Abstract

Purpose:

Haploinsufficiency of DYRK1A causes a recognizable clinical syndrome. The goal of this paper is to investigate congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) and genital defects (GD) in patients with DYRK1A variants.

Methods:

A large database of clinical exome sequencing (ES) was queried for de novo DYRK1A variants and CAKUT/GD phenotypes were characterized. Xenopus laevis (frog) was chosen as a model organism to assess Dyrk1a’s role in renal development.

Results:

Phenotypic details and variants of 19 patients were compiled after an initial observation that one patient with a de novo pathogenic variant in DYRK1A had GD. CAKUT/GD data were available from 15 patients, 11 of whom present with CAKUT/GD. Studies in Xenopus embryos demonstrate that knockdown of Dyrk1a, which is expressed in forming nephrons, disrupts the development of segments of embryonic nephrons, which ultimately give rise to the entire genitourinary (GU) tract. These defects could be rescued by co-injecting wild-type human DYRK1A RNA, but not with DYRK1AR205* or DYRK1AL245R RNA.

Conclusion:

Evidence supports routine GU screening of all individuals with de novo DYRK1A pathogenic variants to ensure optimized clinical management. Collectively, the reported clinical data and loss of function studies in Xenopus substantiate a novel role for DYRK1A in GU development.

Keywords: CAKUT, kidney, exome sequencing, DYRK1A, Xenopus

INTRODUCTION

The dual-specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase (DYRK) family of protein kinases are conserved across species from lower eukaryotes to mammals.1 DYRK family members are activated by autophosphorylating a tyrosine residue in their activation loop.2 DYRK1A is the most extensively characterized member of the DYRK family, which in humans, is encoded by the DYRK1A gene located in the Down syndrome critical region of chromosome 21.3 A growing body of literature implicates a strong causal relationship between DYRK1A haploinsufficiency and a recognizable syndrome known as DYRK1A-related intellectual disability syndrome.3-5 In addition to intellectual disability (ID), other frequently occurring features include: intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), difficulty feeding (DF) with failure to thrive (FTT), microcephaly, seizures, dysmorphic facial features, and developmental delays (DD),5 while additional phenotypic features are observed less commonly.5,6 Although many features of this syndrome are well-characterized; the full phenotypic spectrum has yet to be defined. This manuscript presents a cohort of individuals with de novo (when both parental samples available) DYRK1A single nucleotide variants (SNVs) or small deletions ≤10 base pairs and defines CAKUT/GD that have not been previously described in patients with DYRK1A syndrome. We also provide supporting evidence, using Xenopus embryos as a model, that DYRK1A, which is expressed in embryonic nephrons, is required for GU development and that two pathogenic variants of human DYRK1A are likely responsible for the CAKUT/GD phenotype. Together, these findings support the investigation of potential CAKUT/GD in the clinical workup of patients with DYRK1A-related ID syndrome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

The index patient was seen in the Renal Genetics Clinic (RGC) at Texas Children’s Hospital (TCH). Subsequently, patients who had ES in a clinical diagnostic laboratory [Baylor Genetics (BG)] were queried for de novo (except P1, P12 and P15) pathogenic [except P10 (likely pathogenic), P5, P7, and P17 called as VUS in the initial report] variants in DYRK1A. Inclusion criteria also included: 1) variant confirmation using Sanger sequencing, and 2) lack of other variants that could explain the phenotype observed. Exclusion criteria included multiple additional candidate genes that may be related to the phenotype. The final size of our cohort after applying those filters is 19 patients. Clinical phenotype information was collected from initial ES requisition form or contacting referring physicians. The Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol for the Protection of Human Subjects at Baylor College of Medicine. Consent was obtained for clinical genetic testing/exome sequencing from each family participating in this study.

ES and data analysis

ES was performed by previously published methods at BG.7,8,9 In brief, an Illumina paired-end pre-capture library was constructed with 1ug of DNA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina Multiplexing_SamplePrep_Guide_−1005361_D), with modifications as described in the BCM-HGSC Illumina Barcoded Paired-End Capture Library Preparation protocol.7 Four pre-captured libraries were pooled and then hybridized in solution to the HGSC CORE design (52Mb, NimbleGen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Exome Library SR User’s Guide (Version 2.2), with minor revisions. Sequencing was performed in paired-end mode with the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform, with sequencing-by-synthesis reactions extended for 101 cycles from each end with an additional cycle for the index read. With a sequencing yield of 12 Gb, 92% of the targeted exome bases were covered to a depth of 20X or greater. Illumina sequence analysis was performed with the HGSC Mercury analysis pipeline (https://www.hgsc.bcm.edu-/software/mercury), which moves data through various analysis tools from the initial sequence generation on the instrument to annotated variant calls (SNVs and intra-read indels). Variant interpretation was performed according to the most recent guidelines published by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG).10 Accordingly, only variants that met strict criteria were called pathogenic. Sanger sequencing confirmed all variants reported in this paper.

