Abstract

This article focuses on the untapped, complicated, fragile, and fluid visual archives of the elite White surgeon Rudolph Matas, a large proportion of which was produced during the late 19th and early 20th century, a time when he was a resident at New Orleans’ Charity Hospital in Louisiana and a professor of general and clinical surgery at Tulane University’s Medical Department. The article’s main aim is to understand the role of visual materials in the production, uses, circulation, and impact of a form of knowledge that Matas termed “racial pathology.” A small but representative sample of visual materials from the Matas collection are placed in context and examined in order to make known this untold chapter from the life story of “one of the great pioneers” in American surgery. The article reveals that many of the photographs were most significant in having been produced and assembled in parallel with the making, publication, dissemination, reception, and use of Matas’ racialized medical research, in particular his influential 1896 pamphlet, The Surgical Peculiarities of the American Negro.

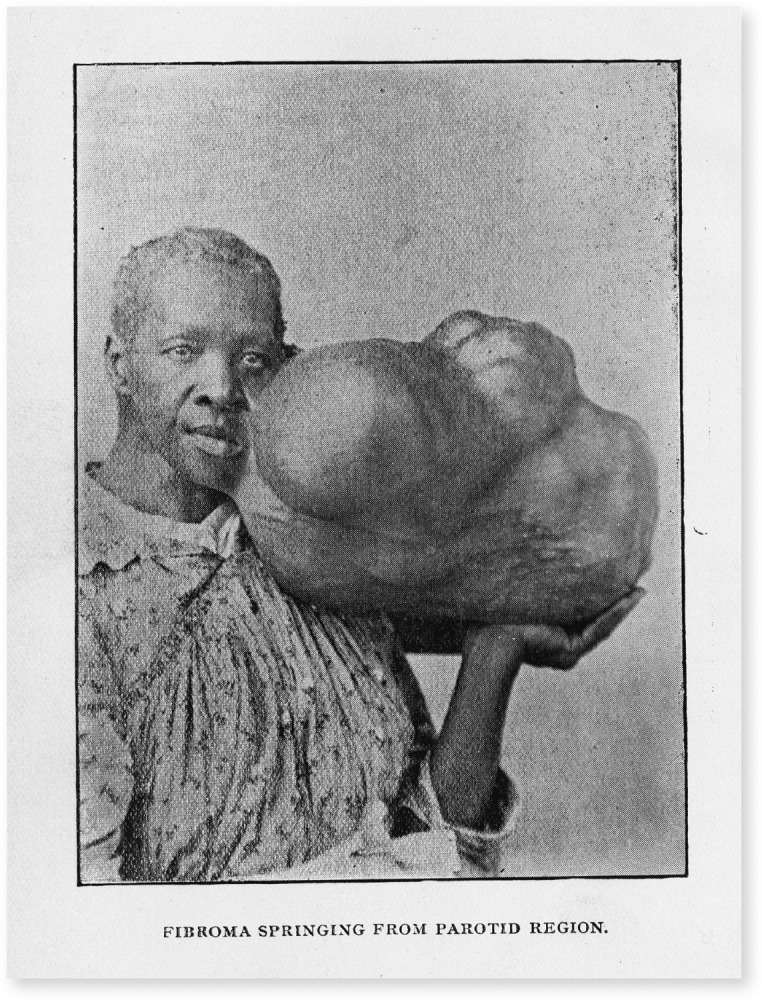

The afflicted woman in Figure 1 was a patient of one Dr J. W. Plunkett in Flora, Mississippi, who forwarded her photograph to Dr Rudolph Matas at Tulane University’s Medical Department in New Orleans, Louisiana, to be displayed as part of the Orleans Parish Medical Association’s routine “exhibition of specimens.”2 The woman’s image journeyed far and served many purposes. It was first published in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal’s report on the association’s monthly meeting, held on January 13, 1894, and depicts what the journal described as “a negress having an enormous fibroma growing from the left parotid region.”3 The photo-engraving, in part, exposes a large and misshapen mass, supported by the unnamed woman, while the accompanying caption—“fibroma springing from parotid region”—is typical of a style of pathological medical prose that focused on lesions and their formation (and usually ignored the patient). Disfigured by the massive tumor, and under the stress of posing with it for a photograph, the woman maintains her dignity before the camera.

FIGURE 1—

Unnamed Woman

Note. In keeping with its original presentation in medical journals and various medical settings, this photograph and those that follow have not been censored, but debates about the meanings, ethics, and proper treatment of historical medical photographs are vigorous and ongoing.1 Image reproduced with thanks to Mary C. Holt at the Rudolph Matas Library of the Health Sciences, Tulane University.

Source. Unknown photographer. “Proceedings of Societies: Exhibition of Specimens,” New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal XXI, no. 7 (January 1894): 585.

Shortly thereafter, the photograph served as the basis for an artist’s illustration in “The Surgical Peculiarities of the Negro,” Matas’ contribution to the multivolume System of Surgery (1895–1896), edited by surgeon Frederic S. Dennis, an influential textbook in medical education.4 The half-tone photograph was reproduced in George Gould and Walter Pyle’s Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine (1896), an encyclopedic compilation of extraordinary bodies, unusual growths, and uncommon case histories produced ostensibly as a work of medical reference, with a popular edition published in 1900. Much like a circus sideshow, this text was a site of human display that sought to appeal to the morbid curiosity of lay and medical readers.5 A copy of the image was also included in an album of medical photographs that belonged to Matas. To date, nothing further is known about the unnamed woman.

