Abstract

Objective

To examine the correlation between dietary selenium (Se) intake and the prevalence of osteoporosis (OP) in the general middle-aged and older population in China.

Methods

Data for analyses were collected from a population based cross-sectional study performed at the Xiangya Hospital Health Management Centre. Dietary Se intake was evaluated using a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire. OP was diagnosed on the basis of bone mineral density scans using a compact radiographic absorptiometry system. The correlation between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP was primarily examined by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

This cross-sectional study included a total of 6267 subjects (mean age: 52.2 ± 7.4 years; 42% women), and the prevalence of OP among the included subjects was 9.6% (2.3% in men and 19.7% in women). Compared with the lowest quartile, the energy intake, age, gender and body mass index (BMI)-adjusted odds ratios of OP were 0.72 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.55–0.94), 0.72 (95% CI 0.51–1.01) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.31–0.73) for the second, third and fourth quartiles of dietary Se intake, respectively (P for trend = 0.001). The results remained consistent in male and female subjects. Adjustment for additional potential confounders (i.e., smoking status, drinking status, physical activity level, nutritional supplements, diabetes, hypertension, fibre intake, and calcium intake) did not cause substantial changes to the results.

Conclusions

In the middle-aged and older humans, participants with lower levels of dietary Se intake have a higher prevalence of OP in a dose-response manner.

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is a frequently-seen skeletal disease featured typically by micro-architectural deterioration and low bone mineral density (BMD), which are highly associated with the increase of bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture [1]. Nowadays, OP has been widely deemed a significant contributor to the social healthcare burden due to its high mortality, morbidity, and treatment expenses [2]. According to the data reported by five countries in Europe (i.e., the UK, France, Germany, Spain and Italy), the prevalence of OP in the male and female population ranged 7–8% and 30–33%, respectively [3]. In mainland China, a multi-center study yielded that the prevalence of OP was 6.46% in men and 29.13% in women who aged over 50 years [4]. The etiology of OP is multifactorial, among the already known etiologies, dietary factors are believed to have a great importance [5]. However, most of the existing studies have a focus on calcium intake [6–8], while other dietary factors, especially trace elements, which may also play a significant role in preventing OP, are seldom investigated [9].

Selenium (Se), a trace mineral element essential for human being, can regulate cellular processes by behaving as a component of Se-dependent antioxidant enzyme [10–12] that eliminates intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) [12, 13]. Therefore, deficiency in Se can lead to an increase in ROS levels, which has been considered as the proximal culprit in the pathogenesis of OP [14]. There were several human studies in the existing literature that investigated the association between Se status and BMD or osteoporotic hip fracture, a catastrophic outcome of OP, but the results are inconclusive. For example, with a sample of female participants aged 50–79 years, an earlier cross-sectional study suggested that dietary Se intake had no association with BMD [15]. However, the authors acknowledged a potential inclusion bias – most of their participants were women with normal BMD, which means the correlation between dietary Se intake and OP patients with low BMD, if any, might be missed [15]. In addition, another two studies reported a negative correlation between dietary Se intake and osteoporotic hip fracture [16, 17]. However, BMD was not directly measured in these studies [16, 17]. Meanwhile, two other studies indicated that plasma Se concentration is positively associated with BMD in healthy aging European men [18], also in healthy euthyroid postmenopausal women [19]. Another research indicated that serum Se deficiency was accompanied by ALOX12 variation, contributing to the development of OP [20]. But these studies concentrate on Se concentration in blood rather than dietary Se intake.

To fill in this knowledge gap, a large-sample cross-sectional study was conducted to elaborate the association between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population.

Methods

Study population

Chinese subjects who received health screening at the Department of Health Examination Centre of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (located in Changsha of Hunan, China) within the time window from October 2013 to December 2015, were recruited for the present research. The study design remained consistent with some of our previously-published works [21–25]. To acquire the demographic information and health-related habits, registered nurses were engaged to interview all the participants during the physical examination by referring to a standard questionnaire.

Prior to research implementation, the study protocol had been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees on Research of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (No. 201312459), and informed consent had been collected from all the participants after explaining the research content in verbal and written. For sample screening, the following inclusion criteria applied: (1) ≥40 years old; (2) the data of average consumption of specific food items and drinks during the last 12 months could be retrieved from the semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (SFFQ); (3) basic characteristics such as age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol drinking status, waist circumference, exercise intensity, and history of hypertension/diabetes were available; and (4) participants were not diagnosed with any other musculoskeletal disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, osteochondroma, and other bone tumors).

