Abstract

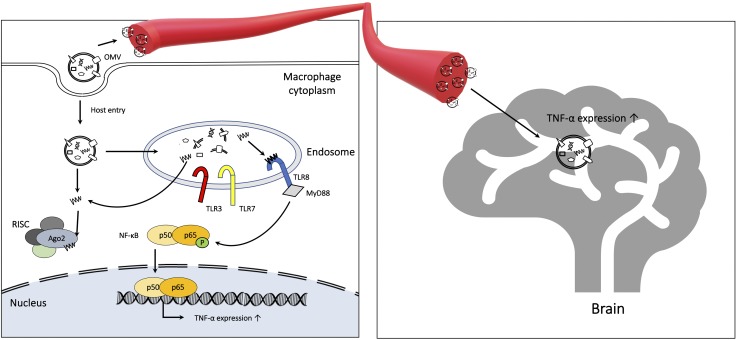

Among the main bacteria implicated in the pathology of periodontal disease, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) is well known for causing loss of periodontal attachment and systemic disease. Recent studies have suggested that secreted extracellular RNAs (exRNAs) from several bacteria may be important in periodontitis, although their role is unclear. Emerging evidence indicates that exRNAs circulate in nanosized bilayered and membranous extracellular vesicles (EVs) known as outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) in gram-negative bacteria. In this study, we analyzed the small RNA expression profiles in activated human macrophage-like cells (U937) infected with OMVs from Aa and investigated whether these cells can harbor exRNAs of bacterial origin that have been loaded into the host RNA-induced silencing complex, thus regulating host target transcripts. Our results provide evidence for the cytoplasmic delivery and activity of microbial EV-derived small exRNAs in host gene regulation. The production of TNF-α was promoted by exRNAs via the TLR-8 and NF-κB signaling pathways. Numerous studies have linked periodontal disease to neuroinflammatory diseases but without elucidating specific mechanisms for the connection. We show here that intracardiac injection of Aa OMVs in mice showed successful delivery to the brain after crossing the blood–brain barrier, the exRNA cargos increasing expression of TNF-α in the mouse brain. The current study indicates that host gene regulation by microRNAs originating from OMVs of the periodontal pathogen Aa is a novel mechanism for host gene regulation and that the transfer of OMV exRNAs to the brain may cause neuroinflammatory diseases like Alzheimer’s.—Han, E.-C., Choi, S.-Y., Lee, Y., Park, J.-W., Hong, S.-H., Lee, H.-J. Extracellular RNAs in periodontopathogenic outer membrane vesicles promote TNF-α production in human macrophages and cross the blood–brain barrier in mice.

Keywords: microRNA, periodontitis, small RNA, extracellular vesicle, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

Periodontitis, a complex disease that involves the host’s immune inflammatory response, is characterized by degradation of soft connective tissue and alveolar bone, ultimately resulting in tooth loss (1). More than 500 species of bacteria are associated with tissues in the human oral environment, and periodontitis is specifically associated with the presence of gram-negative bacteria such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa), Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia (2, 3). Inflammation during periodontitis is known to be characterized by the recruitment of leukocytes. Numerous factors induce leukocyte recruitment, including cytokines, lipid mediators, and other communication molecules (4), but the roles of other molecules, including RNA and DNA, are still unclear. Among the key bacteria implicated in the pathology of periodontal disease, the periodontopathogen Aa, a small, nonmotile, nonencapsulated, slow-growing, well-characterized pathogen, is known to be important in localized periodontitis and periodontal attachment loss (5, 6). Aa is also reported to cause systemic disease, including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis through the activation of proinflammatory cytokines (7), and rheumatoid arthritis caused by hypercitrullination (8).

Recently, there has been increasing interest in the possible interaction between periodontopathogens and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (9–11). An increase in antibodies against periodontal pathogens and TNF-α has been shown in patients with AD (12). More recently, a periodontal pathogen was identified in the brain tissue of patients with AD (13).

According to the classic understanding of microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis, miRNAs are first transcribed into primary miRNAs by RNA polymerase II and then processed into mature miRNAs that bind to the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which contains argonaute 2 (Ago2) (14, 15). Recent studies have identified small RNAs (sRNAs), including miRNA-sized sRNAs (msRNAs), in several bacteria (14, 15); however, their functions are unclear or have just begun to be studied. There is some evidence that miRNAs and sRNAs can circulate in nanosized (ranging from ∼20 to 250 nm in size), bilayered, and membranous extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are known as outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) in gram-negative bacteria (16, 17). The way in which these extracellular RNAs (exRNAs) are taken up and communicate with host cells is not fully understood (18). The EVs of bacteria or OMVs have functions such as the secretion of virulence factors or the transfer of macromolecules between bacterial cells (19). Working with colleagues, we recently found that small exRNAs in OMVs in pathogenic bacteria can be delivered into host cells and thereby modulate host immune responses (20–22), but it remains unclear whether these msRNAs have regulatory functions in the host cells by binding to Ago2 (14, 15). It has been hypothesized that bacterial OMVs may cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and affect AD pathology (23), as exosomes from various cell types have been associated with AD pathology (24–26). However, this contention has not yet been proven.

In the study reported here, we analyzed the immune response of activated human macrophage-like cells (U937) infected with Aa OMVs containing sRNAs and compared them with Aa exRNA-free OMVs using cytokine array assays. We analyzed the small exRNA expression profiles of U937 cells treated with Aa OMVs and investigated whether these cells can harbor small exRNAs of bacterial origin that are loaded into the host RISC and are able to regulate host target transcripts. We also speculated as to whether Aa OMVs can cross the BBB and found that Aa OMVs induce TNF-α in the mouse brain via their contained RNAs. We suggest that some of the small exRNAs in Aa can be transferred into host cells through OMVs and then be incorporated into the endogenous RISC complex, which would imply that small exRNAs are novel bacterial signaling molecules that play a critical role in regulating the host immune response. The function of these Aa OMVs and exRNAs is not limited to local immunity but can cross the BBB, implying that bacterial exRNAs induce neuroinflammatory diseases like AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture

Aa [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 33384; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA] was inoculated on brain heart infusion (BHI; Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA, USA) agar plates in an anaerobic incubator. After 24 h, colonies were picked and cultured in BHI medium for 48 h. The anaerobic incubator was maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2, 5% H2, and 90% N2. Supernatants were collected for OMV purification, and bacteria pellets were collected for RNA isolation and purity evaluation.

The U937 cells were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and then differentiated into macrophages by 100 ng/ml of propidium monoazide (PMA; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) for 48 h.

OMV samples preparation

Aa were grown anaerobically in BHI until the desired optical density was reached. The bacterial culture supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 6000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The bacterial culture supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm pore filter (MilliporeSigma) to remove remaining bacteria and was followed by ultrafiltration with a MasterFlex L/S complete pump system (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) and Pellicon 2 mini Ultrafiltration module (MilliporeSigma) for concentration. The OMV was obtained from the filtered and concentrated supernatant using ExoBacteria OMV Isolation Kits (SBI, Palo Alto, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated OMVs (50 μl) were treated with 1 μl of RNase A (1 U/μl; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and DNase I (2 U/μl; Thermo Fisher Scientific) to 1 ml of the OMVs and incubated at 37°C for 25 min. The OMV was purified again using ExoBacteria OMV Isolation Kits.