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Digoxygenin-11-UTP-labeled antisense RNA probe for dyrk1a was synthesized in vitro from Xenopus Genome Collection IMAGE clone 7687837 11 using SalI restriction enzyme and T7 polymerase. This clone carries the Xenopus tropicalis coding sequence for dyrk1a, therefore, both X. tropicalis and X. laevis embryos were stained to ensure proper detection of the target. Embryos were staged, fixed, and stained according to standard procedures12,13 using an anti-digoxygenin antibody (1:3000, Sigma 11093274910, St. Louis MO, USA) and BM Purple (Sigma 11442074001, St. Louis MO, USA).

Xenopus laevis embryos and microinjections

Xenopus eggs were obtained by standard means, placed in 0.3x MMR and fertilized in vitro.13 Blastula cleavage stages and dorsal versus ventral polarity were determined by established methods.12 Microinjections were targeted to the V2 blastomere at the eight-cell stage, which provides major contributions to the development of the pronephros.12,14,15 Ten nL of injection mix (described below) was injected into embryos. Ten ng of Dyrk1a morpholino 5’-TGCATCGTCCTCTTTCAAGTCTCAT-3′16 or Standard morpholino 5′-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3′ was co-injected with 50 pg RNA (either control β- galactosidase, wild-type human DYRK1A, DYRK1A R205* or DYRK1A L245R) along with 1 ng membrane-RFP RNA17 as a lineage tracer to verify that the correct blastomere was injected. Details about design and statistical analysis are included in Supplemental Methods.

Immunostaining

Embryos were staged,12 fixed, and immunostained18 using established protocols. Proximal tubule lumens were labeled with the antibody 3G8 (1:30, European Xenopus Resource Centre, Portsmouth, United Kingdom), while the cell membranes of distal and connecting tubules were labeled with antibody the 4A6 (1:5, European Xenopus Resource Centre, Portsmouth, United Kingdom).19 Rabbit anti-red fluorescent protein (anti-RFP) (1:250, MBL International, Woburn, MA, USA) antibody was used to detect the RFP tracer. Goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 555 (1:500, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) secondary antibodies were used to visualize antibody staining.

Imaging

Embryos used for in situ hybridization were imaged on a Zeiss AxioZoom V16 with a 1X objective, Zeiss 512 color camera (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and extended depth of focus processing. Embryos used for immunostaining were scored and photographed using an Olympus SZX16 fluorescent stereomicroscope and Olympus DP71 camera (Olympus, Toyko, Japan). 3G8/4A6 immunostained kidney images were taken using a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Fixed embryos were cleared with BABB/Murray’s clearing solution for confocal imaging (1:2 volume of benzyl alcohol to benzyl benzoate). Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop.

RESULTS

CAKUT/GD identified in patients with DYRK1A variants

The index patient was seen in Renal Genetics Clinic (RGC) for the evaluation of ID, global DD, hypospadias, and congenital chordee. Trio ES (tES) revealed a novel de novo pathogenic p.G168fs single base pair deletion in DYRK1A. A subsequent query of the ES database at BG revealed a total of 18 additional individuals with SNVs or deletions ≤10 base pairs (as defined in methods) in DYRK1A among approximately 8000 probands. Phenotype and molecular information of these patients are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. Probands were mostly children ranging from 2 to 27 years of age. All 19 of these individuals had neurodevelopmental phenotypes consistent with loss-of-function of DYRK1A [MIM: 614104]. We subsequently contacted all referring physicians to obtain further details regarding the CAKUT/GD phenotypes. However, CAKUT/GD statuses of four patients remain unknown. Eleven out of fifteen (73%) individuals with available information presented with CAKUT including unilateral renal agenesis (URA), and/or GD including undescended testis, hypospadias, etc. (Table 2). One patient (P6) with URA was identified after this newly acquired association of DYRK1A with CAKUT was discussed with the referring physician.20 Probability of loss-of-function intolerance (pLI) score of DYRK1A is 1, indicating that this gene is intolerant to loss-of-function variants.21

Table 1.

Demographics, molecular data, and phenotype of 19 patients with SNVs and small indels (<10bp) in DYRK1A identified by clinical exome sequencing

| Patient number |

Age (years) |

Gender | Ethnicity | Nucleotide change |

AA change |

Novel Variant |

DF/ FTT |

FD | Microcephaly | Seizures | ID | DD | Renal/ GU |

ASD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1* | 2.3 | F | Caucasian | c.452dupT | p.N151fs | − | + | + | + | − | ukn | M,S | + | ukn |

| P2* | 3.3 | M | Caucasian | c.461delA | p.K154fs | − | + | + | + | + | + | M,S | + | + |

| P3 | 9.5 | F | Caucasian | c.489_495del | p.L164fs | + | + | + | + | + | + | M,S | + | + |

| P4 | 11 | M | Hispanic | c.501delA | p.G168fs | + | − | + | + | + | + | G | + | ukn |

| P5 | 2 | M | Caucasian | c.517G>T | p.V173F | + | + | + | + | + | ukn | S | nRUS | ukn |

| P6* | 5.1 | M | Not specified | c.613C>T | p.R205X | − | − | + | + | − | ukn | U | + | + |

| P7* | 7 | F | Vietnamese | c.734T>G | p.L245R | − | − | + | + | − | + | M,S | + | ukn |

| P8 | 20.5 | M | Caucasian | c.787C>T | p.R263X | − | + | + | + | + | + | M,S | + | + |

