Abstract

Background

Despite high two-dose measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine coverage, a large mumps outbreak occurred on the U.S. Territory of Guam during 2009–2010, primarily in school-aged children.

Methods

We implemented active surveillance in April 2010 during the outbreak peak and characterized the outbreak epidemiology. We administered third doses of MMR vaccine to eligible students aged 9–14 years in 7 schools with the highest attack rates (ARs) between 5/18/2010—5/21/2010. Baseline surveys, follow-up surveys, and case-reports were used to determine mumps ARs. Adverse events post-vaccination were monitored.

Results

Between 12/1/2009—12/31/2010, 505 mumps cases were reported. Self-reported Pohnpeians and Chuukese had the highest relative risks (54.7 and 19.7, respectively) and highest crowding indices (mean: 3.1 and 3.0 persons/bedroom, respectively). Among 287 (57%) school-aged case-patients, 270 (93%) had ≥2 MMR doses. A third MMR dose was administered to 1068 (33%) eligible students. Three-dose vaccinated students had an AR of 0.9/1000 compared to 2.4/1000 among two-dose vaccinated students >1 incubation period post-intervention, but the difference was not significant (p= 0.67). No serious adverse events were reported.

Conclusions

This mumps outbreak occurred in a highly vaccinated population. The highest ARs occurred in ethnic minority populations with the highest household crowding indices. After the third dose MMR intervention in highly affected schools, the AR in three-dose MMR recipients was 60% lower than two-dose vaccine recipients, but the difference was not statistically significant and the intervention occurred after the outbreak peaked. This outbreak may have persisted due to crowding at home and high student contact rates.

Keywords: mumps, outbreak control, third dose MMR intervention, vaccine preventable disease, immunization

INTRODUCTION

Mumps is an acute, viral illness that classically manifests with fever and parotitis; 25–40% of infections are asymptomatic. Severe complications include encephalitis[1], deafness[2, 3], and orchitis[4]. Mumps vaccine was licensed in the United States in 1967 and recommended for routine use in 1977. A second dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine was recommended for all school-aged children and select high risk groups in 1989 for measles prevention[5]. Due to high two-dose MMR vaccine coverage, rates of reported mumps in the U.S. declined by over 99% in 2005 compared with the immediate pre-vaccine era[6]. Annual mumps incidence in the U.S. was approximately 1 case per million population (0.9–1.2 per million/population) between 2000 and 2005[7]. A mumps elimination goal was set for 2010[8].

However, from 2006—2010, several large mumps outbreaks occurred in primarily two-dose vaccinated U.S. populations. In 2006, 6584 reported cases occurred, mainly affecting Midwestern college students. Standard control measures (e.g. isolation and vaccine catch-up campaigns) were implemented for outbreak control[6]. During 2009–2010, 3502 mumps cases were reported in a highly two-dose vaccinated population in an Orthodox Jewish community in the Northeast; this outbreak was the first to use a third dose MMR vaccine intervention for outbreak control[9].

On February 25, 2010, Guam Department of Public Health and Social Services (DPHSS) was informed of a mumps case in a two-dose vaccinated 15 year old male. More cases were subsequently reported, primarily among vaccinated school children aged 9–14 years. The last reported mumps outbreak on Guam occurred in 1958; in the past decade, Guam reported an average of four mumps cases annually. As part of the public health response to this outbreak, a third dose of MMR vaccine was administered. We evaluated the outbreak epidemiology and the safety and impact of a third dose MMR vaccine intervention in target populations for outbreak control.

METHODS

Setting

Guam is a U.S. territory with a 2010 population of ~180,692 persons[10]. The primary ethnicity on Guam is Chamorro, comprising 37% of the population[10]. Guam follows the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations for MMR vaccination: the first MMR dose is administered at ages 12–15 months and the second dose at 4–6 years[11].

Outbreak Epidemiology

Mumps cases were classified according to the 2008 Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists mumps case definition[12]. On Guam, health-care providers are mandated by law to report mumps cases to Guam DPHSS. DPHSS instituted active surveillance April 20, 2010 at the peak of the outbreak with schools, daycares, select provider clinics and laboratories reporting mumps cases daily; close contacts of reported cases were investigated. DPHSS collected information on demographics, laboratory results, symptom onset date, mumps-related complications, and vaccination history. Vaccination status of all case-patients was verified by health-care providers; administration dates were noted.