For the physical OMV lysis, 1 ml of the OMV was frozen and thawed 5 times followed by sonication for 30 s and then was placed in ice for 30 s. Subsequently, 1 μl of RNase A or DNase I was added to 1 ml of the lysed OMV and incubated at 37°C for 25 min (Fig. 1A). The purified OMVs were checked for sterility and stored at −80°C until needed.

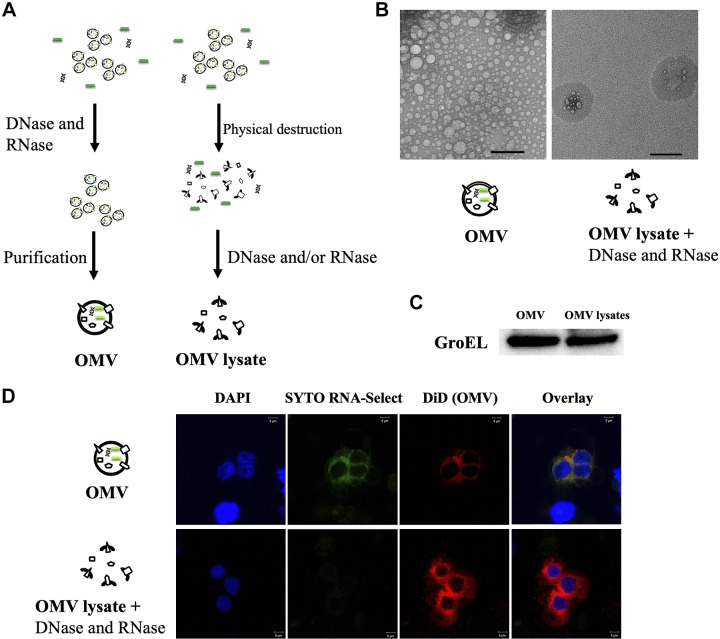

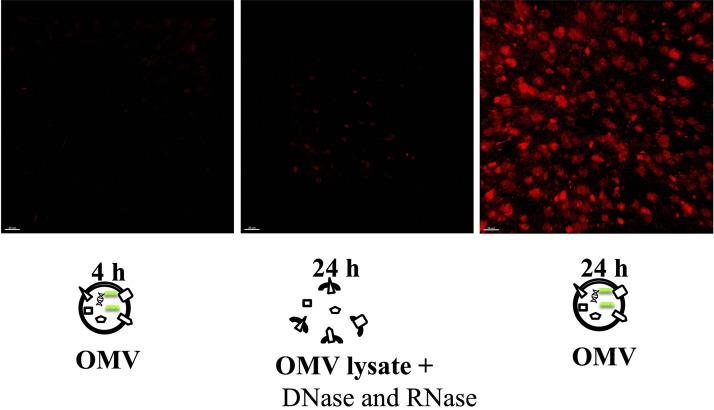

Figure 1.

Purification of Aa OMV and OMV lysates and deliberation into macrophage cells. A) Schematic diagram of Aa OMVs and OMV lysate purification. OMVs were purified using a purification kit, and RNase A or DNase I was used to remove free nucleic acids in OMV samples. B) Transmission electron micrograph of Aa OMVs. The images show small vesicles 10–60 nm in diameter (left panel). The right panel shows destructed Aa OMV particles, most regions with no particles at all, indicating complete OMV particle destruction. All panels are at original magnification, ×15,000. Scale bar, 100 nm. C) Western blot analysis of Aa OMVs using GroEL antibody. OMVs from Aa with intact (OMV) and OMV lysate were lysed to obtain proteins, and equal amounts (20 µg) were applied onto SDS-polyacrylamide gel. D) Spontaneous delivery of Aa OMVs and RNA into activated U937 cells. Aa OMVs (∼4.5 × 1011 particles) and OMV lysates (the same amount of proteins as in 4.5 × 1011 OMV particles) were prestained with lipid tracer dye DiD (red) and RNA-specific dye Syto RNA-Select (green). Stained OMVs and OMV lysates were incubated with activated U937 for 24 h at 37°C. Confocal microscopy analysis of Aa OMVs showed colocalized OMVs and contained RNA (overlay), whereas OMV lysates showed no RNA signal. All panels are at original magnification, ×1000. Scale bar, 5 μm.

For staining, OMVs (dissolved in 100 μl in PBS) and PBS (100 μl, dye control) were incubated with 2 μM Syto RNA-Select Green Fluorescent Cell Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10 μM red fluorescent Lipophilic Tracer 1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine, 4-chlorobenzenesulfonate salt (DiD; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for an hour at 37°C. Samples were washed once with PBS followed by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 g for 1 h at 4°C.

Both intact OMVs and lysed OMVs were tested for LPSs. LPS concentrations were determined with Pierce LAL Chromogenic Endotoxin Quantitation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

OMV analysis

OMVs were analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis using the NanoSight system (NanoSight NS300; Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s protocols as previously described (27). Samples were diluted 100 times in a total volume of 1 ml of PBS. Particle size was measured based on Brownian movement, and particle concentration was quantified in each sample. OMV quantification was done using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and the NanoSight system (detailed in Supplemental Fig. S1) (28).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Stained OMVs were added to PMA-pretreated U937 cells and incubated for 24 h at 37°C, then they were washed twice with PBS, followed by incubation with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Stained OMVs with added cells were visualized on a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM Zeiss 700; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Transmission electron microscopy

The purified OMV samples were diluted 20 times with PBS and applied to 200-mesh Formvar/Carbon grids (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA) without staining. OMV samples were dried overnight on the grids and viewed with an electron microscope (HT7700; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 100 kV.

Total RNA extraction

Total RNA was isolated using both Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germnay) according to each manufacturers’ protocols, with some modifications. Each sample was resuspended in 300 µl Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and homogenized. Then, an additional 700 µl Trizol was added to these samples and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Additionally, 200 µl 1-bromo-3-chloropropane (MilliporeSigma) was added to each sample, which was then incubated for 3 min. Samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant of each sample was mixed in 750 µl of 100% isopropanol. The mixed samples were incubated at −20°C for 2 h. The miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) was then used according to the manufacturer’s protocol to purify the sRNA-enriched RNA.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA (300 ng) was reverse transcribed using OmniScript (Qiagen). Diluted cDNA was used for the qRT‐PCR with TNF-α, TLR7/8, and GAPDH primer sets (Supplemental Table S1). The PCR was performed in 96‐well plates using the 7500 Real‐Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The expression of each gene was determined from 3 replicates in a single quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiment.