| P9 | 5.7 | M | Caucasian | c.986_995del | p.S329fs | + | + | + | + | + | + | G | + | + |

| P10 | 9.8 | M | Middle Eastern | c.1042G>A | p.G348R | + | − | + | ukn | + | + | G | nRUS | ukn |

| P11 | 13.5 | M | Not specified | c.1098+1G>A | N/A | − | − | + | + | + | ukn | G | ukn | + |

| P12 | 27.1 | M | Not specified | c.1162dupG | p.A388fs | − | + | ukn | + | + | + | G | + | ukn |

| P13 | 14.8 | F | Not specified | c.1217_1220del | p.K406fs | + | + | ukn | ukn | + | ukn | M | ukn | + |

| P14 | 13.8 | F | Not specified | c.1309C>T | p.R437X | − | − | ukn | + | − | + | M,S | ukn | ukn |

| P15 | 10.1 | F | Hispanic | c.1309C>T | p.R437X | − | − | + | + | + | ukn | S | nRUS | ukn |

| P16 | 5.7 | F | Filipino | c.1309C>T | p.R437X | − | − | + | + | + | + | G | nRUS | ukn |

| P17 | 19.6 | F | Caucasian | c.1400G>A | p.R467Q | − | + | + | + | − | + | G | ukn | ukn |

| P18* | 18.5 | M | Caucasian | c.1399C>T | p.R467X | − | − | + | + | + | + | M,S | + | + |

| P19 | 9.4 | M | Hispanic | c.1478dupT | p.S494fs | + | ukn | + | + | + | + | M,S | + | + |

ASD: Autism spectrum disease (HP:0000717), DD: Developmental delays; Global (G; HP:0001263), Motor (M; HP:0001270), Speech (S; HP:0000750), Unspecified (U), DF/FTT: Difficulty feeding (HP:0011968)/ failure to thrive (HP:0001508), FD: Facial dysmorphism (HP:0001999), GU: Genitourinary; Normal renal ultrasound nRUS, Unknown ukn, + denotes phenotype observed (see Table 2 for more details), ID: Intellectual disability (HP:0001249)

denotes published patients20

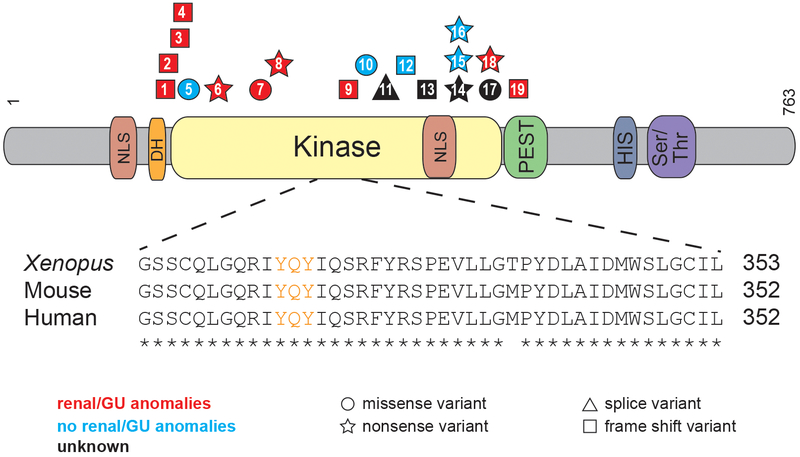

Figure 1. CAKUT associated with DYRK1A variants in patients with DYRK1A-related intellectual disability syndrome.

Schematic shows the DYRK1A protein domains. Shapes, which identify the type of variant (squares=frame shift variants, circles=missense variants, stars=nonsense variants, triangles=splice variants), are positioned where DYRK1A patient variants impact the amino acid sequence. Patient variants are labeled by patient number as listed in Tables 1 and 2. Variants that result in CAKUT are red, those that do not result in CAKUT are blue, and those in which the effects on CAKUT status are unknown are black. Protein domains are abbreviated as follows: NLS=nuclear localization signal, DH=DYRK homology box, PEST= proline (P), glutamic acid (E), serine (S), and threonine (T), HIS=histidine and Ser/Thr=Serine/Threonine. Inset shows highly conserved sequence surrounding the activation loop (labeled in orange) of the kinase domain.

Table 2.

Available information about genitourinary (GU) phenotype of patients reported in this study. Eleven patients have GU phenotype. This strongly suggests an important role for DYRK1A in GU tract development.

| Case Number |

SNV | Segregation | Renal or GU Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | p.N151fs | Mother negative, father's sample unavailable | Mild unilateral pelviectasis (HP:0010946) and frequent UTIs (HP:0000010) |

| P2 | p.K154fs | De Novo | Genital anomalies (HP:0000078) |

| P3 | p.L164fs | De Novo | Kidney abnormalities (not specified; HP:0000077) |

| P4 | p.G168fs | De Novo | Hypospadias (HP:0000047), micropenis (HP:0000054), and congenital chordee (HP:0000041) |

| P5 | p.V173F | De Novo | Renal ultrasound is normal with normal genitalia on exam |

