SUMMARY

Transporting epithelial cells like those that line the intestinal tract are specialized for solute processing and uptake. One defining feature is the brush border, an array of microvilli that serves to amplify apical membrane surface area and increase functional capacity. During differentiation, upon exit from stem cell-containing crypts, enterocytes build thousands of microvilli, each supported by a parallel bundle of actin filaments several microns in length. Given the high concentration of actin residing in mature brush borders, we sought to determine if enterocytes were resource (i.e. actin monomer) limited in assembling this domain. To examine this possibility, we inhibited Arp2/3, the ubiquitous branched actin nucleator, to increase G-actin availability during brush border assembly. In native intestinal tissues, Arp2/3 inhibition led to increased microvilli length on the surface of crypt, but not villus enterocytes. In a cell culture model of brush border assembly, Arp2/3 inhibition accelerated the growth and increased the length of microvilli; it also led to a redistribution of F-actin from cortical lateral networks into the brush border. Effects on brush border growth were rescued by treatment with the G-actin sequestering drug, Latrunculin A. G-actin binding protein, profilin-1, colocalized in the terminal web with G-actin, and knockdown of this factor compromised brush border growth in a concentration-dependent manner. Finally, the acceleration in brush border assembly induced by Arp2/3 inhibition was abrogated by profilin-1 knockdown. Thus, brush border assembly is limited by G-actin availability and profilin-1 directs unallocated actin monomers into microvillar core bundles during enterocyte differentiation.

Keywords: brush border, cytoskeleton, apical, intestine, crypt, villus

eTOC BLURB

Faust et al. show that the rate of brush border assembly is limited by G-actin availability and that profilin-1 directs unallocated G-actin into growing microvilli during enterocyte differentiation. These findings offer a framework for understanding how epithelial cells cope with the demands of building elaborate apical specializations.

INTRODUCTION

The most abundant intestinal epithelial cell type, nutrient-absorbing enterocytes, undergo a dramatic reorganization of their apical surface as they transition from crypt to villus during differentiation [1, 2]. During this period, filamentous actin (F-actin) bundle-supported membrane protrusions known as microvilli are formed and subsequently organized into highly ordered arrays known as the brush border. Large numbers of microvilli increase plasma membrane surface area, which optimizes solute transport capacity [3]. A single microvillus contains 20–30 actin filaments with barbed ends, the preferred sites of monomer addition, facing the plasma membrane at the distal tips [4, 5]. Biochemical studies on native brush border fractions revealed that actin filaments within microvilli are bundled by villin [6], fimbrin [7], and espin [8]. Bundles are tethered laterally to the overlaying plasma membrane by the actin-based motor, myo1a [9], as well as ezrin [10]. The pointed ends of core actin bundle filaments extend into a dense anastomosing meshwork of intermediate filaments, actin filaments, and spectrin, which together are believed to provide mechanical support for the apical domain [11, 12].

Although the structural components and ultrastructural architecture of the brush border are well studied, our understanding of mechanisms that control microvilli assembly during enterocyte differentiation remains less well defined. The assembly of complex actin networks is controlled predominately by actin nucleators, which include the branched network nucleator Arp2/3, and a diverse set of linear nucleators including formin family proteins and tandem Wiskott-Aldrich Homology 2 (WH2) domain-containing proteins [13, 14]. To date, the only factor with proven nucleation potential shown to impact the growth of microvilli is Cordon-Bleu (COBL) [15], which localizes to the pointed-ends of core actin bundles embedded in the terminal web [16–18]. The pointed-end localization of COBL is consistent with its potential to form actin seeds that subsequently elongate from both ends, but much faster from the barbed end [15]. COBL knockdown significantly impairs brush border assembly, whereas overexpression increases the actin content and length of microvilli in a manner that depends on its actin monomer-binding WH2 domains [18]. Conversely, molecules that promote actin core assembly specifically at the membrane-associated barbed-ends include the recently discovered insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate (IRTKS) and its binding partner epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (EPS8), which both contribute to the normal elongation of microvilli during brush border assembly [19]. Whether the IRTKS/EPS8 complex is capable of nucleating actin bundle formation de novo, or if these factors work in concert with a yet to be determined nucleator remains unclear. Once assembled, microvilli can exhibit robust turnover at steady-state. A number of previous FRAP studies on undifferentiated epithelial cell culture models show that microvilli exhibit a dynamic ‘treadmilling’ activity, with new G-actin inserting at microvilli tips, flowing through the bundle, and exiting at the pointed-ends [20–22]. This is also consistent with early studies that showed isolated brush borders retain the ability to elongate their actin bundles in vitro when soaked in G-actin [4, 23], with the barbed-ends at the distal tips serving as the preferred site of incorporation for new monomers.

Independent of nucleators and other molecular components that might control the elongation of microvilli, more recent studies indicate that actin network assembly may be regulated by G-actin availability, a paradigm we refer to herein as cellular ‘actin allocation’. In fission yeast, distinct polymerized actin networks appear to be in competition for a limited pool of G-actin [24]. Inhibition of Arp2/3-driven branched nucleation in endocytic patches using CK-666 promotes aberrant assembly of formin-based cables. This process requires cofilin, suggesting a large-scale remodeling of branched networks into the parallel bundles that comprise cables. Furthermore, in yeast and cultured fibroblasts, the G-actin-binding protein profilin acts as an assembly ‘gatekeeper’, directing G-actin into linear arrays nucleated by formins, while antagonizing Arp2/3-driven branched nucleation [25, 26].

Given the exceedingly high concentration of actin in brush borders, differentiating enterocytes may also be resource-limited in their ability to assemble microvilli. Classic studies by Stidwill and Burgess found that enterocytes in the developing chick embryo significantly upregulate actin expression concomitant with the elongation phase of microvilli growth [27], further suggesting that brush border assembly places a heavy burden on the cellular actin pool. We sought to test this concept directly in vivo, and in vitro using an epithelial cell culture model that affords control over brush border assembly. Our results establish actin allocation as a mechanism that controls the timing and extent of brush border assembly in vivo, and also implicates profilin as a factor that promotes the growth of microvilli actin cores in an Arp2/3-independent manner. These findings may also offer a framework for understanding how other epithelial cell types, such as the mechano-sensory hair cells of the inner ear, cope with the demands of assembling elaborate apical specializations.