A total of 31,542 participants received routine physical examinations at aforementioned study center from October 2013 to December 2015, and 6471 of them were qualified by the inclusion criteria. Then, 200 participants were excluded due to the existence of other musculoskeletal disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, osteochondroma, and other bone tumors), and four participants were excluded due to the unavailability of dietary questionnaire data. Eventually, 6267 participants were included for final analysis.

Dietary assessment

A validated SFFQ which was adopted in some of our previously-published studies [23, 26] was referred to for the assessment of dietary intake. The SFFQ survey was conducted twice for all participants, with at least a one-week interval in between, to comparatively evaluate their reproducibility based on the calculation of dietary Se intake. The correlation coefficient was 0.64 (P < 0.001). Then, a subsample (n = 173) was created by random selection from the study cohort, and was used to validate the SFFQ by comparing the result derived from SFFQ with that obtained from the 24-h dietary recall method over the same sample. The correlation coefficient for dietary Se intake was 0.47 (P < 0.001). The results of validation showed that the overall performance of SFFQ in the present study was consistent with previous works [27, 28].

In this SFFQ, a total of 63 food items were included based on the general dietary habit in Hunan province of China, with the intention to understand the participants’ frequency of consumption for each food item (i.e., never, once per month, 2–3 times per month, 1–3 times per week, 4–5 times per week, once per day, twice per day, or > twice per day) and average amount of consumption in each time (< 100 g, 100–200 g, 201–300 g, 301–400 g, 401–500 g, or > 500 g) during the previous year. The SFFQ consisted of 63 commonly consumed local food items, including the main sources of dietary Se, which included meat, fish, eggs, bread, cereals and milk [29]. Also included almost Se-free food sources, such as fruits and vegetables [30]. To facilitate the participants in making accurate choices, pictures of food items showing the standard weight were provided alongside the SFFQ. The compositions of macro nutrients and micro nutrients were calculated based on the Chinese Food Composition Table for all the included food items.

Assessment of other exposures

The BMI was calculated based on the measurement of weight and height for each participant. The average frequency of physical activity (never, 1–2 times per week, 3–4 times per week or ≥ 5 times per week), average duration of each physical activity (< 30 min, 30–60 min, 1–2 h, or > 2 h), as well as the smoking and drinking status were all inquired and recorded during the interview. The fasting blood glucose (FBG) was detected by the Beckman Coulter AU 5800 (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, US), and a participant would be diagnosed of diabetes if his/her FBG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or if he/she was undergoing any anti-diabetic treatment. The blood pressure was measured by an electronic sphygmomanometer, and a participant would be diagnosed of hypertension if his/her systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or if he/she was using any anti-hypertensive drug.

BMD assessment

The BMD was detected by a compact radiographic absorptiometry (RA) system called Alara MetriScan (Alara Inc., Fremont, CA, US), at the middle phalanges of the second to fourth fingers on the non-dominant hand. To guarantee the accuracy of measurement, all participants were requested to take off accessories from the hand before testing. The RA system would capture a high-resolution radio graphic image at an intensity expressed in arbitrary units (mineral mass/area) based on the mean value. Then, by referencing to a manufacturer-provided database, the T-score, which was used to compare the measured BMD of a participant with the average BMD of young, healthy subjects of the same gender, would be computed [31–33]. The peripheral densitometry system used in this study was characterized by high portability, low cost, and low X-ray dose (< 0.02 μSV/test). Based on the collected measurements, the participants were classified in accordance with the recommendations specified by the World Health Organization. Specifically, the BMD level within 1 standard deviation (SD) vs. a young, healthy adult is regarded as normal; the BMD level ranged from 1 to 2.5 SD below a young, healthy adult is regarded as osteopenia; and the BMD level equal to or 2.5 SD below a young, healthy adult is regarded as OP [34]. Participants classified as normal and osteopenia were both regarded as non-OP.

