Abstract

Background

Demographic and socio-economic factors determine pharmaceutical health care utilization for individuals. Prescription and non-prescription medicine use are expected to have different determinants. Even though prescription and non-prescription medicine use is being well researched for developed countries, there are only a few studies for developing countries.

Objectives

This paper aims to analyze the socio-economic and individual characteristics that determine the use of prescription and non-prescription medicine. We examine the issue for the specific case of Turkey since Turkey’s health system has undertaken significant changes in the last two decades and especially after 2003 with the “Health Transformation Programme”.

Methods

Data from the nationally representative “Health Survey” are used in the analysis. The data set covers the 2008–2016 period with two-year intervals. Pooled multivariate logistic regression is employed to identify the underlying determinants of prescription and non-prescription medicine use.

Results

When compared to 2008, non-prescription medicine use decreases until 2012, however, an increasing trend appears after 2012. For prescription medicine use, a decreasing trend emerges after 2012. Findings from the marginal effects indicate that for non-prescription medicine use, the highest effect stems from the health status. For prescription medicine use, the highest marginal effects arise from age, health and employment status indicating the importance of the need and predisposing factors.

Conclusion

Decreasing non-prescription medicine use largely depends on easier access to health care service utilization. Although having a health insurance has a positive relationship with prescription medicine use, there is still a problem for individuals living a rural area and heaving a lower income level since they are more likely to use non-prescription medicine.

Keywords: Prescription medicine, Non-prescription medicine, Self-medication, Socio-economic determinants, Turkey

Introduction

Socio-economic status is an important determinant of health care utilization [1, 2], which is well known and researched. Demographic and socio-economic factors also determine the pharmaceutical health care utilization for individuals. In this regard, evidence indicates that prescribed and non-prescribed medicine use have different socio-economic and demographic determinants [3–6]. Both prescribed and non-prescribed medicine use is a growing concern since per capita pharmaceutical spending has an increasing trend worldwide and is responsible for more than 15% of health care spending [7]. Data indicates that both prescribed and non-prescribed medicine sales are presenting an increasing trend in Turkey. There is an estimated 20.2% increase in pharmaceutical market growth for 2017, while 9.7% of this increase is originating from price increases, 2,3% is originating from increase in volume [8]. When concerns regarding health expenditures and public health are combined, the increase in medicine use becomes an important matter for Turkey.

Even though OECD countries historically have better access to the pharmaceutical market compared to Turkey [9], it is possible to observe a converging pattern in terms of medicine use especially after 2003. This converging pattern is more evident in several drug groups such as antibiotics [10]. Supply side effects on the pharmaceutical market such as increased access may explain this increasing trend in medicine use in Turkey. Furthermore, demand side effects such as higher life expectancies, increased income or education may also explain this trend.

Turkey’s health system has undertaken significant changes in the last 15 years, both on the supply and demand side parameters. Although the general shift in the health outputs, variables and coverage relating to the Health Transformation Programme (HTP) or implemented health reforms in Turkey have been well researched [11, 12], whereas the specific effects of these changes on the pharmaceutical market have been largely overlooked. This study aims to fill this gap in the existing literature. For this aim, this study investigates the main determinants of physician prescribed medicine use (PPMU) and non-prescribed medicine use (NPMU) and how they change over time.