Total RNA sequencing and RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing

RNA was processed and used for deep sequencing by Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea). For Ago2 RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (RIP-Seq), 9 dishes of PMA-treated U937 cells were incubated with Aa OMVs. After 24 h, all culture medium was removed, each plate was washed with 10 ml of PBS, and the cells were collected and lysed using lysis buffer (50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 0.5% NP40, 0.5 mM DTT). Lysates were incubated with Dynabeads Protein G (Thermo Fisher Scientific) conjugated with an Ago2-specific mAb (ab57113; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or without the antibody [Total RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq)]. The beads were repeatedly washed with PBS, and then Trizol was added to extract bound RNA, which was subjected to sRNA deep sequencing. Cloning of sRNAs was performed as previously described (29, 30), with slight modifications. The quantity and quality of the total RNA were evaluated using RNA electropherograms (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, Prokaryote Total RNA Pico Kit; Santa Clara, CA, USA) and by assessing the RNA integrity number. The resulting RNA samples were processed for the sequencing libraries using the Illumina TruSeq small RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The purified small-sized cDNA library, amplified by 11 cycles of PCR, was used for cluster generation on Illumina’s Cluster Station following the TruSeq Small RNA Sample Preparation Guide (RS-200-9002DOC) and then sequenced with 50 cycles in single-read mode on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 System following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The raw RIP-Seq data are deposited at the Sequence Read Archive (SRA), available under Accession No. PRJNA530274 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA530274).

Bioinformatic analysis of deep sequencing

Bioinformatics analysis was conducted using Macrogen. The quality of the raw sequence reads was evaluated using the FastQC software v.0.11.7 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). The sequences of the adapters were trimmed using the mapper algorithm in the miRDeep2 software package (https://www.mdc-berlin.de/8551903/en/) (31, 32). Reads without adapter sequences or shorter than 15 nt after adapter trimming were filtered out and not used in subsequent analysis. The Rfam v.9.1 (http://rfam.xfam.org/) database was used for RNA family analysis. The reference Aa sequences and annotation information from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) were used to map raw sequence reads to Aa genomic sequence (NC_016513.1) and msRNA (SRS796228).

Western blots

Whole OMV protein extracts were prepared by using a 1× SDS loading buffer containing proteinase inhibitors boiled for 10 min. Twenty micrograms of each protein extract was loaded onto an SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The membrane was incubated in 5% skim milk/0.1% Tris-buffered saline–Tween 20 at room temperature for 30 min followed by incubation with a 1:1000 final diluted GroEL antibody (MilliporeSigma) and then an anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (7074; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

For NF-κB p65 and phosphorylated (phospho)-p65 Western blot, 20 μg of whole-cell lysates were used for SDS-running, followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was incubated in 5% skim milk/0.1% Tris-buffered saline–Tween 20 at room temperature for 30 min, followed by incubation with a 1:1000 final diluted NF-κB p65 (8242; Cell Signaling Technology) and phospho-p65 antibody (Ser536, 3033; Cell Signaling Technology) and then an anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (7074; Cell Signaling Technology).

Immunoassays of cytokines

PMA-treated U937 were incubated with purified OMVs. After 24 h, the filtrated supernatants were examined for 10 cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-23, and TNF-α) using a quantitative multiplex ELISA (Q-Plex Human Cytokine Arrays; Quansys Biosciences, Logan, UT, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Data were analyzed using Q-View Software (Quansys Biosciences). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Brain clearing

Mice (C57BL, 6-wk-old males) were deeply anesthetized using a rodent inhalation anesthesia apparatus (VetEquip, Livermore, CA, USA) equipped with vaporizers for isoflurane. As a carrier gas, 100% oxygen was used at a flow rate of 400 ml/min, and then the mice were given cardiac injections with 100 µl OMV solution for 4 or 24 h. Brains were cleared using the Binaree Brain Clearing Kit (SHBC-001; Binaree, Daegu, South Korea). Briefly, the uncleared brain was fixed for more than 12 h in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Subsequently, fixed brains were immersed in fixing solution for 24 h and then incubated with tissue-clearing solution in a shaking incubator at 35°C for 48 h. After 3 rinses in washing solution, the washed brain was incubated in mounting and storage solution (SHMS-050; Binaree).

For TNF-α immunostaining, anti–TNF-α antibody (ab6671; Abcam) was hybridized with 1:200 dilution after brain clearing. The tissue was washed for 1 d and incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (Alexa Fluor 594, ab150080; Abcam) for further fluorescence signal detection. The fluorescence signal was imaged using a Lightsheet Z.1 Fluorescence Microscope (LSFM; Carl Zeiss) with ×5/0.1 dual side illumination optic and Plan-Neofluar ×5/0.16 objective lenses (Carl Zeiss). Fluorescence was excited with 488 and 638 nm lasers, and emission was detected with 505–545 and 660 nm band-pass filters. All LSFM image data were saved in the .czi file type of Zen software (Carl Zeiss), and images were reconstructed and 3-dimensionally–rendered using Arivis Vison 4D Software (Arivis AG, Munich, Germany) and Imaris software (Bitplane, Belfast, United Kingdom). Whole LSFM images and image rendering data were acquired in the Brain Research Core Facility (BRCF) of the Korea Brain Research Institute.

The experiments were performed by Binaree, and the animal experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Dongguk University (IACUC-2017-015).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the means ± sd in the Results section. Significant variation analysis was used to calculate the parametric 2-tailed, nonpaired Student’s t test. All analyses were performed using Origin 8.0 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA), and values of P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Purification of Aa OMVs and OMV lysates and deliberation into macrophage cells

To exclude the effects of DNAs and RNAs outside of OMVs, studies were performed with DNase I and RNase A that were not OMV membrane permeable (20, 33) so that the nucleic acids inside might be assumed to be intact. Deconstructed Aa OMVs (OMV lysates) were compared with OMVs after treatment with DNase I and/or RNase A (Fig. 1A). Aa OMV sizes ranged from 10 to 60 nm, whereas OMV lysates showed only destructed particles when visible on the transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 1B). However, Western blot analysis of both Aa OMVs and OMV lysates showed evidence of the GroEL protein (Fig. 1C), which has been implicated as an immunodominant Aa antigen (34). Indeed, physical destruction did not change the concentration of LPS, with both intact and lysed OMVs showing ∼1 μg/ml of LPS from our preparation.

We then conducted confocal microscopy analysis of OMVs with RNAs inside. Vesicles of both OMV and OMV lysates appeared after treatment in activated U937 cells. Because Syto RNA-Select reagent is membrane permeable, it was possible to label RNAs inside OMVs, allowing RNAs to colocalize with OMV membranes inside U937 cells. OMV lysates did not appear to contain RNAs in U937 cells, suggesting that RNAs were completely removed by RNase A (Fig. 1D). This observation was consistent with previous data indicating that OMVs and the RNAs within them are internalized into mouse epithelial cells (21).

