Abstract

Chimonanthus campanulatus R.H. Chang & C.S. Ding is a good horticultural tree because of its beautiful yellow flowers and evergreen leaves. In this study, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to analyse mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Ch. campanulatus with 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 oligonucleotides. Twenty-two small chromosomes were observed. Weak 5S rDNA signals were observed only in proximal regions of two chromosomes, which were adjacent to the (AG3T3)3 proximal signals. Weak (AG3T3)3 signals were observed on both chromosome ends, which enabled accurate chromosome counts. A pair of satellite bodies was observed. (AG3T3)3 signals displayed quite high diversity, changing in intensity from weak to very strong as follows: far away from the chromosome ends (satellites), ends, subtelomeric regions, and proximal regions. Ten high-quality spreads revealed metaphase dynamics from the beginning to the end and the transition to anaphase. Chromosomes gradually grew larger and thicker into linked chromatids, which grew more significantly in width than in length. Based on the combination of 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 signal patterns, ten chromosomes were exclusively distinguished, and the remaining twelve chromosomes were divided into two distinct groups. Our physical map, which can reproduce dynamic metaphase progression and distinguish chromosomes, will powerfully guide cytogenetic research on Chimonanthus and other trees.

Keywords: mitotic metaphase, satellite chromosome, physical map

1. Introduction

Fragrant species of Chimonanthus L. (Calycanthaceae) that are endemic to China and on The Plant List include six accepted taxa. Chimonanthus campanulatus R.H. Chang & C.S. Ding was established as a new species by Chang and Ding [1]. The Chimonanthus chromosome number (2n = 22) was first reported by Sugiura [2]. Ch. campanulatus has a 2n = 2x = 22 = 20 m (2SAT) + 2 sm karyotype [3]. The other five species, namely, Chimonanthus grammatus M.C. Liu, Chimonanthus nitens Oliv., Chimonanthus nitens var. salicifolius (S.Y. Hu) H.D. Zhang, Chimonanthus praecox (L.) Link, and Chimonanthus zhejiangensis M.C. Liu, all share a 2n = 2x = 22 = 20 m + 2 sm karyotype [3,4,5]. However, Ch. nitens also has a 2n = 2x = 22 = 18 m + 4 sm karyotype [4]. Among these six Chimonanthus species, Ch. campanulatus is the only one that possesses one pair of satellite chromosomes. However, one pair of satellite chromosomes was also observed in the same family (Calycanthaceae) but a different genus (Calycanthus): Calycanthus chinensis (W.C. Cheng & S.Y. Chang) P.T. Li, with a karyotype of 2n = 2x = 22 = 18 m + 2 m (SAT) + 2 sm [6], and Calycanthus occidentalis Hook. & Arn., with a karyotype of 2n = 22 = 20 m (2SAT) + 2 sm [7]. The genome size of Ch. campanulatus is unknown, but that of Ch. praecox is ~841 Mb [8]. In the same family (Calycanthaceae) but a different genus (Calycanthus), the species Calycanthus floridus L. shows a genome size of ~958 Mb [9] and a karyotype of 2n = 22 = 22 m [3]. Hence, genomic and chromosome information in Chimonanthus is rare and needs to be further sought.

Chen [10] studied the biosystematics of species in the genus Chimonanthus and inferred a close relationship between Ch. campanulatus and Ch. praecox. Dai [11] analysed the phylogeography, phylogeny and genetic diversity of species in the genus Chimonanthus by inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSRs), chloroplast DNA (trnL-F, trnS-G, and trnH-psbA), and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and speculated that current populations evolved independently in their respective refuges, e.g., Ch. campanulatus in Yunnan. Shu et al. [12] reviewed the non-volatile components and pharmacology of species in the genus Chimonanthus and found no reports on Ch. campanulatus. Similarly, other types of studies on Ch. campanulatus are also quite scarce.

To date, most studies of Chimonanthus have focused on Ch. praecox and Ch. nitens, while only a few studies have reported on Ch. nitens var. salicifolius, Ch. grammatus, and Ch. zhejiangensis. Studies on Ch. praecox have focused on transcriptomic and proteomic profiling throughout flower development [13,14,15,16]; fragrance gene identification [17]; floral scent emission from nectaries on the adaxial side of the innermost and middle petals [18]; separation and determination of volatile compounds [19,20], phenolic compounds [21], alkaloids and flavonoids [22,23,24], and sesquiterpenoids [25]; in vitro culture system development [26]; genetic linkage map construction [27]; simple sequence repeat (SSR) [28], expressed sequence tag (EST) [29], and amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) [30] development; and ANL2 [31], CpAGL2 [32], CpAP3 [33], CpCAF1 [34], CpCZF1/2 [35], Cpcor413pm1 [36], CpEXP1 [37], CpH3 [38], CpLEA5 [39], Cplectin [29], CpNAC8 [40], CpRALF [41], CpRBL [42], FPPS [43], and G6PDH1 [44] cloning and development. Studies on Ch. nitens have focused on its calycanthine, chimonanthine, coumarins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and volatile oils [45,46,47] and their pharmacologies (anti-inflammatory properties [48], antihyperglycaemic [49] and antihyperlipidaemic efficacies, and antioxidant capacity [50], inhibitory α-glucosidase activity [51], and toxicity [52]), phylogeography [45,53], and fingerprints [54,55]. Studies on Ch. nitens var. salicifolius have focused on leaf and flower transcriptome profiling [56], fingerprinting [57], sesquiterpenoids [21], nor-sesquiterpenoids [8], volatile oils and cineole [58], and the protective effect of leaves against 5-fluorouracil-induced gastrointestinal mucositis [54]. Studies on Ch. grammatus have focused on its β-sitosterol, quercetin, kaempferol, and isofaxidin [59] and essential oils [60]. Studies on Ch. zhejiangensis have focused only on its essential oils [61]. No related studies were found for Ch. campanulatus.

Since the number of studies on Ch. campanulatus is currently quite small, in this study, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to analyse mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Ch. campanulatus with the oligonucleotides 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3. The aim was to construct a physical map and distinguish the chromosomes of Ch. campanulatus, which will aid in molecular genetic map construction and pharmacological studies in Ch. campanulatus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chromosomes and Probe Preparation

Seeds of Ch. campanulatus R.H. Chang & C.S. Ding were collected from Chengdu Botanical Garden and germinated in wet sand at room temperature (15–25 °C). When the roots reached a length of 2 cm, the root tips were excised and immediately treated with nitrous oxide for four hours. Later, the root tips were transferred to 100% acetic acid for 5 min. Next, the meristems of the root tips were treated with cellulase and pectinase (1 mL buffer + 0.04 g cellulase + 0.02 g pectinase, the buffer 50 mL was included 0.5707 g trisodium citrate + 0.4324 g citric acid), which were produced by Yakult Pharmaceutical Ind. Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and Kyowa Chemical Products Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), and then placed into suspension for dropping onto slides. Finally, air-dried slides were examined using an Olympus CX23 microscope (Olympus, Japan), and high-quality spreads were further used in a follow-up experiment.

Two oligonucleotides, namely, 5S rDNA [62] and (AG3T3)3 [63], were used in this study. The probes were synthesized by Sangon Biotechnology Limited Corporation (Shanghai, China), and their 5′ ends were labelled by carboxyfluorescein (FAM) or carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). The synthetic probes were dissolved in ddH2O and maintained at a concentration of 10 μM.

