reason, our analysis was conducted to suggest relevance rather than to propose causal relationships between factors. Thus, longitudinal data analysis should be conducted to determine the causality between job-related stress, burnout, and PTSD. Second, because we only examined firefighters, it is difficult to generalize our current results to other occupational groups. Future studies should compare the current results to employees with similar occupational characteristics. Third, a bias may be present due to the “healthy worker effect.” If firefighters with PTSD retire earlier than the average retirement age, or if those who were relatively health-conscious were more involved in the study, the analysis may have produced a lower PTSD score than it actually should have yielded. Finally, we did not control for certain conditions, such as quality of sleep and level of shift work, that may affect participants’ physical and mental health and could function as confounding factors.

Despite its limitations, this study helped clarify the relationship between burnout, trauma experience, and PTSD risk among firefighters in Korea using SEM. Overall, firefighters’ job demands and ERI were related to burnout. Additionally, burnout and psychological, sexual, and physical violence from clients were associated with the PTSD symptoms of these firefighters. There was no direct relationship between firefighters’ experience of trauma and PTSD symptoms; however, burnout mediated the relationship between trauma experience and PTSD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Fire Fighting Safety & 119 Rescue Technology Research and Development Program, which was funded by the National Fire Agency (No. MPSS-Fire-safety-2015-80). We thank all respondents for their participation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: WK, CK. Data curation: SJC, JHY, DSH, HYR, DYJ, MJK, KSP. Formal analysis: WK, CK. Funding acquisition: SJC, KSP, CK. Methodology: WK, CK. Project administration: MB, SJC, DYJ, KSP, CK. Visualization: WK. Writing - original draft: WK. Writing - review & editing: WK, MB, CK, SJC, KSP, JHY, DYJ, DSH, HYR, MJK.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Supplemental materials are available at https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.19.116.

The descriptive statistics, skewness and kurtosis of variables

Specification of a structural equation model for the Effect of Burnout on PTSD Symptoms in Firefighters, including mediating and effects of trauma. The model was fitted to the self-reported data of firefighters collected in the FRESH study (2016–2017). Rectangles indicate observed variables, and ellipses represent latent variables/constructs. Single-headed arrows indicate a directional effect.

The summary of goodness of fit indices for the hypothesized SEM model

Path analysis of the hypothesized SEM model.

Moderating effect of Trauma on PTSD

Mediation of impact of trauma on PTSD through burnout(left) and result of Sobel test(right).