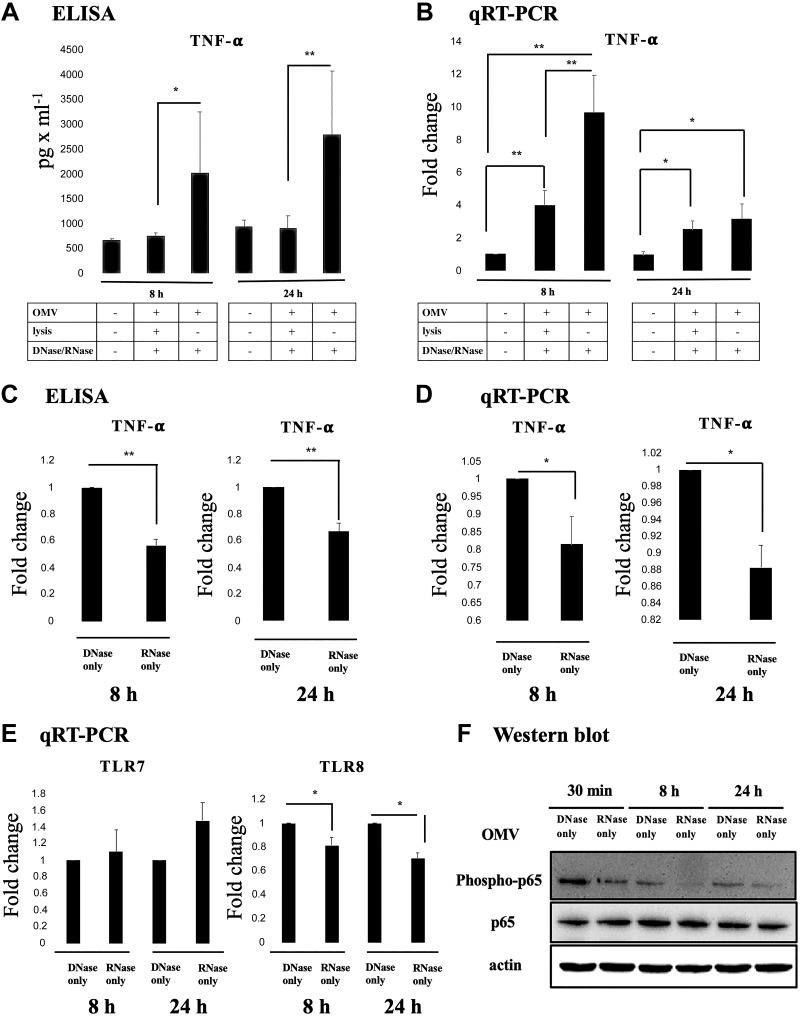

RNA in Aa OMV activates macrophage TNF-α via TLR-8

To investigate the effect of Aa OMV and RNAs in OMV on the macrophage cells, we treated Aa OMV and OMV lysate on activated U937 for 8 h or 24 h (the levels of LPS were ∼1 μg/ml in both OMV and OMV lysates). The levels of 10 cytokines (see Materials and Methods section) were examined using cytokine arrays. IL-2 and IL-13 levels were undetectable (unpublished results), whereas the levels of other cytokines were detectable (Supplemental Fig. S2). Among them, secreted TNF-α was more up-regulated by intact OMV compared with nuclease-treated OMV lysates, which showed lower levels of both TNF-α protein and transcript (Fig. 2A, B). Next, we investigated which nucleic acid is responsible for the suppressed TNF-α of OMV lysates treated with nucleases. OMV lysates were treated with DNase or RNase. The results indicated that the effect of reduced OMV lysate on U937 in terms of both released TNF-α cytokine and transcript level was significant in RNase only–treated Aa OMV lysates (Fig. 2C, D).

Figure 2.

RNA in Aa OMV activates macrophage TNF-α via the TLR-8–NF-κB signaling pathway. A) Secreted TNF-α protein levels were up-regulated at 8 and 24 h after treatment of intact OMV. Other cytokine levels are summarized in Supplemental Fig. S2. B) Transcript levels of TNF-α were up-regulated by intact OMV at 8 h but not at 24 h. C) Released TNF-α secretion by OMV lysate was decreased by RNase only–treated OMV lysates on activated U937 cells at 8 and 24 h. D) qRT-PCR analysis revealed that transcript levels of TNF-α activation by Aa OMV lysates were decreased by RNase-only pretreatment at both 8 and 24 h. E) Transcript levels of TLR-7 and TLR-8 were analyzed using qRT-PCR. TLR-8 of activated U937 cells was significantly decreased by RNase only–treated Aa OMV lysates at both 8 and 24 h, whereas TLR-7 did not show significant changes. F) NF-κB activation (phospho-p65, upper panel) was significantly decreased by RNase only–treated OMV lysates compared with DNase-treated OMV lystates at every time point we tested. Total NF-κB p65 (middle panel) and actin (bottom panel) were checked for controls. Aa OMVs (∼4.5 × 1010 particles) and OMV lysates (the same amount of proteins as in 4.5 × 1010 OMV particles) were treated to activated U937 cells. The data are presented as the means ± sd from 3 independent experiments. The data are presented as the means ± sd from more than 3 independent experiments. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01.

Viral nucleic acids are known to activate myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) via TLRs and NF-κB signaling in macrophages (35, 36). We therefore tested whether sRNAs in the OMVs stimulate TLRs and NF-κB pathways as do viral infections. To determine the signal cascade of TNF-α elevation by RNA-containing Aa OMVs in U937 cells, we compared TLR-7 and TLR-8 expression in DNase only–treated OMV lysates and RNase only–treated OMV lysates in activated U937 cells, as both TLR-7 and TLR-8 are responsible for single-stranded RNA-induced macrophage activation (37, 38). In our study, however, TLR-8 expression was significantly down-regulated in RNase only–treated OMV lysates at 8 h in U937 cells (Fig. 2E).

NF-κB activation by Aa OMV antigens has already been reported (39), but the effect of RNAs inside OMV has not been elucidated. Here, NF-κB activity was estimated by measuring phospho-p65, the activated form of NF-κB, which was also reduced by removal of RNA inside OMV using RNase, whereas total p65 expression did not show differences (Fig. 2F). This observation provides further evidence that RNAs inside Aa OMVs augment the activation of NF-κB via TLR-8.

miRNA-sized sRNAs of Aa OMV bind to host Ago2

We used an RIP-Seq approach to determine whether sRNAs in transferred Aa OMVs can bind to the host RISC, thereby functioning as exogenous miRNAs.