RESULTS

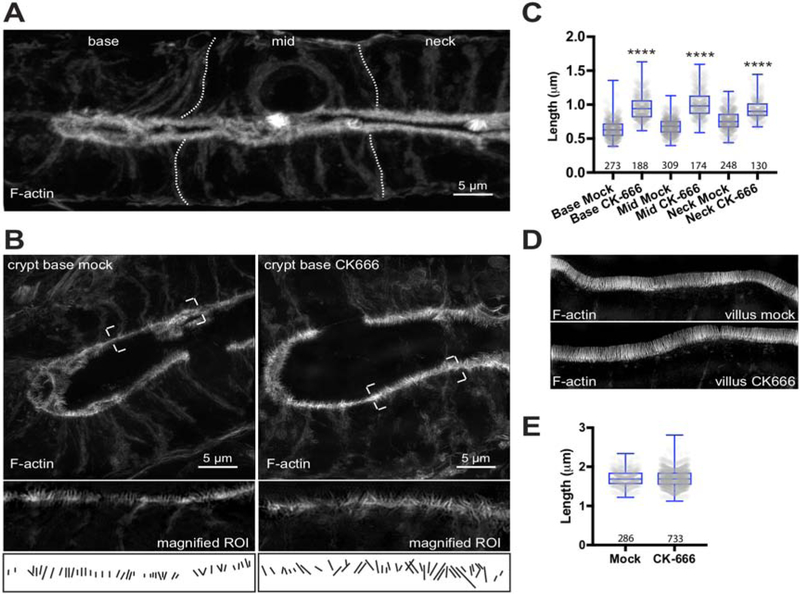

Arp2/3 inhibition increases microvilli length on crypt epithelial cells in vivo

To determine if G-actin availability limits microvilli growth during enterocyte differentiation, we used an in vivo system to examine how CK-666 exposure impacts microvilli structure. CK-666 is an Arp2/3 inhibitor [28] that has been used in previous studies to increase G-actin availability for other non-branched actin networks [24]. For these experiments we perfused 120 μM CK-666 in saline supplemented with efflux pump inhibitor verapamil, or saline-verapamil alone into the proximal jejunum of age and sex-matched mice. In confocal images of perfused tissue sections, brush borders labeled with fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin appear as an amorphous enrichment of apical signal. Since the diameter of a microvillus is below the diffraction limit, individual protrusions are not resolved (Figure 1A). The increase in resolution afforded by Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) (Figure 1B) allowed us to visualize and measure individual microvilli. Strikingly, when we compared microvilli lengths between mock and CK-666 perfused samples, we found a significant increase in length at the base, middle and neck regions of the crypt for CK-666 perfused samples (Figure 1B–C). In contrast, we observed no significant difference in microvilli length on villus enterocytes (Figure 1D,E). These initial results suggest that the elongation of microvilli on the surface of cells in the crypt, the site of brush border assembly, may be limited by G-actin availability.

Figure 1: Arp2/3 inhibition increases microvilli length in crypt, but not villus, enterocytes in vivo.

(A) Confocal image shows a diffraction-limited view of fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin (white) in a crypt from a mock specimen. Individual microvilli are not resolved in the diffraction-limited projection. Dotted lines indicate partitioning of the crypt for data analysis purposes. (B) SIM images show maximum intensity projections of mock (left) and 120 μM CK-666 treated (right) jejunum crypts. Lower panels show representative high magnification views of single optical sections used for data quantification. Manual traces are shown as a visual aid for length measurements. (C) Box and whisker plots of microvilli length in different regions of the crypt from mock and CK-666 treated animals; base, mid and neck correspond to labels in A. Boxes show 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile of the data distribution, whereas whiskers mark maximum and minimum values. Between 139–309 cell averages per condition were analyzed from 6 independent experiments; number of data points is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine significance (****p <0.0001). Significance asterisks represent a comparison to control sample. (D) SIM images show maximum intensity projections of mock (upper) and CK-666 treated (lower) villus enterocytes. (E) Box and whisker plots show villus microvilli length distributions from mock and 120 μM CK-666 treated samples; number of data points is given under each boxplot.

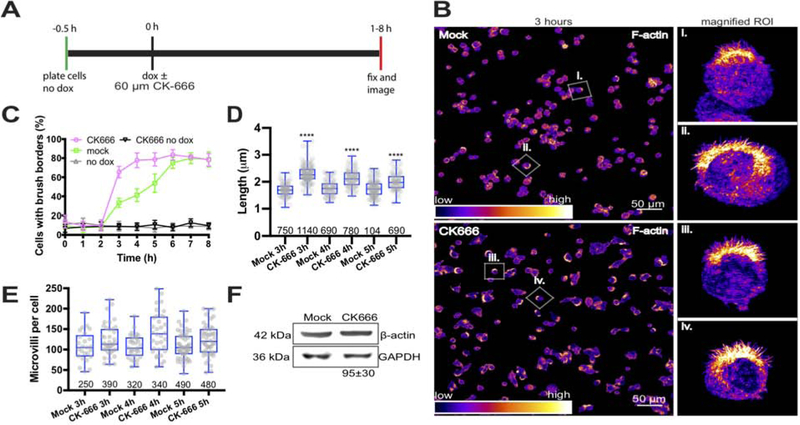

Arp2/3 inhibition accelerates brush border formation in W4 cells

To understand the mechanistic basis of microvilli elongation induced by CK-666 in vivo, we turned to the Ls174T-W4 (W4) human intestinal epithelial cell line as an in vitro model of brush border assembly [29]. W4 cells are p53 positive, E-cadherin negative and stably express STRADα and LKB1. Addition of doxycycline (Dox) to these cultures results in STRADα activation of LKB1 initiating a polarity program that culminates in brush border formation within hours [29]. W4 cells have been used by our group and others to reveal mechanistic details of polarity establishment and brush border formation, and are thought to mimic differentiating crypt enterocytes [18, 19, 29–33].

We first sought to determine if the microvilli elongation induced by CK-666 in vivo was recapitulated in the W4 cell system. To this end, we examined brush border assembly over an 8-hour period of differentiation. W4 cells were passaged, allowed to adhere for 30 minutes, and were then induced with Dox and 0.01% DMSO or Dox supplemented with 60 μM CK-666 and subsequently processed for microscopy (Figure 2A). Consistent with previous reports [18, 19, 29], in the absence of Dox only a small fraction of cells present with brush borders (~10%, Figure 2C). However, after the addition of Dox we observed a gradual increase in the percent of cells forming brush borders during the 8-hour period, finally reaching a plateau of ~80% at 6 hours (Figure 2C). In CK-666 treated W4 cells, we observed significant acceleration of brush border formation (Figure 2B,C). Indeed, after only 3 hours we observed a ~2-fold increase in the percent of brush borders formed in the presence of CK-666 (33 ± 5% mock vs. 65 ± 6% CK-666). We also noted significant increases in the length of microvilli as measured at the 3, 4, and 5-hour time points (Figure 2D). Thus, inhibition of Arp2/3 activity in cultured intestinal epithelial cells promotes brush border formation in a manner similar to that observed in vivo.

Figure 2: Arp2/3 inhibition accelerates brush border formation and increases microvilli length.