Statistical analysis

All the continuous data was presented as means ± standard deviations, and the differences were assessed by the one-way analysis of variance (data of normal distribution) or the Kruskal-Wallis H test (data of non-normal distributions). All the categorical data was presented as percentages, and the differences were assessed by the Pearson Chi-square test. Dietary Se intake was categorized, on the basis of quartile distribution of the study population, into four categories: ≤29.2 μg/day, 29.3–39.8 μg/day, 39.9–51.8 μg/day, and ≥ 51.9 μg/day. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for all the quartiles of Se intake, and the lowest quartile was considered as the reference. A total of three models were created for multivariable analysis: the first model targeted on the dietary energy intake (quartiles); the second model further incorporated the factors of age (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ≥ 70 years), gender (male, female) and BMI (< 28, ≥ 28 kg/m2) on the basis of the first model; and the third model further incorporated the factors of smoking status (yes/no), alcohol drinking status (yes/no), physical activity intensity (continuous), nutritional supplements (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), dietary calcium intake (quartiles) and dietary fibre intake (quartiles) on the basis of the second model. Then, subgroup analysis of gender was performed. Subsequently, restricted cubic splines regression, with three knots (29.2 μg/day, 39.8 μg/day, 51.8 μg/day) defined by the quartile distribution of dietary Se was conducted to evaluate the dose-response relationship between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP [35, 36]. Statistical software SPSS 21.0 and STATA 11.0 were used for data analysis. P < 0.05 was equivalent to statistically significant.

Results

A total of 6267 participants (3627 males, 2640 females) aged 40 years or older (average 52.2 ± 7.4 years old) entered the present study. The prevalence of OP in the entire group was 9.6% (2.3% in men and 19.7% in women). The essential features of the study sample on the basis of the OP status are shown in Table 1. We have observed significant differences between OP and non-OP subjects with regard to age, gender, smoking and drinking status, BMI, hypertension, physical activity level, nutrients supplementation, dietary calcium intake, dietary fibre intake, dietary energy intake, and dietary Se intake.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the OP and non-OP population (n = 6267)

| Basic characteristics | OP status | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OP population | Non-OP population | ||

| Number | 602 | 5665 | – |

| Age (years) | 59.0 ± 6.9 | 51.5 ± 7.1 | < 0.001 |

| 40–49 (%) | 9.1 | 43.7 | |

| 50–59 (%) | 42.0 | 41.3 | |

| 60–69 (%) | 42.9 | 13.4 | |

| ≥ 70 (%) | 6.0 | 1.6 | |

| Gender (female, %) | 86.2 | 37.4 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking (%) | 8.8 | 26.6 | < 0.001 |

| Drinking (%) | 18.3 | 42.8 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.2 ± 3.0 | 24.6 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2, %) | 6.6 | 14.0 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 12.1 | 11.2 | 0.499 |

| Hypertension (%) | 38.2 | 31.3 | 0.001 |

| Activity level (h/week) | 2.7 ± 3.7 | 2.1 ± 3.3 | 0.007 |

| Nutritional supplements (%) | 47.3 | 34.4 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary calcium intake (mg/day) | 443.4 ± 318.0 | 486.4 ± 325.0 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary fibre intake (g/day) | 15.8 ± 12.4 | 18.0 ± 14.9 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary energy intake (Kcal/day) | 1481.7 ± 776.0 | 1638.2 ± 750.7 | < 0.001 |

| Dietary selenium intake (μg/day) | 39.1 ± 31.1 | 44.0 ± 23.3 | < 0.001 |

OP osteoporosis, BMI body mass index

P values are for the test of difference between the OP population and non-OP population using one-way analysis of variance in case of normally distributed continuous variables, Kruskal-Wallis H test in case of non-normally distributed continuous variables and Pearson Chi-square test in case of categorical variables

