Abstract

Neuroblastoma, a malignancy of the developing peripheral nervous system that affects infants and young children, is a complex genetic disease. Over the past two decades, significant progress has been made toward understanding the genetic determinants that predispose to this often lethal childhood cancer. Approximately 1-2% of neuroblastomas are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, and a combination of co-morbidity and linkage studies has led to the identification of germline mutations in PHOX2B and ALK as the major genetic contributors to this familial neuroblastoma subset. The genetic basis of “sporadic” neuroblastoma is being studied through a large genome-wide association study (GWAS). These efforts have led to the discovery of many common susceptibility alleles, each with modest effect size, associated with the development and progression of sporadic neuroblastoma. More recently, next-generation sequencing efforts have expanded the list of potential neuroblastoma-predisposing mutations to include rare germline variants with a predicted larger effect size. The evolving characterization of neuroblastoma’s genetic basis has led to a deeper understanding of the molecular events driving tumorigenesis, more precise risk stratification and prognostics, and novel therapeutic strategies. This review details the contemporary understanding of neuroblastoma’s genetic predisposition, including recent advances, and discusses ongoing efforts to address gaps in our knowledge regarding this malignancy’s complex genetic underpinnings.

Keywords: neuroblastoma susceptibility, germline, familial neuroblastoma, genome-wide association studies, pediatric cancer

Introduction

Neuroblastoma arises from aberrant neural crest development and is the most common malignancy diagnosed during the first year of life (Maris et al. 2007). This childhood cancer typically presents as abdominal, thoracic, or neck masses originating in the adrenal medulla or paraspinal sympathetic ganglia and is frequently metastatic at the time of diagnosis (Maris 2010). Neuroblastoma’s phenotypic heterogeneity, thought to reflect underlying genetic heterogeneity, distinguishes it among both childhood and adult malignancies, with a spectrum of outcomes that range from spontaneous regression to aggressive metastatic disease requiring an intensive multimodal treatment regimen (Cole and Everson 1956; Evans et al. 1996; Smith et al. 2010). Based on several well validated clinical, histologic, and genomic characteristics, neuroblastoma tumors are stratified into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups, which dictate prognosis and treatment stratification (Cohn et al. 2009). Neuroblastoma affects approximately 8 per 1,000,000 children, with approximately 600-700 cases diagnosed annually in the United States (NCI SEER Database). Despite representing just 5% of overall pediatric cancer diagnoses, neuroblastoma causes up to 12% of childhood cancer mortality; overall survival across all risk groups is approximately 80% but falls below 50% for children with high-risk disease (NCI SEER Database). Ethnic differences in neuroblastoma outcome have been demonstrated: although neuroblastoma is more prevalent in European American children, African American children tend to present with high-risk disease and have worse overall survival (Henderson et al. 2011). Frequently, high-risk neuroblastoma remains stubbornly intractable despite maximal intensification of chemoradiotherapeutic therapies. Advances such as the anti-GD2 antibody dinutuximab, while encouraging, have only had a modest impact on neuroblastoma outcomes (Yu et al. 2010; McGinty and Kolesar 2017). Moreover, children who are cured from their disease frequently suffer late treatment related side-effects, including growth delay, renal dysfunction, hypothyroidism, sensorineural hearing loss, cognitive impairment, and secondary neoplasms such as acute myeloid leukemia (Laverdiere et al. 2009; Perwein et al. 2011).

The first significant insight into the genomic lesions driving the development of neuroblastoma was the mid-1980’s observation that amplification of the MYCN oncogene in tumors is associated with clinically aggressive disease and poor prognosis (Schwab et al. 1983; Brodeur et al. 1984; Seeger et al. 1985). Subsequent research demonstrated that MYCN overexpression alone in neuroectodermal cells is sufficient to cause neuroblastoma in a dose-dependent manner (Weiss et al. 1997). While MYCN amplification status remains one of the most critical factors in neuroblastoma risk stratification, the list of recurrent somatic genomic alterations identified in neuroblastoma tumors has since grown to include several copy number changes, including deletions of the chromosome 1p and 11q arms and gain of chromosome 17q (Caron et al. 1993; Bown et al. 2001; Attiyeh, London, Mossé, et al. 2005). Furthermore, an overall segmental chromosome aberration pattern in tumors has been associated with inferior neuroblastoma outcome (Janoueix-Lerosey et al. 2009).

Like other embryonal malignancies, neuroblastoma is thought to be primarily a genetic disease. The genetic basis of neuroblastoma predisposition can be divided into two distinct domains, familial and sporadic, each yielding insights into pathogenesis. Approximately 1-2% of cases are inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and are considered familial, while the vast majority of neuroblastomas appear to arise sporadically. Linkage studies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have shed light on the genetic underpinnings of both familial and sporadic neuroblastoma, respectively. Indeed, neuroblastoma has been the exemplar for the genomic characterization of cancer predisposition; the identification of ALK mutations via linkage studies, for example, resulted in a clinical trial only a few years after the initial discovery (Mosse et al. 2008; Mosse et al. 2013). Moreover, efforts in neuroblastoma demonstrate the power of the GWAS approach: not only can GWAS identify loci associated with the development of cancer, but the genes at those loci are often important contributors to ongoing oncogenesis in established tumors. In addition, next-generation sequencing (NGS) efforts are also now yielding novel and potentially clinically actionable insights into neuroblastoma predisposition. However, while considerable progress has been made toward understanding the genetic events that predispose to neuroblastoma, our understanding of the genetic landscape of this malignancy remains incomplete. This review details what is known regarding the predisposition to neuroblastoma, as well as gaps in our knowledge of this complex genetic disease.

Familial Neuroblastoma

While the overwhelming majority of neuroblastomas arise sporadically, about 1-2% of neuroblastoma cases are inherited within families. These cases sometimes co-occur with other disorders of neural crest derived tissues, such as congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) and Hirschsprung disease (Stovroff, Dykes, and Teague 1995). The existence of familial neuroblastoma was first recognized in the late 1960s and early 1970s with the publication of several case reports detailing neuroblastomas across multiple generations following an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (Chatten and Voorhess 1967; Wong, Hanenson, and Lampkin 1971; Hardy and Nesbit 1972). As in classic cancer predisposition syndromes, familial neuroblastomas generally present at younger ages and often with multiple primary tumor sites (Kushner, Gilbert, and Helson 1986; Brodeur G 2000; Bourdeaut et al. 2012). The disease-causing mutations implicated in familial neuroblastoma are variably penetrant, suggesting that epistatic interactions govern individual phenotypes (McConville et al. 2006; Devoto et al. 2011).

PHOX2B

A small proportion of familial neuroblastoma cases arise in children with neurocognitive delays, neurocristopathies such as Hirschprung disease and CCHS, and dysmorphic features (Michna et al. 1988; Stovroff, Dykes, and Teague 1995). These cases of neuroblastoma comorbid with other neural crest-implicated diseases facilitated the discovery of the first neuroblastoma predisposition gene, the paired-like homeobox 2B gene (PHOX2B) (Mosse et al. 2004; Trochet et al. 2004). Located on chromosome 4p12, PHOX2B codes for a “master regulator” transcription factor required for neural crest differentiation into noradrenergic neurons (Pattyn et al. 1999). In 2003, frameshift mutations in PHOX2B were identified in patients with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (Amiel et al. 2003). This discovery prompted the hypothesis that PHOX2B mutations may also have a role in neuroblastoma predisposition. This hypothesis was soon validated when germline mutations in PHOX2B were discovered in neuroblastoma families; mutations in the PHOX2B gene have since been found to account for approximately 10% of heritable disease (Mosse et al. 2004; Trochet et al. 2004) (Table 1). PHOX2B-driven disease displays a robust genotype-phenotype association: while 45% of individuals with non-polyalanine repeat mutations (primarily missense mutations) develop neural crest tumors, only 1-2% of those with PHOX2B polyalanine expansions will develop neuroblastoma (Berry-Kravis et al. 2006; Heide et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Germline mutations in familial neuroblastoma predisposition genes. ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; PHOX2B, paired-like homeobox 2B; HPCAL1, Hippocalcin-like protein 1.

| Gene | Mutation | Clinical Characteristics | Functional Consequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHOX2B | R100L | Found in families with Hirschsprung disease and neuroblastic tumors | Missense mutation in DNA binding domain Not dominant negative |

(Trochet et al. 2004) (Bourdeaut et al. 2005) (Pei et al. 2013) |

| R141G | Neuroblastoma patient inherited from mother, who was not affected | Missense mutation in homeodomain | (Trochet et al. 2004) | |

| G197D | Present in a family with multiple individuals with NB but no evidence of autonomic dysfunction or neurocristopathy | (McConville et al. 2006) | ||

| 676delG | Found in families with Hirschsprung disease and neuroblastoma | Overexpression causes decrease in terminal differentiation markers in sympathetic ganglion cells Dominant negative Unable to bind HPCAL1 |

(Mosse et al. 2004) (Pei et al. 2013) (Wang et al. 2014) |

|

| Polyalanine Repeat Mutations | Associated with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome (CCHS) | Genotype 20/33 identified in a neuroblastoma/CCHS/Hirschsprung disease patient | (Armstrong et al. 2015) | |

| ALK | R1060H | Unlikely to be clinically significant Believed to be a silent/passenger mutation | Not predicted to be damaging by algorithms Between kinase and transmembrane domains |