Although this is no ordinary portrait, as historians of medicine and photography—including Daniel Fox, Christopher Lawrence, and Larissa Heinrich—have shown, there is nothing uncommon about the burden of sickness it displays. It is a typical pathological photograph of the period and similar to images made, displayed, and circulated across Asia, Europe, and the United States.6 In terms of how it was used, it is mostly typical: as a diagnostic description, part of a record of cases and interventions, as a learned observation, a valuable form of professional and social currency, and as a trophy of sorts, with a human being framed as spectacle, intended to be of interest to both medical and popular audiences. Matas collected, displayed, shared, and used such photographic evidence to argue that there was a “ ‘special proclivity’ among the black population toward the development of fibroidal neoplasms” (benign tumors) in various localities of the body, and the visual materials in his archive and publications demonstrate a particular interest in such rare and sizable growths.7 The unnamed woman was not merely a proxy for the disease she was directed to display, but also offered powerful visual evidence to support a scientific research project that deepened notions of racial difference.8

The images that I use in this article are from the Matas collection’s complicated, fragile, and fluid visual archives, a significant proportion of which were produced during the late 19th and early 20th century, a time when he was a resident at Charity Hospital and a professor of general and clinical surgery at Tulane. As yet, no scholarly attention has been directed to this body of medical photographs. My article reveals that many of the images were most significant in having been produced and assembled in parallel with the making, publication, dissemination, reception and uses of Matas’ racialized research, a form of medical knowledge that Matas termed “racial pathology.” This is not a specialism for which Matas has been remembered as a “father” or “pioneer” by his biographers and memorialists to date. In fact, this is a key “missing chapter” from his life story. Official and physician-authored biographies have remembered and celebrated Matas for his work “in the development of local, regional and spinal anaesthesia and in the intravenous use of saline solutions and serums for the treatment of shock, haemorrhage, and collapse,” as well as “major contributions in the areas of thoracic, intestinal, and cranial surgery.” He was at the very pinnacle of the professional medical elite, and as the subtitle for Isidore Cohn’s biography of Matas made plain, most mid-20th-century medical professionals saw him as “one of the great pioneer surgeons.”9 Yet what these narratives omit, and what medical photographs in his archive reveal, is that the operative procedures for which Matas is best known, such as endoaneurysmorrhaphy (vascular surgery for the treatment of aneurysms), that prompted Sir William Osler to hail him as the “Father of Vascular Surgery” and the “Modern Antyllus,” were developed using Black human subjects at Charity.10 The main pathology captured and under scrutiny here, then, is that seen in the racial worldview and practices of elite White medical actors, which in Matas’ case crystallized in the making, publication, and dissemination of his influential essay “The Surgical Peculiarities of the Negro” and his pamphlet The Surgical Peculiarities of the American Negro (hereafter abbreviated SPAN).

By introducing and focusing on a small sample of medical photographs from the Matas archive, I aim to inscribe the presence of these vulnerable subjects into the record of a historical moment and experience that is largely dominated by comfortable, paternalistic, White-centric narratives fixated on the medical elite and celebratory visions of medical institutions, to begin to reveal otherwise hidden historical dimensions of the Black American health experience under racial segregation.11 The critical perspective and position of this article is influenced and informed by the work of visual cultures practitioner, scholar, and theorist Ariella Azoulay, and her approach to viewing and working with photographs depicting vulnerable human subjects who have suffered violence or some form of injury. In such cases, Azoulay argues, a viewing and an interpretation that begin to reconstruct the photographic situation, and the circumstances giving rise to suffering and injuries, become a “civic contribution,” or a duty of care toward dispossessed citizens, but decidedly not an act of empathy, guilt, or pity.12 In the case of the human subjects represented in the Matas visual archive, the civic responsibility and duty of care is clear, because one means by which these most vulnerable of citizens continue to be wronged and dispossessed is through their omission from histories of health and medicine under Jim Crow segregation.13

VISUALIZATIONS OF RACIALIZED RESEARCH

There are over 150 medical photographs in the Matas papers at Tulane’s Special Collections.14 The form of the photographs, as found in the archive, to some extent betrays the original functions of these images as working objects. First, there are many loose photographs, sometimes printed as multiples, which were used to identify the patients and record their diseases or injuries, as part of a larger case file. The Matas collection contains a small number of patient files from Charity, and attached to some of these records are photographs.15 These images might have functioned as objects of reference for hospital personnel, especially for conditions and illnesses that demanded close observation. If sufficiently “interesting” in pathological or surgical terms, some of these loose copies would have passed between colleagues on the same ward, elsewhere within the hospital, and across the city’s broader biomedical complex and community. The images often circulated more widely, in professional correspondence, to different cities, states, and nations, and in the drafts and proofs that eventually became medical publications. Some images were used in educational displays and professional presentations, at national or international conferences, and also for discussion and display at local, regional, and state society meetings—the very circumstances in which the photograph of the woman with the fibroma surfaced. Other loose images would have been deposited in the files of the pathology department, in the college medical museum, and in the collections of individual physicians like Matas. Furthermore, certain images would have been used in all of these contexts.16