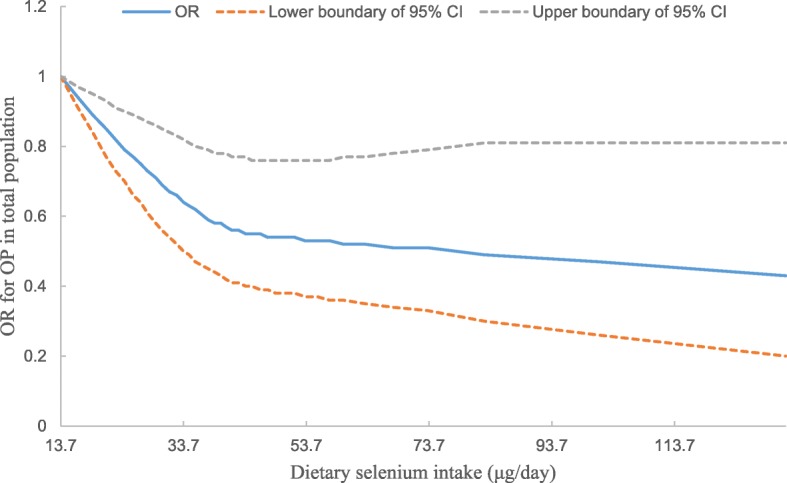

The correlation between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP is demonstrated in Table 2. As illustrated in Model 1, after adjustment for energy intake, the ORs (95% CIs) of OP were 0.78 (95% CI: 0.61–0.99), 0.76 (95% CI: 0.56–1.01), 0.51 (95% CI: 0.35–0.75) for the second, third, and fourth dietary Se quartiles, respectively (P for trend = 0.001), in comparison with the lowest quartile. After further adjustment for age, gender and BMI in Model 2, the correlation between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP remained negative (P for trend = 0.001). The multivariable-adjusted ORs (95% CIs) for the prevalence of OP in the second, third and fourth dietary Se quartiles were 0.72 (95% CI: 0.55–0.95), 0.73 (95% CI: 0.51–1.03), 0.48 (95% CI: 0.31–0.75), respectively (P for trend = 0.002). Similar results were obtained separately for male and female subjects. Furthermore, as can be seen from Fig. 1, a negative correlation between dietary Se intake and the OR for OP was observed, with a dose-response relationship.

Table 2.

Association between dietary selenium intake and the prevalence of OP (n = 6267)

| Quartiles of dietary selenium intake (μg/day) | P for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (≤ 29.2) | Q2 (29.3–39.8) | Q3 (39.9–51.8) | Q4 (≥ 51.9) | ||

| Median selenium intake (μg/day) | 22.8 | 34.8 | 45.0 | 63.4 | – |

| Total | |||||

| Model 1 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.78 (0.61, 0.99) | 0.76 (0.56, 1.01) | 0.51 (0.35, 0.75) | 0.001 |

| Model 2 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.72 (0.55, 0.94) | 0.72 (0.51, 1.01) | 0.47 (0.31, 0.73) | 0.001 |

| Model 3 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.72 (0.55, 0.95) | 0.73 (0.51, 1.03) | 0.48 (0.31, 0.75) | 0.002 |

| Male | |||||

| Model 1 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.33 (0.16, 0.66) | 0.38 (0.19, 0.77) | 0.20 (0.08, 0.46) | 0.001 |

| Model 2 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.33 (0.16, 0.68) | 0.41 (0.20, 0.83) | 0.22 (0.09, 0.52) | 0.003 |

| Model 3 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.35 (0.17, 0.71) | 0.42 (0.20, 0.89) | 0.25 (0.10, 0.61) | 0.010 |

| Female | |||||

| Model 1 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.77 (0.59, 1.00) | 0.74 (0.52, 1.05) | 0.53 (0.34, 0.84) | 0.008 |

| Model 2 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.83 (0.62, 1.11) | 0.80 (0.54, 1.19) | 0.54 (0.33, 0.90) | 0.018 |

| Model 3 (95% CI) | 1.00 (Ref.) | 0.82 (0.60, 1.10) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.19) | 0.53 (0.32, 0.89) | 0.018 |

Ref. reference group, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Model 1 included dietary energy intake (quartiles)

Model 2 included age (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, ≥ 70 years), gender (male, female), BMI (< 28, ≥ 28 kg/m2), and energy intake (quartiles) (age, BMI and energy intake for the gender subgroup)

Model 3 added smoking status (yes/no), drinking status (yes/no), activity level (continuous data), nutritional supplements (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), dietary fibre intake (quartiles), and dietary calcium intake (quartiles) on the basis of model 2

Fig. 1.

Dose-response relationship between dietary selenium intake and the odds ratio for osteoporosis in the total population (n = 6267). OP osteoporosis, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio

Discussion

In the present study, a negative association between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP was identified independent of major confounders. This correlation remained consistent across male and female subjects, and exhibited a dose-response relationship manner. The findings of our study may give a hint of the pathogenesis of OP, and future studies of dietary intake, including Se supplementary intake, on the risk of OP are warranted.

