Abstract

Objectives

The study systematically reviewed the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments alone or combined with brief cognitive-behavioural therapy (BCBT) for treating Iranian amphetamine abusers. The secondary aim was to review the efficacy of BCBT alone or combined with pharmacological treatments for treating amphetamine abusers in the world.

Evidence acquisition

Published trials were considered for inclusion. The review was conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Web of Science, MEDLINE (via PubMed), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group’s Specialised Register of Trials, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, PsychINFO, Iran Medex, Magiran and the Scientific Information Database were searched (January 2001 to March 2019). The reference lists of included studies were hand searched for more information. A systematic literature search in eight databases produced 10 trials.

Results

Risperidone reduced positive psychotic symptoms while aripiprazole reduced negative psychotic symptoms. Methylphenidate reduced craving and depression compared with placebo. Topiramate reduced addiction severity and craving for methamphetamine abuse compared with placebo. Buprenorphine reduced methamphetamine craving more than methadone. Haloperidol and risperidone reduced psychosis. Riluzole reduced craving, withdrawal, and depression compared with placebo. Abstinence from amphetamine or reduction in amphetamine abuse was confirmed in four BCBT studies and one study which applied BCBT with a pharmacological treatment which were stable between two and 12-months. Other changes in BCBT studies were as follows: reduced polydrug use; drug injection, criminality and severity of amphetamine dependence at six-month follow-up; improved general functioning; mental health; stage of change as well as improved motivation to change in a pharmacological + BCBT study.

Conclusion

A review of trials indicates that pharmacological treatments and BCBT in a research setting outperform control conditions in treating amphetamines abuse and associated harms. Large-scale studies should determine if both treatments can be effective in clinical settings.

Keywords: Amphetamine, Pharmacological treatments, Systematic review

Objectives

Amphetamines including methamphetamine (MA) are a global health problem and there is concern that amphetamines abuse will continue, despite awareness of multiple harms [1]. After cannabis, amphetamines are the most commonly consumed illicit substances in the world [2]. Amphetamine abuse has been also recently reported among Iranian illicit drug abusers [3]. In addition, amphetamines abuse remains a health concern in Iran and has impacted some Iranian populations [3].

There are some suggested pharmacological medications for treating amphetamines abuse [4] which may be used alone or in combination with long-term behavioral interventions [5, 6]. However, using long-term behavioral interventions with pharmacological treatments has several important operational barriers to implementation [7]. Firstly, such behavioural interventions remain unaffordable for most patients [8]. Secondly, most long-term behavioural interventions need intensive staff training and/or client supervision [8]. Finally, the accessibility of such treatments remains difficult for a large proportion of patients in the community [8]. Therefore, brief cognitive-behavioural therapy (BCBT) has been introduced by Baker and colleagues for treating amphetamines abuse/use disorder to overcome these operational barriers to implementation [9]. Pharmacological treatments combined with BCBT remain cost-effective for drug treatment systems, due to the limited number of treatment sessions and the efficacy of use [9]. Moreover, high quality in implementing the treatment can be ensured due to tailoring the treatment to the needs of each individual [9]. Furthermore, using pharmacological treatments combined with BCBT is applicable to a broad range of patients due to the practical techniques and skills that such therapies impart to patients [10]. To date, there are no systematic reviews that specifically show the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments alone or in combination with BCBT in treating Iranian amphetamine abusers. To date, there is no systematic review to specifically show the efficacy of BCBT for treating amphetamines abusers in the world. In other words, it is not documented how BCBT is efficacious for treating amphetamine abuse/use disorder alone or in combination with pharmacological treatments in other countries. The current systematic review aims to address these two gaps in the research literature.

