Abstract

A dense population of embryo-derived Langerhans cells (eLC) is maintained within the sealed epidermis without contribution from circulating cells. When this network is perturbed by transient exposure to ultra-violet light, short-term LC are temporarily reconstituted from an initial wave of monocytes, but thought to be superseded by more permanent repopulation with undefined LC precursors. However, the extent to which this process is relevant to immune-pathological processes that damage LC population integrity is not known. Using a model of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, where allo-reactive T cells directly target eLC, we have asked if and how the original LC network is ultimately restored. We find that donor monocytes, but not dendritic cells, are the precursors of the long-term LC in this context. Destruction of eLC leads to recruitment of a wave of monocytes that engraft in the epidermis and undergo a sequential pathway of differentiation via transcriptionally distinct EpCAM+ precursors. Monocyte-derived LC acquire the capacity of self-renewal, and proliferation in the epidermis matched that of steady state eLC. However, we identified a bottleneck in the differentiation and survival of epidermal monocytes, which together with the slow rate of renewal of mature LC limits repair of the network. Furthermore, replenishment of the LC network leads to constitutive entry of cells into the epidermal compartment. Thus, immune injury triggers functional adaptation of mechanisms used to maintain tissue-resident macrophages at other sites, but this process is highly inefficient in the skin.

One sentence summary:

Following immune damage in the epidermis, monocytes from the circulation give rise to epidermal Langerhans cells.

Introduction

Langerhans cells (LC) are unique mononuclear phagocytes that reside within the epithelial layer of the skin and mucosal tissues (1, 2), where they play a key role in regulating immunity at the barrier surface. Loss of LC-dependent immune surveillance leads to a break-down in skin tolerance, and increased susceptibility to infection (3). Within the skin, embryonic (e)LC differentiate from yolk sac and fetal common tissue macrophage precursors that seed the skin before birth (4, 5)(6)(7)(8). The density of the adult eLC network is established post-birth by a burst of local proliferation of differentiated eLC in response to undefined signals (9). Subsequently, the mature network is maintained by low levels of clonal cell division within adult skin (10–12). By contrast, oral mucosal epithelia are populated by LC-like cells that are continuously seeded from recruited monocytes and dendritic cell (DC) precursors (1). These cells resemble epidermal eLC transcriptionally and phenotypically, but show little evidence of proliferation in situ, and rather depend on recruitment of blood-derived cells to maintain the cellular niche (1, 13).

Ablation of eLC from genetically engineered mice leads to patchy repopulation of the epidermis (14), due to division of surviving eLC with some contribution from bone marrow (BM) cells (12, 15). In this non-inflamed context, the replenishment of the empty niche is characterized by the slow kinetics by which emerging LC expand to fill the epidermis, reflecting the quiescent nature of mature LC within the skin environment (3). By contrast, severe perturbation of eLC in the context of inflammation leads to recruitment of BM-derived cells into the epidermis, and repopulation of the empty niche (10, 16). The cellular mechanisms by which this occurs have largely been defined using models in which transient acute exposure of murine skin to UV irradiation leads to cell death within the epidermis and eLC replacement. Under these conditions, Gr-1+ monocytes are recruited to the epidermis (17, 18). While some studies suggest that these monocytes can differentiate into long-term LC (17, 19), others have proposed a two wave model of eLC replacement, in which monocytes can persist for up to 3 weeks as ‘short-term’ LC-like cells, but are superseded by undefined precursors which become long-lived replacement LC (18). Central to this model is the observation that LC require the transcription factor Id2 for their development and persistence as long-lived quiescent cells (18). But, it remains controversial whether Id2 is required for repopulation of the LC niche after UV-irradiation (20). The nature of the long-term LC precursors remains a key question in the field, with a number of studies suggesting the potential for dendritic cells (DC) or their precursors, to seed epidermal LC in the adult (21–25).

The resident macrophage population in most tissues is maintained by recruitment of Ly6C+ classical monocytes from the blood (26). Ly6C+ monocytes are short-lived, non-dividing cells once they have left the BM; however they show remarkable plasticity upon differentiation and recent studies have defined a dominant role of the local tissue niche in shaping differentiation of recruited cells (27, 28). One active area of investigation is whether monocyte-derived macrophages can transcriptionally and functionally replace the resident macrophage populations that were originally seeded from intrinsically distinct precursors at birth. In the steady state, genetic ablation of tissue resident cells results in the differentiation of Ly6C+ monocytes into Kupffer cells (29) and alveolar macrophages (30) in the liver and lung, respectively, that show few differences from the cells they replace. By contrast, genetic ablation of microglia leads to repopulation by monocyte-derived cells that appear to fulfill the functional roles of their resident counterparts, but remain morphologically distinct, and continue to express monocyte-related genes (31, 32). Whether re-emerging skin LC, driven by immune injury and inflammation in the skin, also retain evidence of their cellular origin, and to what extent repopulating cells can become a long-term quiescent LC network, remain pertinent questions. Not least because monocyte-derived cells in other inflamed tissues remain transcriptionally and functionally distinct from resident cells (33, 34).

We have exploited a murine model of hematopoietic stem cell transplant to define the cellular mechanisms that control re-building of the LC network after immune-mediated pathology. We have previously shown that allo-reactive T cells infiltrate the epidermis in this model, wherein interaction with eLC leads to enhanced cytotoxic function and survival (35). Activated T cells target recipient keratinocytes and eLC (16), leading to graft-versus-host disease (35). We demonstrate that T cell-mediated destruction of eLC leads to the recruitment of of monocytes that seed long-term monocyte-derived (m)LC, which are indistinguishable from the embryo-derived cells that have been replaced. We provide evidence for a surge of monocyte recruitment to the epidermis, but differentiation of these cells into mLC is a rate-limiting step, resulting in inefficient rebuilding of the mature LC network. In addition, the epidermal compartment is not re-sealed after entry of T cells, and remains open to circulating cells. Thus, immune injury triggers an adaptive process that converges with mechanisms to regenerate other tissue-resident macrophages, but this is highly inefficient in the skin.

Results

Immune injury leads the gradual replenishment of the epidermis with LC-like cells.

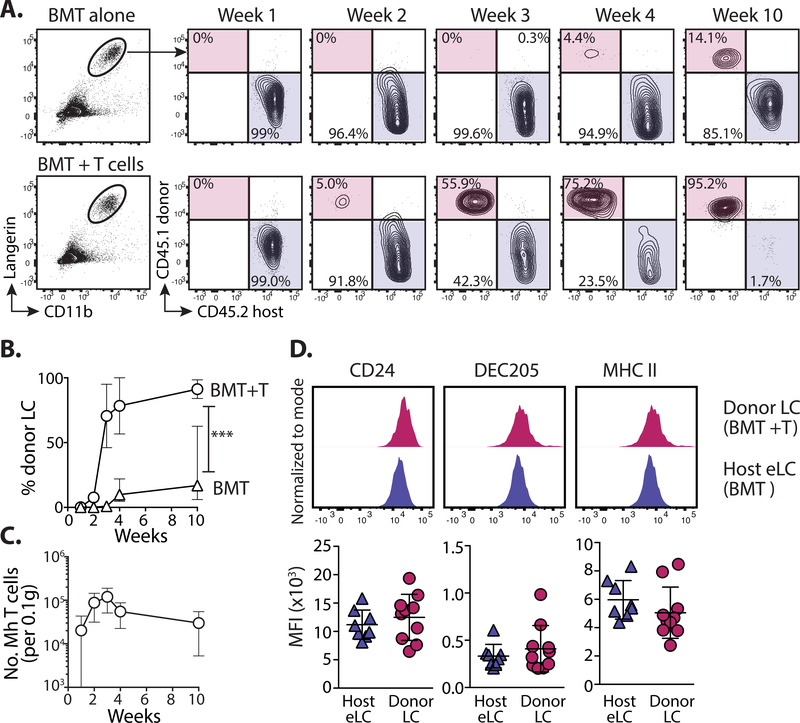

We and others have previously shown that transfer of CD8+ male minor histocompatibility antigen-reactive Matahari (Mh) T cells with BM transplantation (BMT) (35, 36) leads to infiltration of pathogenic T cells into target organs and the development of sub-lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) (37). Intra-vital imaging by our lab demonstrated direct interactions between Mh T cells and host LC within the epidermis (35) and the onset of GVHD pathology 2 weeks post-transplant (35). Once in the epidermis, CD8 T cells kill host LC via Fas ligand-dependent cytoxicity (16). We determined the kinetics of LC turn-over following immune injury and eLC destruction in our transplant model (Figure S1). eLC are radio-resistant (16) and persisted in control mice that received BMT alone. A small population of donor BM-derived cells was evident in some mice 10 weeks post-transplant, but we observed significant variability between mice (Figure 1A top panel and B). Loss of eLC was complimented by the emergence of donor BM-derived CD11b+Langerin+ LC-like cells in the epidermis 2 weeks post-transplant, which increased sharply in frequency and number between 2–3 weeks (Figure 1A bottom panel and B), concomitant with the peak of Mh T cell numbers in the epidermis (Figure 1C). The development of full donor LC chimerism was gradual and evident by week 10 post-transplant. At this time-point repopulating donor CD11b+Langerin+ LC-like cells were phenotypically indistinguishable from host eLC in BMT controls according to markers defined in previous studies (Figure 1D) (18, 38)

Figure 1. Immune injury leads the gradual replenishment of the epidermis with LC-like cells.

A. Male recipients received female BM alone (BMT) or with CD4 and CD8 (Matahari) T cells. Chimerism was measured within the mature CD11b+Langerin+ LC population at different time points. Representative flow plots show the relative frequency of host (CD45.2) and donor (CD45.1)-derived cells. B. Graph showing the frequency ± SD of donor LC in mice receiving BMT with (circles) or without (triangles) T cells. Significance was determined with a 2-way ANOVA, ***P<0.001. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments for each time point (n=5–10). C. Graph shows the number ± SD of Vβ8.3+ Matahari (Mh) T cells in the epidermis over time, per 0.1g total ear tissue (n=7–8). D. Top - representative histogram overlays show the expression of LC-associated proteins on donor-derived LC (from mice that received BMT + T cells) or host eLC (BMT alone), 10 weeks post-transplant. Bottom - summary data showing the median fluorescent intensity (MFI) for each sample. H = host, D = donor, each symbol is one mouse. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n=8), and representative of >3 different experiments.

