Abstract

Low and middle income countries (LAMIC) lack the research infrastructure and capacity necessary for the implementation of rigorous substance abuse and mental health effectiveness clinical trials that could guide clinical practice. A partnership between the Florida Node Alliance of the US National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network and Mexico’s National Institute of Psychiatry was established to improve substance abuse practice in Mexico. The purpose of this partnership was to develop a Mexican national clinical trials network of substance abuse researchers and providers capable of implementing effectiveness randomized clinical trials in community-based settings. A technology transfer model was implemented. The Florida Node Alliance shared the “know how” for the development of the research infrastructure to implement randomized clinical trials in community programs through core and specific training modules, role-specific coaching pairings, modeling, monitoring and feedback. The technology transfer process was bi-directional in nature in that it was informed by feedback on feasibility and cultural appropriateness for the context in which practices were implemented. The Institute, in turn, led the effort of creating the national network of researchers and practitioners in Mexico and the implementation of the first trial. A collaborative model of technology transfer was useful in creating a Mexican researcher-provider network that is capable of changing practice in substance abuse research and treatment in Mexico. Key considerations for transnational technology transfer are presented.

Keywords: technology transfer, clinical trials, implementation, evidence-based practices

Introduction

Evidence shows that in most fields in medicine, translation from research to practice can take considerable time (1–4). In the US, this particular disconnect between research and practice in drug abuse treatment (5–10) led to the establishment by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (NIDA CTN) (11). This network brought together academic researchers and community-based providers to develop and execute rigorous clinical trials of treatment interventions that fulfill the practical needs of community-based drug abuse treatment programs. Engaging substance abuse treatment providers in the research process in the US CTN improved generalizability, acceptability, adoption and dissemination of research results (12–14).

Adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices for drug abuse in real world treatment settings is a challenge outside of the US as well. In Mexico, as in other low and middle income countries (LAMICs), this challenge is heightened by the lack of research infrastructure and capacity for the implementation of rigorous studies capable of generating evidence on locally effective substance abuse and mental health treatments to inform the decision-making process in clinical practice (15–16). The need to bring evidence-based interventions for drug abuse treatment to community centers in Mexico gained urgency with the creation of 335 new centers for primary, first level of care of addictive disorders by Mexico’s federal government (UNEME- CAPAS). This offered a perfect opportunity to transfer to Mexico the technology of the US NIDA CTN (11–14), and create the first national clinical trials network for substance abuse and mental health treatment in Latin America.

To facilitate technology transfer, a partnership was developed between a CTN-participating academic institution in the US, the University of Miami, and the National Institute of Psychiatry within the Ministry of Health in Mexico with the larger goal of improving substance abuse treatment in Mexico. The goals of the partnership were to develop a national clinical trials network of substance abuse and mental health researchers and providers in Mexico, and to develop and implement the first randomized clinical trial within the newly created network. The objectives of this paper are to 1) describe the methodology for transferring the technology used in the US to develop a researcher-provider national clinical trials network to conduct randomized clinical trials of drug abuse and mental health treatments in real-world, community-based settings in Mexico, 2) present the results of the technology transfer and 3) provide key considerations as a result of lessons learned in the process.

1. Methodology of the Technology Transfer

The transfer of technology was supported by a bi-national collaborative effort that involved the University of Miami-based Florida Node Alliance of the US NIDA CTN, hereafter referred as the “Node”, the National Institute of Psychiatry in Mexico, hereafter referred as the “Institute” and several key players working within a facilitative context (See Table 1).

Table 1:

Partners & stakeholders in the US-Mexico technology transfer collaboration

| Institution | Role | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mérida Initiative & U.S. Department of State | The Sponsor | A binational cooperation program between Mexico and U.S. that includes support for the creation of Mexico’s first comprehensive national demand reduction infrastructure. |

| U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (NIDA-CTN) | The Model for the Innovation | U.S. research to practice network in the field of drug abuse treatment. |

| Florida Node Alliance at the University of Miami- referred to as The Node | The Knowledge Broker – Mentor | One of the thirteen centers that comprise the U.S. NIDA CTN, experienced in conducting research with Hispanic and Spanish-only speaking populations, with fully bi lingual and bi cultural team members in areas of clinical trial development and implementation, design and methodology, protocol development, quality monitoring, and trial management. |

| The National Institute of Psychiatry in Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, -INPRF, 2013)-referred to as The Institute | Mentee | An Institute within the Mexican Ministry of Health that provides leadership in epidemiological, psychosocial, clinical, and neuroscience research, training, and services in the areas of substance abuse and mental health. |

