Abstract

Novel therapeutic intervention that aims to enhance the endogenous recovery potential of the brain during the subacute phase of stroke has produced promising results. The paradigm shift in treatment approaches presents new challenges to preclinical and clinical researchers alike, especially in the functional endpoints domain. Shortcomings of the “neuroprotection” era of stroke research are yet to be fully addressed. Proportional recovery observed in clinics, and potentially in animal models, requires a thorough reevaluation of the methods used to assess recovery. To this end, this review aims to give a detailed evaluation of functional outcome measures used in clinics and preclinical studies. Impairments observed in clinics and animal models will be discussed from a functional testing perspective. Approaches needed to bridge the gap between clinical and preclinical research, along with potential means to measure the moving target recovery, will be discussed. Concepts such as true recovery of function and compensation and methods that are suitable for distinguishing the two are examined. Often-neglected outcomes of stroke, such as emotional disturbances, are discussed to draw attention to the need for further research in this area.

Keywords: Behavior, functional outcome, recovery, proportional recovery rule, stroke

Introduction

Over the past three decades, research efforts in developing viable stroke therapies have focused on neuroprotective mechanisms. A plethora of studies utilizing the neuroprotective approach have produced very promising results in animal studies. Yet several hundreds of potential therapeutic agents that have been tried at Phase II or III clinical trials showed very little or no efficacy.1,2

The apparent failure in bench-to-bedside translation was recognized as early as 1999, and recommendations to improve preclinical research design and standards were published by The Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR).3 Almost 20 years after the publication of numerous guidelines,4,5 literature indicates that the STAIR and STEPS initiatives have made significant contributions in increasing the quality of research in the field.6 While certain crucial recommendations of these initiatives are yet to be adequately implemented,7 the scientific rigor in stroke studies has been ameliorated drastically.6 Despite improvements, preclinical research is still affected by quality issues, including publication bias, false positives, lack of randomization and blinding, suboptimal sample size and inadequate long-term functional assessments.8

The failures in translation were not due solely to shortcomings in preclinical research. In fact, several clinical studies were undertaken with no or inadequate preclinical data,9 and in many cases the amount of evidence supporting the efficacy of the selected drug was not greater than that of other experimental interventions.10 It has also been proposed that some clinical trial results may be false negatives8 and many clinical trial designs may be suboptimal.11,12 Accordingly, STAIR has published guidelines to improve numerous aspects of clinical trials, including, but not limited to, patient selection criteria, pharmacokinetic evaluation, characterization of the dose response, and functional outcome assessments.13

As our understanding of the extent and physiology of recovery has improved, research focus has shifted to enhancing the endogenous recovery potential of the brain.14 It is now well established that a substantial amount of functional recovery occurs after stroke due to plastic remodeling.15 Recent studies employing neurorestorative therapies have primarily relied upon potentiating plasticity-related processes such as angiogenesis, neurogenesis, oligondendrogenesis and white matter remodeling.16 Various intervention modalities, including cell-based and pharmacological therapies, brain stimulation, and environmental enrichment,16–18 have produced very promising results in animal models and small clinical trials,19 thereby rejuvenating stroke research. Moreover, combination therapies – such as treatment with potential neuroprotective agents in conjunction with successful recanalization – may lead to a renaissance of neuroprotective and other experimental therapies that have previously been deemed unsuccessful when used alone in clinical trials.20

While the shortcomings of the “neuroprotection era” are yet to be fully addressed, the ongoing shift in research efforts towards enhancing recovery presents new challenges to preclinical and clinical researchers alike. The scientific community has already acknowledged the need to take action and a set of recommendations from Stem cell Therapeutics as an Emerging Paradigm for Stroke (STEPS) initiative and Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable (SRRR) have been published.21–23 Both STEPS and SRRR recommendations underlined the need to improve sensory motor evaluations and provided directions.24

To expand upon STEPS and SRRR recommendations, this review aims to give a detailed evaluation of functional outcome measures used in clinics and preclinical studies. Post stroke impairments and the timeline of recovery in human patients and preclinical models will be discussed from a functional testing perspective. Often-neglected outcomes of stroke – emotional disturbances, particularly post-stroke depression and anxiety – are discussed in a separate section. “Proportional functional recovery” is a critical observation in stroke patients, whereby the majority of patients recover about 70% of maximum possible improvement. We will question whether proportional recovery is present in animal models and what steps should be taken to ensure accordance between clinical and preclinical observations. Finally, the distinction between real recovery and compensation will be discussed, along with their effects on functional endpoint selection.

Post-stroke impairments

Impairments in stroke patients

Human stroke is highly variable and outcomes depend on location of ischemia, severity, duration, age, gender and comorbid conditions. Typically, a single infarction causes impairments in numerous domains of neurological functioning. Stroke patients display a myriad of impairments that include sensorimotor, emotional, and cognitive deficits.25 More than 50% of stroke survivors are left with physical disabilities.26,27 Notable motor impairments include loss of control of the face, arm, or leg of one side of the body and affects approximately 80% of stroke patients.27 Muscle weakness is a cardinal feature of stroke that affects balance, posture and movement.28 Loss of somatosensation is present in one in two people after stroke and may manifest as difficulty in sensing touch, pressure, and temperature, perceiving limb position and recognition of objects by touch,29 as well as altered or reduced pain sensation.30 Upper limb motor impairment, seen in 77% of stroke patients, is commonly experienced in conjunction with somatosensory impairments.31 Cognitive decline is frequent in stroke patients and particularly affects learning32 memory, attention, concentration, and alertness.27 Speech impairments are also common, with up to 30% of patients exhibiting aphasia and dysarthria.33

Impairments observed in preclinical models

To mimic the heterogeneity of human stroke, numerous animal models of focal ischemia have been developed (see Fluri et al.34 for a review). The deficits observed depend on the model used, intensity of ischemia (i.e. time and extent of occlusion) and the affected regions. Among experimental models, MCAo via the intraluminal filament method has been the most widely used method (∼47%) and produces the largest lesions (on average ∼32% of the hemisphere).35 Post-MCAo animals are lethargic with paresis on one side and display mild to severe circling behavior towards ipsilesional side. Animals lose a significant amount of body weight as the lesion develops; the extent of body weight loss is correlated with the lesion size and reaches maximum by days 3 to 5. The initial circling and apparent paresis resolve rapidly and animals begin gaining weight by day 5, gradually reaching baseline body weight.

MCAo induces postural reflex anomalies,36 sensory deficits in proprioception,37 coordination problems,38 muscle weakness, and reduced endurance39,40 and leads to impairments in gross motor function,41 walking,42 gait39,43 and posture.44,45 Fine motor function deficits39,40 on hind46,47 and front limbs,48 along with deficits in skilled reaching49 are frequently observed. Tactile sensation is also impaired.50,51 Stroked animals perform poorly in learning and memory tasks,52,53 as MCAo impairs episodic and spatial memory,54 working memory,55 procedural learning,56 contextual fear learning57 and strategy switching.58 Abnormalities in ultrasonic vocalizations59,60 used in various social interactions are also observed.61 Targeted stroke models such as endothelin-1 (ET-1) injection or photothrombosis can also induce similar impairments in a less diverse and isolated fashion.62,63 Studies using stereotactic injection of the potent vasoconstrictor ET-1 to produce focal infarctions in either or both the forelimb motor cortex (homologous to the human primary motor cortex) and dorsolateral striatum report persistent reproducible deficits in limb use, skilled reaching, grasping and fore and hind limb coordination.34 Photothrombotic occlusions in the motor cortex also produce similar lesions and impairments.64 Distal MCAo models primarily affect the whisker/vibrissal cortex and cause somatosensory deficits.65 Similar lesions are rare in clinical populations.66 Microembolic stroke models lead to distributed lesions, which represents a minority of stroke cases in humans, and induces deficits in attention and memory.67

Aligning preclinical lesion characteristics and impairments with clinical populations

Animal models can replicate practically all significant functional deficits of human strokes. In rodents, moderate to severe MCAo induces almost all of the impairments observed in stroke patients.39 An ideal model, however, should not only mimic the clinical impairments but ensure that behavioral deficits and lesion characteristics simultaneously match those of stroke patients. Due to the heterogeneity in lesions and relevant impairments in stroke patients, there is no “silver bullet” model. Preclinical researchers should be well-versed about the lesion characteristics seen in clinical studies and select or adjust their stroke models accordingly.