2.2. Hybridization and Image Capture

Hybridization was performed as previously described by Luo et al. [62]. High-quality spreads on slides were each subjected to a series of fixation (4% paraformaldehyde), dehydration (75%, 95%, 100% ethanol), degeneration (Deionized formamide, 80 °C), and a second dehydration (−20 °C), added to 10 μL of hybridization mixture [0.325 μL of 5S rDNA, 0.325 μL of (AG3T3)3, 4.675 μL of 2× SSC, and 4.675 μL of ddH2O], and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, hybridized chromosomes were washed with 2× SSC and ddH2O twice for 5 min at room temperature, air-dried, and counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA).

The slides were examined by an Olympus BX63 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Photometric SenSys Olympus DP70 CCD camera (Olympus, Japan). Approximately 60 metaphases from ten slides of ten Ch. campanulatus root tips were observed in this study. Greater than 30 metaphases in which the chromosomes were well separated were selected to count the chromosome number. Ten better spreads were used for karyotype analysis. Single chromosomes were isolated using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, USA), and each spread was measured three times to provide consistent karyotype data. Chromosomes in the physical maps were aligned based on length and signal patterns. Karyotype idiograms were constructed in Excel 2019 and PowerPoint 2019 based on the relative chromosome lengths.

3. Results

3.1. S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 Enabled Visualization of Ch. Campanulatus Chromosomes