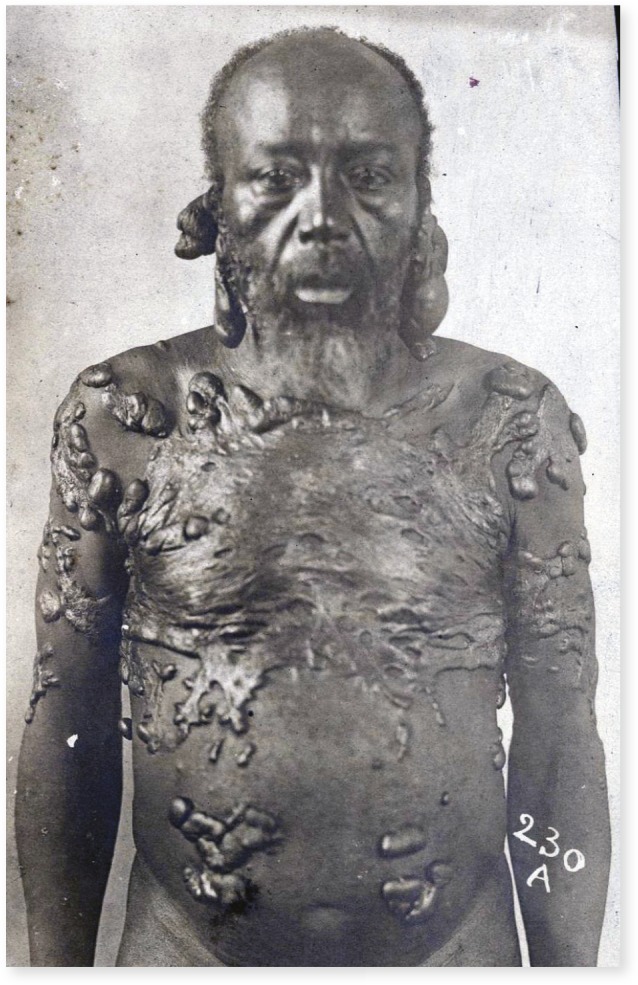

An overview of the album sample highlights patterns that provide a measure of the culture, ideas, society, and practices that shaped the images’ production and uses as they circulated between various sites and audiences. The album once contained at least 60 photographs. Fifty images remain, which include men, women, and children of various ages and ethnicities, as well as body parts, body fragments, and specimens. A clear majority of the patients depicted in this subsample are Black and male.17 This is characteristic of the typical broad patterns in the display and use of human research subjects throughout American medical history.18 The diseases in this subset of photographs illustrate a range of conditions that—as Jim Crow-era White medical scientists such as Matas and his Tulane colleagues argued—were peculiar to and more prevalent among Black subjects; these included syphilis, tuberculosis, keloids, fibromas, and elephantiasis. Brief handwritten captions provide some means of identifying the diseases depicted in many of the photos, but these are typically terse remarks and provide few (if any) details about the patients beyond age, gender, and hospital ward, with some images destined to remain a mystery (Figure 2).19

FIGURE 2—

An Unnamed Black Male Patient With What Matas Described in a Handwritten Pencil Note Below as “Cavernous Angioma of the Auricle After Ligation of the External Carotid”

Source. Unknown photographer. Box 43: Matas notebooks, scrapbooks, albums, and prayer books. Rudolph Matas papers, 1829–1960. Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library; Special Collections, Tulane University.20

Many of the photographs are scenes in which the patient’s fragility and vulnerability overwhelm any intended coding—be it clinical, pathological, or racial—diagnostic function, or formal reading.21 A partially naked patient with a chronic case of elephantiasis is among the most troubling of such photographs (Figure 3). Such images are a special category of patient record and raise important questions concerning issues of agency, consent, privacy, and appropriate use and display not only by historians of race, health, and medicine, but also by museum professionals and readers.22

FIGURE 3—

An Unnamed Black Male Patient With What Matas Described in a Handwritten Pencil Note Below as “Elephantiasis Arabum”

Source. Unknown photographer. Box 43: Matas notebooks, scrapbooks, albums, and prayer books. Rudolph Matas papers, 1829–1960. Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library; Special Collections, Tulane University.

Only one photo album remains in the Matas archive, but there may have been others—and many more photographs overall—as the collection has migrated, changed shape, and been displaced on several occasions in its institutional history. Changes in personnel, archival practices, and shifts in the sites of the collection have perpetuated the fluid nature of this sometimes incoherent and frustrating body of evidence, a situation further compounded by the multiple crises delivered by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 and the best efforts of Tulane’s archivists to salvage their collections in the face of disaster.23

“ONE OF THE GREAT PIONEERS” (OF RACIAL PATHOLOGY)

Rudolph Matas was celebrated and honored by the medical profession in a number of ways, including a sizable portfolio of painted and photographic portraits (Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).24 Delivered by an enslaved midwife, Matas (1860–1957) was born on a plantation near Bonnet Carre, St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana, to Spanish immigrant parents who worked in pharmacy and medicine.25 He was raised and educated in a culture of racialized medicine characterized by the commonplace American tradition of dissections and experimental surgeries performed on Black subjects.26 This legacy would prove to be influential and instructive for Matas, who went on to build a lucrative career and an international reputation substantially based on clinical observations and surgical encounters with poor Black patients in New Orleans’ Charity Hospital. The production of racialized medical research was shared among Tulane’s medical faculty and evident in numerous journal publications, the university’s curriculum, and teaching resources, including the school’s cadaver supply, the specimens deposited in its medical museums, and medical photographs, such as those in the Matas archive.27

Manuel, a 26-year-old “colored” field worker and Charity Hospital patient, for example, was used as an illustration of the successful surgical procedure for aneurysm developed by Matas (Figure B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).28 Matas enjoyed a long tenure as a visiting surgeon to Charity, from 1886 to 1922, and oversaw many hundreds—if not thousands—of “cases” that included those admitted to Ward 2, a segregated clinical space in Charity reserved for Black male patients. This role enabled Matas to hone and display his surgical expertise, and to develop his knowledge of pathology and related technical proficiencies, which included the use of photography and other means of visualization. A significant number of Matas’ reports to the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal, for example, featured unusual cases, new approaches, or “pioneer surgeries” undertaken at Charity, and many of these published case histories were illustrated.29 As it had for the teaching of anatomy and surgery in the mid-19th century, Charity provided a vast resource of clinical subjects and bodies for pathological and surgical inquiry, and built additional facilities (a new Dead House, Pathological Laboratory and Museum opened in 1884), hired specialist personnel, and bought new equipment—including photographic tools—to further medical research.30