| The National Center for the Prevention and Control of Addictions in Mexico (Comisión Nacional Contra las Adicciones - CONADIC, 2013) | Stakeholder | Federal commission within Mexico’s Ministry of Health with the mission of promoting and protecting the health of Mexicans through the design and implementation of national policies in matters of research, prevention, treatment and development of human resources for the control of addictions. |

| The National Center for the Prevention and Control of Addictions in Mexico(Centro Nacional Contra las Adicciones - CENADIC, 2013) | Stakeholder | Government office in charge of the planning and direction of the nation-wide newly created 335 primary, first- level care addiction treatment centers, under the coordination of 32 national state councils at the national level. |

| The Youth Integration Centers (Centros de Integración Juvenil -CIJ, 2013) | Stakeholder | Non-profit organization and civic association funded in 1969 by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with community boards. Comprised of 115 treatment centers throughout the country dedicated to drug demand reduction through the delivery of community-based substance abuse prevention and treatment programs. |

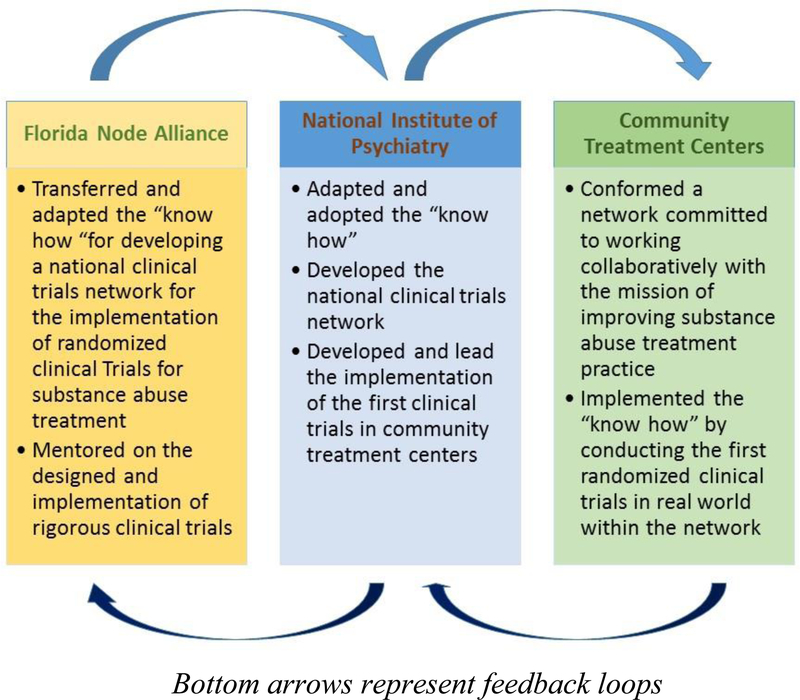

The adoption of the US NIDA CTN model was facilitated through a process referred to as Technology Transfer (17, 18). Technology transfer took place in two sequential, yet overlapping processes: The Node shared the “know how” for the development of the research infrastructure necessary to implement randomized clinical trials in community treatment programs and the methodology with which these trials would be implemented. The Institute, in turn, led the national effort of creating the network of researchers and practitioners. In collaboration with the Node, the Institute selected and adapted the design of the first trial that was implemented in the network and was responsible, under the Node’s mentorship, for leading the implementation of the trial (19). These processes were bi-directional in nature, that is, they were informed by feedback on feasibility and cultural appropriateness for the context in which they were implemented (see Figure 1).

Figure 1:

The bidirectional process of technology transfer to improve substance abuse treatment in Mexico

The Innovation

The innovation consisted of a set of practices and guidelines, i.e., the “know how” for building and maintaining a network of scientists and treatment providers with the goal of implementing clinical trials for the treatment and prevention of drug abuse and mental health problems in Mexico. These practices and guidelines (Table 2) were gleaned from the Node team’s experience over the last 15 years in the US NIDA CTN.

