Abstract

Eggless/SETDB1 (Egg), the only essential histone methyltransferase (HMT) in Drosophila, plays a role in gene repression, including piRNA‐mediated transposon silencing in the ovaries. Previous studies suggested that Egg is post‐translationally modified and showed that Windei (Wde) regulates Egg nuclear localization through protein–protein interaction. Monoubiquitination of mammalian SETDB1 is necessary for the HMT activity. Here, using cultured ovarian somatic cells, we show that Egg is monoubiquitinated and phosphorylated but that only monoubiquitination is required for piRNA‐mediated transposon repression. Egg monoubiquitination occurs in the nucleus. Egg has its own nuclear localization signal, and the nuclear import of Egg is Wde‐independent. Wde recruits Egg to the chromatin at target gene silencing loci, but their interaction is monoubiquitin‐independent. The abundance of nuclear Egg is governed by that of nuclear Wde. These results illuminate essential roles of nuclear monoubiquitination of Egg and the role of Wde in piRNA‐mediated transposon repression.

Keywords: Eggless, monoubiquitination, piRNA, SETDB1, Windei

Subject Categories: Chromatin, Epigenetics, Genomics & Functional Genomics; Post-translational Modifications, Proteolysis & Proteomics; Transcription

Eggless/SETDB1 (Egg) is a H3K9 methyltransferase essential for piRNA‐mediated transposon silencing. Its nuclear monoubiquitination and the cofactor Wde independently regulate the catalytic activity and localization of Egg.

Introduction

Trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3) is a major repressive histone mark, leading to heterochromatin formation and gene silencing 1, 2, 3. In Drosophila, H3K9 methylation is governed by three histone methyltransferases (HMTs), Su(var)3‐9, G9a, and Eggless/SETDB1 (Egg) 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Of those, Egg is the only essential H3K9 methyltransferase in Drosophila and is required for H3K9 trimethylation in the ovaries 4, 8, 11.

In the ovaries, loss‐of‐function Egg mutations lead to derepression of transposons at loci where H3K9me3 is decreased 12. Transposon silencing in the ovaries is mostly, if not all, triggered by PIWI‐interacting RNAs (piRNAs). piRNAs are small non‐coding RNAs enriched in the germline. piRNAs assemble the piRNA‐induced silencing complexes (piRISCs) with members of the PIWI family of proteins 13, 14, 15, 16. piRNAs show high complementarity to transposon RNA transcripts in both sense and antisense orientations and repress transposons transcriptionally, by inducing local heterochromatinization, or post‐transcriptionally, by cleaving target RNAs 13, 14, 15, 16. In Drosophila ovarian somatic cells (OSCs), piRNAs assemble piRISCs solely with Piwi, the only nuclear member of the PIWI protein family, and, with multiple co‐factors, transcriptionally repress transposons 12, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. One of these co‐factors is Egg 12, 21. The loss of Egg decreases H3K9me3 levels at Piwi target loci and nearby regions, leading to local transposon (and genes, if any) derepression.

SETDB1 is the mammalian ortholog of Egg 22 and is essential for viability 23, 24. The loss of SETDB1 causes transposon silencing in embryonic stem cells and primordial germ cells in both sexes 25, 26. Recent studies showed that in non‐gonadal mammalian cells, such as 293T cells, human SETDB1 is monoubiquitinated at Lys867 and that this post‐translational modification is required for HMT activity in vitro and in vivo 27, 28. Lys867 is located within the unique spacer that intervenes in the catalytic SET domain by dividing the domain into two regions. It was proposed that Lys867 monoubiquitination causes the two regions to gather in close proximity to restore HMT activity 28. This lysine residue is conserved in Drosophila Egg (Lys1085) and is also located within the SET domain spacer. However, the spacer length differs in Drosophila and mice, consisting of 95 and 342 residues in Egg and SETDB1, respectively. Whether the lysine modification and its role in controlling HMT function are conserved in Egg remains to be elucidated.

Windei (Wde) encodes a chromatin‐associated protein 29. Wde is required for survival of female germline cells 29 and piRNA‐mediated transposon silencing in Drosophila 21. Wde binds Egg 29, 30 and controls Egg nuclear localization 29. The Wde‐interacting domain in Egg includes the first Tudor domain at the N‐terminal region 29, 31. Wde function appears to be conserved across species 32, 33, 34. The mammalian homolog is mAM/MCAF1/ATF7IP (ATF7IP) 34. Depletion of ATF7IP decreases H3K9me3 and increases H3K9me2 levels 34. Furthermore, ATF7IP binds SETDB1 in the nucleus to protect the partner protein being degraded by proteasomal machinery 35. The link between Wde and Egg is evident. However, the precise function of Wde and the mechanism by which Wde regulates Egg localization and function remain elusive.

It has been shown that Egg is modified with the small ubiquitin‐related modifier (SUMO) and suggested that this modification might be involved in the formation of higher order chromatin‐modifying complexes 29. Proteomic analyses predict that Egg is phosphorylated at Ser215 and Thr217 36. Results observed for SETDB1 27, 28 suggest that Egg might also be monoubiquitinated. However, the actual post‐translational modification(s) of Egg and their functional significance have not been elucidated. Therefore, we set out to explore Egg post‐translational modification(s) using cultured OSCs. We chose cultured OSCs because the piRNA pathway, where the Egg function is essential 12, is active in these cells 37.

Results

Egg in OSCs is monoubiquitinated and phosphorylated but not SUMOylated

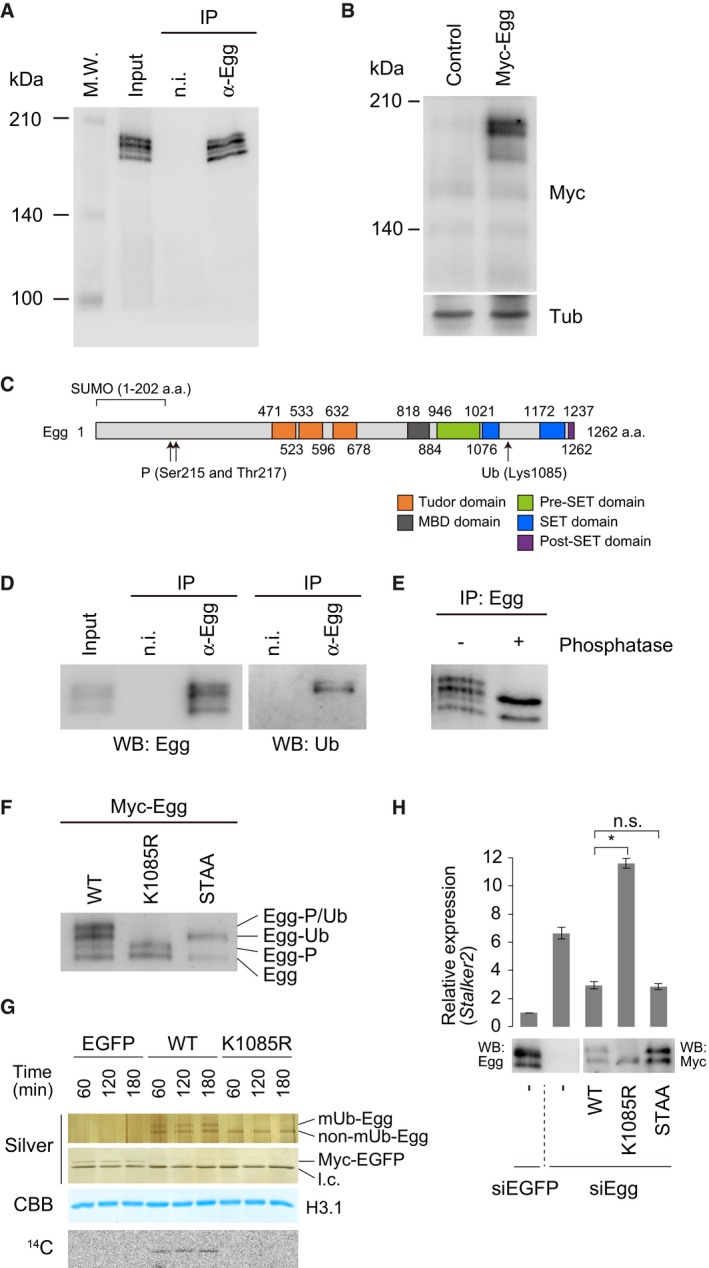

In OSCs, Egg was detected on Western blots as four distinct bands before and after immunoprecipitation (Fig 1A), indicating potential post‐translational modification. Alternatively, this could indicate alternative splicing of Egg pre‐mRNAs, with each band corresponding to a different isoform. The latter explanation was excluded by transient expression of Myc‐Egg (from Egg full‐length cDNA) in OSCs, which appeared as four distinct bands on Western blots, similar to endogenous Egg (Fig 1B).

Figure 1. Post‐translational modifications of Egg in OSCs.

- Western blotting of endogenous Egg immunopurified from OSCs. Anti‐Egg antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting. Input: OSC total lysates used for IP. n.i.: non‐immune IgG used as an IP negative control. M.W. indicates protein molecular weight marker.

- Western blotting of Myc‐Egg expressed in OSCs. Anti‐Myc (Myc) and anti‐β‐Tubulin (Tub) antibodies were used. Tub was detected as a loading control. Control: empty vector was used as a negative control.

- Schematic of Egg domain structure. The predicted regions and sites for SUMOylation (SUMO: 1–202 a.a.), phosphorylation (Ser125 and Thr217), and ubiquitination (Lys1085) are shown.

- Western blotting of endogenous Egg immunopurified from OSCs. Anti‐Egg antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation (IP). Anti‐Egg and anti‐Ub antibodies were used for Western blotting (WB). Input: OSC total lysates used for IP. n.i.: non‐immune IgG used as an IP negative control.

- Western blotting of Egg immunopurified from total OSC lysates before (−) and after (+) phosphatase treatment. Anti‐Egg antibodies were used for both immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting.

- Western blotting of Myc‐Egg WT and its K1085R and S215/T217 (STAA) mutants expressed in OSCs. Egg modifications identified in this study are summarized on the right. P: phosphorylation. Ub: monoubiquitination.

- In vitro histone methyltransferase assays. Top and second from the top: silver staining of purified Myc‐Egg and Myc‐EGFP. Second from the bottom: CBB staining of histone H3.1. Bottom: 14C autoradiogram. EGFP: Myc‐EGFP was used as a negative control. l.c.: light chain of antibody. Time: reaction time (min) of individual samples.

