Abstract

Ancient DNA (aDNA) sequencing has enabled reconstruction of speciation, migration, and admixture events for extinct taxa1. Outside the permafrost, however, irreversible aDNA post-mortem degradation2 has so far limited aDNA recovery to the past ~0.5 million years (Ma)3. Contrarily, tandem mass spectrometry (MS) allowed sequencing ~1.5 million year (Ma) old collagen type I (COL1)4 and suggested the presence of protein residues in Cretaceous fossil remains5, although with limited phylogenetic use6. In the absence of molecular evidence, the speciation of several Early and Middle Pleistocene extinct species remain contentious. In this study, we address the phylogenetic relationships of the Eurasian Pleistocene Rhinocerotidae7–9 using a ~1.77 Ma old dental enamel proteome of a Stephanorhinus specimen from the Dmanisi archaeological site in Georgia (South Caucasus)10. Molecular phylogenetic analyses place the Dmanisi Stephanorhinus as a sister group to the woolly (Coelodonta antiquitatis) and Merck’s rhinoceros (S. kirchbergensis) clade. We show that Coelodonta evolved from an early Stephanorhinus lineage and that the latter includes at least two distinct evolutionary lines. As such, the genus Stephanorhinus is currently paraphyletic and its systematic revision is therefore needed. We demonstrate that Early Pleistocene dental enamel proteome sequencing overcomes the limits of ancient collagen- and aDNA-based phylogenetic inference. It also provides additional information about the sex and taxonomic assignment of the specimens analysed. Dental enamel, the hardest tissue in vertebrates11, is highly abundant in the fossil record. Our findings reveal that palaeoproteomic investigation of this material can push biomolecular investigation further back into the Early Pleistocene.

Phylogenetic placement of extinct species increasingly relies on aDNA sequencing. Efforts to improve the molecular tools underlying aDNA recovery have enabled the reconstruction of ~0.4 Ma and ~0.7 Ma old DNA sequences from temperate deposits3 and subpolar regions12, respectively. However, no aDNA data have so far been generated from species that became extinct beyond this time range. In contrast, ancient proteins represent a more durable source of genetic information, reported to survive, in eggshell, up to 3.8 Ma13. Ancient protein sequences can carry taxonomic and phylogenetic information useful to trace the evolutionary relationships between extant and extinct species14,15. However, so far, the recovery of ancient mammal proteins from sites too old or too warm to be compatible with aDNA preservation is mostly limited to collagen type I (COL1). Being highly conserved16, this protein is not an ideal phylogenetic marker. For example, regardless of endogeneity17, collagen-based phylogenetic placement of Dinosauria in relation to extant Aves appears to be unstable6. This suggests that the exclusive use of COL1 in deep-time molecular phylogenetics is constraining. Here, we sought to overcoming these limitations by testing whether dental enamel can better preserve a richer set of ancient proteins that are preserved longer than COL1.

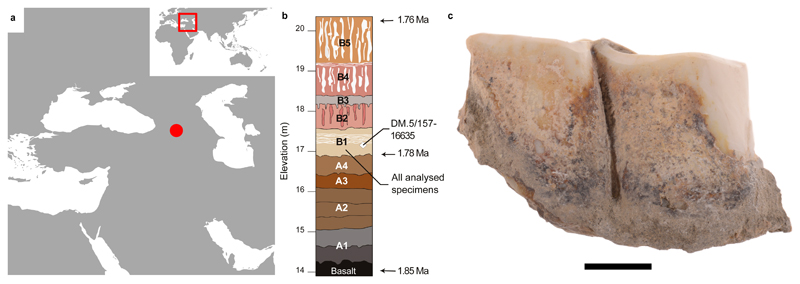

Dated to ~1.77 Ma by a combination of 40Ar/39Ar dating, paleomagnetism and biozonation18,19, the archaeological site of Dmanisi (Georgia, South Caucasus; Fig. 1a) represents a context currently considered outside the scope of aDNA recovery. This site has been excavated since 1983, resulting in the discovery, along with stone tools and contemporaneous fauna (Table S1), of almost one hundred hominin fossils, including five skulls representing the georgicus paleodeme within Homo erectus 10. These are the earliest fossils of the genus Homo outside Africa.

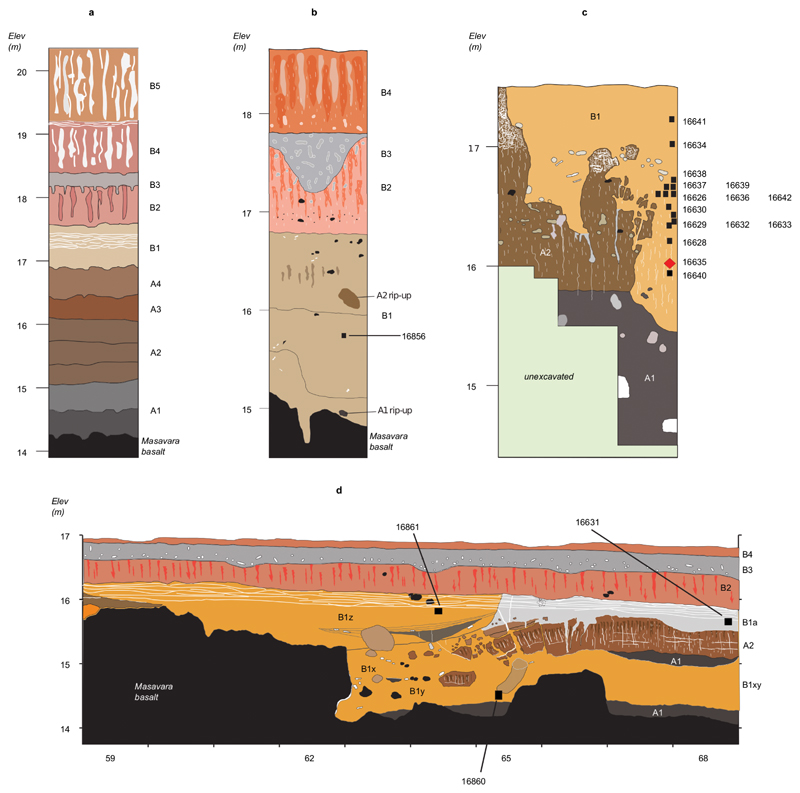

Figure 1. Dmanisi location, stratigraphy, and Stephanorhinus specimen GNM Dm.5/157-16635.

a, Geographic location of Dmanisi in the South Caucasus. The base map was generated using public domain data from www.naturalearthdata.com. b, Generalised stratigraphic profile indicating origin and age of the analysed specimens. c, Isolated left lower molar (m1 or m2) of Stephanorhinus ex gr. etruscus-hundsheimensis, from Dmanisi (labial view). Scale bar: 1 cm.

The geology of the Dmanisi deposits favours the preservation of faunal materials (Supplementary Information: Extended Methods and Results), as the primary aeolian deposits provide rapid burial in fine-grained, calcareous sediments. We studied 12 bone and 14 enamel+dentine samples from 23 specimens of large mammals from multiple excavation units within stratum B1 (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1, Extended Data Table 1, Table S3). This is an ashfall deposit that contains faunal remains in different geomorphic contexts. All of these are firmly dated between 1.85-1.76 Ma19. High-resolution tandem MS was used to confidently sequence ancient protein residues from the set of faunal remains, after digestion-based (protocols A and B), or digestion-free (protocol C), sample preparation (Methods and Supplementary Information). Ancient DNA analysis was unsuccessfully attempted on a subset of five bone and dentine specimens (Methods).

We recovered endogenous proteins from 15 out of 23 studied specimens. Digestion-based peptide extraction from bone, dentine and enamel specimens led to the sporadic recovery (6/19) of a limited number of collagen fragments. In contrast, digestion-free peptide extraction of enamel+dentine and bone specimens resulted in high rates of enamel proteome recovery (13/14 specimens, Extended Data Table 1).

The small proteome20,21 of mature dental enamel consists of structural enamel proteins, i.e. amelogenin (AMELX), enamelin (ENAM), amelotin (AMTN), and ameloblastin (AMBN), and enamel-specific proteases secreted during amelogenesis, i.e. matrix metalloproteinase-20 (MMP20) and kallikrein 4 (KLK4). The presence of non-specific proteins, such as serum albumin (ALB), has also been previously reported in mature dental enamel20 (Extended Data Table 2). The depth of coverage for these proteins varied considerably across their sequence, with some positions covered by over 1000 peptide spectrum matches (Extended Data Fig. 2). The high depth of coverage also allows to identify multiple isoforms of AMELX (Extended Data Fig. 3).