In this sense, there are discrepancies between a significant portion of clinical and preclinical studies. Widely used severe MCAo models (>60 min, permanent) typically lead to large malignant infarctions that cause arterial compression, progressive edema and infarct expansion. In comparison, most human stroke lesions are small in size, encompassing 4.5% to 14% of the ipsilateral hemisphere. Only 10% of human strokes are malignant infarctions (lesion size >39% of hemisphere).68 Such patients have high mortality (∼80%) and respond very poorly to therapy.69 As a result, they are rarely included in clinical studies. In addition, a significant portion of clinical rehabilitation and long-term recovery studies select patients with mild to moderate hemiparesis.70,71 Edwardson et al. have compared preclinical studies of upper limb recovery to patients from the Interdisciplinary Comprehensive Arm Rehabilitation Evaluation (ICARE) study. Their findings indicate that within the patient population, less than 1% had lesions resembling surface vessel occlusion or severe MCAo models used in preclinical studies evaluating limb recovery. Only 16% of patients had lesions similar to cortical photocoagulation and endothelin-1 injection models. Capsular hematoma and focal ischemia models leading to white matter lesions were more representative.72 It should be noted that these findings do not argue against the usefulness of MCAo model, but rather underline a mismatch between the preclinical and clinical studies of forelimb recovery. Indeed, authors state that “Short occlusion times for temporary MCAo may best match the relative lesion volumes from the ICARE sample”.72 Lesion sizes in widely used ET-1 models are also small and representative of clinical populations. Recent studies of forelimb recovery in rodents using the ET-1 model reported lesion sizes comparable to clinical populations.73 Regardless, there is an apparent gap in preclinical literature regarding pure white matter stroke studies and further studies are warranted.

Animal models of stroke have been met with criticism and assertions that there are serious differences between human and animal brains and that preclinical models do not mimic clinical conditions. However, with proper model selection, lesion characteristics and post-stroke deficits observed in human patients can be mimicked with utmost fidelity for long-term recovery studies. Preclinical researchers should be meticulous in terms of matching lesion characteristics and functional deficits to clinical patient populations. This can only be achieved by detailed reporting of lesion and impairment characteristics in clinical trial populations. Unfortunately, the broad inclusion criteria and insufficient patient stratification in earlier clinical trials of neuroprotection, which has been criticized as a factor contributing to translational failures, have stagnated the field in this regard as well.

Tools used for functional assessments

Clinical assessments

Historically, mortality and event recurrence have been used in stroke clinical trials. Since these clinical endpoints do not reflect the full spectrum of the disabling conditions of stroke, assessment of functional ability has been adopted.74 The “World Health Organization International Classification of Function” (ICF) characterizes function in terms of body functions, activity and participation. Various scales are used to evaluate the above mentioned levels of functional outcomes in stroke trials as primary or as secondary endpoints.75 There is no consensus and considerable heterogeneity in the functional outcome measures with more than 47 different scales used in clinical trials by 2009.75 In addition, statistical analysis methods were not uniform when identical scales were used.76 Nevertheless, a few of these scales have been widely used in clinical trials.

The Barthel Index

The Barthel Index (BI) was developed to measure independence and is used to score improvement in rehabilitation and assist patient discharge. It is a 10-item scale that measures self-care and mobility-related basic activities of daily living such as feeding, bathing, dressing. With its ease of use, familiarity among clinicians and satisfactory construct and face validity,77,78 it has been the most frequently used scale in acute clinical trials of stroke until 1998.79 The BI is scored via observation and interviewing of the patient by a trained individual using the items on the scale. The reliability and responsiveness of the scale are reasonable. However, the BI suffers from a number of shortcomings including “Floor” and “Ceiling” effects. Importantly, it does not address key aspects of independence such as vision, cognition and pain.80

The modified Rankin scale

Adapted from the original Rankin scale from 1957, the modified Rankin scale (mRS) evaluates recovery from stroke and functional independence. The mRS is a six-point scale in which 0 indicates no deficit, 4 indicates moderately severe disability and need for help in performing daily activities, 5 indicates severe disability and 6 marks death. Like the BI, the mRS is also scored via observation and interviewing of the patient by a trained individual using the items on the scale. However, compared to the BI, the mRS offers rapid and easy evaluation in clinical practice and is a better tool for distinguishing between changes in mild to moderated disability. Consequently, the mRS has replaced the BI as the primary functional outcome measure in clinical trials.75 The scale offers excellent reliability and validity. However, due to the basic 6-point assessment, its overall responsiveness (sensitivity to change) is poor.81

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) has been developed as an impairment scale utilized in acute stroke practices and clinical trials.82 The NIHSS is a 15-item scale that aims to standardize and quantify a basic neurological examination. Through observation and interaction with the patient, the NIHSS assesses the following domains: level of consciousness, eye movements, visual field integrity, facial movements, leg and arm muscle strength, sensation, coordination, speech, language and neglect. The test is simple to perform and takes approximately 6 min. Impairments are scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 2, 0 to 3, or 0 to 4. The sum total of the item scores ranges from 0 to 42, and scores above 21 are generally considered as severe.83 The NIHSS offers excellent reliability and adequate validity, but also suffers from several weaknesses: it does not include a detailed assessment of cranial nerves, leading to relatively lower scores in patients with cerebellar or brainstem lesions.80 Its validity in non-dominant hemisphere strokes has also been questioned,84 and a ceiling effect was observed at six months in 20% of patients.85

The Fugl-Meyer assessment

Often considered to be the most comprehensive quantitative measure of stroke, the Fugl-Meyer assessment (FMA) was developed as the first disease-specific impairment index for the assessment of recovery in hemiplegic patients.86 The FMA scale is a 226-point scale that is divided into five categories: motor function, sensory function, balance, range of motion in joints, and joint pain. Each of these categories is scored on a 3-point ordinal scale (0 = unable to perform, 1 = partially performs, 2 = fully performs). The motor domain measures movement, coordination and reflex actions at several joints and is scored from 0 to 100 points. The other categories also follow a similar point system, and the entire assessment takes about 30 min to perform.87 Despite its relative complexity, the FMA is widely used in rehabilitation-related clinical studies and increasingly used in others. A current search in the clinical trials database of NIH (clinicaltrials.gov) shows 245 active clinical trials are utilizing Fugl-Meyer as a primary or secondary outcome measure. The FMA displays excellent face, predictive,88 content89 and construct90 validity both for acute and chronic strokes. In chronic stroke, its responsiveness is moderate to large.91 Shortcomings of the FMA include a ceiling effect with the sensation score92 and a floor effect in the modified balance score93 and hand and lower extremity items.87

Modality specific functional tests

In addition to functional outcome scales, a number of functional tests validated for quantifying sensory-motor impairments are used in clinical settings (Table 1). These modality specific tests are designed to focus on and evaluate distinct impairments, offer higher responsiveness (sensitivity) and are better tools for assessing functional gains. Despite current wide use in clinical trials of neurorehabilitation, they have not been utilized in neuroprotective trials.

Table 1.