(Bresler et al. 2014) |

| G1128A | P-loop of kinase domain Transforms NIH-3T3 cells |

(Mosse et al. 2008) | ||

| T1151M T1151R | T1151R found in patient with multifocal tumors | Promotes modest constitutive ALK activation Does not transform NIH-3T3 cells β3 Strand of kinase domain |

(Bourdeaut et al. 2012) (Bresler et al. 2014) |

|

| I1183T | Unlikely to be clinically significant Believed to be a silent/passenger mutation |

N-lobe of kinase domain | (Bresler et al. 2014) | |

| R1192P | Found in patient with multifocal tumors | β4 Strand of kinase domain Increases kcat of non-phosphorylated ALK tyrosine kinase domain by 15x Transforms NIH-3T3 cells |

(Mosse et al. 2008) (Bourdeaut et al. 2012) (Bresler et al. 2014) |

|

| L1204F | Unlikely to be clinically significant Believed to be a silent/passenger mutation |

C-lobe of kinase domain | (Bresler et al. 2014) | |

| R1231Q | Unlikely to be clinically significant Believed to be a silent/passenger mutation |

Not predicted to be damaging by algorithms αE helix of kinase domain |

(Bresler et al. 2014) | |

| I1250T | Unlikely to be clinically significant Believed to be a silent/passenger mutation |

“Kinase dead” mutation that results in reduced activity via protein instability/misfolding Phe core domain |

(Schonherr, Ruuth, Eriksson, et al. 2011) (Bresler et al. 2014) |

|

| R1275Q | Crizotinib-sensitive Found in patient with multifocal tumors | R1275 residue accounts for ~45% of overall neuroblastoma ALK mutations (sporadic and germline) Activation loop of kinase domain |

(Mosse et al. 2008) (Bresler et al. 2011) (Bourdeaut et al. 2012) |

In the years since PHOX2B was first identified as a familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene, its role in neuroblastoma tumorigenesis has more broadly come into focus. PHOX2B mutants have also been reported in up to 2% of sporadic neuroblastomas; however, the disease-contributing role of many of the identified PHOX2B somatic variants remains undefined (Van Limpt et al. 2004; Serra et al. 2008). Functional studies have shown that neuroblastoma-associated germline PHOX2B mutations exert a dominant negative block in terminal neural crest differentiation, thereby facilitating malignant transformation (Raabe et al. 2008; Nagashimada et al. 2012; Pei et al. 2013). In addition, recent mapping of the neuroblastoma super-enhancer landscape demonstrated that a subset of neuroblastoma cells with adrenergic properties express PHOX2B, and that PHOX2B knockdown impairs these cells’ growth(Boeva et al. 2017; van Groningen et al. 2017). In clinical practice, PHOX2B positivity via immunohistochemistry can help distinguish neuroblastomas from other small round blue cell tumors, and PHOX2B mRNA expression offers a promising biomarker for the detection of minimal residual disease (Hung et al. 2017; Greze, Brugnon, et al. 2017; Greze, Kanold, et al. 2017). However, given recent insights into the heterogeneity of cell types and differentiation states present within a given tumor, the absence of PHOX2B expression may not definitively exclude the presence of neuroblastoma.

ALK

In 2008, a large genetic linkage study incorporating 6000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across twenty families with neuroblastoma identified a linkage signal at chromosome 2p23-24. While MYCN resides within this locus, no mutations were found upon MYCN resequencing; rather, the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene was identified as the predominant driver of familial neuroblastoma (Mosse et al. 2008) (Table 1). It is estimated that gain-of-function mutations in ALK account for 75% of familial neuroblastoma. Parallel to the study that implicated ALK in hereditary neuroblastoma, multiple groups reported recurrent ALK point mutations and high-level DNA copy number amplification in sporadically arising neuroblastoma tumors (Janoueix-Lerosey et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2008; George et al. 2008). A subsequent comprehensive study of 1,596 sporadic neuroblastoma primary tumors determined that ALK is somatically mutated in 8% of cases, either by point mutation or copy number alteration (Bresler et al. 2014). This study validated ALK as the most frequently somatically mutated gene in sporadic neuroblastomas, in addition to its role as the primary familial neuroblastoma predisposition gene (Pugh et al. 2013; Bresler et al. 2014).

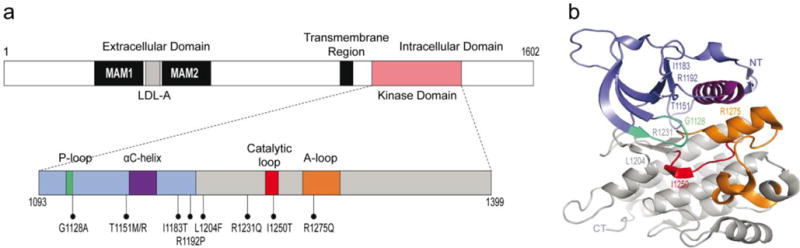

ALK is a receptor tyrosine kinase implicated in several malignancies, including anaplastic large cell lymphoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma, in which the associated genetic lesions are ALK fusions resulting from translocation events (Morris et al. 1994). By contrast, in neuroblastoma, recurrent point mutations result in constitutive phosphorylation and activation of the ALK receptor, thereby leading to aberrant downstream signaling (Mosse 2016) (Figure 1). Signaling downstream of ALK involves pro-proliferative pathways including RAS-MAPK and PI3K-mTOR; its ligands have recently been identified as the leukocyte tyrosine kinase binders FAM150A and FAM150B (Hallberg and Palmer 2013; Guan et al. 2015). As with PHOX2B, a robust genotype-phenotype correlation exists: mutations that more potently activate ALK are also more highly penetrant. Across all neuroblastoma-predisposing ALK mutations in the aggregate, penetrance is estimated to be around 50% (Devoto et al. 2011; Bresler et al. 2014). Those germline mutations that most strongly activate ALK have been associated not only with neonatal-onset, multifocal neuroblastoma (F1174V), but also with severe encephalopathy associated with major feeding and breathing difficulties and poor neurologic development (both F1174V and F1245V), demonstrating ALK’s importance not only in hereditary neuroblastoma initiation but also in normal CNS development (de Pontual et al. 2011). The frequent incidence of somatic ALK mutations identical to those found in affected families further validates ALK’s central role in the development of many neuroblastomas (Bresler et al. 2014).

Fig 1. Annotated map of ALK kinase domain and kinase domain crystal structure.

Mutations identified in hereditary neuroblastoma families are shown. Slate blue, NT lobe, residues 1093-1199. Grey, CT lobe, residues 1200-1399. Cyan, P-loop, residues 1123-1128. Purple, αC-helix, residues 1157-1173. Red, catalytic loop, residues 1247-1254. Orange, A-loop, residues 1270-1299. NT, N-terminus. CT, C-terminus. Crystal structure figure produced via PyMOL software (Lee et al. 2010; Chand et al. 2013; Bresler et al. 2014).

As a constitutively active kinase expressed on the cell surface, ALK is an attractive therapeutic target for both small molecule inhibition and immunotherapy, and both modalities are currently under study in neuroblastoma. The first small molecule inhibitor to be studied, crizotinib, which abrogates aberrant ALK activity both in vitro and in vivo in neuroblastoma, was rapidly translated from preclinical study to clinical trials (Mosse et al. 2013). Despite encouraging preclinical results, crizotinib has proven effective only for a small percentage of ALK-mutant neuroblastoma patients in early clinical studies (Schonherr, Ruuth, Yamazaki, et al. 2011; Mosse et al. 2013). Alternative small molecule inhibitors and immunotherapeutic approaches are currently being explored, and additional efforts are ongoing to further identify and bypass mechanisms of resistance (Carpenter et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2016; Lu et al. 2017).

Clinical Implications

The identification of familial neuroblastoma predisposition genes has impacted screening practices for children with a family history of neuroblastoma or for those children who present with multiple primary tumors. Genetic testing for germline mutations in ALK and PHOX2B is now recommended for such patients. Recently published consensus recommendations for disease surveillance in children with family history of neuroblastoma (irrespective of ALK and PHOX2B status) suggest performing abdominal ultrasounds and chest x-rays along with urine metanephrines every three months until six years of age (Kamihara et al. 2017). In the absence of prospective studies to inform clinical practice in this area, insights from the study of familial neuroblastoma predisposition have been critical to the development of standardized clinical surveillance guidelines.

Despite considerable progress in understanding the basis of familial neuroblastoma predisposition over the last two decades, approximately 15% of familial cases remain unexplained. Outside of ALK, PHOX2B, and genes such as NF1 and SDHB driving neuroblastoma development in the context of other familial cancer predisposition syndromes, no additional familial neuroblastoma candidate genes have been identified. One notable exception, GALNT14, a glycosyltransferase implicated in several other malignancies, was identified in two second-degree cousins with neuroblastoma (De Mariano et al. 2015). However, GALNT14 has not been implicated in any other neuroblastoma families to date. Whole genome sequencing efforts are ongoing to identify additional candidate neuroblastoma predisposition genes in families without germline mutations in ALK and PHOX2B.