(A) Timing and detail of the experimental approach. (B) Low magnification confocal images of mock and 60 μM CK-666 treated W4 cells after 3 hours in doxycycline. Fluorescence intensities are heat-mapped to facilitate visualization; warmer colors correspond to higher intensities. Boxes in each image highlight cells shown in magnified views to the right. (C) Quantification of the percent of brush borders formed over 8 hours; 163–883 cells were scored per time point for each condition. (D) Box and whisker plots show microvilli length distributions from mock and 60 μM CK-666 treated cells after 3–5 hours of doxycycline treatment; number of data points is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001. Asterisks represent a comparison to mock samples. (E) Box and whisker plots show the number of microvilli per cell that form between 3–5 hours in doxycycline; number of data points is given under each boxplot. No significant differences were observed. (F) Representative western blot showing GAPDH (loading control) and β-actin levels in mock and CK-666 treated samples after 8 hours in doxycycline. Percentage relative to mock was generated from 3 independent experiments.

To test the possibility that CK-666 affected polarity establishment independent of LKB1 signaling, we applied 60 μM CK-666, but omitted Dox, and found no significant difference from uninduced specimens (Figure 2C). This indicates that Arp2/3 inhibition does not directly induce competition-based polarity programs [34]. We also observed no difference in the total number of microvilli per cell following CK-666 treatment (Figure 2E). Western blot analysis at the 8-hour endpoint also indicated that there was no significant difference in the total concentration of β-actin between samples (Figure 2F), suggesting that additional actin was not expressed during the experimental window.

G-actin sequestration with Latrunculin A rescues normal rates of brush border assembly in W4 cells treated with CK-666

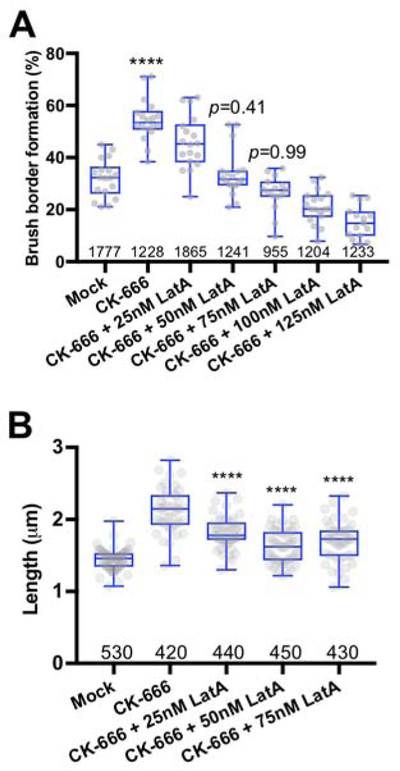

If the acceleration in brush border formation observed following Arp2/3 inhibition in vivo and in W4 cells is due to increased availability of actin monomers, we reasoned that monomer sequestration with Latrunculin A should return formation rates back to control level. Application of low levels of Latrunculin A abrogated the CK-666-induced increase in brush border formation at 3 hours (Figure 3A). Moreover, between 3–5 hours after Dox induction, microvilli lengths were significantly increased in CK-666 treated samples compared to mock controls, and this increase was partially rescued by Latrunculin A (Figure 3B). In these experiments, we noted that some W4 cells clearly had a polarized distribution of F-actin but had microvilli that were so short as to preclude measurement. This resulted in an overestimation of microvilli lengths in Latrunculin A-treated W4 cells. Based on these data we conclude that acceleration of brush border assembly in CK-666 treated cells is likely driven by G-actin released from Arp2/3-based networks.

Figure 3: Latrunculin A rescues normal rates of brush border assembly in W4 cells treated with CK-666.

(A) Box and whisker plots show the percent of brush borders formed in mock control cells, cells treated with 60 μM CK-666 alone, or cells treated with 60 μM CK-666 in combination with different concentrations of Latrunculin A, after 3 hours in doxycycline; number of measurements is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001. (B) Box and whisker plots show microvilli length distributions in mock samples, 60 μM CK-666 treated cells, and cells treated with CK-666 in combination with increasing concentrations of Latrunculin A, after 3 hours in doxycycline; number of measurements is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, **p < 0.0025, ****p < 0.0001. Asterisks represent significance relative to mock samples.

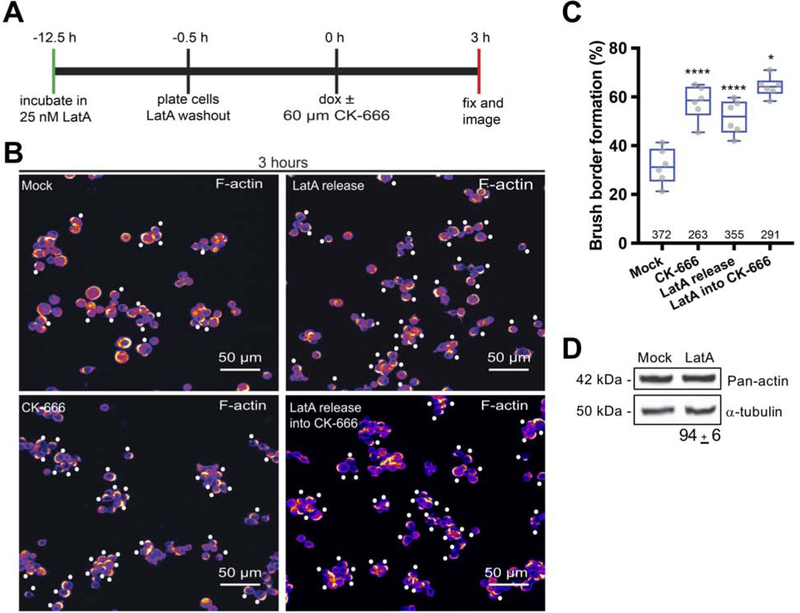

Release from long-term Latrunculin A treatment accelerates brush border formation in W4 cells

We next sought to determine if increasing G-actin availability by an alternative method to CK-666 treatment would similarly accelerate brush border formation. To this end, W4 cells were subjected to long-term G-actin sequestration with Latrunculin A [35]. We then examined brush border assembly following drug washout, which is expected to transiently increase G-actin availability. W4 cells were incubated for 12 hours in 25 nM Latrunculin A and polarized in the presence or absence of 60 μM CK-666 (Figure 4A). W4 cells released from Latrunculin A exhibited a response similar to that produced by CK-666 treatment alone; at 3 hours Latrunculin A release accelerated brush border formation (31 ± 7% mock vs. 51 ± 7% Latrunculin A; Figure 4B,C). We also observed a slight increase in the percent of brush borders formed when Latrunculin A release was followed by CK-666 treatment (Figure 4B,C). Western blotting of cell lysates revealed that long-term Latrunculin A treatment had no impact on total actin concentration (Figure 4D). Together these data indicate that brush border formation is normally limited by the availability of G-actin.

Figure 4: Brush border formation is accelerated following release from long-term Latrunculin A treatement.