In 1895 and 1896, Matas published the illustrated System of Surgery essay and a longer unillustrated pamphlet version, SPAN, based on 10 years of clinical practice and surgical interventions at Charity. In the opening section of SPAN, Matas positioned his work in the long tradition of Western scientific studies of racial differences, confirming and reinforcing what were then consensus White perceptions of Black “anatomical peculiarities” and “the lowly status of the negro in human evolution.”31 From Charity’s statistical data on the relative mortality of diseases, such as tuberculosis and syphilis, that showed Black patients dying at two and three times the rate of Whites, Matas drew the conclusion that “the colored race is degenerating.”32 These “degenerative tendencies,” he claimed, could be explained by

the influence of unfavorable hygienic surroundings . . . unfavorable social (including moral) environment . . . the causes which lead to a bad heredity, vice, dependency, and degradation . . . acting simultaneously upon an ethnologically inferior and passive race . . . struggling for existence with a superior, aggressive, and dominant population.33

Molded by the ideological and social context of Jim Crow segregation, Matas’ reading of Black health in New Orleans held no meaningful therapeutic value, blamed the incidence of disease on sufferers, and ignored the key determinants of poverty, inadequate diet, sanitation, education, and substandard housing.34

Although in broad agreement with the fundamental claims and politics of racial scientists and anthropologists, Matas saw “little or no surgical application” that could result from distinctions formulated through various measurements and comparisons of Black and White bodies. The bones of Blacks’ feet might be flatter and longer than those of Whites, and there might be more curve to the tibia, a flatter thorax, and “peculiarities” in the femur, clavicle, and scapula that give “a greater analogy with the simian skeleton than in the white race,” but Matas argued that none of these differences were of “surgical interest.”35 Furthermore, reflecting on a decade of dissection work in the Tulane University anatomical department, “covering the examination of the caecum and appendix of more than three hundred negro cadavers,” Matas stated that he found no evidence “that would give the appendix of the negro an ethnic character.”36

TROUBLING PORTRAITS OF RACIALIZED MEDICAL RESEARCH

Matas’ research on skin and tumor formations in Black patients has mostly been forgotten. These were aspects of surgery that Matas was particularly keen to develop, as he noted in the SPAN, a “curious and interesting field of inquiry . . . still waiting a pioneer explorer.”37 Yet since the earliest encounters with Africans, White Europeans had been fascinated with black skin, which led them to pose questions and to conduct dissections and comparative anatomical investigations, thus producing a continuous global harvest, accumulation, and exchange of specimens (including skulls, bones, and embryos, as well as skins and tumors).38 The various advantages of privileged access to poor Black patients at Charity were hard for Matas to ignore, and his carefully framed notion of a universal surgical body in SPAN was a useful strategy to advance broader personal, professional, and pecuniary interest in the “special anatomy and physiology” of Black skin “and its appendages.” Notwithstanding an array of racial prejudices, which included a long-standing and commonplace White belief that the average Black person displayed a “woful [sic] lack of hygiene,” the sanitary regime of Charity Hospital enabled Matas to declare a special interest in abnormal skin conditions, or “neoplastic formations,” such as keloids, sarcoma, and other malignant growths.39 This research program was bolstered by another persistent and widespread White cultural belief—in a diminished sensibility of the Black human “nervous system to pain and shock.” Matas believed that “this blunt sensibility”—in combination “with a more passive condition of the mind”—made “the negro a most favorable subject for all kinds of surgical treatment with or without preliminary anaesthesia.”40 Such a deep-seated White notion was of course profoundly disturbing for Black lives.

Study of the processes that underpinned development of diseases such as fibroma, elephantiasis, and keloid were, Matas argued, “a most fruitful” and legitimate line of inquiry for the “racial pathologist.” In a medical context, this research confirmed for Matas his “pathological axiom that fibroid processes are relatively more frequent in the dark races; so much more so, in fact, as to constitute a racial peculiarity.”41 Matas’ investment in racial differences, however, also had clear ideological dimensions, as his semantic neologism and scientific specialism were formulated at a historical moment when negative stereotyping and surveillance of Black bodies greatly intensified, because of real and perceived threats and challenges to White hegemony. Supported by medical and sociological data, the era’s “negro problem” construct sought to weaponize notions of Black inferiority and deviance.42 In New Orleans, for example, diseases such as syphilis, leprosy, and tuberculosis were racialized and blamed on the degraded morality of Black citizens.43 In this context, Matas’ statistically and visually informed research on “racial pathology” only deepened and extended such damning portraits of Black health.