Sporadic Neuroblastoma

While family-based linkage studies are incredibly powerful for studying highly penetrant mutations such as ALK and PHOX2B in familial neuroblastoma, the majority of neuroblastomas arise sporadically without a family history. The introduction of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array technology in the 1990s (Wang et al. 1998) enabled the first genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the late 2000s (Hirschhorn and Daly 2005). The first pediatric cancer GWAS was carried out in 2008 in neuroblastoma, with a total of 1,752 European American neuroblastoma cases collected through the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) and 4,171 cancer-free control subjects (Maris et al. 2008). This study identified a susceptibility locus at chromosome 6p22 conferring risk for neuroblastoma development, specifically the more aggressive high-risk subset. This neuroblastoma GWAS has since been expanded as additional patient samples have been collected and now also includes multiple ethnically diverse populations. The largest neuroblastoma GWAS published to date (McDaniel et al. 2017) consisted of 3,264 cases and 8,598 controls of European and African descent, an accomplishment enabled by decades of biobanking.

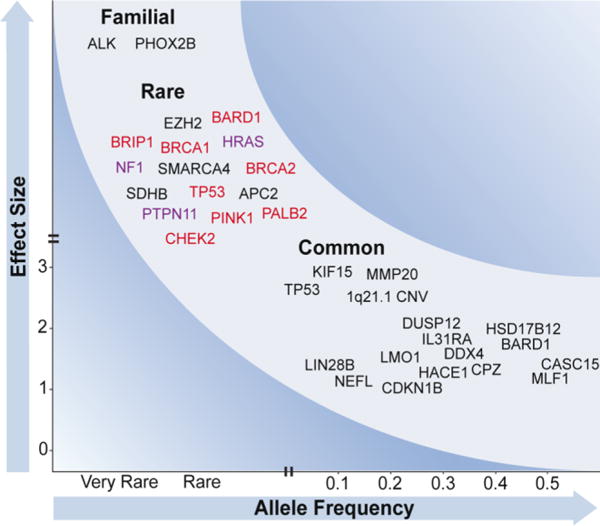

To date, several neuroblastoma susceptibility loci have been identified through this large GWAS, with candidate genes including CASC15 and NBAT-1 (Maris et al. 2008), BARD1 (Capasso et al. 2009), LMO1 (Wang et al. 2011), HSD17B12 (Nguyen et al. 2011), HACE1 and LIN28B (Diskin et al. 2012), TP53 (Diskin et al. 2014), and MLF1 and CPZ (McDaniel et al. 2017) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Functional follow-up studies have implicated many of these candidate genes as independent drivers of neuroblastoma predisposition and further have demonstrated that they can play a role not only in tumor initiation but also maintenance of the oncogenic phenotype. Additionally, several of these variants are enriched in the high- or low-risk subsets of neuroblastoma, suggesting that a given genotype can selectively predispose to the development of a specific neuroblastoma phenotype.

Table 2.

Germline neuroblastoma-associated variants identified by GWAS.

| Genomic Location |

Variant | Candidate Gene(s) |

Combined P-value |

Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) |

Reference/ Alternate Allelea |

MAFb in European Cases/ Controls |

Clinical or Biological Subset |

Populations Studiedc | Proposed Mechanism | References for Association |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA | UK | IT | AA | SC | ||||||||||

| Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (most significant SNP from the original study is shown) | ||||||||||||||

| 6p22 | rs6939340 | CASC15 and NBAT-1 | 9.3×10−15 | 1.37 (1.27–1.49) |

A/G | 0.56/0.47 | High-risk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓g | ✓ | Decreased expression (Russell et al. 2015; Pandey et al. 2014) | Maris et al. 2008; Latorre et al. 2012; Capasso et al. 2013; He, Zhang et al. 2016 |

| 2q35 | rs6435862 | BARD1 | 8.7×10−18 | 1.68 (1.49–1.90) |

T/G | 0.40/0.29 | High-risk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Expression of oncogenic isoform (Bosse et al. 2012) | Capasso et al. 2009, Latorre et al. 2012; Capasso et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016 |

| 11p15.4 | rs2168101d | LMO1 | 7.5×10−29 | 0.65 (0.60-0.70) |

G/T | 0.24/0.31 | High-risk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓g | ✓h | Increased expression (Oldridge et al. 2015) | Wang et al. 2011; Oldridge et al. 2015; He, Zhong et al. 2016 |

| 1q23.3 | rs1027702 | DUSP12e | 2.1×10−6 | 2.01 (1.47-2.79) |

C/T | Not reported | Low-risk | ✓ | ✓ | Unknown | Nguyen et al. 2011 | |||

| 11p11.2 | rs11037575 | HSD17B12e | 4.2×10−7 | 1.67 (1.35-2.08) |

C/T | Not reported | Low-risk | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Unknown | Nguyen et al. 2011; Zhang, Zou et al. 2017 | ||

| 5q11.2 | rs2619046 | DDX4e | 2.9×10−6 | 1.48 (1.21-1.79) |

C/T | Not reported | Low-risk | ✓ | ✓ | Unknown | Nguyen et al. 2011 | |||

| 5q11.2 | rs10055201 | IL31RAe | 6.5×10−7 | 1.49 (1.23-1.81) |

A/G | Not reported | Low-risk | ✓ | Unknown | Nguyen et al. 2011 | ||||

| 2q34 | rs1033069 | SPAG16f | 6.4×10−5 | Not reported | G/A | Not reported | High-risk | ✓ | ✓ | Unknown | Gamazon et al. 2013 | |||

| 6q16 | rs4336470 | HACE1 | 2.7×10−11 | 1.26 (1.18-1.35) |

C/T | 0.30/0.35 | None | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓i | Decreased expression (Diskin et al. 2012) | Diskin et al. 2012; Zhang, Zhang et al. 2017 | |

| 6q16 | rs17065417 | LIN28B | 1.2×10−8 | 1.38 (1.23-1.54) |

A/C | 0.08/0.11 | None | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓h | Increased expression (Diskin et al. 2012) | Diskin et al. 2012; He, Yang et al. 2016 | |

| 17p13.1 | rs35850753 | TP53 | 3.4×10−12 | 2.7 (2.0-3.6) |

T/C | 0.04/0.02 | None | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | rs35850753: increased expression of dominant-negative variant (Fujita et al. 2009); rs78378222: impaired polyadenylation (Stacey et al. 2011, Diskin et al. 2014) | Diskin et al. 2014 | ||

| 8p21 | rs1059111 | NEFL | 4.9×10−3 | 0.86 (0.77-0.95) |

T/A | 0.12/0.13 | None | ✓ | ✓ | Increased expression (Capasso et al. 2014) | Capasso et al. 2014 | |||

| 3q25 | rs6441201 | MLF1 and RSRC1 | 1.2×10−11 | 1.23 (1.16-1.31) |

G/A | 0.52/0.47 | None | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Increased expression of MLF1 (Lee et al. 2017) | Lee et al. 2017 | |

| 4p16 | rs3796727 | CPZ | 1.3×10−12 | 1.30 (1.21-1.40) |

G/A | 0.35/0.30 | None | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Decreased methylation (Lee et al. 2017) | Lee et al. 2017 | ||

| 12p13 | rs34330 | CDKN1B | 0.002 | 1.15 (1.06-1.24) |

C/T | 0.26/0.23 | None | ✓ | ✓ | Increased expression (Capasso et al. 2017) | Capasso et al. 2017 | |||

| 11q22.2 | rs10895322 | MMP20 | 2.6×10−9 | 2.89 (1.99-4.10) |

A/G | 0.16/0.06 | 11q deletion | ✓ | Increased expression (Chang et al. 2017) | Chang et al. 2017 | ||||

| 3p21.31 | rs80059929 | KIF15 | 6.5×10−12 | 2.95 (2.17-4.02) |

T/A | 0.09/0.04 | MYCN amplification | ✓ | Unknown | Hungate et al. 2017 | ||||

| Copy Number Variations | ||||||||||||||

| 1q21.1 | hg18: 147,292,384–147,435,422 | NBPF23 | 3.0×10−17 | 2.49 (2.02-3.05) |

143-kb deletion | 0.16/0.09 | None | ✓ | Unknown | Diskin et al. 2009 | ||||

Risk allele is displayed in bold.

MAF=Minor Allele Frequency.

Association replicated unless otherwise noted. EA = European American, UK = United Kingdom, IT = Italian, AA = African American, SC = Southern Chinese.

This was not the top SNP in the original study, but was demonstrated as the causal SNP in Oldridge et al. 2015.

Gene-based study: p-values were calculated at the gene level rather than the SNP level, and allele frequencies were not provided.

Case-only study (association with high-risk neuroblastoma was tested): odds ratio and control MAF were not reported.

This association did not replicate.

A different SNP at the same locus was analyzed.

Association represents a combined analysis of five SNPs.

Figure 2. Frequency and effect size of neuroblastoma-associated mutations.

Variants contributing to neuroblastoma risk range from rare variants of large effect to common variants of small effect. (Top left) Familial mutations in ALK and PHOX2B have been identified through linkage-based studies and evaluation of cases with associated conditions. Other rare damaging variants in cancer-associated genes have been observed in sporadic neuroblastoma by sequencing, but their true frequency and impact is unknown. Several mutations affect genes involved in DNA repair (red) and Ras-MAPK signaling (purple). (Bottom right) Common polymorphisms identified through GWAS predispose to sporadic neuroblastoma, likely through cooperative effects. These variants are plotted at the observed minor allele frequencies and odds ratios.