Evidence acquisition

Search strategy

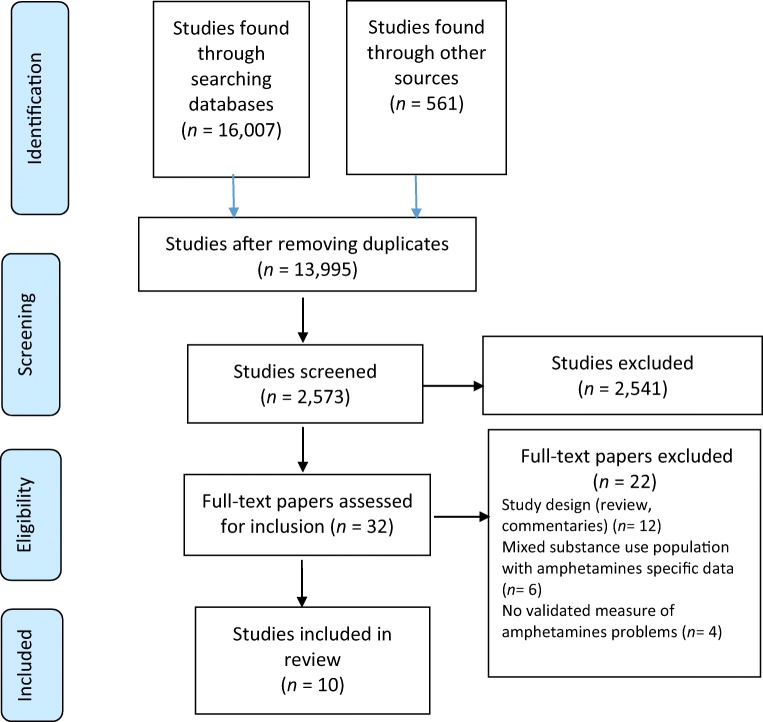

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [11] for conducting the review. The following electronic libraries (January 2001 to March 2019) were searched: Web of Science, MEDLINE (via PubMed), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group’s Specialised Register of Trials, Embase, CINAHL (EBSCO), Scopus and PsychINFO. Then, Persian scientific databases were searched including Iran Medex, Magiran and the Scientific Information Database. Searching online databases was based on medical subject headings and free-text terms relating to amphetamines (see Appendix). The reference lists of included studies were hand searched for more studies. Figure 1 shows the progress of systematic searching. As displayed in Fig. 1, in the first step, 13,955 studies were excluded because they were not related to the study aims. In the second step, 2541 studies were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. In the last step, 22 studies were excluded due to the reasons explained in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The process of searching

Inclusion criteria

Papers needed to be published either in English or have a published abstract in English. Persian was selected as another language for the inclusion of the abstracts and papers in this study, especially for searching in Iranian journals databases. The diagnosis of an amphetamine problem (abuse, dependence or use disorder) needed to be confirmed according to a validated measure such as different versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Randomised clinical or controlled trials (RCTs) were selected if they were related to one of the study aims. Any type of pharmacological treatment for an amphetamine problem was acceptable for study inclusion. BCBT needed to be conducted in agreement with the principles of Baker and colleagues’ treatment guide [9]. BCBT refers to teaching patients to identify, evaluate and respond to their dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs and use a number of techniques to change thinking, mood and behaviours in less than ten session of psychotherapy [9]. Original RCTs were included if the control groups had no treatment or received treatment as usual. Studies needed to report at least one primary outcome measure (see the list of primary outcomes in Box 1). If reported in the studies, secondary outcome measures were also considered for inclusion (see Box 1). Those original RCTs without no clear description of the methods of a pharmacological treatment and/or BCBT and the modes of delivery were excluded. Contacting authors was considered if needed. Due to sufficient information, authors were not contacted. Reviews, case reports and commentaries were excluded. Studies were excluded if they used pharmacological treatments with other psychological and behavioral treatments.

Box 1.

Data elicited for analysis

| Participants | |

|

A. Participant information 1 B. Type of amphetamines consumed C. Eligibility criteria | |

| Design of study | |

|

A. Study settings B. Country of origin C. Types of materials 2 D. Number and duration of sessions 2 E. Number of assessment points F. Percentage of post-treatment data G. Percentage of data at the longest follow-up H. Funding sources I. Harms and/or benefits | |

| Outcome measures * | |

| Primary outcome measures | |

|

A. Abstinence from amphetamines B. Reduced amphetamine symptoms (including craving, withdrawal, overdose or psychosis) C. The longest duration of abstinence from amphetamines | |

| Secondary outcome measures * | |

|

A. Abstinence from any substance 3 B. Reduced or treated B1. substance problems 3 B2. mental and/or physical health B3. criminality and/or violence B4. drug injection and/or high-risk sexual behaviours B5. impaired social or general functioning B6. poor quality of life B7. poor self-efficacy B8. poor readiness or motivation to change |

1This included n values and gender; 2 Treatment and control; 3 This issue included substance use, substance abuse, substance dependence or substance use disorders; * These issues also included methods of data assessment and reporting significant p values and the largest reported effect sizes at post-treatment and at follow-ups

Data extraction

Two reviewers participated in searching the literature (M.E and A.M; the firth author). Studies including titles and abstracts identified by electronic searches were assessed and screened by one author (M. E). Another independent reviewer (A. M; the fifth author) contributed to this procedure to reduce any selection bias. The full texts of the identified papers were assessed by two independent reviewers (M. K and M.R). All data extraction forms were checked by the reviewers. The data extracted for analysis are available in Box 1. The researchers were not blinded to the objectives of the study but they used the same criteria and worked on the review procedures independently. Any disagreement on the eligibility criteria was solved by discussion among the research team. All reviewers had at least four years of experience in the subject of the study.

Quality assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials was used for quality assessment [12]. Assessed issues were as follows: sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of patients and therapists (performance bias), blinding of outcome investigators (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) and other types of bias [12]. The risk of bias for that entry was also considered [12]. Quality assessment was done by two independent reviewers (S.S and A.M; the third author). There was no reported disagreement on quality assessment. The quality assessors had at least five years of experience in the subject of the study.

