ABSTRACT

Nationally representative data from mother–child dyads that capture human milk composition (HMC) and associated health outcomes are important for advancing the evidence to inform federal nutrition and related health programs, policies, and consumer information across the governments in the United States and Canada as well as in nongovernment sectors. In response to identified gaps in knowledge, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the NIH sponsored the “Workshop on Human Milk Composition—Biological, Environmental, Nutritional, and Methodological Considerations” held 16–17 November 2017 in Bethesda, Maryland. Through presentations and discussions, the workshop aimed to 1) share knowledge on the scientific need for data on HMC; 2) explore the current understanding of factors affecting HMC; 3) identify methodological challenges in human milk (HM) collection, storage, and analysis; and 4) develop a vision for a research program to develop an HMC data repository and database. The 4 workshop sessions included 1) perspectives from both federal agencies and nonfederal academic experts, articulating scientific needs for data on HMC that could lead to new research findings and programmatic advances to support public health; 2) information about the factors that influence lactation and/or HMC; 3) considerations for data quality, including addressing sampling strategies and the complexities in standardizing collection, storage, and analyses of HM; and 4) insights on how existing research programs and databases can inform potential visions for HMC initiatives. The general consensus from the workshop is that the limited scope of HM research initiatives has led to a lack of robust estimates of the composition and volume of HM consumed and, consequently, missed opportunities to improve maternal and infant health.

Keywords: bioactives, breastfeeding, human milk microbiome, infant nutrition, lactation, maternal nutrition, milk volume, nutrients, nutrient composition, food composition database

Introduction

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the USDA are jointly mandated to publish the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Dietary Guidelines) every 5 y (1, 2). Since the 1990 edition, the Dietary Guidelines has provided guidance for Americans aged 2 y and older; however, the Agricultural Act of 2014 mandated that starting with the 2020–2025 edition, it must also provide guidance for women who are pregnant and infants and toddlers from birth to age 24 mo (P/B-24) (3). Nationally representative data on P/B-24 populations, including data from mother–child dyads that capture human milk composition (HMC) and associated health outcomes, are important to advancing the science base used to inform the Dietary Guidelines (4, 5) and Canada's Food Guide (6). In addition, these data would fill critical gaps in scientific knowledge to support a broad number of future nutrition and related health programs, policies, regulations, and consumer information across the federal governments in the United States and Canada as well as in the nongovernment sector.

The USDA's Agricultural Research Service (ARS) has maintained the United States’ primary food composition database, the National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (SR) (7, 8), which includes nutrient composition of human milk (HM). SR supports the country's work on food policy, research, dietary practice, and nutrition monitoring (8). It is used to derive much of the data in the standard Canadian food composition database, the Canadian Nutrient File, which also contains food and nutrient data unique to the Canadian market (9).

Publicly available HMC data are outdated; a literature review identified only 28 studies on macro- and micronutrient content of HM over 37 y (1980–2017), and most studies were published before 1990 with relatively small sample sizes and limited generalizability (10). Consequently, ARS collaborated with the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion of HHS and the sponsoring agency for this workshop, the Office of Nutrition Research of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the NIH of HHS, to hold the “Workshop on Human Milk Composition—Biological, Environmental, Nutritional, and Methodological Considerations” on 16–17 November 2017 in Bethesda, Maryland.

The aims of the workshop were to 1) discuss the scientific needs for HMC data; 2) explore the current understanding of factors affecting HMC; 3) identify methodological challenges in HM collection, storage, and analysis; and 4) develop a vision for a research program to develop an HMC data repository and database. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the workshop.

Overview of Workshop and Sessions

Federal agencies in the United States and Canada and non-federal academia participated in the workshop (Supplemental Table 1). Nonfederal experts were invited to inform federal agencies by presenting the state-of-the-science on topics. The workshop was divided into four sessions of theme-related presentations (Table 1) (11). A summary of each is provided next.

TABLE 1.

Workshop sessions and presenters

| Workshop session | Presentation | Presenters, panelists, and moderators1 |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Scientific Needs for Data on Human Milk | Perspectives from Federal Agencies | Kellie O Casavale,2 ODPHP, OASH, HHS |

| Perspectives from Nonfederal Academic Researchers | Shelley McGuire,3 Washington State University | |

| Panel discussion | Douglas Balentine,2 CFSAN, FDA, HHS | |

| Panel discussion | Mandy Brown Belfort,3 Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School | |

| Panel discussion | Bruce German,3 University of California, Davis | |

| Panel discussion | Deborah Hayward,2 Bureau of Nutritional Sciences, Health Canada | |

| Panel discussion | Erin Hines,2 NCEA, EPA | |

| Panel discussion | James P McClung,2 Military Nutrition Division, US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Department of Defense | |

| Panel discussion | Shelley McGuire,3 Washington State University | |

| Panel discussion | Cria G Perrine,2 National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC, HHS | |

| Panel Discussion | Catherine Spong,2 NICHD, NIH, HHS | |

| Panel discussion | Kathleen Rasmussen,3 Cornell University | |

| Moderator | Pamela Pehrsson,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

| Moderator | Kellie O Casavale,2 ODPHP, OASH, HHS | |

| Session 2: Influential Factors on Human Milk Composition | Biology of Lactation and Human Milk | Margaret (Peggy) Neville,3 University of Colorado, Denver (Emerita) |

| Components of Human Milk | Lactation and Milk: The Roughs and the Smooths, Milk's Constant and Dynamic Dimensions | Bruce German,3 University of California, Davis |

| Milk Proteins and Peptides: Bioactivity, Characterization, and Quantification | David Dallas,3 Oregon State University | |