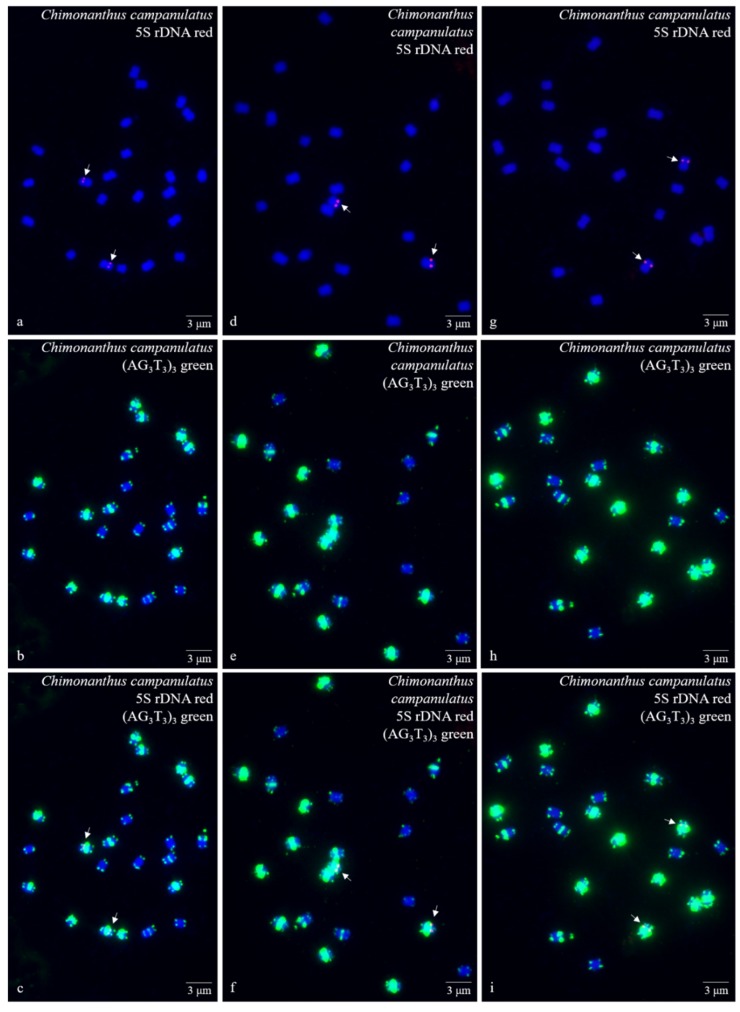

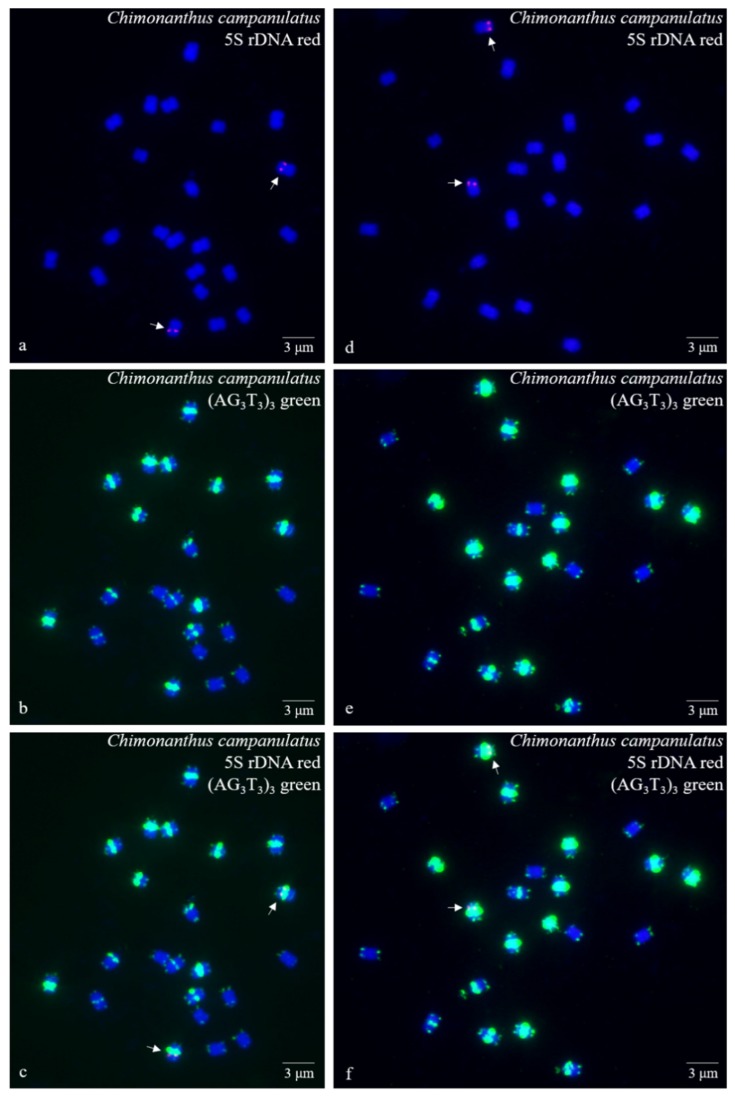

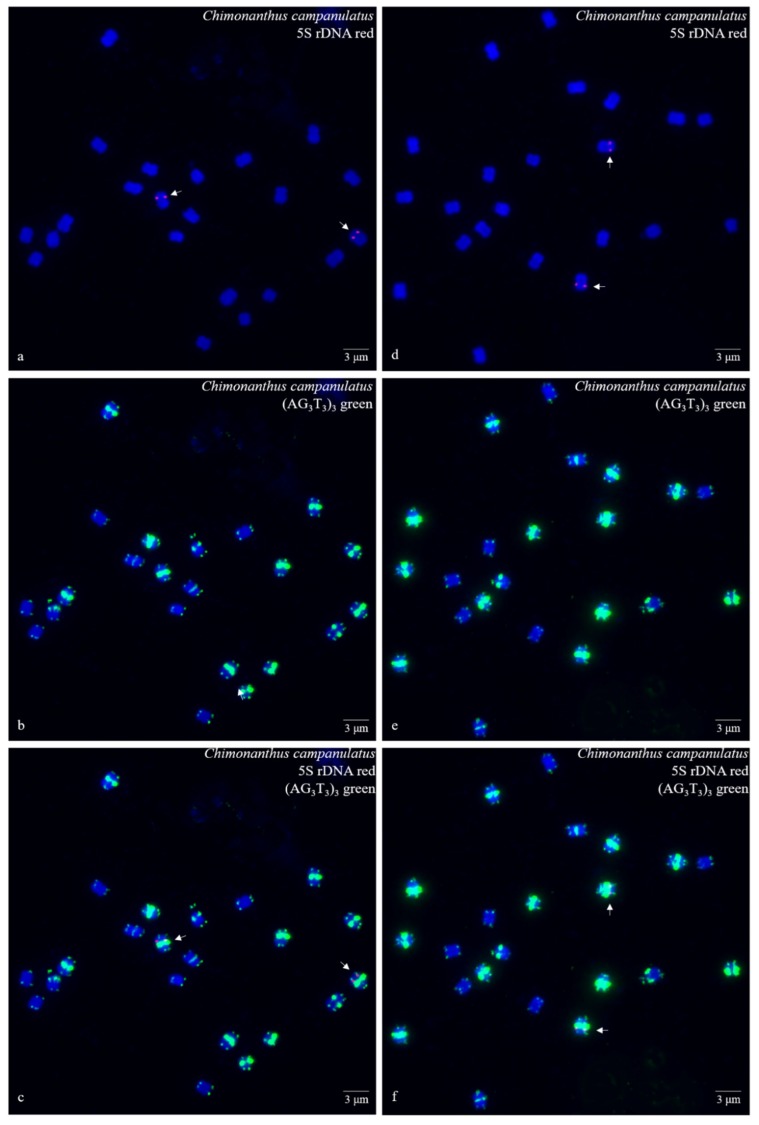

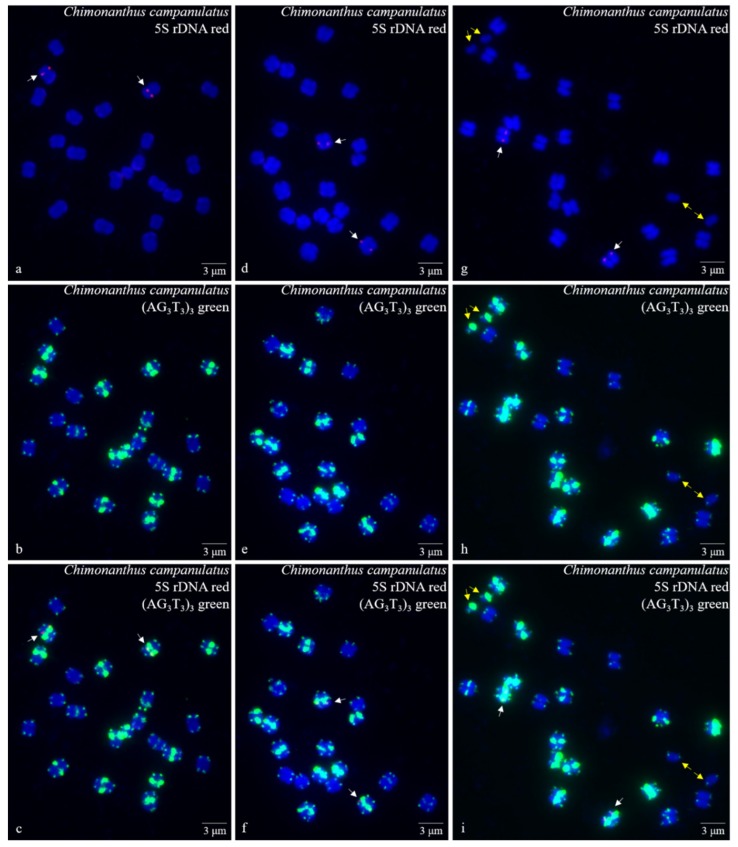

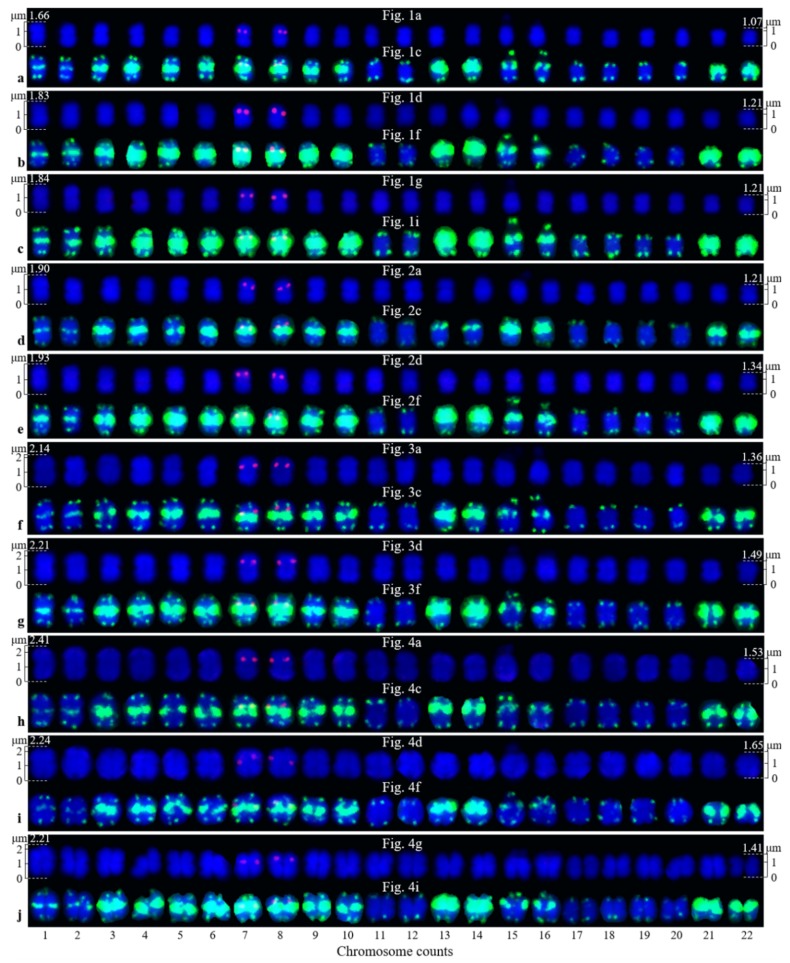

Ten high-quality spreads of mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Ch. campanulatus after FISH are illustrated in Figure 1 (preliminary stage), Figure 2 (development stage), Figure 3 (further development stage), and Figure 4 (final stage in Figure 4a–f, end of metaphase to beginning of anaphase in Figure 4g–i), which exhibited dynamic metaphase progression from the preliminary stage to the final metaphase and confirmed the repeatability and stability of our FISH results. In total, twenty-two chromosomes were counted in each spread except the last spread, as shown in Figure 4g–i (twenty-four chromosomes). In the last spread, chromosomes were at the end of metaphase to the beginning of anaphase, with twenty chromosomes were preparing to split (chromatids) and two chromosomes had already split into four chromosomes (yellow arrows in Figure 4g–i). To better describe the chromosome characteristics, a single chromosome was isolated from Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 and illustrated in Figure 5. Chromosomes of each spread were aligned by their length from longest (chromosome 1) to shortest (chromosome 22) and their signal patterns. The four split chromosomes were assembled into two chromosomes (17 and 22) based on their signal patterns (Figure 5). Hence, all ten spreads showed 22 chromosomes.