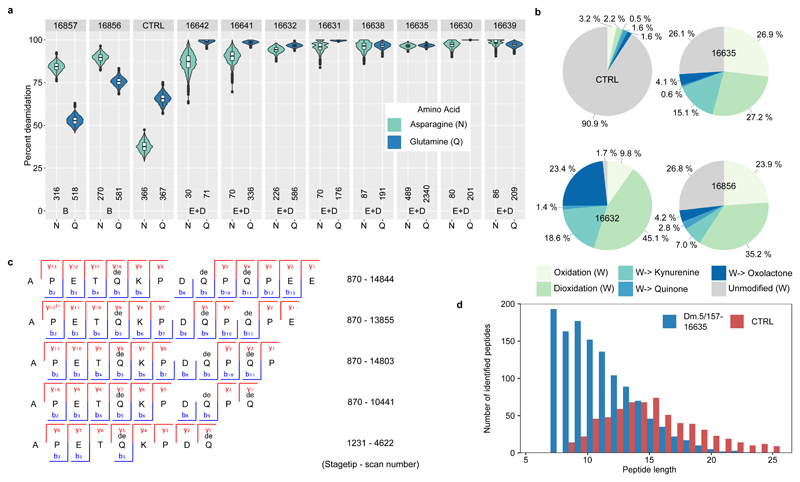

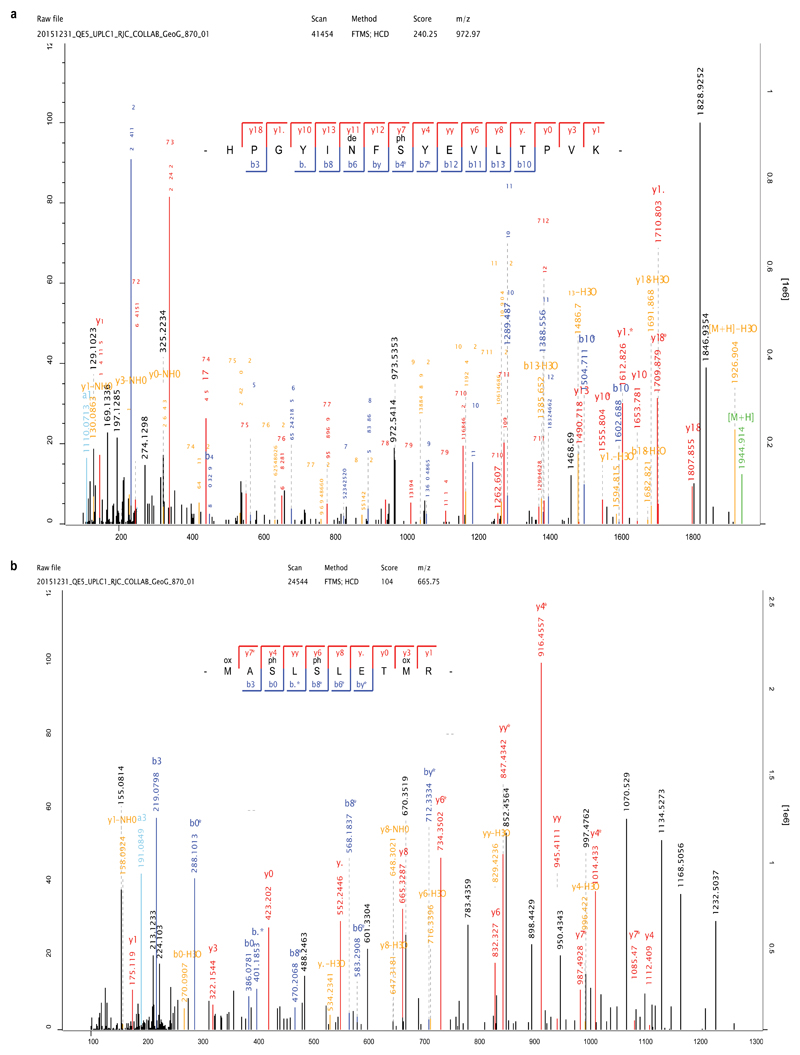

Multiple lines of evidence support the authenticity and the endogenous origin of the sequences recovered. Dental enamel proteins are extremely tissue-specific and confined to the dental enamel mineral matrix20. The amino acid composition of the intra-crystalline protein fraction, measured by amino acid racemisation analysis, indicates that the dental enamel behaves as a closed system, unaffected by amino acid and protein residues exchange with the burial environment (Extended Data Fig. 4). The measured rate of asparagine and glutamine deamidation, a spontaneous form of hydrolytic damage consistently observed in ancient samples22, is particularly advanced. Deamidation in Dmanisi enamel is higher than in the control enamel sample, supporting the antiquity of the peptides recovered (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Information). Other forms of non-enzymatic modifications are also present. Tyrosine (Y) experienced mono- and di-oxidation while tryptophan (W) was extensively converted into multiple oxidation products (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Information). Oxidative degradation of histidine (H) and conversion of arginine (R) leading to ornithine accumulation were also observed (Supplementary Information). These modifications are absent, or much less frequent, in the control sample. Similarly, unlike in the control, the peptide length distribution in the Dmanisi dataset is dominated by shorter fragments, generated by advanced, diagenetically-induced, terminal hydrolysis23 (Fig. 2c, d). Together all these independent lines of evidence clearly define the substantial biomolecular damage affecting the proteomes retrieved and independently support the authenticity of the sequences reconstructed. To demonstrate beyond reasonable doubt the correct peptide sequence assignments of our MS2 spectra, we performed manual validation of peptide-spectrum-matches, conducted fragment ion intensity predictions, and generated synthetic peptides, for a range of phylogenetically informative and phosphorylated peptides (Methods and Supplementary Information: Key MS2 Spectra).

Figure 2. Enamel proteome degradation.

a, Deamidation of asparagine (N) and glutamine (Q). Violin plots based on 1000 bootstrap replicates. The boxplots define the range of the data, with whiskers extending to 1.5 the interquartile range, 25th and 75th percentiles (boxes), and medians (dots). Tissue source (B = Bone, D = Dentine, E = Enamel) and the number of peptides used for the calculation are shown at the bottom. b, Extent of tryptophan (W) oxidation leading to several diagenetic products, measured as relative spectral counts. c, Alignment of peptides (positions 124-137, Enamelin) retrieved by digestion-free acid demineralisation from Pleistocene Stephanorhinus ex gr. etruscus-hundsheimensis specimen (GNM Dm.5/157-16635). d, Barplot of peptide length distribution of specimen Dm.5/157-16635 and Medieval (CTRL) undigested ovicaprine dental enamel proteomes.

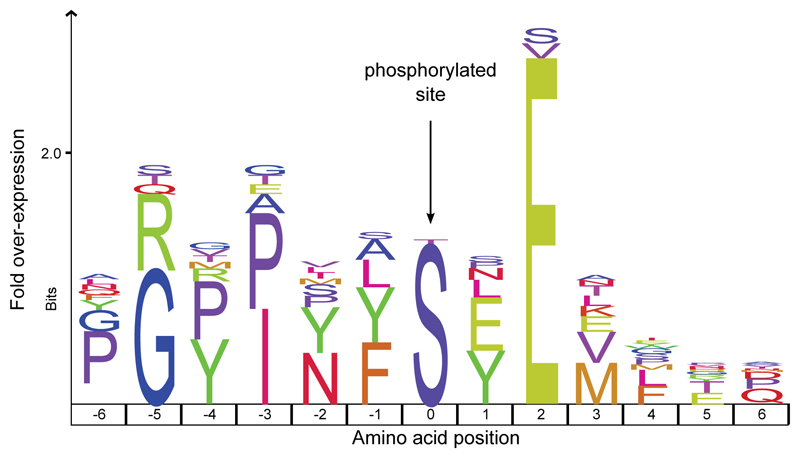

We confidently detect phosphorylation (Fig. 3, Extended Data Figs. 2, 5), a stable and tightly in vivo regulated physiological post-translational modification (PTM) previously detected in dental enamel proteins24,25. Most of the phosphorylated sites we identified belong to the S-x-E/phS motif, recognised by the secreted kinases of the Fam20C family, which are involved in phosphorylation of extracellular proteins and regulation of biomineralization26. Spectra supporting the identification of serine phosphorylation were validated manually and by comparison with MS2 obtained from synthetic peptides (Supplementary Information), confirming the automated MaxQuant identifications. Phosphorylated serine and threonine residues may be subjected to spontaneous dephosphorylation. However, by complexing with the Ca2+ ions in the enamel hydroxyapatite matrix, the peptide-bound phosphate groups can remain stable over millennia, as recently observed in ancient bone27. Previous studies demonstrated that, when complexed with mineral matrix, ~3.8 Ma protein residues can be retrieved from sub-tropical environments13. Limited availability of free water in the enamel matrix further reduces spontaneous dephosphorylation via beta-elimination. Altogether, these observations demonstrate that the heavily modified dental enamel proteome retrieved from the ~1.77 Ma old Dmanisi faunal material is endogenous and almost complete.

Figure 3. Sequence motif analysis of ancient enamel proteome phosphorylation.

Indicated is the overrepresentation of specific amino acids within six positions N- and C-terminal of the phosphorylated amino acids (position 0). See Extended Data Figure 5 for MS2 examples of both S-x-E and S-x-phS phosphorylated motifs.

Next, we used the palaeoproteomic sequence information to improve taxonomic assignment and achieve sex attribution for some of the Dmanisi faunal remains. Phylogenetic analysis of the five largest enamel+dentine proteomes, and of a moderately large bone proteome, allowed to confirm or improve the morphological identification of their specimens of origin (Extended Data Fig. 6; Figs. S10-15). In addition, confident identification of peptides specific for the isoform Y of amelogenin, coded on the non-recombinant portion of the Y chromosome, indicates that four tooth specimens, namely Dm.6/151.4.A4.12-16630 (Pseudodama), Dm.69/64.3.B1.53-16631 (Cervidae), Dm.8/154.4.A4.22-16639 (Bovidae), and Dm.M6/7.II.296-16856 (Cervidae), belonged to male individuals21 (Extended Data Fig. 7a-d).

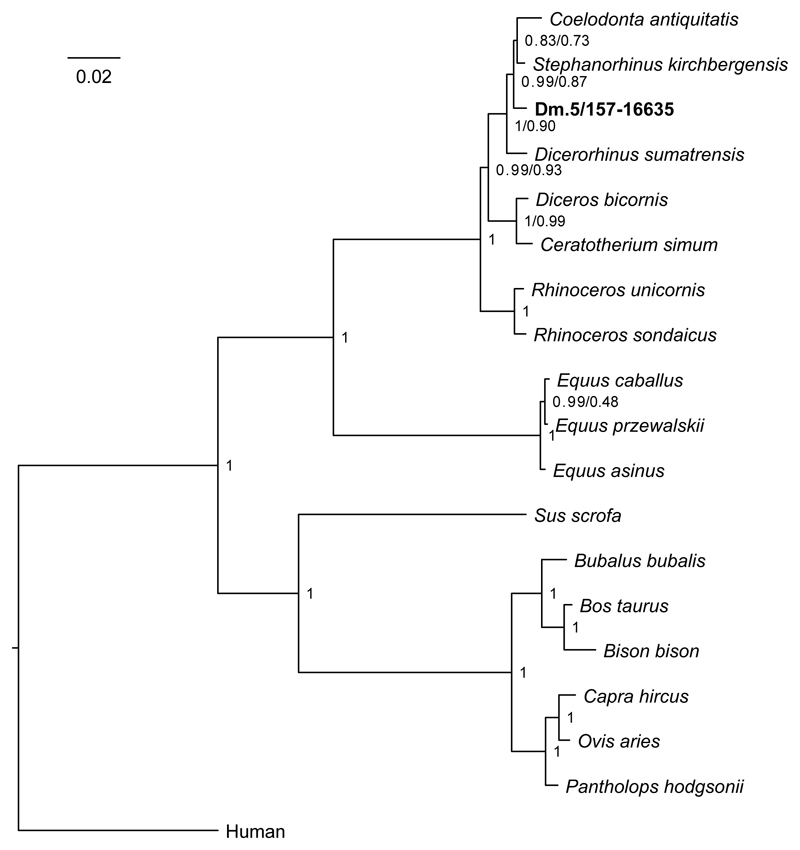

An enamel+dentine fragment, from the lower molar of a Stephanorhinus ex gr. etruscus-hundsheimensis (Dm.5/157-16635; Fig. 1c, Supplementary Information), returned the highest proteomic sequence coverage, encompassing a total of 875 amino acids, across 987 peptides (6 proteins; Extended Data Fig. 2; Supplementary Information). Following alignment of the enamel protein sequences retrieved from Dm.5/157-16635 against their homologues from all the extant rhinoceros species, plus the extinct woolly rhinoceros (†Coelodonta antiquitatis) and Merck’s rhinoceros (†Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis), phylogenetic reconstructions place the Dmanisi specimen closer to the extinct woolly and Merck’s rhinoceroses than to the extant Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), as an early divergent sister lineage (Fig. 4; Extended Data Fig. 8).