| Micronutrients in Human Milk: Implications for Recommended Intakes and Study Design | Lindsay H Allen,2 USDA ARS Western Human Nutrition Research Center, Davis | |

| Milk's Non-Nutritive Components and Microbiome in Brief | Shelley McGuire,3 Washington State University | |

| Milk Exosomes and RNA Cargos | Janos Zempleni,3 University of Nebraska–Lincoln | |

| Panel discussion | Presenters (named previously) | |

| Moderator | Jaspreet KC Ahuja,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

| Primary Factors Affecting Lactation and/or Human Milk Composition | Considerations of Time Intervals, Timing, and Time Frame in Sampling Human Milk | Laurie Nommsen-Rivers,3 University of Cincinnati |

| Variation in Human Milk Composition: Maternal Factors | Ardythe L Morrow,3 Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center | |

| Factors that Affect Milk Composition: Maternal Diet | Kathleen Rasmussen,3 Cornell University | |

| Environmental Chemicals in Breast Milk and Formula | Erin Hines,2 NCEA, EPA | |

| Panel discussion | Presenters (above) | |

| Moderator | Jaspreet KC Ahuja,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

| Session 3: Considerations for Data Quality | ||

| Sampling Strategies | Population-Based Sampling: Practice and Considerations | Amy Branum,2 NCHS, CDC, HHS |

| Practical Considerations in Sampling Human Milk Composition and Breast Milk Intake Volumes in the US | Laurie Nommsen-Rivers,3 University of Cincinnati | |

| Considerations and Complexities in Standardizing Collection, Storage, and Analysis | Effects of Sampling, Sample Handling, and Analysis on Human Milk Composition Data: Retrospective View | Xianli Wu,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA |

| Considerations and Complexities in Standardizing Milk Collection and Storage: Focus on Micronutrients | Lindsay H Allen,2 USDA ARS Western Human Nutrition Research Center, Davis | |

| Considerations and Complexities in Standardizing Milk Collection, Storage, and Analysis: Milk Lipids and Microbiome | Mark McGuire,3 University of Idaho | |

| Considerations of Human Milk Analysis with Respect to Macronutrient Properties, Donor Milk Processing, and Milk Thickening | Jae Kim,3 University of California, San Diego | |

| Panel discussion | Presenters (above) | |

| Moderator | Xianli Wu,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

| Session 4: Developing a Vision to Establish a Research Program for Human Milk Composition | Best Practices for Human Milk Content Measurements, Analysis, and Databasing | Shankar Subramaniam,3 University of California, San Diego |

| Human Milk in the Internet of Food: How, What, When, Where, Why | Matthew Lange,3 University of California, Davis | |

| Sharing Visions | Overview of the ECHO Program | Manjit Hanspal,2 ECHO program, NIH, HHS |

| Nutrient Data Laboratory's Vision for the Human Milk Composition Database | Jaspreet KC Ahuja,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

| A Vision for the Human Milk Composition Database of the United States and Canada | Ardythe L Morrow,3 Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center | |

| Human Milk and Nutrition Research at NIH | Christopher J Lynch,2 NIDDK, NIH, HHS | |

| Panel discussion | Presenters (above) | |

| Moderator | Pamela Pehrsson,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

| Next Steps for Development of a Research Program Proposal | Pamela Pehrsson,2 BHNRC, ARS, USDA | |

Presenter affiliations are abbreviated as follows: ARS, Agricultural Research Service; BHNRC, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center; CFSAN, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition; ECHO, Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes; EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; HHS, US Department of Health and Human Services; NCEA, National Center for Environmental Assessment; NCHS, National Center for Health Statistics; NICHD, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; OASH, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health; ODPHP, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Federal participant.

Invited, nonfederal academic expert.

Session 1: Scientific Needs for Data on Human Milk

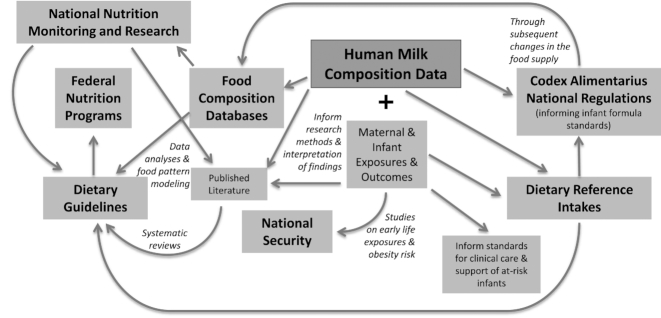

This first session (Table 1) focused on select, broad applications of HMC relevant to sectors of the federal governments (i.e., science, policy, and regulations) and research (i.e., in academic and medical settings) (Figure 1). The organizers acknowledged that additional stakeholders and priority areas beyond those represented exist.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of connections between human milk composition data and federal initiatives in the United States and Canada.

Dietary guidance and nutrition monitoring in the United States and Canada

The Dietary Guidelines is the cornerstone of federal food, nutrition, and health programs and policies in the United States. Its scientific basis is supported by systematic reviews of the literature and data analyses, including national estimates of chronic disease prevalence, food and nutrient intakes, nutrient content of foods, and food pattern modeling analyses (i.e., estimates of the effects on diet quality of possible changes in types or amounts of foods recommended) (1).

NHANES includes children in the United States starting from birth and provides important insights into nutrition and other exposures. Although substantive data are available on dietary intake, data on the variations in composition and volume of HM consumed by infants are limited and are needed to provide a more complete picture of infant exposures. Unfortunately, acquiring HM samples through NHANES to study their composition is not currently feasible due to small numbers of lactating participants in NHANES and considerations of respondent burden (Kathryn Porter, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, HHS, to Kellie Casavale, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, HHS, personal correspondence, January 2017).

