Abstract

General anesthesia has been the requisite component of surgical procedures for over 150 yr. Although immunomodulatory effects of volatile anesthetics have been growingly appreciated, the molecular mechanism has not been understood. In septic mice, the commonly used volatile anesthetic isoflurane attenuated the production of 5-lipoxygenase products and IL-10 and reduced CD11b and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on neutrophils, suggesting the attenuation of TLR4 signaling. We confirmed the attenuation of TLR4 signaling in vitro and their direct binding to TLR4–myeloid differentiation-2 (MD-2) complex by photolabeling experiments. The binding sites of volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane were located near critical residues for TLR4–MD-2 complex formation and TLR4–MD-2–LPS dimerization. Additionally, TLR4 activation was not attenuated by intravenous anesthetics, except for a high concentration of propofol. Considering the important role of TLR4 system in the perioperative settings, these findings suggest the possibility that anesthetic choice may modulate the outcome in patients or surgical cases in which TLR4 activation is expected.—Okuno, T., Koutsogiannaki, S., Hou, L., Bu, W., Ohto, U., Eckenhoff, R. G., Yokomizo, T., Yuki, K. Volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane directly target and attenuate Toll-like receptor 4 system.

Keywords: anesthesia, TLR4, sepsis

Sepsis continues to be a healthcare burden with high morbidity and mortality (1). In a typical infection, the host mounts a self-limited inflammatory response to contain and clear pathogens without sequelae. In contrast, severe sepsis, in which microorganisms overwhelm the host, demonstrates uncontrolled systemic inflammation accompanied by organ dysfunction, shock, and death (2). The immune response relies on host- and pathogen-derived signals called danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, respectively, recognition receptors on innate immune cells, particularly neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, to trigger the production of various mediators, including cytokines, chemokines, and lipid mediators (2). These mediators orchestrate the modulation of the immune system and dictate sepsis progression (3). TLRs are some of the major pattern recognition receptors for DAMPs and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (4). Among them, TLR4, the first cloned TLR, binds to multiple ligands, including LPS and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1), and plays a significant role in sepsis, as indicated by studies using both blocking antibodies and knockout mice (5, 6). In addition to TLR4, adhesion receptors, chemokine receptors, and phagocytosis receptors are critical for innate immune cells in sepsis.

General anesthesia is administered to a large number of patients with sepsis for surgical procedures, diagnostic procedures, and sedation in intensive care units in daily practice. The primary role of anesthetic drugs is to provide analgesia, amnesia, and immobility by affecting their proposed target receptors, such as the GABA type A receptor, NMDA receptor, and 2-pore-domain K+ channel in the CNS (7), but it has been increasingly appreciated that they affect host immune function (8). Although there are no clinical studies comparing the use of volatile anesthetics vs. intravenous anesthetics for the outcome of patients with sepsis, it is critical to understand the effect of these commonly used anesthetics on immune function and give them potential consideration in the meantime.

Here we primarily focused on studying the impact of isoflurane on the production of inflammatory mediators and the expression of adhesion molecules, phagocytic receptors, and chemotaxis receptors during sepsis. We hypothesized that the volatile anesthetics affected TLR4 signaling based on our data of mediators and receptors. We identified that the commonly used volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane directly targeted TLR4 and its adaptor protein myeloid differentiation-2 (MD-2). We also tested a number of commonly used intravenous anesthetics for comparison. We expect that our study would be of significant help in dissecting a number of the previously published results of anesthetic studies and would also provide the foundation to rethink how anesthetics should be chosen in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and inbred in our animal facilities. All mice were on the C57BL/6 background and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with 12-h light/dark cycles. Male mice from 8–10 wk of age were used for the experiments.

Cecal ligation and puncture model

All the experimental procedures complied with institutional and Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guidelines regarding the use of animals in research (4) and were approved by Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Polymicrobial abdominal sepsis was induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) surgery as we previously performed (5). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Following exteriorization, the cecum was ligated at 1.0 cm from its tip and subjected to a single, through-and-through puncture using an 18-gauge needle. A small amount of fecal material was expelled with gentle pressure to maintain the patency of puncture sites. The cecum was inserted into the abdominal cavity. Warmed saline (0.1 ml/g) saline was administered subcutaneously. Buprenorphine was given subcutaneously to alleviate postoperative surgical pain. Some groups of mice were placed on the nose cone and continuously exposed to 1% isoflurane using vaporizer (VetQuip, Eastern Creek, NSW, Australia) for 6 h. Mice were euthanized at indicated time points in the Results section and were subjected to analysis. After euthanization, blood was immediately collected. The peritoneum was exposed, and ice-cold PBS was injected into the peritoneal cavity. Collected fluid was centrifuged immediately at 200 g for 5 min. Supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until use.

Aerobic culture of peritoneal fluid

At 6 h after CLP surgery, we obtained peritoneal lavage fluid and spread over blood agar plates (tryptic soy agar with 5% sheep blood). Colonies were picked and subjected to bacterial strain analysis in clinical microbiology core at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Whole blood stimulation

Peripheral blood was obtained from healthy donors containing heparin. Heparinized blood was preincubated with LPS (final concentration: 1 µg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C and then stimulated with N-formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) (final concentration: 0.1 µM) for 15 min at 37°C as previously described by Doerfler et al. (6). Some samples were exposed to TLR4 inhibitor resatorvid (TAK-242; final concentration: 1 µM) (7) and isoflurane (1%). The reaction was immediately stopped at 0°C, and samples were centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min. Serum was collected for lipid measurement (8).

Eicosanoid lipidomics

Reverse-phase mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantitation technique for eicosanoids was previously described by Okuno et al. (9). The lipids were extracted with methanol and diluted with water containing 0.1% formic acid to yield a final methanol concentration of 20%. After addition of deuterium-labeled internal standards, the samples were loaded on Oasis HLB cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The column was washed with 1 ml of water, 1 ml of 15% methanol, and 1 ml of petroleum ether and then eluted with 0.2 ml of methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. Eicosanoids were quantified by reverse-phase HPLC–electrospray ionization-tandem MS method.

Mouse serum and peritoneal cytokines

Mouse Th1/Th2 9-Plex Ultra-Sensitive Kit (Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA) was used to measure the levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), IL-10, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-12 in the serum and peritoneal lavage fluid by employing the electrochemiluminescence detection technology.

Mouse whole blood flow cytometry

Following incubation with Fc-blocking antibody, surface expressions of CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2), and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) were probed using M17/4 (CD11a), M1/70 (CD11b), N418 (CD11c), SA044G4 (CXCR2), YN1/1.7.4 (ICAM-1), 7A8 [leukotriene B(4) receptor (BLT1)], or ×54-5/7.1 (FcR I) antibodies, respectively. FcR II/III expression was probed without Fc blocking using a 93 antibody. Erythrocytes were lyzed using lysis buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Neutrophil population was gated by anti-Ly6G antibody-positive population. All the antibodies except 7A8 were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA). 7A8 was originally developed and reported by us (10).

Mouse whole blood stimulation with LPS

Whole blood was stimulated with LPS for 4 h and subjected to cell surface CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, CXCR2, BLT1, ICAM-1, FcR I, and FcR II/III expression analysis.

The NF-κB activation of Raw-blue cells and THP-1–blue cells by LPS

Raw-blue cells are mouse Raw264.7 cells with chromosomal integration of a secreted embryonic alkaline phosphate (SEAP) reporter construct inducible by NF-κB (11). Similarly, THP-1–blue cells are a human monocytic leukemia cell line with an NF-κB–inducible SEAP reporter (11). Both cell lines were from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA) and maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum/1% antibiotic-antimicotic/2 mM l-glutamine/10% 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid. The stimulation of Raw-blue cells with LPS was performed with or without soluble MD-2 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) under volatile anesthetic exposure. Cells were exposed to isoflurane or sevoflurane in an air-tight chamber as we previously reported (12). For THP-1 cells, LPS stimulation was done with or without volatile anesthetics (isoflurane, sevoflurane) or intravenous anesthetics (propofol, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, etomidate) for 6 h. NF-κB activation was assessed by quantitating SEAP in the medium per the company protocol.