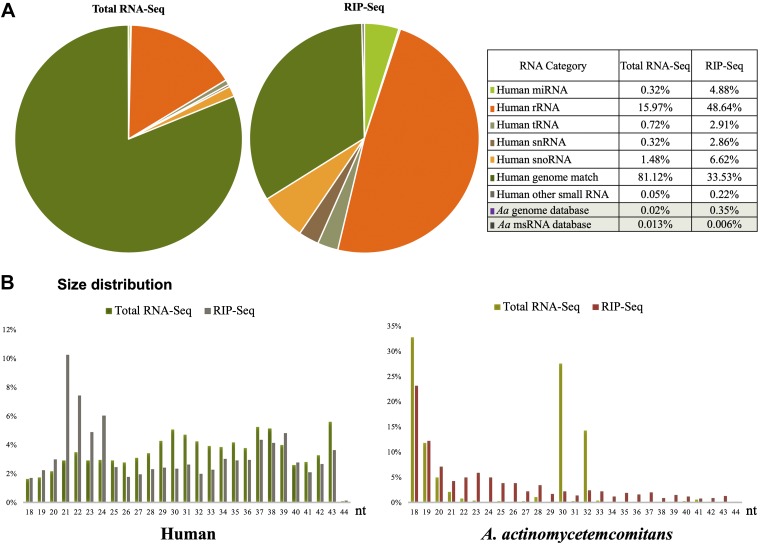

For total RNA-Seq, human U937 macrophage cells were infected with Aa OMVs at 4.5 × 1010 particles to 1 × 106 PMA-treated U937 cells. Next-generation sequencing (or deep sequencing) analysis of the total sRNA yielded 39.8 million reads that could be aligned to either the human or Aa genome. Of these, 0.02% were of Aa origin. A total of 5039 reads (0.013%) matched Aa sRNA sequences that our group had previously deposited (SRS5796228) (21). Next-generation sequencing of Ago2-associated sRNAs by RIP-Seq reads of the total sRNA yielded 24.9 million reads that could be aligned to either the human or Aa genome. Of these, 0.35% were of Aa origin. In total, 1572 reads (0.006%) were matched with Aa sRNA sequences that our group had previously deposited (SRS5796228) (21). The data are summarized in Fig. 3. Compared with our previous study of Aa sRNAs (SRS5796228), we found that more novel sRNAs in Ago2 bound sRNAs, suggesting that functionally relevant small exRNAs for host are different from sRNAs present in Aa cells. This indicates that the sRNAs in bacterial OMVs are differentially sorted or packaged, as previously observed (20), suggesting an unknown mechanism of sRNA loading into OMVs.

Figure 3.

RNA deep sequencing of sRNAs in Aa OMV-treated human macrophage cells. A) Dual RNA-Seq was performed. Gene annotation based on sequencing reads to either human or Aa genome. Previously identified msRNA in the Aa database (Aa msRNA database) were also used for aligning. Values indicate the percentage of reads of each gene type in either the total (Total RNA-Seq) or Ago2-immunoprecipitation (IP) from sRNA (RIP-Seq) libraries. B) Length distribution of reads. The x axis shows the length of sRNAs in nucleotides (nt); the y axis shows the percentage of reads of each length in the total (Total-RNA) or Ago2-IP (RIP-Seq) library from Aa OMV-treated human (left panel) and Aa (right panel).

This research has identified a number of Aa msRNAs incorporated into the RISC, showing a possible mechanism for the promotion of the host immune response or suppression of bacterial pathogenicity.

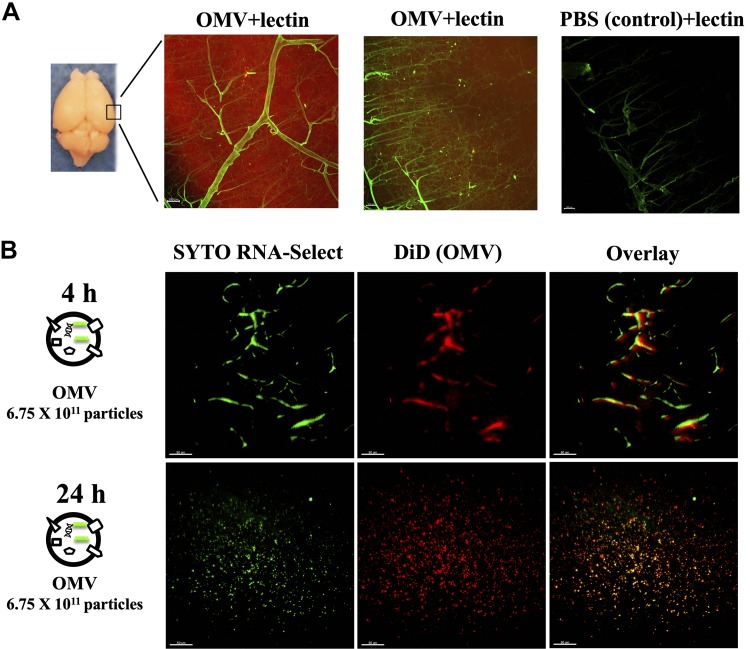

exRNAs-carrying Aa OMVs cross mouse BBB and induce TNF-α

EVs like exosomes in mice and humans are known to be delivered into the brain (23, 40, 41), but the mechanism of the crossing of the BBB by OMVs remains unclear. To test whether Aa OMVs can be spontaneously delivered into the mouse brain by crossing the BBB, we injected Aa OMVs into mice. Mouse brains were cleared after intracardiac injection of DiD dye and/or Syto RNA-Select stained Aa OMVs, followed by analysis of OMV and staining of RNA using 2D and 3D visualization tools. Initially, we observed stained OMVs (RNAs were not stained) 24 h after intracardiac injection. Red-stained vesicles spread around blood vessels (green lectin), whereas PBS controls did not show any signals (Fig. 4A). Next, we compared 4 and 24 h intracardiac injection of stained OMV and RNA. At 4 h, OMV and RNA within were still trapped in blood vessels but were well spread after 24 h injection (Fig. 4B). Dose-dependent signals of OMV and RNA inside were also observed by intracardiac injection after 24 h (Supplemental Movies S1–S3). TNF-α was also inspected after intracardiac injection of unstained OMVs after 24 h. TNF-α was well up-regulated by Aa OMVs at 24 h, whereas no TNF-α signal was detected at 4 h injection of OMVs (Fig. 5). It appears that Aa OMVs could cross mouse BBB and present in the brain 24 h after intracardiac injection, inducing the production of proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Fig. 6).

Figure 4.

Aa OMVs cross the BBB of mice. Two-dimensional lightsheet fluorescence microscopy analysis of the mouse brain (cortex). A) Lipid tracer dye was treated to OMV or PBS (control) then ultracentrifuged to remove unincorporated dye. The mouse brain was perfused 24 h after cardiac injection of stained OMV or PBS and cleared using the brain clearing (clarity) technique. Lectin was injected to present the brain vessels (green); OMVs are shown in red due to the lipid tracer dye DiD (red). Scale bar, 100 μm. B) Aa OMVs were prestained with lipid tracer dye DiD (red) and RNA-specific dye Syto RNA-Select (green) before injection in mice. The mouse brain was perfused 4 and 24 h after cardiac injection of stained OMVs. The 24 h cortex region shows red spots (OMV) and green spots (RNA inside OMVs), suggesting OMVs containing RNA can cross the BBB, whereas 4 h OMVs remain in brain vessels. Scale bars, 50 μm. Three-dimensional lightsheet analysis of the mouse cortex is presented in Supplemental Movies S1–S3.

Figure 5.

Aa OMV RNAs promote TNF-α in the mouse brain. Unstained OMVs and OMV lysates were intracardiacally injected into mice and analyzed in the brain using 2D lightsheet fluorescence microscopy. TNF-α expression elevated in intact OMV compared with OMV lysates with nucleases at 24 h. Aa OMVs were injected at ∼6.75 × 1011 particles (containing ∼150 μg of LPS) and OMV lysates (with nucleases and containing ∼150 μg of LPS) were treated with the same amount of protein levels as intact OMVs. Three-dimensional lightsheet analysis of the mouse cortex is presented in Supplemental Movies S4–S6. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Figure 6.