| P6 | p.R205X | De Novo | Left renal agenesis (HP:0000122) |

| P7 | p.L245R | De Novo | Left renal agenesis (HP:0000122) |

| P8 | p.R263X | De Novo | Shawl scrotum (HP:0000049) and history bilateral orchiopexy (HP:0000028) |

| P9 | p.S329fs | De Novo | Hypospadias (HP:0000047) and kidney abnormalities (tiny echogenic foci) |

| P10 | p.G348R | De Novo | Normal renal ultrasound |

| P11 | c.1098+1G>A | De Novo | Unknown |

| P12 | p.A388fs | Mother negative, Father is mosaic | Frequent UTI (HP:0000010) |

| P13 | p.K406fs | De Novo | Unknown |

| P14 | p.R437X | De Novo | Unknown |

| P15 | p.R437X | Mother negative, father's sample unavailable | Normal renal ultrasound |

| P16 | p.R437X | De Novo | Normal renal ultrasound |

| P17 | p.R467Q | De Novo | Unknown |

| P18 | p.R467X | De Novo | Orchiopexy (HP:0000028) and inguinal hernia (HP:0000023) |

| P19 | p.S494fs | De Novo | Bilateral inguinal hernias (HP:0000023) but no renal ultrasound |

A majority of the variants found in DYRK1A are loss-of-function and are found in the kinase domain.

Many of the variants found in this cohort are found in the kinase domain [14 out of 17 (82%)], which spans from residues 159-479, and 11 out of 17 (65%) are thought to undergo nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), as they result in premature stop codons (https://nmdpredictions.shinyapps.io/shiny/) (Figure 1). Of the remaining six variants, one affects splicing, one escapes NMD (p.S494fs), and four are missense variants. The four missense variants are all found in the kinase domain in four individuals. Of these four individuals with missense variants, P7 was diagnosed with URA (p.L245R), P5 and P10 had normal renal ultrasounds (p.V173F and p.G348R), and P17 has an unknown CAKUT status (R467Q). Because these variants still lead to other DYRK1A-syndrome features such as ID, they may be important for the catalytic activity or conformational stability of DYRK1A. In fact, in a separate DYRK1A structural study the R467Q variant was found to be a part of a network of electrostatic interactions thought to play a role in the stability of the DYRK1A protein.22 Additionally, the L245R variant was found to prevent autophosphorylation of DYRK1A’s activation loop in HEK293 cells23 and was shown to be catalytically inactive via an in vitro kinase assay.24 Out of the three variants not found in the kinase domain, two are just N-terminal (N151fs, K154fs) and the last is found just C-terminal (to kinase domain) in the PEST domain (S494fs). Although, theoretically, all variants that are more N-terminal should result in NMD, a majority of the variants reside in the kinase domain for unknown reasons that should be studied further.

Xenopus laevis as a model of GU development

DYRK1A’s amino acid sequence is highly conserved among amniotes (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene). Even though the N- and C-terminal regions diverge in invertebrates, the amino acid sequence of the kinase domains are similar indicating the importance of this protein throughout evolution. In order to model CAKUT/GD associated with human DYRK1A loss-of-function variants using Xenopus laevis embryos (hereafter referred to simply as Xenopus), we analyzed the conservation of the whole DYRK1A protein sequence, focusing on the kinase domain. Human and Xenopus DYRK1A proteins are 91.3% identical over the entire amino acid sequence (Figure S1A). Additionally, the kinase domain, which is where a majority of the variants that cause CAKUT/GD (in this study) are found, is 97.5% identical to the human protein (Figure 1). Importantly, the human and Xenopus kinase activation loop sequence, which is essential for the kinase activity of DYRK1A, are identical.

Xenopus produces large clutch sizes with hundreds of embryos that develop externally, and unilateral embryo injections allow for tissue-targeted knockdowns that are specific to organs such as the kidney.14 Their embryonic kidney, the pronephros, can easily be visualized and imaged through a transparent epidermis, and they develop a fully functional kidney in ~56 hours.25 Xenopus was chosen because it is an established model of nephron development, and gene expression studies demonstrate that the developing Xenopus nephron is anatomically and functionally similar to the mammalian nephron.26- 28 The embryonic pronephros is the precursor to the mesonephric and metanephric kidney in mammals, and subsequent GU development is dependent upon this structure. Specifically, as the pronephros extends toward the cloaca, the mesonephric nephrons form adjacent to the elongating nephric duct, also known as the Wolffian duct.29 The ureteric bud, which is required for the development of the collecting duct system in mammals, then branches from this duct. Because the Wolffian duct is required for GU development in males and Müllerian duct elongation, necessary for normal female anatomy, depends upon the development of the Wolffian duct,30,31 the development of the pronephros is critical to both renal and genital development in mammals. Thus, although it is not a well-established model for studying genital formation, the Xenopus pronephros is essential for development of the mesonephric/Wolffian duct and subsequently the Müllerian duct, which are required for GU development.32,33

dyrk1a is expressed in the Xenopus kidney and in vivo knockdown demonstrates its role in kidney development.