Qualitative data synthesis

Due to insufficient data needed for conducting a meta-analysis and lack of consistency in reporting the findings, only a systematic review was conducted. The reported effect sizes and/or p values were considered as effectiveness of a treatment. A small effect size was considered as 0.2–0.49, a moderate effect size was considered as 0.5–0.79 and a large effect size was greater than 0.80 [13]. Due to the limited number of included studies, calculating effect sizes was not feasible. Therefore, the reported effect sizes in the papers were specified.

Results

Trial flow

A systematic literature search produced ten RCTs. Tables 1 and 2 display assessing outcome measures and statistically significant effects in the studies.

Table 1.

Summary of pharmacological studies

| Study | Place | Sample | M/W a | Inclusion | Medications | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farnia et al. (2014) | Iran | 45 | Men | Meeting DSM-IV criteria for MA-induced psychosis | Risperidone vs. aripiprazole | Risperidone had better treatment effects on positive psychotic symptoms while aripiprazole had better treatment effects on negative psychotic symptoms |

| Rezaei et al. (2015) | Iran | 56 | Men | Meeting DSM-IV criteria for MA dependence, age between 18 and 65 years and positive urine tests for MA at the time of intake | Sustained-released methylphenidate vs. placebo | Less self-reported MA craving and depression in the treatment group than in the control group |

| Rezaei et al. 2016 | Iran | 62 | Men | Meeting DSM-IV criteria for MA dependence | Topiramate vs. placebo | Lower proportion of MA-positive urine tests in the Topiramate group than in the placebo group (p = 0.01). Lower scores in MA addiction severity (p < 0.001) and MA craving (p < 0.001) in the topiramate group than in the placebo group |

| Samiei et al. (2017) | Iran | 44 | 21 men and 13 women | Meeting DSM-IV criteria for MA dependence; age 18–60 years | Haloperidol vs. risperidone | Haloperidol (p < 0.05) and risperidone (p < 0.05) were similarly effective in the treatment of self-reported MAP but no differential effectiveness was found between the two medications. The treatment effects of both medications increased in the first two weeks of treatment and remained stable in the second two weeks |

| Ahmadi et al. (2017) | Iran | 40 | Men | Meeting DSM-V criteria for MA use disorder and withdrawal, seeking treatment, daily MA use for at least six month prior to intake | Methadone vs. buprenorphine | Reduction of craving in the buprenorphine group was significantly more (p < 0.05) than in the methadone group |

| Farahzadi et al. (2019) | Iran | 88 | Men | Meeting DSM-IV criteria for MA dependence; age 18–65 years | Riluzole vs. placebo | More weekly visits was higher in the riluzole group than in placebo group (riluzole, median (range) = 13.00; placebo = 4.00, p = 0.07), and the weekly measured rate of positive MA urine specimens was significantly lower in the riluzole group by the end of the study (riluzole = 1 (5.00%), placebo = 9 (45.00%), p = 0.004). Patients in the riluzole group self-reported greater reductions in craving, withdrawal, and depression from baseline to endpoint |

aThe ratio of men to women

Table 2.

Summary of other studies

| Study | Place | Sample | M/W % a | ATS b | Inclusion | Sessions | Stage | PT c | FU d | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. [20] | Australia |

N = 64; (treatment group: n = 32, control group: n = 32); mainly out of treatment |

61.9: 38.1 |

RAU e | At least monthly use: a score of at least 0.14 and more on the OTI f | BCBT (i.e., 2 or 4 sessions) + a MA g self-help booklet vs. the same self-help booklet) | Pre-treatment + six-month follow-up | – | 81.3 | Abstinence from amphetamine (the treatment group: 58.3% vs. the control group: 21.4%, p < 0.01) at six-month follow-up; those participants who completed 3–4 treatment sessions (85.7%) were more likely than the control group (21.4%) to report abstinence from amphetamine (p < 0.01); a more significant reduction in daily amphetamine use in the treatment group than in the control group at six-month follow-up. Reduced daily polydrug use; cannabis and tobacco use in both groups; more psychological well-being (p < 0.01); reductions (p < 0.01) in drug injection and criminality, improved general functioning and stage of change |

| Baker et al. [21] | Australia | N = 214; (group 1: n = 74 h, group 2: n = 66 i, control group: n = 74); mainly out of treatment |

62.6: 37.4 |

RAU | At least weekly use: a score of at least 0.14 and more on the OTI | BCBT (i.e., 2 or 4 sessions) + a MA self-help booklet vs. the same self-help booklet) | Pre-treatment; post-treatment (5 weeks later); 6-month follow-up | 71.9 | 72.4 | Higher rates of abstinence from amphetamine by completing two and more treatment sessions (40.8%) or four treatment sessions (37.9%) compared with the control group (17.6%) (p < 0.01); a more significant reduction in daily amphetamine use in the treatment group than in the control group at six-month follow-up. Those participants who completed 3–4 treatment sessions were more likely than the control group to report a significant reduction in daily polydrug use at six-month follow-up; reductions (p < 0.001) in the severity of amphetamine dependence, criminality and drug injection as well as improved general functioning, stage of change and psychological well-being at six-month follow-up. |

| Baker et al. [22] | Australia | N = 130; (treatment group: n = 65, control group: n = 65); a community sample of people with a psychotic disorder |