Laboratory criteria for mumps diagnosis included isolation of mumps virus from clinical specimens (i.e., either an oropharyngeal or buccal mucosa swab), detection of mumps nucleic acid, or detection of mumps IgM antibody measured by qualitative assays. All culture, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests[13], mumps virus sequencing, and genotype analysis[14, 15] were conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). IgM tests were conducted at CDC and state and commercial labs.

The outbreak period was defined as 12/1/2009—12/31/2010. We calculated mumps ARs for the population overall and by sex, age, and ethnicity. AR denominators were obtained from the projected 2010 Guam census data[10]. Because census age groupings did not correlate with the age group most affected by the outbreak, we created a 9–14 year age group category by adding one-fifth of the 5–9 year census age group to the 10–14 year census age group.

Third Dose MMR Vaccine Intervention

Public schools were eligible for the third dose intervention if they had >90% two-dose MMR vaccine coverage, ongoing mumps transmission (i.e., mumps cases in the preceding two weeks), and a mumps AR of >5/1000. Students in the intervention schools were eligible if they were in the age group with the highest AR (aged 9–14 years), had a history of two MMR vaccine doses, had not previously received a third MMR vaccine dose, and had no history of mumps. Students who were not up-to-date with the recommended two doses of MMR vaccine were offered appropriate vaccinations. School vaccination coverage was assessed by reviewing school vaccine records.

Vaccination status of students participating in the study was confirmed either through immunization card review by parents or immunization staff, or review of DPHSS and school vaccine registries. For students with unknown or incomplete vaccination status, verification was obtained from health-care providers.

This study was approved by the CDC and Guam Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Boards. Written informed parental consent and student assent were obtained.

Baseline and follow-up surveys captured demographic characteristics, vaccination history, mumps history, clinical features and complications of mumps, number of people in the household, and number of bedrooms in the house. Follow-up surveys also captured possible adverse events following immunization. Baseline surveys were distributed to all eligible students during the third dose MMR vaccine intervention from May 18–21, 2010. Follow-up surveys were distributed from October 4–15, 2010 to the original eligible cohort.

Mumps cases were identified by parental report on baseline and follow-up surveys. To ensure completeness in ascertaining cases, we supplemented our survey case count with confirmed cases reported to Guam DPHSS. If students were not reported as a case to DPHSS, did not report mumps in the baseline survey, and did not return a follow-up survey, they were categorized as non-cases in our analysis.

Using the exact date of the vaccination clinic at the case-students’ school, we compared mumps attack rates (ARs) following the intervention between eligible students aged 9–14 years who received the third MMR vaccine dose with non-recipients (i.e., students with documentation of 2 doses of MMR vaccine) from post-intervention day 22 through day 228 (i.e., December 31, 2010, the end of the study period). We excluded the 21 days (1 incubation period) following the intervention from the analysis (May 22– June 11, 2010) since persons infected prior or during the intervention may have been incubating mumps during this timeframe[16, 17].

All vaccine recipients were monitored 30 minutes post-intervention to evaluate immediate adverse events. The follow-up survey contained questions on adverse events that may have occurred up to two weeks post-intervention, including any serious adverse events resulting in permanent disability, hospitalization, life-threatening illnesses, or death[18].

All data were analyzed with SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). Denominators for school ARs were calculated using school enrollment data. We compared post-intervention mumps ARs between students who received the third dose of MMR vaccine with those who did not using a Fischer’s Exact test. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant. Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Crowding was assessed by dividing the number of household members by bedrooms in the house. Two-independent samples t-tests were used to compare differences between the means for household size and crowding between ethnic groups.