Photolabeling of azi-isoflurane and azi-sevoflurane with TLR4–MD-2 complex protein

Stable 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) expression plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Marcia Newcomer (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA). The expression of stable 5-LOX was performed as previously described by Gilbert et al. (13). Photolabeling of stable 5-LOX protein using azi-isoflurane (14) was also performed as previously described by Yuki et al. (12). TLR4–MD-2 complex was purified using Drosophilia S2 cells stably cotransfected with the expression vector metallothionein promoter/BiP/V5-His (pMT/BiP/V5-His) inserted either with the extracellular domain of TLR4 (residues 23–629) or MD-2 (residues 19–160) as previously reported (15). Azi-isoflurane or azi-sevoflurane (final concentration 50 µM for TLR4–MD-2 experiment, 100 µM for 5-LOX experiment) was equilibrated with proteins (1 mg/ml) in a reaction volume of 300 µl for 10 min and then exposed to 300 nm light for 25 min using Rayonet RPR-3000 Lamp (Southern New England Ultraviolet, Branford, CT, USA). The protein was separated by SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie G-250 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The protein gel band was excised for liquid chromatography–MS. After trypsin digestion, samples were injected into a C18 nano–liquid chromatography column with online electrospray into a Thermo LTQ Orbitrap XL Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Raw data were acquired with XCalibur (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and MaxQuant was used to search b and y ions against the sequence of 5-LOX, TLR4, or MD-2. Search parameters were 1 amu parent ion tolerance, 1 amu fragment ion tolerance, full tryptic digest, 1 missed cleavage, methionine oxidation (+15.99491), and cysteine alkylation (+57.02146) as a fixed modification. Filter parameters were Xcorr scores (+1 ion) 1.5, (+2 ion) 2.0, (+3 ion) 2.5, deltaCn 0.08, and peptide probability >0.05. Photolabeled peptides were searched with the additional dynamic azi-sevoflurane (+230.0559 m/z) or azi-isoflurane (+195.97143 m/z) modifications. MS work was performed at the Proteomics Core Facility of the Wistar Institute (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA). To check specificity of adducted residues in photolabeling experiments, nonphotolabeled isoflurane or sevoflurane was treated in a manner similar to control for false-positive detection of photoaffinity ligand modifications as we previously performed (16).

Rigid docking simulation of TLR4-isoflurane and sevoflurane complex

The structure of TLR4–MD-2 was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.wwpdb.org/) 3FXI. Right docking was performed using Autodock Vina (Scripps Laboratories, San Diego, CA, USA). Isoflurane- or sevoflurane-binding position was sought with the grid size of 20 × 20 × 20 Å3, using each adducted residue from photolabeling experiment as a grid center. No positional constraint was applied. We selected the docking position with the highest predicted affinity.

Statistics

Data were analyzed as indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. All the statistical calculations were performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

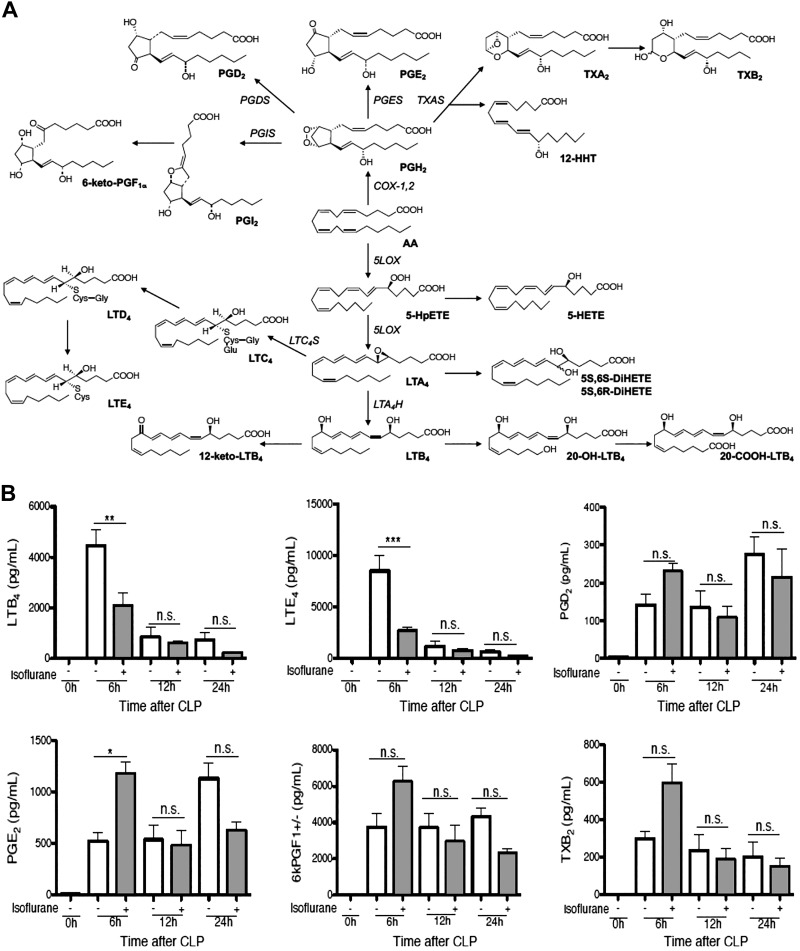

Isoflurane exposure attenuated the levels of 5-LOX products in sepsis

Once infection occurs, innate immune cells respond to cues, such as chemoattractants, and are recruited to the site of infection. Leukotriene (LT) B4 is a critical chemoattractant and a lipid mediator that belongs to the eicosanoid group. Eicosanoids are arachidonic acid (AA)-derivatives, including LTs and prostaglandins (PGs), and are important lipid mediators in sepsis pathophysiology (17–20). In contrast to many cytokines and chemokines that are produced by both innate and adaptive immune cells, eicosanoids are mainly produced by innate immune cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells, representing innate immune cell profiles (21). AA is oxygenated by 5-LOX, assisted by 5-LOX–activating protein, into the unstable epoxide LTA4. This intermediate is hydrolyzed by LTA4 hydrolase into LTB4 or conjugated with glutathione by LTC4 synthase to form Cys-LTs (LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4) (Fig. 1A) (22). Cys-LTs are important in vascular permeability in sepsis (19). Cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 catalyze the conversion of AA to PGH2 in PG biosynthesis (23). Based on this knowledge, we first tested the effect of isoflurane on the eicosanoids profile in peritoneal lavage samples from septic mice at 0, 6, 12, and 24 h after CLP by MS. A group of mice was subjected to 1% isoflurane exposure for 6 h immediately after CLP surgery. Isoflurane exposure significantly attenuated the production of LTB4 and LTE4 but did not reduce PGs and thromboxane B2 in septic mice at 6 h after CLP (Fig. 1B). In addition, isoflurane attenuated the levels of 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; 5-hydroxyicosapentaenoic acid; 5(S),6(S)-dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (DiHETE) (or 5S6S-DiHETE); 5(S),6(R)-DiHETE (5S6R-DiHETE); and 12-keto LTB4, all of which are 5-LOX derivatives (Fig. 1C). Previously we have shown that intravenous anesthetic propofol directly bound to and attenuated 5-LOX (9). Thus, we tested if isoflurane also directly bound to 5-LOX using photoactivatable isoflurane (azi-isoflurane). We did not observe any adducted residues (Supplemental Fig. S1A), suggesting that isoflurane does not bind directly to 5-LOX.

Figure 1.

The effect of volatile anesthetic isoflurane on the production of lipid mediators. A) Lipid mediator cascade derived from AAs. B, C). Mice were subjected to CLP surgery under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia, and then a group of mice were exposed to 1% isoflurane for 6 h. Peritoneal lavage fluid was collected at different time points after CLP surgery as indicated in figures. Lipid mediators originated from AAs were measured. Data were shown as means ± sd of 4 mice at each time point; n.s., not significant. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. 5-LOX–mediated lipid mediators were measured. 5-Hydroxyicosapentaenoic acid was a 5-LOX–derived lipid mediator from eicosapentaenoic acid. Other lipid mediators were 5-LOX derived from AAs. Data were shown as means ± sd of 4 mice at each time point; n.s., not significant. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 D). The role of LPS priming in the production of AA-derived lipid mediators was examined. Whole blood was primed with LPS (1 µg/ml) and stimulated with fMLP (0.1 µM). As a TLR4 inhibitor, TAK-242 (1 µM) was used. Isoflurane (ISF, 1%) was exposed to a group of samples. Data were shown as means ± sd of quadruplicates; n.s., not significant. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

LPS priming via TLR4 enhanced fMLP-induced production of 5-LOX–derived lipid mediators