DC lineage cells do not become long-term replacement LC.

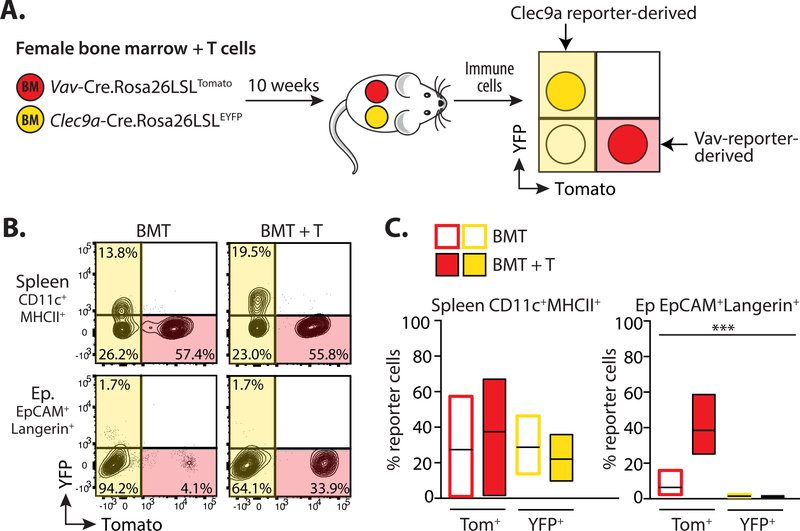

The DC-like nature of LC has led to the suggestion that DC lineage cells may contribute to adult LC, and/or seed repopulating cells after damage (21, 23). This hypothesis has recently been supported by work demonstrating that circulating human CD1c+ DC have the potential to become LC-like cells in vitro, but this has not been directly tested in vivo (24, 25). Therefore, we investigated the possibility that DC lineage cells may contribute to LC repopulation after immune injury, by transplanting irradiated male recipients with a 1:1 mixture of BM from Vav-Cre.Rosa26LSLTomato (VavTom) and Clec9a-Cre.Rosa26LSLEYFP (Clec9aYFP) reporter lines. The Vav-Cre transgene is expressed by all hematopoietic cells (39) and provided an internal control for the development of BM-derived LC, while Clec9a-dependent YFP marked cells restricted to the DC lineage (40) (Figure 2A). 10 weeks later, an average of 37 ± 14.1% (s.e.m.) of splenic CD11c+MHCII+ cells were derived from VavTom BM in the BMT + T group. Of the Clec9aYFP-derived cells, 36 ± 2.6% (s.e.m.) expressed YFP. By contrast, while there was a clear contribution of donor VavTom cells to repopulating LC after BMT with T cells, we did not detect any YFP+ LC (Figures 2B and C).

Figure 2. DC lineage cells do not become long-term replacement LC.

A. Schematic showing the experimental procedure. Male mice received female BMT with T cells. BM was composed of a 1:1 mixture of cells from syngeneic female Clec9aYFP and VavTom mice. 10 weeks later splenocytes and epidermal LC were assessed for the relative contribution of cells expressing Tomato (Tom) or YFP. B. Representative contour plots showing gated CD11c+MHCII+ cells in the spleen or CD11b+EpCAM+Langerin+ LC in the epidermis of mice that received BMT with or without T cells. C. Summary bar graphs showing the frequency of red Tom+ or yellow YFP+ cells within splenic CD11c+MHCII+ (left) or epidermal EpCAM+Langerin+ (right) cells in mice receiving BMT alone (open bars) or BMT with T cells (filled bars). Bars show the mean and range of data points. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments, and analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA, ***P<0.001 (n = 5–6).

LC repopulation is preceded by influx of donor CD11b+ cells.

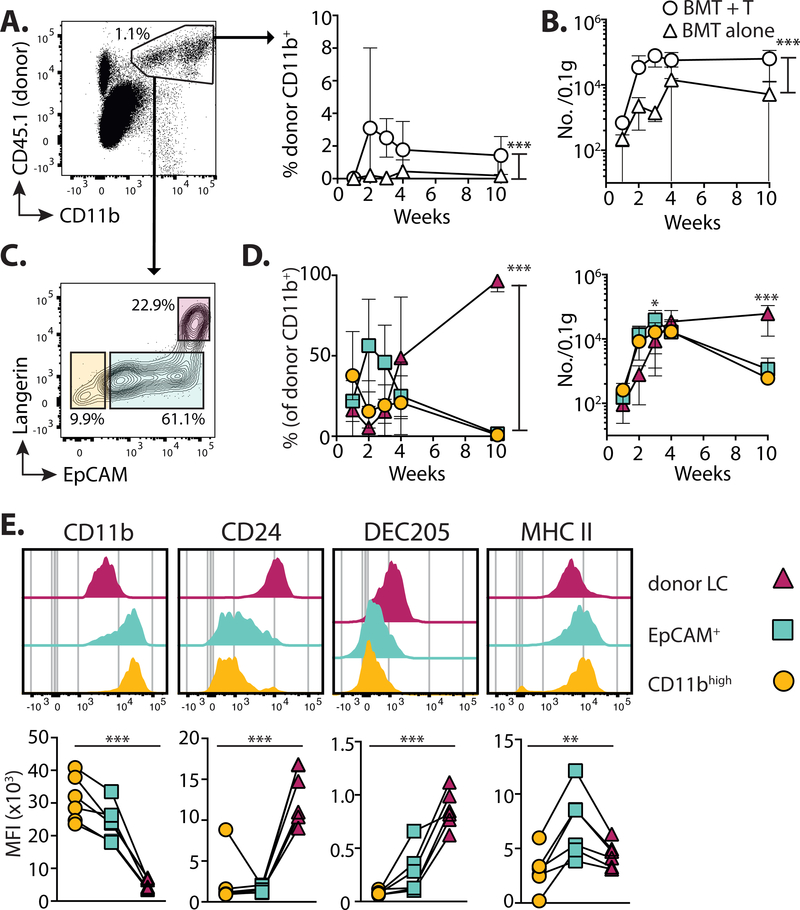

Mature LC are identified by the unique concomitant expression of high levels of the cell adhesion molecule EpCAM (CD326) and the C-type lectin receptor, Langerin (CD207), which are simultaneously up-regulated upon differentiation of eLC (9, 19, 41). By contrast, ‘short-term’ LC, do not up-regulate EpCAM after UV irradiation (18). We observed the T cell-dependent accumulation of CD11bint to high cells within the epidermis (Figures 3A and B), that peaked 3 weeks post-transplant and before the shift to donor LC chimerism shown in Figure 1A. Phenotypic analysis of these cells demonstrated the presence of 3 populations sub-divided by expression of EpCAM and Langerin (Figure 3C): donor CD11bhigh cells contained 2 sub-populations that were either negative/low for both markers, suggesting recent arrival in the epidermis, or solely expressed EpCAM; by comparison CD11bint cells were EpCAMhighLangerinhigh and therefore resembled mature LC. For this paper, we will refer to these populations as “CD11bhigh”, “EpCAM+” and “donor LC”, respectively. We observed a peak in the frequency and number of EpCAM+ cells between 2–3 weeks post-transplant, preceding the gradual accumulation of donor LC over time (Figure 3D). These data strongly suggested a developmental trajectory whereby a wave of epidermal CD11bhigh cells repopulated the mature LC network. We reasoned that acquisition of LC-defining proteins would be consistent with the developmental transition of these sub-populations. Indeed, we observed the gradual loss of CD11b, and up-regulation of CD24 and DEC205 with differentiation of donor LC (Figure 3E).

Figure 3. LC repopulation is preceded by influx of CD11b+ cells.

Mice received BMT with T cells, and the epidermis was analyzed at different time points. A. Left - dot plot shows the gating of single CD11bint to highCD45.1+ donor myeloid cells. Right - summary graph showing the frequency ± SD donor CD11b+ cells in mice receiving BMT alone (triangles) or BMT + T cells (circles) (n= 6–7). B. Graph shows the number ± SD per 0.1g total ear weight of donor CD11b+ cells (n=5–10). C. Representative contour plots at 3 weeks showing 3 distinct sub-populations within single CD11bint to highCD45.1+ cells. D. Summary graphs showing the frequency ± SD (left) and number ±SD (right) of cells within each of the gated populations shown in C: Circles CD11bhigh (EpCAMnegLangerinneg); squares EpCAM+; triangles donor LC (EpCAM+Langerin+) (n=7–8). Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments and analyzed by 2-way ANOVA for frequency; significance for numbers was calculated with a 2-way ANOVA with Tukeys multiple comparisons test. E. Top - representative histogram overlays show surface expression levels of LC-defining proteins in the gated donor populations 3 weeks post-transplant. Bottom - graphs show summary data for the median fluorescent intensity (MFI). Symbols represent individual samples, analyzed using a repeated measurements 1-way ANOVA. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

EpCAM+ monocyte-derived cells are distinct from donor LC.

