Abstract

Purpose:

Access to large genetic datasets, many of which are privately owned, is essential to precision medicine and other research protocols. Academic researchers are increasingly capitalizing on this privately-held data. Our goal is to understand these private-academic “genetic data partnerships.”

Methods:

We analyzed publications using human genetic data generated or held by major private genetic testing companies that were indexed in PubMed between 2011 and 2017.

Results:

We found: 1) the number of publications using private genetic data is increasing over time (from 4 in 2011 to 57 in 2017); 2) there are two main models of data-sharing, including researchers using existing private data held by industry (n=172) or researchers sending in new samples for analysis (n=6); 3) 45% of the publications were supported at least in part by the National Institutes of Health; and 4) the type of contributor consent is not disclosed/unclear in the publication almost half (43%) the time.

Conclusion:

Privately held or analyzed genetic databanks offer academic researchers the opportunity to efficiently access large amounts of genetic data. But more transparency should be encouraged, if not required, in order to ensure the proper notification of contributors and to further understand the use of public research funds for private collaborations.

Keywords: genetics, precision medicine, consent, private companies, academic researchers

Introduction

Precision medicine and other advances in genetic research promise to improve diagnosis and therapy for millions of patients. But they require access to massive amounts of genetic and related health data. The federal government is currently building the public health and genetic databank All of Us1—but the largest genetic databanks remain privately owned.2

23andMe, Color Genomics, and Gene by Gene dominate the $928 million genetic testing market.3 23andMe, with over 10 million consumers, controls one of the largest genetic and phenotypic databanks in the world.4 But, while recent press reports have focused on data-use deals with private entities (like the recent $300 million GlaxoSmithKline/23andMe agreement),5 academic researchers are also increasingly capitalizing on privately-held data. To explore the relationship in these private-academic “genetic data partnerships,” we assessed PubMed publications that utilized privately owned or generated human genetic data from 2011–2017.

Materials and Methods

Private genetic companies 23andMe, Ambry Genetics, Ancestry.com, Color Genomics, and Gene by Gene were selected for inclusion based on their feature in Research and Markets, a global market research resource, which based its delineation of “major industry players” by supply and demand, sales, and overall market opportunity.3 We excluded Illumina as it is primarily a sequencing hardware technology company.

First, we searched PubMed for 23andMe, Ambry Genetics, Ancestry.com, Color Genomics, and Gene by Gene from 2011–2017. Publications using human genetic data generated or held by a private company (n=181) were stratified based on those that included one or more authors with at least one academic affiliation (n=156) and those that included a first or last author who had at least one academic affiliation (as an indication of the level of involvement in the paper) (n=133). If the last “author” was a consortium, we assessed the second to last author. We also included all authors whom the article indicated should share first or last author credit.

Second, we identified two main models of how data are shared between academics and private industry by assessing the methods section regarding whether 1) the genetic data had been generated by the company and was then analyzed as part of the publication (n=172) or 2) the company processed samples acquired by the research team (n=6).

Third, we assessed support for the work including articles that disclosed at least some National Institutes of Health (NIH) support (n=81) and work that was entirely privately supported (n=34).

Last, we assessed the type of consent that the contributors provided for their research data usage including specific consent (e.g., to a particular research protocol of which the risks and benefits were delineated) (n=39); broad consent (e.g., to future non-specific uses of data) (n=56); exempt from consent (i.e. there was no legal or policy requirement that the researchers acquire informed consent) (n=8); mixed types of consent (i.e. for data coming from different databanks) (n=1); or the type of consent was unclear or unknown (n=77). If the article stated simply that “informed consent” or “written informed consent” was obtained, we coded as “unknown” as it was unclear whether clinical versus research consent had been obtained; and, if it was research consent, whether it was broad versus specific. Articles that referenced using the standard 23andMe database were coded as “broad consent,” as is typically used by the entity for its research participants, unless it indicated that specific consent was obtained (e.g., by saying that participants gave additional consent for that particular protocol or received compensation).