78.2: 21.8 |

RAU or regular use of cannabis or alcohol or dependence on one of these drugs | At least weekly use of cannabis, alcohol or amphetamine on the OTI; age at least 15 years; ability to speak English; and a confirmed ICD–10 j psychotic disorder | 4 sessions of MI k and 6 sessions of BCBT + a MA self-help booklet vs. a control condition | Baseline + post-treatment (15 weeks later) + 6- and 12-month follow-ups | 91.5 | 74.6 | Among treatment completers, abstinence from amphetamine was confirmed at 15-week post-treatment (treatment group: 54.5% vs. control group: 44.4%), at six-month (treatment group: 45.5% vs. control group: 44.4%) and at 12-month (treatment group: 55.6% vs. control group: 87.5%) follow-ups with no significant between-group differences; a more significant reduction in daily amphetamine use in the treatment group than in the control group at 12-month follow-up. The control group was more likely than the treatment group to report reduced alcohol consumption between baseline and 12-month follow-up. The treatment group was more likely than the control group to report a significant reduction in depression over the same time |

| Suvanchot et al. [23] | Thailand |

N = 200; (treatment group: n = 100, control group: n = 100); hospitalised psychiatric patients |

N/A | RAU | At least monthly amphetamine use, depression and anxiety assessed by the MINI l, TLFB m, HAS n and HDS o | 4 sessions of group MI + BCBT + usual care vs. usual care | Pre-treatment +3 follow-ups (2, 4, and 6 months after baseline) | – | 89.0 | More negative urine specimens for amphetamine (treatment group: 44.5% vs. control group: 13.2%, p < 0.01) at two-month follow-up; the amount and the number of days of self-reported daily amphetamine use were reduced from baseline to six-month follow-up with no significant between-group differences. The treatment group was more likely than the control group to self-report motivation to change and self-efficacy to manage an amphetamine problem at six-month follow-up. |

aThe ratio of men to women. b Amphetamine type stimulants (at baseline). c Post-treatment data (provided by the participants). d The longest follow-up (percentage of the followed participants). e Regular amphetamine use. f Opiate Treatment Index. g Methamphetamine. h Group 1: two BCBT sessions. i Group 2: four BCBT sessions. j the International Classification of Diseases-10. k Motivational interviewing. l the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. m Timeline Follow Back. n Hospital Anxiety Scale. o Hospital Depression Scale

Qualitative data synthesis

Low risk was identified in all studies [14–22] due to appropriate designs. Unclear risk was identified in one study [23] due to insufficient description of group allocation.

Study characteristics

Baseline characteristics

Most participants were patients with high rates of daily amphetamine use and mental health problems [14–23]. None of the publications reported any adverse effects of pharmacological treatments alone or with BCBT [14–23]. All studies had been funded by academic organisations [14–23]. Six studies were related to pharmacological treatments in Iran [14–19] (see Table 1); one study was related to a combination of psychiatric medications for anxiety and depression with BCBT in Thailand [23] and three studies were related to BCBT in Australia [20–22] (see Table 2). The included BCBT studies and a BCBT + pharmacological study had a median follow-up period of six months (range: 2 months to 12 months) [20–23] while this issue was different in pharmacological studies [14–19].

Pharmacological studies in Iran

Risperidone1 vs. aripiprazole2

Farnia et al. (2014) reported the effectiveness of risperidone versus aripiprazole in treatment of amphetamine-induced psychotic symptoms. In a six-week double-blind RCT, 45 subjects received either 15 mg of aripiprazole or four mg of risperidone on a daily basis. Positive and negative symptoms of psychosis were assessed at baseline and following the end of the trial. Self-reported positive and negative symptoms were reduced significantly in the two groups (p < 0.001) following the end of treatment. Both aripiprazole and risperidone were found effective in reducing amphetamine-induced psychotic symptoms over the same time. However, risperidone had better treatment impacts on positive psychotic symptoms while subjects with negative symptoms were better treated with aripiprazole [14].

Methylphenidate3

Rezaei et al. (2015) reported the effectiveness of methylphenidate in treating methamphetamine (MA) dependence. Fifty-six subjects participated in a double-blind RCT. Participants received either 18–54 mg of methylphenidate (n = 28) or placebo (n = 28) a day in ten weeks. Overall, 18 mg of methylphenidate was given to subjects a day in the first week; 36 mg of the same medication was given to subjects a day during the second week and then subjects received 54 mg of methylphenidate a day for the remaining eight weeks. Group two received placebo in ten weeks. Of 56 subjects, ten subjects left the treatment group and 12 subjects left the placebo group before weeks six and 34. Urine specimens were collected for MA detection on a weekly basis. At the end of the trial, the treated subjects provided less MA positive urine specimens compared with the placebo subjects (p = 0.03). By the end of the trial, the treated subjects were more likely than the placebo subjects (p = 0.03) to report reduced MA craving and depression (p = 0.02) [15].