- Rescue assays. Myc‐Egg WT and its K1085R and STAA mutants were expressed in OSCs upon endogenous Egg depletion (siEgg). Western blotting (WB) was performed using anti‐Egg and anti‐Myc antibodies. RT–qPCR was used to quantify Stalker2 transposon expression level. The act5c gene was used for normalization. siEGFP: siRNA for EGFP was used as a negative control. Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (unpaired Student's t‐test). n.s.: not significant.

Source data are available online for this figure.

The domain structures 4, 11, 31 and predicted Egg post‐translational modification sites 27, 28, 29, 36 are summarized in Fig 1C. We first immunoisolated Egg from OSCs and probed with anti‐ubiquitin (Ub) antibodies. The upper two of the four Egg bands were positive for ubiquitin (Fig 1D). The difference in band mobility between the Ub‐positive and Ub‐negative bands was approximately 10 kDa, suggesting monoubiquitination of Egg in OSCs, as is the case for SETDB1 28. To examine Egg phosphorylation status, we treated immunopurified Egg with phosphatase and performed Western blotting with anti‐Egg antibodies. The first and the third bands from the top disappeared after dephosphorylation (Fig 1E). These results suggest that Egg in OSCs is monoubiquitinated and phosphorylated.

To determine the modification sites, Egg Lys1085 and Ser215/Thr217 were altered to arginine (K1085R) and alanines (STAA), respectively. Western blotting showed that the K1085R mutant co‐migrated with the two lower Egg wild‐type (WT) bands, while the STAA mutant co‐migrated with the second and fourth Egg WT bands (Fig 1F). Therefore, in OSCs, Egg is monoubiquitinated at Lys1085 and phosphorylated at Ser215 and/or Thr217 (Fig 1F).

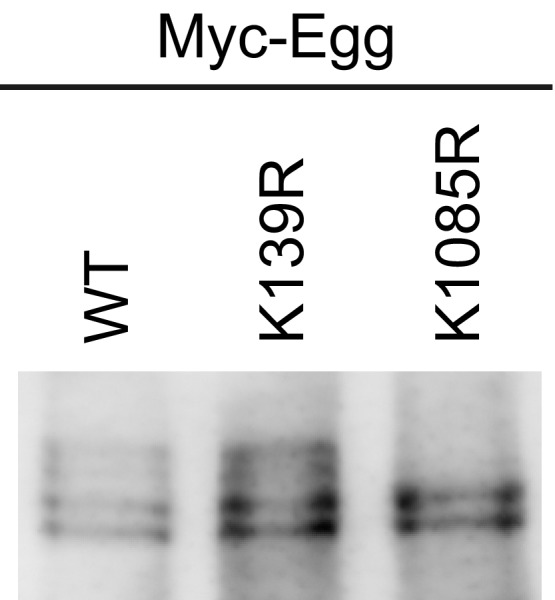

The N‐terminal region of Egg (1–202 amino acids) was detected to be SUMOylated in Schneider 2 (S2) cells 29. The GPS‐SUMO predictor 38 predicted that Lys139 resides in the consensus sequence for SUMOylation (Pro138‐Asp141). We mutated this lysine to arginine and expressed in OSCs (Myc‐Egg K139R). However, this mutant remained to be four bands on Western blots (Fig EV1) as is the case of Myc‐Egg WT (Fig 1B). These findings suggested that SUMOylation is not a major modification for Egg in OSCs.

Figure EV1. Post‐translational modifications of Egg in OSCs (related to Fig 1).

Western blotting of Myc‐Egg WT and its K139R and K1085R mutants expressed in OSCs. Anti‐Myc‐antibody was used for Western blotting.Source data are available online for this figure.

Monoubiquitination is essential for Egg function in vitro and in vivo

Mammalian SETDB1 exhibits HMT activity in vitro exclusively when monoubiquitinated 28. We immunoisolated Myc‐tagged Egg WT and the K1085R mutant from OSCs and conducted in vitro HMT assays using purified histone H3.1 as the substrate. Monoubiquitinated Egg (mUb‐Egg), but not the monoubiquitination‐defective K1085R mutant, exhibited HMT activity (Fig 1G). These results show that, like SETDB1, monoubiquitination is essential for Egg HMT activity in vitro.

To explore the roles of Egg modifications in vivo, we performed rescue assays. Egg WT and K1085R mutant were individually expressed in OSCs depleted of endogenous Egg. Stalker2, a transposon controlled by the piRNA pathway 17, was upregulated without Egg (Fig 1H). Ectopic expression of Egg WT, but not the K1085R mutant, rescued this defect (Fig 1H). These results suggest that monoubiquitination is required for Egg to function in the somatic piRNA pathway in vivo. Following the ectopic expression of Egg K1085R mutant, the level of Stalker2 was ~1.7 times higher than that in Egg‐lacking cells (Fig 1H). The reason for this unexpected outcome remains unknown. The phosphorylation‐defective STAA mutant repressed Stalker2 expression as efficiently as did WT Egg. Thus, phosphorylation is dispensable for Egg function in the piRNA pathway (Fig 1H).

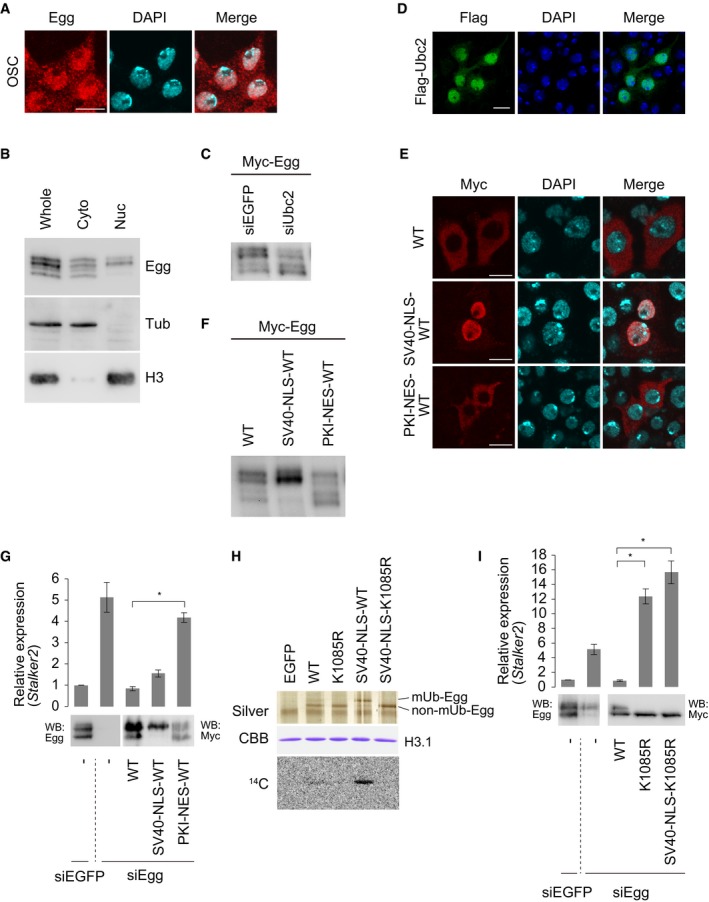

Egg monoubiquitination occurs in the nucleus in OSCs

Immunofluorescence showed that, in OSCs, Egg is localized to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm as has been shown in the ovaries 4 (Figs 2A and EV2A and B). Western blotting of cell‐fractionated materials supported this observation (Fig 2B). The latter experiment also revealed that mUb‐Egg was present in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, while non‐ubiquitinated Egg (non‐Ub‐Egg) was nearly exclusively cytoplasmic (Fig 2B). Two hypotheses arose from these results: (i) Egg is translocated to the nucleus upon being monoubiquitinated in the cytoplasm, and (ii) Egg is monoubiquitinated in the nucleus, but a small fraction of it may be exported back to the cytoplasm for unknown reasons. The cytoplasmic signal of mUb‐Egg (Fig 2B) may reflect an artificial, unavoidable leakage of the protein from the nucleoplasm during the fractionation process. However, this does not exclude the second hypothesis.

Figure 2. Egg monoubiquitination occurs in the nucleus Ubc2‐dependently.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of OSCs using anti‐Egg antibodies. Endogenous Egg is shown in red. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blotting of fractionated OSC materials. Anti‐Egg, anti‐β‐Tubulin (Tub), and anti‐histone H3 antibodies were used. H3 and Tub were detected as markers for nuclear (Nuc) and cytoplasmic (Cyto) fractions, respectively. Whole: the whole OSC lysates.

- Western blotting of Myc‐Egg expressed in OSCs before (siEGFP) and after (siUbc2) Ubc2 depletion. Anti‐Myc‐antibody was used for Western blotting. The ratios of mUb‐Egg over non‐mUb‐Egg band signals were 1.43 (siEGFP) and 0.78 (siUbc2).

- Immunofluorescence analysis using anti‐Flag antibody to identify Flag‐Ubc2 (green) expressed in OSCs. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg, and Myc‐PKI‐NES‐Egg expressed in OSCs using anti‐Myc antibody. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blotting of Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg, and Myc‐PKI‐NES‐Egg expressed in OSCs. Anti‐Myc antibody was used. The ratios of mUb‐Egg over non‐mUb‐Egg band signals were 1.50 (WT), 2.29 (SV40‐NLS), and 0.95 (PKI‐NES).

- Rescue assays. Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg, and Myc‐PKI‐NES‐Egg were expressed in OSCs upon endogenous Egg depletion (siEgg). Western blotting was performed using anti‐Egg (left) and anti‐Myc (right) antibodies. Stalker2 transposon expression was quantified using RT–qPCR. The act5c gene was used for normalization. siEGFP: siRNA for EGFP was used as a negative control. Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (unpaired Student's t‐test).

- In vitro HMT assays. Top: silver staining of purified Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐Egg K1085R, Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT, and Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg K1085R. Middle: CBB staining of histone H3.1. Bottom: 14C autoradiogram. Myc‐EGFP was used as a negative control (EGFP: not shown).

- Rescue assays. Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐Egg K1085R, and Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐K1085R were expressed in OSCs upon endogenous Egg depletion (siEgg). Western blotting was performed using anti‐Egg (left) and anti‐Myc (right) antibodies. RT–qPCR quantified the expression level of the Stalker2 transposon. The act5c gene was used for normalization. siEGFP: siRNA for EGFP was used as a negative control. Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (unpaired Student's t‐test).

Source data are available online for this figure.