RESULTS

Outbreak Epidemiology

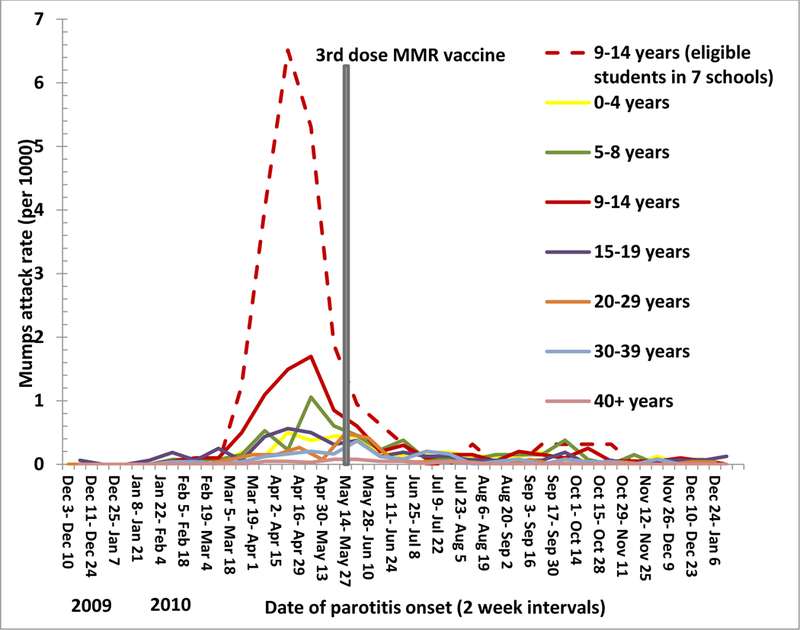

The first case of mumps was reported to DPHSS on February 25, 2010, but the index case-patient was retrospectively identified as having parotitis onset December 7, 2009. The index case-patient was a Guam resident who imported mumps from the island of Pohnpei where mumps was known to be circulating. Between 12/1/2009—12/31/2010, 505 cases of mumps were reported (Figure 1) with a median age of 12 years (range: 2 months to 79 years) [Table 1]; 50% were males. There were 5 (3.3%) reports of orchitis among post-pubertal males with three additional reports of orchitis among pre-pubertal males aged 3, 7, and 9 years. There were 2 hospitalizations for mumps-related illness; one was for supportive care of orchitis and the other was misdiagnosed as neck cellulitis but was later confirmed as mumps parotitis. No deaths were reported.

Figure 1:

Epidemiologic curve of reported mumps cases on Guam from December 1, 2009— December 31, 2010 1Source: Case Reports, Guam, through December 31, 2010 2 DPHSS, Department of Public Health and Social Services

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Mumps Case-patients (n=505) Compared with the Guam General Population (n=180,692), Guam, December 1, 2009— December 31, 2010

| Demographics | Cases (n=505) | Guam Census (n=180,692) |

Attack Rates (per 1000) |

Risk Ratio (Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 251 (50) | 91820 (51) | 2.7 | 0.96 (0.80–1.14) |

| Female | 254 (50) | 88872 (49) | 2.9 | Ref |

| Age Group (years) | ||||

| 0–4 | 60 (12) | 16035 (9) | 3.7 | 7.3 (4.7–11.1) |

| 5–8 | 70 (14) | 13260 (7) | 5.3 | 10.2 (6.8–15.5) |

| 9–14 | 169 (34) | 20134 (11) | 8.4 | 16.2 (11.2–23.5) |

| 15–19 | 68 (13) | 16066 (9) | 3.9 | 8.2 (5.4–12.4) |

| 20–29 | 54 (11) | 26560 (15) | 2.0 | 3.9 (2.6–6.1) |

| 30–39 | 51 (10) | 24455 (14) | 2.1 | 4.0 (2.6–6.3) |

| 40+ | 33 (7) | 64182 (36) | 0.5 | Ref |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Chamorro | 170 (34) | 66879 (37) | 2.5 | 2.6 (2.0–3.6) |

| Chuukese | 140 (28) | 7271 (4) | 19.3 | 19.7 (14.5–26.9) |

| Filipino | 52 (10) | 47540 (26) | 1.1 | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) |

| Pohnpeian | 88 (17) | 1594 (1) | 55.2 | 54.7 (39.2–76.3) |

| Other | 55 (11) | 57408 (32) | 1.0 | Ref |

Children aged 9–14 years had the highest overall AR (8.4/1000), followed by those aged 5–8 years (5.3/1000), 15–19 years (3.9/1000), and 0–4 years (3.7/1000). Adults 40 years and older had the lowest AR (0.5/1000). Correspondingly, all age groups less than 40 years were statistically more likely to have reported mumps case-patients than adults 40 years or older, and children aged 9–14 years had a 16 times higher risk (RR=16.3, CI: 11.2–23.5). Compared to persons self-reporting “other” ethnicity, which comprised 32% of the Guam population, persons who reported their ethnicity as Pohnpeian or Chuukese had a markedly elevated risk of mumps [Pohnpeian (RR=54.7, CI: 39.2–76.3) or Chuukese (RR=19.7, CI: 14.5–26.9)]. In contrast, persons reporting Filipino ethnicity did not have an elevated risk and those reporting Chamorro ethnicity had a mildly elevated risk (Table 1). Ninety-six percent of mumps case-patients aged 9–14 years were vaccinated with two doses of MMR vaccine, followed by 90% of case-patients aged 5–8 years, and 88% of case-patients aged 15–19 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaccination Status by Age Group of Mumps Case-patients, Guam, December 1, 2009— December 31, 2010