Figure 1.

Mitotic metaphase (preliminary stage) chromosomes of Chimonanthus campanulatus R.H. Chang & C.S. Ding after fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Three spreads are presented in Figure 1a–c, Figure 1d–f, and Figure 1g–i. The probe oligo–5S rDNA result with chromosomes visualized by carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) (red, white arrows) is shown in Figure 1a,c,d,f,g,i, whereas the probe oligo–(AG3T3)3 result with chromosomes visualized by carboxyfluorescein (FAM) (green) is shown in Figure 1b,c,e,f,h,i. Chromosomes were counterstained by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) in all images. Scale bar = 3 μM.

Figure 2.

Mitotic metaphase (development stage) chromosomes of Chimonanthus campanulatus after FISH. Two spreads are presented in Figure 2a–c and Figure 2d–f. The probe oligo–5S rDNA result with chromosomes visualized by TAMRA (red, white arrows) is shown in Figure 2a,c,d,f, whereas the probe oligo–(AG3T3)3 result with chromosomes visualized by FAM (green) is shown in Figure 2b,c,e,f. Chromosomes were counterstained by DAPI (blue) in all images. Scale bar = 3 μM.

Figure 3.

Mitotic metaphase (further development stage) chromosomes of Chimonanthus campanulatus after FISH. Two spreads are presented in Figure 3a–c and Figure 3d–f. The probe oligo-5S rDNA result with chromosomes visualized by TAMRA (red, white arrows) is shown in Figure 3a,c,d,f, whereas the probe oligo–(AG3T3)3 result with chromosomes visualized by FAM (green) is shown in Figure 3b,c,e,f. Chromosomes were counterstained by DAPI (blue) in all images. Scale bar = 3 μM.

Figure 4.

Mitotic metaphase (final stage in Figure 4a–f, end of metaphase to beginning of anaphase in Figure 4g–i) chromosomes of Chimonanthus campanulatus after FISH. Three spreads are presented in Figure 4a–c, Figure 4d–f, and Figure 4g–i. The probe oligo–5S rDNA result with chromosomes visualized by TAMRA (red, white arrows) is shown in Figure 4a,c,d,f,g,i, whereas the probe oligo–(AG3T3)3 result with chromosomes visualized by FAM (green) is shown in Figure 4b,c,e,f,h,i. Two chromosomes have split into four chromosomes in Figure 4g–i (yellow arrows), and 20 chromosomes are preparing to split, which shows that this spread was at the end of metaphase to beginning of anaphase. Chromosomes were counterstained by DAPI (blue) in all images. Scale bar = 3 μM.

Figure 5.

Each chromosome of Chimonanthus campanulatus isolated from Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. For example, the chromosomes in Figure 5a were isolated from Figure 1a and Figure 1c, as indicated in the middle of each chromosome line. Because the (AG3T3)3 end signals likely affect the measurement of chromosome length, only the first and last chromosomes in Figure 1a,d,g, Figure 2a,d, Figure 3a,d, Figure 4a,d,g were measured for total length. The chromosomes were aligned based on length. The bottom numbers indicate chromosome counts. The four split chromosomes in Figure 4g,i (yellow arrows) were assembled into two chromosomes (17 and 22) based on their signal patterns.

Figure 5 also shows the lengths of the longest (1) and shortest chromosomes (22) in the ten Ch. campanulatus spreads originally shown in Figure 1a,d,g, Figure 2a,d, Figure 3a,d, and Figure 4a,d,g, with the lengths ranging from 1.66–1.07 μM, 1.83–1.21 μM, 1.84–1.21 μM, 1.90–1.21 μM, 1.93–1.34 μM, 2.14–1.36 μM, 2.21–1.49 μM, 2.41–1.53 μM, 2.24–1.65 μM, and 2.21–1.41 μM, respectively. There was a very significant difference in chromosome length among these ten spreads (p = 0.00019), revealing dynamic chromosome growth in terms of length from the preliminary stage to the end of metaphase. The longest chromosome was 2.41 μM long, i.e., still less than 3 μM; hence, all of the chromosomes were small chromosomes. Due to the small size and unclear centromere locations of the chromosomes, it was difficult to determine the long arms and short arms, and karyotype analysis was not performed further.

Figure 5 further displays a conserved 5S rDNA signal distribution and a diverse (AG3T3)3 signal distribution for Ch. campanulatus. Weak 5S rDNA signals were observed only in proximal regions of two chromosomes (7/8) (red colour in Figure 1a,c,d,f,g,i, Figure 2a,c,d,f, Figure 3a,c,d,f, Figure 4a,c,d,f,g,i, and Figure 5), which were adjacent to the (AG3T3)3 proximal signals on these two chromosomes. Weak (AG3T3)3 signals were observed on both chromosome ends (green colour in Figure 1b,c,e,f,h,i, Figure 2b,c,e,f, Figure 3b,c,e,f, Figure 4b,c,e,f,h,i, and Figure 5), which ensured accurate chromosome counts. Weak (AG3T3)3 signals were also observed in the proximal regions of two chromosomes (1/2), and strong (AG3T3)3 signals were observed in the proximal regions of two chromosomes (15/16). Interestingly, a pair of satellite bodies was observed on chromosomes 15/16, as shown by the upper-chromosome end (AG3T3)3 signals located far away from the established ends of the two chromosomes (15/16). Meanwhile, very strong (AG3T3)3 signals were observed in the proximal regions of eight chromosomes (3/4/5/6/7/8/9/10) and in the subtelomeric regions of four chromosomes (13/14/21/22). Finally, almost no (AG3T3)3 signals were observed in the proximal regions of six chromosomes (11/12/17/18/19/20).