REFERENCES

- 1.Dirkzwager AJ, Yzermans CJ, Kessels FJ. Psychological, musculoskeletal, and respiratory problems and sickness absence before and after involvement in a disaster: a longitudinal study among rescue workers. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61(10):870–872. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.012021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang SK, Kim W. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in firefighters. J Korean Med Assoc. 2008;51(12):1111–1117. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paley MJ, Tepas DI. Fatigue and the shiftworker: firefighters working on a rotating shift schedule. Hum Factors. 1994;36(2):269–284. doi: 10.1177/001872089403600208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kales SN, Soteriades ES, Christophi CA, Christiani DC. Emergency duties and deaths from heart disease among firefighters in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(12):1207–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soteriades ES, Smith DL, Tsismenakis AJ, Baur DM, Kales SN. Cardiovascular disease in US firefighters: a systematic review. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19(4):202–215. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318215c105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosénstock L, Demers P, Heyer NJ, Barnhart S. Respiratory mortality among firefighters. Br J Ind Med. 1990;47(7):462–465. doi: 10.1136/oem.47.7.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuwayhid IA, Stewart W, Johnson JV. Work activities and the onset of first-time low back pain among New York City fire fighters. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(5):539–548. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach C, Jackson SE. Maslach burnout inventory. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. pp. 191–218. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maslach C, Leiter M. Fink G. Stress: concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior. 1st ed. London: Academic Press; 2016. Burnout; pp. 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee J, Lim N, Yang E, Lee SM. Antecedents and consequences of three dimensions of burnout in psychotherapists: a meta-analysis. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2011;42(3):252–258. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appels A, Schouten E. Burnout as a risk factor for coronary heart disease. Behav Med. 1991;17(2):53–59. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1991.9935158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borritz M, Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Villadsen E, Kristensen TS. Burnout as a predictor of self-reported sickness absence among human service workers: prospective findings from three year follow up of the PUMA study. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(2):98–106. doi: 10.1136/oem.2004.019364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frajerman A, Morvan Y, Krebs MO, Gorwood P, Chaumette B. Burnout in medical students before residency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;55:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McManus IC, Winder BC, Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet. 2002;359(9323):2089–2090. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08915-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capel SA. A longitudinal study of burnout in teachers. Br J Educ Psychol. 1991;61(1):36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Ploeg E, Kleber RJ. Acute and chronic job stressors among ambulance personnel: predictors of health symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60 Suppl 1:i40–i46. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.suppl_1.i40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regehr C, Hemsworth D, Leslie B, Howe P, Chau S. Predictors of post-traumatic distress in child welfare workers: a linear structural equation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2004;26(4):331–346. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canfield J. Secondary traumatization, burnout, and vicarious traumatization: a review of the literature as it relates to therapists who treat trauma. Smith Coll Stud Soc Work. 2006;75(2):81–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.LaFauci Schutt JM, Marotta SA. Personal and environmental predictors of posttraumatic stress in emergency management professionals. Psychol Trauma. 2011;3(1):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brattberg G. PTSD and ADHD: underlying factors in many cases of burnout. Stress Health. 2006;22(5):305–313. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jo I, Lee S, Sung G, Kim M, Lee S, Park J, et al. Relationship between burnout and PTSD symptoms in firefighters: the moderating effects of a sense of calling to firefighting. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2018;91(1):117–123. doi: 10.1007/s00420-017-1263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chatzea VE, Sifaki-Pistolla D, Vlachaki SA, Melidoniotis E, Pistolla G. PTSD, burnout and well-being among rescue workers: seeking to understand the impact of the European refugee crisis on rescuers. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–355. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):139–145. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang SJ, Koh SB, Kang D, Kim SA, Kang MG, Lee CG, et al. Developing an occupational stress scale for Korean employees. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2005;17(4):297–317. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang SJ, Kang HT, Kim SK, Kim IA, Kim JI, Kim HR, et al. Development of Korean emotional labor scale and Korean work place violence scale. Incheon: Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency; 2015. pp. 70–75. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2015. pp. 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunello N, Davidson JR, Deahl M, Kessler RC, Mendlewicz J, Racagni G, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder: diagnosis and epidemiology, comorbidity and social consequences, biology and treatment. Neuropsychobiology. 2001;43(3):150–162. doi: 10.1159/000054884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sattler DN, Boyd B, Kirsch J. Trauma-exposed firefighters: relationships among posttraumatic growth, posttraumatic stress, resource availability, coping and critical incident stress debriefing experience. Stress Health. 2014;30(5):356–365. doi: 10.1002/smi.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JS, Ahn YS, Jeong KS, Chae JH, Choi KS. Resilience buffers the impact of traumatic events on the development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministry of the Interior and Safety National fire service personnel psychological assessment report. 2014 [cited 2019 Nov 19], Available from: https://www.mois.go.kr/mpss/safe/open/notice/%3Bjsessionid=CMGbgjCfaoqub9Km76YGQ2n9.node11?boardId=bbs_0000000000000049&mode=view&cntId=62&category=&pageIdx=39(Korean)

- 33.Oh JH, Lim NY. Analysis of factors influencing secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and physical symptoms in firefighters. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2006;13(1):96–106. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith TD, Hughes K, DeJoy DM, Dyal MA. Assessment of relationships between work stress, work-family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Saf Sci. 2018;103:287–292. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lourel M, Abdellaoui S, Chevaleyre S, Paltrier M, Gana K. Relationships between psychological job demands, job control and burnout among firefighters. N Am J Psychol. 2008;10(3):489–496. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makara-Studzińska M, Golonka K, Izydorczyk B. Self-efficacy as a moderator between stress and professional burnout in firefighters. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(2):183. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koch P, Stranzinger J, Nienhaus A, Kozak A. Musculoskeletal symptoms and risk of burnout in child care workers—a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santana Â, De Marchi D, Junior LC, Girondoli YM, Chiappeta A. Burnout syndrome, working conditions, and health: a reality among public high school teachers in Brazil. Work. 2012;41 Suppl 1:3709–3717. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-0674-3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katsavouni F, Bebetsos E, Malliou P, Beneka A. The relationship between burnout, PTSD symptoms and injuries in firefighters. Occup Med (Lond) 2016;66(1):32–37. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqv144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The descriptive statistics, skewness and kurtosis of variables

Specification of a structural equation model for the Effect of Burnout on PTSD Symptoms in Firefighters, including mediating and effects of trauma. The model was fitted to the self-reported data of firefighters collected in the FRESH study (2016–2017). Rectangles indicate observed variables, and ellipses represent latent variables/constructs. Single-headed arrows indicate a directional effect.

The summary of goodness of fit indices for the hypothesized SEM model

Path analysis of the hypothesized SEM model.

Moderating effect of Trauma on PTSD

Mediation of impact of trauma on PTSD through burnout(left) and result of Sobel test(right).