| Age group | Vaccinated with 1 MMR dose (percent) |

Vaccinated with 2 MMR doses (percent) |

Unvaccinated (percent) |

Total case-patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 5 |

| 1–4 years | 33 (60.0) | 4 (7.3) | 18 (32.7) | 55 |

| 5–8 years | 2 (2.9) | 63 (90.0) | 5 (7.1) | 70 |

| 9–14 years | 5 (3.0) | 162 (95.8) | 2 (1.2) | 169 |

| 15–19 years | 1 (1.5) | 60 (88.2) | 7 (10.3) | 68 |

| 20–29 years | 3 (5.6) | 10 (18.5) | 41 (75.9) | 54 |

| 30–39 years | 8 (15.7) | 4 (7.8) | 39 (76.5) | 51 |

| ≥40 years | 1 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | 30 (90.9) | 33 |

Laboratory

Of 505 case-patients, 309 (61%) had sera tested for mumps IgM; 60 (19%) tested IgM positive. Twenty-eight (82%) of 34 viral specimens tested positive by RT-PCR, of which 14 (41%) also tested positive by culture1. Sequence analysis of mumps viruses identified mumps genotype G as the outbreak strain.

Intervention Schools

There are 64 public and private schools on Guam (preschool through high school). Seven (11%) schools (four elementary and three middle schools) met the inclusion criteria with ARs ranging from 8.4–31.5/1000 among children aged 9–14 years (i.e., grades 4–8). These seven schools were in the north and central regions of Guam, the most densely populated part of the island. The high mumps ARs of these seven schools reflected the distribution of cases on Guam, as a majority of the island’s case-patients occurred in this age group and resided in the north and central regions. All seven schools had two-dose MMR vaccine coverage between 99%–100%.

MMR Vaccine Third Dose Intervention

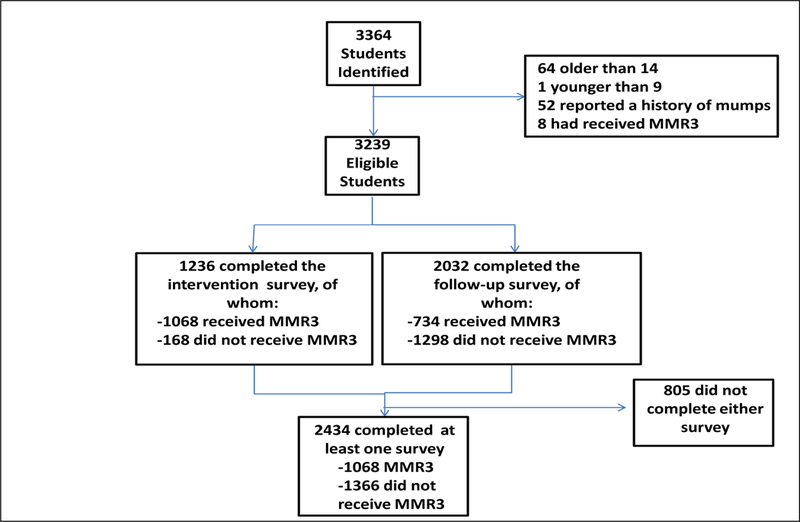

The third dose intervention was implemented in the highest AR schools in the most affected age group (students aged 9–14 years), but occurred after the outbreak peaked (Figure 3a); 186 (37%) of the 505 outbreak cases occurred after the intervention. There were 3364 students in grades 4–8 in the seven selected schools, of whom 3239 were eligible for the third dose intervention. Of those eligible, 1068 (33%) received a third dose of MMR vaccine. At least one survey was returned by 2434 (75%) eligible students, with 1236 (38%) returning a baseline and 2032 (63%) returning a follow-up survey. All 1068 vaccinees returned a baseline survey and 734 (69%) returned a follow-up survey (Figure 2). Non-respondents were statistically more likely to be male (p=0.0024) and in grades 7–8 (p<0.0001) compared to survey respondents. Despite differences between survey respondents and non-respondents, respondents reported similar demographic characteristics proportionally compared to the Guam general population with 1220 (50%) males, 1006 (41%) self-reporting Chamorro ethnicity, and 1761 (77%) responding they had insurance. Students who received the third dose were statistically more likely to be without health insurance (p=0.008), female, (p<0.0001), and in grades 4–6 (p=0.0002), compared with non-vaccine recipients.