HM is a unique complex biological substance. The milk produced by the mother and fed to her biological infant shares genetic and environmental similarities to that of the mother and child. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for ∼6 mo followed by continued breastfeeding as complementary foods are introduced through ≥1 y of age (12). Canadian health organizations recommend breastfeeding exclusively for the first 6 mo and sustained for ≤2 y or longer with appropriate complementary feeding (13, 14). Thus, for many infants, HM is either their sole source or a major contributor to their food intake.

The DRIs (15) underpin the Dietary Guidelines and numerous other public health initiatives (16), but DRIs for infants are almost entirely based on Adequate Intakes due to the lack of appropriate data with which to set RDAs. As a result, Estimated Average Requirements (EARs), needed for evaluating and monitoring the adequacy of intakes in populations, are not available for infants from birth to age 6 mo; for infants aged 7–12 mo, only EARs for protein, iron, and zinc have been determined. No Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Ranges (e.g., fat, protein, or carbohydrate intake) have been established for infants (17).

Food standards and regulations

The FDA, ARS, and Health Canada delegations, among others, help set standards through the Codex Alimentarius for infant formulas (18) that are used in conjunction with national regulations (19, 20). New HMC data could inform regulatory requirements for infant formulas for both term and preterm infants and guide manufacturers of HM fortifiers for preterm infants. In turn, these advancements would also lead to updates in food composition databases as products are reformulated.

Public health applications

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development within the NIH, among others, indicated interest in studying the impact of maternal characteristics on lactation performance and HM characteristics, including endocrine and metabolic factors and signaling pathways that regulate mammary differentiation in late pregnancy, at parturition, and during lactation, and genetic and epigenetic elements that affect heritability of lactation-related traits. Also, they acknowledged that the long-term implications of various exposures (e.g., therapeutic drugs and drugs of abuse, hormones, and dietary intake) on lactation performance are understudied.

At the time of the workshop, the CDC's web page on storage and handling of HM was one of the most visited among its nutrition and breastfeeding web pages (21), highlighting the relevance of integrating “real-world” exposures into the methodology for studying HMC. Pumping, storing, thawing, reheating, and using leftover HM expressed when the infant was younger may affect its composition and, therefore, what is ultimately consumed by the infant (22).

Influenced by the aforementioned expression, storage, and handling behaviors, HM can contain harmful bacteria (and viruses) but is known to also contain innate beneficial bacteria. In addition to the nutritive content of HM, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other federal departments are interested in better understanding and monitoring environmental chemicals present in HM (23). Establishing threshold values for potentially harmful environmental chemicals and bacterial counts (apart from beneficial bacteria) could help protect children consuming HM.

Ultimately, to understand the impact of early life nutrition exposures on long-term health, the role of HM in modulating infant outcomes must be studied. Current data are needed to answer the key question: Does breastfeeding modify the programming of infants at risk for metabolic disorders of infancy (inborn) as well as those that develop in childhood and adulthood (e.g., obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease)? Those answers may also play a role in improving national security in the United States because obesity is currently the most common reason for medical disqualification for military service (24). Decreasing the incidence of obesity in the United States may be a long-term investment to address its role in limiting the number of individuals qualified for military service.

Overview of perspectives from nonfederal academic researchers

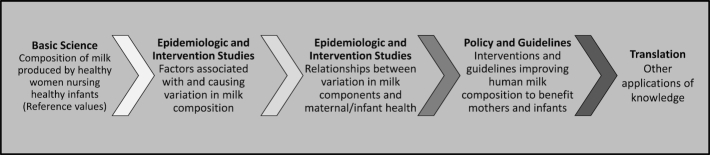

Nonfederal academic researchers described that research on HM and lactation can be categorized as addressing acute (illness prevention at early postpartum) and chronic (health promotion) health effects in mothers and infants. These health effects may differ in general infant populations and in more vulnerable populations such as infants born preterm. Answering basic scientific questions about HMC is a crucial foundational step from which consistent methods and approaches can be established to advance understanding HMC related to human health (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual sequence of research steps for understanding the relations between human milk composition and human health.

First, there is a need to characterize the components of HM produced by healthy women who are nursing healthy infants to establish reference values (e.g., averages and ranges of values, sometimes referred to as “normal” composition). Subsequently, epidemiologic and intervention studies would elucidate the relations between variability in HM and maternal and infant health outcomes; further details are described in the sections on Sessions 3 and 4.

Session 2: Influential Factors on Human Milk Composition

Session 2 addressed the biology of lactation and what is known and undiscovered about HMC and factors that affect it. HM is a biological fluid with many biologically active and living components undergoing synthesis, transport, and turnover on a regular basis. Changes in biosynthetic pathways and transport processes can lead to differences in composition, such as those that occur within the first few days postpartum.

Components of human milk

Macronutrients

HM provides amino acids for infant protein synthesis and growth as well as numerous proteins and peptides with other specific biological functions, including immunoglobulins, lactoferrin, lysozymes, proteases and protease inhibitors, bile salt-activated lipase, and peptide hormones (25–28). Similarly, the fat in HM is a complex collection of globules (referred to as milk fat globules) with diverse chemical structures. Digestible carbohydrate is the macronutrient with the highest concentration in HM, and lactose is considered the least variable macronutrient (29). HM also contains a high concentration of nondigestible carbohydrates, which are discussed later.

Micronutrients

Research is limited on micronutrient status of women who are lactating in the United States and Canada. International studies have shown that poor maternal nutritional status is associated with reduced concentrations of most vitamins and some minerals; intake of maternal supplements and fortified foods increases these concentrations in HM (30).