The previous studies showed that LPS priming significantly increased the production of LTB4 under fMLP, opsonized zymosan, A23187, or phorbol myristate-acetate (PMA) stimulation, whereas LPS alone minimally affected LTB4 production (6, 8). A23817 and PMA are not physiologic stimulants. Zymosan is a yeast cell wall derivative (24). Sepsis induced by CLP surgery is caused by a combination of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial strains (25), and A23187, PMA, or zymosan would not be a relevant stimulant to our sepsis model. As predicted, aerobic culture of peritoneal lavage fluid in mice at 6 h after CLP grew both gram-positive species (Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus) and gram-negative species (Escherichia coli and Klebsiella oxytoca). The identified gram-negative species produce LPS and N-formyl methionyl peptides, both of which play a critical role in sepsis (26, 27). A combination of LPS priming and fMLP stimulation would fit with the scenario of our sepsis model. Although the previous study implied that LPS priming enhanced 5-LOX function (8), it is not clear yet whether LPS priming and fMLP stimulation produce only 5-LOX derivatives or other eicosanoids. Our data showed that LPS priming significantly enhanced the production of 5-LOX derivatives, including LTB4, LTB4-derivatives (20-COOH-LTB4, 20-OH-LTB4), LTE4, and 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid but did not affect PGs (Fig. 1D), suggesting that LPS priming via TLR4 affected the 5-LOX pathway specifically. Notably, LPS alone or fMLP alone did not produce a significant amount of LTB4. The administration of isoflurane alone, TAK-242 alone, and the combination of both significantly reduced 5-LOX derivatives (Fig. 1D). Lipid mediator profiles in both isoflurane- and TAK-242–treated samples showed similarity.

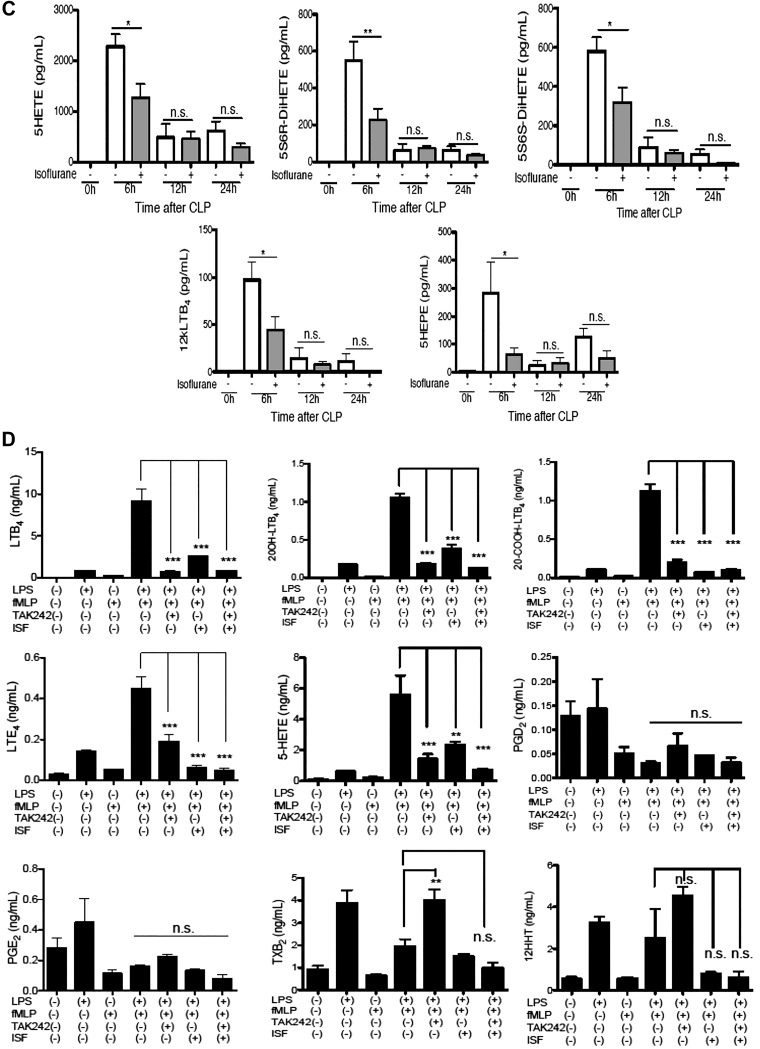

Isoflurane exposure attenuated IL-10 production in sepsis

Next, we examined the effect of isoflurane on cytokine and chemokine production. Our analysis showed that isoflurane exposure attenuated IL-10 production in blood and peritoneal lavage fluid in septic mice (Fig. 2A, B). Given that isoflurane is a short-acting drug, it was not unexpected to see no difference in IL-10 level at 12 h after CLP. Blood IL-12 level was not statistically higher in isoflurane group than in control group, but IL-12 level in peritoneal lavage fluid was significantly higher in isoflurane group than in control group. The result fit with the fact that IL-10 mediates the suppression of IL-12 transcriptionally (28). IL-10 is produced mainly by neutrophils following CLP surgery (29). The stimulation of neutrophils with LPS also induced their IL-10 expression (30). In addition to TLR4, LPS also directly binds to intracellular caspase-11 and enhances the production of IL-1β (31). However, isoflurane exposure did not affect IL-1β level in our sepsis model. This data, along with the aforementioned lipid mediator data, let us hypothesize that isoflurane would inhibit the TLR4 pathway.

Figure 2.

The effect of isoflurane on cytokine production and neutrophil receptor expression in septic mice. A, B) A panel of cytokines was measured in mice subjected to CLP surgery under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. A group of mice was exposed to 1% isoflurane for 6 h following CLP procedure. Blood (A) and peritoneal lavage fluid (B) were collected at different time points after CLP surgery as indicated in figures. Data are shown as means ± sd of 4 mice at each time point. N.s., not significant. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. C, D) Blood was collected at different time points after CLP surgery as indicated in figures. Neutrophils were gated as Ly6G-positive population. CD11b and CD11c can be also categorized as complement receptors. Data are shown as means ± sd of 4 mice at each time point. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; n.s., not significant. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Representative histograms for CD11b and ICAM-1 expression on neutrophils gated as Ly6G positive population (D). E) Whole blood was stimulated with LPS (1 µg/ml) with or without isoflurane (1%). ICAM-1 expression on neutrophils (Ly6G-positive) was probed. Baseline indicates no incubation. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Isoflurane exposure attenuated CD11b and ICAM-1 expression on neutrophils

LTB4 and IL-10 are mainly produced by neutrophils in the CLP model (29). Our previous study showed that neutrophils were recruited to the site of infection at earlier time points, such as 6 and 12 h after CLP, compared with other leukocytes (5). Thus, we studied the effect of isoflurane on neutrophils in the subsequent investigation. We examined the expression of adhesion molecules (CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, ICAM-1), chemotaxis receptors (CXCR2, BLT1), and phagocytosis receptor [complement receptors (CD11b, CD11c) and FcRs (FcR I, FcR II/III)] on neutrophils. Neutrophils were gated as Ly6G-positive population. We found that the surface expression of CD11b and ICAM-1 significantly increased by 6 h after CLP, and isoflurane exposure mitigated this change (Fig. 2C, D). ICAM-1 expression level continued to increase until 12 h after CLP, and isoflurane exposure attenuated it (Fig. 2C). Because isoflurane was exposed to mice only for the first 6 h after CLP surgery, the direct isoflurane effect would not be expected beyond the duration of exposure. However, isoflurane interaction with target can affect signaling events triggered through “the target” and produce effects beyond the exposure time. In contrast to ICAM-1 and CD11b, isoflurane exposure did not affect the expression of CD11a, CD11c, CXCR2, BLT1, and FcRs. LPS stimulation in vitro enhanced ICAM-1 and CD11b expression on neutrophils but reduced or did not affect the expression of CD11a, CD11c, CXCR2, BLT1, and FcRs (Supplemental Fig. S2), which suggests that LPS might be a major determinant for these receptor expression levels. Furthermore, isoflurane attenuated ICAM-1 expression on neutrophils stimulated with LPS in vitro (Fig. 2E). The up-regulation of CD11b expression was also attenuated by isoflurane in this setting (data not shown). Given the collected data altogether, we hypothesized that isoflurane would inhibit TLR4 signaling and tested this hypothesis in our subsequent investigation.