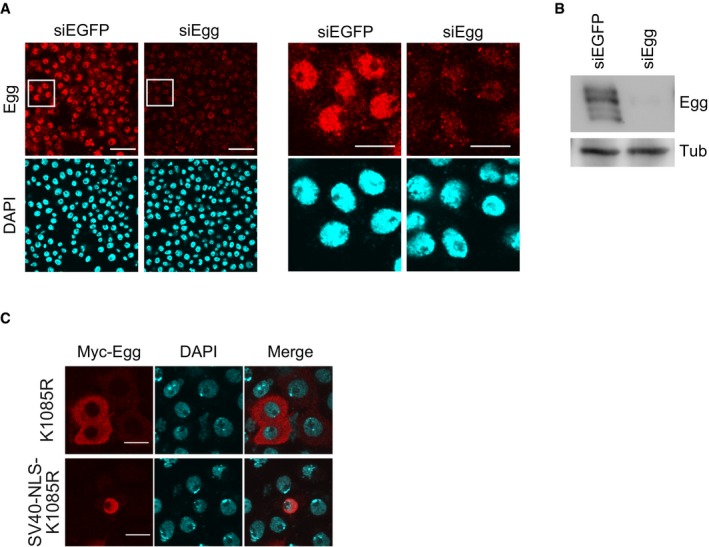

Figure EV2. Egg monoubiquitination occurs in the nucleus Ubc2‐dependently (related to Fig 2).

- Immunofluorescence analysis of OSCs before (siEGFP) and after (siEgg) Egg depletion by RNAi. Anti‐Egg antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 20 μm. Right panels are a magnified view of the area surrounded by a white box in the left panel. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blot of endogenous Egg in OSCs before (siEGFP) and after (siEgg) Egg depletion by RNAi. Anti‐Egg and anti‐Tub antibodies were used. Tub was detected as a loading control.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of the Myc‐Egg K1085R mutant plus/minus SV40‐NLS. Anti‐Myc antibody was used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

SETDB1 monoubiquitination is performed by members of the UBE2E family of E2 enzymes in a E3‐independent manner 28. Our RNA sequencing data suggest that Ubc2, the Drosophila homolog of UBE2E1, is expressed in OSCs 39. We depleted Ubc2, expressed Myc‐Egg, and examined the level of monoubiquitination. The level of mUb‐Egg was significantly reduced by the absence of Ubc2 (Fig 2C). It was also found that ectopically expressed Flag‐Ubc2 was localized to the nucleus (Fig 2D). These results suggest that Egg monoubiquitination is a nuclear event and that Ubc2 is the major modifier.

In sharp contrast to endogenous Egg, Myc‐Egg ectopically expressed in OSCs existed mostly in the cytoplasm (Fig 2E). This phenomenon was also observed when Egg was ectopically expressed in S2 cells 29. We fused the simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen nuclear localization signal (SV40‐NLS) 40 onto Egg to force nuclear import and accumulation. This led to aberrant accumulation of Myc‐Egg in the nucleus (Fig 2E). Moreover, the level of Myc‐Egg monoubiquitination was greatly increased (Fig 2F). qRT–PCR showed that the Stalker2 transposon, whose expression level increased following the loss of Egg, was silenced following ectopic expression of both Egg WT and SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT (Fig 2G). A feasible explanation for this is that, although appearing in the cytoplasm, Egg WT is transiently imported into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, Egg WT may have been monoubiquitinated before relocating to the cytoplasm. This notion was further supported by the observation that the level of mUb‐Egg expressed in Egg‐depleted OSCs (WT lane in the WB panel, Fig 2G) was higher than the level of mUb‐Egg expressed in normal OSCs (WT lane in Fig 2F).

Fusion of the cAMP‐dependent protein kinase inhibitor nuclear export signal (PKI‐NES) 41 to Egg resulted in PKI‐NES‐Egg and WT Egg being mostly cytoplasmic and a significant decrease in the level of mUb‐Egg (Fig 2E and F). Taken together, these results suggest that the degree of Egg monoubiquitination is determined by the duration of nuclear residence (i.e., the time right after nuclear import until nuclear export). This is consistent with the observation that Egg ubiquitination is a nuclear event. In the rescue assays, PKI‐NES‐Egg failed to restore transposon silencing (Fig 2G). These results highlight the importance of Egg monoubiquitination and residence time in the nucleus in piRNA‐mediated transposon silencing.

Enforced nuclear accumulation of Egg by SV40‐NLS fusion also increased HMT activity (Fig 2H). In contrast, the monoubiquitination‐defective K1085R mutant, even after SV40‐NLS fusion, showed no HMT activity (Fig 2H). This mutant failed to silence transposons despite strong nuclear accumulation (Figs 2I and EV2C). These findings indicate that nuclear localization itself is insufficient for Egg to exhibit HMT activity and function in the piRNA pathway.

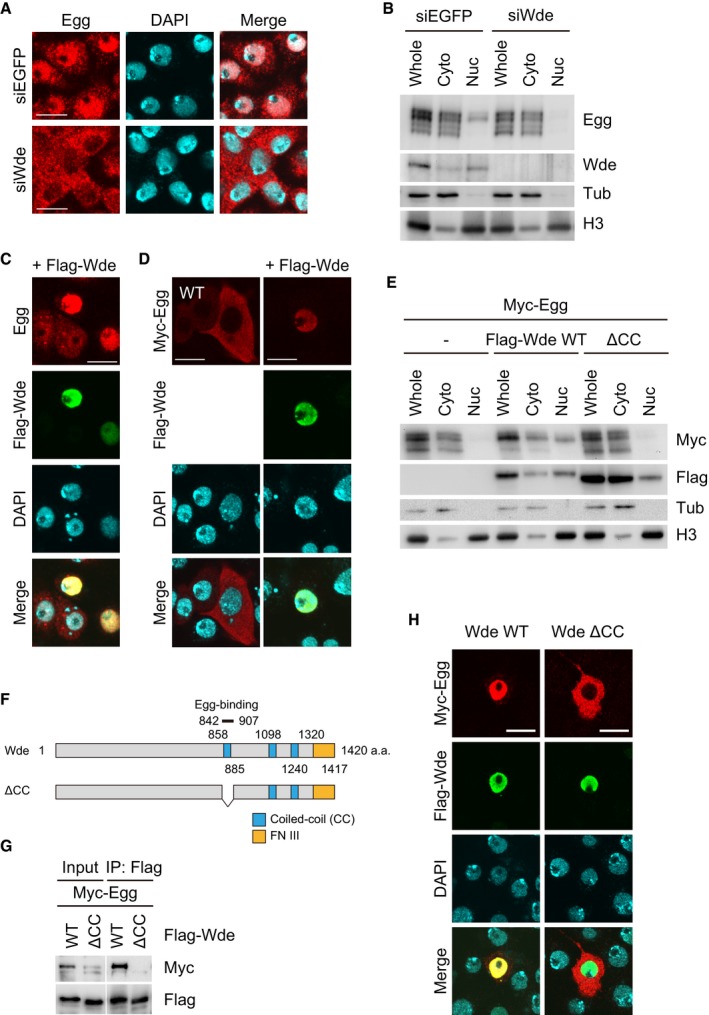

Wde controls nuclear retention but not nuclear import of Egg in OSCs

In Drosophila non‐gonadal somatic S2 cells, the nuclear localization of Egg is impacted by the presence or absence of Wde 29. We confirmed that the cellular localization of endogenous Egg in OSCs was also affected by loss of Wde (Fig 3A). However, in the absence of Wde, Egg was still monoubiquitinated to a similar extent as that in normal OSCs (see the “Whole” lanes in Fig 3B). As noted above, monoubiquitination is indicative of nuclear import and residence of Egg. These results indicate that loss of Wde does not affect the nuclear import of Egg. However, in the absence of Wde, the nuclear mUb‐Egg signal was almost completely diminished (see the “Nuc” lanes in Fig 3B). These strongly suggest that Wde plays a role in the nuclear retention of Egg.

Figure 3. Wde controls the abundance and monoubiquitination level of Egg in the nucleus.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of endogenous Egg (red) in OSCs using anti‐Egg antibody before (siEGFP) and after (siWde) Wde depletion. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blotting on fractionated materials of OSCs before (siEGFP) and after (siWde) Wde depletion. Anti‐Egg, anti‐Wde, anti‐Tub, and anti‐H3 antibodies were used. H3 and Tub were detected as markers for nuclear (Nuc) and cytoplasmic (Cyto) fractions, respectively. Whole: whole OSC lysates.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of endogenous Egg (red) in OSCs upon Flag‐Wde (green) co‐expression. Anti‐Egg and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg WT (red) in OSCs upon Wde co‐expression (green). Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blotting on fractionated materials of Myc‐Egg‐expressed OSCs before (−) and after Wde WT and Wde ΔCC co‐expression. Anti‐Myc, anti‐Flag, anti‐Tub, and anti‐H3 antibodies were used. H3 and Tub were detected as markers for nuclear (Nuc) and cytoplasmic (Cyto) fractions, respectively. Whole: the whole OSC lysates.

- The schematic drawing of domain structures of Wde WT and its ΔCC mutant. The ΔCC mutant lacks the Egg‐binding domain (842–907 a.a).

- Protein–protein interaction assays. Myc‐Egg and Flag‐Wde WT and its ΔCC mutant were expressed in OSCs. Immunoprecipitation was conducted using anti‐Flag antibody, while anti‐Myc (upper) and anti‐Flag (lower) antibodies were used for Western blotting.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg WT (red) in OSCs upon Flag‐Wde WT and ΔCC mutant (green) co‐expression. Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We then ectopically expressed Wde in OSCs. Endogenous Egg was detected nearly exclusively in the nuclei of Flag‐Wde‐expressing OSCs (Fig 3C). Myc‐Egg also strongly accumulated in the nucleus upon Wde co‐expression (Fig 3D). Ectopic expression of Wde resulted in higher mUb‐Egg levels (see the “Whole” lanes and Wde WT in Fig 3E). Thus, the levels of Egg nuclear retention and monoubiquitination depend on the Wde level.