Clinical tests of sensorimotor function.

| Test | Method | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Box and block test | Patient is asked to move as many blocks as possible from one side of the box to the other using affected and unaffected hand in one minute. | Upper extremity motor function, coordination and dexterity. |

| Nine hole peg | Patients are asked to place nine pegs into nine holes and remove them using effected and unaffected hands separately. Time to completion is scored. | Upper extremity coordination, fine motor skills |

| Hand dynamometry | Patients squeeze a hand held dynamometer that measures grip strength with effected and unaffected hands. | Hand grip strength |

| Timed up and go test | Patient sitting in a chair is asked to get up and walk a distance of 3 m, turn around, walk back to the chair and sit down. Time to completion is scored. | Mobility, balance, walking ability, fall risk. |

| Gait velocity test | Patient is asked to walk a 10 m distance twice. Middle 6 m is timed. | Gait velocity, walking ability, ambulatory status |

| Action research arm test | Consists of four subtests: grasp, grip, pinch, and gross arm movement. Patients are asked to perform grasping, gripping and pinching tasks with varying difficulty. For gross arm subset patient is asked to touch the back and top of their head and their mouth. Performance is rated on 4 point scale for both hands. | Dexterity, coordination, fine motor skills of the hand, activities of daily living |

| Wolf motor function test | Consists of 17 upper extremity tasks including gross motion (i.e. lifting arm to the table), dexterity (fold towel, flipping cards), pronation/supination (turn key in a lock) and grip strength (measured via a dynamometer). | Upper extremity motor ability |

| The trunk control test | It is a 4 item test battery. For first 2 items, patients lying in supine position on the bench are asked to roll to the impaired and non-impaired sides. Third item requires the patient to sit on the bench without any support from arms for 30 s. Fourth item requires the patient to sit up from a lying position. Performance is scored by the tester. | Motor performance of the trunk |

| Pressure pain threshold | Using an algometer increasing pressure is applied to common muscle tender points (typically trapezius and brachioradialis). Compression is stopped when the patient feels pain or discomfort. | Muscle pain and allodynia in post stroke pain syndromes |

| Erasmus modified Nottingham sensory assessment | Patients are tested for tactile sensation (light touch, pressure, pinprick), sharp blunt discrimination and proprioception on various body parts. Scoring is performed by the tester in regards to the sensation being normal, impaired or absent. | Somatosensory impairment |

Preclinical assessments

Preclinical assessments are diverse, ranging from basic reflex tests to sophisticated kinematic analyses (see Table 2). One of the most basic tools for impairment evaluation is neurological assessment scales that resemble clinical ones. The modified neurological severity score (mNSS) is a frequently used 18-point neuroscore that assesses impairment using motor, sensory, balance and reflex tests.94 This test is fairly sensitive in distinguishing the effects of stroke and treatment at early time points, but it rapidly loses its utility within weeks. Due to the limited sensitivity of neuroscores, a large number of specialized behavioral tests have been established. Various tests can evaluate activities of “daily living,” such as nest building, burrowing and hoarding in rodents.95 Such tests resemble “independence” measures used for human patients and appear useful in preclinical studies,96 but are rarely used. Gross measures for activity and locomotion such as the open field test, which typically scores the distance covered by the animal, are useful in evaluating early lethargy; however, their long-term utility in detecting recovery is unclear.40 Rotarod is a frequently used test for motor function, endurance and balance. The latency to fall from an accelerating rotating rod is used in evaluating stroke outcomes at early time points, but long-term sensitivity varies depending on the setup, testing and training schedule.39,42 Locomotion assessments using gait analysis39,43 or variations of foot fault tests (scoring mistakes or slips during walking on rungs or ladders) have proven useful at acute to chronic post stroke stages.97,98 Tasks evaluating hand preference39 and skilled reaching are quite sensitive and clinically relevant99,100 (see Balkaya et al.44 for a detailed review).

Table 2.

Behavioral tests used in rodent models of focal ischemia.

| Test | Assessment of | Sensitivity perioda | Clinical relevance | Advantages and disadvantages | Discriminates compensation | Most useful application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mNSS94,179 | Sensory-motor, reflexes | <3 weeks | High Resembles clinical impairment evaluation scales | Easy to perform and analyze. Low sensitivity | NO | Triage, Confirmation of stroke deficit, Aligning preclinical and clinical endpoints of impairment |

| Rotarod39,44 | Motor coordination, locomotion, balance and endurance | >4 weeks (depending on protocol) in mice <3 weeks in rats | Medium Gross evaluation of walking and locomotion | Easy to perform and analyze, widely used High variability in sensitivity depending on the setup and protocol, Compensation, repeated testing exerts rehabilitation like effect reducing sensitive time window | NO | Triage, Mid to long-term investigation of sensory-motor deficits |

| Rotating beam test 180,181 | Motor coordination, locomotion, balance | <4 weeks (depending on protocol) in mice | Medium Gross evaluation of walking and locomotion | Easy to perform and analyze, High variability in sensitivity depending on the setup and protocol, Compensation, repeated testing exerts rehabilitation like effect reducing sensitive time window | NO | Early to midterm investigation of sensory-motor deficits |

| Pole Test39,44 | Grip strength and motor coordination | >4 weeks | Medium Gross evaluation of coordination and muscle strength | Low cost setup, easy to perform and analyze. Potentially hazardous for the animal at early time points. Repeated testing exerts rehabilitation like effect reducing sensitive time window | NO | Long-term investigation of sensory-motor deficits |

| Ladder Rung Test 182,183 | Locomotion, motor coordination | >4 weeks | Medium Gross evaluation of walking and locomotion | Simple low-cost setup Labor intensive scoring | NO | Long-term investigation of sensory-motor deficits |

| Wire hanging39 | Fore limb muscle strength and endurance | <2 weeks | High Upper extremity strength, paresis, flaccidity | Simple low-cost setup Hard to perform in highly active mouse strains | NO | Evaluation of early hemiparesis |

| Adhesive label39,50,65 | Forelimb sensory function | >6 weeks | High Sensory loss on ipsilateral hand | Simple, low cost setup Extensive training required, labor intensive scoring can vary among raters. | NO | Long-term investigation of sensory and motor deficits |

| Von frey test184,185 | Mechanical allodynia | >3 weeks in mice Time window for rats undetermined. | High Post-stroke central pain, Allodynia | Only available test for mechanical allodynia Time consuming, should be conducted by experienced testers. | NO | Long-term investigation of sensory deficit |

| Cylinder test39,183 | Forelimb use | >3 weeks (in lesions involving cortex) | Medium Reliance on non-impaired arm | Simple, low cost setup Labor intensive | NO | Long-term evaluation of non-impaired arm use |

| Skilled (pellet) Reaching 146 | Skilled forelimb use and grasping | <3 weeks in mice >4 weeks in rats | High Upper extremity, fine hand and digit control | Compensation detection possible with modifications. Extensive training, labor intensive, food deprivation. Repeated testing exerts rehabilitation like effect reducing sensitive time window | YES (in combination with kinematic analyses) | Detailed, long-term investigation of sensory-motor deficits |

| Corner test39,186 | Rotational asymmetries | >4 weeks | Low Rotational and turning preference measures are not used in clinical functional evaluations. | Simple, low cost setup, easy to perform Animal habituation and reduced compliance with repeated testing | NO | Confirmation of stroke deficit, long-term evaluation of pervasive asymmetries |

| Nest building95,96 | Overall health and daily activity | >3 weeks No data in rats | High Independence and ability to perform daily activities. | Simple, low cost, easy to perform, performed in home cage, spontaneous Single housing is a severe stressor effecting stroke mortality and post stroke psychological deficits | NO | Aligning preclinical and clinical endpoints related to independence |

| Grip strength test184 | Forelimb grip strength | <2 weeks for mice Rat studies report counterintuitive and conflicting findings. | High Muscle weakness and paresis of the arm and hand | Simple and quick to perform Inter trial and inter-tester reliability is low. Influenced by tester and the animals “participation”. Can produce counterintuitive findings (higher strength after stroke) due to difficulty in initiating movement. | NO | Evaluation of early hemiparesis |

| Montoya’s staircase task187 | Skilled forelimb use and grasping | >6 weeks in mice >4 weeks in rats | High Upper extremity, fine hand and digit control | Testing of individual arms separately Extensive training, labor intensive, food deprivation | YES (in combination with kinematic analyses) | Detailed, long-term investigation of sensory-motor deficits |

| Automatic gait analysis (catwalk, DigiGait) 39,42 | Gait and Locomotion patterns | >8 weeks >4 weeks in rats | High Gait and walking abnormalities | High, long-term sensitivity, extensive quantitative data. Compensation detection possible Expensive setup, Hard to perform and analyze | YES (in certain cases) | Detailed, long-term investigation of gait anomalies |

| Kinematic analyses145,146 | Kinematic | >8 weeks | High Analysis of abnormal and compensatory movement kinematics | High, long-term sensitivity, extensive quantitative data. Compensation detection Expensive setup, Hard to perform and analyze | YES | Detailed, long-term investigation of compensatory strategies |