Work is underway outside the United States and Canada to determine the micronutrient composition of HM collected from well-nourished women to study the relation between maternal and infant micronutrient status. These data will enable comparisons for evaluating the micronutrient quality of HM from populations in the United States and Canada, contribute to evidence to support revisions to DRIs for mothers and infants, and clarify the effectiveness of micronutrient interventions during lactation (31, 32).

Other biologically active components

A myriad of nutritive components in HM do not fit the classical definition of “nutrients,” including hormones, enzymes, immune factors and cells, glycoproteins, nitrates/nitrites, and nucleotides. HM also contains many oligosaccharides, nondigestible carbohydrates (29), and new evidence is emerging on their structures and functions (22, 33–35). In addition, although previously considered sterile, HM is now known to contain a host of viable bacteria described as the HM microbiome, which appears to be unique to the individual (36). HM oligosaccharides are a food source for unique microbiological communities within the gastrointestinal tract of the infant. HM also contains extracellular vesicles called exosomes (37), which are secreted by cells and participate in cell-to-cell communication via transfer of regulatory cargos such as microRNAs. MicroRNA encapsulation in exosomes in HM protects them against degradation in the gastrointestinal tract (38, 39), and they are bioavailable (40–42).

Primary factors known to affect lactation and/or human milk composition

Time

HMC is influenced by time frames (e.g., lactation period, season, and circadian rhythms), time intervals (e.g., time since previous breast emptying and duration of feedings), and time relative to maternal exposures (e.g., meals, pathogens, and supplements).

Milk volume also changes over time, rising rapidly in the first week from <20 mL/d at birth to ∼500 mL/d at day 5 (43). Between ages 3 and 6 mo, the average HM volume consumed has been estimated to be ∼750 mL per 24 h among exclusively breastfed infants (43), but less is known about lower and upper limits of observed volumes consumed to support healthy growth among exclusively breastfed infants (44, 45).

Maternal characteristics and health

Maternal characteristics, including health status, can influence HMC. Maternal age at parturition is associated with differences in fatty acid HMC (46). In addition, maternal BMI and plasma insulin concentrations are reported to influence insulin concentrations in HM. In turn, women with high BMI during pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus, and insulin resistance are reported to have a decrease in HM volume (47, 48). In addition, premature delivery is associated with lower HM concentrations of DHA and vitamin A (49) and higher concentrations of protein (50).

Maternal genetic polymorphisms can influence immune and nutritional characteristics of HM. Most notably, polymorphisms in the fucosyltransferase genes FUT2 and FUT3 strongly influence the phenotype and quantity of the HM oligosaccharide fraction (51, 52). Polymorphisms in fatty acid desaturase genes influence the ability to elongate precursor fatty acid molecules and, hence, arachidonic acid and DHA availability in HM when dietary intake is limited (53). However, more research is needed on other polymorphisms that might impact HMC.

Maternal diet

Although maternal dietary intake can predict maternal nutritional status and it is a primary proximal determinant of HMC and volume, the literature on the association of dietary intake with HMC is mixed and limited (54). The relation of poor maternal dietary intakes to inadequate nutritional status of mothers and deficits in nutrients, other bioactive compounds, or the volume of HM remains unclear.

Environmental exposures

Exposures from air, soil, water, foods and beverages, personal care products, clothes, and furniture are known to result in environmental chemicals found in HM (55). These can include persistent lipophilic compounds (e.g., polychlorinated biphenyls), short-lived chemicals (e.g., bisphenol A), and other chemicals and metals (e.g., lead) (23, 56, 57).

Handling and processing

Infants frequently consume expressed HM (58). Donor HM is a type of expressed HM that has been donated to a milk bank, where it is pooled and pasteurized; handling and processing that can have a substantial impact on HMC (59–61). This form of HM is recommended for preterm infants when their own mother's milk is in short supply (12, 62, 63).

Session 3: Considerations for Data Quality in Standardizing Collection, Storage, and Analyses of Human Milk

Sampling strategies

Sampling participants

A framework for sampling participants is informed by study objectives, resources, target population, and ethical and legal considerations. For example, survey sampling can use a probability or nonprobability approach. Population surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics use a multistage probability approach to participant selection. However, it is difficult to sample women who are pregnant or lactating when using a nontargeted approach. Alternatively, developing a sampling frame for lactating mothers from maternity units of health care facilities is feasible.

Sampling human milk

A sampling strategy must also account for dynamic variations of HMC relative to the other factors (e.g., time, maternal diet, and genetic variation) and should adequately represent these variations across samples. Sampling should also address when compositional changes are substantial; for example, the sodium-to-potassium ratio of HM could differentiate colostrum from transitional HM and differentiate HM from exclusively/frequently feeding from that during weaning (43, 64).

Sampling to address project objectives

The sampling strategy must align with project objectives, which could be a reference or standards database. References report central tendency and variation based on representative samples (e.g., NHANES). Standards are prescriptive; they enable value judgments by incorporating targets (e.g., DRIs) (65) and would be appropriate if the objective is to represent what HMC and/or volume should be to align with current measures of healthy growth and development.

Complexities in standardizing collection, storage, and analyses of human milk

Advancing knowledge about HMC depends on the availability of valid and accurate methods for analysis in the HM matrix. As a fluid with living components, exposure to oxygen or light, freeze–thaw cycles, contact with surfaces, and other factors contribute to changes in HMC.

Macronutrients

New methods to measure macronutrients exist and can be more efficient. For example, rapid (<1 min) mid- and near infrared spectroscopy uses only 1 mL of HM to produce data comparable with traditional methods. Nanoflow LC coupled with highly sensitive tandem MS allows for identification and relative quantification of thousands of proteins and peptides from <100 µL of HM (27). However, absolute quantification based on MS will require the creation and use of standards. Strategies for determining the functional status of components after exposure to home storage and preparation conditions (e.g., refrigeration, freezing, and reheating) and processing (e.g., pasteurized donor HM) could utilize multiplexed ELISA systems.