Figure 3a:

Mumps attack rates (cases/1000) by age group by two-week period, Guam, December 1, 2009— December 31, 2010

Figure 2:

Flow sheet of students eligible for participation in the third dose MMR vaccine intervention and surveys, Guam 2010

The mean household size among respondents was 6.2 members (range: 2–26). Chuukese respondents had the largest household size with a mean of 7.3 members (range: 2–26), followed by Pohnpeian respondents with a mean of 7.0 members (range: 2–17), Chamorro respondents with a mean of 6.2 members (range: 2–18), and Filipino respondents with mean of 5.7 members (ranges: 2–16). The mean number of household members among Chuukese and Pohnpeian respondents was significantly higher than among Chamorro and Filipino respondents (p<0.05).

The average crowding index among respondents was 2.3 persons per bedroom. Pohnpeian and Chuukese households had the highest crowding indices with a mean of 3.1 and 3.0 persons per bedroom (ranges: 1–10 and 1–13, respectively), compared with Chamorro and Filipino households which had crowding indices of 2.2 and 2.1 persons per bedroom (ranges: 0.3–14 and 0.7–14, respectively). The mean crowding index in Pohnpeian and Chuukese households was significantly higher than in Chamorro and Filipino households (p<0.0001).

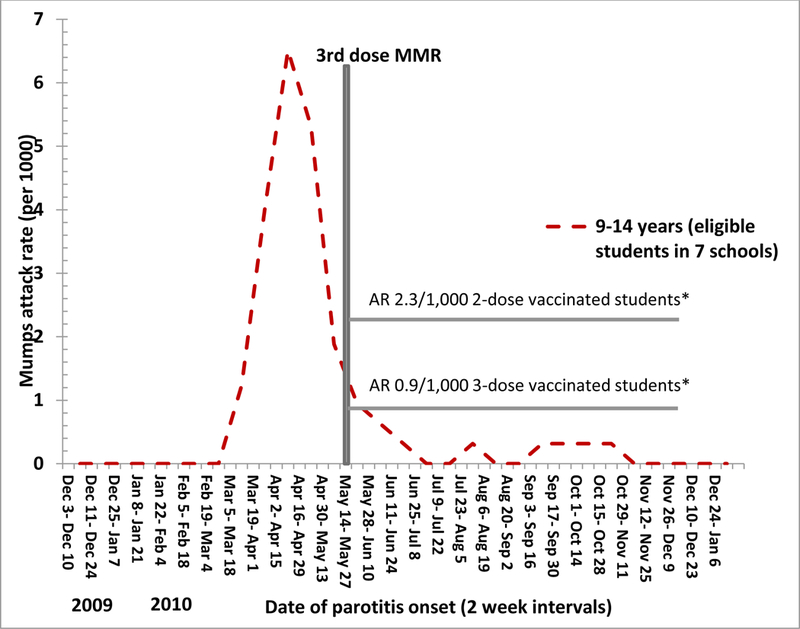

Six students eligible for the third MMR dose from 4 different intervention schools were diagnosed with mumps in the post-intervention period; 5 (83%) did not receive the third MMR dose and 1 (17%) received the third MMR dose (Table 3). The mumps AR was 2.6-fold lower in those who received the third MMR dose compared with two-dose recipients (0.9/1000 versus 2.3/1000, RR= 0.4; CI: 0.05–3.5, p=0.67); this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 3b).

Table 3.

Mumps Attack Rates among Students Aged 9–14 Years in Seven Schools More Than One Incubation Period following the Third Dose MMR Vaccine Intervention, Guam 2010

| >1 incubation period post- vaccination |

Comparison of attack rates between students with 3 versus 2 MMR doses >1 incubation period post-vaccination¶ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Cases |

N | Attack Rates (per 1000) |

Relative Risk (95% Confidence Intervals) |

P-value | |

| Students who had 2 doses of MMR vaccine | 5 | 2171 | 2.3 | Reference | |

| Students who had 3 doses of MMR vaccine | 1 | 1068 | 0.9 | 0.4 (0.05,3.5) | 0.67 |

value calculated using Fischer’s exact test

Figure 3b:

Comparison of mumps attack rates (cases/1000) post-intervention among eligible students who received the third MMR vaccine dose compared with those who did not receive the third dose, Guam, December 1, 2009— December 31, 2010 * >1 incubation period post-intervention

Adverse Events

No immediate adverse events were reported. During the two weeks post-vaccination, 32 (6.0%) students reported an adverse event; the most frequent self-reported events were: joint aches (2.6%), pain, redness and swelling at the injection site (2.4%), and dizziness (2.4%) [Table 4]. No serious adverse events were reported, and no medical attention was sought related to these events.