Table 2:

The Innovation—set of practices transferred from US to Mexico for the implementation of rigorous clinical trials

| Development of a Clinical Trials Network |

| Partnership Development |

| ❑ Identification of potential partners |

| ❑ Site visits |

| ❑ Development of a general survey to assess agency/site capacity and needs |

| ❑ Development of institutional working agreements |

| Infrastructure Development |

| ❑ Creation of a Network Coordinating Team (Clinical Trials Unit) |

| ❑ Director |

| ❑ Implementation Coordinator |

| ❑ Intervention Coordinator |

| ❑Data Manager |

| ❑Quality Monitoring Director |

| ❑Statistician |

| ❑Logistical Coordinator |

| ❑Administrative Support |

| ❑ Acquisition of physical infrastructure for coordinating team and sites |

| ❑ Allocation of physical spaces |

| ❑ Technology (software, hardware, equipment) |

| Implementation of a Clinical Trial |

| Protocol Development |

| ❑ Write up of protocol narrative |

| ❑ Selection and adaptation of study-specific outcome measures |

| ❑ Selection of sites to conduct the trial |

| ❑Development of a study-specific site survey |

| ❑Site visits for study-specific site selection |

| ❑ Development of study-specific Informed Consent forms |

| ❑ Submission of study documents to IRB for approval |

| Quality and Regulatory Monitoring |

| ❑ Development of a study-specific Quality Monitoring plan |

| ❑ Development of study-specific Quality Monitoring tools and report templates |

| ❑ Identification of regulatory requirements for the study (for the coordinating center and the sites) |

| ❑ Implementation of periodic on-site monitoring visits ( site initiation, interim and close out visits) |

| Intervention |

| ❑ Selection of the interventionists (e.g., randomly assigned or appointed) |

| ❑ Development of the intervention fidelity tools/process/medication compliance |

| ❑ Training and certification on a manualized intervention |

| ❑ Intervention monitoring (fidelity) |

| Data Management |

| ❑ Selection and Acquisition of electronic data capture system compliant with international regulations |

| ❑ Development of the Data Management Plan: Definition of data QA procedures |

| ❑ Development of the Case Report Forms (CRFs) |

| ❑ Training and certification for system users |

| Implementation |

| ❑ Development of Manual of Operations and Procedures and site specific procedures |

| ❑ Establishment of staff training and certification requirements |

| ❑ Preparation and delivery of study-specific training |

| ❑ Management and oversight of study implementation |

| ❑Weekly calls with sites |

| ❑Tracking of site performance (e.g., weekly recruitment and retention reports) |

The Strategy for Technology Transfer

The strategy for technology transfer involved a stage-wise acquisition of knowledge in sequential, overlapping steps and practical testing of the knowledge gained. These steps involved a progression from (a) developing the knowledge needed to create the infrastructure of the network and building a knowledge base of clinical trial concepts and practices to (b) developing/adapting a research protocol, and (c) subsequently implementing/managing the protocol at multiple sites within the newly formed network. The steps were overlapping in that processes of creating the network and developing and implementing the first trial were intertwined and informed by each other.

The process of technology transfer was supported by a structured communications plan. The Node team and the leadership at the Institute established regular meetings with specific objectives, which allowed the process of technology transfer to unfold over time. Executive calls, operations calls, and site implementation calls occurred weekly, and face-to-face meetings were held periodically. In addition, informal communications between the Node and the Institute occurred daily or as needed via phone, e-mail, Skype and WebEx CISCO Technology. Meetings served as an essential forum for providing recommendations, instruction, coaching, and feedback, as well as an opportunity to monitor the practices and processes set forth. The Node and Institute teams identified implementation challenges in real time and worked together to develop solutions that were feasible and sustainable.

Phases of Technology Transfer and Implementation

The implementation of the innovation progressed through a continuum of phases as illustrated in Figure 2. As described in the implementation science literature, the phases included exposure, adoption, (trial) implementation and routine practice (20–24).

Figure 2:

Phases of technology transfer and implementation – From exposure to sustainability

The first phase, exposure, entailed exploration and the evaluation, by the Director of the Institute, of the US NIDA CTN as a model to improve substance abuse practice in Mexico. Next, the adoption phase included the preparation of the terrain and building the capacity and infrastructure at the Institute. The Node and the Institute had collaborated previously in other contexts and built upon existing trust to develop a common vision and objectives for this collaboration. Building the infrastructure at the Institute began with the creation of a specialized team, the Clinical Trials Unit (Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos, UEC), composed by 6 cores: Implementation, Quality Monitoring, Intervention Supervision and Fidelity, Data management, Statistics, and Logistics and Coordination. The structure of this Unit mirrored existing operational cores at the Node. The Unit Director and core leaders were each assigned a specific member of the Node’s team for ongoing daily mentoring and support in their respective areas of expertise. Role-specific coaching pairings allowed one-on-one specialized attention, supported professional and technical development, facilitated joint problem-solving, and promoted cross cultural understanding. The next step included the delivery of core training modules on clinical trial implementation and management to the Institute. The core training modules for the Clinical Trials Unit were delivered in Spanish by the Node team via a series of face-to-face sessions, which lasted 3 to 4 days each. Modules and their corresponding practical assignments were organized around major content areas: Methodology and Design of randomized clinical trials, Good Clinical Practices (GCP), which included a regulatory component and the importance of informed consent, Quality Monitoring, and Data Management. The instructional content delivered at each step included core concepts and “how to’s” followed by relevant activities where new concepts could be immediately applied with real-time feedback and support. The adaptation and conduct of a trial provided a rich and structured opportunity to apply newly learned concepts and practices. A number of different teaching techniques were used with flexibility. These included didactic instruction, experiential learning, modeling, coaching, monitoring and feedback.