Micronutrients

Uncertainties about the method and timing of HM collection and changes during lactation are challenges to characterizing micronutrient content of HM. Notably, the analysis in the HM matrix is unique from other biological specimens, and many older analyses are invalid. Although micronutrient analysis is tedious, the burden is reduced using MS for simultaneous and rapid analysis of some nutrients (e.g., some B vitamins). Recently, efficient and validated procedures have been developed to enable many micronutrients to be analyzed from small-volume samples (66).

Session 4: Developing a Vision for a Research Program Focused on Human Milk Composition

Existing research initiatives and resources

There is considerable interest in HM research among government departments, academia, and other stakeholder groups. At the time of the workshop, several NIH institutes were contributing approximately $32 million through ∼70 grants for which HM samples were being collected and analyzed (67), such as the NIH's Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program. Other large studies underway include the Mothers, Infants, and Lactation Quality (MILQ) study funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Evolutionary and Sociocultural Aspects of Human Milk Composition (INSPIRE) project supported by the National Science Foundation.

NIH's ECHO program (68), initiated in 2016, aims to understand the effects of environmental exposures on child health and development. Objectives include harmonizing and studying measures and sharing data on a public platform. ECHO has 20 cohorts in the United States that include HM samples, which will be measured mainly for microbiome and environmental components. The MILQ study, a cohort study in Denmark, Brazil, Bangladesh, and Gambia of ∼1000 women who are healthy, well nourished, not taking supplements, and lactating, aims to establish reference values for macro- and micronutrients in HM (69, 70). HM oligosaccharides and other constituents will also be analyzed. The INSPIRE project is similarly investigating HM oligosaccharides and the microbial community structure in HM in ∼400 subjects in 8 different developed and developing countries, including the United States (71). Other human milk research studies are also underway, including samples from North America (72–84).

A crucial element of all these projects is harmonization and improvement of HM collection, storage, and analytical methods. The latter 2 studies are collecting dietary intake data from mothers. These studies will contribute considerably to HMC research and understanding variability. However, other than the MILQ study, the focus of these studies is not on macro- and micronutrients, and results from the MILQ study may not be representative of US or Canadian populations (85).

Two examples of potential funding approaches were described during this session of the workshop. The first approach was to garner opportunities presented in the Strategic Plan for NIH Nutrition Research, a 10-y strategic plan to help guide NIH-supported nutrition research. The second approach was to utilize the NIH Common Fund, an entity that funds projects that are strategic investments for addressing unique, high-priority, broadly relevant, and transformative scientific challenges that no single NIH institute or center can address independently (86).

Research program visions

Research programs to address the previously mentioned important issues should include several features: 1) standardized and harmonized methods for sampling, collection, storage, and analysis (including analytical standards) to facilitate reproducibility and validation by other researchers and enable comparisons across studies; 2) coordinated, multicentered studies (extant and de novo) to create a foundational base for ongoing research; 3) a focus on HM from mothers in the United States and Canada (recognizing that complementary global collaborations would allow population comparisons); 4) inclusion of all HM components (known and unexplored); 5) collection of metadata on mother–infant dyads to provide insights on interrelations among genetic, nutritional, environmental, and other factors and infant and maternal health; 6) assessment of HMC and volume over the course of lactation; 7) measures of central tendency and variability of concentrations of components in HM; 8) development of estimates for both “reference” and “standard” HMC profiles; and 9) monitoring of these profiles in populations over time.

Data repository visions

A data repository could provide an integrated public platform for high-quality, curated HMC and metadata that meets standardized protocols. Key features should include well-characterized metadata, standardized vocabulary, and integration of Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability guiding principles for digital data sets (87). It could provide a user interface for depositing, retrieving, and analyzing data with computational and statistical tools for determining measures of central tendency and variability, comparative analyses, and the capability for detailed information retrieval, data query, mining, and visualization. A data repository should incorporate strategies and capabilities exemplified in the Metabolomics Workbench (88). An HM data repository should enable tracking, sharing, comparing, and dissemination of research data. A database structure could allow for incorporation into multiple data systems, including the USDA FoodData Central and the NIH Metabolomics Workbench.

Next Steps

Workshop attendees unequivocally supported the value of additional information from foundational research on HMC. Next steps of the US Federal Government may include (for some agencies) establishing federal workgroups, informed by additional experts, to develop frameworks. Efforts will aim to expand collaborations, including those with the Canadian Federal Government and external stakeholders, such as researchers, food and technology industry experts, professional organizations, and others, as appropriate.

Approaches to support the next steps include 1) prioritizing what to measure in HM and about mother–child dyads; 2) identifying and/or developing valid measures and standards to assess them; 3) characterizing the goals for evaluating HM samples that, collectively, adequately represent variation in HM in the United States; and 4) characterizing a future data repository and databases. Bringing this vision to fruition requires assessing lessons learned from strategies and capabilities from current and recent research programs in the United States, Canada, and globally.

Conclusion

The consensus of this NIH workshop was that research initiatives on HM in the United States and Canada have been limited in focus on this most fundamental and important biological food, leading to major knowledge gaps and, consequently, missed opportunities to improve health outcomes for mothers and children. Some of these gaps include lack of standardized collection, storage, and analytical methods for many components in the HM matrix, and limited understanding of changes in composition during lactation and from the impact of maternal and environmental factors. These have led to a lack of robust estimates of “reference” and “standard” HMC and volume in the United States and Canada. Filling these gaps would provide basic foundational tools for researchers to conduct comprehensive investigations on the factors that influence HMC and their relation to maternal and infant health. Subsequently, this work can lead to guidelines to inform public health policies, programs, and regulations for HM and related products and extensions into clinical practice applications to support short- and long-term goals for maternal and infant health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Namanjeet Ahluwalia, Amy Branum, Catherine Spong, Matthew Lange, and Shankar Subramaniam, who contributed substantively to the workshop sessions.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—KOC: wrote the manuscript, except for Session 4, which was written by JKCA. The manuscript was written based on presentation abstracts and commentaries written by the presenters and panelists; KOC: responsible for final content of the manuscript; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. All authors participated as speakers/panelists at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)/NIH workshop reported here. CJL is employed by NIDDK/NIH; all other authors have no conflicts of interest related to the workshop.