Wde has three coiled‐coil (CC) motifs and a fibronectin type III domain (Fig 3F). The region containing the first CC motif was determined to be the Egg‐binding domain 29. We produced a ΔCC mutant lacking the first CC motif and confirmed that Wde WT, but not the ΔCC mutant, co‐immunopurified with Egg (Fig 3G). In contrast to co‐expression of Wde WT, co‐expression of the Wde ΔCC mutant had little impact on the cellular localization of Egg (Fig 3H) and the level of mUb‐Egg (see “Whole” lanes and Wde ΔCC in Fig 3E). These findings indicate that the physical interaction of Wde with Egg is critical for the Egg nuclear‐retaining function. Egg‐independent nuclear import of Wde was also suggested. We propose that Wde plays a role in the nuclear retention of Egg in OSCs.

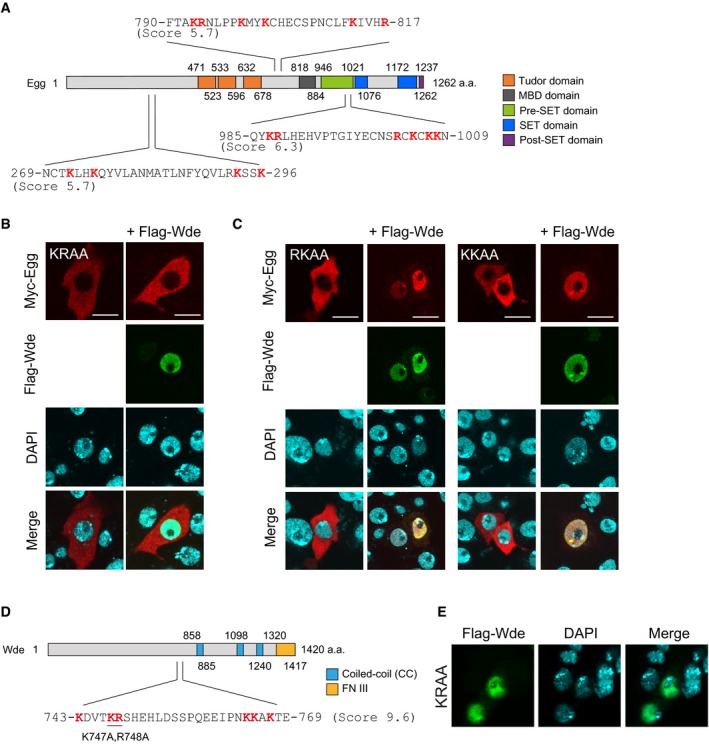

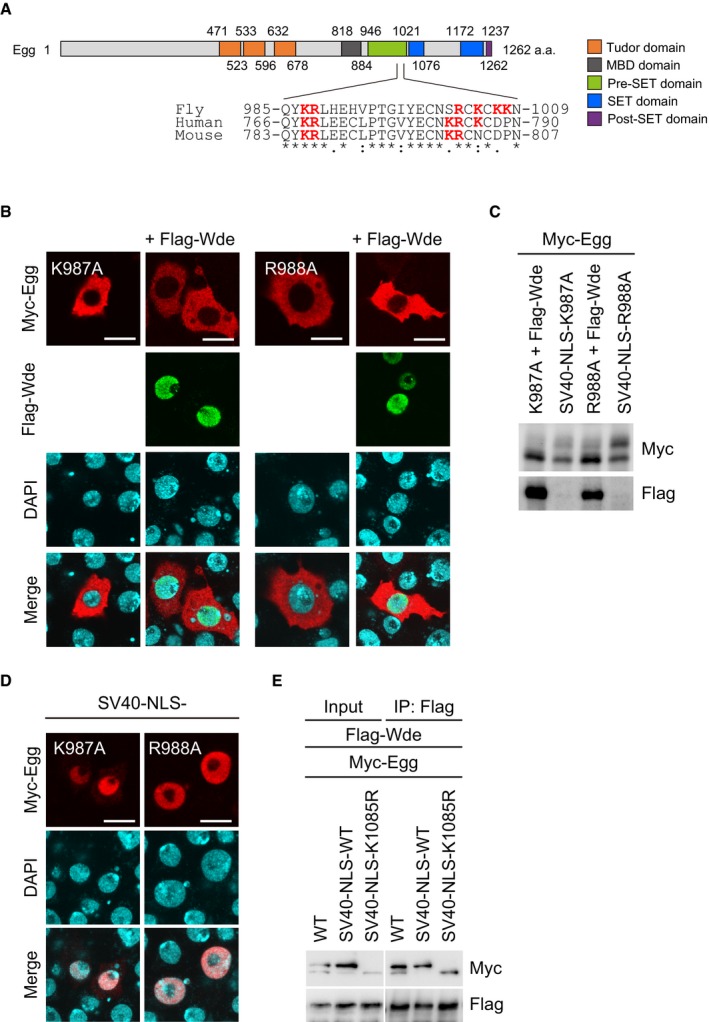

Egg has a basic NLS in the pre‐SET domain and is imported into the nucleus in a Wde‐independent manner

The cNLS mapper 42 predicted NLSs in three different regions of Egg (Fig EV3A). The predicted NLS within the pre‐SET domain (Gln985‐Asn1009) had the highest predictive value (Fig EV3A). This region is composed of 25 residues and is rich in basic residues with arginine and lysine residues accounting for 24.0% of the total. The sequence is well conserved in flies, mice, and humans (Fig 4A). The other two NLS candidates were less well conserved across species.

Figure EV3. Determination of Egg‐NLS (related to Fig 4).

- Schematic of Egg domain structure and predicted NLS sites in Egg. Cutoff scores from the cNLS mapper are indicated.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg KRAA mutant (red) in OSCs before and after Flag‐Wde (green) co‐expression. Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm. KRAA mutant: Lys987 and Arg988 were altered to alanines by mutagenesis.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg RKAA and KKAA mutants (red) in OSCs before and after Flag‐Wde (green) co‐expression. Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm. RKAA mutant: Arg1003 and Lys1005 were altered to alanines by mutagenesis. KKAA mutant: Lys1007 and Lys1008 were altered to alanines by mutagenesis.

- Schematic of Wde domain structure and a predicted NLS site in Wde. Cutoff scores from the cNLS mapper are indicated.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Flag‐Wde WT or KRAA (green) in OSCs. anti‐Flag antibody was used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm. KRAA mutant: Lys747 and Arg748 were altered to alanines by mutagenesis.

Figure 4. Determination of Egg‐NLS .

- Schematic of the domain structure of Egg. The amino acid sequence alignment of the predicted Egg‐NLS in fly, humans, and mice is also shown. Asterisks, colons, and periods indicate identical, highly conserved, and weakly conserved residues, respectively. The letters in red indicate basic residues.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐Egg K987A, and Myc‐Egg R988A mutants (red) in OSCs before and after Flag‐Wde (green) co‐expression. Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blotting of Myc‐Egg WT and its K987A and R988A mutants. Flag‐Wde: Flag‐Wde was co‐expressed. SV40‐NLS: SV40‐NLS was added to Myc‐Egg. Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of Myc‐Egg K987A and Myc‐Egg R988A mutants (red) in OSCs. Both mutants were fused to SV40‐NLS. Anti‐Myc antibody was used for detection. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Protein–protein interaction assays. Myc‐Egg WT, Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT, and Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg K1085R mutant were expressed with Flag‐Wde in OSCs. Immunoprecipitation was conducted using anti‐Flag antibody, while anti‐Myc (upper) and anti‐Flag (lower) antibodies were used for Western blotting.

Source data are available online for this figure.

We individually mutated Lys987 and Arg988 in the pre‐SET domain to alanine and examined how the K987A and R988A mutations affected Egg cellular localization. In contrast to Egg WT (Fig 3D), both K987A and R988A mutants appeared to be cytoplasmic, even after Wde co‐expression (Fig 4B). A KRAA double mutant, where Lys987 and Arg988 were simultaneously mutated to alanines, behaved similar to the single KA and RA mutants (Fig EV3B). Western blotting showed that the K987A and R988A mutants were minimally monoubiquitinated (Fig 4C). These results suggest that both mutants were defective in nuclear import.

Addition of the SV40‐NLS to the K987A and R988A mutants resulted in their accumulation in the nucleus in the absence of Wde co‐expression (Fig 4D). In these experiments, only a small proportion of the K987A mutant was monoubiquitinated, while a large proportion of the R988A mutant was monoubiquitinated (Fig 4C). Thus, the roles of the two residues are distinct. Lys987 is required for both the nuclear import and monoubiquitination of Egg, while Arg988 is essential for nuclear import but is dispensable for monoubiquitination. Two other mutants R1003A/K1005A (RKAA) and K1007A/K1008A (KKAA) localized to the nucleus in the presence of Wde co‐expression (Fig EV3C). Therefore, these results show that the basic stretch in the pre‐SET domain (Fig 4A) is the Egg‐NLS and that K987 and R988 but not other basic residues are responsible for the function.

The cNLS mapper predicted that Wde has one bipartite NLS (Fig EV3D). We mutated two basic residues within the potential NLS sequence with the higher predictive score to alanines (K747 and R748). However, the KRAA mutant was detected in the nuclei of OSCs at the same frequency as Wde WT (Fig EV3E). Therefore, the Wde‐NLS remains to be identified.

These findings proposed an independence between Egg and Wde in their nuclear localization. On the basis of this, we speculated that cytoplasmic Wde may not bind with nascent Egg in its unubiquitinated form. However, the monoubiquitination‐defective K1085R mutant associated with Wde to a similar extent as Egg WT (Fig 4E). Therefore, monoubiquitination appears to have little impact on the Egg‐Wde interaction. Some unknown cytoplasmic factor(s) may prevent the Egg‐Wde interaction to allow for their independent nuclear import.