CASC15 and NBAT-1 (CASC14)

In the first neuroblastoma GWAS, the only locus reaching genome-wide significance was chromosome 6p22, with three significant SNPs (Maris et al. 2008). The association was observed in a European American discovery cohort and subsequently replicated in cohorts from the United Kingdom (Maris et al. 2008), Italy (Capasso et al. 2013), and Southern China (He, Zhang, et al. 2016) cohorts, but not in African Americans (Latorre et al. 2012). Homozygosity for the risk allele was associated with characteristics of high-risk disease, including metastatic stage 4 disease, MYCN amplification, relapse, and decreased event-free survival (Maris et al. 2008). At the time of discovery, this locus contained two predicted transcripts of unknown significance (FLJ22536 and FLJ44180); these transcripts have since been identified as long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) and termed cancer susceptibility 15 (CASC15; also known as LINC00340) and neuroblastoma associated transcript 1 (NBAT-1; also known as CASC14 or LOC729177), respectively. CASC15 consists of multiple isoforms; the shorter NBAT-1 transcript overlaps with CASC15 on the antisense strand (Russell et al. 2015).

Two recent studies sought to characterize the roles of NBAT-1 (Pandey et al. 2014) and CASC15 (Russell et al. 2015) in neuroblastoma, which were each identified as a top hit in lncRNA differential expression analyses between high- and low-risk neuroblastoma tumors in the respective studies. A short isoform of CASC15, CASC15-S, was determined to be the predominant CASC15 transcript, expressed 40-fold higher than full-length CASC15 and 20-fold higher than NBAT-1. Expression of both CASC15-S and NBAT-1 was decreased in high-risk disease, and knockdown of either transcript in neuroblastoma cells increased proliferative and invasive qualities and impaired differentiation. For NBAT-1, this phenotype was attributed to loss of an interaction between NBAT-1 and the PRC2 complex member EZH2, resulting in decreased H3K27 trimethylation at relevant gene promoters. Conversely, overexpression of NBAT-1 in neuroblastoma cells induced differentiation. Together, these data suggest that both transcripts act as tumor suppressors in neuroblastoma.

SNP imputation facilitated fine-mapping of the association region to a 34.9-kb linkage disequilibrium (LD) block containing 32 significant SNPs and overlapping with both the CASC15-S and NBAT-1 genes (Russell et al. 2015). Causal SNPs were postulated in both studies: Pandey et al. found that one of the original three neuroblastoma-associated SNPs, rs6939340, correlated with lower NBAT-1 expression in high-risk tumors and in neuroblastoma cell lines. They identified enhancer marks surrounding the SNP and observed an interaction between this region and the NBAT-1 promoter, which was lost in cells with the risk genotype. Russell et al. found no association between any SNPs and the expression of NBAT-1, CASC15, or CASC15-S; however, a candidate causal SNP (rs9295534) was suggested from among the 32 significant SNPs in the LD block due to its co-localization with enhancer marks and evolutionary conservation. The rs9295534 risk allele decreased expression in a reporter-based assay, suggesting that it disrupts the enhancer activity of the region.

Further studies are warranted to understand the functional effects of these candidate SNPs on CASC15 and NBAT-1 expression, as well as any potential interactions of these tumor suppressor genes with each other and with additional neuroblastoma predisposition mechanisms. Several candidates for cis-interaction are located near or within these transcripts, including an enhancer involved in murine neural tube development, hs1335, (Visel et al. 2007) and the developmental regulator SOX4 (Potzner et al. 2010). It was recently demonstrated that CASC15 increases SOX4 expression in acute leukemia (Fernando et al. 2017), supporting a potential cis-regulatory mechanism in neuroblastoma. Although the complex regulatory mechanisms at the neuroblastoma-associated chromosome 6p22 locus have yet to be elucidated, these studies have highlighted the power of GWAS to identify previously unknown genes, including lncRNAs, which are integral to developmental and cancer-associated pathways.

BARD1

The enrichment of chromosome 6p22 risk alleles in high-risk neuroblastoma patients motivated additional studies focusing on susceptibility specific to high-risk disease. In a GWAS restricted to high-risk patients, a strong association with high-risk disease was identified in the BRCA1-associated ring domain 1 (BARD1) gene located at chromosome 2q35 (Capasso et al. 2009). BARD1 forms a stabilizing heterodimer with BRCA1 and is integral in BRCA1-mediated DNA-damage repair and tumor suppression (Wu et al. 1996). Six neuroblastoma-associated SNPs falling within introns 1, 3, and 4 of the BARD1 gene were identified in European Americans and found to be in strong LD. The association at this locus replicated in a cohort from the United Kingdom (Capasso et al. 2009) as well as African Americans (Latorre et al. 2012), Italians (Capasso et al. 2013), and Southern Chinese (Zhang et al. 2016). The breakdown of LD in the African American cohort facilitated further fine-mapping of this locus to a smaller candidate disease-causal region (Latorre et al. 2012). Although BARD1 has been classically thought of as a tumor suppressor, recent evidence has accumulated that alternative splicing can lead to the expression of oncogenic BARD1 isoforms which may function independently of BRCA1 (Li, Cohen, et al. 2007; Li, Ryser, et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2012; Lepore et al. 2013). In neuroblastoma, risk alleles at BARD1 were found to correlate with the expression of the oncogenic isoform BARD1β (Bosse et al. 2012), suggesting that neuroblastoma-associated variants may alter binding sites for splicing enhancers or other modifiers, although the causal SNPs and exact mechanisms of disease-associated common variant effect on BARD1 splicing remain unclear to date.

Importantly, BARD1β has been shown to be an oncoprotein in neuroblastoma models. Knockdown of BARD1β by siRNA in neuroblastoma cells homozygous for the risk alleles decreased proliferation, anchorage-independent growth, and foci formation; whereas cells with the non-risk allele were not dependent on BARD1β (Bosse et al. 2012). BARD1β was found to stabilize Aurora kinase A (AURKA), a kinase which stabilizes the neuroblastoma oncoprotein MYCN and has been effectively targeted with small molecules in early phase preclinical studies (Otto et al. 2009; Mossé et al. 2012). Accordingly, overexpression of BARD1β in mouse embryonic fibroblasts resulted in malignant transformation, which was mitigated by depletion of Aurora kinase A or B (Bosse et al. 2012). Taken together, these data suggest BARD1 is not only integral to neuroblastoma initiation but also the maintenance of a malignant phenotype in established tumors. Notably, rare BARD1 coding mutations also arise somatically and in the germline (Pugh et al. 2013) (see Rare Variants).

LMO1

An expanded 2011 GWAS in Caucasian children from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy (Wang et al. 2011) facilitated the identification of a third neuroblastoma risk locus at chromosome 11p15.4 in close proximity to the LIM-domain only 1 gene (LMO1). LMO1 is part of a family of transcriptional cofactors which contain two zinc-finger LIM domains and promote the nucleation of transcription factor complexes (Sánchez-García and Rabbits 1994). All four LMO genes have previously been implicated in cancer: LMO1 and LMO2 are overexpressed in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a result of chromosomal abnormalities (Boehm et al. 1988; Royer-Pokora, Loos, and Ludwig 1991) and other mechanisms (Ferrando et al. 2002), LMO4 is overexpressed in breast cancer (Visvader et al. 2001) and represses transcription of BRCA1 (Sum et al. 2002), and LMO3 was previously proposed as an oncogene in neuroblastoma (Aoyama et al. 2005). LMO1 was therefore hypothesized as a candidate neuroblastoma oncogene given this GWAS association and its position on 11p, a region which is recurrently amplified in neuroblastomas (Wang et al. 2011). Indeed, risk alleles at LMO1 and 11p amplification were associated with increased expression of LMO1 in cell lines and tumors. Additionally, silencing of LMO1 inhibited growth of neuroblastoma cells expressing high endogenous levels of the gene, while forced overexpression enhanced growth in low-expressing cells. Similar to the associations at 6p22 and 2q35, the risk alleles were enriched in high-risk tumors.

In a follow-up study, a G>T SNP in the first intron of LMO1 (rs2168101) was found to disrupt a GATA transcription factor binding site, decreasing LMO1 expression and resulting in decreased risk of neuroblastoma (Oldridge et al. 2015). Additionally, a super-enhancer specific to neuroblastoma cells was identified at this disease-associated region. Unbalanced expression of LMO1 biased toward the risk allele (G) further supported the cis regulation of this locus by differential GATA binding. Finally, knockdown of GATA3 decreased LMO1 expression and suppressed growth of cells harboring the G allele. Interestingly, the newly evolved protective T allele at rs2168101 is very rare in African populations, indicating that it must have emerged recently in European and East Asian populations; this neuroblastoma association replicated in multiple Chinese populations (Lu et al. 2015; He, Zhong, et al. 2016; Zhang, Lin, et al. 2017) but not African Americans (Oldridge et al. 2015).

Recently, additional data has emerged supporting the importance of LMO1 in neuroblastoma tumorigenesis, as a synergy between LMO1 and MYCN was identified in neuroblastoma zebrafish models (Zhu et al. 2017). While transgenic expression of MYCN in zebrafish induced neuroblastoma development in 20-30% of fish, co-expression of both MYCN and LMO1 robustly increased the penetrance to 80%; interestingly, LMO1 alone did not cause tumor initiation. These data support the framework that GWAS loci and other neuroblastoma-associated genomic events collectively modify the risk of neuroblastoma development.