Notes

The findings and conclusions in this report are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of Health Canada, the US Army or Department of Defense, the US Department of Agriculture, the US Environmental Protection Agency, or the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). JQ's participation in this project was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the HHS administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and HHS. Per requirement of a personal conflict of interest management plan, JZ discloses that he serves as a consultant for PureTech Health, Inc.

Supplemental Table 1 is available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

Abbreviations used: ARS, Agricultural Research Service; Dietary Guidelines, Dietary Guidelines for Americans; EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; ECHO, Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes; HHS, US Department of Health and Human Services; HM, human milk; HMC, human milk composition; INSPIRE, Evolutionary and Sociocultural Aspects of Human Milk Composition project; MILQ, Mothers, Infants, and Lactation Quality study; P/B-24, women who are pregnant and children from birth to 24 mo of age; SR, National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary guidelines for Americans. [Internet] Version current 2015; [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990. [Internet]. Version current 22 October, 1990 [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/1608/text. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agricultural Act of 2014. [Internet]. H.R. 2642. Version current 7 February, 2014 [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/2642/text. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stoody EE, Casavale KO. Making the Dietary Guidelines for Americans “for Americans”: the critical role of data analyses. J Food Compos Anal. 2017;64:138–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raiten DJ, Raghavan R, Porter A, Obbagy JE, Spahn JM. Executive summary: evaluating the evidence base to support the inclusion of infants and children from birth to 24 mo of age in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans—“the B-24 Project.”. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):663S–91S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Katamay SW, Esslinger KA, Vigneault M, Johnston JL, Junkins BA, Robbins LG, Sirois IV, Jones-McLean EM, Kennedy AF, Bush MAA et al.. Eating well with Canada's Food Guide (2007): development of the food intake pattern. Nutr Rev. 2007;65(4):155–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, legacy. [Internet]. Version current April 2018 [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/nutrient-data-laboratory/docs/usda-national-nutrient-database-for-standard-reference/. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahuja JK, Moshfegh AJ, Holden JM, Harris E. USDA food and nutrient databases provide the infrastructure for food and nutrition research, policy, and practice. J Nutr. 2013;143(2):241S–9S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health Canada.Canadian Nutrient File. [Internet]. Version current 2015 [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/nutrient-data.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu X, Jackson RT, Khan SA, Ahuja J, Pehrsson PR. Human milk nutrient composition in the United States: current knowledge, challenges, and research needs. Curr Dev Nutr. 2018;2(7):nzy025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Workshop on human milk composition—biological, environmental, nutritional, and methodological considerations. [Internet]. Version current 15 June, 2018 [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/news/meetings-workshops/2017/workshop-human-milk-composition-biological-environmental-nutritional-methodological-considerations. [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Academy of Pediatrics. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. Nutrition for healthy term infants, birth to six months: an overview. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(4):206–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. Nutrition for healthy term infants, six to 24 months: an overview. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(10):547–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006.; [Google Scholar]

- 16. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes: applications in dietary assessment. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2005.; [Google Scholar]