Table 4.

Self-reported Adverse Events Reported during the Two Weeks following the Third Dose MMR Vaccine Intervention (N=533)*, Guam, 2010

| Adverse Event | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Joint ache (n=506) | 13 (2.6) |

| Pain/redness (n=509) | 12 (2.4) |

| Dizzy (n=509) | 12 (2.4) |

| Fever (n=512) | 5 (1.0) |

| Syncope (n=508) | 0 (0) |

| Difficulty breathing (n=509) | 0 (0) |

| Hives/rash on the body (n=508) | 0 (0) |

| Sought medical care following third dose of MMR vaccine (n=487) | 0 (0) |

| Any adverse event (n=533)** | 32 (6.0) |

Not all vaccinees completed this section of the survey.

8 respondents reported 2 adverse events, and 1 respondent reported 3 adverse events

DISCUSSION

The Guam mumps outbreak was the third largest in the U.S. and its territories since 2005, and the second outbreak where a third dose of MMR vaccine was administered, thus providing an opportunity to evaluate the impact and safety of a third dose MMR vaccine intervention in mumps outbreak control. Although the intervention occurred after the outbreak peaked, the AR in students who received the third dose of MMR vaccine was 60% lower than two-dose vaccine recipients during the post-intervention period. Perhaps due to the smaller number of mumps cases that occurred at this stage of the outbreak, the difference in ARs was not statistically significant. Nonetheless, the effect of a third dose in boosting immunity and increasing vaccine effectiveness is biologically plausible; rapid anamnestic antibody responses following third MMR vaccine doses have been reported[19].

Mumps outbreaks have occurred in other populations with high two-dose vaccination coverage, including tradition-observant Orthodox Jewish adolescent school students[9], Midwestern college-age students[6], and international settings[20–22]. Some of the potential contributors in those outbreaks, including high population density and high contact rates, may also have contributed to the outbreak in Guam[6]. Guam families typically live in crowded environments with large extended families (i.e., Guam has a crowding index of 3.9 persons/household compared with 2.6 persons/household on the U.S. mainland; survey respondents had an average of 6.2 family members[10]). Due to high contact rates among students, the importance of schools as high-risk transmission settings for mumps and other outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases has been well-documented[6, 23].

Compared with other two-dose mumps outbreaks, some epidemiological features of this outbreak were unusual. Children aged 9–14 years were disproportionately affected; this was a younger age group than described in similar outbreaks[6, 9]. Cases occurred in all ethnic groups, but the highest ARs occurred in the ethnic minority populations with the most household members and highest household crowding indices. We are unable to explain this epidemiological finding but postulate that contributing factors may include higher household density and/or genetic effects.

Though this outbreak occurred in a highly-vaccinated population, there were lower transmission rates and fewer mumps-related complications than would be expected in the absence of appropriate vaccination. Orchitis was reported among 3.3% of post-pubertal males. This is consistent with lower rates of complications in fully vaccinated persons and with findings from the Northeast outbreak[9], but much less than pre-vaccine rates of 30% (range 19–44%) though the younger median age of post-pubertal cases in this outbreak should be considered when interpreting this comparison[24–28]. The occurrence of 3 reports of orchitis in pre-pubertal males was unusual since there have only been 12 previously documented reports of pre-pubertal mumps orchitis[29, 30]. However, 2 of the 3 cases were reported by parents, and the third patient was hospitalized for orchitis with no documented parotitis or laboratory confirmation. Previous studies have documented that mumps can present as orchitis in the absence of parotitis[24, 31].

Genotype G, the outbreak strain, was identified in the 2006 and 2009–2010 outbreaks in the U.S., the outbreak in Canada in 2005–2006, the United Kingdom in 2004–2005, and is seen globally, though this lineage was different from the Northeast outbreak. Mumps is endemic throughout the world; only 61% of countries vaccinate against mumps[32]. It is possible that since the last reported mumps outbreak on Guam in 1958 and prior to this outbreak, mumps cases were imported on the island from international visitors but went undetected. Nonetheless, although over one million international passengers visit Guam annually[33], the index case-patient was a Guam resident who traveled to another Pacific island where mumps was known to be circulating.