HACE1 and LIN28B

With the accrual of additional patient samples, this neuroblastoma GWAS identified two independent association signals at chromosome 6q16 within the genes lin28 homolog B (LIN28B) and HECT domain and ankyrin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (HACE1) (Diskin et al. 2012), which had both been previously implicated in cancer as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor, respectively.

HACE1 controls growth and apoptosis by repressing the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) (Zhao et al. 2009) and targeting the GTPase Rac1 for degradation (Torrino et al. 2011), thereby preventing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cyclin D1-driven proliferation (Daugaard et al. 2013). Silencing of HACE1 via epigenetic mechanisms or structural variation has been reported in Wilms’ tumor (Anglesio et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2007), colorectal cancer (Hibi et al. 2008), gastric carcinoma (Sakata et al. 2009), and B cell lymphomas (Bouzelfen et al. 2016). In addition to these somatic events, a germline t(5;6)(q21;q21) translocation was identified in a patient with Wilms tumor (Slade et al. 2010). Interestingly, HACE1 was recently reported as the causal gene in two families with a recessive neurodevelopmental disorder (Hollstein et al. 2015). HACE1 knockout mice were shown to form a variety of spontaneous tumors, and in the same study HACE1 inhibited anchorage-independent growth in a neuroblastoma cell line, further supporting a possible tumor suppressive function in neuroblastoma (Zhang et al. 2007).

LIN28B is an RNA-binding protein that is known for its repression of the let-7 family of miRNAs, which target oncogenes including RAS and c-MYC (Johnson et al. 2005; Sampson et al. 2007). Both LIN28B and its homolog LIN28A (also called LIN28) have been well characterized as oncogenes (Viswanathan et al. 2009). They suppress the let-7 miRNA family through different mechanisms: while LIN28A blocks processing of let-7 pre-miRNAs by Dicer in the cytoplasm, LIN28B sequesters pri-miRNAs in the nucleus and inhibits their processing by Drosha (Piskounova et al. 2011). Amplification or overexpression of LIN28B has been reported in germ cell tumors, hepatocellular carcinoma, leukemia, and Wilms’ tumors, and correlates with low let-7 levels (West et al. 2009; Viswanathan et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2010). Additionally, LIN28 has also been shown to regulate neurodevelopment (Balzer et al. 2010).

In the neuroblastoma GWAS, rs4336470 and other SNPs were identified within an LD block overlapping the HACE1 gene, while an additional SNP (rs17065417) within LIN28B constituted an independent association signal (Diskin et al. 2012). Both signals associated with neuroblastoma in Caucasian children from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy (Diskin et al. 2012) as well as African Americans (Diskin et al. 2012) and Southern Chinese (Zhang, Zhang, et al. 2017; He, Yang, et al. 2016). Unlike the previous GWAS loci, SNPs at 6q16 displayed no correlation with neuroblastoma risk group; however, low expression of HACE1 and high expression of LIN28B associated with high risk tumors and worse survival, consistent with a role for HACE1 as a neuroblastoma tumor suppressor and LIN28B as an oncogene. Genotype at the HACE1 locus did not correlate with HACE1 expression, but homozygosity for risk alleles at rs17065417 within LIN28B correlated with increased LIN28B, decreased let-7, and increased MYCN expression. Importantly, LIN28B knockdown inhibited growth in neuroblastoma cellular models carrying the risk allele at rs17065417 (Diskin et al. 2012).

Further mechanistic studies showed that LIN28B promotes neuroblastoma tumorigenesis through its effects on both MYCN and AURKA, the same kinase which was previously implicated in the oncogenic function of BARD1β (Bosse et al. 2012). LIN28B expression decreases let-7 levels, resulting in a de-repression of MYCN; this induced the development of MYCN-expressing neuroblastoma tumors in mice (Molenaar et al. 2012). Additionally, LIN28B promotes signaling of the GTPase Ras-associated nuclear protein (RAN), both by mitigating let-7 targeting of RAN and by directly binding RAN mRNA (Schnepp et al. 2015). RAN induces the phosphorylation of AURKA, which was also found to be a let-7 target. This demonstrates that LIN28B signaling converges on MYCN and AURKA through multiple mechanisms, revealing a potential therapeutic avenue for combinatorial trials targeting LIN28B-controlled pathways in neuroblastoma (Schnepp and Diskin 2016). Additionally, aberrant LIN28B/let-7 signaling was also recently discovered to promote glycolytic metabolism in neuroblastoma (Lozier et al. 2015), revealing a novel vulnerability to the ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor difluoromethylornithine (DMFO) which is currently in clinical trials for neuroblastoma (Bassiri et al. 2015).

Although the causal SNPs at the chromosome 6q16 neuroblastoma susceptibility locus and their role in regulating gene expression remain to be identified, taken together, these data revealed the oncogenic and likely tumor suppressive roles of LIN28B and HACE1, respectively, in neuroblastoma. Furthermore, these studies enabled the subsequent elucidation of a complex and potentially druggable signaling network orchestrated by LIN28B in neuroblastoma tumors.

Other Common Variants

Several other loci have been identified through GWAS but have not yet been characterized at the same level of detail as the above neuroblastoma associations. First, by restricting analysis to patients with low-risk disease, three low-risk susceptibility loci were identified: DUSP12 at 1q23.3, DDX4 and IL31RA at 5q11.2, and HSD17B12 at 11p11.2 (Nguyen et al. 2011). In this study, association was tested at the gene level in order to increase power by capturing the combined signal of moderate-effect SNPs. High and low-risk neuroblastomas had distinct gene-level association scores and gene set enrichments, again supporting the proposition that genetic architecture can predispose not only to developing neuroblastoma, but also to particular clinically relevant neuroblastoma subsets.

A case-only study of African American and European American neuroblastoma patients identified a novel risk variant (rs1033069) at sperm associated antigen 16 (SPAG16) which associated with high-risk disease in both populations (Gamazon et al. 2013). The risk allele was more frequent in African Americans and was suggested to contribute to the ethnic disparities in neuroblastoma outcome observed between African and European populations: conditioning on rs1033069 reduced the statistical significance of the association between population and the high-risk phenotype and worse survival.

Hypothesizing that common genetic variants with only moderate effect may have been undetectable in previous GWAS due to the multiple testing burden, a candidate gene analysis was carried out on eight genes selected a priori based on their known involvement in neuroblastoma development (Capasso et al. 2014). A protective minor allele at 8p21 was found to increase neurofilament light (NEFL) expression. High expression of NEFL in patient tumors correlated with enhanced survival, and NEFL overexpression in neuroblastoma cells inhibited proliferation, supporting the protective role of this known tumor suppressor (Calmon et al. 2015; Peng et al. 2015) in neuroblastoma development and progression. A second candidate gene analysis identified a neuroblastoma-associated SNP in cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B) (Capasso et al. 2017), a gene encoding the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 which shows reduced expression in cancers yet is rarely mutated (Kawamata et al. 1995; Chu, Hengst, and Slingerland 2008). CDKN1B had previously been shown to regulate proliferation and differentiation in neuroblastoma cells (Borriello et al. 2000; Wallick et al. 2005). The risk allele at 12p13 decreased expression of CDKN1B, and lower expression was observed in high-risk disease (Capasso et al. 2017). Although these candidate gene studies cannot identify novel loci, they can reveal genetic susceptibility in genes thought to be relevant to the disease, aiding in risk stratification and prioritization of neuroblastoma relevant genes for further study.

The most recent neuroblastoma GWAS identified novel variants at 3q25 and 4p16 (McDaniel et al. 2017). The initial discovery first made in European Americans was then replicated in an African American cohort and two other Caucasian cohorts from Italy and the United Kingdom, supporting a robust association. The 4p16 signal falls within carboxypeptidaze Z (CPZ), which has been shown to modulate Wnt signaling in chick embryos (Moeller et al. 2003) and at the epiphyseal plate (Wang, Shao, and Ballock 2009). One SNP at this locus was found to influence the methylation status at CPZ in healthy individuals (McDaniel et al. 2017). The 3q25 signal falls within arginine/serine-rich coiled-coil 1 (RSRC1) and upstream of myeloid leukemia factor 1 (MLF1). RSRC1 is a regulator of splicing (Cazalla, Newton, and Cáceres 2005) with involvement in brain development and schizophrenia (Potkin et al. 2009), and a related gene, RSRC2, was proposed as a tumor suppressor in esophageal cancer (Kurehara et al. 2007). MLF1 has been identified as either an oncogene or a tumor suppressor depending on the context: MLF1 is overexpressed in acute myeloid leukemia (Matsumoto et al. 2000) and lung cancer (Sun et al. 2004) and is thought to suppress the CDK inhibitor CDKN1B described above, promoting proliferation (Winteringham et al. 2004). However, MLF1 also reduces cell proliferation through the stabilization of p53 in other contexts (Yoneda-Kato et al. 2005). Preliminary evidence in neuroblastoma seems to implicate it as an oncogene, since silencing of MLF1 decreased growth of neuroblastoma cells (McDaniel et al. 2017). One SNP at 3q25 associates with increased MLF1 expression in neuroblastoma cells, while a different SNP influences the expression of RSRC1 and a recently discovered lncRNA, LOC100996447, across multiple tissues (McDaniel et al. 2017). Further study is needed to assess the role of these genes in the initiation and/or maintenance of neuroblastomas.