(A) Timing and detail of the experimental approach. (B) Maximum intensity projections of confocal images of phalloidin-stained W4 cells used for quantifying percentage of brush border formation after 3 hours of doxycycline induction. For Latrunculin A release experiments, 25 nM Latrunculin A (LatA) was used. CK-666 was used at 60 μM; number of measurements is given under each boxplot. Fluorescent phalloidin intensity is heat-mapped such that warm colors represent high intensity and cool colors represent low intensity. White dots are positioned adjacent to W4 cells that are brush border-positive. (C) Box and whiskers plots show the percent of brush borders formed in mock control samples, cells treated with CK-666, cells released from long-term LatA treatment, and cells released from LatA into CK-666; number of data points is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001. Asterisks represent significance relative to control samples. (D) Representative western blot showing α-tubulin (loading control) and total actin levels in mock and long-term LatA-treated samples. Percentage relative to mock was generated from 3 independent experiments.

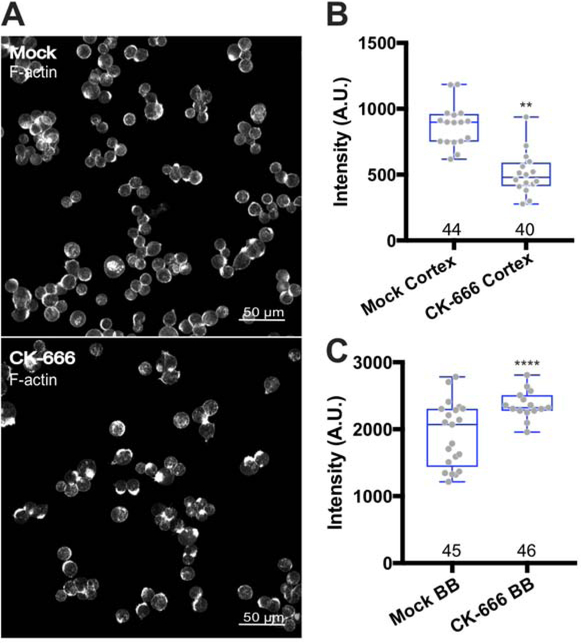

F-actin redistributes from lateral cortical networks into the brush border following CK-666 treatment

We hypothesized that the elongation of microvilli and accelerated brush border assembly following CK-666 treatment occurred at the expense of lateral/cortical F-actin networks, which are Arp2/3-dependent. To test this concept, we incubated W4 cells in 60 μM CK-666 with Dox to induce differentiation and then quantified phalloidin signal levels (representing all F-actin) from ROIs encompassing the lateral cortical domain or the brush border (Figure 5). W4 cells treated with CK-666 exhibited a striking redistribution of F-actin signal from the cortex (Figure 5B) into brush border microvilli (Figure 5C). Thus, following CK-666 inhibition, F-actin accumulation in the brush border occurs at the expense of Arp2/3-generated cortical F-actin, suggesting that the apical actin cytoskeleton and cortical lateral actin networks normally exist in homeostatic balance.

Figure 5: Arp2/3 inhibition increases brush border F-actin levels at the expense of basolateral cortical actin networks.

(A) Confocal images of phalloidin-stained mock and CK-666-treated W4 cells after 3 hours in doxycycline. (B) Distribution of phalloidin intensities in mock and CK-666-treated W4 cells, measured from ROIs drawn to surround the basolateral margin (i.e. cortex) of the cell; number of data points is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, **p < 0.0025. (C) Distribution of phalloidin intensities in mock and CK-666-treated W4 cells, measured from ROIs drawn to surround the brush border (BB); number of data points is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, **p < 0.0001.

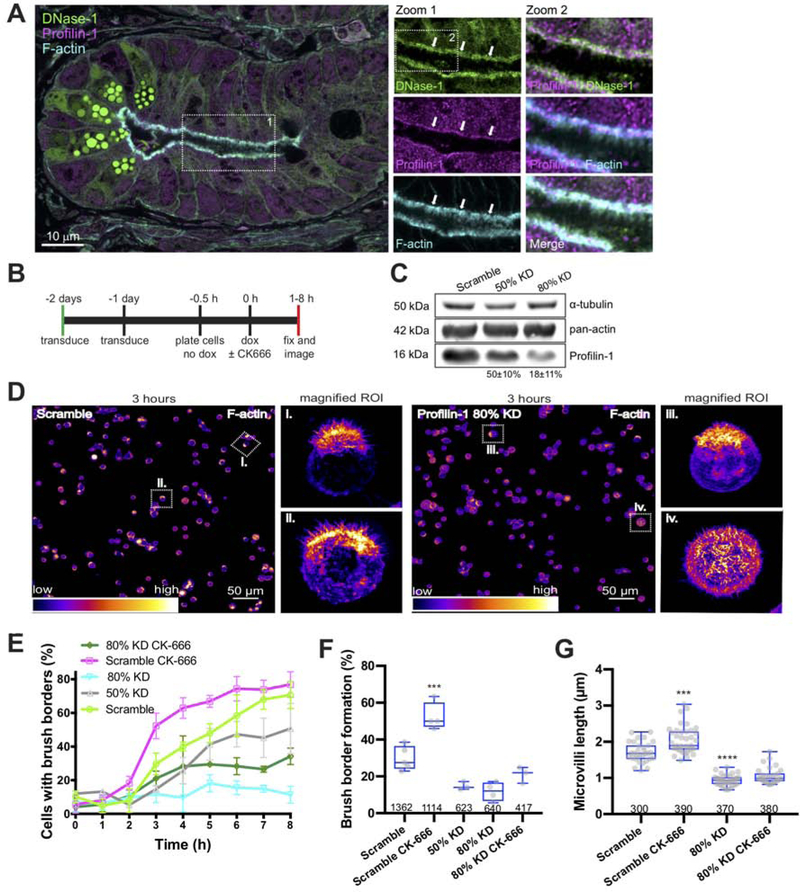

Profilin-1 is required for brush border formation

Recent studies indicate that the G-actin binding protein profilin-1 antagonizes Arp2/3-based network assembly by directing actin monomers into linear arrays [25, 26]. However, its role in the growth of brush border microvilli has not been examined. To determine if profilin-1 plays a role in brush border formation or the acceleration of this process in response to Arp2/3 inhibition, we first examined its distribution in differentiating cells of the crypt. In proximal jejunum tissue sections, we observed a layer of profilin-1 staining that exhibited striking colocalization with G-actin in the terminal web (white arrows; Figure 6A). We were also able to visualize robust enrichment of G-actin in the terminal web of polarized W4 cells (Figure S1). To examine the functional role of profilin-1, we performed knockdown in W4 cells by shRNA. We generated two W4 cell lines: one exhibiting ~50% depletion (50% KD) and a second line reporting ~80% depletion (80% KD) as determined by Western blotting (Figure 6C). We noted that brush border formation appeared to be dependent on the amount of profilin-1 in W4 enterocytes (Figure 6C–F). At 3 hours the percent of brush borders formed from 50% and 80% KD cells reported graded decreases relative to scramble control (14 ± 2%, 12 ± 5%, and 28 ± 6%, respectively, Figure 6F). In 80% KD W4 cells, we observed two distinct phenotypes. First, the minority of cells had a polarized F-actin signal with short, stubby microvilli (Figure 6D, panel iii). A second population of cells did not have polarized enrichment of F-actin, but demonstrated high levels of F-actin signal at the cortex (Figure 6D, panel iv). These data suggest that profilin-1 is required for brush border formation and, under normal conditions, suppresses the formation of lateral cortical actin structures that are generated by Arp2/3.