3.2. Physical Map Reproduced Metaphase Dynamics and Distinguished Chromosomes

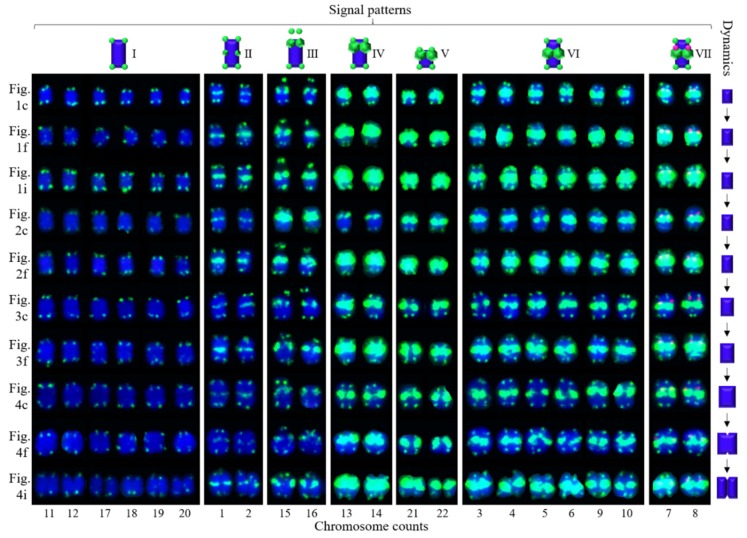

To better describe the chromosomes of Ch. campanulatus, the chromosome hybridizations with 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 shown in Figure 5 were separated to create Figure 6. The metaphase dynamic idiograms on the right were constructed based on the metaphase dynamics of chromosomes on the left. Although this dynamic metaphase progression is not a novel mitotic phenomenon, it still provides the first visualization of the dynamic metaphase progression of Ch. campanulatus, from the preliminary stage to the end of metaphase and from single-chromosome duplication to the linkage or splitting of chromosomes. In addition, obvious satellite bodies gradually moved from far away from the arm ends to close to the arm ends from the beginning to the end of metaphase.

Figure 6.

Physical map of Chimonanthus campanulatus. Each chromosome was isolated from Figure 5. The left indicates the origins of each line of chromosomes. The right metaphase dynamic ideograms were constructed based on the metaphase dynamics of chromosomes shown on the left. The signal pattern ideograms at the top were constructed based on the signal patterns of chromosomes. The numbers at the bottom indicate chromosome counts. Chromosomes 15 and 16 are SAT chromosomes.

Furthermore, idiograms of the seven types of 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 signal patterns observed for Ch. campanulatus chromosomes (top of Figure 6) were constructed: Type I: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends were observed for six chromosomes (11/12/17/18/19/20). Type II: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends and in the proximal regions were observed for two chromosomes (1/2). Type III: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends and strong (AG3T3)3 signals in the distal regions were observed for two chromosomes (15/16). A peculiar phenomenon was observed for these two chromosomes: Satellite bodies were shown by upper-end signals located far away from the designated chromosome ends. Type IV: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends and very strong (AG3T3)3 signals in the subtelomeric regions (adjacent to the end signals) were observed for two chromosomes (13/14). Type V: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends and very strong (AG3T3)3 signals in the subtelomeric regions (adjacent to the end signals) were observed for the two shortest chromosomes (21/22). Type VI: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends and very strong (AG3T3)3 signals in the proximal regions were observed for six chromosomes (3/4/5/6/9/10). Type VII: Weak (AG3T3)3 signals on both chromosome ends and very strong (AG3T3)3 signals in the proximal regions, as well as 5S rDNA signals adjacent to proximal (AG3T3)3 signals, were observed for two chromosomes (7/8). In contrast to types I and VI, which included six chromosomes, types II, III, IV, V, and VII each included only two chromosomes. Therefore, 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 signal patterns exclusively distinguished ten chromosomes, namely, 1/2/7/8/13/14/15/16/21/22, and divided the other twelve chromosomes into two obvious groups, namely, 3/4/5/6/9/10 and 11/12/17/18/19/20. The physical map of Ch. campanulatus convincingly demonstrated that (AG3T3)3 not only labelled chromosome ends (including satellite bodies), which are used to count chromosome numbers, but also labelled chromosome proximal regions and subtelomeric regions with obviously different signal intensities, which are used as effective FISH markers for cytogenetic analysis.

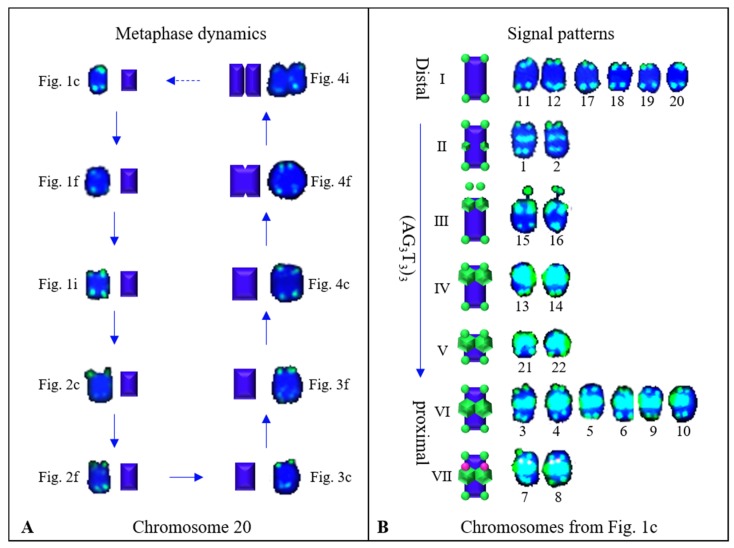

In summary, Figure 7 shows the refined metaphase dynamics and signal patterns of Ch. campanulatus chromosomes isolated from Figure 6. Chromosome 20, represented by ten spreads (visualized in Figure 1c,f,i, Figure 2c,f, Figure 3c,f, Figure 4c,f,i), presented dynamic metaphase progression from the beginning to the end. Chromosomes gradually grew larger and wider to form linked chromatids, which grew more significantly in width than in length (Figure 7A). The chromosomes shown in Figure 1c exhibited seven types of signal patterns. The intensity of (AG3T3)3 signals showed quite high diversity, ranging from weak to very strong as follows: far away from the ends (satellite bodies), ends, subtelomeric regions, and proximal regions (Figure 7B). Based on a combination of 5S rDNA and (AG3T3)3 signal patterns, ten chromosomes were exclusively distinguished, and the remaining twelve chromosomes were divided into two obvious groups. In the future, we will explore more oligonucleotides to discern the twelve chromosomes categorized as types I and VII.

Figure 7.

Dynamic metaphase progression and signal patterns of Chimonanthus campanulatus chromosomes isolated from Figure 6. The left panel (Figure 7A) shows chromosome 20 in ten spreads to present metaphase dynamics (Figure 1c,f,i, Figure 2c,f, Figure 3c,f, Figure 4c,f,i). The right panel (Figure 7B) uses the 22 chromosomes in Figure 1c to demonstrate signal patterns. The signal intensity of the distal repeat probe (AG3T3)3 was variable, ranging from weak on the chromosome ends to strong in the proximal regions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Karyotype Analysis and Dynamic Metaphase Progression