- 18. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. Codex Alimentarius standard for infant formula and formulas for special medical purposes intended for infants. Codex Standard 72-1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration. Nutrient specifications for infant formula. 21 CFR 107.100. [Internet]. Version current 1 April, 2018 [cited 31 January, 2019]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=107.100. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Government of Canada. Food and drug regulations: Division 25: Human milk substitutes and food containing human milk substitutes. [Internet]. Version current 1 January, 2019 [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/c.r.c.,_c._870/page-84.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding: proper storage and preparation of breast milk. [Internet]. Version current 14 June, 2019; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/recommendations/handling_breastmilk.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ballard O, Morrow AL. Human milk composition: nutrients and bioactive factors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60(1):49–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. LaKind JS, Lehmann GM, Davis MH, Hines EP, Marchitti SA, Alcala C, Lorber M. Infant dietary exposures to environmental chemicals and infant/child health: a critical assessment of the literature. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(9):96002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Research Council. Assessing fitness for military enlistment: physical, medical, and mental health standards. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dallas DC, Guerrero A, Khaldi N, Castillo PA, Martin WF, Smilowitz JT, Bevins CL, Barile D, German JB, Lebrilla CB. Extensive in vivo human milk peptidomics reveals specific proteolysis yielding protective antimicrobial peptides. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(5):2295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dallas DC, Murray NM, Gan J. Proteolytic systems in milk: perspectives on the evolutionary function within the mammary gland and the infant. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2015;20(3–4):133–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nielsen SD, Beverly RL, Qu Y, Dallas DC. Milk bioactive peptide database: a comprehensive database of milk protein-derived bioactive peptides and novel visualization. Food Chem. 2017;232:673–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lonnerdal B. Human milk: bioactive proteins/peptides and functional properties. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2016;86:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang J, Kailemia MJ, Goonatilleke E, Parker EA, Hong Q, Sabia R, Smilowitz JT, German JB, Lebrilla CB. Quantitation of human milk proteins and their glycoforms using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(2):589–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dror DK, Allen LH.. Overview of nutrients in human milk. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(Suppl 1):278S–94S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Allen LH, Donohue JA, Dror DK. Limitations of the evidence base used to set recommended nutrient intakes for infants and lactating women. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(Suppl 1):295S–312S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Klein LD, Breakey AA, Scelza B, Valeggia C, Jasienska G, Hinde K. Concentrations of trace elements in human milk: comparisons among women in Argentina, Namibia, Poland, and the United States. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dallas DC, Martin WF, Strum JS, Zivkovic AM, Smilowitz JT, Underwood MA, Affolter M, Lebrilla CB, German JB. N-linked glycan profiling of mature human milk by high-performance microfluidic chip liquid chromatography time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(8):4255–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Varki A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology. 2017;27(1):3–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smilowitz JT, Lebrilla CB, Mills DA, German JB, Freeman SL. Breast milk oligosaccharides: structure–function relationships in the neonate. Annu Rev Nutr. 2014;34:143–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hunt KM, Foster JA, Forney LJ, Schutte UM, Beck DL, Abdo Z, Fox LK, Williams JE, McGuire MK, McGuire MA. Characterization of the diversity and temporal stability of bacterial communities in human milk. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Abels ER, Breakefield XO. Introduction to extracellular vesicles: biogenesis, RNA cargo selection, content, release, and uptake. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2016;36(3):301–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Izumi H, Kosaka N, Shimizu T, Sekine K, Ochiya T, Takase M. Bovine milk contains microRNA and messenger RNA that are stable under degradative conditions. J Dairy Sci. 2012;95(9):4831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Benmoussa A, Lee CH, Laffont B, Savard P, Laugier J, Boilard E, Gilbert C, Fliss I, Provost P. Commercial dairy cow milk microRNAs resist digestion under simulated gastrointestinal tract conditions. J Nutr. 2016;146(11):2206–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alsaweed M, Lai CT, Hartmann PE, Geddes DT, Kakulas F. Human milk cells and lipids conserve numerous known and novel miRNAs, some of which are differentially expressed during lactation. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolf T, Baier SR, Zempleni J. The intestinal transport of bovine milk exosomes is mediated by endocytosis in human colon carcinoma Caco-2 cells and rat small intestinal IEC-6 cells. J Nutr. 2015;145(10):2201–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Manca S, Upadhyaya B, Mutai E, Desaulniers AT, Cederberg RA, White BR, Zempleni J. Milk exosomes are bioavailable and distinct microRNA cargos have unique tissue distribution patterns. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Neville MC, Keller R, Seacat J, Lutes V, Neifert M, Casey C, Allen J, Archer P. Studies in human lactation: milk volumes in lactating women during the onset of lactation and full lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48(6):1375–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Onis M, Garza C, Onyango AW, Rolland-Cachera MF; le Comite de nutrition de la Societe Francaise. WHO growth standards for infants and young children. Arch Pediatr. 2009;16(1):47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. da Costa TH, Haisma H, Wells JC, Mander AP, Whitehead RG, Bluck LJ. How much human milk do infants consume? Data from 12 countries using a standardized stable isotope methodology. J Nutr. 2010;140(12):2227–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Argov-Argaman N, Mandel D, Lubetzky R, Hausman Kedem M, Cohen BC, Berkovitz Z, Reifen R. Human milk fatty acids composition is affected by maternal age. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(1):34–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nommsen-Rivers LA. Does insulin explain the relation between maternal obesity and poor lactation outcomes? An overview of the literature. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(2):407–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Riddle SW, Nommsen-Rivers LA.. A case control study of diabetes during pregnancy and low milk supply. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11(2):80–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Samano R, Martinez-Rojano H, Hernandez RM, Ramirez C, Flores Quijano ME, Espindola-Polis JM, Veruete D. Retinol and α-tocopherol in the breast milk of women after a high-risk pregnancy. Nutrients. 2017;9(1):14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bauer J, Gerss J.. Longitudinal analysis of macronutrients and minerals in human milk produced by mothers of preterm infants. Clin Nutr. 2011;30(2):215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Smilowitz JT, O'Sullivan A, Barile D, German JB, Lonnerdal B, Slupsky CM. The human milk metabolome reveals diverse oligosaccharide profiles. J Nutr. 2013;143(11):1709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kumazaki T, Yoshida A.. Biochemical evidence that secretor gene, Se, is a structural gene encoding a specific fucosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:4193–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Molto-Puigmarti C, Plat J, Mensink RP, Muller A, Jansen E, Zeegers MP, Thijs C. FADS1 FADS2 gene variants modify the association between fish intake and the docosahexaenoic acid proportions in human milk. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gonzalez-Cossio T. Effect of food supplementation to undernourished Guatemalan women on lactational performance: a randomized, double-blind trial. PhD dissertation. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University; 1994. Table 4.12 (p. 138), Figure 4.5 (p. 139). [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rawn DFK, Sadler AR, Casey VA, Breton F, Sun WF, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD. Dioxins/furans and PCBs in Canadian human milk: 2008–2011. Sci Total Environ. 2017;595:269–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. LaKind JS, Berlin CM, Mattison DR. The heart of the matter on breastmilk and environmental chemicals: essential points for healthcare providers and new parents. Breastfeed Med. 2008;3(4):251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lehmann GM, LaKind JS, Davis MH, Hines EP, Marchitti SA, Alcala C, Lorber M. Environmental chemicals in breast milk and formula: exposure and risk assessment implications. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(9):96001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Labiner-Wolfe J, Fein SB, Shealy KR, Wang C. Prevalence of breast milk expression and associated factors. Pediatrics. 2008;122(Suppl 2):S63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Valentine CJ, Morrow G, Reisinger A, Dingess KA, Morrow AL, Rogers LK. Lactational stage of pasteurized human donor milk contributes to nutrient limitations for infants. Nutrients. 2017;9(3):302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. John A, Sun R, Maillart L, Schaefer A, Hamilton Spence E, Perrin MT. Macronutrient variability in human milk from donors to a milk bank: implications for feeding preterm infants. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lima H, Vogel K, Wagner-Gillespie M, Wimer C, Dean L, Fogleman A. Nutritional comparison of raw, Holder pasteurized, and shelf-stable human milk products. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(5):649–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Perrin MT. Donor human milk and fortifier use in United States level 2, 3, and 4 neonatal care hospitals. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(4):664–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Perrine CG, Scanlon KS.. Prevalence of use of human milk in US advanced care neonatal units. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):1066–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lemay DG, Ballard OA, Hughes MA, Morrow AL, Horseman ND, Nommsen-Rivers LA. RNA sequencing of the human milk fat layer transcriptome reveals distinct gene expression profiles at three stages of lactation. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. WHO Multicenter Growth Reference Study Group. WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatrica Suppl. 2006;450:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hampel D, Dror DK, Allen LH. Micronutrients in human milk: analytical methods. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(Suppl 1):313S–31S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). [Internet]. Version current 2 February, 2019; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 68. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) program. [Internet]. Version current 15 August, 2017; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://www.nih.gov/echo. [Google Scholar]