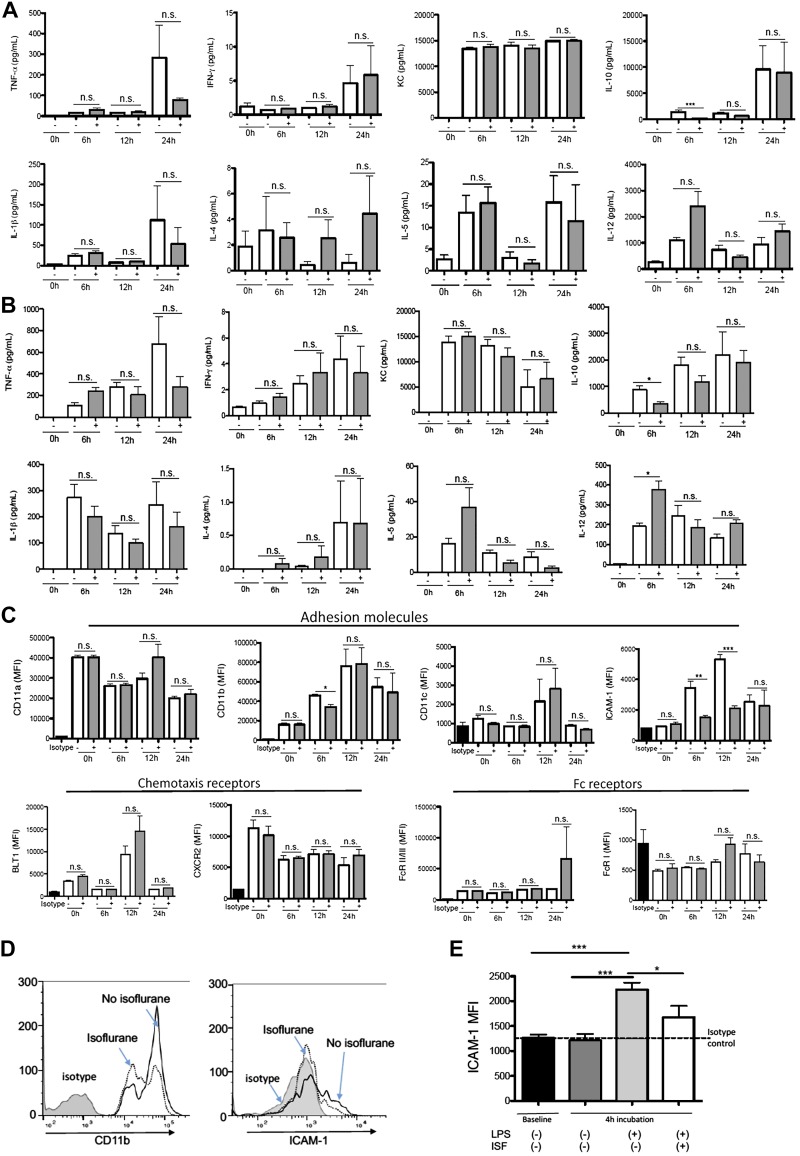

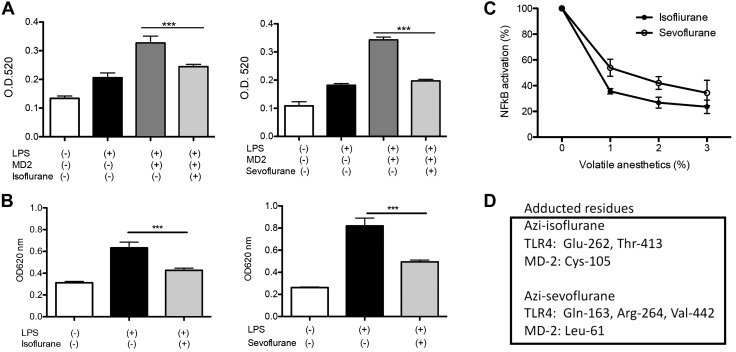

Isoflurane and sevoflurane attenuated the activation of TLR4 signaling

Activation of the TLR4 system by LPS leads into the activation of NF-κB. Thus, we tested our hypothesis using Raw-blue cells and THP-1–blue cells, in which activation of NF-κB by LPS stimulation was readily detected. To be consistent with the murine studies above, anesthetics were exposed for 6 h. Isoflurane exposure attenuated the NF-κB activation in both Raw-blue cells and THP-1 blue cells, supporting our hypothesis (Fig. 3A, B). Sevoflurane is another volatile anesthetic extensively used in clinical practice. Because both isoflurane and sevoflurane are classified as haloethers, we also tested sevoflurane. Sevoflurane attenuated the NF-κB activation as well (Fig. 3A, B). Both volatile anesthetics at clinically relevant concentrations inhibited TLR4 activation in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 3C), suggesting that TLR4 attenuation by these anesthetics would be clinically relevant.

Figure 3.

The effect of volatile anesthetics on LPS-mediated NF-kB activation and their binding to TLR4-MD-2 complex. The effect of anesthetics on NF-kB activation by LPS (1 µg/ml) was examined by incubating Raw-blue cells (A) and THP-1 blue cells (B) with isoflurane (1%) or sevoflurane (2%) for 6 h. MD-2 was added to Raw-blue cells. Data were shown as means ± sd of quadruplicates. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis. ***P < 0.001. C) The effect of isoflurane and sevoflurane on NF-kB activation by LPS (1 µg/ml) was tested in THP-1 blue cells at a range of concentrations. D) TLR4–MD-2 complex protein was photolabeled with azi-isoflurane or azi-sevoflurane and subjected to MS analysis. Adducted residues were shown. Specificity of interaction was confirmed by competing with isoflurane or sevoflurane. More detailed information of MS analysis is shown in Supplemental Fig. S1B, C. OD, optical density.

Isoflurane and sevoflurane directly bound to TLR4–MD-2 complex

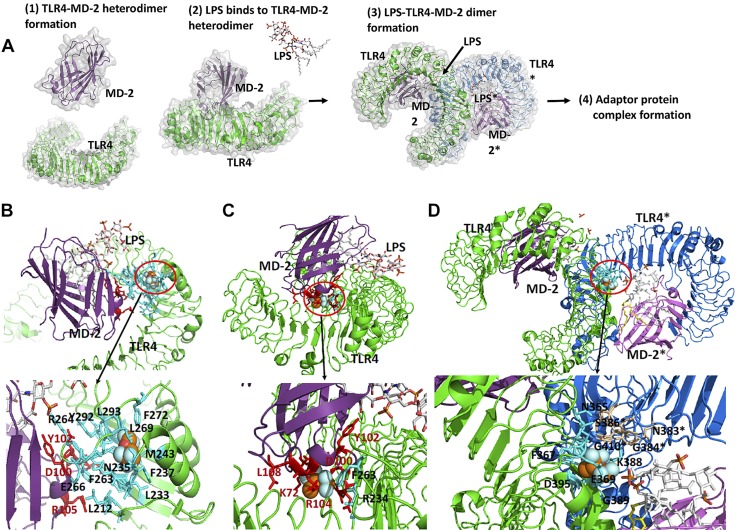

LPS activates TLR4 pathway as follows: First, adaptor protein MD-2 binds to TLR4 to form a heterodimer. Then, LPS binds to MD-2 via the lipophilic part of LPS (lipid A). Once LPS binds to the TLR4–MD-2 heterodimer, this complex binds to another LPS*–TLR4*–MD-2* complex (we differentiate them by using asterisks) to form a dimer. Dimerization recruits adaptor proteins intracellularly and activates the signaling cascade (Fig. 4A) (32, 33). Because isoflurane and sevoflurane primarily bind to cell surface receptors, such as GABA type A receptor, 2-pore-domain K+ channel, and NMDA receptor, to contribute to their anesthetic effect (34) or to CD11a to influence the immune system (12, 35, 36), we tested if these anesthetics would bind to the extracellular domain of TLR4–MD-2 complex to affect TLR4 signaling. The photolabeling experiment showed that isoflurane and sevoflurane bound to both MD-2 and the extracellular domain of TLR4 (Fig. 3D and Supplemental Fig. S1B, C). We performed rigid docking of isoflurane and sevoflurane on the TLR4–MD-2 complex. Isoflurane directly bound at the TLR4-MD-2 interface at 2 different sites (Fig. 4B, C) and the TLR4–MD-2* interface (Fig. 4D). The nearby amino acids (within 4 Å) from docked isoflurane were listed in Supplemental Table S1. The comparison of mouse and human MD-2 amino acids from residues 71 to 120 is shown in Supplemental Fig. S3A. Conserved Cys-95 and Cys-105 in MD-2 form an intramolecular disulfide bond to create a tertiary structure required for TLR4–MD-2 interface (37, 38). A number of residues between these cysteines are highly charged or hydrophilic and conserved between the 2 species. Asp-99, Asp-100, Asp-101, and Asp-102 in MD-2 are critical for the binding of MD-2 to the hydrophobic patch of TLR4 (37) (Supplemental Fig. S3B, C). Polar interactions between MD-2 and patch B were shown in Supplemental Fig. S3C. At the TLR4-TLR4* interface, Asn-365 and Ser-386* (or Asn-365* and Ser-386) form a hydrogen bond, and Val-411 and Val-411* form a hydrophobic interaction for dimerization. Presence of isoflurane could hinder these interactions.