Figure 6: Profilin-1 is required for normal brush border formation.

(A) Confocal image of a single crypt from proximal jejunum showing localization of DNase-I (green), profilin-1 (magenta), and F-actin (cyan); white arrows in Zoom panels highlight terminal web enrichment of G-actin signal (DNase-I) and Profilin-1. (B) Timing and detail of the experimental approach. (C) Representative western blot showing α-tubulin (loading control), total actin and profilin-1 levels for different cell lines used in these experiments. The percentages shown were calculated from 3 independent experiments, normalized to α-tubulin levels, and calculated relative to scramble. (D) Low magnification fields of mock and profilin-1 80% KD cells after 3 hours of doxycycline induction. The boxed areas correspond to the higher magnification regions of interest shown to the right. (E) Percent brush border formation for scramble and profilin-1 KD cells in the presence or absence of CK-666; between 309–1362 cells were manually scored per time point for each condition. (F) Box and whisker plots show the percent of brush borders formed for each experimental condition after 3 hours in doxycycline; number of measurements is given under each boxplot. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001. (G) Box and whisker plots show microvilli length distributions for each experimental condition. ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, ****p < 0.0001. Asterisks represent significance relative to control samples. See also Figure S1.

CK-666-induced acceleration of brush border assembly requires profilin-1

To determine if profilin-1 plays a role in the enhancement of brush border formation induced by Arp2/3 inhibition, we applied CK-666 to profilin-1 KD cells. Importantly, application of CK-666 to 80% KD W4 cells no longer accelerated brush border formation as measured at the 3 hour timepoint (Figure 6F). Microvilli lengths were also significantly reduced for each condition by nearly 2-fold (Figure 6G). However, at 8 hours, a time point by which brush border formation is normally complete, 60 μM CK-666 stimulated low levels of brush border formation in KD cells (Figure 6E). Based on these data, we conclude that profilin-1 plays a critical role in directing actin monomers made available by Arp2/3 inhibition into the linear actin bundles found in brush border microvilli.

DISCUSSION

Microvilli on the surface of differentiating crypt cells are few in number, disorganized and short [36]. In contrast, the apical surfaces of differentiated villus enterocytes are saturated with tightly packed microvilli 1–2 microns in length [5]. To fuel this dramatic increase in the length and number of protrusions, differentiating cells must: (i) express higher levels of actin to accommodate the increased demand for subunits, and/or (ii) reallocate G-actin from pre-existing cytoskeletal structures. Indeed, studies indicate that β-actin is upregulated at both the mRNA [37] and protein levels during the crypt-villus transition [38]. In the present study, we also find clear evidence for the second possibility, i.e. that G-actin availability also controls the rate of brush border assembly as well as the length of assembled protrusions.

We manipulated G-actin availability by inhibiting one of the ubiquitous master regulators of actin assembly, Arp2/3. This strategy has been used successfully by others to probe actin network homeostasis in both fission yeast and fibroblast cells in culture [24, 25]. In epidermal cells, the Arp2/3 complex plays a major role in generating robust cell-cell contacts, as mice lacking this nucleator exhibit defective tight junctions [39]. This is consistent with other studies showing that Arp2/3 contributes to the formation of robust adherens junctions [40, 41]. Arp2/3 is also found at the lateral margins of cells where it likely contributes to maintaining the cortical actin meshwork that supports the plasma membrane [42, 43]. We used CK-666 in vivo and in the context of the W4 cell culture model to inhibit the maintenance of these networks, with the intention of increasing G-actin availability for microvilli assembly. In vivo, we find that microvilli on the surface of undifferentiated crypt cells, the site of brush border assembly, grow significantly longer following Arp2/3 inhibition (Figure 1). In W4 cells, the same treatment resulted in a striking acceleration of brush border assembly as well as an increase in microvilli length (Figure 2). These effects were reversible and could be rescued by sequestering G-actin with Latrunculin A (Figure 3). Notably, in W4 cells, we found no change in the number of microvilli assembled, as assessed by counting distal tip EPS8 puncta [19]. Together, these results suggest that under normal conditions, microvilli length and rate of assembly are limited by G-actin availability. These data further indicate that the number of microvilli per cell is controlled by other factors (more below). Previous studies with mice lacking ArpC3 (essential for Arp2/3 activity) revealed defects in membrane trafficking and transcytosis [44]. Remarkably, ultrastructural images of villus enterocytes from these animals suggested that microvilli were not impacted by loss of Arp2/3. However, quantification of the apical F-actin signal in these animals did reveal an increase in KO tissues [44], which would be consistent with our findings.

In native crypt cells and polarized W4 cells we noted an accumulation of G-actin in the terminal web region under normal conditions (Figure 6). Proteins seeking to gain access to the cytoplasm within microvilli and eventually, the barbed-ends of actin core bundles, must first pass through the terminal web. Thus, the observed pool of G-actin might represent a ‘depot’ for subunits that will eventually incorporate into core bundles. Interestingly, previous studies on axonal growth cones reported enrichment of G-actin near the cell periphery, where it contributes to rapid network assembly and protrusion of the leading edge [45]. G-actin enrichment in the terminal web may fulfill a similar role during brush border assembly.

How G-actin is anchored in the terminal web remains unclear, although our data indicate that the G-actin binding protein profilin-1 is also found in this region. Brush border assembly failed in profilin KD cells and CK-666 treatment was unable to rescue this effect (Figure 6). In combination, these results indicate that actin monomers made available by Arp2/3 inhibition are directed into the brush border cytoskeleton via a profilin-dependent mechanism. Consistent with our findings, previous studies from others have shown that profilin plays a key role in shunting G-actin into Arp2/3-independent networks [25, 26]. Although the identity of the nucleator(s) responsible for assembling microvilli actin filaments still remains unclear, past work has implicated the multi-WH2 domain containing protein COBL in this process [15–18]. In the W4 cell system, COBL KD reduces the fraction of cells capable of forming brush borders, whereas overexpression leads to remarkable increases in microvilli length, straightness and F-actin content [18]. Intriguingly, COBL is also enriched in the terminal web. Thus, one possibility is that profilin/G-actin interacts with COBL to promote microvilli assembly.