Topiramate4 vs. placebo

Rezaei et al. (2016) reported the effectiveness of topiramate on MA dependence. In a double-blind RCT, sixty two MA subjects received either topiramate or placebo in ten weeks. The treatment was initiated with 50 mg of topiramate a day and continued with prescribing 200 mg of topiramate a day. The severity of dependence on MA and MA craving were assessed by two questionnaires on a weekly basis. Urine specimens were collected at baseline and every two weeks during the treatment. Fifty-seven patients completed the treatment. At week six, the treatment group was less likely to have MA-positive urine specimens compared with the placebo group (p = 0.01). The severity of dependence on MA (p < 0.001) and MA craving (p < 0.001) were lower in the topiramate group than in the placebo group over the same time [16].

Haloperidol5 vs. risperidone6

Samiei et al. (2016) reported the effects of haloperidol and risperidone in treating positive symptoms of psychosis in MA patients. Forty four patients with MA-associated psychosis participated in the study. Twenty two subjects received 5–20 mg of haloperidol and twenty two subjects received 2–8 mg of risperidone. Each subject was assessed at baseline, during three weeks of treatment and one week following the end of the treatment. Haloperidol (p < 0.05) and risperidone (p < 0.05) were effective in the treatment of self-reported MA-associated psychosis. The effectiveness of risperidone and haloperidol increased in the first two weeks of treatment and was stable in the second two weeks of treatment [17].

Methadone7 vs. buprenorphine8

Ahmadi et al. (2017) reported the effectiveness of methadone and buprenorphine in treating self-reported MA craving during a seventeen-day treatment procedure. In a double-blind RCT, 40 MA subjects received either 40 mg of methadone (n = 20) or eight mg of buprenorphine (n = 20) a day. Urine specimens were collected for MA detection two times on a weekly basis. Buprenorphine group was significantly more likely than the methadone group (p < 0.05) to self-report reduced MA craving following the end of the treatment [18].

Riluzole9 vs. placebo

Farahzadi et al. (2019) reported that a group of MA subjects received either 50 mg of riluzole (n = 34) or placebo (n = 54) two times a day in 12 weeks of treatment. The riluzole group was more likely than the placebo group to attend weekly treatment visits (riluzole group, median (range) = 13.00 vs. placebo group = 4.00, p = 0.07). The riluzole group was more likely than the placebo group to provide weekly positive MA urine specimens (riluzole group = 5.00% vs. placebo group = 45.00%, p = 0.004). Subjects in the riluzole group self-reported greater reductions in MA craving, withdrawal, and depression compared with the placebo group [19].

Abstinence from amphetamines in BCBT studies

Abstinence from amphetamine was confirmed in all BCBT studies [20–23]. In one Australian study, urine samples were randomly collected from 17.4% of subjects (19 of 109) at six-month follow-up [21]. At six-month follow-up, self-reported abstinence from amphetamine ranged from 40.8% [21] to 58.3% [20] for treated subjects (p < 0.01) and from 17.6% [21] to 21.4% [20] for the control subjects (p < 0.01). The highest rate of abstinence from amphetamine was self-reported by those subjects who completed 3–4 treatment sessions (85.7%, p < 0.01) [20]. Baker et al. (2005) reported that subjects allocated to either two or four treatment sessions were more likely to self-report abstinence from amphetamine at six-month follow-up (abstinence rates: in the control group: 17.6%; in the two BCBT sessions: 33.8%, p < 0.01; and in the four BCBT sessions: 37.9%, p < 0.01) [21]. In one trial, among treatment completers, abstinence from amphetamine was confirmed by self-report at 15-week post-treatment (treatment group: 54.5% vs. control group: 44.4%), at six-month (treatment group: 45.5% vs. control group: 44.4%) and at 12-month (treatment group: 55.6% vs. control group: 87.5%) follow-ups with no significant between-group differences [22].

Abstinence from amphetamines in a pharmacological + BCBT study

In one Thai study, subjects received psychiatric medications for depression and anxiety as well as BCBT. Urine specimens were collected from all subjects (n = 200) at six-month follow-up [23]. Treated subjects were more likely than the control group to provide negative urine specimens for amphetamine (treatment group: 44.5% vs. control group: 13.2%, p < 0.01) at two-month follow-up [23].