The Turkish government has introduced the HTP in 2003 with a specific aim of universal health coverage. HTP is designed to change the whole system with a focus on equality and increased health coverage and access to health care services. These reforms have increased the ratio of insured individuals in the population from 66.3% in 2003 to almost 95% in 2016. Such increase has resulted in easier access to health and pharmaceutical services [13]. The General Health Insurance (GHI) scheme, which unifies three different health insurance schemes under one umbrella, provides reimbursement for a wide range of services including pharmaceuticals. The GHI reimburses 90% of selected pharmaceuticals for currently employed individuals and 80% for unemployed outpatients. Moreover, for inpatients, the reimbursement ratio is 100% [14]. In Turkey, the Ministry of Health is the authority on deciding whether the pharmaceuticals should be sold with or without a prescription and their prices. However, the reimbursement list for pharmaceuticals are decided by the Social Security Institution [15]. The current lack of legal regulation in terms of NPMU in Turkey combined with increased access to all health care services with recent health reforms are expected to increase NPMU. Recently, as a method of cost control and increased concerns on over-use of antibiotics, certain reforms in the post-2013 period have been undertaken. The Ministry of Health has started these programs and is increasingly training the pharmacists and physicians on the dangers, and costs of over-use of pharmaceutical products [16]. Currently, antibiotics, some forms of antidepressants and painkillers are considered prescription only drugs and, thus, cannot be sold without prescription [17].

In this context, this study aims to investigate the different underlying patterns in prescribed and non-prescribed medicine use. The existing literature indicates that gender, education, socio-economic status, age, self-reported health status and health awareness are among the important factors affecting medicine use (see, for example, [18–25]). However, the results from the existing literature is not comparable with Turkey due to the lack of studies focusing on medicine use. This current study has two main contributions to the existing literature. First, the prevalence of pharmaceutical use patterns over time in Turkey is presented. Second, this study differentiates among the determinants of PPMU and NPMU. For this aim, we use the aforementioned correlates in conjunction with Andersen’s utilization model [26, 27], which differentiates between three main factor groups: (1) health needs, (2) enabling factors, and (3) predisposing factors.

Methods

Data used in this study is derived from the nationally representative “Health Survey” conducted by the Turkish Statistical Institute. Health Surveys are conducted every two years since 2008, to understand the health profile of the general Turkish population. All available surveys are used in this study, covering a period of 2008–2016. The surveys cover all settlements in the territory of the Republic of Turkey and all individuals who have received health service within the past 12 months of the survey date. Settlements with a population lower than 20,000 are defined as rural and above 20,001 as urban in each survey and strata, and two-phase cluster sampling methodologies are used. The rural-urban difference is utilized as external stratification. Health Surveys are conducted in 6140 households in 2008; 6551 in 2010; 12,153 in 2012; 9740 in 2014 and 9470 in 2016. The response rates are reported as 77.6% in 2008; 83% in 2010; 84.4% in 2012; 85% in 2014 and 85.6% in 2016. Individuals who are older than 15 years of age are included in the analysis yielding 14,664 observations for 2008, 14,447 for 2010, 28,055 for 2012, 19,129 for 2014 and 17,242 for 2016. The data sets contain information on the socio-economic status of individuals as well as information on their health status and health behaviors.

Two questions from these surveys are utilized to construct the dependent variable:

Have you taken any medicine prescribed by a doctor within the past two weeks?

Have you taken any medicine, which was not prescribed by a doctor within the past two weeks?

Pooled multivariate logit estimation methodology is used to analyze the differences among the determinants of PPMU and NPMU. For this purpose, the use of PPMU and NPMU are separately regressed against the independent variables that are described in Table 1. In this study, consistent with the Andersen’s behavioral model [26], we employ age, gender, education and the employment status of individuals as predisposing factors whereas we use the residence, insurance status, household income to represent enabling factors. Finally, the self-assessed health status, health problem and chronic diseases are used as the need factors separately as a robustness check for the findings. These variables are widely used in the existing literature to determine the underlying patterns of medicine use [19, 28]. All variables are used as categorical variables, and the analysis is performed using STATA, version 14.

Table 1.