Heavily dependent on model and protocol, represents a conservative estimate derived from current publications

Functional recovery

Recovery in stroke patients

Patients surviving the initial high mortality phase of stroke experience some degree of spontaneous recovery within weeks. A significant portion of this recovery takes place within the first month and can continue up to six months post stroke.101 Voluntary movements are observed in hemiplegic patients within the first week to month after stroke.102 A significant amount of upper extremity motor recovery occurs in the first four weeks and reaches plateau levels at three months after stroke.103 Depending on stroke severity, dexterity is regained in 41% to 78% of patients within six weeks.104 However, spontaneous recovery is not homogeneous in terms of degree and rate for every type of neurological function.105 Fine motor skills, such as picking up objects between the fingers and thumb, that involve smaller movements performed via wrists, hands, feet, fingers and toes take longer to recover compared to gross motor skills, such as walking or jumping, that involve large muscles of torso, arms and legs. Accordingly, proximal upper extremity recovery takes longer than upper extremity recovery.106,107 Language deficits continue to improve years after stroke.108 Improvements in motor impertinence can be observed up to 12 months109 and urinary incontinence can resolve as late as five months after stroke onset.

A similar heterogeneity is also observed in the percentage of patients that show improvement. Near full recovery is observed in 25 to 50% of patients depending on the assessment method used.101 However, more conservative analyses reveal that only 15% of stroke survivors with initial paresis had complete recovery of both the upper and lower extremities. A majority of studies report no noteworthy improvement in approximately a quarter of patients.110,111 Interestingly, among the patients that experience recovery, the amount of improvement appears to be highly predictable within a given time frame.112

Proportional recovery

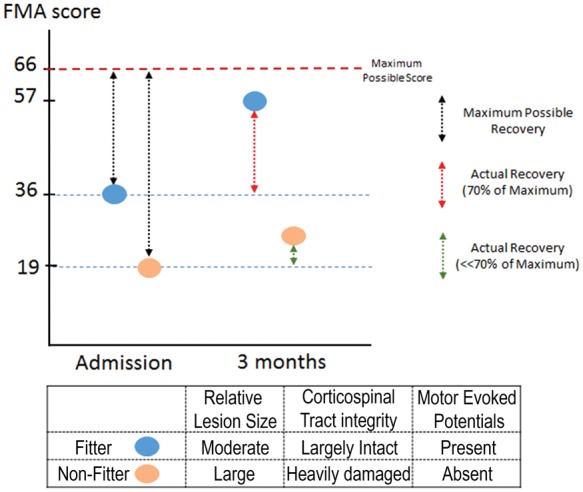

“The proportional recovery rule,” which is derived from clinical studies, asserts that a stroke patient should recover 70% of his/her potential function within three months. For example, a patient that scores 36 out of the maximum 66 in a Fugl-Meyer scale for upper extremity function will recover to ((66 − 36) × 0.7)) + 36 = 57 points.112 This rule has been validated for visuospatial neglect,113 aphasia,114 lower115 and upper limb116 motor recovery, as well as upper limb somatosensory processing recovery.117 Interestingly, while patients with mild to moderate hemiparesis recover in line with proportional recovery rule (fitters), patients with severe hemiparesis (FMA score <20) do not fit the rule (non-fitters) and show little recovery (see Figure 1).118 Absence of motor-evoked potentials119 and significant damage to the corticospinal tract tissue predicts the non-fitter status.119–121 Proportional recovery observations imply that recovery is mainly a spontaneous biological process driven by remaining healthy tissue and current rehabilitation regimens have no significant effect on functional gains.

Figure 1.

Fugl-Meyer scores of fitter and non-fitter patients at admission and three months. Fitter (blue) patient receives an FMA score of 36 at admission and from the maximum possible recovery score (black dashed line) of 30 recovers 70% (red dashed line) reaching a final score of 57. Non-fitter patient receives 19 at admission but does not recover according to the proportional recovery rule with minimal increase in FMA scores. Fitter and non-fitter patients differ in lesion size, corticospinal tract integrity and motor-evoked potential responses.

Recovery in preclinical models

In rodent models of stroke, the amount of spontaneous recovery observed is quite striking. Even in models that leads to large infarctions (e.g. proximal MCAo >30 min) encompassing subcortical and cortical regions, animals are capable of resuming normal daily activities rapidly. Within a week, lethargy, hunched posture, severe circling behavior and observable weakness on the contralateral side subside to a great extent. Within two weeks, stroked rodents regain their agility and appear almost undistinguishable from naïve animals.44 At this stage, only via specialized behavioral tests can sham and stroked animals be reliably distinguished. Within a month, a significant portion of sensory-motor behavioral tests employed in preclinical studies lose their sensitivity and only a few tests appear to be useful for longer periods of assessments (as outlined in Table 3). In the case of the widely used neuroscores, full recovery is already observed within three to four weeks in most stroke models.122 Only in very severe stroke models, such as 60 to 90 min or permanent MCAo, can the sensitivity window reach 12 weeks in certain expanded neuroscore scales.123 Regardless of the behavioral test used, spontaneous recovery appears to be more prominent after cortical lesions compared to subcortical or mixed lesions.124 Recovery occurs primarily during the first two weeks, and begins to reach plateau levels after four to five weeks.39,124,125

Table 3.

Preclinical behavioral test for depression and anxiety.

| Test | Assessment of | Method | Scoring method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forced Swim Test172,188,189 | Depression (Despair) | Animal is released into glass cylinder filled with water and allowed to swim freely for 5 to 6 min | Latency and total time spent immobile is scored |

| Tail Suspension Test190,191 | Depression (Despair) | Animal is suspended ∼50 cm above ground by taping tail to horizontal bar | Immobility time is scored |

| Learned helplessness192,193 | Depression (Despair) | Animals placed in to a “shuttle box” are exposed to repeated inescapable electrical foot shocks. In a subsequent session, animals are placed in a situation that they can actively avoid the foot shock. Depressed animals display reduced ability to escape. | Successful escapes from foot shocks |

| Sucrose Consumption Test172,194 | Depression (Anhedonia) | Rodents are presented with regular water and/or sucrose water in home cage | Sucrose consumed |

| Light Dark Box172,195 | Anxiety | Animal is placed in box divided into brightly illuminated and dark compartments and allowed to explore for 5 min | Time spent in each compartment is scored |

| Elevated Plus Maze171,196 | Anxiety | Animal is placed into elevated plus-shaped apparatus that has two open and two closed (walled) arms and allowed to explore for 5 min | Entry into and time spent in each arm is scored |

| Novelty-induced feeding suppression/ hypophagia172,197 | Anxiety | Animal is deprived of food for 12–24 h, then placed in a novel environment with food | Latency to begin feeding and amount of food consumed is scored |

The fact that a significant portion of the behavioral tests fail to distinguish between stroke and control within weeks suggests the possibility that the proportional recovery rule does not hold for animal models of stroke. Full recovery may simply be due to the limited sensitivity of the test. Indeed, a clear ceiling effect is apparent in tests such as the Rotarod. In high activity strains (e.g. C57), naive animals can easily achieve max score with brief training. Stroked animals with apparent postural anomalies also can achieve a max score in Rotarod, indicating a high susceptibility of the test to compensation.126 Alternatively, for some tests, the deficit in lab animals might have been compensated by the untapped redundant capacity. Lab animals live in a constant state of deprivation in impoverished, confined cages that offer little stimuli. Compared to their wild cousins, lab rodents display extremely low motor and cognitive skills. While selective inbreeding is certainly a main contributor, constant deprivation might be lowering baseline skills in lab animals, which in turn is rapidly compensated for post stroke. Experiments utilizing “enriched” environments are needed to test whether baseline scores would improve in behavioral tests and the percentage of animals showing full recovery would be altered accordingly.