The trial implementation phase entailed building the clinical trials network and the implementation of the first trial. The development of the Mexican Clinical Trials Network included the establishment of partnerships with other institutions and community treatment centers to build the foundation of the network. This included visits to community treatment programs and involved the assessment of: characteristics of the patient populations served, existing treatment and research capacities, openness to participating in randomized clinical trials, and program needs. These visits helped to consolidate relationships with the Institute’s founding partners in the network, the Youth Integration Centers and the National Center for the Prevention and Control of Addictions, as well as to identify community treatment programs that could carry out the first trial. Critical to the technology transfer plan was the selection of a clinical trial that would serve as the “task” around which the network and its procedures were established and around which capacities were built. The goal was to select a trial that had previously been implemented in the US CTN, which could be readily adapted for implementation and that was relevant to the treatment needs in Mexico. The Motivational Enhancement Therapy for Spanish Speakers - CTN 0021 (MET-S) (25) trial was selected because it met these conditions and addressed the documented clinical problem of poor treatment engagement and retention in outpatient drug abuse treatment centers in Mexico (26, 27).

The central activities of the implementation phase were the adaptation of the MET-S research protocol by the Institute’s Clinical Trials Unit, and the implementation of the trial at three community treatment programs within the new network. The implementation of a multi-site randomized clinical trial allowed the Clinical Trials Unit team to apply their newly acquired knowledge and served to test the infrastructure and systems developed. With support and monitoring from the Node, the Clinical Trials Unit led and served as the central coordinating center for the trial. They were responsible for all aspects of trial management, including budget and timeline planning, training of study teams, development of study procedures (Manuals of Operations), performance and quality monitoring, and data management. The Node trained and certified therapists and clinical supervisors at each of the trial sites to build local capacity on Motivational Enhancement Therapy and thereby facilitate the sustainability of the intervention at sites after the completion of the trial.

The final phase in implementing an innovation, as described in the literature, is routine practice. Routine practice refers to the sustainability of the practices gained, described below under Results of the Technology Transfer.

2. Results of the Technology Transfer

The primary objectives of the technology transfer collaboration were met. A Mexican national clinical trials network of substance abuse researchers and providers was established, and the first randomized clinical trial was successfully completed within the newly created network.

Under the mentorship and coaching of the Node, the Institute adapted and implemented the first trial in the Mexican Clinical Trials network at 3 outpatient community based centers. The objective of this trial was to compare the effectiveness of Motivational Enhancement Treatment (MET) versus Counseling as Usual in retaining substance users in treatment and reducing substance use. The design and characteristics of this trial, Motivational Enhancement Treatment for outpatient treatment seekers in Mexico, can be found in Marin-Navarette (28). Study procedures were consistent with the ethical standards for protecting human subjects and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and were approved by the internal review boards/ethics committees of all participating institutions, where applicable. All trial participants provided written, informed consent. Safety events were identified and monitored for all study participants, according to a study–specific monitoring plan. The trial was implemented with outstanding performance, achieving its randomization target of 120 participants across 3 outpatient sites ahead of schedule, with a treatment exposure rate of 92%, and 93% and 95% attendance, respectively, at the 2 and 4 month research follow up visits. The Clinical Trials Unit developed and implemented a study-specific Quality Assurance Plan, which included on-site monitoring visits, written reports of findings, the systematic identification and reporting of protocol violations, and the implementation of corrective and preventive actions to address all findings and violations. Moreover, the trial provided training in research methods, processes and intervention to more than 143 community treatment professionals (counselors, research assistants and clinic directors) through 47 trainings.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the ultimate step in instituting new practices/innovations is to move from trial use to routine practice. We defined routine practice in terms of the continued conduct of rigorous research using the infrastructure and the practices gained as part of the technology transfer process. Results of the technology transfer and sustainment of the practices gained are presented in Table 3 and are summarized below.

