Concerns about the purported “skills gap” (a mismatch between the skills workers have and the skills prospective employers want and need) in the United States are widespread. Young people are at the epicenter of debates about the preparedness of the emerging labor force to compete in a dynamic, global economy and are the focus of national efforts to promote skills-based training, apprenticeships, and jobs.1

Although formal employment has benefits for young people,2 it also has risks.2–4 Nearly every minute, a worker aged 15 to 24 years in the United States is injured (http://bit.ly/2ovHhCj). This vulnerable population experiences a rate of occupational-related injury (treated in hospital emergency departments) that is 1.6 times the injury rate of adult workers (aged 25–44 y). Data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, indicate that 2349 adolescents aged 15 to 17 years and young adults aged 18 to 24 years died at work during the 2011 through 2017 period.

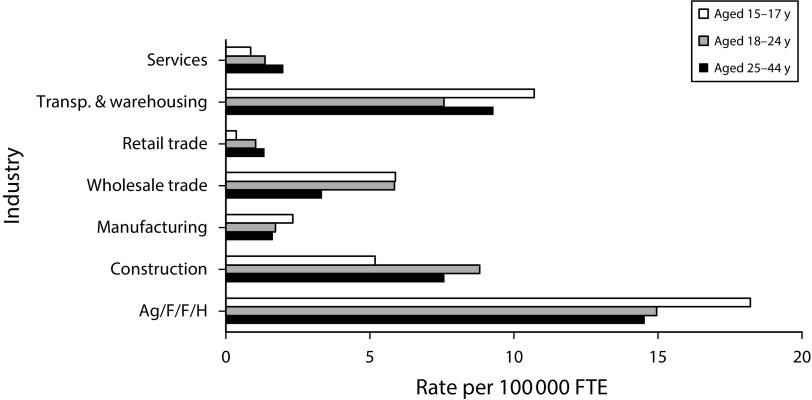

Work for young people in certain industries remains particularly dangerous. As indicated in Figure 1, during 2011 through 2017, adolescent and young adult workers experienced higher fatality rates (compared with adult workers) across multiple sectors. For adolescent workers, these incidents occur despite state and federal child labor laws enacted to protect youths younger than 18 years from performing hazardous work (http://bit.ly/2n5pu4D). Research suggests that violations of child labor regulations are common3,4 and create dangerous conditions that contribute to young worker deaths.4 Exposure to physical hazards and dangerous tasks, unsafe environments, inexperience, and lack of supervision and high-quality safety training are factors that contribute to young worker morbidity and mortality.2–4

FIGURE 1—

Occupational Fatality Rates by Selected Age Group and Industry Sector: United States, 2011–2017

Note. Ag/F/F/H = agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting; FTE = full-time equivalent; Transp. = transportation. Of deaths that occurred in the broader sector of Ag/F/F/H, 65% occurred in agricultural production. By age group, the percentages of deaths in agricultural production were 81% for workers 15–17 years, 59% for workers 18–24 years, and 55% for workers 25–44 years. Work-related fatality rates increase beginning at 45 years, thus limiting the analysis to workers 25–44 years allows a rate comparison with workers who more closely resemble young people in terms of physical stature.

Source. Fatal injury rates were generated by National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health researchers with restricted access to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) microdata and BLS Current Population Survey data; additional information at www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm and www.bls.gov/cps/home.htm. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of BLS.

Employers are responsible for maintaining safe and healthy workplaces and delivering job-related safety training. However, before entering the workforce, young people should be equipped with occupational safety and health competencies that provide a foundation on which job-specific safety skills are built.5 Teaching young people fundamental workplace safety and health knowledge and affording them opportunities to practice safety-related skills should be included in all efforts and activities aimed at “skilling up” the future workforce. Currently, effective workplace safety and health training is missing from many job skills training and career readiness programs, and most young people enter the labor force unprepared for the hazards they may encounter.5

PROMOTING WORK SAFETY AND HEALTH COMPETENCIES

School offers a common societal context in which youths can be reached with foundational workplace safety and health competencies. This instruction could be integrated into health education; career and technical education; science, technology, engineering, and math classes; and career readiness and exploration classes. Other countries provide a model for this integration. In Europe, governments and nongovernmental organizations promote mainstreaming occupational safety and health into schools to ensure that all students receive this instruction before they start work. Research from France suggests that occupational safety education provided to young people while in school may protect against future work-related injuries.6

Interviews conducted as part of formative research in 2015 (by R. J. G.) with 34 US school administrators indicate that their districts do not provide the majority of students any workplace safety instruction. A tool US secondary schools can use to provide students this preparation is Youth@Work—Talking Safety, a free foundational workplace safety and health curriculum from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and its partners, including the Labor Occupational Health Program (University of California, Berkeley), the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and the Education Development Center, Inc. (http://bit.ly/2nOoK3T).