A number of behavioral tests, however, retain their sensitivity over long periods of time. Despite rapid early recovery, animals reach plateau levels below baseline in tests of skilled reaching, forelimb sensory function and rotational preference up to months after stroke. Whether this sub-baseline improvement fits the proportional recovery rule remains to be determined. Animal experiments investigating proportional recovery in stroke models are extremely scarce. In a series of recent papers, Jeffers and Corbett have investigated proportional recovery and relevant biomarkers. Using a retrospective analysis of data from 593 rats, they have demonstrated that proportional recovery occurs in approximately 30% of rats (fitters) with a similar ratio (62–70%) seen in human patients.73 Approximately 62% of rats were non-fitters to the rule. Contrary to human observations, remaining animals declined over time. Infarct volume and initial impairment were predictive of recovery as well as fitter, non-fitter and decliner status.127

Aligning clinical and preclinical functional evaluation methods for long-term recovery studies

Putting rehabilitation studies aside, there is a striking discrepancy between clinical and preclinical functional endpoints. Composite scores (such as BI, mRS) that combine multiple aspects of neurological functioning suffer from numerous shortcomings, including floor and ceiling effects and low responsiveness. As a result, they have been criticized as a contributing factor to translational failures.66 The multimodal nature of stroke impairments and the fact that recovery occurs at different rates and to varying degrees further indicates that such scales are simply inadequate. Particularly, with the description of the proportional recovery rule in studies using the FMA, current trends in clinical studies favors its use as a primary functional outcome measure. Furthermore, it has been proposed that the proportional recovery rule should be utilized as a benchmark against which the efficacy of neurorestorative interventions can be tested.112 Nevertheless, the multimodal nature of stroke and the promise of impairment-specific drug development potential will inevitably increase the adoption of impairment-specific tests in clinical trials.128

How should preclinical research adjust to meet the upcoming changes in clinical evaluations? In terms of impairment-specific testing, the preclinical behavior arsenal is rich with sensitive tests. Clinically relevant deficits, such as gait abnormalities and forelimb, skilled reaching, and hind limb impairments should be the main focus of behavioral testing. Though it may sound controversial, we believe that “revisiting” and refining neuroscores to create a preclinical counterpart of the FMA is a worthwhile endeavor. Behavioral testing should be performed at baseline and post-stroke at multiple time points at least up to one month post-stroke. Post stroke behavioral data should be normalized to the baseline, and change against baseline, rather than the absolute numbers, should be used for statistics. An imminent need in the field is to determine whether proportional recovery is observed in animal models. Accordingly, preferred behavioral tests should ideally show chronic impairments that spontaneously recover and reach plateau levels below pre-stroke baseline and are compatible with the proportional recovery rule.66

True recovery versus compensation

The concept of recovery and the role of compensation in stroke often leads to confusion. In most cases, the term “recovery” is used to define the restitution of damaged tissue and clinical improvements simultaneously.129 This terminological ambiguity impairs the proper interpretation of clinical and preclinical results alike and impedes dissemination of knowledge among professionals from different disciplines. Recovery and compensation can occur at different levels. The proposed definitions by Levin et al. state that recovery at the neuronal level would represent “restoring function in neuronal tissue that was lost initially lost after injury” and compensation occurs when “neuronal tissue acquires a function that it did not have prior to injury.” In contrast, at the performance level, recovery is “restoring the ability to perform a movement in the same manner as it was performed before injury” and compensation is “performing an old movement in a new manner”.129

Clinical findings

A considerable portion of the functional recovery observed in stroke patients is a result of compensatory behavioral strategies. It has been documented that more than half of the patients with severe upper extremity paresis achieve some degree of recovery only through compensation.130 Similarly, gains in locomotor function are achieved through a combination of recovery and compensatory behaviors.131 Compensation also accounts for a significant portion of rehabilitative training-induced functional improvements.132 Interestingly, compensatory strategies at the cognitive level are also present and utilized by patients to make up for the lost capacity.133,134

Muscle weakness, reduced muscle activation and impaired muscle co-activation in stroke patients disrupts movement coordination.135 As a result, coupling of elbow and shoulder movements is disturbed, and wrist stability, grasp control and grasp release are impaired, leading to decreased hand dexterity.136 Thus, stroke patients rely on the non-paretic hand when executing unimanual tasks. During skilled reaching with the paretic hand, the cumulative effects of these impairments are observed as less direct trajectories, with slower and more variable movements.137,138 To compensate for instability, stroke patients fix hand and elbow positions and use trunk and scapula movements to aim for the target object.136

Clinical scales and tests measure functional improvement by assessments of independence or task accomplishment with little regard as to how the task is performed. They are therefore unable to distinguish compensation.129 Novel methods of gait analysis139,140 and kinematic analysis of upper141,142 and lower extremity131,143 enable precise identification of compensatory action patterns. However, these methods generally require expensive and sophisticated equipment, limiting their use in clinical studies.

Preclinical findings

Animals and humans display significant homologies in skilled reaching and grasping movement patterns. Post-stroke compensatory strategies employed are quite similar in humans and animals as well. Rodents, similar to human patients, rely on the unimpaired limb when performing unimanual tasks.144 When paretic arm is used, rodents execute slower, aberrant movements with high variability.145,146 Compensatory movements of the trunk and head are used to control paw position and bring the head to the paw.136

Behavioral evaluations in a great majority of preclinical studies evaluate recovery by utilizing gross latency scores or task completion success, making a distinction between recovery and compensation impossible. Nevertheless, kinematic analysis of locomotion and skilled reaching behavior in preclinical stroke models is feasible. Such methods not only enhance long-term sensitive analysis of function but enable the characterization of compensatory patterns, even in mild stroke models, both qualitatively and quantitatively.126,147 For example, utilizing a model of small phototrombotic cortical lesion, Lai et al.146 reported persistent (up to 30 days) kinematic modifications in a skilled reaching task. A very important finding of the study was that when reaching success is taken as the endpoint, there was no statistical difference between sham and stroke animals by week 2. In a similar study, the beneficial effects of somatic cell therapy were demonstrated in a MCAo model in rats. While both showed some degree of recovery, improvements in control animals were a result of compensatory adjustments. Treated groups had improved more and “kinematics more closely resembled pre-stroke movement patterns”.145 In a mouse model of MCAo, Qin et al. demonstrated enhanced motor recovery in animals carrying val66met polymorphism in the BDNF gene. Gait analysis of locomotion patterns revealed that enhanced motor “recovery” was a result of compensation in the ipsilateral hind limb.42 Such examples demonstrate the power of automated gait and kinematic analyses in distinguishing true functional recovery and compensation.

Aiming for the optimal recovery

Improving functional independence of stroke patients is a primary goal of clinical practice. To this end, it has been argued that compensatory behaviors leading to altered movement patterns should be considered adaptive as long as there is functional improvement.148 In addition, in rehabilitation settings, compensatory behavior in patients with severe disabilities is encouraged and reinforced. However, in certain conditions, compensatory behavior is maladaptive and leads to distorted joint positions.149 Moreover, maladaptive compensation and learned misuse may hinder long-term recovery of healthy movement patters. Further clinical and preclinical research is needed to identify optimal time windows and means to improve true recovery over compensation. Gait and kinematic analyses of locomotion and skilled reaching offer long-term sensitivity and enable detection of compensatory patterns. While dedicated setups for such analyses exist, kinematic analyses can also be achieved by low cost means and should gain further adoption.