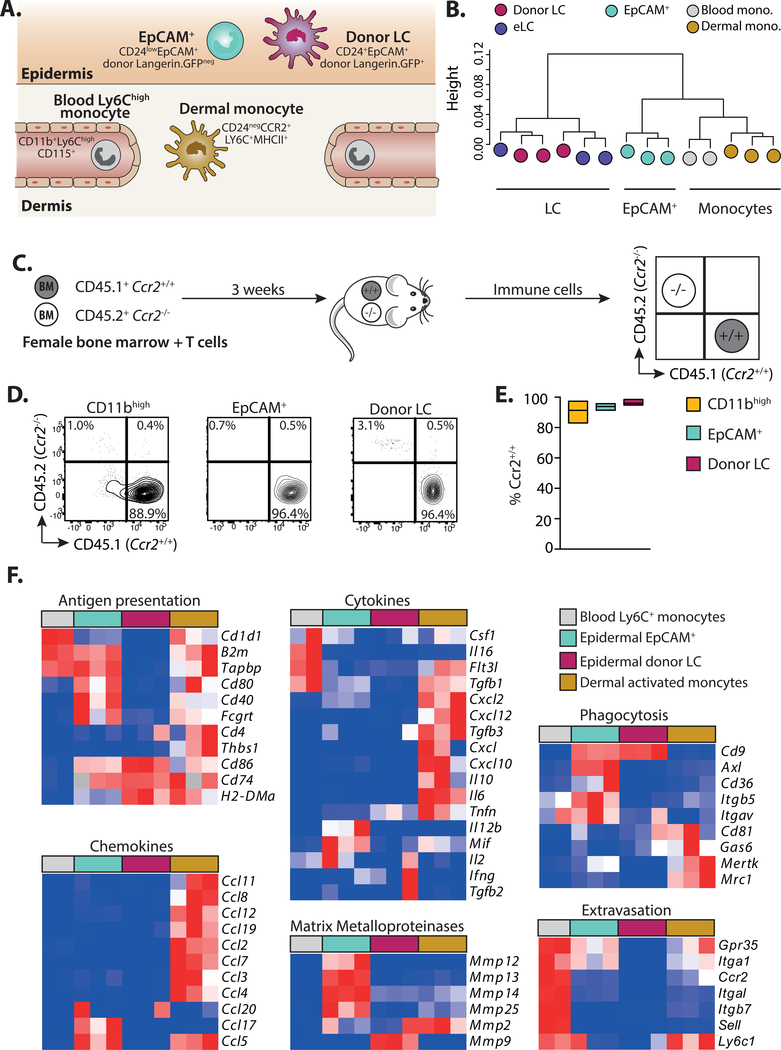

Our phenotyping data suggested that incoming CD11b+ cells differentiated into a unique EpCAM+ intermediate before becoming donor LC, but it was possible that EpCAM+ cells were already immature LC. To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared the transcriptional profile of EpCAM+ cells to donor LC or other CD11b+ populations in the skin and blood (Figure 4A and see Figure S2 for sorting strategy). Hierarchical clustering demonstrated that eLC and donor LC were interchangeable, but that EpCAM+ cells clustered as a distinct population, and were more closely aligned to blood and dermal monocytes than mature LC (Figure 4B). Analysis of the genes that contributed to differences along the PC1 axis after principle components analysis (Figure S3A) demonstrated that EpCAM+ cells were distinguished by the down-regulation, but not loss, of expression of genes associated with monocyte development and function (e.g. Prr5, Ccl9, Fcgr3 and Fcgr4, Trem3, Tlr7) (Figure S3B), including Treml4, which is expressed by Ly6C+ monocytes with the potential to become moDC (42). However, EpCAM+ cells had not up-regulated genes associated with changes to cell structure, adhesion and signaling that defined donor LC (e.g. Emp2, Kremen2, Nedd4, Ptk7). Given the distinct clustering of monocytes/EpCAM+ cells and eLC/donor LC, we directly tested the contribution of monocytes to emerging LC by transferring mixed congenic Ccr2+/+ and syngeneic Ccr2−/− BM with T cells (Figure 4C). CCR2 is required for both egress of monocytes from the BM and entry into tissues (43). We found that only Ccr2+/+ cells contributed to CD11bhigh, EpCAM+ and donor LC sub-populations (Figures 4D and E), suggesting a monocytic origin for these cells.

Figure 4. EpCAM+ monocyte-derived cells are distinct from donor LC.

A. Schematic showing the populations of cells and phenotypic markers used to isolate cells for sequencing. B. Dendrogram showing clustering of samples. C. Schematic illustrating competitive chimera experiments to test the requirement for monocyte-derived cells. Male mice received female BMT with T cells. BM was composed of a 1:1 mixture of cells from congenic wild-type (CD45.1+Ccr2+/+) or CCR2-deficient (CD45.2+Ccr2−/−) mice. Epidermal cells were analyzed 3 weeks later. D. Representative contour plots showing the frequency of wild-type or knock-out cells within gated donor epidermal myeloid cells (host cells were excluded at this time point by the use of Langerin.EGFP recipients, and exclusion of GFP+ LC from our analyses). E. Summary data showing the frequency of Ccr2+/+, donor cells within each population. Bar graphs show the mean and range of data points, data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n=6). Percent of Ccr2+/+ cells versus Ccr2−/− in each population ***P<0.001, 1-way ANOVA. F. Heat maps showing relative gene expression of defined genes grouped into panels according to distinct functional processes. Blood monocytes (grey) n = 2, EpCAM+ cells (cyan) n = 3, donor LC (magenta) n = 3, dermal monocytes (grey) n = 3.

Ly6C+ monocytes mature into MHCII+ activated monocytes (or monocyte-derived DC) in the dermis (44). Therefore, we directly compared the outcomes of monocyte differentiation within different skin compartments using panels of genes associated with monocyte maturation and function described by Schridde and colleagues (45) (Figure 4F). This analysis demonstrated the clear divergence between Ly6C+ monocytes differentiating within the dermis or epidermis. EpCAM+ cells displayed a unique gene signature associated with tissue homeostasis and modulation of the epidermal niche by matrix metalloproteinases (mmp12, mmp13, mmp14, mmp25, but not mmp2 and mmp9 which are associated with egress of mature LC out of the epidermis (46)); phagocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells (cd9, axl, cd36, itgb5, itgav); and activation of complement (c1qa, c1qb, c1qc). However, EpCAM+ also retained shared patterns of gene expression with moDC that suggested recent extravasation from the blood (gpr35, itga1, ccr2), and the potential to activate of T cells (b2m, tapbp, cd80, cd40, fcgrt), which was lacking from LC.

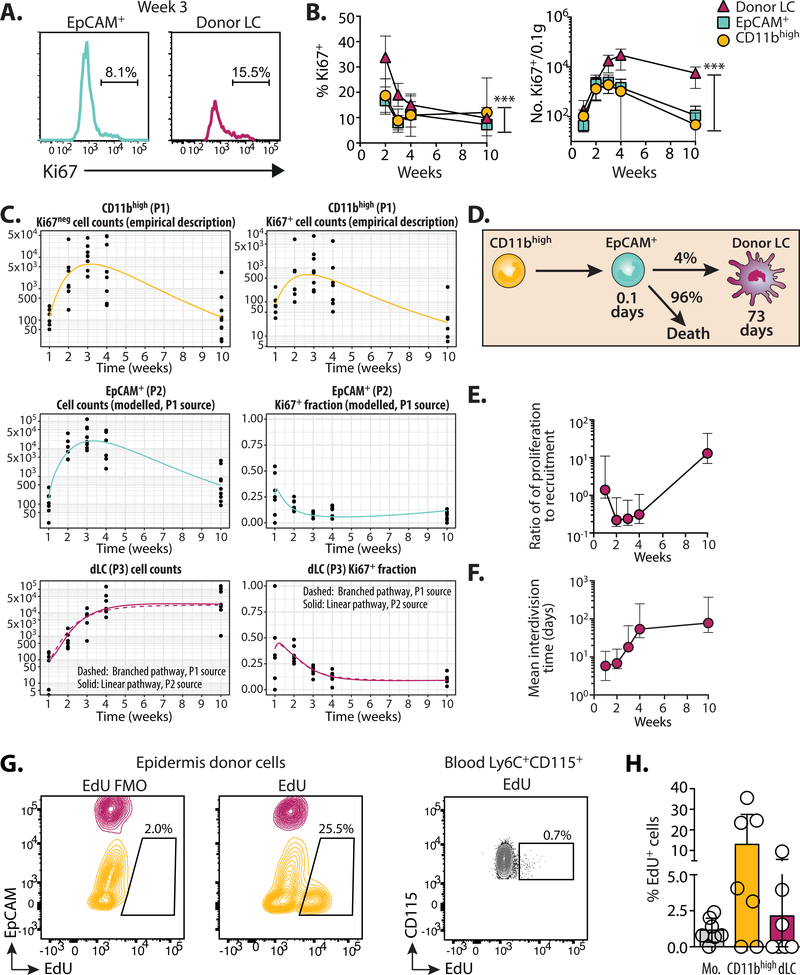

Proliferation of monocytes and LC in situ combine to replenish the LC network.

Our data implied that monocytes were sufficient to replenish the LC network, but Ly6C+ monocytes are short-lived non-cycling cells, while proliferation of eLC at birth and in adults determines the density LC within the epidermis (9, 12). Therefore, we considered the relative importance of recruitment versus proliferation of epidermal CD11b+ cells for the rebuilding of the LC network. We constructed mathematical models to quantify the flows between CD11bhigh to EpCAM+ populations and the donor mLC pool using time courses of Ki67 expression (Figure 5A and B). All epidermal populations showed evidence of active or recent cell division after transplant which decreased to homeostatic rates equivalent to eLC by 10 weeks (9.8 ± 1.49% (s.e.m.) (9). Models of the flow from CD11bhigh cells to EpCAM+ were fitted simultaneously to the time courses of total cell numbers and Ki67 expression in the two populations. The kinetics of EpCAM+ cell numbers closely tracked that of the CD11bhigh population, suggesting that EpCAM+ cells were short-lived and/or rapidly underwent onward differentiation (Table 1). We first explored whether the flow of CD11bhigh and EpCAM+ cells into donor LC were consistent with a linear developmental pathway, as predicted by our experimental data. This was compared to the alternative scenario in which EpCAM+ cells were a ‘dead end’ population and wherein monocytes differentiated directly into LC, which we named the branched pathway (Figure S4A). The fitted predictions of the two models were visually similar (Figure 5C). Nevertheless, we found approximately 10-fold greater statistical support for the linear pathway, as measured by weights calculated using the Akaike Information Criterion (47). Strikingly, however, maturation of EpCAM+ cells was highly inefficient with only 4% becoming donor mLC (Figure 5D and Table 1). Gene set enrichment analysis of EpCAM+ cells compared to donor LC suggests that most EpCAM+ cells underwent apoptosis within the epidermis (Figure S4B).

Figure 5. Proliferation of monocytes and LC in situ combine to replenish the LC network.