Figure 4. Phylogenetic relationships between the comparative enamel proteome dataset and specimen Dm.5/157-16635 (Stephanorhinus ex gr. etruscus-hundsheimensis).

Consensus tree from Bayesian inference on the concatenated alignment of six enamel proteins, using Homo sapiens as an outgroup. For each bipartition, we show the posterior probability obtained from the Bayesian inference. Additionally, for bipartitions where the Bayesian and the Maximum-likelihood inference support are different, we show (right) the support obtained in the latter. Scale indicates estimated branch lengths.

Our phylogenetic reconstruction confidently recovers the expected differentiation of the Rhinoceros genus from other genera considered, in agreement with previous cladistic28 and genetic analyses29 (Supplementary Information). This topology defines two-horned rhinoceroses as monophyletic and the one-horned condition as plesiomorphic, as previously proposed (Supplementary Information). We caution, however, that the higher-level relationships we observe between the rhinoceros monophyletic clades might be affected by demographic events, such as incomplete lineage sorting30 and/or gene flow between groups31, due to the limited number of markers considered. A confident and stable reconstruction of the structure of the Rhinocerotidae family needs the strong support only high-resolution whole-genome sequencing can provide. Regardless, the highly supported placement of the Dmanisi rhinoceros in the (Stephanorhinus, Woolly, Sumatran) clade will remain unaffected, should deeper phylogenetic relationships between the Rhinoceros genus and other family members be revised (Extended Data Fig. 8).

The phylogenetic relationships of the genus Stephanorhinus within the family Rhinocerotidae, as well as those of the several species recognized within this genus, are contentious. Stephanorhinus was initially included in the extant South-East Asian genus Dicerorhinus represented by the Sumatran rhinoceros species (D. sumatrensis)32. This hypothesis has been rejected and, based on morphological data, Stephanorhinus has been identified as a sister taxon of the woolly rhinoceros33. Furthermore, ancient DNA analysis supports a sister relationship between the woolly rhinoceros and D. sumatrensis 7,34,35.

As the Stephanorhinus ex gr. etruscus-hundsheimensis sequences from Dmanisi branch off basal to the common ancestor of the woolly and Merck’s rhinoceroses, these two species most likely derived from an early Stephanorhinus lineage expanding eastward from western Eurasia. Throughout the Plio-Pleistocene, Coelodonta adapted to continental and later to cold-climate habitats in central Asia. Its earliest representative, C. thibetana, displayed some clear Stephanorhinus-like anatomical features33. The presence in eastern Europe and Anatolia of the genus Stephanorhinus 35 is documented at least since the late Miocene, and the Dmanisi specimen most likely represents an Early Pleistocene descendent of the Western-Eurasian branch of this genus.

Ultimately, our phylogenetic reconstructions show that, as currently defined, the genus Stephanorhinus is paraphyletic, in line with previous morphological and palaeobiogeographical evidence (Supplementary Information). Accordingly, a systematic revision of the genera Stephanorhinus and Coelodonta, as well as their closest relatives, is needed.

In this study, we show that enamel proteome sequencing can overcome the time limits of ancient DNA preservation and the reduced phylogenetic content of COL1 sequences. Given the abundance of teeth in the palaeontological record, the approach presented here holds the potential to address a wide range of questions pertaining to the Early and Middle Pleistocene evolutionary history of a large number of mammals, including hominins, at least in temperate climates.

Methods

Dmanisi & sample selection

Dmanisi is located about 65 km southwest of the capital city of Tbilisi in the Kvemo Kartli region of Georgia, at an elevation of 910 meters above sea level (Lat: 41° 20’ N, Lon: 44° 20’ E)10,18. The 23 fossil specimens we analysed were retrieved from stratum B1, in excavation blocks M17, M6, block 2, and area R11 (Extended Data Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 1). Stratum B deposits date between 1.78 Ma and 1.76 Ma19. All the analysed specimens were collected between 1984 and 2014 and their taxonomic identification was based on traditional comparative anatomy.

After the sample preparation and data acquisition for all the Dmanisi specimens was concluded, we applied the whole experimental procedure to a medieval ovicaprine (sheep/goat) dental enamel+dentine specimen that was used as control. For this sample, we used extraction protocol “C”, and generated tandem MS data using a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The data were searched against the goat proteome, downloaded from the NCBI Reference Sequence Database (RefSeq) archive on 31st May 2017 (Supplementary Information). The ovicaprine specimen was found at the “Hotel Skandinavia” site in the city of Århus, Denmark and stored at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

Biomolecular preservation

We assessed the potential of ancient protein preservation prior to proteomic analysis by measuring the extent of amino acid racemisation in a subset of samples (6/23)36. Enamel chips, with all dentine removed, were powdered, and two subsamples per specimen were subject to analysis of their free (FAA) and total hydrolysable (THAA) amino acid fractions. Samples were analysed in duplicate by RP-HPLC, with standards and blanks run alongside each one of them (Supplementary Information). The D/L values of aspartic acid/asparagine, glutamic acid/glutamine, phenylalanine and alanine (D/L Asx, Glx, Phe, Ala) were assessed (Extended Data Fig. 4) to provide an overall estimate of intra-crystalline protein decomposition (IcPD).

Proteomics

All the sample preparation procedures for palaeoproteomic analysis were conducted in laboratories dedicated to the analysis of ancient DNA and ancient proteins in clean rooms fitted with filtered ventilation and positive pressure, in line with recent recommendations for ancient protein analysis37. A mock “extraction blank”, containing no starting material, was prepared, processed and analysed together with each batch of ancient samples.

Sample preparation

The external surface of bone samples was gently removed, and the remaining material was subsequently powdered. Enamel fragments, occasionally mixed with small amounts of dentine, were removed from teeth with a cutting disc and subsequently crushed into a rough powder. Ancient protein residues were extracted from approximately 180-220 mg of mineralised material, unless otherwise specified, using three different extraction protocols, hereafter referred to as “A”, “B” and “C” (Supplementary Information):

Extraction Protocol A - FASP

Tryptic peptides were generated using a filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) approach38, as previously performed on ancient samples39.

Extraction Protocol B - GuHCl Solution and Digestion

Bone or enamel+dentine powder was demineralised in 1 mL 0.5 M EDTA pH 8.0. After removal of the supernatant, all demineralised pellets were re-suspended in a 300 μL solution containing 2 M guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl, Thermo Scientific), 100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 20 mM 2-Chloroacetamide (CAA), 10 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) in ultrapure H2O40,41. A total of 0.2 μg of mass spectrometry-grade rLysC (Promega P/N V1671) enzyme was added before the samples were incubated for 3-4 hours at 37°C with agitation. Samples and negative controls were subsequently diluted to 0.6 M GuHCl, and 0.8 μg of mass spectrometry-grade Trypsin (Promega P/N V5111) was added. Next, samples and negative controls were incubated overnight under mechanical agitation at 37°C. On the following day, samples were acidified, and the tryptic peptides were purified on C18 Stage-Tips, as previously described42.

Extraction Protocol C - Digestion-Free ACID Demineralisation

Dental enamel powder, with possible trace amounts of dentine, was demineralised in 1.2 M HCl at room temperature, after which the solubilised protein residues were directly cleaned and concentrated on Stage-Tips, as described above. The sample prepared on Stage-Tip “#1217” was processed with 10% TFA instead of 1.2 M HCl. All the other parameters and procedures were identical to those used for all the other samples extracted with protocol “C”.

Tandem mass spectrometry

Different sets of samples (Supplementary Information §5.1, 5.2) were analysed by nanoflow liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-MS/MS) on an EASY-nLC™ 1000 or 1200 system connected to a Q-Exactive, a Q-Exactive Plus, or to a Q-Exactive HF (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) mass spectrometer. Before and after each MS/MS run measuring ancient or extraction blank samples, two successive MS/MS runs were included in the sample queue in order to prevent carryover contamination between the samples. These consisted, first, of a MS/MS run ("MS/MS blank" run) with an injection exclusively of the buffer used to re-suspend the samples (0.1% TFA, 5% ACN), followed by a second MS/MS run ("MS/MS wash" run) with no injection.

Data analysis

Raw data files generated during MS/MS spectral acquisition were searched using MaxQuant43, version 1.5.3.30, and PEAKS44, version 7.5. A two-stage peptide-spectrum matching approach was adopted (Supplementary Information §5.3). Raw files were initially searched against a target/reverse database of collagen and enamel proteins retrieved from the UniProt and NCBI Reference Sequence Database (RefSeq) archives45,46, taxonomically restricted to mammalian species. A database of partial “COL1A1” and “COL1A2” sequences from cervid species47 was also included. The results from the preliminary analysis were used for a first, provisional reconstruction of protein sequences (MaxQuant search 1, MQ1).