Figure 4.

The binding site of isoflurane on TLR4–MD-2 complex. A). Scheme of TLR4 activation by LPS binding. Prior to LPS binding, MD-2 forms a stable heterodimer with the extracellular domain of TLR4 (1). LPS binding induces dimerization of TLR4–MD-2 complex (2). This dimerization leads into a significant conformational change in the cytoplasmic domain, providing a new scaffold that allows the recruitment of specific adaptor proteins to form a post receptor signaling complex (3). Interaction with the downstream adaptors leads to NF-κB–mediated signaling. B, C). Isoflurane binding site at TLR4–MD-2 interface. Docked isoflurane near TLR4–Glu-262 (B), docked isoflurane near MD-2–Cys-105 (C). Nearby amino acids from isoflurane are shown in red for MD-2 and cyan for TLR4. D) Isoflurane binding site at dimer interface (TLR4-TLR4* interface). Isoflurane was docked near TLR4-Thr-413 residue. Nearby amino acids from isoflurane are shown in blue for TLR4 and in wheat for TLR4*. Blow-out pictures of isoflurane binding sites are shown.

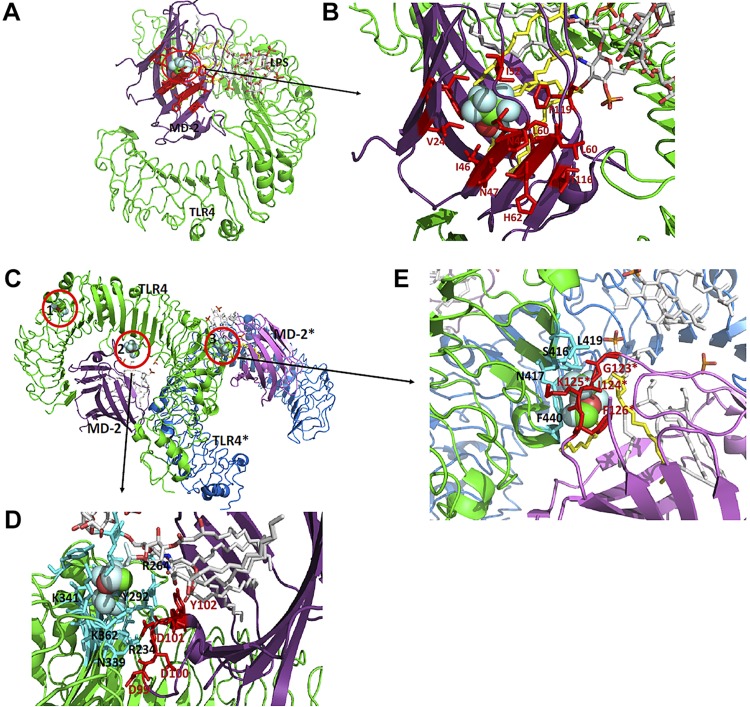

Sevoflurane bound at the MD-2–LPS interface (Fig. 5A, B), TLR4–MD-2 interface (Fig. 5C, D), and TLR4-TLR4* interface (Fig. 5C, E). The nearby amino acids (within 4 Å) from docked sevoflurane were listed in Supplemental Table S2. Sevoflurane interacted with Asp-99, Asp-100, Asp-101, and Tyr-102 in MD-2 at the TLR4–MD-2 interface (Fig. 5C, D). The importance of these residues for TLR4–MD-2 interaction was described above. Val-24, Ile-32, Ile-46, Leu-61, Phe-119, and Phe-151 in MD-2, all of which are located near sevoflurane, form hydrophobic interactions with lipid A in LPS (39) (Fig. 5A, B and Supplemental Fig. S4A, B), suggesting that sevoflurane could interfere with the interactions. Arg-264 and Asp-294 in TLR4 located near sevoflurane form charge interactions with LPS (39), with which sevoflurane could also interfere. Lastly, at the TLR4–MD-2* interface for dimerization, Ser-416 and Asn-417 in TLR4 form hydrogen bonds with Gly-123 and Lys-125 in MD-2*, respectively (Fig. 5E). Phe-440 in TLR4 also forms hydrophobic interactions with Ile-124* and Phe-126* in MD-2* and lipid A of LPS. We expect that sevoflurane would hinder these interactions. Sevoflurane also bound near Gln-163 (Fig. 5C and Supplemental Fig. S4C). However, this area is unlikely to contribute to LPS binding, given that it is far from the LPS binding site or the dimerization interface.

Figure 5.

Sevoflurane binding site on LPS–MD-2 complex. A, B) Sevoflurane binding site near MD-2–Leu-61 is shown. Nearby amino acids of MD-2 from sevoflurane are shown in red. Lipid A of LPS near sevoflurane is shown in yellow. C) Three sevoflurane binding sites (1–3) are shown. 1–3 are sevoflurane docked sites near TLR4–Gln-163, TLR4–Arg-264, and TLR4–Val-442, respectively. Blow-out images of sites 2 and 3 are shown in D and E, respectively. D) Binding site at TLR4-MD-2 interface. Nearby amino acids from sevoflurane are shown in cyan for TLR4 and in red for MD-2. E) Binding site at dimerization interface between TLR4 and MD-2*. Nearby amino acids from sevoflurane are shown in cyan for TLR4 and in red for MD-2*.

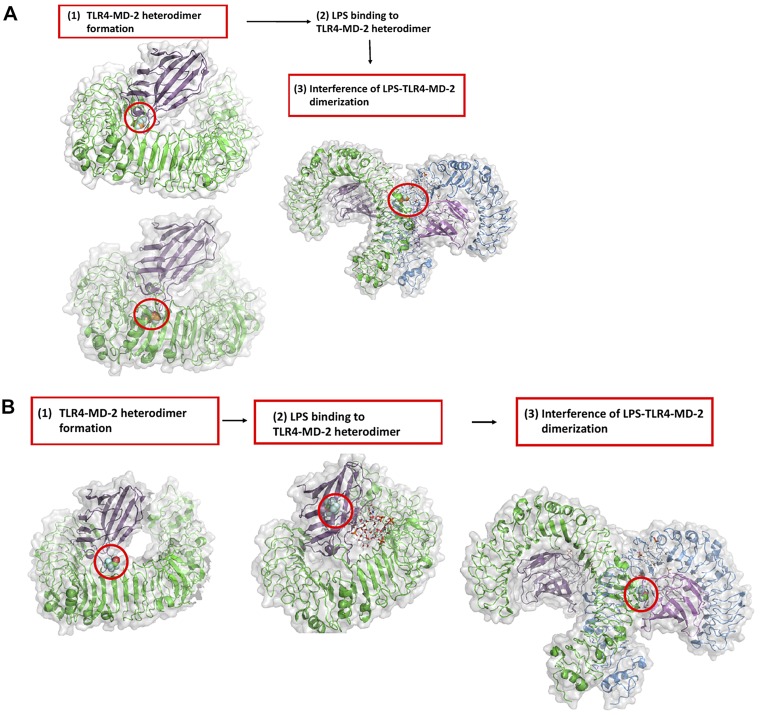

Taken together, isoflurane could interfere with the heterodimer formation of TLR4–MD-2 as well as the dimerization of the TLR4–MD-2–LPS complex (Fig. 6A). Sevoflurane could impair TLR4–MD-2 heterodimer formation, binding of LPS to MD-2, and dimerization of TLR4–MD-2–LPS (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

The role of volatile anesthetics in TLR4 system activation by LPS. A) Red box indicates the predicted steps that isoflurane could hinder. Red circle indicates isoflurane binding sites. B) Red box indicates the predicted steps that that sevoflurane could hinder. Red circle indicates sevoflurane-binding sites.

The effect of intravenous anesthetics on TLR4 activation

To examine whether the effect of anesthetics on TLR4 activation was specific to the 2 volatile anesthetics, we also tested commonly used intravenous anesthetics. Structures of anesthetics are shown in Supplemental Fig. S5A. All the intravenous drugs were tested within clinically relevant concentrations. Propofol attenuated TLR4 activation only at a high concentration (50 µM) (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Dexmedetomidine, etomidate, and ketamine did not affect TLR4 activation at clinically relevant concentrations.