Mice received BMT with T cells. Total numbers and Ki67 expression of epidermal cells were analyzed at different time points and described with mathematical models. A. Representative histograms show gating of Ki67+ cells in the EpCAM+ and donor LC populations 3 weeks after BMT with T cells. B. Graphs show the frequency ± SD (left) and number ± SD per 0.1g total ear tissue (right) of Ki67+ cells within gated epidermal populations. Circles CD11bhigh; squares EpCAM+; triangles donor LC. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments per time point (n = 7–8) and significance calculated using a 2-way ANOVA, ***P<0.001. C. Data from the experiments shown in B. were described with mathematical models. Upper panels - Fitted, empirical descriptions of the timecourses of Ki67+ and Ki67- CD11bhigh cells. Middle panels - fits to the total numbers and Ki67+ fraction of EpCAM+ cells, using the empirical descriptions of the CD11bhigh cell kinetics as a source. Lower panels - fits to timecourses of mature LC numbers and the Ki67+ fraction using either CD11bhigh (P1) or EPCAM+ cells (P2) as a source. D. The model of a linear development pathway had the strongest statistical support. Numbers indicate parameter estimates from the model. E. Graph showing the relative contribution of proliferation in donor LC to influx (with 95 percent confidence interval) over time. F. Graph showing the estimated mean interdivision time (with 95 percent confidence interval) of donor LC at different times post-BMT with T cells. Parameter estimates are displayed in full in Table 1. G. Mice received EdU 3 weeks after BMT with T cells. 4 hours later, the skin and blood were harvested and cells analyzed for incorporation of EdU. Representative contour plots show overlaid gated CD11b+Langerinneg (yellow) or CD11b+Langerin+ (magenta) populations in the epidermis, or Ly6C+CD115+ monocytes in the blood. FMO is the fluorescent minus one stain without the EdU detection reagent. H. Summary graph showing the mean ± SD frequency of EdU+ cells in the different groups. Circles are individual mice, n=6. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments. Mo. = blood monocytes, dLC = donor LC.

Table 1:

Parameter estimates from the best-fitting model describing the linear flow from incoming monocytes to CD11bhigh cells, EpCAM+ cells and to mature donor LC. Data show the estimated value with 95% confidence interval (CI).

| Parameter | Estimate | 95% Cl | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean time spent in EpCAM+ | 0.10 days | 0.0084 – 0.30 | |

| Efficiency of maturation from EpCAM+ to donor LC | 0.042 | 0.0068 – 0.053 | |

| Mean residence time of donor LC | 73 days | 14– 1100 | |

| Mean interdivision time in donor LC at week 1 | 5.8 days | 2.4 – 14 | |

| ‘‘ | week 2 | 6.8 days | 4.9–16 |

| ‘‘ | week 3 | 18 days | 14–66 |

| ‘‘ | week 4 | 54 days | 32 – 250 |

| ‘‘ | week 10 | 78 days | 44–370 |

| Relative contribution of proliferation in donor LC to influx at week 1 | 1.4 | 0.84– 11 | |

| ‘‘ | week 2 | 0.22 | 0.15–0.86 |

| ‘‘ | week 3 | 0.24 | 0.16–0.74 |

| ‘‘ | week 4 | 0.31 | 0.18– 1.06 |

| ‘‘ | week 10 | 13 | 7–44 |

Production of donor LC was initially dominated by recruitment from CD11bhigh and EpCAM+ cells but proliferative self-renewal replaced recruitment by week 10 when the mature LC pool had reached steady state (Figure 5E; Table 1). At this point, donor LC resided in the skin for approximately 10 weeks on average and divided once every 78 days (Table 1). These estimates were consistent with other observations of the rates of turnover and division of eLC in the steady state (10), and matched eLC doubling time within the unperturbed eLC network (12, 48). Fits were based on the assumption that the CD11b+ and EpCAM+ cells died or differentiated at a constant per cell rate. However, we had to include density-dependent proliferation of donor LC in order to explain the waning of Ki67+ cells over time. Thus, division occurred more frequently at low cell densities (Figure 5F; Table 1).

Expression of Ki67 by CD11bhigh cells suggested that accumulation of LC precursors required local proliferation of undifferentiated cells. This hypothesis was supported by the over-representation of cell cycle pathways in EpCAM+ cells (Figure S4C). This gene signature was in contrast to dermal monocytes, which up-regulated pathways associated with innate receptors and T cell activation (Figure S4D). To pinpoint active cell division within epidermal cells in vivo, we injected EdU into mice 3 weeks after BMT with T cells, and analyzed the frequency of EdU+ cells 4 hours later. Within this window, we detected incorporation of EdU by cycling CD11b+EpCAMneg cells in the epidermis, and less so in donor LC (Figures 5G and H).

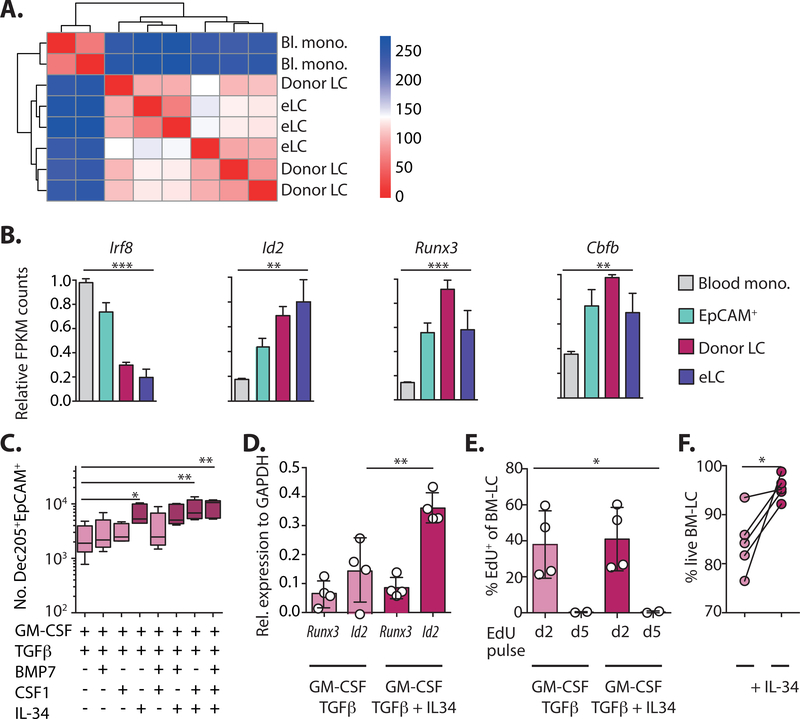

Long-term mLC are homologous eLC and up-regulate Id2.

To determine how much of the eLC transcriptional profile was determined by origin we compared the transcriptional profiles of long-term (10 weeks) mLC and eLC from age-matched untreated mice in more detail. Correlation analysis and direct comparison of gene expression as a heat map demonstrated that donor mLC were virtually indistinguishable from eLC (Figure 6A and S5A), and the few up-regulated genes were dominated by functions associated with cell adhesion and motility, suggesting the positioning and establishment of mLC within the epidermis (Table S2). To understand whether emergence of long-term mLC depended on restoration of a steady state environment in the epidermis, we also compared eLC and donor mLC 3 weeks post-transplant, at which point chimerism was incomplete and both populations shared the same inflammatory environment. We again found that donor mLC were homologous to eLC (Figure S5B), but that eLC showed evidence of prolonged exposure to the inflammatory environment due to conditioning and T cell damage (Figure S5C). Consistent with this, eLC isolated from the epidermis 3 weeks post-transplant primed CD8 T cells more efficiently than donor mLC from the same environment (Figure S5D).

Figure 6. Long-term LC are homologous to eLC and up-regulate Id2.

A. Correlation matrix comparing differentially expressed genes between and blood monocytes, mLC 10 weeks post-BMT + T cells, and eLC from age-matched controls. B. Graphs show the relative FPKM count normalized to the maximum value for different transcription factors from the RNAseq data. Significance was calculated with a 1-way ANOVA, blood Ly6C+ monocytes n = 2, epidermal EpCAM+ cells n= 3, donor LC n = 3, age-matched eLC n = 3. C. BM cells were cultured for 6 days with GM-CSF, TFGβ and different combinations of BMP7, CSF1 and IL-34. Box and whiskers graph shows mean ± min. to max. numbers of DEC205+EpCAM+ cells in the cultures. Significance was calculated with a 1-way ANOVA for non-parametric samples with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Each symbol is data from one culture, n = 5 independent BM donors, in 3 independent experiments. D. The bar graph shows the mean expression ± SD of Runx3 or Id2 relative to GAPDH in sorted DEC205+EpCAM+ cells. Symbols are cells from 4 independent BM donors, in 3 independent experiments. Id2 expression in LC generated in the absence versus the presence of IL-34 was analyzed by paired t-test. E. Bar graph shows the mean frequency ± SD of EdU+ cells on day 6 of culture after cells where pulsed with EdU for 24 hours on day 2 or day 5. Symbols are cells from independent cultures (n = 2–4). Data was analyzed using a 1-way ANOVA. F. Line graph shows the frequency of viable DEC205+EpCAM+ LC in GM-CSF / TGFβ cultures with, or without, IL-34. Symbols represent paired individual BM cultures, and were analyzed using a paired t-test, n = 5. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Given that monocyte-derived cells rapidly differentiated into quiescent, long-lived LC, we reasoned that this must require programming by lineage-defining transcription factors (LDTF), namely Runx3 and Id2 in LC. Thus, we first assess expression these genes in donor mLC and their precursors. Figure 6B shows the sequential up-regulation of Runx3, Id2 and Cbfβ2 (41), and down-regulation of monocyte-associated Irf8, as the cells became mLC. In addition, EpCAM+ cells showed evidence of early responsiveness to the dominant epidermal cytokine TGFβ (Figure S5E), and matured into LC-like cells upon culture with TGFβ ex vivo (Figure S5F). Therefore, these data suggested that LDTF, and responsiveness to TGFβ, are switched on in EpCAM+ cells within the epidermal environment, before differentiation into mature LC. We next used an in vitro screen to identify the growth factors, in addition to TGFβ, that controlled Id2 expression and LC identity after differentiation from BM cells. We selected BMP7, CSF-1 and IL-34 based on expression of their cognate receptors (BMPR1a and CSF1R respectively) by EpCAM+ cells in vivo (Figure S5G) and their requirement for LC repopulation after UV-irradiation (43, 49, 50), and tested the impact of each factor on LC development in BM cultures (Figure S6) (20, 41, 51). IL-34, but not CSF-1 or BMP7 enhanced LC numbers (Figure 6C), and this was associated with the specific up-regulation of Id2 by LC in IL-34 cultures (Figure 6D). BM-LC were derived from cells that proliferated before maturation in these cultures (Figure 6E), mirroring cycling of CD11bhigh cells in the epidermis. Cell division was not affected by addition of IL-34, which instead increased the survival of LC (Figure 6F).