For specimens whose dataset resulted in a narrower, though not fully resolved, initial taxonomic placement, a second MaxQuant search (MQ2) was performed using a new protein database taxonomically restricted to the “order” taxonomic rank as determined after MQ1. For the MQ2 matching of the MS/MS spectra from specimen Dm.5/157-16635, partial sequences of serum albumin and enamel proteins from Sumatran (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), Javan (Rhinoceros sondaicus), Indian (Rhinoceros unicornis), woolly (Coelodonta antiquitatis), Mercks (Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis), and Black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), were also added to the protein database. All the protein sequences from these species were reconstructed from draft genomes for each species (Dalen and Gilbert, unpublished data, Supplementary Information).

For each MaxQuant and PEAKS search, enzymatic digestion was set to “unspecific” and the following variable modifications were included: oxidation (M), deamidation (NQ), N-term Pyro-Glu (Q), N-term Pyro-Glu (E), hydroxylation (P), phosphorylation (S). The error tolerance was set to 5 ppm for the precursor and to 20 ppm, or 0.05 Da, for the fragment ions in MaxQuant and PEAKS respectively. For searches of data generated from sample fractions partially or exclusively digested with trypsin, another MaxQuant and PEAKS search was conducted using the “enzyme” parameter set to “Trypsin/P”. Carbamidomethylation (C) was set: (i) as a fixed modification, for searches of data generated from sets of sample fractions exclusively digested with trypsin, or (ii) as a variable modification, for searches of data generated from sets of sample fractions partially digested with trypsin. For searches of data generated exclusively from undigested sample fractions, carbamidomethylation (C) was not included as a modification, neither fixed nor variable.

The datasets re-analysed with MQ2 search, were also processed with the PEAKS software using the entire workflow (PEAKS de novo to PEAKS SPIDER) in order to detect hitherto unreported single amino acid polymorphisms (SAPs). Any amino acid substitution detected by the “SPIDER” homology search algorithm was validated by repeating the MaxQuant search (MQ3). In MQ3, the protein database used for MQ2 was modified to include the amino acid substitutions detected by the “SPIDER” algorithm.

Ancient protein sequence reconstruction

The peptide sequences confidently identified by the MQ1, MQ2, MQ3 were aligned using the software Geneious48 (v. 5.4.4, substitution matrix BLOSUM62). The peptide sequences confidently identified by the PEAKS searches were aligned using an in-house R-script. A consensus sequence for each protein from each specimen was generated in FASTA format, without filtering on depth of coverage. Amino acid positions that were not confidently reconstructed were replaced by an “X”. Novel SAPs discovered through PEAKS were only accepted if these were further validated by repeating the MaxQuant search (MQ3). All isoleucine were converted into leucines, as standard MS/MS cannot differentiate between these two isobaric amino acids. For possible deamidated sites, we checked whether there were positions in our reference sequence database where both Q and E or both N and D occurred on the same position, and where we also had ancient sequences matching. For sample Dm.5/157-16635, only one such position existed, and this was replaced by an “X” in our consensus sequence. Based on parsimony, for other Q, E, N, and D positions we called the amino acid present in the reference proteome, regardless of their phylogenetic relevance. The output of the MQ2 and 3 searches was used to extend the coverage of the ancient protein sequences initially identified in the MQ1 iteration. For specimen DM.5/157-16335, all the experimentally identified peptides, as well as the respective best matching MS/MS spectra covering the sites informative for Rhinocerotidae phylogenetic inference, are provided as Supplementary Information (“Key MS-MS Spectra” file). All the reported MS/MS spectra are annotated using the advanced annotation mode of MaxQuant. Selected spectra matching to peptides covering phylogenetically informative amino acid positions were manually inspected, validated and annotated by an experienced mass spectrometrist, in all cases in full agreement with bioinformatic sequence assignment (Supplementary Information, “Key MS-MS Spectra” file). We utilized MS2PIP fragment ion spectral intensity prediction49 (version: v20190107; model: HCD) to demonstrate that the experimentally observed fragment ion intensities are highly correlated with the theoretical ones (Fig. S3). Finally, we generated synthetic peptides for 19 selected peptides covering Rhinocerotidae SAPs in DM.5/157-16635.

Post translational modifications

Deamidation

After removal of likely contaminants, the extent of glutamine and asparagine deamidation was estimated for individual specimens, by using the MaxQuant output files as previously published41 (Supplementary Information).

Other Spontaneous Chemical Modifications

Spontaneous post-translational modifications (PTMs) associated with chemical protein damage were searched using the PEAKS PTM tool and the dependent peptides search mode50 in MaxQuant. In the PEAKS PTM search, all modifications in the Unimod database were considered. The mass error was set to 5.0 ppm and 0.5 Da for precursor and fragment, respectively. For PEAKS, the de novo ALC score was set to a threshold of 15 % and the peptide hit threshold to 30. The results were filtered by an FDR of 5 %, de novo ALC score of 50 %, and a protein hit threshold of ≥ 20. The MaxQuant dependent peptides search was carried out with the same search settings as described above and with a dependent peptide FDR of 1 % and a mass bin size of 0.0065 Da.

Phosphorylation

Class I phosphorylation sites were selected with localisation probabilities of ≥0.98 in the Phosph(ST)Sites MaxQuant output file. Sequence windows of ±6 aa from all identified sites were compared against a background file containing all non-phosphorylated peptides using a linear kinase sequence motif enrichment analysis in IceLogo (version 1.3.8)51.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Reference datasets

We assembled a reference dataset consisting of publicly available protein sequences from representative ungulate species belonging to the following families: Equidae, Rhinocerotidae, Suidae and Bovidae (Supplementary Information §7 and §8). As Cervidae and carnivores are absent from protein sequence databases to a various extent, we did not attempt phylogenetic placement of samples from these taxa. Instead, we conducted our phylogenetic analysis on the five best-performing enamel proteomes (Dm.5/154.2.A4.38-16632), Dm.5/157-16635, Dm.5/154.1.B1.1-16638, Dm.8/154.4.A4.22-16639, Dm.8/152.3.B1.2-16641) and the largest bone proteome (Dm.bXI.North.B1a.collection-16658) we recovered (see Extended Data Table 2).

We extended this dataset with the protein sequences from extinct and extant rhinoceros species including: the woolly rhinoceros (†Coelodonta antiquitatis), the Merck’s rhinoceros (†Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis), the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), the Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), and the Black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis). Their corresponding protein sequences were obtained following translation of high-throughput DNA sequencing data, after filtering reads with mapping quality lower than 30 and nucleotides with base quality lower than 20, and calling the majority rule consensus sequence using ANGSD52 For the woolly and Merck’s rhinoceroses we excluded the first and last five nucleotides of each DNA fragment in order to minimize the effect of post-mortem ancient DNA damage53. Each consensus sequence was formatted as a separate blast nucleotide database. We then performed a tblastn54 alignment using the corresponding white rhinoceros sequence as a query, favouring ungapped alignments in order to recover translated and spliced protein sequences. Resulting alignments were processed using ProSplign algorithm from the NCBI Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline55 to recover the spliced alignments and translated protein sequences.

Construction of phylogenetic trees

For each specimen, multiple sequence alignments for each protein were built using MAFFT56 and concatenated onto a single alignment per specimen. These were inspected visually to correct obvious alignment mistakes, and all the isoleucine residues were substituted with leucine ones to account for indistinguishable isobaric amino acids at the positions where the ancient protein carried one of such amino acids. Based on these alignments, we inferred the phylogenetic relationship between the ancient samples and the species included in the reference dataset by using three approaches: distance-based neighbour-joining, maximum likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic inference (Supplementary Information).

Neighbour-joining trees were built using the phangorn57 R package, restricting to sites covered in the ancient samples. Genetic distances were estimated using the JTT model, considering pairwise deletions. We estimated bipartition support through a non-parametric bootstrap procedure using 500 pseudoreplicates. We used PHyML 3.158 for maximum likelihood inference based on the whole concatenated alignment. For likelihood computation, we used the JTT substitution model with two additional parameters for modelling rate heterogeneity and the proportion of invariant sites. Bipartition support was estimated using a non-parametric bootstrap procedure with 500 replicates. Bayesian phylogenetic inference was carried out using MrBayes 3.2.659 on each concatenated alignment, partitioned per gene. While we chose the JTT substitution model in the two approaches above, we allowed the Markov chain to sample parameters for the substitution rates from a set of predetermined matrices, as well as the shape parameter of a gamma distribution for modelling across-site rate variation and the proportion of invariable sites. The MCMC algorithm was run with 4 chains for 5,000,000 cycles. Sampling was conducted every 500 cycles and the first 25% were discarded as burn-in. Convergence was assessed using Tracer v. 1.6.0, which estimated an ESS greater than 5,500 for each individual, indicating reasonable convergence for all runs.

Ancient DNA Analysis

The samples were processed using strict aDNA guidelines in a clean lab facility at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen. DNA extraction was attempted on five of the ancient animal samples (Supplementary Information §9, §13). Powdered samples (120-140 mg) were extracted using a silica-in-solution method12,60. To prepare the samples for NGS sequencing, 20 μL of DNA extract was built into a blunt-end library using the NEBNext DNA Sample Prep Master Mix Set 2 (E6070) with Illumina-specific adapters. The libraries were PCR-amplified with inPE1.0 forward primers and custom-designed reverse primers with a 6-nucleotide index61. Two extracts (MA399 and MA2481, from specimens 16859 and 16635 respectively) yielded detectable DNA concentrations (Table S9). The libraries generated from specimen 16859 and 16635 were processed on different flow cells. They were pooled with others for sequencing on an Illumina 2000 platform (MA399_L1, MA399_L2), using 100bp single read chemistry, and on an Illumina 2500 platform (MA2481_L1), using 81bp single read chemistry.