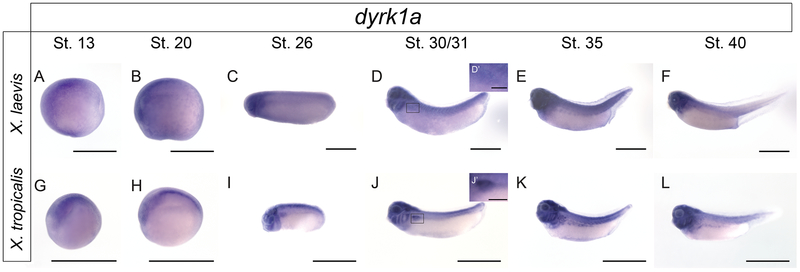

To assess whether dyrk1a is expressed in the Xenopus kidney, in situ hybridization was performed across developmental stages in both X. laevis and X. tropicalis (Figure 2). dyrk1a expression is seen in the pronephros in several stages of both X. laevis and X. tropicalis embryos during kidney development, suggesting that it may be important for nephrogenesis.

Figure 2. In situ hybridization of dyrk1a across developmental stages demonstrates kidney expression in X. laevis and X. tropicalis.

To demonstrate spatial-temporal expression of dyrk1a in the kidney, in situ hybridization was performed. Given that the RNA probe was designed against the X. tropicalis sequence, both species were analyzed. Pronephric kidney development occurs between stages 12.5-40. Expression of dyrk1a can be visualized in stage 31-40 embryos suggesting Dyrk1a may be important for kidney development. For clarity, insets (D’ and J’) for stage 30/31 tadpole kidneys with 200μm scale bars have been added. All other scale bars represent 1000μm.

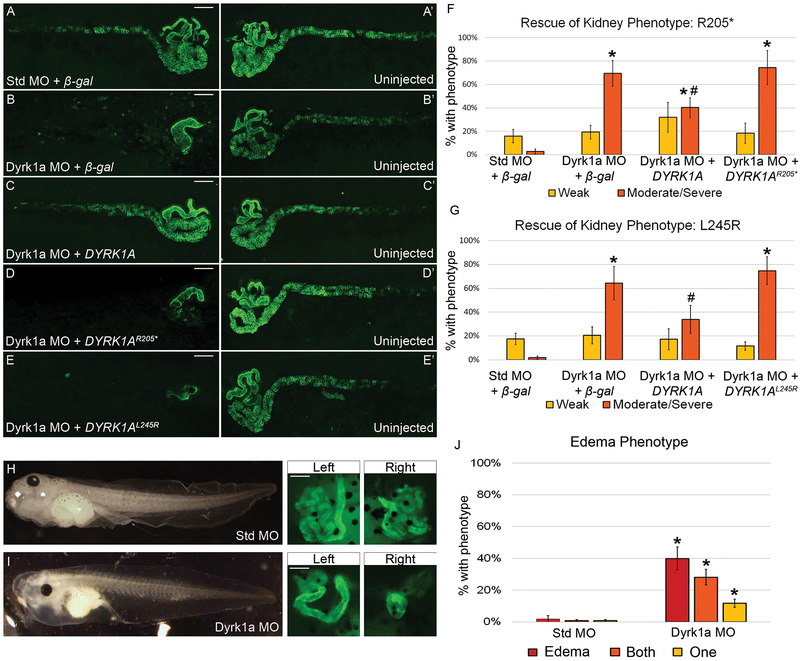

To examine dyrk1a’s role in renal development in Xenopus laevis, an anti-sense morpholino (MO) that blocks translation was used to knock down endogenous Dyrk1a protein expression. Xenopus laevis has two copies of the dyrk1a gene because of its allotetraploid genome. Both dyrk1a transcripts are targeted by the Dyrk1a MO used in this study (Figure S1B). Western blot analysis was used to confirm that the MO correctly targets Xenopus dyrk1a RNA (Figure S2B). Knockdown experiments were used to determine whether loss of Dyrk1a function in Xenopus results in disruption of kidney development. Embryos were injected in a single V2 blastomere to target a single kidney, leaving the other as an internal control. Knockdown with a Dyrk1a MO resulted in abnormal pronephroi when immunostained with antibodies 3G8 and 4A6, which label the proximal tubules and the distal and connecting tubules (nephric duct), respectively (Figure 3B). Loss of Dyrk1a primarily affected the proximal and distal tubules, with defects in the connecting tubules (nephric duct) occurring only in embryos with a more severe phenotype.

Figure 3. Loss of Dyrk1a affects kidney development in Xenopus laevis.