Variable names and descriptions

| Age | The age of the individual is asked and the reported within age groups | 15–24 (base category) |

| 25–34 | ||

| 35–44 | ||

| 45–54 | ||

| 55–64 | ||

| 65–74 | ||

| 75+ | ||

| Gender | Gender of the respondent | Male (base category) |

| Female | ||

| Residence | Information regarding the residence of the individual. Only available for 2008, 2010 and 2012. | Urban |

| Rural (base category) | ||

| Insurance Status | Whether the respondent has any health insurance (public or private) or not. | Not Insured (base category) |

| Insured | ||

| Education | The highest educational attainment of the respondent | Illiterate |

| Literate | ||

| Primary (base category) | ||

| Middle | ||

| Secondary | ||

| University | ||

| Higher | ||

| Employment Status | Information on the employment status of the individual | Unemployed (base category) |

| Employed | ||

| Household Income | Information regarding household income. | $196 or lessa (base category) |

| $197–$281 | ||

| $282–$394 | ||

| $395–$578 | ||

| $579 or more | ||

| Health status (SAH) | Information regarding individuals self-assessed health. | Poor (base category) |

| Fair | ||

| Good | ||

| Very good | ||

| Excellent | ||

| Health problem | Information regarding any health problem in the last six months. | No (base category) |

| Yes | ||

| Chronic disease | Information regarding any diagnosed chronic illness lasting more than 6 months. | No (base category) |

| Yes |

aTurkish Liras converted to USD at the current rate of 5.5TL

Results

Table 2 indicates the number and percentage of medicine use of individuals for all years covered in the study. This table presents information on individuals answered “NO” to both of the above questions, hence, not using any medication. Further, the table provides information on individuals who answered “YES” to both questions, therefore, using both PPM and NPM and, finally, on individuals who responded “YES” to either one of the questions.

Table 2.

Medicine use over time

| 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Not using any medication | 8540 | 58.49 | 8134 | 56.45 | 16,727 | 64.62 | 7921 | 44.93 | 7168 | 45.66 |

| Only PPMUa | 3858 | 26.42 | 4088 | 28.37 | 6262 | 24.19 | 4316 | 24.48 | 3670 | 23.38 |

| Only NPMUb | 1752 | 12.00 | 1677 | 11.64 | 2248 | 8.68 | 3581 | 20.31 | 3064 | 19.52 |

| Both PPMU and NPMU | 452 | 3.10 | 510 | 3.54 | 648 | 2.50 | 1813 | 10.28 | 1795 | 11.44 |

| Using any medication (PPMU and/or NPMU) | 6062 | 41.51 | 6275 | 43.55 | 9158 | 35.38 | 9710 | 55.07 | 8529 | 54.34 |

| Total number of observations | 14,602 | 14,409 | 25,885 | 17,631 | 15,697 | |||||

aPPMU stands for physician prescribed medicine use

bNPMU stands for non-prescribed medicine use

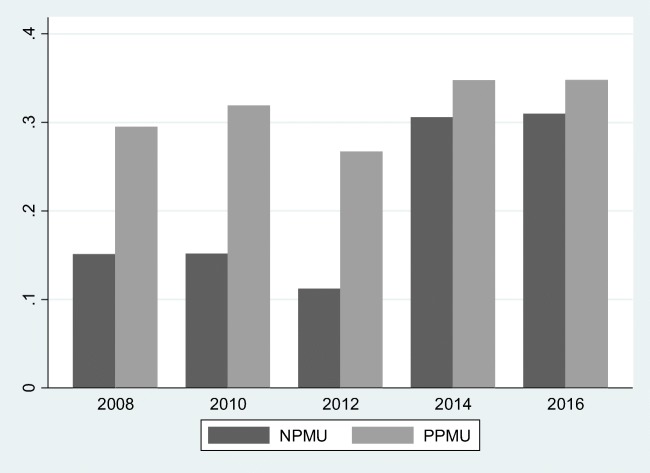

According to Table 2, medicine use (PPMU and/or NPMU) is at its lowest in 2012. However, we observe a severe spike and an increasing trend in medicine use after 2012. Furthermore, it is possible to argue that this growing trend in medicine use is originated from NPMU as represented in Fig. 1. Table 2 and Fig. 1 indicate that medication use is an important issue in Turkey and, therefore, needs further analyzing and this analysis should be differentiated by the PPMU and NPMU partition.

Fig. 1.