The data were base-called using the Illumina software CASAVA 1.8.2 and sequences were demultiplexed with a requirement of a full match of the six nucleotide indexes that were used. Raw reads were processed using the PALEOMIX pipeline following published guidelines62, mapping against the cow nuclear genome (Bos taurus 4.6.1, accession GCA_000003205.4), the cow mitochondrial genome (Bos taurus), the red deer mitochondrial genome (Cervus elaphus, accession AB245427.2), and the human nuclear genome (GRCh37/hg19), using BWA backtrack63 v0.5.10 with the seed disabled. All other parameters were set as default. PCR duplicates from mapped reads were removed using the picard tool MarkDuplicate [http://picard.sourceforge.net/].

Sample Dm.5/157-16635 Morphological Measurements

We followed the methodology introduced by Guérin32. The maximal length of the tooth is measured with a digital calliper at the lingual side of the tooth and parallel to the occlusal surface. All measurements are given in mm (Supplementary Information §3).

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Generalized stratigraphic profiles for Dmanisi, indicating specimen origins.

a, Type section of the Dmanisi M5 Excavation block. b, Stratigraphic profile of excavation area M6. M6 preserves a larger gully associated with the pipe-gully phase of stratigraphic-geomorphic development in Stratum B1. The thickness of Stratum B1 gully fill extends to the basalt surface, but includes “rip-ups” of Strata A1 and A2, showing that B1 deposits post-date Stratum A. c, Stratigraphic section of excavation area M17. Here, Stratum B1 was deposited after erosion of Stratum A deposits. The stratigraphic position of the Stephanorhinus sample Dm.5/157-16635 is highlighted with a red diamond. The Masavara basalt is ca. 50 cm below the base of the shown profile. d, Northern section of Block 2. Following collapse of a pipe and erosion to the basalt, the deeper part of this area was filled with local gully fill of Stratum B1/x/y/z. Note the uniform burial of all Stratum B1 deposits by Strata B2-B4. Sampled specimens are indicated by CGG five-digit numbers. See Extended Data Table 1 for both CGG and GNM specimen numbers.

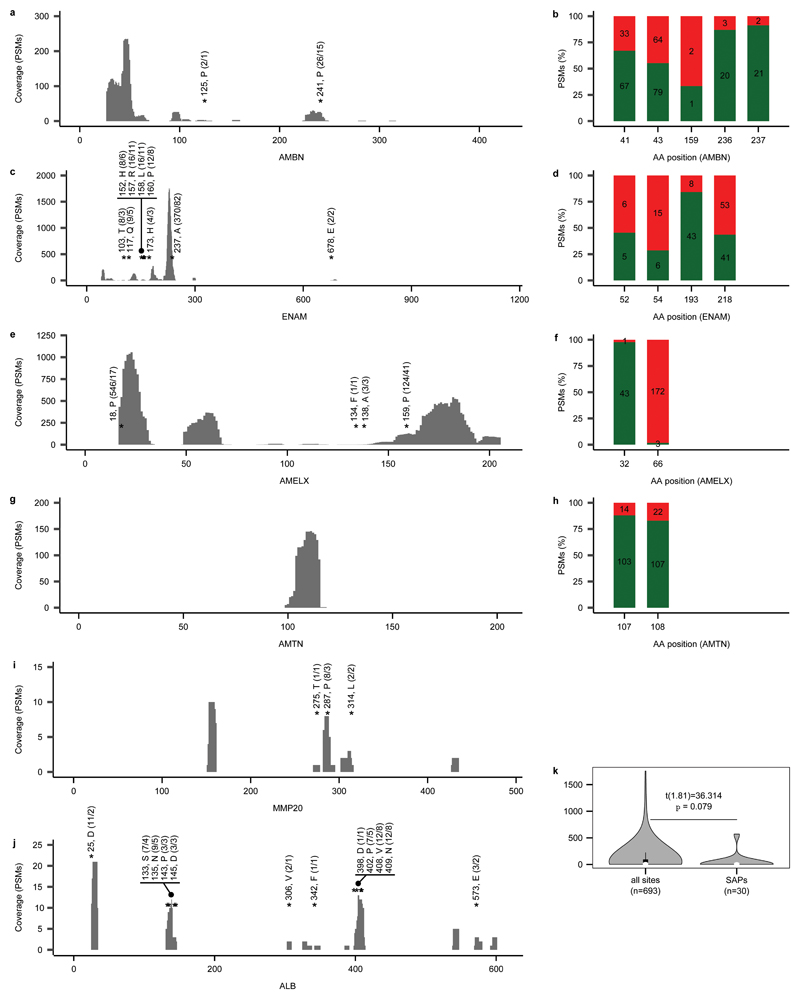

Extended Data Fig. 2. Proteomic sequence coverage for specimen Dm.5/157-16635 (Stephanorhinus).

a, c, e, g, i, j, PSM sequence coverage of proteins AMBN, ENAM, AMELX, AMTN, MMP20 and ALB, respectively. Annotations include: “amino acid position, amino acid called in that position (number of PSMs/peptides covering that position)” for the phylogenetically informative SAPs within Rhinocerotidae. b, d, f, h, Frequency (%) of phosphorylated (green) and non-phosphorylated (red) PSMs per amino acid position for AMBN, ENAM, AMELX and AMTN, respectively. Numbers within the bars provide the PSM counts. k, Violinplot of PSM coverage distribution for all covered sites (n=693) and those of phylogenetic relevance (SAPs, n=30). The boxplots define the range of the data, with whiskers extending to 1.5 the interquartile range, 25th and 75th percentiles (boxes), and medians (dots). All panels based on MQ results only. Supplementary File “Key MS-MS Spectra” contains spectral examples and fragment ion series alignments for each of the marked SAPs.

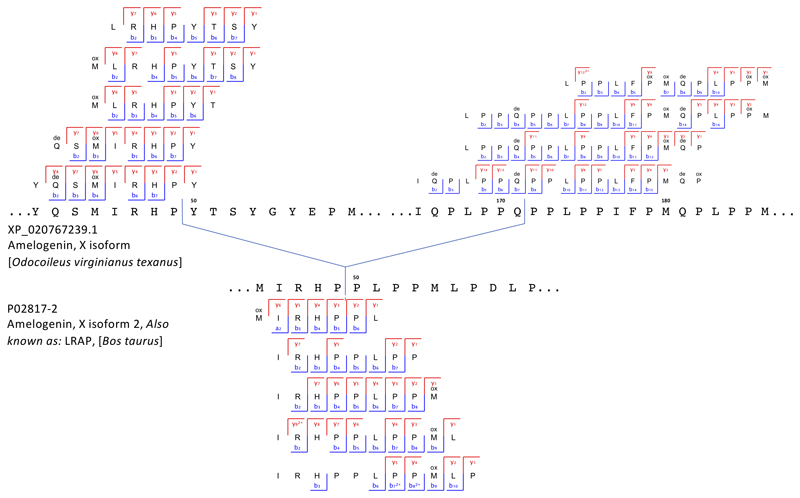

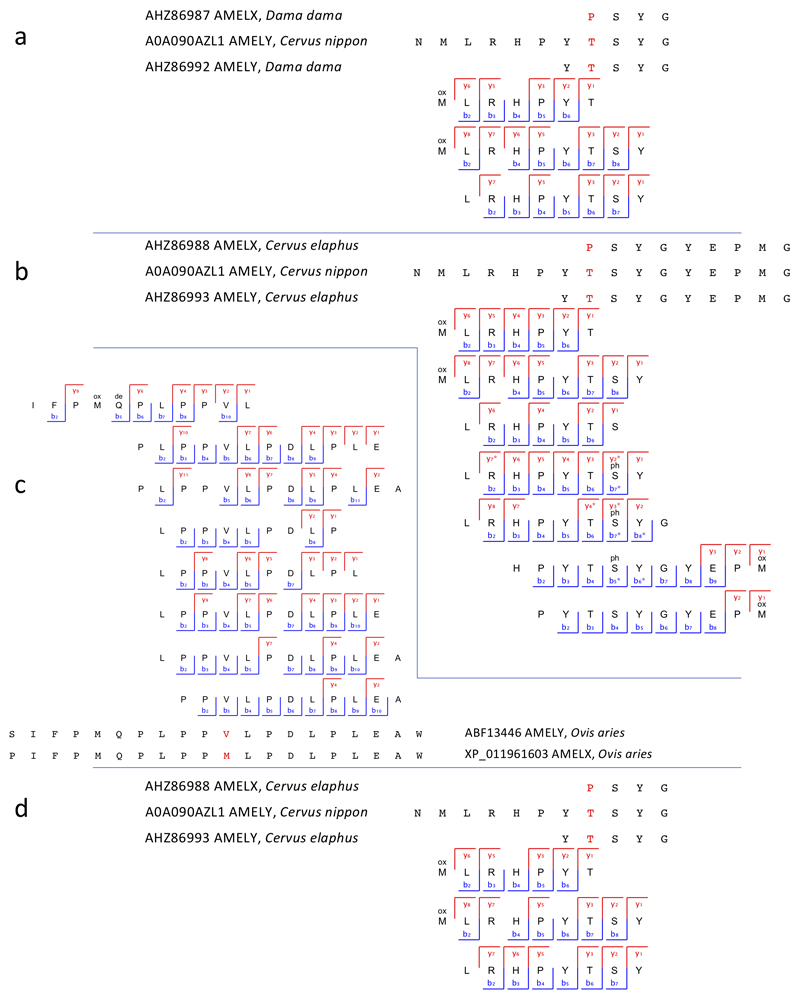

Extended Data Figure 3. Peptide and ion fragment coverage of amelogenin X (AMELX) isoforms 1 and 2 from specimen Dm.M6/7.II.296-16856 (Cervidae).

Peptides specific to amelogenin X (AMELX) isoforms 1 and 2 appear in the upper and lower parts of the figure, respectively. No amelogenin X isoform 2 is currently reported in public databases for the Cervidae group. Accordingly, the amelogenin X isoform 2-specific peptides were identified by MaxQuant spectral matching against bovine (Bos Taurus) amelogenin X isoform 2 (UniProt accession number P02817-2). Amelogenin X isoform 2, also known as leucine-rich amelogenin peptide (LRAP), is a naturally occurring amelogenin X isoform from the translation product of an alternatively spliced transcript.