Table 3.

Results of the technology transfer: sustainment of the practices gained

| Expansion of the Mexican Clinical Trials Network |

| • Six collaborative research agreements established with institutions in Mexico |

| • Agreements permitted research implementation in 45 different clinical settings: |

| ○ 9 outpatient addiction primary care centers |

| ○ 36 NGO mutual aid residential care centers |

| ○ 2 outpatient community treatment centers |

| ○ 1 hospital outpatient clinic |

| Implementation of new1 research projects |

| • REC 002: Online intervention for Substance Use Disorders (completed) |

| • REC 003: Co-Occurring Disorders &Validation Scales in residential facilities in Mexico (completed) |

| • REC 004: An Examination of the Mexican Clinical Trials Network (in progress) |

| ○ A Qualitative Study on the Technology Transfer Collaboration |

| ○ Readiness to Adopt- and Adoption of Evidence Based Practices by centers of the Mexican Trials Network |

| • REC 005: Co-Occurring Disorders in people with disabilities in Mexico City (completed) |

| • REC 006: Co-Occurring Disorders and Neuropsychological conditions in inhalant dependent adults (under development) |

| Improvement of research capacity at treatment centers |

| Total of 72 research training modules have been delivered to approximately 143 mental health professionals: |

| • Overview of clinical trials |

| • Clinical assessment |

| • Participant recruitment and retention strategies |

| • Good clinical practices and ethics in research |

| Development for the delivery of Evidence-Based interventions |

| Specialized training/certification delivered to 27 mental health professionals in Evidence-Based Interventions: |

| • Motivational Enhancement Treatment in Spanish (METS) - Delivery and Supervision |

| • ASSIST – Brief Intervention |

| • Online Intervention for Substance Abuse and Depression |

| Dissemination of scientific findings |

| Research findings from network projects have been presented in: |

| • 7 invited lectures at international congresses and meetings |

| • 9 research posters |

| • 3 papers in peer-reviewed journals |

| • 1 book chapter |

‘New’ means after the completion of the first trial

Expansion of the Mexican Clinical Trials Network

The Clinical Trials Unit has developed new partnerships using the infrastructure created and the methodology acquired, and has now expanded to include an additional institution (i.e., the National University in Mexico) and participating centers (i.e., centers overseen by state councils and non-governmental organizations) with both outpatient and residential settings. This expansion was intended to broaden the network’s reach to a wider population with substance use and mental health problems. The first trial was implemented in three outpatient treatment centers. The new partnerships have allowed the implementation of research projects in 45 additional treatment centers.

Implementation of new research projects

The new network has completed a second randomized clinical trial testing an online intervention and a clinical measures validation study-- both within the expanded network, and a study examining the process of technology transfer.

Improvement of research capacity at treatment centers

Research trainings and protocol specific trainings, including the use clinical research methodology and procedures, standardized measures, good clinical practice and ethics in research, were delivered to sites of the expanded network.

Development of capacity for the delivery of Evidence Based Interventions (EBIs)

Specialized training and certification on three evidence based interventions were delivered for professionals from participating treatment centers.

Dissemination of scientific findings

The Mexican Clinical Trials network, in collaboration with its partners, has presented their work in national and international conferences and has published in peer reviewed journals and an edited book.

3. Key Considerations for Transnational Technology Transfer

There are key considerations for transnational technology transfer to be successful. First, is the development of mutually agreed-upon goals and a work plan to guide the collaboration and ensure active investment and accountability by both partners. Second, a detailed needs assessment is critical to identify existing local infrastructure (personnel, systems and expertise) on which to build, as well as to identify areas that will require full development. Third, a local team capable of leading the adoption and implementation of the innovation and sustaining it into the future must be established. Fourth, the mentor team must be culturally informed, able to communicate effectively with the local team in a common language, and have protected time for ongoing support for the duration of the project. Fifth, role-specific coaching pairings allow for efficient and specialized mentoring and facilitate the use of modeling and observation as learning strategies. Sixth, vital for the survival of the project is the identification of invested leaders at all levels of the mentee’s country/institution: Ministry of health, at the participating institutions, and at the community/clinic level. Seventh, the implementation of randomized clinical trials demands careful evaluation of the local regulatory and ethical guidelines, administrative processes and approvals needed in order to ensure local compliance, as well as plan timelines accordingly. Eighth, partners must allot time and resources to the cultural adaptation of all research interventions, measures, and procedures prior to implementation. For example, adaptations need to be considered when deciding on participant reimbursement and staff compensation structure for research. While in the US participants are reimbursed for time spent in research, this might not be standard practice elsewhere. The adaptation process should involve consideration and discussion of the intended purpose of the practice, and how its implications or consequences may vary once implemented in a different country. Similarly, though a standard practice in the US, in other countries it may be difficult or impossible to directly cover personnel time on research activities using research funds. Partners can elaborate alternative ways of providing compensation for the time staff dedicates to the research project, to reward and ensure accountability. Additionally, particular attention needs to be placed on the cultural norms of communication. While much of the communication can occur online or by phone, some cultures place a high value on face to face contact, and this should be respected in planning critical collaborative and problem-solving activities, as well as in celebrating successes and accomplishments. Finally, trust, patience, humility, and flexibility are key ingredients for a true working collaboration.