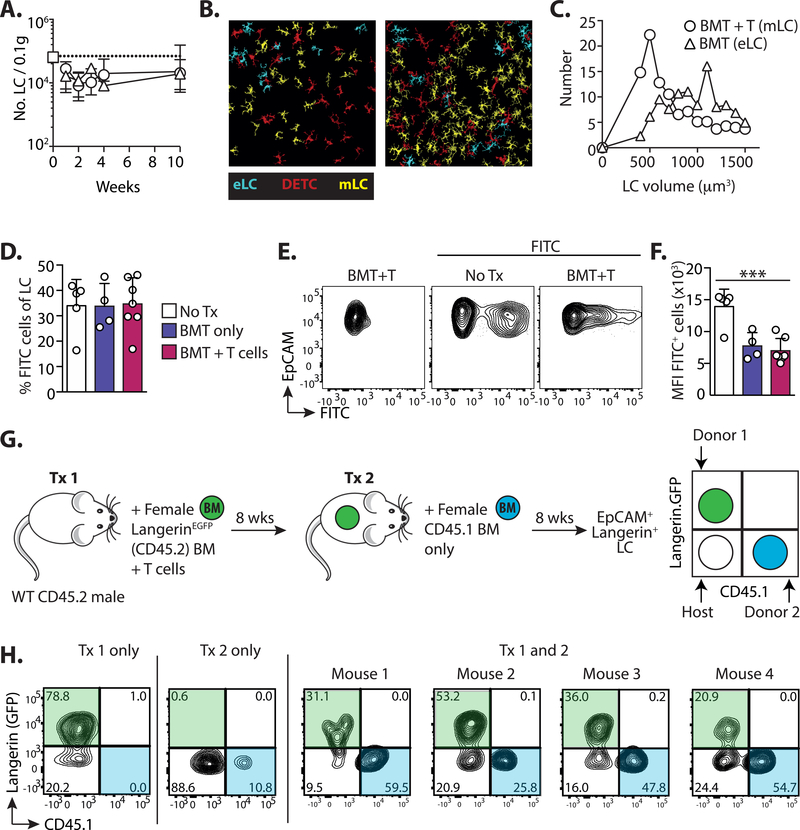

Immune damage and loss of eLC opens the epidermal compartment.

Having considered LC repopulation at the cellular level, and demonstrated that monocytes differentiate into bona fide LC within the epidermis, we now considered the impact of immune pathology on the LC network and integrity of the epidermal compartment.

The kinetics of LC repopulation demonstrated that monocytes failed to completely replenish the LC network in most mice 10 weeks after transplant, suggesting a prolonged reduction in LC density. However, this decrease in LC numbers was also evident in mice that had received BMT alone, demonstrating that the slow-rate of division by mature LC ultimately dictated the speed at which the network was repaired, rather than LC origin. (Figure 7A). Confocal analysis of epidermal sheets revealed significant heterogeneity in the density of mLC in different fields of view (Figure 7B), but mLC tended to be smaller than eLC from BMT controls (Figures 7C). Notably, while mLC and dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) were closely co-located within the epidermis, we found no difference in the frequency of mLC 3 weeks after BMT into Tcrbd−/− recipients that lacked all endogenous T cells (Figure S7A).

Figure 7. Immune damage and loss of eLC opens the epidermal compartment.

Male mice received BMT with or without T cells. A. Graph shows the number ± SD of total CD11b+Langerin+ LC in mice receiving BMT alone (triangles) or BMT with T cells (circles). Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n=5–13). The white square and dotted line shows LC numbers ± SD in untreated controls (n=5). B-C. Epidermal sheets were stained with anti-Langerin and anti-CD45.2, and confocal images processed and quantified using the Definiens Developer software: eLC (cyan) are Langerin+CD45.2+; DETC (red) LangerinnegCD45.2+; and mLC (yellow) are Langerin+CD45.2neg. B. shows example images from mice receiving BMT + T cells, and the graph in C. is the volume of mLC compared to eLC from BMT controls. Data are from 1 transplant experiment with 3 BMT (20 fields of view analyzed) and 2 BMT+T cell recipients (14 fields of view analyzed) (n= 162 cells from BMT mice and 356 LC from BMT+ T cell recipients). D-F. Topical FITC was painted on the ear skin of control un-transplanted mice (No Tx), or BMT and BMT + T cell recipients 10 weeks post-transplant. 3 days later uptake of FITC was analyzed within MHCIIhighEpCAM+Langerin+ LC in draining LN. D. Bar graph showing the frequency ± SD of FITC+ cells within LC. E. Representative contour plots show FITC uptake in gated LC. F. Bar graph showing the FITC median fluorescent intensity ± SD within FITC+ LC. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n=4–7), significance was analyzed using a 1-way ANOVA, ***P<0.001. G. BMT + T cell recipients received a second round of irradiation and BMT alone 8 weeks later. The schematic illustrate the experimental set-up. H. Flow plots show the outcome in the epidermis of independent mice, who have received the 1st transplant only (Tx 1), the 2nd transplant only (Tx 2) or both transplants (Tx 1 and 2). Contour plots are pre-gated on EpCAM+Langerin(PE-labelled)+ LC.

Given the smaller volume of mLC, we considered whether they were less integrated within the epidermis than eLC, and therefore migrated more readily in draining LN. To test this we topically applied FITC to the ear of mice that had received BMT 10 weeks earlier, with or without T cells. LN cells were divided into migratory and resident populations based on expression of CD11c and MHC II as published by others (40, 52, 53) and we determined the number of EpCAM+Langerin+ LC in the migratory gate (Figure S7B). At this time point all migrating LC were derived from donor BM (Figure S7B), and therefore we compared their frequency to that of host eLC in mice that had received BMT without T cells. The frequency of FITC+ cells within LN LC was equivalent irrespective of LC origin (Figure 7D), demonstrating that, while donor mLC acquired the capacity to migrate to LN, this was not to a greater extent than eLC. It was evident from flow cytometry plots that mLC picked up less FITC that eLC from un-transplanted controls. Comparison of the median intensity of FITC+ cells demonstrated that this was indeed the case, but a similar effect was also observed by eLC in BMT controls (Figure 7E and F). Thus, mLC migrate to LN, but irradiation and BMT may also impact on the acquisition of topical antigen by LC.

We next considered how changes to the density of the LC network would impact on the entry of cells into the epidermis in absence of T cell-mediated injury. Thus, transplanted mice received a second round of total body irradiation with BMT (without T cells) and we tracked the origin of epidermal LC 8 weeks later (Figure 7G). Host eLC were replaced by donr mLC after BMT with T cells (Tx1 only), but not BMT alone (Tx2 only), as expected. However, the epidermis of mice that had received both transplants (Tx1 and 2) contained 3 populations of co-existing LC. These were identified as radio-resistant host eLC and donor mLC (Figure 7H Langerin.GFPnegCD45.1neg and Langerin.GFP+CD45.1neg respectively) and new BM-derived LC (Langerin.GFPnegCD45.1+)

Discussion

We show that monocytes are recruited into the epidermis to replenish the LC network after T cell-mediated killing of eLC. We have used a murine model of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation and graft-versus-host disease to determine the mechanisms by which the resident LC network is replenished after T cell-mediated pathology in the epidermis. In this setting, monocytes become quiescent, self-renewing cells, that we have called monocyte-derived LC (mLC), and which acquire the capacity to migrate to draining LN. mLC are transcriptionally homologous to the eLC they replace, despite on-going T cell-mediated immune pathology in the epidermis. This finding suggests that the skin environment is atypical since monocytes that differentiate within other inflamed tissues remain transcriptionally distinct from their resident macrophage counterparts (33, 34), and microglia, which closely resemble LC in terms of their capacity to self-renew without contribution from circulating monocytes, are replaced by cells that retain a persistent monocytic signature (32).

Tissue-resident macrophages, including LC, are seeded from embryonic precursors before birth (5). While there is a clear consensus on the role of adult monocytes in maintaining and replenishing tissue macrophages in other organs, the nature of the precursor that repopulates LC in the skin has remained elusive and controversial. Previously, studies that addressed the nature of LC replacement in the epidermis have depended on the destruction of resident eLC by acute (15–30 minutes) exposure of ear skin to UV irradiation. However, these studies have produced conflicting data on whether Gr1+ monocytes persist in the epidermis of UV-treated mice to become LC (17)(18). This work has led to the concept that an alternative ‘long-term’ LC precursor was required to replenish the LC network after UV-induced damage, and studies using human cells have since invoked a role for blood DC as LC precursors (24, 25). By contrast, in our stem cell transplant model allogeneic T cells are recruited to the epidermis over a period of weeks, resulting in prolonged immune pathology and inflammation (35). Under these conditions monocytes can become long-term LC, and DC precursors do not contribute to the emerging LC network. It is conceivable that transient exposure to UV irradiation compared to the prolonged inflammation caused by allo-reactive T cells may trigger different mechanisms of LC repopulation in the skin. However, the adoptive transfer experiments previously used to define monocytes as LC precursors after UV irradiation are challenging, and require injection of large numbers of cells into Ccr2−/−Ccr6−/− mice to reduce competition from endogenous cells (17, 18). We suggest that the physiological recruitment of monocytes from the BM in our model has revealed their role in the repair of the damaged eLC network after immune pathology.

Statistical analysis of our mathematical models favors the linear differentiation of CD11bhigh monocytes into EpCAM+ precursors of mLC. However, this conclusion is specific to the models that we considered; the transient nature of the EpCAM+ population and similar kinetics of CD11bhigh and EpCAM+ cells mean that it remains possible that the branched pathway may also occur with EpCAM+ cells as a developmental endpoint. We think this is unlikely based on our evidence that EpCAM+ cells express an intermediate phenotype and LDTF compared to CD11bhigh monocytes and mLC, and culture of EpCAM+ cells induces up-regulation of Langerin. Despite the surge of monocytes entering the epidermis, and proliferation of CD11bhigh cells in situ, we have identified a bottleneck with only 4% of CD11bhigh/EpCAM+ cells becoming mLC. The reasons for this inefficiency remain to be determined. One possibility is that monocyte differentiation is an intrinsically inefficient process and may also occur for the generation of tissue-resident macrophages at other sites. Alternatively, monocyte-derived EpCAM+Langerinneg cells can be identified within the oral mucosa, wherein inflammation blocks the transition to mucosal LC (13, 54). Therefore, it is possible that continued inflammation in our model blocks differentiation of EpCAM+ cells.