Reduced daily amphetamine use in BCBT studies

A significant reduction in daily amphetamine use was confirmed in all studies [20–23]. Treatment efficacy was found higher in the treatment group (d = 0.93) than in the control group (d = 0.40) at six-month follow-up (p < 0.01) [20]. Those subjects who completed two treatment sessions showed the most reduction in self-reported daily amphetamine use (d = 1.53) compared with the control group over the same time (p < 0.01) [20]. Those subjects who completed 3–4 treatment sessions (d = 0.75) were more likely than the control group (d = 0.54) to self-report a significant reduction in daily amphetamine use (p < 0.01) at six-month follow-up [21]. The treatment group (d = 1.28) was more likely than the control group (d = 0.33) to self-report reduced daily amphetamine use on the Opiate Treatment Index (OTI) between baseline and 12-month follow-up (p < 0.01) [22].

Reduced daily amphetamine use in a pharmacological + BCBT study

The amount of self-reported daily amphetamine use on Timeline Followback (TLFB) was reduced from baseline (both groups: 1–10) to six-month follow-up (both groups: 0–2) with no reported significant between-group differences. Furthermore, the number of days of self-reported amphetamine use was reduced from baseline (treatment: 2–14, control: 1–14) to six-month follow-up (both groups: 0–5) with no reported significant between-group differences [23].

Secondary outcomes

Daily polydrug use in BCBT studies

Baker et al. (2001) indicated that treated subjects (d = 0.46) was more likely than the control subjects (d = 0.56) to self-report a significant reduction in daily polydrug use on the OTI (p < 0.01) at six-month follow-up. Over the same time, subjects who completed one treatment session (d = 1.01) showed the largest significant treatment effect compared with other subjects in the study (p < 0.01) [20]. Baker et al. (2005) indicated that those subjects who completed 3–4 treatment sessions (d = 0.71) were more likely than the control group (d = 0.43) to self-report a significant reduction in daily polydrug use on the OTI at six-month follow-up (p < 0.01) [21]. Baker et al. (2001) indicated that there were moderate treatment effects in reducing self-reported daily cannabis use in the treatment group (d = 0. 36) and the control group (d = 0.42) on the OTI at six-month follow-up [20]. However, there were no reported substantial between-group differences [20]. Baker et al. (2001) indicated that there were moderate treatment effects in reducing self-reported daily tobacco use in the treatment group (d = 0.14) and in the control group (d = 0.28) on the OTI at six-month follow-up [20]. However, there were no reported substantial between-group differences [20]. As indicated by Baker et al. (2006) in Australia, the control group (d = 0.97) was more likely than the treatment group (d = 0.54) to self-report a significant reduction in alcohol consumption on the OTI between baseline and 12-month follow-up [22]. However, the reasons why the control condition was more effective than BCBT in reducing alcohol consumption were not reported.

Motivation to change in a pharmacological + BCBT study

Suvanchot et al. (2012) indicated that the treatment group was more likely than the control group to self-report motivation to change (d = 0.84) on Motivation for Change Ladder and self-efficacy (d = 1.09) on Self-Efficacy Ruler to manage daily amphetamine use at six-month follow-up (p < 0.01) [23].

Mental health in BCBT studies

Baker et al. (2001) indicated that those subjects who completed two treatment sessions were more likely than the control group to self-report improved mental health (p < 0.01) on General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) at six-month follow-up [20]. However, no effect size was reported [20]. In the same study, the treatment group (d = 0.78) was more likely than the control group (d = 0.28) to self-report a significant reduction in depression on the GHQ-28 between baseline and six-month follow-up (p < 0.01) [20].

Other treatment outcomes in BCBT studies

Baker et al. (2001) indicated that subjects self-reported overall reductions (p < 0.01) in drug injection and criminality on the OTI as well as, improved general functioning on the GHQ-28 and stage of change on the Contemplation Ladder (CL) (p < 0.01) at six-month follow-up [20]. However, no significant between-group differences were reported [20]. As indicated by Baker et al. (2005), subjects self-reported overall reductions (p < 0.001) in severity of amphetamine dependence on the Severity of Dependence Scale, criminality and drug injection on the OTI at six-month follow-up as well as improved general functioning on the OTI, stage of change on the CL and psychological well-being on the GHQ-28 (p < 0.001) over the same time [21]. However, significant between-group differences were not reported [21].

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The present review documents that pharmacological treatments effectively helped Iranian patients alleviate some amphetamines-related symptoms. However, the effects of medications were different on amphetamines-related symptoms. While aripiprazole, risperidone and haloperidol reduced MA psychosis. [14, 17], methylphenidate reduced MA craving and depression [15]. In addition, some medications were effective in reducing craving including topiramate [16], buprenorphine and methadone [18]. While Topiramate reduced the severity of dependence on MA [16], riluzole reduced MA craving, withdrawal, and depression [19]. This is consistent with other studies which indicate that pharmacological treatments can reduce amphetamines-related symptoms among patients [24, 25].

The review also indicated that BCBT alone or in combination with pharmacological treatments was efficacious in either abstinence from amphetamines or reduced amphetamines abuse with medium or large effect sizes [20–23]. The percentage of abstinence from amphetamines had a range from 40.8% [21] to 58.3% [20] among treated participants at six-month follow-up. A review indicated that the long-term efficacy of behavioral interventions is high in terms of treating substance abuse [26].