DISCUSSION

Here we have shown that the commonly used volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane reduced the activation of TLR4 signaling by directly interfering with TLR4–MD-2–LPS complex formation. In contrast, the majority of intravenous anesthetics did not affect TLR4 signaling. Propofol attenuated TLR4 activation only at a very high concentration; nevertheless, this finding is clinically relevant because propofol is often used as an infusion at high doses, when its level can reach around 50 µM (40). Volatile anesthetics, the main components of general anesthesia, are considered to possess anti-inflammatory effects. It has been reported that the production of proinflammatory cytokines was attenuated in cell lines (41–44); in preclinical models, such as the LPS injury model; (45–51) and in patients (52, 53) under isoflurane and sevoflurane exposure. Our results are consistent with these previous investigations.

The role of TLR4 in sepsis has been extensively studied. LPS is the major component of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria and triggers systemic inflammation in gram-negative sepsis. TLR4 has been well validated as a target of gram-negative sepsis in animal models (54, 55). TLR4 Asp-299-Gly mutation, which depresses TLR4 signaling, is associated with increased susceptibility to gram-negative infection in patients (56). In gram-positive bacterial sepsis as well as fungal sepsis, the release of gut-derived LPS due to intestinal hypoperfusion was implicated to play a role in their disease processes (57, 58). Although TLR4 is the most well-recognized TLR, its function in sepsis may not be straightforward. TLR4 is expressed on immune cells as well as nonimmune cells. In myeloid cells, TLR4 is required for phagocytosis and bacterial clearance along with cytokine production (59). TLR4 on hepatocytes is in charge of LPS clearance, whereas on endothelial cells it contributes to sequestration of leukocytes (60). TLR4-deficient mice showed a better outcome in severe CLP sepsis, presumably because of reduced proinflammatory cytokine production (61), but showed worse survival in less severe CLP due to poor bacterial clearance (59). Similar to these conflicting data regarding the TLR4 role in preclinical sepsis, human sepsis trials showed inconsistent benefit of TLR4 inhibition. In a phase 2 clinical trial, treatment with a TLR4 inhibitor, eritoran, was associated with a lower mortality in patients with severe sepsis (62), but the phase 3 trial, disappointingly, did not show any survival benefit (63). Unfortunately, the phase 3 study did not include circulating LPS levels in the enrollment criteria, and the subgroup analysis showed that a large number of patients had low LPS levels. Furthermore, the mortality of the control group was much lower than expected in the study. Targeting TLR4 may be applied to a certain group of patients in the future based on these data. In recognizing the heterogeneity of sepsis, there will be significant room to improve the enrollment process of patients with sepsis for these type of studies (64). The Surviving Sepsis Campaign has issued the practice guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Identification and control of the source of infection were advocated as the mainstay of management strategy (65, 66), for which general anesthesia is often necessary. Volatile anesthetics are main components of general anesthesia. Volatile anesthetics have also been reported in the intensive care unit as alternative sedatives in Europe and Canada (67, 68). Our study demonstrated that volatile anesthetics inhibited TLR4 at clinically relevant concentrations. At a high concentration, propofol also attenuated TLR4 signaling. In this study we examined only the effect of volatile anesthetics on mediator profiles and neutrophil receptor expression in a preclinical sepsis in the context of TLR4 but did not delineate how this interaction would affect sepsis pathophysiology. Thus, further investigation is needed on this matter. As above, so far we do not have clear answer for the role of TLR4 inhibition in sepsis in general. Thus, we need to study the role of TLR4 in sepsis as well as the implication of TLR4 modulation by anesthetics.

Here we examined the effect of anesthetics in sepsis pathophysiology, although TLR4 also plays a significant role in sterile inflammation during surgery. Surgical trauma, hypoxia, and ischemia-reperfusion cause cell injury and tissue damage and release several DAMPs, including HMGB-1, a TLR4 ligand (69). For example, tissue ischemia-reperfusion injury is common in surgeries, such as vascular surgery, liver resection (Pringle maneuver), cardiac bypass surgery, and transplantation. The advantage of blocking TLR4 for posttransplantation graft well-being is well studied (70, 71). In line with our finding of TLR4-anesthetic interaction, the use of volatile anesthetics improved the graft survival in transplantation (72). An increase in HMGB-1 level has been shown in cardiac surgery (73). Meta-analysis showed that volatile anesthetics produced better outcome than intravenous anesthetics in cardiac surgery, which may also imply the interaction of volatile anesthetics on TLR4 (74). A recent large prospective study Mortality in Cardiac Surgery Randomized Controlled Trial of Volatile Anesthetics (MYRIAD), however, did not show any statistical difference in outcome of coronary artery bypass grafting surgery between groups anesthetized by volatile anesthesia and intravenous anesthesia (75). In the study, the mortality was lower in both groups, which was different from other prospective studies favoring volatile anesthetics (76, 77). In addition, propofol was the major drug given continuously in the intravenous anesthesia group (87.7%). Our study showed that propofol attenuated TLR4 at a high concentration, and it is possible that propofol infusion attained plasma concentrations that were high enough to block TLR4. Currently there is no method to reliably detect the activation via TLR4 in surgical patients and organ dysfunction, but our results suggest the importance of considering the immunologic aspect of anesthetics in some of the surgical cases.

In conclusion, we have shown that the volatile anesthetics isoflurane and sevoflurane attenuated the activation of TLR4 system by their direct interaction, but the majority of intravenous anesthetics did not. To potentially consider anesthetics as immunomodulators would be important, particularly when caring for patients with surgical diseases in which TLR4 is involved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Kyoko Yasuda (Juntendo University) and Dr. Hasan Badazada (University of Pennsylvania) for technical support. The authors also thank Dr. Yusuke Mitsui (Boston Children’s Hospital) for technical help. This work was supported, in part, by the Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CHMC) Anesthesia Foundation (to K.Y.), U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Grant R01GM118277 (to K.Y.). Research was also supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (MEXT/JSPS) Kakenhi Grants 15KK0320, 16K08596, and 19K07357 (to T.O.), 15H05904, 15H04708, and 18H02627 (to T.Y.) as well as NIH/NIGMS Grant P01GM55896 (to R.G.E.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- 5-LOX