Entry of CD11bhigh cells into the epidermis triggers a burst of proliferation that has also been reported when phagocytic monocytes enter the skin after UV-irradiation (17). Subsequent to this, mLC divide at a rate that matches that of steady state eLC (12, 48). This concordance both validates our modeling approach, and reveals a developmental convergence of quiescent mLC with their embryonic counterparts. It has been suggested that the density of tissue macrophage populations is controlled by mechanisms of quorum sensing in response to CSF-1 (55), but this has not been directly demonstrated experimentally. We found that density-dependent proliferation was required to fit mathematical models to our data, supporting the concept of quorum sensing within the epidermal niche. CSF1 and IL-34 compete for the CSF1 receptor (56). Given the dominance of IL-34, rather than CSF1 in the epidermal environment (57), and our in vitro data showing that IL-34 increases expression of Id2 and promotes BM-LC survival, it is possible that IL-34 fulfills this function in the skin.

We have shown that the epidermal compartment is not resealed after immune-mediated destruction of eLC, and BM-derived cells continue to be recruited into the epidermis. It is notable that small numbers of donor CD11b+ cells constitutively enter the epidermis of transplanted mice in the steady state, as observed 10 weeks post-transplant (see Figure 3D). One possibility is that the inefficient repair of the mLC network reduces competition between established and incoming cells (55). In this sense, the LC network in the epidermis more closely resembles that of the oral mucosa (1, 13) after exposure to immune injury.

The activation of auto- or allo-reactive T cells, and destruction of tissue-resident cells can have profound impacts on the balance of immune cells within tissue compartments with long-term consequences for the control of infection and cancer at these sites. The skin is highly sensitive to such changes and is a major target organ for T cells in patients suffering from graft-versus-host disease following HSCT, and those receiving immune checkpoint blockade (58). However, we know little about the impact of immune injury in these patients on the regulation of immunity in the skin. Here we provide insights into the cellular mechanisms by which the LC compartment is replenished and maintained after damage, and demonstrate that immune injury triggers an adaptive process that converges closely with mechanisms to regenerate other tissue-resident myeloid cells.

Materials and Methods

Study design.

The aim of this study was to define the nature of long-term repopulating LC, and to identify the cellular processes by which the network was repaired after immune injury. We used an in vivo model of LC replacement and measured changes to cell populations using flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. This was combined with mathematical modeling of the flow between epidermal populations, and RNA sequencing to determine changes in gene expression. Sample sizes were based on previous experiments, and the availability of genetically engineered donors. No outliers were excluded and the number of replicates and independent experiments is given in each figure. There was no randomization or blinding. Recipients were co-housed were possible.

Mice.

C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Charles River and bred in house by the UCL Comparative Biology Unit. Langerin.DTR.EGFP mice (59) were originally provided by Adrian Kissenpfennig and Bernard Malissen. C57BL/6 TCR-transgenic anti-HY MataHari mice (60) were provided by Jian Chai (Imperial College London, London, UK). Ccr2−/− mice were a gift from Frederic Geissmann (61). All strains were bred in house at UCL. TCRbd−/− mice were generated by crossing Tcrd−/− (62) and Tcrb−/− (63) lines, and bred in house at Imperial College London Hammersmith campus. CD45.1+ OT-I TCR transgenic mice were bred in house. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedure) Act of 1986, and were approved by the Ethics and Welfare Committee of the Comparative Biology Unit, Hampstead Campus, UCL, London, UK.

Bone marrow transplants.

Recipient male CD45.2 B6 mice were lethally irradiated (11 Gy total body irradiation, split into 2 fractions over a period of 48 hours) and reconstituted 4 hours after the second dose with 5×106 female CD45.1 C57BL/6 T cell-depleted BM cells and 2×106 CD4 T cells, with 1×106 CD8 Thy1.1+ Matahari (Mh) T cells, administered by intravenous injection through the tail vein. CD4 and CD8 T cells were isolated by magnetic selection of CD4 or CD8 BM cells or splenocytes using the Miltneyi MACS system (QuadroMACS Separator, LS columns, CD4 [L3T4] MicroBeads, CD8a [Ly-2] MicroBeads; Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, either to be discarded from T cell-depleted BM, or selected for injection of splenic T cells. In some experiments Langerin.DTR.EGFP recipients or BM donors were used to track Langerin+ host or donor LC respectively.

For secondary irradiation experiments, BMT recipients initially received BM from Langerin. DTR.GFP donors with CD4 and CD8 Mh T cells. 8 weeks later, mice received 11 Gy split dose total body irradiation and CD45.1+ C57BL/6 female T cell-depleted BM alone.

Mixed chimera experiments.

BM from Vav-Cre.Rosa26LSLTomato and Clec9a-Cre.Rosa26LSL EYFP donors was a gift from Caetano Reis e Sousa (Francis Crick Institute). Irradiated B6 male mice received a 50:50 mix of BM from the reporter mice with T cells. For CCR2 competitive chimeras, irradiated CD45.2+ Langerin-DTR.EGFP recipients received a 50:50 mix of CD45.2+ Ccr2+/+ and CD45.1+ Ccr2−/− BM with T cells.

FITC painting.

The dorsal side of ear pinna were coated with 25\μl of a 1:1 mixture of 0.5% FITC (Fluorescein isothiocyanate, Sigma-Aldrich, UK) in acetone and dibutyl phthalate (Sigma-Aldrich, UK). 72 hours later the draining auricular and cervical LN were harvested and analyzed.

Generation of tissue single cell suspensions.

Epidermal single cell suspensions were generated as described (35). Split dorsal and ventral sides of the ear pinna were floated on 2.5mg/ml Dispase II (Roche) in HBSS 2% FBS for 15 hours at 4°C, followed by mechanical dissociation of the epidermal layer in PBS/1mM EDTA/1% FBS by mincing with scissors or using the GentleMACS tissue dissociator (Miltneyi Biotech). Epidermal cells were passed sequentially through 70μM and 40μM cell strainers to remove clumps of cells. Numbers of cells were calculated by addition of counting beads (Invitrogen) before staining of samples for flow cytometry, and normalized to 0.1g weight for both complete ears before processing. After separation from the epidermis, the dermis was minced into small pieces and digested with 250 U/ml collagenase IV (Worthington, USA) and 800U/ml DNaseI (AppliChem, USA) at 37°C for 1 hour. Dermal single cell suspensions were then generated using the GentleMACS tissue dissociator (Miltneyi Biotech).

LN were teased apart with needles and digested in HBSS/4000U/ml Collagenase IV (Worthington) for 40 min at 37°C. Digestion was quenched with 10mM EDTA, and the cells were passed through a 40 μM cell strainer, washed, and resuspended in PBS/1mM EDTA/1% FBS.

For blood cells, erythrocytes were removed by hypotonic lysis with distilled water, and cells then resuspended in PBS/1mM EDTA/1% FBS.

Bone marrow cultures.

BM was flushed from femurs and tibias of donors, and red blood cells lysed in 1ml ammonium chloride (ACK buffer, Lonza UK) for 1 minute at room temperature. Cells were washed and resuspended at 2.5×106/ml in R5 medium (RPMI 1640, Lonza, Switzerland), 5% heat-inactivated FBS (Life Technologies, USA), 1% L-glutamine (2 mM; Life Technologies, USA), 1% Pen-strep (100 U/ml Life Technologies, USA) and 50μM β-ME (Sigma-Aldrich, UK). 1ml of cell suspension was plated per well in tissue culture-treated 24 plates and supplemented with 20ng/ml recombinant GM-CSF and 5ng/ml TGFβ (Peprotech, USA). Cells were cultured at 37°C. Media was partially replaced on day 2 of culture, completely replaced on day 3, and the cells harvested on day 6. Some cultures were supplemented with combinations of 8μg/ml IL-34 (Generon, UK), 100 μg/ml BMP7 (R&D systems, USA and 10μg/ml CSF-1 (Biolegend, USA) for the duration of the culture.

Flow cytometry.

Cells were distributed in 96 well conical bottom plates and incubated in 2.4G2 hybridoma supernatant (containing αCD16/32) for at least 10 min at 4°C to block Fc receptors. For cell surface labeling, cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies diluted in 100μl FACS buffer (PBS/1mM EDTA/1% FBS) at 4°C for at least 20 min in the dark: EpCAM (G8.8, eBioscience, USA), CD11b (M1/70, eBioscience, USA), CD45.1 (A20, BD Biosciences, Germany), CD45.2 (104, eBioscience, USA), MHC II I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2, eBioscience, USA), CD11c (HL3, BD Pharmingen, USA), CD24 (M1/69 BD Biosciences or Biolegend), CD205 (205yekta, eBioscience), B220 (RA3–6B2, BD Biosciences), Vβ8.3 TCR (1B3.3, BD Biosciences, Germany). To exclude lineage+ cells, we used a cocktail of CD3 (145–2C11, BD Biosciences, Germany), CD19 (1D3BD Biosciences, Germany), NK1.1 (PK136, Biolegend) and Ly6G (1A8, BD Biosciences, Germany) all conjugated to APC-Cy7.

Intracellular staining with αLangerin (CD207) antibodies (eBioL31, eBioscience, USA) was performed after cell surface immunolabeling. Samples were washed with FACS buffer, fixed in 100μl fixation solution (BD Cytofix/Cytoperm solution, BD Biosciences, UK) for 15 min at 4°C, washed twice with permeabilization buffer (BD Perm/Wash, BD Biosciences, UK) and incubated with 100μl αLangerin diluted in permeabilization solution at 4°C for 30 min in the dark.

Live cells were identified by exclusion of propidium iodide (unfixed cells) (Life Technologies, USA), or a fixable viability dye (eBioscience, USA or Life Technologies, USA). Multicolor flow cytometry data were acquired with BD LSRFortessa and BD LSR II cell analyzers equipped with BD FACSDiva v6.2 software (BDBiosciences, Germany). Fluorescence activated cell sorting was performed on a BD FACSAria equipped with BD FACSDiva v5.0.3 software (BD Biosciences, Germany). All samples were maintained at 4°C for the duration of the sort. Cells were sorted into PBS/2% FBS before resuspension in Buffer RLT (QIAGEN, USA) or directly into Buffer RLT with 1% 2-β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, UK), disrupted through vortexing at 3200 rpm for 1 min, and immediately stored at −80°C until further processing. 2–3 biological replicates were obtained for each sample from at least 2 independent experiments, each containing a minimum of 4000 cells (pooling where necessary from multiple mice from individual experiments). Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo X v9 and 10 (LLC, USA), and cells were pre-gated on singlets (FSC-A versus FSC-H), and a morphological FSC/SSC gate.