NPMU and PPMU over time

In order to ensure multicollinearity is not an issue for the pooled multivariate analysis data is checked using the correlation matrix and the variance inflation factors. Table 3 presents the multicollinearity check results, indicating that there is no multicollinearity between any of the independent variables.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix and VIF results

| Age | Gender | Residence | Insurance Status | Education | Employment Status | Household Income | Health Status (SAH) | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.0000 | 1.35 | |||||||

| Gender | −0.0054 | 1.0000 | 1.19 | ||||||

| Residence | 0.1062 | 0.0125 | 1.0000 | 1.14 | |||||

| Insurance status | 0.1132 | 0.0424 | −0.0612 | 1.0000 | 1.05 | ||||

| Education | −0.3077 | −0.1826 | −0.2685 | 0.0497 | 1.0000 | 1.61 | |||

| Employment Status | −0.0288 | −0.3586 | −0.0045 | 0.0387 | 0.2570 | 1.0000 | 1.21 | ||

| Household Income | −0.0681 | −0.0451 | −0.3069 | 0.1444 | 0.4053 | 0.1824 | 1.0000 | 1.42 | |

| Health Status (SAH) | −0.4159 | −0.1472 | −0.1026 | −0.0151 | 0.3302 | 0.1578 | 0.2078 | 1.0000 | 1.31 |

Table 4 presents the results for the pooled multivariate logit estimation for NPMU and PPMU.

Table 4.

Pooled logit results for NPMU and PPMU

| NPMU | NPMU | PPMU | PPMU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Coefficients | Marginal Effects | Coefficients | Marginal Effects | |