Genome-wide approaches can be used not only to compare genetic events between cases and controls or among different risk groups, but also between subsets of disease carrying distinct genetic events. A recent study found that common variants in the Matrix metalloproteinase 20 (MMP20) gene at chromosome 11q22.2 were enriched in patients with chromosome 11q deletion (Chang et al. 2017), a somatic event which inversely correlates with MYCN amplification yet independently predicts poor outcome in neuroblastoma patients (Attiyeh, London, Mosse, et al. 2005). The lead SNP rs10895322 (A>G) was associated with decreased MMP20 expression in 11q-deleted neuroblastomas (genotypes of A/- and G/-) but not in non-deleted neuroblastomas (A/A and G/A). Another recent study identified a susceptibility locus specific to MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma: a SNP at 3p21.31 (rs80059929) within KIF15 was enriched in MYCN-amplified high-risk patients but not non-amplified high-risk patients relative to non-amplified, non-high-risk controls (Hungate et al. 2017). This approach can be extended to identify other potential interactions between common variants and somatic events.

Finally, common copy number variation (CNV) has also been implicated in neuroblastoma predisposition. A genome-wide analysis of common CNVs in 846 Caucasian neuroblastoma patients and 803 healthy controls revealed association of an approximately 140-kb deletion at 1q21.1 with neuroblastoma (Diskin et al. 2009). This deletion was observed to be inherited in 713 cancer-free parent-child trios. A novel transcript was found within the deletion region and named NBFP23 due to its homology to the neuroblastoma breakpoint family (NBPF) genes. The first NBPF gene, NBPF1, was identified as the target of a germline translocation in a neuroblastoma patient (Vandepoele et al. 2008) and was shown to possess tumor-suppressive qualities (Vandepoele et al. 2008; Andries et al. 2015). Conversely, overexpression of NBPF genes has been reported in sarcomas and non-small-cell lung cancer, indicating that these genes may also have oncogenic properties (Meza-Zepeda et al. 2002; Petroziello et al. 2004). Structural variations affecting NBPF also occur in schizophrenia and autism (Walsh et al. 2008; Stefansson et al. 2008). The function of this gene family is unknown, but they were recently identified as transcription factors regulated by NF-κB (Zhou et al. 2013). Further investigation into the role of these understudied genes in cancer and neurodevelopmental disorders is needed. Furthermore, additional insights into germline predisposition to neuroblastoma could be gained through a larger study of disease-associated copy number variations.

Rare Variants

Unlike many adult cancers with recurrent, disease-defining somatic mutations driving tumorigenesis, diagnostic neuroblastomas have few recurrent somatic mutations (Pugh et al. 2013). This paucity of somatic alterations renders the development of precision-targeted therapeutics aimed at recurrently mutated oncogenes challenging. While GWAS approaches have discovered several common alleles associated with neuroblastoma and revealed important oncogenic vulnerabilities, GWAS-defined variants all have a modest effect size, and these alleles in isolation are not sufficient to cause disease. In contrast, rare germline variants with a minor allele frequency under 1% in the general population may have a higher effect size and thus contribute more significantly to neuroblastoma initiation than GWAS-defined common polymorphisms (Schork et al. 2009). Extensive next-generation germline sequencing efforts have recently been undertaken to identify such variants across childhood cancers, including neuroblastoma (Zhang et al. 2015; Parsons et al. 2016).

Despite the relative rarity of somatic TP53 mutations in neuroblastoma, the prototypical tumor suppressor was among the first genes identified to have rare neuroblastoma-predisposing variants. This association was first noted in a 1994 analysis that detected two germline variants in a series of twenty cases, though their relevance to pathogenesis was unclear at the time (Hosoi et al. 1994). More recent case reports and genome sequencing analyses have provided compelling evidence that rare TP53 germline mutants indeed contribute to neuroblastoma initiation (Rossbach et al. 2008; Abecasis et al. 2010; Courtney and Ranganathan 2015). Analysis of 10,290 individuals across three independent case-control cohorts identified two SNPs, rs78378222 and rs35850753, very strongly associated with neuroblastoma predisposition (Diskin et al. 2014). Interestingly, the rs78378222 SNP has been noted in whole-genome sequencing of patients with prostate cancer, glioma, colorectal adenoma, and cutaneous basal cell carcinoma. This SNP maps to the 3′ untranslated region of TP53 and disrupts its polyadenylation signal, destabilizing the TP53 transcript and resulting in p53 haploinsufficiency (Stacey et al. 2011; Diskin et al. 2014). The rs35850753 SNP maps to the 5′ UTR of the Δ133 isoform, a truncated p53 variant that acts uniquely as an oncogene via dominant-negative inhibition of full-length p53 (Fujita et al. 2009). Thus, this SNP may predispose to neuroblastoma by causing disproportionate transcription or aberrant mRNA stabilization of the oncogenic Δ133p53 variant.

In 2013, Pugh et al. published the results of extensive whole genome, exome, and transcriptome sequencing of 240 high-risk neuroblastoma tumors, along with accompanying normal tissue samples for some patients. In addition to re-demonstrating the TP53 association previously observed, this analysis also showed enrichment of rare germline variants in CHEK2, PINK1, and BARD1 (Pugh et al. 2013). The BARD1 discovery was particularly noteworthy given the known association between common variants at the BARD1 locus and neuroblastoma predisposition; additional potentially pathogenic neuroblastoma-associated BARD1 germline variants have since been reported elsewhere (Mody et al. 2015). Other rare germline variants possibly contributing to neuroblastoma predisposition have been reported in the context of genetic syndromes; these include NF1 in neurofibromatosis type 1 (Origone et al. 2003), PTPN11 in Noonan syndrome (Mutesa et al. 2008; Kratz et al. 2011), HRAS in Costello syndrome HRAS (Kratz et al. 2011), TP53 in Li Fraumeni syndrome (Birch et al. 2001), EZH2 in Weaver syndrome (Tatton-Brown et al. 2013), and SDHB in familial paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma (Schimke, Collins, and Stolle 2010).

Additional rare germline variants have been uncovered via whole genome and exome sequencing of neuroblastoma patients; these include SMARCA4, BRCA1 (Parsons et al. 2016), APC, and BRCA2 (Zhang et al. 2015). The latter two gene variants were identified in a seminal 2015 New England Journal of Medicine study that employed next-generation sequencing to characterize the genomes of more than 1000 children with cancer; this study also re-demonstrated neuroblastoma-associated germline mutations in ALK and SDHB (Zhang et al. 2015). Surprisingly, that study reported that 8.5% of childhood cancer patients harbored germline mutations across 60 genes thought to predispose to cancer, a much higher rate than had previously been appreciated (Zhang et al. 2015). An even greater proportion of these patients carried germline variants of unknown significance, with a possible contribution to neoplastic transformation. Notably, several of the rare variants identified are in genes critical for DNA repair and maintenance of genomic integrity, including BRCA1, BRCA2, BARD1, and PALB2. A 2017 case report described another child with neuroblastoma who carried a germline BRCA2 mutation (Walsh et al. 2017). Whether these variants contribute to neuroblastoma pathogenesis or cancer predisposition later in life has yet to be elucidated.

Extremely rare chromosomal abnormalities have also been observed in the germline of neuroblastoma patients, usually occurring with congenital abnormalities and intellectual disability. Large deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations have been identified by clinical genomic analyses including karyotyping and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Certain events such as subtelomeric deletion of chromosome 1p36 (White et al. 2004; Isidor et al. 2008), interstitial deletion of chromosome 11q (Mosse et al. 2003; Passariello et al. 2013; Shiohama et al. 2016), and duplication of a critical region on chromosome 2p24.3 (Morgenstern et al. 2014) have been observed in the germline of multiple neuroblastoma patients, while other isolated cases involving 3p26.3 (Pezzolo et al. 2017), 9p21 (Satgé et al. 2003), 14q23 (Lehalle et al. 2014), 17p11.2 (Hienonen et al. 2005), 17q11.2 (Van Roy et al. 2002; Vandepoele et al. 2008), and 17q12-21 (Laureys et al. 1990) have also been observed. Other reported events include a Robertsonian translocation involving chromosomes 13 and 14 and a case of mosaic monosomy 22 (Satgé et al. 2003). Several of the recurrently observed events constitute established genomic syndromes, notably monosomy 1p36, partial trisomy 2p, and 11q interstitial deletion syndrome. These regions have also been implicated in neuroblastoma, where somatic loss of 1p and 11q and gain of 2p are frequently observed (Attiyeh, London, Mossé, et al. 2005; Pugh et al. 2013). Notably, in one paper that reviewed seven reported cases of partial trisomy 2p, the duplicated region on 2p23 included both ALK and MYCN in six of the cases and only MYCN in the seventh (Morgenstern et al. 2014). Given the known involvement of these regions in neuroblastoma, it is likely that these rare constitutional abnormalities contribute to neuroblastoma pathogenesis. Additionally, neuroblastoma seems to be overrepresented in Turner syndrome (monosomy X) but underrepresented in triple X syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome (XXY), and Down syndrome, suggesting that some genes on the X chromosome and chromosome 21 may be protective against neuroblastoma (Blatt et al. 1997; Satgé et al. 1998; Satgé et al. 2001; Satgé et al. 2003). In Down syndrome, it has been hypothesized that overproduction of the S100B protein, which induces neuronal differentiation, protects against neuroblastoma (Satgé 1996).