(A-E’) Embryos were unilaterally injected at the 8-cell stage with 10ng of Dyrk1a MO or Standard MO (Std MO) along with 50 pg β-gal, wild-type, DYRK1AR205*, or DYRK1AL245R RNA. Stage 40 tadpoles were stained with kidney antibodies 3G8, which label the proximal tubules and 4A6, which labels the distal and connecting tubules. Letters without apostrophes (A-E) represent the injected side, whereas letters with apostrophes (A’-E’) represent the uninjected side. (B) Knockdown with a translation-blocking Dyrk1a MO disrupts kidney development which can be partially rescued (C) by co-injecting with wild-type human DYRK1A RNA but not (D-E) DYRK1AR205* or DYRK1AL245R RNA. (A) Co-injection of a Standard MO and β-gal serve as a negative control. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (F) The graph demonstrates a significant difference between embryos injected with either Dyrk1a MO + β-gal or Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1AR205* versus with Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1A suggesting successful rescue with human DYRK1A but not with the nonsense RNA. (G) The second graph demonstrates a significant difference between embryos injected with Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1AL245R versus with Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1A, which suggests that the missense RNA also fails to rescue. Significance was established against embryos that had a moderate or severe kidney phenotype (orange bar) and excluded embryos that had a weak phenotype (yellow bar). (F) * (asterisk) = p<0.001 comparing individual experimental groups to Standard MO + β-gal. # (pound sign) = p<0.006 comparing Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1A to Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1AR205*. (G) * (asterisk) = p<0.001 comparing Standard MO + β-gal to Dyrk1a MO + β-gal or Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1AL245R. # (pound sign) = p<0.05 comparing Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1A to Dyrk1a MO + DYRK1AL245R. For edema assays, embryos were injected at the 4-cell stage in both ventral cells to target both kidneys while avoiding the dorsal cells fated to become the heart and liver, which can also lead to edema. (H) Embryos injected with the Standard MO did not develop edema while embryos injected (I) with the Dyrk1a MO did develop edema and also suffered from abnormal kidney formation. (J) The graph demonstrates a significant difference in edema and kidney abnormalities in embryos injected with either Standard MO or Dyrk1a MO. * (asterisk) = p<0.008 comparing Standard MO to Dyrk1a MO embryos with edema, defects in one, and defects in both kidneys. Error bars represent standard error. For ease of comparison of (n) and p-values across conditions, please refer to Table S1-3.

Variants identified in DYRK1A-related ID syndrome fail to rescue Dyrk1a loss-of-function in Xenopus.

To assess if patient DYRK1A variants lead to pronephric anomalies as they do in Xenopus, rescue experiments were carried out upon MO-mediated Dyrk1a knockdown in Xenopus. To express human DYRK1A in Xenopus, three constructs with HA tags were generated: wild-type human DYRK1A, a truncating patient variant DYRK1AR205*, and a missense patient variant DYRK1AL245R. Western blot analysis was used to confirm that the wild-type human DYRK1A and DYRK1AL245R, ~95 kDa, and the truncated human DYRK1AR205* RNA constructs, ~25 kDa, could be successfully expressed in Xenopus (Figure S2C). Overexpression of the rescue dose (50pg) of either β-galactosidase (β-gal), wild-type DYRK1A, DYRK1AR205* or DYRK1AL245R RNA demonstrated no gain-of-function phenotype of either DYRK1A variant (Figure S3). The kidney anomalies caused by Dyrk1a knockdown were partially rescued by co-injecting wild-type human DYRK1A RNA (Figure 3C). However, neither DYRK1A R205* or DYRK1AL245R RNA rescued these anomalies (Figure 3D-E). Detailed descriptions of how embryos are scored can be found in Figure S4.

To assess whether Dyrk1a depletion affects kidney function, an assay was performed evaluating edema formation.18 Edema can be caused by a disruption in the kidneys’ ability to excrete excess fluid, but it can also be caused by heart or liver failure. Both the heart and liver arise from dorsal cells in Xenopus (Xenbase.org). To prevent knockdown in these tissues, embryos were injected with Dyrk1a MO or Standard MO in both ventral cells at the four-cell stage to affect both kidneys. Embryos injected with the Dyrk1a MO suffered from edema and abnormal kidneys, characterized by swelling in the chest cavity due to fluid retention (Figure 3I) while embryos injected with the Standard MO did not (Figure 3H). This technique suggests that loss of dyrk1a affects kidney function in Xenopus. Taken together, these data support a role for DYRK1A in pronephric development and strongly suggest that the DYRK1AR205* and DYRK1AL245R variants are responsible for the kidney anomalies observed in these patients.

DISCUSSION

Recent discoveries demonstrate that de novo pathogenic variants in DYRK1A cause a syndromic form of ID [OMIM: 614104]. The findings in the current study indicate that CAKUT/GD should be included as features associated with this syndrome.

CAKUT consist of a heterogeneous clinical spectrum, and how CAKUT arise is largely unknown. Thus, it is important to identify all genes and causal variants involved.34 Strong genetic causality of monogenic disease only accounts for 14% of CAKUT cases,35 and polygenic causes are speculated to occur but are largely unknown.36 Next-generation sequencing, specifically ES, has improved the discovery of novel causative genes that are important in GU development.37-39 Here, we report on a novel genetic contribution of DYRK1A to CAKUT/GD. We identified 17 unique variants in DYRK1A from clinical ES in 19 unrelated individuals. As summarized in Table 1, microcephaly, ID, DD, and seizure are some of the more common features of this syndrome.

Eleven out of fifteen (73% of those with available data) individuals in this study (Table 2) have CAKUT/GD, with 36% having renal anomalies, in addition to other organ involvement. While renal anomalies have been reported previously,20 broadly based phenotyping for CAKUT was not performed in previous studies.