Presenting the comparative statistics of diseases such as elephantiasis, fibroma, and keloid, Matas acknowledged the limitations of his evidence. The overall number of cases was low, and in some categories of tumor—such as osteoma, enchondroma, and myxoma—there was insufficient incidence to “draw useful comparisons.”44 Statistics resonated well with educated medical elites, but in the late 19th century physicians like Matas recognized and embraced the potential of photography to evidence and reinforce arguments, reach new audiences, and develop reputations. The large number of growths and tumors captured in Matas’ visual archive highlights the value of medical photographs in the confirmation, elaboration, presentation, and circulation of his argument about Black racial distinctiveness. Photographs seemed to provide objective diagnostic evidence of clinically identified racial pathologies, with otherwise mutable appearances of various conditions and diseases fixed in a medium that readily facilitated close observational analysis, categorization, comparison, and exchange.45

On the reverse of Figure 4, one of four separate three-quarter-body profile photographic views of the same late-middle-aged Black patient, Matas wrote the words, “Beautiful case of keloids”—one of several pathological skin conditions, including elephantiasis, tuberculosis, and syphilis, that Matas argued were either distinctive among Black people or to which they were particularly susceptible.46 The photo ensemble bears close resemblance to police photography, with the characteristic flattened front-and-side profile poses of the “mug-shot.”47 It also bears the institutional stamp of its production in other ways, seen in the Pathology Department code inscribed on the photo’s surface and across the patient’s torso. Not just an identifying mark, but also a claim of ownership, an intellectual patent number. The photograph circulated in correspondence with Matas’ professional colleagues and is included in his album.48 In all likelihood, the image was used by Matas in various pedagogical contexts, and perhaps formed part of a sequence of slides in one of his favored lantern-slide clinical recitations, and part of the evidence base in development and promotion of his SPAN pamphlet and the “Surgical Peculiarities of the Negro” essay for the Dennis textbook. The look and posture in this photograph are suggestive of a man resigned to compulsory visibility, tolerance of intrusive examinations, and endurance of painful interventions.

FIGURE 4—

An Unnamed Male

Note. In a note below the image, Matas wrote: “Double keloids involving lobules of ears (non-cicatricial) illustrating the characteristic tendency in the negro-race to connective tissue hypertrophies.”

Source. Unknown photographer. Box 43: Matas notebooks, scrapbooks, albums, and prayer books. Rudolph Matas papers, 1829–1960. Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library; Special Collections, Tulane University.

Keloids were a particular source of fascination for Matas. Although Black patients rarely sought treatment of this condition at Charity, nor elsewhere in the New Orleans biomedical complex, Matas claimed that there was an “extraordinary preponderance of this condition in the colored race.” Although he noted that just 10 cases of patients with this condition were recorded at Charity between 1884 and 1893—eight Blacks and two Whites—Matas concluded that “keloid is about nine times more frequent in the negro than in the white.” Yet in the hospital context, Matas observed, it was the case that “only exaggerated and extreme cases” of “traumatic origin” presented. Rarity and peculiarity presented an irresistible challenge to a surgeon who had “tried on various occasions to remove keloids by total extirpation,” but “totally failed” to prevent the reappearance of the condition. Indeed, Matas’ account of experimental interventions indicated that surgical interference was harmful and caused keloidal tumors to spread:

In one case I decided to excise a small keloid and to cover the raw surface with Thiersch grafts; in another I removed two square inches of keloidal scar and substituted in its stead an exact equivalent of entirely healthy skin (Wolfe graft). No sutures were used; exact approximation was maintained. In both cases the grafts were taken from the patients themselves. In both the immediate results were perfectly satisfactory, but in both the keloid recurred not only in situ, but in the distant surfaces from which the grafts had been taken.49

The unnamed man in Figure 4 was used to develop, evidence, and disseminate Matas’ racial scientific theories, but he may also be the subject who experienced this failed surgical experiment at Charity.

IMAGES OF SUFFERING: PURPOSE AND PRESENCE

What has been ignored in official biographies of Matas are his contributions to racial science, most specifically the field that he termed “racial pathology,” recognition of the role played by Black patients upon whom he “pioneered” his surgeries, and his use of photography as a method of defining, displaying, and circulating notions of alleged racial diseases and degeneration. The world into which Matas was born, educated, and practiced was deeply racist, and he took full advantage of a professional culture and society based on racist ideology and sustained by often violent racial practices. These salient facts were not included in the celebratory accounts of his life and career.50

In four of the photographic examples included in this article, the close framing of a pathological condition visible through and beneath the skin—the ultimate marker for racial scientists and “everyday racists” alike—reinforced the notion of diseased Black subjects as profoundly “other” and “degenerate,” and drew attention to the value of these cases as medical research opportunities, curiosities readily transformed into legitimate objects of scientific observation, rumination, and experimentation. I not only argue that medical photography functioned as a powerful race-making tool in the era of Jim Crow, but I demonstrate that such images also captured, legitimated, and enabled an ideologically driven and experimental racialized medical research agenda. As other visual documents in Matas’ archive reveal, many of the test subjects for Matas’ key surgical breakthroughs and notions of “racial pathology” discussed in SPAN were developed using the patients he encountered at Charity, especially the Black men housed on the hospital’s racially segregated Ward 2.

Matas’ writings, visualizations, and surgical interventions at Charity and Tulane fit into a long tradition of racialized clinical research and human experimentation in New Orleans—activities that were always routine and widespread in American medical institutions, such as city hospitals—and which saw a decided upsurge well before the Tuskegee Syphilis Study was initiated.51 Furthermore, in one of the few fragments of scholarly commentary on Matas’ SPAN, medical historian David McBride drew attention to uses and effects of this pamphlet, which he described as a standard reference “for medical and sociological research through World War I postulating race distinctions as the basis for the black–white health discrepancy,” and it remained influential in medical research down to the 1930s and beyond.52

Medical photographs such as those included in this article played a key role in deepening racial stereotypes and circulated warped notions about Black bodies and Black health. Today, these images and Matas’ SPAN serve as stark reminders of discredited notions of racial difference and racialized diseases that were once commonplace in medical science and clinical practice. Read in context and against the grain of their intended purpose, these sources can be used as a form of social healing, to help reconstruct a fuller and more sensitive portrait of Black health and the Black patient experience in the era of Jim Crow, and restore the presence and the personhood of these human subjects to the historical record.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The initial research for this article was funded by a Leverhulme Research Trust Fellowship (RF-2015-050).

