Abstract

The federal government has proposed an end to HIV transmission in the United States by 2030. Although the United States has made substantial overall progress in the fight against HIV/AIDS, data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have raised concerns about widening, yet largely unrecognized, HIV infection disparities among Hispanic and Latino populations.

This commentary identifies underlying drivers of increasing new HIV infections among Hispanics/Latinos, discusses existing national efforts to fight HIV in Hispanic/Latino communities, and points to gaps in the federal response. Consideration of the underlying drivers of increased HIV incidence among Hispanics/Latinos is warranted to achieve the administration’s 2030 HIV/AIDS goals.

Specifically, the proposed reinforcement of national efforts to end the US HIV epidemic must include focused investment in four priority areas: (1) HIV stigma reduction in Hispanic/Latino communities, (2) the availability and accessibility of HIV treatment of HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos, (3) the development of behavioral interventions tailored to Hispanic/Latino populations, and (4) the engagement of Hispanic/Latino community leaders.

In his February 5, 2019, State of the Union Address, President Trump promised to reinforce national efforts to end the US HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030. However, the national public health agenda has neglected the accelerating HIV/AIDS crisis in Hispanic/Latino communities. Progress in the fight against HIV is reflected in aggregate data for the United States, but data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) raise alarming concerns about widening, yet largely unrecognized, HIV infection disparities among Hispanics/Latinos.1–3

THE INVISIBLE HIV CRISIS AMONG HISPANICS/LATINOS

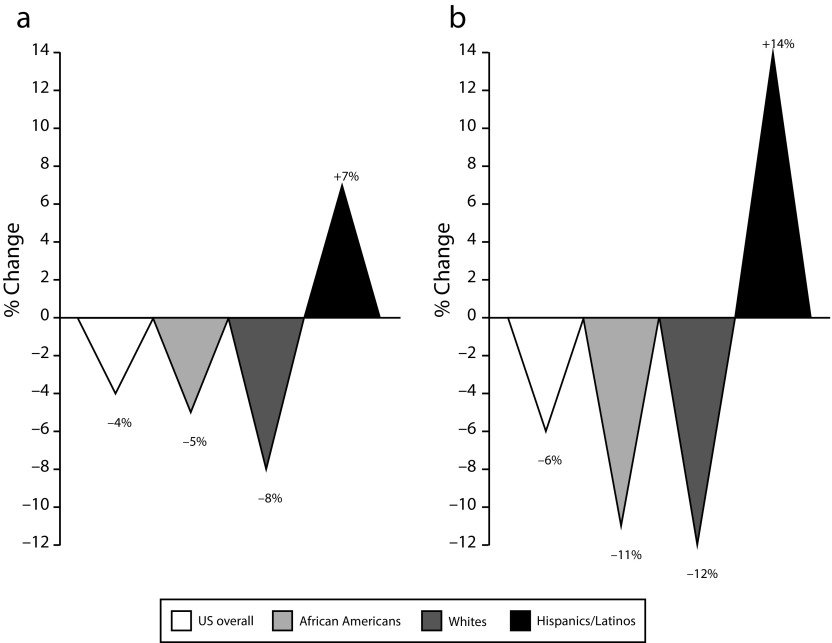

Although progress in reducing HIV incidence and new diagnoses has been achieved for specific Hispanic/Latino subpopulations, increases among key transmission and age groups reflect a largely unrecognized Hispanic/Latino HIV crisis.1–3 CDC estimates of HIV incidence suggest that the number of new HIV infections in Hispanic/Latino communities is escalating.1 Although estimated HIV incidence in the United States has declined overall by 6% since 2010, it has increased among Hispanic/Latino populations by 14% or more.1 Similarly, surveillance data show that the annual number of Hispanics/Latinos newly diagnosed with HIV has increased by 7% between 2012 and 2016, in contrast to overall annual new HIV diagnoses in the United States, which have decreased by 4% (Figure 1).2 The increase in estimated HIV incidence and new diagnoses among Hispanics/Latinos is best elucidated by considering the specific Hispanic/Latino populations most heavily affected by HIV/AIDS—namely, men who have sex with men (MSM; in particular, young Hispanic/Latino MSM), transgender Latina females, and recent Hispanic/Latino immigrants.

FIGURE 1—

Change, by Racial/Ethnic Groups, in (a) Annual New HIV Diagnoses, 2012–2016, and (b) Estimated Infections, 2010–2016: United States

Note. Overall increases in new HIV diagnoses and estimated infections among Hispanics/Latinos are driven by increases among Latino men who have sex with men (MSM).