5-lipoxygenase

- AA

arachidonic acid

- BLT1

leukotriene B(4) receptor

- CLP

cecal ligation and puncture

- CXCR2

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2

- DAMP

danger-associated molecular pattern

- DiHETE

dihydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- fMLP

N-formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine

- HMGB-1

high-mobility group box 1

- ICAM

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- LT

leukotriene

- MD-2

myeloid differentiation-2

- MS

mass spectrometry

- PG

prostaglandin

- PMA

phorbol myristate-acetate

- SEAP

secreted embryonic alkaline phosphate

- TAK-242

resatorvid

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T. Okuno designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; S. Koutsogiannaki designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; L. Hou designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; W. Bu designed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data; U. Ohto designed and performed the experiments; R. G. Eckenhoff wrote the manuscript; T. Yokomizo wrote the manuscript; and K. Yuki designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angus D. C., van der Poll T. (2013) Severe sepsis and septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 840–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward P. A. (2012) New approaches to the study of sepsis. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 1234–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaudhry H., Zhou J., Zhong Y., Ali M. M., McGuire F., Nagarkatti P. S., Nagarkatti M. (2013) Role of cytokines as a double-edged sword in sepsis. In Vivo 27, 669–684 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilkenny C., Browne W., Cuthill I. C., Emerson M., Altman D. G.; NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group (2010) Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 1577–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koutsogiannaki S., Schaefers M. M., Okuno T., Ohba M., Yokomizo T., Priebe G. P., DiNardo J. A., Sulpicio S. G., Yuki K. (2017) From the cover: prolonged exposure to volatile anesthetic isoflurane worsens the outcome of polymicrobial abdominal sepsis. Toxicol. Sci. 156, 402–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doerfler M. E., Danner R. L., Shelhamer J. H., Parrillo J. E. (1989) Bacterial lipopolysaccharides prime human neutrophils for enhanced production of leukotriene B4. J. Clin. Invest. 83, 970–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang H., Hussey S. E., Sanchez-Avila A., Tantiwong P., Musi N. (2013) Effect of lipopolysaccharide on inflammation and insulin action in human muscle. PLoS One 8, e63983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surette M. E., Palmantier R., Gosselin J., Borgeat P. (1993) Lipopolysaccharides prime whole human blood and isolated neutrophils for the increased synthesis of 5-lipoxygenase products by enhancing arachidonic acid availability: involvement of the CD14 antigen. J. Exp. Med. 178, 1347–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okuno T., Koutsogiannaki S., Ohba M., Chamberlain M., Bu W., Lin F. Y., Eckenhoff R. G., Yokomizo T., Yuki K. (2017) Intravenous anesthetic propofol binds to 5-lipoxygenase and attenuates leukotriene B4 production. FASEB J. 31, 1584–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki F., Koga T., Saeki K., Okuno T., Kazuno S., Fujimura T., Ohkawa Y., Yokomizo T. (2017) Biochemical and immunological characterization of a novel monoclonal antibody against mouse leukotriene B4 receptor 1. PLoS One 12, e0185133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandyopadhaya A., Tsurumi A., Rahme L. G. (2017) NF-κBp50 and HDAC1 interaction is implicated in the host tolerance to infection mediated by the bacterial quorum sensing signal 2-aminoacetophenone. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuki K., Bu W., Xi J., Sen M., Shimaoka M., Eckenhoff R. G. (2012) Isoflurane binds and stabilizes a closed conformation of the leukocyte function-associated antigen-1. FASEB J. 26, 4408–4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert N. C., Bartlett S. G., Waight M. T., Neau D. B., Boeglin W. E., Brash A. R., Newcomer M. E. (2011) The structure of human 5-lipoxygenase. Science 331, 217–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckenhoff R. G., Xi J., Shimaoka M., Bhattacharji A., Covarrubias M., Dailey W. P. (2010) Azi-isoflurane, a photolabel analog of the commonly used inhaled general anesthetic isoflurane. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 1, 139–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohto U., Fukase K., Miyake K., Shimizu T. (2012) Structural basis of species-specific endotoxin sensing by innate immune receptor TLR4/MD-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7421–7426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zha H., Matsunami E., Blazon-Brown N., Koutsogiannaki S., Hou L., Bu W., Babazada H., Odegard K. C., Liu R., Eckenhoff R. G., Yuki K. (2019) Volatile anesthetics affect macrophage phagocytosis. PLoS One 14, e0216163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson M. R., Blumer J. L. (2000) Prognostic markers in sepsis: the role of leukotrienes. Crit. Care Med. 28, 3762–3763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronoff D. M. (2012) Cyclooxygenase inhibition in sepsis: is there life after death? Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 696897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamim C. F., Canetti C., Cunha F. Q., Kunkel S. L., Peters-Golden M. (2005) Opposing and hierarchical roles of leukotrienes in local innate immune versus vascular responses in a model of sepsis. J. Immunol. 174, 1616–1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fink M. P. (2001) Prostaglandins and sepsis: still a fascinating topic despite almost 40 years of research. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 281, L534–L536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harizi H., Gualde N. (2005) The impact of eicosanoids on the crosstalk between innate and adaptive immunity: the key roles of dendritic cells. Tissue Antigens 65, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haeggström J. Z. (2018) Leukotriene biosynthetic enzymes as therapeutic targets. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 2680–2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith W. L., Malkowski M. G. (2019) Interactions of fatty acids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and coxibs with the catalytic and allosteric subunits of cyclooxygenases-1 and -2. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 1697–1705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dillon S., Agrawal S., Banerjee K., Letterio J., Denning T. L., Oswald-Richter K., Kasprowicz D. J., Kellar K., Pare J., van Dyke T., Ziegler S., Unutmaz D., Pulendran B. (2006) Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 916–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyde S. R., Stith R. D., McCallum R. E. (1990) Mortality and bacteriology of sepsis following cecal ligation and puncture in aged mice. Infect. Immun. 58, 619–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiffmann E., Corcoran B. A., Wahl S. M. (1975) N-formylmethionyl peptides as chemoattractants for leucocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 72, 1059–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorward D. A., Lucas C. D., Chapman G. B., Haslett C., Dhaliwal K., Rossi A. G. (2015) The role of formylated peptides and formyl peptide receptor 1 in governing neutrophil function during acute inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 185, 1172–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X., Yan W., Zheng H., Du Q., Zhang L., Ban Y., Li N., Wei F. (2015) Regulation of IL-10 and IL-12 production and function in macrophages and dendritic cells. F1000 Res. 4, F1000 Faculty Rev-1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kasten K. R., Muenzer J. T., Caldwell C. C. (2010) Neutrophils are significant producers of IL-10 during sepsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 393, 28–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewkowicz N., Mycko M. P., Przygodzka P., Ćwiklińska H., Cichalewska M., Matysiak M., Selmaj K., Lewkowicz P. (2016) Induction of human IL-10-producing neutrophils by LPS-stimulated Treg cells and IL-10. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 364–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi J., Zhao Y., Wang Y., Gao W., Ding J., Li P., Hu L., Shao F. (2014) Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature 514, 187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park B. S., Lee J. O. (2013) Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp. Mol. Med. 45, e66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Núñez Miguel R., Wong J., Westoll J. F., Brooks H. J., O’Neill L. A., Gay N. J., Bryant C. E., Monie T. P. (2007) A dimer of the toll-like receptor 4 cytoplasmic domain provides a specific scaffold for the recruitment of signalling adaptor proteins. PLoS One 2, e788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franks N. P. (2008) General anaesthesia: from molecular targets to neuronal pathways of sleep and arousal. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 370–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuki K., Astrof N. S., Bracken C., Yoo R., Silkworth W., Soriano S. G., Shimaoka M. (2008) The volatile anesthetic isoflurane perturbs conformational activation of integrin LFA-1 by binding to the allosteric regulatory cavity. FASEB J. 22, 4109–4116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuki K., Astrof N. S., Bracken C., Soriano S. G., Shimaoka M. (2010) Sevoflurane binds and allosterically blocks integrin lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1. Anesthesiology 113, 600–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Re F., Strominger J. L. (2003) Separate functional domains of human MD-2 mediate toll-like receptor 4-binding and lipopolysaccharide responsiveness. J. Immunol. 171, 5272–5276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim H. M., Park B. S., Kim J. I., Kim S. E., Lee J., Oh S. C., Enkhbayar P., Matsushima N., Lee H., Yoo O. J., Lee J. O. (2007) Crystal structure of the TLR4-MD-2 complex with bound endotoxin antagonist Eritoran. Cell 130, 906–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park B. S., Song D. H., Kim H. M., Choi B. S., Lee H., Lee J. O. (2009) The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature 458, 1191–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuki K., Soriano S. G., Shimaoka M. (2011) Sedative drug modulates T-cell and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 function. Anesth. Analg. 