Discussion and Future Directions

Over the past two decades, immense progress has been made toward describing the genetics and genomics of neuroblastoma predisposition. These insights have stemmed from the study of both familial and sporadic disease. While only a small fraction of neuroblastomas occur within families, our evolving understanding of the mutations driving heritable disease has presented opportunities for targeted therapies in patients with sporadic neuroblastoma. Studies aiming to understand the epistatic interactions that drive varying penetrance and disease severity within affected families are ongoing.

Similarly, the GWAS approach has enabled tremendous advances toward understanding the predisposition to sporadic disease, including the tumor suppressive roles of NBAT-1 and CASC15, the oncogenic role of BARD1’s β isoform, synergy between LMO1 and MYCN promoting neuroblastoma development and metastasis, and the tumor-promoting properties of the LIN28B/let-7/AURKA signaling axis, among many others. The replication of GWAS associations across multiple populations serves to further support the role of these and other genes in neuroblastoma predisposition. Still, the functional significance of several loci remains to be characterized, and only for the LMO1 association has a true causal SNP been determined with confidence. In order to fully understand the pathologic relevance of these loci, their roles in epigenetic regulation must be studied in more detail. The fact that the most significant locus observed in neuroblastoma by GWAS contains two lncRNAs highlights the importance of the noncoding genome in neuroblastoma development. In particular, several lncRNAs have been identified near genes that regulate neural crest development (Knauss and Sun 2013). Ultimately, the identification and functional characterization of GWAS loci will provide information that can be harnessed for the development of therapies for novel targets and the application of existing therapies to neuroblastoma.

Beyond single nucleotide variants, genome-wide analysis was also used to identify a common copy number variation at 1q21.1 enriched in neuroblastoma. As CNVs generally have much larger effect sizes than SNPs, it is important to assess whether other significant neuroblastoma-associated CNVs might be observed at lower frequencies; rare germline CNVs have previously been reported in other cancers (Park et al. 2015). To address this, CNVs must be analyzed in a large cohort of neuroblastoma patients, and the functional relevance of any identified variants should be assessed. Additionally, other types of germline structural variation, including inversions and translocations not visible by karyotyping or SNP genotyping, have not yet been studied in neuroblastoma; these variants, if they exist, could be identified through whole-genome sequencing approaches.

As next-generation sequencing technology makes whole exome and genome sequencing for all pediatric cancer patients clinically feasible, determining the true frequency of rare germline variants in cancer predisposition genes, if and how these variants contribute to tumorigenesis, and how they impact risk stratification will be a critical priority. Efforts are ongoing to assess the functional impact of potentially pathogenic germline variants in neuroblastoma and other pediatric malignancies; the question remains whether these variants have true relevance in the development of these cancers, or whether they are simply passenger lesions. Because certain rare variants identified in neuroblastoma have FDA-approved targeted therapies available (e.g. PARP inhibition for patients with loss-of-function mutations in DNA repair genes), distinguishing the true driver germline genetic lesions may directly impact therapeutic decision-making. Additionally, characterizing these variants more thoroughly will clarify whether their identification should inform screening and surveillance for family members. A related future direction entails understanding whether rare neuroblastoma-predisposing variants are inherited or whether they occur de novo (or both); this important question could be addressed using trio-based studies.

While family-based studies and GWAS have contributed much to our understanding of the genetic basis of neuroblastoma, the rapid expansion of genomic techniques will enable even greater leaps in the coming years. As existing technologies become more accessible and novel approaches are developed, the related goals of understanding neuroblastoma’s genetic architecture and developing personalized therapies should become increasingly attainable.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

L.E.R. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Training Grant T32GM008216. M.P.R was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Medical Research Fellows Program. K.R.B. is a Damon Runyon Physician-Scientist supported (in part) by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (PST-07-16).