| Age | 25–34 | 0.0524 | 0.006 | 0.272*** | 0.044*** |

| (0.051) | (0.005) | (0.048) | (0.008) | ||

| 35–44 | 0.228*** | .027*** | 0.496*** | 0.083*** | |

| (0.053) | (0.006) | (0.049) | (0.008) | ||

| 45–54 | 0.210*** | 0.025*** | 0.660*** | 0.112*** | |

| (0.054) | (0.006) | (0.049) | (0.009) | ||

| 55–64 | −0.009 | −0.001 | 1.00*** | 0.179*** | |

| (0.058) | (0.006) | (0.050) | (0.009) | ||

| 65–74 | −0.427*** | −0.044*** | 1.390*** | 0.266*** | |

| (0.064) | (0.005) | (0.052) | (0.011) | ||

| 75+ | −0.896*** | −0.078*** | 1.671*** | 0.333*** | |

| (0.097) | (0.005) | (0.060) | (0.012) | ||

| Gender | Female | 0.087*** | 0.010*** | 0.340*** | 0.054*** |

| (0.022) | (0.002) | (0.019) | (0.003) | ||

| Residence | Urban | −0.184*** | −0.021*** | 0.073*** | 0.011*** |

| (0.032) | (0.003) | (0.024) | (0.003) | ||

| Insurance Status | Insured | −0.375*** | −0.048*** | 0.570*** | 0.082*** |

| (0.033) | (0.003) | (0.037) | (0.05) | ||

| Education | Illiterate | −0.028 | −0.003 | −0.136*** | −0.021*** |

| (0.044) | (0.004) | (0.031) | (0.004) | ||

| Literate | −0.094 | −0.010 | −0.097** | −0.015** | |

| (0.064) | (0.006) | (0.043) | (0.006) | ||

| Middle school | −0.074** | −0.008** | −0.031 | −0.004 | |

| (0.032) | (0.003) | (0.028) | (0.004) | ||

| Secondary school | 0.039 | 0.004 | −0.014 | −0.002 | |

| (0.030) | (0.003) | (0.026) | (0.004) | ||

| University |

−0.008 (0.036) |

−0.0009 (0.004) |

0.060 (0.032) |

0.009 (0.005) |

|

| Higher | 0.096 | 0.011 | 0.110 | 0.018 | |

| (0.092) | (0.011) | (0.090) | (0.014) | ||

| Employment Status | Employed | 0.349*** | 0.042*** | −0.197*** | −0.31*** |

| (0.025) | (0.003) | (0.022) | (0.003) | ||

| Household Income | $197–281 | −0.030 | −0.003 | 0.128*** | 0.021*** |

| (0.032) | (0.003) | (0.285) | (0.004) | ||

| $282–394 | −0.014 | −0.001 | 0.203*** | 0.034*** | |

| (0.033) | (0.003) | (0.0286) | (0.004) | ||

| $395–578 | 0.003 | 0.0003 | 0.220*** | 0.037*** | |

| (0.034) | (0.003) | (0.029) | (0.005) | ||

| $579+ | −0.015 | −0.001 | 0.228*** | 0.038*** | |

| (0.037) | (0.004) | (0.032) | (0.005) | ||

| Health Status (SAH) | Fair | 0.427*** | 0.057** | −0.051 | −0.008 |

| (0.155) | (0.022) | (0.074) | (0.011) | ||

| Good | 0.824*** | 0.123*** | −0.536*** | −0.076*** | |

| (0.150) | (0.026) | (0.071) | (0.008) | ||

| Very good | 0.772*** | 0.114*** | −1.340*** | −0.157*** | |

| (0.150) | (0.025) | (0.072) | (0.005) | ||

| Excellent | 0.691*** | 0.099*** | −1.908*** | −0.192*** | |

| (0.152) | (0.025) | (0.080) | (0.003) | ||

| Year Dummies | 2010 | −0.150*** | −0.017*** | 0.087*** | 0.014*** |

| (0.038) | (0.003) | (0.029) | (0.004) | ||

| 2012 | −0.463*** | −0.050*** | −0.248*** | −0.039*** | |

| (0.038) | (0.003) | (0.028) | (0.004) | ||

| 2014 | 0.394*** | 0.049*** | −0.254*** | −0.0397*** | |

| (0.042) | (0.005) | (0.035) | (0.005) | ||

| 2016 | 0.380*** | 0.047*** | −0.372*** | −0.056*** | |

| (0.043) | (0.005) | (0.036) | (0.004) |

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p < 0.01 ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

The results of the study indicate that individuals between 35 and 44 and 45–54 age range, females, individuals living in rural areas, individuals who have no health insurance, individuals with better health status1 and employed individuals have a higher probability of NPMU. Illiterate and literate individuals have a lower probability of using PPMU when compared to primary school graduates. However, increase in years of education has no statistically significant effect on NPMU. Household income is found to have no statistically significant effect on NPMU, while the probability of PPMU increases with household income.

Finally, examination of the year dummies indicate that NPMU presents a declining trend for 2010 and 2012, however, presents an increasing trend for 2014 and 2016 as evident from Fig. 1. On the other hand, for PPMU, a decreasing trend emerges after 2012.

Discussion

This study aims to investigate the factors behind PPMU and NPMU in Turkey by using nationally representative Health Surveys of Turkey from 2008 to 2016. Based on National Health Surveys for different countries, researchers have widely started to examine patterns of medical drug use in the general population (see, for example, [19, 25, 29, 30]). However, to our knowledge, no previous study aims to investigate the prevalence and determinants of the self-reported general use of medicine in Turkey by distinguishing between PPMU and NPMU.

Before the HTP implemented in 2003, there were five different public schemes in Turkey, and these schemes differ concerning their benefits packages and, thus, there were huge disparities in access to health care. However, after 2003, all public plans were unified and, the scope of financial protection to the population was enlarged, resulting better access to health care services. The increase in access to health care services can be considered to have an important role in terms of decreasing self-medication and increasing PPMU. The results of the current study are as expected when considering the effects of the HTP and GHI since there is a positive relationship between having health insurance and PPMU and a negative relationship between having health insurance and NPMU. The results also indicate that individuals living in urban areas are more likely to use prescribed medicine and are less likely to use non-prescribed medicine. This can be explained by the fact that there may be a problem regarding access to health care services in rural areas of Turkey, which is an important proxy for the functioning of the health system. Therefore, it can be argued that access to health care services is still a problem for Turkey in rural areas. In this context, an important policy recommendation to decrease NPMU is to provide easier access to health care facilities primarily in the disadvantaged areas of Turkey.