112, 830–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H., Wang L., Li N. L., Li J. T., Yu F., Zhao Y. L., Wang L., Yi J., Wang L., Bian J. F., Chen J. H., Yuan S. F., Wang T., Lv Y. G., Liu N. N., Zhu X. S., Ling R., Yun J. (2014) Subanesthetic isoflurane reduces zymosan-induced inflammation in murine Kupffer cells by inhibiting ROS-activated p38 MAPK/NF-κB signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 851692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez-González R., Baluja A., Veiras Del Río S., Rodríguez A., Rodríguez J., Taboada M., Brea D., Álvarez J. (2013) Effects of sevoflurane postconditioning on cell death, inflammation and TLR expression in human endothelial cells exposed to LPS. J. Transl. Med. 11, 87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yue T., Roth Z’graggen B., Blumenthal S., Neff S. B., Reyes L., Booy C., Steurer M., Spahn D. R., Neff T. A., Schmid E. R., Beck-Schimmer B. (2008) Postconditioning with a volatile anaesthetic in alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Eur. Respir. J. 31, 118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boost K. A., Leipold T., Scheiermann P., Hoegl S., Sadik C. D., Hofstetter C., Zwissler B. (2009) Sevoflurane and isoflurane decrease TNF-alpha-induced gene expression in human monocytic THP-1 cells: potential role of intracellular IkappaBalpha regulation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 23, 665–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bedirli N., Bagriacik E. U., Emmez H., Yilmaz G., Unal Y., Ozkose Z. (2012) Sevoflurane and isoflurane preconditioning provides neuroprotection by inhibition of apoptosis-related mRNA expression in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 24, 336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bedirli N., Demirtas C. Y., Akkaya T., Salman B., Alper M., Bedirli A., Pasaoglu H. (2012) Volatile anesthetic preconditioning attenuated sepsis induced lung inflammation. J. Surg. Res. 178, e17–e23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herrmann I. K., Castellon M., Schwartz D. E., Hasler M., Urner M., Hu G., Minshall R. D., Beck-Schimmer B. (2013) Volatile anesthetics improve survival after cecal ligation and puncture. Anesthesiology 119, 901–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hofstetter C., Boost K. A., Flondor M., Basagan-Mogol E., Betz C., Homann M., Muhl H., Pfeilschifter J., Zwissler B. (2007) Anti-inflammatory effects of sevoflurane and mild hypothermia in endotoxemic rats. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 51, 893–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J. T., Wang H., Li W., Wang L. F., Hou L. C., Mu J. L., Liu X., Chen H. J., Xie K. L., Li N. L., Gao C. F. (2013) Anesthetic isoflurane posttreatment attenuates experimental lung injury by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 108928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plachinta R. V., Hayes J. K., Cerilli L. A., Rich G. F. (2003) Isoflurane pretreatment inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in rats. Anesthesiology 98, 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mu J., Xie K., Hou L., Peng D., Shang L., Ji G., Li J., Lu Y., Xiong L. (2010) Subanesthetic dose of isoflurane protects against zymosan-induced generalized inflammation and its associated acute lung injury in mice. Shock 34, 183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schilling T., Kozian A., Senturk M., Huth C., Reinhold A., Hedenstierna G., Hachenberg T. (2011) Effects of volatile and intravenous anesthesia on the alveolar and systemic inflammatory response in thoracic surgical patients. Anesthesiology 115, 65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Conno E., Steurer M. P., Wittlinger M., Zalunardo M. P., Weder W., Schneiter D., Schimmer R. C., Klaghofer R., Neff T. A., Schmid E. R., Spahn D. R., Z’graggen B. R., Urner M., Beck-Schimmer B. (2009) Anesthetic-induced improvement of the inflammatory response to one-lung ventilation. Anesthesiology 110, 1316–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Sanjo H., Ogawa T., Takeda Y., Takeda K., Akira S. (1999) Cutting edge: toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J. Immunol. 162, 3749–3752 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roger T., Froidevaux C., Le Roy D., Reymond M. K., Chanson A. L., Mauri D., Burns K., Riederer B. M., Akira S., Calandra T. (2009) Protection from lethal gram-negative bacterial sepsis by targeting toll-like receptor 4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2348–2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorenz E., Hallman M., Marttila R., Haataja R., Schwartz D. A. (2002) Association between the Asp299Gly polymorphisms in the toll-like receptor 4 and premature births in the Finnish population. Pediatr. Res. 52, 373–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Opal S. M., Scannon P. J., Vincent J. L., White M., Carroll S. F., Palardy J. E., Parejo N. A., Pribble J. P., Lemke J. H. (1999) Relationship between plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS-binding protein in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. J. Infect. Dis. 180, 1584–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marshall J. C., Foster D., Vincent J. L., Cook D. J., Cohen J., Dellinger R. P., Opal S., Abraham E., Brett S. J., Smith T., Mehta S., Derzko A., Romaschin A.; MEDIC study (2004) Diagnostic and prognostic implications of endotoxemia in critical illness: results of the MEDIC study. J. Infect. Dis. 190, 527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deng M., Scott M. J., Loughran P., Gibson G., Sodhi C., Watkins S., Hackam D., Billiar T. R. (2013) Lipopolysaccharide clearance, bacterial clearance, and systemic inflammatory responses are regulated by cell type-specific functions of TLR4 during sepsis. J. Immunol. 190, 5152–5160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andonegui G., Bonder C. S., Green F., Mullaly S. C., Zbytnuik L., Raharjo E., Kubes P. (2003) Endothelium-derived toll-like receptor-4 is the key molecule in LPS-induced neutrophil sequestration into lungs. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1011–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alves-Filho J. C., de Freitas A., Russo M., Cunha F. Q. (2006) Toll-like receptor 4 signaling leads to neutrophil migration impairment in polymicrobial sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 34, 461–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tidswell M., Tillis W., Larosa S. P., Lynn M., Wittek A. E., Kao R., Wheeler J., Gogate J., Opal S. M.; Eritoran Sepsis Study Group (2010) Phase 2 trial of eritoran tetrasodium (E5564), a toll-like receptor 4 antagonist, in patients with severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 38, 72–83; erratum: 1925–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Opal S. M., Laterre P. F., Francois B., LaRosa S. P., Angus D. C., Mira J. P., Wittebole X., Dugernier T., Perrotin D., Tidswell M., Jauregui L., Krell K., Pachl J., Takahashi T., Peckelsen C., Cordasco E., Chang C. S., Oeyen S., Aikawa N., Maruyama T., Schein R., Kalil A. C., Van Nuffelen M., Lynn M., Rossignol D. P., Gogate J., Roberts M. B., Wheeler J. L., Vincent J. L.; ACCESS Study Group (2013) Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. JAMA 309, 1154–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tse M. T. (2013) Trial watch: sepsis study failure highlights need for trial design rethink. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dellinger R. P., Levy M. M., Rhodes A., Annane D., Gerlach H., Opal S. M., Sevransky J. E., Sprung C. L., Douglas I. S., Jaeschke R., Osborn T. M., Nunnally M. E., Townsend S. R., Reinhart K., Kleinpell R. M., Angus D. C., Deutschman C. S., Machado F. R., Rubenfeld G. D., Webb S. A., Beale R. J., Vincent J. L., Moreno R.; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup (2013) Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit. Care Med. 41, 580–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schorr C. A., Dellinger R. P. (2014) The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: past, present and future. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 192–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jerath A., Panckhurst J., Parotto M., Lightfoot N., Wasowicz M., Ferguson N. D., Steel A., Beattie W. S. (2017) Safety and efficacy of volatile anesthetic agents compared with standard intravenous midazolam/propofol sedation in ventilated critical care patients: a meta-analysis and systematic review of prospective trials. Anesth. Analg. 124, 1190–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.L’her E., Dy L., Pili R., Prat G., Tonnelier J. M., Lefevre M., Renault A., Boles J. M. (2008) Feasibility and potential cost/benefit of routine isoflurane sedation using an anesthetic-conserving device: a prospective observational study. Respir. Care 53, 1295–1303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Molteni M., Gemma S., Rossetti C. (2016) The role of toll-like receptor 4 in infectious and noninfectious inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 6978936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krüger B., Krick S., Dhillon N., Lerner S. M., Ames S., Bromberg J. S., Lin M., Walsh L., Vella J., Fischereder M., Krämer B. K., Colvin R. B., Heeger P. S., Murphy B. T., Schröppel B. (2009) Donor toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3390–3395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leventhal J. S., Schröppel B. (2012) Toll-like receptors in transplantation: sensing and reacting to injury. Kidney Int. 81, 826–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Minou A. F., Dzyadzko A. M., Shcherba A. E., Rummo O. O. (2012) The influence of pharmacological preconditioning with sevoflurane on incidence of early allograft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients. Anesthesiol. Res. Pract. 2012, 930487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haque A., Kunimoto F., Narahara H., Okawa M., Hinohara H., Kurabayashi M., Saito S. (2011) High mobility group box 1 levels in on and off-pump cardiac surgery patients. Int. Heart J. 52, 170–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uhlig C., Bluth T., Schwarz K., Deckert S., Heinrich L., De Hert S., Landoni G., Serpa Neto A., Schultz M. J., Pelosi P., Schmitt J., Gama de Abreu M. (2016) Effects of volatile anesthetics on mortality and postoperative pulmonary and other complications in patients undergoing surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology 124, 1230–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Landoni G., Lomivorotov V. V., Nigro Neto C., Monaco F., Pasyuga V. V., Bradic N., Lembo R., Gazivoda G., Likhvantsev V. V., Lei C., Lozovskiy A., Di Tomasso N., Bukamal N. A. R., Silva F. S., Bautin A. E., Ma J., Crivellari M., Farag A. M. G. A., Uvaliev N. S., Carollo C., Pieri M., Kunstýř J., Wang C. Y., Belletti A., Hajjar L. A., Grigoryev E. V., Agrò F. E., Riha H., El-Tahan M. R., Scandroglio A. M., Elnakera A. M., Baiocchi M., Navalesi P., Shmyrev V. A., Severi L., Hegazy M. A., Crescenzi G., Ponomarev D. N., Brazzi L., Arnoni R., Tarasov D. G., Jovic M., Calabrò M. G., Bove T., Bellomo R., Zangrillo A.; MYRIAD Study Group (2019) Volatile anesthetics versus total intravenous anesthesia for cardiac surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1214–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Hert S., Vlasselaers D., Barbé R., Ory J. P., Dekegel D., Donnadonni R., Demeere J. L., Mulier J., Wouters P. (2009) A comparison of volatile and non volatile agents for cardioprotection during on-pump coronary surgery. Anaesthesia 64, 953–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Likhvantsev V. V., Landoni G., Levikov D. I., Grebenchikov O. A., Skripkin Y. V., Cherpakov R. A. (2016) Sevoflurane versus total intravenous anesthesia for isolated coronary artery bypass surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass: a randomized trial. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 30, 1221–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.