Several observational research works have investigated the association between dietary Se intake and BMD or osteoporotic hip fracture. For example, an earlier cross-sectional study by Wolf et al. indicated that dietary Se intake was not correlated with BMD [15]. Se intake of participants enrolled in this study was 94.1 μg/day, and calcium intake of participants enrolled in this study was 900.1 mg/day. Pedrera-Zamorano et al. [37] observed that elevated Se intake negatively affected BMD in postmenopausal female subjects aged over 51, but only if their calcium intake was below 800 mg/day at the same time. As long as the calcium intake exceeded 800 mg/day, Se intake no longer appeared to affect BMD. Besides, Se intake in this study was 95.5 μg/day. Considering that Se intake of participants enrolled in both studies were beyond Se intake in our population (43.5 μg/day), the variation in Se intake in both the studies might be insufficient to reveal any association. There were three studies [16, 17, 38] investigating the association between dietary Se intake and the risk of osteoporotic hip fracture, but none of them concerned the value of BMD, hence subjects of fracture which were probably not caused by OP might also be enrolled into the studies. Besides, two of these three studies [16, 38] focused on the smoking population, while our study concentrates on the general population. Given that smoking is not the only cause of oxidative stress, which has been considered as the critical mechanism of OP [14], the association between dietary Se intake and osteoporotic hip fracture in the general population is still inconclusive.

Several mechanisms linking Se with OP have been postulated. First, it has been reported that interleukin-6 (IL-6) and some other cytokines play a significant role in the pathogenesis of OP [39]. Se can exert anti-inflammatory actions, mediated in part by the inhibitory effects on IL-6 and cytokine activities [40], suggesting a mechanism by which Se can regulate bone turnover and, in turn, have a protective effect on OP. Second, evidence has also shown that ROS plays an important role in the development of OP [14]. Selenoproteins, which have been proved as the essential Se transporter to bones [41], can be expressed in both bone-resorbing osteoclasts and bone-forming osteoblasts, and eliminate ROS after being generated [42, 43]. Thus, a limiting threshold of Se is probably required for adequate selenoprotein-mediated antioxidant activity and bone maintenance [44]. Third, the Se-dependent iodothyronine deiodinases can control thyroid hormone turnover, and Se-dependent glutathione peroxidases are implicated in thyroid gland protection. Therefore, the lack of Se may increase the level of thyroid hormones in the blood [45], which may accelerate bone loss and lead to OP [46].

As the first study, to the best knowledge of the authors, directly relating dietary Se intake to OP in a general context, this cross-sectional study is characterized with several strengths. First, it demonstrated a potential role of appropriate dietary Se intake in preventing the development of OP. Second, by adjusting the multivariable model for a number of potential confounders, the reliability of the results was significantly improved. Third, with a relatively large sample size, this study was believed to have a low occasionality in the findings. Fourth, dietary Se intake in our study (43.5 μg/day) is similar to the dietary Se intake in European populations (40 μg/day) [47], thus, our findings may be generalizable to the European populations. However, dietary Se intake of American population (93 μg/day in women and 134 μg/day in men) [29, 47, 48] is higher than our population, so generalizing the findings to the American population may warrant further studies.

On the other hand, the limitations should be acknowledged as well. First, the causal relationship between dietary Se intake and the prevalence of OP was not addressed in the present study, so the conclusions should be reassured by further prospective studies. Second, the BMD was detected at the phalanges with a compact digital RA system in this study, while the gold standard for OP diagnosis is to measure BMD at the hip and spine using a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) [49, 50]. Unfortunately, DXA is a very costly diagnostic method requiring frequent calibrations, so it is still seldom used in developing countries. In fact, several cohorts have examined the efficacy of phalangeal RA while utilizing the same measuring system [31, 51, 52]. For example, Steven et al. [51] detected the BMD at the intermediate phalanges of the second to fourth fingers, the lumbar spine (L2-L4), and the total hip in 221 women (50–75 years) using RA (Alara Metriscan, Hayward, Calif., USA) and DXA (Hologic Inc., Waltham, Mass., USA), and concluded that the sensitivity of RA in identifying OP was 82.9% and its negative predictive value (i.e., the proportion of patients who have no OP, but received a negative test) was 90%, in comparison with DXA. This suggested that phalangeal RA could be used as an effective method for OP measurement. Third, deducing Se intake from SFFQ may be difficult, because Se content of foods is very variable [53], meanwhile, Se content can be affected by food preparation or cooking [54], and can vary differently by country and region [55]. However, SFFQ has been widely used in the previous studies as a tool of evaluating dietary Se intake, and has been proved to be a valid and reliable method to estimate Se intake [15, 38, 56, 57]. Fourth, because of no specific questionnaires being set, we did not exclude people who received hormone therapy, glucocorticoids and bisphosphonates in our final analysis. Considering that the proportion of hormone therapy, glucocorticoids, or bisphosphonates use in the general population in China is relatively low [58, 59], so the usage of these medicines may have a minor effect on our final results.