Neuroprotective interventions with recanalisation

Intravenous thrombolysis via tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and endovascular thrombectomy are two potent treatment options for acute stroke that can significantly reduce stroke damage though recanalization (reopening of the occluded principal artery) and reperfusion (microvascular blood flow restoration). In clinical trials of neuroprotection, documentation of successful arterial canalization as an enrollment criteria has not been obligatory.150 Typically, 10% of stroke patients are considered suitable for recanalization therapies.151 Considering that only one-third of MCA occlusions and 10% of distal ICA occlusions recanalize,152 certain comorbid conditions such as diabetes and carotid artery disease further reduce canalization rates,153 and 25% percent of recanalizations do not lead to reperfusion,154 it is safe to conclude that, particularly in earlier clinical trials, the number of patients that achieved successful reperfusion is quite limited. The low number of patients with reperfusion in clinical studies puts into question whether drugs reached adequate concentration in potentially salvageable tissue and indicates a drastic disparity between clinical trials and preclinical studies, in which a majority of the neuroprotective agents were primarily tested in transient focal ischemia models with complete reperfusion. It is important to note that numerous neuroprotective agents that show significant efficacy in transient models fail to show any effect in preclinical studies employing permanent occlusions.155 As such, the differences between preclinical and clinical studies in reperfusion profiles are potentially a primary contributor to translational failures.

Earlier and wider access to tPA treatment, development of more potent thrombolytic agents and advances in endovascular treatment of acute stroke increased the success rate and number of patients receiving recanalization. This raises the possibility that when combined with successful recanalization, neuroprotective agents may exert their true potential observed in animal models and become a feasible treatment option.154,155 Particularly, intra-arterial delivery of putative neuroprotectants post-thrombectomy when and where they are most needed is a promising treatment strategy.

In this context, Savitz et al. proposed that preclinical research will need to address several lines of research questions: (1) Can a neuroprotectant extend the time window for thrombolysis or thrombectomy? (2) Does its efficacy differ with or without reperfusion? (3) Does the route of delivery alter its efficacy? (4) Does it ameliorate reperfusion injury? Sufficiently addressing such research questions will create considerable challenges in model selection, experimental design and especially behavioral evaluation.

It has to be expected that in such experimental studies, the effect size in any given behavioral evaluation would be considerably lower compared to a typical neuroprotection study. Researchers should utilize conservative effect size estimates while calculating their sample sizes, which will increase the number of animals required but significantly increase the sensitivity of their evaluations. Behavioral test selections should include separate tests for motor, sensory and cognitive function to screen for improvements in all of these domains. Kinematic analyses that offer superior responsiveness both at acute and chronic phases should be employed.

Post-stroke neuropsychiatric disturbances

Neuropsychiatric disturbances in stroke patients

Cerebrovascular lesions can lead to emotional disturbances including depression, anxiety, emotional incontinence, fatigue, mania, and anger proneness.156–158 Post-stroke depression (PSD) is the most frequent and debilitating mood disorder observed in stroke survivors and has profound effects on patient recovery and well-being. PSD increases mortality by up to 10 times, slows recovery and predicts worse functional and cognitive outcome.159 Depressed mood increases limitations on daily activity and rehabilitation efforts.160 In addition, depression after stroke increases hospitalization time and healthcare costs.161 Interestingly, depressive symptoms tend to increase in the chronic phase of recovery162,163 and persist for over three years in 29% of elderly patients.164 Taken together, PSD is a chronic, frequent and severe complication with significant negative effects on the patient and healthcare efforts.

In clinical settings, post stroke depression diagnosis and follow-up evaluations are performed using structured clinical interviews using depression scales. There are a number of scales validated for depression diagnosis and clinical studies vary in terms of the preferred method. Scales commonly used in stroke clinical trials include the Hamilton depression and anxiety scales, Beck depression index, patient health questionnaire-9, and Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale.165 Due to differences in study settings and criteria reported, PSD prevalence rates vary widely and range between 5% and 79%. A detailed examination of the literature indicates that the mean prevalence rate was 24.0% for major depression and 23.9% for minor depression after stroke.166 Two recent meta-analysis studies reported pooled prevalence rates of 29%167 and 31%168 at any time up to five years post stroke. The percentage of patients who had one or more depressive episodes within five years following stroke ranged from 39% to 52%.167 In addition, approximately 30% of stroke patients display anxiety, and a high percentage of these patients show comorbidity with PSD.

Neuropsychiatric disturbances in animal models of stroke

Studies modeling PSD and other mood disorders are scarce. While global ischemia models induce robust PSD and anxiety-like behaviors,169,170 findings have been inconsistent in focal ischemia models. Various reports describe the “spontaneous” evolution of anxious or depressive phenotypes after MCAo in rodents. An early study by Winter et al. has reported anxiety after left MCAo. Interestingly, no sign of anxiety was observed in animals with right MCAo.171 The same group reported anhedonia, depressive-like behavior and anxiety 13 weeks after left strokes with the right MCAo group exhibiting hyperactivity as the only behavioral alteration.172 Conversely, using the sucrose consumption test, an anhedonic phenotype in animals with right MCAo at two weeks after stroke was reported by Craft et al.173 In a rat model of permanent MCAo, Ifergane et al. have reported PSD-like phenotype in a wide battery of tests, including the two-way shuttle avoidance task. Importantly, using cluster analysis, they demonstrated that about 56% of stroked animals developed significant behavioral disruptions associated with PSD.174 Others have demonstrated depressive phenotypes in the forced swim test can be further exacerbated by chronic mild stress exposure, which was reported in animals with left MCAo.175 In line with that study, numerous groups have employed long-term stress exposure after stroke to ensure robust and replicable PSD phenotypes.176 Housing conditions also seem to affect PSD development. Animals with right MCAo that displayed reduced immobility in the forced swim test showed higher immobility as compared to controls when housed in isolation.177 Age can be a predicting factor for PSD. Buga et al.178 reported that MCAo leads to depressive behaviors only in aged rats.

PSD as a major focus of preclinical research

Despite growing interest in the debilitating consequences of PSD in the last two decades, PSD and its pathophysiology have been grossly understudied in stroke research. Clinical studies are narrow and animal models require further refinement. Our understanding of PSD pathophysiology is thus limited and complicated by conflicting findings from clinical and experimental studies. Importantly, PSD assessments are rarely included in clinical studies of long-term functional recovery. Given the reliability and ease of administering and depression scales, this represents a missed opportunity. We believe that PSD should be one of the primary targets of therapy in clinical and preclinical neurorestorative studies.

Closing remarks

Closing the gap between clinical and preclinical studies requires adjustments in study design on both sides. Early clinical studies have been heavily criticized for very broad inclusion criteria, lack of patient stratification and use of imprecise global outcome measures. Stroke symptoms are multimodal and there is considerable difference between different neurological functions in terms of degree and rate of recovery. As such, composite scales of global outcome measures are not able to offer enough sensitivity and do not address the broad spectrum of post-stroke impairments and their variations in recovery.128 Notably, motor-weighted composite scales are likely to miss improvements in neglect, aphasia, cognitive function and emotional disturbances. The clinical test arsenal has well-established modality-specific tests that have been validated and successfully used, particularly in rehabilitation studies. Clinical studies of neurorestorative interventions should employ such assessments – including cognitive and emotional – to align with preclinical studies and achieve greater sensitivity.