Ten high-quality spreads displayed a very significant difference in chromosome length, which revealed chromosome dynamic growth in terms of length from the preliminary stage to the end of metaphase and transition to anaphase. The corresponding physical map of chromosomes reproduced the dynamic mitotic metaphase progression in Ch. campanulatus for the first time. Similarly, Matsui [64] examined dynamic changes in proteins during mitotic metaphase, anaphase, and telophase in human epithelial HeLa S3 cell populations to reproduce dynamic mitotic progression. The length of Ch. campanulatus chromosomes was 1.07–2.41 μM in this study. In previous works, chromosome lengths were reported to be 1.05–1.81 μM in Ligustrum lucidum Lindl. [65], 1.12–2.06 μM in Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh. [65], 1.22–2.11 μM in Fragaria nilgerrensis Schlecht. ex Gay [66], 1.23–2.34 μM in Zanthoxylum armatum Candelle [67], 1.25–2.83 μM in Ligustrum × vicaryi Rehder [65], 1.48–2.08 μM in Fragaria vesca L. [66], 1.50–2.32 μM in Syringa oblata Ait. [65], 1–4 μM in Rubus L. species [68], 1.82–2.75 μM in Berberis diaphana Maxim. [69], 4.03–7.21 μM in Piptanthus concolor Harrow ex Craib [62], 4–13 μM in Avena sativa L. [70], and 9–13 μM in Triticum aestivum L. ‘Chinese Spring’ [71]. In our unpublished works, chromosome lengths were recorded to be 0.97–2.16 μM in Juglans regia L., 0.98–2.65 μM in Juglans sigillata Dode, 1.13–2.41 μM in Firmiana platanifolia (L. f.) Marsili, 1.12–2.49 μM in Koelreuteria bipinnata Franch., 1.31–1.43 μM in Robinia pseudoacacia L., 1.44–5.28 μM in Podocarpus macrophyllus (Thunb.) D. Don, 1.75–2.23 μM in Erythrina crista-galli L., 2.05-3.70 μM in Croton tiglium L., 2.16–4.96 μM in Quercus aquifolioides Rehd. et Wils., and 8.73–14.35 μM in Cycas revoluta Thunb. The length of the longest chromosome in Ch. campanulatus was approximately equal to that in Z. armatum (2.34 μM), while the length of the shortest chromosome in Ch. campanulatus was approximately equal to that in L. lucidum (1.05 μM).

In this study, twenty-two chromosomes were observed in Ch. campanulatus, which was in agreement with the numbers reported in previous works [2,3]. Similar to the results from Liu et al. [3], one pair of satellite chromosomes was clearly observed in this study. Satellite bodies, as hereditary features, may be used to distinguish species [72,73]. The other five species in the genus Chimonanthus (Ch. grammatus, Ch. nitens, Ch. nitens var. salicifolius, Ch. praecox, and Ch. zhejiangensis) do not possess satellite bodies, based on the findings of previous works [3,4,5], revealing relatively distant relationships between Ch. campanulatus and the other five Chimonanthus species. However, in the same family (Calycanthaceae) but a different genus (Calycanthus), the species Ca. chinensis and Ca. occidentalis possess one pair of satellite chromosomes and twenty-two chromosomes [6,7], indicating moderately close relationships between these two species and Ch. campanulatus.

4.2. Distinguishing Ch. campanulatus chromosomes

No FISH technology has been previously applied in Chimonanthus species. Here, (AG3T3)3 and 5S rDNA were tested in Ch. campanulatus for the first time. In contrast to 5S rDNA, (AG3T3)3 generally labels only chromosome ends, rendering it a less effective FISH marker for distinguishing chromosomes [65,69,74]. However, in this study, (AG3T3)3 was an excellent marker because it distinguished Ch. campanulatus chromosomes based on its location: far away from chromosome ends (satellite bodies), ends, subtelomeric regions and proximal regions; in this order, its intensity ranged from weak to strong and very strong. Such high diversity in (AG3T3)3 signal intensity has rarely been found in other species, but this oligonucleotide was found to locate to the proximal region of chromosomes in Zea mays L. [63], Podocarpus L. Her. ex Persoon species [75], and Philodendron Schott species [76].

In this study, (AG3T3)3 labelling of satellite bodies in Ch. campanulatus was reported for the first time. Satellite bodies of B. diaphana are a quarter of the chromosome size (~0.6 μM) and are labelled at the ends by (AG3T3)3 [69]. Satellite bodies are often connected to the main body of the chromosome by very lightly staining strands [72]. These bodies vary in size according to the position of the secondary constriction. If the secondary constriction is very close to an end of the chromosome, the satellite may be a barely perceptible dot [73]. In this study, the satellite bodies were small, barely perceptible dots (~0.1 μM) located far away from their designated ends and were obvious based on their green (AG3T3)3 signals. Hence, (AG3T3)3 may aid in the visualization of such unobservable satellite bodies.

The 5S rDNA in this study was quite conserved, located only adjacent to (AG3T3)3 proximal regions on two chromosomes. Similarly, 5S rDNA distinguished two chromosomes in B. diaphana [69] and C. tiglium, C. revoluta, E. crista-galli, J. regia, J. sigillata, K. bipinnata, Q. aquifolioides and P. macrophyllus (unpublished data); four chromosomes in Berberis soulieana [69], F. pennsylvanica [65], Z. armatum [67], and L. baviensis (unpublished data); six chromosomes in L. lucidum and L. × vicaryi [65] and L. elongata and R. pseudoacacia (unpublished data); and eight chromosomes in S. oblata [65] and F. platanifolia (unpublished data). In contrast, 5S rDNA displayed quite high diversity and distinguished sixteen chromosomes in P. concolor [62]. Therefore, (AG3T3)3 and 5S rDNA both have the potential to effectively discern chromosomes as FISH markers.