Seven of the DYRK1A variants identified in our study were novel as they were absent in ClinVar as well as gnomAD/ExAc databases. Per inclusion criteria, most of DYRK1A variants were de novo and included truncating variants. This suggests a loss-of-function mechanism for variants causing this syndrome which further supports the findings of another group who proposed reduced kinase function as the cause.22

In addition, we determined that dyrk1a is expressed in the developing Xenopus kidney and found that dyrk1a knockdown results in abnormal tubules or complete loss of the kidney. This phenotype could be partially rescued by human DYRK1A RNA. However, a nonsense (R205*) and a missense (L245R) variant failed to rescue the phenotype, indicating that loss-of-function variants in this gene are likely causative for the observed phenotype in some patients. This suggests that DYRK1As kinase domain may be important for kidney development. Furthermore, Dyrk1a MO was injected into two cells to affect both kidneys, which resulted in edema suggesting that Dyrk1a is important for both kidney development and function. Although Xenopus is an established model to study kidney development, it has not been commonly used to study GD. However, our findings related to pronephric development are likely relevant to the mammalian GU tract, given the dependence of the formation of the male and female urogenital tract upon the nephric duct and the pronephros.

One limitation of this study is that we were not able to obtain GU information from all patients. Future plans for research include identification and studying the phenotype and underlying variants in a larger number of affected families. Furthermore, signaling pathways involved in DYRK1A-related CAKUT/GD should be investigated.

In summary, the phenotype of DYRK1A-related ID syndrome is expanded to include CAKUT/GD. Based on our data, we empirically recommend that individuals with DYRK1A syndrome undergo a renal ultrasound and a thorough genital physical exam.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to express our sincere gratitude to the patients and their families for their participation in this study. The human studies were supported in part by K12 DK0083014 Multidisciplinary K12 Urologic Research Career Development Program, R01DK078121 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases awarded to D.J.L., startup funding from the Department of Pediatrics (Renal Section to M.R.B.), and the Wood family foundation. We appreciate all the efforts by BG diagnostic laboratory faculty and staff. Xenopus studies were supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants (K01DK092320, R03DK118771 and R01 DK115655 to R.K.M.) and startup funding from the Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Research Center at the McGovern Medical School (to R.K.M.). Xenopus gene expression studies were also generously supported by Matthew W. State (UCSF) and Richard M. Harland (UC-Berkeley) and through National Institute of Mental Health grants (U01 MH115747-01A1 to M.W.S. and 1R21MH112158-01 to R.M.H.). We thank the instructors and teaching assistants of the 2017 Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Xenopus Course, in particular K.J. Liu and M.K. Khokha. We are grateful to the members of the laboratories of R.K. Miller and P.D. McCrea, as well as to M. Kloc, for their helpful suggestions and advice throughout this project. In particular, we thank H. Ji and P.D. McCrea for valuable constructs. J.C. Whitney and T.H. Gomez who took care of the animals, even during hurricane Harvey. We are grateful to the UTHealth Office of the Executive Vice President and Chief Academic Officer and the Department of Pediatrics Microscopy Core for funding the Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope used in this work. Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) under award number K08NS092898 and Jordan’s Guardian Angels (to G.M.).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine derives revenue from clinical exome sequencing offered by the Baylor Genetics Laboratories. Authors who are faculty members in the Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine are identified as such in the affiliation section. The authors declare no conflict of interest with the following exceptions: M.N.B. is the founder of Codified Genomics LLC, a genomic interpretation company.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aranda S, Laguna A, de la Luna S. DYRK family of protein kinases: evolutionary relationships, biochemical properties, and functional roles. FASEB J. 2011. February;25(2):449–62. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-165837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lochhead PA, Sibbet G, Morrice N, Cleghon V. Activation-loop autophosphorylation is mediated by a novel transitional intermediate form of DYRKs. Cell. 2005. June 17;121(6):925–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Møller RS, Kübart S, Hoeltzenbein M, et al. Truncation of the Down Syndrome Candidate Gene DYRK1A in Two Unrelated Patients with Microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. 2008. May;82(5):1165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcet JB, Faivre L, Malzac P, et al. The DYRK1A gene is a cause of syndromic intellectual disability with severe microcephaly and epilepsy. J Med Genet. 2012. December;49(12):731–6. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Bon BWM, Coe BP, Bernier R, et al. Disruptive de novo mutations of DYRK1A lead to a syndromic form of autism and ID. Mol Psychiatry. 2016. January;21(1):126–32. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzgerald TW, Gerety SS, Jones WD, et al. Large-scale discovery of novel genetic causes of developmental disorders. Nature. 2015. March 12;519(7542):223–8 doi: 10.1038/nature14135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bainbridge MN, Wang M, Wu Y, et al. Targeted enrichment beyond the consensus coding DNA sequence exome reveals exons with higher variant densities. Genome Biol. 2011;12(7):R68. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lupski JR, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Yang Y, et al. Exome sequencing resolves apparent incidental findings and reveals further complexity of SH3TC2 variant alleles causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Genome Med. 2013;5(6):57. doi: 10.1186/gm461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekheirnia MR, Bekheirnia N, Bainbridge MN, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the molecular diagnosis of individuals with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract and identification of a new causative gene. Genet Med. 2017. April;19(4):412–420. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015. May;17(5):405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morin RD, Chang E, Petrescu A, et al. Sequencing and analysis of 10,967 full-length cDNA clones from Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis reveals post-tetraploidization transcriptome remodeling. Genome Res 2006. June;16(6):796–803. Epub 2006 May 3. doi: 10.1101/gr.4871006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus Laevis (Daudin): A Systematical & Chronological Survey of the Development from the Fertilized Egg till the End of Metamorphosis.; 1994. doi: 10.1086/402265. [DOI]