Results

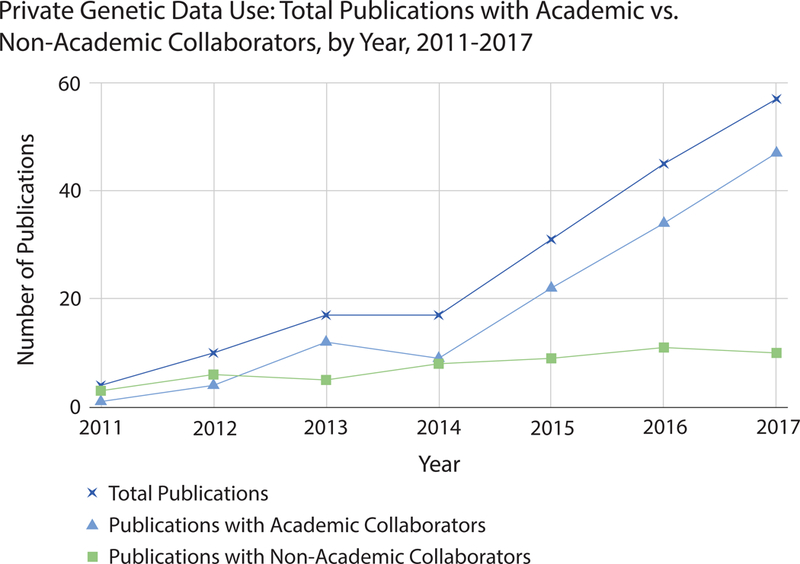

We found that the number of publications utilizing private genetic data continually increased from 4 in 2011 to 57 in 2017 for an overall total of 181 publications (Figure 1). The majority (86%) of these publications had at least one academic collaborator. Of the articles with an academic collaborator, the academic(s) were most often listed as first or last author or both (85%).

Figure 1.

Total publications with academic vs. non-academic collaborators from 2011–2017

Second, we found that almost all of papers with an academic author performed secondary analysis on data already existing in private databanks (95%). However, some also published data from their own participants that were sent for analysis by the private company or from participants that were recruited for a specific study via a private platform (3%).

Third, we assessed support for the work. We found that 45% of the articles disclosed at least some National Institutes of Health (NIH) support. Another major category was work that was entirely privately supported (19%). The rest of the articles stated there was no support, did not disclose support, or disclosed a mix of support sources.

Last, we found that it was challenging to discern from the published articles what type of informed consent was obtained from contributors. In almost half of the articles, we were not able to identify the method of informed consent or disclosure (43%). The second largest category was broad consent (31%), and 22% received specific consent. Eight articles stated that the work was exempt from informed consent requirements.

Discussion

Privately held or analyzed genetic and phenotypic databanks can offer academic researchers the opportunity to efficiently access large amounts of genetic and health data, and such collaborations are rapidly increasing. While some normative suggestions for best-practice collaborations exist,6 this is the first study to empirically establish an increase over time in publications indexed in PubMed generated from private genetic databanks in addition to evaluating contributor models, support, and informed consent structures. Our data demonstrate that it is generally unclear from the published literature what type of notification contributors are receiving regarding genetic data sharing, and that public support (e.g. from NIH) is being used to support some collaborations.

In a past survey assessing hypothetical contributors to a biobank, 67% agreed that clear disclosure of commercialization (in this case, of biospecimens) was warranted.7 Transparency both in informed consent forms, as well as subsequent publications, can serve as a check and balance to ensure that only contributors who feel comfortable with sharing are enrolled in secondary research protocols. Such transparency would allow not only contributors to have full disclosure regarding future uses of their data, but also reviewers and readers of subsequent publications to assess for themselves whether this standard has been met. In addition, as the federal government continues to invest in public data and biobanks, as well as data sharing initiatives,1,8 it is helpful to understand how federal support may be used to engage in private/public genetic data partnerships.

Limitations of our observations include that we did not specifically evaluate what individual researchers made up consortium authorship, type of consent was assessed by the publication as opposed to review of the related informed consent form or waiver, and publications utilizing genetic data from public banks were not trended over the same time period for comparison purposes.

In conclusion, given the continued and increasing emphasis on use of genetic data to improve patient care, we believe a more thorough understanding of the role of privately held or generated genetic data in academic publications will support a future assessment of whether such agreements require additional governance mechanisms – particularly when the research is publicly supported.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR002240) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (K01HG010496).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability: The full list of articles included in this literature review is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Contributor Information

Kayte Spector-Bagdady, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Chief, Research Ethics Service, Center for Bioethics & Social Sciences in Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School.

Amanda Fakih, Health Management & Policy, University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Chris Krenz, Center for Bioethics & Social Sciences in Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School.

Erica E. Marsh, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Michigan Medical School.

J. Scott Roberts, Health Behavior & Health Education, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Center for Bioethics & Social Sciences in Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. All of Us Research Program https://allofus.nih.gov/. Accessed April 26, 2019.

- 2.Wilbanks JT, Topol EJ. Stop the privatization of health data. Nature 2016;535:345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Research and Markets. Global Consumer DNA (Genetic) Testing Market - Forecasts from 2018–2023 https://www.researchandmarkets.com/research/w4fsmm/global_928?w=5. Accessed April 26, 2019.

- 4.23andMe. 23andMe for Healthcare Professionals https://medical.23andme.com/. Accessed April 26, 2019.

- 5.GSK. GSK and 23andMe sign agreement to leverage genetic insights for the development of novel medicines https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-and-23andme-sign-agreement-to-leverage-genetic-insights-for-the-development-of-novel-medicines/. Accessed April 26, 2019

- 6.Lehmann LS, et al. Navigating a research partnership between academia and industry to assess the impact of personalized genetic testing. Genet Med 2012;14:268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spector-Bagdady K, et al. Encouraging Participation and Transparency in Biobank Research. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:1313–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med 2015;372:793–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]