The effects of BCBT alone or in combination with pharmacological treatments were sustained between two and 12 months [20–23]. Furthermore, high rates of treatment retention were reported at six-month and 12-month follow-ups [20–23]. These findings demonstrate the efficacy of the two treatments as well as patient engagement in the treatment. Studies indicate a strong relationship between participant retention at follow-up and the efficacy of pharmacological treatments in combination with behavioral interventions for MA patients [24, 25]. The review findings indicated that pharmacological treatments alone led to significant reductions in craving, withdrawal, psychosis and depression among amphetamine abusers [14–19]. The review results can be important for clinical practice. If some medicines can reduce amphetamines-related symptoms, they can be used in drug treatment services. Furthermore, using BCBT is likely to increase the outcome of pharmacological treatments for amphetamines abuse in clinical practice. These issues need to be considered by clinicians and psychologists who work with amphetamine abusers.

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for improving patientsʼ health conditions [26]. Due to limited number of studies, there is still a need for further studies of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments in combination with BCBT for amphetamines abuse. In terms of BCBT, some studies reported that patients experienced significant reductions in the severity of amphetamine dependence, substance dependence and improved social functioning [20–23]. Furthermore, overall reduced criminality [20, 21], improved motivation to change and self-efficacy [21, 23] as well as improved physical and mental health [20, 21] were found among both the treatment and control groups in some studies. The review also indicated that the likelihood of improvements in the social and health conditions was higher when participants completed 3–4 sessions of treatment compared with the control condition. These findings shed a new light on the assumption that the effects of BCBT on patients can go beyond treating amphetamines abuse and treat their social and health problems. However, it is not well-documented yet if BCBT is superior to pharmacological treatments for amphetamine abuse or a combination of the two treatments can work better.

Strength and limitations of this study

This systematic review revealed that participant engagement in treatment was high, abstinence from amphetamines was substantial and improvements in the social and health conditions of the participants were considerable. Furthermore, no harm was reported by patients who received pharmacological treatments or BCBT alone or combined. However, assessments of amphetamines abuse were largely based on self-report. Nevertheless, studies have indicated that the self-report of drug-related problems is reliable, as long as participation is voluntary and results remain confidential [27]. There were few relevant studies of pharmacological treatments in combination with BCBT. Due to the limited number of studies, conducting a meta-analysis was not feasible. Furthermore, combining the outcomes from the individual trials through meta-analysis and using a random-effects model were not feasible because a certain degree of heterogeneity was expected among trials. Furthermore, data were inadequate to measure effect sizes for some outcome measures. No studies were located that analysed treatment outcomes by gender, although the importance of gender differences and treatment outcomes have been reported in the research literature [28, 29].

Conclusion

This review leads to the conclusion that pharmacological treatments alone or in combination with BCBT outperform control conditions in the treatment of amphetamines and associated harms. However, it is not clear which type of pharmacological treatment is superior in the treatment of amphetamines. Large-scale RCTs need to determine if pharmacological treatments alone or in combination with BCBT are effective in treating a representative number of amphetamine abusers in long-term. Furthermore, large-scale RCTs need to be conducted on how to implement pharmacological treatments alone or in combination with BCBT to determine if they can be largely incorporated into clinical practice and be effective for the benefit of Iranian patients following the end of treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tehran University of Medical Sciences for approving the study.

Authors` contributions

Mansour Khoramizadeh designed the study and conributed to approving the study. Mohammad Effatpanah, Alireza Mostaghimi, Mehdi Rezaei and Alireza Mahjoub contributed to searching and conducting the systematic review. Sara Shishehgar contributed to writing and editing the paper.

Appendix

The following search terms were used for Medline and adapted for all of the other databases: ʻ amphetamine, amphetamine-type stimulant disorders, amphetamines, amphetamine-type stimulants, amphetamine-related disorders, dependence, addiction, clinical trial, randomised clinical trial, controlled trial, pharmacological treatment, craving, withdrawal, brief cognitive-behavioural therapy, brief cognitive-behavioural intervention, brief intervention, brief cognitive-behaviour treatment, brief cognitive-behaviour therapy, brief psychosocial treatment, cognitive therapy, coping skills, dioxymethamphetamine, ecstasy, ephedrine, intervention, methamphetamine, methamphetamine use disorder, MDMA, methylphenidate, psychotherapy, psychological treatment, psychoactive drugs, psychostimulants, psychostimulant drugs, relapse prevention, randomised controlled trial, randomised clinical trial, regular stimulant use, stimulant use, stimulant abuse, stimulant dependence, stimulant, stimulants ʼ.

Funding

The present review was part of a larger studies which was funded (Ethics code number: 31427) by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Ethical approval

The present review was part of a larger studies which was approved (Ethics code number: 31427) by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Informed consent

Informed consent is not applicable due to this issue that the paper is a systematic review.