- 13.Sive HL, Grainger RM, Harland RM. Early Development of Xenopus Laevis: A Laboratory Manual.; 2000. January 1;2012(1):129–32. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot067462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLay BD, Krneta-Stankic V, Miller RK. Technique to Target Microinjection to the Developing Xenopus Kidney. J Vis Exp. 2016. May 3;(111). doi: 10.3791/53799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moody SA, Kline MJ. Segregation of fate during cleavage of frog (Xenopus laevis) blastomeres. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1990;182(4):347–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02433495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong JY, Park J-I, Lee M, et al. Down’s-syndrome-related kinase Dyrk1A modulates the p120-catenin–Kaiso trajectory of the Wnt signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2012. February 1;125(Pt 3):561–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidson LA, Marsden M, Keller R, DeSimone DW. Integrin α5β1and Fibronectin Regulate Polarized Cell Protrusions Required for Xenopus Convergence and Extension. Curr Biol. 2006. May 9;16(9):833–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLay BD, Baldwin TA, Miller RK. Dynamin Binding Protein Is Required for Xenopus laevis Kidney Development. Front Physiol. 2019. February 26;10:143. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vize PD, Jones EA, Pfister R. Development of the Xenopus pronephric system. Dev Biol. 1995. October;171(2):531–40. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ji J, Lee H, Argiropoulos B, et al. DYRK1A haploinsufficiency causes a new recognizable syndrome with microcephaly, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and distinct facies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(11):1473–1481. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV., et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016. August 18;536(7616):285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evers JMG, Laskowski RA, Bertolli M, et al. Structural analysis of pathogenic mutations in the DYRK1A gene in patients with developmental disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2017. February 1;26(3):519–526. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widowati EW, Ernst S, Hausmann R, Müller-Newen G, Becker W. Functional characterization of DYRK1A missense variants associated with a syndromic form of intellectual deficiency and autism. Biol Open. 2018. April 26;7(4). doi: 10.1242/bio.032862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arranz J, Balducci E, Arató K, et al. Impaired development of neocortical circuits contributes to the neurological alterations in DYRK1A haploinsufficiency syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2019. March 1;127:210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vize PD, Carroll TJ, Wallingford JB. Induction, Development, and Physiology of the Pronephric Tubules. In: The Kidney: From Normal Development to Congenital Disease. ; March 15, 2003, Pages 19–50. doi: 10.1016/B978-012722441-1/50005-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou X, Vize PD. Proximo-distal specialization of epithelial transport processes within the Xenopus pronephric kidney tubules. Dev Biol. 2004. July 15;271(2):322–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raciti D, Reggiani L, Geffers L, et al. Organization of the pronephric kidney revealed by large-scale gene expression mapping. Genome Biol. 2008;9(5):R84. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackburn ATM, Miller RK. Modeling congenital kidney diseases in Xenopus laevis. Dis Model Mech. 2019. April 9;12(4). pii: dmm038604. doi: 10.1242/dmm.038604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romagnani P, Lasagni L, Remuzzi G. Renal progenitors: An evolutionary conserved strategy for kidney regeneration. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013. March;9(3):137–46. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi A. Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development. 2005. June;132(12):2809–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruenwald P The relation of the growing müllerian duct to the wolffian duct and its importance for the genesis of malformations. 10.1002/ar.1090810102. Published September 1941. [DOI]

- 32.Jansson E, Mattsson A, Goldstone J, Berg C. Sex-dependent expression of anti-Müllerian hormone (amh) and amh receptor 2 during sex organ differentiation and characterization of the Müllerian duct development in Xenopus tropicalis. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2016. April 1;229:132–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piprek RP, Pecio A, Kloc M, Kubiak JZ, Szymura JM. Evolutionary trend for metamery reduction and gonad shortening in anurans revealed by comparison of gonad development. Int J Dev Biol. 2014;58(10-12):929–934. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.140155rp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nestor JG, Groopman EE, Gharavi AG. Towards precision nephrology: the opportunities and challenges of genomic medicine. J Nephrol. 2018. February;31(1):47–60. doi: 10.1007/s40620-017-0448-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Ven AT, Connaughton DM, Ityel H, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing Identifies Causative Mutations in Families with Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018. September;29(9):2348–2361. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017121265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woolf AS. A molecular and genetic view of human renal and urinary tract malformations. Kidney Int. 2000. August;58(2):500–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gbadegesin R a, Brophy PD, Adeyemo A, et al. TNXB mutations can cause vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(8):1313–1322. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chatterjee R, Ramos E, Hoffman M, et al. Traditional and targeted exome sequencing reveals common, rare and novel functional deleterious variants in RET-signaling complex in a cohort of living US patients with urinary tract malformations. Hum Genet. 2012. November;131(11):1725–38. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1181-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanna-Cherchi S, Sampogna R V, Papeta N, et al. Mutations in DSTYK and dominant urinary tract malformations. N Engl J Med. 2013. August 15;369(7):621–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.