As alluded to above, our CK-666 inhibition studies in W4 cells demonstrate that microvilli length and the rate of brush border assembly are regulated via a mechanism that is distinct from that which controls the number of protrusions. How the growth of individual microvilli is initiated is not well understood, but classic ultrastructural studies revealed that a protein-rich, electron dense tip complex assembles on outwardly-curved regions of plasma membrane, and may serve as a nucleation site for nascent core actin bundles [46, 47]. This electron dense plaque can also be visualized at the tips of microvilli on the surface of differentiated villus enterocytes [5], suggesting that it might also play a role in the maintenance of these structures. Interestingly, recent studies have begun to identify factors that target to the distal tips of these protrusions and hold the potential to modulate actin assembly. Insulin Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Substrate (IRTKS, also known as BAIAP2L1) is one example, containing an I-BAR domain that interacts with outwardly curving plasma membrane as well as a single WH2 domain that interacts with actin. Previous work from our group shows that IRTKS promotes the elongation of microvilli to their normal length [19], although its role in growth initiation has yet to be investigated. Future studies must focus on understanding the earliest events in brush border assembly and how these early events may be modulated by actin allocation and other mechanisms that control the location, timing, rate and extent of microvilli growth.

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Requests for reagents and resources should be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the Lead Contact, Matthew J. Tyska (Matthew.Tyska@Vanderbilt.Edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

C57BL/6J mice (Mm, Jackson Labs) were given ad libitum access to food and water and housed on a 12–12 hour light-dark cycle. Age (6–8 weeks old) and sex-matched mice were used for each experiment.

Cell culture

Ls174T-W4 (W4, female Hs colon epithelial cells) cells were cultured according to the protocol developed by Baas et al. [29]. Briefly, cells were routinely maintained in DMEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/mL G-418 (RPI, G64000), 10 μg/mL blasticidin (Invivogen, ant-bl), 20 μg/mL phleomycin (Invivogen, ant-ph), and 10% tetracycline-free fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biological, S10350). Doxycycline (10 μg/mL, RPI, D43020) was added to induce brush border formation [29]. Cultures were stored in an incubator that maintained a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37 °C.

METHOD DETAILS

In vivo CK-666 treatment, animal surgery and tissue preparation

Animal surgery was conducted humanely according to NIH and AVMA guidelines by a protocol approved by Vanderbilt University IACUC. Mice were anesthetized with vaporized isoflurane (Piramal Healthcare, 66794-017-25) and proximal jejunum was exteriorized. Two 5 mm incisions were made 1 cm apart on the anti-mesenteric side of the jejunum to avoid vasculature on the mesenteric side. The luminal contents were flushed with normal saline and drug was perfused for 4 hours. Verapamil, a broad-spectrum efflux pump inhibitor (Sigma Aldrich, V1711202) was used at a 10 μM; CK666 (Millipore, 182515) was used at 120 μM. Animals were sacrificed by isoflurane overdose followed by cervical dislocation. Segments of jejunum were excised and cut along the length to exteriorize the lumen. Guts were fixed in 2% formaldehyde in 100 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.1) supplemented with 2 mM Ca2+/Mg2+ for 12 hours at 4 °C. After fixation, segments were washed with PBS and cut into pieces. Pieces were swirled in drops of OCT embedment medium (Sakura, 4583) and oriented in OCT-filled 0.8 mL centrifuge tubes to facilitate cutting through the crypt-villus axis. Samples were rapidly frozen and subsequently sectioned on a Leica cryotome operating at −18 °C. Sections (5 μm) were collected on high-stringency cover glass (Thor Labs, CG15CH) that was amino-silanized in-house.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

W4 cells were fixed with 1.6% formaldehyde in 100 mM PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.6% formaldehyde in ICB (5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM KCl, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 6.8) for 15 minutes at room temperature. The cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin in ICB for 15 minutes and labeled with fluorophore-conjugated Phalloidin (Thermo Scientific, A12380). After washing with ICB, cover glass was mounted on drops of Prolong Gold (P36930) and stored in the dark for 12 hours prior to imaging. For DNAse-I and antiprofilin-1 labeling, cells were fixed in 2% formaldehyde in 100 mM PBS for 12 hours and permeabilized with ice-cold acetone for 5 minutes. Alexa Fluor-488 conjugated DNase-I was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Thermo Scientific, D12371). Images were collected on a Nikon A1 laser scanning confocal microscope and deconvolved using Nikon Elements 5.0. Structured illumination microscopy (SIM) was conducted on an N-SIM housed in Vanderbilt’s Cell Imaging Shared Resource.

In vitro drug treatments

W4 cells were allowed to adhere to plasma treated cover glass for 30 minutes and 10 μg/mL doxycycline and drug were applied. CK-666 (Calbiochem, 182515) was reconstituted as a 60 mM stock in cell culture tested dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma Aldrich) and used at 60 μM. Latrunculin A (Invitrogen, L12370) was made 1 mM in DMSO and used at concentrations indicated in figures.

Brush border formation assay

Brush borders were induced for the indicated time points and immunofluorescent labeling was performed as described above. Cells were scored as brush border positive only if the cell contained a dense array of microvilli either exclusively at one end of the cell or at the apex of the cell as described previously [18, 19, 29]. Cells within a 40x field were scored and no fewer than 3 fields were selected randomly from 3 independent experiments.

Western blotting and antibodies

W4 cells were grown to ~80% confluence and removed from culture flasks with a Cell Lifter (Corning, 3008). Cells were pelleted at low speed at 4°C and subsequently lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with the cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 04 693 124 001) for 5 minutes. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 g and supernatant was refluxed in 4x sample buffer (Bio Rad, 1610747). Lysate was boiled for 5 minutes before running 10 μg of total protein on NuPage gels (Thermo Scientific, NP0321). Protein was transferred onto nitrocellulose according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (Thermo Scientific). Membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk, 0.01% Tween-20 for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated overnight in primary antibody. Anti-β-actin (Sigma Aldrich, A5316), anti-pan-actin (Cytoskeleton Inc., AAN01) anti-profilin-1 (Sigma Aldrich, P7624), anti-α-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, B-5-1-2) and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Inc., 14C10) were used according to manufacturer’s guidelines. IRDye 800cw (LI-CORE, 926–32211, 926–32210) goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies were used at a 1:2,000 dilution for 1 hour. Blots were scanned on an Odyssey reader in Automatic mode.

shRNA knockdown

Glycerol stocks of bacteria containing pLKO.1 shRNA expression vectors (Sigma Aldrich, TRCN0000062803 and TRCN0000062805) were used to generate lentiviral particles. shRNA plasmid was mixed with packaging and envelop plasmids and transfected into HEK293T cells as described elsewhere [19]. Supernatant containing lentivirus was concentrated with Lenti-X concentrator (Takara Biosciences, 631231) 48 hours after transfection. To generate stable cell lines, lentivirus was applied to cells in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma Aldrich, H9268) and selected with 10 μg/mL puromycin (Invivogen, ant-pr) daily for 14 days. After selection with puromycin, we obtained stable cell lines that were routinely ≥ 50% KD for profilin-1 as determined by Western blot densitometry. This cell line is referred to in the manuscript as ‘50% KD’. To bring cellular concentrations of profilin-1 to <20% control concentrations, we further transduced TRCN0000062803 particles on top of the TRCN0000062805 stable background 48 hours prior to experimentation (referred to as ‘80% KD’).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All image analysis and signal intensities measurements from image data were performed using FIJI or Nikon Elements software. Unless indicated otherwise, data shown represent median ± standard deviation from at least 3 independent experiments. Analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test using GraphPad Prism 8.1.2 software. Data were considered significantly different at p < 0.05. Statistical tests