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1,2

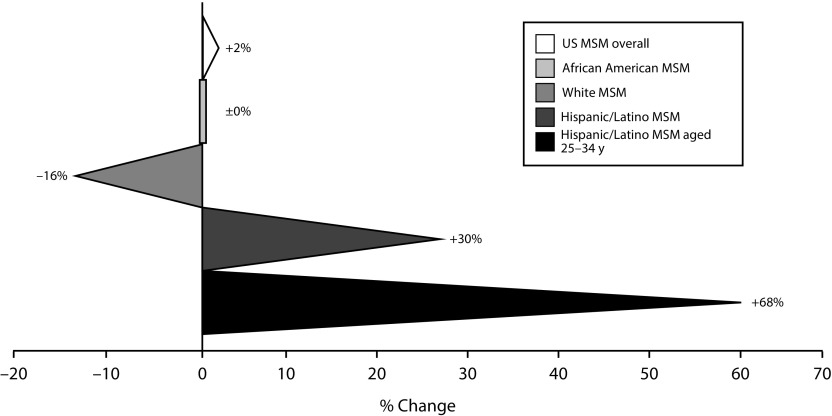

MSM represent the largest affected population in the current Hispanic/Latino HIV crisis, accounting for approximately 80% of estimated HIV incidence among Hispanics/Latinos.1 Alarmingly, since 2010, the estimated number of new annual HIV infections has increased by 30% for Hispanic/Latino MSM and, notably, by 68% for Hispanic/Latino MSM aged 25 to 34 years (Figure 2).1 Similarly, since 2012, annual new HIV diagnoses for young Hispanics/Latinos aged 13 to 24 years have remained constant, whereas overall new diagnoses for youths aged 13 to 24 years declined by 10% over the same period.3 Pronounced HIV disparity among transgender Latinas was reported in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.4 It is estimated that roughly one in four transgender Latinas is HIV positive, with estimates of HIV prevalence in the included studies ranging from 8% to 60%.4 In addition, individuals born outside the continental United States accounted for at least one in three new HIV diagnoses for Hispanics/Latinos in 2017,2 representing a frequently overlooked key population affected by the Hispanic/Latino HIV epidemic. Importantly, it has been suggested that the majority of foreign-born Hispanics/Latinos living with HIV acquired the infection in the United States.5 Recent Hispanic/Latino immigrants face several challenges related to language barriers, immigration status, differences between host culture and that of their country of origin, and distinct social norms regarding health care seeking and utilization, exacerbating their vulnerability to HIV infection and limiting their access to prevention and treatment services.

FIGURE 2—

Change in Estimated Annual New HIV Infections Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM): United States, 2010–2016

Note. Hispanic/Latino MSM aged 25 to 34 years had the largest increase in estimated annual new HIV infections of all groups reflected in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance data.

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1

Traditional HIV surveillance data prioritize the allocation of resources to key geographic areas in response to disproportionate disease burden. For example, CDC data demonstrate that four states (California, Texas, Florida, and New York) and Puerto Rico accounted for two thirds of new HIV diagnoses among Hispanics/Latinos in 2016.6 However, molecular surveillance methods have revealed that HIV transmission microepidemics affect Hispanic/Latino communities across all census regions of the United States, with an emphasis on 20 states in particular.7 HIV nucleotide sequence data indicated that individuals in 60 high-transmission clusters were disproportionately Hispanic/Latino, MSM, and aged younger than 30 years.7 Priority clusters identified by the CDC exposed up to 132 transmissions per 100 person-years—33 times the national average—with forward transmission primarily occurring via social, drug-using, or sexual networks.7 As a response to the nationwide Hispanic/Latino HIV crisis, Hispanic/Latino-specific state, local, and federal programs are warranted that consider the unique challenges faced by Hispanic/Latino populations born in the United States and abroad to reduce HIV incidence, morbidity, and mortality.

HIV PREVENTION AND TREATMENT DISPARITIES

The HIV care continuum is a useful framework for assessing the progress made in achieving national prevention and treatment goals. Unfortunately, racial and ethnic disparities persist.8–11 For example, compared with the general population, Hispanics/Latinos are less aware of their HIV-positive status,1 use less preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP),8,9 and receive HIV care at a significantly lower rate.10 More than half of all Hispanics/Latinos have never been tested for HIV,11 and Hispanics/Latinos are more likely to report never having been offered an HIV test compared with non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans.12 As a result of inadequate HIV testing, 17% of HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos are unaware of their status, a higher proportion than reported for HIV-positive non-Hispanic Whites and African Americans.1 It has also been shown that Hispanics/Latinos access PrEP and HIV treatment services at a disproportionately lower rate than other populations.8–10 Although it is estimated that Hispanics/Latinos had a 66% higher risk of acquiring HIV than the general population in 2016,1 PrEP uptake among at-risk Hispanics/Latinos remains low. According to CDC analyses, the use of PrEP was indicated for nearly 300 000 Hispanics/Latinos in 2015,9 but of these, only 3% filled PrEP prescriptions.9 Hispanics/Latinos account for more than one quarter of new HIV infections in the United States,1 but only 13% of PrEP users in 2016 were Hispanics/Latinos.8 Furthermore, only 60% of HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos received HIV care in 2015, approximately one in five of whom were not retained in care.10 As a consequence, current estimates suggest no more than 51% of all HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos in the United States are virally suppressed.10