Measurement of cell proliferation.

In vivo. Epidermal single cell suspensions were immuno-labeled with surface antibodies, then fixed and permeabilized using the eBioscience intra-nuclear staining kit, before incubation with αKi67-v450 antibodies (SolA15, eBioscience, USA). Gates were set on non-proliferating cells and unstained cells. Alternatively, mice were injected with 100μg 5-Ethynyl-2´-deoxyuridine (EdU) i.p (Invitrogen, USA) and euthanized 4 hours later. In vitro. Cells were pulsed with 10μM EdU on day 2 or day 5 of culture and the medium replaced 24 hours later. For both in vivo and in vitro studies, cells were labeled for flow cytometry using the Click-iT Plus EdU Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Invitrogen, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry.

4mm biopsy punches were excised from the dorsal and ventral sides of split ears and incubated in 0.5M ammonium thiocyanate for 30 min at 37°C to remove the epidermis. Epidermal sheets were collected in eppendorf tubes, washed twice with PBS, and fixed with cold (stored at −20°C) acetone for 10 min. Sheets were washed twice with PBS, and blocked using 0.25% fish gelatin, 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Sheets were then incubated with primary rat αLangerin (eBioscience), and αCD45.2-biotin (eBioscience) antibodies (both diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer), and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Sheets were washed 4 times in PBS, and incubated with goat αRat-Alexa 647 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, 1:1000) and Streptavidin-e570 (eBioscience, 1:200) secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour at room temperature. Stained sheets were washed 4 times with PBS, and mounted on slides with ProLong™ Diamond anti-fade mountant (Invitrogen). Samples were imaged on a Nikon Ti inverted microscope, through a 20X objective for epidermal sheets (Plan Apochromat N.A. 0.75 W.D. 1mm) or 40X for sorted EpCAM+ cells (Plan Apochromat N.A. 0.95 W.D. 0.21mm), using a C2 confocal scan head with488nm and 561/568nm optimized fluorescence filter cubes (Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Multiple Z-stacks were acquired for each sample. Data was saved as nd2 files using FIJI/ImageJ for quantification.

Confocal analysis.

Quantification of confocal records was performed using Definiens Developer software. Each channel in a record was processed with Gaussian filter followed by application of multi-resolution segmentation. Individual cells were detected based on their relative intensity in Langerin and CD45.2 channels. The cell volume (μm3 based on total number of voxels occupied by a cell) was measured for each cell type.

Statistics.

All data, apart from RNAseq data, were analyzed using GraphPad Prism Version 6.00 for Mac OsX (GraphPad Software, USA). All line graphs and bar charts are expressed as means ± SD. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA to measure a single variable in 3 groups, or two-way ANOVA for experiments with more than 1 variable, with post-tests as specified in individual figures. A paired t-test was used in figure 6 to compare cells cultured under different conditions. Significance was defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The false discovery rate (fdr) was used to compare ontogeny pathways enriched in dermal or epidermal cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the UCL Comparative Biology Unity for their support with animal work, and UCL Genomics for performing the RNA sequencing. We are grateful to Caetano Reis e Sousa for providing BM from Clec9a and Vav reporter mice, to Joe Grove and Benedict Seddon for constructive discussions during this work, and Hans Stauss for his support.

Funding: This work was supported by a BBSRC project grant (BB/L001608/1) and Royal Free charity funding (award 174418) to C.L.B., a Bloodwise programme continuity grant (17007) to R.C. and C.L.B., an MRC PhD studentship (1450227) to H.W. and the NIH (R01 AI093870) for A.J.Y. D.U. acknowledges the support of the Wellcome Trust (grant 100156), and the Infection and Immunity Immunophenotyping (3i) Consortium.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: The RNA sequencing data for this study have been deposited at NCBI Gene expression omnibus, GSE130257.

Supplementary materials.

Supplemental Materials and Methods including mathematical modeling methods.

References:

- 1.Capucha T, Mizraji G, Segev H, Blecher-Gonen R, Winter D, Khalaileh A, Tabib Y, Attal T, Nassar M, Zelentsova K, Kisos H, Zenke M, Sere K, Hieronymus T, Burstyn-Cohen T, Amit I, Wilensky A, Hovav AH, Distinct Murine Mucosal Langerhans Cell Subsets Develop from Pre-dendritic Cells and Monocytes. Immunity 43, 369–381 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West HC, Bennett CL, Redefining the Role of Langerhans Cells As Immune Regulators within the Skin. Front Immunol 8, 1941 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan DH, Ontogeny and function of murine epidermal Langerhans cells. Nat Immunol 18, 1068–1075 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E., Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, Prinz M, Wu B, Jacobsen SE, Pollard JW, Frampton J, Liu KJ, Geissmann F, A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science 336, 86–90 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mass E, Ballesteros I, Farlik M, Halbritter F, Gunther P, Crozet L, Jacome-Galarza CE, Handler K, Klughammer J, Kobayashi Y, Gomez-Perdiguero E, Schultze JL, Beyer M, Bock C, Geissmann F, Specification of tissue-resident macrophages during organogenesis. Science 353, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeffel G, Chen J, Lavin Y, Low D, Almeida FF, See P, Beaudin AE, Lum J, Low I, Forsberg EC, Poidinger M, Zolezzi F, Larbi A, Ng LG, Chan JK, Greter M, Becher B, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M, Ginhoux F, C-Myb(+) erythro-myeloid progenitor-derived fetal monocytes give rise to adult tissue-resident macrophages. Immunity 42, 665–678 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparber F, Scheffler JM, Amberg N, Tripp CH, Heib V, Hermann M, Zahner SP, Clausen BE, Reizis B, Huber LA, Stoitzner P, Romani N, The late endosomal adaptor molecule p14 (LAMTOR2) represents a novel regulator of Langerhans cell homeostasis. Blood 123, 217–227 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuster C, Vaculik C, Fiala C, Meindl S, Brandt O, Imhof M, Stingl G, Eppel W, Elbe-Burger A, HLA-DR+ leukocytes acquire CD1 antigens in embryonic and fetal human skin and contain functional antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med 206, 169–181 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chorro L, Sarde A, Li M, Woollard KJ, Chambon P, Malissen B, Kissenpfennig A, Barbaroux JB, Groves R, Geissmann F, Langerhans cell (LC) proliferation mediates neonatal development, homeostasis, and inflammation-associated expansion of the epidermal LC network. J Exp Med 206, 3089–3100 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merad M, Manz MG, Karsunky H, Wagers A, Peters W, Charo I, Weissman IL, Cyster JG, Engleman EG, Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol 3, 1135–1141 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chorro L, Geissmann F, Development and homeostasis of ‘resident’ myeloid cells: the case of the Langerhans cell. Trends Immunol 31, 438–445 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghigo C, Mondor I, Jorquera A, Nowak J, Wienert S, Zahner SP, Clausen BE, Luche H, Malissen B, Klauschen F, Bajenoff M, Multicolor fate mapping of Langerhans cell homeostasis. J Exp Med 210, 1657–1664 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capucha T, Koren N, Nassar M, Heyman O, Nir T, Levy M, Zilberman-Schapira G, Zelentova K, Eli-Berchoer L, Zenke M, Hieronymus T, Wilensky A, Bercovier H, Elinav E, Clausen BE, Hovav AH, Sequential BMP7/TGF-beta1 signaling and microbiota instruct mucosal Langerhans cell differentiation. J Exp Med, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett CL, van Rijn E, Jung S, Inaba K, Steinman RM, Kapsenberg ML, Clausen BE, Inducible ablation of mouse Langerhans cells diminishes but fails to abrogate contact hypersensitivity. J Cell Biol 169, 569–576 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poulin LF, Henri S, de Bovis B, Devilard E, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, The dermis contains langerin+ dendritic cells that develop and function independently of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med 204, 3119–3131 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merad M, Hoffmann P, Ranheim E, Slaymaker S, Manz MG, Lira SA, Charo I, Cook DN, Weissman IL, Strober S, Engleman EG, Depletion of host Langerhans cells before transplantation of donor alloreactive T cells prevents skin graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med 10, 510–517 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ginhoux F, Tacke F, Angeli V, Bogunovic M, Loubeau M, Dai XM, Stanley ER, Randolph GJ, Merad M, Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nat Immunol 7, 265–273 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seré K, Baek J, Ober-Blöbaum J, Müller-Newen G, Tacke F, Yokota Y, Zenke M, Hieronymus T, Two Distinct Types of Langerhans Cells Populate the Skin during Steady State and Inflammation. Immunity 37, 905–916 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagao K, Kobayashi T, Moro K, Ohyama M, Adachi T, Kitashima DY, Ueha S, Horiuchi K, Tanizaki H, Kabashima K, Kubo A, Cho YH, Clausen BE, Matsushima K, Suematsu M, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Farber JM, Udey MC, Amagai M, Stress-induced production of chemokines by hair follicles regulates the trafficking of dendritic cells in skin. Nat Immunol 13, 744–752 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chopin M, Seillet C, Chevrier S, Wu L, Wang H, Morse HC 3rd, Belz GT, Nutt SL, Langerhans cells are generated by two distinct PU.1-dependent transcriptional networks. The Journal of experimental medicine 210, 2967–2980 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito T, Inaba M, Inaba K, Toki J, Sogo S, Iguchi T, Adachi Y, Yamaguchi K, Amakawa R, Valladeau J, Saeland S, Fukuhara S, Ikehara S, A CD1a+/CD11c+ subset of human blood dendritic cells is a direct precursor of Langerhans cells. J Immunol 163, 1409–1419 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anjuere F, del Hoyo GM, Martin P, Ardavin C, Langerhans cells develop from a lymphoid-committed precursor. Blood 96, 1633–1637 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mende I, Karsunky H, Weissman IL, Engleman EG, Merad M, Flk2+ myeloid progenitors are the main source of Langerhans cells. Blood 107, 1383–1390 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Cingolani C, Grandclaudon M, Jeanmougin M, Jouve M, Zollinger R, Soumelis V, Human blood BDCA-1 dendritic cells differentiate into Langerhans-like cells with thymic stromal lymphopoietin and TGF-beta. Blood, (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milne P, Bigley V, Gunawan M, Haniffa M, Collin M, CD1c+ blood dendritic cells have Langerhans cell potential. Blood 125, 470–473 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guilliams M, Mildner A, Yona S, Developmental and Functional Heterogeneity of Monocytes. Immunity 49, 595–613 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gosselin D, Link VM, Romanoski CE, Fonseca GJ, Eichenfield DZ, Spann NJ, Stender JD, Chun HB, Garner H, Geissmann F, Glass CK, Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell 159, 1327–1340 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavin Y, Winter D, Blecher-Gonen R, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Merad M, Jung S, Amit I, Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell 159, 1312–1326 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott CL, Zheng F, De Baetselier P, Martens L, Saeys Y, De Prijck S, Lippens S, Abels C, Schoonooghe S, Raes G, Devoogdt N, Lambrecht BN, Beschin A, Guilliams M, Bone marrow-derived monocytes give rise to self-renewing and fully differentiated Kupffer cells. Nat Commun 7, 10321 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Laar L, Saelens W, De Prijck S, Martens L, Scott CL, Van Isterdael G, Hoffmann E, Beyaert R, Saeys Y, Lambrecht BN, Guilliams M, Yolk Sac Macrophages, Fetal Liver, and Adult Monocytes Can Colonize an Empty Niche and Develop into Functional Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Immunity 44, 755–768 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett FC, Bennett ML, Yaqoob F, Mulinyawe SB, Grant GA, Hayden Gephart M., Plowey ED, Barres BA, A Combination of Ontogeny and CNS Environment Establishes Microglial Identity. Neuron 98, 1170–1183 e1178 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cronk JC, Filiano AJ, Louveau A, Marin I, Marsh R, Ji E, Goldman DH, Smirnov I, Geraci N, Acton S, Overall CC, Kipnis J, Peripherally derived macrophages can engraft the brain independent of irradiation and maintain an identity distinct from microglia. J Exp Med 215, 1627–1647 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Machiels B, Dourcy M, Xiao X, Javaux J, Mesnil C, Sabatel C, Desmecht D, Lallemand F, Martinive P, Hammad H, Guilliams M, Dewals B, Vanderplasschen A, Lambrecht BN, Bureau F, Gillet L, A gammaherpesvirus provides protection against allergic asthma by inducing the replacement of resident alveolar macrophages with regulatory monocytes. Nat Immunol 18, 1310–1320 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misharin AV, Morales-Nebreda L, Reyfman PA, Cuda CM, Walter JM, McQuattie-Pimentel AC, Chen CI, Anekalla KR, Joshi N, Williams KJN, Abdala-Valencia H, Yacoub TJ, Chi M, Chiu S, Gonzalez-Gonzalez FJ, Gates K, Lam AP, Nicholson TT, Homan PJ, Soberanes S, Dominguez S, Morgan VK, Saber R, Shaffer A, Hinchcliff M, Marshall SA, Bharat A, Berdnikovs S, Bhorade SM, Bartom ET, Morimoto RI, Balch WE, Sznajder JI, Chandel NS, Mutlu GM, Jain M, Gottardi CJ, Singer BD, Ridge KM, Bagheri N, Shilatifard A, Budinger GRS, Perlman H, Monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages drive lung fibrosis and persist in the lung over the life span. J Exp Med 214, 2387–2404 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santos ESP, Cire S, Conlan T, Jardine L, Tkacz C, Ferrer IR, Lomas C, Ward S, West H, Dertschnig S, Blobner S, Means TK, Henderson S, Kaplan DH, Collin M, Plagnol V, Bennett CL, Chakraverty R, Peripheral tissues reprogram CD8+ T cells for pathogenicity during graft-versus-host disease. JCI Insight 3. pii: 97011. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flutter B, Edwards N, Fallah-Arani F, Henderson S, Chai JG, Sivakumaran S, Ghorashian S, Bennett CL, Freeman GJ, Sykes M, Chakraverty R, Nonhematopoietic antigen blocks memory programming of alloreactive CD8+ T cells and drives their eventual exhaustion in mouse models of bone marrow transplantation. The Journal of clinical investigation 120, 3855–3868 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toubai T, Tawara I, Sun Y, Liu C, Nieves E, Evers R, Friedman T, Korngold R, Reddy P, Induction of acute GVHD by sex-mismatched H-Y antigens in the absence of functional radiosensitive host hematopoietic-derived antigen-presenting cells. Blood 119, 3844–3853 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guilliams M, Dutertre CA, Scott CL, McGovern N, Sichien D, Chakarov S, Van Gassen S, Chen J, Poidinger M, De Prijck S, Tavernier SJ, Low I, Irac SE, Mattar CN, Sumatoh HR, Low GH, Chung TJ, Chan DK, Tan KK, Hon TL, Fossum E, Bogen B, Choolani M, Chan JK, Larbi A, Luche H, Henri S, Saeys Y, Newell EW, Lambrecht BN, Malissen B, Ginhoux F, Unsupervised High-Dimensional Analysis Aligns Dendritic Cells across Tissues and Species. Immunity 45, 669–684 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, Harker N, Coles M, Tolaini M, Norton T, Williams K, Roderick K, Potocnik AJ, Kioussis D, Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol 33, 314–325 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schraml BU, van Blijswijk J, Zelenay S, Whitney PG, Filby A, Acton SE, Rogers NC, Moncaut N, Carvajal JJ, Reis e Sousa C., Genetic tracing via DNGR-1 expression history defines dendritic cells as a hematopoietic lineage. Cell 154, 843–858 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tenno M, Shiroguchi K, Muroi S, Kawakami E, Koseki K, Kryukov K, et al. Cbfbeta2 deficiency preserves Langerhans cell precursors by lack of selective TGFbeta receptor signaling. J Exp Med. 2017;214(10):2933–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Briseno CG, Haldar M, Kretzer NM, Wu X, Theisen DJ, Kc W, et al. Distinct Transcriptional Programs Control Cross-Priming in Classical and Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells. Cell Rep. 2016;15(11):2462–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bain CC, Hawley CA, Garner H, Scott CL, Schridde A, Steers NJ, et al. Long-lived self-renewing bone marrow-derived macrophages displace embryo-derived cells to inhabit adult serous cavities. Nat Commun. 2016;7:ncomms11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamoutounour S, Guilliams M, Montanana Sanchis F, Liu H, Terhorst D, Malosse C, et al. Origins and functional specialization of macrophages and of conventional and monocyte-derived dendritic cells in mouse skin. Immunity. 2013;39(5):925–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schridde A, Bain CC, Mayer JU, Montgomery J, Pollet E, Denecke B, et al. Tissue-specific differentiation of colonic macrophages requires TGFbeta receptor-mediated signaling. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10(6):1387–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ratzinger G, Stoitzner P, Ebner S, Lutz MB, Layton GT, Rainer C, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases 9 and 2 are necessary for the migration of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells from human and murine skin. J Immunol. 2002;168(9):4361–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burnham KPaA DR Model Selection and Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretical Approach. 2nd ed. New YOrk: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vishwanath M, Nishibu A, Saeland S, Ward BR, Mizumoto N, Ploegh HL, et al. Development of intravital intermittent confocal imaging system for studying Langerhans cell turnover. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126(11):2452–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Greter M, Lelios I, Pelczar P, Hoeffel G, Price J, Leboeuf M, et al. Stroma-Derived Interleukin-34 Controls the Development and Maintenance of Langerhans Cells and the Maintenance of Microglia. Immunity. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Szretter KJ, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Rossini C, Cella M, et al. IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nature immunology. 2012;13(8):753–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabib Y, Jaber NS, Nassar M, Capucha T, Mizraji G, Nir T, et al. Cell-intrinsic regulation of murine epidermal Langerhans cells by protein S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(25):E5736-E45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamath AT, Henri S, Battye F, Tough DF, Shortman K. Developmental kinetics and lifespan of dendritic cells in mouse lymphoid organs. Blood. 2002;100(5):1734–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, et al. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21(2):279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heyman O, Koren N, Mizraji G, Capucha T, Wald S, Nassar M, et al. Impaired Differentiation of Langerhans Cells in the Murine Oral Epithelium Adjacent to Titanium Dental Implants. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guilliams M, Scott CL. Does niche competition determine the origin of tissue-resident macrophages? Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17(7):451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barve RA, Zack MD, Weiss D, Song RH, Beidler D, Head RD. Transcriptional profiling and pathway analysis of CSF-1 and IL-34 effects on human monocyte differentiation. Cytokine. 2013;63(1):10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Bugatti M, Ulland TK, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. Nonredundant roles of keratinocyte-derived IL-34 and neutrophil-derived CSF1 in Langerhans cell renewal in the steady state and during inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(3):552–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kissenpfennig A, Henri S, Dubois B, Laplace-Builhe C, Perrin P, Romani N, et al. Dynamics and function of Langerhans cells in vivo: dermal dendritic cells colonize lymph node areas distinct from slower migrating Langerhans cells. Immunity. 2005;22(5):643–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valujskikh A, Lantz O, Celli S, Matzinger P, Heeger PS. Cross-primed CD8(+) T cells mediate graft rejection via a distinct effector pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(9):844–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boring L, Gosling J, Chensue SW, Kunkel SL, Farese RV Jr., Broxmeyer HE, et al. Impaired monocyte migration and reduced type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses in C-C chemokine receptor 2 knockout mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100(10):2552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Itohara S, Mombaerts P, Lafaille J, Iacomini J, Nelson A, Clarke AR, et al. T cell receptor delta gene mutant mice: independent generation of alpha beta T cells and programmed rearrangements of gamma delta TCR genes. Cell. 1993;72(3):337–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mombaerts P, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Tonegawa S. Creation of a large genomic deletion at the T-cell antigen receptor beta-subunit locus in mouse embryonic stem cells by gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(8):3084–7.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L, Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol 34, 525–527 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD, Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res 4, 1521 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ignatiadis N, Klaus B, Zaugg JB, Huber W, Data-driven hypothesis weighting increases detection power in genome-scale multiple testing. Nat Methods 13, 577–580 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP, Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdottir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP, Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 27, 1739–1740 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hogan T, Gossel G, Yates AJ, Seddon B, Temporal fate mapping reveals age-linked heterogeneity in naive T lymphocytes in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, E6917–6926 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gossel G, Hogan T, Cownden D, Seddon B, Yates AJ, Memory CD4 T cell subsets are kinetically heterogeneous and replenished from naive T cells at high levels. Elife 6, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.