The preclinical behavior models can mimic all human functional deficits. There are, however, inconsistencies between the lesion and functional deficit characteristics between preclinical and clinical studies. Preclinical researchers should therefore try to match lesion and impairment characteristics of the clinical population. This requires detailed descriptions of the patient data from clinical studies. Behavioral tests utilized in preclinical models offer enough sensitivity for long-term analysis. Test selection should be done by taking the relevant clinical impairments into account, and testing should be performed repeatedly at least up to a month after stroke. Proportional recovery observation has far reaching implications on rehabilitation and recovery studies. Addressing whether proportional recovery is consistently present in animal models among various functional domains is of significant importance. In studies combining recanalization with neuroprotective treatments, utilizing conservative effect size estimates and having large experimental group sizes are of utmost importance for demonstrating potential individual and synergistic beneficial effects of these treatments. Finally, PSD affects a large number of stroke survivors, but the number of studies focusing on the pathophysiology of PSD is very limited. The stroke field can benefit greatly from studies focusing on establishing reliable animals models of PSD.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Endres M, Engelhardt B, Koistinaho J, et al. Improving outcome after stroke: overcoming the translational roadblock. Cerebrovasc Dis 2008; 25: 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Wang K. The fate of medications evaluated for ischemic stroke pharmacotherapy over the period 1995-2015. Acta Pharm Sin B 2016; 6: 522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albers GW, Anwer UE, et al. Stroke Therapy Academic Industry R. Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke 1999; 30: 2752–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu S, Zhen G, Meloni BP, et al. Rodent stroke model guidelines for preclinical stroke trials (1st edition). J Exp Stroke Transl Med 2009; 2: 2–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke 2009; 40: 2244–22450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramirez FD, Motazedian P, Jung RG, et al. Methodological rigor in preclinical cardiovascular studies: targets to enhance reproducibility and promote research translation. Circul Res 2017; 120: 1916–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas A, Detilleux J, Flecknell P, et al. Impact of stroke therapy academic industry roundtable (STAIR) guidelines on peri-anesthesia care for rat models of stroke: a meta-analysis comparing the years 2005 and 2015. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0170243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sena E, van der Worp HB, Howells D, et al. How can we improve the pre-clinical development of drugs for stroke? Trends Neurosci 2007; 30: 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn J, de Haan RJ, Vermeulen M, et al. Nimodipine in animal model experiments of focal cerebral ischemia: a systematic review. Stroke 2001; 32: 2433–2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Collins VE, Macleod MR, Donnan GA, et al. 1,026 experimental treatments in acute stroke. Ann Neurol 2006; 59: 467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lees KR. Neuroprotection is unlikely to be effective in humans using current trial designs: an opposing view. Stroke 2002; 33: 308–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lees KR, Hankey GJ, Hacke W. Design of future acute-stroke treatment trials. Lancet Neurol 2003; 2: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher M. Stroke Therapy Academic Industry R. Recommendations for advancing development of acute stroke therapies: stroke therapy academic industry roundtable 3. Stroke 2003; 34: 1539–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao L-R, Willing A. Enhancing endogenous capacity to repair a stroke-damaged brain: an evolving field for stroke research. Prog Neurobiol 2018; 163–164: 5–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy TH, Corbett D. Plasticity during stroke recovery: from synapse to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009; 10: 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Venkat P, Zacharek A, et al. Neurorestorative therapy for stroke. Front Hum Neurosci 2014; 8: 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer SC. An overview of therapies to promote repair of the brain after stroke. Head Neck 2011; 33(Suppl 1): S5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dabrowski A, Robinson TJ, Felling RJ. Promoting brain repair and regeneration after stroke: a plea for cell-based therapies. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019; 19: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azad TD, Veeravagu A, Steinberg GK. Neurorestoration after stroke. Neurosurg Focus 2016; 40: E2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savitz SI, Baron JC, Yenari MA, et al. Reconsidering neuroprotection in the reperfusion era. Stroke 2017; 48: 3413–3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wechsler L, Steindler D, Borlongan C, et al. Stem Cell Therapies as an Emerging Paradigm in Stroke (STEPS): bridging basic and clinical science for cellular and neurogenic factor therapy in treating stroke. Stroke 2009; 40: 510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savitz SI, Chopp M, Deans R, et al. Stem cell therapy as an emerging paradigm for stroke (STEPS) II. Stroke 2011; 42: 825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savitz SI, Cramer SC, Wechsler L, et al. Stem cells as an emerging paradigm in stroke 3: enhancing the development of clinical trials. Stroke 2014; 45: 634–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamandis T, Borlongan CV. One, two, three steps toward cell therapy for stroke. Stroke 2015; 46: 588–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renton T, Tibbles A, Topolovec-Vranic J. Neurofeedback as a form of cognitive rehabilitation therapy following stroke: a systematic review. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0177290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwakkel G, Kollen BJ, van der Grond J, et al. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke 2003; 34: 2181–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewer L, Horgan F, Hickey A, et al. Stroke rehabilitation: recent advances and future therapies. QJM 2013; 106: 11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arene N, Hidler J. Understanding motor impairment in the paretic lower limb after a stroke: a review of the literature. Topics Stroke Rehab 2009; 16: 346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carey LM, Matyas TA, Baum C. Effects of somatosensory impairment on participation after stroke. Am J Occup Ther 2018; 72: 7203205100p1–7203205100p10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klit H, Finnerup NB, Andersen G, et al. Central poststroke pain: a population-based study. Pain 2011; 152: 818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence ES, Coshall C, Dundas R, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of acute stroke impairments and disability in a multiethnic population. Stroke 2001; 32: 1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosser N, Heuschmann P, Wersching H, et al. Levodopa improves procedural motor learning in chronic stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2008; 89: 1633–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali M, Lyden P, Brady M, et al. Aphasia and dysarthria in acute stroke: recovery and functional outcome. Int J Stroke 2015; 10: 400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fluri F, Schuhmann MK, Kleinschnitz C. Animal models of ischemic stroke and their application in clinical research. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015; 9: 3445–3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Collins V, Donnan G, Macleod M, et al. Chapter 23 animal models of stroke versus clinical stroke: comparison of infarct size, cause, location, study design, and efficacy of experimental therapies. In: Animal Models Study Hum Dis. Academic Press, 2013, pp. 531–568.