RESPONDING TO DRIVERS OF THE EPIDEMIC

A number of significant factors contribute to unsatisfactory HIV prevention and treatment outcomes for Hispanics/Latinos. In a recent review, Levison et al. outlined major individual, meso-, and macro-barriers to Hispanic/Latino engagement in HIV services at each step of the care continuum.13 Individual barriers to Hispanic/Latino engagement included HIV-related stigma, knowledge gaps regarding HIV and HIV risk, language barriers, comorbid mental health conditions, and substance use.13 Meso-barriers included mistrust of health care systems, a lack of culturally appropriate services, and a lack of integration of HIV specialty care with multidisciplinary services, such as primary care, behavioral, and sexual and reproductive health care services.13 At the macro level, the most significant barrier was insurance-related access to health care.13 Hispanics/Latinos remain the most underinsured and uninsured racial/ethnic group in the United States.13

In recent years, numerous efforts have been made to halt the spread of HIV among Hispanic/Latino communities and to improve national HIV surveillance, prevention, and response. For example, the CDC has adopted a data-driven approach to allocate funding to areas and populations most affected by HIV, including jurisdictions with high rates of new HIV diagnoses for Hispanics/Latinos. In 2018, 45% of CDC funding for HIV surveillance and prevention awarded to state and local health departments was allocated to California, Texas, Florida, New York, and Puerto Rico, as these jurisdictions accounted for two thirds of new HIV diagnoses among Hispanics/Latinos.6,14 The CDC is expanding the use of molecular surveillance to detect high-transmission clusters across the country. From 2013 to 2017, only 27 jurisdictions were funded to report HIV genetic sequence data for molecular diagnostics and cluster detection to the CDC.7 However, from January 2018, HIV molecular cluster detection and response was implemented in all jurisdictions across the United States.7 As part of the HIV molecular cluster detection and response process, the CDC (and local health departments) is engaging in health alerts and communication campaigns, and it is employing interventions to promote viral suppression, targeted HIV testing, and PrEP referrals.

To an extent, CDC efforts have aimed to prevent HIV in communities of color, including Hispanic/Latino communities. The CDC has allocated funding for HIV prevention efforts to community-based organizations that work with key HIV populations, including young MSM and transgender individuals.15 The CDC also funds capacity-building assistance for organizations that serve at-risk and HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos in the United States and Puerto Rico.15 Finally, the CDC conducts bilingual awareness campaigns with national Hispanic/Latino organizations to increase the visibility of HIV prevention services in key populations, such as the Partnering and Communicating Together to Act Against AIDS initiative.15 Although these community-based efforts represent a significant investment, more federal programs are warranted to address the needs of at-risk and HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos.

ADDRESSING GAPS IN THE FEDERAL RESPONSE

There have been increasing efforts by national Hispanic/Latino organizations and leaders to place Hispanics/Latinos on the HIV agenda at the federal level. In 2018, the National Hispanic/Latinx Delegation on HIV/AIDS (the Delegation) began a community consensus-building process that drew on a collective effort by more than 100 organizations nationwide to develop an advocacy campaign designed to increase collaboration between Hispanic/Latino community leaders and the CDC in shaping public health efforts to contain the HIV epidemic. The Delegation relied on a four-step process modeled on principles described by the Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States16 to define national priorities for a response to the Hispanic/Latino HIV crisis and develop materials for communication with external constituencies (see Infographics A [English] and B [Spanish] and additional references, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, and the Invisible Crisis Video, available at https://vimeo.com/clafh/invisiblecrisis):

-

1.

The Delegation set up a steering committee that comprised Hispanic/Latino leaders from diverse geographic regions and relevant stakeholder sectors, including nonprofit HIV service organizations, advocacy groups, and university-based researchers;

-

2.

The steering committee engaged in an iterative process based on regular telephonic conferences to develop a draft consensus document on national priorities to reduce HIV in Hispanic/Latino communities;

-

3.