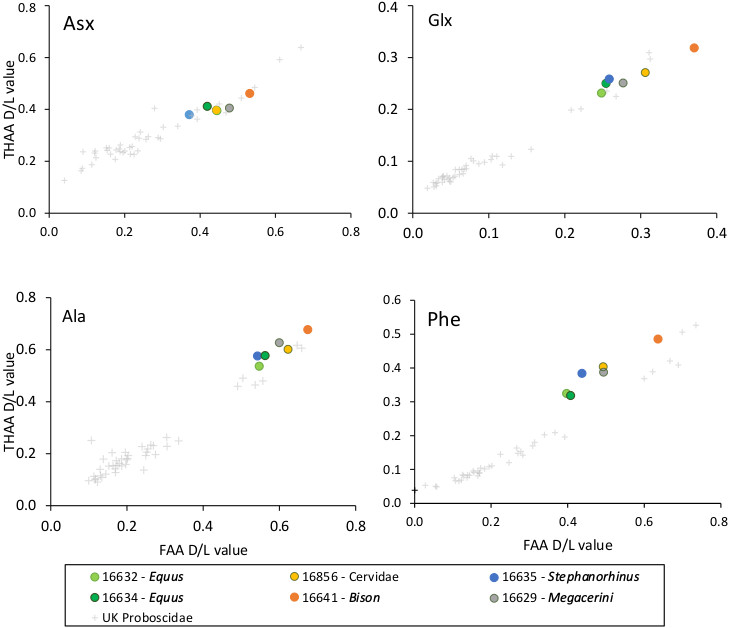

Extended Data Figure 4. Amino Acid Racemisation.

Extent of intra-crystalline racemization in enamel for the free amino acid (FAA, x-axis) fraction and the total hydrolysable amino acids (THAA, y-axis) fraction for four amino acids (Asx, Glx, Ala and Phe). Note differences in axis scale. Intra-crystalline data from Proboscidea enamel from a range of UK sites64 has been shown for comparison (black crosses). Both taxa from Dmanisi and the UK exhibit a similar relationship between FAA and THAA racemization and R2 values have been calculated based on a polynomial relationship (order = 2, all >0.93).

Extended Data Figure 5. Ancient enamel proteome phosphorylation.

Annotated spectra including phosphorylated serine (phS). a, Phosphorylation in the S-x-E motif (AMEL). b, Phosphorylation in the S-x-phS motif (AMBN). Phosphorylation was independently observed in all three separate analyses of Dm.5/157-16635, including multiple spectra and peptides (see Extended Data Fig. 2).

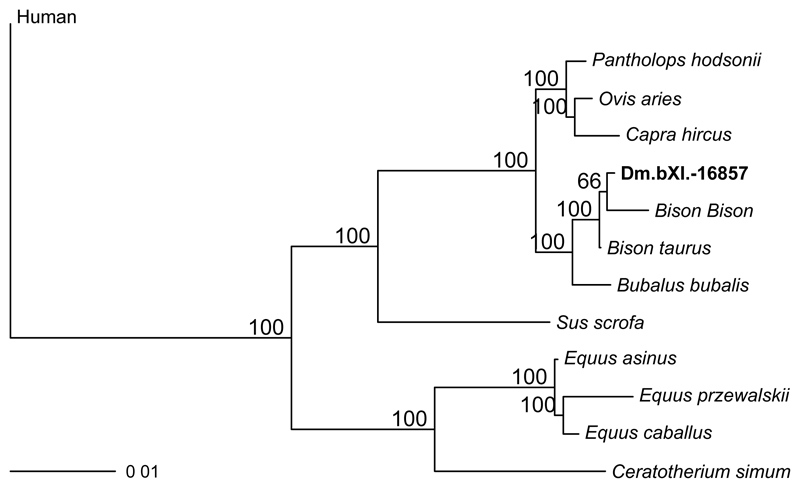

Extended Data Figure 6. Phylogenetic relationships between the comparative reference dataset and specimen Dm.bXI-16857.

Consensus tree from Bayesian inference. The posterior probability of each bipartition is shown as a percentage to the left of each node.

Extended Data Figure 7. Amelogenin Y-specific matches.

a) Specimen Dm.6/151.4.A4.12-16630 (Pseudodama). b) Specimen Dm.69/64.3.B1.53-16631 (Cervidae). c) Specimen Dm.8/154.4.A4.22-16639 (Bovidae). d) Specimen Dm.M6/7.II.296-16856 (Cervidae). Note the presence of deamidated glutamine (deQ) and asparagine (deN), oxidated methionine (oxM), and phosphorylated serine (phS).

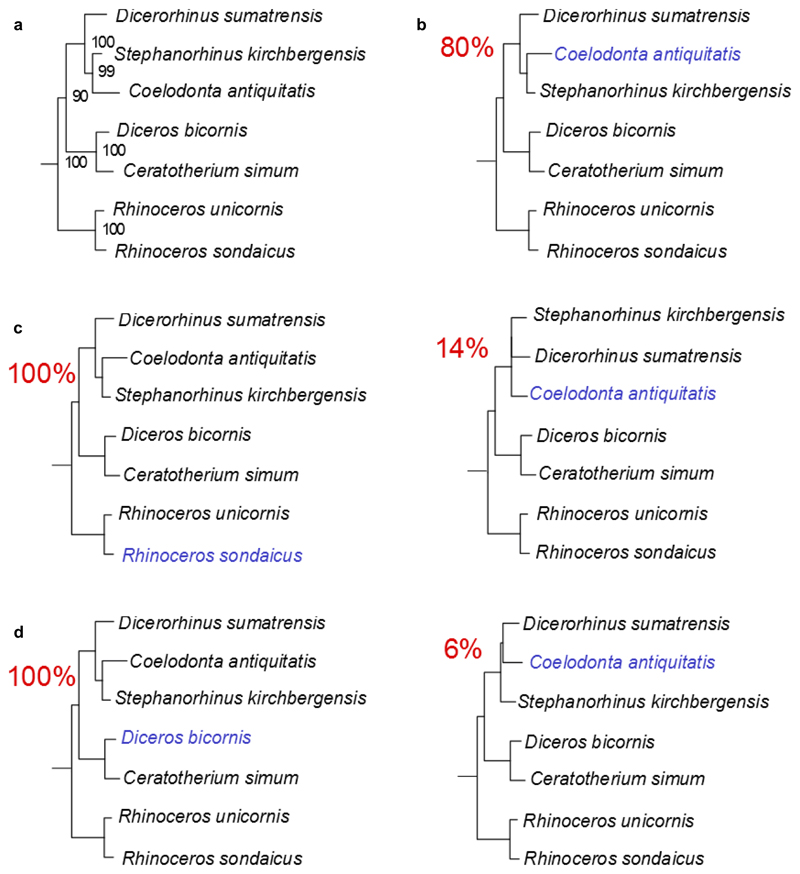

Extended Data Figure 8. Effect of the missingness in the tree topology.

a, Maximum-likelihood phylogeny obtained using PhyML and the protein alignment excluding the ancient Dmanisi rhinoceros Dm.5/157-16635. b, Topologies obtained from 100 random replicates of the Woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis). In each replicate the amount of missing sites was similar to the one observed in the Dm.5/157-16635 specimen (72.4% missingness). The percentage shown for each topology indicates the number of replicates in which that particular topology was recovered. c, Similar to b, but for the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus). d, Similar to b, but for the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis).

Extended Data Table 1. Genome and proteome survival in 23 Dmanisi fossil fauna specimens.

For each specimen, the Centre for GeoGenetics (CGG) reference number and the Georgian National Museum (GNM) specimen field number are reported. *or the narrowest possible taxonomic identification achievable using comparative anatomy methods. †Only collagens survive. B = Bone, D = Dentine, E = Enamel. Extractions of enamel might include some residual dentine. Accordingly, both tissues are either listed separately (○D, ●E, in case of no collagen preservation), or together (●E+D, in case of collagen preservation). Open circles (○) indicate no molecular preservation; (●) closed circles indicate molecular preservation.

| CGG ref. numb. | GNM specimen number | Morphological identification* | Anatomy | Ancient DNA | Protein extr. Method A | Protein extr. Method B | Protein extr. Method C | Phylogenetic analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16486 | Dm.bXl.sqA6.V._. | Canis etruscus | P4 sin. | ○E+D | ||||

| 16626 | Dm.6/154.2/4.A4.17 | Artiodactyla | tibia sin. | ○B | ||||

| 16628 | Dm.7/154.2.A2.27 | Cervidae | me Ill&IV dex. | ●B† | ||||

| 16629 | Dm.5/154.3.A4.32 | Cervidae | hem imandible sin. with dp2, dp3, dp4, m1 | ○B | ●E+D | |||

| 16630 | Dm.6/151.4.A4.12 | Pseudodama nestii | hemimandible dex. with p2-m3 | ○B | ○D, ●E | |||

| 16631 | Dm.69/64.3.81.53 | Cervidae | maxilla sin. with P3 | ○B | ○D, ●E | |||

| 16632 | Dm.5/154.2.A4.38 | Equus stenonis | i3 dex. | ●E+D | Fig. S10 | |||

| 16633 | Dm.5/153.3.A2.33 | Equus stenonis | mc Ill & mc II sin. | ○B | ||||

| 16634 | Dm.7/151.2.81/A4.1 | Equus stenonis | m/1 or m/2 dex. | ○D, ●E | ||||

| 16635 | Dm.5/157.profile cleaning | Stephanorhinus sp. | m/1 sin. | ○ | ○D, ●E | Fig. 4, Fig. S11 | ||

| 16636 | Dm.6/153.1.A4.13 | Rhinocerotidae | tibia dex. | ○B | ||||

| 16637 | Dm.7/154.2.A4.8 | Bovidae | mt lll&IV sin. | ●B† | ||||

| 16638 | Dm.5/154.1.B1.1 | Bovidae | hemimandible dex. with p3-m3 | ○B | ○D, ●E | Fig. S12 | ||

| 16639 | Dm.8/154.4.A4.22 | Bovidae | maxilla dex. with P2-M2 | ○D, ●E | Fig. S13 | |||

| 16640 | Dm.6/151.2.A4.97 | Bison georgicus | mt lll&IV sin. | ○B | ||||

| 16641 | Dm.8/152.3.B1.2 | Bison georgicus | m3 dex. | ○D, ●E | Fig. S14 | |||

| 16642 | Dm.8/153.4.A4.5 | Canis etruscus | hemimandible sin. with p1-m2 | ○D, ●E | ||||

| 16856 | Dm.M6/7.Il.296 | Cervidae | m2 sin. | ○ | ●D† | ○D, ●E | ●E+D | |

| 16857 | Dm.bXl.profile cleaning | lndet. | long bone fragment of a herbivore | ○ | ●B† | ○B | ○B | Fig. S15, EDF6 |

| 16858 | Dm.bXl.North.B1a.collection | Cervidae | metapodium fragment | ○B | ○B | ○B | ||

| 16859 | D4.collection | lndet. | fragments of pelvis and ribs of a large mammal | ○ | ○B | ○B | ○B | |

| 16860 | Dm.65/62.1.A1. | Cervidae | P4 sin. | ○ | ○D, ●E | ○D, ●E | ||

| 16861 | Dm.64/63.1.B1z.collection | Equus stenonis | fragment of an upper tooth | ○D, ●E | ○D, ●E | |||

| Neg. contr. (blank) | NC | NC | NC |

Extended Data Table 2. Proteome composition and coverage.