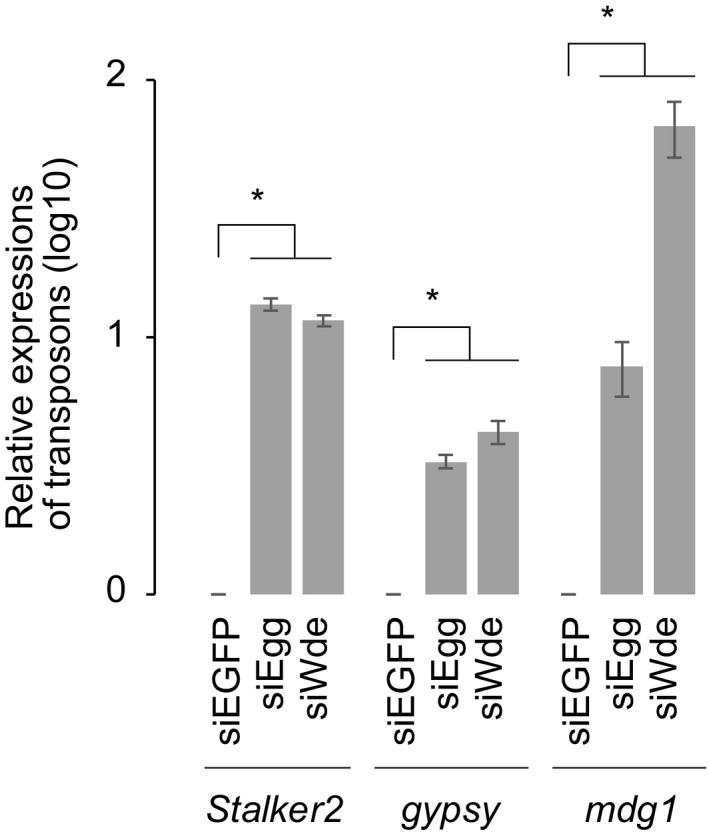

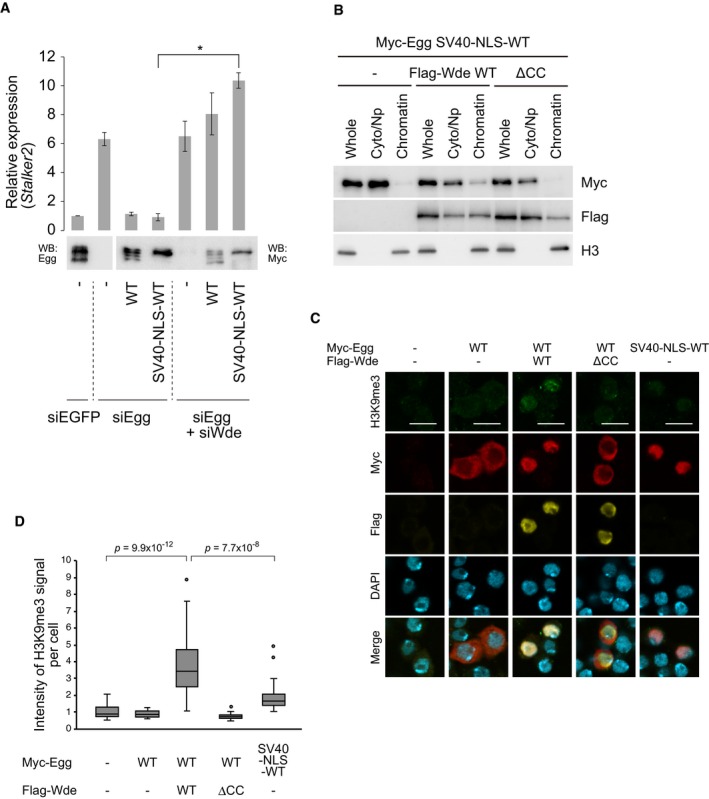

Wde plays a role in recruiting mUb‐Egg to transposon loci for silencing

Depletion of Egg in OSCs derepressed piRNA‐regulated transposons such as Stalker2, mdg1, and gypsy 12. In this study, the loss of Wde phenocopied it (Fig EV4), confirming the important role of Wde in the piRNA pathway 21.

Figure EV4. Wde‐mediated Egg recruitment to the chromatin leads to H3K9me3 deposition (related to Fig 5).

RT–qPCR was performed for Piwi target transposons (Stalker2, mdg1, and gypsy) in control (siEGFP), Egg‐depleted (siEgg), or Wde‐depleted (siWde) OSCs. Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (unpaired Student's t‐test).

Our findings thus far showed that Wde controls the nuclear retention of Egg in OSCs. However, the activity of SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT in silencing transposons was much lower in the absence of Wde, despite the high degree of Egg monoubiquitination (Fig 5A). Thus, a function(s) of Wde in addition to Egg nuclear retention is required for the silencing activity of Egg. Because Wde is a chromatin‐binding protein 29, we inferred that the additional but unknown function(s) of Wde might be related to the recruitment of Egg to chromatin. To test this, the chromatin fraction was separated from the fraction containing cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic materials and the abundance of Myc‐Egg in each fraction was determined by Western blotting. We found that after co‐expression of Wde, Myc‐Egg was more abundantly found in the chromatin fraction (Fig 5B). As expected, co‐expression of the ΔCC mutant failed to retain Myc‐Egg in the chromatin fraction (Fig 5B). Immunofluorescence showed that the level of H3K9me3 was much higher in OSCs when both Egg WT and Wde WT were co‐expressed (Fig 5C and D). Although SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT was localized to the nucleus without Wde co‐expression, the level of H3K9me3 was as low as that in normal OSCs (Fig 5C and D). These results suggest that Wde‐mediated mUb‐Egg recruitment to the chromatin leads to H3K9me3 deposition.

Figure 5. Wde‐mediated Egg recruitment to the chromatin leads to H3K9me3 deposition.

- Rescue assays. Myc‐Egg WT and Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT were expressed in OSCs upon endogenous Egg and Wde depletion (siEgg and siWde). Western blotting was performed using anti‐Egg (left) and anti‐Myc (right) antibodies. RT–qPCR quantified the expression level of Stalker2 transposon. The act5c gene was used for normalization. siEGFP: siRNA for EGFP was used as a negative control. Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 (unpaired Student's t‐test).

- Western blotting of Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT in whole (Whole), cytoplasm/nucleoplasmic (Cyto/Np), and chromatin (Chromatin) fractions before (−) and after Flag‐Wde co‐expression. Anti‐Myc and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. Histone H3 was detected as a marker of chromatin fraction.

- Immunofluorescence analysis of H3K9me3 (green), Myc‐Egg WT (red), and Myc‐SV40‐NLS‐Egg WT (red) in OSCs before and after Flag‐Wde (yellow) co‐expression. Anti‐H3K9me3, anti‐Myc, and anti‐Flag antibodies were used. DAPI (blue) shows the nuclei. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Box plots indicating the H3K9me3 signal intensities per cell related to Figure 5B (P values based on unpaired Welch's t‐test). Box plots show median (line) and 25th–75th percentile (box) ± 1.5 interquartile range (n > 25 cells for each box). Circles represent outliers.

Source data are available online for this figure.

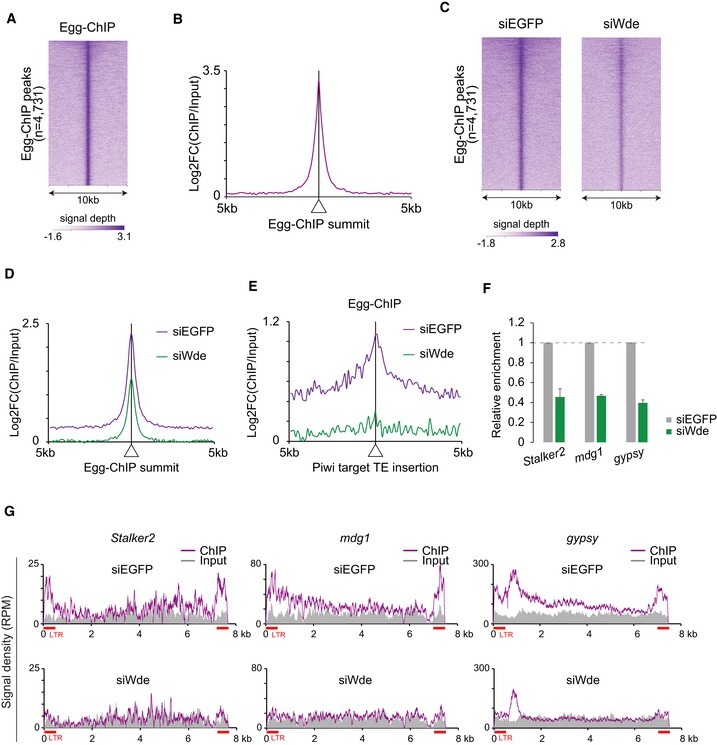

We then performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments using anti‐Egg antibodies. The Egg‐chromatin binding was clearly detected (Fig 6A and B). However, the binding was significantly weakened by the loss of Wde (Fig 6C and D). Prominent Egg accumulation was observed at the Piwi target transposon loci, which was greatly attenuated by Wde depletion (Fig 6E). PCR‐based analyses at the genomic insertions of Stalker2, mdg1, and gypsy confirmed this (Fig 6F). We then mapped the ChIP signals on Stalker2, mdg1, and gypsy, which revealed that Egg can bind weakly in the middle of genes and relatively strongly around the long terminal repeats (LTRs) (Fig 6G). These results indicate that Egg physically interacts with the genomic transposon loci to transcriptionally repress them via H3K9me3 deposition, and further support the original notion that Wde recruits mUb‐Egg to transposon loci for H3K9me3 deposition and transposon silencing.

Figure 6. Wde controls Egg function by recruiting the protein to the chromatin in OSCs.

- Heatmap of Egg ChIP‐seq within a 10 kb window centered on Egg peaks. Note that ChIP peaks were called using the ChIPed and Input samples and used for analyses.

- Metaplots showing Egg ChIP‐seq signals for genomic regions around Egg peaks. Displayed are fold‐changes in Egg occupancy normalized to input.

- Heatmaps of Egg ChIP‐seq signal within 10 kb windows centered on Egg peaks in control (siEGFP) and Wde‐depleted (siWde) OSCs.

- Metaplots showing Egg ChIP‐seq signals for genomic regions around Egg peaks. Displayed are fold‐changes in Egg occupancy normalized to input.

- Metaplots showing Egg ChIP‐seq signals for genomic regions around transposon (TE) insertions.

- ChIP‐qPCR was performed before (siEGFP) and after (siWde) Wde depletion. qPCR was performed for Piwi target transposons (Stalker2, mdg1, and gypsy) and normalized to %input of a Piwi non‐target transposon (roo). Error bars represent SD from three independent experiments.

- Density plots for Egg ChIP‐seq signal on Stalker2, mdg1, and gypsy in control (siEGFP) and Wde‐depleted (siWde) OSCs. Input: input DNA was used as a control. RPM: reads per million mapped reads.

Discussion

In this study, we revealed that Egg is phosphorylated at Ser215 and/or Thr217, monoubiquitinated at Lys1085, but is not SUMOylated in OSCs. Monoubiquitination, but not phosphorylation, of Egg is necessary for in vitro HMT activity and for in vivo transposon silencing. Our results also show that Egg monoubiquitination is a nuclear event and that the Ubc2 E2 ligase plays a major role in this modification. At present, where Egg is phosphorylated in OSCs and by which enzyme remain unknown.