The draft document was circulated among the Delegation’s signatory organizations for feedback;

-

4.

Grassroots input was elicited via a Web-based national town hall.

In addition, the National Hispanic Medical Association facilitated a consensus-building meeting between the Delegation and the CDC that was initiated in August 2018 to establish open channels of communication and collaboration between federal and Hispanic/Latino community stakeholders.

PRIORITY AREAS FOR INCREASED NATIONAL EFFORTS

Priority areas for increased national efforts by the CDC and federal, state, and local partner agencies are considered in the following sections.

Reducing HIV Stigma

Stigma is a major barrier to Hispanic/Latino engagement in HIV services.13,17 Targeted efforts to increase community awareness and knowledge regarding HIV prevention and treatment have been shown to decrease stigma and increase HIV service utilization.18 Programs that normalize HIV prevention and treatment among at-risk and HIV-positive Hispanics/Latinos and their social and familial environments may reduce HIV stigma. Recently, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene launched a pilot project to increase the visibility of PrEP among Hispanics/Latinos residing in New York City using culturally appropriate social marketing messages.19 Similar social marketing campaigns to decrease HIV-related stigma in Hispanic/Latino communities at large, as opposed to targeting exclusively at-risk and HIV-positive individuals, are needed at national and local levels.

Enhancing Treatment Accessibility

Access to HIV treatment reduces HIV-related morbidity and mortality at the individual level and prevents forward HIV transmission. However, Hispanics/Latinos diagnosed with HIV have lower rates of care engagement than the national average.10 The $70 million funding increase for the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program—the largest system of care for HIV-positive individuals in the country—that is outlined in the presidential budget proposal for fiscal year 2020 represents a promising step into the right direction.20 However, the administration’s restrictive policies on civil liberties, particularly for immigrants and sexual- and gender-identity minorities, erode access to health and social services for key populations affected by the Hispanic/Latino HIV epidemic and do not align with the declared targets to reduce HIV prevention and treatment disparities.17,21 The prioritization of targeted programs that address Hispanic/Latino-specific barriers to engagement and retention in HIV care are warranted, including cost-free access to HIV treatment of undocumented immigrants and the promotion of culturally and linguistically competent HIV service delivery.

Developing Tailored Behavioral Interventions

The CDC allocates funding for the development and evaluation of HIV testing and prevention interventions tailored to the needs of Hispanic/Latino MSM15; however, more substantial support is required. To date, the CDC Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention does not include evidence-based behavioral interventions designed to improve linkage to HIV treatment, adherence to antiretroviral medication, or retention in HIV services that are tailored specifically to US Hispanic/Latino communities.15 Increased funding for researchers (including Hispanic/Latino researchers) to develop Hispanic/Latino-specific evidence-based interventions is necessary from the National Institutes of Health, CDC, Health Resources and Services Administration, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and other federal agencies.

Recognizing Community Diversity

The implementation of a standardized approach to HIV prevention and treatment among US Hispanics/Latinos is misplaced, as it does not take into account the diversity of this population. The effectiveness of a national response to the Hispanic/Latino HIV crisis depends on efforts that target the needs of affected populations, including MSM and trans- and cis-gender Latinas.22 Furthermore, cultural and socioeconomic differences within the US Hispanic/Latino community affect health outcomes and engagement in health care services, including HIV.23 For example, subethnic group, acculturation, and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics have been shown to be associated with differential outcomes across the HIV care continuum among Hispanics/Latinos.13 Therefore, collaboration between federal agencies and diverse Hispanic/Latino community leaders is urgently needed to shape national efforts directed at the specific needs of heterogeneous Hispanic/Latino constituencies.