Research data policy

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Footnotes

Risperdal

Abilify

Ritalin

Topamax

Haldol

Risperdal

Dolophine

Subutex

Rilutek

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sullivan D, McDonough M. Methamphetamine: where will the stampede take us? J Law Med. 2015;23(1):41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radfar SR, Rawson R. Current research on methamphetamine: epidemiology, medical and psychiatric effects, treatment, and harm reduction efforts. Addict health. 2014;6(3–4):146–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrpour M. Methamphetamine abuse a new health concern in Iran. Daru. 2012;20(1):73. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawson RA, McCann MJ, Flammino F, Shoptaw S, Miotto K, Reiber C, et al. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioural approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction. 2006;101(2):267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll KM. Lost in translation? Moving contingency management and cognitive behavioral therapy into clinical practice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1327:94–111. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minozzi S, Saulle R, De Crescenzo F, Amato L. Psychosocial interventions for psychostimulant misuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(9):CD011866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Hill R. Evidence-based practices for treatment of methamphetamine dependency: a review. Guelph, ON: Community Engaged Scholarship Institute; 2015.

- 8.Vocci FJ, Montoya ID. Psychological treatments for stimulant misuse, comparing and contrasting those for amphetamine dependence and those for cocaine dependence. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(3):263–268. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832a3b44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker A, Kay-Lambkin F, Lee NK, Claire M, Jenner L. Brief cognitive behavioural intervention for regular amphetamine users. Canberra: Australian government. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bond Frank W., Dryden Windy., editors. Handbook of Brief Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farnia V, Shakeri J, Tatari F, Juibari TA, Yazdchi K, Bajoghli H, Brand S, Abdoli N, Aghaei A. Randomized controlled trial of aripiprazole versus risperidone for the treatment of amphetamine-induced psychosis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(1):10–15. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.861843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rezaei F, Emami M, Zahed S, Morabbi MJ, Farahzadi M, Akhondzadeh S. Sustained-release methylphenidate in methamphetamine dependence treatment: a double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. Daru. 2015;23:2. doi: 10.1186/s40199-015-0092-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezaei F, Ghaderi E, Mardani R, Hamidi S, Hassanzadeh K. Topiramate for the management of methamphetamine dependence: a pilot randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2016;30(3):282–289. doi: 10.1111/fcp.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samiei M, Vahidi M, Rezaee O, Yaraghchi A, Daneshmand R. Methamphetamine-associated psychosis and treatment with haloperidol and risperidone: a pilot study. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2016;10(3):e7988. doi: 10.17795/ijpbs-7988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi J, Razeghian Jahromi L. Comparing the effect of buprenorphine and methadone in the reduction of methamphetamine craving: a randomized clinical trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):259. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2007-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farahzadi MH, Moazen-Zadeh E, Razaghi E, Zarrindast MR, Bidaki R, Akhondzadeh S. Riluzole for treatment of men with methamphetamine dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(3):305–315. doi: 10.1177/0269881118817166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker A, Boggs TG, Lewin TJ. Randomised controlled trial of brief cognitive-behavioural interventions among regular users of amphetamine. Addiction. 2001;96(9):1279–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96912797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker A, Lee NK, Claire M, Lewin TJ, Grant T, Pohlman S, Saunders JB, Kay-Lambkin F, Constable P, Jenner L, Carr VJ. Brief cognitive behavioural interventions for regular amphetamine users: a step in the right direction. Addiction. 2005;100(3):367–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker A, Bucci S, Lewin TJ, Kay-Lambkin F, Constable PM, Carr VJ. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for substance use disorders in people with psychotic disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:439–448. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suvanchot KS, Somrongthong R, Phukhao D. Efficacy of group motivational interviewing plus brief cognitive behavior therapy for relapse in amphetamine users with co-occurring psychological problems at southern psychiatric Hospital in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2012;95(8):1075–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alammehrjerdi Z, Barr AM, Noroozi A. Methamphetamine-associated psychosis: a new health challenge in Iran. Daru. 2013;21:30. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cretzmeyer M, Sarrazin MV, Huber DL, Block RI, Hall JA. Treatment of methamphetamine abuse: research findings and clinical directions. J Subst Abus Treat. 2003;24(3):267–277. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magill M, Ray LA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(4):516–527. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Najafi F, Pasdar Y, Shakiba E, Hamzeh B, Darbandi M, Moradinazar M, Navabi J, Anvari B, Saidi MR, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Validity of self-reported hypertension and factors related to discordance between self-reported and objective measured hypertension: evidence from a cohort study in Iran. J Prev Med Public Health. 2019;52(2):131–139. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.18.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hser YI, Evans E, Huang YC. Treatment outcomes among women and men methamphetamine abusers in California. J Subst Abus Treat. 2005;28(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Y, Lin V, Wu F, Hser Y-I. Gender comparisons among Asian American and Pacific islander patients in drug dependency treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(6):752–762. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2016.1155604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]