References

- Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiel J, Laudier B, Attie-Bitach T, Trang H, de Pontual L, Gener B, Trochet D, Etchevers H, Ray P, Simonneau M, Vekemans M, Munnich A, Gaultier C, Lyonnet S. Polyalanine expansion and frameshift mutations of the paired-like homeobox gene PHOX2B in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:459–61. doi: 10.1038/ng1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andries Vanessa, Vandepoele Karl, Staes Katrien, Berx Geert, Bogaert Pieter, Van Isterdael Gert, Ginneberge Daisy, Parthoens Eef, Vandenbussche Jonathan, Gevaert Kris, van Roy Frans. NBPF1, a tumor suppressor candidate in neuroblastoma, exerts growth inhibitory effects by inducing a G1 cell cycle arrest. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:391. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglesio MS, Evdokimova V, Melnyk N, Zhang L, Fernandez CV, Grundy PE, Leach S, Marra MA, Brooks-Wilson AR, Penninger J, Sorensen PH. Differential expression of a novel ankyrin containing E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, Hace1, in sporadic Wilms’ tumor versus normal kidney. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2061–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama Mineyoshi, Ozaki Toshinori, Inuzuka Hiroyuki, Tomotsune Daihachiro, Hirato Junko, Okamoto Yoshiaki, Tokita Hisashi, Ohira Miki, Nakagawara Akira. LMO3 Interacts with Neuronal Transcription Factor, HEN2, and Acts as an Oncogene in Neuroblastoma. Cancer Research. 2005;65:4587. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong AE, Weese-Mayer DE, Mian A, Maris JM, Batra V, Gosiengfiao Y, Reichek J, Madonna MB, Bush JW, Shore RM, Walterhouse DO. Treatment of neuroblastoma in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome with a PHOX2B polyalanine repeat expansion mutation: New twist on a neurocristopathy syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:2007–10. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attiyeh EF, London WB, Mosse YP, Wang Q, Winter C, Khazi D, McGrady PW, Seeger RC, Look AT, Shimada H, Brodeur GM, Cohn SL, Matthay KK, Maris JM, Group Children’s Oncology Chromosome 1p and 11q deletions and outcome in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2243–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attiyeh Edward F, London Wendy B, Mossé Yael P, Wang Qun, Winter Cynthia, Khazi Deepa, McGrady Patrick W, Seeger Robert C, Look A Thomas, Shimada Hiroyuki, Brodeur Garrett M, Cohn Susan L, Matthay Katherine K, Maris John M. Chromosome 1p and 11q Deletions and Outcome in Neuroblastoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:2243–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzer Erica, Heine Christian, Jiang Qiang, Lee Vivian M, Moss Eric G. LIN28 alters cell fate succession and acts independently of the let-7 microRNA during neurogliogenesis in vitro. Development. 2010;137:891. doi: 10.1242/dev.042895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassiri Hamid, Benavides Adriana, Haber Michelle, Gilmour Susan K, Norris Murray D, Hogarty Michael D. Translational development of difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) for the treatment of neuroblastoma. Translational Pediatrics. 2015;4:226–38. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2015.04.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry-Kravis EM, Zhou L, Rand CM, Weese-Mayer DE. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome: PHOX2B mutations and phenotype. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1139–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-305OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch JM, Alston RD, McNally RJ, Evans DG, Kelsey AM, Harris M, Eden OB, Varley JM. Relative frequency and morphology of cancers in carriers of germline TP53 mutations. Oncogene. 2001;20:4621–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt Julie, Olshan Andrew F, Lee Peter A, Ross Judith L. Neuroblastoma and related tumors in Turner’s syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1997;131:666–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm T, Baer R, Lavenir I, Forster A, Waters JJ, Nacheva E, Rabbitts TH. The mechanism of chromosomal translocation t(11;14) involving the T-cell receptor C delta locus on human chromosome 14q11 and a transcribed region of chromosome 11p15. The EMBO Journal. 1988;7:385–94. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeva V, Louis-Brennetot C, Peltier A, Durand S, Pierre-Eugene C, Raynal V, Etchevers HC, Thomas S, Lermine A, Daudigeos-Dubus E, Geoerger B, Orth MF, Grunewald TGP, Diaz E, Ducos B, Surdez D, Carcaboso AM, Medvedeva I, Deller T, Combaret V, Lapouble E, Pierron G, Grossetete-Lalami S, Baulande S, Schleiermacher G, Barillot E, Rohrer H, Delattre O, Janoueix-Lerosey I. Heterogeneity of neuroblastoma cell identity defined by transcriptional circuitries. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1408–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borriello Adriana, Della Pietra Valentina, Criscuolo Maria, Oliva Adriana, Tonini Gian Paolo, Iolascon Achille, Zappia Vincenzo, Della Ragione Fulvio. p27Kip1 accumulation is associated with retinoic-induced neuroblastoma differentiation: evidence of a decreased proteasome-dependent degradation. Oncogene. 2000;19:51–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse Kristopher R, Diskin Sharon J, Cole Kristina A, Wood Andrew C, Schnepp Robert W, Norris Geoffrey, Nguyen Le B, Jagannathan Jayanti, Laquaglia Michael, Winter Cynthia, Diamond Maura, Hou Cuiping, Attiyeh Edward F, Mosse Yael P, Pineros Vanessa, Dizin Eva, Zhang Yongqiang, Asgharzadeh Shahab, Seeger Robert C, Capasso Mario, Pawel Bruce R, Devoto Marcella, Hakonarson Hakon, Rappaport Eric F, Irminger-Finger Irmgard, Maris John M. Common variation at BARD1 results in the expression of an oncogenic isoform that influences neuroblastoma susceptibility and oncogenicity. Cancer Research. 2012;72:2068–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeaut F, Ferrand S, Brugieres L, Hilbert M, Ribeiro A, Lacroix L, Benard J, Combaret V, Michon J, Valteau-Couanet D, Isidor B, Rialland X, Poiree M, Defachelles AS, Peuchmaur M, Schleiermacher G, Pierron G, Gauthier-Villars M, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Delattre O, Cancerologie Comite Neuroblastome of the Societe Francaise de ALK germline mutations in patients with neuroblastoma: a rare and weakly penetrant syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:291–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeaut F, Trochet D, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Ribeiro A, Deville A, Coz C, Michiels JF, Lyonnet S, Amiel J, Delattre O. Germline mutations of the paired-like homeobox 2B (PHOX2B) gene in neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2005;228:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzelfen Abdelilah, Alcantara Marion, Kora Hafid, Picquenot Jean-Michel, Bertrand Philippe, Cornic Marie, Mareschal Sylvain, Bohers Elodie, Maingonnat Catherine, Ruminy Philippe, Adriouch Sahil, Boyer Olivier, Dubois Sydney, Bastard Christian, Tilly Hervé, Latouche Jean-Baptiste, Jardin Fabrice. HACE1 is a putative tumor suppressor gene in B-cell lymphomagenesis and is down-regulated by both deletion and epigenetic alterations. Leukemia Research. 2016;45:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bown N, Lastowska M, Cotterill S, O’Neill S, Ellershaw C, Roberts P, Lewis I, Pearson AD, U. K. Cancer Cytogenetics Group, and U. K. Children’s Cancer Study Group the 17q gain in neuroblastoma predicts adverse clinical outcome. U.K. Cancer Cytogenetics Group and the U.K. Children’s Cancer Study Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:14–9. doi: 10.1002/1096-911X(20010101)36:1<14::AID-MPO1005>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresler SC, Weiser DA, Huwe PJ, Park JH, Krytska K, Ryles H, Laudenslager M, Rappaport EF, Wood AC, McGrady PW, Hogarty MD, London WB, Radhakrishnan R, Lemmon MA, Mosse YP. ALK mutations confer differential oncogenic activation and sensitivity to ALK inhibition therapy in neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:682–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresler SC, Wood AC, Haglund EA, Courtright J, Belcastro LT, Plegaria JS, Cole K, Toporovskaya Y, Zhao H, Carpenter EL, Christensen JG, Maris JM, Lemmon MA, Mosse YP. Differential inhibitor sensitivity of anaplastic lymphoma kinase variants found in neuroblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:108ra14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur G, Sawada T, Tsuchida Y, Voute P, Maris J, Tonini G. Genetics of Familial Neuroblastoma. In: Sawada T, Brodeur G, Tsuchida Y, Voute P, editors. Neuroblastoma. Elsevier Science B.V.; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, Varmus HE, Bishop JM. Amplification of N-myc in untreated human neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science. 1984;224:1121–4. doi: 10.1126/science.6719137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmon MF, Jeschke J, Zhang W, Dhir M, Siebenkas C, Herrera A, Tsai HC, O’Hagan HM, Pappou EP, Hooker CM, Fu T, Schuebel KE, Gabrielson E, Rahal P, Herman JG, Baylin SB, Ahuja N. Epigenetic silencing of neurofilament genes promotes an aggressive phenotype in breast cancer. Epigenetics. 2015;10:622–32. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1050173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso M, Devoto M, Hou C, Asgharzadeh S, Glessner JT, Attiyeh EF, Mosse YP, Kim C, Diskin SJ, Cole KA, Bosse K, Diamond M, Laudenslager M, Winter C, Bradfield JP, Scott RH, Jagannathan J, Garris M, McConville C, London WB, Seeger RC, Grant SF, Li H, Rahman N, Rappaport E, Hakonarson H, Maris JM. Common variations in BARD1 influence susceptibility to high-risk neuroblastoma. Nat Genet. 2009;41:718–23. doi: 10.1038/ng.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso Mario, Diskin Sharon, Cimmino Flora, Acierno Giovanni, Totaro Francesca, Petrosino Giuseppe, Pezone Lucia, Diamond Maura, McDaniel Lee, Hakonarson Hakon, Iolascon Achille, Devoto Marcella, Maris John M. Common genetic variants in NEFL influence gene expression and Neuroblastoma risk. Cancer Research. 2014;74:6913–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso Mario, Diskin Sharon J, Totaro Francesca, Longo Luca, de Mariano Marilena, Russo Roberta, Cimmino Flora, Hakonarson Hakon, Tonini Gian Paolo, Devoto Marcella, Maris John M, Iolascon Achille. Replication of GWAS-identified neuroblastoma risk loci strengthens the role of BARD1 and affirms the cumulative effect of genetic variations on disease susceptibility. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:605–11. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso Mario, McDaniel Lee D, Cimmino Flora, Cirino Andrea, Formicola Daniela, Russell Mike R, Raman Pichai, Cole Kristina A, Diskin Sharon J. The functional variant rs34330 of CDKN1B is associated with risk of neuroblastoma. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, XX. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron H, van Sluis P, van Hoeve M, de Kraker J, Bras J, Slater R, Mannens M, Voute PA, Westerveld A, Versteeg R. Allelic loss of chromosome 1p36 in neuroblastoma is of preferential maternal origin and correlates with N-myc amplification. Nat Genet. 1993;4:187–90. doi: 10.1038/ng0693-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter EL, Haglund EA, Mace EM, Deng D, Martinez D, Wood AC, Chow AK, Weiser DA, Belcastro LT, Winter C, Bresler SC, Vigny M, Mazot P, Asgharzadeh S, Seeger RC, Zhao H, Guo R, Christensen JG, Orange JS, Pawel BR, Lemmon MA, Mosse YP. Antibody targeting of anaplastic lymphoma kinase induces cytotoxicity of human neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2012;31:4859–67. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalla Demian, Newton Kathryn, Cáceres Javier F. A Novel SR-Related Protein Is Required for the Second Step of Pre-mRNA Splicing. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25:2969–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.2969-2980.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand D, Yamazaki Y, Ruuth K, Schonherr C, Martinsson T, Kogner P, Attiyeh EF, Maris J, Morozova O, Marra MA, Ohira M, Nakagawara A, Sandstrom PE, Palmer RH, Hallberg B. Cell culture and Drosophila model systems define three classes of anaplastic lymphoma kinase mutations in neuroblastoma. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:373–82. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Xiao, Zhao Yan, Hou Cuiping, Glessner Joseph, McDaniel Lee, Diamond Maura A, Thomas Kelly, Li Jin, Wei Zhi, Liu Yichuan, Guo Yiran, Mentch Frank D, Qiu Haijun, Kim Cecilia, Evans Perry, Vaksman Zalman, Diskin Sharon J, Attiyeh Edward F, Sleiman Patrick, Maris John M, Hakonarson Hakon. Common variants in MMP20 at 11q22.2 predispose to 11q deletion and neuroblastoma risk. Nature Communications. 2017;8:569–69. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatten J, Voorhess ML. Familial neuroblastoma. Report of a kindred with multiple disorders, including neuroblastomas in four siblings. N Engl J Med. 1967;277:1230–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196712072772304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Takita J, Choi YL, Kato M, Ohira M, Sanada M, Wang L, Soda M, Kikuchi A, Igarashi T, Nakagawara A, Hayashi Y, Mano H, Ogawa S. Oncogenic mutations of ALK kinase in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:971–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Isabel M, Hengst Ludger, Slingerland Joyce M. The Cdk inhibitor p27 in human cancer: prognostic potential and relevance to anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:253–67. doi: 10.1038/nrc2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn SL, Pearson AD, London WB, Monclair T, Ambros PF, Brodeur GM, Faldum A, Hero B, Iehara T, Machin D, Mosseri V, Simon T, Garaventa A, Castel V, Matthay KK, Inrg Task Force The International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system: an INRG Task Force report. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:289–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole WH, Everson TC. Spontaneous regression of cancer: preliminary report. Ann Surg. 1956;144:366–83. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195609000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney R, Ranganathan S. Simultaneous Adrenocortical Carcinoma and Neuroblastoma in an Infant With a Novel Germline p53 Mutation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;37:215–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daugaard M, Nitsch R, Razaghi B, McDonald L, Jarrar A, Torrino S, Castillo-Lluva S, Rotblat B, Li L, Malliri A, Lemichez E, Mettouchi A, Berman JN, Penninger JM, Sorensen PH. Hace1 controls ROS generation of vertebrate Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase complexes. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mariano M, Gallesio R, Chierici M, Furlanello C, Conte M, Garaventa A, Croce M, Ferrini S, Tonini GP, Longo L. Identification of GALNT14 as a novel neuroblastoma predisposition gene. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26335–46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]