Microvilli length measurements

To avoid orientation artifacts associated with microvilli length measurements in tissue, we used F-actin signal in optical sections that included only in-plane microvilli. Length was manually measured in Fiji [48] using the measure function. Microvilli lengths represent cell averages from 10–20 randomly sampled protrusions. In tissue experiments, measurements were repeated six times and 3–6 crypts per experiment were scored. For length measurements in W4 cells, 10 microvilli were sampled evenly spaced throughout the brush border. Even sampling resulted in normally distributed length measurements, which were averaged on a cell-by-cell basis.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

No large-scale datasets or new code were generated in this study.

Supplementary Material

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-β-actin | Sigma Aldrich | A5316 |

| anti-pan-actin | Cytoskeleton Inc. | AAN01 |

| anti-α-tubulin | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | B-5-1-2 |

| anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling Inc. | 14C10 |

| anti-profilin-1 | Sigma Aldrich | P7624 |

| anti-G-actin | DSHB | JLA20 |

| Donkey anti-mouse 800 IRdye | LI-COR Biosciences | 926–32212 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit 800 IRdye | LI-COR Biosciences | 926–32213 |

| Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11008 |

| Goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11011 |

| Chemicals | ||

| CK-666 | Calbiochem | 182515 |

| Verapamil | Sigma Aldrich | V1711202 |

| Latrunculin A | Thermo Fisher Scientific | L12370 |

| Blasticidin | Invivogen | Ant-bl |

| Phleomycin | Invivogen | Ant-ph |

| Doxycycline | RPI | D43020 |

| G418 | RPI | G64000 |

| Isoflurane | Piramal Healthcare | 66794-017-25 |

| TET-free FBS | Atlanta Biological | S10350 |

| FuGENE 6 | Promega | E2691 |

| Polybrene | Sigma Aldrich | TR-1003-G |

| Probes | ||

| Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A12379 |

| Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A12380 |

| Deoxyribonuclease I, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | D12371 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| LS174T-W4 | Dr. Hans Clevers | [29] |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mus Musculus (C57BL/6J) | Jackson Laboratory | 000664 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLKO.1 (profilin-1 KD) | Sigma Aldrich | TRCN0000062803 |

| pLKO.1 (profilin-1 KD) | Sigma Aldrich | TRCN0000062805 |

| pLKO.1 (scramble) | Dr. David Sabatini | Addgene #1864 |

| psPAX2 packaging plasmid | Dr. Didier Trono | Addgene #12260 |

| pMD2.G | Dr. Didier Trono | Addgene #12259 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| FIJI | https://fiji.sc | N/A |

| NIS AR Elements Analysis | Nikon | N/A |

| Prism 8.1.2 | www.graphpad.com | N/A |

HIGHLIGHTS.