Graphic summary. Model of the Aa OMV sRNA mechanism of action in macrophage and the brain. Aa OMVs can be taken up by host macrophage cells and sRNAs inside OMVs, activating TNF-α expression via the TLR-8 and NF-κB signaling pathways. miRNA-like sRNAs in OMVs can bind host RISC and may modulate host genes. Aa OMVs can also cross the BBB, allowing sRNAs in OMV to promote neuroinflammation via TNF-α activation.

DISCUSSION

There is some evidence that oral pathogens implicated in neuroinflammatory diseases can be localized in the brain (13, 42), but how these microbes cross the BBB is debatable. It has been shown that EVs can facilitate the interkingdom exchange of RNAs as communication molecules (17, 43). Host cells probably take up the RNA cargo of OMVs along with the OMVs themselves (21). OMVs were first discovered in Vibrio cholerae in 1967 (44) but have not received much attention until recently. Recent findings suggest that OMVs are utilized by pathogens and commensal bacteria to manipulate the host immune response (45) and can even be used as a means of transporting DNA and RNA into host cells (20, 21, 33). In general, OMVs consist of microbe-associated molecular patterns, LPS, and peptidoglycans (46, 47). OMVs of Aa additionally possess a variety of biologically active molecules that might stimulate immune responses, including leukotoxin A (LtxA) and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) (48, 49). We previously identified msRNAs from 3 periodontopathogens (Aa, P. gingivalis, and T. denticola) that could be transferred into mouse fibroblast cells via OMVs and were shown to down-regulate several cytokines (21). Although the exact role of msRNAs in bacterial pathogens has not been fully determined, the invasion of activated macrophage cells by msRNAs via OMVs shown in this study suggests that exogenous msRNAs as exRNAs from commensal bacteria can be incorporated into the host RISC system, which then contributes to the regulation of host target transcripts. We have previously hypothesized the involvement of pathogenic factors and potential host transcript targets in host immune responses via bacterial msRNAs (21); our new findings suggest that sRNAs of bacterial origin can indeed act as exogenous miRNAs in host cells via direct infection or OMVs.

A previous study suggests that Aa can invade macrophages and induce proinflammatory cytokines in vitro (50). Other studies have also suggested that Aa invasion induces elevated production of IL-1β in macrophage cells via various pathways (50–52). Furthermore, LPS from Aa is indeed known to stimulate IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in human whole blood (53), which is consistent with our data except for the specific elevation of TNF-α protein by intact OMVs. The intact OMV and OMV lysates (both contain the same amount of LPS) for TNF-α expression were compared to remove the influence of LPS on TNF-α activation. Although the mRNA level of TNF-α was up-regulated in both intact OMV and OMV lysates, the effect was greater by intact OMV than OMV lysates (Fig. 2A, B). Taken together, this indicates that nucleic acids in Aa OMV additionally stimulate TNF-α stimulator along with LPS. Aa LPS has also been shown to activate expression of miR-29b in human macrophages, resulting in targeting of IL-6 receptor α (54), although the effect of sRNAs of Aa on these pathways is not fully understood. Additional experiments were conducted to determine which nucleic acids in OMVs are responsible for the TNF-α signaling pathways. We found that RNAs in Aa OMV were modulating expression of TNF-α, TLR-8, and phosphorylation of NF-κB (Fig. 2). It is well known that various viral single-stranded RNAs or synthetic single-stranded RNAs are recognized by TLR-7/8 in human macrophages (37, 38, 55). However, the recognition of RNAs by TLR-7 or 8 is species specific; for example, TLR-7 recognizes Streptococcus Group B RNA, whereas TLR-8 recognizes RNAs from Escherichia coli (36). Our data suggest that increased release of proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α by Aa OMVs occurs mainly via the TLR-8 pathway (Fig. 2E). Note also that NF-κB activation was significantly reduced by RNase treatment of OMV lysates (Fig. 2F). It thus may be that Aa OMV-mediated TNF-α up-regulation is mainly transduced via the TLR-8 and NF-κB signaling pathways.

It appears that OMVs can be taken up by host cells and can release molecules by several routes, such as a membrane-mediated process, a lipid raft, or membrane fusion (56, 57). We and other groups have previously shown that Aa OMVs can enter nonphagocytic cells, such as mouse fibroblast cells and human gingival fibroblast cells, possibly via clathrin (21, 39) or membrane fusion (48). In the current study, we show that Aa OMVs can enter human macrophage cells and release RNA there. Using Ago2 RIP-Seq analysis, we show that these sRNAs originate from Aa OMV incorporated into host Ago2, one of the key RISC components. This suggests that OMV sRNAs, in addition to having the characteristic functions of exogenous miRNAs, can act in a novel way as host regulators. Another study has suggested that a sRNA of Mycobacterium marinum is able to bind host RISC and demonstrates a eukaryotic miRNA character by direct infection of intracellular bacteria, although sRNAs from other intercellular bacteria are not generally RISC-associated (58). We note that Aa sRNAs recovered using RIP-Seq are expressed at meaningful levels, suggesting their possible functional relevance. Unfortunately, we could not find any highly expressed msRNAs that exactly match those identified in previous studies (21). This might suggest that different precursor processing occurs in Aa and humans, meaning that long precursor msRNAs are transferred into host cells and processed again to produce the mature form. We assumed that bacteria make pre-miRNA-like RNA in the cell, directly or indirectly, using a host dicer processing mechanism. Another possibility is that bacterial OMVs possess an exosomal miRNA-like sorting system that ensures that the exosomal and cellular compositions of miRNAs are different (17, 43, 59). Protein sorting would then only load selected sRNAs into OMVs. This hypothesis needs further support; clearly, intensive research is needed to elucidate the targets of bacterial OMV miRNAs and thus shed light on microbe-to-host regulatory mechanisms.

It has been proposed that proinflammatory cytokines resulting from periodontitis contribute to promoting the progression of AD (10, 60). One study speculated that antibodies against periodontal pathogens and proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, were elevated in the serum of patients with AD (12). The relationship between AD and periodontitis has mostly focused on LPS and other bacterial products that can cause local host responses and regionally generated inflammatory cytokines, which might gain access to the brain (60). Furthermore, although local host response and regionally generated inflammatory cytokines seem to be the main cause of AD, with no evidence that bacteria itself is the cause of AD until recently. Recent studies have shown the presence of periodontal pathogen P. gingivalis in the brains of individuals with AD (13). It remains unclear, however, how the periodontopathogen crosses the BBB to colonize the brain. Although a study has indicated that bacterial OMVs increase BBB permeability (61), the question of whether they can cross the BBB has not been resolved. We show, for the first time as far as we know, that OMVs can systemically cross the mouse BBB 24 h after intracardiac injection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Movies S1–S3). In addition, we are suggesting another mechanism, whereby exRNA in OMV stimulates the host response. Because OMVs contain various bioactive molecules, such as bacterial proteins and RNAs, OMVs from commensal bacteria may regularly affect brain function. Because the majority of EV RNA consists of sRNAs such as miRNAs and msRNAs (62, 63), it would not be surprising if commensal bacterial exRNAs affected the brain immune response via microbe-associated molecular patterns–pattern recognition receptor signaling pathways or by exogenous miRNAs incorporating into host RISC. Although the role of exogenous miRNAs needs further investigation, we have demonstrated that Aa exRNAs can promote the production of brain TNF-α (Fig. 5).