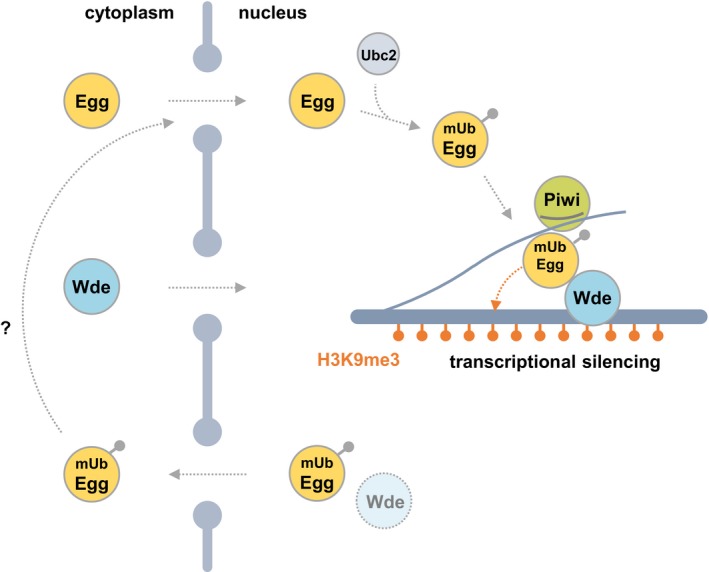

We provided evidence, indicating that in OSCs, both Egg and Wde are independently imported into the nucleus (see the model in Fig EV5). We also identified the Egg‐NLS, located in the pre‐SET domain. The Egg‐NLS was fairly basic but only two basic residues, Lys987 and Arg988, were essential for nuclear import. This may be uncommon, but we speculate that the weaker NLS means that the Wde‐dependent nuclear retention of Egg (to ensure H3K9me3 deposition) is more controllable.

Figure EV5. Model for Egg/Wde roles in piRNA‐mediated transposon silencing.

Egg and Wde are imported independently into the nucleus. Upon translocation, Ubc2 monoubiquitinates Egg‐Wde‐independently. Wde binds mUb‐Egg and recruits it to transposon loci on the genome. mUb‐Egg finally deposits H3K9me3 at the loci to repress transposons. mUb‐Egg with no Wde binding is returned to the cytoplasm. mUb‐Egg in the cytoplasm may be degraded or reimported into the nucleus.

Egg was monoubiquitinated in the nucleus, and the reaction was Wde‐independent. This means that Egg monoubiquitination might occur in the nucleoplasm immediately upon its nuclear import. After this event, Wde‐bound mUb‐Egg is recruited to the chromatin to deposit H3K9me3 for gene silencing (Fig EV5). If the amount of Wde is somehow limited in the nucleus, mUb‐Egg becomes orphaned, cannot bind chromatin, and is ejected back to the cytoplasm. Therefore, Wde determines the number of functional mUb‐Egg proteins in the nucleus. Previous studies showed that Egg may or may not be strongly accumulated in the cytoplasm depending on the timing during embryonic development and oogenesis 4, 30. We assume that this dynamic subcellular localization of Egg may be explained by Wde expression levels. It is of interest to assess this hypothesis experimentally.

Wde is also considered to “guide” for mUb‐Egg as piRNA does for Piwi. Without Wde, nucleoplasmic mUb‐Egg may not be able to identify the correct targets of its HMT function. Upon monoubiquitination, orphaned Egg may be able to trimethylate histones nucleoplasmically prior to their recruitment in nucleosomes. This would disturb the regulation of local gene expression through highly ordered histone modifications. Export of chromatin‐unbound Egg to the cytoplasm prevents such disruption.

The cytoplasmic mUb‐Egg detected by Western blotting after cell fractionation may merely reflect mUb‐Egg leaked from the nucleoplasm. Alternatively, cytoplasmic mUb‐Egg may have some functions in the cytoplasm. Previous studies suggested that mammalian SETDB1 can mono‐ and dimethylate cytoplasmic histone H3 43, 44. Furthermore, recent studies showed that SETDB1 plays a role in methylating cytoplasmic AKT for cell growth regulation 45, 46. Therefore, it is possible that cytoplasmic mUb‐Egg may also be responsible for modifying cytoplasmic proteins, including histones, in OSCs. This could be determined, and substrates identified, in future studies.

How does Wde know where to recruit Egg for H3K9me3 deposition? One feasible explanation is that Wde interacts with Piwi‐piRISCs in a silencing action mode in the nucleus. However, in OSCs and in other Drosophila cells, Egg functions in a wide range of gene silencing pathways, most of which do not involve Piwi. In mammals, it has been shown that some transcriptional factors function in recruiting SETDB1 to the target genes 22, 47, 48, 49, although whether ATF7IP is involved in this recruitment remains unknown. Further analyses are anticipated.

In human cells, SETDB1 acts as an oncogene 50, although the mechanism through which aberrant SETDB1 activation evokes tumorigenesis remains unclear. Our study did not aim to address this particular question. We describe a system for regulating nuclear Egg function in gene (transposon) silencing. The two independent but sequential requirements, of nuclear monoubiquitination and the co‐factor Wde guidance, might act as a fail–safe mechanism to prevent tumorigenesis.

Tsusaka et al 51 simultaneously but independently reported that mammalian SETDB1 also exhibits nuclear monoubiquitination and that ATF7IP, the mammalian homolog of Wde, retains SETDB1 in the nucleus. The interspecies conservation of the post‐translational modification of Egg/SETDB1 and the function of Wde/ATF7IP is suggested.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Ovarian somatic cells were grown at 26°C in culture medium prepared from Shields and Sang M3 Insect Medium (Caisson) supplemented with 0.6 mg/ml glutathione, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mU/ml insulin, and 10% fly extract 37.

Production of anti‐Egg monoclonal antibodies (2C10‐E9 and 1F3‐C8)

Anti‐Egg monoclonal antibodies were raised specifically against the N‐terminus of the protein. A 405‐amino‐acid N‐terminal Egg fragment, fused to glutathione S‐transferase (GST), was used as the antigen to immunize mice. The anti‐Egg monoclonal antibodies were produced essentially as previously described 52. Of note, the supernatant of the hybridoma cell culture was used for Western blotting and immunoprecipitation.

Subcellular fractionation

For fractionation of nuclei, OSCs were suspended in hypotonic buffer containing 10 mM HEPES KOH (pH 7.3), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5% aprotinin, by pipetting gently 5–6 times and passing through a 25G needles three times. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation at 400 g for 10 min at 4°C, and then lysed in sample buffer containing SDS as the nuclear fraction (Nuc). The supernatant was treated using trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation to concentrated proteins and was suspended in the sample buffer to form the cytoplasmic fraction (Cyto). Whole OSCs were collected as the whole‐cell fraction (Whole). For fractionation of chromatin, 2 mM EDTA was added to hypotonic buffer instead of 1.5 mM MgCl2. Following procedures were essentially the same as fractionation of nuclei.

Plasmid construction

To construct Myc‐Egg, a full‐length egg cDNA was amplified by PCR and subcloned into pAcM 37 under the control of the actin 5C promoter. To construct Flag‐Wde and Flag‐Ubc2, full‐length wde and ubc2 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pAcF 53 under the control of the actin 5C promoter. To produce pUb vector, the actin 5c promoter of pAc5.1B was replaced with a ubiquitin promoter at BglII and KpnI sites 52. Inserts containing Myc‐Egg or Flag‐Wde were amplified and subcloned into pUb. The pAcM‐SV40‐NLS vector was used to generate SV40‐NLS‐fused constructs 53. DNA oligos containing PKI‐NES were inserted into the pAcM vector to generate the pAcM‐PKI‐NES vector. Inverse PCR techniques were used to generate deletion mutations and point mutations. The primer sets used are shown in Table EV1.

RNAi and plasmid transfection

For the RNAi, trypsinized OSCs (3 × 106 cells) were suspended in 20 μl of Solution SF from the Cell Line Nucleofector Kit SF (Amaxa Biosystems) together with 200 pmol of siRNA duplex. Transfection was conducted in a 96‐well electroporation plate using a Nucleofector device 96‐well Shuttle (Amaxa Biosystems). Transfected cells were transferred to fresh OSC medium and incubated at 26°C for 2–4 days for further experiments. The siRNA sequences used are shown in Table EV1. For cellular fractionation followed by Western blotting, trypsinized OSCs (1 × 107 cells) were suspended in 100 μl of the nucleofector solution containing 180 mM Church's phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 5 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM D‐mannitol, together with 2–4 μg of plasmid and cells were transfected with electroporation cuvettes using a Nucleofector device 2b (Amaxa Biosystems). Transfected cells were transferred to fresh OSC medium and incubated at 26°C for 2 days. For immunofluorescence, plasmids were transfected using ScreenFect A (Wako) or Nucleofector device 2b (Amaxa Biosystems) following the manufacturer's instructions. For in vitro methylation assays, plasmid transfection was performed using Xfect Transfection Reagent (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, OSCs were 50% confluent the day before the transfection. Plasmid (4 μg) and 1.2 μl of Xfect polymer were mixed well and added to OSCs in Shields and Sang M3 Insect Medium (Sigma). After incubation at 26°C for 3 h, the medium was replaced with the fresh OSC medium. OSCs were further incubated for 2 days.

Plasmid rescue assay

Trypsinized OSCs (3 × 106 cells) were suspended in 20 μl of Solution SF from the Cell Line Nucleofector Kit SF with 200 pmol of siRNA duplex. Transfection was conducted in a 96‐well electroporation plate using a Nucleofector device 96‐well Shuttle. After incubation in the OSC medium at 26°C for 2 days, the cells (1 × 107 cells) were suspended in 100 μl of the nucleofector solution together with 600 pmol of siRNA duplex and 6 μg of plasmid. Transfection was conducted in electroporation cuvettes using a Nucleofector device 2b. The transfected cells were transferred to fresh OSC medium and incubated at 26°C for 2 days for further experiments.

RNA isolation and real‐time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using ISOGEN II (Nippon Gene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For cDNA preparation, the Transcriptor First‐Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real‐time PCR was performed as previously described 54. In brief, cDNA fragments were amplified with StepOnePlus (Applied Biosystems) using the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primer sets used are shown in Table EV1. The quantitative PCR amplification efficiency was calculated based on the slope of the standard curve. After confirming amplification efficiency values (between 95% and 105%), relative steady‐state RNA levels were determined from the threshold cycle for amplification.