Discussion

This paper presents a technology transfer collaboration for the development of research infrastructure to support the rigorous testing and implementation of evidence-based practices, evidences its success and provides key considerations for transnational technology transfer. A recent systematic review of implementation frameworks conducted by Moullin (24) acknowledges the multiple existing models for technology transfer and explains that not all models include the full range of concepts involved in implementation. Ward (29) summarize common elements of 28 models of knowledge transfer but argue that studies on knowledge transfer have focused on narrow deterministic approaches instead of focusing on the broad explanations of the journeys from knowledge to action. Literature (30) has also described the components for capacity building and sustainable transfer of technology to developing countries. The work we present here illustrates the application of some of the core concepts of these frameworks to exemplify the methodology used for the development of research infrastructure for addiction and mental health treatment, lacking in LAMIC. While concepts described in our method have been presented in the literature, the novel contribution of this paper is its application. Our work initiated the first research to practice network for the implementation of clinical trials for mental health and drug abuse treatment in Latin America. The process and strategy followed in the development of the clinical trials network in Mexico included some distinct components. First, the common vision for the technology transfer was developed jointly and collaboratively, rather than promoted primarily by either the user or the knowledge broker. Second, in addition to a coaching team, each member of the team had an assigned mentee, which allowed for specialized coaching on practice based projects over time. Finally, the process of technology transfer was culturally informed, and transcended beyond the adaptation described for EBIs and EBPs (31, 32) and included not only the adaptation of the EBIs tested, but the process was informed by the contextual and cultural appropriateness of the practices that were being adopted.

The research to practice network created and,most importantly, the local team responsible for leading the network in the development and implementation of rigorous clinical trials in real world settings, are capable of generating evidence on treatments that effective and culturally relevant to the populations they serve. The culture of quality and quality monitoring that was brought along by the technology transfer process for the rigorous implementation of research has impacted practices at the Institute and the treatment centers. In addition, some of the solutions generated as a result of the collaboration and participation in the network have included strategies to improve outreach to the population in need. The research infrastructure created can serve as a wide dissemination platform for evidence-based practice, thus advancing the quality of care for substance abuse and mental health in Mexico. All these accomplishments translate into gains for the population.

Organizational readiness for change (33–35) has been defined as the extent to which organizational members are psychologically and behaviorally prepared to implement organizational change. In this case the Node, the Institute, and the participating sites were motivated and open to change; the context of the newly created centers generated the opportunity for an improvement in practice; funding was readily available; and skilled personnel was ready to take on this initiative. It is possible that this readiness facilitated the sustainment of the practices gained.

Limitations

A limitation of this project was that while we were able to document that the goals of the technology transfer were achieved, we did not measure organizational readiness for change at baseline (the start of the network) or key theoretical or empirical mediators of the process of change. A second limitation is that although training and capacity building are essential to the technology transfer process, they are not sufficient to guarantee that the transferred innovation will be sustained over longer periods of time. Factors which may endanger long term sustainability include lack of funding, lack of incentives or lack of knowledge when facing new practices. This aspect is a challenge to overcome in the future.

Conclusions

A partnership between the Florida Node Alliance of the US National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network and Mexico’s National Institute of Psychiatry was established to improve substance abuse practice in Mexico. Through a technology transfer collaboration a Mexican national clinical trials network of substance abuse researchers and providers was established to generate local evidence on effective treatments. The Clinical Trials Unit established as the coordinating center for the network is a multifaceted infrastructure that can contribute to the improvement of both science and practice through collaboration with practitioners in the field. The Unit has adopted systems and methods for the implementation and oversight of clinical trials in real world settings, has developed the capacity to serve as trainers in core research assessment measures, has established quality monitoring and intervention fidelity cores and has the capacity to train and supervise clinicians in the interventions tested. The versatile structure created at the Unit has been used in the implementation and oversight of new clinical trials and research projects, in the dissemination of evidence-based practices in community treatment centers and can be used in the evaluation of current treatment programs. Through the creation of the network and the implementation of the first trial and through the sustainment of practices into new projects, the bridge between science and practice has been created and has the potential of being further sustained into the future.