Aggregated data from different extraction methods and/or tissues from the same specimen. In those cells reporting two values separated by the “|” symbol, the first value refers to MaxQuant (MQ) searches performed selecting unspecific digestion, while the second value refers to MQ searches performed selecting trypsin digestion. For those cells including one value only, it refers to MQ searches performed selecting unspecific digestion. Final amino acid coverage, incorporating both MQ and PEAKS searches, is reported in the last column. *supporting all peptides. See Extended Data Table 1 for tissue sources per specimen and both CGG and GNM specimen numbers.

| Specimen | Protein Name | Sequence length | Razor and unique peptides | Matched spectra* | Coverage after MaxQuant searches (%) | Final coverage after MaxQuant and PEAKS searches (%) | Final coverage (aa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16628 | Collagen alpha-1(I) | 1158 | 5 | 8 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 37 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 16629 | Amelogenin X | 209 | 79 | 190 | 36.8 | 36.8 | 77 | |

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 51 | 84 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 110 | ||

| Enamelin | 1129 | 58 | 133 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 73 | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(I) | 1453 | 3 | 3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 29 | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(III) | 1464 | 2 | 3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 20 | ||

| Amelotin | 212 | 2 | 2 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 10 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16630 | Enamelin | 1129 | 180 | 3 | 530 | 5 | 11.8 | 2.7 | 15.4 | 174 | |

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 105 | 231 | 30.9 | 31.4 | 138 | ||

| Amelogenin X | 213 | 116 | 529 | 62.0 | 62.9 | 134 | ||

| AmelogeninY | 192 | 4 | 9 | 13.0 | 22.9 | 44 | ||

| Amelotin | 212 | 5 | 6 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 17 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16631 | Enamelin | 916 | 175 | 751 | 11.0 | 11.7 | 107 | |

| Amelogenin X | 213 | 156 | 598 | 48.8 | 61.5 | 131 | ||

| AmelogeninY | 90 | 5 | 18 | 15.6 | 25.6 | 23 | ||

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 71 | 133 | 24.1 | 25.2 | 111 | ||

| MMP 20 | 482 | 2 | 2 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 19 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16632 | Enarnelin | 1144 | 401 | 2160 | 17.9 | 19.1 | 219 | |

| Amelogenin X | 192 | 280 | 960 | 84.4 | 84.4 | 162 | ||

| MMP 20 | 424 | 49 | 67 | 33.3 | 33.3 | 141 | ||

| Serum albumin | 607 | 11 | 18 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 37 | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(1) | 1513 | 4 | 4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 40 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16634 | Amelogenin X | 185 | 68 | 157 | 53.5 | 53.5 | 99 | |

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 47 | 58 | 23.4 | 23.4 | 103 | ||

| Enamelin | 920 | 33 | 87 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 41 | ||

| MMP 20 | 483 | 4 | 4 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 27 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16635 | Amelogenin X | 206 | 394 | 3 | 2793 | 5 | 73.8 | 7.8 | 85.9 | 177 | |

| Enamelin | 1150 | 382 | 2 | 2966 | 2 | 18.3 | 1.6 | 25.1 | 289 | ||

| Ameloblastin | 442 | 131 | 463 | 31.3 | 39.3 | 166 | ||

| Amelotin | 267 | 26 | 148 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 20 | ||

| Serum albumin | 607 | 34 | 64 | 18.5 | 24.5 | 149 | ||

| MMP20 | 483 | 15 | 25 | 11.8 | 15.3 | 74 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16637 | Collagen alpha-1(I) | 1453 | 2 | 2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 25 | |

| Collagen alpha-1(II) | 1421 | 2 | 2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 27 | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(III) | 1464 | 2 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 23 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16638 | Enamelin | 1129 | 235 | 7 | 1155 | 13 | 11.8 | 4.7 | 12.9 | 146 | |

| Amelogenin X | 192 | 185 | 3 | 734 | 5 | 52.0 | 10.9 | 60.4 | 116 | ||

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 64 | 2 | 120 | 4 | 30.0 | 5.7 | 36.4 | 160 | ||

| MMP 20 | 481 | 6 | 7 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 44 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16639 | Enamelin | 1129 | 202 | 726 | 12.0 | 12.6 | 142 | |

| Amelogenin X | 213 | 167 | 624 | 59.2 | 67.6 | 144 | ||

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 88 | 155 | 26.8 | 30.5 | 134 | ||

| AmelogeninY | 192 | 13 | 13 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 36 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16641 | Amelogenin X | 213 | 91 | 251 | 64.3 | 65.3 | 139 | |

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 69 | 122 | 28.9 | 28.9 | 127 | ||

| Enamelin | 1129 | 24 | 75 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 88 | ||

| Amelotin | 212 | 3 | 3 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 15 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16642 | Amelogenin X | 185 | 89 | 245 | 42.7 | 42.7 | 79 | |

| Enarnelin | 733 | 14 | 19 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 18 | ||

| Ameloblastin | 421 | 3 | 3 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 30 | ||

| MMP20 | 483 | 2 | 2 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 17 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16856 | Amelogenin X | 209 | 66 | 4 | 365 | 25 | 38.8 | 45.5 | 95 | |

| Enamelin | 916 | 58 | 13 | 153 | 70 | 8.2 | 10.2 | 93 | ||

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 21 | 31 | 14.8 | 14.8 | 65 | ||

| Collagen alpha-1(I) | 1047 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 14.5 | 16.9 | 177 | ||

| Collagen alpha-2(1) | 1054 | 4 | 8 | 51 9 | 10.6 | 10.6 | 112 | ||

| Serum albumin | 583 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 12 | 16.6 | 16.6 | 97 | ||

| AmelogeninY | 90 | 3 | 7 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16857 | Collagen alpha-1(I) | 1047 | 18 | 14 | 24 | 18 | 21.7 | 23.4 | 245 | |

| Collagen alpha-2(1) | 1274 | 16 | 11 | 17 | 11 | 17.7 | 24.3 | 310 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16860 | Amelogenin X | 192 | 46 | 98 | 30.7 | 32.3 | 62 | |

| Ameloblastin | 440 | 19 | 37 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 40 | ||

| Enamelin | 900 | 15 | 25 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 34 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 16861 | Amelogenin X | 185 | 14 | 15 | 36.8 | 38.9 | 72 | |

| Ameloblastin | 343 | 2 | 2 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 15 | ||

| Enarnelin | 915 | 2 | 2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 11 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Neg.Contr. Gr. 1: | ND | |||||||

| 235, 275, 706 | ||||||||

| Neg.Contr. Gr. 2: | ND | |||||||

| 630, 875, 889 | ||||||||

| Neg. Contr. Gr. 3: | Amelogenin X | 122 | 5 | 7 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 22 | |

| 1214, 1218 | ||||||||

Supplementary Material

Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

Acknowledgments

EC and FW are supported by the VILLUM FONDEN (grant number 17649) and by the European Commission through a Marie Skłodowska Curie (MSC) Individual Fellowship (grant number 795569). EW is supported by the Lundbeck Foundation, the Danish National Research Foundation, the Carlsberg Foundation, KU2016, and the Wellcome Trust. EC, CK, JVO, PR and DS are supported by the European Commission through the MSC European Training Network “TEMPERA” (grant number 722606). MM and RRJ-C are supported by the University of Copenhagen KU2016 (UCPH Excellence Programme) grant. MM is also supported by the Danish National Research Foundation award PROTEIOS (DNRF128). Work at the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research is funded in part by a donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number NNF14CC0001). MRD is supported by a PhD DTA studentship from NERC and the Natural History Museum (NE/K500987/1 & NE/L501761/1). KP is supported by the Leverhulme Trust (PLP -2012-116). LR and LP are supported by the Italian Ministry for Foreign Affairs (MAECI, DGSP-VI). LP was also supported by the EU-SYNTHESYS project (AT-TAF-2550, DE-TAF-3049, GB-TAF-2825, HU-TAF-3593, ES-TAF-2997) funded by the European Commission. LD is supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2017-04647) and FORMAS (grant nr 2015-676). MTPG is supported by ERC Consolidator Grant “EXTINCTION GENOMICS” (grant number 681396). LO is supported by the ERC Consolidator Grant “PEGASUS” (grant agreement No 681605). BS, JK and PDH are supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore foundation. BM-N is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Sciences (grant number CGL2016-80975-P). The aDNA analysis was carried out using the facilities of the University of Luxembourg, the Swedish Museum of Natural History and UC Santa Cruz. The authors would like to acknowledge support from Science for Life Laboratory, the National Genomics Infrastructure (Sweden), and UPPMAX for providing assistance in massive parallel sequencing and computational infrastructure. Research at Dmanisi is supported by the John Templeton Foundation, the Shota Rustaveli Science Foundation, and the Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship research award. The authors would also like to thank B. Triozzi and K. Murphy Gregersen for technical support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

E.C., D.Lo., and E.W. designed the study. A.K.F., M.M., R.R.J.-C., M.E.A., M.R.D., K.P., and E.C. performed laboratory experiments. M.Bu., M.T., R.F., E.P., T.S., Y.L.C., A.Gö., S.KSS.N., P.D.H., J.D.K., I.K., Y.M., J.A., R.-D.K., G.K., B.M.-N., M.-H.S.S., S.L., M.S.V., B.S., L.D., M.T.P.G., and D.Lo., provided ancient samples or modern reference material. E.C., F.W., L.P., J.R.M., D.Ly, V.J.M.M., D.S., C.D.K., A.Gi., L.O., L.R., J.V.O., P.L.R., M.R.D., and K.P. performed analyses and data interpretation. E.C., F.W., J.R.M., L.P. and E.W. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Author Information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The Authors declare no financial competing interests.