Immunoprecipitation

For co‐immunoprecipitation, Egg protein was immunoprecipitated from OSCs using anti‐Egg antibodies (2C10‐E9, hybridoma supernatant) in 50 mM HEPES KOH (pH 7.3), 200 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5% aprotinin. For the dephosphorylation assay and immunopurification, RIPA buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mM DTT, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5% aprotinin, or Empigen buffer containing 1% Empigen, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5% aprotinin in PBS, was used. In brief, the OSC lysate was incubated with 5 μg of anti‐Egg antibody (protein concentration was approximately 2 mg/ml) for 2 h at 4°C with rotation. Then, Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added and further incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. After incubation, the bead fractions were washed five times using the same buffer, and the protein complexes were eluted from the beads by heating with sample buffer containing SDS for 10 min at 70°C. The protein fractions were then loaded onto SDS–PAGE gels. After electrophoresis, proteins were visualized by Western blot analyses.

Dephosphorylation assay

The Egg protein was immunoprecipitated from OSCs using anti‐Egg antibody (see Immunoprecipitation) and then incubated in the Dynabeads with Antarctic Phosphatase (NEB) at 37°C for 15 min.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously 54. Anti‐Egg (2C5‐C10) 52, anti‐Wde (gift from A. Wodarz), anti‐Myc (Sigma C3956 and C3936), anti‐Flag (Sigma F3165), anti‐ubiquitin (MBL FK2), anti‐H3 (Abcam ab85869), and anti‐H3K9me3 (Active Motif 61013) antibodies were used. The anti‐β‐Tubulin antibody was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB E7). Anti‐mouse IgG, HRP‐linked antibody (MP Biomedicals, 55558), and anti‐rabbit IgG, HRP‐linked antibody (CST 7074S) were purchased from the manufacturers. Images were captured and processed using ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare) or ChemiDoc Imaging Systems (Bio‐Rad). The signal intensity of bands was quantified by ImageJ (NIH).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence of OSCs was performed using anti‐Egg (IF3‐C8, hybridoma supernatant), anti‐H3K9me3 (Active Motif 61013), anti‐Myc (9E10, hybridoma supernatant, or SIGMA C3956, 1:1,000 dilution), or anti‐Flag (SIGMA, rabbit polyclonal, 1:150 dilution, or SIGMA F3165, 1:1,000 dilution) antibodies. OSCs were fixed using 1% or 4% formaldehyde (Thermo Fisher, methanol‐free, or Wako 063‐04815) and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X‐100 in PBS for 24 h post‐transfection. Alexa Fluor 633‐conjugated anti‐mouse IgG1 (Invitrogen, 1:1,000 dilution), Alexa Fluor 546‐conjugated anti‐mouse IgG (Molecular Probes, 1:500 dilution), Alexa Fluor 488‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, 1:500 dilution), or Alexa Fluor 488‐conjugated anti‐mouse IgG2b (Invitrogen, 1:1,000 dilution) was used as secondary antibodies. Slides were mounted in VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). All images were captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus, FV3000, or Carl Zeiss, LSM 710). Image processing and annotation were performed using ZEN software (Carl Zeiss) and Adobe Photoshop (Adobe). Quantification of H3K9me3 signals was processed by Fiji 55. Both Myc‐Egg and DAPI channel were used to generate masks. Regions of interest (ROI) were generated by these masks by the function “Analyze Particles”. The mean fluorescence intensity of H3K9me3 staining was defined as “Mean gray value”. Thresholds were defined manually for each channel (6,500 for Myc‐Egg, 11,000 for DAPI) so that expressed cells were correctly selected. Once the thresholds were determined, quantification was automated using customized macros.

In vitro histone methylation assay

Myc‐tagged Egg‐expressing OSCs (1 × 108 cells) were lysed in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 0.1–0.5% NP‐40, 0.5 mM DTT, 2 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, and 0.5% aprotinin and then treated by sonication with Branson Digital Sonifier on ice. After centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected and incubated with 5 μg of anti‐Myc antibody at 4°C for 60 min (protein concentration was approximately 2 mg/ml), followed by the addition of 50 μl of Dynabeads. After incubation at 4°C for 40 min, the bead fractions were washed four times with lysis buffer and once in methylation buffer containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 5 mM DTT. The bead fractions were then incubated with 1 μg of histone H3.1 (1 μg/μl), which was kindly gifted from H. Kurumizaka (The University of Tokyo), and 1 μl of 14C‐SAM (PerkinElmer NEC363, 10 uCi/500 μl) in 10 μl of the methylation buffer at 30°C for 1–3 h. The reaction was stopped with 10 μl of the sample buffer containing SDS at 95°C for 5 min and then loaded onto SDS–PAGE gels. After electrophoresis, proteins were visualized by CBB staining and Silver staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific LC6070). The 14C signals were detected by Typhoon FLA 9500 (GE Healthcare).

ChIP‐qPCR and ChIP‐seq

ChIP was performed as described previously 18, 19. In brief, OSCs (5–10 × 107) were crosslinked by addition of 1% formaldehyde (Wako) added directly to the medium for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were rinsed twice with PBS and harvested using a silicon scraper and flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer 1 containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP‐40, 0.25% Triton X‐100, and 10% glycerol, supplemented with cOmplete ULTRA Tablets, EDTA‐free (Roche), and passed through a 20G syringe needle three times. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer 2 containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 140 mM NaCl, and 2 mM EDTA, supplemented with cOmplete ULTRA Tablets, EDTA‐free (Roche). After centrifugation, samples were sonicated in sonication buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 140 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100, and 0.1% SDS, supplemented with cOmplete ULTRA Tablets, EDTA‐free (Roche), using Covaris at 140 W for 15 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. For each sample, 100 μg of chromatin was incubated overnight at 4°C with 20 μg of anti‐Egg antibodies (2C10‐E9) and 100 μl of Dynabeads Protein G. Beads were washed once with sonication buffer, once with high salt buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100 and 0.1% SDS), once with LiCl buffer (containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM LiCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP‐40, and 1% sodium deoxycholate), and twice with TE20 buffer (containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), and 2 mM EDTA). Bound complexes were eluted from the beads in elution buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, and 1% SDS) by heating at 65°C for 30 min with agitation. Crosslinking was reversed by adding 8 μl of 5 M NaCl and incubating at 65°C overnight. Input samples were also treated for crosslink reversal. De‐crosslinked samples were treated with RNase A and Proteinase K. DNA was purified by phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol extraction. The DNA amounts were quantitatively measured by real‐time PCR or sequencing. Libraries for high‐throughput sequencing were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II FS DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB) and sequenced on MiSeq (Illumina) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primer sets and DNA oligos used are shown in Table EV1.

Bioinformatics analysis

Adapter‐trimmed sequences were mapped to the Drosophila melanogaster release 6 (dm6) genome assembly by bowtie2 (ver. 2.2.4) using default parameters. The dm6 genome was downloaded through piPipes 56. Read counts corresponding to each genomic and genic position were obtained by generating bedgraph files from BAM files (binary version of SAM files) using the BEDTools genomecov. All samples were normalized to have the equivalent of reads per million (RPM) using the “‐scale” option. ChIP peak calling was performed using MACS2 setting “‐q 0.01”. The heatmap and metaplot were achieved using Ngsplot (ver. 2.61). A list of TE insertions (dm3) in OSCs were obtained from a previous publication 20. The TE insertion sites were converted from dm3 to dm6 using the UCSC liftOver tool. The insertions of the Piwi‐targeting TEs were classified based on the degree of reduction in the H3K9me3 levels at the franking regions of insertions (± 3 kb windows) upon Piwi depletion in OSCs. The insertions in which the H3K9me3 levels in Piwi‐depleted OSCs were reduced to < 0.8 compared with those in non‐depleted OSCs were defined as Piwi‐targeting TE insertions.

Author contributions

KO, KS, and MCS conceived the project, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. KO, KS, and KM performed the experiments. KS performed the bioinformatics analyses. KO, KS, KM, HS, and MCS analyzed data and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Suzuki and M. Ariura for technical assistance. We thank A. Wodarz and H. Kurumizaka for providing us valuable experimental materials for our study. We also thank R. Onishi and other Siomi laboratory members for insightful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research from AMED. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to K.S., K.M., H.S., and M.C.S.

EMBO Reports (2019) 20: e48296

These authors contributed equally to this work

and https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201949262 (December 2019)

Data availability

Deep sequencing data sets have been deposited in the NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are available under accession number GEO: GSE128203.