In addition, the findings demonstrate that household income has no statistically significant effect on NPMU, whereas there is a positive relationship between household income and PPMU. The positive relationship between PPMU and household income is consistent with the existing literature (see, for example, [31, 32]). This result is in line with our expectations since income is an enabling factor in health care service utilization and individuals with higher income will have easier access to health care professionals. Furthermore, the magnitude of the marginal effects indicate that this positive relationship increases gradually with higher levels of household income. However, this finding may also interpreted as one of the targets of the HTP, which is easier access to health care services for the poor segment of population, has not been reached yet. This argument indicates that policy makers in Turkey should focus on equity in the utilization of health care services to provide equal treatment opportunity for equal need regardless of socio-economic status. In this context, it is clear that increasing PPMU widely depends on easier access, namely both geographically and financially. The results of this study, however, show that Turkey is far from achieving its aim of easier access to health care services.

Another reason of increasing PPMU in the country especially after 2012 is that pharmacies have collected co-payments for hospitals since 2010 during the purchase of prescribed medicines. This reform may lead to individuals to use non-prescribed, especially for inexpensive medication to avoid hospital co-payments. On the other hand, in the case of expensive medicines, individuals may prefer to pay co-payments by using prescribed medicine.

The findings of this current study also indicate that there is a statistically insignificant relationship between education and both PPMU and NPMU, contradicts with the existing literature, which indicates a negative relationship between education and over-use of pharmaceuticals [33, 34]. This finding can be interpreted as an evidence of a weak relationship between education and health literacy in Turkey. Based on this result, it can be concluded that public policies in Turkey should focus on increasing health literacy to support PPMU. The existing literature also indicates females having a higher likelihood of using health care services compared to males [35]. In line with this existing literature and our expectations, the results of this study indicate that this fact is reflected in medicine use as well. This finding can be attributed to women’s biological endowments; phycology and their relative health status (see, for example, [24, 36–38]).

Finally, the magnitude of marginal effects differs by PPMU and NPMU. The marginal effects are useful in terms of interpreting the magnitude of the determinants of NPMU and PPMU. For NPMU, the highest effect stems from health status indicating that the most critical factor of NPMU. For PPMU, the highest marginal effects arise from age, the health status and the employment status of the individual indicating the importance of the need and predisposing factors. These findings indicate that individuals may prefer to consult a doctor when they have a relatively serious health problem.

The results of the current study indicate that decreasing NPMU largely depends on easier access to health care service utilization. Although having a health insurance has a positive relationship with PPMU, there is still a problem for individuals living a rural area and heaving a lower income level since they are more likely to NPMU. Further, health literacy and health care need are among the important factors affecting NPMU.

Conclusion

The aim of this study is to examine the main determinants of NPMU and PPMU in Turkey using the nationally representative Health Surveys. The results from this study indicate that the health status is an important determinant of both PPMU and NPMU since it has the highest marginal effect. This finding indicates that the need factor, health status, is a primary factor affecting pharmaceutical expenditures. Furthermore, health care access is also important to decrease NPMU in Turkey. However, both geographical and financial access should be considered when designing a public health policy.

Limitations

The limitations of the data are that it is not giving information about “daily doses of treatment” that can give a better idea about the medical appropriateness of the prescription use patterns we are observing. Another limitation is that as the prescription variety is not observed in the data, any calculation about the cost implications and efficiency conclusions of the pharmaceutical use patterns we are using is again impossible to flesh out.