- 69. US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. The Mothers, Infants and Lactation Quality (MILQ) project: a multi-center collaborative study. [Internet]. Version current 2 February, 2019; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/project/?accnNo=432056. [Google Scholar]

- 70. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, US National Library of Medicine. Establishing global reference values for human milk (MILQ). [Internet]. Version current 26 March, 2019; [cited 7 March, 2019]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03254329. [Google Scholar]

- 71. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Library of Medicine. Evolutionary and sociocultural aspects of human milk composition (INSPIRE). [Internet]. Version current 1 February, 2016; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02670278. [Google Scholar]

- 72. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PREVAIL cohort (Pediatric Respiratory and Enteric Virus Acquisition and Immunogenesis Longitudinal cohort). [Internet]. Version current 26 June, 2017; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/nvsn/prevail.html. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sitarik AR, Bobbitt KR, Havstad SL, Fujimura KE, Levin AM, Zoratti EM, Kim H, Woodcroft KJ, Wegienka G, Ownby DR et al.. Breast milk transforming growth factor β is associated with neonatal gut microbial composition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(3):e60–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Young BE, Patinkin Z, Palmer C, de la Houssaye B, Barbour LA, Hernandez T, Friedman JE, Krebs NF. Human milk insulin is related to maternal plasma insulin and BMI: but other components of human milk do not differ by BMI. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(9):1094–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Young BE, Patinkin ZW, Pyle L, de la Houssaye B, Davidson BS, Geraghty S, Morrow AL, Krebs N. Markers of oxidative stress in human milk do not differ by maternal BMI but are related to infant growth trajectories. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(6):1367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Perrin MT, Fogleman AD, Newburg DS, Allen JC. A longitudinal study of human milk composition in the second year postpartum: implications for human milk banking. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Alderete TL, Autran C, Brekke BE, Knight R, Bode L, Goran MI, Fields DA. Associations between human milk oligosaccharides and infant body composition in the first 6 mo of life. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(6):1381–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dingess KA, Valentine CJ, Ollberding NJ, Davidson BS, Woo JG, Summer S, Peng YM, Guerrero ML, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Ran-Ressler RR et al.. Branched-chain fatty acid composition of human milk and the impact of maternal diet: the Global Exploration of Human Milk (GEHM) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Woo JG, Guerrero ML, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Peng YM, Herbers PM, Yao W, Ortega H, Davidson BS, McMahon RJ, Morrow AL. Specific infant feeding practices do not consistently explain variation in anthropometry at age 1 year in urban United States, Mexico, and China cohorts. J Nutr. 2013;143(2):166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Woo JG, Herbers PM, McMahon RJ, Davidson BS, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Peng YM, Morrow AL. Longitudinal development of infant complementary diet diversity in 3 international cohorts. J Pediatr. 2015;167(5):969–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lipkie TE, Morrow AL, Jouni ZE, McMahon RJ, Ferruzzi MG. Longitudinal survey of carotenoids in human milk from urban cohorts in China, Mexico, and the USA. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0127729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dawodu A, Davidson B, Woo JG, Peng YM, Ruiz-Palacios GM, de Lourdes Guerrero M, Morrow AL. Sun exposure and vitamin D supplementation in relation to vitamin D status of breastfeeding mothers and infants in the Global Exploration of Human Milk study. Nutrients. 2015;7(2):1081–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gao X, McMahon RJ, Woo JG, Davidson BS, Morrow AL, Zhang Q. Temporal changes in milk proteomes reveal developing milk functions. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(7):3897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Moraes TJ, Lefebvre DL, Chooniedass R, Becker AB, Brook JR, Denburg J, HayGlass KT, Hegele RG, Kollmann TR, Macri J et al.. The Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development birth cohort study: biological samples and biobanking. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29(1):84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Picciano MF, McGuire MK.. Use of dietary supplements by pregnant and lactating women in North America. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(2):663S–7S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Office of Strategic Coordination. The Common Fund. [Internet]. Version current 14 June, 2019; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://commonfund.nih.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fairsharing. Standards, databases, policies. [Internet]. Version current 24 June, 2019; [cited 31 January 2019]. Available from: https://fairsharing.org. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sud M, Fahy E, Cotter D, Azam K, Vadivelu I, Burant C, Edison A, Fiehn O, Higashi R, Nair KS et al.. Metabolomics Workbench: an international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.