References

- 1. Janssen A, Colmenares SU, Karpen GH (2018) Heterochromatin: guardian of the genome. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 34: 265–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin C, Zhang Y (2005) The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 838–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mozzetta C, Boyarchuk E, Pontis J, Ait‐Si‐Ali S (2015) Sound of silence: the properties and functions of repressive Lys methyltransferases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16: 499–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clough E, Moon W, Wang S, Smith K, Hazelrigg T (2007) Histone methylation is required for oogenesis in Drosophila . Development 134: 157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elgin SCR, Reuter G (2013) Position‐effect variegation, heterochromatin formation, and gene silencing in Drosophila . Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5: a017780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mis J, Ner SS, Grigliatti TA (2006) Identification of three histone methyltransferases in Drosophila: dG9a is a suppressor of PEV and is required for gene silencing. Mol Genet Genomics 275: 513–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schotta G (2002) Central role of Drosophila SU(VAR)3‐9 in histone H3‐K9 methylation and heterochromatic gene silencing. EMBO J 21: 1121–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seum C, Reo E, Peng H, Rauscher FJ, Spierer P, Bontron S (2007) Drosophila SETDB1 is required for chromosome 4 silencing. PLoS Genet 3: e76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tschiersch B, Hofmann A, Krauss V, Dorn R, Korge G, Reuter G (1994) The protein encoded by the Drosophila position‐effect variegation suppressor gene Su(var)3‐9 combines domains of antagonistic regulators of homeotic gene complexes. EMBO J 13: 3822–3831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tzeng TY, Lee CH, Chan LW, Shen CKJ (2007) Epigenetic regulation of the Drosophila chromosome 4 by the histone H3K9 methyltransferase dSETDB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12691–12696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clough E, Tedeschi T, Hazelrigg T (2014) Epigenetic regulation of oogenesis and germ stem cell maintenance by the Drosophila histone methyltransferase Eggless/dSetDB1. Dev Biol 388: 181–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sienski G, Batki J, Senti KA, Dönertas D, Tirian L, Meixner K, Brennecke J (2015) Silencio/CG9754 connects the Piwi–piRNA complex to the cellular heterochromatin machinery. Genes Dev 29: 2258–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aravin AA, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J (2007) The Piwi‐piRNA pathway provides an adaptive defense in the transposon arms race. Science 318: 761–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Czech B, Munafò M, Ciabrelli F, Eastwood EL, Fabry MH, Kneuss E, Hannon GJ (2018) piRNA‐guided genome defense: from biogenesis to silencing. Annu Rev Genet 52: 131–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ozata DM, Gainetdinov I, Zoch A, O'Carroll D, Zamore PD (2018) PIWI‐interacting RNAs: small RNAs with big functions. Nat Rev Genet 20: 89–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yamashiro H, Siomi MC (2017) PIWI‐interacting RNA in Drosophila: biogenesis, transposon regulation, and beyond. Chem Rev 118: 4404–4421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Donertas D, Sienski G, Brennecke J (2013) Drosophila Gtsf1 is an essential component of the Piwi‐mediated transcriptional silencing complex. Genes Dev 27: 1693–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iwasaki YW, Murano K, Ishizu H, Shibuya A, Iyoda Y, Siomi MC, Siomi H, Saito K (2016) Piwi modulates chromatin accessibility by regulating multiple factors including histone H1 to repress transposons. Mol Cell 63: 408–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ohtani H, Iwasaki YW, Shibuya A, Siomi H, Siomi MC, Saito K (2013) DmGTSF1 is necessary for Piwi‐piRISC‐mediated transcriptional transposon silencing in the Drosophila ovary. Genes Dev 27: 1656–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sienski G, Dönertas D, Brennecke J (2012) Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell 151: 964–980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu Y, Gu J, Jin Y, Luo Y, Preall JB, Ma J, Czech B, Hannon GJ (2015) Panoramix enforces piRNA‐dependent cotranscriptional silencing. Science 350: 339–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schultz DC (2002) SETDB1: a novel KAP‐1‐associated histone H3, lysine 9‐specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1‐mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc‐finger proteins. Genes Dev 16: 919–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dodge JE, Kang YK, Beppu H, Lei H, Li E (2004) Histone H3‐K9 methyltransferase eset is essential for early development. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2478–2486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim J, Zhao H, Dan J, Kim S, Hardikar S, Hollowell D, Lin K, Lu Y, Takata Y, Shen J et al (2016) Maternal Setdb1 is required for meiotic progression and preimplantation development in mouse. PLoS Genet 12: e1005970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu S, Brind'Amour J, Karimi MM, Shirane K, Bogutz A, Lefebvre L, Sasaki H, Shinkai Y, Lorincz MC (2014) Setdb1 is required for germline development and silencing of H3K9me3‐marked endogenous retroviruses in primordial germ cells. Genes Dev 28: 2041–2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsui T, Leung D, Miyashita H, Maksakova IA, Miyachi H, Kimura H, Tachibana M, Lorincz MC, Shinkai Y (2010) Proviral silencing in embryonic stem cells requires the histone methyltransferase ESET. Nature 464: 927–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishimoto K, Kawamata N, Uchihara Y, Okubo M, Fujimoto R, Gotoh E, Kakinouchi K, Mizohata E, Hino N, Okada Y et al (2016) Ubiquitination of lysine 867 of the human SETDB1 protein upregulates its histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methyltransferase activity. PLoS ONE 11: e0165766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun L, Fang J (2016) E3‐independent constitutive monoubiquitination complements histone methyltransferase activity of SETDB1. Mol Cell 62: 958–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koch CM, Honemann‐Capito M, Egger‐Adam D, Wodarz A (2009) Windei, the Drosophila homolog of mAM/MCAF1, is an essential cofactor of the H3K9 methyl transferase dSETDB1/Eggless in germ line development. PLoS Genet 5: e1000644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seller CA, Cho CY, Ofarrell PH (2019) Rapid embryonic cell cycles defer the establishment of heterochromatin by Eggless/SetDB1 in Drosophila . Genes Dev 33: 403–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jurkowska RZ, Qin S, Kungulovski G, Tempel W, Liu Y, Bashtrykov P, Stiefelmaier J, Jurkowski TP, Kudithipudi S, Weirich S et al (2017) H3K14ac is linked to methylation of H3K9 by the triple tudor domain of SETDB1. Nat Commun 8: 2057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delaney CE, Methot SP, Guidi M, Katic I, Gasser SM, Padeken J (2019) Heterochromatic foci and transcriptional repression by an unstructured MET‐2/SETDB1 co‐factor LIN‐65. J Cell Biol 218: 820–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mutlu B, Chen HM, Moresco JJ, Orelo BD, Yang B, Gaspar JM, Keppler‐Ross S, Yates JR, Hall DH, Maine EM et al (2018) Regulated nuclear accumulation of a histone methyltransferase times the onset of heterochromatin formation in C. elegans embryos. Sci Adv 4: eaat6224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang H, An W, Cao R, Xia L, Erdjument‐Bromage H, Chatton B, Tempst P, Roeder RG, Zhang Y (2003) mAM facilitates conversion by ESET of dimethyl to trimethyl lysine 9 of histone H3 to cause transcriptional repression. Mol Cell 12: 475–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Timms RT, Tchasovnikarova IA, Antrobus R, Dougan G, Lehner PJ (2016) ATF7IP‐mediated stabilization of the histone methyltransferase SETDB1 is essential for heterochromatin formation by the hush complex. Cell Rep 17: 653–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhai B, Villén J, Beausoleil SA, Mintseris J, Gygi SP (2008) Phosphoproteome analysis of Drosophila melanogaster embryos. J Proteome Res 7: 1675–1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saito K, Inagaki S, Mituyama T, Kawamura Y, Ono Y, Sakota E, Kotani H, Asai K, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2009) A regulatory circuit for piwi by the large Maf gene traffic jam in Drosophila . Nature 461: 1296–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhao Q, Xie Y, Zheng Y, Jiang S, Liu W, Mu W, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Xue Y (2014) Ren J (2014) GPS‐SUMO: a tool for the prediction of sumoylation sites and SUMO‐interaction motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 42: W325–W330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sumiyoshi T, Sato K, Yamamoto H, Iwasaki YW, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2016) Loss of l(3)mbt leads to acquisition of the ping‐pong cycle in Drosophila ovarian somatic cells. Genes Dev 30: 1617–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kalderon D, Roberts BL, Richardson WD, Smith AE (1984) A short amino acid sequence able to specify nuclear location. Cell 39: 499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wen W, Meinkotht JL, Tsien RY, Taylor SS (1995) Identification of a signal for rapid export of proteins from the nucleus. Cell 82: 463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Tomita M, Yanagawa H (2009) Systematic identification of cell cycle‐dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10171–10176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Loyola A, Tagami H, Bonaldi T, Roche D, Quivy JP, Imhof A, Nakatani Y, Dent SYR, Almouzni G (2009) The HP1α–CAF1–SetDB1‐containing complex provides H3K9me1 for Suv39‐mediated K9me3 in pericentric heterochromatin. EMBO Rep 10: 769–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rivera C, Saavedra F, Alvarez F, Díaz‐Celis C, Ugalde V, Li J, Forné I, Gurard‐Levin ZA, Almouzni G, Imhof A et al (2015) Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 occurs during translation. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 9097–9106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guo J, Dai X, Laurent B, Zheng N, Gan W, Zhang J, Guo A, Yuan M, Liu P, Asara JM et al (2019) AKT methylation by SETDB1 promotes AKT kinase activity and oncogenic functions. Nat Cell Biol 21: 226–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang G, Long J, Gao Y, Zhang W, Han F, Xu C, Sun L, Yang SC, Lan J, Hou Z et al (2019) SETDB1‐mediated methylation of Akt promotes its K63‐linked ubiquitination and activation leading to tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 21: 214–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ichimura T, Watanabe S, Sakamoto Y, Aoto T, Fujita N, Nakao M (2005) Transcriptional repression and heterochromatin formation by MBD1 and MCAF/AM family proteins. J Biol Chem 280: 13928–13935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li H, Rauch T, Chen ZX, Szabó PE, Riggs AD, Pfeifer GP (2006) The histone methyltransferase SETDB1 and the DNA methyltransferase DNMT3A interact directly and localize to promoters silenced in cancer cells. J Biol Chem 281: 19489–19500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rowe HM, Jakobsson J, Mesnard D, Rougemont J, Reynard S, Aktas T, Maillard PV, Layard‐Liesching H, Verp S, Marquis J et al (2010) KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature 463: 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ceol CJ, Houvras Y, Jane‐Valbuena J, Bilodeau S, Orlando DA, Battisti V, Fritsch L, Lin WM, Hollmann TJ, Ferré F et al (2011) The histone methyltransferase SETDB1 is recurrently amplified in melanoma and accelerates its onset. Nature 471: 513–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsusaka T, Shimura C, Shinkai Y (2019) ATF7IP regulates SETDB1 nuclear localization and increases its ubiquitination. EMBO Rep 20: e48297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Murano K, Iwasaki YW, Ishizu H, Mashiko A, Shibuya A, Kondo S, Adachi S, Suzuki S, Saito K, Natsume T et al (2019) Nuclear RNA export factor variant initiates Piwi‐piRNA‐guided co‐transcriptional silencing. EMBO J 38: e102870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yashiro R, Murota Y, Nishida KM, Yamashiro H, Fujii K, Ogai A, Yamanaka S, Negishi L, Siomi H, Siomi MC (2018) Piwi nuclear localization and its regulatory mechanism in Drosophila ovarian somatic cells. Cell Rep 23: 3647–3657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sato K, Iwasaki YW, Shibuya A, Carninci P, Tsuchizawa Y, Ishizu H, Siomi MC, Siomi H (2015) Krimper enforces an antisense bias on piRNA pools by binding AGO3 in the Drosophila germline. Mol Cell 59: 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schindelin J, Arganda‐Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B et al (2012) Fiji: an open‐source platform for biological‐image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Han BW, Wang W, Zamore PD, Weng Z (2014) piPipes: a set of pipelines for piRNA and transposon analysis via small RNA‐seq, RNA‐seq, degradome‐ and CAGE‐seq, ChIP‐seq and genomic DNA sequencing. Bioinformatics 31: 593–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Data Availability Statement

Deep sequencing data sets have been deposited in the NCBI GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are available under accession number GEO: GSE128203.