I thank Connie Z. Atkinson, Sue Currell, Mary J. Holt, Sally Sheard, Kathryn Smith, and Mike Tadman for their assistance, comments on related drafts, and general encouragement. I also thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their challenging and valuable comments and support.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author reports no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

See also Kropf, p. 16.

ENDNOTES

- 1.For a sustained and nuanced consideration of these concerns and issues (and their history), see Mieneke te Hennepe, “Private Portraits or Suffering on Stage: Curating Clinical Photographic Collections in the Museum Context. doi: 10.15180/160503. Science Museum Group Journal (Spring 2016), (accessed March 7, 2019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flora is a small town in Madison County, Mississippi (to the northwest of Jackson) that had a population of 228 in 1890.

- 3. “Proceedings of Societies: Exhibition of Specimens,” New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal XXI, no. 8 (1894): 585. The parotid is a major salivary gland, located just in front of the ear.

- 4. Rudolph Matas, “The Surgical Peculiarities of the Negro,” in Frederic S. Dennis, ed., System of Surgery, Vol. IV, Tumors (New York, NY, and Philadelphia, PA: Lea Brothers & Co., 1896); illustration appears as Fig. 416 on page 858.

- 5.Gould G.M., Pyle W.L. Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1896. p. 767. The book was published in London in 1898 (by the Rebman Publishing Co.), and the American popular edition followed in 1900. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel M. Photographing Medicine: Images and Power in Britain and America Since 1840. New York, NY: Greenwood Press; 1988. Fox and Christopher Lawrence. Larissa N. Heinrich, The Afterlife of Images: Translating the Pathological Body Between China and the West (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matas Rudolph. For example. New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal. Report of a Case of Molluscum Fibrosum Pendulum Weighing Thirteen Pounds. (May 1893), 843. Box 43: Matas notebooks, scrapbooks, albums, and prayer books. Rudolph Matas papers, 1829–1960; Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library; Special Collections, Tulane University. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Various forms of technology have been used by scientists to explore—and argue for—perceived racial differences. For a key example of this in American history, see Lundy Braun, Breathing Race Into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer From Plantation to Genetics (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

- 9.Duffy John, Matas Rudolph. In: American National Biography. Carnes Mark C., Garraty John A., editors. Vol. 15. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. Isidore Cohn (with Hermann B. Deutsch), Rudolph Matas: A Biography of One of the Great Pioneers in Surgery (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1960) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tulane University’s Contributions to Health Sciences Research and Education: A Guide: Dr. Rudolph Matas. Rudolph Matas Library of the Health Sciences, Tulane University Libraries, http://libguides.tulane.edu/famousalumni/Rmatas (accessed April 16, 2019)

- 11. This article precedes a more extensive consideration of a wider range of medical photographs from the Matas archive. See Kenny, Before Tuskegee: Racism, Power and the Culture of Medicine Under Slavery and Segregation, In Press.

- 12.Azoulay A. The Civil Contract of Photography. New York, NY: Zone Books; 2008. pp. 11–25. (especially 14–16) and 85–136. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Histories of Charity Hospital have concentrated on the institution’s administrative and financial past, the work and lives of the physicians, and the politics that surrounded the hospital. Patients, especially Black patients, are barely mentioned. See, for example, John Salvaggio, New Orleans’ Charity Hospital: A Story of Physicians, Politics and Poverty (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1992).

- 14.Tansey Eira Rudolph Matas Papers. 1829–1960” [collection overview], Louisiana Research Collection, Howard-Tilton Memorial Library; Special Collections, Tulane University, https://specialcollections.tulane.edu/archon/index.php?p=collections/findingaid&id=200&q=Matas&rootcontentid=66353#id66353 (accessed August 23, 2019)

- 15. An example are the patient records of John Gice, a 40-year-old Black barber admitted to Charity Hospital on May 1, 1912, diagnosed, by visiting physician Herbert Gessner, with an arterio-venous aneurysm of the carotid artery and autopsied on May 12, the postmortem diagnosis cause of death recorded as chronic coronary disease. Matas Collection, Box 11: Medical practices, clinical histories, 1881–1917, Folder 8, Charity Hospital cases, 1912.

- 16. On the varied uses of medical photographs, see M. Clark, Syphilis, Skin, and Subjectivity: Historical Clinical Photographs in the Saint Surgical Pathology Collection [unpublished MS thesis] (Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University, 2017), especially 11–24; Lukas Engelmann, “Photographing AIDS: On Capturing a Disease in Pictures of People With AIDS,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 90, no. 2 (2016), 250–278, especially 260–266; Fox and Lawrence, Photographing Medicine, 5–13 and 41–54; and Mark Jackson, “Images of Deviance: Visual Representations of Mental Defectives in Early Twentieth-Century Medical Texts,” British Journal of the History of Science 28, no. 3 (1995): 319–337.

- 17. There are 37 photographs of Black subjects in the photo album (29 adult males, four adult females, and four male children); 11 White subjects (eight adult males, two adult females, and one male child); one adult male Chinese subject, and one specimen of unknown ethnic origin. Sixteen of the Black subjects are noted as having been patients on Ward 2 at Charity.