- 36.Zhao W, Belayev L, Ginsberg MD. Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion by intraluminal suture: II. Neurological deficits, and pixel-based correlation of histopathology with local blood flow and glucose utilization. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1997; 17: 1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu JR, Jensen-Kondering UR, Zhou JJ, et al. Transient filament occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in rats: does the reperfusion method matter 24 hours after perfusion? BMC Neurosci 2012; 13: 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouet V, Freret T, Toutain J, et al. Sensorimotor and cognitive deficits after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the mouse. Exp Neurol 2007; 203: 555–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balkaya M, Krober J, Gertz K, et al. Characterization of long-term functional outcome in a murine model of mild brain ischemia. J Neurosci Meth 2013; 213: 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balkaya M, Endres M. Behavioral testing in mouse models of stroke. In: Dirnagl U (eds) rodent models of stroke. Neuromethods 2010; 47: 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yonemori F, Yamaguchi T, Yamada H, et al. Evaluation of a motor deficit after chronic focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998; 18: 1099–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin L, Jing D, Parauda S, et al. An adaptive role for BDNF Val66Met polymorphism in motor recovery in chronic stroke. J Neurosci 2014; 34: 2493–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parkkinen S, Ortega FJ, Kuptsova K, et al. Gait impairment in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke Res Treatment 2013; 2013: 410972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balkaya M, Krober JM, Rex A, et al. Assessing post-stroke behavior in mouse models of focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metabol 2013; 33: 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pertici V, Pin-Barre C, Felix MS, et al. A new method to assess weight-bearing distribution after central nervous system lesions in rats. Behav Brain Res 2014; 259: 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papadopoulos CM, Tsai SY, Guillen V, et al. Motor recovery and axonal plasticity with short-term amphetamine after stroke. Stroke 2009; 40: 294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stout JM, Knapp AN, Banz WJ, et al. Subcutaneous daidzein administration enhances recovery of skilled ladder rung walking performance following stroke in rats. Behav Brain Res 2013; 256: 428–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allred RP, Adkins DL, Woodlee MT, et al. The vermicelli handling test: a simple quantitative measure of dexterous forepaw function in rats. J Neurosci Meth 2008; 170: 229–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharkey J, Crawford JH, Butcher SP, et al. Tacrolimus (FK506) ameliorates skilled motor deficits produced by middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke 1996; 27: 2282–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freret T, Bouet V, Leconte C, et al. Behavioral deficits after distal focal cerebral ischemia in mice: usefulness of adhesive removal test. Behav Neurosci 2009; 123: 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takami K, Fujita-Hamabe W, Harada S, et al. Abeta and Adelta but not C-fibres are involved in stroke related pain and allodynia: an experimental study in mice. J Pharm Pharmacol 2011; 63: 452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hattori K, Lee H, Hurn PD, et al. Cognitive deficits after focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke 2000; 31: 1939–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeVries AC, Nelson RJ, Traystman RJ, et al. Cognitive and behavioral assessment in experimental stroke research: will it prove useful? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2001; 25: 325–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cuartero MI, de la Parra J, Perez-Ruiz A, et al. Abolition of aberrant neurogenesis ameliorates cognitive impairment after stroke in mice. J Clin Invest 2019; 129: 1536–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tao T, Zhao M, Yang W, et al. Neuroprotective effects of therapeutic hypercapnia on spatial memory and sensorimotor impairment via anti-apoptotic mechanisms after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Neurosci Lett 2014; 573: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linden J, Van de Beeck L, Plumier JC, et al. Procedural learning as a measure of functional impairment in a mouse model of ischemic stroke. Behav Brain Res 2016; 307: 35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chin Y, Kishi M, Sekino M, et al. Involvement of glial P2Y(1) receptors in cognitive deficit after focal cerebral stroke in a rodent model. J Neuroinflamm 2013; 10: 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Winter B, Bert B, Fink H, et al. Dysexecutive syndrome after mild cerebral ischemia? Mice learn normally but have deficits in strategy switching. Stroke 2004; 35: 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doran SJ, Trammel C, Benashaski SE, et al. Ultrasonic vocalization changes and FOXP2 expression after experimental stroke. Behav Brain Res 2015; 283: 154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan J, Palmateer J, Schallert T, et al. Novel humanized recombinant T cell receptor ligands protect the female brain after experimental stroke. Transl Stroke Res 2014; 5: 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Matsumoto YK, Okanoya K. Mice modulate ultrasonic calling bouts according to sociosexual context. R Soc Open Sci 2018; 5: 180378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adkins DL, Voorhies AC, Jones TA. Behavioral and neuroplastic effects of focal endothelin-1 induced sensorimotor cortex lesions. Neuroscience 2004; 128: 473–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porritt MJ, Andersson HC, Hou L, et al. Photothrombosis-induced infarction of the mouse cerebral cortex is not affected by the Nrf2-activator sulforaphane. PLoS One 2012; 7: e41090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okabe N, Himi N, Maruyama-Nakamura E, et al. Rehabilitative skilled forelimb training enhances axonal remodeling in the corticospinal pathway but not the brainstem-spinal pathways after photothrombotic stroke in the primary motor cortex. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0187413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bouet V, Boulouard M, Toutain J, et al. The adhesive removal test: a sensitive method to assess sensorimotor deficits in mice. Nat Protoc 2009; 4: 1560–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corbett D, Carmichael ST, Murphy TH, et al. Enhancing the alignment of the preclinical and clinical stroke recovery research pipeline: consensus-based core recommendations from the Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation Roundtable translational working group. Int J Stroke 2017; 12: 462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nemeth CL, Shurte MS, McTigue DM, et al. Microembolism infarcts lead to delayed changes in affective-like behaviors followed by spatial memory impairment. Behav Brain Res 2012; 234: 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carmichael ST. Rodent models of focal stroke: size, mechanism, and purpose. NeuroRx 2005; 2: 396–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hacke W, Schwab S, Horn M, et al. ‘Malignant’ middle cerebral artery territory infarction: clinical course and prognostic signs. Arch Neurol 1996; 53: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dromerick AW, Lang CE, Birkenmeier RL, et al. Very early constraint-induced movement during stroke rehabilitation (VECTORS): a single-center RCT. Neurology 2009; 73: 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winstein CJ, Wolf SL, Dromerick AW, et al. Effect of a task-oriented rehabilitation program on upper extremity recovery following motor stroke: the ICARE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315: 571–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Edwardson MA, Wang X, Liu B, et al. Stroke lesions in a large upper limb rehabilitation trial cohort rarely match lesions in common preclinical models. Neurorehab Neural Repair 2017; 31: 509–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jeffers MS, Karthikeyan S, Corbett D. Does stroke rehabilitation really matter? part a: proportional stroke recovery in the rat. Neurorehab Neural Repair 2018; 32: 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taylor-Rowan M, Wilson A, Dawson J, et al. Functional assessment for acute stroke trials: properties, analysis, and application. Front Neurol 2018; 9: 191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, et al. Functional outcome measures in contemporary stroke trials. Int J Stroke 2009; 4: 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bath PM, Gray LJ, Collier T, et al. Can we improve the statistical analysis of stroke trials? Statistical reanalysis of functional outcomes in stroke trials. Stroke 2007; 38: 1911–1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Gresham GE. The stroke rehabilitation outcome study – part I: general description. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1988; 69: 506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kessner SS, Bingel U, Thomalla G. Somatosensory deficits after stroke: a scoping review. Topics Stroke Rehab 2016; 23: 136–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sulter G, Steen C, De Keyser J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke 1999; 30: 1538–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dromerick AW, Edwards DF, Diringer MN. Sensitivity to changes in disability after stroke: a comparison of four scales useful in clinical trials. J Rehabil Res Dev 2003; 40: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brott T, Adams HP, Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989; 20: 864–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kwah LK, Diong J. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). J Physiother 2014; 60: 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martin-Schild S, Albright KC, Tanksley J, et al. Zero on the NIHSS does not equal the absence of stroke. Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57: 42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Feeny DH. Responsiveness of generic health-related quality of life measures in stroke. Qual Life Res 2005; 14: 207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, et al. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehab Med 1975; 7: 13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gladstone DJ, Danells CJ, Black SE. The fugl-meyer assessment of motor recovery after stroke: a critical review of its measurement properties. Neurorehab Neural Repair 2002; 16: 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Matchar D, et al. Measurement of motor recovery after stroke. Outcome assessment and sample size requirements. Stroke 1992; 23: 1084–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woodbury ML, Velozo CA, Richards LG, et al. Longitudinal stability of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment of the upper extremity. Arch Phys Med Rehab 2008; 89: 1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hsieh Y-W, Wu C-Y, Lin K-C, et al. Responsiveness and validity of three outcome measures of motor function after stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2009; 40: 1386–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wei X-J, Tong K-Y, Hu X-L. The responsiveness and correlation between Fugl-Meyer assessment, motor status scale, and the action research arm test in chronic stroke with upper-extremity rehabilitation robotic training. Int J Rehabil Res 2011; 34: 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lin J-H, Hsueh IP, Sheu C-F, et al. Psychometric properties of the sensory scale of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment in stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 2004; 18: 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mao H-F, Hsueh IP, Tang P-F, et al. Analysis and comparison of the psychometric properties of three balance measures for stroke patients. Stroke 2002; 33: 1022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen J, Sanberg PR, Li Y, et al. Intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood reduces behavioral deficits after stroke in rats. Stroke 2001; 32: 2682–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Deacon R. Assessing burrowing, nest construction, and hoarding in mice. J Visual Exp 2012, pp. e2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yuan D, Liu C, Wu J, et al. Nest-building activity as a reproducible and long-term stroke deficit test in a mouse model of stroke. Brain Behav 2018; 8: e00993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]