WHY ENDING THE HISPANIC/LATINO HIV EPIDEMIC MATTERS

The sustained, widening, and largely unrecognized HIV disparity among US Hispanics/Latinos is a pressing public health emergency. Today, approximately 59 million Hispanics/Latinos in the United States—a number that is estimated to double by 2060—represent nearly one in five Americans and constitute the country’s largest and youngest minority group.24 Given that more than half of Hispanics/Latinos in the United States are younger than 30 years of age,24 it is particularly alarming that the number of annual new HIV diagnoses among adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 29 years is increasing nationally.2 It is important to note that US Hispanic/Latino population growth is largely fueled by birth rates above the national average, despite public and political debates on immigration. Today, the vast majority of Hispanics/Latinos hold US citizenship, and 66% are born in the United States.24 Given the significant proportion of the overall US population that is—and will be—Hispanic/Latino, failure to address gaps in the national response to the Hispanic/Latino HIV crisis has significant population-level implications for the fight against HIV/AIDS and the Trump administration’s goal to contain HIV transmission by 2030. As part of the recent reappraisal of the national strategy for HIV, renewed federal efforts to eliminate the US HIV/AIDS epidemic have focused on four key components: increased testing, improved treatment delivery, expanded access to PrEP, and interventions designed to interrupt chains of transmission.25 However, the proposed efforts need to go beyond a narrow focus on testing, biomedical prevention and treatment, and molecular surveillance to address long-standing HIV prevention and treatment-related Hispanic/Latino disparities. Crucially, consideration of the underlying drivers of increased HIV incidence among Hispanics/Latinos is warranted across health and social service sectors,16 along with focused investment in HIV awareness and culturally competent prevention and treatment service delivery, to achieve the Trump administration’s 2030 HIV/AIDS goals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We extend our appreciation to all members of the National Hispanic/Latinx Delegation on HIV/AIDS for their support in a national collaborative effort to scale up the fight against HIV in Hispanic/Latino communities in the United States. In addition, we thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention for their engagement with the National Hispanic/Latinx Delegation on HIV/AIDS.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report: Estimated HIV Incidence and Prevalence in the United States 2010–2016. Vol. 24(1). February 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-24-1.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2017. Vol. 29. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2017-vol-29.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States and 6 Dependent Areas, 2012–2017. Vol. 24(5). October 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-24-5.pdf. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- 4.Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM et al. Estimating the prevalence of HIV and sexual behaviors among the US transgender population: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2006–2017. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis AM, Hue S, Pasquale D et al. HIV transmission patterns among immigrant Latinos illuminated by the integration of phylogenetic and migration data. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015;31(10):973–980. doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHHSTP Atlas Plus. August 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/index.htm. Accessed March 12, 2019.

- 7.France AM, Panneer N, Ocfemia CB Rapidly growing HIV transmission clusters in the United States, 2013–2016. Talk presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 4–7, 2018; Boston, MA. Available at: http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/rapidly-growing-hiv-transmission-clusters-unitedstates-2013%E2%80%932016. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 8.Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(41):1147–1150. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Grey JA. By race/ethnicity, blacks have highest number needing PrEP in the United States, 2015. Talk presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 4–7, 2018; Boston, MA. Available at: http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/raceethnicity-blacks-have-highest-number-needing-prep-united-states-2015. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 10.National Center for HIV/AIDS. Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Outcomes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-prevention-and-care-outcomes-2016.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2019.

- 11.Norris T, Clarke TC, Schiller JS. Early release of selected estimates based on data from January–September 2018 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. March 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 12.Febo-Vazquez I, Copen CE, Daugherty J. Main reasons for never testing for HIV among women and men aged 15–44 in the United States, 2011–2015. National Health Statistics Reports. No. 107. January 2018. DHHS publication 2018-1250 CS287554. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr107.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 13.Levison JH, Levinson JK, Alegria M. A critical review and commentary on the challenges in engaging HIV-infected Latinos in the continuum of HIV care. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2500–2512. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV prevention with health departments. February 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-prevention-health-departments.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 15.McCree DH, Walker T, DiNenno E et al. A programmatic approach to address increasing HIV diagnoses among Hispanic/Latino MSM, 2010–2014. Prev Med. 2018;114:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Academies of Sciences. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017. Engineering, and Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowley JS, Bland SE. HIV Prevention in the United States: Bolstering Latinx Gay and Bisexual Men to Promote Health and Reduce HIV Transmission. Washington, DC: O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law; March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li AT, Fung KP, Maticka-Tyndale E, Wong JP. Effects of HIV stigma reduction interventions in diasporic communities: insights from the CHAMP study. AIDS Care. 2018;30(6):739–745. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1391982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelstein Z, Salcuni P, Sanderson M, Remch M, Meyers J. Inequities in awareness of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in a large, representative, population-based sample, New York City (NYC). Talk presented at: American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Expo; November 9–14, 2018; San Diego, CA.

- 20.US Dept of Health and Human Services. HHS budget in brief. March 2019. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fy-2020-budget-in-brief.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.El-Sadr W, Mayer KH, Rabkin M, Hodder SL. AIDS in America—back in the headlines at long last. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(21):1985–1987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1904113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covey J, Rosenthal-Stott HES, Howell SJ. A synthesis of meta-analytic evidence of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV/STIs. J Behav Med. 2016;39(3):371–385. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9714-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzales S, Sommers BD. Intra-ethnic coverage among Latinos and the effects of health reform. Health Serv Res. 2017;53(3):1373–1386. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. 2017. American Community Survey 1-year estimates. September 2018. Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2017/1-year.html. Accessed May 10, 2019.

- 25.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]