- 18. See, for example, Allen M. Hornblum, Acres of Skin: Human Experiments at Holmesburg Prison (New York, NY: Routledge, 1998); Susan M. Reverby, Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); and Harriet A. Washington, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans From Colonial Times to the Present (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2006).

- 19. Fox and Lawrence rightly describe images like Figure 2 as “ambiguous documents”; see Photographing Medicine, p. 10.

- 20.Matas published an article on his treatment of this condition, with the subject described as F.B., a German American, aged 32; “Large cavernous angioma, involving the integument of an entire auricle successfully treated by dissection, free resection of diseased tissue, and ligation of the afferent trunks in situ by a special method. The Medical News 61. 1892;(26)(December 24):701–705. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Many scholars have addressed this issue in relation to different types of photographs, including Azoulay and te Hennepe, but perhaps most famously Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others (London, UK: Penguin, 2003).

- 22. I. Berle, “Clinical Photography and Patient Rights: The Need for Orthopraxy,” Journal of Medical Ethics 34 (2008): 89–92; David Bryson, “Current Issues: Consent for Clinical Photography,” Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine 36, no. 2 (June 2013): 62–63; Cesar Palacios-Gonzalez, “The Ethics of Clinical Photography and Social Media,” Medical Health Care and Philosophy 18, no. 1 (2015): 63–70; Catherine K. Lau, Hagen H.A. Schumacher, and Michael S. Irwin, “Patients’ Perception of Medical Photography,” Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 63 (2010): 507–511; and te Hennepe, “Private Portraits.”.

- 23.Lowry J., editor. Displaced Archives. London, UK: Routledge; 2017. On the theme and contested definitions of “displaced” and “migrated” archives. especially 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24. A five-page Appendix to Cohn’s biography—itself quite a memorial—lists Matas’ various honorary awards. Cohn and Deutsch, Rudolph Matas, 417–421.

- 25. Duffy, “Rudolph Matas.” Narciso, Rudoph’s father, was the employee of Norbert Loque, a wealthy sugar planter who provided the Matas family with “a comfortable house and two slaves to tend it, in addition to paying an impressive salary.” Biographer and former pupil of Matas, Isidore Cohn, speculated that for Narciso, the medical opportunities presented by Loque’s enslaved labor force far “outweighed even the monetary consideration.” Cohn and Deutsch, Rudolph Matas.

- 26. Between 1820 and 1825, in the neighboring town of Donaldsville, Francois Marie Prevost forged a reputation as a “pioneer” doctor and performed what were reputed to be the first Caesarean sections in Louisiana on at least two enslaved females. Marie Jenkins Schwartz has noted that these surgeries were dangerous for both the enslaved mothers and the infants, while free White women could readily decline experimental obstetric procedures. Marie Jenkins Schwartz, Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 164–165, and John Duffy, ed., The Rudolph Matas History of Medicine in Louisiana, Vol. 2 (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1958), 68, 72–74, 296–297.

- 27.One of those most influenced by Matas’ racialized research was his biographer, Cohn, who published his own intervention in the field of “negro medicine”—based on observations and statistics harvested from and surgical interventions enacted at Charity—in 1935 and 1938. Isidore Cohn, “Thyroid Disease in the Negro,” The Southern Surgeon 4 (December 1935): 416–421; and Cohn, “Carcinoma of the Breast in the Negro. Annals of Surgery 107. (May 1938):716–732. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193805000-00009. See also the work of Robert Bennett Bean and Edmond Souchon at Charity and Tulane in this same era. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. A photograph that appeared on the front page of the weekly magazine Saturday Review in August 1960 captured Matas demonstrating his use of illustrated educational display boards.

- 29. Matas, “Report of a Case of Patient From Whose Tissue Three Larvae of a Species of Dermatobia [human botfly] Were Removed,” New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal (NOMSJ)15 (September 1887): 161–179; “Extensive Syphilitic Necrosis [death of cells by self-digestion] of the Bone of the Nose” NOMSJ 16 (October 1888): 298–301; “Report of a Case of Thyroidectomy [surgical removal of the thyroid],” NOMSJ 16 (March 1889): 662–693; “Partial Gigantism of Right Foot and Leg, With Megalosyndactylism [large and fused digits],” NOMSJ 66, no. 10 (April 1914): 741. Matas made over 140 contributions to the NOMSJ, the majority before 1915 when he was the journal’s editor.

- 30.Fossier A.E. The Charity Hospital of Louisiana. New Orleans, LA: American Printing Co., Ltd.; 1923. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matas, SPAN, 13. In addition to other key works referenced in this article, for discussion and evidence of over 200 years of scientific studies of race in the United States, see Evelyn M. Hammonds and Rebecca M. Herzig, eds., The Nature of Difference: Sciences of Race in the United States From Jefferson to Genomics (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008).

- 32. See the 1910–1914 Report of the Board of Administrators of the Charity Hospital to the General Assembly of the State of Louisiana (New Orleans, LA: Charity Hospital of New Orleans), available at Tulane University Digital Library, https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane:p15140coll25 (accessed October 1, 2018); Matas, SPAN, 125.

- 33. Ibid.

- 34. For discussion of related studies arguing for “a degeneration in the Negro population,” such as Frederick L. Hoffman’s Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro (also published in 1896), see John S. Haller Jr., Outcasts From Evolution: Scientific Attitudes of Racial Inferiority, 1859–1900 (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995 [originally published 1971]), 60–68; and Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 35–87.

- 35. Matas, SPAN, 13–17.