Data Availability

All the mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD011008. Genomic BAM files used for Rhinocerotidae protein sequence translation and protein sequence alignments used for phylogenetic reconstruction are available on Figshare (doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7212746).

Code Availability

The in-house R-script used to align the peptide sequences confidently identified by the PEAKS searches is available to everyone upon request to the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Cappellini E, et al. Ancient Biomolecules and Evolutionary Inference. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2018;87:1029–1060. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dabney J, Meyer M, Pääbo S. Ancient DNA damage. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012567. a012567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer M, et al. Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins. Nature. 2016;531:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature17405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadsworth C, Buckley M. Proteome degradation in fossils: investigating the longevity of protein survival in ancient bone. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2014;28:605–615. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweitzer MH, et al. Analyses of Soft Tissue from Tyrannosaurus rex Suggest the Presence of Protein. Science. 2007;316:277–280. doi: 10.1126/science.1138709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeter ER, et al. Expansion for the Brachylophosaurus canadensis Collagen I Sequence and Additional Evidence of the Preservation of Cretaceous Protein. Journal of Proteome Research. 2017;16:920–932. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willerslev E, et al. Analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes from extinct and extant rhinoceroses reveals lack of phylogenetic resolution. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welker F, et al. Middle Pleistocene protein sequences from the rhinoceros genus Stephanorhinus and the phylogeny of extant and extinct Middle/Late Pleistocene Rhinocerotidae. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3033. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirillova I, et al. Discovery of the skull of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Jäger, 1839) above the Arctic Circle. Quaternary Research. 2017;88:537–550. doi: 10.1017/qua.2017.53. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lordkipanidze D, et al. A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo. Science. 2013;342:326–331. doi: 10.1126/science.1238484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eastoe JE. Organic Matrix of Tooth Enamel. Nature. 1960;187:411–412. doi: 10.1038/187411b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orlando L, et al. Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. Nature. 2013;499:74–78. doi: 10.1038/nature12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demarchi B, et al. Protein sequences bound to mineral surfaces persist into deep time. eLife. 2016;5:e17092. doi: 10.7554/eLife.17092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welker F, et al. Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin's South American ungulates. Nature. 2015;522:81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature14249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen F, et al. A late Middle Pleistocene Denisovan mandible from the Tibetan Plateau. Nature. 2019;569:409–412. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetics. Vol. 75 Columbia University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckley M, Warwood S, van Dongen B, Kitchener AC, Manning PL. A fossil protein chimera; difficulties in discriminating dinosaur peptide sequences from modern cross-contamination. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological sciences. 2017;284 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0544. 20170544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabunia L, et al. Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science. 2000;288:1019–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferring R, et al. Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:10432–10436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106638108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castiblanco GA, et al. Identification of proteins from human permanent erupted enamel. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2015;123:390–395. doi: 10.1111/eos.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stewart NA, et al. The identification of peptides by nanoLC-MS/MS from human surface tooth enamel following a simple acid etch extraction. RSC Advances. 2016;6:61673–61679. doi: 10.1039/c6ra05120k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Doorn NL, Wilson J, Hollund H, Soressi M, Collins MJ. Site-specific deamidation of glutamine: a new marker of bone collagen deterioration. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2012;26:2319–2327. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catak S, Monard G, Aviyente V, Ruiz-Lopez MF. Computational study on nonenzymatic peptide bond cleavage at asparagine and aspartic acid. J Phys Chem A. 2008;112:8752–8761. doi: 10.1021/jp8015497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter T. Why nature chose phosphate to modify proteins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2012;367:2513–2516. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu JCC, Yamakoshi Y, Yamakoshi F, Krebsbach PH, Simmer JP. Proteomics and Genetics of Dental Enamel. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;181:219–231. doi: 10.1159/000091383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tagliabracci VS, et al. Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science. 2012;336:1150–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1217817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleland TP. Solid Digestion of Demineralized Bone as a Method to Access Potentially Insoluble Proteins and Post-Translational Modifications. Journal of Proteome Research. 2018;17:536–542. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antoine PO, et al. A revision of Aceratherium blanfordi Lydekker, 1884 (Mammalia: Rhinocerotidae) from the Early Miocene of Pakistan: postcranials as a key. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2010;160:139–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00597.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steiner CC, Ryder OA. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the Perissodactyla. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2011;163:1289–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00752.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobolth A, Dutheil JY, Hawks J, Schierup MH, Mailund T. Incomplete lineage sorting patterns among human, chimpanzee, and orangutan suggest recent orangutan speciation and widespread selection. Genome research. 2011;21:349–356. doi: 10.1101/gr.114751.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rieseberg LH. Evolution: replacing genes and traits through hybridization. Current Biology. 2009;19:R119–R122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guérin C. Les rhinocéros (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) du Miocène terminal au Pleistocène supérieur en Europe occidentale, comparaison avec les espèces actuelles. Documents du Laboratoire de Geologie de la Faculte des Sciences de Lyon. 1980;79:3–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deng T, et al. Out of Tibet: pliocene woolly rhino suggests high-plateau origin of Ice Age megaherbivores. Science. 2011;333:1285–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1206594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orlando L, et al. Ancient DNA analysis reveals woolly rhino evolutionary relationships. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2003;28:485–499. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan J, et al. Ancient DNA sequences from Coelodonta antiquitatis in China reveal its divergence and phylogeny. Science China Earth Sciences. 2014;57:388–396. doi: 10.1007/s11430-013-4702-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lordkipanidze D, et al. A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo. Science. 2013;342:326–331. doi: 10.1126/science.1238484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orlando L, et al. Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. Nature. 2013;499:74–78. doi: 10.1038/nature12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gabunia L, et al. Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science. 2000;288:1019–1025. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferring R, et al. Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:10432–10436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106638108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guérin C. Les rhinocéros (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) du Miocène terminal au Pleistocène supérieur en Europe occidentale, comparaison avec les espèces actuelles. Documents du Laboratoire de Geologie de la Faculte des Sciences de Lyon. 1980;79:3–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Penkman KEH, Kaufman DS, Maddy D, Collins MJ. Closed-system behaviour of the intra-crystalline fraction of amino acids in mollusc shells. Quaternary Geochronology. 2008;3:2–25. doi: 10.1016/j.quageo.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hendy J, et al. A guide to ancient protein studies. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2018;2:791–799. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nature Methods. 2009;6:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cappellini E, et al. Resolution of the type material of the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus Linnaeus, 1758 (Proboscidea, Elephantidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2014;170:222–232. doi: 10.1111/zoj.12084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kulak NA, Pichler G, Paron I, Nagaraj N, Mann M. Minimal, encapsulated proteomic-sample processing applied to copy-number estimation in eukaryotic cells. Nature Methods. 2014;11:319–324. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackie M, et al. Palaeoproteomic Profiling of Conservation Layers on a 14th Century Italian Wall Painting. Angewandte Chemie (International ed.) 2018;57:7369–7374. doi: 10.1002/anie.201713020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cappellini E, et al. Proteomic analysis of a pleistocene mammoth femur reveals more than one hundred ancient bone proteins. Journal of Proteome Research. 2012;11:917–926. doi: 10.1021/pr200721u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nature Biotechnology. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, et al. PEAKS DB: De novo sequencing assisted database search for sensitive and accurate peptide identification. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2012;11 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010587. M111.010587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.TheUniProtConsortium. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Leary NA, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:D733–D745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welker F, et al. Palaeoproteomic evidence identifies archaic hominins associated with the Châtelperronian at the Grotte du Renne. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113:11162–11167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605834113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabriels R, Martens L, Degroeve S. Updated MS2PIP web server delivers fast and accurate MS2 peak intensity prediction for multiple fragmentation methods, instruments and labeling techniques. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/544965. 544965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyanova S, Temu T, Cox J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nature Protocols. 2016;11:2301–2319. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Colaert N, Helsens K, Martens L, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K. Improved visualization of protein consensus sequences by iceLogo. Nature Methods. 2009;6:786–787. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1109-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korneliussen T, Albrechtsen A, Nielsen R. ANGSD: Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:356–356. doi: 10.1186/s12859-014-0356-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Briggs A, et al. Removal of deaminated cytosines and detection of in vivo methylation in ancient DNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:e87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI- BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.SeaUrchinGenomeSequencingConsortium. The Genome of the Sea Urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science. 2006;314:941–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1133609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katoh K, Frith MC. Adding unaligned sequences into an existing alignment using MAFFT and LAST. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3144–3146. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schliep KP. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:592–593. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guindon S, et al. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Systematic Biology. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rohland N, Hofreiter M. Comparison and optimization of ancient DNA extraction. BioTechniques. 2007;42:343–352. doi: 10.2144/000112383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyer M, Kircher M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2010 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schubert M, et al. Characterization of ancient and modern genomes by SNP detection and phylogenomic and metagenomic analysis using PALEOMIX. Nature Protocols. 2014;9:1056–1082. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows– Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dickinson MLA, Penkman K. A new method for enamel amino acid racemization dating: a closed system approach. Quaternary Geochronology. 2019;50:29–46. doi: 10.1016/j.quageo.2018.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository with the data set identifier PXD011008. Genomic BAM files used for Rhinocerotidae protein sequence translation and protein sequence alignments used for phylogenetic reconstruction are available on Figshare (doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7212746).

Code Availability

The in-house R-script used to align the peptide sequences confidently identified by the PEAKS searches is available to everyone upon request to the corresponding authors.