Furthermore, we have used cross-section data since Health Surveys of Turkey do not follow the same households through time and, thus, individual heterogeneity cannot be explained due to the lack of longitudinal data. It is important to acknowledge that the formulation of the survey questions which are used in the empirical analysis can be regarded to be elusive. The questions used in this study do not specify the type of medication such as antibiotics or dietary supplements but only asks whether the individual has taken any medication with or without prescription within the past two weeks. However, the surveys and, hence, the analysis is still believed to hold relevant information and insight into the behavioral determinants of medicine use.

Finally, again the data do not allow us to investigate the relationship between doctor consultation and medicine use. In other words, we cannot focus on the association between health care utilization and pharmaceutical utilization.

Future studies

Notwithstanding the limitations mentioned above, this study makes an essential contribution to the existing literature by being the first study focusing on the prevalence and determinants of PPMU and NPMU in Turkey. For future research, examining PPMU and NPMU over time would be an important contribution to the existing literature, but this depends on the availability of the relevant longitudinal data that are not currently available for Turkey. Decomposing medicines into categories and investigating which of the components is most closely related to NPMU would also be potentially useful for policymakers. Mainly, we believe that this study will shed light and grow the focus to the increasing NPMU problem in Turkey, which attracts attention from the policymakers within the last couple of years.

Author contributions

SÖ and DB are responsible for study design. SÖ performed the data analysis. SÖ, DB, İCÖ and AÖÇ all contributed to writing and correcting the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Turkish Statistical Institute but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Consent for publication

All authors give consent for publication.

Footnotes

Health problem and chronic disease variables described in Table 2 are also regressed separately in the place of the health status variable, and the results are found to be robust. All results are available at upon request.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Selcen Öztürk, Email: selcen@hacettepe.edu.tr.

Dilek Başar, Email: dbasar@hacettepe.edu.tr.

İlhan Can Özen, Email: ozeni24@gmail.com.

Arbay Özden Çiftçi, Email: arbay@hacettepe.edu.tr.

References

- 1.Andersen Ronald, Newman John F. Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society. 1973;51(1):95. doi: 10.2307/3349613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daban F, Pasarín MI, Rodríguez-Sanz M, García-Altés A, Villalbí JR, Zara C, Borrell C. Social determinants of prescribed and non-prescribed medicine use. Int J Equity Health. 2010;9(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dengler R, Roberts H. Adolescents' use of prescribed drugs and over-the-counter preparations. J Public Health. 1996;18(4):437–442. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simoni-Wastila Linda. The Use of Abusable Prescription Drugs: The Role of Gender. Journal of Women's Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2000;9(3):289–297. doi: 10.1089/152460900318470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson Richard E., Pope Clyde R. Health Status and Social Factors in Nonprescribed Drug Use. Medical Care. 1983;21(2):225–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198302000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.OECD, OECD.Stat (database). 2019. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9. Accessed 10 August 2019.

- 8.IEIS. Turkish Pharmaceutical Market. 2018. http://ieis.org.tr/ieis/en/sektorraporu2018. Accessed 15 August 2019.

- 9.Daştan, İ., Çetinkaya, V. OECD Ülkeleri ve Türkiye’nin Sağlık Sistemleri, Sağlık Harcamaları ve Sağlık Göstergeleri Karşılaştırması. [Comparing Health Systems, Health Expenditures and Health Indicators in OECD Countries and Turkey] Sosyal Güvenlik Dergisi. 2015; 5(1): 104–134. Turkish.

- 10.OECD. OECD Health Data 2016: Comparative analysis of 30 countries. (Version: 15.06.2017). 2016; OECD, Paris.

- 11.Hone T, Gurol-Urganci I, Millett C, Başara B, Akdağ R, Atun R. Effect of primary health care reforms in Turkey on health service utilization and user satisfaction. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(1):57–67. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atun R, Aydın S, Chakraborty S, Sümer S, Aran M, Gürol I, Nazlıoğlu S, Ozgülcü S, Aydoğan U, Ayar B, Dilmen U, Akdağ R. Universal health coverage in Turkey: enhancement of equity. Lancet. 2013;382(9886):65–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stokes J, Gurol–Urganci I, Hone T, et al. Effect of health system reforms in Turkey on user satisfaction. J Glob Health. 2015;5(2):1–10. doi: 10.7189/jogh.05.020403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Republic of Turkey, Social Security Institution. Social Security System. http://www.sgk.gov.tr/wps/portal/sgk/en/detail/social_security_system (Accessed: 15.03.2019).