- 36. On bioarchaeological evidence of the industrial scale of dissection work at Charity, see Christine L. Halling and Ryan M. Seidemann, “Structural Violence in New Orleans: Skeletal Evidence From Charity Hospital’s Cemeteries, 1847–1929,” in Kenneth C. Nystrom, ed., The Bioarchaeology of Dissection and Autopsy in the United States (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2017); for visual and other evidence of racialized dissection and anatomical work at Tulane, see Stephen C. Kenny, “ ‘Specimens Calculated to Shock the Soundest Sleeper’: Deep Layers of Anatomical Racism Circulated On-Board the Louisiana Health Exhibit Train,” in Kaat Wils, Raf de Bont, and Sokhieng Au, eds., Bodies Beyond Borders: Moving Anatomies, 1750–1950 (Leuven, Belgium; Leuven University Press, 2017); Matas, SPAN, 21.

- 37. Matas, SPAN, 24.

- 38. Historian Cristina Malcolmson traces such experiments and uses of the Black body—in particular scientific curiosity about Black skin—back to the early modern colonial era and the formation of the Royal Society. See Studies of Skin Color in the Early Royal Society: Boyle, Cavendish, Swift (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013). See also Mieneke te Hennepe, Depicting Skin: Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Medicine [unpublished PhD thesis] (Universitiet Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2007); and Jonathan Reinarz and Kevin Seina, eds., A Medical History of Skin: Scratching the Surface (London, UK: Routledge, 2016). On the long-running global harvest and collection of African bodies and specimens for scientific research, see, for example, Ann Fabian, The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010); Marieke Hendriksen, Elegant Anatomy: The Eighteenth-Century Leiden Anatomical Collections (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2014), especially chapter 6, “Colonial Bodies: Collecting the Exotic Other”; and Samuel J. Redman, Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

- 39. Matas, SPAN, 24; Keloids are a dermal injury, characterized by an overgrowth of scar tissue, which some medical researchers continue to explain as a result of genetic or “racial variations.” See, for example, J.P. Andrews, J. Marttala, E. Macarak, J. Rosenbloom, and J. Uitto, “Keloids: The Paradigm of Skin Fibrosis—Pathomechanism and Treatment,” Matrix Biology 51 (2016): 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40. Matas, SPAN, 24, 25. For the history and legacy of this medical stereotype, see Martin S. Pernick, A Calculus of Suffering: Pain, Professionalism, and Anesthesia in Nineteenth-Century America (New York, NY: Columbia University, 1985), especially chapter 7, pp. 154–157; see also John Hoberman, Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012), 93–98.

- 41. Matas, SPAN, 74.

- 42. On professional medicine’s reinvention of the “negro problem” in the era of Jim Crow segregation, see, for example, Haller, Outcasts from Evolution, especially chapter 2; Susan Reverby, Examining Tuskegee: The Infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009); and Samuel Roberts, Infectious Fear: Politics, Disease, and the Health Effects of Segregation (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- 43.Marcia G. Gaudet. Carville: Remembering Leprosy in America. Jackson, MS: University of Mississippi; 2004. Zachary Gussow, Leprosy, Racism, and Public Health: Social Policy in Chronic Disease Control (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1989); and Amy R. Sumpter, “Idylls of the Piney Woods: Health and Race in Southeastern Louisiana, 1878–1956,” Journal of Cultural Geography 27, no. 2 (2010): 177–202, especially 191–193. [Google Scholar]

- 44. All conditions that Matas noted were “characterized by an excessive proliferation of connective-tissue cells” or “hyperplasia” in “the derm and subcutaneous tissue.” Matas, SPAN, 74–77.

- 45. See Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, “The Image of Objectivity,” Representations 40 (Fall 1992): 111–113; John Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essay on Photographies and Histories (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 60–65; Gabriela Zamarano, “Traitorous Physiognomy: Photography and the Racialization of Bolivian Indians by the Crequi-Montfort Expedition (1903),” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 16, no. 2 (2011): 425–451.

- 46. Perhaps Matas’ description of the patient as a “beautiful case” was an ironic attempt at humor, an “in joke” for the benefit of fellow medical professionals, but it might also be seen as a difference-making strategy, with the “case” (or the “type”) functioning as a racial, class-based, and ableist code for the “degenerate.” Such comments can be dismissed as banter, but are a measure of how Matas viewed his encounter with this patient.

- 47. The standardized Bertillon mug shot (front and profile) was a relatively new phenomenon in the 1890s and early 1900s. Medical and criminological photography shared a rhetorical commitment to photographic objectivity, and a propensity to objectify the photographic subject. For further background, see Tagg, The Burden of Representation, especially 66–102. For the New Orleans Police Department’s use of “mug-shots” in these same years, see Emily Epstein Landau, Spectacular Wickedness: Sex, Race, and Memory in Storyville, New Orleans (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2013).

- 48. Photographs of two different male patients with keloids were included in the album sample; comments beneath indicate that Matas attended them on the racially segregated Ward 2 at Charity. Box 43: Matas notebooks, scrapbooks, albums, and prayer books. Rudolph Matas papers, 1829–1960.

- 49. Matas, SPAN, 79, 80, 81.

- 50. Despite, for example, Matas’ correspondence with and admiration for the work of Frederic Hoffman, author of Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro (1896) and an invited contributor to the Matas Birthday Volume: A Collection of Surgical Essays: Written in Honor of Rudolph Matas (New York, NY: Paul B. Hoeber, 1931).

- 51. For other early 20th-century American medical experiments, see Susan E. Lederer, Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America Before the Second World War (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

- 52.McBride David. From TB to AIDS: Epidemics Among Urban Blacks Since 1900. Vol. 16. Albany, NY: State University Press of New York; 1991. p. 182. [Google Scholar]