Inhibition of Arp2/3 accelerates growth of microvilli in vivo and in vitro

Inhibition of Arp2/3 redistributes F-actin from the cortex into microvilli

Profilin-1 is required for normal brush border assembly

Acceleration of microvilli growth upon inhibition of Arp2/3 requires profilin-1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank members of the Tyska Laboratory and the Vanderbilt Epithelial Biology Center for helpful discussion of this work. We are grateful to Dr. Jim Goldenring and Jamie Adcock for providing advice regarding animal surgery. We thank Dr. Dylan Burnette for experimental suggestions. Microscopy was performed in part through the Vanderbilt University Cell Imaging Shared Resource. These studies were supported in part by a T32 Fellowship 5T32DK007569-28 to JJF, and NIH grants R01-DK095811 and R01-DK111949 to MJT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Delacour D, Salomon J, Robine S, and Louvard D (2016). Plasticity of the brush border - the yin and yang of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 13, 161–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawley SW, Mooseker MS, and Tyska MJ (2014). Shaping the intestinal brush border. J Cell Biol 207, 441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helander HF, and Fandriks L (2014). Surface area of the digestive tract - revisited. Scand J Gastroenterol 49, 681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollard TD, and Mooseker MS (1981). Direct measurement of actin polymerization rate constants by electron microscopy of actin filaments nucleated by isolated microvillus cores. J Cell Biol 88, 654–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mooseker MS, and Tilney LG (1975). Organization of an actin filamentmembrane complex. Filament polarity and membrane attachment in the microvilli of intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 67, 725–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bretscher A, and Weber K (1979). Villin: the major microfilament-associated protein of the intestinal microvillus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76, 2321–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bretscher A, and Weber K (1980). Fimbrin, a new microfilament-associated protein present in microvilli and other cell surface structures. J Cell Biol 86, 335–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartles JR, Zheng L, Li A, Wierda A, and Chen B (1998). Small espin: a third actin-bundling protein and potential forked protein ortholog in brush border microvilli. J Cell Biol 143, 107–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyska MJ, Mackey AT, Huang JD, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, and Mooseker MS (2005). Myosin-1a is critical for normal brush border structure and composition. Mol Biol Cell 16, 2443–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould KL, Cooper JA, Bretscher A, and Hunter T (1986). The protein-tyrosine kinase substrate, p81, is homologous to a chicken microvillar core protein. J Cell Biol 102, 660–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimm-Gunter EM, Revenu C, Ramos S, Hurbain I, Smyth N, Ferrary E, Louvard D, Robine S, and Rivero F (2009). Plastin 1 binds to keratin and is required for terminal web assembly in the intestinal epithelium. Mol Biol Cell 20, 2549–2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirokawa N, Tilney LG, Fujiwara K, and Heuser JE (1982). Organization of actin, myosin, and intermediate filaments in the brush border of intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 94, 425–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dominguez R (2009). Actin filament nucleation and elongation factors--structure-function relationships. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 44, 351–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chesarone MA, and Goode BL (2009). Actin nucleation and elongation factors: mechanisms and interplay. Curr Opin Cell Biol 21, 28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahuja R, Pinyol R, Reichenbach N, Custer L, Klingensmith J, Kessels MM, and Qualmann B (2007). Cordon-bleu is an actin nucleation factor and controls neuronal morphology. Cell 131, 337–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wayt J, and Bretscher A (2014). Cordon Bleu serves as a platform at the basal region of microvilli, where it regulates microvillar length through its WH2 domains. Mol Biol Cell 25, 2817–2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grega-Larson NE, Crawley SW, and Tyska MJ (2016). Impact of cordonbleu expression on actin cytoskeleton architecture and dynamics. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 73, 670–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grega-Larson NE, Crawley SW, Erwin AL, and Tyska MJ (2015). Cordon bleu promotes the assembly of brush border microvilli. Mol Biol Cell 26, 3803–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postema MM, Grega-Larson NE, Neininger AC, and Tyska MJ (2018). IRTKS (BAIAP2L1) Elongates Epithelial Microvilli Using EPS8-Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Curr Biol 28, 2876–2888 e2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyska MJ, and Mooseker MS (2002). MYO1A (brush border myosin I) dynamics in the brush border of LLC-PK1-CL4 cells. Biophys J 82, 1869–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waharte F, Brown CM, Coscoy S, Coudrier E, and Amblard F (2005). A two-photon FRAP analysis of the cytoskeleton dynamics in the microvilli of intestinal cells. Biophys J 88, 1467–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loomis PA, Zheng L, Sekerkova G, Changyaleket B, Mugnaini E, and Bartles JR (2003). Espin cross-links cause the elongation of microvillus-type parallel actin bundles in vivo. J Cell Biol 163, 1045–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooseker MS, Pollard TD, and Wharton KA (1982). Nucleated polymerization of actin from the membrane-associated ends of microvillar filaments in the intestinal brush border. J Cell Biol 95, 223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke TA, Christensen JR, Barone E, Suarez C, Sirotkin V, and Kovar DR (2014). Homeostatic actin cytoskeleton networks are regulated by assembly factor competition for monomers. Curr Biol 24, 579–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suarez C, Carroll RT, Burke TA, Christensen JR, Bestul AJ, Sees JA, James ML, Sirotkin V, and Kovar DR (2015). Profilin regulates F-actin network homeostasis by favoring formin over Arp2/3 complex. Dev Cell 32, 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rotty JD, Wu C, Haynes EM, Suarez C, Winkelman JD, Johnson HE, Haugh JM, Kovar DR, and Bear JE (2015). Profilin-1 serves as a gatekeeper for actin assembly by Arp2/3-dependent and -independent pathways. Dev Cell 32, 54–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stidwill RP, and Burgess DR (1986). Regulation of intestinal brush border microvillus length during development by the G- to F-actin ratio. Dev Biol 114, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolen BJ, Tomasevic N, Russell A, Pierce DW, Jia Z, McCormick CD, Hartman J, Sakowicz R, and Pollard TD (2009). Characterization of two classes of small molecule inhibitors of Arp2/3 complex. Nature 460, 1031–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baas AF, Kuipers J, van der Wel NN, Batlle E, Koerten HK, Peters PJ, and Clevers HC (2004). Complete polarization of single intestinal epithelial cells upon activation of LKB1 by STRAD. Cell 116, 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gloerich M, Ten Klooster JP, Vliem MJ, Koorman T, Zwartkruis FJ, Clevers H, and Bos JL (2012). Rap2A links intestinal cell polarity to brush border formation. Nat Cell Biol 14, 793–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruurs LJ, Donker L, Zwakenberg S, Zwartkruis FJ, Begthel H, Knisely AS, Posthuma G, van de Graaf SF, Paulusma CC, and Bos JL (2015). ATP8B1-mediated spatial organization of Cdc42 signaling maintains singularity during enterocyte polarization. J Cell Biol 210, 1055–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruurs LJM, Zwakenberg S, van der Net MC, Zwartkruis FJ, and Bos JL (2017). A Two-Tiered Mechanism Enables Localized Cdc42 Signaling during Enterocyte Polarization. Mol Cell Biol 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruurs LJM, van der Net MC, Zwakenberg S, Rosendahl Huber AKM, Post A, Zwartkruis FJ, and Bos JL (2018). The Phosphatase PTPL1 Is Required for PTEN-Mediated Regulation of Apical Membrane Size. Mol Cell Biol 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lomakin AJ, Lee KC, Han SJ, Bui DA, Davidson M, Mogilner A, and Danuser G (2015). Competition for actin between two distinct F-actin networks defines a bistable switch for cell polarization. Nat Cell Biol 17, 1435–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coue M, Brenner SL, Spector I, and Korn ED (1987). Inhibition of actin polymerization by latrunculin A. FEBS Lett 213, 316–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fath KR, Obenauf SD, and Burgess DR (1990). Cytoskeletal protein and mRNA accumulation during brush border formation in adult chicken enterocytes. Development 109, 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mariadason JM, Nicholas C, L’Italien KE, Zhuang M, Smartt HJ, Heerdt BG, Yang W, Corner GA, Wilson AJ, Klampfer L, et al. (2005). Gene expression profiling of intestinal epithelial cell maturation along the crypt-villus axis. Gastroenterology 128, 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang J, Chance MR, Nicholas C, Ahmed N, Guilmeau S, Flandez M, Wang D, Byun DS, Nasser S, Albanese JM, et al. (2008). Proteomic changes during intestinal cell maturation in vivo. J Proteomics 71, 530–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou K, Muroyama A, Underwood J, Leylek R, Ray S, Soderling SH, and Lechler T (2013). Actin-related protein2/3 complex regulates tight junctions and terminal differentiation to promote epidermal barrier formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, E3820–3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma S, Shewan AM, Scott JA, Helwani FM, den Elzen NR, Miki H, Takenawa T, and Yap AS (2004). Arp2/3 activity is necessary for efficient formation of E-cadherin adhesive contacts. J Biol Chem 279, 34062–34070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovacs EM, Goodwin M, Ali RG, Paterson AD, and Yap AS (2002). Cadherin-directed actin assembly: E-cadherin physically associates with the Arp2/3 complex to direct actin assembly in nascent adhesive contacts. Curr Biol 12, 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mullins RD, Stafford WF, and Pollard TD (1997). Structure, subunit topology, and actin-binding activity of the Arp2/3 complex from Acanthamoeba. J Cell Biol 136, 331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roh-Johnson M, and Goldstein B (2009). In vivo roles for Arp2/3 in cortical actin organization during C. elegans gastrulation. J Cell Sci 122, 3983–3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou K, Sumigray KD, and Lechler T (2015). The Arp2/3 complex has essential roles in vesicle trafficking and transcytosis in the mammalian small intestine. Mol Biol Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee CW, Vitriol EA, Shim S, Wise AL, Velayutham RP, and Zheng JQ (2013). Dynamic localization of G-actin during membrane protrusion in neuronal motility. Curr Biol 23, 1046–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tilney LG, and Cardell RR (1970). Factors controlling the reassembly of the microvillous border of the small intestine of the salamander. J Cell Biol 47, 408–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Begg DA, Rebhun LI, and Hyatt H (1982). Structural organization of actin in the sea urchin egg cortex: microvillar elongation in the absence of actin filament bundle formation. J Cell Biol 93, 24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No large-scale datasets or new code were generated in this study.