5. Conclusions

In this study, based on the combination of (AG3T3)3 and 5S rDNA signal patterns, only ten chromosomes were exclusively discerned among the twenty-two chromosomes of Ch. campanulatus. The remaining twelve chromosomes were divided into two obvious groups. It is necessary to explore more oligonucleotide probes to further distinguish Ch. campanulatus chromosomes and establish detailed physical maps.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhou Yonghong for laboratory equipment support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; methodology, J.C.; software, J.C.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, X.L.; investigation, J.C.; resources, X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors consented to this submission.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 31500993).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Chang R.H., Ding C.C. The seedling characters of Chinese Calycanthaceae with a new species of Chimonanthus Lindl. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Sci. 1980 18:328–332. Available online: http://journal.ucas.ac.cn/EN/Y1980/V18/I3/328. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugiura T. A list of chromosome numbers in angiospermous plants. Bot. Mag. Tokyo. 1931;45:353. doi: 10.15281/jplantres1887.45.353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu H.E., Zhang R.H., Huang S.F., Zhao Z.F. Study on Chromosomes of 8 Species of Calycathaceae. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];J. Zhejiang For. Coll. 1996 13:28–33. Available online: http://europepmc.org/abstract/CBA/288874. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song X.C., Liu Y.X., Jiang X.M. Analysis of chromosome karotype of Chimonanthus nitens and Chimonanthus zhejiangensis. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Jiangxi For. Sci. Technol. 2013 2:10–12. Available online: http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=45635921. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Y.C., Xiang Q.Y. Cytological studies on some plants of East China. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 1987 25:1–8. Available online: http://www.plantsystematics.com/CN/Y1987/V25/I1/145635921. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L.C. Karyotype analysis on Calycanthus chinensis. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Guihaia. 1986 6:221–224. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=cjfd1986&filename=gxzw198603011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L.C. Cytogeographical study of Calycanthus Linneus. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Guihaia. 1989 4:311–316. Available online: http://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=41148. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L., Cao B., Bai C. New reports of nuclear DNA content for 66 traditional Chinese medicinal plant taxa in China. Caryologia. 2013;66:375–383. doi: 10.1080/00087114.2013.859443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridley J.D., Craddock A. Contrasting growth phenology of native and invasive forest shrubs mediated by genome size. New Phytol. 2015;207:659–668. doi: 10.1111/nph.13384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L.Q. Biological studies on the genus Chimonanthus Lindley. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Beijing For. Univ. 1998 Available online: http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y280512. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai P.F. Phylogeography, phylogeny and genetic diversity studies on Chimonanthus Lindley. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Northwest Univ. 2012 Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFD2013&filename=1013136315.nh. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shu R.G., Wan Y.L., Wang X.M. Non-Volatile constituents and pharmacology of Chimonanthus: A review. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2019;17:161–186. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(19)30020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu D., Sui S., Ma J., Li Z., Guo Y., Luo D., Yang J., Li M. Transcriptomic analysis of flower development in wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox) PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z., Jiang Y., Liu D., Ma J., Li J., Li M., Sui S. Floral scent emission from nectaries in the adaxial side of the innermost and middle petals in Chimonanthus praecox. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3278. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian J.P., Ma Z.Y., Zhao K.G., Zhang J., Xiang L., Chen L.Q. Transcriptomic and proteomic approaches to explore the differences in monoterpene and benzenoid biosynthesis between scented and unscented genotypes of wintersweet. Physiol. Plant. 2019;166:478–493. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang N., Zhao K., Li X., Zhao R., Aslam M.Z., Yu L., Chen L. Comprehensive analysis of wintersweet flower reveals key structural genes involved in flavonoid biosynthetic pathway. Gene. 2018;676:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baral A. Finding the fragrance genes of wintersweet. Physiol. Plant. 2019;166:475–477. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L. Morphological comparison flower bud differentiation and development of four species in Calycanthaceae. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2018 Available online: http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?type=degree&id=Y3396525. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng C., Song G., Hu Y. Rapid determination of volatile compounds emitted from Chimonanthus praecox flowers by HS-SPME-GC-MS. Z. Nat. C. 2004;59:636–640. doi: 10.1515/znc-2004-9-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lv J.S., Zhang L.L., Chu X.Z., Zhou J.F. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the extracts of the flowers of the Chinese plant Chimonanthus praecox. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012;26:1363–1367. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2011.602828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H., Zhang Y., Liu Q., Sun C., Li J., Yang P., Wang X. Preparative separation of phenolic compounds from Chimonanthus praecox flowers by high-speed counter-current chromatography using a stepwise elution mode. Molecules. 2016;21:1016. doi: 10.3390/molecules21081016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J.W., Gao J.M., Xu T., Zhang X.C., Ma Y.T., Jarussophon S., Konishi Y. Antifungal activity of alkaloids from the seeds of Chimonanthus praecox. Chem. Biodivers. 2009;6:838–845. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morikawa T., Nakanishi Y., Ninomiya K., Matsuda H., Nakashima S., Miki H., Miyashita Y., Yoshikawa M., Hayakawa T., Muraoka O. Dimeric pyrrolidinoindoline-type alkaloids with melanogenesis inhibitory activity in flower buds of Chimonanthus praecox. J. Nat. Med. 2014;68:539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11418-014-0832-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitagawa N., Ninomiya K., Okugawa S., Motaia C., Nakanishi Y., Yoshikawa M., Muraoka O., Morikawa T. Quantitative determination of principal alkaloid and flavonoid constituents in wintersweet, the flower buds of Chimonanthus praecox. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016;11:953–956. doi: 10.1177/1934578X1601100721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lou H.Y., Zhang Y., Ma X.P., Jiang S., Wang X.P., Yi P., Liang G.Y., Wu H.M., Feng J., Jin F.Y., et al. Novel sesquiterpenoids isolated from Chimonanthus praecox and their antibacterial activities. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2018;16:621–627. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(18)30100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng J. In vitro culture and optimization genetic transformation system of Calycanthus praecox. Southwest Univ. 2007 doi: 10.7666/d.y1075121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen D.W. Wintersweet in vitro culture and genetic map construct. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2010 Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFDTEMP&filename=2010271821.nh. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y.X. Wintersweet two moecular marker develop and F1 population segregation evaluation. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2014 doi: 10.7666/d.Y2565460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sui S., Luo J., Ma J., Zhu Q., Lei X., Li M. Generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from Chimonanthus praecox (Wintersweet) flowers for discovering stress-responsive and floral development-related genes. Comp. Funct. Genom. 2012;2012:134596. doi: 10.1155/2012/134596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou M.Q. Molecular marker analysis germplasm of Calycanthus praecox and genetic diversity of Chimonanthus nitens. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2007 doi: 10.7666/d.y1812620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao S.P. Calycanthus praecox ANL2 cloning and function identification. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2015 doi: 10.7666/d.Y2803395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo D.P. Chimonanthus praecox (L.) link CpAGL2 cloning and function identification. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Southwest Univ. 2014 Available online: http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y2572451. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Q., Wang B.G., Duan K., Wang L.G., Wang M., Tang X.M., Pan. A.H., Sui S.Z., Wang G.D. The paleoAP3-type gene CpAP3, an ancestral B-class gene from the basal angiosperm Chimonanthus praecox, can affect stamen and petal development in higher eudicots. Dev. Genes Evol. 2011;221:83–93. doi: 10.1007/s00427-011-0361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou S.Q. Calycanthus praecox CpCAF1 cloning and function identification. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Southwest Univ. 2016 Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?filename=1016767365.nh&dbname=CMFDTEMP. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H., Huang R., Ma J., Sui S., Guo Y., Liu D., Li Z., Lin Y., Li M. Two C3H type zinc finger protein genes, CpCZF1 and CpCZF2, from Chimonanthus praecox affect stamen development in Arabidopsis. Genes. 2017;8:199. doi: 10.3390/genes8080199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin M. Chimonanthus praecox Cpcor413pm1 stress resistance and subcellular localization. Southwest Univ. 2008 doi: 10.7666/d.y1262258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Z. Calycanthus praecox CpEXP1 expression and function identification. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Southwest Univ. 2014 Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CDFD&dbname=CDFDTEMP&filename=1015547733.nh. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang H.Y. Calycanthus praecox CpH3 cloning and function identification. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Southwest Univ. 2013 Available online: http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?type=degree&id=Y2309710#. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y., Xie L., Liang X., Zhang S. CpLEA5, the late embryogenesis abundant protein gene from Chimonanthus praecox, possesses low temperature and osmotic resistances in prokaryote and eukaryotes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:26978–26990. doi: 10.3390/ijms161126006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y. Wintersweet CpNAC8 cloning and function identification. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Southwest Univ. 2017 Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?filename=1017847224.nh&dbname=CMFDTEMP. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang B. Calycanthus praecox CpRALF cloning and function identification. Southwest Univ. 2012 doi: 10.7666/d.y2085948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y. Calycanthus praecox CpRBL cloning and function identification. [(accessed on 15 October 2019)];Southwest Univ. 2012 Available online: http://www.wan.fangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y2309707. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiang L., Zhao K., Chen L. Molecular cloning and expression of Chimonanthus praecox farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase gene and its possible involvement in the biosynthesis of floral volatile sesquiterpenoids. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010;48:845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X.H., Liu X., Gao B.W., Zhang Z.X., Shi S.P., Tu P.F. Cloning and expression analysis of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 (G6PDH1) gene from Chimonanthus praecox. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2015;40:4160–4164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang W.P., Tan T., Li Z.F., OuYang H., Xu X., Zhou B., Feng Y.L. Structural characterization and discrimination of Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. leaf from different geographical origins based on multiple chromatographic analysis combined with chemometric methods. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;154:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan T., Luo Y., Zhong C.C., Xu X., Feng Y. Comprehensive profiling and characterization of coumarins from roots, stems, leaves, branches, and seeds of Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. using ultra-performance liquid chromatography/quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry combined with modified mass defect filter. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017;141:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao Y., Huang Z.X., Shu R.G., Wan Y.L., Zhang M. Studies on chemical component of leaves in Chimonanthus nitens (II) Zhong Yao Cai. 2019;42:100–102. doi: 10.13863/j.issn1001-4454.2019.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun Q., Zhu J., Cao F., Chen F. Anti-Inflammatory properties of extracts from Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. leaf. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0181094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen H., Xiong L., Wang N., Liu X., Hu W., Yang Z., Jiang Y., Zheng G., Ouyang K., Wang W. Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. leaf extract exerting anti-hyperglycemic activity by modulating GLUT4 and GLUT1 in the skeletal muscle of a diabetic mouse model. Food Funct. 2018;9:4959–4967. doi: 10.1039/C8FO00954F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen H., Jiang Y., Yang Z., Hu W., Xiong L., Wang N., Liu X., Zheng G., Ouyang K., Wang W. Effects of Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. leaf extract on glycolipid metabolism and antioxidant capacity in diabetic model mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017;2017:7648505. doi: 10.1155/2017/7648505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen H., Ouyang K., Jiang Y., Yang Z., Hu W., Xiong L., Wang N., Liu X., Wang W. Constituent analysis of the ethanol extracts of Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. leaves and their inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;98:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li S., Zou Z. Toxicity of Chimonanthus nitens flower extracts to the golden apple snail, Pomacea canaliculata. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019;160:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang Z. Primarly studies on phylogeography of Chimonanthus nitens Oliv. complex (Calycanthaceae) Nanchang Univ. 2014 doi: 10.7666/d.D554419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu H.T., Cao M.P., Zhang X.F., Si J.P. HPLC fingerprints establishment of chemical constituents in genus Chimonanthus leaves. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2013;38:1560–1563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou B., Tan M., Lu J.F., Zhao J., Xie A.F., Li S.P. Simultaneous determination of five active compounds in chimonanthus nitens by double-development HPTLC and scanning densitometry. Chem. Cent. J. 2012;6:46. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-6-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qian Z., Zhang S.J., Jin Y.Q., Zhang X.F. Transcriptome sequencing of leaves and flowers and screening and expression of differential genes in aroma synthesis in Chimonanthus salicifolius. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019;5:844–855. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7968.2019.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang X., Zhao C., Su W. A fast and reliable UPLC-PAD fingerprint analysis of Chimonanthus salicifolius combined with chemometrics methods. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2016;54:1213–1219. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmw053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu Y.F., Lv G.Y., Zhang Z.R., Yu J.J., Yan M.Q., Chen S.H. The influence of storage time on content of volatile oil and cineole of Chimonanthus salicifolius. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2013;38:2803–2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ling Q. studies on chemical composition and bioactivity of leaf in Chimonanthus grammatus. Jiangxi Norm. Univ. 2014 doi: 10.7666/d.Y2660956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu Y., Yan R., Lu S., Zhang Z., Zou Z., Zhu D. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from leaves of Chimonanthus grammatus. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2011;36:3149–3154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ouyang T., Mai X. Analysis of the chemical constituents of essential oil from Chimonanthus zhejiangensis by GC-MS. Zhong Yao Cai. 2010;33:385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luo X., Liu J., Zhao A., Chen X., Wan W., Chen L. Karyotype analysis of Piptanthus concolor based on FISH with an oligonucleotide for rDNA 5S. Sci. Hortic. 2017;226:361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qi Z.X., Zeng H., Li X.L., Chen C.B., Song W.Q., Chen R.Y. The molecular characterization of maize B chromosome specific AFLPs. Cell Res. 2002;12:63–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsui Y., Nakayama Y., Okamoto M., Fukumoto Y., Yamaguchi N. Enrichment of cell populations in metaphase, anaphase, and telophase by synchronization using nocodazole and blebbistatin: A novel method suitable for examining dynamic changes in proteins during mitotic progression. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012;91:413–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luo X.M., Liu J.C. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of the locations of the oligonucleotides 5S rDNA, (AGGGTTT)3, and (TTG)6 in three genera of Oleaceae and their phylogenetic framework. Genes. 2019;10:375. doi: 10.3390/genes10050375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rho R.I., Hwang Y.J., Lee H.I., Lee C.H., Lim K.B. Karyotype analysis using FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) in Fragaria. Sci. Hortic. 2012;136:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2011.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luo X.M., Liu J.C., Wang J.Y., Gong W., Chen L., Wan W.L. FISH analysis of Zanthoxylum armatum based on oligonucleotides for 5S rDNA and (GAA)6. Genome. 2018;61:699–702. doi: 10.1139/gen-2018-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y., Wang X., Chen Q., Zhang L., Tang H., Luo Y. Phylogenetic insight into subgenera Idaeobatus and Malachobatus (Rubus, Rosaceae) inferring from ISH analysis. Mol. Cytogenet. 2015;8:11–13. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu J., Luo X. First report of bicolour FISH of Berberis diaphana and B. soulieana reveals interspecific dierences and co-localization of (AGGGTTT)3 and rDNA 5S in B. diaphana. Hereditas. 2019;156:13–21. doi: 10.1186/s41065-019-0088-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luo X., Tinker N.A., Zhou Y., Wight P.C., Wan W., Chen L., Peng Y. Genomic relationships among sixteen Avena taxa based on (ACT)6 trinucleotide repeat FISH. Genome. 2018;61:63–70. doi: 10.1139/gen-2017-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cuadrado A., Cardoso M., Jouve N. Increasing the physical markers of wheat chromosomes using SSRs as FISH probes. Genome. 2008;51:809–815. doi: 10.1139/G08-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nebel B.R. Chromosome Structure. Bot. Rev. 1939;5:563–626. doi: 10.1007/BF02870166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ris H., Kubai D.F. Chromosome Structure. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1970;4:263–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.04.120170.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deng H.H., Xiang S.Q., Guo Q.G., Jin W.W., Liang G.L. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of genome-specific repetitive elements in Citrus clementina Hort. Ex Tan. and its taxonomic implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:77–88. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1676-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murray B.G., Friesen N., Heslop-Harrison J.S. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of Podocarpus and comparison with other gymnosperm species. Ann. Bot. 2002;89:483–489. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vasconcelos E.V., Vasconcelos S., Ribeiro T., Benko-Iseppon A.M., Brasileiro-Vidal A.C. Karyotype heterogeneity in Philodendron s.l. (Araceae) revealed by chromosome mapping of rDNA loci. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0207318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]