MMR vaccine in the U.S. contains the Jeryl-Lynn mumps strain[5, 11]. In post-licensure studies, vaccine effectiveness against clinical mumps has a median effectiveness of 78% (range: 49%–92%) for one dose of mumps vaccine and 88% (range: 66%–95%) for two doses of mumps vaccine[6, 34, 35]. Thus, although reported mumps cases in the U.S. were 99% lower in 2010 compared with the pre-vaccine era, sustained transmission of mumps in highly vaccinated two dose populations occurs in rare circumstances[6, 9]. We were unable to evaluate two-dose vaccine effectiveness during the outbreak in Guam due to the extremely high two dose coverage. Effectiveness of three doses of mumps vaccine has not been evaluated.

Our findings are subject to limitations. Many families did not visit a health-care provider for subsequent ill family members, likely leading to underreporting. There were anecdotal reports from community leaders that there were large numbers of unreported cases despite active surveillance. Although transmission was still occurring, the intervention occurred after the outbreak peaked. The small numbers of mumps cases in the targeted population post-intervention limited our ability to draw firm conclusions about the impact of the third dose intervention. There were statistically significant differences between survey respondents and non-respondents, as well as among survey participants who received the third dose of MMR vaccine and those who did not. However, these differences are unlikely to bias the effect of a third dose of MMR vaccine. Census data were not available to explore crowding indices by ethnicity among the Guam general population.

Implementing the third dose intervention in the school setting allowed us to verify vaccination records while targeting specific age groups in the most highly affected regions. However, the third dose was only administered to 5.3% of all students aged 9–14 years making it difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of the intervention at the population-level.

Mumps outbreaks can cause a substantial economic and resource burden on affected families and the public health sector[36], and targeted interventions may be a useful public health approach in select high-risk transmission settings. The results of our study suggest that the administration of a third dose of MMR vaccine may be an effective method of controlling mumps outbreaks in two-dose vaccinated populations in specific settings. For future mumps outbreaks in primarily two-dose vaccinated populations, the focus should be on ensuring that everyone is up-to-date with the recommended two-dose vaccination schedule, as well as enforcing isolation measures and encouraging appropriate hygiene practices. Our findings support the need for additional evaluations that use third doses of MMR vaccine for mumps outbreak control in highly two-dose vaccinated populations and underscore the importance of initiating the intervention early in the outbreak.

Key points:

In Guam, a mumps outbreak occurred in highly vaccinated children aged 9–14 years. Following a third dose measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine intervention, the attack rate in three-dose recipients was 60% lower than two-dose recipients and no serious adverse events were reported.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our thanks to Albert Barskey, Stephanie Bialek, Scott Grytdal, Mike Hudges, John McKenna, Carolyn Parry, Rose Vibar, Gissela Villarruel, Jennifer Yara, and the students (Tina Cruz, Kristan Leon Guerrero, Noemi Ramirez, and P.J. Siquig) for their assistance during the field investigation. We would like to thank all the outreach coordinators of the Department of Education on Guam, Student Support Services Division, especially Doris Bukikosa, for their tireless efforts in helping us reach students during the follow-up survey. We also extend our thanks to Robert Haddock for his historical knowledge of mumps outbreaks on Guam. Finally, we would like to thank the public health nursing staff, especially Margarita Gay, for helping us with the school vaccination clinics.

Footnotes

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest: All authors: no conflicts.

The difference in positive results between RT-PCR and culture is likely because two of the three shipments of specimens were not frozen on arrival compromising specimen quality. In the only shipment that arrived frozen, 11 of 14 specimens were positive by culture.

References

- 1.Koskiniemi M, Donner M, Pettay O. Clinical appearance and outcome in mumps encephalitis in children. Acta Paediatr Scand 1983. July;72(4):603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everberg G Deafness following mumps. Acta Otolaryngol 1957. Nov-Dec;48(5–6):397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarkkanen J, Aho J. Unilateral deafness in children. Acta Otolaryngol 1966. March;61(3):270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falk WA, Buchan K, Dow M, et al. The epidemiology of mumps in southern Alberta 1980–1982. Am J Epidemiol 1989. October;130(4):736–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Notice to Readers: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for the Control and Elimination of Mumps. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55(22):629–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dayan GH, Quinlisk MP, Parker AA, et al. Recent resurgence of mumps in the United States. N Engl J Med 2008. April 10;358(15):1580–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaiken BP, Williams NM, Preblud SR, Parkin W, Altman R. The effect of a school entry law on mumps activity in a school district. JAMA 1987. May 8;257(18):2455–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Healthy people 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office (GPO), 2000. November 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Update: Mumps Outbreak --- New York and New Jersey, June 2009--January 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010;59(05):125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bureau of Statistics and Plans Office of Govenor. 2008 Guam Statistical Yearbook. Hagatna, Guam, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC. Measles, Mumps, and Rubella -- Vaccine Use and Strategies for Elimination of Measles, Rubella, and Congenital Rubella Syndrome and Control of Mumps: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1998;47((RR-8)):1–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Position statement 09-ID-50, Revision of the Surveillance Case Definition for Mumps. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Real-time (TaqMan®) RT-PCR Assay for the Detection of Mumps Virus RNA in Clinical Samples. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mumps/downloads/lab-rt-pcr-assay-detect.doc Accessed July 24.