Conclusion

In the middle-aged and elderly humans, participants with lower levels of dietary Se intake have a higher prevalence of OP in a dose-response manner.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the support of Orthopedics Research Institute of Xiangya Hospital.

Abbreviations

- BMD

bone mineral density

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- DXA

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- FBG

fasting blood glucose

- OP

osteoporosis

- OR

odds ratio

- RA

radiographic absorptiometry

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SD

standard deviation

- Se

selenium

- SFFQ

semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire

Authors’ contributions

Study conception and design: YQW, DXX and YLW. Acquisition of the data: JTL, HZL and ZYW. Analysis and interpretation of data: JW, HYH and HCW. Draft of the manuscript: YQW and DXX. Revision of the manuscript: YLW and TY. All authors provided final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Innovation Foundation of the Central South University for Postgraduate (2018zzts256), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802212), the Scientific Research Project of Science and Technology Office of Hunan Province (2017TP1005), the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (2018SK2070), the Xiangya Clinical Big Data System Construction Project of Central South University (45), the Clinical Scientific Research Foundation of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2015 L03). Funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (reference numbers: 201312459), and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuqing Wang and Dongxing Xie contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285(6):785–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence, mortality and disability associated with hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(11):897–902. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wade SW, Strader C, Fitzpatrick LA, Anthony MS, O'Malley CD. Estimating prevalence of osteoporosis: examples from industrialized countries. Arch Osteoporos. 2014;9:182. doi: 10.1007/s11657-014-0182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng Q, Li N, Wang Q, Feng J, Sun D, Zhang Q, Huang J, Wen Q, Hu R, Wang L, et al. The prevalence of osteoporosis in China, a nationwide, multicenter DXA survey. J Bone Miner Res. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Aaseth J, Boivin G, Andersen O. Osteoporosis and trace elements--an overview. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2012;26(2–3):149–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heaney RP. Calcium, dairy products and osteoporosis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(2 Suppl):83s–99s. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recker RR, Hinders S, Davies KM, Heaney RP, Stegman MR, Lappe JM, Kimmel DB. Correcting calcium nutritional deficiency prevents spine fractures in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(12):1961–1966. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(10):670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zofkova I, Nemcikova P, Matucha P. Trace elements and bone health. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51(8):1555–1561. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allan CB, Lacourciere GM, Stadtman TC. Responsiveness of selenoproteins to dietary selenium. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng H. Selenium as an essential micronutrient: roles in cell cycle and apoptosis. Molecules. 2009;14(3):1263–1278. doi: 10.3390/molecules14031263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lei XG, Cheng WH, McClung JP. Metabolic regulation and function of glutathione peroxidase-1. Annu Rev Nutr. 2007;27:41–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunde RA. Molecular biology of selenoproteins. Annu Rev Nutr. 1990;10:451–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.10.070190.002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manolagas SC. From estrogen-centric to aging and oxidative stress: a revised perspective of the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. Endocr Rev. 2010;31(3):266–300. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf RL, Cauley JA, Pettinger M, Jackson R, Lacroix A, Leboff MS, Lewis CE, Nevitt MC, Simon JA, Stone KL, et al. Lack of a relation between vitamin and mineral antioxidants and bone mineral density: results from the Women's Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(3):581–588. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Munger RG, West NA, Cutler DR, Wengreen HJ, Corcoran CD. Antioxidant intake and risk of osteoporotic hip fracture in Utah: an effect modified by smoking status. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(1):9–17. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun LL, Li BL, Xie HL, Fan F, Yu WZ, Wu BH, Xue WQ, Chen YM. Associations between the dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of hip fracture in elderly Chinese: a case-control study. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(10):1706–1714. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514002773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beukhof CM, Medici M, van den Beld AW, Hollenbach B, Hoeg A, Visser WE, de Herder WW, Visser TJ, Schomburg L, Peeters RP. Selenium status is positively associated with bone mineral density in healthy aging European men. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeg A, Gogakos A, Murphy E, Mueller S, Kohrle J, Reid DM, Gluer CC, Felsenberg D, Roux C, Eastell R, et al. Bone turnover and bone mineral density are independently related to selenium status in healthy euthyroid postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(11):4061–4070. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al EAA, Parsian H, Fathi M, Faghihzadeh S, Hosseini SR, Nooreddini HG, Mosapour A. ALOX12 gene polymorphisms and serum selenium status in elderly osteoporotic patients. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27(12):1717–1722. doi: 10.17219/acem/75689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeng C, Wei J, Terkeltaub R, Yang T, Choi HK, Wang YL, Xie DX, Hunter DJ, Zhang Y, Li H, et al. Dose-response relationship between lower serum magnesium level and higher prevalence of knee chondrocalcinosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):236. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng C, Wei J, Li H, Yang T, Zhang FJ, Pan D, Xiao YB, Yang TB, Lei GH. Relationship between serum magnesium concentration and radiographic knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(7):1231–1236. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie DX, Xiong YL, Zeng C, Wei J, Yang T, Li H, Wang YL, Gao SG, Li YS, Lei GH. Association between low dietary zinc and hyperuricaemia in middle-aged and older males in China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e008637. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Zeng C, Li H, Yang T, Deng ZH, Yang Y, Ding X, Xie DX, Wang YL, Lei GH. Relationship between cigarette smoking and radiographic knee osteoarthritis in Chinese population: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(7):1211–1217. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-3202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng ZH, Zeng C, Li YS, Yang T, Li H, Wei J, Lei GH. Relation between phalangeal bone mineral density and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:71. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-0918-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Zeng C, Wei J, Yang T, Gao SG, Li YS, Lei GH. Associations between dietary antioxidants intake and radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(6):1585–1592. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma X, Yang Y, Li HL, Zheng W, Gao J, Zhang W, Yang G, Shu XO, Xiang YB. Dietary trace element intake and liver cancer risk: results from two population-based cohorts in China. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(5):1050–1059. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Qiu X, Zhong C, Zhang K, Xiao M, Yi N, Xiong G, Wang J, Yao J, Hao L, et al. Reproducibility and relative validity of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire for Chinese pregnant women. Nutr J. 2015;14:56. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0044-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fairweather-Tait SJ, Bao Y, Broadley MR, Collings R, Ford D, Hesketh JE, Hurst R. Selenium in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14(7):1337–1383. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rayman MP. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1256–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorpe JA, Steel SA. The Alara Metriscan phalangeal densitometer: evaluation and triage thresholds. Br J Radiol. 2008;81(970):778–783. doi: 10.1259/bjr/69540165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmberg T, Bech M, Curtis T, Juel K, Gronbaek M, Brixen K. Association between passive smoking in adulthood and phalangeal bone mineral density: results from the KRAM study--the Danish health examination survey 2007-2008. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(12):2989–2999. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friis-Holmberg T, Brixen K, Rubin KH, Gronbaek M, Bech M. Phalangeal bone mineral density predicts incident fractures: a prospective cohort study on men and women--results from the Danish health examination survey 2007-2008 (DANHES 2007-2008) Arch Osteoporos. 2012;7:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s11657-012-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanis JA. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group Osteoporos Int. 1994;4(6):368–381. doi: 10.1007/BF01622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schottker B, Herder C, Rothenbacher D, Perna L, Muller H, Brenner H. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and incident diabetes mellitus type 2: a competing risk analysis in a large population-based cohort of older adults. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(3):267–275. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9769-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothman KJ, Moore LL, Singer MR, Nguyen US, Mannino S, Milunsky A. Teratogenicity of high vitamin a intake. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(21):1369–1373. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511233332101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pedrera-Zamorano JD, Calderon-Garcia JF, Roncero-Martin R, Manas-Nunez P, Moran JM, Lavado-Garcia JM. The protective effect of calcium on bone mass in postmenopausal women with high selenium intake. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16(9):743–748. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melhus H, Michaelsson K, Holmberg L, Wolk A, Ljunghall S. Smoking, antioxidant vitamins, and the risk of hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14(1):129–135. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manolagas SC. The role of IL-6 type cytokines and their receptors in bone. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:194–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duntas LH. Selenium and inflammation: underlying anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41(6):443–447. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pietschmann N, Rijntjes E, Hoeg A, Stoedter M, Schweizer U, Seemann P, Schomburg L. Selenoprotein P is the essential selenium transporter for bones. Metallomics. 2014;6(5):1043–1049. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00003J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jakob F, Becker K, Paar E, Ebert-Duemig R, Schutze N. Expression and regulation of thioredoxin reductases and other selenoproteins in bone. Methods Enzymol. 2002;347:168–179. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)47015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams AJ, Robson H, Kester MHA, van Leeuwen J, Shalet SM, Visser TJ, Williams GR. Iodothyronine deiodinase enzyme activities in bone. Bone. 2008;43(1):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon HJ, Ko WK, Han SW, Kim DS, Hwang YS, Park HK, Kwon IK. Antioxidants, like coenzyme Q10, selenite, and curcumin, inhibited osteoclast differentiation by suppressing reactive oxygen species generation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;418(2):247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schomburg L, Kohrle J. On the importance of selenium and iodine metabolism for thyroid hormone biosynthesis and human health. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52(11):1235–1246. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams GR, Bassett JHD. Thyroid diseases and bone health. J Endocrinol Investig. 2018;41(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s40618-017-0753-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rayman MP. Food-chain selenium and human health: emphasis on intake. Br J Nutr. 2008;100(2):254–268. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508939830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rayman MP. Selenium in cancer prevention: a review of the evidence and mechanism of action. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64(4):527–542. doi: 10.1079/PNS2005467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ito M. Absolute risk for fracture and WHO guideline. Recent interest in bone quality. Clin Calcium. 2007;17(7):1066–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boot AM, de Ridder MA, van der Sluis IM, van Slobbe I, Krenning EP, Keizer-Schrama SM. Peak bone mineral density, lean body mass and fractures. Bone. 2010;46(2):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boonen S, Nijs J, Borghs H, Peeters H, Vanderschueren D, Luyten FP. Identifying postmenopausal women with osteoporosis by calcaneal ultrasound, metacarpal digital X-ray radiogrammetry and phalangeal radiographic absorptiometry: a comparative study. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(1):93–100. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buch I, Oturai PS, Jensen LT. Radiographic absorptiometry for pre-screening of osteoporosis in patients with low energy fractures. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010;70(4):269–274. doi: 10.3109/00365511003786365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rayman MP, Infante HG, Sargent M. Food-chain selenium and human health: spotlight on speciation. Br J Nutr. 2008;100(2):238–253. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508922522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Virili C, Centanni M. Does microbiota composition affect thyroid homeostasis? Endocrine. 2015;49(3):583–587. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Combs GF., Jr Selenium in global food systems. Br J Nutr. 2001;85(5):517–547. doi: 10.1079/BJN2000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bedard A, Northstone K, Holloway JW, Henderson AJ, Shaheen SO. Maternal dietary antioxidant intake in pregnancy and childhood respiratory and atopic outcomes: birth cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.van Woudenbergh GJ, van Ballegooijen AJ, Kuijsten A, Sijbrands EJ, van Rooij FJ, Geleijnse JM, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Feskens EJ. Eating fish and risk of type 2 diabetes: a population-based, prospective follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2021–2026. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang D, Haines CJ, Pan P, Zhang Q, Sun Y, Hong S, Tian F, Bai B, Peng X, Chen W, et al. Menopausal symptoms in mid-life women in southern China. Climacteric. 2008;11(4):329–336. doi: 10.1080/13697130802239075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chu K, Song Y, Chatooah ND, Weng Q, Ying Q, Ma L, Qu F, Zhou J. The use and discontinuation of hormone replacement therapy in women in South China. Climacteric. 2018;21(1):47–52. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2017.1397622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be requested from the corresponding author.