- 15.Kartal N, Arısoy S. OTC Grubundaki ilaçların avantaj ve dezavantajlarının incelenmesi. [Examining the advantages and disadvantages of OTC drugs] Health Care. 2017;4(4):314–321. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sağır M, Parlakpınar H. Akılcı İlaç Kullanımı. [Rational Drug Use] Inonu University Journal of Health Sciences. 2014;3(2):32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilhan MN, Durukan E, Ilhan SÖ, Aksakal FN, Ozkan S, Bumin MA. Self-medication with antibiotics: questionnaire survey among primary care center attendants. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1150–1157. doi: 10.1002/pds.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobi H, Meijer WM, de Jong-van den Berg LTW, Tuinstra J. (2003). Socio-economic differences in prescription and OTC drug use in Dutch adolescents. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(5):203–206. doi: 10.1023/A:1025836704150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen Merete W., Hansen Ebba Holme, Rasmussen Niels Kristian. Prescription and non-prescription medicine use in Denmark: association with socio-economic position. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2003;59(8-9):677–684. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0678-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordin M, Dackehag M, Gerdtham UG. Socioeconomic inequalities in drug utilization for Sweden: evidence form linked survey and register data. Soc Sci Med. 2013;77:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pappa E, Kontodimopoulos N, Papadopoulos AA, Tountas Y, Niakas D. Prescribed-drug utilization and polypharmacy in a general population in Greece: association with sociodemographic, health needs, health-services utilization, and lifestyle factors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(2):185–192. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0940-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, et al. Attitudes, beliefs and knowledge concerning antibiotic use and self-medication: a comparative European study. Pharmacoepidem Drug Saf. 2007;16(11):1234–1243. doi: 10.1002/pds.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Y, Knopf H. Self-medication among children and adolescents in Germany: results of the National Health Survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(4):599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qato DM, et al. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. Jama. 2008;300(24):2867–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kantor ED, et al. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999-2012. Jama. 2015;314(17):1818–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen RM. A behavioural model of families’ use of health services. Chicago: University of Chicago; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen Ronald M. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does it Matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):1. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Windi A. Determinants of medicine use in a Swedish primary health care population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(1):47–51. doi: 10.1002/pds.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Makhlouf CO, Schulein M, Kasparian C, Ammar W. Medication use, gender, and socio-economic status in Lebanon: analysis of a national survey. J Med Liban. 2002;5–6(50):216–25. [PubMed]

- 30.Paulose-Ram Ryne, Jonas Bruce S, Orwig Denise, Safran Marc A. Prescription psychotropic medication use among the U.S. adult population: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57(3):309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer S, Österle A. Socioeconomic determinants of prescribed and non-prescribed medicine consumption in Austria. Eur J Pub Health. 2014;25(4):597–603. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogler S, Österle A, Mayer S. Inequalities in medicine use in Central Eastern Europe: an empirical investigation of socioeconomic determinants in eight countries. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0261-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kickbusch IS. Health literacy: addressing the health and education divide. Health Prom Int. 2001;16(3):289–297. doi: 10.1093/heapro/16.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Prom Int. 2000;15(3):259–267. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertakis, K. D., Azari, R., Helms, L. J. et al. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000; 49(2):147–152. [PubMed]

- 36.Gomberg ESL. Historical and political perspective: women and drug use. J Soc Issues. 1982;38(2):9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1982.tb00115.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoehr G. P., et al. over-the-counter medication use in an older rural community: the Mo VIES project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(2):158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang F, Mamtani R, Scott FI, et al. Increasing use of prescription drugs in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidem Drug Saf. 2016;25(6):628–636. doi: 10.1002/pds.3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]