- 14.Rota JS, Turner JC, Yost-Daljev MK, et al. Investigation of a mumps outbreak among university students with two measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccinations, Virginia, September-December 2006. Journal of medical virology 2009. October;81(10):1819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin L, Rima B, Brown D, et al. Proposal for genetic characterisation of wild-type mumps strains: preliminary standardisation of the nomenclature. Arch Virol 2005. September;150(9):1903–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plotkin S. Vaccines. 5th ed Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CDC. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Activities/vaers.html Accessed June 5, 2012.

- 19.Date AA, Kyaw MH, Rue AM, et al. Long-term persistence of mumps antibody after receipt of 2 measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccinations and antibody response after a third MMR vaccination among a university population. J Infect Dis 2008. June 15;197(12):1662–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anis E, Grotto I, Moerman L, Warshavsky B, Slater PE, Lev B. Mumps outbreak in Israel’s highly vaccinated society: are two doses enough? Epidemiol Infect 2012. March;140(3):439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan KE, Anderson M, Krajden M, Petric M, Mak A, Naus M. Mumps virus detection during an outbreak in a highly unvaccinated population in British Columbia. Canadian journal of public health Revue canadienne de sante publique 2011. Jan-Feb;102(1):47–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whelan J, van Binnendijk R, Greenland K, et al. Ongoing mumps outbreak in a student population with high vaccination coverage, Netherlands, 2010. Euro Surveill 2010;15(17). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeung LF, Lurie P, Dayan G, et al. A limited measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated US boarding school. Pediatrics 2005. December;116(6):1287–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philip RN, Reinhard KR, Lackman DB. Observations on a mumps epidemic in a virgin population. Am J Hyg 1959. March;69(2):91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laurence D, McGavin D. The complications of mumps. British medical journal 1948. January 17;1(4541):94–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Association for the Study of Infectious Disease. A retrospective survey of the complications of mumps. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 1974. August;24(145):552–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beard CM, Benson RC Jr., Kelalis PP, Elveback LR, Kurland LT. The incidence and outcome of mumps orchitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935 to 1974. Mayo Clinic proceedings 1977. January;52(1):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arday DR, Kanjarpane DD, Kelley PW. Mumps in the US Army 1980–86: should recruits be immunized? Am J Public Health 1989. April;79(4):471–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Connolly N Mumps Orchitis without Parotitis in Infancts. Lancet 1953;261(6750):69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkinson JE, Bass HN. Mumps orchitis in a 3-year-old child. JAMA 1968. March 4;203(10):892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner CA. Mumps orchitis and testicular atrophy; occurrence. Ann Intern Med 1950. June;32(6):1066–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO. WHO/IVB database. Available at: http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/diseases/Mumps_map_schedule.jpg Accessed Mar 26, 2012.

- 33.U.S. Department of Transportation. Research and Innovative Technology Administration Bureau of Transporation Statistics. T-100 International Segment (All carriers). Available at: http://transtats.bts.gov/DL_SelectFields.asp?Table_ID=261 Accessed Mar 21, 2012.

- 34.Cohen C, White JM, Savage EJ, et al. Vaccine effectiveness estimates, 2004–2005 mumps outbreak, England. Emerg Infect Dis 2007. January;13(1):12–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deeks SL, Lim GH, Simpson MA, et al. An assessment of mumps vaccine effectiveness by dose during an outbreak in Canada. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne 2011. June 14;183(9):1014–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahamud A, Parker Fiebelkorn A, Nelson G, et al. Economic impact of the 2009–2010 Guam mumps outbreak on the public health sector and affected families. Vaccine In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]