The curriculum, customized for all states and several territories and available in Spanish, contains six 45-minute lessons and five supplemental lessons for further exploration. It is designed to teach essential, portable knowledge and skills that complement the safety training youths should receive at worksites and through career and technical education and apprenticeship programs. The competencies delivered through Talking Safety pertain to workplace hazard recognition and control, employer responsibilities and worker rights and roles, emergencies at work, and communication with others when feeling unsafe or threatened.5 Each edition of Talking Safety includes a pdf with detailed teaching plans and student handouts, a PowerPoint presentation, and a video. Lessons are built on interactive activities, such as games, role-playing, and case studies, that enable students to practice skills and explore common misconceptions and beliefs about workplace safety and health. Talking Safety presents valuable information for young people, their teachers, and parents. Safety professionals and public health practitioners also benefit by observing how the content is tailored and presented to youths.

To build an evidence base, Talking Safety was implemented and evaluated using a quasiexperimental design in one of the largest US school districts. In spring 2016, 42 teachers trained in Talking Safety delivered the curriculum to 1748 eighth graders (aged 12–13 years) in 131 classes in 33 middle schools.7 Questionnaires measured pretest to posttest changes in students’ occupational safety knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, self-efficacy, and behavioral intention to engage in workplace safety actions. After the intervention, students demonstrated statistically significant increases in mean scores across the student outcomes examined.7 Findings demonstrate the effectiveness of Talking Safety to prepare students with a foundation of workplace safety competencies and provide support for using this curriculum to prepare the future workforce for safe and healthy employment. The Talking Safety curriculum is currently being evaluated through a randomized trial in another large urban school district. Preliminary results are consistent with previous research findings.7 Future studies are needed to enumerate the factors that facilitate or hinder the integration of workplace safety and health content into school courses and programs and to monitor the long-term impact of these efforts to reduce young worker morbidity and mortality.

PREPARING THE FUTURE WORKFORCE

State and federal agencies that carry out critical enforcement activities of child labor and workplace health and safety laws can also play a role in promoting the inclusion of workplace safety and health competencies into job preparation initiatives. Moreover, agencies involved with workforce development, apprenticeship programs, and youth education can champion these efforts. For example, in 2017 the US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration integrated workplace safety and health competencies into their Generic Building Blocks Competency Model (http://bit.ly/2nOq5Yt). Competency models, recognized by the President’s Apprenticeship Expansion Task Force,1 are widely used by the workforce development sector to identify employers’ skills needs. The inclusion of the “health and safety” building block for all industries and models may ensure that foundational competencies for safe and healthy work become integral to job preparation programs for young and new workers. Finally, given the potential for substantial direct and indirect costs of workplace injuries and illnesses, preparation of the emerging workforce with foundational, workplace safety and health skills should be incorporated into an overall approach to prevent occupational injury and illness.

Despite progress, the persistent burden of young worker morbidity and mortality remains a critical public health challenge. A comprehensive strategy for protecting young workers requires structural and environmental change (to design and maintain safer worksites), legislation and enforcement, and education and training. The current, national focus on preparing young people with job skills to compete in the 21st-century economy1 offers a timely opportunity to make workplace safety and health central to these efforts. Equipping young people with competencies in workplace safety and health before they enter the formal labor force contributes to promoting the long-term health and well-being of current and future workers, our nation’s most vital asset.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their thorough and thoughtful reviews of the editorial, we thank Diane Bush, MPH, Labor Occupational Health Program, UC Berkeley; Letitia Davis, ScD, Occupational Health Surveillance Program, Massachusetts Department of Public Health; and Kimberly J. Rauscher, ScD, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health Sciences, West Virginia University.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Task Force on Apprenticeship Expansion. Final report to the president of the United States. Available at: https://www.dol.gov/apprenticeship/docs/task-force-apprenticeship-expansion-report.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 2.Zierold KM, Anderson HA. Severe injury and the need for improved safety training among working teens. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30(5):525–532. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauscher KJ, Runyan CW, Schulman MD, Bowling JM. US child labor violations in the retail and service industries: findings from a national survey of working adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1693–1699. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rauscher KJ, Myers DJ, Miller ME. Work‐related deaths among youth: understanding the contribution of US child labor violations. Am J Ind Med. 2016;59(11):959–968. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okun AH, Guerin RJ, Schulte PA. Foundational workplace safety and health competencies for the emerging workforce. J Safety Res. 2016;59:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boini S, Colin R, Grzebyk M. Effect of occupational safety and health education received during schooling on the incidence of workplace injuries in the first 2 years of occupational life: a prospective study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):e015100. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerin RJ, Okun AH, Barile JP, Emshoff JG, Ediger MD, Baker DS. Preparing teens to stay safe and healthy on the job: a multilevel evaluation of the Talking Safety curriculum for middle schools and high schools. Prev Sci. 2019;20(4):510–520. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]