Future Directions- Recommendations

As the Institute moves into the sustained practice of implementing new randomized clinical trials on evidence-based models, the Institute could serve as a consultant for other Latin American countries that decide to adopt this model for practice improvement. Thus, the Mexican Clinical Trials Network could serve as the foundation for a multinational collaboration of researchers and practitioners devoted to improving substance abuse practice.

Finally, implementation research calls for subsequent efficacy and effectiveness research to ensure that the methodology of technology transfer used in this collaboration improves outcomes. In the case of the Node-Institute collaboration, this research on the methodology of the transfer should pursue the following objectives: first, to examine the process of the transfer of the “know how” from the Node to the National Institute of Psychiatry, and second, to examine the adoption and implementation of the evidence-based practices that the Mexican Clinical Trials Network tests. Such studies are currently underway to better understand whether we were able to change practice. Subsequent studies could examine whether changes in practice translate into improved patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the United States Agency of International Development, Department of State S-INLEC11GR020, SINLEC11GR0015, and Grant 1UL1TR000460 from the National Center for the Advancement of Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State. We would like to specially thank the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN), Grant U10DA13720 and the site principal investigators of the first trial implemented in the Mexican Clinical Trials Network, Ricardo Sánchez Huesca, Ph.D., Carlos Lima Rodriguez Rodríguez, M.D., Ana De la Fuente Martín, M.D., and participating institutions, Centros de Integración Juvenil, CIJ, Centro “Nueva Vida” de Atención Primaria para las Adicciones, Puebla-Sur, and Centro de Trastornos Adictivos, Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente, Centro Nacional Para la Prevención de las Adicciones (CENADIC) and Comisión Nacional Contra las Adicciones, (CONADIC). A special acknowledgment is also given to Christiane Farentinos, M.D. and Thelma Vega, L.M.H.C., who provided training and coaching on the intervention tested in the clinical trial; to Manuel Paris, Psy.D., and Luis Anez, Psy.D., who collaborated as trainers and coaches for the intervention fidelity ratings; and to the Caribbean Basin and Hispanic Addiction Technology Transfer Center, who trained on the Addiction Severity Index. Finally, a special acknowledgment goes to Kathy Carroll, Ph.D. and her team at Yale University. The clinical trial around which the technology transfer occurred was an adaptation of CTN 0021 Motivational Enhancement Therapy for Spanish Speakers led by Drs. Carroll and Szapocznik.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The spouse of a study team member is an employee of INFOTECHSoft, Inc., a subcontractor on this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors were responsible for the technology transfer process.