An association between AD and TNF-α has been repeatedly suggested (12, 64), and patients with periodontitis have been shown to have an elevated risk of AD (65). Our results imply that OMVs from periodontal pathogens cause AD via leaky gum. Therefore, appropriate and prompt treatments for periodontitis and the inhibition of oral bacteria OMV secretion may prevent AD and other neuroinflammatory diseases. Bacterial OMV-derived microbe-host genetic communication requires more extensive research not only at the site of symptoms and in the brain but also from a systemic perspective.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Eph Tunkle and Dr. Scott Young (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) for critical reading of this manuscript. This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Korean Government (MSIT 2017R1A5A2015391 and 2018R1D1A3B07043539). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- Aa

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Ago2

argonaute 2

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- BHI

brain heart infusion

- DiD

1,1'-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine, 4-chlorobenzenesulfonate salt

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- exRNA

extracellular RNA

- LSFM

Lightsheet Z.1 fluorescence microscope

- miRNA

microRNA

- msRNA

miRNA-sized sRNA

- OMV

outer membrane vesicle

- phospho

phosphorylated

- PMA

propidium monoazide

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- RIP-Seq

RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing

- sRNA

small RNA

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.-C. Han and S.-Y. Choi contributed to data collection and analysis and drafted the manuscript; Y. Lee, J.-W. Park, and S.-H. Hong contributed to data analysis and critically revised the manuscript; H.-J. Lee drafted the manuscript and contributed to data collection and analysis as well as conception and design; and all authors gave their final approval and agreed to be held accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yucel-Lindberg T., Båge T. (2013) Inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 15, e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Darveau R. P. (2010) Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paster B. J., Boches S. K., Galvin J. L., Ericson R. E., Lau C. N., Levanos V. A., Sahasrabudhe A., Dewhirst F. E. (2001) Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J. Bacteriol. 183, 3770–3783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graves D. (2008) Cytokines that promote periodontal tissue destruction. J. Periodontol. 79(Suppl), 1585–1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson B., Ward J. M., Ready D. (2010) Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans: a triple A* periodontopathogen? Periodontol. 2000 54, 78–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Könönen E., Müller H.-P. (2014) Microbiology of aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 65, 46–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishihara T., Koseki T. (2004) Microbial etiology of periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 36, 14–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konig M. F., Abusleme L., Reinholdt J., Palmer R. J., Teles R. P., Sampson K., Rosen A., Nigrovic P. A., Sokolove J., Giles J. T., Moutsopoulos N. M., Andrade F. (2016) Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced hypercitrullination links periodontal infection to autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 369ra176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pritchard A. B., Crean S., Olsen I., Singhrao S. K. (2017) Periodontitis, microbiomes and their role in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaur S., Agnihotri R. (2015) Alzheimer’s disease and chronic periodontitis: is there an association? Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 15, 391–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen I., Taubman M. A., Singhrao S. K. (2016) Porphyromonas gingivalis suppresses adaptive immunity in periodontitis, atherosclerosis, and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Oral Microbiol. 8, 33029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamer A. R., Craig R. G., Pirraglia E., Dasanayake A. P., Norman R. G., Boylan R. J., Nehorayoff A., Glodzik L., Brys M., de Leon M. J. (2009) TNF-alpha and antibodies to periodontal bacteria discriminate between Alzheimer’s disease patients and normal subjects. J. Neuroimmunol. 216, 92–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominy S. S., Lynch C., Ermini F., Benedyk M., Marczyk A., Konradi A., Nguyen M., Haditsch U., Raha D., Griffin C., Holsinger L. J., Arastu-Kapur S., Kaba S., Lee A., Ryder M. I., Potempa B., Mydel P., Hellvard A., Adamowicz K., Hasturk H., Walker G. D., Reynolds E. C., Faull R. L. M., Curtis M. A., Dragunow M., Potempa J. (2019) Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer's disease brains: evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H.-J. (2013) Exceptional stories of microRNAs. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 238, 339–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H.-J. (2014) Additional stories of microRNAs. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 239, 1275–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon Y. J., Kim O. Y., Gho Y. S. (2014) Extracellular vesicles as emerging intercellular communicasomes. BMB Rep. 47, 531–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi J.-W., Um J.-H., Cho J.-H., Lee H.-J. (2017) Tiny RNAs and their voyage via extracellular vesicles: secretion of bacterial small RNA and eukaryotic microRNA. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 242, 1475–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton J. G., Franklin J. L., Weaver A. M., Vickers K., Zhang B., Coffey R. J., Ansel K. M., Blelloch R., Goga A., Huang B., L’Etoille N., Raffai R. L., Lai C. P., Krichevsky A. M., Mateescu B., Greiner V. J., Hunter C., Voinnet O., McManus M. T. (2015) Biogenesis, delivery, and function of extracellular RNA. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 27494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry T., Pommier S., Journet L., Bernadac A., Gorvel J.-P., Lloubès R. (2004) Improved methods for producing outer membrane vesicles in gram-negative bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 155, 437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koeppen K., Hampton T. H., Jarek M., Scharfe M., Gerber S. A., Mielcarz D. W., Demers E. G., Dolben E. L., Hammond J. H., Hogan D. A., Stanton B. A. (2016) A novel mechanism of host-pathogen interaction through sRNA in bacterial outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi J.-W., Kim S. C., Hong S.-H., Lee H. J. (2017) Secretable small RNAs via outer membrane vesicles in periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 96, 458–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi J.-W., Kwon T.-Y., Hong S.-H., Lee H.-J. (2018) Isolation and characterization of a microRNA-size secretable small RNA in Streptococcus sanguinis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 76, 293–301; erratum: 441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.András I. E., Toborek M. (2015) Extracellular vesicles of the blood-brain barrier. Tissue Barriers 4, e1131804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuyama K., Sun H., Usuki S., Sakai S., Hanamatsu H., Mioka T., Kimura N., Okada M., Tahara H., Furukawa J., Fujitani N., Shinohara Y., Igarashi Y. (2015) A potential function for neuronal exosomes: sequestering intracerebral amyloid-β peptide. FEBS Lett. 589, 84–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuyama K., Sun H., Sakai S., Mitsutake S., Okada M., Tahara H., Furukawa J., Fujitani N., Shinohara Y., Igarashi Y. (2014) Decreased amyloid-β pathologies by intracerebral loading of glycosphingolipid-enriched exosomes in Alzheimer model mice. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 24488–24498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dinkins M. B., Dasgupta S., Wang G., Zhu G., Bieberich E. (2014) Exosome reduction in vivo is associated with lower amyloid plaque load in the 5XFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 1792–1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Njock M.-S., Cheng H. S., Dang L. T., Nazari-Jahantigh M., Lau A. C., Boudreau E., Roufaiel M., Cybulsky M. I., Schober A., Fish J. E. (2015) Endothelial cells suppress monocyte activation through secretion of extracellular vesicles containing antiinflammatory microRNAs. Blood 125, 3202–3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi S.-Y., Han E.-C., Hong S.-H., Kwon T.-G., Lee Y., Lee H.-J. (2019) Regulating osteogenic differentiation by suppression of exosomal microRNAs. Tissue Eng. Part A. 25, 1146–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee H.-J., Hong S.-H. (2012) Analysis of microRNA-size, small RNAs in Streptococcus mutans by deep sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 326, 131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hafner M., Landgraf P., Ludwig J., Rice A., Ojo T., Lin C., Holoch D., Lim C., Tuschl T. (2008) Identification of microRNAs and other small regulatory RNAs using cDNA library sequencing. Methods 44, 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedländer M. R., Chen W., Adamidi C., Maaskola J., Einspanier R., Knespel S., Rajewsky N. (2008) Discovering microRNAs from deep sequencing data using miRDeep. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedländer M. R., Mackowiak S. D., Li N., Chen W., Rajewsky N. (2012) miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 37–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bitto N. J., Chapman R., Pidot S., Costin A., Lo C., Choi J., D’Cruze T., Reynolds E. C., Dashper S. G., Turnbull L., Whitchurch C. B., Stinear T. P., Stacey K. J., Ferrero R. L. (2017) Bacterial membrane vesicles transport their DNA cargo into host cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 7072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kieselbach T., Zijnge V., Granström E., Oscarsson J. (2015) Proteomics of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans outer membrane vesicles. PLoS One 10, e0138591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arango Duque G., Descoteaux A. (2014) Macrophage cytokines: involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 5, 491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen N., Xia P., Li S., Zhang T., Wang T. T., Zhu J. (2017) RNA sensors of the innate immune system and their detection of pathogens. IUBMB Life 69, 297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gantier M. P., Tong S., Behlke M. A., Xu D., Phipps S., Foster P. S., Williams B. R. G. (2008) TLR7 is involved in sequence-specific sensing of single-stranded RNAs in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 180, 2117–2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han X., Li X., Yue S. C., Anandaiah A., Hashem F., Reinach P. S., Koziel H., Tachado S. D. (2012) Epigenetic regulation of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) release in human macrophages by HIV-1 single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) is dependent on TLR8 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13778–13786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thay B., Damm A., Kufer T. A., Wai S. N., Oscarsson J. (2014) Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans outer membrane vesicles are internalized in human host cells and trigger NOD1- and NOD2-dependent NF-κB activation. Infect. Immun. 82, 4034–4046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan D., Zhao Y., Banks W. A., Bullock K. M., Haney M., Batrakova E., Kabanov A. V. (2017) Macrophage exosomes as natural nanocarriers for protein delivery to inflamed brain. Biomaterials 142, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsumoto J., Stewart T., Banks W. A., Zhang J. (2017) The transport mechanism of extracellular vesicles at the blood-brain barrier. Curr. Pharm. Des. 23, 6206–6214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Y., Du S., Johnson J. L., Tung H.-Y., Landers C. T., Liu Y., Seman B. G., Wheeler R. T., Costa-Mattioli M., Kheradmand F., Zheng H., Corry D. B. (2019) Microglia and amyloid precursor protein coordinate control of transient Candida cerebritis with memory deficits. Nat. Commun. 10, 58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee H.-J. (2019) Microbe-host communication by small RNAs in extracellular vesicles: vehicles for transkingdom RNA transportation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chatterjee S. N., Das J. (1967) Electron microscopic observations on the excretion of cell-wall material by Vibrio cholerae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 49, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaparakis-Liaskos M., Ferrero R. L. (2015) Immune modulation by bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuehn M. J., Kesty N. C. (2005) Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host-pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 19, 2645–2655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bomberger J. M., Maceachran D. P., Coutermarsh B. A., Ye S., O’Toole G. A., Stanton B. A. (2009) Long-distance delivery of bacterial virulence factors by Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rompikuntal P. K., Thay B., Khan M. K., Alanko J., Penttinen A.-M., Asikainen S., Wai S. N., Oscarsson J. (2012) Perinuclear localization of internalized outer membrane vesicles carrying active cytolethal distending toxin from Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Infect. Immun. 80, 31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kato S., Kowashi Y., Demuth D. R. (2002) Outer membrane-like vesicles secreted by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans are enriched in leukotoxin. Microb. Pathog. 32, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Okinaga T., Ariyoshi W., Nishihara T. (2015) Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans invasion induces interleukin-1β production through reactive oxygen species and cathepsin B. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 35, 431–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ando-Suguimoto E. S., da Silva M. P., Kawamoto D., Chen C., DiRienzo J. M., Mayer M. P. A. (2014) The cytolethal distending toxin of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans inhibits macrophage phagocytosis and subverts cytokine production. Cytokine 66, 46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Belibasakis G. N., Johansson A. (2012) Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans targets NLRP3 and NLRP6 inflammasome expression in human mononuclear leukocytes. Cytokine 59, 124–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schytte Blix I. J., Helgeland K., Hvattum E., Lyberg T. (1999) Lipopolysaccharide from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans stimulates production of interleukin-1beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in human whole blood. J. Periodontal Res. 34, 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naqvi A. R., Fordham J. B., Khan A., Nares S. (2014) MicroRNAs responsive to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS modulate expression of genes regulating innate immunity in human macrophages. Innate Immun. 20, 540–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parameswaran N., Patial S. (2010) Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 20, 87–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Donoghue E. J., Krachler A. M. (2016) Mechanisms of outer membrane vesicle entry into host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1508–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulcahy L. A., Pink R. C., Carter D. R. F. (2014) Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 3, 24641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furuse Y., Finethy R., Saka H. A., Xet-Mull A. M., Sisk D. M., Smith K. L. J., Lee S., Coers J., Valdivia R. H., Tobin D. M., Cullen B. R. (2014) Search for microRNAs expressed by intracellular bacterial pathogens in infected mammalian cells. PLoS One 9, e106434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kourembanas S. (2015) Exosomes: vehicles of intercellular signaling, biomarkers, and vectors of cell therapy. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 13–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamer A. R., Craig R. G., Dasanayake A. P., Brys M., Glodzik-Sobanska L., de Leon M. J. (2008) Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease: possible role of periodontal diseases. Alzheimers Dement. 4, 242–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wispelwey B., Hansen E. J., Scheld W. M. (1989) Haemophilus influenzae outer membrane vesicle-induced blood-brain barrier permeability during experimental meningitis. Infect. Immun. 57, 2559–2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garcia-Contreras M., Shah S. H., Tamayo A., Robbins P. D., Golberg R. B., Mendez A. J., Ricordi C. (2017) Plasma-derived exosome characterization reveals a distinct microRNA signature in long duration Type 1 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 7, 5998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ghosal A., Upadhyaya B. B., Fritz J. V., Heintz-Buschart A., Desai M. S., Yusuf D., Huang D., Baumuratov A., Wang K., Galas D., Wilmes P. (2015) The extracellular RNA complement of Escherichia coli. MicrobiologyOpen 4, 252–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao L., Xu T., Huang G., Jiang S., Gu Y., Chen F. (2018) Oral microbiomes: more and more importance in oral cavity and whole body. Protein Cell 9, 488–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi S., Kim K., Chang J., Kim S. M., Kim S. J., Cho H. J., Park S. M. (2019) Association of chronic periodontitis on Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 1234–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.