References

- 1. Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing Clinical Knowledge for Health Care Improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient-centered Systems. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer, 2000:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green LW, Ottson JM, Garcia C, Hiatt RA. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Ann Rev Public Health. 2009; 30:151–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanney SR, Castle-Clarke S, Grant J, et al. How long does biomedical research take? Studying the time taken between biomedical and health research and its translation into products, policy, and practice. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2015; 13:1 Doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2011; 104(12):510–520. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ. Bridging the Gap: A Hybrid Model to Link Efficacy and Effectiveness Research in Substance Abuse Treatment. Psychiatric services. 2003; 54(3):333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller WR, Sorensen JL, Selzer JA, Brigham GS. Disseminating evidence-based practices in substance abuse treatment: a review with suggestions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006; 31:25–39. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham AJ, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM. Counselor Attitudes toward Pharmacotherapies for Alcohol Dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009; 70(4):628–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham AJ, Knudsen HK, Roman PM. The relationship between Clinical Trial Network protocol involvement and quality of substance use disorder (SUD) treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014; 46(2): 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.021. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roll JM, Madden GJ, Rawson R, Petry NM. Facilitating the Adoption of Contingency Management for the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2009; 2(1):4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perl HI, Elcano J. Bridging the Gap between Research and Practice: The National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. The Observer, Association of Psychological Sciences. 2011; 24(10). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tai B, Straus MM, Liu D, Sparenborg S, Jackson R, McCarty D. The First Decade of the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network: Bridging the Gap between Research and Practice to Improve Drug Abuse Treatment. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2010; 38(Suppl 1):S4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martino S, Brigham GS, Higgins C, et al. Partnerships and Pathways of Dissemination: The NIDA-SAMHSA Blending Initiative in the Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010; 38(Suppl 1):S31–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roman PM, Abraham AJ, Rothrauff TC, Knudsen HK. A longitudinal study of organizational formation, innovation adoption, and dissemination activities within the National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010; 38S1:S44-S52. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll KM, Ball SA, Jackson R, et al. Ten Take Home Lessons from the First Ten Years of the CTN and Ten Recommendations for the Future. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2011; 37(5):275–282. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medina-Mora ME, Noknoy S, Cherpitel C, Real T, Pérez R et al. Trials of Interventions for People with Alcohol Use Disorders In Thornicoft Patel, eds. Global Mental Health Trials, Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rojas E, Real T, García S, Medina-Mora ME. Revisión sistemática sobre tratamiento de adicciones en México. Salud Mental. 2011; 34: 351–365. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahab SA, Rose RC, Osman SI. Defining the concepts of technology and technology transfer: A literature analysis. International Business Research. 2012: 5(1); 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC) Network Technology Transfer Workgroup. Research to practice in addiction treatment: key terms and a field-driven model of technology transfer. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011. Sep; 41(2):169–78. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marín-Navarrete R, Fernández-Mondragón J, Eliosa-Hernández A, et al. Methodological and ethical aspects in conducting randomized controlled clinical trials (RTC) for addictive disorder’s interventions. Salud Mental. 2013; 36(3): 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpson DD, Flynn PM. Moving Innovations into Treatment: A Stage-based Approach to Program Change. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2007; 33(2):111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, Wallace F. Core implementation components. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009; 19:531–40. Doi: 10.1177/1049731509335549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a Conceptual Model of Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2011; 38(1):4–23. Doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehman WE, Simpson DD, Knight DK, Flynn PM. Integration of treatment innovation planning and implementation: strategic process models and organizational challenges. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011. Jun; 25(2):252–61. Doi: 10.1037/a0022682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moullin JC, Sabater-Hernández D, Fernandez-Llimos F, Benrimoj SI. A systematic review of implementation frameworks of innovations in healthcare and resulting generic implementation framework. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2015; 13:16 Doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0005-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll KM, Martino S, Ball SA, et al. A Multisite Randomized Effectiveness Trial of Motivational Enhancement Therapy for Spanish-Speaking Substance Users. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009; 77(5):993–999. Doi: 10.1037/a0016489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borges G, Wang PS, Medina-Mora ME, Lara C, Chiu WT. Delay of First Treatment of Mental and Substance Use Disorders in Mexico. American Journal of Public Health. 2007; 97(9):1638–1643. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villatoro J, Medina-Mora ME, Fleiz Bautista C, et al. El consumo de drogas en México: resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Adicciones, 2011. Salud Mental. 2012, 35:447–457. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marín R, Templos-Nunez L, Eloisa A, et al. Characteristics of a Treatment-Seeking Population in Outpatient Addiction Treatment Centers in Mexico. Substance Use and Misuse. 2014; 49(13):1784–1794. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.931972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward V, House A, Hamer S. Developing a framework for transferring knowledge into action: a thematic analysis of the literature. Journal of health services research & policy. 2009; 14(3):156–164. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.008120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coloma J, Harris E. Reducing the Impact of Poverty on Health and Human Development: Scientific Approaches. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008; (1136): 358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castro FG, Barrera M, Holleran Steiker LK. Issues and Challenges in the Design of Culturally Adapted Evidence-Based Interventions. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2010; 6:213–239. Doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, Teixeira A, Whiteside HO. Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the strengthening families program. Eval Health Prof. 2008; 31(2):226–39. Doi: 10.1177/0163278708315926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiner BJ, Amick H, Lee SY. Conceptualization and measurement of organizational readiness for change: a review of the literature in health services research and other fields. Med Care Res Rev. 2008; 65(4):379–436. Doi: 10.1177/1077558708317802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams I Organizational readiness for innovation in health care: some lessons from the recent literature. Health Serv Manage Res. 2011; (24): 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gagnon M-P, Attieh R, Ghandour EK, et al. A Systematic Review of Instruments to Assess Organizational Readiness for Knowledge Translation in Health Care. Jeyaseelan K, ed. PLoS ONE. 2014; 9(12):e114338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]